A Czech soldier and civilians tune in. Prague, 1968. Photo by Mondadori/Getty

The other side of the curtain

During the cold war, us propagandists worked to provide a counterweight to communist media, but truth eluded them all.

by Melissa Feinberg + BIO

On 22 December 1949, with Cold War tensions running high, the United States president Harry S Truman gave a speech to dedicate the carillon at Arlington National Cemetery. Freedom, Truman declared, was the core of the American creed. Those buried at Arlington had given their lives to defend it. They had prevailed, but war once again threatened the freedom they had fought so hard to protect. Few, Truman claimed, wanted war. ‘If we could mobilise world opinion among all men who walk the Earth,’ he said, ‘there would never be another war.’ The problem was that many people were not free to choose peace. Truman called them the captive peoples. They were kept in ignorance by their governments, who prevented them from seeing the truth about the world. They were the puppets of their leaders, who forced them to oppose the West, and to reject its offers of peace and friendship.

To put it in contemporary terms, these so-called captive peoples were the victims of fake news. They were bombarded with lies disguised as truth, and conned into supporting their own oppressors. Truman claimed that if the captive peoples were given access to the truth they would support the goals of the free world. In 1950, his administration proposed a ‘Campaign of Truth’ as part of the battle against Communism.

US officials did not portray their efforts as propaganda. In their minds, they were simply providing accurate information about the world to those who were trapped behind the Iron Curtain. Yet, during the early years of the Cold War, just like today, truth and ideology were intricately intertwined. The US would try to bring truth to the captive peoples of the world, but its truth was never value-free.

The very idea that there were ‘captive peoples’ or ‘captive nations’ would be one of the truths that the US would export. In his speech, Truman did not identify the captive peoples. He didn’t need to. The term had originated in the 1920s with Ukrainian and Caucasian nationalists who protested the incorporation of their homelands into the Soviet Union. But by 1949, most Americans used it to refer to the peoples of the newly Communist countries of eastern Europe.

Anti-Communist east Europeans who had fled their countries after the imposition of Communist rule embraced the label of captive nations. For these exiles and their US allies, the idea that east Europeans were captives was a simple matter of fact. The Communist governments of eastern Europe were dictatorships, and they used terror to consolidate their rule. Criticising these regimes was dangerous. Internal security services (often referred to as the secret police) used networks of informers to weed out opponents. From 1948-53, hundreds of thousands of east Europeans were jailed or sent to labour camps for political reasons.

But calling east Europeans captives was a matter of ideological conviction as well as fact. The term suggested that east Europeans were helpless victims languishing under a foreign oppressor. It implied that they were not responsible for the actions of their governments. It also suggested that no east Europeans truly supported Communism. Rather, they were coerced into submission. In recent decades, historians of eastern Europe have established that this picture is too simple to encapsulate the variety of experience in Communist eastern Europe. During the early Cold War, however, few challenged its validity.

P ortraying east Europeans as captives also implied that they were cut off from the rest of the world. In reality, the Iron Curtain was never the impenetrable barrier many imagined it to be. Even if they could not travel themselves, east Europeans had access to ideas and information from the West. A number of western radio stations, including the BBC and Voice of America (VOA), served east Europeans during the Cold War.

One of these radio stations, Radio Free Europe (RFE), was created in 1950 specifically to broadcast to eastern Europe. Based in Munich and staffed by a mix of east European émigrés and Americans, RFE presented itself as a non-governmental organisation funded by the donations of ordinary US citizens who gave ‘truth dollars’ to enlighten captive east Europeans. In reality, the station relied on funding from the CIA.

RFE’s purpose was to provide a counterpoint to eastern Europe’s Communist-led news media. For RFE, ‘Communist news’ was ‘fake news’: it was propaganda with no basis in fact. RFE would challenge this propaganda by exposing its lies. RFE’s mission was to transmit objectively true news stories to eastern Europe. Its employees did not set out to spread disinformation. Nonetheless, their sense of what was newsworthy was strongly influenced by their anti-Communist ideology. Their broadcasts might not have been ‘fake’ but they were definitely biased. This bias would be transmitted to RFE’s audience as the truth.

One RFE programme, ‘The Other Side of the Coin’, was dedicated to exposing the lies in Communist news. This show, which had separate Czech- and Polish-language versions, would repeat stories from the Czechoslovak or Polish news, and then tell the audience what the real facts were. In a May 1951 episode for the Czech version, the narrator declared that the Czechoslovak press heaped up so many lies that the general rule of thumb was to always assume that the truth was precisely the opposite of what the Communist-dominated media asserted.

Some thought racial discrimination didn’t really exist in the US because they’d read about it in Polish newspapers

To judge the impact of their broadcasts to eastern Europe, western radio stations such as RFE were forced to rely on refugees who had illegally fled across the Iron Curtain. Data gathered from these refugees suggested that audiences at home did regard western radio broadcasts as more truthful and more objective than their local news media. A number of refugees reported that they followed the practice RFE suggested in ‘The Other Side of the Coin’, and always assumed that the truth was the opposite of whatever their local media told them. Some Polish refugees took this to extremes. They claimed that racial discrimination must not really exist in the US because they had read about it in Polish newspapers.

Eastern Europe’s domestic news media often presented Bulgarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Hungarians and Romanians as happily engaged in building socialism. In contrast, RFE’s staffers were certain that east Europeans were powerless victims forced to acquiesce to Communist rule by fear and terror. Many of RFE’s early broadcasts concentrated on refuting what it saw as Communist lies by presenting east Europeans with news about their own oppression.

Some RFE stories were devoted to exposing brutality in prisons and labour camps. One broadcast from the Romanian service from February 1951 consisted entirely of accusations of police cruelty, noting offenders by name and location. ‘The list of the victims of these criminals is much too long to be read,’ intoned the narrator. ‘It is made up of men murdered, men who vanished in the prisons of Bucharest, of patriots who were picked up at home in the eyes of their families, or in the streets, or sent to Russia, or to work on the canal, or to the darkness of the mines at Ocnele Mari, or of the workers beaten up and maimed or disabled for life, of students manhandled because they refused to bow their heads or sell their souls to the Communist beast, or even of innocent women and children accused of being “reactionary”.’

Other programmes were devoted to exposing people who supposedly worked as informers for the secret police. According to refugee reports, these programmes were popular and influential. In 1951, for example, the VOA interviewed a young Hungarian refugee identified only as ‘KA’. KA singled out the Bálint Boda show on RFE as his favourite programme, specifically because Boda named secret police informers on air. A series in which Boda listed all the informers in KA’s home village of Suttor made a big impression on him. ‘He named several persons we would never have thought were informers,’ KA remarked. Whenever Boda named informers in the area, KA wrote down their names. He even once went by bicycle to a nearby village to tell some relatives who lived there the names of those whom RFE alleged were informers. While some of the names surprised KA, he did not doubt Boda’s accusations. The information came from the West, and he believed it. RFE had helped him to see his own community as infested with spies.

Was the information KA heard on RFE actually true? There is no way to know for sure. RFE undoubtedly got the names it broadcast either from a refugee such as KA himself or from an anti-Communist contact inside Hungary. Other than to check it against the statements of other refugees or similar informants, its analysts had no way to fact-check this kind of information. RFE’s journalistic standards would grow more professional, but in the early 1950s, their anti-Communist fervour often persuaded them to accept unsubstantiated statements as fact. Once broadcast, these rumours acquired an aura of credibility.

