- Privacy Policy

Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Validity is a fundamental concept in research, referring to the extent to which a test, measurement, or study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. Ensuring validity is crucial as it determines the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings.

Research Validity

Research validity pertains to the accuracy and truthfulness of the research. It examines whether the research truly measures what it claims to measure. Without validity, research results can be misleading or erroneous, leading to incorrect conclusions and potentially flawed applications.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several strategies:

- Clear Operational Definitions : Define variables clearly and precisely.

- Use of Reliable Instruments : Employ measurement tools that have been tested for reliability.

- Pilot Testing : Conduct preliminary studies to refine the research design and instruments.

- Triangulation : Use multiple methods or sources to cross-verify results.

- Control Variables : Control extraneous variables that might influence the outcomes.

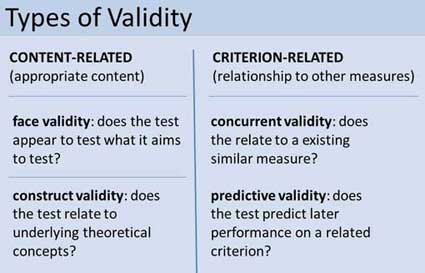

Types of Validity

Validity is categorized into several types, each addressing different aspects of measurement accuracy.

Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to the degree to which the results of a study can be attributed to the treatments or interventions rather than other factors. It is about ensuring that the study is free from confounding variables that could affect the outcome.

External Validity

External validity concerns the extent to which the research findings can be generalized to other settings, populations, or times. High external validity means the results are applicable beyond the specific context of the study.

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a test or instrument measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. It involves ensuring that the test is truly assessing the concept it claims to represent.

Content Validity

Content validity examines whether a test covers the entire range of the concept being measured. It ensures that the test items represent all facets of the concept.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity assesses how well one measure predicts an outcome based on another measure. It is divided into two types:

- Predictive Validity : How well a test predicts future performance.

- Concurrent Validity : How well a test correlates with a currently existing measure.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the extent to which a test appears to measure what it is supposed to measure, based on superficial inspection. While it is the least scientific measure of validity, it is important for ensuring that stakeholders believe in the test’s relevance.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial because it directly affects the credibility of research findings. Valid results ensure that conclusions drawn from research are accurate and can be trusted. This, in turn, influences the decisions and policies based on the research.

Examples of Validity

- Internal Validity : A randomized controlled trial (RCT) where the random assignment of participants helps eliminate biases.

- External Validity : A study on educational interventions that can be applied to different schools across various regions.

- Construct Validity : A psychological test that accurately measures depression levels.

- Content Validity : An exam that covers all topics taught in a course.

- Criterion Validity : A job performance test that predicts future job success.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, the methodology section should include discussions about validity. Here, you explain how you ensured the validity of your research instruments and design. Additionally, you may discuss validity in the results section, interpreting how the validity of your measurements affects your findings.

Applications of Validity

Validity has wide applications across various fields:

- Education : Ensuring assessments accurately measure student learning.

- Psychology : Developing tests that correctly diagnose mental health conditions.

- Market Research : Creating surveys that accurately capture consumer preferences.

Limitations of Validity

While ensuring validity is essential, it has its limitations:

- Complexity : Achieving high validity can be complex and resource-intensive.

- Context-Specific : Some validity types may not be universally applicable across all contexts.

- Subjectivity : Certain types of validity, like face validity, involve subjective judgments.

By understanding and addressing these aspects of validity, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their studies, leading to more reliable and actionable results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Content Validity – Measurement and Examples

Construct Validity – Types, Threats and Examples

External Validity – Threats, Examples and Types

Parallel Forms Reliability – Methods, Example...

Split-Half Reliability – Methods, Examples and...

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Validity in research: a guide to measuring the right things

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Validity is necessary for all types of studies ranging from market validation of a business or product idea to the effectiveness of medical trials and procedures. So, how can you determine whether your research is valid? This guide can help you understand what validity is, the types of validity in research, and the factors that affect research validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is validity?

In the most basic sense, validity is the quality of being based on truth or reason. Valid research strives to eliminate the effects of unrelated information and the circumstances under which evidence is collected.

Validity in research is the ability to conduct an accurate study with the right tools and conditions to yield acceptable and reliable data that can be reproduced. Researchers rely on carefully calibrated tools for precise measurements. However, collecting accurate information can be more of a challenge.

Studies must be conducted in environments that don't sway the results to achieve and maintain validity. They can be compromised by asking the wrong questions or relying on limited data.

Why is validity important in research?

Research is used to improve life for humans. Every product and discovery, from innovative medical breakthroughs to advanced new products, depends on accurate research to be dependable. Without it, the results couldn't be trusted, and products would likely fail. Businesses would lose money, and patients couldn't rely on medical treatments.

While wasting money on a lousy product is a concern, lack of validity paints a much grimmer picture in the medical field or producing automobiles and airplanes, for example. Whether you're launching an exciting new product or conducting scientific research, validity can determine success and failure.

- What is reliability?

Reliability is the ability of a method to yield consistency. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same method to measure something, the measurement method is said to be reliable. For example, a thermometer that shows the same temperatures each time in a controlled environment is reliable.

While high reliability is a part of measuring validity, it's only part of the puzzle. If the reliable thermometer hasn't been properly calibrated and reliably measures temperatures two degrees too high, it doesn't provide a valid (accurate) measure of temperature.

Similarly, if a researcher uses a thermometer to measure weight, the results won't be accurate because it's the wrong tool for the job.

- How are reliability and validity assessed?

While measuring reliability is a part of measuring validity, there are distinct ways to assess both measurements for accuracy.

How is reliability measured?

These measures of consistency and stability help assess reliability, including:

Consistency and stability of the same measure when repeated multiple times and conditions

Consistency and stability of the measure across different test subjects

Consistency and stability of results from different parts of a test designed to measure the same thing

How is validity measured?

Since validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure, it can be difficult to assess the accuracy. Validity can be estimated by comparing research results to other relevant data or theories.

The adherence of a measure to existing knowledge of how the concept is measured

The ability to cover all aspects of the concept being measured

The relation of the result in comparison with other valid measures of the same concept

- What are the types of validity in a research design?

Research validity is broadly gathered into two groups: internal and external. Yet, this grouping doesn't clearly define the different types of validity. Research validity can be divided into seven distinct groups.

