(9093) Conventions – Editorials, Speech

As level english (9093) conventions: editorials, speech.

Persuasive Texts: Editorials/Speech

Direct Approach: State opinion then argument

Indirect approach: Discuss / argue then state opinion

Editorials:

An editorial is an article that presents the newspaper’s opinion on an issue.

- Types of editorials:

- Explain or interpret: Editors often use these editorials to explain the way the newspaper covered a sensitive or controversial subject. School newspapers may explain new school rules or a particular student-body effort like a food drive.

- Criticize: These editorials constructively criticize actions, decisions or situations while providing solutions to the problem identified. Immediate purpose is to get readers to see the problem, not the solution.

- Persuade: Editorials of persuasion aim to immediately see the solution, not the problem. From the first paragraph, readers will be encouraged to take a specific, positive action. Political endorsements are good examples of editorials of persuasion.

- Praise: These editorials commend people and organizations for something done well. They are not as common as the other three.

- Characteristics of editorials:

- The opinions of the writer, delivered in a professional manner.

- An objective explanation of the issue, especially complex issues

- Primary topic/topics

- Intended audience

- Facts and statistics

- Arguments to support the thesis

- Ideology/point of view of the writer

- Develop logical and ethical arguments; avoid purely emotional rhetoric.

- Collect evidence, examples, and support for the view you are promoting.

- Alternative solutions to the problem or issue being criticized.

- Structure: Introduction, body, conclusion

- Engaging, emotive language

- Rhetorical devices: Seek to make an argument more compelling than it otherwise would’ve been.

- Always link back to the main idea. Clarity.

- Informal touch, it should be presented in a personal way.

- Support arguments: Facts/statistics, anecdotes, humor.

- Consider the audience: expectations, interest, and nature of the audience.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Writing Conventions: What They Are & How To Use Them

- February 22, 2024

Table of Contents Hide

What is a writing convention, 1. spelling and grammar, 2. punctuation, 3. capitalization, 4. paragraphing, 5. formatting, 6. citation and referencing , narrative writing conventions, persuasive writing conventions, letter writing conventions, instructional writing conventions, formal writing conventions, why do writing conventions matter, faqs on writing conventions, we also recommend.

Have you ever wondered why some writing just seems to flow effortlessly, while others seem confusing and disjointed? The secret lies in understanding and utilizing writing conventions effectively.

Writing conventions are the basic rules and norms that govern the way we write. They encompass everything from grammar and punctuation to formatting and structure. Mastering these conventions can make a world of difference in the clarity and impact of your writing.

Whether you are a student, a professional, or simply someone who wants to improve your writing skills, understanding writing conventions is essential. In this article, we will explore what writing conventions are, why they matter, and how you can use them to enhance your writing.

Writing and language conventions encompass the guidelines individuals need to adhere to when composing any type of written content. Whether crafting a narrative or delivering a political address, adherence to certain fundamentals, such as constructing complete sentences and correctly spelling words, is crucial for ensuring coherence and impact on the audience.

In addition to the broader writing conventions applicable to all forms of text, specific genres have distinct regulations and principles that govern them. For instance, the presence of stage directions, scenes, and dialogue without quotation marks signifies a play script.

Keep reading below to learn all about language conventions and techniques, including a language conventions list for you to use with your class.

READ ALSO: 50 Exclusive 6th Grade Writing Prompts that are Printable for Free

What Are The Basic Writing Conventions?

The basic writing conventions and rules that must be followed in all writing tasks, to help the reader understand what has been written are:

Accurate spelling and proper grammar form the foundation of effective communication. They play a crucial role in ensuring that your words are transparent, succinct, and easily comprehensible to your audience. Beyond just enhancing the readability of your writing, adherence to correct spelling and grammar reflects your commitment to precision and professionalism.

Typos and grammatical missteps have the potential to diminish the impact of your work, obscuring its intended meaning. Proficiency in spelling and grammar conventions empowers you to articulate your thoughts with clarity and precision, allowing you to express ideas with confidence and authority. Therefore, giving due attention to this essential writing convention is a key step toward honing your skills as a proficient wordsmith.

READ ALSO: Free Copywriting Courses For Freelancers In 2024

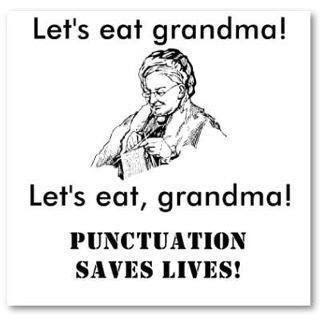

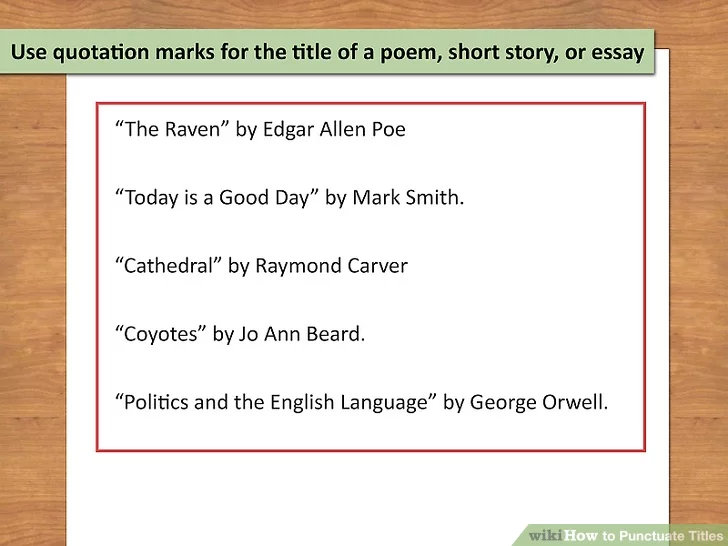

Punctuation is crucial in sentences for several reasons. Firstly, it helps to clarify the structure and organization of your writing, guiding readers on how to interpret the text. Punctuation marks, such as commas, periods, and colons, create pauses, indicate the end of a sentence, and separate different elements within a sentence.

Secondly, punctuation contributes to the overall tone and meaning of a sentence. For example, the placement of a comma can change the emphasis or nuance of a phrase. It helps to convey the intended emotions and nuances, preventing misunderstandings.

Punctuation marks like commas, periods, semicolons, and dashes should be used correctly since they may distinguish between poorly and flawlessly formed sentences. Every mark has a unique function and, when utilized skillfully, can elevate an ordinary statement to the level of an artistic creation. Take advantage of the power of punctuation and your writing will flow naturally, captivating your audience with your deft use of language.

Capitalization serves as a means of adding sophistication and lucidity to your writing, aiding in the differentiation of proper nouns, titles, and the commencement of sentences. This writing convention is indispensable as it imparts a sense of significance and emphasis to your words, guiding the reader’s focus toward the most pivotal aspects of your text.

Using capitalization at the onset of a sentence or for the initial letter of a proper noun establishes a formal and professional tone. Additionally, capitalizing the first word in a title or heading introduces a touch of creativity and style. Therefore, utilizing capitalization judiciously enhances your writing, allowing each letter to stand prominently, and capturing the reader’s attention with pride and clarity.

READ ALSO: 25 Inspiring Freelance Writing Quotes

Paragraphing enhances readability by breaking down a piece of text into manageable and organized chunks. This structure provides visual cues to readers, guiding them through the flow of ideas and making the content more digestible.

