- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Consumer Research: Examples, Process and Scope

What is Consumer Research?

Consumer research is a part of market research in which inclination, motivation and purchase behavior of the targeted customers are identified. Consumer research helps businesses or organizations understand customer psychology and create detailed purchasing behavior profiles.

It uses research techniques to provide systematic information about what customers need. Using this information brands can make changes in their products and services, making them more customer-centric thereby increasing customer satisfaction. This will in turn help to boost business.

LEARN ABOUT: Market research vs marketing research

An organization that has an in-depth understanding about the customer decision-making process, is most likely to design a product, put a certain price tag to it, establish distribution centers and promote a product based on consumer research insights such that it produces increased consumer interest and purchases.

For example, A consumer electronics company wants to understand, thought process of a consumer when purchasing an electronic device, which can help a company to launch new products, manage the supply of the stock, etc. Carrying out a Consumer electronics survey can be useful to understand the market demand, understand the flaws in their product and also find out research problems in the various processes that influence the purchase of their goods. A consumer electronics survey can be helpful to gather information about the shopping experiences of consumers when purchasing electronics. which can enable a company to make well-informed and wise decisions regarding their products and services.

LEARN ABOUT: Test Market Demand

Consumer Research Objectives

When a brand is developing a new product, consumer research is conducted to understand what consumers want or need in a product, what attributes are missing and what are they looking for? An efficient survey software really makes it easy for organizations to conduct efficient research.

Consumer research is conducted to improve brand equity. A brand needs to know what consumers think when buying a product or service offered by a brand. Every good business idea needs efficient consumer research for it to be successful. Consumer insights are essential to determine brand positioning among consumers.

Consumer research is conducted to boost sales. The objective of consumer research is to look into various territories of consumer psychology and understand their buying pattern, what kind of packaging they like and other similar attributes that help brands to sell their products and services better.

LEARN ABOUT: Brand health

Consumer Research Model

According to a study conducted, till a decade ago, researchers thought differently about the consumer psychology, where little or no emphasis was put on emotions, mood or the situation that could influence a customer’s buying decision.

Many believed marketing was applied economics. Consumers always took decisions based on statistics and math and evaluated goods and services rationally and then selected items from those brands that gave them the highest customer satisfaction at the lowest cost.

However, this is no longer the situation. Consumers are very well aware of brands and their competitors. A loyal customer is the one who would not only return to repeatedly purchase from a brand but also, recommend his/her family and friends to buy from the same brand even if the prices are slightly higher but provides an exceptional customer service for products purchased or services offered.

Here is where the Net Promoter Score (NPS) helps brands identify brand loyalty and customer satisfaction with their consumers. Net Promoter Score consumer survey uses a single question that is sent to customers to identify their brand loyalty and level of customer satisfaction. Response to this question is measured on a scale between 0-10 and based on this consumers can be identified as:

Detractors: Who have given a score between 0-6.

Passives: Who have given a score between 7-8.

Promoters: Who have given a score between 9-10.

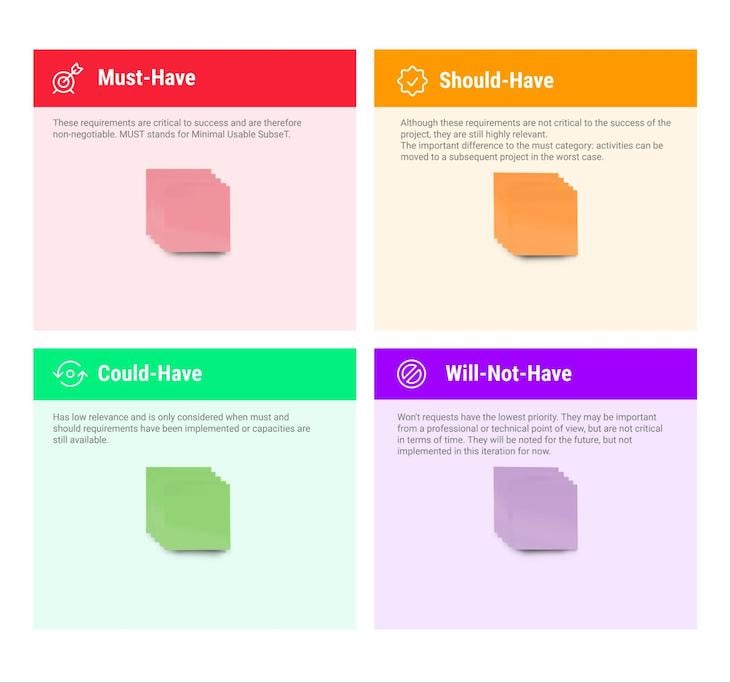

Consumer market research is based on two types of research method:

1. Qualitative Consumer Research

Qualitative research is descriptive in nature, It’s a method that uses open-ended questions , to gain meaningful insights from respondents and heavily relies on the following market research methods:

Focus Groups: Focus groups as the name suggests is a small group of highly validated subject experts who come together to analyze a product or service. Focus group comprises of 6-10 respondents. A moderator is assigned to the focus group, who helps facilitate discussions among the members to draw meaningful insights

One-to-one Interview: This is a more conversational method, where the researcher asks open-ended questions to collect data from the respondents. This method heavily depends on the expertise of the researcher. How much the researcher is able to probe with relevant questions to get maximum insights. This is a time-consuming method and can take more than one attempt to gain the desired insights.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

Content/ Text Analysis: Text analysis is a qualitative research method where researchers analyze social life by decoding words and images from the documents available. Researchers analyze the context in which the images are used and draw conclusions from them. Social media is an example of text analysis. In the last decade or so, inferences are drawn based on consumer behavior on social media.

Learn More: How to conduct Qualitative Research

2.Quantitative Consumer Research

In the age of technology and information, meaningful data is more precious than platinum. Billion dollar companies have risen and fallen on how well they have been able to collect and analyze data, to draw validated insights.

Quantitative research is all about numbers and statistics. An evolved consumer who purchases regularly can vouch for how customer-centric businesses have become today. It’s all about customer satisfaction , to gain loyal customers. With just one questions companies are able to collect data, that has the power to make or break a company. Net Promoter Score question , “On a scale from 0-10 how likely are you to recommend our brand to your family or friends?”

How organic word-of-mouth is influencing consumer behavior and how they need to spend less on advertising and invest their time and resources to make sure they provide exceptional customer service.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Targeting

Online surveys , questionnaires , and polls are the preferred data collection tools. Data that is obtained from consumers is then statistically, mathematically and numerically evaluated to understand consumer preference.

Learn more: How to carry out Quantitative Research

Consumer Research Process

The process of consumer research started as an extension of the process of market research . As the findings of market research is used to improve the decision-making capacity of an organization or business, similar is with consumer research.

LEARN ABOUT: Market research industry

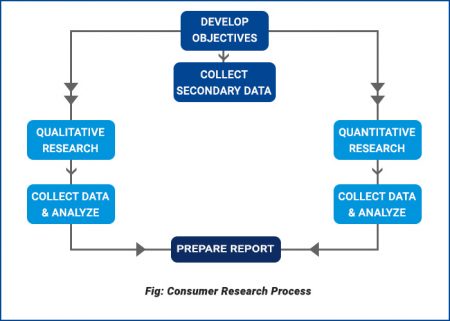

The consumer research process can be broken down into the following steps:

- Develop research objectives: The first step to the consumer research process is to clearly define the research objective, the purpose of research, why is the research being conducted, to understand what? A clear statement of purpose can help emphasize the purpose.