Face validity : A test that appears valid simply because of the appropriateness or relativity of the testing method, included information, or tools used.

Content validity : The determination that the measure used in research covers the full domain of the content.

Construct validity : The assessment of the suitability of the measurement tool to measure the activity being studied.

Internal validity : The assessment of how your research environment affects measurement results. This is where other factors can’t explain the extent of an observed cause-and-effect response.

External validity : The extent to which the study will be accurate beyond the sample and the level to which it can be generalized in other settings, populations, and measures.

Statistical conclusion validity: The determination of whether a relationship exists between procedures and outcomes (appropriate sampling and measuring procedures along with appropriate statistical tests).

Criterion-related validity : A measurement of the quality of your testing methods against a criterion measure (like a “gold standard” test) that is measured at the same time.

- Examples of validity

Like different types of research and the various ways to measure validity, examples of validity can vary widely. These include:

A questionnaire may be considered valid because each question addresses specific and relevant aspects of the study subject.

In a brand assessment study, researchers can use comparison testing to verify the results of an initial study. For example, the results from a focus group response about brand perception are considered more valid when the results match that of a questionnaire answered by current and potential customers.

A test to measure a class of students' understanding of the English language contains reading, writing, listening, and speaking components to cover the full scope of how language is used.

- Factors that affect research validity

Certain factors can affect research validity in both positive and negative ways. By understanding the factors that improve validity and those that threaten it, you can enhance the validity of your study. These include:

Random selection of participants vs. the selection of participants that are representative of your study criteria

Blinding with interventions the participants are unaware of (like the use of placebos)

Manipulating the experiment by inserting a variable that will change the results

Randomly assigning participants to treatment and control groups to avoid bias

Following specific procedures during the study to avoid unintended effects

Conducting a study in the field instead of a laboratory for more accurate results

Replicating the study with different factors or settings to compare results

Using statistical methods to adjust for inconclusive data

What are the common validity threats in research, and how can their effects be minimized or nullified?

Research validity can be difficult to achieve because of internal and external threats that produce inaccurate results. These factors can jeopardize validity.

History: Events that occur between an early and later measurement

Maturation: The passage of time in a study can include data on actions that would have naturally occurred outside of the settings of the study

Repeated testing: The outcome of repeated tests can change the outcome of followed tests

Selection of subjects: Unconscious bias which can result in the selection of uniform comparison groups

Statistical regression: Choosing subjects based on extremes doesn't yield an accurate outcome for the majority of individuals

Attrition: When the sample group is diminished significantly during the course of the study

Maturation: When subjects mature during the study, and natural maturation is awarded to the effects of the study

While some validity threats can be minimized or wholly nullified, removing all threats from a study is impossible. For example, random selection can remove unconscious bias and statistical regression.

Researchers can even hope to avoid attrition by using smaller study groups. Yet, smaller study groups could potentially affect the research in other ways. The best practice for researchers to prevent validity threats is through careful environmental planning and t reliable data-gathering methods.

- How to ensure validity in your research

Researchers should be mindful of the importance of validity in the early planning stages of any study to avoid inaccurate results. Researchers must take the time to consider tools and methods as well as how the testing environment matches closely with the natural environment in which results will be used.

The following steps can be used to ensure validity in research:

Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Use appropriate sampling to choose test subjects

Create an accurate testing environment

How do you maintain validity in research?

Accurate research is usually conducted over a period of time with different test subjects. To maintain validity across an entire study, you must take specific steps to ensure that gathered data has the same levels of accuracy.

Consistency is crucial for maintaining validity in research. When researchers apply methods consistently and standardize the circumstances under which data is collected, validity can be maintained across the entire study.

Is there a need for validation of the research instrument before its implementation?

An essential part of validity is choosing the right research instrument or method for accurate results. Consider the thermometer that is reliable but still produces inaccurate results. You're unlikely to achieve research validity without activities like calibration, content, and construct validity.

- Understanding research validity for more accurate results

Without validity, research can't provide the accuracy necessary to deliver a useful study. By getting a clear understanding of validity in research, you can take steps to improve your research skills and achieve more accurate results.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

Reliability vs. Validity in Research | Difference, Types and Examples

Published on July 3, 2019 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Reliability and validity are concepts used to evaluate the quality of research. They indicate how well a method , technique. or test measures something. Reliability is about the consistency of a measure, and validity is about the accuracy of a measure.opt

It’s important to consider reliability and validity when you are creating your research design , planning your methods, and writing up your results, especially in quantitative research . Failing to do so can lead to several types of research bias and seriously affect your work.

| Reliability | Validity | |

|---|---|---|

| What does it tell you? | The extent to which the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. | The extent to which the results really measure what they are supposed to measure. |

| How is it assessed? | By checking the consistency of results across time, across different observers, and across parts of the test itself. | By checking how well the results correspond to established theories and other measures of the same concept. |

| How do they relate? | A reliable measurement is not always valid: the results might be , but they’re not necessarily correct. | A valid measurement is generally reliable: if a test produces accurate results, they should be reproducible. |

Table of contents

Understanding reliability vs validity, how are reliability and validity assessed, how to ensure validity and reliability in your research, where to write about reliability and validity in a thesis, other interesting articles.

Reliability and validity are closely related, but they mean different things. A measurement can be reliable without being valid. However, if a measurement is valid, it is usually also reliable.

What is reliability?

Reliability refers to how consistently a method measures something. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same methods under the same circumstances, the measurement is considered reliable.

What is validity?

Validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure. If research has high validity, that means it produces results that correspond to real properties, characteristics, and variations in the physical or social world.

High reliability is one indicator that a measurement is valid. If a method is not reliable, it probably isn’t valid.

If the thermometer shows different temperatures each time, even though you have carefully controlled conditions to ensure the sample’s temperature stays the same, the thermometer is probably malfunctioning, and therefore its measurements are not valid.

However, reliability on its own is not enough to ensure validity. Even if a test is reliable, it may not accurately reflect the real situation.

Validity is harder to assess than reliability, but it is even more important. To obtain useful results, the methods you use to collect data must be valid: the research must be measuring what it claims to measure. This ensures that your discussion of the data and the conclusions you draw are also valid.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Reliability can be estimated by comparing different versions of the same measurement. Validity is harder to assess, but it can be estimated by comparing the results to other relevant data or theory. Methods of estimating reliability and validity are usually split up into different types.

