We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Popular Templates

- Accessibility

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Business How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

Written by: Danesh Ramuthi Sep 07, 2023

Okay, let’s get real: case studies can be kinda snooze-worthy. But guess what? They don’t have to be!

In this article, I will cover every element that transforms a mere report into a compelling case study, from selecting the right metrics to using persuasive narrative techniques.

And if you’re feeling a little lost, don’t worry! There are cool tools like Venngage’s Case Study Creator to help you whip up something awesome, even if you’re short on time. Plus, the pre-designed case study templates are like instant polish because let’s be honest, everyone loves a shortcut.

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study presentation?

What is the purpose of presenting a case study, how to structure a case study presentation, how long should a case study presentation be, 5 case study presentation examples with templates, 6 tips for delivering an effective case study presentation, 5 common mistakes to avoid in a case study presentation, how to present a case study faqs.

A case study presentation involves a comprehensive examination of a specific subject, which could range from an individual, group, location, event, organization or phenomenon.

They’re like puzzles you get to solve with the audience, all while making you think outside the box.

Unlike a basic report or whitepaper, the purpose of a case study presentation is to stimulate critical thinking among the viewers.

The primary objective of a case study is to provide an extensive and profound comprehension of the chosen topic. You don’t just throw numbers at your audience. You use examples and real-life cases to make you think and see things from different angles.

The primary purpose of presenting a case study is to offer a comprehensive, evidence-based argument that informs, persuades and engages your audience.

Here’s the juicy part: presenting that case study can be your secret weapon. Whether you’re pitching a groundbreaking idea to a room full of suits or trying to impress your professor with your A-game, a well-crafted case study can be the magic dust that sprinkles brilliance over your words.

Think of it like digging into a puzzle you can’t quite crack . A case study lets you explore every piece, turn it over and see how it fits together. This close-up look helps you understand the whole picture, not just a blurry snapshot.

It’s also your chance to showcase how you analyze things, step by step, until you reach a conclusion. It’s all about being open and honest about how you got there.

Besides, presenting a case study gives you an opportunity to connect data and real-world scenarios in a compelling narrative. It helps to make your argument more relatable and accessible, increasing its impact on your audience.

One of the contexts where case studies can be very helpful is during the job interview. In some job interviews, you as candidates may be asked to present a case study as part of the selection process.

Having a case study presentation prepared allows the candidate to demonstrate their ability to understand complex issues, formulate strategies and communicate their ideas effectively.

The way you present a case study can make all the difference in how it’s received. A well-structured presentation not only holds the attention of your audience but also ensures that your key points are communicated clearly and effectively.

In this section, let’s go through the key steps that’ll help you structure your case study presentation for maximum impact.

Let’s get into it.

Open with an introductory overview

Start by introducing the subject of your case study and its relevance. Explain why this case study is important and who would benefit from the insights gained. This is your opportunity to grab your audience’s attention.

Explain the problem in question

Dive into the problem or challenge that the case study focuses on. Provide enough background information for the audience to understand the issue. If possible, quantify the problem using data or metrics to show the magnitude or severity.

Detail the solutions to solve the problem

After outlining the problem, describe the steps taken to find a solution. This could include the methodology, any experiments or tests performed and the options that were considered. Make sure to elaborate on why the final solution was chosen over the others.

Key stakeholders Involved

Talk about the individuals, groups or organizations that were directly impacted by or involved in the problem and its solution.

Stakeholders may experience a range of outcomes—some may benefit, while others could face setbacks.

For example, in a business transformation case study, employees could face job relocations or changes in work culture, while shareholders might be looking at potential gains or losses.

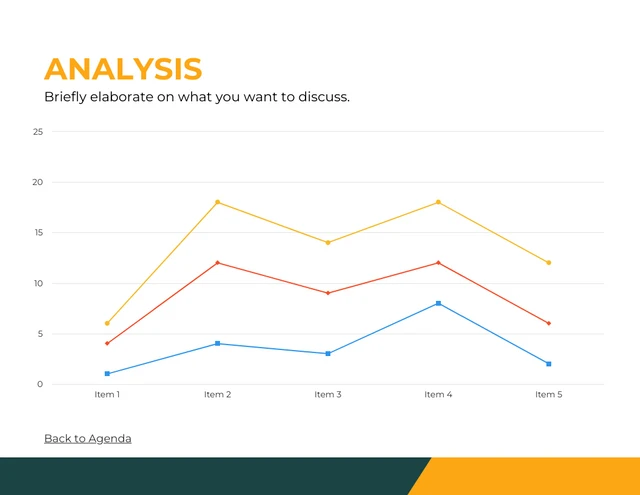

Discuss the key results & outcomes

Discuss the results of implementing the solution. Use data and metrics to back up your statements. Did the solution meet its objectives? What impact did it have on the stakeholders? Be honest about any setbacks or areas for improvement as well.

Include visuals to support your analysis

Visual aids can be incredibly effective in helping your audience grasp complex issues. Utilize charts, graphs, images or video clips to supplement your points. Make sure to explain each visual and how it contributes to your overall argument.

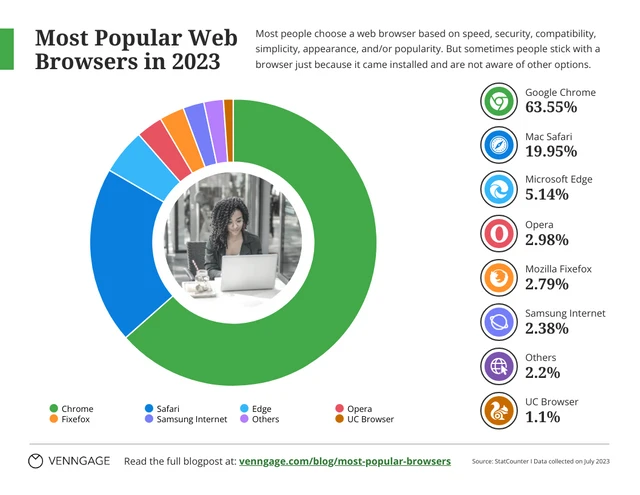

Pie charts illustrate the proportion of different components within a whole, useful for visualizing market share, budget allocation or user demographics.

This is particularly useful especially if you’re displaying survey results in your case study presentation.

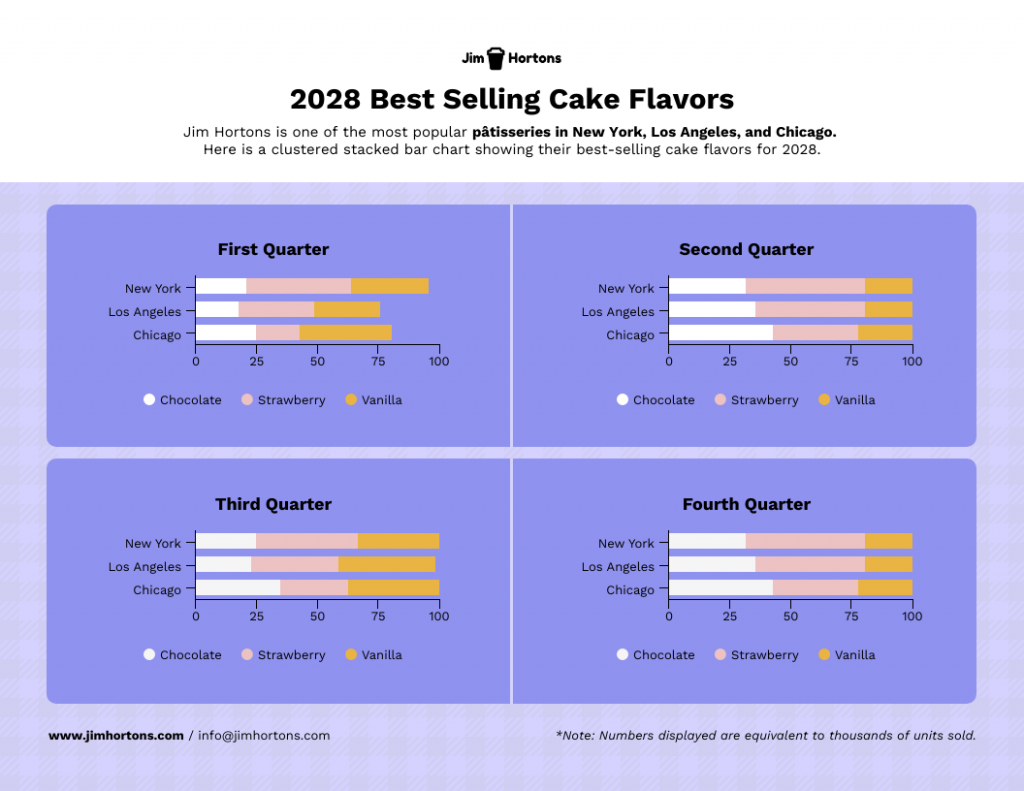

Stacked charts on the other hand are perfect for visualizing composition and trends. This is great for analyzing things like customer demographics, product breakdowns or budget allocation in your case study.

Consider this example of a stacked bar chart template. It provides a straightforward summary of the top-selling cake flavors across various locations, offering a quick and comprehensive view of the data.

Not the chart you’re looking for? Browse Venngage’s gallery of chart templates to find the perfect one that’ll captivate your audience and level up your data storytelling.

Recommendations and next steps

Wrap up by providing recommendations based on the case study findings. Outline the next steps that stakeholders should take to either expand on the success of the project or address any remaining challenges.

Acknowledgments and references

Thank the people who contributed to the case study and helped in the problem-solving process. Cite any external resources, reports or data sets that contributed to your analysis.

Feedback & Q&A session

Open the floor for questions and feedback from your audience. This allows for further discussion and can provide additional insights that may not have been considered previously.

Closing remarks

Conclude the presentation by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the takeaways. Thank your audience for their time and participation and express your willingness to engage in further discussions or collaborations on the subject.

Well, the length of a case study presentation can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the needs of your audience. However, a typical business or academic presentation often lasts between 15 to 30 minutes.

This time frame usually allows for a thorough explanation of the case while maintaining audience engagement. However, always consider leaving a few minutes at the end for a Q&A session to address any questions or clarify points made during the presentation.