- Collect Secondary data: Collect secondary data first, it helps in understanding if research has been conducted earlier and if there are any pieces of evidence related to the subject matter that can be used by an organization to make informed decisions regarding consumers.

- Primary Research: In primary research organizations or businesses collect their own data or employ a third party to collect data on their behalf. This research makes use of various data collection methods ( qualitative and quantitative ) that helps researchers collect data first hand.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

- Collect and analyze data: Data is collected and analyzed and inference is drawn to understand consumer behavior and purchase pattern.

- Prepare report: Finally, a report is prepared for all the findings by analyzing data collected so that organizations are able to make informed decisions and think of all probabilities related to consumer behavior. By putting the study into practice, organizations can become customer-centric and manufacture products or render services that will help them achieve excellent customer satisfaction.

LEARN ABOUT: market research trends

After Consumer Research Process

Once you have been able to successfully carry out the consumer research process , investigate and break paradigms. What consumers need should be a part of market research design and should be carried out regularly. Consumer research provides more in-depth information about the needs, wants, expectations and behavior analytics of clients.

By identifying this information successfully, strategies that are used to attract consumers can be made better and businesses can make a profit by knowing what consumers want exactly. It is also important to understand and know thoroughly the buying behavior of consumers to know their attitude towards brands and products.

The identification of consumer needs, as well as their preferences, allows a business to adapt to new business and develop a detailed marketing plan that will surely work. The following pointers can help. Completing this process will help you:

- Attract more customers

- Set the best price for your products

- Create the right marketing message

- Increase the quantity that satisfies the demand of its clients

- Increase the frequency of visits to their clients

- Increase your sales

- Reduce costs

- Refine your approach to the customer service process .

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

Consumer Research Methods

Consumers are the reason for a business to run and flourish. Gathering enough information about consumers is never going to hurt any business, in fact, it will only add up to the information a business would need to associate with its consumers and manufacture products that will help their business refine and grow.

Following are consumer research methods that ensure you are in tandem with the consumers and understand their needs:

The studies of customer satisfaction

One can determine the degree of satisfaction of consumers in relation to the quality of products through:

- Informal methods such as conversations with staff about products and services according to the dashboards.

- Past and present questionnaires/ surveys that consumers might have filled that identify their needs.

T he investigation of the consumer decision process

It is very interesting to know the consumer’s needs, what motivates them to buy, and how is the decision-making process carried out, though:

- Deploying relevant surveys and receiving responses from a target intended audience .

Proof of concept

Businesses can test how well accepted their marketing ideas are by:

- The use of surveys to find out if current or potential consumer see your products as a rational and useful benefit.

- Conducting personal interviews or focus group sessions with clients to understand how they respond to marketing ideas.

Knowing your market position

You can find out how your current and potential consumers see your products, and how they compare it with your competitors by:

- Sales figures talk louder than any other aspect, once you get to know the comparison in the sales figures it is easy to understand your market position within the market segment.

- Attitudes of consumers while making a purchase also helps in understanding the market hold.

Branding tests and user experience

You can determine how your customers feel with their brands and product names by:

- The use of focus groups and surveys designed to assess emotional responses to your products and brands.

- The participation of researchers to study the performance of their brand in the market through existing and available brand measurement research.

Price changes

You can investigate how your customers accept or not the price changes by using formulas that measure the revenue – multiplying the number of items you sold, by the price of each item. These tests allow you to calculate if your total income increases or decreases after making the price changes by:

- Calculation of changes in the quantities of products demanded by their customers, together with changes in the price of the product.

- Measure the impact of the price on the demand of the product according to the needs of the client.

Social media monitoring

Another way to measure feedback and your customer service is by controlling your commitment to social media and feedback. Social networks (especially Facebook) are becoming a common element of the commercialization of many businesses and are increasingly used by their customers to provide information on customer needs, service experiences, share and file customer complaints . It can also be used to run surveys and test concepts. If handled well, it can be one of the most powerful research tools of the client management . I also recommend reading: How to conduct market research through social networks.

Customer Research Questions

Asking the right question is the most important part of conducting research. Moreover, if it’s consumer research, questions should be asked in a manner to gather maximum insights from consumers. Here are some consumer research questions for your next research:

- Who in your household takes purchasing decisions?

- Where do you go looking for ______________ (product)?

- How long does it take you to make a buying decision?

- How far are you willing to travel to buy ___________(product)?

- What features do you look for when you purchase ____________ (product)?

- What motivates you to buy_____________ (product)?

See more consumer research survey questions:

Customer satisfaction surveys

Voice of customer surveys

Product surveys

Service evaluation surveys

Mortgage Survey Questions

Importance of Consumer Research

Launching a product or offering new services can be quite an exciting time for a brand. However, there are a lot of aspects that need to be taken into consideration while a band has something new to offer to consumers.

LEARN ABOUT: User Experience Research

Here is where consumer research plays a pivotal role. The importance of consumer research cannot be emphasized more. Following points summarizes the importance of consumer research:

- To understand market readiness: However good a product or service may be, consumers have to be ready to accept it. Creating a product requires investments which in return expect ROI from product or service purchases. However, if a market is mature enough to accept this utility, it has a low chance of succeeding by tapping into market potential . Therefore, before launching a product or service, organizations need to conduct consumer research, to understand if people are ready to spend on the utility it provides.

- Identify target consumers: By conducting consumer research, brands and organizations can understand their target market based on geographic segmentation and know who exactly is interested in buying their products. According to the data or feedback received from the consumer, research brands can even customize their marketing and branding approach to better appeal to the specific consumer segment.

LEARN ABOUT: Marketing Insight

- Product/Service updates through feedback: Conducting consumer research, provides valuable feedback from consumers about the attributes and features of products and services. This feedback enables organizations to understand consumer perception and provide a more suitable solution based on actual market needs which helps them tweak their offering to perfection.

Explore more: 300 + FREE survey templates to use for your research

MORE LIKE THIS

Techathon by QuestionPro: An Amazing Showcase of Tech Brilliance

Jul 3, 2024

Stakeholder Interviews: A Guide to Effective Engagement

Jul 2, 2024

Zero Correlation: Definition, Examples + How to Determine It

Jul 1, 2024

When You Have Something Important to Say, You want to Shout it From the Rooftops

Jun 28, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Communities

Technologies

Success Stories

Get in touch

What Is Consumer Research: Methods, Types, Scope & Examples

Jan 19, 2024

Consumer Research Overview:

Consumer research is an essential aspect of any successful business strategy. Understanding your target audience, their preferences, and behaviours is crucial for making informed decisions, developing effective marketing campaigns, and staying ahead in a competitive marketplace. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the world of consumer research, covering key methods, types, and scope, and providing real-world examples of its practical applications.

Introduction to Consumer Research

Consumer research, also known as market research, is the systematic process of gathering and analyzing data about consumers' attitudes, preferences, and behaviours. It is a vital component of strategic planning for businesses and organizations across various industries. The primary goal of consumer research is to gain insights into consumer needs and desires, enabling businesses to make informed decisions and create products and services that meet those needs effectively.

