How to Begin an Essay: 13 Engaging Strategies

ThoughtCo / Hugo Lin

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

An effective introductory paragraph both informs and motivates. It lets readers know what your essay is about and it encourages them to keep reading.

There are countless ways to begin an essay effectively. As a start, here are 13 introductory strategies accompanied by examples from a wide range of professional writers.

State Your Thesis Briefly and Directly

But avoid making your thesis a bald announcement, such as "This essay is about...".

"It is time, at last, to speak the truth about Thanksgiving, and the truth is this. Thanksgiving is really not such a terrific holiday...." (Michael J. Arlen, "Ode to Thanksgiving." The Camera Age: Essays on Television . Penguin, 1982)

Pose a Question Related to Your Subject

Follow up the question with an answer, or an invitation for your readers to answer the question.

"What is the charm of necklaces? Why would anyone put something extra around their neck and then invest it with special significance? A necklace doesn't afford warmth in cold weather, like a scarf, or protection in combat, like chain mail; it only decorates. We might say, it borrows meaning from what it surrounds and sets off, the head with its supremely important material contents, and the face, that register of the soul. When photographers discuss the way in which a photograph reduces the reality it represents, they mention not only the passage from three dimensions to two, but also the selection of a point de vue that favors the top of the body rather than the bottom, and the front rather than the back. The face is the jewel in the crown of the body, and so we give it a setting." (Emily R. Grosholz, "On Necklaces." Prairie Schooner , Summer 2007)

State an Interesting Fact About Your Subject

" The peregrine falcon was brought back from the brink of extinction by a ban on DDT, but also by a peregrine falcon mating hat invented by an ornithologist at Cornell University. If you cannot buy this, Google it. Female falcons had grown dangerously scarce. A few wistful males nevertheless maintained a sort of sexual loitering ground. The hat was imagined, constructed, and then forthrightly worn by the ornithologist as he patrolled this loitering ground, singing, Chee-up! Chee-up! and bowing like an overpolite Japanese Buddhist trying to tell somebody goodbye...." (David James Duncan, "Cherish This Ecstasy." The Sun , July 2008)

Present Your Thesis as a Recent Discovery or Revelation

"I've finally figured out the difference between neat people and sloppy people. The distinction is, as always, moral. Neat people are lazier and meaner than sloppy people." (Suzanne Britt Jordan, "Neat People vs. Sloppy People." Show and Tell . Morning Owl Press, 1983)

Briefly Describe the Primary Setting of Your Essay

"It was in Burma, a sodden morning of the rains. A sickly light, like yellow tinfoil, was slanting over the high walls into the jail yard. We were waiting outside the condemned cells, a row of sheds fronted with double bars, like small animal cages. Each cell measured about ten feet by ten and was quite bare within except for a plank bed and a pot of drinking water. In some of them brown silent men were squatting at the inner bars, with their blankets draped round them. These were the condemned men, due to be hanged within the next week or two." (George Orwell, "A Hanging," 1931)

Recount an Incident That Dramatizes Your Subject

"One October afternoon three years ago while I was visiting my parents, my mother made a request I dreaded and longed to fulfill. She had just poured me a cup of Earl Grey from her Japanese iron teapot, shaped like a little pumpkin; outside, two cardinals splashed in the birdbath in the weak Connecticut sunlight. Her white hair was gathered at the nape of her neck, and her voice was low. “Please help me get Jeff’s pacemaker turned off,” she said, using my father’s first name. I nodded, and my heart knocked." (Katy Butler, "What Broke My Father's Heart." The New York Times Magazine , June 18, 2010)

Use the Narrative Strategy of Delay

The narrative strategy of delay allows you to put off identifying your subject just long enough to pique your readers' interest without frustrating them.

"They woof. Though I have photographed them before, I have never heard them speak, for they are mostly silent birds. Lacking a syrinx, the avian equivalent of the human larynx, they are incapable of song. According to field guides the only sounds they make are grunts and hisses, though the Hawk Conservancy in the United Kingdom reports that adults may utter a croaking coo and that young black vultures, when annoyed, emit a kind of immature snarl...." (Lee Zacharias, "Buzzards." Southern Humanities Review , 2007)

Use the Historical Present Tense

An effective method of beginning an essay is to use historical present tense to relate an incident from the past as if it were happening now.