It helps to organize and group related information together. Each paragraph typically focuses on a specific point or idea, allowing readers to follow the logical progression of your thoughts. This organizational structure makes it easier for readers to understand the connections between different concepts.

Formatting in writing refers to the arrangement and presentation of text to enhance its readability, clarity, and overall visual appeal. Proper formatting is crucial for various reasons:

Well-formatted text is easier to read. The right use of fonts, font size, and line spacing contributes to a comfortable reading experience.

Furthermore, formatting aids in organizing ideas and information logically. Headings, subheadings, and bullet points create a visual hierarchy, making it clear how different pieces of information relate to each other. This improves the overall structure and coherence of the document.

By mastering formatting conventions, you can make your writing more attractive and engaging, ensuring that your message is received loud and clear. So, embrace the power of formatting and watch your writing come to life on the page!

Citing and referencing form the basis of academic writing, serving to acknowledge the sources you’ve consulted and utilized to bolster your ideas.

Accurate citation not only showcases your research acumen but also underscores your commitment to intellectual integrity and recognition of others’ contributions. Proper citation and referencing play a pivotal role in enhancing the credibility and authority of your writing, enabling readers to trace your sources and validate your assertions.

Whether you’re crafting an essay, research paper, or any academic document, proficiency in citation and referencing conventions is indispensable. Embrace this writing practice as an opportunity to exhibit your academic prowess, thereby making your writing more compelling and persuasive.

Check out 10 Tips on How to Increase Readability Score While Writing

Tone is the emotional quality or attitude that comes across in your writing. It is a subtle but powerful writing convention that can shape the way your message is received by your audience. Tone can be playful or serious, formal or informal, optimistic or pessimistic, and it sets the overall mood of your writing.

By mastering tone, you can effectively convey your message and connect with your readers on an emotional level. It is important to keep your audience in mind when choosing your tone, as different readers may respond better to different emotional appeals.

Style represents the distinctive and individualized touch that a writer imparts to their writing. It includes various components such as sentence construction, vocabulary selection, figurative expressions, and overall tone. Cultivating a unique style allows a writer to distinguish their work, making it memorable and impactful for their readers.

A strong writing style can also make your writing more engaging and memorable, drawing your readers in and keeping them hooked until the very end. However, style is not just about aesthetics – it is also about clarity, coherence, and effectiveness. By mastering the conventions of style, you can ensure that your writing is both beautiful and effective, leaving your readers with a lasting impression of your talent and skill.

SEE ALSO: Chinese vs Japanese Writing: A Side-by-Side Comparison

Writing Conventions For specific Genres

While the rules of spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and grammar are necessary for all texts, some genres have their own sets of rules and principles to follow. These features help the reader to identify what kind of text they are looking at.

Here are the different writing conventions for specific genres:

Like a book, a narrative text recounts a tale. Characters, dialogue, and an obvious narrative structure are some characteristics of a narrative work. To ensure that their narrative text has a distinct beginning, build-up, climax, resolution, and finish, children might prepare utilizing a tale mountain framework. You can be certain that you are reading a narrative if the material you are reading has a plot like this.

Persuasive writings can take the form of speeches, articles, posters, or other written works to persuade the reader to share the author’s viewpoint. Possessing a distinct point of view, which is usually expressed in the opening and conclusion, is an illustration of a persuasive writing convention. Rhetorical inquiries, emotive language, and facts and numbers will also be common elements.

READ ALSO: 21 Best Online Grant Writing Classes for Beginners

Numerous visual cues indicate the kind of text you are reading when you are reading a letter. A letter’s address, date, and salutation (such as “Dear Sir/Madam”) are all located in the upper right-hand corner. Additionally, it is probably going to be written in paragraphs and end with a salutation like “Yours Sincerely.”

Instructional writing covers text types such as recipes, instruction manuals, and how-to articles. This genre has many defining conventions, such as having a numbered list of instructions. This will be written in chronological order, and include imperative verb commands, such as “Mix the batter”. Instructions are unlikely to include any speech or descriptive features. This specific list of conventions helps the reader to know they are reading a set of instructions and to follow them effectively.

Writing conventions extend to distinct registers and genres. When creating a formal text, like a letter to your headteacher, particular guidelines govern your writing, signaling to the reader the formal nature of the communication. This involves refraining from using contractions, opting for expressions like “cannot” instead of the more casual “can’t.” A formal text is also unlikely to incorporate nicknames or slang terms. Adhering to these conventions assists in establishing the appropriate tone for your writing.

Writers utilize conventions to enrich and elucidate the meaning of their written expressions. These conventions empower writers to articulate precisely how a word or phrase should be comprehended by the reader, facilitating a clear grasp of the writer’s intended message. In instances where the writer is not physically present to orally convey the text, conventions serve the function of reading the content on behalf of the writer.

When composing any piece of writing, the writer typically envisions and hears the words internally before putting them to paper. While the writer has a distinct auditory perception, the reader lacks this personal insight. Conventions function as a roadmap, directing the reader through the text—signaling pauses, advancements, accelerations, decelerations, and other nuances. Essentially, conventions ensure that the written composition resonates with the intended tone and rhythm as perceived by the writer during the writing process.

Without conventions, writing would be a mess. If we didn’t put a space between each word just as you can see, everything would run together. Without the convention of correct spelling, writers could never be sure if readers would be able to read the words they had written. And even if we all spelled each word the same way, without the convention of punctuation, writers would still have trouble getting their message across.

Writing conventions are established rules and practices governing the mechanics, structure, and presentation of written language. They include elements like grammar, punctuation, spelling, and formatting.

Writing conventions are crucial for effective communication. They ensure clarity, consistency, and understanding in written content, making it easier for readers to comprehend the message.

Reading widely, studying grammar guides, and practicing writing are effective ways to enhance your grasp of writing conventions. Seeking feedback from peers or instructors can also be beneficial.

Regular proofreading, attention to detail, and awareness of common mistakes (e.g., grammatical errors, punctuation misuse) are key to minimizing language convention errors in writing.

Writers utilize conventions to enrich and elucidate the meaning of their written expressions. These conventions empower writers to articulate precisely how a word or phrase should be comprehended by the reader, facilitating a clear grasp of the writer’s intended message.

- 27 Best Books On Writing To Make You A Top Writer

- 107+ Creative Writing Prompts For Middle School Students

- 15 Different Types of Tones in Writing: Must-Know Guide for All Writers

- Chinese vs Japanese Writing: A Side-by-Side Comparison

Related Posts

Best blog post format for freelance writers: the worst thing you can do.

- May 9, 2024

42 Common Poetry Terms to Know as a Writer

- April 28, 2024

How Many Word Count Are in a Novel? Word Count by Genre

- April 24, 2024

19.7 Spotlight on … Delivery/Public Speaking

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Implement various technologies effectively to address an audience, matching the capacities of each to the rhetorical situation.

- Apply conventions of speech delivery, such as voice control, gestures, and posture.

- Identify and show awareness of cultural considerations.

Think of a speech you have seen or heard, either in person, on television, or online. Was the speech delivered well, or was it poorly executed? What aspects of the performance make you say that? Both good and poor delivery of a speech can affect the audience’s opinion of the speaker and the topic. Poor delivery may be so distracting that even the message of a well-organized script with strong information is lost to the audience.

