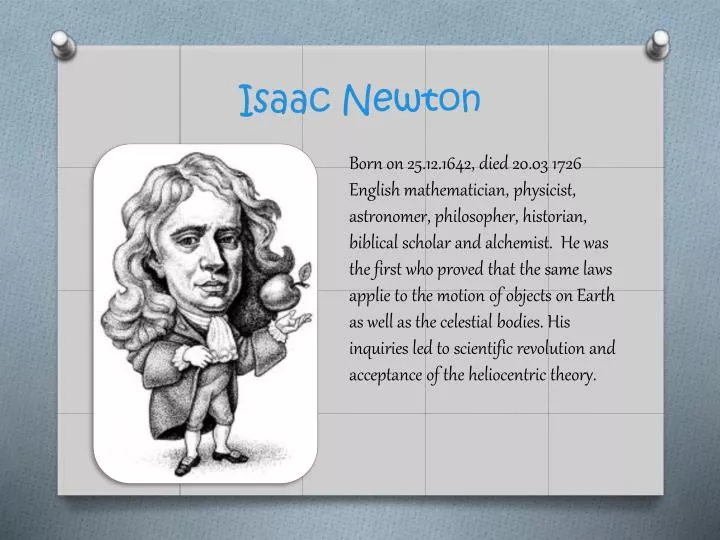

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton was an English physicist and mathematician famous for his laws of physics. He was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century.

(1643-1727)

Who Was Isaac Newton?

In 1687, he published his most acclaimed work, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) , which has been called the single most influential book on physics. In 1705, he was knighted by Queen Anne of England, making him Sir Isaac Newton.

Early Life and Family

Newton was born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England. Using the "old" Julian calendar, Newton's birth date is sometimes displayed as December 25, 1642.

Newton was the only son of a prosperous local farmer, also named Isaac, who died three months before he was born. A premature baby born tiny and weak, Newton was not expected to survive.

When he was 3 years old, his mother, Hannah Ayscough Newton, remarried a well-to-do minister, Barnabas Smith, and went to live with him, leaving young Newton with his maternal grandmother.

The experience left an indelible imprint on Newton, later manifesting itself as an acute sense of insecurity. He anxiously obsessed over his published work, defending its merits with irrational behavior.

At age 12, Newton was reunited with his mother after her second husband died. She brought along her three small children from her second marriage.

Isaac Newton's Education

Newton was enrolled at the King's School in Grantham, a town in Lincolnshire, where he lodged with a local apothecary and was introduced to the fascinating world of chemistry.

His mother pulled him out of school at age 12. Her plan was to make him a farmer and have him tend the farm. Newton failed miserably, as he found farming monotonous. Newton was soon sent back to King's School to finish his basic education.

Perhaps sensing the young man's innate intellectual abilities, his uncle, a graduate of the University of Cambridge's Trinity College , persuaded Newton's mother to have him enter the university. Newton enrolled in a program similar to a work-study in 1661, and subsequently waited on tables and took care of wealthier students' rooms.

Scientific Revolution

When Newton arrived at Cambridge, the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century was already in full force. The heliocentric view of the universe—theorized by astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, and later refined by Galileo —was well known in most European academic circles.

Philosopher René Descartes had begun to formulate a new concept of nature as an intricate, impersonal and inert machine. Yet, like most universities in Europe, Cambridge was steeped in Aristotelian philosophy and a view of nature resting on a geocentric view of the universe, dealing with nature in qualitative rather than quantitative terms.

During his first three years at Cambridge, Newton was taught the standard curriculum but was fascinated with the more advanced science. All his spare time was spent reading from the modern philosophers. The result was a less-than-stellar performance, but one that is understandable, given his dual course of study.

It was during this time that Newton kept a second set of notes, entitled "Quaestiones Quaedam Philosophicae" ("Certain Philosophical Questions"). The "Quaestiones" reveal that Newton had discovered the new concept of nature that provided the framework for the Scientific Revolution. Though Newton graduated without honors or distinctions, his efforts won him the title of scholar and four years of financial support for future education.

In 1665, the bubonic plague that was ravaging Europe had come to Cambridge, forcing the university to close. After a two-year hiatus, Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667 and was elected a minor fellow at Trinity College, as he was still not considered a standout scholar.

In the ensuing years, his fortune improved. Newton received his Master of Arts degree in 1669, before he was 27. During this time, he came across Nicholas Mercator's published book on methods for dealing with infinite series.

Newton quickly wrote a treatise, De Analysi , expounding his own wider-ranging results. He shared this with friend and mentor Isaac Barrow, but didn't include his name as author.

In June 1669, Barrow shared the unaccredited manuscript with British mathematician John Collins. In August 1669, Barrow identified its author to Collins as "Mr. Newton ... very young ... but of an extraordinary genius and proficiency in these things."

Newton's work was brought to the attention of the mathematics community for the first time. Shortly afterward, Barrow resigned his Lucasian professorship at Cambridge, and Newton assumed the chair.

Isaac Newton’s Discoveries

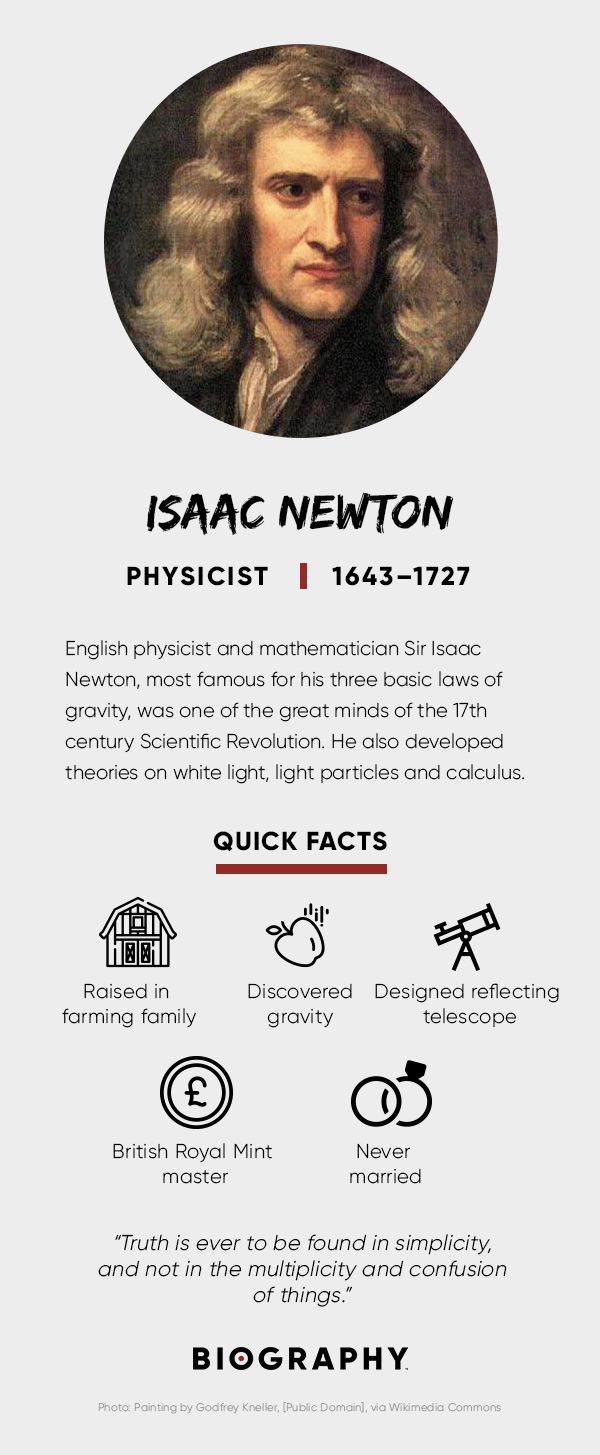

Newton made discoveries in optics, motion and mathematics. Newton theorized that white light was a composite of all colors of the spectrum, and that light was composed of particles.