Types of reliability

Different types of reliability can be estimated through various statistical methods.

| Type of reliability | What does it assess? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The consistency of a measure : do you get the same results when you repeat the measurement? | A group of participants complete a designed to measure personality traits. If they repeat the questionnaire days, weeks or months apart and give the same answers, this indicates high test-retest reliability. | |

| The consistency of a measure : do you get the same results when different people conduct the same measurement? | Based on an assessment criteria checklist, five examiners submit substantially different results for the same student project. This indicates that the assessment checklist has low inter-rater reliability (for example, because the criteria are too subjective). | |

| The consistency of : do you get the same results from different parts of a test that are designed to measure the same thing? | You design a questionnaire to measure self-esteem. If you randomly split the results into two halves, there should be a between the two sets of results. If the two results are very different, this indicates low internal consistency. |

Types of validity

The validity of a measurement can be estimated based on three main types of evidence. Each type can be evaluated through expert judgement or statistical methods.

| Type of validity | What does it assess? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The adherence of a measure to of the concept being measured. | A self-esteem questionnaire could be assessed by measuring other traits known or assumed to be related to the concept of self-esteem (such as social skills and ). Strong correlation between the scores for self-esteem and associated traits would indicate high construct validity. | |

| The extent to which the measurement of the concept being measured. | A test that aims to measure a class of students’ level of Spanish contains reading, writing and speaking components, but no listening component. Experts agree that listening comprehension is an essential aspect of language ability, so the test lacks content validity for measuring the overall level of ability in Spanish. | |

| The extent to which the result of a measure corresponds to of the same concept. | A is conducted to measure the political opinions of voters in a region. If the results accurately predict the later outcome of an election in that region, this indicates that the survey has high criterion validity. |

To assess the validity of a cause-and-effect relationship, you also need to consider internal validity (the design of the experiment ) and external validity (the generalizability of the results).

The reliability and validity of your results depends on creating a strong research design , choosing appropriate methods and samples, and conducting the research carefully and consistently.

Ensuring validity

If you use scores or ratings to measure variations in something (such as psychological traits, levels of ability or physical properties), it’s important that your results reflect the real variations as accurately as possible. Validity should be considered in the very earliest stages of your research, when you decide how you will collect your data.

- Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Ensure that your method and measurement technique are high quality and targeted to measure exactly what you want to know. They should be thoroughly researched and based on existing knowledge.

For example, to collect data on a personality trait, you could use a standardized questionnaire that is considered reliable and valid. If you develop your own questionnaire, it should be based on established theory or findings of previous studies, and the questions should be carefully and precisely worded.

- Use appropriate sampling methods to select your subjects

To produce valid and generalizable results, clearly define the population you are researching (e.g., people from a specific age range, geographical location, or profession). Ensure that you have enough participants and that they are representative of the population. Failing to do so can lead to sampling bias and selection bias .

Ensuring reliability

Reliability should be considered throughout the data collection process. When you use a tool or technique to collect data, it’s important that the results are precise, stable, and reproducible .

- Apply your methods consistently

Plan your method carefully to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each measurement. This is especially important if multiple researchers are involved.

For example, if you are conducting interviews or observations , clearly define how specific behaviors or responses will be counted, and make sure questions are phrased the same way each time. Failing to do so can lead to errors such as omitted variable bias or information bias .

- Standardize the conditions of your research

When you collect your data, keep the circumstances as consistent as possible to reduce the influence of external factors that might create variation in the results.

For example, in an experimental setup, make sure all participants are given the same information and tested under the same conditions, preferably in a properly randomized setting. Failing to do so can lead to a placebo effect , Hawthorne effect , or other demand characteristics . If participants can guess the aims or objectives of a study, they may attempt to act in more socially desirable ways.

It’s appropriate to discuss reliability and validity in various sections of your thesis or dissertation or research paper . Showing that you have taken them into account in planning your research and interpreting the results makes your work more credible and trustworthy.

| Section | Discuss |

|---|---|

| What have other researchers done to devise and improve methods that are reliable and valid? | |

| How did you plan your research to ensure reliability and validity of the measures used? This includes the chosen sample set and size, sample preparation, external conditions and measuring techniques. | |

| If you calculate reliability and validity, state these values alongside your main results. | |

| This is the moment to talk about how reliable and valid your results actually were. Were they consistent, and did they reflect true values? If not, why not? | |

| If reliability and validity were a big problem for your findings, it might be helpful to mention this here. |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Middleton, F. (2023, June 22). Reliability vs. Validity in Research | Difference, Types and Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/reliability-vs-validity/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition, uses & methods, data collection | definition, methods & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Validity & Reliability In Research

A Plain-Language Explanation (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | September 2023

Validity and reliability are two related but distinctly different concepts within research. Understanding what they are and how to achieve them is critically important to any research project. In this post, we’ll unpack these two concepts as simply as possible.

This post is based on our popular online course, Research Methodology Bootcamp . In the course, we unpack the basics of methodology using straightfoward language and loads of examples. If you’re new to academic research, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Validity & Reliability

- The big picture

- Validity 101

- Reliability 101

- Key takeaways

First, The Basics…

First, let’s start with a big-picture view and then we can zoom in to the finer details.

Validity and reliability are two incredibly important concepts in research, especially within the social sciences. Both validity and reliability have to do with the measurement of variables and/or constructs – for example, job satisfaction, intelligence, productivity, etc. When undertaking research, you’ll often want to measure these types of constructs and variables and, at the simplest level, validity and reliability are about ensuring the quality and accuracy of those measurements .

As you can probably imagine, if your measurements aren’t accurate or there are quality issues at play when you’re collecting your data, your entire study will be at risk. Therefore, validity and reliability are very important concepts to understand (and to get right). So, let’s unpack each of them.

What Is Validity?

In simple terms, validity (also called “construct validity”) is all about whether a research instrument accurately measures what it’s supposed to measure .