Key Methods in Consumer Research

To conduct effective consumer research, various methods and techniques are employed. These methods can be broadly categorized into two main approaches: quantitative and qualitative research.

Quantitative Research in Consumer Studies

Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and statistical analysis. It often involves surveys, questionnaires, and structured interviews with a large sample of participants. This method provides numerical insights into consumer behaviors , preferences, and trends. Data collected through quantitative research can be analyzed to identify patterns, correlations, and statistical significance. This approach is particularly useful when a business needs to measure consumer satisfaction, evaluate the effectiveness of marketing campaigns, or conduct large-scale market studies.

Qualitative Approaches in Consumer Research

Qualitative research, on the other hand, emphasizes understanding the underlying motivations and emotions behind consumer behaviors. It involves methods like focus groups, in-depth interviews, and observational studies. Qualitative research allows researchers to delve deeper into consumers' thoughts, feelings, and experiences. It helps businesses gain a more nuanced understanding of their target audience, enabling them to develop products and marketing strategies that resonate on a deeper level.

Exploring Types of Consumer Research

Consumer research is a multifaceted field with various types, each serving specific purposes:

Demographic Analysis in Consumer Research

Demographic research involves analyzing data related to consumers' age, gender, income, education, and other demographic factors. This type of research helps businesses identify and target specific consumer groups based on their characteristics and preferences.

Psychographic Research Methods

Psychographic research focuses on consumers' lifestyles, values, interests, and personality traits. By understanding the psychological factors that influence consumer behavior, businesses can tailor their marketing strategies to align with consumers' beliefs and aspirations.

Consumer Insight Generation

Consumer insight research aims to uncover unique and valuable insights about consumer behaviors and preferences. It often involves innovative data collection techniques and advanced analytics to discover hidden trends and opportunities.

Brand Perception Research

Brand perception research assesses how consumers perceive a brand and its products or services. It helps businesses understand the strengths and weaknesses of their brand image and make necessary improvements.

Product Testing in Consumer Studies

Product testing involves gathering consumer feedback on new products or prototypes. This research type helps businesses refine their products based on real-world consumer input, ensuring they meet market demands.

Comparative Consumer Analysis

Comparative research involves evaluating a business's performance relative to its competitors. It helps identify areas where a business can gain a competitive edge and better serve its target audience.

Cross-Cultural Consumer Research

Cross-cultural research examines consumer behaviours and preferences across different cultures and regions. It helps businesses adapt their marketing strategies to diverse consumer demographics.

The Broad Scope of Consumer Research

Consumer research is not limited to the products and services themselves; it encompasses various aspects of consumer behaviour and market dynamics. The scope of consumer research includes:

Technology in Consumer Studies

As technology continues to advance, consumer research methods have also evolved. Businesses now have access to big data analytics, AI-driven insights, and social media sentiment analysis, allowing them to gain a deeper understanding of consumer behaviour in the digital age.

Future Trends in Consumer Research

Consumer research is a dynamic field, constantly evolving to keep up with changing consumer preferences and market dynamics. Staying updated with emerging trends in consumer research is essential for businesses to remain competitive.

Data-Driven Consumer Insights

The advent of big data has revolutionized consumer research. Businesses can now harness vast amounts of data to gain valuable insights into consumer behavior, helping them make data-driven decisions and improve their strategies.

Consumer Decision-Making Models

Understanding how consumers make decisions is crucial for businesses. Consumer research explores the decision-making process, including factors like perception, motivation, and cognitive biases, to help businesses influence consumer choices effectively.

Real-world Examples of Consumer Research

Let's look at some practical applications of consumer research in real-world scenarios:

Case Studies in Consumer Research

A leading smartphone manufacturer conducts consumer research to understand what features and specifications consumers prioritize in their smartphones. Based on the findings, the company designs and markets its products accordingly, staying ahead of competitors.

Consumer Satisfaction Measurement

A restaurant chain regularly collects feedback from its customers through surveys and online reviews. By analyzing this data, they identify areas for improvement, make necessary changes to their menu and service, and maintain high levels of customer satisfaction.

Trend Analysis in Consumer Studies

A fashion retailer closely monitors consumer trends and preferences in clothing. They use this information to adapt their inventory, marketing campaigns, and store layouts to align with current fashion trends and consumer preferences.

Retail Environment Studies

A retail giant conducts in-store consumer research to optimize its store layout, product placement, and signage. By creating a more pleasant and efficient shopping experience, they aim to increase customer satisfaction and sales.

Consumer Feedback and Reviews

An e-commerce platform analyzes customer feedback and reviews to identify product issues, improve product descriptions, and enhance customer trust. This research helps them provide a better shopping experience.

Online Consumer Behavior

An online marketplace tracks user behaviour on its website to improve user experience, optimize search algorithms, and personalize product recommendations, ultimately increasing sales and customer satisfaction.

Social Media Impact on Consumer Research

A cosmetics brand monitors social media channels to gauge customer sentiment and feedback. They use this data to adjust marketing strategies and product offerings in real-time, staying responsive to consumer preferences.

Global Consumer Trends

A multinational corporation conducts cross-cultural consumer research to adapt its products and marketing strategies to different regions and cultures, ensuring they resonate with local consumers.

Consumer Preferences and Trends

A food and beverage company studies consumer preferences for healthier options. This research informs their product development and marketing efforts to align with the growing trend of health-conscious consumers.

Lifestyle and Consumer Choices

A fitness equipment manufacturer conducts consumer research to understand how consumers' lifestyles and preferences influence their purchasing decisions. This helps them develop products tailored to specific consumer segments.

Psychological Aspects of Consumer Behavior

A marketing agency delves into the psychological factors that influence consumer decisions. They use this knowledge to create compelling advertisements and marketing campaigns that resonate with consumers on a deeper level.

Cultural Influences in Consumer Research

An international travel agency studies how cultural differences impact travel preferences. They tailor their vacation packages and marketing materials to appeal to diverse cultural groups.

Ethical Considerations in Consumer Research

While consumer research provides valuable insights, it is essential to conduct it ethically and responsibly. Respecting consumers' privacy and ensuring the security of their data should be paramount. Businesses should obtain informed consent, anonymize data when necessary, and adhere to applicable regulations, such as GDPR or CCPA, to protect consumers' rights.

The Evolution of Consumer Research Methods

Consumer research methods have evolved significantly over the years. From traditional face-to-face interviews and paper surveys to online surveys, big data analytics, and AI-driven insights, technology has played a pivotal role in enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of consumer research. Businesses must stay current with the latest research tools and techniques to remain competitive in today's fast-paced market.

The Impact of Technology on Consumer Research

Technology has revolutionized consumer research in several ways:

Faster Data Collection

Online surveys and digital data collection methods allow businesses to gather consumer insights more quickly, enabling faster decision-making.

Enhanced Data Analysis

Advanced analytics tools enable businesses to process and analyze vast amounts of data, uncovering hidden trends and patterns that were previously difficult to identify.

Personalization in Consumer Engagement

Technology allows businesses to personalize their interactions with consumers, offering tailored recommendations and experiences based on individual preferences and behaviors.

Data Privacy in Consumer Studies

As technology has evolved, concerns about data privacy have grown. Ethical consumer research practices involve protecting consumers' personal information and respecting their privacy rights.