His momentous book on physics, Principia , contains information on nearly all of the essential concepts of physics except energy, ultimately helping him to explain the laws of motion and the theory of gravity. Along with mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, Newton is credited for developing essential theories of calculus.

Isaac Newton Inventions

Newton's first major public scientific achievement was designing and constructing a reflecting telescope in 1668. As a professor at Cambridge, Newton was required to deliver an annual course of lectures and chose optics as his initial topic. He used his telescope to study optics and help prove his theory of light and color.

The Royal Society asked for a demonstration of his reflecting telescope in 1671, and the organization's interest encouraged Newton to publish his notes on light, optics and color in 1672. These notes were later published as part of Newton's Opticks: Or, A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light .

The Apple Myth

Between 1665 and 1667, Newton returned home from Trinity College to pursue his private study, as school was closed due to the Great Plague. Legend has it that, at this time, Newton experienced his famous inspiration of gravity with the falling apple. According to this common myth, Newton was sitting under an apple tree when a fruit fell and hit him on the head, inspiring him to suddenly come up with the theory of gravity.

While there is no evidence that the apple actually hit Newton on the head, he did see an apple fall from a tree, leading him to wonder why it fell straight down and not at an angle. Consequently, he began exploring the theories of motion and gravity.

It was during this 18-month hiatus as a student that Newton conceived many of his most important insights—including the method of infinitesimal calculus, the foundations for his theory of light and color, and the laws of planetary motion—that eventually led to the publication of his physics book Principia and his theory of gravity.

Isaac Newton’s Laws of Motion

In 1687, following 18 months of intense and effectively nonstop work, Newton published Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) , most often known as Principia .

Principia is said to be the single most influential book on physics and possibly all of science. Its publication immediately raised Newton to international prominence.

Principia offers an exact quantitative description of bodies in motion, with three basic but important laws of motion:

A stationary body will stay stationary unless an external force is applied to it.

Force is equal to mass times acceleration, and a change in motion (i.e., change in speed) is proportional to the force applied.

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Newton and the Theory of Gravity

Newton’s three basic laws of motion outlined in Principia helped him arrive at his theory of gravity. Newton’s law of universal gravitation states that two objects attract each other with a force of gravitational attraction that’s proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

These laws helped explain not only elliptical planetary orbits but nearly every other motion in the universe: how the planets are kept in orbit by the pull of the sun’s gravity; how the moon revolves around Earth and the moons of Jupiter revolve around it; and how comets revolve in elliptical orbits around the sun.

They also allowed him to calculate the mass of each planet, calculate the flattening of the Earth at the poles and the bulge at the equator, and how the gravitational pull of the sun and moon create the Earth’s tides. In Newton's account, gravity kept the universe balanced, made it work, and brought heaven and Earth together in one great equation.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S ISAAC NEWTON FACT CARD

Isaac Newton & Robert Hooke

Not everyone at the Royal Academy was enthusiastic about Newton’s discoveries in optics and 1672 publication of Opticks: Or, A treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light . Among the dissenters was Robert Hooke , one of the original members of the Royal Academy and a scientist who was accomplished in a number of areas, including mechanics and optics.

While Newton theorized that light was composed of particles, Hooke believed it was composed of waves. Hooke quickly condemned Newton's paper in condescending terms, and attacked Newton's methodology and conclusions.

Hooke was not the only one to question Newton's work in optics. Renowned Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens and a number of French Jesuits also raised objections. But because of Hooke's association with the Royal Society and his own work in optics, his criticism stung Newton the worst.

Unable to handle the critique, he went into a rage—a reaction to criticism that was to continue throughout his life. Newton denied Hooke's charge that his theories had any shortcomings and argued the importance of his discoveries to all of science.

In the ensuing months, the exchange between the two men grew more acrimonious, and soon Newton threatened to quit the Royal Society altogether. He remained only when several other members assured him that the Fellows held him in high esteem.

The rivalry between Newton and Hooke would continue for several years thereafter. Then, in 1678, Newton suffered a complete nervous breakdown and the correspondence abruptly ended. The death of his mother the following year caused him to become even more isolated, and for six years he withdrew from intellectual exchange except when others initiated correspondence, which he always kept short.

During his hiatus from public life, Newton returned to his study of gravitation and its effects on the orbits of planets. Ironically, the impetus that put Newton on the right direction in this study came from Robert Hooke.

In a 1679 letter of general correspondence to Royal Society members for contributions, Hooke wrote to Newton and brought up the question of planetary motion, suggesting that a formula involving the inverse squares might explain the attraction between planets and the shape of their orbits.

Subsequent exchanges transpired before Newton quickly broke off the correspondence once again. But Hooke's idea was soon incorporated into Newton's work on planetary motion, and from his notes it appears he had quickly drawn his own conclusions by 1680, though he kept his discoveries to himself.

In early 1684, in a conversation with fellow Royal Society members Christopher Wren and Edmond Halley, Hooke made his case on the proof for planetary motion. Both Wren and Halley thought he was on to something, but pointed out that a mathematical demonstration was needed.

In August 1684, Halley traveled to Cambridge to visit with Newton, who was coming out of his seclusion. Halley idly asked him what shape the orbit of a planet would take if its attraction to the sun followed the inverse square of the distance between them (Hooke's theory).

Newton knew the answer, due to his concentrated work for the past six years, and replied, "An ellipse." Newton claimed to have solved the problem some 18 years prior, during his hiatus from Cambridge and the plague, but he was unable to find his notes. Halley persuaded him to work out the problem mathematically and offered to pay all costs so that the ideas might be published, which it was, in Newton’s Principia .

Upon the publication of the first edition of Principia in 1687, Robert Hooke immediately accused Newton of plagiarism, claiming that he had discovered the theory of inverse squares and that Newton had stolen his work. The charge was unfounded, as most scientists knew, for Hooke had only theorized on the idea and had never brought it to any level of proof.

Newton, however, was furious and strongly defended his discoveries. He withdrew all references to Hooke in his notes and threatened to withdraw from publishing the subsequent edition of Principia altogether.

Halley, who had invested much of himself in Newton's work, tried to make peace between the two men. While Newton begrudgingly agreed to insert a joint acknowledgment of Hooke's work (shared with Wren and Halley) in his discussion of the law of inverse squares, it did nothing to placate Hooke.

As the years went on, Hooke's life began to unravel. His beloved niece and companion died the same year that Principia was published, in 1687. As Newton's reputation and fame grew, Hooke's declined, causing him to become even more bitter and loathsome toward his rival.

To the very end, Hooke took every opportunity he could to offend Newton. Knowing that his rival would soon be elected president of the Royal Society, Hooke refused to retire until the year of his death, in 1703.

Newton and Alchemy

Following the publication of Principia , Newton was ready for a new direction in life. He no longer found contentment in his position at Cambridge and was becoming more involved in other issues.

He helped lead the resistance to King James II's attempts to reinstitute Catholic teaching at Cambridge, and in 1689 he was elected to represent Cambridge in Parliament.

While in London, Newton acquainted himself with a broader group of intellectuals and became acquainted with political philosopher John Locke . Though many of the scientists on the continent continued to teach the mechanical world according to Aristotle , a young generation of British scientists became captivated with Newton's new view of the physical world and recognized him as their leader.

One of these admirers was Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a Swiss mathematician whom Newton befriended while in London.

However, within a few years, Newton fell into another nervous breakdown in 1693. The cause is open to speculation: his disappointment over not being appointed to a higher position by England's new monarchs, William III and Mary II, or the subsequent loss of his friendship with Duillier; exhaustion from being overworked; or perhaps chronic mercury poisoning after decades of alchemical research.