"Ben and I are sitting side by side in the very back of his mother’s station wagon. We face glowing white headlights of cars following us, our sneakers pressed against the back hatch door. This is our joy—his and mine—to sit turned away from our moms and dads in this place that feels like a secret, as though they are not even in the car with us. They have just taken us out to dinner, and now we are driving home. Years from this evening, I won’t actually be sure that this boy sitting beside me is named Ben. But that doesn’t matter tonight. What I know for certain right now is that I love him, and I need to tell him this fact before we return to our separate houses, next door to each other. We are both five." (Ryan Van Meter, "First." The Gettysburg Review , Winter 2008)

Briefly Describe a Process That Leads Into Your Subject

"I like to take my time when I pronounce someone dead. The bare-minimum requirement is one minute with a stethoscope pressed to someone’s chest, listening for a sound that is not there; with my fingers bearing down on the side of someone’s neck, feeling for an absent pulse; with a flashlight beamed into someone’s fixed and dilated pupils, waiting for the constriction that will not come. If I’m in a hurry, I can do all of these in sixty seconds, but when I have the time, I like to take a minute with each task." (Jane Churchon, "The Dead Book." The Sun , February 2009)

Reveal a Secret or Make a Candid Observation

"I spy on my patients. Ought not a doctor to observe his patients by any means and from any stance, that he might the more fully assemble evidence? So I stand in doorways of hospital rooms and gaze. Oh, it is not all that furtive an act. Those in bed need only look up to discover me. But they never do." ( Richard Selzer , "The Discus Thrower." Confessions of a Knife . Simon & Schuster, 1979)

Open with a Riddle, Joke, or Humorous Quotation

You can use a riddle , joke, or humorous quotation to reveal something about your subject.

" Q: What did Eve say to Adam on being expelled from the Garden of Eden? A: 'I think we're in a time of transition.' The irony of this joke is not lost as we begin a new century and anxieties about social change seem rife. The implication of this message, covering the first of many periods of transition, is that change is normal; there is, in fact, no era or society in which change is not a permanent feature of the social landscape...." (Betty G. Farrell, Family: The Making of an Idea, an Institution, and a Controversy in American Culture . Westview Press, 1999)

Offer a Contrast Between Past and Present

"As a child, I was made to look out the window of a moving car and appreciate the beautiful scenery, with the result that now I don't care much for nature. I prefer parks, ones with radios going chuckawaka chuckawaka and the delicious whiff of bratwurst and cigarette smoke." (Garrison Keillor, "Walking Down The Canyon." Time , July 31, 2000)

Offer a Contrast Between Image and Reality

A compelling essay can begin with a contrast between a common misconception and the opposing truth.

"They aren’t what most people think they are. Human eyes, touted as ethereal objects by poets and novelists throughout history, are nothing more than white spheres, somewhat larger than your average marble, covered by a leather-like tissue known as sclera and filled with nature’s facsimile of Jell-O. Your beloved’s eyes may pierce your heart, but in all likelihood they closely resemble the eyes of every other person on the planet. At least I hope they do, for otherwise he or she suffers from severe myopia (near-sightedness), hyperopia (far-sightedness), or worse...." (John Gamel, "The Elegant Eye." Alaska Quarterly Review , 2009)

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- 4 Teaching Philosophy Statement Examples

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- Sample Appeal Letter for an Academic Dismissal

- 'Whack at Your Reader at Once': Eight Great Opening Lines

- What Is a Compelling Introduction?

- How to Structure an Essay

- Writing a Descriptive Essay

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- How To Write an Essay

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- Hookers vs. Chasers: How Not to Begin an Essay

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How to Develop and Organize a Classification Essay

- Contrast Composition and Rhetoric

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Start a College Essay to Hook Your Reader

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

Show me what areas I need to improve

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of the college essay introduction, tips for getting started on your essay, 6 effective techniques for starting your college essay.

- Cliche College Essay Introduction to Avoid

Where to Get Your Essay Edited for Free

Have you sat down to write your essay and just hit a wall of writer’s block? Do you have too many ideas running around your head, or maybe no ideas at all?

Starting a college essay is potentially the hardest part of the application process. Once you start, it’s easy to keep writing, but that initial hurdle is just so difficult to overcome. We’ve put together a list of tips to help you jump that wall and make your essay the best it can be.