Integrating AI in Consumer Insights

Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms can analyze consumer data more efficiently, providing businesses with valuable insights and predictive analytics.

Practical Applications: How Businesses Use Consumer Research

Consumer research is not just an academic exercise; it has practical applications that directly impact a business's success. Here are some ways businesses use consumer research to their advantage:

Product Development

Consumer research helps businesses identify gaps in the market and develop products that align with consumer needs and preferences.

Marketing Strategies

By understanding consumer behaviors and preferences, businesses can tailor their marketing strategies to effectively reach and engage their target audience.

Customer Experience Enhancement

Consumer research helps businesses improve customer service, streamline processes, and create a positive and memorable customer experience.

Competitive Advantage

By staying updated with consumer trends and preferences, businesses can gain a competitive edge in the market and position themselves as industry leaders.

Risk Mitigation

Consumer research can help identify potential risks and challenges in the market, allowing businesses to proactively address them.

Innovative businesses use consumer research to identify emerging trends and opportunities, leading to the development of groundbreaking products and services.

In conclusion, consumer research is an indispensable tool for businesses seeking to understand their target audience, make informed decisions, and stay competitive in the ever-evolving marketplace. By employing various research methods, understanding different types of consumer research, and respecting ethical considerations, businesses can harness the power of consumer insights to drive growth, innovation, and success. As technology continues to shape the field of consumer research, businesses that embrace data-driven decision-making and prioritize consumer satisfaction will thrive in the dynamic business landscape of the future.

At Market Xcel, we offer a suite of research services to our clients, leveraging our expertise in consumer research to provide valuable insights and drive success in today's competitive business environment.

Don’t miss out.

Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss any updates, news and blogs., promise, we won't spam., table of contents.

Industry Intelligence

Certifications

Subscribe to us

Market Xcel Data Matrix

5741 Cleveland street, Suite 120, VA beach, VA 23462

Market Xcel Data Matrix Pvt. Ltd.

190 Middle Road, # 14-10 Fortune Centre, Singapore - 188979

17, Okhla Industrial Estate Phase 3 Rd, Okhla Phase III, Okhla Industrial Estate, New Delhi,

Delhi 110020

Tel: +91 11 42343500

Market Xcel Data Matrix © 2023 (v1.1.3)

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

- Marketplace

- Future Proof

Exploring consumer research: strategies for informed marketing

Director, Growth & Strategy

If you want to understand what makes your target audience tick, consumer research is a must. But how do you go about gathering insights about consumer behaviour, preferences, and values? In this article, we discuss just that, exploring strategies and best practices for effectively collecting and interpreting consumer data in a digital landscape.

What is consumer research?

Consumer research, also known as market research, is the process of aggregating information about consumers and their behaviours. The insights gleaned from this process allow you to better understand consumer preferences, needs, and expectations. As a result, your brand can make data-driven decisions about everything from product development to marketing strategies.

The exact means of conducting consumer research vary from company to company. However, this research is typically conducted through methods like surveys, focus groups, and data analytics. These tools garner various types of information, including:

Demographic data

Demographic data encompasses information such as age, gender, income, education level, marital status, and location. Demographics help your brand identify its target audience and develop products and services that appeal to that respective group of individuals.

Psychographic data

Psychographic data refers to any information about consumers’ attitudes, values, interests, and lifestyle. This helps companies understand the emotional and psychological aspects that affect purchasing decisions.

Attitudinal data

Similarly, market researchers may attempt to collect information about consumers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards specific products, brands, or industries. A cleaning product brand may, for instance, measure consumers’ loyalty to a competing brand.

Behavioural data

Behavioural data refers to consumer actions, such as purchase history, product usage, and shopping habits. The more you know about how consumers have acted in the past, the more accurately you can predict future behaviour.

Purchase intent data

Purchase intent data allows you to understand consumers’ purchase intentions and the factors affecting whether or not they buy a product or service. This information is key to product development as well as marketing.

Product and service feedback

Collecting feedback from consumers about their experiences with products or services—from complaints to overall satisfaction—can drive product improvements. This type of information can also enhance customer service.

Consumer research methods

To yield meaningful insights, your brand must adopt a systematic approach to consumer research. It should begin with a clear definition of research objectives, including what specific questions need to be answered and what outcomes are desired. From there, you should determine the most appropriate research tool.

A consumer research survey is a structured data collection method that gathers information from a sample of respondents. This information may be related to the respondents’ behaviours, opinions, attitudes, or preferences. Surveys may be conducted online, via telephone, or in-person.

- Efficiency: A well-designed survey can collect a large volume of data quickly, making this tool a cost-effective choice.

- Standardisation: Surveys offer consistency in question structure and response options, reducing potential bias and ensuring that all respondents receive the same set of questions.

- Quantifiable data: Surveys generate quantitative data, allowing market researchers to garner insights through statistical analysis. Even open-ended survey questions can be quantified using text analysis tools.

Collect online survey data more efficiently and effectively with Kantar

When you partner with Kantar to conduct consumer research, you benefit from our agile data collection approach. This includes longitudinal studies with bespoke methodologies, quick-turn tests, and other ad hoc projects. We also provide clients with easy-to-use dashboards for in-house analytics and insights.

Focus groups

A focus group is a qualitative research method in which a small group of selected participants engage in a structured, facilitated discussion about a specific product, service, brand, or other related topic. The goal of a focus group is to gather deeper, more nuanced insights regarding consumer attitudes and perceptions.

- Richer data: Focus groups allow for a deeper understanding of participants’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences. This helps market researchers understand the “why” behind consumer behaviours.

- Real-time clarification: When survey takers are completing an online questionnaire, they may provide misleading information if they don’t quite understand a question. But in a real-life scenario, moderators can provide clarification.

- Group dynamics: Interaction among participants can generate additional insights that might not emerge in one-on-one interviews or surveys. This group setting also allows market researchers to obtain more information faster compared to interviewing individuals one by one.

Syndicated research

Syndicated research refers to data that is aggregated by market research companies, consulting firms, or other organisations. This data is then sold to multiple clients or subscribers who are interested in understanding the dynamics of a specific industry.

- Cost-effectiveness: Purchasing syndicated research can be cheaper than generating first-party data. This makes consumer research available to companies with limited marketing resources.

- Efficiency: Conducting extensive consumer research studies can take time. But with syndicated research, market researchers can access the information they need when they need it.

- Benchmarking: Brands can use syndicated research to benchmark their performance against industry standards and competitors.

Purchase behaviour

At Kantar, we believe the best way to understand consumer behaviour is to witness it firsthand. That is why we aggregate high-quality consumer data through tracking the buying behaviour of 750,000 consenting consumers. This allows our clients to understand the values and beliefs of real shoppers.

- Deeper insights: By analysing consumer purchase behaviour, companies can identify trends, preferences, and patterns and distil meaningful insights that inform everything from marketing campaigns to product development.

- Competitive advantage: Understanding consumer behaviour can provide a competitive advantage, allowing brands to stay ahead of market trends and pivot in the face of shifting consumer preferences.

- Market segmentation: Tracking purchase behaviour helps companies segment consumers based on preferences, frequency of purchases, and spending habits. In return, brands can tailor messaging in ways that appeal to each respective market segment.