It's difficult to know the exact cause, but evidence suggests that letters written by Newton to several of his London acquaintances and friends, including Duillier, seemed deranged and paranoiac, and accused them of betrayal and conspiracy.

Oddly enough, Newton recovered quickly, wrote letters of apology to friends, and was back to work within a few months. He emerged with all his intellectual facilities intact, but seemed to have lost interest in scientific problems and now favored pursuing prophecy and scripture and the study of alchemy.

While some might see this as work beneath the man who had revolutionized science, it might be more properly attributed to Newton responding to the issues of the time in turbulent 17th century Britain.

Many intellectuals were grappling with the meaning of many different subjects, not least of which were religion, politics and the very purpose of life. Modern science was still so new that no one knew for sure how it measured up against older philosophies.

Gold Standard

In 1696, Newton was able to attain the governmental position he had long sought: warden of the Mint; after acquiring this new title, he permanently moved to London and lived with his niece, Catherine Barton.

Barton was the mistress of Lord Halifax, a high-ranking government official who was instrumental in having Newton promoted, in 1699, to master of the Mint—a position that he would hold until his death.

Not wanting it to be considered a mere honorary position, Newton approached the job in earnest, reforming the currency and severely punishing counterfeiters. As master of the Mint, Newton moved the British currency, the pound sterling, from the silver to the gold standard.

The Royal Society

In 1703, Newton was elected president of the Royal Society upon Robert Hooke's death. However, Newton never seemed to understand the notion of science as a cooperative venture, and his ambition and fierce defense of his own discoveries continued to lead him from one conflict to another with other scientists.

By most accounts, Newton's tenure at the society was tyrannical and autocratic; he was able to control the lives and careers of younger scientists with absolute power.

In 1705, in a controversy that had been brewing for several years, German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz publicly accused Newton of plagiarizing his research, claiming he had discovered infinitesimal calculus several years before the publication of Principia .

In 1712, the Royal Society appointed a committee to investigate the matter. Of course, since Newton was president of the society, he was able to appoint the committee's members and oversee its investigation. Not surprisingly, the committee concluded Newton's priority over the discovery.

That same year, in another of Newton's more flagrant episodes of tyranny, he published without permission the notes of astronomer John Flamsteed. It seems the astronomer had collected a massive body of data from his years at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, England.

Newton had requested a large volume of Flamsteed's notes for his revisions to Principia . Annoyed when Flamsteed wouldn't provide him with more information as quickly as he wanted it, Newton used his influence as president of the Royal Society to be named the chairman of the body of "visitors" responsible for the Royal Observatory.

He then tried to force the immediate publication of Flamsteed's catalogue of the stars, as well as all of Flamsteed's notes, edited and unedited. To add insult to injury, Newton arranged for Flamsteed's mortal enemy, Edmund Halley, to prepare the notes for press.

Flamsteed was finally able to get a court order forcing Newton to cease his plans for publication and return the notes—one of the few times that Newton was bested by one of his rivals.

Final Years

Toward the end of this life, Newton lived at Cranbury Park, near Winchester, England, with his niece, Catherine (Barton) Conduitt, and her husband, John Conduitt.

By this time, Newton had become one of the most famous men in Europe. His scientific discoveries were unchallenged. He also had become wealthy, investing his sizable income wisely and bestowing sizable gifts to charity.

Despite his fame, Newton's life was far from perfect: He never married or made many friends, and in his later years, a combination of pride, insecurity and side trips on peculiar scientific inquiries led even some of his few friends to worry about his mental stability.

By the time he reached 80 years of age, Newton was experiencing digestion problems and had to drastically change his diet and mobility.

In March 1727, Newton experienced severe pain in his abdomen and blacked out, never to regain consciousness. He died the next day, on March 31, 1727, at the age of 84.

Newton's fame grew even more after his death, as many of his contemporaries proclaimed him the greatest genius who ever lived. Maybe a slight exaggeration, but his discoveries had a large impact on Western thought, leading to comparisons to the likes of Plato , Aristotle and Galileo.

Although his discoveries were among many made during the Scientific Revolution, Newton's universal principles of gravity found no parallels in science at the time.

Of course, Newton was proven wrong on some of his key assumptions. In the 20th century, Albert Einstein would overturn Newton's concept of the universe, stating that space, distance and motion were not absolute but relative and that the universe was more fantastic than Newton had ever conceived.

Newton might not have been surprised: In his later life, when asked for an assessment of his achievements, he replied, "I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me."

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Isaac Newton

- Birth Year: 1643

- Birth date: January 4, 1643

- Birth City: Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Isaac Newton was an English physicist and mathematician famous for his laws of physics. He was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century.

- Science and Medicine

- Technology and Engineering

- Education and Academia

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- University of Cambridge, Trinity College

- The King's School

- Interesting Facts

- Isaac Newton helped develop the principles of modern physics, including the laws of motion, and is credited as one of the great minds of the 17th-century Scientific Revolution.

- In 1687, Newton published his most acclaimed work, 'Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica' ('Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy'), which has been called the single most influential book on physics.

- Newton's theory of gravity states that two objects attract each other with a force of gravitational attraction that’s proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

- Death Year: 1727

- Death date: March 31, 1727

- Death City: London, England

- Death Country: United Kingdom

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Isaac Newton Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/isaac-newton

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 5, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

- Plato is my friend, Aristotle is my friend, but my greatest friend is truth.

- If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

- It is the perfection of God's works that they are all done with the greatest simplicity.

- Every body continues in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it.

- To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or, the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.

- I see I have made myself a slave to philosophy.

- The changing of bodies into light, and light into bodies, is very conformable to the course of nature, which seems delighted with transmutations.

- To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age. Tis much better to do a little with certainty and leave the rest for others that come after, then to explain all things by conjecture without making sure of any thing.

- Truth is ever to be found in simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things.

- Atheism is so senseless and odious to mankind that it never had many professors.

- Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians, the last of the Babylonians and Sumerians, the last great mind that looked out on the visible and intellectual world with the same eyes as those who began to build our intellectual inheritance rather less than 10,000 years ago.

Famous British People

Amy Winehouse

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Biographies for Kids

Isaac newton.

- Occupation: Scientist, mathematician, and astronomer

- Born: January 4, 1643 in Woolsthorpe, England

- Best known for: Defining the three laws of motion and universal gravitation

- Gravity - Newton is probably most famous for discovering gravity. Outlined in the Principia, his theory about gravity helped to explain the movements of the planets and the Sun. This theory is known today as Newton's law of universal gravitation.

- Laws of Motion - Newton's laws of motion were three fundamental laws of physics that laid the foundation for classical mechanics.

- Calculus - Newton invented a whole new type of mathematics which he called "fluxions." Today we call this math calculus and it is an important type of math used in advanced engineering and science.

- Reflecting Telescope - In 1668 Newton invented the reflecting telescope . This type of telescope uses mirrors to reflect light and form an image. Nearly all of the major telescopes used in astronomy today are reflecting telescopes.

- He studied many classic philosophers and astronomers such as Aristotle, Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Rene Descartes, and Galileo.

- Legend has it that Newton got his inspiration for gravity when he saw an apple fall from a tree on his farm.

- He wrote his thoughts down in the Principia at the urging of his friend (and famous astronomer) Edmond Halley. Halley even paid for the book's publication.

- He once said of his own work "If I have seen further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants."

- Listen to a recorded reading of this page:

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Isaac Newton.

Published by Catherine Hampton Modified over 6 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Isaac Newton."— Presentation transcript:

Lecture 4 Newton - Gravity Dennis Papadopoulos ASTR 340 Fall 2006.

More On Sir Isaac Newton Newton’s Laws of Motion.