The introduction to a college essay should immediately hook the reader. You want to give admissions officers a reason to stay interested in your story and encourage them to continue reading your essay with an open mind. Remember that admissions officers are only able to spend a couple minutes per essay, so if you bore them or turn them off from the start, they may clock out for the rest of the essay.

As a whole, the college essay should aim to portray a part of your personality that hasn’t been covered by your GPA, extracurriculars, and test scores. This makes the introduction a crucial part of the essay. Think of it as the first glimpse, an intriguing lead on, into the read rest of your essay which also showcases your voice and personality.

Brainstorm Topics

Take the time to sit down and brainstorm some good topic ideas for your essay. You want your topic to be meaningful to you, while also displaying a part of you that isn’t apparent in other aspects of your application. The essay is an opportunity to show admissions officers the “real you.” If you have a topic in mind, do not feel pressured to start with the introduction. Sometimes the best essay openings are developed last, once you fully grasp the flow of your story.

Do a Freewrite

Give yourself permission to write without judgment for an allotted period of time. For each topic you generated in your brainstorm session, do a free-write session. Set a time for one minute and write down whatever comes to mind for that specific topic. This will help get the juices flowing and push you over that initial bit of writer’s block that’s so common when it comes time to write a college essay. Repeat this exercise if you’re feeling stuck at any point during the essay writing process. Freewriting is a great way to warm up your creative writing brain whilst seeing which topics are flowing more naturally onto the page.

Create an Outline

Once you’ve chosen your topic, write an outline for your whole essay. It’s easier to organize all your thoughts, write the body, and then go back to write the introduction. That way, you already know the direction you want your essay to go because you’ve actually written it out, and you can ensure that your introduction leads directly into the rest of the essay. Admissions officers are looking for the quality of your writing alongside the content of your essay. To be prepared for college-level writing, students should understand how to logically structure an essay. By creating an outline, you are setting yourself up to be judged favorably on the quality of your writing skills.

1. The Scriptwriter

“No! Make it stop! Get me out!” My 5-year-old self waved my arms frantically in front of my face in the darkened movie theater.

Starting your essay with dialogue instantly transports the reader into the story, while also introducing your personal voice. In the rest of the essay, the author proposes a class that introduces people to insects as a type of food. Typically, one would begin directly with the course proposal. However, the author’s inclusion of this flashback weaves in a personal narrative, further displaying her true self.

Read the full essay.

2. The Shocker

A chaotic sense of sickness and filth unfolds in an overcrowded border station in McAllen, Texas. Through soundproof windows, migrants motion that they have not showered in weeks, and children wear clothes caked in mucus and tears. The humanitarian crisis at the southern border exists not only in photographs published by mainstream media, but miles from my home in South Texas.

This essay opener is also a good example of “The Vivid Imaginer.” In this case, the detailed imagery only serves to heighten the shock factor. While people may be aware of the “humanitarian crisis at the southern border,” reading about it in such stark terms is bound to capture the reader’s attention. Through this hook, the reader learns a bit about the author’s home life; an aspect of the student that may not be detailed elsewhere in their application. The rest of the essay goes on to talk about the author’s passion for aiding refugees, and this initial paragraph immediately establishes the author’s personal connection to the refugee crisis.

3. The Vivid Imaginer

The air is crisp and cool, nipping at my ears as I walk under a curtain of darkness that drapes over the sky, starless. It is a Friday night in downtown Corpus Christi, a rare moment of peace in my home city filled with the laughter of strangers and colorful lights of street vendors. But I cannot focus.

Starting off with a bit of well-written imagery transports the reader to wherever you want to take them. By putting them in this context with you, you allow the reader to closely understand your thoughts and emotions in this situation. Additionally, this method showcases the author’s individual way of looking at the world, a personal touch that is the baseline of all college essays.

Discover your chances at hundreds of schools

Our free chancing engine takes into account your history, background, test scores, and extracurricular activities to show you your real chances of admission—and how to improve them.

4. The Instant Plunger

The flickering LED lights began to form into a face of a man when I focused my eyes. The man spoke of a ruthless serial killer of the decade who had been arrested in 2004, and my parents shivered at his reaccounting of the case. I curiously tuned in, wondering who he was to speak of such crimes with concrete composure and knowledge. Later, he introduced himself as a profiler named Pyo Chang Won, and I watched the rest of the program by myself without realizing that my parents had left the couch.

