Our use of cookies

We use necessary cookies to make our site work. We'd also like to set optional cookies to help us measure web traffic and report on campaigns.

We won't set optional cookies unless you enable them.

Cookie settings

Mental Health

- Entry year 2024

- Duration Part time 4 - 7 years

An international first, the PhD in Mental Health meets the needs of those wishing to gain a deep and critical insight into mental health theory, research and practice and to develop or enhance research skills whilst fulfilling their existing responsibilities. The programme is offered part-time and combines innovative distance learning with face-to-face teaching at an annual autumn Academy held in Lancaster.

The programme brings together the theory and practice of mental health, including psychological models of psychological disorders, evidence-based interventions and current priorities for mental health. Whether you are based within a healthcare setting, local government, education, research or management, the PhD in Mental Health is your chance to work with world-leading academics on the production of a thesis that makes an original contribution to knowledge within your area of professional practice.

This part-time, flexible doctorate runs over a minimum of four and a maximum of seven years. The programme begins with a compulsory five-day Induction Academy in Lancaster. Each of the subsequent academic years start with a compulsory three-day autumn Academy, while the rest of the course is delivered via e-learning. Attendance at the annual academies is compulsory until students have been confirmed on the PhD programme

Years 1 and 2 consist of taught modules delivered online. In Year 1 students take a specialist module that covers the theory and practice of mental health followed by a module on research philosophy and a module on research design. Year 2 modules may include: Systematic Reviews, Data Analysis, Research Design and Practical Research Ethics.

From Year 3 onwards, students undertake an independent research study , which will conclude with the submission of a thesis that makes an original contribution to knowledge. The research project will be supervised from the University but undertaken in students’ own location or workplace. Supervision meetings take place using video conferencing software such as Skype. During the annual autumn Academy students meet with supervisors face to face.

A number of mental health research groups work from Lancaster University’s prestigious Division of Health Research. For example, the Spectrum Centre, which has attracted more than £6m in funding since its launch, is the only specialist research centre in the UK dedicated to translational research into the psychosocial aspects of bipolar disorder and associated conditions (including recurrent depression, anxiety, and psychosis), as well as developments in their treatment. Other staff research interests include mental health in people with chronic physical conditions or difficulties and ensuring positive mental health among socially marginalised groups.

Our close links to NHS mental health services in the North West of England and the voluntary sector, both regionally and nationally, combine with the current research interests of staff to inform the content of our modules. Service users will also be actively involved in the delivery of the taught component of your Doctorate.

Your department

- Division of Health Research Faculty of Health and Medicine

- Telephone +44 (0)1524 592032

Mental Health Research at Lancaster University

Professor Steve Jones introduces Mental Health research at Lancaster University, and our multi-facetted approach to understanding mental health. He discusses how the Faculty's research influences practice, changing the debate around mental health and ultimately improving outcomes.

Entry requirements

Academic requirements.

2:1 Hons degree (UK or equivalent) in an appropriate subject and relevant work experience.

We may also consider non-standard applicants, please contact us for information.

If you have studied outside of the UK, we would advise you to check our list of international qualifications before submitting your application.

Additional Requirements

As part of your application you will also need to provide a viable research proposal. Guidance for writing a research proposal can be found on our writing a research proposal webpage.

English Language Requirements

We may ask you to provide a recognised English language qualification, dependent upon your nationality and where you have studied previously.

We normally require an IELTS (Academic) Test with an overall score of at least 6.5, and a minimum of 6.0 in each element of the test. We also consider other English language qualifications .

Contact: Admissions Team +44 (0) 1524 592032 or email [email protected]

Course structure

You will study a range of modules as part of your course, some examples of which are listed below.

Information contained on the website with respect to modules is correct at the time of publication, but changes may be necessary, for example as a result of student feedback, Professional Statutory and Regulatory Bodies' (PSRB) requirements, staff changes, and new research. Not all optional modules are available every year.

The aim of this module is to provide students with an advanced introduction to the methods commonly used in health research. Students will gain knowledge and understanding of:

- How to use Moodle for distance learning and engage with peers and staff online

- Using the library as a distance learning student

- How to search the literature

- Using End Note

- How to synthesise evidence

- Standards of academic writing

- The nature of plagiarism and how to reference source material correctly

- Theoretical perspectives in health research

- The practical process of conducting research

- How to formulate appropriate questions and hypotheses

- How to choose appropriate methodology

- Quantitative and qualitative research method

- Research ethics

- Disseminating and implementing research into practice

- Programme-specific research.

e-learning distance module

Autumn Term (weeks 1-10, October – December)

Credits: 30

Mode of assessment : 3000 word essay (75%) and a poster (25%).

This module is an introduction to current topics and issues in mental health, covering theory (mechanisms underlying mental health), practice (psychosocial approaches to treating mental health problems), contemporary issues in mental health, and up-to-date research relating to these important topic areas.

Deadline: January

Spring Term (weeks 1-10, January-March)

Mode of assessment : 5000 word essay

This module explores the philosophical underpinnings of research. It begins with an introduction to epistemology, i.e. the philosophical basis of knowledge and its development. It then considers the influence of different epistemological bases on research methodology and explores the role of theory and theoretical frameworks in the research process. It also examines the nature of the knowledge that underpins evidence-based policy and practice and introduces the fundamental principles of ethics.

Deadline: April

Sunmer Term (weeks 1-10, April-June)

Mode of assessment : 5000 word assignment consisting of two 2500 word components

This module introduces a range of methods used in health research. The focus is on justifying research design choices rather than practical skills in data analysis. The starting point is the development of meaningful and feasible research questions. The module then introduces a range of quantitative research designs and quantitative approaches to data collection. Next, the module looks at qualitative research designs and their relation to different epistemological positions. How to integrate quantitative and qualitative methods into mixed methods research is being discussed next. The module also explores issues such as sampling and quality across different research designs.

Deadline: July

Spring term (weeks 1-10, January-March)

Mode of assessment : two pieces of written work (Qualitative data analysis, 2500 words; Quantitative data analysis, 2500 words)

This module is an introduction to the theory and practice of qualitative and quantitative data analysis. The module consists of two distinct parts: qualitative data analysis and quantitative data analysis. Within each part, there will be an option to take an introductory or an advanced unit.

The introductory quantitative unit covers data management and descriptive analyses and introduces students to inferential testing in general and statistical tests for comparisons between groups specifically. The advanced quantitative unit covers linear regression as well as regression methods for categorical dependent variables and longitudinal data before exploring quasi-experimental methods for policy evaluation and finally providing an opportunity to discuss more specific regression methods such count data models or duration analysis.

The introductory qualitative unit focusses on the technique of thematic analysis, a highly flexible approach and useful foundation for researchers new to qualitative data analysis. The unit takes students through the stage of a qualitative data analysis: sorting and organising qualitative data, interrogating qualitative data, interpreting the data and finally writing accounts of qualitative data. The advanced qualitative unit introduces students to alternative techniques such as narrative analysis or discourse analysis.

Summer Term (weeks 1-10, April-June)

Mode of assessment : A written assignment that includes: a) a 4000 word research proposal and b) a completed FHMREC ethics application form and supporting documents.