Free Science Videos for Kids

Sir Isaac Newton Life and Accomplishments Group 4 Octavio Aguilera Juan Aldana Alex Serna.

Sir Isaac Newton His life and accomplishments By Kelsey Zolac.

Sir Isaac Newton Joni Jaeger Science, Technology and Society.

Sir Isaac Newton & The Three Laws of Motion 5 th Grade.

Astro: Chapter 3-5. The birth of modern astronomy and of modern science dates from the 144 years between Copernicus’ book (1543) and Newton’s book (1687).

TONY NGUYEN Isaac Newton. Issac Sir Isaac Newton born on 1642 became a mathematician and physicist and one of the most scientific intellects of all time.

By: Gregorio Moya and Jose Lopez

PHYSICS PROJECT Sir Isaac Newton ( ).

IsaacNewton— theGreat English Scientist IsaacNewton— theGreat English Scientist.

Newton’s Laws Inertia Force Action Reaction Isaac Newton ( ) Life & Character –Born at Woolsthorpe in Lincolnshire (England) –entered Cambridge.

Newton’s Third Law of Motion

Newton’s Laws of Motion

Newton’s Laws Henry Lobo. Issac Newton Born December 25, 1642 In Woolsthrope a city in Lincolnshire, England Educated at Trinity College Founded the laws.

Sir Isaac Newton “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Sir Isaac Newton.

Isaac Newton “One of the Greatest Scientists That Ever Lived”

Isaac Newton (: Taylor Jones 8/6 Math (:. Isaac N.

Sir Isaac Newton ( ) By: Jessica, Tony, Trish, Martin & Mirna.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Preferences

Sir Isaac Newton - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Sir Isaac Newton

Sir isaac newton life and accomplishments group 4 octavio aguilera juan aldana alex serna table of contents the beginning of his life early life reflecting telescope ... – powerpoint ppt presentation.

- Life and Accomplishments

- Octavio Aguilera

- Juan Aldana

- The Beginning of His Life

- Reflecting Telescope

- Motion and Gravity

- First Law of Motion

- Second Law of Motion

- Third Law of Motion

- Principia and Opticks

- A Great Man

- Born on January 4, 1643

- In Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England

- Where he was raised by his Grandmother

- Newton received a bachelors degree at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1665

- The next two years Newton returned home where he came up with most of his discoveries.

- He returned to Trinity College in 1667, where he became a professor of mathematics in 1669.

- In 1668 Newton made the first reflecting telescope

- Light is collected and refracted from a curved mirror

- Far superior from refracting telescopes because the image did not become blurry

- Newton invented Calculus in 1669, but didnt publish his work until 1704

- Calculus is divided into two parts Differential and Integral Calculus

- Differential Calculus Deals with the change in rate of objects

- Integral Calculus Deals with measuring quantities and dividing into smaller ones

- Newton wondered why objects fell to earth while sitting under an apple tree he saw an apple fall in front of him

- Although many believe this story is untrue

- That is when Newton came up with the three laws of motion

- A body continues in a state of rest in a straight line if it is not acted upon by forces.

- When a force acts on a body it produces an acceleration, which is proportional to the magnitude of the force

- If body A exerts a force on body B, body B always exerts an equal and opposite force on body A

- Newton believed that when an object goes around another there are two balanced forces.

- Centripetal force pulls the revolving object towards the pivoting point

- Centrifugal force pulls the object away from pivoting point

- Newton showed that comets acted upon by the same forces as the planets

- Proved when Edmund Halley predicted the next time a comet would pass by again

- Newton summarized his discoveries in Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (mathematical principles of natural philosophy) (1687)

- It shows his principle of universal gravitation and provided an explanation both of falling bodies on the Earth and of the motions of planets, comets and other bodies of the universe.

- Opticks (1704) presented his discoveries of light and elaborated his theory that light is composed of corpuscles, or particles.

- Isaac Newton died on March 31, 1727 in London, England

- Isaac Newton (The Last Sorcerer), by Michael White

- Encyclopedia Article

- The New Encyclopedia Britannica Volume 8. Micropaedia/Ready Reference pg. 663

- A source of scientific period

- The Scientists of The Scientific Revolution pg. 69-87

- Internet source

- Newton, Isaac. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001 _at_ www. Bartleby.com

PowerShow.com is a leading presentation sharing website. It has millions of presentations already uploaded and available with 1,000s more being uploaded by its users every day. Whatever your area of interest, here you’ll be able to find and view presentations you’ll love and possibly download. And, best of all, it is completely free and easy to use.

You might even have a presentation you’d like to share with others. If so, just upload it to PowerShow.com. We’ll convert it to an HTML5 slideshow that includes all the media types you’ve already added: audio, video, music, pictures, animations and transition effects. Then you can share it with your target audience as well as PowerShow.com’s millions of monthly visitors. And, again, it’s all free.

About the Developers

PowerShow.com is brought to you by CrystalGraphics , the award-winning developer and market-leading publisher of rich-media enhancement products for presentations. Our product offerings include millions of PowerPoint templates, diagrams, animated 3D characters and more.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) is best known for having invented the calculus in the mid to late 1660s (most of a decade before Leibniz did so independently, and ultimately more influentially) and for having formulated the theory of universal gravity — the latter in his Principia , the single most important work in the transformation of early modern natural philosophy into modern physical science. Yet he also made major discoveries in optics beginning in the mid-1660s and reaching across four decades; and during the course of his 60 years of intense intellectual activity he put no less effort into chemical and alchemical research and into theology and biblical studies than he put into mathematics and physics. He became a dominant figure in Britain almost immediately following publication of his Principia in 1687, with the consequence that “Newtonianism” of one form or another had become firmly rooted there within the first decade of the eighteenth century. His influence on the continent, however, was delayed by the strong opposition to his theory of gravity expressed by such leading figures as Christiaan Huygens and Leibniz, both of whom saw the theory as invoking an occult power of action at a distance in the absence of Newton's having proposed a contact mechanism by means of which forces of gravity could act. As the promise of the theory of gravity became increasingly substantiated, starting in the late 1730s but especially during the 1740s and 1750s, Newton became an equally dominant figure on the continent, and “Newtonianism,” though perhaps in more guarded forms, flourished there as well. What physics textbooks now refer to as “Newtonian mechanics” and “Newtonian science” consists mostly of results achieved on the continent between 1740 and 1800.

1.1 Newton's Early Years

1.2 newton's years at cambridge prior to principia, 1.3 newton's final years at cambridge, 1.4 newton's years in london and his final years, 2. newton's work and influence, primary sources, secondary sources, other internet resources, related entries, 1. newton's life.

Newton's life naturally divides into four parts: the years before he entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1661; his years in Cambridge before the Principia was published in 1687; a period of almost a decade immediately following this publication, marked by the renown it brought him and his increasing disenchantment with Cambridge; and his final three decades in London, for most of which he was Master of the Mint. While he remained intellectually active during his years in London, his legendary advances date almost entirely from his years in Cambridge. Nevertheless, save for his optical papers of the early 1670s and the first edition of the Principia , all his works published before he died fell within his years in London. [ 1 ]

Newton was born into a Puritan family in Woolsthorpe, a small village in Linconshire near Grantham, on 25 December 1642 (old calendar), a few days short of one year after Galileo died. Isaac's father, a farmer, died two months before Isaac was born. When his mother Hannah married the 63 year old Barnabas Smith three years later and moved to her new husband's residence, Isaac was left behind with his maternal grandparents. (Isaac learned to read and write from his maternal grandmother and mother, both of whom, unlike his father, were literate.) Hannah returned to Woolsthorpe with three new children in 1653, after Smith died. Two years later Isaac went to boarding school in Grantham, returning full time to manage the farm, not very successfully, in 1659. Hannah's brother, who had received an M.A. from Cambridge, and the headmaster of the Grantham school then persuaded his mother that Isaac should prepare for the university. After further schooling at Grantham, he entered Trinity College in 1661, somewhat older than most of his classmates.