A ccording to interviews with refugees from the early 1950s, many east Europeans believed that the secret police had informers everywhere. In 1951, for example, one source told RFE that the Czechoslovak secret police had agents in all workplaces, coffeehouses, pubs, restaurants, movie theatres and places of amusement. With every utterance against the regime, the source said, people expected the concentration camp. A Bulgarian who left his country in 1951 made similar statements, declaring: ‘In Sofia, there are more secret police agents than flies. They are everywhere, at every corner of the streets, in every public place.’ The Bulgarian’s claims echoed those of a young Hungarian refugee who told RFE in 1954: ‘The number of spies in the country cannot be figured. If someone makes an unequivocal remark he will be arrested immediately and will be tortured.’

Recent research on eastern European security services from this period makes it clear that there were not nearly as many police informers as these refugees imagined there were. Nonetheless, many east Europeans believed these kinds of statements to be true, as did RFE. The radio station and its audience had got caught in a feedback loop. Listeners heard broadcasts that told them about informers in their neighbourhoods. They believed them, and began to imagine even more informers lurking in the shadows. Some of these listeners then fled and became refugees. They told RFE that informers were everywhere. RFE judged their statements to be probably true because other refugees had given similar accounts, and because they matched RFE’s own presumptions about life under Communism. These new refugee statements were then used as material for future broadcasts.

RFE’s constant emphasis on Communist terror had an another unintended effect: it encouraged east Europeans to see themselves as powerless. RFE staffers eventually realised this. As an internal RFE document noted: ‘by highlighting the scope of this terror, [RFE] unconsciously embarked upon promoting its irresistible power’. By bombarding its audience with tales of Communist evil, RFE potentially increased its listeners’ sense of vulnerability and weakness. One internal analysis asked: ‘As we emphasise the injustices the prisoner peoples are forced to endure, do we not also underline their essential helplessness?’ In other words, RFE encouraged its listeners to identify with the image of themselves as captive peoples.

All the theories predicted that Communism would fall. None required action on the part of ordinary people

Refugees and other informants who spoke to RFE in the early 1950s mirrored the ways that the western media talked about east Europeans as powerless captives. People opposed the Communist system, they said, but felt trapped in the face of its enormous repressive apparatus. A 31-year-old Czech man from the town of Gottwaldov told RFE that everyone in the city was ‘waiting from one year to the next for the liberation, in the way in which a prisoner waits for the day in which he will be released from prison’. Unlike most prisoners, however, their release would only come from outside intervention. The residents of Gottwaldov accepted their status as passive victims. They did not act, they only waited, hoping to be saved by military intervention from the West.

The Czech man from Gottwaldov told RFE that many people he knew took refuge in mystical theories that purported to reveal the day of liberation from Communism. Proponents of the ‘Pyramid Theory’ for example, believed that calculations based upon the length of the corridors in Egyptian pyramids proved that Communism would end on 20 August 1953. Adherents of the ‘Titanic Theory’ claimed that Communists would suffer the same downfall as the designers of RMS Titanic , who mocked the power of God by claiming that they had built an unsinkable ship. All these theories predicted that Communism would suffer an inevitable fall. None of them required action on the part of ordinary people.

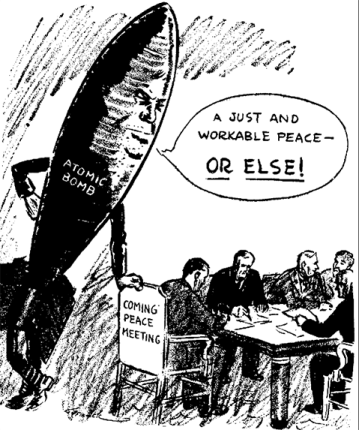

Among those who spoke to RFE and other radio stations, such magical thinking was very common. Many expressed it in the form of a war fantasy: they dreamed of a new world war that would drive the Communists from eastern Europe. In the fantasy, the West always won, and eastern Europe somehow escaped with little damage. Boguslawa Smolka-Bauer, a high-school teacher from Poland who left the country in 1951, told an interviewer that most Poles believed war would liberate them from Communism. ‘People think that America will, first of all, hit Russia with atomic bombs, while US armies will immediately invade the satellite countries,’ she said. They imagined the atomic weapons would hurt only the Russians, and Poland would be painlessly liberated.

Some imagined even more incredible scenarios. One Czech source told RFE in 1952 about a persistent rumour that the Americans had developed a ‘soporific bomb’ that would put everyone not wearing a special mask to sleep; those spared the sudden nap could then easily cut the throats of the comatose Communists. A Hungarian tailor claimed that he read in the Communist newspaper Népszava (Referendum) that the US had used a gas in Korea that put opponents to sleep for 12 hours. The Communists, he said, called this an illegal use of chemical weapons. But the Hungarian tailor and his friends thought it was quite humane, and boded well for the possibilities of another world war.

In these fantasies, east Europeans imagined themselves powerless to oppose the state. Its power was too great and its network of informers too deep. They could do nothing but wait and put their faith in miracle weapons or western armies. These fantasies, however, were just that – fantasies. In everyday life, many east Europeans acted in ways that were anything but powerless.

Refugees who spoke to western radio stations noted that east Europeans often broke the law for economic gain. They hoarded scarce goods, traded on the black market, and stole from their workplaces. A Polish black-market dealer told RFE in 1952: ‘Every law can be broken. The only question is how to go about it.’ Anyone who was even ‘a bit clever’ he said could live well through illegal activity. As a Polish refugee claimed in 1951: ‘swindling is an integral part of the Communist system’. Working on the black market was just as illegal as anti-Communist political activity, yet, according to him, everyone did it. A man from Poznań recounted in 1952 that local police had started to check passengers on trains for contraband as part of a campaign to cut down on the black-market sale of food, especially meat. The source claimed that dozens of people a day were being arrested for bringing meat into the city illegally. Despite the threat of time in a labour camp, people continued to smuggle meat in hopes of making an illicit profit. In these narratives, refugees presented themselves as resourceful and clever, not scared and powerless. They defied the police to do as they wanted.

Of course, risking jail to provide for their families does not mean that they could have successfully rebelled against their Communist governments. The failed Hungarian Revolution of 1956 certainly suggests that even genuinely popular uprisings against Soviet bloc governments faced very long odds. Nonetheless, these refugee accounts tell us that the image of captivity promulgated by the West did not adequately describe the realities of life in Communist eastern Europe. East Europeans did not have many of the freedoms Westerners enjoyed. Yet they were not passive bystanders in their own lives. They acted in defence of their own interests and even opposed the state in significant, if small and personal, ways.

RFE analysts and other western observers who talked to these refugees or read their statements did not comment on these contradictions in their stories. Their own ideological blinders prevented them from seeing their significance. According to the totalitarian thinking of the time (still prominent even today), those who lived under Communist rule were by definition powerless. Only those who lived in the West had any freedom. Because they could see the world only within this totalitarian framework, RFE’s journalists, like most of those in the West, could never fully understand Communist societies.

This history brings another dimension to the current obsession with ‘fake news’. RFE’s mission was to counter disinformation, not to spread it. But even though RFE did not try to broadcast lies, its unwavering anti-Communist stance left it open to accepting unsubstantiated rumours as facts, and prevented its analysts from seeing the significance of their own sources. Most of us don’t want to see our own political convictions as ‘ideology’. We want them to be based on facts. The problem is when we can’t tell the difference.

History of technology

Learning to love monsters

Windmills were once just machines on the land but now seem delightfully bucolic. Could wind turbines win us over too?

Stephen Case

Global history

The route to progress

Anticolonial modernity was founded upon the fight for liberation from communists, capitalists and imperialists alike

Frank Gerits

Philosophy of mind

The problem of erring animals

Three medieval thinkers struggled to explain how animals could make mistakes – and uncovered the nature of nonhuman minds

The disruption nexus

Moments of crisis, such as our own, are great opportunities for historic change, but only under highly specific conditions

Roman Krznaric

What is intelligent life?