Speaking Genres: Spoken Word, Pulpit, YouTube, Podcast, Social Media

The world today offers many new (and old) delivery methods for script writing. While the traditional presidential address or commencement speech on a stage in front of a crowd of people is unlikely to disappear, newer script delivery methods are now available, including many that involve technology. From YouTube , which allows anyone to upload videos, to podcasts, which provide a platform for anyone, celebrities and noncelebrities alike, to produce a radio-like program, it seems that people are finding new ways to use technology to enhance communication. Free resources such as YouTube Studio and the extension TubeBuddy can be a good starting place to learn to create these types of media.

Voice Control

Whether the method is old or new, delivering communication in the speaking genre relies not only on words but also on the way those words are delivered. Remember that voice and tone are important in establishing a bond with your audience, helping them feel connected to your message, creating engagement, and facilitating comprehension. Vocal delivery includes these aspects of speech:

- Rate of speech refers to how fast or slow you speak. You must speak slowly enough to be understood but not so slowly that you sound unnatural and bore your audience. In addition, you can vary your rate, speeding up or slowing down to increase tension, emphasize a point, or create a dramatic effect.

- Volume refers to how loudly or softly you speak. As with rate, you do not want to be too loud or too soft. Too soft, and your speech will be difficult or impossible to hear, even with amplification; too loud, and it will be distracting or even painful for the audience. Ideally, you should project your voice, speaking from the diaphragm, according to the size and location of the audience and the acoustics of the room. You can also use volume for effect; you might use a softer voice to describe a tender moment between mother and child or a louder voice to emphatically discuss an injustice.

- Pitch refers to how high or low a speaker’s voice is to listeners. A person’s vocal pitch is unique to that person, and unlike the control a speaker has over rate and volume, some physical limitations exist on the extent to which individuals can vary pitch. Although men generally have lower-pitched voices than women, speakers can vary their pitch for emphasis. For example, you probably raise your pitch naturally at the end of a question. Changing pitch can also communicate enthusiasm or indicate transition or closure.

- Articulation refers to how clearly a person produces sounds. Clarity of voice is important in speech; it determines how well your audience understands what you are saying. Poor articulation can hamper the effect of your script and even cause your audience to feel disconnected from both you and your message. In general, articulation during a presentation before an audience tends to be more pronounced and dramatic than everyday communication with individuals or small groups. When presenting a script, avoid slurring and mumbling. While these may be acceptable in informal communication, in presented speech they can obscure your message.

- Fluency refers to the flow of speech. Speaking with fluency is similar to reading with fluency. It’s not about how fast you can speak, but how fluid and meaningful your speech is. While inserting pauses for dramatic effect is perfectly acceptable, these are noticeably different from awkward pauses that result from forgetting a point, losing your place, or becoming distracted. Practicing your speech can greatly reduce fluency issues. A word on verbal fillers , those pesky words or sounds used to fill a gap or fluency glitch: utterances such as um , ah , and like detract from the fluency of your speech, distract the audience from your point, and can even reduce your credibility. Again, practice can help reduce their occurrence, and self-awareness can help you speak with more fluency.

Gestures and Expressions

Beyond vocal delivery, consider also physical delivery variables such as gestures and facial expressions . While not all speech affords audiences the ability to see the speaker, in-person, online, and other forms of speech do. Gestures and facial expressions can both add to and detract from effective script delivery, as they can help demonstrate emotion and enthusiasm for the topic. Both have the ability to emphasize points, enhance tone, and engage audiences.

Eye contact is another form of nonverbal, physical communication that builds community, communicates comfort, and establishes credibility. Eye contact also can help hold an audience’s attention during a speech. It is advisable to begin your speech by establishing eye contact with the audience. One idea is to memorize your opening and closing statements to allow you to maintain consistent eye contact during these important sections of the script and strengthen your connection with the audience.

Although natural engagement through gestures, facial expressions, and eye contact can help an audience relate to a presenter and even help establish community and trust, these actions also can distract audiences from the content of the script if not used purposefully. In general, as with most delivery elements, variation and a happy medium between “too much” and “too little” are key to an effective presentation. Some presenters naturally have more expressive faces, but all people can learn to control and use facial expressions and gestures consciously to become more effective speakers. Practicing your speech in front of a mirror will allow you to monitor, plan, and practice these aspects of physical delivery.

Posture and Movement

Other physical delivery considerations include posture and movement. Posture is the position of the body. If you have ever been pestered to “stand up straight,” you were being instructed on your posture. The most important consideration for posture during a speech is that you look relaxed and natural. You don’t want to be slumped over and leaning on the podium or lectern, but you also don’t want a stiff, unnatural posture that makes you look stilted or uncomfortable. In many speeches, the speaker’s posture is upright as they stand behind a podium or at a microphone, but this is not always the case. Less formal occasions and audiences may call for movement of the whole body. If this informality fits your speech, you will need to balance movement with the other delivery variables. This kind of balance can be challenging. You won’t want to wander aimlessly around the stage or pace back and forth on the same path. Nor will you want to shuffle your feet, rock, or shift your weight back and forth. Instead, as with every other aspect of delivery, you will want your movements to be purposeful, with the intention of connecting with or influencing your audience. Time your movements to occur at key points or transitions in the script.

Cultural Considerations

Don’t forget to reflect on cultural considerations that relate to your topic and/or audience. Cultural awareness is important in any aspect of writing, but it can have an immediate impact on a speech, as the audience will react to your words, gestures, vocal techniques, and topic in real time. Elements that speakers don’t always think about—including gestures, glances, and changes in tone and inflection—can vary in effectiveness and even politeness in many cultures. Consideration for cultural cues may include the following:

- Paralanguage : voiced cultural considerations, including tone, language, and even accent.

- Kinesics : body movements and gestures that may include facial expressions. Often part of a person’s subconscious, kinesics can be interpreted in various ways by members of different cultures. Body language can include posture, facial expressions (smiling or frowning), and even displays of affection.

- Proxemics : interpersonal space that regulates intimacy. Proxemics might indicate how close to an audience a speaker is located, whether the speaker moves around, and even how the speaker greets the audience.

- Chronemics : use of time. Chronemics refers to the duration of a script.

- Appearance : clothing and physical appearance. The presentation of appearance is a subtle form of communication that can indicate the speaker’s identity and can be specific to cultures.

Stage Directions

You can think proactively about ways to enhance the delivery of your script, including vocal techniques, body awareness, and cultural considerations. Within the draft of your script, create stage directions . An integral part of performances such as plays and films, stage directions can be as simple as writing in a pause for dramatic effect or as complicated as describing where and how to walk, what facial expressions to make, or how to react to audience feedback.

