- Privacy Policy

Home » Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Artistic Research

Definition:

Artistic Research is a mode of inquiry that combines artistic practice and research methodologies to generate new insights and knowledge. It involves using artistic practice as a means of investigation and experimentation, while applying rigorous research methods to examine and reflect upon the process and outcomes of the artistic practice.

Types of Artistic Research

Types of Artistic Research are as follows:

Practice-based Research

This type of research involves the creation of new artistic works as part of the research process. The focus is on the exploration of artistic techniques, processes, and materials, and how they contribute to the creation of new knowledge.

Research-led practice

This type of research involves the use of academic research methods to inform and guide the creative process. The aim is to investigate and test new ideas and approaches to artistic practice.

Practice-led Research

This type of research involves using artistic practice as a means of exploring research questions. The aim is to develop new insights and understandings through the creative process.

Transdisciplinary Research

This type of research involves collaboration between artists and researchers from different disciplines. The aim is to combine knowledge and expertise from different fields to create new insights and perspectives.

Research Through Performance

This type of research involves the use of live performance as a means of investigating research questions. The aim is to explore the relationship between the performer and the audience, and how this relationship can be used to create new knowledge.

Participatory Research

This type of research involves collaboration with communities and stakeholders to explore research questions. The aim is to involve participants in the research process and to create new knowledge through shared experiences and perspectives.

Data Collection Methods

Artistic research data collection methods vary depending on the type of research being conducted and the artistic discipline being studied. Here are some common methods of data collection used in artistic research:

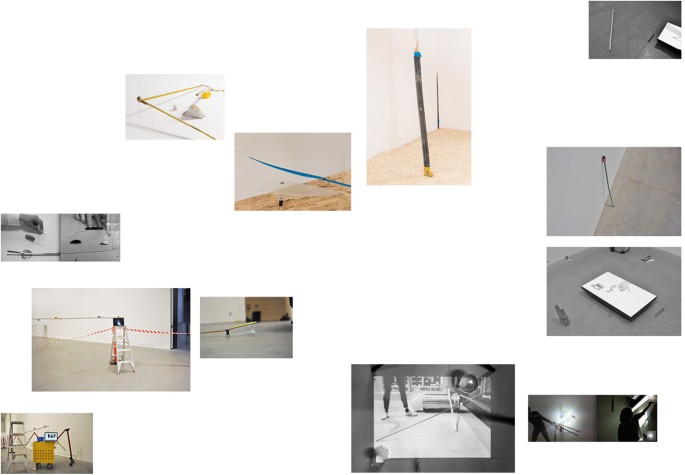

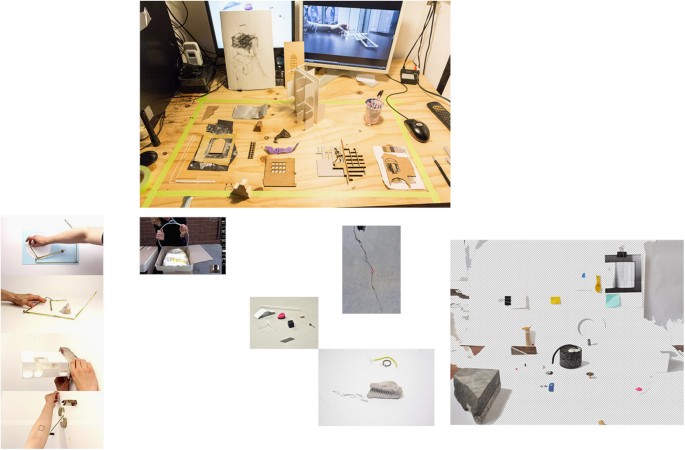

- Artistic production: One of the most common methods of data collection in artistic research is the creation of new artistic works. This involves using the artistic practice itself as a method of data collection. Artists may create new works of art, performances, or installations to explore research questions and generate data.

- Interviews : Artists may conduct interviews with other artists, scholars, or experts in their field to collect data. These interviews may be recorded and transcribed for further analysis.

- Surveys and questionnaires : Surveys and questionnaires can be used to collect data from a larger sample of people. These can be used to collect information about audience reactions to artistic works, or to collect demographic information about artists.

- Observation: Artists may also use observation as a method of data collection. This can involve observing the audience’s reactions to a performance or installation, or observing the process of artistic creation.

- Archival research : Artists may conduct archival research to collect data from historical sources. This can involve studying the work of other artists, analyzing historical documents or artifacts, or studying the history of a particular artistic practice or discipline.

- Experimental methods : In some cases, artists may use experimental methods to collect data. This can involve manipulating variables in an artistic work or performance to test hypotheses and generate data.

Data Analysis Methods

some common methods of data analysis used in artistic research:

- Interpretative analysis : This involves a close reading and interpretation of the artistic work, performance or installation in order to understand its meanings, themes, and symbolic content. This method of analysis is often used in qualitative research.

- Content analysis: This involves a systematic analysis of the content of artistic works or performances, with the aim of identifying patterns, themes, and trends in the data. This method of analysis is often used in quantitative research.

- Discourse analysis : This involves an analysis of the language and social contexts in which artistic works are created and received. It is often used to explore the power dynamics, social structures, and cultural norms that shape artistic practice.

- Visual analysis: This involves an analysis of the visual elements of artistic works, such as composition, color, and form, in order to understand their meanings and significance.

- Statistical analysis: This involves the use of statistical techniques to analyze quantitative data collected through surveys, questionnaires, or experimental methods. This can involve calculating correlations, regression analyses, or other statistical measures to identify patterns in the data.

- Comparative analysis: This involves comparing the data collected from different artistic works, performances or installations, or comparing the data collected from artistic research to data collected from other sources.

Artistic Research Methodology

Artistic research methodology refers to the approach or framework used to conduct artistic research. The methodology used in artistic research is often interdisciplinary and may include a combination of methods from the arts, humanities, and social sciences. Here are some common elements of artistic research methodology:

- Research question : Artistic research begins with a research question or problem to be explored. This question guides the research process and helps to focus the investigation.

- Contextualization: Artistic research often involves an examination of the social, historical, and cultural contexts in which the artistic work is produced and received. This contextualization helps to situate the work within a larger framework and to identify its significance.

- Reflexivity: Artistic research often involves a high degree of reflexivity, with the researcher reflecting on their own positionality and the ways in which their own biases and assumptions may impact the research process.

- Iterative process : Artistic research is often an iterative process, with the researcher revising and refining their research question and methods as they collect and analyze data.

- Creative practice: Artistic research often involves the use of creative practice as a means of generating data and exploring research questions. This can involve the creation of new works of art, performances, or installations.

- Collaboration: Artistic research often involves collaboration with other artists, scholars, or experts in the field. This collaboration can help to generate new insights and perspectives, and to bring diverse knowledge and expertise to the research process.

Examples of Artistic Research

There are numerous examples of artistic research across a variety of artistic disciplines. Here are a few examples:

- Music : A composer may conduct artistic research by exploring new musical forms and techniques, and testing them through the creation of new works of music. For example, composer Steve Reich conducted artistic research by studying traditional African drumming techniques and incorporating them into his minimalist compositions.

- Visual art: An artist may conduct artistic research by exploring the history and techniques of a particular medium, such as painting or sculpture, and using that knowledge to create new works of art. For example, painter Gerhard Richter conducted artistic research by exploring the history of photography and using photographic techniques to create his abstract paintings.

- Dance : A choreographer may conduct artistic research by exploring new movement styles and techniques, and testing them through the creation of new dance works. For example, choreographer William Forsythe conducted artistic research by studying the physics of movement and incorporating that knowledge into his choreography.

- Theater : A theater artist may conduct artistic research by exploring the history and techniques of a particular theatrical style, such as physical theater or experimental theater, and using that knowledge to create new works of theater. For example, director Anne Bogart conducted artistic research by studying the teachings of the philosopher Jacques Derrida and incorporating those ideas into her approach to theater.

- Film : A filmmaker may conduct artistic research by exploring the history and techniques of a particular genre or film style, and using that knowledge to create new works of film. For example, filmmaker Agnès Varda conducted artistic research by exploring the feminist movement and incorporating feminist ideas into her films.

When to use Artistic Research

some situations where artistic research may be useful:

- Developing new artistic works: Artistic research can be used to inform and inspire the development of new works of art, music, dance, theater, or film.

- Exploring new artistic techniques or approaches : Artistic research can be used to explore new techniques or approaches to artistic practice, and to test and refine these approaches through creative experimentation.

- Investigating the historical and cultural contexts of artistic practice: Artistic research can be used to investigate the social, cultural, and historical contexts of artistic practice, and to identify the ways in which these contexts shape and influence artistic works.

- Evaluating the impact and significance of artistic works : Artistic research can be used to evaluate the impact and significance of artistic works, and to identify the ways in which they contribute to broader cultural, social, and political issues.

- Advancing knowledge and understanding in artistic fields: Artistic research can be used to advance knowledge and understanding in artistic fields, and to generate new insights and perspectives on artistic practice.

Purpose of Artistic Research

The purpose of artistic research is to generate new knowledge and understanding through a rigorous and creative investigation of artistic practice. Artistic research aims to push the boundaries of artistic practice and to create new insights and perspectives on artistic works and processes.

Artistic research serves several purposes, including:

- Advancing knowledge and understanding in artistic fields: Artistic research can contribute to the development of new knowledge and understanding in artistic fields, and can help to advance the study of artistic practice.