Our human minds hold us back from truly understanding the many brilliant ways that other creatures solve their problems

Abigail Desmond & Michael Haslam

Economic history

Economics 101

Why introductory economics courses continued to teach zombie ideas from before economics became an empirical discipline

Walter Frick

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Origins of the Cold War

The struggle between superpowers.

- Toward a new world order

What was the Cold War?

How did the cold war end, why was the cuban missile crisis such an important event in the cold war.

- What was Harry S. Truman's reaction to communist North Korea's attempt to seize noncommunist South Korea in 1950?

- Should the United States maintain the embargo enforced by John F. Kennedy against Cuba?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Chemistry LibreTexts - The Cold War

- The National WWII Museum New Orleans - Cold Conflict

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum - The Cold War

- New Zealand History - The Cold War

- The New York Times - The Blacklist and The Cold War

- Alpha History - The Cold War

- The Canadian Encyclopedia - Cold War

- Cold War - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Cold War - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The Cold War was an ongoing political rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies that developed after World War II . This hostility between the two superpowers was first given its name by George Orwell in an article published in 1945. Orwell understood it as a nuclear stalemate between “super-states”: each possessed weapons of mass destruction and was capable of annihilating the other.

The Cold War began after the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945, when the uneasy alliance between the United States and Great Britain on the one hand and the Soviet Union on the other started to fall apart. The Soviet Union began to establish left-wing governments in the countries of eastern Europe, determined to safeguard against a possible renewed threat from Germany. The Americans and the British worried that Soviet domination in eastern Europe might be permanent. The Cold War was solidified by 1947–48, when U.S. aid had brought certain Western countries under American influence and the Soviets had established openly communist regimes. Nevertheless, there was very little use of weapons on battlefields during the Cold War. It was waged mainly on political, economic, and propaganda fronts and lasted until 1991.

The Cold War came to a close gradually. The unity in the communist bloc was unraveling throughout the 1960s and ’70s as a split occurred between China and the Soviet Union . Meanwhile, Japan and certain Western countries were becoming more economically independent. Increasingly complex international relationships developed as a result, and smaller countries became more resistant to superpower cajoling.

The Cold War truly began to break down during the administration of Mikhail Gorbachev , who changed the more totalitarian aspects of the Soviet government and tried to democratize its political system. Communist regimes began to collapse in eastern Europe, and democratic governments rose in East Germany , Poland , Hungary , and Czechoslovakia , followed by the reunification of West and East Germany under NATO auspices. Gorbachev’s reforms meanwhile weakened his own communist party and allowed power to shift to the constituent governments of the Soviet bloc. The Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991, giving rise to 15 newly independent nations, including a Russia with an anticommunist leader.

In the late 1950s, both the United States and the Soviet Union were developing intercontinental ballistic missiles . In 1962 the Soviet Union began to secretly install missiles in Cuba to launch attacks on U.S. cities. The confrontation that followed, known as the Cuban missile crisis , brought the two superpowers to the brink of war before an agreement was reached to withdraw the missiles.

The conflict showed that both superpowers were wary of using their nuclear weapons against each other for fear of mutual atomic annihilation. The signing of the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty followed in 1963, which banned aboveground nuclear weapons testing. Still, after the crisis, the Soviets were determined not to be humiliated by their military inferiority again, and they began a buildup of conventional and strategic forces that the United States was forced to match for the next 25 years.

Recent News

Trusted Britannica articles, summarized using artificial intelligence, to provide a quicker and simpler reading experience. This is a beta feature. Please verify important information in our full article.

This summary was created from our Britannica article using AI. Please verify important information in our full article.

Cold War , the open yet restricted rivalry that developed after World War II between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies. The Cold War was waged on political, economic, and propaganda fronts and had only limited recourse to weapons. The term was first used by the English writer George Orwell in an article published in 1945 to refer to what he predicted would be a nuclear stalemate between “two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few seconds.” It was first used in the United States by the American financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch in a speech at the State House in Columbia, South Carolina , in 1947.

A brief treatment of the Cold War follows. For full treatment, see international relations .

Following the surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945 near the close of World War II , the uneasy wartime alliance between the United States and Great Britain on the one hand and the Soviet Union on the other began to unravel. By 1948 the Soviets had installed left-wing governments in the countries of eastern Europe that had been liberated by the Red Army . The Americans and the British feared the permanent Soviet domination of eastern Europe and the threat of Soviet-influenced communist parties coming to power in the democracies of western Europe. The Soviets, on the other hand, were determined to maintain control of eastern Europe in order to safeguard against any possible renewed threat from Germany, and they were intent on spreading communism worldwide, largely for ideological reasons. The Cold War had solidified by 1947–48, when U.S. aid provided under the Marshall Plan to western Europe had brought those countries under American influence and the Soviets had installed openly communist regimes in eastern Europe.

The Cold War reached its peak in 1948–53. In this period the Soviets unsuccessfully blockaded the Western-held sectors of West Berlin (1948–49); the United States and its European allies formed the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a unified military command to resist the Soviet presence in Europe (1949); the Soviets exploded their first atomic warhead (1949), thus ending the American monopoly on the atomic bomb; the Chinese communists came to power in mainland China (1949); and the Soviet-supported communist government of North Korea invaded U.S.-supported South Korea in 1950, setting off an indecisive Korean War that lasted until 1953.

From 1953 to 1957 Cold War tensions relaxed somewhat, largely owing to the death of the longtime Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin in 1953; nevertheless, the standoff remained. A unified military organization among the Soviet-bloc countries, the Warsaw Pact , was formed in 1955; and West Germany was admitted into NATO that same year. Another intense stage of the Cold War was in 1958–62. The United States and the Soviet Union began developing intercontinental ballistic missiles , and in 1962 the Soviets began secretly installing missiles in Cuba that could be used to launch nuclear attacks on U.S. cities. This sparked the Cuban missile crisis (1962), a confrontation that brought the two superpowers to the brink of war before an agreement was reached to withdraw the missiles.

The Cuban missile crisis showed that neither the United States nor the Soviet Union were ready to use nuclear weapons for fear of the other’s retaliation (and thus of mutual atomic annihilation). The two superpowers soon signed the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty of 1963 , which banned aboveground nuclear weapons testing. But the crisis also hardened the Soviets’ determination never again to be humiliated by their military inferiority, and they began a buildup of both conventional and strategic forces that the United States was forced to match for the next 25 years.

Throughout the Cold War the United States and the Soviet Union avoided direct military confrontation in Europe and engaged in actual combat operations only to keep allies from defecting to the other side or to overthrow them after they had done so. Thus, the Soviet Union sent troops to preserve communist rule in East Germany (1953), Hungary (1956) , Czechoslovakia (1968) , and Afghanistan (1979) . For its part, the United States helped overthrow a left-wing government in Guatemala (1954) , supported an unsuccessful invasion of Cuba (1961), invaded the Dominican Republic (1965) and Grenada (1983) , and undertook a long (1954–75) and unsuccessful effort to prevent communist North Vietnam from bringing South Vietnam under its rule ( see Vietnam War ).