Look at this example from the beginning of the student sample. Stage directions are enclosed in parentheses and bolded.

student sample text Several years ago, I sat in the waiting area of a major airport, trying to ignore the constant yapping of a small dog cuddled on the lap of a fellow passenger. An airline rep approached the woman and asked the only two questions allowed by law. (high-pitched voice with a formal tone) “Is that a service animal? (pause) What service does it provide for you?” end student sample text

student sample text (bold, defiant, self-righteous tone) “Yes. It keeps me from having panic attacks,” the woman said defiantly, and the airline employee retreated. (move two steps to the left for emphasis) end student sample text

student sample text Shortly after that, another passenger arrived at the gate. (spoken with authority) She gripped the high, stiff handle on the harness of a Labrador retriever that wore a vest emblazoned with the words “The Seeing Eye.” (speed up speech and dynamic of voice for dramatic effect) Without warning, the smaller dog launched itself from its owner’s lap, snarling and snapping at the guide dog. (move two steps back to indicate transition) end student sample text

Now it’s your turn. Using the principle illustrated above, create stage directions for your script. Then, practice using them by presenting your script to a peer reviewer, such as a friend, family member, or classmate. Also consider recording yourself practicing your script. Listen to the recording to evaluate it for delivery, fluency, and vocal fillers. Remember that writing is recursive: you can make changes based on what works and what doesn’t after you implement your stage directions. You can even ask your audience for feedback to improve your delivery.

Podcast Publication

If possible, work with your instructor and classmates to put together a single podcast or a series of podcasts according to the subject areas of the presentations. The purpose of these podcasts should be to invite and encourage other students to get involved in important causes. Work with relevant student organizations on campus to produce and publicize the podcasts for maximum impact. There are many free resources for creating podcasts, including Apple’s GarageBand and Audacity .

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/19-7-spotlight-on-delivery-public-speaking

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, discourse conventions.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Discourse conventions are the norms guiding communication in specific communities. They span from written and spoken rules to visual cues, rooted in each community's shared experiences, values, and interests. Grasping these conventions helps you communicate effectively in varied settings.

What are Discourse Conventions?

The term “Discourse Convention” refers to the distinctive ways members of a discourse community speak, write, and visually communicate with one another.

Discourse conventions encompass the shared expectations among writers, readers, speakers, and listeners within a specific discourse community regarding how communication, both verbal and nonverbal, should be structured and presented. These conventions include rules, established templates, organizational patterns, styles, methodologies, and even nonverbal mannerisms such as gestures, facial expressions, and visual representations. Discourse conventions may pertain to a range of linguistic and rhetorical elements, including diction , grammar , mechanics , perspective , point of view , sentence structure , tone , voice , persona . They are deeply rooted in the community’s traditions of creating and interpreting meaning, as encapsulated in its archive and canon .

For instance, the manner in which a scientist presents data using visual aids in a seminar, or how an attorney maintains a formal demeanor in court, reflects the discourse conventions of their respective communities. Through these conventions, members of a discourse community are able to effectively engage in meaningful exchanges, nurturing a common understanding and facilitating the progression of shared knowledge and objectives.

Discourse conventions reflect the values, actions, and research methods of a discourse community. Take, for instance, a discourse community centered around positivist principles in scientific inquiry . Within such a community, discourse conventions would likely prioritize empirical evidence , objective language, and precise, quantifiable data. The meticulous structuring of arguments , rigorous peer-review processes , and the adherence to established scientific methodologies reflect the community’s collective belief in an orderly, comprehensible universe governed by discernible laws.

The discourse conventions, in this case, embody the community’s valuing of empirical rigor, objective analysis, and collaborative scrutiny. Through these conventions, members of the discourse community engage in a structured dialogue aimed at uncovering the objective truths about the natural world, thus advancing the collective understanding within their field and contributing to the broader scientific discourse.

Related Concepts: Audience Awareness ; Rhetorical Analysis

Why Do Discourse Conventions Matter?

Discourse conventions play a crucial role in ensuring effective communication between writers and readers : they provide a shared framework for the presentation and organization of ideas, which aids clarity communication .

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

🧭 The Guide SUNY Geneseo’s Writing Guide

Conventions of writing.

The human capacity for language has its roots in nature. The combination of physical and cognitive resources necessary to the production and comprehension of symbolic utterance is a result—and perhaps the defining acquisition—of our unique evolutionary history. The biological basis of our ability to speak and write has led a small number of scholars—such as the cognitive scientist Steven Pinker—to argue that humans are born not only with an innate capacity for language but with innate linguistic knowledge—that they are, as it were, prewired with the basic principles of a universal grammar. It seems more plausible to suppose, however, that although the human capacity for language arises from nature, particular languages, and their particular uses, are largely the product of culture.

In other words, language is a social practice. It is, at a deep if not the deepest level, a structure of social conventions, and in that sense thoroughly conventional.

This page considers the conventional aspects of language under the following headings:

Convention and the varieties of discourse

Convention and social change: is english in decline, the politics of convention: language and political correctness, racism in language, sexism in language.

The most obviously conventional aspects of language—treated at length on a separate page of The Guide —are its rules of grammar and usage . But the conventions of language extend beyond grammar and usage to encompass such matters as style and organization. The result is a variety of conventional discourses . Academic discourse has some basic conventions that set it apart from, say, technical, legal, or journalistic discourse; within academic discourse, conventions vary from discipline to discipline . While most academic discourse is, broadly speaking, formal, writers in the natural sciences or social sciences may organize essays differently from writers in the humanities. Documentation styles for citing sources also differ according to discipline.

Like the cultures that produce them, languages vary not only from one another but within themselves, for their constitutive conventions differ over time and place. Over the last ten centuries, English has undergone such dramatic changes in vocabulary, syntax, and morphology that its earliest recorded form, Old English, is for most modern readers a foreign language. Even the last few hundred years have witnessed noticeable shifts in the conventions of English spelling, punctuation, and usage, some of them significant enough to make a page of Dickens present a serious challenge for the twenty-first-century reader. And anyone who has learned English in the United States need only hop a plane to England, or for that matter travel the Eastern seaboard, for a reminder of the many dialectical differences to be found within modern English itself.

Social practices inevitably generate debates about their proper execution. Where you find conventions, in other words, you can depend on finding arguments over “correctness.” In the case of language, the debate takes on further complication from disagreement, not to mention a good deal of misunderstanding, concerning the role of conventions themselves in linguistic practice. Writers interested in learning more about this debate might profitably begin with linguist Geoffrey Nunberg’s “ The Decline of Grammar ,” an essay that explains the difference between “descriptive” and “prescriptive” grammar and discusses the politics and pitfalls of the latter. Novelist Mark Halpern’s response to Nunberg, “ A War That Never Ends ,” claims that human beings are naturally drawn to construct “standards” to correct their linguistic practice.

Politics is largely a function of speech. The rough inverse of this truth—that speech is more than occasionally a function of politics—should not, therefore, surprise us.

The most obviously political conventions of language have to do with names. After all, names are all about identity, and social wrangling over identities—of groups, of places, of events—can be very charged politically. “What’s in a name?” asked Shakespeare’s Juliet. The answer: a lot. If it were otherwise, the names for proponents and opponents of legal abortion would be uncontroversial, taxes would never have to masquerade as “revenue enhancements,” and all Southerners would have long since abandoned calling the events of 1861-65, “The War Between the States.”

For historically marginalized social subgroups, the struggle for political prominence often involves a push to eradicate or at least stigmatize conventionally accepted, sometimes patently demeaning names. As a result of such struggles, once-common names for some racial, ethnic, and religious groups have become conventionally regarded as offensive. Occasionally a marginalized group has adopted the opposite strategy, openly embracing a derogatory or otherwise suspect label as a way to express defiance and drain the label of its conventional power to insult or diminish. “Black,” “gay,” and “queer” are examples.