- Creating new artistic works and forms: Artistic research can inspire the creation of new artistic works and forms, and can help artists to develop new techniques and approaches to their practice.

- Evaluating the impact and significance of artistic works: Artistic research can help to evaluate the impact and significance of artistic works, and to identify their contributions to broader cultural, social, and political issues.

- Enhancing interdisciplinary collaboration: Artistic research often involves interdisciplinary collaboration, and can help to foster new connections and collaborations between artists, scholars, and experts in diverse fields.

- Challenging assumptions and pushing boundaries: Artistic research can challenge assumptions and push the boundaries of artistic practice, and can help to create new possibilities for artistic expression and exploration.

Characteristics of Artistic Research

Some key characteristics that can be used to describe artistic research:

- Creative and interdisciplinary: Artistic research is creative and interdisciplinary, drawing on a wide range of artistic and scholarly disciplines to explore new ideas and approaches to artistic practice.

- Experimental and process-oriented : Artistic research is often experimental and process-oriented, involving creative experimentation and exploration of new techniques, forms, and ideas.

- Reflection and critical analysis : Artistic research involves reflection and critical analysis of artistic practice, with a focus on exploring the underlying processes, assumptions, and concepts that shape artistic works.

- Emphasis on practice-led inquiry : Artistic research is often practice-led, meaning that it involves a close integration of creative practice and research inquiry.

- Collaborative and participatory: Artistic research often involves collaboration and participation, with artists, scholars, and experts from diverse fields working together to explore new ideas and approaches to artistic practice.

- Contextual and socially engaged : Artistic research is contextual and socially engaged, exploring the ways in which artistic practice is shaped by broader social, cultural, and historical contexts, and engaging with issues of social and political relevance.

Advantages of Artistic Research

Artistic research offers several advantages, including:

- Innovation : Artistic research encourages creative experimentation and exploration of new techniques and approaches to artistic practice, leading to innovative and original works of art.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Artistic research often involves collaboration between artists, scholars, and experts from diverse fields, fostering interdisciplinary exchange and the development of new perspectives and ideas.

- Practice-led inquiry : Artistic research is often practice-led, meaning that it involves a close integration of creative practice and research inquiry, leading to a deeper understanding of the creative process and the ways in which it shapes artistic works.

- Critical reflection: Artistic research involves critical reflection on artistic practice, encouraging artists to question assumptions and challenge existing norms, leading to new insights and perspectives on artistic works.

- Engagement with broader issues : Artistic research is contextual and socially engaged, exploring the ways in which artistic practice is shaped by broader social, cultural, and historical contexts, and engaging with issues of social and political relevance.

- Contribution to knowledge : Artistic research contributes to the development of new knowledge and understanding in artistic fields, and can help to advance the study of artistic practice.

Limitations of Artistic Research

Artistic research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Artistic research is subjective, meaning that it is based on the individual perspectives, experiences, and creative decisions of the artist, which can limit the generalizability and replicability of the research.

- Lack of formal methodology : Artistic research often lacks a formal methodology, making it difficult to compare or evaluate different research projects and limiting the reproducibility of results.

- Difficulty in measuring outcomes: Artistic research can be difficult to measure and evaluate, as the outcomes are often qualitative and subjective in nature, making it challenging to assess the impact or significance of the research.

- Limited funding: Artistic research may face challenges in securing funding, as it is still a relatively new and emerging field, and may not fit within traditional funding structures.

- Ethical considerations: Artistic research may raise ethical considerations related to issues such as representation, consent, and the use of human subjects, particularly when working with sensitive or controversial topics.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Scientific Research – Types, Purpose and Guide

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Documentary Research – Types, Methods and...

What is artistic research?

Art offers a premise and an aim for research: a motive, a terrain, a context and a whole range of methods.

Published 10.3.2020 | Updated 30.11.2020

Art and research are basic concepts in our culture. They feed on one another and are intertwined in many ways.

Research that defines art as its object in one way or another is generally called art research. Art can, however, also offer a premise and an aim for research: a motive, a terrain, a context and a whole range of methods. This kind of research is often referred to as “artistic research”. It is not a counter concept of “scientific research”, but instead, its primary aim is to describe the framework of research in a way that does not simply reduce art to the subject matter of a study.

Artistic research is typically carried out by experts in various fields of art, i.e. artists – or artist-researchers, to be exact, because not all art is research. Artistic activities can be considered research only when they are done within a critical community.

Similar to a scientific community, an art community defines, shapes and renews the criteria for its own research frameworks and practices in interaction with the surrounding society. In this sense, artistic research is comparable to scientific research and constitutes its own form of research among various other forms.

We have endorsed The Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research .

Our most central networks within artistic research:

- European Artistic Research Network EARN

- The Society for Artistic Research SAR

- JAR on FACEBOOK

The Journal for Artistic Research (JAR) is an international, online, Open Access and peer-reviewed journal that disseminates artistic research from all disciplines. JAR’s website consists of the Journal and its Network.

Current issue

Table of contents.

Network activity

The ‘True Truths’ in the Research of Artists Janet Toro and Voluspa Jarpa

Artistic research: between transformative material and cognitive dynamics

Rethinking Artistic Research: A Review of Michael Schwab’s ‘Contemporary Research’

WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN YOU DO WHAT YOU DO? the act of researching

JAR @ 14th SAR conference in Trondheim, Norway

How should I write about my work? Notes on publishing artistic research

Get in touch, questions about submissions, peer review, general enquiries, copyright concerns and for the editor-in-chief.

Please email us via the contact form on the right. Add your name and contact details and select the field most appropriate for your query from Submissions, Peer Review, General Enquiries, Copyright Concerns and Editor-in-Chief. If you are unsure which field is most relevant to your question or concern, please select General Enquiries and it will be forwarded. We will endeavour to get back to you within a week. For submissions enquiries, please allow plenty of time before the submission deadline.

News and announcements

For more information on JAR and its activities please follow us on Facebook , where we will post news, opportunities, featured expositions and texts from our Network pages.

Alternatively you can sign up for SAR newsletter and announcements service. Via this email service you can receive information on SAR events, JAR publications and other information deemed relevant by SAR.

Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Art Libraries Journal

- > Volume 47 Issue 2

- > Searching for artistic research? A study between disciplines,...

Article contents

Need for study objects, searching for artistic research, classifying art in a publication context, referencing ar as research outcome, free and open access, searching for artistic research a study between disciplines, interests, policies and systems.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 May 2022

This paper gathers interim results of a study on the accessibility of artistic research. Since no corresponding subject portal could be found, a specific data collection was started. Due to the study's background in Switzerland, the resulting DataBase for Applied, Fine and Performing Arts (AFPA-DB) focusses mostly on the German-speaking and European countries, while aiming to be expanded in the future. After summarizing the formal findings of the study, the authors explore the challenges that occurred during the research process. Their struggle in finding and/or accessing artistic research seems to be characteristic of the field and is therefore likely to affect similar projects in other academic art libraries.

The DataBase for Applied, Fine and Performing Arts (AFPA-DB) results from a growing need at art universities to provide access to artistic research (AR) as both:

a) a source and reference for research and education; and

b) in terms of publication: presenting and situating one's own research results in a larger academic environment.

While an overview of options for publishing art and design has been published as the first outcome of our research (Lurk Reference Lurk 2021 ), this text focusses on the side effects of data collection.