These years of Newton's youth were the most turbulent in the history of England. The English Civil War had begun in 1642, King Charles was beheaded in 1649, Oliver Cromwell ruled as lord protector from 1653 until he died in 1658, followed by his son Richard from 1658 to 1659, leading to the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660. How much the political turmoil of these years affected Newton and his family is unclear, but the effect on Cambridge and other universities was substantial, if only through unshackling them for a period from the control of the Anglican Catholic Church. The return of this control with the restoration was a key factor inducing such figures as Robert Boyle to turn to Charles II for support for what in 1660 emerged as the Royal Society of London. The intellectual world of England at the time Newton matriculated to Cambridge was thus very different from what it was when he was born.

Newton's initial education at Cambridge was classical, focusing (primarily through secondary sources) on Aristotlean rhetoric, logic, ethics, and physics. By 1664, Newton had begun reaching beyond the standard curriculum, reading, for example, the 1656 Latin edition of Descartes's Opera philosophica , which included the Meditations , Discourse on Method , the Dioptrics , and the Principles of Philosophy . By early 1664 he had also begun teaching himself mathematics, taking notes on works by Oughtred, Viète, Wallis, and Descartes — the latter via van Schooten's Latin translation, with commentary, of the Géométrie . Newton spent all but three months from the summer of 1665 until the spring of 1667 at home in Woolsthorpe when the university was closed because of the plague. This period was his so-called annus mirabilis . During it, he made his initial experimental discoveries in optics and developed (independently of Huygens's treatment of 1659) the mathematical theory of uniform circular motion, in the process noting the relationship between the inverse-square and Kepler's rule relating the square of the planetary periods to the cube of their mean distance from the Sun. Even more impressively, by late 1666 he had become de facto the leading mathematician in the world, having extended his earlier examination of cutting-edge problems into the discovery of the calculus, as presented in his tract of October 1666. He returned to Trinity as a Fellow in 1667, where he continued his research in optics, constructing his first reflecting telescope in 1669, and wrote a more extended tract on the calculus “De Analysi per Æquations Numero Terminorum Infinitas” incorporating new work on infinite series. On the basis of this tract Isaac Barrow recommended Newton as his replacement as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, a position he assumed in October 1669, four and a half years after he had received his Bachelor of Arts.

Over the course of the next fifteen years as Lucasian Professor Newton presented his lectures and carried on research in a variety of areas. By 1671 he had completed most of a treatise length account of the calculus, [ 2 ] which he then found no one would publish. This failure appears to have diverted his interest in mathematics away from the calculus for some time, for the mathematical lectures he registered during this period mostly concern algebra. (During the early 1680s he undertook a critical review of classical texts in geometry, a review that reduced his view of the importance of symbolic mathematics.) His lectures from 1670 to 1672 concerned optics, with a large range of experiments presented in detail. Newton went public with his work in optics in early 1672, submitting material that was read before the Royal Society and then published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society . This led to four years of exchanges with various figures who challenged his claims, including both Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens — exchanges that at times exasperated Newton to the point that he chose to withdraw from further public exchanges in natural philosophy. Before he largely isolated himself in the late 1670s, however, he had also engaged in a series of sometimes long exchanges in the mid 1670s, most notably with John Collins (who had a copy of “De Analysi”) and Leibniz, concerning his work on the calculus. So, though they remained unpublished, Newton's advances in mathematics scarcely remained a secret.

This period as Lucasian Professor also marked the beginning of his more private researches in alchemy and theology. Newton purchased chemical apparatus and treatises in alchemy in 1669, with experiments in chemistry extending across this entire period. The issue of the vows Newton might have to take in conjunction with the Lucasian Professorship also appears to have precipitated his study of the doctrine of the Trinity, which opened the way to his questioning the validity of a good deal more doctrine central to the Roman and Anglican Churches.

Newton showed little interest in orbital astronomy during this period until Hooke initiated a brief correspondence with him in an effort to solicit material for the Royal Society at the end of November 1679, shortly after Newton had returned to Cambridge following the death of his mother. Among the several problems Hooke proposed to Newton was the question of the trajectory of a body under an inverse-square central force:

It now remaines to know the proprietys of a curve Line (not circular nor concentricall) made by a centrall attractive power which makes the velocitys of Descent from the tangent Line or equall straight motion at all Distances in a Duplicate proportion to the Distances Reciprocally taken. I doubt not but that by your excellent method you will easily find out what the Curve must be, and it proprietys, and suggest a physicall Reason of this proportion. [ 3 ]

Newton apparently discovered the systematic relationship between conic-section trajectories and inverse-square central forces at the time, but did not communicate it to anyone, and for reasons that remain unclear did not follow up this discovery until Halley, during a visit in the summer of 1684, put the same question to him. His immediate answer was, an ellipse; and when he was unable to produce the paper on which he had made this determination, he agreed to forward an account to Halley in London. Newton fulfilled this commitment in November by sending Halley a nine-folio-page manuscript, “De Motu Corporum in Gyrum” (“On the Motion of Bodies in Orbit”), which was entered into the Register of the Royal Society in early December 1684. The body of this tract consists of ten deduced propositions — three theorems and seven problems — all of which, along with their corollaries, recur in important propositions in the Principia .

Save for a few weeks away from Cambridge, from late 1684 until early 1687, Newton concentrated on lines of research that expanded the short ten-proposition tract into the 500 page Principia , with its 192 derived propositions. Initially the work was to have a two book structure, but Newton subsequently shifted to three books, and replaced the original version of the final book with one more mathematically demanding. The manuscript for Book 1 was sent to London in the spring of 1686, and the manuscripts for Books 2 and 3, in March and April 1687, respectively. The roughly three hundred copies of the Principia came off the press in the summer of 1687, thrusting the 44 year old Newton into the forefront of natural philosophy and forever ending his life of comparative isolation.

The years between the publication of the Principia and Newton's permanent move to London in 1696 were marked by his increasing disenchantment with his situation in Cambridge. In January 1689, following the Glorious Revolution at the end of 1688, he was elected to represent Cambridge University in the Convention Parliament, which he did until January 1690. During this time he formed friendships with John Locke and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, and in the summer of 1689 he finally met Christiaan Huygens face to face for two extended discussions. Perhaps because of disappointment with Huygens not being convinced by the argument for universal gravity, in the early 1690s Newton initiated a radical rewriting of the Principia . During these same years he wrote (but withheld) his principal treatise in alchemy, Praxis ; he corresponded with Richard Bentley on religion and allowed Locke to read some of his writings on the subject; he once again entered into an effort to put his work on the calculus in a form suitable for publication; and he carried out experiments on diffraction with the intent of completing his Opticks , only to withhold the manuscript from publication because of dissatisfaction with its treatment of diffraction. The radical revision of the Principia became abandoned by 1693, during the middle of which Newton suffered, by his own testimony, what in more recent times would be called a nervous breakdown. In the two years following his recovery that autumn, he continued his experiments in chymistry and he put substantial effort into trying to refine and extend the gravity-based theory of the lunar orbit in the Principia , but with less success than he had hoped.

Throughout these years Newton showed interest in a position of significance in London, but again with less success than he had hoped until he accepted the relatively minor position of Warden of the Mint in early 1696, a position he held until he became Master of the Mint at the end of 1699. He again represented Cambridge University in Parliament for 16 months, beginning in 1701, the year in which he resigned his Fellowship at Trinity College and the Lucasian Professorship. He was elected President of the Royal Society in 1703 and was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705.