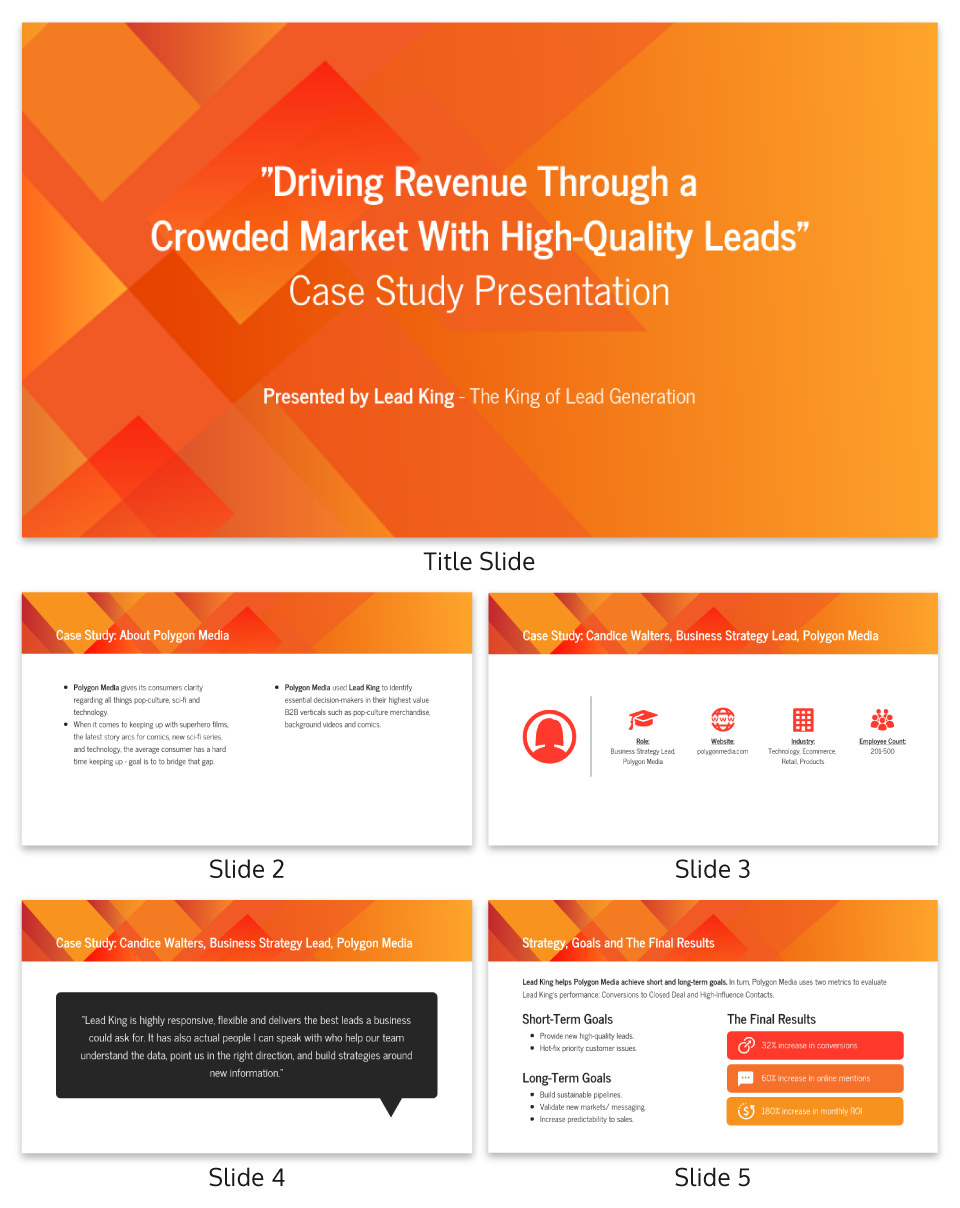

When it comes to presenting a compelling case study, having a well-structured template can be a game-changer.

It helps you organize your thoughts, data and findings in a coherent and visually pleasing manner.

Not all case studies are created equal and different scenarios require distinct approaches for maximum impact.

To save you time and effort, I have curated a list of 5 versatile case study presentation templates, each designed for specific needs and audiences.

Here are some best case study presentation examples that showcase effective strategies for engaging your audience and conveying complex information clearly.

1 . Lab report case study template

Ever feel like your research gets lost in a world of endless numbers and jargon? Lab case studies are your way out!

Think of it as building a bridge between your cool experiment and everyone else. It’s more than just reporting results – it’s explaining the “why” and “how” in a way that grabs attention and makes sense.

This lap report template acts as a blueprint for your report, guiding you through each essential section (introduction, methods, results, etc.) in a logical order.

Want to present your research like a pro? Browse our research presentation template gallery for creative inspiration!

2. Product case study template

It’s time you ditch those boring slideshows and bullet points because I’ve got a better way to win over clients: product case study templates.

Instead of just listing features and benefits, you get to create a clear and concise story that shows potential clients exactly what your product can do for them. It’s like painting a picture they can easily visualize, helping them understand the value your product brings to the table.

Grab the template below, fill in the details, and watch as your product’s impact comes to life!

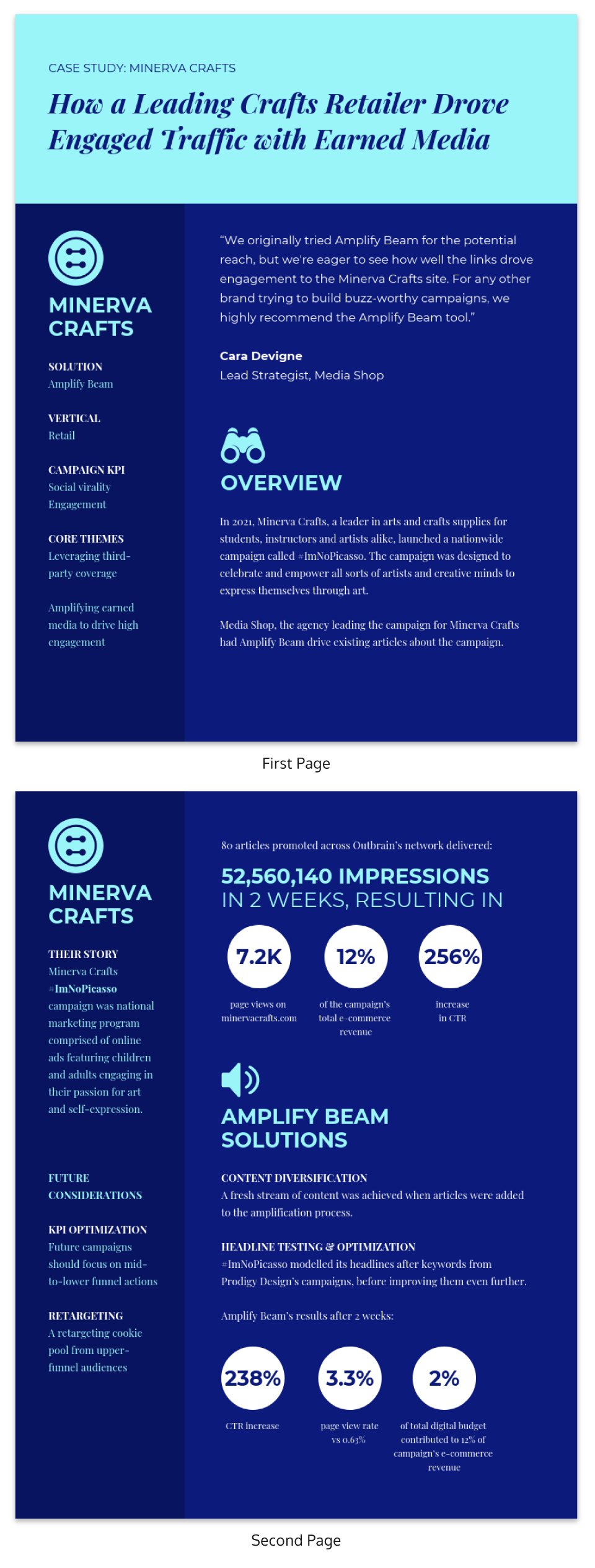

3. Content marketing case study template

In digital marketing, showcasing your accomplishments is as vital as achieving them.

A well-crafted case study not only acts as a testament to your successes but can also serve as an instructional tool for others.

With this coral content marketing case study template—a perfect blend of vibrant design and structured documentation, you can narrate your marketing triumphs effectively.

4. Case study psychology template

Understanding how people tick is one of psychology’s biggest quests and case studies are like magnifying glasses for the mind. They offer in-depth looks at real-life behaviors, emotions and thought processes, revealing fascinating insights into what makes us human.

Writing a top-notch case study, though, can be a challenge. It requires careful organization, clear presentation and meticulous attention to detail. That’s where a good case study psychology template comes in handy.

Think of it as a helpful guide, taking care of formatting and structure while you focus on the juicy content. No more wrestling with layouts or margins – just pour your research magic into crafting a compelling narrative.

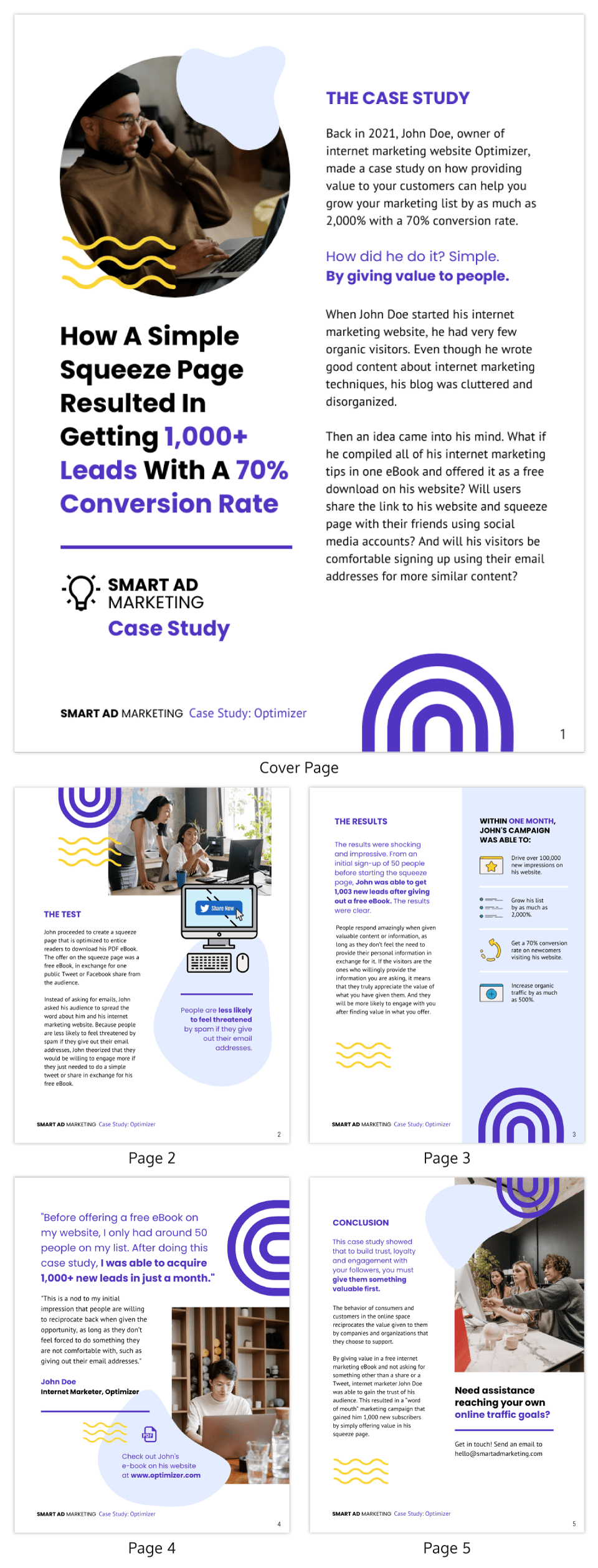

5. Lead generation case study template

Lead generation can be a real head-scratcher. But here’s a little help: a lead generation case study.

Think of it like a friendly handshake and a confident resume all rolled into one. It’s your chance to showcase your expertise, share real-world successes and offer valuable insights. Potential clients get to see your track record, understand your approach and decide if you’re the right fit.

No need to start from scratch, though. This lead generation case study template guides you step-by-step through crafting a clear, compelling narrative that highlights your wins and offers actionable tips for others. Fill in the gaps with your specific data and strategies, and voilà! You’ve got a powerful tool to attract new customers.

Related: 15+ Professional Case Study Examples [Design Tips + Templates]

So, you’ve spent hours crafting the perfect case study and are now tasked with presenting it. Crafting the case study is only half the battle; delivering it effectively is equally important.

Whether you’re facing a room of executives, academics or potential clients, how you present your findings can make a significant difference in how your work is received.

Forget boring reports and snooze-inducing presentations! Let’s make your case study sing. Here are some key pointers to turn information into an engaging and persuasive performance:

- Know your audience : Tailor your presentation to the knowledge level and interests of your audience. Remember to use language and examples that resonate with them.

- Rehearse : Rehearsing your case study presentation is the key to a smooth delivery and for ensuring that you stay within the allotted time. Practice helps you fine-tune your pacing, hone your speaking skills with good word pronunciations and become comfortable with the material, leading to a more confident, conversational and effective presentation.

- Start strong : Open with a compelling introduction that grabs your audience’s attention. You might want to use an interesting statistic, a provocative question or a brief story that sets the stage for your case study.

- Be clear and concise : Avoid jargon and overly complex sentences. Get to the point quickly and stay focused on your objectives.

- Use visual aids : Incorporate slides with graphics, charts or videos to supplement your verbal presentation. Make sure they are easy to read and understand.

- Tell a story : Use storytelling techniques to make the case study more engaging. A well-told narrative can help you make complex data more relatable and easier to digest.

Ditching the dry reports and slide decks? Venngage’s case study templates let you wow customers with your solutions and gain insights to improve your business plan. Pre-built templates, visual magic and customer captivation – all just a click away. Go tell your story and watch them say “wow!”