Propaganda Campaigns During the Cold War

Daniel le may 25, 2017, submitted as coursework for ph241 , stanford university, winter 2017, introduction.

| A clip from a popular Duck and Cover propaganda film that was shown in schools and at home. (Source: ) |

Under the conditions created by the Cold War, the family became a essential target of Government Propaganda. Faced with the daily fear of nuclear annihilation during the Nuclear Age, the Government devoted resources to take advantage of this fear. According to historian Elaine Tyler May, the home and the family "provided heavy protection from the dangers of the outside world." [1] This perception was played on by the government and campaigns were run to instill the ideas of the evils of communism. Particularly American women who were wives and mothers during this era were encouraged through various propaganda techniques to prevent the spread of communism by cultivating patriotism and democratic virtues in the home. [2]

Family Roles

After the making up a large proportion of the labor force during WWII, American women increasingly became homemakers for their families during the Cold War while the men returning from War made up the majority of the work force again. The U.S. Government strongly reinforced these gender roles and images, particularly in regards to women's role in preparing for a potential nuclear attack by running a series of campaigns geared toward American wives. [3] These campaigns were run by the Federal Civil Defense Agency and taught the American public how to survive a nuclear attack. [4]

The two most significant FCDA campaigns were the "Grandma's Pantry" and the "Duck and Cover". The "Grandma" campaign emphasized women's role in keeping a well-stocked house in the event of a nuclear attack. American wives were also encouraged to teach their children what to do during a nuclear attack. The "Duck and Cover" campaign emphasized women's role in teaching her children how to "duck and cover". Brochures from the campaign suggested a mother make "duck and cover" into a game in order to "alleviate her children's fears over a nuclear attack". Fig. 1 is a clip from a Duck and Cover cartoon that was shown to mothers and their children on television and at school. Under Cold War conditions, American wives and mothers were seen as a great target in promoting a strong sense of national security because they were seen as the ones who had the most influence in the home. [3]

Following World War II, the trend was that thousands of new families moved out of cities and into suburbs. This gave new families the opportunity to have their own spaces, unlike the crowded conditions they had previously face in cities. During the Cold War, the home even more so "held out a promise of security in an insecure world." Again, this insecurity was taken advantage of to instill Americans a hatred towards communism and a greater sense of patriotism. [3]

Entertainment

The conditions of fear combined with the rising popularity of the television created an ideal medium for the government to spread their propaganda. Since television and television news were fairly new, networks would seek out sponsorships from other places. Seizing the opportunity, the U.S. defence department became of the primary sponsors to television networks. As a result the content on the television and news heavily revolved around presenting negative perceptions of the Soviet Union. There were also a series of campaigns aimed at how to be a patriotic citizen by supporting democracy, free speech and free markets. Although, the propaganda campaigns promoted free market, the government during this time essentially had control over content of television media. [5]

In conclusion, the common denominator for nearly all cold war propaganda campaigns was the fear and uncertainty of the future. The fear created an environment that the US Government took advantage of in order to convince people the American Way was the right way. Cold War propaganda didn't just stop at the promotion of Western culture, but it also instilled even more fear for communism which begins a cycle of fear, then persuasion through propaganda, to fear and so on.

© Daniel Le. The author grants permission to copy, distribute and display this work in unaltered form, with attribution to the author, for noncommercial purposes only. All other rights, including commercial rights, are reserved to the author.

[1] S. A. Lichtman, "Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America," J. Des. Hist. 19 , 39 (2006).

[2] P. A. Lamphier and W. Rosanne, Women in American History (ABC-CLIO, 2017).

[3] E. T. May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War (Basic Books, 2008).

[4] A. D. Grossman, Neither Dead Nor Red (Routledge, 2001).

[5] N. E. Bernhard, U.S. Television News and Cold War Propaganda, 1947-1960 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Propaganda, psychological warfare and communication research in the USA and the Soviet Union during the Cold War

2016, History of the Human Sciences

This article discusses the role of communication research in the Cold War, moving from a US-centered to a comparative-transnational point of view. It examines research on propaganda and mass communication in the United States and the Soviet Union, focusing not only on the similarities and differences, but also on mutual perceptions and transnational entanglements. In both countries, communication scientists conducted their research with its benefits for propaganda practitioners and waging the Cold War in mind. It has been suggested that after an initial period of close cooperation between politics and communication science, early expectations of the potential of systematic research for controlling the hearts and minds of people through propaganda started to fade. On both sides of the Iron Curtain, communication research eventually became a 'normal' scholarly discipline.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: a Look at Propaganda’s Role

How it works

The Cold War, spanning from the late 1940s to the early 1990s, was not just a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union; it was also an era of intense ideological warfare, where propaganda played a crucial role. This essay explores the use of propaganda during the Cold War, examining its techniques, objectives, and impact on public perception and international relations.

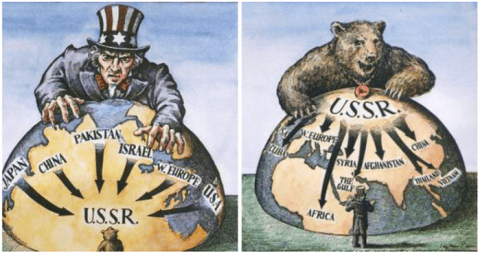

Propaganda in the Cold War was a powerful tool used by both the U.S. and the USSR to spread their ideologies – capitalism and democracy on one side, communism and socialism on the other. This battle for hearts and minds was fought through various mediums, including radio broadcasts, films, literature, and visual arts. Propaganda during this time was not just about promoting one’s own ideology but also about discrediting the opponent’s. The aim was to sway public opinion, influence political attitudes, and gain support or compliance from both domestic and international audiences.

In the United States, propaganda efforts were geared towards highlighting the virtues of freedom and democracy while depicting communism as a threat to the American way of life. Agencies such as the United States Information Agency (USIA) were instrumental in these efforts. Radio broadcasts like Voice of America (VOA) reached millions globally, presenting American news and views. Hollywood also played its part, with films often portraying the Soviet Union as the antagonist. Educational campaigns were designed to ensure Americans were aware of the perceived communist threat, exemplified by initiatives like the “Duck and Cover” drills.

On the other side, the Soviet Union used propaganda to project the superiority of communism and criticize Western imperialism and capitalism. The Soviet government controlled the media, ensuring that all information aligned with communist ideology. The use of art was significant in the USSR’s propaganda, with posters and literature portraying the Soviet life as ideal and prosperous while depicting the West, especially the U.S., as decadent and corrupt. International broadcasting services like Radio Moscow served as a voice of the Soviet Union to the outside world, countering Western narratives.

The impact of Cold War propaganda was profound. It shaped public opinion and perceptions in both blocs, creating a climate of fear and suspicion. In the U.S., it led to the Red Scare and McCarthyism, while in the USSR, it reinforced the control of the Communist Party. Propaganda also influenced foreign policies and international relations, as both superpowers sought to expand their spheres of influence.

However, the effectiveness of Cold War propaganda was not absolute. While it succeeded in molding public opinion to a large extent, there were instances where propaganda efforts backfired or were met with skepticism. The spread of information and cultural exchanges, especially in the later years of the Cold War, allowed people to see beyond propaganda, leading to a more nuanced understanding of the ‘other side’.

In conclusion, propaganda was a key instrument in the ideological battle of the Cold War. It was used by both the U.S. and the USSR to promote their own ideologies and disparage their opponent’s. Through various mediums, propaganda influenced public opinion, shaped political attitudes, and played a significant role in the conduct of foreign policy during this tense period. The legacy of Cold War propaganda continues to be a subject of study for its impact on international relations and its role in shaping the historical narrative of this pivotal era.