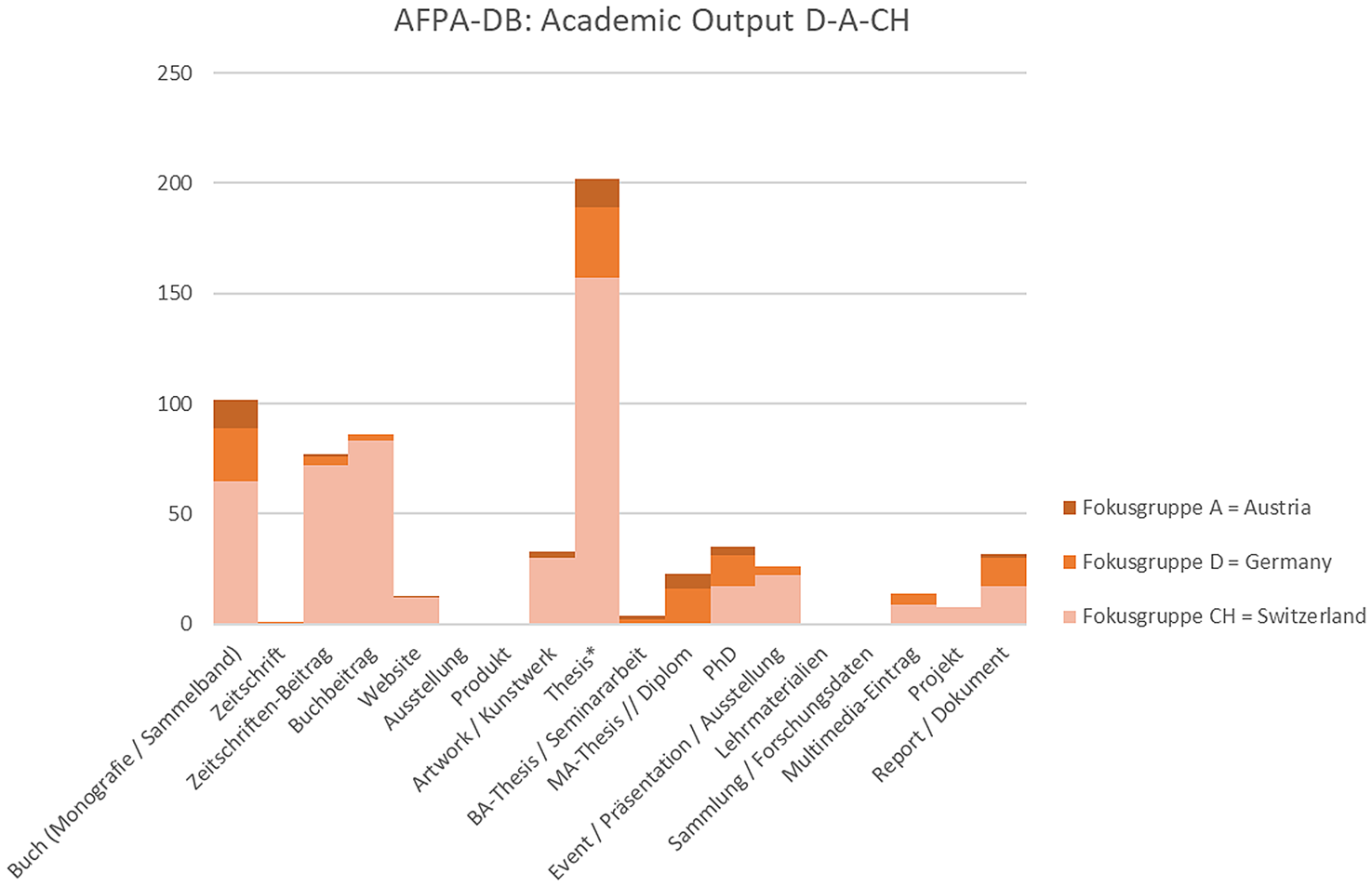

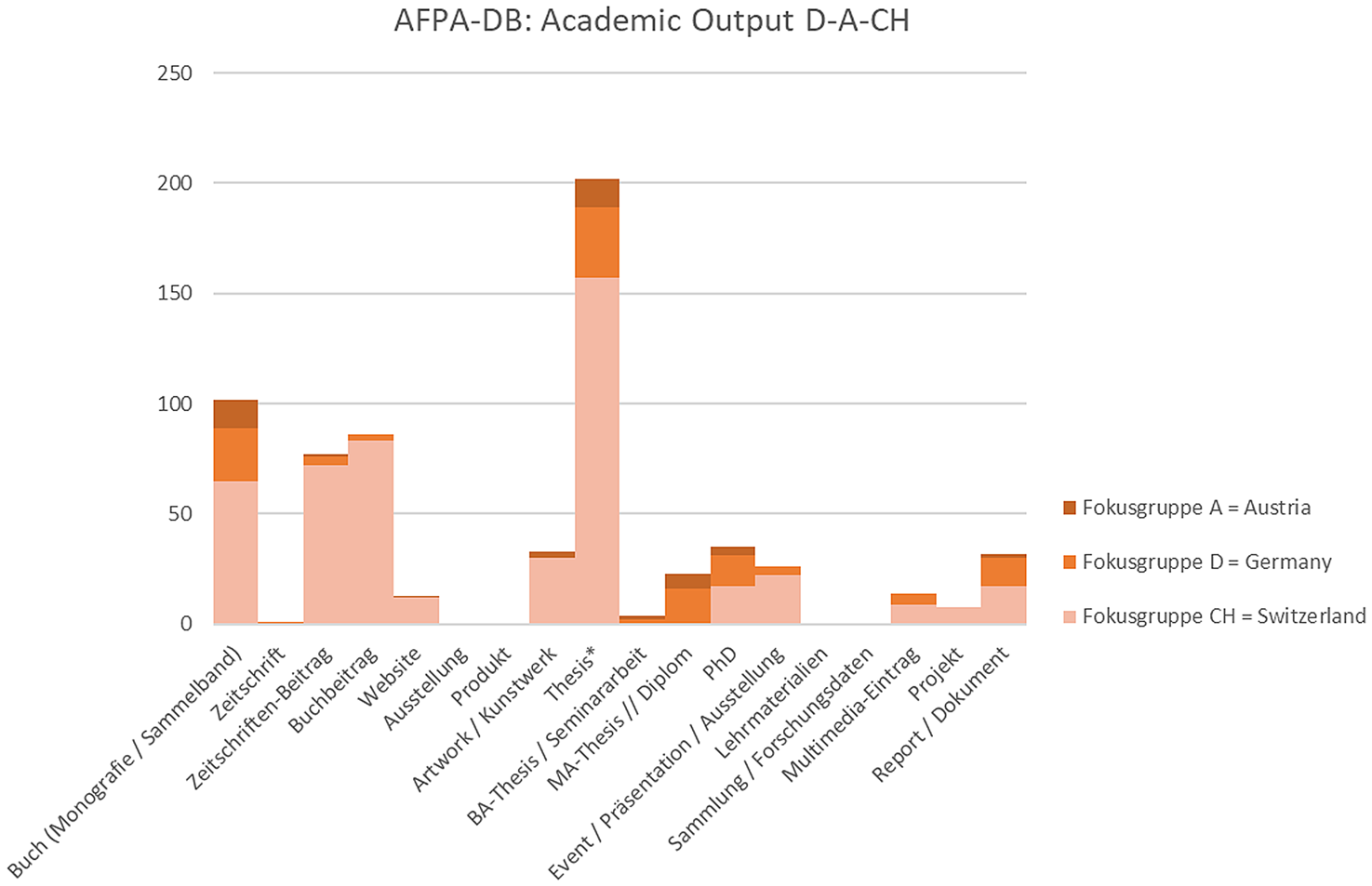

In 30 September 2021, 1035 entries from 38 international universities (including 28 of the 44 German-speaking art academies) Footnote 1 , 3 AR associations Footnote 2 , and other individual entries were indexed in the AFPA-DB. Included were 183 monographs, 112 book contributions, 243 journal articles (including 154 contributions from the Journal for Artistic Research ), 2 conference papers, 34 artworks, 7 blog posts, 32 documentaries, 2 films, 34 presentations, 22 reports, 94 student theses and dissertations (including 47 dissertations from German-language art schools), 17 video documentaries and 253 websites (including 108 entries from the international exchange programme Atelier Mondial ). Footnote 3

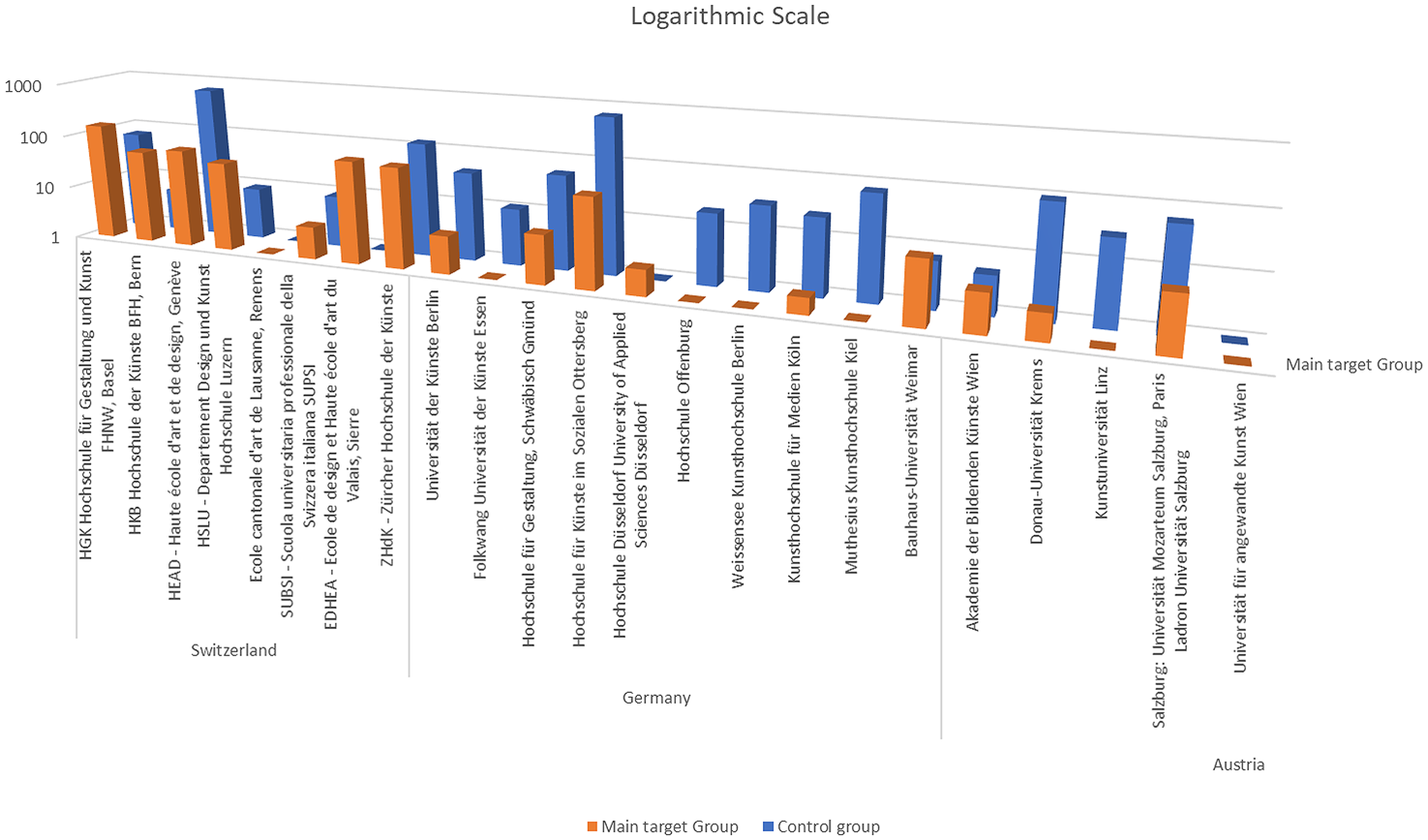

In August 2021, the AFPA-DB results from the 28 art academies in Switzerland, Austria, and Germany were analysed. Even though the results are too heterogeneous for comparisons, the collected entries were counted and listed according to document types. Furthermore, a control group was then created, in which only the results of a keyword search within the respective repositories/publication servers was counted. Beyond semantic differences, since the difference between AR outputs and AR reflection was ignored, the institutional websites were left out of the control group (but were, however, included in the AFPA-group).