Nailed your case study, but want to make your presentation even stronger? Avoid these common mistakes to ensure your audience gets the most out of it:

Overloading with information

A case study is not an encyclopedia. Overloading your presentation with excessive data, text or jargon can make it cumbersome and difficult for the audience to digest the key points. Stick to what’s essential and impactful. Need help making your data clear and impactful? Our data presentation templates can help! Find clear and engaging visuals to showcase your findings.

Lack of structure

Jumping haphazardly between points or topics can confuse your audience. A well-structured presentation, with a logical flow from introduction to conclusion, is crucial for effective communication.

Ignoring the audience

Different audiences have different needs and levels of understanding. Failing to adapt your presentation to your audience can result in a disconnect and a less impactful presentation.

Poor visual elements

While content is king, poor design or lack of visual elements can make your case study dull or hard to follow. Make sure you use high-quality images, graphs and other visual aids to support your narrative.

Not focusing on results

A case study aims to showcase a problem and its solution, but what most people care about are the results. Failing to highlight or adequately explain the outcomes can make your presentation fall flat.

How to start a case study presentation?

Starting a case study presentation effectively involves a few key steps:

- Grab attention : Open with a hook—an intriguing statistic, a provocative question or a compelling visual—to engage your audience from the get-go.

- Set the stage : Briefly introduce the subject, context and relevance of the case study to give your audience an idea of what to expect.

- Outline objectives : Clearly state what the case study aims to achieve. Are you solving a problem, proving a point or showcasing a success?

- Agenda : Give a quick outline of the key sections or topics you’ll cover to help the audience follow along.

- Set expectations : Let your audience know what you want them to take away from the presentation, whether it’s knowledge, inspiration or a call to action.

How to present a case study on PowerPoint and on Google Slides?

Presenting a case study on PowerPoint and Google Slides involves a structured approach for clarity and impact using presentation slides :

- Title slide : Start with a title slide that includes the name of the case study, your name and any relevant institutional affiliations.

- Introduction : Follow with a slide that outlines the problem or situation your case study addresses. Include a hook to engage the audience.

- Objectives : Clearly state the goals of the case study in a dedicated slide.

- Findings : Use charts, graphs and bullet points to present your findings succinctly.

- Analysis : Discuss what the findings mean, drawing on supporting data or secondary research as necessary.

- Conclusion : Summarize key takeaways and results.

- Q&A : End with a slide inviting questions from the audience.

What’s the role of analysis in a case study presentation?

The role of analysis in a case study presentation is to interpret the data and findings, providing context and meaning to them.

It helps your audience understand the implications of the case study, connects the dots between the problem and the solution and may offer recommendations for future action.

Is it important to include real data and results in the presentation?

Yes, including real data and results in a case study presentation is crucial to show experience, credibility and impact. Authentic data lends weight to your findings and conclusions, enabling the audience to trust your analysis and take your recommendations more seriously

How do I conclude a case study presentation effectively?

To conclude a case study presentation effectively, summarize the key findings, insights and recommendations in a clear and concise manner.

End with a strong call-to-action or a thought-provoking question to leave a lasting impression on your audience.

What’s the best way to showcase data in a case study presentation ?

The best way to showcase data in a case study presentation is through visual aids like charts, graphs and infographics which make complex information easily digestible, engaging and creative.

Don’t just report results, visualize them! This template for example lets you transform your social media case study into a captivating infographic that sparks conversation.

Choose the type of visual that best represents the data you’re showing; for example, use bar charts for comparisons or pie charts for parts of a whole.

Ensure that the visuals are high-quality and clearly labeled, so the audience can quickly grasp the key points.

Keep the design consistent and simple, avoiding clutter or overly complex visuals that could distract from the message.

Choose a template that perfectly suits your case study where you can utilize different visual aids for maximum impact.

Need more inspiration on how to turn numbers into impact with the help of infographics? Our ready-to-use infographic templates take the guesswork out of creating visual impact for your case studies with just a few clicks.

Related: 10+ Case Study Infographic Templates That Convert

Congrats on mastering the art of compelling case study presentations! This guide has equipped you with all the essentials, from structure and nuances to avoiding common pitfalls. You’re ready to impress any audience, whether in the boardroom, the classroom or beyond.

And remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Venngage’s Case Study Creator is your trusty companion, ready to elevate your presentations from ordinary to extraordinary. So, let your confidence shine, leverage your newly acquired skills and prepare to deliver presentations that truly resonate.

Go forth and make a lasting impact!

Discover popular designs

Infographic maker

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

9 Creative Case Study Presentation Examples & Templates

Learn from proven case study presentation examples and best practices how to get creative, stand out, engage your audience, excite action, and drive results.

9 minute read

helped business professionals at:

Short answer

What makes a good case study presentation?

A good case study presentation has an engaging story, a clear structure, real data, visual aids, client testimonials, and a strong call to action. It informs and inspires, making the audience believe they can achieve similar results.

Dull case studies can cost you clients.

A boring case study presentation doesn't just risk putting your audience to sleep—it can actuallyl ead to lost sales and missed opportunities.

When your case study fails to inspire, it's your bottom line that suffers.

Interactive elements are the secret sauce for successful case study presentations.

They not only increase reader engagement by 22% but also lead to a whopping 41% more decks being read fully , proving that the winning deck is not a monologue but a conversation that involves the reader.

Let me show you shape your case studies into compelling narratives that hook your audience and drive revenue.

Let’s go!

How to create a case study presentation that drives results?

Crafting a case study presentation that truly drives results is about more than just data—it's about storytelling, engagement, and leading your audience down the sales funnel.

Here's how you can do it:

Tell a story: Each case study should follow a narrative arc. Start with the problem, introduce your solution, and showcase the results. Make it compelling and relatable.

Leverage data: Hard numbers build credibility. Use them to highlight your successes and reinforce your points.

Use visuals: Images, infographics, and videos can enhance engagement, making complex information more digestible and memorable.

Add interactive elements: Make your presentation a two-way journey. Tools like tabs and live data calculators can increase time spent on your deck by 22% and the number of full reads by 41% .

Finish with a strong call-to-action: Every good story needs a conclusion. Encourage your audience to take the next step in their buyer journey with a clear, persuasive call-to-action.

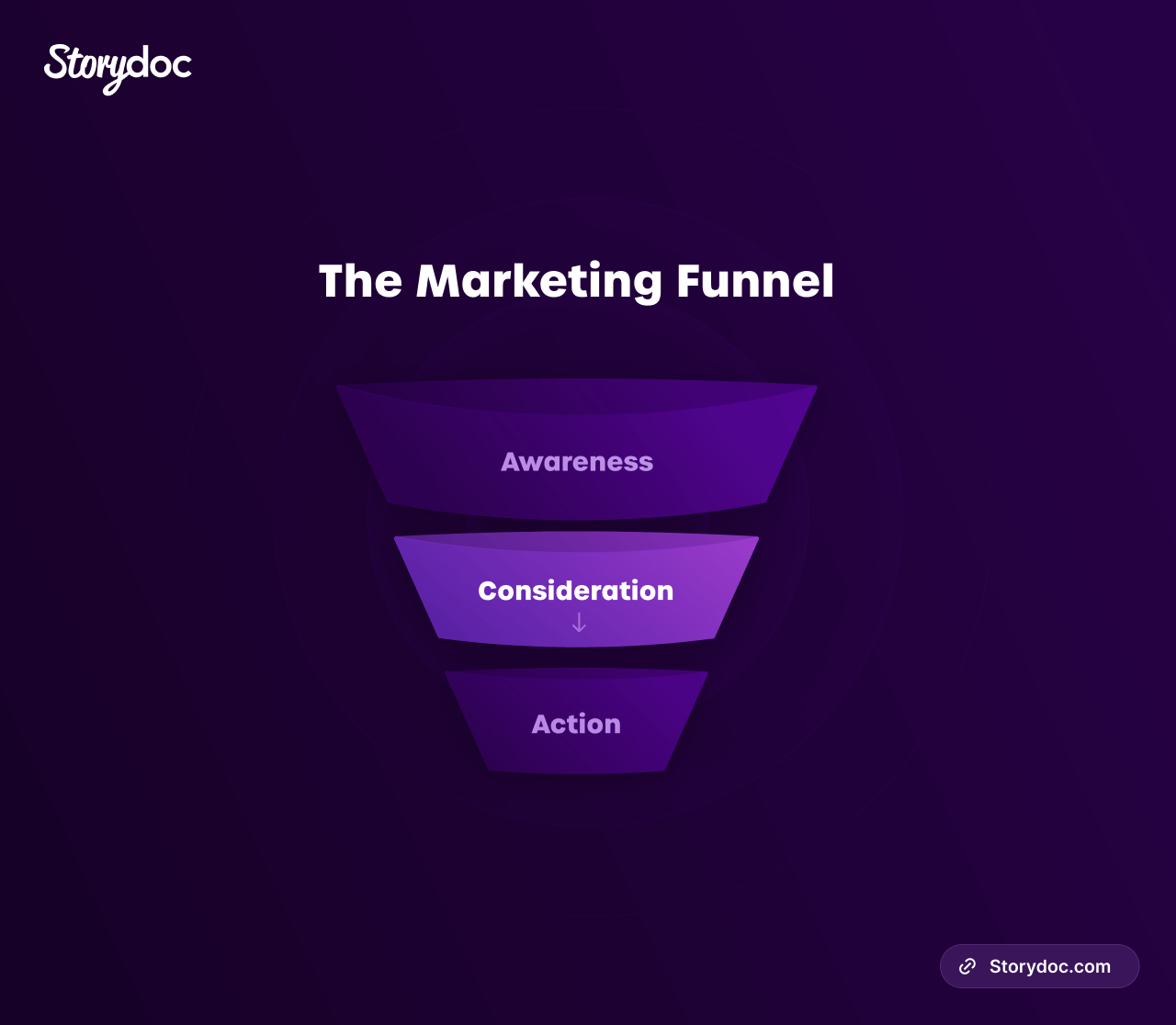

Visual representation of what a case study presentation should do:

How to write an engaging case study presentation?

Creating an engaging case study presentation involves strategic storytelling, understanding your audience, and sparking action.

In this guide, I'll cover the essentials to help you write a compelling narrative that drives results.

What is the best format for a business case study presentation?

4 best format types for a business case study presentation:

- Problem-solution case study

- Before-and-after case study

- Success story case study

- Interview style case study

Each style has unique strengths, so pick one that aligns best with your story and audience. For a deeper dive into these formats, check out our detailed blog post on case study format types .

What to include in a case study presentation?

An effective case study presentation contains 7 key elements:

- Introduction

- Company overview

- The problem/challenge

- Your solution

- Customer quotes/testimonials

To learn more about what should go in each of these sections, check out our post on what is a case study .

How to motivate readers to take action?

Based on BJ Fogg's behavior model , successful motivation involves 3 components:

This is all about highlighting the benefits. Paint a vivid picture of the transformative results achieved using your solution.

Use compelling data and emotive testimonials to amplify the desire for similar outcomes, therefore boosting your audience's motivation.

This refers to making the desired action easy to perform. Show how straightforward it is to implement your solution.

Use clear language, break down complex ideas, and reinforce the message that success is not just possible, but also readily achievable with your offering.

This is your powerful call-to-action (CTA), the spark that nudges your audience to take the next step. Ensure your CTA is clear, direct, and tied into the compelling narrative you've built.

It should leave your audience with no doubt about what to do next and why they should do it.

Here’s how you can do it with Storydoc:

How to adapt your presentation for your specific audience?

Every audience is different, and a successful case study presentation speaks directly to its audience's needs, concerns, and desires.

Understanding your audience is crucial. This involves researching their pain points, their industry jargon, their ambitions, and their fears.

Then, tailor your presentation accordingly. Highlight how your solution addresses their specific problems. Use language and examples they're familiar with. Show them how your product or service can help them reach their goals.

A case study presentation that's tailor-made for its audience is not just a presentation—it's a conversation that resonates, engages, and convinces.

How to design a great case study presentation?

A powerful case study presentation is not only about the story you weave—it's about the visual journey you create.

Let's navigate through the design strategies that can transform your case study presentation into a gripping narrative.