Newton thus became a figure of imminent authority in London over the rest of his life, in face-to-face contact with individuals of power and importance in ways that he had not known in his Cambridge years. His everyday home life changed no less dramatically when his extraordinarily vivacious teenage niece, Catherine Barton, the daughter of his half-sister Hannah, moved in with him shortly after he moved to London, staying until she married John Conduitt in 1717, and after that remaining in close contact. (It was through her and her husband that Newton's papers came down to posterity.) Catherine was socially prominent among the powerful and celebrated among the literati for the years before she married, and her husband was among the wealthiest men of London.

The London years saw Newton embroiled in some nasty disputes, probably made the worse by the ways in which he took advantage of his position of authority in the Royal Society. In the first years of his Presidency he became involved in a dispute with John Flamsteed in which he and Halley, long ill-disposed toward the Flamsteed, violated the trust of the Royal Astronomer, turning him into a permanent enemy. Ill feelings between Newton and Leibniz had been developing below the surface from even before Huygens had died in 1695, and they finally came to a head in 1710 when John Keill accused Leibniz in the Philosophical Transactions of having plagiarized the calculus from Newton and Leibniz, a Fellow of the Royal Society since 1673, demanded redress from the Society. The Society's 1712 published response was anything but redress. Newton not only was a dominant figure in this response, but then published an outspoken anonymous review of it in 1715 in the Philosophical Transactions . Leibniz and his colleagues on the Continent had never been comfortable with the Principia and its implication of action at a distance. With the priority dispute this attitude turned into one of open hostility toward Newton's theory of gravity — a hostility that was matched in its blindness by the fervor of acceptance of the theory in England. The public elements of the priority dispute had the effect of expanding a schism between Newton and Leibniz into a schism between the English associated with the Royal Society and the group who had been working with Leibniz on the calculus since the 1690s, including most notably Johann Bernoulli, and this schism in turn transformed into one between the conduct of science and mathematics in England versus the Continent that persisted long after Leibniz died in 1716.

Although Newton obviously had far less time available to devote to solitary research during his London years than he had had in Cambridge, he did not entirely cease to be productive. The first (English) edition of his Opticks finally appeared in 1704, appended to which were two mathematical treatises, his first work on the calculus to appear in print. This edition was followed by a Latin edition in 1706 and a second English edition in 1717, each containing important Queries on key topics in natural philosophy beyond those in its predecessor. Other earlier work in mathematics began to appear in print, including a work on algebra, Arithmetica Universalis , in 1707 and “De Analysi” and a tract on finite differences, “Methodis differentialis” in 1711. The second edition of the Principia , on which Newton had begun work at the age of 66 in 1709, was published in 1713, with a third edition in 1726. Though the original plan for a radical restructuring had long been abandoned, the fact that virtually every page of the Principia received some modifications in the second edition shows how carefully Newton, often prodded by his editor Roger Cotes, reconsidered everything in it; and important parts were substantially rewritten not only in response to Continental criticisms, but also because of new data, including data from experiments on resistance forces carried out in London. Focused effort on the third edition began in 1723, when Newton was 80 years old, and while the revisions are far less extensive than in the second edition, it does contain substantive additions and modfications, and it surely has claim to being the edition that represents his most considered views.

Newton died on 20 March 1727 at the age of 84. His contemporaries' conception of him nevertheless continued to expand as a consequence of various posthumous publications, including The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728); the work originally intended to be the last book of the Principia , The System of the World (1728, in both English and Latin); Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733); A Treatise of the Method of Fluxions and Infinite Series (1737); A Dissertation upon the Sacred Cubit of the Jews (1737), and Four Letters from Sir Isaac Newton to Doctor Bentley concerning Some Arguments in Proof of a Deity (1756). Even then, however, the works that had been published represented only a limited fraction of the total body of papers that had been left in the hands of Catherine and John Conduitt. The five volume collection of Newton's works edited by Samuel Horsley (1779–85) did not alter this situation. Through the marriage of the Conduitts' daughter Catherine and subsequent inheritance, this body of papers came into the possession of Lord Portsmouth, who agreed in 1872 to allow it to be reviewed by scholars at Cambridge University (John Couch Adams, George Stokes, H. R. Luard, and G. D. Liveing). They issued a catalogue in 1888, and the university then retained all the papers of a scientific character. With the notable exception of W. W. Rouse Ball, little work was done on the scientific papers before World War II. The remaining papers were returned to Lord Portsmouth, and then ultimately sold at auction in 1936 to various parties. Serious scholarly work on them did not get underway until the 1970s, and much remains to be done on them.

Three factors stand in the way of giving an account of Newton's work and influence. First is the contrast between the public Newton, consisting of publications in his lifetime and in the decade or two following his death, and the private Newton, consisting of his unpublished work in math and physics, his efforts in chymistry — that is, the 17th century blend of alchemy and chemistry — and his writings in radical theology — material that has become public mostly since World War II. Only the public Newton influenced the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, yet any account of Newton himself confined to this material can at best be only fragmentary. Second is the contrast, often shocking, between the actual content of Newton's public writings and the positions attributed to him by others, including most importantly his popularizers. The term “Newtonian” refers to several different intellectual strands unfolding in the eighteenth century, some of them tied more closely to Voltaire, Pemberton, and Maclaurin — or for that matter to those who saw themselves as extending his work, such as Clairaut, Euler, d'Alembert, Lagrange, and Laplace — than to Newton himself. Third is the contrast between the enormous range of subjects to which Newton devoted his full concentration at one time or another during the 60 years of his intellectual career — mathematics, optics, mechanics, astronomy, experimental chemistry, alchemy, and theology — and the remarkably little information we have about what drove him or his sense of himself. Biographers and analysts who try to piece together a unified picture of Newton and his intellectual endeavors often end up telling us almost as much about themselves as about Newton.

Compounding the diversity of the subjects to which Newton devoted time are sharp contrasts in his work within each subject. Optics and orbital mechanics both fall under what we now call physics, and even then they were seen as tied to one another, as indicated by Descartes' first work on the subject, Le Monde, ou Traité de la lumierè . Nevertheless, two very different “Newtonian” traditions in physics arose from Newton's Opticks and Principia : from his Opticks a tradition centered on meticulous experimentation and from his Principia a tradition centered on mathematical theory. The most important element common to these two was Newton's deep commitment to having the empirical world serve not only as the ultimate arbiter, but also as the sole basis for adopting provisional theory. Throughout all of this work he displayed distrust of what was then known as the method of hypotheses – putting forward hypotheses that reach beyond all known phenomena and then testing them by deducing observable conclusions from them. Newton insisted instead on having specific phenomena decide each element of theory, with the goal of limiting the provisional aspect of theory as much as possible to the step of inductively generalizing from the specific phenomena. This stance is perhaps best summarized in his fourth Rule of Reasoning, added in the third edition of the Principia , but adopted as early as his Optical Lectures of the 1670s:

In experimental philosophy, propositions gathered from phenomena by induction should be taken to be either exactly or very nearly true notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses, until yet other phenomena make such propositions either more exact or liable to exceptions. This rule should be followed so that arguments based on induction may not be nullified by hypotheses.

Such a commitment to empirically driven science was a hallmark of the Royal Society from its very beginnings, and one can find it in the research of Kepler, Galileo, Huygens, and in the experimental efforts of the Royal Academy of Paris. Newton, however, carried this commitment further first by eschewing the method of hypotheses and second by displaying in his Principia and Opticks how rich a set of theoretical results can be secured through well-designed experiments and mathematical theory designed to allow inferences from phenomena. The success of those after him in building on these theoretical results completed the process of transforming natural philosophy into modern empirical science.