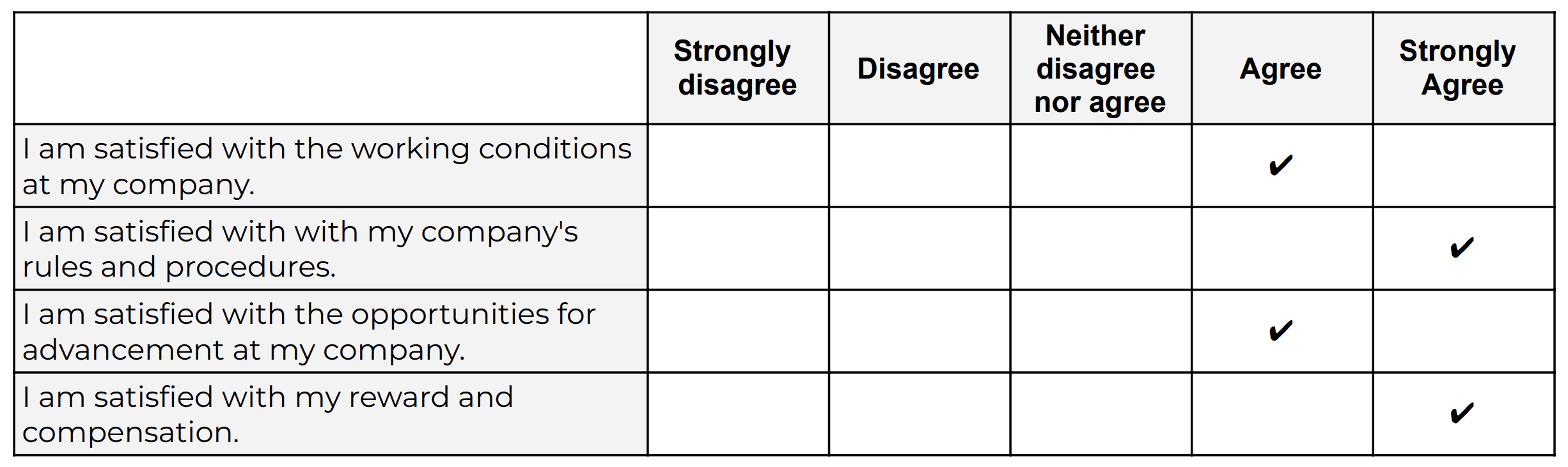

For example, let’s say you have a set of Likert scales that are supposed to quantify someone’s level of overall job satisfaction. If this set of scales focused purely on only one dimension of job satisfaction, say pay satisfaction, this would not be a valid measurement, as it only captures one aspect of the multidimensional construct. In other words, pay satisfaction alone is only one contributing factor toward overall job satisfaction, and therefore it’s not a valid way to measure someone’s job satisfaction.

Oftentimes in quantitative studies, the way in which the researcher or survey designer interprets a question or statement can differ from how the study participants interpret it . Given that respondents don’t have the opportunity to ask clarifying questions when taking a survey, it’s easy for these sorts of misunderstandings to crop up. Naturally, if the respondents are interpreting the question in the wrong way, the data they provide will be pretty useless . Therefore, ensuring that a study’s measurement instruments are valid – in other words, that they are measuring what they intend to measure – is incredibly important.

There are various types of validity and we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole in this post, but it’s worth quickly highlighting the importance of making sure that your research instrument is tightly aligned with the theoretical construct you’re trying to measure . In other words, you need to pay careful attention to how the key theories within your study define the thing you’re trying to measure – and then make sure that your survey presents it in the same way.

For example, sticking with the “job satisfaction” construct we looked at earlier, you’d need to clearly define what you mean by job satisfaction within your study (and this definition would of course need to be underpinned by the relevant theory). You’d then need to make sure that your chosen definition is reflected in the types of questions or scales you’re using in your survey . Simply put, you need to make sure that your survey respondents are perceiving your key constructs in the same way you are. Or, even if they’re not, that your measurement instrument is capturing the necessary information that reflects your definition of the construct at hand.

If all of this talk about constructs sounds a bit fluffy, be sure to check out Research Methodology Bootcamp , which will provide you with a rock-solid foundational understanding of all things methodology-related. Remember, you can take advantage of our 60% discount offer using this link.

Need a helping hand?

What Is Reliability?

As with validity, reliability is an attribute of a measurement instrument – for example, a survey, a weight scale or even a blood pressure monitor. But while validity is concerned with whether the instrument is measuring the “thing” it’s supposed to be measuring, reliability is concerned with consistency and stability . In other words, reliability reflects the degree to which a measurement instrument produces consistent results when applied repeatedly to the same phenomenon , under the same conditions .

As you can probably imagine, a measurement instrument that achieves a high level of consistency is naturally more dependable (or reliable) than one that doesn’t – in other words, it can be trusted to provide consistent measurements . And that, of course, is what you want when undertaking empirical research. If you think about it within a more domestic context, just imagine if you found that your bathroom scale gave you a different number every time you hopped on and off of it – you wouldn’t feel too confident in its ability to measure the variable that is your body weight 🙂

It’s worth mentioning that reliability also extends to the person using the measurement instrument . For example, if two researchers use the same instrument (let’s say a measuring tape) and they get different measurements, there’s likely an issue in terms of how one (or both) of them are using the measuring tape. So, when you think about reliability, consider both the instrument and the researcher as part of the equation.

As with validity, there are various types of reliability and various tests that can be used to assess the reliability of an instrument. A popular one that you’ll likely come across for survey instruments is Cronbach’s alpha , which is a statistical measure that quantifies the degree to which items within an instrument (for example, a set of Likert scales) measure the same underlying construct . In other words, Cronbach’s alpha indicates how closely related the items are and whether they consistently capture the same concept .

Recap: Key Takeaways

Alright, let’s quickly recap to cement your understanding of validity and reliability:

- Validity is concerned with whether an instrument (e.g., a set of Likert scales) is measuring what it’s supposed to measure

- Reliability is concerned with whether that measurement is consistent and stable when measuring the same phenomenon under the same conditions.

In short, validity and reliability are both essential to ensuring that your data collection efforts deliver high-quality, accurate data that help you answer your research questions . So, be sure to always pay careful attention to the validity and reliability of your measurement instruments when collecting and analysing data. As the adage goes, “rubbish in, rubbish out” – make sure that your data inputs are rock-solid.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Methodology Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS.

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS AND I HAVE GREATLY BENEFITED FROM THE CONTENT.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Reliability and validity are concepts used to evaluate the quality of research. They indicate how well a method , technique, or test measures something. Reliability is about the consistency of a measure, and validity is about the accuracy of a measure.