The following considerations result from an analytical reflection on metadata information that was captured during the research and collection phase, focussing on: a) the location where the entry was found; b) accessibility, including copyright information; and c) keywords (or lack of keywords) used for description. After a brief outline of the motivation, the text discusses the effects of systemic weaknesses which became apparent during the research. In doing so, we look for reasons why the results of AR are so difficult to find.

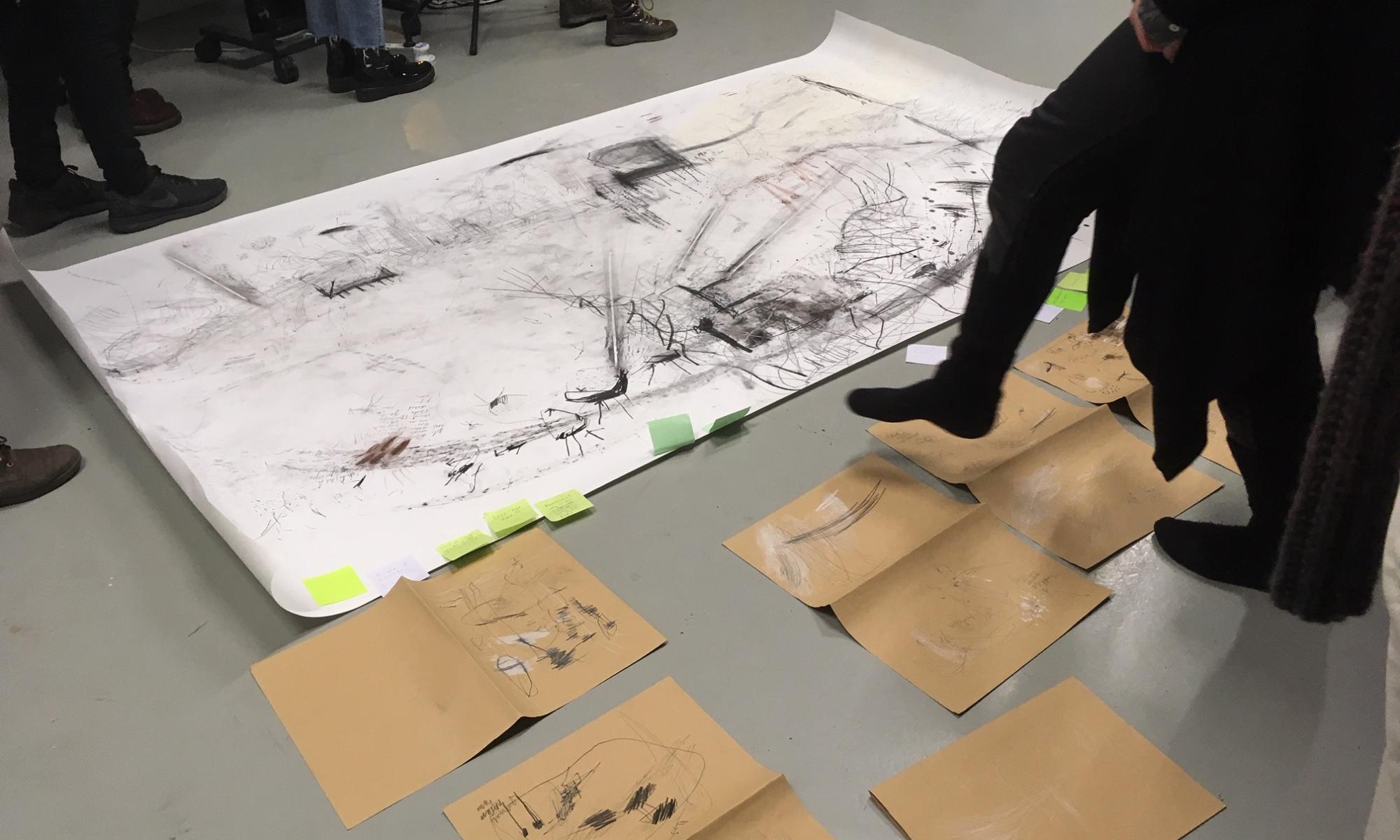

Fig. 1. Overview of the total number of entries, according to document type, sorted by country (German-speaking countries). Since educational resources and (research) data packages occurred only in the control group, the bars are empty here.

Fig. 2. Overview of the total number of entries (regardless of document type) sorted by academy/country. While the orange bars show the AFPA-DB entries, the sum of the hits of the respective control group is coloured blue.

In the specific context of art academies, artistic or creative works have always been both objects of study Footnote 4 and results Footnote 5 . Although art – at least art since the 1960s – has established its own genres of becoming public, discursive, or engaging in open dialogue with dedicated audiences, traditional scientific modes of communication, which increase especially with the research requirements of AR, still seem challenging. Thus, the artistic researcher continually discusses the “transposition” Footnote 6 between artistic modes of approaching the public within the (art-)work and publication standards in the scientific community.

For the last 20 to 30 years, AR has become a topic of scientific funding, accreditation and evaluation procedures, including discussion on publication Footnote 7 , evaluation Footnote 8 , and methodologies Footnote 9 . Concerning the performance measurement of artistic “outputs”, the Swedish model seems groundbreaking. Footnote 10 For staffing procedures, Lilja has proposed a question grid, and further considerations regarding assessment or quality management procedures can be found in different contexts. Footnote 11 While on one hand, the ongoing debate and (self-)questioning of artistic researchers leads to fruitful results, which continuously expand the discipline, Footnote 12 on the other hand the integration of AR approaches as a critical or methodological framework for teaching Footnote 13 demonstrates how established the field has become – even in traditional subject areas such as painting. Footnote 14

Nevertheless, the fractures still existing between art and academia lead to various daily challenges for art libraries. Footnote 15 Starting with the questions of access (acquisition and information retrieval), continuing with publication and data management support (including rights issues), up to an increasing institutional interest in the bibliometric measurement of art and science, one can find seemingly endless construction sites. At the same time, all have a common interest in locating AR. This leads to a simple (starting) question: Where is AR – or rather: How can AR results and outcomes be located?

The systematic search for AR on academic platforms such as Web of Science , Scopus , JSTOR and Design & Applied Arts Index ( DAAI ) results in a considerable number of findings. Nevertheless, most entries discuss or write about AR rather than being the results of AR in the sense that Borgdorff explained when stating:

We can justifiably speak of artistic research (‘research in the arts’), when that artistic practice is not only the result of the research, but also its methodological vehicle, when the research unfolds ‘in and through’ the acts of creating and performing. Footnote 16

The cited comment explains, among other things, why for example (digital) humanities repositories, publication services and research portals only partially cover the professional needs of art and design. Footnote 17 Even though they are located in the same cultural environment as creative, practice-based/practice-led approaches, there are fundamental differences in:

a) the way the research is conducted (including the definition of aims, the setting of methods and the prospecting for interim results);

b) the way that outcomes and publications appear in a variety of formats; and

c) the technical needs for describing, characterizing, or classifying. Footnote 18

Narrowing down the previously mentioned search results using classic research routines such as keywords, filtering dedicated media or document types, or other formal (metadata) characteristics is problematic in that conventions do not exist for this, nor are there preferred or standardized subject terms, publication formats or source-types. Of course, there is a Gemeinsame Normdatei (GND) entry for AR, Footnote 19 but finding or rather offering controlled vocabularies and classifications for dedicated subject areas in AR seems extremely difficult. Whereas on the one hand the lack of vocabularies or classification systems is problematic, Footnote 20 on the other hand the heterogeneity of the topics and methodologies, the creativity of the artists in questioning and (re-)inventing everything, and a certain scepticism complicate finding solutions. Footnote 21