Add interactive elements

Static design has long been the traditional route for case study presentations—linear, unchanging, a one-size-fits-all solution.

However, this has been a losing approach for a while now. Static content is killing engagement, but interactive design will bring it back to life.

It invites your audience into an evolving, immersive experience, transforming them from passive onlookers into active participants.

Which of these presentations would you prefer to read?

Use narrated content design (scrollytelling)

Scrollytelling combines the best of scrolling and storytelling. This innovative approach offers an interactive narrated journey controlled with a simple scroll.

It lets you break down complex content into manageable chunks and empowers your audience to control their reading pace.

To make this content experience available to everyone, our founder, Itai Amoza, collaborated with visualization scientist Prof. Steven Franconeri to incorporate scrollytelling into Storydoc.

This collaboration led to specialized storytelling slides that simplify content and enhance engagement (which you can find and use in Storydoc).

Here’s an example of Storydoc scrollytelling:

Bring your case study to life with multimedia

Multimedia brings a dynamic dimension to your presentation. Video testimonials lend authenticity and human connection. Podcast interviews add depth and diversity, while live graphs offer a visually captivating way to represent data.

Each media type contributes to a richer, more immersive narrative that keeps your audience engaged from beginning to end.

Prioritize mobile-friendly design

In an increasingly mobile world, design must adapt. Avoid traditional, non-responsive formats like PPT, PDF, and Word.

Opt for a mobile-optimized design that guarantees your presentation is always at its best, regardless of the device.

As a significant chunk of case studies are opened on mobile, this ensures wider accessibility and improved user experience , demonstrating respect for your audience's viewing preferences.

Here’s what a traditional static presentation looks like as opposed to a responsive deck:

Streamline the design process

Creating a case study presentation usually involves wrestling with an AI website builder .

It's a dance that often needs several partners - designers to make it look good, developers to make it work smoothly, and plenty of time to bring it all together.

Building, changing, and personalizing your case study can feel like you're climbing a mountain when all you need is to cross a hill.

By switching to Storydoc’s interactive case study creator , you won’t need a tech guru or a design whizz, just your own creativity.

You’ll be able to create a customized, interactive presentation for tailored use in sales prospecting or wherever you need it without the headache of mobilizing your entire team.

Storydoc will automatically adjust any change to your presentation layout, so you can’t break the design even if you tried.

Case study presentation examples that engage readers

Let’s take a deep dive into some standout case studies.

These examples go beyond just sharing information – they're all about captivating and inspiring readers. So, let’s jump in and uncover the secret behind what makes them so effective.

What makes this deck great:

- A video on the cover slide will cause 32% more people to interact with your case study .

- The running numbers slide allows you to present the key results your solution delivered in an easily digestible way.

- The ability to include 2 smart CTAs gives readers the choice between learning more about your solution and booking a meeting with you directly.

Light mode case study

- The ‘read more’ button is perfect if you want to present a longer case without overloading readers with walls of text.

- The timeline slide lets you present your solution in the form of a compelling narrative.

- A combination of text-based and visual slides allows you to add context to the main insights.

Marketing case study

- Tiered slides are perfect for presenting multiple features of your solution, particularly if they’re relevant to several use cases.

- Easily customizable slides allow you to personalize your case study to specific prospects’ needs and pain points.

- The ability to embed videos makes it possible to show your solution in action instead of trying to describe it purely with words.

UX case study

- Various data visualization components let you present hard data in a way that’s easier to understand and follow.

- The option to hide text under a 'Read more' button is great if you want to include research findings or present a longer case study.

- Content segmented using tabs , which is perfect if you want to describe different user research methodologies without overwhelming your audience.

Business case study

- Library of data visualization elements to choose from comes in handy for more data-heavy case studies.

- Ready-to-use graphics and images which can easily be replaced using our AI assistant or your own files.

- Information on the average reading time in the cover reduces bounce rate by 24% .

Modern case study

- Dynamic variables let you personalize your deck at scale in just a few clicks.

- Logo placeholder that can easily be replaced with your prospect's logo for an added personal touch.

- Several text placeholders that can be tweaked to perfection with the help of our AI assistant to truly drive your message home.

Real estate case study

- Plenty of image placeholders that can be easily edited in a couple of clicks to let you show photos of your most important listings.

- Data visualization components can be used to present real estate comps or the value of your listings for a specific time period.

- Interactive slides guide your readers through a captivating storyline, which is key in a highly-visual industry like real estate .

Medical case study

- Image and video placeholders are perfect for presenting your solution without relying on complex medical terminology.

- The ability to hide text under an accordion allows you to include research or clinical trial findings without overwhelming prospects with too much information.

- Clean interactive design stands out in a sea of old-school medical case studies, making your deck more memorable for prospective clients.

Dark mode case study

- The timeline slide is ideal for guiding readers through an attention-grabbing storyline or explaining complex processes.

- Dynamic layout with multiple image and video placeholders that can be replaced in a few clicks to best reflect the nature of your business.

- Testimonial slides that can easily be customized with quotes by your past customers to legitimize your solution in the eyes of prospects.

Grab a case study presentation template

Creating an effective case study presentation is not just about gathering data and organizing it in a document. You need to weave a narrative, create an impact, and most importantly, engage your reader.

So, why start from zero when interactive case study templates can take you halfway up?

Instead of wrestling with words and designs, pick a template that best suits your needs, and watch your data transform into an engaging and inspiring story.

Hi, I'm Dominika, Content Specialist at Storydoc. As a creative professional with experience in fashion, I'm here to show you how to amplify your brand message through the power of storytelling and eye-catching visuals.

Found this post useful?

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Get notified as more awesome content goes live.

(No spam, no ads, opt-out whenever)

You've just joined an elite group of people that make the top performing 1% of sales and marketing collateral.

Create your best pitch deck to date.

Stop losing opportunities to ineffective presentations. Your new amazing deck is one click away!

Free PowerPoint Case Study Presentation Templates

By Joe Weller | January 23, 2024

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

We’ve collected the top free PowerPoint case study presentation templates with or without sample text. Marketing and product managers, sales execs, and strategists can use them to arrange and present their success stories, strategies, and results.

On this page, you'll find six PowerPoint case study presentation templates, including a marketing case study template , a problem-solution-impact case study , and a customer journey case study template , among others. Plus, discover the key components of successful case study presentations , find out the different types of case study presentations , and get expert tips .

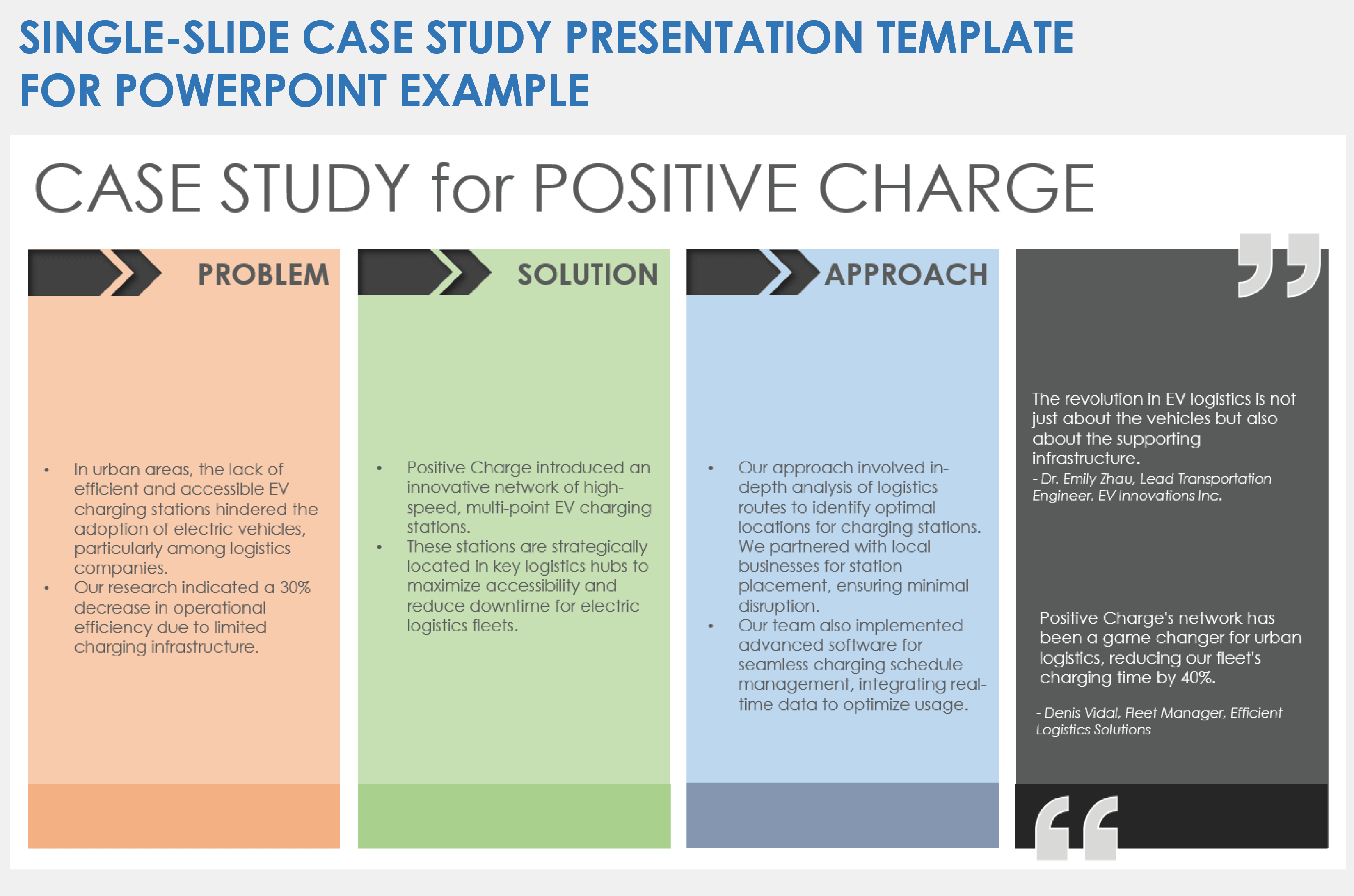

PowerPoint Single-Slide Case Study Presentation Template

Download the Sample Single-Slide Case Study Presentation Template for PowerPoint Download the Blank Single-Slide Case Study Presentation Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Use this single-slide case study presentation template when you need to give a quick but effective overview of a case study. This template is perfect for presenting a case study when time is limited and you need to convey key points swiftly.

Notable Template Features: You can fit everything you need on one slide. Download the version with sample text to see how easy it is to complete the template. Unlike more detailed templates, it focuses on the main points, such as the problem, solution, approach, and results, all in a compact format. It's great for keeping your audience focused on the key aspects of your case study without overwhelming them with information.

PowerPoint Marketing Case Study Template

Download the Sample Marketing Case Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Marketing Case Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Choose this marketing case study template when you need to dive deep into your marketing strategies and results. It's perfect for marketing managers and content marketers who want to showcase the detailed process and successes of their campaigns.

Notable Template Features: This template focuses on the detailed aspects of marketing strategies and outcomes. It includes specific sections to outline business needs, results, and strategic approaches.