It’s important to consider reliability and validity when you are creating your research design , planning your methods, and writing up your results, especially in quantitative research .

| Reliability | Validity | |

|---|---|---|

| What does it tell you? | The extent to which the results can be reproduced when the research is repeated under the same conditions. | The extent to which the results really measure what they are supposed to measure. |

| How is it assessed? | By checking the consistency of results across time, across different observers, and across parts of the test itself. | By checking how well the results correspond to established theories and other measures of the same concept. |

| How do they relate? | A reliable measurement is not always valid: the results might be reproducible, but they’re not necessarily correct. | A valid measurement is generally reliable: if a test produces accurate results, they should be . |

Table of contents

Understanding reliability vs validity, how are reliability and validity assessed, how to ensure validity and reliability in your research, where to write about reliability and validity in a thesis.

Reliability and validity are closely related, but they mean different things. A measurement can be reliable without being valid. However, if a measurement is valid, it is usually also reliable.

What is reliability?

Reliability refers to how consistently a method measures something. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same methods under the same circumstances, the measurement is considered reliable.

What is validity?

Validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure. If research has high validity, that means it produces results that correspond to real properties, characteristics, and variations in the physical or social world.

High reliability is one indicator that a measurement is valid. If a method is not reliable, it probably isn’t valid.

However, reliability on its own is not enough to ensure validity. Even if a test is reliable, it may not accurately reflect the real situation.

Validity is harder to assess than reliability, but it is even more important. To obtain useful results, the methods you use to collect your data must be valid: the research must be measuring what it claims to measure. This ensures that your discussion of the data and the conclusions you draw are also valid.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Reliability can be estimated by comparing different versions of the same measurement. Validity is harder to assess, but it can be estimated by comparing the results to other relevant data or theory. Methods of estimating reliability and validity are usually split up into different types.

Types of reliability

Different types of reliability can be estimated through various statistical methods.

| Type of reliability | What does it assess? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The consistency of a measure : do you get the same results when you repeat the measurement? | A group of participants complete a designed to measure personality traits. If they repeat the questionnaire days, weeks, or months apart and give the same answers, this indicates high test-retest reliability. | |

| The consistency of a measure : do you get the same results when different people conduct the same measurement? | Based on an assessment criteria checklist, five examiners submit substantially different results for the same student project. This indicates that the assessment checklist has low inter-rater reliability (for example, because the criteria are too subjective). | |

| The consistency of : do you get the same results from different parts of a test that are designed to measure the same thing? | You design a questionnaire to measure self-esteem. If you randomly split the results into two halves, there should be a between the two sets of results. If the two results are very different, this indicates low internal consistency. |

Types of validity

The validity of a measurement can be estimated based on three main types of evidence. Each type can be evaluated through expert judgement or statistical methods.

| Type of validity | What does it assess? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| The adherence of a measure to of the concept being measured. | A self-esteem questionnaire could be assessed by measuring other traits known or assumed to be related to the concept of self-esteem (such as social skills and optimism). Strong correlation between the scores for self-esteem and associated traits would indicate high construct validity. | |

| The extent to which the measurement of the concept being measured. | A test that aims to measure a class of students’ level of Spanish contains reading, writing, and speaking components, but no listening component. Experts agree that listening comprehension is an essential aspect of language ability, so the test lacks content validity for measuring the overall level of ability in Spanish. | |

| The extent to which the result of a measure corresponds to of the same concept. | A is conducted to measure the political opinions of voters in a region. If the results accurately predict the later outcome of an election in that region, this indicates that the survey has high criterion validity. |

To assess the validity of a cause-and-effect relationship, you also need to consider internal validity (the design of the experiment ) and external validity (the generalisability of the results).

The reliability and validity of your results depends on creating a strong research design , choosing appropriate methods and samples, and conducting the research carefully and consistently.

Ensuring validity

If you use scores or ratings to measure variations in something (such as psychological traits, levels of ability, or physical properties), it’s important that your results reflect the real variations as accurately as possible. Validity should be considered in the very earliest stages of your research, when you decide how you will collect your data .

- Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Ensure that your method and measurement technique are of high quality and targeted to measure exactly what you want to know. They should be thoroughly researched and based on existing knowledge.

For example, to collect data on a personality trait, you could use a standardised questionnaire that is considered reliable and valid. If you develop your own questionnaire, it should be based on established theory or the findings of previous studies, and the questions should be carefully and precisely worded.

- Use appropriate sampling methods to select your subjects

To produce valid generalisable results, clearly define the population you are researching (e.g., people from a specific age range, geographical location, or profession). Ensure that you have enough participants and that they are representative of the population.

Ensuring reliability

Reliability should be considered throughout the data collection process. When you use a tool or technique to collect data, it’s important that the results are precise, stable, and reproducible.

- Apply your methods consistently

Plan your method carefully to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each measurement. This is especially important if multiple researchers are involved.

For example, if you are conducting interviews or observations, clearly define how specific behaviours or responses will be counted, and make sure questions are phrased the same way each time.

- Standardise the conditions of your research

When you collect your data, keep the circumstances as consistent as possible to reduce the influence of external factors that might create variation in the results.

For example, in an experimental setup, make sure all participants are given the same information and tested under the same conditions.

It’s appropriate to discuss reliability and validity in various sections of your thesis or dissertation or research paper. Showing that you have taken them into account in planning your research and interpreting the results makes your work more credible and trustworthy.

| Section | Discuss |

|---|---|

| What have other researchers done to devise and improve methods that are reliable and valid? | |

| How did you plan your research to ensure reliability and validity of the measures used? This includes the chosen sample set and size, sample preparation, external conditions, and measuring techniques. | |

| If you calculate reliability and validity, state these values alongside your main results. | |

| This is the moment to talk about how reliable and valid your results actually were. Were they consistent, and did they reflect true values? If not, why not? | |

| If reliability and validity were a big problem for your findings, it might be helpful to mention this here. |

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Middleton, F. (2022, October 10). Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 17 July 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/reliability-or-validity/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, the 4 types of validity | types, definitions & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, sampling methods | types, techniques, & examples.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Reliability vs. Validity in Research: Types & Examples

When it comes to research, getting things right is crucial. That’s where the concepts of “Reliability vs Validity in Research” come in.