Ensuring your consumer research data is high quality

In today’s competitive marketplace, consumer research data collected from real people who are who they say they are is essential. Without it, your data may not match reality and you risk making misinformed business decisions. In return, you may waste resources and even risk damaging brand reputation.

At Kantar, we understand the value of data quality . We meticulously follow best practices and set the industry standard for fraud-secured, quality data collection. When you partner with us for your custom research, or use our syndicated research, you can rest easy knowing that our survey respondent panels are:

Fraud-secured

Unfortunately, survey fraud can taint entire datasets. The good news is that Kantar has developed an advanced anti-fraud solution called Qubed . Using cutting-edge machine learning and artificial intelligence, this state-of-the-art software detects fraudulent activities where humans or other standard measures cannot.

Diverse and representative

Through the Kantar Profiles Audience Network , we connect you with more than 170 million global panellists and 2 billion data points around habits, characteristics, and behaviours. This ensures that the resulting data is diverse and representative of your target audience.

Highly-engaged respondents

Survey fatigue can have grave consequences, from incomplete responses to survey dropout. Fortunately, our proprietary survey programming tools are best-in-class. They're designed and tested to deliver the engaged answers from respondents on any device. In addition, our experts in survey design can help you craft questionnaires that evoke thoughtful responses and authentic insights.

Learn more about how Kantar can increase the accuracy and reliability of your consumer research data

Consumer research can be a helpful tool for understanding the preferences, values, and behaviours of your target audience. However, only high-quality consumer research data can help your organisation make well-informed decisions that truly satisfy consumer wants and needs. Learn more about the survey fraud the industry is seeing today and how Kantar can boost the quality of your consumer data quality in the State of Online Research Panels .

Want more like this?

Read: 11 survey design best practices to increase effectiveness

Read: How do you create a questionnaire for consumer insights?

Read: 3 ways to improve the quality of your research data

Watch: Everything you need to know about collecting high quality data

The State of Online Research Panels

The past, present, and future of consumer research

- Published: 13 June 2020

- Volume 31 , pages 137–149, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Maayan S. Malter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0383-7925 1 ,

- Morris B. Holbrook 1 ,

- Barbara E. Kahn 2 ,

- Jeffrey R. Parker 3 &

- Donald R. Lehmann 1

47k Accesses

39 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

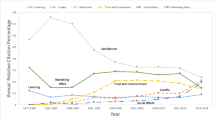

In this article, we document the evolution of research trends (concepts, methods, and aims) within the field of consumer behavior, from the time of its early development to the present day, as a multidisciplinary area of research within marketing. We describe current changes in retailing and real-world consumption and offer suggestions on how to use observations of consumption phenomena to generate new and interesting consumer behavior research questions. Consumption continues to change with technological advancements and shifts in consumers’ values and goals. We cannot know the exact shape of things to come, but we polled a sample of leading scholars and summarize their predictions on where the field may be headed in the next twenty years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Consumer Behavior Research Methods

Consumer dynamics: theories, methods, and emerging directions

Understanding effect sizes in consumer psychology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Beginning in the late 1950s, business schools shifted from descriptive and practitioner-focused studies to more theoretically driven and academically rigorous research (Dahl et al. 1959 ). As the field expanded from an applied form of economics to embrace theories and methodologies from psychology, sociology, anthropology, and statistics, there was an increased emphasis on understanding the thoughts, desires, and experiences of individual consumers. For academic marketing, this meant that research not only focused on the decisions and strategies of marketing managers but also on the decisions and thought processes on the other side of the market—customers.

Since then, the academic study of consumer behavior has evolved and incorporated concepts and methods, not only from marketing at large but also from related social science disciplines, and from the ever-changing landscape of real-world consumption behavior. Its position as an area of study within a larger discipline that comprises researchers from diverse theoretical backgrounds and methodological training has stirred debates over its identity. One article describes consumer behavior as a multidisciplinary subdiscipline of marketing “characterized by the study of people operating in a consumer role involving acquisition, consumption, and disposition of marketplace products, services, and experiences” (MacInnis and Folkes 2009 , p. 900).

This article reviews the evolution of the field of consumer behavior over the past half century, describes its current status, and predicts how it may evolve over the next twenty years. Our review is by no means a comprehensive history of the field (see Schumann et al. 2008 ; Rapp and Hill 2015 ; Wang et al. 2015 ; Wilkie and Moore 2003 , to name a few) but rather focuses on a few key thematic developments. Though we observe many major shifts during this period, certain questions and debates have persisted: Does consumer behavior research need to be relevant to marketing managers or is there intrinsic value from studying the consumer as a project pursued for its own sake? What counts as consumption: only consumption from traditional marketplace transactions or also consumption in a broader sense of non-marketplace interactions? Which are the most appropriate theoretical traditions and methodological tools for addressing questions in consumer behavior research?

2 A brief history of consumer research over the past sixty years—1960 to 2020

In 1969, the Association for Consumer Research was founded and a yearly conference to share marketing research specifically from the consumer’s perspective was instituted. This event marked the culmination of the growing interest in the topic by formalizing it as an area of research within marketing (consumer psychology had become a formalized branch of psychology within the APA in 1960). So, what was consumer behavior before 1969? Scanning current consumer-behavior doctoral seminar syllabi reveals few works predating 1969, with most of those coming from psychology and economics, namely Herbert Simon’s A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice (1955), Abraham Maslow’s A Theory of Human Motivation (1943), and Ernest Dichter’s Handbook of Consumer Motivations (1964). In short, research that illuminated and informed our understanding of consumer behavior prior to 1969 rarely focused on marketing-specific topics, much less consumers or consumption (Dichter’s handbook being a notable exception). Yet, these works were crucial to the rise of consumer behavior research because, in the decades after 1969, there was a shift within academic marketing to thinking about research from a behavioral or decision science perspective (Wilkie and Moore 2003 ). The following section details some ways in which this shift occurred. We draw on a framework proposed by the philosopher Larry Laudan ( 1986 ), who distinguished among three inter-related aspects of scientific inquiry—namely, concepts (the relevant ideas, theories, hypotheses, and constructs); methods (the techniques employed to test and validate these concepts); and aims (the purposes or goals that motivate the investigation).

2.1 Key concepts in the late - 1960s

During the late-1960s, we tended to view the buyer as a computer-like machine for processing information according to various formal rules that embody economic rationality to form a preference for one or another option in order to arrive at a purchase decision. This view tended to manifest itself in a couple of conspicuous ways. The first was a model of buyer behavior introduced by John Howard in 1963 in the second edition of his marketing textbook and quickly adopted by virtually every theorist working in our field—including, Howard and Sheth (of course), Engel-Kollat-&-Blackwell, Franco Nicosia, Alan Andreasen, Jim Bettman, and Joel Cohen. Howard’s great innovation—which he based on a scheme that he had found in the work of Plato (namely, the linkages among Cognition, Affect, and Conation)—took the form of a boxes-and-arrows formulation heavily influenced by the approach to organizational behavior theory that Howard (University of Pittsburgh) had picked up from Herbert Simon (Carnegie Melon University). The model represented a chain of events

where I = inputs of information (from advertising, word-of-mouth, brand features, etc.); C = cognitions (beliefs or perceptions about a brand); A = Affect (liking or preference for the brand); B = behavior (purchase of the brand); and S = satisfaction (post-purchase evaluation of the brand that feeds back onto earlier stages of the sequence, according to a learning model in which reinforced behavior tends to be repeated). This formulation lay at the heart of Howard’s work, which he updated, elaborated on, and streamlined over the remainder of his career. Importantly, it informed virtually every buyer-behavior model that blossomed forth during the last half of the twentieth century.