In fact, the discomfort of the researching artists often begins earlier – within the publication or indexing process: object types used by repositories or publication servers such as OPUS , DSpace , Fedora and Zenodo, as well as those of the web portals mentioned, seem rather coarse compared to the diversity of artistic ways of expression and becoming public. Of course, Resource Description and Access (RDA) and most academic bibliographic systems in general offer a remarkable variety of media formats, while DataCite Footnote 22 and the Confederation of Open Access Repositories (COAR 2021 ) provide a remarkable list of resource type vocabularies. Nevertheless, the implementation is often pending. Thus, classifying artistic outcome remains demanding. In addition, Veerle Spronck points out:

The artistic researchers have to deal with art worlds (consisting of art critics, curators and festival organisers as well as the general art public), academic communities, and in some cases they contribute to public debates. To make the outcomes of their research relevant and assessable to these diverse audiences and communities, work needs to be done. Footnote 23

Understanding Efva Lilja's Footnote 24 recent statement “[t]he object of artistic research is art” Footnote 25 as a serious hint, another type of cataloguing system that has largely been neglected so far might come to mind: collection management systems. Footnote 26 Whereas Lilja's activating essay points to the risk of losing meaning or relevance when adapting (appropriating) scientific attitudes from other contexts too ambitiously, one might indeed ask how far scholarly communication could benefit from the ways of describing and documenting art. Footnote 27

Collection management systems specialize in taking the significance (individuality) of an artwork into account. While conservation science tends to speak of “significant properties”, when works of art become more complex, semantically breaking down “the” work of art to a set of elements which might be preserved in different ways, and looking at materials and techniques (as ways of creation) can enrich the present discussion. With regard to AR outcomes, methodologies gain special importance. As Rachel Mader explains, when reflecting on Brad Haseman's concept of practice as research approaches to creative arts enquiry: “research is not only conducted to create content, but also to expand the methods and instruments of artistic practices in each single case”. Footnote 28 Thus, AR methodologies might be understood as a natural progression of the material and techniques approach.

Expanding the forms of describing varying ways of creating, exploring, producing, and presenting, and the emphasis of methodologies calls to mind more recent developments in the context of scientific publishing as offered by data journals or data publications. Here, as there, the description of both the procedures of data collection and research methods, and the way in which the data was then structured and evaluated, contribute to the later understanding and subsequent re-use. Dedicated areas are therefore provided by the respective infrastructures. Relational models have replaced field-based indexing forms. Accordingly, a look at schemas such as CIDOC CRM from the cultural heritage perspective or Records in Context ( RIC ) from archival practice might be worthwhile. They stay structurally flexible and extendible, and therefore support creativity and liveness. Furthermore, conceptual models for describing such as the standard for open educational resources (IEEE Reference Lurk 2020 ), would have to be examined. LOM's ( Learning Object Metadata ) capacity to address different target groups even at the metadata level seems extremely interesting.

Nevertheless, our aim is not to promote yet another standard that is not applied because it is too complex or specific or fails to gain acceptance due to other reasons. Quite the opposite: we have the feeling that the initial question of the availability or rather the findability of AR results relates to further structural problems.

Starting, for example, with a well-established, scientific practice such as the referencing of sources of literature, data, tables, graphs, etc. used in articles and papers, it seems clear that citation conventions are so well established that algorithms automatically recognize most quoted sources. Automatic reference detection is, among other things, the basis for quotation indices. Footnote 29

As opposed to literature, artworks and AR outputs often elude citation. Even if works of art are named within a text, the automated detection of their mentions normally fails due to missing or incomplete structuring conventions. While lists of illustrations sometimes present a specific kind of index within the text, they nevertheless seem so little standardised that automated counts with an accuracy equivalent to Hirsch - Index or Received Citations are not yet available. This affects virtually all the artistic formats, including musical or performative scores, theatre plays and photographs that are not dealt with by well-known publishers - even if a catalogue raisonné exists with established numbering. Footnote 30

On the one hand this ties in with considerations in the museum context, in which referencing, the preservation of context and/or the quality assurance of online (re-)sources are discussed. Footnote 31 On the other hand, collaboratively created meta-searches such as European-art.net (EAN) are gaining importance. Footnote 32 Initiated by Basis Wien and resulting from the EU funded vektor (2000-2003) project, EAN references not only artists, Footnote 33 exhibitions and publications of the 13 partner institutions, but also enables searching for artworks, if the source databases release this information. To what extent the trend towards the visualization of collection holdings, as found in the context of Linked Open Data, Knowledge Graphs, various other data models and as countless pilot projects, is relevant for the present context of referencing remains to be examined.

Easy ways out of the dilemma are not to be expected in the short term, for the following reasons:

a) AR outcomes are spread across different genres (from dedicated works of art to curatorial work, from publication to performance, etc.) and artists tend to engage in different formats;

b) publication venues and institutional framings seem constantly changing, from academic context via gallery and museums spaces to public or alternative sphere(s), including digital and hybrid environments; and

c) communication channels often cover only temporary needs and disappear or migrate sooner or later to other media.

Furthermore, artistic outcomes, and especially those of AR, are bound to the presence of the audience. With Andrea Phillips one can state:

The claim of artistic research is that it is radically open and thus accessible to all comers, giving rise to questions of explanation, exposition, methodological investigation and publishing itself (in the sense of ‘making public’), especially in a field dominated by privatization (both in terms of art's connection to infrastructures of its market and in terms of the pedagogical habitus of individuation of expression). Footnote 34

The statement highlights another conflict zone that becomes obvious when publishing: the basic understanding of openness in relation to access. While the Budapest (2002) and Berlin Declaration (2003) define – from a libraries perspective – what Open Access (OA) is and how it should be marked, for many artists and researchers in this field, content that can be “consumed” without login, payment or admission is considered open and accessible. Therefore, just under 12% of the current AFPA-DB entries can effectively be described as OA, even though almost 28% are accessible without restrictions (bronze OA). Some faculties still believe that a sentence such as “[ title ] is accessible online to all (Open Access)” and the provision of a digital resource (PDF, image, video) make the publication OA. Expectations clash with reality when informing them that OA requires a clear statement for reuse, indicated for example by adding a creative commons statement and holding a signed contract note in hand (or in the archive). Accordingly, Clarrie Bishop has pointed out that successful OA projects are “about placing relationships at the heart of your work and thinking about rights collectively”. Footnote 35

Leaving aside “things” that are also traded on the art market, Footnote 36 and focussing instead on AR results and their context, OA currently gains increasing importance. In a cultural framework of inequality, in which many artists are still seeking a voice, permanent identifiers and the commons play a special role. They bring reliability, traceability, and permanence to a digital environment that otherwise seems highly dynamic and unstable. As Henk Borgdorff stated, when weighing the advantages and disadvantages of AR in relation to increasingly easier accessible scientific infrastructures:

You gain stability and the potential for distribution at the cost of the singularity and materiality of the operator. In artistic research this involves the chain of reference between artwork at the one extreme and artistic research publication at the other. Footnote 37

To put it differently: OA does not require reluctant relabelling, accepting reduced quality caused for example by low image resolution or black and white printing. Rather, the fracturing of incompatible legal systems creates space for new creativity, as encountered in different publishing contexts. Footnote 38 In a constructive, solution-oriented environment, it is then also possible to think carefully about what re-use can mean in the context of design and art.

AR seems to be a topic that is discussed at virtually all art academies. Nevertheless, when browsing the related scientific infrastructures, significant, partly structural, differences occur: while some art academies have developed digital memory infrastructures, others are still waiting for publication servers, repositories, or (supra-)institutional access. Differences determine the field in other contexts as well, for example financial and human resources, time span since resources were systematically documented, acquisition/indexing and publication policies, the question of how or where closed content is accessible (as metadata and data), accepted file-formats, evaluation mechanisms, and/or workflows and instruments for quality approval. Certainly, the size of the institution (measured by the number of staff and students), subject orientation (type of specializations), and structural scopes of action vary. Footnote 39

Since only parts of the AR outcomes find their way into the available repositories, the websites of the research institutes and their projects, associated PhD programmes and fellowships play a special role regarding AR dissemination. Even if neither plain HTML-websites nor portals with structured content management systems facilitate scholarly communication in terms of publication, access, and reuse (at least from a library perspective), these network-based channels still seem more easily equipped by artist researchers and thus more accessible than repositories or publication servers. Footnote 40 In addition, dedicated blogs, social media platforms and multimedia networks would require further consideration. Footnote 41

Regardless of the popularity of repositories among the artistic researchers, the lack of appropriate forms of citation and referencing has emerged as a particularly problematic area. The topic goes beyond the AR community and requires other disciplines to take responsibility for their sources. Whereas AR outcomes are indeed widely dispersed and hard to track, and thus tend to get lost in the plethora of activities, lack of global directories and referencing standards also cause problems.

Nonetheless, OA has emerged as an element that constructively stimulates the dialogue between libraries, artistic researchers, and, ever more frequently, non-affiliated artists or communities who can contribute to the discussion or provision of sources. Increasing interest in collaborative, sustainable, and resource-saving practices as well as manifold forms of access, accelerate the ways of knowledge production and consumption. Footnote 42 The tangible culture of cooperation and the claim to exchange ideas at eye level can contribute to the overcoming of existing divides. This can contribute to better accessibility of AR, too.

1. Only a few are recorded in OpenDOAR , which might be caused by the lack of FAIR interfaces such as OAI-PM. The acronym FAIR stands for free and sustainable access to digital databases, as the contents are f indable, a ccessible, i nteroperable and r eusable.