Though the two strategies are diametrically opposed, the groups who employ them share a single impulse: to wrest control of their own social identities as one step toward winning the ultimate prizes of recognition, respect, equality, and power.

In the 1980s, the term political correctness emerged to designate, among other things, a kind of censorship that the term’s users believed had resulted from recent struggles over the politics of social naming. Why, it was asked, can we not simply call people and things by their real names? Why must we engage in euphemism merely to flatter the aggrieved?

It was easy enough for critics of “pc” to find examples of ludicrous euphemism intended to promote self-esteem for underdogs, such as “vertically challenged” as a proposed substitute for “short.” But such simple examples belie the genuine complexity of the problem. In fact, nothing has a “real” name, since, as we’ve seen, all names are human in origin and therefore products of convention. In language, “real” names are those whose conventional acceptance is so widespread that we’ve ceased to think about their artificiality. A challenge to one of these “real” names represents a retort to such unconsciousness, and sometimes a retort to the underlying social reality that makes such unconsciousness possible. The “short” example seems absurd on its face because few people seriously accept the notion that, as a group, persons of lesser physical stature labor under a significant burden of social prejudice and discrimination reflected and perpetuated by the conventional name for them. The case is very different, however, with groups defined by ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, or some other common characteristic that has indeed subjected them to significant prejudice or discrimination.

In any of these more vexed cases, no name will likely settle into “real” status while debate on the group’s social acceptance and influence remains open. As long as the perception of inequality or stigma persists, the conventional name of the moment will likely come, in time, to be associated with, to reflect, perhaps even to help facilitate, the inequality’s persistance.

The problem of establishing a “real” name grows still more complicated when the reality that the name picks out is an unstable social construction itself. Here the seemingly unending uncertainty and dissatisfaction with all conventions reflects not only persisting inequality or stigma but the indeterminacy of what our names attempt to identify. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) still bears in its title a once-conventional racial label. The organization has outlasted the label, which eventually became offensive because of its evident blindness to the reality that “white” people possess pigmentation. (Student readers of The Guide may not realize that when the authors were of coloring-book age, Crayola manufactured a light-hued crayon hubristically lableled “flesh.”) Formerly “colored” people eventually became, by convention, “black,” though they are not truly black in color and indeed are not, in their genetic multiplicity, any one color, just as “white” people are not of one uniform hue. The currently conventional “African-American” (an addition to rather than a replacement for “black,” which most people still conventionally regard as acceptable) is a historically and geographically accurate description only of some people to whom the name now applies, and is useless either in discussing issues of race and ethnicity in a global (rather than strictly American) context or in capturing the multiracial, multicultural personal histories of many who live in America today. Recognition of this last point has given rise to the circle-completing advent of the name “people of color,” which covers a wider population than “colored,” “black,” or “African-American,” but which for that very reason can only augment, rather than replace, those other terms.

The artificiality of all such labels might seem a reason to dispense with them completely. However, they clearly fill a variety of important social needs—from demographic analysis to personal identification with particular historical, geographic, cultural, and other categories—and the prospect of their disappearance is neither likely nor clearly desirable. The inevitability of social naming must finally lead us to ask, in response to complaints about the inconveniences of “political correctness”: If we must name a group, should we not use the name that, in the group’s own view, most promotes recognition, respect, equality, and power for its members?

Besides taking pains to use names that maximize recognition and respect (see the section above) how can you avoid racism and other forms of bigotry in your writing? For starters, of course, you should scrupulously avoid all stereotypes and undocumented generalizations about social groups of any kind. You should also consult the dictionary on any words that you suspect of carrying offensive denotations or connotations.

However, the dictionary will only take you so far. There are no substitutes, in the end, for an awareness of history and a fine sensitivity to context and implication. The point is nicely illustrated by a minor aspect of the debate over the recent war in Iraq. Before and during the war, political pundits divided over whether the war would be a “cakewalk.” Discussion mainly focused on weapons, intelligence, strategy, and tactics, but columnist Patricia Williams saw a problem with the word “cakewalk” itself. In the April 28, 2003 issue of The Nation, she tartly observed that

one should never enter a fight announcing that it will be a “cakewalk.” A cakewalk was a dance contest popularized during the days of black minstrelsy, for which the prize was, as implied, a fluffy confection. Debussy, as our well-educated senior [military] advisers ought to know, wrote a funny little piece of musical condescension to this effect, Golliwog’s Cakewalk. (A golliwog, for the uninformed, is a charmingly old-fashioned word for “n[***].”) Such are the amusements of colonialism. But in the so-called post colonial era, such references do tend to rankle.

Type “cakewalk” into the Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary search box at the top of this page, and you won’t find any indication that the word is offensive. Williams objects not to the word in isolation, however, but to the word and its attendant imagery and history in the context of an aggressive military enterprise that in her view summons shadows of America’s slave-tainted imperial past.

In glossing the word “golliwog,” Williams herself uses, in quotation marks, what has become one of the most taboo words in English. Was she wrong to use it? Was The Nation wrong to print it in full (which they did), rather than abbreviate it in some way, such as “n–r” or “n***” (as we have done here, substituting for the original)?

Once again context matters. Williams and The Nation seem to have decided that the clearly condemnatory context, together with the quotation marks, sufficed to remove any message of hatred from the word, and perhaps even that printing the word in full would make the condemnation all the more forceful. Perhaps, too, Nation editors would have reached a different decision if the writer had been white. (Common consensus affords derogated groups special license to use the derogatory labels historically bestowed on them.)

As a student writer, you must exercise care and thought in making complex judgments about the fully contextualized meaning and impact of your words. It is a safe assumption, however, that you should never use any any plainly hate-charged language, even where context might seem to neutralize it, unless explicity permitted to do so by your instructor.

In addition, you should follow these practical guidelines:

- Modernize or contextualize outdated terms that you cite from your reading. For example, in The Fire Next Time (1963), novelist James Baldwin writes of the misplaced confidence that the systematic murder suffered by Jews in the Holocaust “could not happen to the Negroes in America.” In an essay on Baldwin, you should either quote Baldwin’s exact words or, if you choose to paraphrase, substitute the term “African-Americans” for “Negroes.”

- Keep your terminology consistent and parallel. Write “white people and black people” rather than “white people and blacks.” If you capitalize “White,” capitalize “Black.” (Some writers prefer to capitalize these words when referring to people and groups rather than skin color. Others prefer to use lower case. The important thing, again, is to be consistent.)

- Capitalize words that refer to or are derived from nationality. E.g., “The African-American poet wrote about her experiences traveling with the Vietnamese novelist.” Also capitalize words that describe a religion or a member of a religious faith. E.g., “Many Muslims in Rochester helped the Kosovar refugees settle in western New York.” “The largest Christian sect in Rochester is Roman Catholic.” “Faculty should avoid scheduling exams during Jewish holidays.”

For more on racism in language, see:

- Philip Herbst, The Color of Words: an Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ethnic Bias in the United States (Yarmouth, Me., USA : Intercultural Press, 1997). In Milne Library this book is catalogued: ref E184.A1 H466 1997.

- Rosalie Maggio, Talking About People: A Guide to Fair and Accurate Language (Phoenix, Ariz. : Oryx Press, 1997). In Milne Library this book is catalogued: ref P301 .M33 1997.