Newton's commitment to having phenomena decide the elements of theory required questions to be left open when no available phenomena could decide them. Newton contrasted himself most strongly with Leibniz in this regard at the end of his anonymous review of the Royal Society's report on the priority dispute over the calculus:

It must be allowed that these two Gentlemen differ very much in Philosophy. The one proceeds upon the Evidence arising from Experiments and Phenomena, and stops where such Evidence is wanting; the other is taken up with Hypotheses, and propounds them, not to be examined by Experiments, but to be believed without Examination. The one for want of Experiments to decide the Question, doth not affirm whether the Cause of Gravity be Mechanical or not Mechanical; the other that it is a perpetual Miracle if it be not Mechanical.

Newton could have said much the same about the question of what light consists of, waves or particles, for while he felt that the latter was far more probable, he saw it still not decided by any experiment or phenomenon in his lifetime. Leaving questions about the ultimate cause of gravity and the constitution of light open was the other factor in his work driving a wedge between natural philosophy and empirical science.

The many other areas of Newton's intellectual endeavors made less of a difference to eighteenth century philosophy and science. In mathematics, Newton was the first to develop a full range of algorithms for symbolically determining what we now call integrals and derivatives, but he subsequently became fundamentally opposed to the idea, championed by Leibniz, of transforming mathematics into a discipline grounded in symbol manipulation. Newton thought the only way of rendering limits rigorous lay in extending geometry to incorporate them, a view that went entirely against the tide in the development of mathematics in the eighteenth and nineteenth ceturies. In chemistry Newton conducted a vast array of experiments, but the experimental tradition coming out of his Opticks , and not his experiments in chemistry, lay behind Lavoisier calling himself a Newtonian; indeed, one must wonder whether Lavoisier would even have associated his new form of chemistry with Newton had he been aware of Newton's fascination with writings in the alchemical tradition. And even in theology, there is Newton the anti-Trinitarian mild heretic who was not that much more radical in his departures from Roman and Anglican Christianity than many others at the time, and Newton, the wild religious zealot predicting the end of the Earth, who did not emerge to public view until quite recently.

There is surprisingly little cross-referencing of themes from one area of Newton's endeavors to another. The common element across almost all of them is that of a problem-solver extraordinaire , taking on one problem at a time and staying with it until he had found, usually rather promptly, a solution. All of his technical writings display this, but so too does his unpublished manuscript reconstructing Solomon's Temple from the biblical account of it and his posthumously published Chronology of the Ancient Kingdoms in which he attempted to infer from astronomical phenomena the dating of major events in the Old Testament. The Newton one encounters in his writings seems to compartmentalize his interests at any given moment. Whether he had a unified conception of what he was up to in all his intellectual efforts, and if so what this conception might be, has been a continuing source of controversy among Newton scholars.

Of course, were it not for the Principia , there would be no entry at all for Newton in an Encyclopedia of Philosophy. In science, he would have been known only for the contributions he made to optics, which, while notable, were no more so than those made by Huygens and Grimaldi, neither of whom had much impact on philosophy; and in mathematics, his failure to publish would have relegated his work to not much more than a footnote to the achievements of Leibniz and his school. Regardless of which aspect of Newton's endeavors “Newtonian” might be applied to, the word gained its aura from the Principia . But this adds still a further complication, for the Principia itself was substantially different things to different people. The press-run of the first edition (estimated to be around 300) was too small for it to have been read by all that many individuals. The second edition also appeared in two pirated Amsterdam editions, and hence was much more widely available, as was the third edition and its English (and later French) translation. The Principia , however, is not an easy book to read, so one must still ask, even of those who had access to it, whether they read all or only portions of the book and to what extent they grasped the full complexity of what they read. The detailed commentary provided in the three volume Jesuit edition (1739–42) made the work less daunting. But even then the vast majority of those invoking the word “Newtonian” were unlikely to have been much more conversant with the Principia itself than those in the first half of the 20th century who invoked ‘relativity’ were likely to have read Einstein's two special relativity papers of 1905 or his general relativity paper of 1916. An important question to ask of any philosophers commenting on Newton is, what primary sources had they read?

The 1740s witnessed a major transformation in the standing of the science in the Principia . The Principia itself had left a number of loose-ends, most of them detectable by only highly discerning readers. By 1730, however, some of these loose-ends had been cited in Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle's elogium for Newton [ 4 ] and in John Machin's appendix to the 1729 English translation of the Principia , raising questions about just how secure Newton's theory of gravity was, empirically. The shift on the continent began in the 1730s when Maupertuis convinced the Royal Academy to conduct expeditions to Lapland and Peru to determine whether Newton's claims about the non-spherical shape of the Earth and the variation of surface gravity with latitude are correct. Several of the loose-ends were successfully resolved during the 1740's through such notable advances beyond the Principia as Clairaut's Théorie de la Figure de la Terre ; the return of the expedition from Peru; d'Alembert's 1749 rigid-body solution for the wobble of the Earth that produces the precession of the equinoxes; Clairaut's 1749 resolution of the factor of 2 discrepancy between theory and observation in the mean motion of the lunar apogee, glossed over by Newton but emphasized by Machin; and the prize-winning first ever successful description of the motion of the Moon by Tobias Mayer in 1753, based on a theory of this motion derived from gravity by Euler in the early 1750s taking advantage of Clairaut's solution for the mean motion of the apogee.

Euler was the central figure in turning the three laws of motion put forward by Newton in the Principia into Newtonian mechanics. These three laws, as Newton formulated them, apply to “point-masses,” a term Euler had put forward in his Mechanica of 1736. Most of the effort of eighteenth century mechanics was devoted to solving problems of the motion of rigid bodies, elastic strings and bodies, and fluids, all of which require principles beyond Newton's three laws. From the 1740s on this led to alternative approaches to formulating a general mechanics, employing such different principles as the conservation of vis viva , the principle of least action, and d'Alembert's principle. The “Newtonian” formulation of a general mechanics sprang from Euler's proposal in 1750 that Newton's second law, in an F=ma formulation that appears nowhere in the Principia , could be applied locally within bodies and fluids to yield differential equations for the motions of bodies, elastic and rigid, and fluids. During the 1750s Euler developed his equations for the motion of fluids, and in the 1760s, his equations of rigid-body motion. What we call Newtonian mechanics was accordingly something for which Euler was more responsible than Newton.

Although some loose-ends continued to defy resolution until much later in the eighteenth century, by the early 1750s Newton's theory of gravity had become the accepted basis for ongoing research among almost everyone working in orbital astronomy. Clairaut's successful prediction of the month of return of Halley's comet at the end of this decade made a larger segment of the educated public aware of the extent to which empirical grounds for doubting Newton's theory of gravity had largely disappeared. Even so, one must still ask of anyone outside active research in gravitational astronomy just how aware they were of the developments from ongoing efforts when they made their various pronouncements about the standing of the science of the Principia among the community of researchers. The naivety of these pronouncements cuts both ways: on the one hand, they often reflected a bloated view of how secure Newton's theory was at the time, and, on the other, they often underestimated how strong the evidence favoring it had become. The upshot is a need to be attentive to the question of what anyone, even including Newton himself, had in mind when they spoke of the science of the Principia .

To view the seventy years of research after Newton died as merely tying up the loose-ends of the Principia or as simply compiling more evidence for his theory of gravity is to miss the whole point. Research predicated on Newton's theory had answered a huge number of questions about the world dating from long before it. The motion of the Moon and the trajectories of comets were two early examples, both of which answered such questions as how one comet differs from another and what details make the Moon's motion so much more complicated than that of the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn. In the 1770s Laplace had developed a proper theory of the tides, reaching far beyond the suggestions Newton had made in the Principia by including the effects of the Earth's rotation and the non-radial components of the gravitational forces of the Sun and Moon, components that dominate the radial component that Newton had singled out. In 1786 Laplace identified a large 900 year fluctuation in the motions of Jupiter and Saturn arising from quite subtle features of their respective orbits. With this discovery, calculation of the motion of the planets from the theory of gravity became the basis for predicting planet positions, with observation serving primarily to identify further forces not yet taken into consideration in the calculation. These advances in our understanding of planetary motion led Laplace to produce the four principal volumes of his Traité de mécanique céleste from 1799 to 1805, a work collecting in one place all the theoretical and empirical results of the research predicated on Newton's Principia . From that time forward, Newtonian science sprang from Laplace's work, not Newton's.