This module completes the taught phase of Blended Learning PhD programmes. It enables students to put everything they have learned so far together and produce a research proposal that will provide the basis for the research phase of the programme.

The first part of the module – research design – starts by discussing the components of a research proposal according to different epistemologies and research methods. It then takes students through the process of developing their own proposal, starting with the topic and epistemological framework, through to the study design and data collection methods and finally the practical details.

The second part of the module – practical research ethics – teaches students how to think about their research proposal from an ethical perspective. It covers ethical guidelines and teaches students how to identify the purpose of a guideline, to enable them to translate their proposal into an ethical review application. Finally, students will prepare a practice research ethics application using the FHMREC ethics application form.

Autumn term (weeks 1-10, October-December)

Mode of assessment : 5000 word assignment

This module provides an introduction to the principles and components of systematic reviewing. It takes students through the key steps of a systematic review. The starting point of the module is the construction of an appropriate review question. Next, the module discusses the (iterative) process of creating a search strategy that successfully identifies all relevant literature. The module then moves on to selecting appropriate methodological quality criteria, enabling students to develop their skills in critically appraising studies. After discussing how to prepare a data extraction form the module introduces a key component of a systematic review: synthesising the evidence. Finally, the module will teach students how to put everything together in a systematic review protocol.

Fees and funding

Home Fee £4,350

International Fee £11,340

General fees and funding information

There may be extra costs related to your course for items such as books, stationery, printing, photocopying, binding and general subsistence on trips and visits. Following graduation, you may need to pay a subscription to a professional body for some chosen careers.

Specific additional costs for studying at Lancaster are listed below.

College fees

Lancaster is proud to be one of only a handful of UK universities to have a collegiate system. Every student belongs to a college, and all students pay a small College Membership Fee which supports the running of college events and activities. Students on some distance-learning courses are not liable to pay a college fee.

For students starting in 2023 and 2024, the fee is £40 for undergraduates and research students and £15 for students on one-year courses. Fees for students starting in 2025 have not yet been set.

Computer equipment and internet access

To support your studies, you will also require access to a computer, along with reliable internet access. You will be able to access a range of software and services from a Windows, Mac, Chromebook or Linux device. For certain degree programmes, you may need a specific device, or we may provide you with a laptop and appropriate software - details of which will be available on relevant programme pages. A dedicated IT support helpdesk is available in the event of any problems.

The University provides limited financial support to assist students who do not have the required IT equipment or broadband support in place.

For most taught postgraduate applications there is a non-refundable application fee of £40. We cannot consider applications until this fee has been paid, as advised on our online secure payment system. There is no application fee for postgraduate research applications.

For some of our courses you will need to pay a deposit to accept your offer and secure your place. We will let you know in your offer letter if a deposit is required and you will be given a deadline date when this is due to be paid.

The fee that you pay will depend on whether you are considered to be a home or international student. Read more about how we assign your fee status .

If you are studying on a programme of more than one year’s duration, tuition fees are reviewed annually and are not fixed for the duration of your studies. Read more about fees in subsequent years .

Similar courses

Health studies.

- Clinical Psychology DClinPsy

- Dementia Studies PhD

- Health Data Science MSc

- Health Data Science PhD

- Health Economics and Policy MSc

- Health Economics and Policy PhD

- Health Research PhD

- Organisational Health and Well-Being PhD

- Palliative Care PhD

- Public Health PhD

Take an innovative approach to distance learning combining interactive lectures, webinars and online collaboration, group work and self-directed study.

Work with world-leading academics to make an original contribution to your area of professional practice.

Benefit from an international peer group that could include educators, mental health practitioners and policy-makers.

Studying by blended learning

The PhD in Mental Health is offered part-time via blended learning . Teaching and research activities are carried out through a combination of face-to-face and online interaction, allowing you to undertake the majority of study from your own location whilst fulfilling your existing responsibilities. You will benefit from being part of a UK and internationally-based peer group working across a range of sectors.

Face-to-face interactions take place at an annual residential autumn Academy while taught modules are delivered via distance learning using our virtual learning environment and include discussion forums, collaborative digital spaces and video conferencing. All students have access to a hub space that facilitates interaction with their cohort and with students on related programmes, creating a virtual information space that’s also sociable. An academic tutor will support you during the taught phase and two supervisors provide you with support in the research phase.

The Division of Health Research

The Division of Health Research have been offering blended learning postgraduate programmes since 2010. We have many successful graduates and currently around 200 continuing students on a range of programmes who have benefited in progressing their careers from the high quality postgraduate education we provide.

Our Research in Mental Health

Our mental health research covers a wide range of research areas and activities, including bipolar disorder and related conditions, chronic illness and care approaches.

The Spectrum Centre

The Spectrum Centre is the only specialist research centre in the UK dedicated to translational research into the psychosocial aspects of bipolar disorder and associated conditions.

Athena SWAN: Gender Equality at Lancaster

We hold the Athena SWAN Silver Award, recognising our commitment to advancing the careers of women in higher education and research.

Important Information

The information on this site relates primarily to 2024/2025 entry to the University and every effort has been taken to ensure the information is correct at the time of publication.

The University will use all reasonable effort to deliver the courses as described, but the University reserves the right to make changes to advertised courses. In exceptional circumstances that are beyond the University’s reasonable control (Force Majeure Events), we may need to amend the programmes and provision advertised. In this event, the University will take reasonable steps to minimise the disruption to your studies. If a course is withdrawn or if there are any fundamental changes to your course, we will give you reasonable notice and you will be entitled to request that you are considered for an alternative course or withdraw your application. You are advised to revisit our website for up-to-date course information before you submit your application.

More information on limits to the University’s liability can be found in our legal information .

Our Students’ Charter

We believe in the importance of a strong and productive partnership between our students and staff. In order to ensure your time at Lancaster is a positive experience we have worked with the Students’ Union to articulate this relationship and the standards to which the University and its students aspire. View our Charter and other policies .

Why Lancaster?

League tables and reputation

A highly-ranked university with a global reputation.

Colleges and community

Your college will be your home away from home.

Careers and employability

Career support for our students through university and beyond.

Student life

Lancaster has so much to offer. On our campus, in our city and in our community, you’ll find your place – whoever you are.

Where is Lancaster?

Lancaster is easy to get to and surrounded by natural beauty.

The campus and the city

Our campus and the surrounding area is a great place to call home.

Your global experience

Build your global community on campus and around the world.

Wellbeing and support

Services to help you fulfil your potential at Lancaster.

Alternatively, use our A–Z index

Attend an open day

PhD/MPhil Mental Health / Programme details

Year of entry: 2024

- View full page

Programme description

Our PhD/MPhil Mental Health programme enables you to undertake a research project that will improve understanding of Mental Health.

Our postgraduate research programmes in mental health are based on individually tailored projects. Applicants are specifically matched with a primary academic supervisor according to their research interest and background.

All of our postgraduate research students have more than one supervisor, and our dynamic multidisciplinary supervisory teams typically cover a wide and diverse range of academic disciplines beyond mental health and psychology, including nursing, pharmacy, epidemiology and biostatics, informatics, health economics, sociology and qualitative research.