Imagine it like a balancing act – making sure your measurements are consistent and accurate at the same time. This is where test-retest reliability, having different researchers check things, and keeping things consistent within your research plays a big role.

As we dive into this topic, we’ll uncover the differences between reliability and validity, see how they work together, and learn how to use them effectively.

Understanding Reliability vs. Validity in Research

When it comes to collecting data and conducting research, two crucial concepts stand out: reliability and validity.

These pillars uphold the integrity of research findings, ensuring that the data collected and the conclusions drawn are both meaningful and trustworthy. Let’s dive into the heart of the concepts, reliability, and validity, to comprehend their significance in the realm of research truly.

What is reliability?

Reliability refers to the consistency and dependability of the data collection process. It’s like having a steady hand that produces the same result each time it reaches for a task.

In the research context, reliability is all about ensuring that if you were to repeat the same study using the same reliable measurement technique, you’d end up with the same results. It’s like having multiple researchers independently conduct the same experiment and getting outcomes that align perfectly.

Imagine you’re using a thermometer to measure the temperature of the water. You have a reliable measurement if you dip the thermometer into the water multiple times and get the same reading each time. This tells you that your method and measurement technique consistently produce the same results, whether it’s you or another researcher performing the measurement.

What is validity?

On the other hand, validity refers to the accuracy and meaningfulness of your data. It’s like ensuring that the puzzle pieces you’re putting together actually form the intended picture. When you have validity, you know that your method and measurement technique are consistent and capable of producing results aligned with reality.

Think of it this way; Imagine you’re conducting a test that claims to measure a specific trait, like problem-solving ability. If the test consistently produces results that accurately reflect participants’ problem-solving skills, then the test has high validity. In this case, the test produces accurate results that truly correspond to the trait it aims to measure.

In essence, while reliability assures you that your data collection process is like a well-oiled machine producing the same results, validity steps in to ensure that these results are not only consistent but also relevantly accurate.

Together, these concepts provide researchers with the tools to conduct research that stands on a solid foundation of dependable methods and meaningful insights.

Types of Reliability

Let’s explore the various types of reliability that researchers consider to ensure their work stands on solid ground.

High test-retest reliability

Test-retest reliability involves assessing the consistency of measurements over time. It’s like taking the same measurement or test twice – once and then again after a certain period. If the results align closely, it indicates that the measurement is reliable over time. Think of it as capturing the essence of stability.

Inter-rater reliability

When multiple researchers or observers are part of the equation, interrater reliability comes into play. This type of reliability assesses the level of agreement between different observers when evaluating the same phenomenon. It’s like ensuring that different pairs of eyes perceive things in a similar way.

Internal reliability

Internal consistency dives into the harmony among different items within a measurement tool aiming to assess the same concept. This often comes into play in surveys or questionnaires, where participants respond to various items related to a single construct. If the responses to these items consistently reflect the same underlying concept, the measurement is said to have high internal consistency.

Types of validity

Let’s explore the various types of validity that researchers consider to ensure their work stands on solid ground.

Content validity

It delves into whether a measurement truly captures all dimensions of the concept it intends to measure. It’s about making sure your measurement tool covers all relevant aspects comprehensively.

Imagine designing a test to assess students’ understanding of a history chapter. It exhibits high content validity if the test includes questions about key events, dates, and causes. However, if it focuses solely on dates and omits causation, its content validity might be questionable.

Construct validity

It assesses how well a measurement aligns with established theories and concepts. It’s like ensuring that your measurement is a true representation of the abstract construct you’re trying to capture.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity examines how well your measurement corresponds to other established measurements of the same concept. It’s about making sure your measurement accurately predicts or correlates with external criteria.

Differences between reliability and validity in research

Let’s delve into the differences between reliability and validity in research.

| No | Category | Reliability | Validity |

| 01 | Meaning | Focuses on the consistency of measurements over time and conditions. | Concerns about the accuracy and relevance of measurements in capturing the intended concept. |

| 02 | What it assesses | Assesses whether the same results can be obtained consistently from repeated measurements. | Assesses whether measurements truly measure what they are intended to measure. |

| 03 | Assessment methods | Evaluated through test-retest consistency, interrater agreement, and internal consistency. | Assessed through content coverage, construct alignment, and criterion correlation. |

| 04 | Interrelation | A measurement can be reliable (consistent) without being valid (accurate). | A valid measurement is typically reliable, but high reliability doesn’t guarantee validity. |

| 05 | Importance | Ensures data consistency and replicability | Guarantees meaningful and credible results. |

| 06 | Focus | Focuses on the stability and consistency of measurement outcomes. | Focuses on the meaningfulness and accuracy of measurement outcomes. |

| 07 | Outcome | Reproducibility of measurements is the key outcome. | Meaningful and accurate measurement outcomes are the primary goal. |

While both reliability and validity contribute to trustworthy research, they address distinct aspects. Reliability ensures consistent results, while validity ensures accurate and relevant results that reflect the true nature of the measured concept.

Example of Reliability and Validity in Research

In this section, we’ll explore instances that highlight the differences between reliability and validity and how they play a crucial role in ensuring the credibility of research findings.

Example of reliability

Imagine you are studying the reliability of a smartphone’s battery life measurement. To collect data, you fully charge the phone and measure the battery life three times in the same controlled environment—same apps running, same brightness level, and same usage patterns.

If the measurements consistently show a similar battery life duration each time you repeat the test, it indicates that your measurement method is reliable. The consistent results under the same conditions assure you that the battery life measurement can be trusted to provide dependable information about the phone’s performance.

Example of validity

Researchers collect data from a group of participants in a study aiming to assess the validity of a newly developed stress questionnaire. To ensure validity, they compare the scores obtained from the stress questionnaire with the participants’ actual stress levels measured using physiological indicators such as heart rate variability and cortisol levels.

If participants’ scores correlate strongly with their physiological stress levels, the questionnaire is valid. This means the questionnaire accurately measures participants’ stress levels, and its results correspond to real variations in their physiological responses to stress.

Validity assessed through the correlation between questionnaire scores and physiological measures ensures that the questionnaire is effectively measuring what it claims to measure participants’ stress levels.

In the world of research, differentiating between reliability and validity is crucial. Reliability ensures consistent results, while validity confirms accurate measurements. Using tools like QuestionPro enhances data collection for both reliability and validity. For instance, measuring self-esteem over time showcases reliability, and aligning questions with theories demonstrates validity.