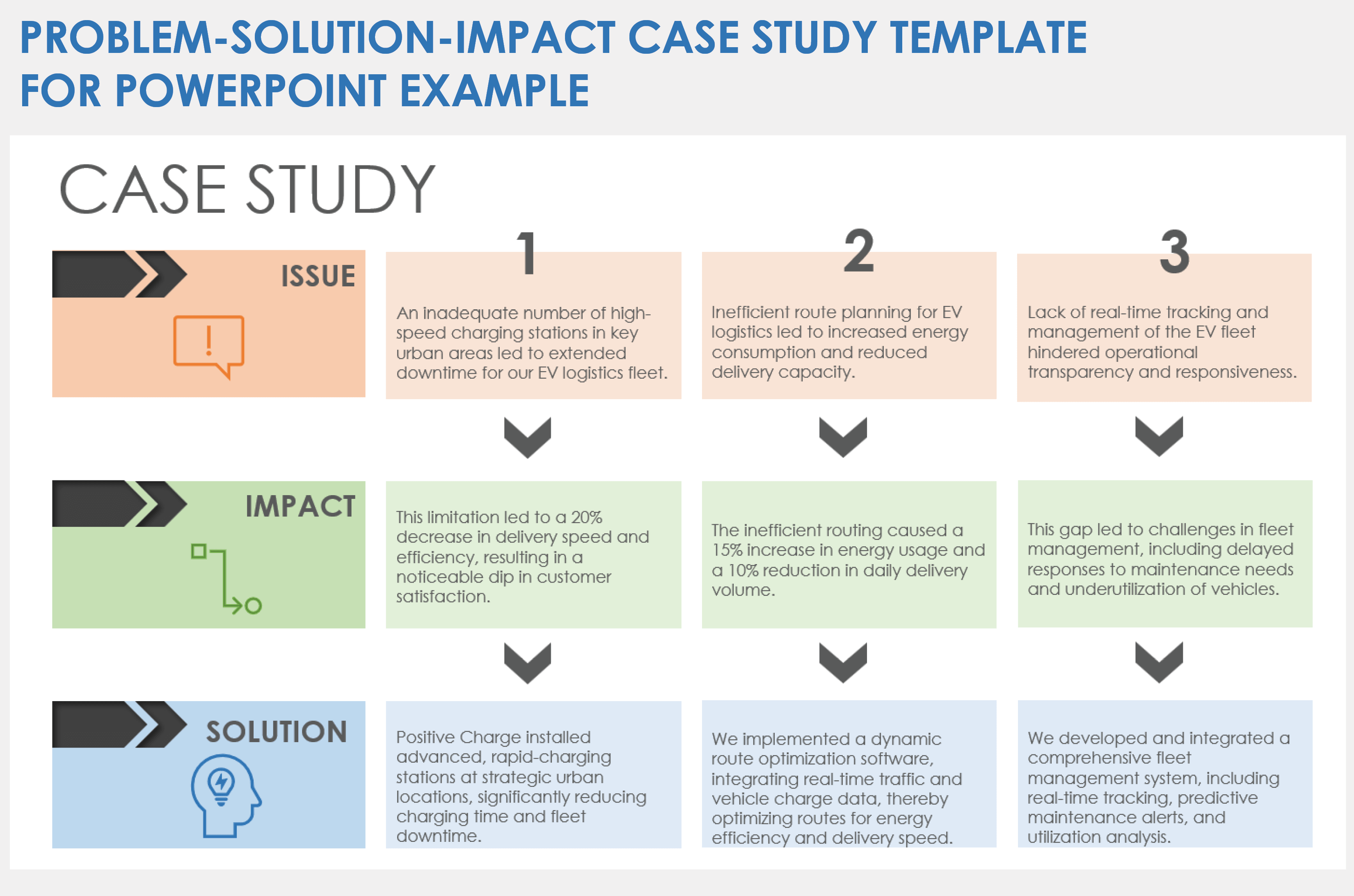

PowerPoint Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study Template

Download the Sample Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: This problem-solution-impact case study template is useful for focusing on how a challenge was solved and the results. Project managers and strategy teams that want to clearly portray the effectiveness of their solutions can take advantage of this template.

Notable Template Features: This template stands out with its clear structure that breaks down the case into problem, solution, and impact. Use the template — available with or without sample data — to help you tell a complete story, from the issue faced to the solution and its results, making it perfect for presentations that need to show a clear cause-and-effect relationship.

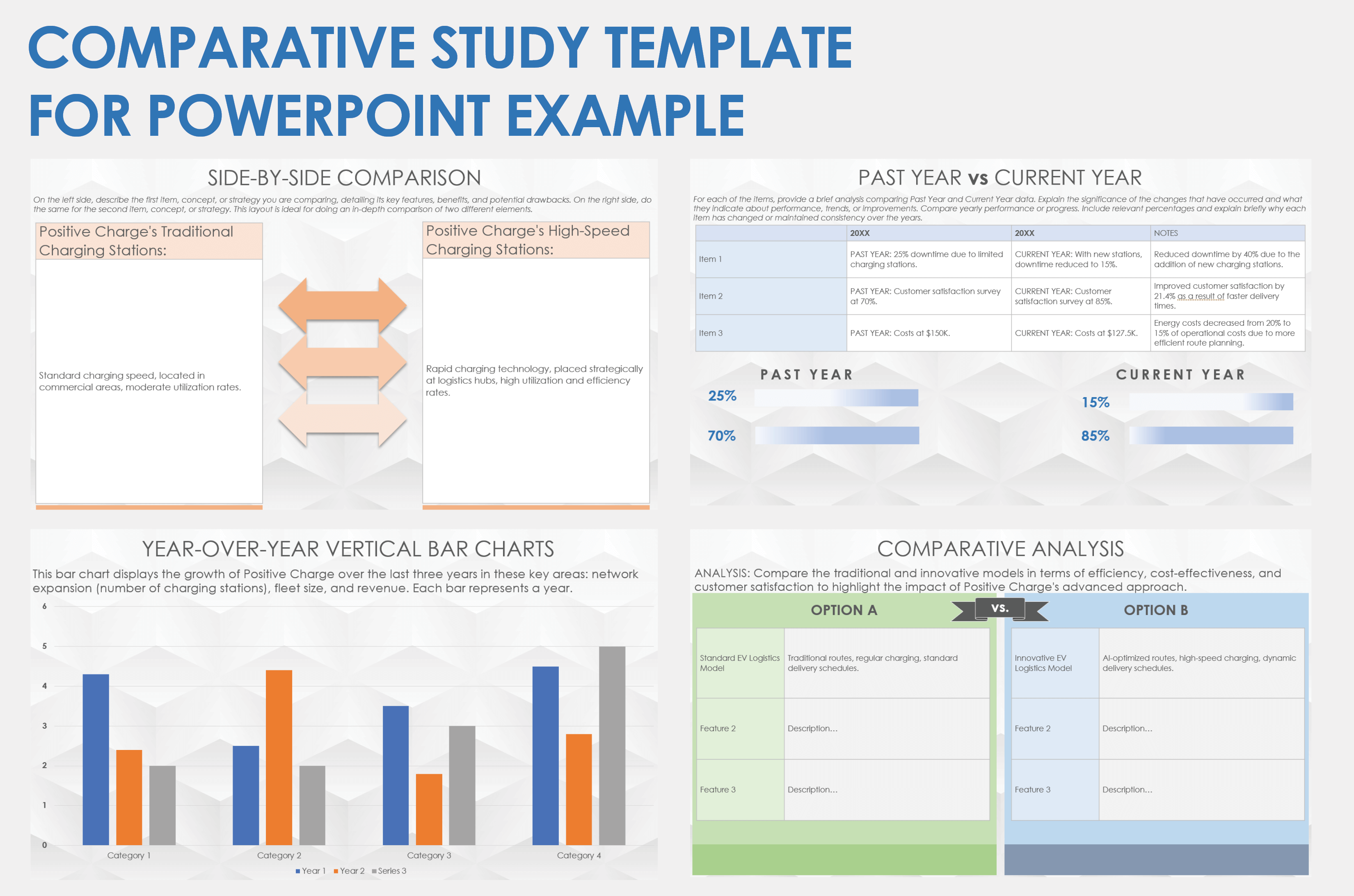

PowerPoint Comparative Study Template

Download the Sample Comparative Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Comparative Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Choose this comparative study template — available with or without sample data — to illuminate how different products, strategies, or periods stack up against each other. It's great for product managers and research teams who want to do side-by-side comparisons.

Notable Template Features: This template lets you put things next to each other to see their differences and similarities, with a focus on direct comparisons. Use the columns and split slides to make the content easy to understand and visually appealing, perfect for highlighting changes or different approaches.

PowerPoint Customer Journey Case Study Template

Download the Sample Customer Journey Case Study Template for PowerPoint

Download the Blank Customer Journey Case Study Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: This template is useful for customer experience managers and UX designers who need to understand and improve how customers interact with what they offer. Use the customer journey case study template with sample data to see how to show every step of a customer's experience with your product or service.

Notable Template Features: This template focuses on the whole path a customer takes with a product or service. It follows them, from first learning about the offering to after they buy it.

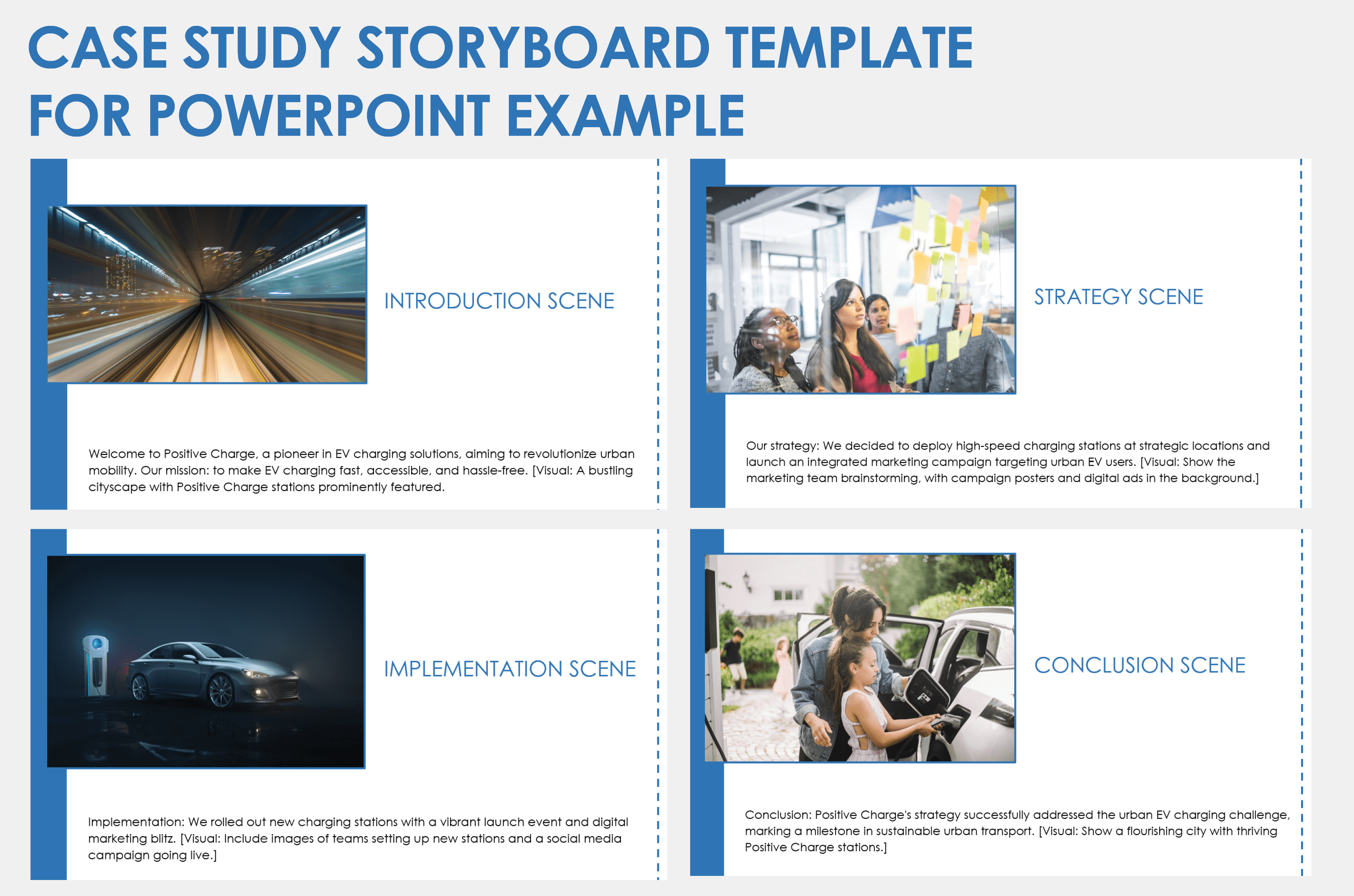

PowerPoint Case Study Storyboard Template

Download the Sample Case Study Storyboard Template for PowerPoint Download the Blank Case Study Storyboard Template for PowerPoint

When to Use This Template: Creative teams and ad agencies should use this case study storyboard template — with or without sample data — to tell a story using more images than text.