Our academics have internationally outstanding knowledge and expertise in conducting research studies in mental health across the life course. Particular strengths include:

- severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (including the prodromal stages of these conditions);

- depression;

- anxiety disorders;

- personality disorders;

- autism spectrum disorder;

- attachment disorders;

- self-harm and suicide;

- homicide and other forms of interpersonal violence;

- forensic mental health;

- neurobiological and imaging studies;

- mental health epidemiology;

Special features

Training and development

All of our postgraduate researchers attend the Doctoral Academy Training Programme delivered by the Researcher Development team . The programme provides key transferable skills and equips our postgraduate researchers with the tools to progress beyond their research degree into influential positions within academia, industry and consultancy. The emphasis is on enhancing skills critical to developing early-stage researchers and professionals, whether they relate to effective communication, disseminating research findings and project management skills.

Teaching and learning

Applicants are specifically matched with a Primary Supervisor and individual project based on their research interests and background.

International applicants interested in this research area can also consider our PhD programme with integrated teaching certificate .

This unique programme will enable you to gain a Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching and Learning, whilst also carrying out independent research on your chosen project.

Scholarships and bursaries

Funded programmes and projects are promoted throughout the year. Funding is available through UK Research Councils, charities and industry. We also have other internal awards and scholarships for the most outstanding applicants from within the UK and overseas.

For more information on available the types of funding we have available, please visit the funded programmes and funding opportunities pages.

What our students say

Disability support.

Welcome to the Midlands Mental Health and Neurosciences PhD Programme for Healthcare Professionals

The Midlands hosts the most innovative centres in mental health and neurosciences (MH&N), including digital mental health, clinical trials, neuroimaging, and epidemiology, serving an area of huge clinical need.

The Midlands Mental Health & Neurosciences PhD Programme is led by the University of Nottingham, in collaboration with University of Birmingham, University of Leicester, and University of Warwick, and our local NHS Trusts in the Midlands.

The Programme

In a research environment that is dynamic, socially inclusive, and supportive, our Doctoral Training Programme (DTP) will develop an excellent, multidisciplinary, multi-professional researchers and an inter-sectoral research Midlands hub, facilitating adult learning, developing research and leadership skills, independent and critical thinking, and sharing of ideas, and teamwork.

Our PhD scholars will undertake excellent challenge-led research encompassing MH&N discovery science to translational and applied health research, covering the human lifespan and taking a bio-psycho-social approach, commensurate with the complex presentations, experiences, interventions, and impact of mental ill-health.

Our PhDs are funded by the generous contribution of Wellcome in collaboration with our DTP universities.

- NHS salary for three years (based on current pay) – Employing Trusts will be paid this money to backfill the PhD student’s time on the Programme.*

- Home (UK) rate tuition fees for three years

- Generous research costs

- Generous funds for additional training

- Travel costs for research

- PhD students are permitted to undertake up to 0.2 FTE clinical work to maintain their clinical skills, which will be paid for by the Programme

*Funding for salaries is based on average NHS pay bands for different healthcare professionals, which Wellcome has used to fund this programme. We may be able to accommodate funding above the average pay bands, but this will be dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

Our vision, with inclusivity at its core, is to develop the next generation of multi-skilled research leaders amongst healthcare professionals from diverse cultural backgrounds and professions to conduct excellent research and advance knowledge in MH&N, paving the way to better patient, family, and carer care; community empowerment; and social development.

Develop the next generation of multidisciplinary clinical academics in mental health & neurosciences (MH&N)

Conduct and disseminate world-leading research

Create and sustain an ambitious Midlands-based, internationally connected, compassionate clinical-academic ecosystem, collaborating to address the key contemporary mental health challenges

Our Guiding Principles

High quality research.

We will support our scholars to undertake high-quality research, that is going to answer the key questions the scholars seek to address. Through rigorous peer review and links with experts in the field nationally and internationally, we will ensure that the PhD projects are of the highest quality.

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI)

We are committed to Advance HE’s Guiding Principles of the Race Equality Charter and Athena Swan Charter , and strive to follow their Good Practice Initiatives . We strongly encourage applications from those groups who are underrepresented in different healthcare professions and those with lived experience of mental health difficulties.

Improvement and innovation through continuous evaluation

We have several years of experience running different DTPs, but we believe in self-improvement and we want to ensure that the PhD programme is tailored to the needs to our PhD scholars. Through regular consultation with our PhD scholars, supervisors, and our PPI members, we will learn about what is considered good practice and where we need to do better.

Interdisciplinarity and Team Science

Our scholars will be addressing in their research large and complex MH&N challenges, which requires teamwork and input from different professional groups and experts in different research methods. We strongly encourage interdisciplinarity. Scholars will have the opportunity to develop their skills and research projects with the input from experts from multiple disciplines, thereby enabling innovation within their own healthcare professional group. Our Team Science approach ensures that our PhD scholars get the benefits of working as part of a team, where the contributions of each member of the team are recognised.

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

PPI is core to our DTP and to all our scholars’ projects. PPI offers researchers:

- An improved understanding of what is important to patients and the public about a specific area/topic

- An alternative point of view

- An early indication of whether people would want to participate in the study (or how to improve the experience of participating in a study), and

- Guidance regarding dissemination of their research findings.

PPI will be expected at every stage of the scholar’s PhD journey, from the conceptualisation of the project to the dissemination plans. Scholars may also have a PPI member as part of their advisory team.

- Accessibility Tools

- Current Students

- Postgraduate

- Postgraduate Research Programmes

- School of Health and Social Care Postgraduate Research Courses

Mental Health, Ph.D. / M.Phil.

- An introduction to postgraduate study

- Postgraduate Taught Courses

- Postgraduate scholarships and bursaries

- Contact the Postgrad Admissions team

- Scholarships and Bursaries

- Research projects

- Postgraduate Research Programmes coming soon

- How to apply for your Postgraduate Research programme

- School of Aerospace, Civil, Electrical and Mechanical Engineering Research Courses

- School of Biosciences, Geography and Physics Postgraduate Research Courses

- School of Culture and Communication Postgraduate Research Courses

- School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Postgraduate Research Courses

- Gerontology and Ageing Studies, PhD/MPhil

- Health and Wellbeing, MSc by Research

- Health Economics, PhD/MPhil/MSc by Research

- Health Policy, PhD/MPhil

- Health Sciences, PhD/MPhil

- Healthcare Management, PhD/MPhil

- Mental Health, PhD/MPhil

- Nursing, PhD/MPhil

- Public Health, PhD/MPhil

- Social Work and Social Care, PhD/MPhil

- Children and Young People, PhD/MPhil

- School of Law Postgrad Research Courses

- School of Management Postgraduate Research Courses

- School of Mathematics and Computer Science Postgraduate Research Courses

- Medical School Postgraduate Research Courses

- School of Psychology Postgraduate Research Courses

- School of Social Sciences Postgraduate Research Courses

- Fees and Funding

- How to Apply For Your Postgraduate Course

- Postgraduate Fees and Funding

- Postgraduate Open Days

- Apply Online

- Postgraduate Careers and Employability

- Accommodation

- Postgraduate Study Video Hub

- Why study at Swansea

- Academi Hywel Teifi

- Student life

- Student Services

- Information for parents and advisors

- Enrolment, Arrivals and Welcome

- Postgraduate Enquiry

- Postgraduate programme changes

- Meet our postgraduate students

- Postgraduate Prospectus

- Fast-track for current students

Are you a UK or International Student?