2. Swiss Artistic Research Network (SARN), Institut für Künstlerische Forschung (!KF Berlin), artresearch.eu (Gothenburg).

3. Since educational resources and research data (packages) only appeared in the control group, they are not mentioned in the figure above.

4. Cf. Sandra Mühlenberend, Sammlungen an Kunsthochschulen (Dresden, Reference Mühlenberend 2020 ).

5. Cf. Peter Peters et al. Dialogues between Artistic Research and Science and Technology Studies . (New York: Routledge, 2020).

6. Henk Borgdorff, “Cataloguing Artistic Research,” in Dialogues Between Artistic Research and Science and Technology Studies , ed. Henk Borgdorff et al. (New York: Routledge, 2019) 19-30.

7. Barnaby Drabble, and Federica Martini, “Publishing Artistic Research”, in SARN Booklet (Basel: SARN, 2014 ).

8. Gerald Bast et al., Arts, Research, Innovation and Society (Cham: Springer International Publishing, Reference Bast, Carayannis and Campbell 2015 ).

9. Mika Hannula et al., ed., Artistic Research Methodology (New York: Peter Lang Reference Hannula, Suoranta and Vadén 2014 ).

10. Tomas Lundén, and Karin Sundén, “Art as Academic Output,” Art Libraries Journal 40, no. 4 (2015): 25-32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307472200020496 .

11. Efva Lilja, “Art, Research, Empowerment.” C.f. also the scheme of Bartar & Huber ( Reference Bartar, Huber, Mateus-Berr and Jochum 2020 , 161). The provided grid for counter assessment of socially engaged arts- and community-based research can be transferred to other areas, in that it classifies: a) excellence of approach, b) innovation and originality, c) relevance for the particular field and other disciplines, d) scientific quality, e) quality of cooperation, f) dimensions of participation, g) added value for participants, h) process-oriented aspects, i) ethical principles, and j) open-science principles.

12. Regarding publication requirements, still the Journal for Artistic Research and its underlying Research Catalogue might be mentioned (Schwab Reference Schwab and Schwab 2013 ).

13. Cf. Ruth Mateus-Berr and Richard Jochum, Teaching Artistic Research (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, Reference Wälchli and Caduff 2020 ).

14. Cf. Stefan Wykydal, “Nonverbal Words”, in Teaching Artistic Research , edited by Ruth Mateus-Berr and Richard Jochum (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, Reference Wälchli and Caduff 2020 ), 67-72.

15. As the Vienna Declaration (cultureactioneurop.org 2020 ) attests, incompatibilities hurt the artists and academic institutions even more.

16. Henk Borgdorff, “The Conflict of the faculties” (PhD diss., University of Leiden, Reference Borgdorff 2012 ), 47.

17. The Registry of Research Data Repositories ( re3org ) lists in Germany arthistoricum.net (University of Heidelberg), the two image databases Foto Marburg and prometheus (Cologne), and ECHO - Cultural Heritage Online ( Max Planck Institute for the History of Science ). In addition, Kubikat ( bibliographic data ), heiData and the digital and interdisciplinary object and multimedia repository heidICON (both University of Heidelberg) were looked through. All of them focus primarily on art historical materials. Regarding AR, re3org presents the Research Catalogue (RC), Portal de Datos Abiertos UNAM (UNAM Open Data Portal, Colecciones Universitaria, Mexico) and Portal de Datos del Mar - SNDM (Portal Argentino de Datos del Mar, Argentina) when searching on a global scale.

18. Since researchers often record their content in research information systems, language plays a special role (cf. Wälchli & Caduff Reference Wälchli and Caduff 2019 ). A differentiation between practice and theory, for example, also seems inappropriate, since many artists perceive their reflective work as theoretical . Same with media formats such as video or non-text formats. They are by no means primarily related to AR.

19. http://d-nb.info/gnd/1068661038 .

20. Even Getty's vocabularies in the context of the Art and Archaeology Technical Abstracts (AATA) do not provide any specification for AR.

21. Duby, Barker Reference Duby and Barker 2017 comment: “The vocabulary of research has largely been predicated on scientific research or more precisely an oversimplified concept thereof which depends upon the supremacy of propositional knowledge”.

22. “DataCite Metadata Schema Documentation for the Publication and Citation of Research data – Version 4.3,” DataCite Metadata Working Group, last accessed on 6 October 2021, https://doi.org/10.14454/7xq3-zf69 .

23. Spronck, Veerle. “Between Art and Academia: A Study of the Practice of Third Cycle Artistic Research”. Maastricht University, Reference Spronck 2016 . https://lkca.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/scriptie-2017-between-art-and-academia-spronck.pdf .

24. Efva Lilja has been observing and participating in the Swedish AR development for decades.

25. Efva Lilja, “The Pot Calling the Kettle Black,” in Knowing in Performing , edited by Annegret Huber et al. (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, Reference Lilja, Huber, Ingrisch, Kaufmann, Kretz, Schröder and Zembylas 2021 ), 28.

26. For this reason, the Portal Wissenschaftliche Sammlungen (i.e. portal of scientific collections) was examined, even though primarily historical holdings are indexed. In contrast to the humanities’ portals, a broader range of scientific material and tool collections are listed with remarkable contents.

27. In the context of art collections, characterization and keywording normally follow at least in-house or internationally recognized, controlled vocabularies or typification.

28. Rachel Mader, “A Review of Artistic Research and Literature,” Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal 6, no. 2 (2021): 540.

29. Besides bibliometric interests, automated recognition of whole text passages plays an important role in plagiarism prevention.

30. Comparable problems are found in texts when the transliteration systems are lacking. Stefan Schley (conversation 2021) has recently pointed out this challenge of Tibetology.

31. Stefan Przigoda, “Sammlungsdokumentation, Forschung und Digitalisierung,” in Objekte im Netz, edited by Udo Andraschke and Sarah Wagner (Bielfeld: transcript Verlag, Reference Przigoda, Andraschke and Wagner 2020 ).

32. https://european-art.net/database .

33. Artists are assigned to GND and FIAV.

34. Andrea Philips, “Artistic Research, Publishing and Capitalisation,” in Futures of artistic research , edited by Jan Kaila et al., (Helsinki: The Academy of Fine Arts, Uniarts Helsinki, Reference Phillips, Kaila, Seppä and Slager 2017 ), 24.

35. Carrie Bishop, “Creative Commons and Open Access Initiatives”, Art Libraries Journal 40, no. 4 (2015): 9.

36. Regarding goods of the art market, one could argue that their transmission to the future is otherwise guaranteed.

37. Borgdorff, “Cataloguing,” 21f.

38. Stefanie Bringezu, Was ist Kunst? (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, Reference Bringezu 2012 ).

39. Art academies in Switzerland are for example located at the educational level of universities of applied sciences, which have no right to award doctorates. In Austria and Germany, too, not all art academies have the right to award PhD degrees, and some subjects areas are taught in faculties in which art is only one subject among others.

40. Micro affiliations and “unaffiliated knowledge workers” (Brown Reference Brown 2016 ) have (or are aware of) far fewer paths of publication in academically recognized contexts than academic members.

41. Without judging the trend, in 2010 the “alt-metrics manifesto” emphasized the growing importance of publication venues outside the classical academic setting (Priem et al. Reference Priem, Taraborelli, Groth and Neylon 2010 ). Regarding social academic networks, a quick keyword search of the outcomes has confirmed earlier experiences: the number of artistic outputs seems vanishingly small compared to the discussion about AR.

42. Cf. in this context the conceptual framework of Documenta 15 (2022) regarding publication and participation strategies of the management team ruangrupa.

No CrossRef data available.

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 47, Issue 2

- Tabea Lurk (a1) and Franziska Burger (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2022.4

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

Society for Artistic Research

The SAR Prize winner for 2023 has been announced!

The Executive Board of SAR is delighted to announce the winner of the Annual Prize for Excellent Research Catalogue Exposition 2023!

The full jury report can be read here .

| ” | |

| | |

| )” |

SAR International Forum on Artistic Research 2024

15th International Conference on Artistic Research

SAR International Forum on Artistic Research will take place from April 10 th to 11 th 2024 , hosted by Fontys Academy of the Arts in Tilburg .

REGISTER NOW! Program may be found here .

Deadline: 27th of March 2024

This year the Society for Artistic Research (SAR) introduces a new biennial meeting format, that offers time and space for thought-provoking and stimulating dialogue between artistic researchers, artists, practitioners, as well as policy makers and stakeholders from diverse backgrounds.

The Forum 2024 co-developed by Fontys and SAR to be a new and innovative biennial format, that will alternate with the already established SAR conferences .

What Methods Do – International Symposium on Artistic Research Methods

What Methods Do – Exploring the Transformative Potential of Artistic Research

This international symposium on Artistic Research Methods will take place at the Textile Museum in Tilburg on April 9 th 13:00-19:00 .

Annual Prize for Best RC Exposition 2023 – Nomination Deadline 01.02.24

Annual Prize for Best RC Exposition 2023 – Nomination Deadline 01.02.24

The Executive Board of SAR announces the opportunity to nominate candidates for the Annual Prize for Excellent Research Catalogue Exposition 2023. The prize aims to foster and encourage innovative, experimental new formats of publication and, on the other hand, to give visibility to the qualities of artistic research artifacts. The Executive Board will appoint a jury to assess the submissions. The jury consists of one member of the SAR Executive Board, one representative from portal partners, and one former prize winner. Please note: Previous winners of the prize cannot submit for three full years after receiving their award.