Cite this page

The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: A Look at Propaganda's Role. (2023, Dec 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-art-of-persuasion-in-the-cold-war-a-look-at-propagandas-role/

"The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: A Look at Propaganda's Role." PapersOwl.com , 1 Dec 2023, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-art-of-persuasion-in-the-cold-war-a-look-at-propagandas-role/

PapersOwl.com. (2023). The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: A Look at Propaganda's Role . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-art-of-persuasion-in-the-cold-war-a-look-at-propagandas-role/ [Accessed: 4 Jul. 2024]

"The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: A Look at Propaganda's Role." PapersOwl.com, Dec 01, 2023. Accessed July 4, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-art-of-persuasion-in-the-cold-war-a-look-at-propagandas-role/

"The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: A Look at Propaganda's Role," PapersOwl.com , 01-Dec-2023. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-art-of-persuasion-in-the-cold-war-a-look-at-propagandas-role/. [Accessed: 4-Jul-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2023). The Art of Persuasion in the Cold War: A Look at Propaganda's Role . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-art-of-persuasion-in-the-cold-war-a-look-at-propagandas-role/ [Accessed: 4-Jul-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cold War History

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 26, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension marked by competition and confrontation between communist nations led by the Soviet Union and Western democracies including the United States. During World War II , the United States and the Soviets fought together as allies against Nazi Germany . However, U.S./Soviet relations were never truly friendly: Americans had long been wary of Soviet communism and Russian leader Joseph Stalin ’s tyrannical rule. The Soviets resented Americans’ refusal to give them a leading role in the international community, as well as America’s delayed entry into World War II, in which millions of Russians died.

These grievances ripened into an overwhelming sense of mutual distrust and enmity that never developed into open warfare (thus the term “cold war”). Soviet expansionism into Eastern Europe fueled many Americans’ fears of a Russian plan to control the world. Meanwhile, the USSR came to resent what they perceived as U.S. officials’ bellicose rhetoric, arms buildup and strident approach to international relations. In such a hostile atmosphere, no single party was entirely to blame for the Cold War; in fact, some historians believe it was inevitable.

Containment

By the time World War II ended, most American officials agreed that the best defense against the Soviet threat was a strategy called “containment.” In his famous “Long Telegram,” the diplomat George Kennan (1904-2005) explained the policy: The Soviet Union, he wrote, was “a political force committed fanatically to the belief that with the U.S. there can be no permanent modus vivendi [agreement between parties that disagree].” As a result, America’s only choice was the “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.”

“It must be the policy of the United States,” he declared before Congress in 1947, “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation…by outside pressures.” This way of thinking would shape American foreign policy for the next four decades.

Did you know? The term 'cold war' first appeared in a 1945 essay by the English writer George Orwell called 'You and the Atomic Bomb.'

The Cold War: The Atomic Age

The containment strategy also provided the rationale for an unprecedented arms buildup in the United States. In 1950, a National Security Council Report known as NSC–68 had echoed Truman’s recommendation that the country use military force to contain communist expansionism anywhere it seemed to be occurring. To that end, the report called for a four-fold increase in defense spending.

In particular, American officials encouraged the development of atomic weapons like the ones that had ended World War II. Thus began a deadly “ arms race .” In 1949, the Soviets tested an atom bomb of their own. In response, President Truman announced that the United States would build an even more destructive atomic weapon: the hydrogen bomb, or “superbomb.” Stalin followed suit.

As a result, the stakes of the Cold War were perilously high. The first H-bomb test, in the Eniwetok atoll in the Marshall Islands, showed just how fearsome the nuclear age could be. It created a 25-square-mile fireball that vaporized an island, blew a huge hole in the ocean floor and had the power to destroy half of Manhattan. Subsequent American and Soviet tests spewed radioactive waste into the atmosphere.

The ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation had a great impact on American domestic life as well. People built bomb shelters in their backyards. They practiced attack drills in schools and other public places. The 1950s and 1960s saw an epidemic of popular films that horrified moviegoers with depictions of nuclear devastation and mutant creatures. In these and other ways, the Cold War was a constant presence in Americans’ everyday lives.

HISTORY Vault: Nuclear Terror

Now more than ever, terrorist groups are obtaining nuclear weapons. With increasing cases of theft and re-sale at dozens of Russian sites, it's becoming more and more likely for terrorists to succeed.

The Cold War and the Space Race

Space exploration served as another dramatic arena for Cold War competition. On October 4, 1957, a Soviet R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile launched Sputnik (Russian for “traveling companion”), the world’s first artificial satellite and the first man-made object to be placed into the Earth’s orbit. Sputnik’s launch came as a surprise, and not a pleasant one, to most Americans.

In the United States, space was seen as the next frontier, a logical extension of the grand American tradition of exploration, and it was crucial not to lose too much ground to the Soviets. In addition, this demonstration of the overwhelming power of the R-7 missile–seemingly capable of delivering a nuclear warhead into U.S. air space–made gathering intelligence about Soviet military activities particularly urgent.

In 1958, the U.S. launched its own satellite, Explorer I, designed by the U.S. Army under the direction of rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, and what came to be known as the Space Race was underway. That same year, President Dwight Eisenhower signed a public order creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a federal agency dedicated to space exploration, as well as several programs seeking to exploit the military potential of space. Still, the Soviets were one step ahead, launching the first man into space in April 1961.

That May, after Alan Shepard become the first American man in space, President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) made the bold public claim that the U.S. would land a man on the moon by the end of the decade. His prediction came true on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong of NASA’s Apollo 11 mission , became the first man to set foot on the moon, effectively winning the Space Race for the Americans.

U.S. astronauts came to be seen as the ultimate American heroes. Soviets, in turn, were pictured as the ultimate villains, with their massive, relentless efforts to surpass America and prove the power of the communist system.

The Cold War and the Red Scare

Meanwhile, beginning in 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee ( HUAC ) brought the Cold War home in another way. The committee began a series of hearings designed to show that communist subversion in the United States was alive and well.

In Hollywood , HUAC forced hundreds of people who worked in the movie industry to renounce left-wing political beliefs and testify against one another. More than 500 people lost their jobs. Many of these “blacklisted” writers, directors, actors and others were unable to work again for more than a decade. HUAC also accused State Department workers of engaging in subversive activities. Soon, other anticommunist politicians, most notably Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957), expanded this probe to include anyone who worked in the federal government.

Thousands of federal employees were investigated, fired and even prosecuted. As this anticommunist hysteria spread throughout the 1950s, liberal college professors lost their jobs, people were asked to testify against colleagues and “loyalty oaths” became commonplace.

The Cold War Abroad

The fight against subversion at home mirrored a growing concern with the Soviet threat abroad. In June 1950, the first military action of the Cold War began when the Soviet-backed North Korean People’s Army invaded its pro-Western neighbor to the south. Many American officials feared this was the first step in a communist campaign to take over the world and deemed that nonintervention was not an option. Truman sent the American military into Korea, but the Korean War dragged to a stalemate and ended in 1953.

In 1955, the United States and other members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) made West Germany a member of NATO and permitted it to remilitarize. The Soviets responded with the Warsaw Pact , a mutual defense organization between the Soviet Union, Albania, Poland, Romania, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria that set up a unified military command under Marshal Ivan S. Konev of the Soviet Union.

Other international disputes followed. In the early 1960s, President Kennedy faced a number of troubling situations in his own hemisphere. The Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and the Cuban missile crisis the following year seemed to prove that the real communist threat now lay in the unstable, postcolonial “Third World.”

Nowhere was this more apparent than in Vietnam , where the collapse of the French colonial regime had led to a struggle between the American-backed nationalist Ngo Dinh Diem in the south and the communist nationalist Ho Chi Minh in the north. Since the 1950s, the United States had been committed to the survival of an anticommunist government in the region, and by the early 1960s it seemed clear to American leaders that if they were to successfully “contain” communist expansionism there, they would have to intervene more actively on Diem’s behalf. However, what was intended to be a brief military action spiraled into a 10-year conflict .