Develop and evaluate effective evidence-based mental health services, key course details, course overview.

Start dates: 1st October, 1st January, 1st April, 1st July.

Developing and evaluating effective evidence-based mental health services to support people at some of the most challenging times of their lives depends on high-quality research.

Studying for a PhD in Mental Health will give you the opportunity to pursue your own personal or professional research interests in this vital field while contributing to new ways of thinking about mental health care, services, and policy.

Over the course of your studies, you will develop and enhance transferable skills such as problem-solving, project management, and critical thinking that are valued in any professional setting.

As a student at our School of Health and Social Care, you will benefit from a dynamic and supportive research environment with many opportunities to make connections across disciplines and develop links with organisations and policymakers both in the UK and abroad. As such, you can be confident that your research will inform and be informed by the wider health and social care environment.

According to the most recent Research Excellence Framework in 2014-2021, over 75% of the research carried out at the school was of international or world-leading quality.

Currently, students are looking at evidence-based practices in mental health (in particular early intervention services), care co-ordination in forensic mental health care and the influence of service user participation in professional role development.

Recent research funding and collaboration partners include:

- Welsh Government

- Public Health Wales

- European Union

- Amgen Europe

- Ministry of Defence

- GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals

- British Medical Association

- National Institute for Social Care and Health Research

- Astrazeneca

- The Wellcome Trust.

You will be joining a university that was named ‘University of the Year’ and ‘Postgraduate’ runner up in the What Uni Student Choice Awards 2019.

Entry Requirements

Qualifications MPhil: Applicants for MPhil must normally hold an undergraduate degree at 2.1 level (or Non-UK equivalent as defined by Swansea University). See - Country-specific Information for European Applicants 2019 and Country-specific Information for International Applicants 2019 .

PhD : Applicants for PhD must normally hold an undergraduate degree at 2.1 level and a master’s degree. Alternatively, applicants with a UK first class honours degree (or Non-UK equivalent as defined by Swansea University) not holding a master’s degree, will be considered on an individual basis. See - Country-specific Information for European Applicants 2019 and Country-specific Information for International Applicants 2019 .

English Language IELTS 6.5 Overall (with no individual component below 6.5) or Swansea University recognised equivalent. Full details of our English Language policy, including certificate time validity, can be found here.

As well as academic qualifications, Admissions decisions may be based on other factors, including (but not limited to): the standard of the research synopsis/proposal, performance at interview, intensity of competition for limited places, and relevant professional experience.

Reference Requirement

As standard, two references are required before we can progress applications to the College/School research programme Admissions Tutor for consideration.

Applications received without two references attached are placed on hold, pending receipt of the outstanding reference(s). Please note that any protracted delay in receiving the outstanding reference(s) may result in the need to defer your application to a later potential start point/entry month, than what you initially listed as your preferred start option.

You may wish to consider contacting your referee(s) to assist in the process of obtaining the outstanding reference(s) or alternatively, hold submission of application until references are sourced. Please note that it is not the responsibility of the University Admissions Office to obtain missing reference(s) after our initial email is sent to your nominated referee(s), requesting a reference(s) on your behalf.

The reference can take the form of a letter on official headed paper, or via the University’s standard reference form. Click this link to download the university reference form .

Alternatively, referees can email a reference from their employment email account, please note that references received via private email accounts, (i.e. Hotmail, Yahoo, Gmail) cannot be accepted.

References can be submitted to [email protected] .

How you are Supervised

Find out more about some of the academic staff supervising theses in this area:

Professor Michael Coffey

Dr Ian Beech

Dr Julia Terry

Welsh Provision

Tuition fees, ph.d. 3 year full time, ph.d. 6 year part time, m.phil. 2 year full time, m.phil. 4 year part time.

Tuition fees for years of study after your first year are subject to an increase of 3%.

You can find further information of your fee costs on our tuition fees page .

You may be eligible for funding to help support your study. To find out about scholarships, bursaries and other funding opportunities that are available please visit the University's scholarships and bursaries page .

International students and part-time study: It may be possible for some students to study part-time under the Student Visa route. However, this is dependent on factors relating to the course and your individual situation. It may also be possible to study with us if you are already in the UK under a different visa category (e.g. Tier 1 or 2, PBS Dependant, ILR etc.). Please visit the University information on Visas and Immigration for further guidance and support.

Current students: You can find further information of your fee costs on our tuition fees page .

Funding and Scholarships

You may be eligible for funding to help support your study.

Government funding is now available for Welsh, English and EU students starting eligible postgraduate research programmes at Swansea University. To find out more, please visit our postgraduate loans page.

To find out about scholarships, bursaries and other funding opportunities that are available please visit the University's scholarships and bursaries page.

Academi Hywel Teifi at Swansea University and the Coleg Cymraeg Cenedlaethol offer a number of generous scholarships and bursaries for students who wish to study through the medium of Welsh or bilingually. For further information about the opportunities available to you, visit the Academi Hywel Teifi Scholarships and Bursaries page.

Additional Costs

Access to your own digital device/the appropriate IT kit will be essential during your time studying at Swansea University. Access to wifi in your accommodation will also be essential to allow you to fully engage with your programme. See our dedicated webpages for further guidance on suitable devices to purchase, and for a full guide on getting your device set up .

You may face additional costs while at university, including (but not limited to):

- Travel to and from campus

- Printing, photocopying, binding, stationery and equipment costs (e.g. USB sticks)

- Purchase of books or texts

- Gowns for graduation ceremonies

How to Apply

Details of the application process for research degrees are available here , and you can apply online and track your application status at www.swansea.ac.uk/applyonline . As part of your application you should include a research proposal outlining your proposed topic of study. Guidance on writing a research proposal is also available .

You can expect to be interviewed following your application to discuss your topic of research and to demonstrate the necessary level of commitment to your studies and training.

It is advisable that you contact us before submitting your application. This will ensure we can identify appropriate supervisors, and where necessary work with you to refine your proposal. If you would like to do this you should contact [email protected] .

If you're an international student, find out more about applying for this course at our international student web pages

Suggested Application Timings

In order to allow sufficient time for consideration of your application by an academic, for potential offer conditions to be met and travel / relocation, we recommend that applications are made before the dates outlined below. Please note that applications can still be submitted outside of the suggested dates below but there is the potential that your application/potential offer may need to be moved to the next appropriate intake window.

October Enrolment

UK Applicants – 15th August

EU/International applicants – 15th July

January Enrolment

UK applicants – 15th November

EU/International applicants – 15th October

April Enrolment

UK applicants – 15th February

EU/International applicants – 15th January

July Enrolment

UK applicants – 15th May

EU/International applicants – 15th April

EU students - visa and immigration information is available and will be regularly updated on our information for EU students page.

PhD Programme Specification

This Programme Specification refers to the current academic year and provides indicative content for information. The University will seek to deliver each course in accordance with the descriptions set out in the relevant course web pages at the time of application. However, there may be situations in which it is desirable or necessary for the University to make changes in course provision , either before or after enrolment.