A father and son, on their way to baseball game, are involved in a horrible car wreck. The son is rushed to the hospital and wheeled into the emergency room. The doctor, seeing the patient, exclaims, “I can’t operate—that’s my son!” Question: How can this be?

Answer: the doctor is the boy’s mother.

Many people who believe themselves innocent of sexism will be stumped—if not completely, at least momentarily—by this riddle. Try it on your friends and see what you find.

The riddle works because sexism, like other forms of bigotry (see the sections above) runs deeper in society than we realize, affecting our very understanding of the words used in common discourse. Of all the historical power relationships embedded in the English language, that between men and women probably affects more aspects of speech and writing—from diction to grammar and usage —than any other.

Attempts to promote gender-neutral and nonsexist usage in everyday speech have met with remarkably fierce resistance from some quarters. In a television debate some years ago, a prominent conservative pundit derided the term “chair” as a gender-neutral substitute for “chairman” on the grounds that it was ludicrous to address a human being as an object of furniture. Why this is any more ludicrous than addressing a human being as an isolated body part—as in the unexceptional and uncontroversial term “head” for a person in a position of primary responsibility—the pundit didn’t say. Nor did he pause to reflect, apparently, that in English we regularly refer to people by using associated objects, such as when we speak of “the crown” (=the monarch) or “the White House” (=the President). Literary scholars and linguists call this pefectly ordinary manner of reference-by-substitute “metonymy.” In formal parliamentary parlance, to postpone consideration of a motion is to “lay it on the table.” At most meetings, the participants who wish to avail themselves of this procedure use a kind of metonymic verb and simply “table” the motion. One would think chairs pefectly at home amidst such linguistic furniture.

Many people still have difficulty with the honorific term “Ms.” They seem to think it a substitute for “Miss” merely, to be supplanted, upon marriage, by “Mrs.” They fail to understand that when English makes a public distinction concerning marital status for one sex only (men are simply labeled “Mr.” except to designate professional status, as in “Dr.,” “Prof,” or “Rev.”), English is sexist. For the distinction carries the plain message that a woman’s marital status is a public matter, and of primary importance, while a man’s is private and subsidiary to his choice of career.

The sexism in terms such as “mailman,” “fireman,” and “policeman”—not when used to refer to particular male individuals, but to refer to anonymous individuals or to the occupations themselves—also comes from the message bound up with the words: that the normative holder of the occupation is male.

Similarly, the sexism in the word “man” as a generic name for the human race comes from its implication that the normative human being is male, women being some kind of interesting, perhaps unaccountable variant—or, as linguists say of nonstandard verbal constructions, the “marked case.” Men are business as usual. Women are men with an asterisk (the symbol that linguists in fact use to indicate the “marked case,” and that Major League Baseball for many years placed beside Roger Maris’s home run record, to signal that it was somehow not the real thing.)

Attempts to gender-neutralize language, we commonly hear, confuse language and reality, as though we could wish away the actual power relations in society merely by using the correct words. This argument misses the point that words often do influence our perception of social reality—particularly in the childhood years—and that even when reform of language brings no major reform of society, it can be an important gesture of recognition and respect (see the sections above.)

For most job titles, gender-neutral words are neither as difficult to find nor as cumbersome as critics claim: mail carrier (or postal worker), firefighter (which is euphoniously alliterative), and police officer are not difficult to use, and the power of human invention being what it is, finding similar substitutes for other man-words should not be a herculean task. (If they can send a man to the moon … )

It’s a striking linguistic fact that anyone can invent a noun, adjective, or verb and, with adequate publicity, hurry it into ordinary people’s speech. Neologisms like “smog” and “blog” assimilate into English with ease, as do new verbs based on nouns or adjectives, such as “access,” “impact,” and “familiarize.” Pronouns are another matter altogether. It may in fact be easier to send a man—or woman—to the moon than to add a gender-neutral third-person singular pronoun (other than “it”) to English.

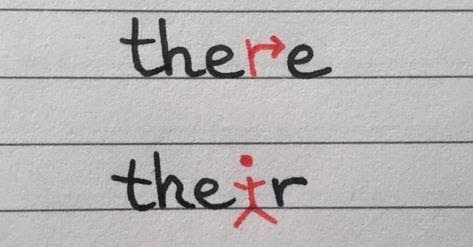

In spoken English, most people—even if they care nothing about gender equality—solve this problem by treating “they” and “their” as gender-neutral singular pronouns, as in “A writer can’t help where they came from” or “Everyone takes their hat off for the national anthem.” Moreover, historical precedent favors those writers who employ this solution even in formal written discourse, as Henry Churchyard illustrates in his extensive web treatment of singular “their,” which includes numerous examples from that impeccable English sylist, Jane Austen.

There may be problems with singular “their,” but illogic isn’t one of them. It is no more illogical to write, “A person isn’t responsible for their genetic make-up” than to write, “A person isn’t responsible for his genetic make-up” when roughly half of personhood is female. Churchyard’s site references Steven Pinker, author of The Language Instinct, on why the first type of sentence is actually more logical grammatically.

- Services Growth Roadmap SEO Only Content Only SEO + Content Video

- Free Training

Writing Conventions: What They Are & Why They’re Important

In this article

Have you ever thought about what language would be like if there weren’t any rules or conventions?

This article will remind us all about the importance of writing conventions and how to make the most of them.

Disclosure: These reviews are reader-supported. We might earn a small commission if you purchase something through our site. Learn more

Grammarly Best All-Around

- Only supports English

- Expensive without our link

Make Writing Fun Again

Set and forget your writing conventions by running Grammarly in the background. Save 20% with our exclusive link .

Grammarly Premium Walkthrough Video

What are Writing Conventions?

The phrase “writing conventions” may sound unfamiliar to some, but everyone knows what they are when they see them.

The four pillars include:

- punctuation

- capitalization

The writers in our very own content marketing agency use it on a daily basis.

Pro tip: Test — don’t guess

There are a plethora of affordable tools at your disposal, like Grammarly or Editpad , that can instantly help you spot and fix these common writing conventions.

So test, don’t guess!

These four conventions allow us to understand any text that we’re reading without having to decipher it first. Without them, you wouldn’t know where a sentence, or a thought, begins or ends.

They make a language clear and easy to follow. There are other, more complex conventions as well, but these are often only required for more advanced college writing skills. (Or by running them through a grammar checker like ProWritingAid .)

Why Do Writing Conventions Matter?

Did you know that nearly 40% of people say digital tools make people more likely to use poor grammar and spelling skills?

This is especially true in the context of online dating, where the written word is the starting point of any introduction and hence the first impression. So, if for no other reason, proper grammar and punctuation will increase your chances of finding a partner.

It sounds subtle. But just like the experts from our MasterClass review can attest, it’s the details that make all the difference!

Writing conventions such as grammar, punctuation, and spelling are also a big deal in academic writing.

Examples of Writing Conventions

Now we’re going to talk about the most important writing conventions and why each of them matters in particular. We’re also going to provide examples to help you understand better.

Spelling has taken some serious hits in the era of the internet. While it’s a cause for concern to some, others don’t pay too much attention to it.

You’ve probably read a misspelled tweet or text message without flinching. That’s because, according to research, as long as the first and last letter of the word is at the correct place, the reader will be able to understand the text.

Punctuation

Imagine if you’re reading: “I don’t know what I’m reading how about you do you think she knows.” That’s is not an easy string of text to follow. How many sentences are there? Where do they begin, and where do they end?