To represent the link between cognitions and affect, buyer-behavior researchers used various forms of the multi-attribute attitude model (MAAM), originally proposed by psychologists such as Fishbein and Rosenberg as part of what Fishbein and Ajzen ( 1975 ) called the theory of reasoned action. Under MAAM, cognitions (beliefs about brand attributes) are weighted by their importance and summed to create an explanation or prediction of affect (liking for a brand or preference for one brand versus another), which in turn determines behavior (choice of a brand or intention to purchase a brand). This took the work of economist Kelvin Lancaster (with whom Howard interacted), which assumed attitude was based on objective attributes, and extended it to include subjective ones (Lancaster 1966 ; Ratchford 1975 ). Overall, the set of concepts that prevailed in the late-1960s assumed the buyer exhibited economic rationality and acted as a computer-like information-processing machine when making purchase decisions.

2.2 Favored methods in the late-1960s

The methods favored during the late-1960s tended to be almost exclusively neo-positivistic in nature. That is, buyer-behavior research adopted the kinds of methodological rigor that we associate with the physical sciences and the hypothetico-deductive approaches advocated by the neo-positivistic philosophers of science.

Thus, the accepted approaches tended to be either experimental or survey based. For example, numerous laboratory studies tested variations of the MAAM and focused on questions about how to measure beliefs, how to weight the beliefs, how to combine the weighted beliefs, and so forth (e.g., Beckwith and Lehmann 1973 ). Here again, these assumed a rational economic decision-maker who processed information something like a computer.

Seeking rigor, buyer-behavior studies tended to be quantitative in their analyses, employing multivariate statistics, structural equation models, multidimensional scaling, conjoint analysis, and other mathematically sophisticated techniques. For example, various attempts to test the ICABS formulation developed simultaneous (now called structural) equation models such as those deployed by Farley and Ring ( 1970 , 1974 ) to test the Howard and Sheth ( 1969 ) model and by Beckwith and Lehmann ( 1973 ) to measure halo effects.

2.3 Aims in the late-1960s

During this time period, buyer-behavior research was still considered a subdivision of marketing research, the purpose of which was to provide insights useful to marketing managers in making strategic decisions. Essentially, every paper concluded with a section on “Implications for Marketing Managers.” Authors who failed to conform to this expectation could generally count on having their work rejected by leading journals such as the Journal of Marketing Research ( JMR ) and the Journal of Marketing ( JM ).

2.4 Summary—the three R’s in the late-1960s

Starting in the late-1960s to the early-1980s, virtually every buyer-behavior researcher followed the traditional approach to concepts, methods, and aims, now encapsulated under what we might call the three R’s —namely, rationality , rigor , and relevance . However, as we transitioned into the 1980s and beyond, that changed as some (though by no means all) consumer researchers began to expand their approaches and to evolve different perspectives.

2.5 Concepts after 1980

In some circles, the traditional emphasis on the buyer’s rationality—that is, a view of the buyer as a rational-economic, decision-oriented, information-processing, computer-like machine for making choices—began to evolve in at least two primary ways.

First, behavioral economics (originally studied in marketing under the label Behavioral Decision Theory)—developed in psychology by Kahneman and Tversky, in economics by Thaler, and applied in marketing by a number of forward-thinking theorists (e.g., Eric Johnson, Jim Bettman, John Payne, Itamar Simonson, Jay Russo, Joel Huber, and more recently, Dan Ariely)—challenged the rationality of consumers as decision-makers. It was shown that numerous commonly used decision heuristics depart from rational choice and are exceptions to the traditional assumptions of economic rationality. This trend shed light on understanding consumer financial decision-making (Prelec and Loewenstein 1998 ; Gourville 1998 ; Lynch Jr 2011 ) and how to develop “nudges” to help consumers make better decisions for their personal finances (summarized in Johnson et al. 2012 ).

Second, the emerging experiential view (anticipated by Alderson, Levy, and others; developed by Holbrook and Hirschman, and embellished by Schmitt, Pine, and Gilmore, and countless followers) regarded consumers as flesh-and-blood human beings (rather than as information-processing computer-like machines), focused on hedonic aspects of consumption, and expanded the concepts embodied by ICABS (Table 1 ).

2.6 Methods after 1980

The two burgeoning areas of research—behavioral economics and experiential theories—differed in their methodological approaches. The former relied on controlled randomized experiments with a focus on decision strategies and behavioral outcomes. For example, experiments tested the process by which consumers evaluate options using information display boards and “Mouselab” matrices of aspects and attributes (Payne et al. 1988 ). This school of thought also focused on behavioral dependent measures, such as choice (Huber et al. 1982 ; Simonson 1989 ; Iyengar and Lepper 2000 ).

The latter was influenced by post-positivistic philosophers of science—such as Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend, and Richard Rorty—and approaches expanded to include various qualitative techniques (interpretive, ethnographic, humanistic, and even introspective methods) not previously prominent in the field of consumer research. These included:

Interpretive approaches —such as those drawing on semiotics and hermeneutics—in an effort to gain a richer understanding of the symbolic meanings involved in consumption experiences;

Ethnographic approaches — borrowed from cultural anthropology—such as those illustrated by the influential Consumer Behavior Odyssey (Belk et al. 1989 ) and its discoveries about phenomena related to sacred aspects of consumption or the deep meanings of collections and other possessions;

Humanistic approaches —such as those borrowed from cultural studies or from literary criticism and more recently gathered together under the general heading of consumer culture theory ( CCT );

Introspective or autoethnographic approaches —such as those associated with a method called subjective personal introspection ( SPI ) that various consumer researchers like Sidney Levy and Steve Gould have pursued to gain insights based on their own private lives.

These qualitative approaches tended not to appear in the more traditional journals such as the Journal of Marketing , Journal of Marketing Research , or Marketing Science . However, newer journals such as Consumption, Markets, & Culture and Marketing Theory began to publish papers that drew on the various interpretive, ethnographic, humanistic, or introspective methods.

2.7 Aims after 1980

In 1974, consumer research finally got its own journal with the launch of the Journal of Consumer Research ( JCR ). The early editors of JCR —especially Bob Ferber, Hal Kassarjian, and Jim Bettman—held a rather divergent attitude about the importance or even the desirability of managerial relevance as a key goal of consumer studies. Under their influence, some researchers began to believe that consumer behavior is a phenomenon worthy of study in its own right—purely for the purpose of understanding it better. The journal incorporated articles from an array of methodologies: quantitative (both secondary data analysis and experimental techniques) and qualitative. The “right” balance between theoretical insight and substantive relevance—which are not in inherent conflict—is a matter of debate to this day and will likely continue to be debated well into the future.