Plunging readers into the middle of a story (also known as in medias res ) is an effective hook because it captures attention by placing the reader directly into the action. The descriptive imagery in the first sentence also helps to immerse the reader, creating a satisfying hook while also showing (instead of telling) how the author became interested in criminology. With this technique, it is important to “zoom out,” so to speak, in such a way that the essay remains personal to you.

5. The Philosopher

Saved in the Notes app on my phone are three questions: What can I know? What must I do? What may I hope for? First asked by Immanuel Kant, these questions guide my pursuit of knowledge and organization of critical thought, both skills that are necessary to move our country and society forward in the right direction.

Posing philosophical questions helps present you as someone with deep ideas while also guiding the focus of your essay. In a way, it presents the reader with a roadmap; they know that these questions provide the theme for the rest of the essay. The more controversial the questions, the more gripping a hook you can create.

Providing an answer to these questions is not necessarily as important as making sure that the discussions they provoke really showcase you and your own values and beliefs.

6. The Storyteller

One Christmas morning, when I was nine, I opened a snap circuit set from my grandmother. Although I had always loved math and science, I didn’t realize my passion for engineering until I spent the rest of winter break creating different circuits to power various lights, alarms, and sensors. Even after I outgrew the toy, I kept the set in my bedroom at home and knew I wanted to study engineering.

Beginning with an anecdote is a strong way to establish a meaningful connection with the content itself. It also shows that the topic you write about has been a part of your life for a significant amount of time, and something that college admissions officers look for in activities is follow-through; they want to make sure that you are truly interested in something. A personal story such as the one above shows off just that.

Cliche College Essay Introductions to Avoid

Ambiguous introduction.

It’s best to avoid introductory sentences that don’t seem to really say anything at all, such as “Science plays a large role in today’s society,” or “X has existed since the beginning of time.” Statements like these, in addition to being extremely common, don’t demonstrate anything about you, the author. Without a personal connection to you right away, it’s easy for the admissions officer to write off the essay before getting past the first sentence.

Quoting Someone Famous

While having a quotation by a famous author, celebrity, or someone else you admire may seem like a good way to allow the reader to get to know you, these kinds of introductions are actually incredibly overused. You also risk making your essay all about the quotation and the famous person who said it; admissions officers want to get to know you, your beliefs, and your values, not someone who isn’t applying to their school. There are some cases where you may actually be asked to write about a quotation, and that’s fine, but you should avoid starting your essay with someone else’s words outside of this case. It is fine, however, to start with dialogue to plunge your readers into a specific moment.

Talking About Writing an Essay

This method is also very commonplace and is thus best avoided. It’s better to show, not tell, and all this method allows you to do is tell the reader how you were feeling at the time of writing the essay. If you do feel compelled to go this way, make sure to include vivid imagery and focus on grounding the essay in the five senses, which can help elevate your introduction and separate it from the many other meta essays.

Childhood Memories

Phrases like “Ever since I was young…” or “I’ve always wanted…” also lend more to telling rather than showing. If you want to talk about your childhood or past feelings in your essay, try using one of the techniques listed earlier (such as the Instant Plunger or the Vivid Imaginer) to elevate your writing.