Programme Summary

This PhD in Mental Health at Swansea will enable you to undertake a substantial project led by your own interests. It is a highly respected qualification which can present a career in academia or a wider scope for employment in fields such as education, government or the private sector. A thesis of 100,000 words will be submitted for assessment demonstrating original research with a substantive contribution to the subject area. The PhD is examined following an oral examination of the thesis (a viva voce examination or viva voce). You will acquire research skills for high-level work and skills and training programmes are available on campus for further support. There will be an opportunity to deliver presentations to research students and staff at departmental seminars and conferences. There may also be opportunities to develop your teaching skills through undergraduate tutorials, demonstrations and seminars.

Programme Aims

This PhD programme will provide doctoral researchers with:

- The opportunity to conduct high quality postgraduate research in a world leading research environment.

- Key skills needed to undertake advanced academic and non-academic research including qualitative and quantitative data analysis.

- Advanced critical thinking, intellectual curiosity and independent judgement.

Programme Structure

The programme comprises three key elements:

- Entry and confirmation of candidature

- Main body of research

- Thesis and viva voce

The programme comprises of the undertaking of an original research project of 3 years duration full time (6 years duration part time). Doctoral researchers may pursue the programme either full time or part time by pursuing research at the University at an external place of employment or with/at a University approved partner.

Doctoral researchers for the PhD in Mental Health are examined in two parts.

The first part is a thesis which is an original body of work representing the methods and results of the research project. The maximum word limit is 100,000 for the main text. The word limit does not include appendices (if any), essential footnotes, introductory parts and statements or the bibliography and index.

The second part is an oral examination (viva voce).

Doctoral Researcher Supervision and Support

Doctoral researchers will be supervised by a supervisory team. Where appropriate, staff from Colleges/Schools other than the ‘home’ College/School (other Colleges/Schools) within the University will contribute to cognate research areas. There may also be supervisors from an industrial partner.

The Primary/First Supervisor will normally be the main contact throughout the doctoral research journey and will have overall responsibility for academic supervision. The academic input of the Secondary Supervisor will vary from case to case. The principal role of the Secondary Supervisor is often as a first port of call if the Primary/First Supervisor becomes unavailable. The supervisory team may also include a supervisor from industry or a specific area of professional practice to support the research. External supervisors may also be drawn from other Universities.

The primary supervisor will provide pastoral support. If necessary the primary supervisor will refer the doctoral researcher to other sources of support (e.g. Wellbeing, Disability, Money Advice, IT, Library, Students’ Union, Academic Services, Student Support Services, Careers Centre).

Programme Learning Outcomes

Upon successful completion of this programme, doctoral researchers should be able to:

Knowledge & Understanding

- Demonstrate the systematic acquisition and understanding of a substantial body of knowledge which is at the forefront of research through the development of a written thesis.

- Create, interpret, analyse and develop new knowledge through original research or other advanced scholarship.

- Disseminate new knowledge gained through original research or other advanced scholarship via high quality peer reviewed publications within the discipline.

- Apply research skills and subject theory to the practice of research.

- Apply process and standards of a range of the methodologies through which research is conducted and knowledge acquired and revised.

Attitudes and values

- Conceptualise, design and implement a project aimed at the generation of new knowledge or applications within Mental Health.

- Make informed judgements on complex issues in the field of Mental Health, often in the absence of complete data and defend those judgements to an appropriate audience.

- Apply sound ethical principles to research, with due regard for the integrity of persons and in accordance with professional codes of conduct.

- Demonstrate self-awareness of individual and cultural diversity, and the reciprocal impact in social interaction between self and others when conducting research involving people.

Research Skills

- Respond appropriately to unforeseen problems in project design by making suitable amendments.

- Communicate complex research findings clearly, effectively and in an engaging manner to both specialist (including the academic community), and non-specialist audiences using a variety of appropriate media and events, including conference presentations, seminars and workshops.

- Correctly select, interpret and apply relevant techniques for research and advanced academic enquiry.

- Develop the networks and foundations for on-going research and development within the discipline.

- Implement advanced research skills to a substantial degree of independence.

- Locate information and apply it to research practice.

Skills and Competencies

- Display the qualities and transferable skills necessary for employment, including the exercise of personal responsibility and largely autonomous initiative in complex and unpredictable situations, in professional or equivalent environments.

Progression Monitoring

Progress will be monitored in accordance with Swansea University regulations. During the course of the programme, the Doctoral researcher is expected to meet regularly with their supervisors, and at most meetings it is likely that the doctoral researcher’s progress will be monitored in an informal manner in addition to attendance checks. Details of the meetings should ideally be recorded on the on-line system. A minimum of four formal supervision meetings is required each year, two of which will be reported to the Postgraduate Progression and Awards Board. During these supervisory meetings the doctoral researcher’s progress is discussed and formally recorded on the on-line system.

Learning Development

The University offers training and development for Doctoral Researchers and supervisors ( https://www.swansea.ac.uk/research/undertake-research-with-us/postgraduate-research/training-and-skills-development-programme/ ).

Swansea University’s Postgraduate Research Training Framework is structured into sections, to enable doctoral researchers to navigate and determine appropriate courses aligned to both their interest and their candidature stage.

There is a training framework including for example areas of Managing Information and Data, Presentation and Public Engagement, Leadership and working with others, Safety Integrity and Ethics, Impact and Commercialisation and Teaching and Demonstrating. There is also range of support in areas such as training needs, literature searching, conducting research, writing up research, teaching, applying for grants and awards, communicating research and future careers.

A range of research seminars and skills development sessions are provided within the School of Health and Social Care and across the University. These are scheduled to keep the doctoral researcher in touch with a broader range of material than their own research topic, to stimulate ideas in discussion with others, and to give them opportunities to such as defending their own thesis orally, and to identify potential criticisms. Additionally, the School of Health and Social Care is developing a research culture that aligns with the University vision and will link with key initiatives delivered under the auspices of the University’s Academies, for example embedding the HEA fellowship for postgraduate research students.

Research Environment

Swansea University’s research environment combines innovation and excellent facilities to provide a home for multidisciplinary research to flourish. Our research environment encompasses all aspects of the research lifecycle, with internal grants and support for external funding and enabling impact/effect that research has beyond academia.

Swansea University is very proud of our reputation for excellent research, and for the calibre, dedication, professionalism, collaboration and engagement of our research community. We understand that integrity must be an essential characteristic of all aspects of research, and that as a University entrusted with undertaking research we must clearly and consistently demonstrate that the confidence placed in our research community is rightly deserved. The University therefore ensures that everyone engaged in research is trained to the very highest standards of research integrity and conducts themselves and their research in a way that respects the dignity, rights, and welfare of participants, and minimises risks to participants, researchers, third parties, and the University itself.

In the School of Health and Social Care we are strongly focused on the translation of our research into real-life benefits for users, carers and professionals across the range of health and social care services. In doing so our staffs has long established links with a range of international networks and similar university departments in Europe and around the world, and are committed to building productive relationships with front-line policymakers and practitioners. Some senior researchers have also been embedded within the NHS to ensure healthcare and service provision is developed and informed by high quality robust research.