QuestionPro empowers researchers to achieve reliable and valid results through its robust features, facilitating credible research outcomes. Contact QuestionPro to create a free account or learn more!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Winning the Internal CX Battles — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jul 16, 2024

Knowledge Management: What it is, Types, and Use Cases

Jul 12, 2024

Response Weighting: Enhancing Accuracy in Your Surveys

Jul 11, 2024

Top 10 Knowledge Management Tools to Enhance Knowledge Flow

Jul 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Validity In Psychology Research: Types & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology research, validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement tool accurately measures what it’s intended to measure. It ensures that the research findings are genuine and not due to extraneous factors.

Validity can be categorized into different types based on internal and external validity .

The concept of validity was formulated by Kelly (1927, p. 14), who stated that a test is valid if it measures what it claims to measure. For example, a test of intelligence should measure intelligence and not something else (such as memory).

Internal and External Validity In Research

Internal validity refers to whether the effects observed in a study are due to the manipulation of the independent variable and not some other confounding factor.

In other words, there is a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables .

Internal validity can be improved by controlling extraneous variables, using standardized instructions, counterbalancing, and eliminating demand characteristics and investigator effects.

External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other settings (ecological validity), other people (population validity), and over time (historical validity).

External validity can be improved by setting experiments more naturally and using random sampling to select participants.

Types of Validity In Psychology

Two main categories of validity are used to assess the validity of the test (i.e., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.): Content and criterion.

- Content validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement represents all aspects of the intended content domain. It assesses whether the test items adequately cover the topic or concept.

- Criterion validity assesses the performance of a test based on its correlation with a known external criterion or outcome. It can be further divided into concurrent (measured at the same time) and predictive (measuring future performance) validity.

Face Validity

Face validity is simply whether the test appears (at face value) to measure what it claims to. This is the least sophisticated measure of content-related validity, and is a superficial and subjective assessment based on appearance.

Tests wherein the purpose is clear, even to naïve respondents, are said to have high face validity. Accordingly, tests wherein the purpose is unclear have low face validity (Nevo, 1985).

A direct measurement of face validity is obtained by asking people to rate the validity of a test as it appears to them. This rater could use a Likert scale to assess face validity.

For example:

- The test is extremely suitable for a given purpose

- The test is very suitable for that purpose;

- The test is adequate

- The test is inadequate

- The test is irrelevant and, therefore, unsuitable

It is important to select suitable people to rate a test (e.g., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.). For example, individuals who actually take the test would be well placed to judge its face validity.

Also, people who work with the test could offer their opinion (e.g., employers, university administrators, employers). Finally, the researcher could use members of the general public with an interest in the test (e.g., parents of testees, politicians, teachers, etc.).

The face validity of a test can be considered a robust construct only if a reasonable level of agreement exists among raters.

It should be noted that the term face validity should be avoided when the rating is done by an “expert,” as content validity is more appropriate.

Having face validity does not mean that a test really measures what the researcher intends to measure, but only in the judgment of raters that it appears to do so. Consequently, it is a crude and basic measure of validity.

A test item such as “ I have recently thought of killing myself ” has obvious face validity as an item measuring suicidal cognitions and may be useful when measuring symptoms of depression.

However, the implication of items on tests with clear face validity is that they are more vulnerable to social desirability bias. Individuals may manipulate their responses to deny or hide problems or exaggerate behaviors to present a positive image of themselves.

It is possible for a test item to lack face validity but still have general validity and measure what it claims to measure. This is good because it reduces demand characteristics and makes it harder for respondents to manipulate their answers.

For example, the test item “ I believe in the second coming of Christ ” would lack face validity as a measure of depression (as the purpose of the item is unclear).

This item appeared on the first version of The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and loaded on the depression scale.

Because most of the original normative sample of the MMPI were good Christians, only a depressed Christian would think Christ is not coming back. Thus, for this particular religious sample, the item does have general validity but not face validity.

Construct Validity

Construct validity assesses how well a test or measure represents and captures an abstract theoretical concept, known as a construct. It indicates the degree to which the test accurately reflects the construct it intends to measure, often evaluated through relationships with other variables and measures theoretically connected to the construct.

Construct validity was invented by Cronbach and Meehl (1955). This type of content-related validity refers to the extent to which a test captures a specific theoretical construct or trait, and it overlaps with some of the other aspects of validity

Construct validity does not concern the simple, factual question of whether a test measures an attribute.

Instead, it is about the complex question of whether test score interpretations are consistent with a nomological network involving theoretical and observational terms (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955).

To test for construct validity, it must be demonstrated that the phenomenon being measured actually exists. So, the construct validity of a test for intelligence, for example, depends on a model or theory of intelligence .

Construct validity entails demonstrating the power of such a construct to explain a network of research findings and to predict further relationships.

The more evidence a researcher can demonstrate for a test’s construct validity, the better. However, there is no single method of determining the construct validity of a test.

Instead, different methods and approaches are combined to present the overall construct validity of a test. For example, factor analysis and correlational methods can be used.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity is a subtype of construct validity. It assesses the degree to which two measures that theoretically should be related are related.

It demonstrates that measures of similar constructs are highly correlated. It helps confirm that a test accurately measures the intended construct by showing its alignment with other tests designed to measure the same or similar constructs.

For example, suppose there are two different scales used to measure self-esteem:

Scale A and Scale B. If both scales effectively measure self-esteem, then individuals who score high on Scale A should also score high on Scale B, and those who score low on Scale A should score similarly low on Scale B.

If the scores from these two scales show a strong positive correlation, then this provides evidence for convergent validity because it indicates that both scales seem to measure the same underlying construct of self-esteem.

Concurrent Validity (i.e., occurring at the same time)

Concurrent validity evaluates how well a test’s results correlate with the results of a previously established and accepted measure, when both are administered at the same time.

It helps in determining whether a new measure is a good reflection of an established one without waiting to observe outcomes in the future.

If the new test is validated by comparison with a currently existing criterion, we have concurrent validity.

Very often, a new IQ or personality test might be compared with an older but similar test known to have good validity already.

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity assesses how well a test predicts a criterion that will occur in the future. It measures the test’s ability to foresee the performance of an individual on a related criterion measured at a later point in time. It gauges the test’s effectiveness in predicting subsequent real-world outcomes or results.