Notable Template Features: This template transforms a case study into a visual story. Effectively communicate the journey of a business case, from the challenges faced to the solutions implemented and the results achieved.

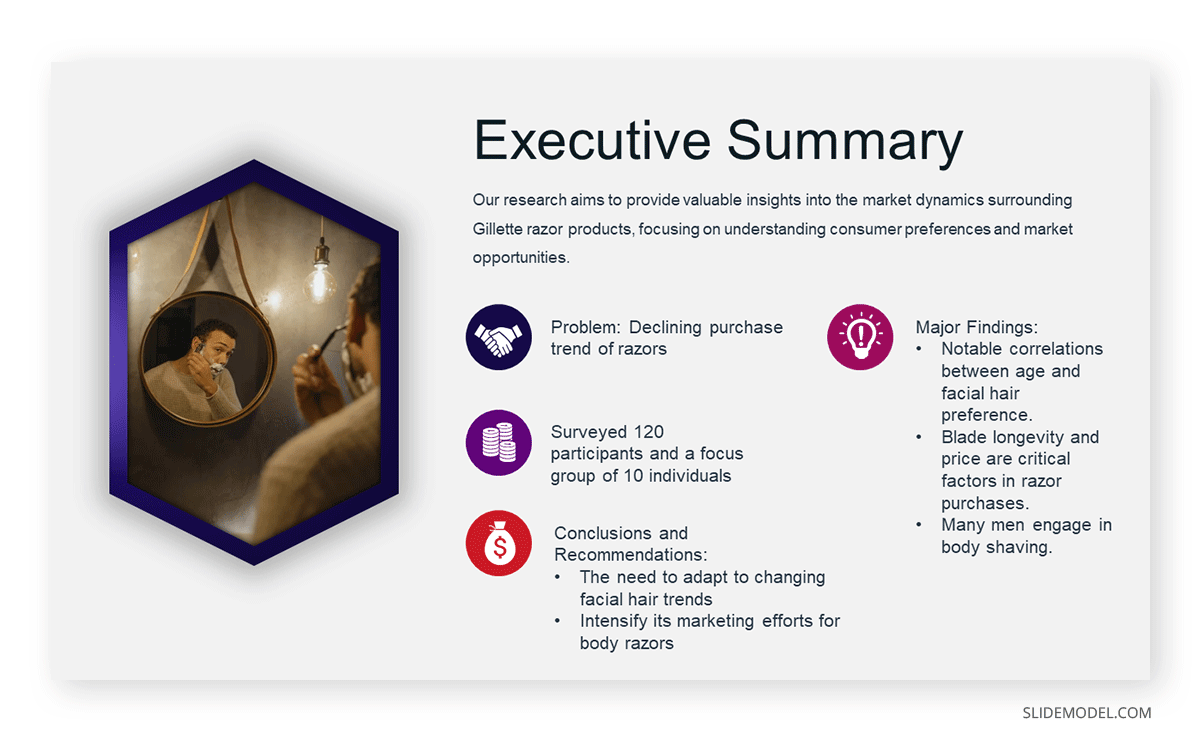

Key Components of Successful Case Study Presentations

The key components of successful case study presentations include clear goals, engaging introductions, detailed customer profiles, and well-explained solutions and results. Together they help you present how your strategies succeed in real-world scenarios.

The following components are fundamental to crafting a compelling and effective marketing case study presentation:

- Clear Objective: Define the goal of your case study, ensuring it addresses specific questions or goals.

- Engaging Introduction: Start with an overview of the company, product, or service, as well as the context to provide necessary background information.

- Customer Profile: Detail your target customer demographics and their needs to help the audience understand who the marketing efforts are aimed at and their relevance.

- The Challenge: Clearly articulate the primary problem or issue to overcome to establish the context for the solution and strategy, highlighting the need for action.

- Solution and Strategy: Describe the specific strategies and creative approaches used to address the challenge. These details should demonstrate your approach to problem-solving and the thought process behind your decisions.

- Implementation: Explain how the solution was put into action to show the practical application. This description should bring your strategy to life, allowing the audience to see how you executed plans.

- Results and Impact: Present measurable outcomes and impacts of the strategy to validate and show its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

- Visual Elements: Use charts, images, and infographics to make complex information more accessible and engaging, aiding audience understanding.

- Testimonials and Quotes: Include customer feedback or expert opinions to add credibility and a real-world perspective, reinforcing your strategy’s success.

- Lessons Learned and Conclusions: Summarize key takeaways and insights gained to show what the audience can learn from the case study.

- Call to Action (CTA): End with an action you want the audience to take to encourage engagement and further interaction.

Different Types of Case Study Presentations

The types of case study presentations include those that compare products, showcase customer journeys, or tell a story visually, among others. Each is tailored to different storytelling methods and presentation goals.

The following list outlines various types of case study presentations:

- Problem-Solution-Impact Case Study: This type focuses on a clear narrative structure, outlining the problem, solution implemented, and final impact. It's straightforward and effective for linear stories.

- Comparative Case Study: Ideal for showcasing before-and-after scenarios or comparisons between different strategies or time periods. This option often uses parallel columns or split slides for comparison.

- Customer Journey Case Study: Centered on the customer's experience, this option maps out their journey from recognizing a need to using the product or service, and the benefits they gained. It's a narrative-driven and customer-focused case study format.

- Data-Driven Case Study: Emphasizing quantitative results and data, this format is full of charts, graphs, and statistics. This option is perfect for cases where numerical evidence is the main selling point.

- Storyboard Case Study: Use this type to lay out the case study in a storytelling format. This option often relies on more visuals and less text. Think of it as a visual story, engaging and easy to follow.

- Interactive Case Study: Designed with clickable elements for an interactive presentation, this type allows the presenter to dive into different sections based on audience interest, making it flexible and engaging.

- Testimonial-Focused Case Study: This format is best for highlighting customer testimonials and reviews. It leverages the power of word of mouth and is highly effective in building trust.

Expert Tips for Case Study Presentations

Expert tips for case study presentations include knowing your audience, telling a clear story, and focusing on the problem and solution. They can also benefit from using visuals and highlighting results.

“Case studies are one of the most powerful tools in an organization’s marketing arsenal,” says Gayle Kalvert, Founder and CEO of Creo Collective, Inc. , a full-service marketing agency. “Done correctly, case studies provide prospective buyers with proof that your product or service solves their business problem and shortens the sales cycle.”

“Presentations are probably the most powerful marketing asset, whether for a webinar, a first meeting deck, an investor pitch, or an internal alignment/planning tool,” says marketing expert Cari Jaquet . “Remember, the goal of a case study presentation is not just to inform, but also to persuade and engage your audience.”

Use these tips to make your presentation engaging and effective so that it resonates with your audience:

- Know Your Audience: Tailor the presentation to the interests and knowledge level of your audience. Understanding what resonates with them helps make your case study more relevant and engaging. “Presentations can also be a forcing function to define your audience, tighten up your mission and message, and create a crisp call to action,” explains Jaquet.

- Tell a Story: Structure your case study like a story, with a clear beginning (the problem), middle (the solution), and end (the results). A narrative approach keeps the audience engaged.

- Focus on the Problem and Solution: Clearly articulate the problem you addressed and how your solution was unique or effective. This section is the core of a case study and should be given ample attention.

- Use Data Wisely: Incorporate relevant data to support your points, but avoid overwhelming the audience with numbers. Use charts and graphs for visual representation of data to make it more digestible.

- Highlight Key Results: Emphasize the impact of your solution with clear and quantifiable results. This could include increased revenue, cost savings, improved customer satisfaction, and similar benefits.

- Incorporate Visuals: Use high-quality visuals to break up text and explain complex concepts. Consider using photos, infographics, diagrams, or short videos. “I put together the graphics that tell the story visually. Speakers often just need a big image or charts and graphs to help guide their talk track. Of course, if the audience expects details (for example, a board deck), the graphic helps reinforce the narrative,” shares Jaquet.

- Include Testimonials: Adding quotes or testimonials from clients or stakeholders adds credibility and a real-world perspective to your presentation.

- Practice Storytelling: A well-delivered presentation is as important as its content. Practice your delivery to ensure you are clear, concise, and engaging. At this point, it also makes sense to solicit feedback from stakeholders. Jaquet concurs: “Once my outline and graphics are in place, I typically circulate the presentation draft for review. The feedback step usually surfaces nuances in the story or key points that need to show up on the slides. There is no point in building out tons of slides without alignment from the speaker or subject matter experts.”

- End with a Strong Conclusion: Summarize the key takeaways and leave your audience with a final thought or call to action.

- Seek Feedback: After your presentation, request feedback to understand what worked well and what could be improved for future presentations.

“Don't underestimate the power of a great presentation. And don't wait until the last minute or try to invent the wheel on your own,” advises Jaquet. “Many times, getting the next meeting, winning the deal, or getting the project kicked off well, requires your audience to understand and believe your story.”

Streamline and Collect All the Elements Needed for a Case Study with Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

Table of Contents 💡

Home - UX Portfolio - Tips on presenting your UX case study

Tips on presenting your UX case study

Imagine this. You’ve made it through the first job interview. You’re now asked for a second round interview to show your work. But how? And what do you need to keep in mind? Here’s how to present a UX case study during a job interview.

- Updated on May 9, 2024

This article will teach you how to present your UX case study during a job interview. If you follow along, you’ll increase your chances of getting invited to the next round. We’ll talk about the basics, such as attending the meeting on time, and more advanced tactics, like how you structure your presentation.

I’ve based the following tips on presenting my UX portfolio to multiple potential clients for years and the UX mentorships I’ve hosted for aspiring designers. In other words, these tips are based on real-world experience.

Table of Contents

How to present a ux case study.

The most important aspect of giving an excellent UX case study presentation is showing that you can solve a business challenge.

Even though your main goal is to be there for the user, you can’t forget that you’re hired by a business to help that business make money. If you only talk about users and forget to mention how you can help your potential employer grow a business, you’re likely to miss out.

Then there are also some basic job interview rules to consider. Let’s discuss those basics first.

Presentation basics

These basics are essential. People expect you to follow them. Because of that, doing so will not get you any bonus points. However, failing to follow the basics will leave a bad taste during your interview. Make sure you can check the following basics off of your list.

- Arrive on time.

- Stable internet connection (remote only).

- Position yourself in the middle of your frame (remote only).

- Make sure you’re able to focus without disturbance (remote only).

- Make sure your camera and mic are working correctly (remote only).

At some point during the interview, the interviewer will ask you to present your work. This means you can choose which of your case studies to pick. And that’s a good thing.

In my experience, there’s always a case study you prefer over your other case studies. Creating that particular UX case study has been easier, or the project has been more fun than your other projects.

So make sure you’re ready to pick one of your case studies on the spot if asked to. Pick the one you’re most comfortable with.

Start with a case study summary

Once you’re asked to present your UX portfolio, it makes sense to start explaining everything you’ve done. Try and stay away from doing that.

You’ll lose the attention of your crowd and put yourself in a position to receive challenging questions you can’t answer. Instead, give a summary first. Here’s what to include.

- The business challenge, what you were asked to do, and your role.

- What your main deliverable was.

- The results of your project and deliverable.

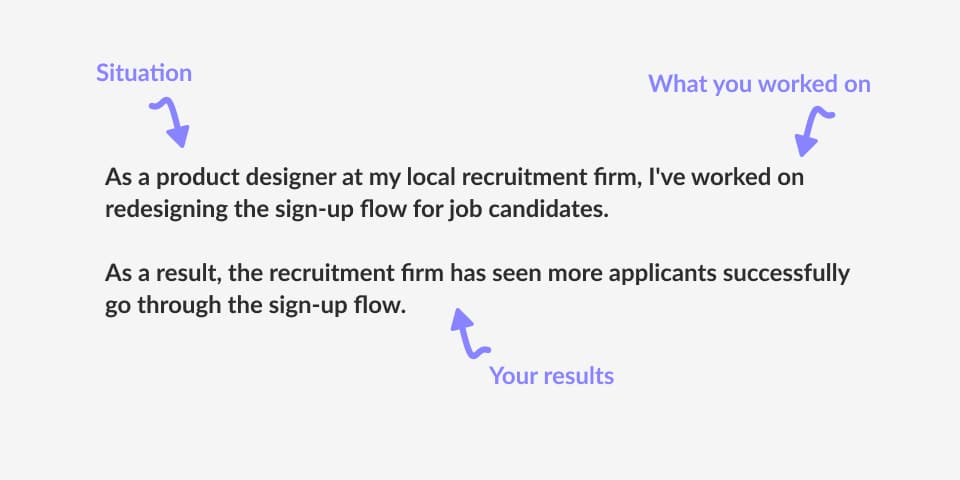

Here’s an example of what your UX case study summary might look like.