Publication period of submission: Jan 1, 2023 – Dec 31, 2023.

Deadline for submission: Jan 31, 2024.

Prize Award: € 500.

For submission info please read the official announcement.

SAR Prize (2022) : Winner Announced

The prize aims to foster and encourage innovative, experimental new formats of publication and to give visibility to the qualities of artistic research artefacts.

We received 14 very good and diverse applications from different disciplines. The evaluation was carried out by a jury composed of Paulo Luís Almeida, Jacek Smolicki and Blanka Chládková. The jury highly appreciates the quality and compactness of the exhibition by Andreas Berchtold titled “ In circles leading on “:

Honorable mentions go to: “ Spotting A Tree From A Pixel ” by Sheung Yiu and “ Fragments in Time ” by Tobias Leibetseder, Thomas Grill, Almut Schilling, Till Bovermann.

Read the full jury report here .

14th SAR Conference Trondheim: recordings available

Video recordings of the opening and the keynote speeches by Pier Luigi Sacco and Anjalika Sagar, as well as the program produced in the KIT video studio are available at the conference website .

SAR Prize (2021) Winner Announced!

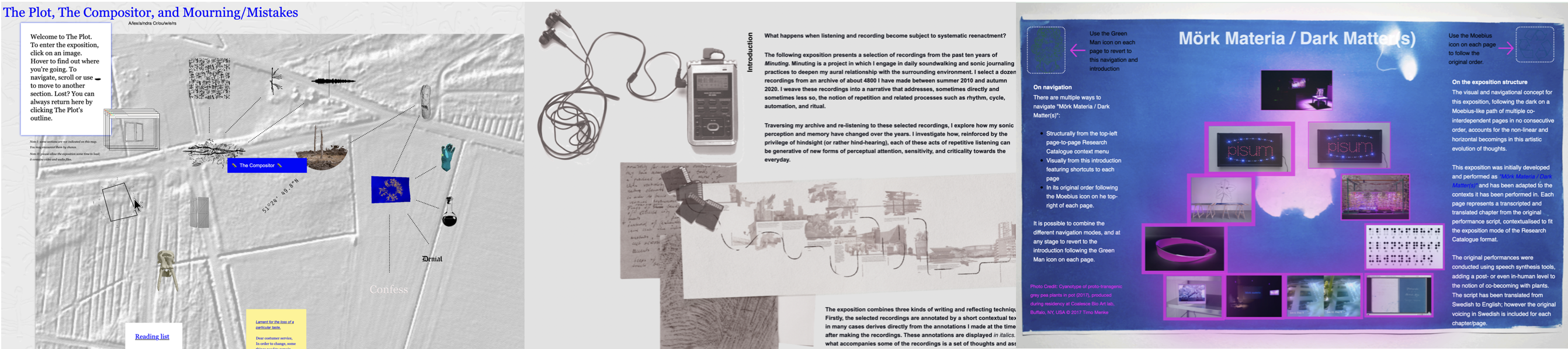

The Executive Board of SAR is delighted to announce the winner of the Annual Prize for Excellent Research Catalogue Exposition 2021. “ Minuting. Rethinking the Ordinary Through the Ritual of Transversal Listening ” by Jacek Smolicki.

He is followed by Alexandra Crouwers with her exposition “ Plot, the Compositor, Mourning/Mistakes ” on the second place and Timo Menke with his exposition “ DARK MATTER(S) ” on the third place.

Read the complete report here .

SAR General Assembly Election Results:

We hereby announce the results of the SAR elections that took place during the SAR General assembly on 4th of July 2022 in Weimar:

Florian Schneider has been elected SAR president (for 2022-2026)

Geir Ström has been re-elected SAR First Vice President/Treasurer (for 2022-2024)

Both Blanka Chládková & Esa Kirkkopelto have been elected as SAR board member (for 2022-2026)

See “ Who we are ” for more information.

Call for Establishing SAR Special Interest Groups – SIGs

The Executive Board is delighted to renew its Call for Establishing SAR Special Interest Groups (SIGs). SIGs may be suggested, organised, and moderated by any SAR member (individual members, representatives of institutional members) with the aim of conducting a particular activity, theme or focus area under the umbrella of SAR and promoting the activity and its results within the SAR community. For more information on establishing a SIG see: SAR Special Interest Groups (SIGs) .

CALL FOR SOLIDARITY AND PEACE

SAR expresses its solidarity with artists and researchers who as a consequence of war now have to fear for their own lives, and of those of their families and friends. We want to express our compassion with all those innocent civilians who are suffering. We are horrified about the ruthlessness with which civilian targets are attacked in the Ukraine, and we appeal for an immediate end to aggression, bloodshed and destruction and a return to human values in sight of the global future of the planet.

Like our partner associations AEC and ELIA, we state that the artistic research community is a global community where peaceful collaborations between people of all backgrounds are a lived reality. Thousands of Ukrainian and Russian students, academics, artists and researchers in art practices are at the same time working together peacefully all over Europe and the world. We stand by all these artists, as well as with Ukrainian people, in solidarity. We likewise call on all SAR member institutions to support refugees from the war zone within their possibilities to be able to continue their art studies in a non-bureaucratic way.

The future of life on the planet depends on the human ability for peaceful conflict resolution.

The SAR Presidents, Executive Board members, and Executive Officer

Vienna declaration

SAR is proud to present the Vienna Declaration , a policy paper advocating for the full recognition of Artistic Research across Europe. More than one year ago, the main organisations and transnational networks dealing with Artistic Research at European level and beyond decided to join forces to increase the visibility and recognition of this strand of research. The Vienna Declaration , co-written by AEC , CILECT / GEECT , Culture Action Europe , Cumulus , EAAE , ELIA , EPARM , EQ-Arts , MusiQuE and SAR, is the first outcome of this important collaboration. The initiative is open to the involvement of other international organisations proving legitimate interest.

The long term aims of this concerted action, and the formulation of documents such as the Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research and the Florence Principles on the Doctorate in the Arts , are to secure full recognition of artistic research both within international as well as national research directories and funding schemes.

SARA / Society for Artistic Research Announcement service

SAR enables individual and institutional members as well as non-members to distribute announcements of relevance to artistic research environments, such as symposia, conferences, exhibitions, performances, publications, study programmes, available positions etc. via a dedicated email list, reaching colleagues who have registered at the Research Catalogue (RC).

For more info or requesting an announcement, go to: sar-announcements.com

Become a SAR member Subscribe to the SAR newsletter

Sar-members: we have a new data protection policy ..

Begin typing your search term above and press enter to search. Press ESC to cancel.

Artistic Research

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Alexander Damianisch MAS 2

190 Accesses

2 Citations

Arts-based Research, Development of the Arts, Applied Arts, Expanded Research, Implicit Knowledge, Practice Based Research, Research in the Arts, Research through the Arts, Research on the Arts

The aim of this entry is to present basic thoughts regarding practices of artistic research with the objective to describe specific criteria pertaining to this specific process of knowledge production. References to considerations regarding the philosophy of science are possible, but not intended as a demarcation to the further thoughts presented that make up the central element of the entry. Central topics of artistic research are brought into focus, evaluated, and used to generate specific processes for knowledge development. After a brief thematic introduction to the topic and an attempt to a “mapping of artistic research,” specific aspects are described in the “setting of artistic research,” followed by the thoughts regarding concrete “modes of artistic research,” and concluded through...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adderley. vgl. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbie_Hancock#cite_ref-7 . 2012-07-17.

doCUMENTA (13): Das Begleitbuch/The Guidebook. Katalog/Catalog 3/3. Ostfildern 2012.

Google Scholar

Dombois F, Bauer UM, Mareis C, Schwab M, editors. Intellectual birdhouse: artistic practice as research. London: Walther König; 2011.

Novalis DWW. Notes for a Romantic encyclopaedia: Das Allgemeine Brouillon. Albany: Suny Press; 2007.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: aFrscati Manual - Proposed Standard Practice for Surveys on Research and Experimental Development. Paris: OECD; 2002.

Yamada K. The gateless gate: the classic book of Zen Koans. Boston: Wisdom Publications; 2004.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Support Art and Research, University of Applied Arts, Oskar Kokoschkaplatz 2, 1010, Vienna, Austria

Alexander Damianisch MAS ( Dr. phil. )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alexander Damianisch MAS .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Information Systems & Technology, Management, School of Business, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

Elias G. Carayannis

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Damianisch, A. (2013). Artistic Research. In: Carayannis, E.G. (eds) Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_473

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_473

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3857-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3858-8

eBook Packages : Business and Economics

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Distributed for Intellect Ltd

Art as Research

Opportunities and challenges.

Edited by Shaun McNiff

240 pages | 15 halftones | 6 x 9 | © 2013

Art: Art--General Studies

View all books from Intellect Ltd

- Table of contents

- Author Events

- Related Titles

Table of Contents

Be the first to know.

Get the latest updates on new releases, special offers, and media highlights when you subscribe to our email lists!

Sign up here for updates about the Press

Explainer: what is artistic research?

The role of artistic researchers is not to describe their work – it’s something else entirely.

By Professor Barb Bolt, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music.