You would have to apply extra effort to understand what the person who wrote it was trying to say. Punctuation gives you pause and provides rhythm to reading and writing. Correct punctuation also dictates the intonation.

Grammar provides the basic structure for any language. It teaches us how to use the words we know and how to form sentences. Undoubtedly, grammar is a complicated area that often takes a while to grasp fully.

Almost everyone makes grammatical mistakes, and those that say they don’t aren’t being exactly forthcoming.

For the most part, grammatical mistakes tend to be repetitive , and it’s much easier to choose the wrong word when they’re similar semantically or phonetically:

Writing Conventions Use Cases

Let’s explore situations where knowing to use writing conventions correctly can be of great use. Remember, the writing process is not only about what you write, but how you write it.

Capitalization use

Of course, you should know that you need to capitalize people’s names and rivers and mountains. But capitalization is often confusing when you’re supposed to write a title or indicate something unique in the text. Topic sentences can be a bit confusing here too.

However, that doesn’t mean that you should randomly distribute capital letters. And one of the most important rules to follow here is to always capitalize the first letter of a sentence, a basic even on a writing paper .

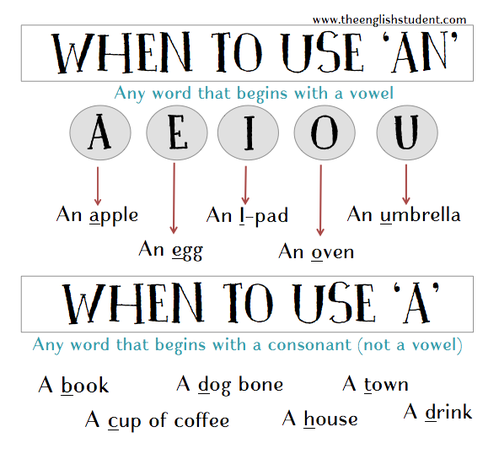

Grammar use

There are many uses of grammar, and it would probably take an eBook to highlight them all. But one of the more frequent areas of grammar is the definite and indefinite article distribution.

For people with a degree in English language , this can often be a sore spot. But for people who are learning English as their second language, that can be a downright nightmare.

However, for making your sentences sound smoother and more accurate, learning where to place articles is vital.

Punctuation use

Punctuation matters because it helps us understand the exact meaning of a sentence. And as we know, a misplaced or omitted punctuation can drastically alter the meaning.

Commas allow you to pause and quickly absorb the information. A dash, for example, indicated a significant break in the thought of a sentence. One thing to keep note of is that the comma is often used improperly. If you expect to be able to follow proper writing conventions, knowing how to use a comma is about the first thing you should learn.

And quotation marks are also relevant because they signify direct speech. Adding the right punctuation mark in the right place can make all of the difference.

Writing Conventions FAQs

What are common punctuation mistakes.

Everyone has their weak points in punctuation. Some people tend to overuse the comma, and others keep skipping them.

Another issue that has come up in recent years is the overuse of the exclamation mark. This practice can sometimes overwhelm the reader. As a writer, these are all mistakes that you need to avoid at all costs.

When to Check Your Grammar and Spelling?

When you’re writing, it’s easy to get overly focused on not making writing mistakes, especially in grammar and spelling.

Most good writing apps, like Scrivener, will also help you spot these as you write, too.

But mistakes will happen, and it’s probably best to wait until you’re done to read through and edit. You’re less likely to break your focus in that way.

How do You Improve Your Writing Conventions Knowledge?

Without a doubt, the most effective way to improve all the most important writing conventions is to read as much as you can.

As you read, that’s when you can pay closer attention to the spelling, grammar, and capitalization without any stress of making a mistake. Something else to familiarize yourself with is how to use pronouns and proper nouns!

What are Some Strategies to Help You Remember?

There are too many things about writing conventions, and you can’t merely memorize them all. The best course of action is to focus on whatever you’re having a difficult time with and practice relentlessly.

Over time, you will be less likely to repeat the same mistakes. You can also try taking online quizzes and tests.

The Beauty of the (Correctly) Written Word

Some people take to grammar and spelling naturally and don’t have too many issues with either. Others see capitalization and punctuation as something that’s just boring and irrelevant.

But everyone will agree with one thing. That there’s a significant difference in reading a book or an article where the author followed all writing conventions and those where the author didn’t.

You won’t need to stop every few sentences to understand them or wonder when the writer’s current thought ends, and the next begins. Following conventions inevitably lead to better communication between a writer and a reader.

As a student, you may be able to get away with not following proper writing conventions, but in writing, the further you get in your field, the better your spelling, grammar, and punctuation needs to be. Check out our Grammarly review today!

Get long-term ROI.

Opinion Columns

Infographics/image, broadsheets, internet article, paper 1: texts and conventions, structural elements.

- Salutation - shows the relationship between speaker and audience.

- Establishes purpose

- Introduces stance of the speaker

- Relates to the audience

- Purpose is emphasised through different techniques.

- Repetition of the purpose using rhetorical devices.

- Proving the benefits of the purpose using appeals.

- Call to action

- Concludes message and ends with finality.

- Linguistic elements

- Aristotelian appeal: Logos, ethos, and pathos

- Use of facts and figures

- Anecdotes or personal examples

- Figurative language (simile, metaphor, personification, imagery)

- Hyperphora, anaphora, rhetorical structures

- parallel structures, tricolon

- Asyndeton, polysyndeton

- Personalised language, usage of second person pronoun

- Masthead or title

- Strapline under headline, more detail

- Short paragraph summarising entire article

- Generates interest in the audience

- name of the writer

- Image and caption

- One or two lines that grabs the attention of the audience.

- Pulled out of the matter

- relevant and important text.

- States the purpose and topic.

- States the relevance of the topic by relating to the audience.

- Body matter (largest part)

- Author gives a comment

- Talks about an investigation

- Predicts a consequence

- Call to action.

- Shows the credibility of the journalist.

- Call to action, eg. comment on twitter, etc.

- Inherits all conventions from article.

- Opinion is stated very strongly in first paragraph.

- Body paragraphs have arguments in favour and rebuttic arguments.

- Newspapers and magazines often have columnists who write for them

- Generally speaking, newspapers or magazines want there to be a cult of personality surrounding these columnists to generate good sales and brand loyalty

- Columnists may be very outspoken in their opinions

- Nevertheless, their opinions are in tune with the readership of a particular magazine or newspaper

- Furthermore, their opinions are newsworthy, meaning that they both comment on the hot topics of the day and their opinions are worthy of publication.

Structural Elements

- Introduces the issue and states the writer’s stance.

- Strongly puts forth call to action.

- At times, the reader of a magazine or newspaper gets to hear the editor’s voice directly

- This usually takes the form of a brief explanation or justification on hoe they have decided to cover a topic in their newspaper or magazine

- Remember editors are the gatekeepers at a publishing house who decide what goes in to the final publication

- In an editorial they may comment on their journalists’ fieldwork, their columnists’ reputation, or their newspapers’ status in society

- This is written by a renowned person, somebody who has authority in a field.

- Opposes the stance of the editorial.