2.8 Summary—the three I’s after 1980

In sum, beginning in the early-1980s, consumer research branched out. Much of the work in consumer studies remained within the earlier tradition of the three R’s—that is, rationality (an information-processing decision-oriented buyer), rigor (neo-positivistic experimental designs and quantitative techniques), and relevance (usefulness to marketing managers). Nonetheless, many studies embraced enlarged views of the three major aspects that might be called the three I’s —that is, irrationality (broadened perspectives that incorporate illogical, heuristic, experiential, or hedonic aspects of consumption), interpretation (various qualitative or “postmodern” approaches), and intrinsic motivation (the joy of pursuing a managerially irrelevant consumer study purely for the sake of satisfying one’s own curiosity, without concern for whether it does or does not help a marketing practitioner make a bigger profit).

3 The present—the consumer behavior field today

3.1 present concepts.

In recent years, technological changes have significantly influenced the nature of consumption as the customer journey has transitioned to include more interaction on digital platforms that complements interaction in physical stores. This shift poses a major conceptual challenge in understanding if and how these technological changes affect consumption. Does the medium through which consumption occurs fundamentally alter the psychological and social processes identified in earlier research? In addition, this shift allows us to collect more data at different stages of the customer journey, which further allows us to analyze behavior in ways that were not previously available.

Revisiting the ICABS framework, many of the previous concepts are still present, but we are now addressing them through a lens of technological change (Table 2 )

. In recent years, a number of concepts (e.g., identity, beliefs/lay theories, affect as information, self-control, time, psychological ownership, search for meaning and happiness, social belonging, creativity, and status) have emerged as integral factors that influence and are influenced by consumption. To better understand these concepts, a number of influential theories from social psychology have been adopted into consumer behavior research. Self-construal (Markus and Kitayama 1991 ), regulatory focus (Higgins 1998 ), construal level (Trope and Liberman 2010 ), and goal systems (Kruglanski et al. 2002 ) all provide social-cognition frameworks through which consumer behavior researchers study the psychological processes behind consumer behavior. This “adoption” of social psychological theories into consumer behavior is a symbiotic relationship that further enhances the theories. Tory Higgins happily stated that he learned more about his own theories from the work of marketing academics (he cited Angela Lee and Michel Pham) in further testing and extending them.

3.2 Present Methods

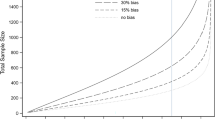

Not only have technological advancements changed the nature of consumption but they have also significantly influenced the methods used in consumer research by adding both new sources of data and improved analytical tools (Ding et al. 2020 ). Researchers continue to use traditional methods from psychology in empirical research (scale development, laboratory experiments, quantitative analyses, etc.) and interpretive approaches in qualitative research. Additionally, online experiments using participants from panels such as Amazon Mechanical Turk and Prolific have become commonplace in the last decade. While they raise concerns about the quality of the data and about the external validity of the results, these online experiments have greatly increased the speed and decreased the cost of collecting data, so researchers continue to use them, albeit with some caution. Reminiscent of the discussion in the 1970s and 1980s about the use of student subjects, the projectability of the online responses and of an increasingly conditioned “professional” group of online respondents (MTurkers) is a major concern.

Technology has also changed research methodology. Currently, there is a large increase in the use of secondary data thanks to the availability of Big Data about online and offline behavior. Methods in computer science have advanced our ability to analyze large corpuses of unstructured data (text, voice, visual images) in an efficient and rigorous way and, thus, to tap into a wealth of nuanced thoughts, feelings, and behaviors heretofore only accessible to qualitative researchers through laboriously conducted content analyses. There are also new neuro-marketing techniques like eye-tracking, fMRI’s, body arousal measures (e.g., heart rate, sweat), and emotion detectors that allow us to measure automatic responses. Lastly, there has been an increase in large-scale field experiments that can be run in online B2C marketplaces.

3.3 Present Aims

Along with a focus on real-world observations and data, there is a renewed emphasis on managerial relevance. Countless conference addresses and editorials in JCR , JCP , and other journals have emphasized the importance of making consumer research useful outside of academia—that is, to help companies, policy makers, and consumers. For instance, understanding how the “new” consumer interacts over time with other consumers and companies in the current marketplace is a key area for future research. As global and social concerns become more salient in all aspects of life, issues of long-term sustainability, social equality, and ethical business practices have also become more central research topics. Fortunately, despite this emphasis on relevance, theoretical contributions and novel ideas are still highly valued. An appropriate balance of theory and practice has become the holy grail of consumer research.

The effects of the current trends in real-world consumption will increase in magnitude with time as more consumers are digitally native. Therefore, a better understanding of current consumer behavior can give us insights and help predict how it will continue to evolve in the years to come.

4 The future—the consumer behavior field in 2040

The other papers use 2030 as a target year but we asked our survey respondents to make predictions for 2040 and thus we have a different future target year.

Niels Bohr once said, “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” Indeed, it would be a fool’s errand for a single person to hazard a guess about the state of the consumer behavior field twenty years from now. Therefore, predictions from 34 active consumer researchers were collected to address this task. Here, we briefly summarize those predictions.

4.1 Future Concepts

While few respondents proffered guesses regarding specific concepts that would be of interest twenty years from now, many suggested broad topics and trends they expected to see in the field. Expectations for topics could largely be grouped into three main areas. Many suspected that we will be examining essentially the same core topics, perhaps at a finer-grained level, from different perspectives or in ways that we currently cannot utilize due to methodological limitations (more on methods below). A second contingent predicted that much research would center on the impending crises the world faces today, most mentioning environmental and social issues (the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet begun when these predictions were collected and, unsurprisingly, was not anticipated by any of our respondents). The last group, citing the widely expected profound impact of AI on consumers’ lives, argued that AI and other technology-related topics will be dominant subjects in consumer research circa 2040.

While the topic of technology is likely to be focal in the field, our current expectations for the impact of technology on consumers’ lives are narrower than it should be. Rather than merely offering innumerable conveniences and experiences, it seems likely that technology will begin to be integrated into consumers’ thoughts, identities, and personal relationships—probably sooner than we collectively expect. The integration of machines into humans’ bodies and lives will present the field with an expanding list of research questions that do not exist today. For example, how will the concepts of the self, identity, privacy, and goal pursuit change when web-connected technology seamlessly integrates with human consciousness and cognition? Major questions will also need to be answered regarding philosophy of mind, ethics, and social inequality. We suspect that the impact of technology on consumers and consumer research will be far broader than most consumer-behavior researchers anticipate.

As for broader trends within consumer research, there were two camps: (1) those who expect (or hope) that dominant theories (both current and yet to be developed) will become more integrated and comprehensive and (2) those who expect theoretical contributions to become smaller and smaller, to the point of becoming trivial. Both groups felt that current researchers are filling smaller cracks than before, but disagreed on how this would ultimately be resolved.

4.2 Future Methods

As was the case with concepts, respondents’ expectations regarding consumer-research methodologies in 2030 can also be divided into three broad baskets. Unsurprisingly, many indicated that we would be using many technologies not currently available or in wide use. Perhaps more surprising was that most cited the use of technology such as AI, machine-learning algorithms, and robots in designing—as opposed to executing or analyzing—experiments. (Some did point to the use of technologies such as virtual reality in the actual execution of experiments.) The second camp indicated that a focus on reliable and replicable results (discussed further below) will encourage a greater tendency for pre-registering studies, more use of “Big Data,” and a demand for more studies per paper (versus more papers per topic, which some believe is a more fruitful direction). Finally, the third lot indicated that “real data” would be in high demand, thereby necessitating the use of incentive-compatible, consequential dependent variables and a greater prevalence of field studies in consumer research.