Talk about scientific research and a few things immediately spring to mind: randomised controlled trials, journal articles, momentous breakthroughs … And while those things are also true in the arts (one need only look at the University’s Music Therapy discipline for proof) the parameters are often different. So, what does “artistic research” in a Faculty such as ours look like?

The terms “artwork” and “work of art” tend to be used interchangeably but it’s useful to tease them apart. The artwork may be defined as the production – the performance, recital, painting, sculptural installation, drawing, film, screenplay, novel, poem or event that has emerged. Meanwhile, the work of art is the work that art does: the movement in concepts, understandings, methodologies, material practice, affect and sensorial experience that arises in and through art and the artwork.

The mapping of this movement allows artistic researchers to identify and argue for the research’s claim to new knowledge, or rather new ways of knowing – which, of course, is what all research does. But the positioning of the researcher as maker and observer, and the multi-dimensional qualities that arise in artistic research, gives artistic research its particularity.

The role of the artistic researcher is not to describe his or her work, nor to interpret the work, but rather to recognise and map the ruptures and movements that are the work of art in a way not necessarily open to others. The artist-as-researcher offers a particular and unique perspective on the work of art from inside-out as well as outside-in.

In August, Dr Simone Slee, former Head of Sculpture and Spatial Practice and now the Research Convenor at VCA Art, as well as being a successful practising artist, was awarded a 2018 University of Melbourne Chancellor’s Prize for Excellence for her PhD thesis: Help a Sculpture and other abfunctional potentials – the first time an artistic research thesis has been recognised with this particular accolade.

As Simone observed in 2016:

Centering myself within the process of the artwork’s production was the most important factor in garnering my voice within the writing. Once I enabled this to occur the project began to drive its own agenda, developing an autonomy that was also akin to an artwork itself. Commencing with the artwork this firstly generated the research questions that then enabled these to be tested, sometimes contradicted, adjusted and clarified, and provoked new questions as they applied to the work.

This centering of oneself within the artwork’s production is the most important factor in giving voice to what has become known variously as practice-led research, practice as research (PAR), creative practice research (CPR) or, more simply, artistic research.

It is a truism to say that words are inadequate to the task of encapsulating the material fact and the experience of the artwork and one could argue that any the kind of discursive mapping process is a distancing device that creates objective “data” and denies the embodied experience that is central to our encounters with art. The artwork must stand eloquently in its own way, and if it doesn’t it fails. In this very important sense, elite art practice is necessarily at the heart of artistic research.

But through mapping the work of art as well as sending their artwork out into the world, artistic researchers offer a unique perspective on art, demonstrating and arguing for the impact of artistic research in the broader realm, and particularly in the academy.

In other words, artistic research has opened the possibility for artists to find their voice in a field where hitherto they have been the object of study by art historians, musicologists, critics, curators, and cultural theorists, amongst others.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Artistic Research: Context, Perspectives & A Definition

Excerpt of the introduction: In the first part, I will dissect the term research, dipping into the everlasting dispute about art versus science, coming back to the initial term of artistic research and giving ideas of what it is and what it can contribute to scientific research. In the last part I will focus on the education reformation, elaborating detected challenges and chances it might bring. As literature, the essay draws – amongst others – from the book Artistic research published by philosopher, editor and curator Annette W. Balkema and philosopher, editor, curator and Professor for Artistic Research at the MaHKU, Utrecht Graduate School of Visual Art and Design Henk Slager, who is also leading the publication of the Journal of Artistic Research (JAR). It is a collection of essays and discussions from a two-day symposium on artistic research. Other sources are websites of art academies involved in the development of artistic research, different speeches on the topic and the Belgian philosopher, writer and critic Dieter Lesage’s text Who’s Afraid of Artistic Research? On measuring artistic research output (2009). As the evolution of artistic research is still ongoing, I found it important to include a variety of different opinions, in order to detect common tendencies.

Related Papers

English version of "Künstlerische Forschung", in Hans-Peter Schwarz (Hg.): Zeichen nach vorn. 125 Jahre Hochschule für Gestaltung und Kunst Zürich. Hochschule für Gestaltung und Kunst Zürich, Zürich

Christoph Schenker

Knowledge in its current form is not identical to the knowledge of the sciences. Scientific knowledge is a specific kind of discourse that is set off from the discourse genres of other, non-scientific areas of competence. In concert, they all form a diversity of essentially equivalent and equally necessary systems. Nonetheless, the currently prevalent style of thinking is that cultivated by the sciences and the humanities. And it is primarily scientific technology that has proven to be the most efficient contributor to contemporary society's focus on innovation. Scholarship and the sciences also constitute the last bastion of a culture that exists exclusively as high culture. Scientific research is a curious mixture of ideology and practice, of realistic procedures and unreal demands. The need to resort to scientific support in order to reinforce the relevance or status of a given area of competence has become obsolete. In this paper I shall outline a few thoughts on the character of research in the fine arts. The concept of research is closely allied with the sciences. Even so, it is fruitful to apply this term to the pragmatic context of artistic endeavour although it is not possible to address the concepts of research and art in greater depth in this context.

Sisyphus — Journal of Education

Catarina Almeida

Although almost every debate about artistic research highlights its novelty in references to «uncertainty», »indefinability», and to its lack of identity whilst «bound to a tradition external to itself», this novelty has lasted for a few decades already. Many of the problems raised today are to be found back when research and art education began to relate within the academic context in the 1980s. So where is the speculative discussion on its uncertainty taking artistic research to? Is a solution intended to be found? Is there a problem to be solved? Through ‘productivitism’ this text argues that the aprioristic idea that artistic research is problematic has been securing its state of pendency and increasing its fragility. The final part of the article suggests a creative potential and a challenging dimension in the process of institutionalization, and ends by pointing out possible topics of work for a shared agenda with contemporary art.

Eidos. A Journal for Philosophy of Culture

Josef Früchtl

English version of "Einsicht und Intensivierung - Überlegungen zur künstlerischen Forschung", in Elke Bippus (Hg.): Kunst des Forschens. Praxis eines ästhetischen Denkens. Diaphanes, Zürich/Berlin

What is it that distinguishes artistic research? Can one speak of a tradition of artistic problems? The tendency is to concentrate on trying to define the essential features of artistic research. This involves inquiry into not only how artistic research differs from but also how it resembles or is comparable to scientific research and philosophical work. As far the pragmatics of research are concerned, there is no fundamental difference between the systems of art and scholarship. And in both fields, it is often no easy task to distinguish substance, i.e. what is essential and intrinsic to the conditions and rules of the research process, from accident, i.e. what factors should be assigned to the external operations of research. One might inquire into whether artistic research works with special methods, whether it makes use of a specific set of tools, whether it typically addresses a specific subject of research, and whether it produces knowledge that is characteristic of art.

Dieter Mersch

Since its beginnings in the 1990s, “artistic research” has become established as a new format in the areas of educational and institutional policy, aesthetics, and art theory. It has now diffused into almost all artistic fields, from installation to experimental formats to contemporary music, literature, dance or performance art. But from its beginnings—under labels like “art and science” or “scienceart” or “artscience” that mention both disciplines in one breath—it has been in competition with academic research, without its own concept of research having been adequately clarified. This manifesto attempts to resolve the problem and to defend the term and the radical potentials of a researching art against those who toy all too carefully with university formats, wishing to ally them with scientific principles. Its aim is to emphasize the autonomy and particular intellectuality of artistic research, without seeking to justify its legitimacy or adopt alien standards.

Gideon Kong

The term ‘artistic research’ is generally referred to as research in the arts, or ‘art as research’. More distinctively, it is also described as ‘research in and through art’ (Wesseling 2016, 8), distinguished from other types of research in the arts and brings to mind the popular yet seldom consistently discussed categorical distinctions from Christopher Frayling (1993). With increasing discussions to identify, describe, and legitimise artistic research against the largely scientific traditions of ‘research’, there has since been a growing amount of literature on the subject. Despite this accessibility of literature on artistic research—many written in English and published in easily available or open access journals—they often remain as efforts isolated from each other. I highlight this as an opportunity for mapping key ideas and developments of artistic research within recent discourse. This essay attempts a brief yet condensed discussion on artistic research using six recent key texts on artistic research. Chronologically, they are single books from authors Graeme Sullivan (2005), James Elkin (2009), Henk Borgdorff (2012), Mika Hannula et al. (2014), Janneke Wesseling (2016), and Danny Butt (2017).

Aldis Gedutis

Gerard Vilar

catala«La recerca artistica» es un terme de moda que sembla portar les practiques de les arts contemporanies cap a noves formes, academicament mes respectables i properes a les ciencies socials i empiriques i a les humanitats. La introduccio de doctorats a les escoles d’arts i la normalitzacio dels plans d’estudi a Europa arran del Proces de Bolonya han estat cabdals en aquest sentit. Aquestes urgencies han creat una confusio enorme al voltant del significat de «recerca artistica». M’agradaria ajudar a aportar una mica d’ordre a aquestes veus sovint contradictories. El valor de l’art rau en el que el separa de la religio, la ciencia, la filosofia i totes les altres formes i productes del pensament huma, i estic convencut que qualsevol persona que cerqui el reconeixement academic i l’eliminacio de les diferencies esta confosa. En aquest article distingeixo entre cinc conceptes diferents en l’us de l’expressio «recerca artistica»: 1. Recerca per a l’art; es a dir, per a la produccio d...

Proceedings of the Arts Research Africa Conference

Mark Fleishman