- Written prose piece typically published by a newspaper or a magazine written by a named writer/public personality usually not affiliated by the publication’s editorial board

- Op Eds are different from editorials (which are usually unsigned and written by the editorial board members) or Letters to the editor (which are submitted by the readers to the journal/newspaper)

- the general of an army may write an op-ed about the status of war

- a famous rockstar may write an op-ed in Rolling Stone magazine

- the president of a country may write a letter to a political opponent, which he or she wishes to be published as an op-ed

Features common with editorials

- Short sentences and simple sentence construction

- Active voice rather than passive voice in verbs

- Short words from common vocabulary

- Almost no use of number or math

- Attention grabbing title

- Important point first, not last

- Use of people’s first and last names for ‘human interest’

- Affiliation language (business, university, titles, location) for persuasion

- Who, what, when, where, why, how

- Contains all the conventions of a cartoon or a graphic novel.

- Stacking and flow between images and photographs.

- Number of images

- Spacing and use of negative space

Graphical/linguistic elements

- Camera angles

- Colour scheme - light and shade

- Simple, fluent language

- Use of formatted text

- Facial/bodily gestures and expressions

- Begins and ends with a hook , an attention grabber.

- Retains the curiosity and interest.

- Feedback mechanisms from the audience are present.

Linguistic Elements

- Audience focused

- Follows online conventions

- Figurative, but to the point

- Sets out the purpose of the letter

- Introduces context and content for analysis

- Contains statement of intent

- Contains purpose and contextual clues

- Call to action (formal open letter)

- Reiterating purpose + intent

- Pleasantries

- The tone, which establishes the relationship of the writer to the primary audience

- Relatability of the text

- Purpose of the writer

- Contextual references

- Minced words, euphemisms

- Vernacular/local language

- Sarcastic elements

- Uses emotive, personal language

- The hidden implications of the text

- The real meaning of the text below the language

- Use of puns

- Use of alliteration

- Exaggeration for effect

- Colloquial language

- Informal names used

- Short, snappy sentences

- Heightened language (over the top)

- Brand names

- Sexual innuendos

- A focus upon appearance / colours

- Frequent use of elision e.g. won’t, don’t.

- More formal

- Metaphors rather than puns (puns - sometimes used, although more subtle)

- subtle rhetoric

- More complex sentences (look for sentences separated by lots of commas, semi-colons etc.)

- Descriptions of people tends to relate to personality or position in society ;

- Politician’s comments often included, with a commentary by the journalist

- Focusses more on being authenticity and sophistication

- Name of the journal – masthead

- Contextual information under the headline, it establishes relevance of lead story – standfirst

- Name of the writer, when it was published, place – by-line

- Selective excerpts magnified - pull quote

- Quotations/sources

- Other reading suggestions - off-lead

Characteristics

- Voice – this refers to many aspects of language including word choice, verb tense, tone and imagery

- Newsworthy – is the column relevant to its time? What makes it newsworthy?

- Call to action – columnist usually call on the reader to become involved or care about an issue

- Humour – this is really an aspect of voice; humour usually helps readers see a topic through an original and fun perspective

- Hard facts – this aspect of newsworthiness gives an opinion column credibility

- Logos – appealing to logic will help persuade your readers

Social Media

Trump goes on ego-boosting Memorial Day posting spree after Libertarian speech shambles

F ormer President Donald Trump went on an early morning Memorial Day posting spree in an effort to spin an appearance at the Libertarian National Convention that many considered a disaster.

Trump took to the stage Saturday and was mercilessly booed as he asked for the third party’s nomination. After that humiliation, he got only six write-in votes.

On Monday, he went on an ego-boosting spree, posting a series of articles describing his appearance as a huge success.

Want more breaking political news? Click for the latest headlines at Raw Story.

In seven separate posts, all placed on Truth Social within minutes of each other just after midnight, he shared praise from his followers.

“President Trump gets massive cheers before Libertarian National Convention after promising to commute Ross Ulbricht’s prison sentence,” posted ex-Trump adviser Steve Bannon’s MAGA War room, and shared by the former president.

“Trump is on fire tonight,” he shared from another supporter, named Johnny Maga.

ALSO READ: 'Oh, come on!' Tommy Tuberville dismisses Trump connection to 'unified Reich' video

“Tremendous performance by Trump before a tough crowd,” wrote a user called David Marcus, again shared.

And the extremist Trump-loving activist Laura Loomer wrote, “The entire National Libertarian Convention erupted in cheers!”

The posts followed a statement Sunday night in which he tried to spin the event , claiming he never wanted the nomination anyway — despite asking for it directly.

"The reason I didn’t file paperwork for the Libertarian Nomination, which I would have absolutely gotten if I wanted it (as everyone could tell by the enthusiasm of the Crowd last night!), was the fact that, as the Republican Nominee, I am not allowed to have the Nomination of another Party," Trump wrote on Truth Social.

"Regardless, I believe I will get a Majority of the Libertarian Votes."

Recommended Links:

・ Libertarian leader stuns MSNBC reporter by describing how much she hates Trump

・ Trump ends speech to 'mostly boos' after going 'off prompter' and 'making fun of' his host

・ Trump allies melt down as Libertarians 'eject Trump members' from front row seats at event

・ Trump gets humiliating 6 votes in Libertarian nomination contest after boo-filled speech

・ Trump takes stage to 'thunderous boos' at Libertarian convention event

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Writing non-fiction - AQA Writing a speech Non-fiction texts are those that deal with facts, opinions and the real world. Many non-fiction texts follow specific conventions of language and structure.

Structure Conventions of a Speech What Should be in an introduction? - Introducing the topic - Get the audience's attention 1) Introduction 2) Middle 3) Conclusion What Should your middle include - Main Points - To Persuade the audience What should a ... What are AI writing tools and how can they help with making presentations? May 22, 2024 ...

Editorials: An editorial is an article that presents the newspaper's opinion on an issue. Types of editorials: Explain or interpret: Editors often use these editorials to explain the way the newspaper covered a sensitive or controversial subject. School newspapers may explain new school rules or a particular student-body effort like a food drive.

Instructions are unlikely to include any speech or descriptive features. This specific list of conventions helps the reader to know they are reading a set of instructions and to follow them effectively. Formal writing conventions. Writing conventions extend to distinct registers and genres. When creating a formal text, like a letter to your ...

This publication about speech writing and types of speeches is the second of a three-part series about developing effective public speaking skills. This series also covers an introduction to public speaking and public speaking tools. University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Extension outreach is a partnership between ...

Apply conventions of speech delivery, such as voice control, gestures, and posture. ... Remember that writing is recursive: you can make changes based on what works and what doesn't after you implement your stage directions. You can even ask your audience for feedback to improve your delivery. Podcast Publication. If possible, ...

See why leading organizations rely on MasterClass for learning & development. Learning how to write a speech requires a keen awareness of how to tailor your rhetoric to a given issue and specific audience. Check out our essential speech-writing guidelines to learn how to craft an effective message that resonates with your audience.

The term "Discourse Convention" refers to the distinctive ways members of a discourse community speak, write, and visually communicate with one another. Discourse conventions encompass the shared expectations among writers, readers, speakers, and listeners within a specific discourse community regarding how communication, both verbal and ...

Persuasive writing conventions. Persuasive texts aim to convince the reader to agree with the author's point of viewand might be presented in a format such as a speech, article, or poster. One example of a persuasive writing convention would be having a clear point of view, which is likely to be presented in the introduction and the conclusion.