Alongside this we play an integral role in the Welsh Government’s research infrastructure, through the Centre for Ageing & Dementia Research, Wales School for Social Care Research and the Welsh Health Economic Support Service, increasing the volume of research taking place within Wales. While some of our PhD programmes form part of the ESRC Doctoral Training Centre for Wales, a pan-Wales collaboration to train top-level social scientists. Our funding also comes from a wide range of prestigious funders such as the Research Councils, European research programmes, Government, Ministry of Defence, professional bodies, private sector and charitable organisations, with the school securing £7.37m of funding across the last three years.

Supporting our staff and students in their research is a range of facilities including our Health and Wellbeing Academy, which provides healthcare services to the local community, a range of clinical and audiology suites and state-of-the-art research facilities. These include a high density EEG suite, a fully-fitted sleep laboratory, a social observation suite, eye-tracking, psychophysiological, tDCS and conditioning labs, a lifespan lab and baby room, and over 20 all-purpose research rooms.

Career Opportunities

Having a PhD demonstrates that graduates can work effectively in a team, formulate, explore and communicate complex ideas and manage advanced tasks. Jobs in academia (eg postdoctoral research, lecturing), education, government, management, the public or private sector are possible. Examples include administrators, counsellors, marketing specialists, and researchers.

The Postgraduate Research Office Skills Development Team offer support and a training framework for example in creating a researcher profile based upon publications and setting up your own business. The Swansea Employability Academy assists students in future career opportunities, improving CVs, job applications and interview skills.

MPhil Programme Specification

Programme Summary

This MPhil in Mental Health at Swansea will enable you to undertake a substantial project led by your own interests. It is a highly respected qualification which can present a career in academia or a wider scope for employment in fields such as education, government or the private sector. A thesis of 60,000 words will be submitted for assessment demonstrating original research with a substantive contribution to the subject area. The Masters is examined following an oral examination of the thesis (a viva voce examination or viva). You will acquire research skills for high-level work and skills and training programmes are available on campus for further support. There will be an opportunity to deliver presentations to research students and staff at departmental seminars and conferences.

This Masters programme will provide students with:

- Thesis and viva voce examination

The programme comprises of the undertaking of an original research project of 2 years duration full time (4 years duration part time). Students may pursue the programme either full time or part time by pursuing research at the University at an external place of employment or with/at a University approved partner.

Students for the Masters in Mental Health are examined in two parts.

The first part is a thesis which is an original body of work representing the methods and results of the research project. The maximum word limit is 60,000 for the main text. The word limit does not include appendices (if any), essential footnotes, introductory parts and statements or the bibliography and index.

The second part is an oral examination ( viva voce ).

Supervision and Support

Students will be supervised by a supervisory team. Where appropriate, staff from Colleges/Schools other than the ‘home’ College/School (other Colleges/Schools) within the University will contribute to cognate research areas. There may also be supervisors from an industrial partner.

The Primary/First Supervisor will normally be the main contact throughout the student journey and will have overall responsibility for academic supervision. The academic input of the Secondary Supervisor will vary from case to case. The principal role of the Secondary Supervisor is often as a first port of call if the Primary/First Supervisor becomes unavailable. The supervisory team may also include a supervisor from industry or a specific area of professional practice to support the research. External supervisors may also be drawn from other Universities.

The primary supervisor will provide pastoral support. If necessary the primary supervisor will refer the student to other sources of support (e.g. Wellbeing, Disability, Money Advice, IT, Library, Students’ Union, Academic Services, Student Support Services, Careers Centre).

Upon successful completion of this programme, doctoral researchers should be able to:

- Demonstrate the systematic acquisition and understanding of a substantial body of knowledge through the development of a written thesis.

- Create, interpret, analyse and develop new knowledge through original research or other advanced scholarship.

- Apply process and standards of a range of the methodologies through which research is conducted and knowledge acquired and revised.

- Make informed judgements on complex issues in the field of Mental Health often in the absence of complete data and defend those judgements to an appropriate audience.

- Communicate complex research findings clearly, effectively and in an engaging manner to both specialist (including the academic community), and non-specialist audiences using a variety of appropriate media.

- Correctly select, interpret and apply relevant techniques for research and academic enquiry.

- Develop the foundations for on-going research and development within the discipline.

- Implement independent research skills.

- Display the qualities and transferable skills necessary for employment, including the exercise of personal responsibility and initiative in complex situations.

Progress will be monitored in accordance with Swansea University regulations. During the course of the programme, the student is expected to meet regularly with their supervisors, and at most meetings it is likely that the student’s progress will be monitored in an informal manner in addition to attendance checks. Details of the meetings should ideally be recorded on the on-line system. A minimum of four formal supervision meetings is required each year, two of which will be reported to the Postgraduate Progression and Awards Board. During these supervisory meetings the student’s progress is discussed and formally recorded on the on-line system.

Swansea University’s Postgraduate Research Training Framework is structured into sections, to enable students to navigate and determine appropriate courses aligned to both their interest and their candidature stage.

A range of research seminars and skills development sessions are provided within the School of Health and Social Care and across the University. These are scheduled to keep the student in touch with a broader range of material than their own research topic, to stimulate ideas in discussion with others, and to give them opportunities to such as defending their own thesis orally, and to identify potential criticisms. Additionally, the School of Health and Social Care is developing a research culture that will align with the University vision and will link with key initiatives delivered under the auspices of the University’s Academies, for example embedding the HEA fellowship for postgraduate research students

Research Environment

Swansea University’s Research Environment combines innovation and excellent facilities to provide a home for multidisciplinary research to flourish. Our research environment encompasses all aspects of the research lifecycle, with internal grants and support for external funding and enabling impact/effect that research has beyond academia.

Swansea University is very proud of our reputation for excellent research, and for the calibre, dedication, professionalism, collaboration and engagement of our research community. We understand that integrity must be an essential characteristic of all aspects of research, and that as a University entrusted with undertaking research we must clearly and consistently demonstrate that the confidence placed in our research community is rightly deserved. The University therefore ensures that everyone engaged in research is trained to the very highest standards of research integrity and conducts themselves and their research in a way that respects the dignity, rights, and welfare of participants, and minimises risks to participants, researchers, third parties, and the University itself.

College of Human and Health Sciences

In the School of Health and Social Care we are strongly focused on the translation of our research into real-life benefits for users, carers and professionals across the range of health and social care services. In doing so our staff have long established links with a range of international networks and similar university departments in Europe and around the world, and are committed to building productive relationships with front-line policymakers and practitioners. Some senior researchers have also been embedded within the NHS to ensure healthcare and service provision is developed and informed by high quality robust research.

Having a Master of Philosophy degree shows that you can communicate your ideas and manage tasks. Jobs in academia, education, government, management, the public or private sector are possible.

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C13'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 1

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C14'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 2

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C15'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 3

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C16'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 4

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C17'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - final

1" v-html="item['0C7']">

Supervisor(s):

1">Read 's thesis online at

')" v-html="p">

Project abstract

Project aims, progress report - year 1, progress report - year 2, progress report - year 3, progress report - year 4, progress report - final year, mental health research uk, the first uk charity dedicated to raising funds for research into mental illnesses, their causes and cures., since 2008, we have ....

in scholarships

research students

research publications

Mental Health Research UK aims to make a significant improvement to the lives of people with mental illness, by funding research into causes and cures. We know it is often challenging to find resources to support PhD studentships and that is why we focus our funding on these awards, supporting mental health researchers of the future.