For example, a prediction may be made on the basis of a new intelligence test that high scorers at age 12 will be more likely to obtain university degrees several years later. If the prediction is born out, then the test has predictive validity.

Cronbach, L. J., and Meehl, P. E. (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin , 52, 281-302.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1943). Manual for the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory . New York: Psychological Corporation.

Kelley, T. L. (1927). Interpretation of educational measurements. New York : Macmillan.

Nevo, B. (1985). Face validity revisited . Journal of Educational Measurement , 22(4), 287-293.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 18, Issue 3

- Validity and reliability in quantitative studies

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Roberta Heale 1 ,

- Alison Twycross 2

- 1 School of Nursing, Laurentian University , Sudbury, Ontario , Canada

- 2 Faculty of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to : Dr Roberta Heale, School of Nursing, Laurentian University, Ramsey Lake Road, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada P3E2C6; rheale{at}laurentian.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102129

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Evidence-based practice includes, in part, implementation of the findings of well-conducted quality research studies. So being able to critique quantitative research is an important skill for nurses. Consideration must be given not only to the results of the study but also the rigour of the research. Rigour refers to the extent to which the researchers worked to enhance the quality of the studies. In quantitative research, this is achieved through measurement of the validity and reliability. 1

- View inline

Types of validity

The first category is content validity . This category looks at whether the instrument adequately covers all the content that it should with respect to the variable. In other words, does the instrument cover the entire domain related to the variable, or construct it was designed to measure? In an undergraduate nursing course with instruction about public health, an examination with content validity would cover all the content in the course with greater emphasis on the topics that had received greater coverage or more depth. A subset of content validity is face validity , where experts are asked their opinion about whether an instrument measures the concept intended.

Construct validity refers to whether you can draw inferences about test scores related to the concept being studied. For example, if a person has a high score on a survey that measures anxiety, does this person truly have a high degree of anxiety? In another example, a test of knowledge of medications that requires dosage calculations may instead be testing maths knowledge.

There are three types of evidence that can be used to demonstrate a research instrument has construct validity:

Homogeneity—meaning that the instrument measures one construct.

Convergence—this occurs when the instrument measures concepts similar to that of other instruments. Although if there are no similar instruments available this will not be possible to do.

Theory evidence—this is evident when behaviour is similar to theoretical propositions of the construct measured in the instrument. For example, when an instrument measures anxiety, one would expect to see that participants who score high on the instrument for anxiety also demonstrate symptoms of anxiety in their day-to-day lives. 2

The final measure of validity is criterion validity . A criterion is any other instrument that measures the same variable. Correlations can be conducted to determine the extent to which the different instruments measure the same variable. Criterion validity is measured in three ways:

Convergent validity—shows that an instrument is highly correlated with instruments measuring similar variables.

Divergent validity—shows that an instrument is poorly correlated to instruments that measure different variables. In this case, for example, there should be a low correlation between an instrument that measures motivation and one that measures self-efficacy.

Predictive validity—means that the instrument should have high correlations with future criterions. 2 For example, a score of high self-efficacy related to performing a task should predict the likelihood a participant completing the task.

Reliability

Reliability relates to the consistency of a measure. A participant completing an instrument meant to measure motivation should have approximately the same responses each time the test is completed. Although it is not possible to give an exact calculation of reliability, an estimate of reliability can be achieved through different measures. The three attributes of reliability are outlined in table 2 . How each attribute is tested for is described below.

Attributes of reliability

Homogeneity (internal consistency) is assessed using item-to-total correlation, split-half reliability, Kuder-Richardson coefficient and Cronbach's α. In split-half reliability, the results of a test, or instrument, are divided in half. Correlations are calculated comparing both halves. Strong correlations indicate high reliability, while weak correlations indicate the instrument may not be reliable. The Kuder-Richardson test is a more complicated version of the split-half test. In this process the average of all possible split half combinations is determined and a correlation between 0–1 is generated. This test is more accurate than the split-half test, but can only be completed on questions with two answers (eg, yes or no, 0 or 1). 3

Cronbach's α is the most commonly used test to determine the internal consistency of an instrument. In this test, the average of all correlations in every combination of split-halves is determined. Instruments with questions that have more than two responses can be used in this test. The Cronbach's α result is a number between 0 and 1. An acceptable reliability score is one that is 0.7 and higher. 1 , 3

Stability is tested using test–retest and parallel or alternate-form reliability testing. Test–retest reliability is assessed when an instrument is given to the same participants more than once under similar circumstances. A statistical comparison is made between participant's test scores for each of the times they have completed it. This provides an indication of the reliability of the instrument. Parallel-form reliability (or alternate-form reliability) is similar to test–retest reliability except that a different form of the original instrument is given to participants in subsequent tests. The domain, or concepts being tested are the same in both versions of the instrument but the wording of items is different. 2 For an instrument to demonstrate stability there should be a high correlation between the scores each time a participant completes the test. Generally speaking, a correlation coefficient of less than 0.3 signifies a weak correlation, 0.3–0.5 is moderate and greater than 0.5 is strong. 4

Equivalence is assessed through inter-rater reliability. This test includes a process for qualitatively determining the level of agreement between two or more observers. A good example of the process used in assessing inter-rater reliability is the scores of judges for a skating competition. The level of consistency across all judges in the scores given to skating participants is the measure of inter-rater reliability. An example in research is when researchers are asked to give a score for the relevancy of each item on an instrument. Consistency in their scores relates to the level of inter-rater reliability of the instrument.

Determining how rigorously the issues of reliability and validity have been addressed in a study is an essential component in the critique of research as well as influencing the decision about whether to implement of the study findings into nursing practice. In quantitative studies, rigour is determined through an evaluation of the validity and reliability of the tools or instruments utilised in the study. A good quality research study will provide evidence of how all these factors have been addressed. This will help you to assess the validity and reliability of the research and help you decide whether or not you should apply the findings in your area of clinical practice.

- Lobiondo-Wood G ,

- Shuttleworth M

- ↵ Laerd Statistics . Determining the correlation coefficient . 2013 . https://statistics.laerd.com/premium/pc/pearson-correlation-in-spss-8.php

Twitter Follow Roberta Heale at @robertaheale and Alison Twycross at @alitwy

Competing interests None declared.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- How it works

Reliability and Validity – Definitions, Types & Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023