As a result, young scholars would benefit from developing a “toolkit” of methodologies for collecting and analyzing the abundant new data of interest to the field. This includes (but is not limited to) a deep understanding of designing and implementing field studies (Gerber and Green 2012 ), data analysis software (R, Python, etc.), text mining and analysis (Humphreys and Wang 2018 ), and analytical tools for other unstructured forms of data such as image and sound. The replication crisis in experimental research means that future scholars will also need to take a more critical approach to validity (internal, external, construct), statistical power, and significance in their work.

4.3 Future Aims

While there was an air of existential concern about the future of the field, most agreed that the trend will be toward increasing the relevance and reliability of consumer research. Specifically, echoing calls from journals and thought leaders, the respondents felt that papers will need to offer more actionable implications for consumers, managers, or policy makers. However, few thought that this increased focus would come at the expense of theoretical insights, suggesting a more demanding overall standard for consumer research in 2040. Likewise, most felt that methodological transparency, open access to data and materials, and study pre-registration will become the norm as the field seeks to allay concerns about the reliability and meaningfulness of its research findings.

4.4 Summary - Future research questions and directions

Despite some well-justified pessimism, the future of consumer research is as bright as ever. As we revised this paper amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that many aspects of marketplace behavior, consumption, and life in general will change as a result of this unprecedented global crisis. Given this, and the radical technological, social, and environmental changes that loom on the horizon, consumer researchers will have a treasure trove of topics to tackle in the next ten years, many of which will carry profound substantive importance. While research approaches will evolve, the core goals will remain consistent—namely, to generate theoretically insightful, empirically supported, and substantively impactful research (Table 3 ).

5 Conclusion

At any given moment in time, the focal concepts, methods, and aims of consumer-behavior scholarship reflect both the prior development of the field and trends in the larger scientific community. However, despite shifting trends, the core of the field has remained constant—namely, to understand the motivations, thought processes, and experiences of individuals as they consume goods, services, information, and other offerings, and to use these insights to develop interventions to improve both marketing strategy for firms and consumer welfare for individuals and groups. Amidst the excitement of new technologies, social trends, and consumption experiences, it is important to look back and remind ourselves of the insights the field has already generated. Effectively integrating these past findings with new observations and fresh research will help the field advance our understanding of consumer behavior.

Beckwith, N. E., & Lehmann, D. R. (1973). The importance of differential weights in multiple attribute models of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 10 (2), 141–145.

Article Google Scholar

Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry Jr., J. F. (1989). The sacred and the profane in consumer behavior: theodicy on the odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (1), 1–38.

Dahl, R. A., Haire, M., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1959). Social science research on business: product and potential . New York: Columbia University Press.

Ding, Y., DeSarbo, W. S., Hanssens, D. M., Jedidi, K., Lynch Jr., J. G., & Lehmann, D. R. (2020). The past, present, and future of measurements and methods in marketing analysis. Marketing Letters, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09527-7 .

Farley, J. U., & Ring, L. W. (1970). An empirical test of the Howard-Sheth model of buyer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 7 (4), 427–438.

Farley, J. U., & Ring, L. W. (1974). “Empirical” specification of a buyer behavior model. Journal of Marketing Research, 11 (1), 89–96.

Google Scholar

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research . Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. P. (2012). Field experiments: design, analysis, and interpretation . New York: WW Norton.

Gourville, J. T. (1998). Pennies-a-day: the effect of temporal reframing on transaction evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (4), 395–408.

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30 , 1–46.

Howard, J. A., & Sheth, J. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior . New York: Wiley.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., & Puto, C. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (1), 90–98.

Humphreys, A., & Wang, R. J. H. (2018). Automated text analysis for consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (6), 1274–1306.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79 (6), 995–1006.

Johnson, E. J., Shu, S. B., Dellaert, B. G., Fox, C., Goldstein, D. G., Häubl, G., et al. (2012). Beyond nudges: tools of a choice architecture. Marketing Letters, 23 (2), 487–504.

Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Fishbach, A., Friedman, R., Chun, W. Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal systems. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34 , 311–378.

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new theory of consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 74 , 132–157.

Laudan, L. (1986). Methodology’s prospects. In PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, 1986 (2), 347–354.

Lynch Jr., J. G. (2011). Introduction to the journal of marketing research special interdisciplinary issue on consumer financial decision making. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (SPL) Siv–Sviii.

MacInnis, D. J., & Folkes, V. S. (2009). The disciplinary status of consumer behavior: a sociology of science perspective on key controversies. Journal of Consumer Research, 36 (6), 899–914.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98 (2), 224–253.

Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1988). Adaptive strategy selection in decision making. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14 (3), 534–552.

Prelec, D., & Loewenstein, G. (1998). The red and the black: mental accounting of savings and debt. Marketing Science, 17 (1), 4–28.

Rapp, J. M., & Hill, R. P. (2015). Lordy, Lordy, look who’s 40! The Journal of Consumer Research reaches a milestone. Journal of Consumer Research, 42 (1), 19–29.

Ratchford, B. T. (1975). The new economic theory of consumer behavior: an interpretive essay. Journal of Consumer Research, 2 (2), 65–75.

Schumann, D. W., Haugtvedt, C. P., & Davidson, E. (2008). History of consumer psychology. In Haugtvedt, C. P., Herr, P. M., & Kardes, F. R. eds. Handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 3-28). New York: Erlbaum.

Simonson, I. (1989). Choice based on reasons: the case of attraction and compromise effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (2), 158–174.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117 (2), 440–463.

Wang, X., Bendle, N. T., Mai, F., & Cotte, J. (2015). The journal of consumer research at 40: a historical analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 42 (1), 5–18.

Wilkie, W. L., & Moore, E. S. (2003). Scholarly research in marketing: exploring the “4 eras” of thought development. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 22 (2), 116–146.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Columbia Business School, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Maayan S. Malter, Morris B. Holbrook & Donald R. Lehmann

The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Barbara E. Kahn

Department of Marketing, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Jeffrey R. Parker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maayan S. Malter .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Malter, M.S., Holbrook, M.B., Kahn, B.E. et al. The past, present, and future of consumer research. Mark Lett 31 , 137–149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09526-8

Download citation

Published : 13 June 2020

Issue Date : September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09526-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Consumer behavior

- Information processing

- Judgement and decision-making

- Consumer culture theory

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Association for Consumer Research

Join us for an unforgettable weekend, celebrating the best and brightest in Consumer Research

Join us in paradise for AP-ACR 2024, as the best and brightest in Consumer Research travel to Bali.

Global Thought Leaders in Consumer Research

The Association for Consumer Research is a collection of academics, practitioners, and government leaders devoted to the study of consumer behavior. Together, ACR members use a variety of cutting-edge research methods to uncover consumer insights and disperse this knowledge to improve consumer, business, and social outcomes.

Conferences and Events

Championing research that deepens our understanding of consumer behavior from every angle.

Research Journal (JACR)

The Journal of the Association for Consumer Research (JACR) is a collection of the latest research findings from the world’s leading consumer research and marketing scholars.

Consumer Research Experts

ACR is a community of thought leaders representing academia, industry, and government who share a passion for understanding consumer behavior.

Recent News

Acr sheth foundation conference scholarship.