The success of the research in celestial mechanics predicated on the Principia was unprecedented. Nothing of comparable scope and accuracy had ever occurred before in empirical research of any kind. That led to a new philosophical question: what was it about the science of the Principia that enabled it to achieve what it did? Philosophers like Locke and Berkeley began asking this question while Newton was still alive, but it gained increasing force as successes piled on one another over the decades after he died. This question had a practical side, as those working in other fields like chemistry pursued comparable success, and others like Hume and Adam Smith aimed for a science of human affairs. It had, of course, a philosophical side, giving rise to the subdiscipline of philosophy of science, starting with Kant and continuing throughout the nineteenth century as other areas of physical science began showing similar signs of success. The Einsteinian revolution in the beginning of the twentieth century, in which Newtonian theory was shown to hold only as a limiting case of the special and general theories of relativity, added a further twist to the question, for now all the successes of Newtonian science, which still remain in place, have to be seen as predicated on a theory that holds only to high approximation in parochial circumstances.

The extraordinary character of the Principia gave rise to a still continuing tendency to place great weight on everything Newton said. This, however, was, and still is, easy to carry to excess. One need look no further than Book 2 of the Principia to see that Newton had no more claim to being somehow in tune with nature and the truth than any number of his contemporaries. Newton's manuscripts do reveal an exceptional level of attention to detail of phrasing, from which we can rightly conclude that his pronouncements, especially in print, were generally backed by careful, self-critical reflection. But this conclusion does not automatically extend to every statement he ever made. We must constantly be mindful of the possibility of too much weight being placed, then or now, on any pronouncement that stands in relative isolation over his 60 year career; and, to counter the tendency to excess, we should be even more vigilant than usual in not losing sight of the context, circumstantial as well as historical and textual, of both Newton's statements and the eighteenth century reaction to them.

- Westfall, Richard S., 1980, Never At Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton , New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, A. Rupert, 1992 , Isaac Newton: Adventurer in Thought , Oxford: Blackwell.

- Feingold, Mordechai, 2004 , The Newtonian Moment: Isaac Newton and the Making of Modern Culture , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Iliffe, Rob, 2007, Newton: A Very Short Introduction Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, I. B. and Smith, G. E., 2002, The Cambridge Companion to Newton , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohen, I. B. and Westfall, R. S., 1995, Newton: Texts, Backgrounds, and Commentaries , A Norton Critical Edition, New York: Norton.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive

- The Newton Project

- The Newton Project-Canada

- The Chymistry of Isaac Newton , Digital Library at Indiana

Copernicus, Nicolaus | Descartes, René | Kant, Immanuel | Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm | Newton, Isaac: Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica | scientific revolutions | trinity | Whewell, William

Copyright © 2007 by George Smith < george . smith @ tufts . edu >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2024 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

All About Isaac Newton Biography PowerPoint Lesson for 3rd 4th 5th Grade

Description

Step into the extraordinary world of Isaac Newton with our comprehensive Biography PowerPoint Lesson designed for 3rd, 4th, and 5th-grade students. This engaging educational resource takes students on a captivating journey through the life and achievements of one of history's greatest scientists.

Through visually stunning slides, informative text, and interactive activities, students will explore the fascinating story of Isaac Newton's life, from his early years to his groundbreaking scientific discoveries. Each slide is carefully crafted to provide valuable insights into Newton's childhood, education, and contributions to science and mathematics.

The PowerPoint lesson covers key aspects of Newton's biography, including his early curiosity, struggles, and moments of inspiration that led to his remarkable scientific breakthroughs. Students will learn about Newton's laws of motion, law of universal gravitation, and contributions to optics and mathematics, all while gaining a deeper understanding of the scientific method and the process of discovery.

Interactive elements such as quizzes, discussion prompts, and hands-on experiments engage students and foster active participation in their learning experience. Teachers can seamlessly integrate this lesson into their science or history curriculum to enhance students' understanding of Isaac Newton and his significance in the history of science.

With its captivating visuals, informative content, and interactive features, this Biography PowerPoint Lesson is sure to captivate the imaginations of 3rd, 4th, and 5th-grade students, inspiring them to explore the wonders of science and the life of one of its greatest pioneers, Isaac Newton.

Questions & Answers

Curriculum corner store.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- Scientific Methods

- Famous Physicists

- Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton

Apart from discovering the cause of the fall of an apple from a tree, that is, the laws of gravity, Sir Isaac Newton was perhaps one of the most brilliant and greatest physicists of all time. He shaped dramatic and surprising discoveries in the laws of physics that we believe our universe obeys, and hence it changed the way we appreciate and relate to the world around us.

Table of Contents

About sir isaac newton, sir isaac newton’s education, awards and achievements, some achievements of isaac newton in brief.

- Universal Law of Gravitation

Optics and Light

Sir Isaac Newton was born on 4th January 1643 in a small village of England called Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth. He was an English physicist and mathematician, and one of the important thinkers in the Scientific Revolution.

He discovered the phenomenon of white light integrated with colours which further laid the foundation of modern physical optics. His famous three laws of Motion in mechanics and the formulation of the laws of gravitation completely changed the track of physics across the globe. He was the originator of calculus in mathematics. A scientist like him is considered an excellent gift by nature to the world of physics.

Isaac Newton studied at the Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1661. At 22 in 1665, a year after beginning his four-year scholarship, Newton finished his first significant discovery in mathematics, where he revealed the generalized binomial theorem. He was bestowed with his B.A. degree in the same year.

Isaac Newton held numerous positions throughout his life. In 1671, he was invited to join the Royal Society of London after developing a new and enhanced version of the reflecting telescope.

He was later elected President of the Royal Society (1703). Sir Isaac Newton ran for a seat in Parliament in 1689. He won the election and became a Member of Parliament for Cambridge University. He was also appointed as a Warden of the Mint in 1969. Due to his exemplary work and dedication to the mint, he was chosen Master of the Mint in 1700. After being knighted in 1705, he was known as “Sir Isaac Newton.”

His mind was ablaze with original ideas. He made significant progress in three distinct fields – with some of the most profound discoveries in:

- Calculus, the mathematics of change, which is vital to our understanding of the world around us

- Optics and the behaviour of light

- He also built the first working reflecting telescope

- He showed that Kepler’s laws of planetary motion are exceptional cases of Newton’s universal gravitation.

Sir Isaac Newton’s Contribution in Calculus

Sir Isaac Newton was the first individual to develop calculus. Modern physics and physical chemistry are almost impossible without calculus, as it is the mathematics of change.

The idea of differentiating calculus into differential calculus, integral calculus and differential equations came from Newton’s fertile mind. Today, most mathematicians give equal credit to Newton and Leibniz for calculus’s discovery.

Law of Universal Gravitation

The famous apple that he saw falling from a tree led him to discover the force of gravitation and its laws. Ultimately, he realised that the pressure causing the apple’s fall is responsible for the moon to orbit the earth, as well as comets and other planets to revolve around the sun. The force can be felt throughout the universe. Hence, Newton called it the Universal Law of Gravitation .

Newton discovered the equation that allows us to compute the force of gravity between two objects.

Newton’s Laws of Motion

- First law of Motion

- Second Law of Motion

- Third law of Motion

Watch the video and learn about the history of the concept of Gravitation