As a product designer at my local recruitment firm, I’ve worked on redesigning the sign-up flow for job candidates. As a result, the recruitment firm has seen more applicants successfully go through the sign-up flow.

This is a very short summary. And by doing so, you give those listening to your presentation the opportunity to ask questions. Because you keep a lot of information to yourself, chances are you get questions about that information. You can answer these questions with ease.

If you had presented every detail of your case study, you’re more likely to get questions you can’t answer.

Answering case study questions

After presenting your UX case study summary, it is time to answer questions. As I said, you leave room for questions on purpose to have more control over the type of questions you get.

My main advice here is to be honest when you don’t have an answer to one of the questions. I’ve seen many designers desperately try to answer every question they get. However, the people listening to your presentation will notice this.

Instead, be honest when you’re not sure. Let your audience know you’re willing to learn or return the question by asking what they think or what the company expects you to do.

That way, you show you know what you can improve and that you’re willing to have a good talk about it. That’s way more valuable than being someone that pretends to know everything.

Frequently asked questions

With the above structure, presenting your UX case study during a job interview should go much better. However, there are still some questions to be answered. I’ve collected several in the list below.

How long should a UX case study presentation be?

The length of your case study presentation depends on the structure of the interview. In almost all cases, that’s up to the hiring company. It is common for an interview to take between 30 and 60 minutes.

However, your UX case study presentation can be shorter than that. Those 30 or 60 minutes include the introduction, asking questions, and discussing the next steps as well. That leaves between 5 to 15 minutes for the actual case study presentation.

How many slides are in a UX case study presentation?

The number of slides in your UX case study can vary between 5 and 15. Less than that would mean that you don’t include the basics like the cover page, challenge, things you’ve done during the project, and your results.

However, when you go over 15 slides, you risk losing your audience’s attention. Be strict in the number of slides you include!

What should a UX presentation include?

Your presentation should include at least the main building blocks of your project. These include the business problem you’re solving, what the client has asked you to do, what you actually did, and the impact of your work.

Try making it very visual with mockups, photos of you working on the project, and a user testimonial from your tests. Before and after images also help you tell a better story.

UX Case Study (Course + Template)

I’ll walk you through the steps of creating a case study based on my 10 years of experience in UX.

- Video course and template.

- Includes real-world examples.

- Get personal feedback.

Case studies are what make up most of your UX portfolio. Therefore, being able to present them is a crucial skill you need to have when you want to get hired in UX .

These crucial steps will increase your chances of making it to the next round.

- Get the basics right. Make sure you’re on time, in a place where you can focus, and with a stable internet connection.

- Start with a summary of your case study to leave room for questions you can answer.

- Accept the fact that you can’t answer everything. It is better to acknowledge that than to try and desperately answer every question you get.

Do you have feedback on this article? Missing something? Or just a question? Reach out to me and I’ll get back to you!

About the author

Hi! I'm Nick Groeneveld , a senior designer from the Netherlands with experience in UX, visual design, and research. I'm a UX coach that supports other designers and have completed design projects in finance, tech, and the public sector.

Through The Designer's Toolbox, I'm an Educational Partner for Interaction Design Foundation.

☎️ Book a 1:1 mentor meeting with me or let's connect on LinkedIn , Twitter and Medium .

Get 3 months of free membership on IxDF when you join.

Complete a Figma course and get a certificate

Join our community & learn more about this topic.

Participate in weekly Q&A’s, live portfolio reviews, and more when you join our community of designers. Join here! 👇

$36 billed annually

Join our Slack community

Weekly UX Q&A’s

UX Career Track

$72 billed annually

Everything in Community, plus...

Join two UX master classes per month

Access to all UX master class recordings

Private Slack channel for async career support

20% discount on 1:1 UX coaching

Lifetime access

One-time payment

Access to our community and everything it includes.

Not a subscription. Pay once, join forever.

Our best seller 💪

Step-by-step guide to getting hired in UX

Our resources 💡

Community, books, guides, mentorship, and more

Join 1,400+ designers building a career in UX

Every week, you’ll get one actionable tip from the UX Career Track to help you get hired and build a career in UX.

We respect your privacy. Unsubscribe at any time.

The Designer's Toolbox

The Designer’s Toolbox helps you get hired in UX and UI Design. We’re your collection of design community, tips, tricks, and best practices.

About The Designer’s Toolbox

UX Equipment

UX Design Tools

Build your UX portfolio

Get a job in UX

For brands and companies

Work with us

The UX Jobs Handbook

UX Job Board

All resources

© 2024 All rights Reserved by the Designer's Toolbox

Privacy policy

UX Case Study Presentation Template

What you'll get

Used by designers and teams from, product overview.

- Without a solid structure, presenting a UX case study can feel disjointed or scattered. Designers also often struggle to pinpoint the most impactful highlights of their work.

- Our UX Case Study Presentation Template captures all the important details. It gives you a clear guide to confidently show off your work, even in stressful situations like job interviews.

- Quickly set up your UX case studies and remove the repetitive work of creating new documents. This template organizes your content to tell a polished story that showcases your successes.

- Customize your presentation with preset elements for consistency. Use sections to define problems, identify insights, and propose solutions.

- A well-crafted UX case study presentation can help you land new opportunities. Turn your UX case studies into a powerful narrative that impresses clients and stakeholders.

How will it help me?

- Set up your document in seconds: Get everything you need in one straightforward template. There's no need to keep creating the same document for every new case study

- Organize content effortlessly: Sort all the information you need with pages neatly arranged

- Improve your workflow: Work smarter with a professional presentation that showcases your attention to detail

- Keep it all consistent: Build the presentation to fit your brand's identity. Customize your style with color schemes, typefaces, and more

- Template pages: Capture your UX case study in 22 pre-designed pages to guide your study

- Presentation-ready slides: Present anytime with responsive slides and a 16:9 ratio

- Customizable style guide: Keep your presentations on-brand by customizing color schemes, fonts, and more

- Well-defined sections: Identify key information with sections for problems, insights, solutions, and conclusions

- Structured content: Essential elements for a strong presentation in a fuss-free, straightforward design

- Easy navigation: Form seamless narratives with content flow arranged logically

Requirements

- A basic understanding of UX/UI design principles and Figma

- A desire to improve your case study presentations

- A laptop or desktop computer with steady internet access

- A Figma account (recommended)

Who is this product for?

Students & Junior Designers

Kickstart your design career with a professional and well-organized template.

Senior Designers

Highlight your design expertise by showcasing your work's depth and attention to detail.

Independent Freelancers

Win over new clients and secure more projects with a polished, cohesive presentation.

Design Teams & Startups

Showcase your team's achievements in a compelling and streamlined narrative.

What to expect from a Designership product

Frequently bought together.

Practical UX Research & Strategy

Figma Annotation Kit

Testimonials.

Variety matters. A wider selection of component variants to work with ensures a broader audience gets the best possible experience. That’s why Shipfaster UI 2.5 is packed with new components, even more variants, and refined states.

- Updated icon set in the latest heroicon

- New "labels" text style in typography foundation to differentiate from paragraphs and headings

- More grid layouts for a responsive guide to sidebar grids

- More sizes and enhanced colors for Focused rings

- New flag resource with complete country names and ISO

- Added updated social and media logo icons

- New pie chart components

- New chip components

- New video player components

- More variant styles and enhanced states for accordions

- More variant styles for badges

- More variant styles and enhanced states for breadcrumbs

- New icon, social, and social group components for buttons

- New organizational components and templates for data display

- New and specific date and time picker with more variants

- More variant styles and enhanced states for file uploads

- More variant styles and enhanced states for form control

- More variant styles and enhanced states for inline alerts

- Enhanced states, layout and component properties for input fields

- More variant styles and enhanced states for loaders

- More variant styles and enhanced states for progress bars

- Marketing pages samples now have all responsive views from desktop to mobile

Shipfaster UI v.2.5 is updated just for you. We aim to bring you an elevated design experience with regular design system updates. Be the first to know about the latest news and changes to Shipfaster UI by subscribing to our newsletter.

Meet Shipfaster UI v2.6: Your new and improved design UI kit! 🚀 We've upgraded our components and added user-friendly variants to simplify your design process. Get ready for clearer labels, more dynamic states, and a sleeker interface. Plus, we've fixed the small issues and made finding icons a breeze.

Shipfaster UI v2.6 is all about making your design work faster and easier. Speed up your workflow—see the changes below.

- Improvement and configuration of all the main components

- Refined semantic naming and dynamic states

- New & improved variants for:

- Progress Step and Progress Bar

- Input Fields

- A new set of icons for File Formats

- Improved semantic naming and states

- New header variants in the marketing samples

- Modified neutrals for better contrast and compatibility with our main primary color

- Improved Video Player component

- Fixed missing component properties and variants

- Descriptions and tags for easier searching of icons

- New and refined visuals for marketing sections

- Off-site component documentation

Shipfaster UI v.2.6 is updated just for you. We aim to bring you an elevated design experience with regular design system updates. Be the first to know about the latest news and changes to Shipfaster UI by subscribing to our newsletter.

We realised there was a small issue with some members not being able to load all the images in the design file. What we have learnt is that Figma is a browser-based app which means it’s subjected to a 2GB available memory limit that applies to each browser tab, including those in the desktop app. When loading or editing Figma files nears or or exceeds this memory limit, it can cause performance issues like long load times, crashes and others. Please keep in mind when using our design system, to limit the number of browser tabs you have opened.

- Updated file thumbnails.

- Moved checkboxes, radio buttons and toggles into a new section called Form Controls.

- Compressed all JPG images in the file to reduce file size.

- Members that raised images not loading have confirmed this has solved their issues.

A few members reported seeing ‘3 missing libraries’ upon importing the design system.

- Fixed mission libraries issue.

Figma made some major updates to their platform in May 2022. This included component properties, a re-designed Autolayout, dark mode and much more. In v.2.3 of Shipfaster UI, we have decided to introduce a number of updates that have helped improve the kit’s performance and it’s relevancy with the latest updates.

- Removed .styled components to improve the performance of our design system.

- Updated all components with the new component properties and Autolayout feature.

- Updated all templates with the revised components.

- Migrated our icon system from ‘component variants’ to individual components, to allow for an improved toggling experience.

- Added tablet and mobile versions for all templates.

- Provided pre-designed templates for quick use.

- Included a Shipfaster Starter template for anyone that wants to use a lighter version of our design system.

With Shipfaster 2.4, we’ve focused on adding new styles and components in the Foundation section. There are new secondary color ranges, graphic elements and an all new featured Mockup page to supercharge the way you present your designs. We’ve fine-tuned every detail in v.2.4 of Shipfaster UI to help elevate your designs and keep up with the latest trends in the industry.

- 10 new linear palette gradient options

- 10 new mesh gradient palette options

- Enhance Shadows to complement UI designs with natural-looking shadows

- New blurred option (XXL) for Blurs

- New 3D graphic elements to enhance your designs visuals

- New divider lines to create spaces and sections in your designs

- An all-new dedicated Mockup page which includes:

- Credit card

- iPhone 14 Pro

- Screen Mock Up

- iPad landscape & portrait

- Macbook Pro

- New avatar components including:

- Integrated avatar icons with indicator for badges, status, and notifications

- Shape variant for the master component to easily switch up avatar shape

- New breadcrumb variants with updated indicators

- Updated designed marketing sections and pages with all new mock-ups and avatars, new secondary color palette (with over 12 color ranges) for more color options

Today we’re excited to announce the launch of our Shipfaster UI - A Figma Design System 2.0 🎉 This is our first major upgrade and overhaul to our design system.