The End of the Cold War and Effects

Almost as soon as he took office, President Richard Nixon (1913-1994) began to implement a new approach to international relations. Instead of viewing the world as a hostile, “bi-polar” place, he suggested, why not use diplomacy instead of military action to create more poles? To that end, he encouraged the United Nations to recognize the communist Chinese government and, after a trip there in 1972, began to establish diplomatic relations with Beijing.

At the same time, he adopted a policy of “détente”—”relaxation”—toward the Soviet Union. In 1972, he and Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev (1906-1982) signed the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I), which prohibited the manufacture of nuclear missiles by both sides and took a step toward reducing the decades-old threat of nuclear war.

Despite Nixon’s efforts, the Cold War heated up again under President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004). Like many leaders of his generation, Reagan believed that the spread of communism anywhere threatened freedom everywhere. As a result, he worked to provide financial and military aid to anticommunist governments and insurgencies around the world. This policy, particularly as it was applied in the developing world in places like Grenada and El Salvador, was known as the Reagan Doctrine .

Even as Reagan fought communism in Central America, however, the Soviet Union was disintegrating. In response to severe economic problems and growing political ferment in the USSR, Premier Mikhail Gorbachev (1931-2022) took office in 1985 and introduced two policies that redefined Russia’s relationship to the rest of the world: “glasnost,” or political openness, and “ perestroika ,” or economic reform.

Soviet influence in Eastern Europe waned. In 1989, every other communist state in the region replaced its government with a noncommunist one. In November of that year, the Berlin Wall –the most visible symbol of the decades-long Cold War–was finally destroyed, just over two years after Reagan had challenged the Soviet premier in a speech at Brandenburg Gate in Berlin: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” By 1991, the Soviet Union itself had fallen apart. The Cold War was over.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The Cambridge History of Communism

- > Communist Propaganda and Media in the Era of the Cold War

Book contents

- The Cambridge History of Communism

- Endgames? Late Communism in Global Perspective, 1968 to the Present

- Copyright page

- Contributors to Volume III

- Introduction to Volume III

- Part I Globalism and Crisis

- Part II Everyday Socialism and Lived Experiences

- 11 The Aging Pioneer: Late Soviet Socialist Society, Its Challenges and Challengers

- 12 Communism and Religion

- 13 Visualizing the Socialist Public Sphere

- 14 Communist Propaganda and Media in the Era of the Cold War

- 15 The Zones of Late Socialist Literature

- 16 Feminism, Communism and Global Socialism: Encounters and Entanglements

- 17 The Communist and Postsocialist Gender Order in Russia and China

- Part III Transformations and Legacies

- Plate Section

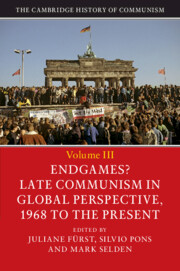

14 - Communist Propaganda and Media in the Era of the Cold War

from Part II - Everyday Socialism and Lived Experiences

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 September 2017

Access options

Bibliographical essay, save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Communist Propaganda and Media in the Era of the Cold War

- By Stephen Lovell

- Edited by Juliane Fürst , University of Bristol , Silvio Pons , Università degli Studi di Roma 'Tor Vergata' , Mark Selden , Cornell University, New York

- Book: The Cambridge History of Communism

- Online publication: 28 September 2017

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

This website uses cookies

We place some essential cookies on your device to make this website work. We'd like to use additional cookies to remember your settings and understand how you use our services. This information will help us make improvements to the website.

Cold War on File

Why did the cold war emerge, teachers' notes, introduction, external links.

About this classroom resource

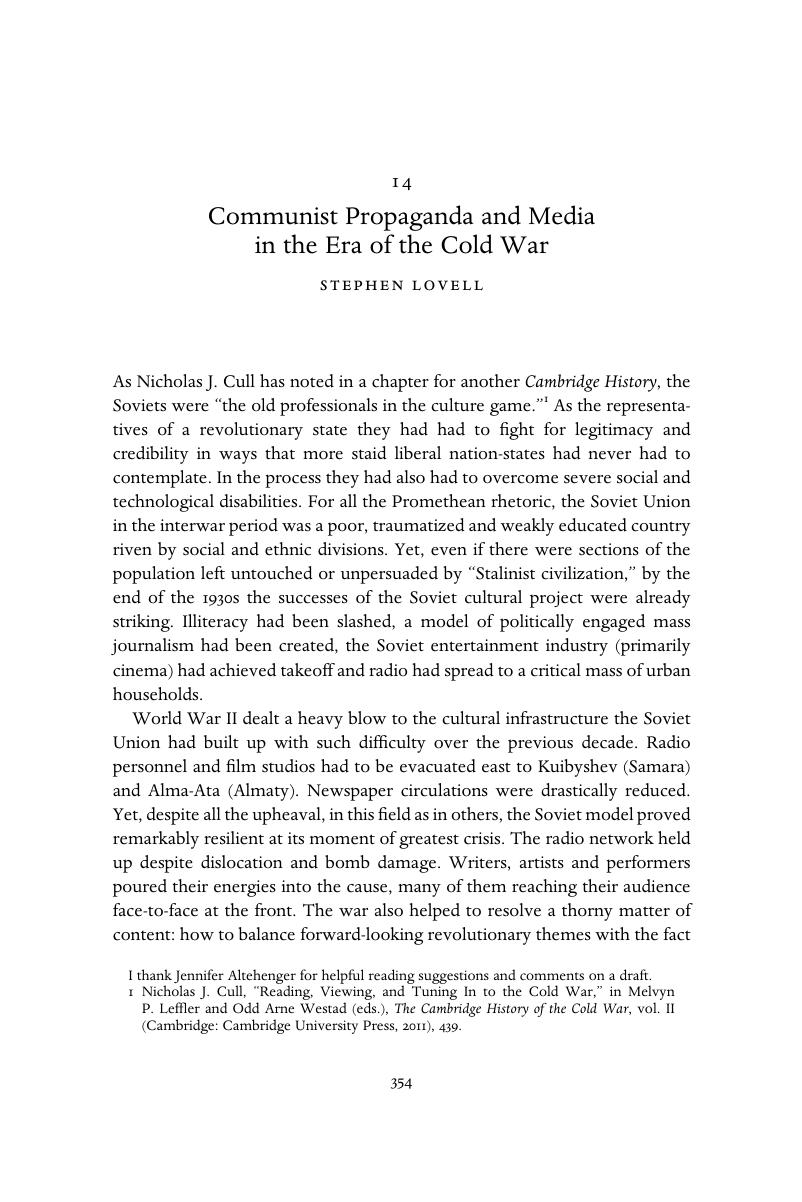

The majority of the sources in this themed collection have been taken from our Cold War web resource with which many users of the Education Website will be familiar. However, we have upgraded the quality of the images, shown more of the original document in some cases and included additional sources from The National Archives exhibition: Britain’s Cold War revealed: Protect and Survive, April-November 2019.

The purpose of this document collection is to allow students and teachers to develop their own questions and lines of historical enquiry on the Cold War. Students could work with a group of sources or single source on a certain aspect. Teachers may wish to use the collection to develop their own resources or encourage students to ‘curate’ their own ‘exhibition’ of the most significant sources on the topic. Another idea would be to challenge students to use the documents to substantiate or dispute points made in the introduction with this collection. We hope that the documents will offer students a chance to develop their powers of evaluation and analysis and enrich their understanding of this topic.

Alternatively, teachers could use the Cold War website alongside this collection for specific questions or activities connected to these documents.