Although only registered with the Charity Commission in 2008, Mental Health Research UK has already made research awards; the first being funded jointly with the University of Nottingham.

Select the sub-headings below to learn more ...

What we fund

We fund research into:

- The underlying causes of mental ill health

- Treatments for mental health problems

We do not fund research into autism or dementia. Nor do we fund research that involves laboratory animals.

Mental Health Research UK has one competitive round of PhD Scholarship awards per year, launched in the spring, for submission in May, with decisions made in the autumn to start the following year. The annual timeline is as follows:

- March: Scholarships are advertised via our mailing list and listed on our website.

- Mid-May: Closing date for applications.

- July: The panel meets and shortlists applications. Those not shortlisted are informed at once. References and service user reports are organized.

- September: Deadline for the receipt of references and service user reports.

- Late September: The panel meets and selects applicants to be offered a scholarship.

- October: All applicants are notified of the outcome of their application by the end of the month.

Research topics

Mental Health Research UK makes research awards focusing on research into the causes of, or cures for, mental illnesses.

The specific research topics of interest are selected year-on-year by the Trustees. However, the Schizophrenia Research Fund John Grace QC PhD Scholarship award always focuses on Schizophrenia.

Our awards cover fees and stipend only and are based on the Medical Research Council’s minimum stipend and fees for UK students, currently as follows:

2023/24 stipend: Outside London: £18,662; Inside London: £20,622

2023/24 fees: £4,712

Funding will cease at 4 years or on submission of the PhD thesis, whichever is earlier.

The fourth year is regarded as a ‘writing up’ year and the grant will be the stipend and thesis fee only.

In the event of early submission, a brief application to retain the student for the remainder of the period within the total cost envelope will be considered. College fees will be considered, where advertised by the university as being in addition to the tuition fee.

Mental Health Research UK will consider a small grant towards travel and conference allowances, where the student is presenting, subject to prior approval. No contribution will be made towards Research Training and Support grants.

If your university fees or stipend are different from the above, we will consider these provided you advise us with your application.

MD(Res) awards

Please note that applications are not currently being considered.

The Trustees of Mental Health Research UK have, since 2018, supported the MD(Res) degree at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IOPPN) at King's College, London.

Mental Health Research UK wishes to support young psychiatrists with an interest in mental health research by offering scholarships for this programme because we need to encourage more people to develop careers within academic psychiatry. We are keen to provide a supportive community within Mental Health Research UK for all our scholars, which the MD(Res) award holders will join. This will help doctors thrive in their studies and ensure progress is made towards improving the lives of people with mental health problems, through scientific advances.

Dr Gareth Owen, Chair of the MD(Res) committee, IOPPN said:

"Doctors working in mental health sometimes come to research questions later in their careers with the benefit of clinical experience and training. It is hugely important that their experience and research energy is tapped and academic awards make a real difference to enabling such innovation. These awards from MHRUK are an excellent way to bring clinical experience and high quality research supervision together to foster an exciting new cohort of clinical academics in mental health."

Eligibility

Applications for our awards need to come from UK universities. Research supervisors must be based at UK universities.

We accept one application per scholarship award from any one university. A university may apply for more than one scholarship if they wish.

Please note that we do not accept any requests for funding from individuals, including current PhD students.

User and carer involvement

Best practice will be followed to ensure that service users and carers are involved at all stages with the prioritization of research topics and the commissioning of research.

All research project applications will be peer-reviewed by service user reviewers as well as academic reviewers.

NIHR and NHS information

Mental Health Research UK is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) non-commercial Partner . This means the studies that we fund may be eligible to access the NIHR Study Support Service which is provided by the NIHR Clinical Research Network. The NIHR Clinical Research Network can now support health and social care research taking place in non-NHS settings, such as studies running in care homes or hospices, or public health research taking place in schools and other community settings. Read the full policy: Eligibility Criteria for NIHR Clinical Research Network Support . In partnership with your local R&D office, we encourage MHRUK award holders to involve your local NIHR Clinical Research Network team in discussions as early as possible when planning your study. This will enable you to fully benefit from the support available through the NIHR Study Support Service.

If your study involves NHS sites in England or Wales you will need to apply for Health Research Authority (HRA) and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) Approval .

Open Access publication of research results

Students can download our application form for open access publication of research results here .

PhD Competition 2025

Mental Health Research UK (incorporating the Schizophrenia Research Fund) is pleased to announce a competition for 2 PhD Scholarships beginning September 2025.

We are inviting applications for PhD scholarships under the theme of maternal mental health . We view this topic in its broadest sense inviting proposals that cover all aspects of mental health during pregnancy and in the first year afterwards. We are interested in proposals that aim to understand causes, risk factors, mechanisms, or treatments. MHRUK does not fund health services research.

John Grace QC scholarship 2025: Maternal mental health

The John Grace QC scholarship should focus on psychotic disorders, including puerperal psychosis.

MHRUK scholarship 2025: Maternal mental health

The second scholarship is open, and we invite applications on topics such as post-natal depression, developing post-natal family mental health interventions, factors influencing maternal mental health.

We invite applications from UK Universities for these scholarships. The deadline for applications is midnight on 27th May 2024.

The full terms and conditions can be found here .

If you have any queries regarding the application process, please read the guidance above and check our FAQs document . If this does not provide the information that you need, please contact [email protected] .

Please note that for each individual scholarship we can accept only one application per university. A university may apply for more than one scholarship if they wish.

Scholarships Awarded

Find out more about the scholarships that we have awarded..

Use the buttons below to filter the list.

1" span v-html="item['0C7']">

Select from the tags below to filter by topic:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 December 2021

Nationwide assessment of the mental health of UK Doctoral Researchers

- Cassie M. Hazell 1 ,

- Jeremy E. Niven 2 ,

- Laura Chapman 3 ,

- Paul E. Roberts 4 ,

- Sam Cartwright-Hatton 3 ,

- Sophie Valeix 2 &

- Clio Berry 5

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 305 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

8631 Accesses

15 Citations

106 Altmetric

Metrics details

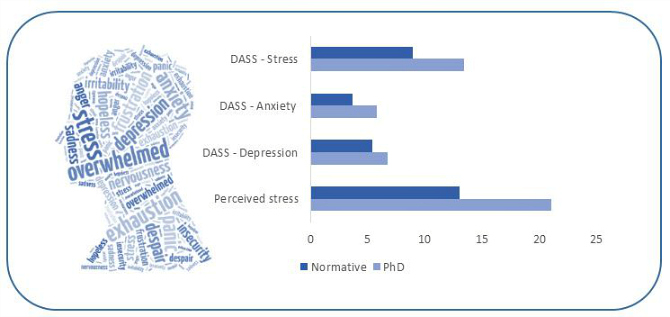

Doctoral Researchers (DRs) are an important part of the academic community and, after graduating, make substantial social and economic contributions. Despite this importance, DR wellbeing has long been of concern. Recent studies have concluded that DRs may be particularly vulnerable to mental health problems, yet direct comparisons of the prevalence of mental health problems between this population and control groups are lacking. Here, by comparing DRs with educated working controls, we show that DRs report significantly greater anxiety and depression, and that this difference is not explained by a higher rate of pre-existing mental health problems. Moreover, most DRs perceive poor mental health as a ‘normal’ part of the PhD process. Thus, our findings suggest a hazardous impact of PhD study on mental health, with DRs being particularly at risk of developing common mental health problems. This provides an evidence-based mandate for universities and funders to reflect upon practices related to DR training and mental health. Our attention should now be directed towards understanding what factors may explain heightened anxiety and depression among DRs so as to inform preventative measures and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Doctoral researchers’ mental health and PhD training satisfaction during the German COVID-19 lockdown: results from an international research sample

Prevalence of mental health symptoms and potential risk factors among Austrian psychotherapists

A cross-sectional study of the health status of Swiss primary care physicians

Introduction.