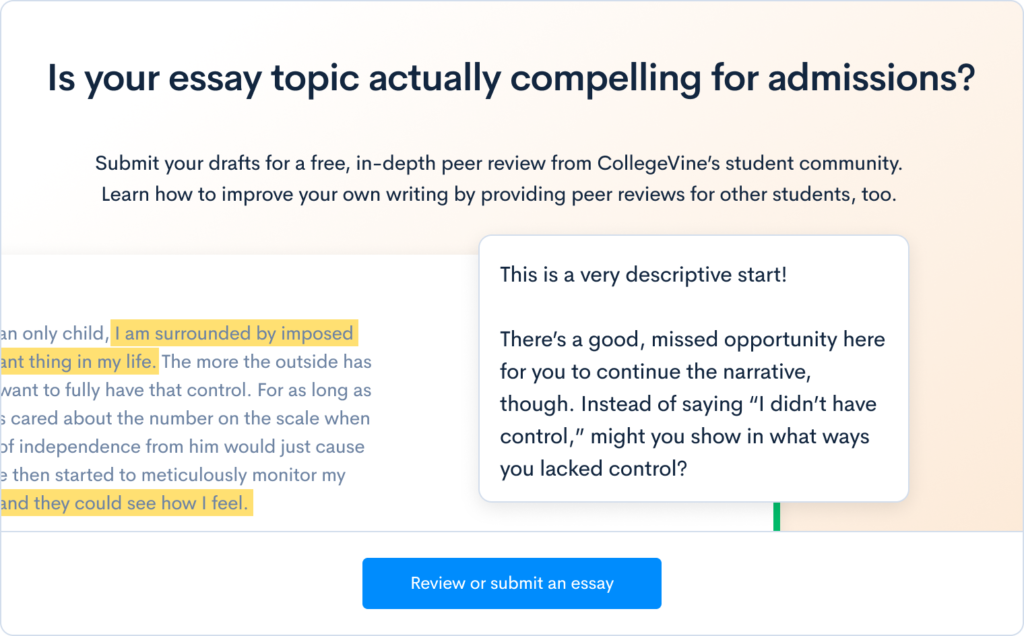

CollegeVine has a peer essay review page where peers can tell you if your introduction was enough to hook them. Getting feedback from someone who hasn’t read your essay before, and thus doesn’t have any context which may bias them to be more forgiving to your introduction, is helpful because it mimics the same environment in which an admissions officer will be reading your essay.

Writing a college essay is hard, but with these tips hopefully starting it will be a little easier!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to start a college essay perfectly.

College Essays

If you've been sitting in front of a blank screen, unsure of exactly how to start a personal statement for college, then believe me—I feel your pain. A great college essay introduction is key to making your essay stand out, so there's a lot of pressure to get it right.

Luckily, being able to craft the perfect beginning for your admissions essay is just like many other writing skills— something you can get better at with practice and by learning from examples.

In this article, I'll walk you through exactly how to start a college essay. We'll cover what makes a great personal statement introduction and how the first part of your essay should be structured. We'll also look at several great examples of essay beginnings and explain why they work, how they work, and what you can learn from them.

What Is the College Essay Introduction For?

Before we talk about how to start a college essay, let's discuss the role of the introduction. Just as your college essay is your chance to introduce yourself to the admissions office of your target college, your essay's beginning is your chance to introduce your writing.

Wait, Back Up—Why Do Colleges Want Personal Statements?

In general, college essays make it easier to get to know the parts of you not in your transcript —these include your personality, outlook on life, passions, and experiences.

You're not writing for yourself but for a very specific kind of reader. Picture it: your audience is an admissions officer who has read thousands and thousands of essays. This person is disposed to be friendly and curious, but if she hasn't already seen it all she's probably seen a good portion of it.

Your essay's job is to entertain and impress this person, and to make you memorable so you don't merely blend into the sea of other personal statements. Like all attempts at charm, you must be slightly bold and out of the ordinary—but you must also stay away from crossing the line into offensiveness or bad taste.

What Role Does the Introduction Play in a College Essay?

The personal statement introduction is basically the wriggly worm that baits the hook to catch your reader. It's vital to grab attention from the get-go—the more awake and eager your audience is, the more likely it is that what you say will really land.

How do you go about crafting an introduction that successfully hooks your reader? Let's talk about how to structure the beginning of your college essay.

How to Structure a Personal Statement Introduction

To see how the introduction fits into an essay, let's look at the big structural picture first and then zoom in.

College Essay Structure Overview

Even though they're called essays, personal statements are really more like a mix of a short story and a philosophy or psychology class that's all about you.

Usually, how this translates is that you start with a really good (and very short) story about something arresting, unusual, or important that happened to you. This is not to say that the story has to be about something important or unusual in the grand scheme of things—it just has to be a moment that stands out to you as defining in some way, or an explanation of why you are the way you are . You then pivot to an explanation of why this story is an accurate illustration of one of your core qualities, values, or beliefs.

The story typically comes in the first half of the essay, and the insightful explanation comes second —but, of course, all rules were made to be broken, and some great essays flip this more traditional order.

College Essay Introduction Components

Now, let's zero in on the first part of the college essay. What are the ingredients of a great personal statement introduction? I'll list them here and then dissect them one by one in the next section:

- A killer first sentence: This hook grabs your readers' attention and whets their appetite for your story.

- A vivid, detailed story that illustrates your eventual insight: To make up for how short your story will be, you must insert effective sensory information to immerse the reader.

- An insightful pivot toward the greater point you're making in your essay: This vital piece of the essay connects the short story part to the part where you explain what the experience has taught you about yourself, how you've matured, and how it has ultimately shaped you as a person.