Students will find more documents in our recommended resources and can also consider film sources as interpretations of these events in relation to the documents by following the links to British Public Information films and British Pathé.

Themes covered in this collection include:

How strong was the wartime alliance, 1941-45?

The records provided here give context for a study of the Cold War, with reference to the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences which bridge the period of wartime co-operation and the post war tensions that followed.

Who caused the Cold War?

The attitudes and responses of important individuals in the early stages of the Cold War – Stalin, Truman and Churchill are explored through various cabinet discussions and foreign office reports.

How did the Cold War work?

Documents for this theme highlight the nature of the Cold War including the conflict over Berlin in 1948, the blockade and airlift. Other sources reflect the conflict in Korea and Soviet actions in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968) as told through political, military or personal themes.

How close was world nuclear war in the 1950s and 1960s?

Records included in the collection relate to the development of nuclear weapons, British defence policy and the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962.

Britain in the nuclear age

For this theme we have included some documents featured in our exhibition called Britain’s Cold War revealed: Protect and Survive which concern civil defence, protests against the bomb at Aldermaston and Greenham Common.

Connections to the Curriculum

These documents can be used to support any of the exam board specifications covering the Cold War, such as:

AQA: GCE History Unit 2R: The Cold War, c1945-1991

OCR: GCE History Unit Y113: Britain 1930-1997: British Period Study: Britain’s position in the world 1951-1997 (Enquiry topic: Churchill 1930-1951) Unit Y223: Non-British Period Study: The Cold War in Europe, 1941-1995

Edexcel: GCE History Paper 3, Option 37.1: The changing nature of warfare, 1859–1991: perception and reality

Edexcel: GCSE History Period Study 4: Superpower relations and the Cold War, 1941–91

AQA: GCSE History BC Conflict and tension between East and West, 1945–1972

Who first coined the phrase “Cold War”? The general consensus among historians is that it was the celebrated author and journalist, George Orwell, in his essay ‘You and the Atom Bomb’ published in the Tribune magazine on 19 October 1945 (though one biographer has traced his use of the phrase back to 1943). In the 1945 article Orwell reflected on the repercussions of ‘a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of “Cold War” with its neighbours’. He envisaged ‘the prospect of two or three monstrous super-states’ dominating the world, and possessing weapons which can kill millions in seconds. Orwell concluded that the atomic bomb was likely ‘to put an end to large-scale wars at the cost of prolonging indefinitely a “peace that is no peace”.

Seeing into the future

Looking back at Orwell’s predictions, he possessed amazing foresight. The Cold War (1945-1991) was a confrontation, both military and ideological, between two superpowers, the capitalist United States and the communist Soviet Union (and their respective allies), made all the more tense by the threat of nuclear war. This highly charged stand-off was a thread running through historic developments such as the iron curtain, the Cuban missile crisis and the construction and dismantling of the Berlin Wall.

Because there was so much at stake – arguably, the very future of civilisation – the superpowers avoided direct confrontation but fought a series of savage proxy wars, in Asia, Africa and Latin America, supporting local factions. Orwell’s “peace that is no peace” prediction was borne out.

Revelations

Contemplating the Cold War from today’s perspective, one aspect cannot be predicted – the surprises that can emerge from documents you haven’t seen before. Many narratives are available for the Cold War: it is the subject of many books, documentaries and films. However, this package of documents from The National Archives shows us that archives still have the capacity to surprise us about this period in history. There are many instances of this. For example, it is well-known that Churchill’s famous quotation “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent” was part of a speech given in Fulton, Missouri, USA, on 5 March 1946. But did you know that he used the phrase ‘iron curtain’ almost a year earlier, in a personal telegram to President Truman on 12 May 1945? This is a heartfelt message in which Churchill expresses his ‘deep anxiety’ about Russian intentions in Eastern Europe.

Another surprise is a report by the Joint Planning Staff which puts forward a plan, (little known today) entitled ‘Operation Unthinkable’, advocating an attack on Soviet Forces in order to push them out of East Germany and Poland in July 1945. This document has real ‘shock value’: ‘If they [the Russians] want total war, they are in a position to have it’. The strident language of this document is striking: the intention was ‘to impose on Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire’. However, it is acknowledged that ‘to win would take us a very long time’.

Dramatic language is also a feature of a report called ‘The Threat to Western Civilisation’ from the Foreign Secretary to the British Cabinet in March 1948. This refers to the possibilities of the Soviet Union establishing a ‘world dictatorship’ or the ‘collapse of organised society over great stretches of the globe’. The writing style is so powerful, the words leap from the page. Yet another example of vivid writing can be seen in a Foreign Office telegram reporting back to London about the uprising in Hungary on 25 October 1956: ‘the populace are terrified of massive reprisals’.

In some cases, document content is not dramatic in itself but is, none the less, surprising. A great example of this is the last paragraph of Atomic Spy Klaus Fuch’s confession on 27 January 1950, when he suddenly begins to ‘wax lyrical’ about his admiration for English people: ‘since coming to Harwell I have met English people of all kinds, and I have come to see in many of them a deep rooted firmness which enables them to lead a decent way of life. I do not know where this springs from and I don’t think they do, but it is there’. This incongruous piece of reflectiveness at the end of a confession statement shows how Fuchs was somewhat detached from reality at the time he made it – the does not seem to realise the import of what he had just confessed to, the giving of vital atomic secrets to the Soviet Union.

As well as the textual documents, visual sources can also tell a powerful story. Grainy black and white photographs of the early days of the construction of the Berlin Wall make us reflect on the predicament of Berliners, looking on at the partially constructed wall, the barbed wire, the turrets, and the ‘death strip’. For another striking example of visual material, see the illustrations in the leaflet advising householders on protection against nuclear attack (1963), which are strangely cosy, hinting at elements of normality even during fall-out conditions.

Value of archives

The National Archives is the nation’s memory – we preserve the integrity of the public records, stretching back some 1,000 years. George Orwell truly understood the value of authoritative records: Winston Smith, the anti-hero of Orwell’s 1984 , worked in the ‘Ministry of Truth’, falsifying back-numbers of The Times so that the information contained in them corresponded with the current pronouncements of Big Brother’s regime. The corollary of this imagined scenario, of course, is that archives you can trust are essential for a true understanding of the past.

Mark Dunton Principal Records Specialist The National Archives

Pathe Archive film collections covering various conflicts during the Cold War – https://www.britishpathe.com/pages/collections

Related resources

Leaders and controversies, cabinet papers, fifties britain, public information films.

The Role of the Media During the Cold War

This essay will serve as an introduction into the media’s role during the Cold War. It will evidence how the media on both sides of the ideological division sort to produce, contribute and maintain political and cultural antagonism. The essay will also evidence how the main method of this was the development and distribution of political propaganda, both domestically and internationally. A Cold War proxy conflict and the involvement of the media will also be presented so as to offer a more detailed exploration of the media’s behaviour. To begin, there will be a brief exploration of the historical context of the media followed by a detailed presentation of its actions.

To examine the media’s role in the production, contribution and maintenance of Cold War antagonism, it is important to first examine the media in the correct historical context. During this time, the media predominantly consisted of, print, film, radio, and TV. This was prior to the popularity of decentralised media institutions such as electronic social media. This is worthy of note because as broadcasting requires large amounts of funding; centralised media is extremely susceptible to state control (Bernhard, 1999).

The Cold War is accepted to have lasted from 1947 to 1991. During this time, the media’s predominant medium of communication evolved from radio and print into television. This change was accompanied along with the role of the media from a ‘mouthpiece’ of the state, to a more, prima facie, independent sector. The media’s role in the production, contribution and maintenance of Cold War antagonism cannot be understated. When American aspirations for European capitalism seemed threatened; media in both blocs jumped into action. While the actions of the state-owned Soviet media would not be expected to take a watchdog approach, what may have been surprising was the extent to which the western media took a mouthpiece position (Carruthers, 2011).