- 150+ new global design styles.

- 2,800+ new media assets.

- 6,000+ components and variants.

- 140+ template examples.

- Written instructions for every key component.

- Master components provided with all primary components.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What's the ux case study presentation template for.

The UX Case Study Presentation Template from Designership is a template that helps designers explain their work clearly and confidently in job interviews or meetings. It guides you to organize your design steps, choices, and results in an engaging way.

Is the UX Design Case Study Template free?

Yes, this is a premium template that Designership provides to help you give your project presentations a professional and consistent look.

Can I customize the UX Case Study Template to fit my brand's identity?

Absolutely. You can easily customize the UX Case Study Template to match your own brand, including your colors, fonts, and style, to make it truly yours.

How many sections does the UX Case Study Presentation Template have?

Our UX Case Study Presentation Template comes with organized sections to define problems, insights, solutions, and conclusions. This is so that you don't miss any key details in your presentations. It has everything need to cover every part of your case study.

Can I use the UX Case Study Template in Figma?

Yes, this template works in Figma.

How will the template help organize my case study?

The template gives you a clear outline to follow. It guides you through each step of your case study, from the challenges and solutions to the methods you used and the results you achieved. That way, you tell a clear story of your project.

What sets this UX Case Study Template apart from other templates found online?

Our UX Case Study Template is crafted to help you tell the story of your project in a compelling way. It's designed for easy customization, thanks to expert input from Michael Wong (Mizko).

Do I need any specific software to use the UX Case Study Presentation Template?

It's best to use this template in Figma to get the most out of its features, but it's also made to be flexible enough for use with other design tools.

How can I learn UX Research?

A quick Google or Youtube search can teach the theory behind UX research. But if you want to apply what you learn in the workplace, take our Practical UX Research & Strategy Course. Learn how to apply tactical UX research strategy to your designs and make better-informed decisions. This course takes you through the entire UX research process, from planning your research strategy to getting insights from participants and presenting data-backed design solutions. By the end of the course, you'll be able to deliver business-driven designs and gain the confidence of stakeholders and clients with actionable insights and clear strategies.

Start designing today!

Enter your email address to receive the resource file.

Master highly-demanded skills in hours not weeks

Ultimate Figma Mastery

Ux research & strategy.

UX/UI Design Course

Fast-track your design process.

Shipfaster UI: Figma UI Kit & Design System

Join our newsletter

Get 10% off on your first purchase

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

10 Successful Design Thinking Case Study

Dive into the realm of Successful Design Thinking Case Studies to explore the power of this innovative problem-solving approach. Begin by understanding What is Design Thinking? and then embark on a journey through real-world success stories. Discover valuable lessons learned from these case studies and gain insights into how Design Thinking can transform your approach.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Leadership Skills Training

- Instructional Design Training

- Design Thinking Course

- Business Development Training

- Leadership and Management Course

Design Thinking has emerged as a powerful problem-solving approach that places empathy, creativity, and innovation at the forefront. However, if you are not aware of the power that this approach holds, a Design Thinking Case Study is often used to help people address the complex challenges of this approach with a human-centred perspective. It allows organisations to unlock new opportunities and drive meaningful change. Read this blog on Design Thinking Case Study to learn how it enhances organisation’s growth and gain valuable insights on creative problem-solving.

Table of Contents

1) What is Design Thinking?

2) Design Thinking process

3) Successful Design Thinking Case Studies

a) Airbnb

b) Apple

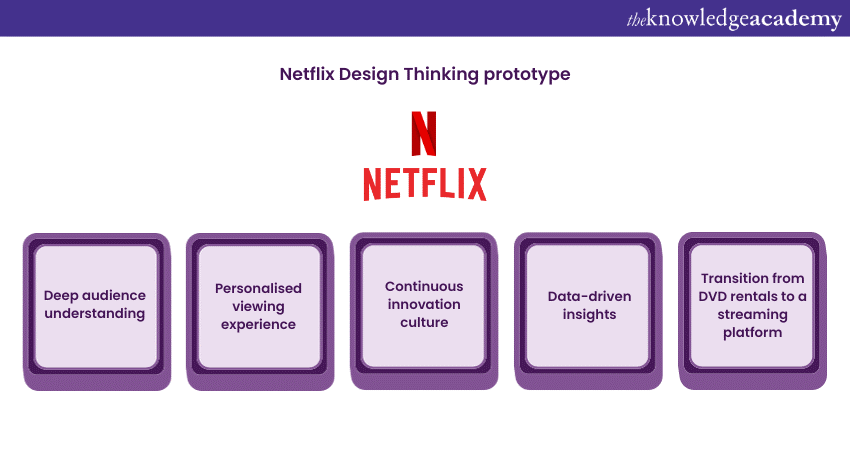

c) Netflix

d) UberEats

e) IBM

f) OralB’s electric toothbrush

g) IDEO

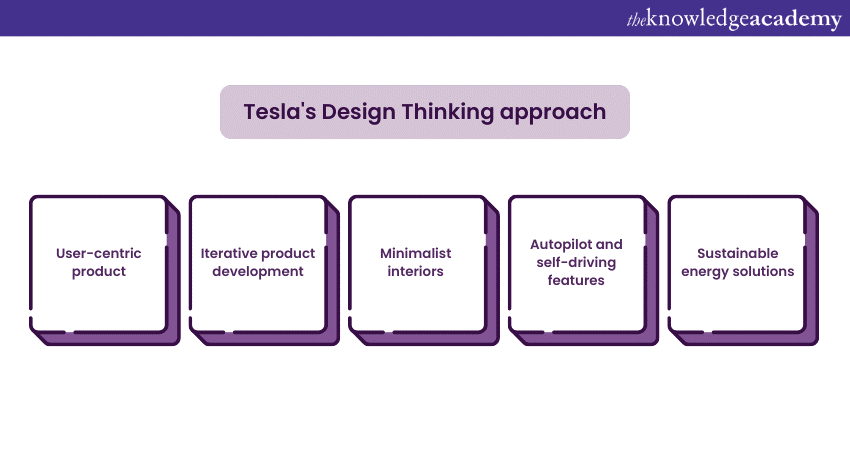

h) Tesla

i) GE Healthcare

j) Nike

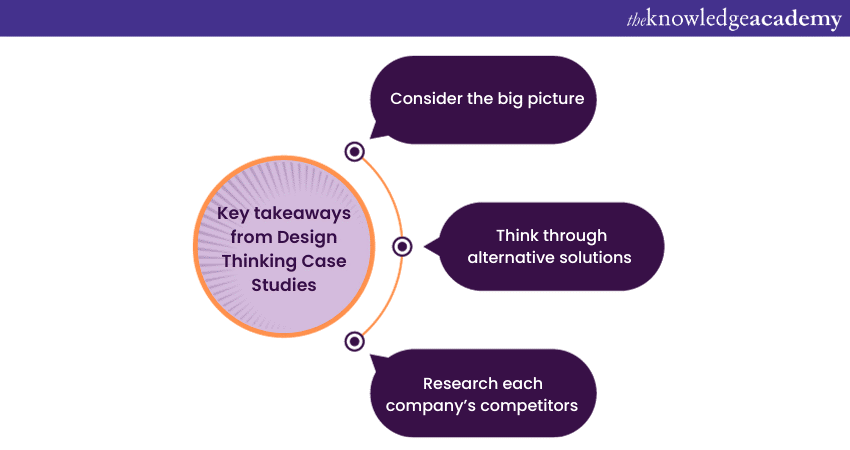

3) Lessons learned from Design Thinking Case Studies

4) Conclusion

What is Design Thinking ?

Before jumping on Design Thinking Case Study, let’s first understand what it is. Design Thinking is a methodology for problem-solving that prioritises the understanding and addressing of individuals' unique needs.

This human-centric approach is creative and iterative, aiming to find innovative solutions to complex challenges. At its core, Design Thinking fosters empathy, encourages collaboration, and embraces experimentation.

This process revolves around comprehending the world from the user's perspective, identifying problems through this lens, and then generating and refining solutions that cater to these specific needs. Design Thinking places great importance on creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, seeking to break away from conventional problem-solving methods.

It is not confined to the realm of design but can be applied to various domains, from business and technology to healthcare and education. By putting the user or customer at the centre of the problem-solving journey, Design Thinking helps create products, services, and experiences that are more effective, user-friendly, and aligned with the genuine needs of the people they serve.

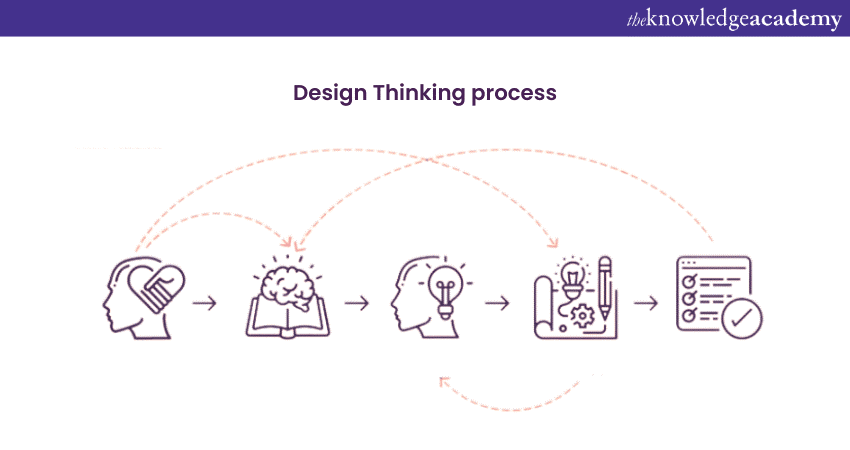

Design Thinking process

Design Thinking is a problem-solving and innovation framework that helps individuals and teams create user-centred solutions. This process consists of five key phases that are as follows:

To initiate the Design Thinking process, the first step is to practice empathy. In order to create products and services that are appealing, it is essential to comprehend the users and their requirements. What are their anticipations regarding the product you are designing? What issues and difficulties are they encountering within this particular context?

During the empathise phase, you spend time observing and engaging with real users. This might involve conducting interviews and seeing how they interact with an existing product. You should pay attention to facial expressions and body language. During the empathise phase in the Design Thinking Process , it's crucial to set aside assumptions and gain first-hand insights to design with real users in mind. That's the essence of Design Thinking.

During the second stage of the Design Thinking process, the goal is to identify the user’s problem. To accomplish this, collect all your observations from the empathise phase and begin to connect the dots.

Ask yourself: What consistent patterns or themes did you notice? What recurring user needs or challenges were identified? After synthesising your findings, you must create a problem statement, also known as a Point Of View (POV) statement, which outlines the issue or challenge you aim to address. By the end of the define stage, you will be able to craft a clear problem statement that will guide you throughout the design process, forming the basis of your ideas and potential solutions.

After completing the first two stages of the Design Thinking process, which involve defining the target users and identifying the problem statement, it is now time to move on to the third stage - ideation. This stage is all about brainstorming and coming up with various ideas and solutions to solve the problem statement. Through ideation, the team can explore different perspectives and possibilities and select the best ideas to move forward with.

During the ideation phase, it is important to create an environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their ideas without fear of judgment. This phase is all about generating a large quantity of ideas, regardless of feasibility. This is done by encouraging the team to think outside the box and explore new angles. To maximise creativity, ideation sessions are often held in unconventional locations.

It’s time to transform the ideas from stage three into physical or digital prototypes. A prototype is a miniature model of a product or feature, which can be as simple as a paper model or as complex as an interactive digital representation.

During the Prototyping Stage , the primary objective is to transform your ideas into a tangible product that can be tested by actual users. This is crucial in maintaining a user-centric approach, as it enables you to obtain feedback before proceeding to develop the entire product. By doing so, you can ensure that the final design adequately addresses the user's problem and delivers an enjoyable user experience.

During the Design Thinking process, the fifth step involves testing your prototypes by exposing them to real users and evaluating their performance. Throughout this testing phase, you can observe how your target or prospective users engage with your prototype. Additionally, you can gather valuable feedback from your users about their experiences throughout the process.