University research makes a substantial contribution to the economy (University Alliance, 2014 ). A significant part of that contribution is driven by Doctoral Researchers (DRs), also known as PhD students, who consistently produce a reliable financial return on any investment in their studies, both to their institution and to industry more widely (Casey, 2009 ; EPSRC, 2010 ; Zolas et al., 2015 ). When asked during their PhD studies, the majority of DRs want to pursue a career in research post-PhD (Cornell, 2020 ). However, in reality, subsequent to receiving their PhD, more than 70% leave academia completely (Hancock, 2020 ); instead pursuing careers in industry, government or non-profit organisations (Cornell, 2020 ). A key motivator for DRs leaving academia is to protect their mental health (Metcalfe et al., 2018 ). Therefore, the poor mental health of DRs and their subsequent exodus from academia will have implications for the volume and quality of academic research, as well as having broader social and economic impacts.

The issue of DR mental health was well evidenced in a recent international survey by Nature (Woolston, 2019 ). The survey found that 36% of current DRs reported seeking help for anxiety and/or depression (Woolston, 2019 ), with further editorials acknowledging the poor mental health of PhD students (Nature, 2019b , 2019a ; Woolston, 2020 ). A recent meta-analysis found that DRs are moderately more stressed when compared to whole population normative data (Hazell et al., 2020 ). The available research all points in the same direction: DRs are stressed and experiencing poor mental health, and may be leaving the profession as a result of this (Hazell et al., 2020 ). However, there are significant limitations and gaps in the understanding of DR mental health (Hazell et al., 2020 ). In particular, we do not know whether DRs are at a higher risk of poor mental health than individuals who chose other career pathways because studies largely did not include comparison groups.

One recent study did attempt to address this gap in the field (Levecque et al., 2017 ); employing an online survey, this study revealed that DRs reported greater psychological distress than both undergraduate students and educated employees. However, this study, along with all others in the field (Hazell et al., 2020 ), did not assess symptoms indicative of Serious Mental Illness (SMI) diagnoses. Instead, this study (Levecque et al., 2017 ) used the General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ12) (Goldberg et al., 1997 ), which has been widely criticised for encouraging response biases, lack of reliability, and limited clinical validity (Hankins, 2008a , 2008b ; Ye, 2009 ). Finally, to our knowledge, no studies have addressed the issue of causality. That is, whether those with existing poor mental health might be more attracted to pursuing PhD studies or whether studying for the PhD itself is the cause of mental health difficulties.

To address these limitations, we conducted a UK-based mixed-methods online survey with DRs, and a control group comprised of similarly aged, educated working professionals (WP). The central aim of our study was to determine how the prevalence of mental health problems differs between DRs and WPs. Secondary to this, we aimed to assess DRs’ perceptions of the commonality of mental health problems. Our survey employed outcomes measures with well-established clinical cut-offs and included measures that capture SMI symptoms i.e. mania and suicidality. We also controlled for pre-existing mental health problems, which allowed us to test whether our data support PhD study as causative of mental health problems.

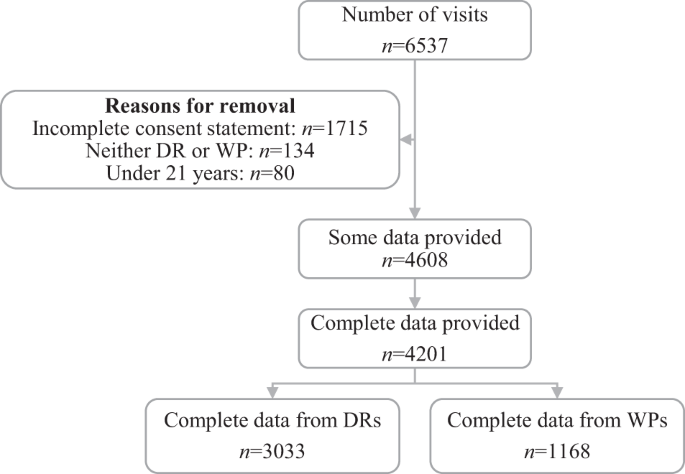

Participants

We recruited DRs and a matched group of educated WPs. To be eligible for inclusion in the DR group, participants had to be currently studying for their PhD at a UK University. The eligibility criteria for the WP group were developed to ensure similarity between the two groups, other than PhD status. Eligibility criteria, therefore, reflected the minimum entry requirements for PhD programmes in the UK. WPs had to be aged 21 years or over and possess a university undergraduate degree of 2.1 or above. Moreover, WPs had to be working in the UK at least 3 days a week (0.6 full time equivalent (FTE)) as this matched the minimum FTE for a part-time PhD.

Recruitment

To recruit DRs, we emailed every Doctoral School in the UK ( N = 162) asking them to share details of the study with their students. To recruit WPs, we emailed the public relations departments of the top 100 graduate employers and the top 500 UK businesses. None of the graduate employers confirmed that they had disseminated the survey details. Additionally, we promoted the study via the project social media outlets, Prolific Academic and paid advertisements on Facebook. As part of the debrief information, we asked participants to share details of the survey with their personal and professional networks.

The study is an online, cross-sectional survey. We used a between-group design, comparing responses from DRs to WPs. The survey was administered using Qualtrics survey software.

We collected data using a battery of measures of mental health problems and psychological and social functioning. In the present paper, we report comparative data on prevalence and symptomatology for DRs and WPs.

Demographics

Participants were asked to self-identify as either a DR or a WP and then complete basic demographic questionnaires. DRs were asked for information about their PhD, including funding status and whether they were engaging in fieldwork. WPs were asked to classify the type of job they have and how likely they were to complete a PhD in the future.

As part of the demographic questionnaire, we asked participants about their mental health, including whether they have a mental health diagnosis, and whether they have experienced a mental health crisis. With the aim of assessing premorbid mental health, we adapted interview questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler and Üstün, 2004 ), in which lifetime prevalence participants are asked to reflect on key milestones across the lifespan and whether they were experiencing mental health problems at that time. Using milestones to determine the onset of mental health problems is associated with increased accuracy of retrospective data (Kessler et al., 2005 ). We provided participants with a series of milestones related to their studies and work history and asked them to indicate whether they were experiencing mental health problems at that time or not, for example while at secondary school, before they started an undergraduate degree, while completing an undergraduate degree and so on.