The allegiance that the majority of the media took to government policy and the politicisation of its content began almost immediately with the start of the Cold War. This is evident with the early Cold War television reports often being scripted and sometimes produced by the defence establishment (Bernhard, 1999). This development of the media accepting governmental influence was essential to the production of public support for state actions. The initial role the media took was to motivate the post-WW2 populace into reaffirming and defending their national political and economic allegiances. While the private-owned Western media was obliging in the defence of Western economic and military interests, the state-censored soviet media was just as ready to defend theirs. All media succeeded in the production of public support for their government’s actions against the foreign enemy. The Western Allied governments and the Soviet Union could never have produced or maintained sufficient public support and jingoism for the long conflict without the media’s contribution (Doherty, 2003).

At the start of the conflict, media coverage of the Cold War between America, its allies and the Soviet Union served to escalate domestic fear of imminent destruction. “The Red Scare” campaigns of the Western media were presented on every applicable media source. The use of print with easily de-codable and emotive images helped to redefine national identity as a virtuous and patriotic America, against a dangerous and destructive socialist east. The media distributed extreme propagandist slogans such as “Better Dead than Red!” This type of politicised propaganda served to cause hysteria over communism and nuclear war (Bernhard, 1999). It worked to subdue any domestic sympathy for the enemy or resistance to the conflict that usually occurs during war. It was a calculated action to maintain public antagonism towards the enemy and rejection of their political and economic policies. The media extended the propaganda to every aspect of western life, from radio, film, television and print to even schools. The film “Red Nightmare” was taught as part of the standard curriculum and is evidence of the media providing state-sanctioned indoctrination of the populace. This act of media manipulation to create mass fear and paranoia cannot be undervalued, it was the conscious effort of the powerful to marginalise unpopular opinion and spread the dominate agenda. It also assisted in the solidification and polarisation of cultural differences and reinforced political ideology (Mikkonen, 2010).

Media pollicisation and propaganda techniques were also used as a direct tool against the enemy. There was a direct contribution of the media to the war effort which saw the media engaging in antagonistic psychological warfare. This was achieved by dissembling propaganda into the Soviet Union via the radio, as an attempt to spread pro-capitalist sentiment into the soviet population and create a more pro-Western culture. The Soviet media also used the medium of radio within its own states and other countries as a form of transnational propaganda. Because the Soviet media was state-censored; it sought to legitimise its appearance by camouflaging its production origins. The USSR had many “international” radio stations that were indeed located in the Soviet Republic. These actions of the media show the progression from a seemingly more passive producer of public support and political compliance, to an active tool of the war itself (Chisem, 2012). The media on both sides of the divide were responsible for the production of public opinion, the contribution of propaganda, and maintenance of antagonism via psychological warfare. However, many western media outlets, such as voice America, BBC, and, Vatican Radio, sought a different approach. While maintaining political loyalty to their nation states, there governmental brief was to project the positive aspects of their nations into the Soviet Union. This was a form of gentle, yet cohesive, diplomacy (Chisem,2012). It sought to counteract Soviet propaganda by subversively offering a positive view of the perceived enemy. While doing this, the Western media soon realised the relevance of the fact that the Soviet Union was not a homogeneous society. The colonial empire consisted of many nationalities, such as Ukrainians and those from the Baltic States. By tailoring radio announcements to individual minorities, the West was able to construct a long-term strategy of disrupting territorial integrity. This was profoundly antagonistic to the Soviet state, which feared the growth of domestic separatists (Chisem, 2012).

The media of the Cold War era can even be accredited with the marketing of the conflict. It was American journalist Walter Lippmann who entitled the conflict as a ‘Cold War’ due to the lack of direct military warfare (Slaughter, 2012). However, the lack of military conflict was only absent between the UUSR and America. Because of the mutually assured destruction (M.A.D) of the two nuclear powers; the Soviet Union and the West only engaged in proxy wars with satellite states. One such example is the Vietnam War of 1955-1975. The U.S. government viewed involvement in the war as an essential preventative measure to halt the communist takeover of South Vietnam. This was part of the West’s strategy of Communism containment.

The Vietnam War was termed as the first ‘TV war’ by Michael Arlen (Slaughter, 2012). This was due to the media coverage of the conflict now becoming exceedingly reported through television. It was also accompanied with strong and emotive pictures, such as the Pulitzer Prize winner ‘Vietnam Napalm’ (Bernhard, 1999). The television coverage of the conflict was relentless and lasted for several years. While news coverage at the beginning of the conflict was often scripted and pro-Western, this reporting was not. The media had unfettered access to the conflict and took more independence in their reporting. Accordingly, the public reaction to constant exposure of war brutality also changed. The Western media moved away from its position as a governmental mouthpiece, and began to adopt a more watchdog approach (Carruthers, 2011). It was this change, combined with the graphic reporting of the war, which has since been accredited with the thwarting of American victory. The media’s role is seen to have stoked domestic anti-war sentiments in the American public by presenting them with the atrocities of war into their own living rooms. This occurrence shows a decline of the media’s role in maintaining antagonism and public support for conflict (Mikkonen, 2010).

The most obvious and crucial act of the media, which eroded the public antagonism towards the Soviet Union and support towards the conflict, was the publishing of the Pentagon Papers. Several newspapers, including the The New York Times and the Washington Post, printed extracts of the governmental documents which were classified as top secret (Urban, 1997). These papers revealed a deliberate government distortion of previously reported statistics that had been perceived as undesirable. The distortion concerned the numbers of causalities and successful operations, which were significantly worse than previously stated. The media now evidenced to the people how the government had misled them concerning the facts of war. What the media did here was reposition themselves as the only reliable information distributer and eroded confidence in the government. Subsequently, domestic reaction to this Cold War proxy conflict changed. Domestic and international anti-war movements grew, and the media was responsible. This saw the mass rejection of ‘McCarthyism’; the accusation of disloyalty to the country for opposing the war which had worked before to marginalise dissent (Doherty, 2003).

What it is now evident is that throughout the Cold War, the media played a central role in the production and maintenance of antagonism between both sides of the conflict. Both the Soviet and Western media outlets denatured each other as inferior and maintained “us and them” rhetoric. Dominant views were enforced and detractors were marginalised. The media produced virtuous national identities to legitimise themselves and denounce their enemies. (DOHERTY,(2003) A substantial contribution of the media to the maintenance of Cold War antagonism was the creation of a prolonged state of fear. Sensational propaganda and politicised reporting developed a societal fear of imminent destruction and severe paranoia. This assisted the government in the harvesting of a supportive population. The media also worked as a direct tool of the conflict by communicating to the population of the Soviet Union. This in itself was an extremely antagonistic action that worked very well as a soft power method of the west (Bernhard, 1999).

When the media changed to an increasingly watchdog position of reporting, some of the antagonism that it had produced against the Soviet Union became directed at the national government. In all, the media was the Cold War’s protagonist in cultivating and maintaining antagonism within the bipolar divide. It achieved this with sensational reporting, and exploitation of cultural divides, the maintenance of societal fear and the production of propaganda. It’s most explicit and direct contribution to Cold War antagonism was the production of a subversive communication strategy with the enemy’s populace.

Bibliography

Bernhard, N. (1999) ‘ U.S Television News and Cold War Propaganda, 1947-1960’. Cambridge: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Carruthers, Susan L. (2011) ‘Total War’. (2nd edition) Houndmills: Palgrave