How to Write a College Essay Introduction

Here's a weird secret that's true for most written work: just because it'll end up at the beginning doesn't mean you have to write it first. For example, in this case, you can't know what your killer first sentence will be until you've figured out the following details:

- The story you want to tell

- The point you want that story to make

- The trait/maturity level/background about you that your essay will reveal

So my suggestion is to work in reverse order! Writing your essay will be much easier if you can figure out the entirety of it first and then go back and work out exactly how it should start.

This means that before you can craft your ideal first sentence, the way the short story experience of your life will play out on the page, and the perfect pivoting moment that transitions from your story to your insight, you must work out a general idea about which life event you will share and what you expect that life event to demonstrate to the reader about you and the kind of person you are.

If you're having trouble coming up with a topic, check out our guide on brainstorming college essay ideas . It might also be helpful to read our guides to specific application essays, such as picking your best Common App prompt and writing a perfect University of California personal statement .

In the next sections of this article, I'll talk about how to work backwards on the introduction, moving from bigger to smaller elements: starting with the first section of the essay in general and then honing your pivot sentence and your first sentence.

How to Write the First Section of Your College Essay

In a 500-word essay, this section will take up about the first half of the essay and will mostly consist of a brief story that illuminates a key experience, an important character trait, a moment of transition or transformation, or a step toward maturity.

Once you've figured out your topic and zeroed in on the experience you want to highlight in the beginning of your essay, here are 2 great approaches to making it into a story:

- Talking it out, storyteller style (while recording yourself): Imagine that you're sitting with a group of people at a campfire, or that you're stuck on a long flight sitting next to someone you want to befriend. Now tell that story. What does someone who doesn't know you need to know in order for the story to make sense? What details do you need to provide to put them in the story with you? What background information do they need in order to understand the stakes or importance of the story?

- Record yourself telling your story to friends and then chatting about it: What do they need clarified? What questions do they have? Which parts of your story didn't make sense or follow logically for them? Do they want to know more, or less? Is part of your story interesting to them but not interesting to you? Is a piece of your story secretly boring, even though you think it's interesting?

Later, as you listen to the recorded story to try to get a sense of how to write it, you can also get a sense of the tone with which you want to tell your story. Are you being funny as you talk? Sad? Trying to shock, surprise, or astound your audience? The way you most naturally tell your story is the way you should write it.

After you've done this storyteller exercise, write down the salient points of what you learned. What is the story your essay will tell? What is the point about your life, point of view, or personality it will make? What tone will you tell it with? Sketch out a detailed outline so that you can start filling in the pieces as we work through how to write the introductory sections.

How to Write the First Sentence of Your College Essay

In general, your essay's first sentence should be either a mini-cliffhanger that sets up a situation the reader would like to see resolved, or really lush scene-setting that situates your audience in a place and time they can readily visualize. The former builds expectations and evokes curiosity, and the latter stimulates the imagination and creates a connection with the author. In both cases, you hit your goal of greater reader engagement.

Now, I'm going to show you how these principles work for all types of first sentences, whether in college essays or in famous works of fiction.

First Sentence Idea 1: Line of Quoted Direct Speech

"Mum, I'm gay." ( Ahmad Ashraf '17 for Connecticut College )

The experience of coming out is raw and emotional, and the issue of LGBTQ rights is an important facet of modern life. This three-word sentence immediately sums up an enormous background of the personal and political.

"You can handle it, Matt," said Mr. Wolf, my fourth-grade band teacher, as he lifted the heavy tuba and put it into my arms. ( Matt Coppo '07 for Hamilton College )

This sentence conjures up a funny image—we can immediately picture the larger adult standing next to a little kid holding a giant tuba. It also does a little play on words: "handle it" can refer to both the literal tuba Matt is being asked to hold and the figurative stress of playing the instrument.

First Sentence Idea 2: Punchy Short Sentence With One Grabby Detail

I live alone—I always have since elementary school. ( Kevin Zevallos '16 for Connecticut College )

This opener definitely makes us want to know more. Why was he alone? Where were the protective grown-ups who surround most kids? How on earth could a little kid of 8-10 years old survive on his own?

I have old hands. ( First line from a student in Stanford's class of 2012 )

There's nothing but questions here. What are "old" hands? Are they old-looking? Arthritic? How has having these hands affected the author?

There was no possibility of taking a walk that day. (Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre )

There's immediately a feeling of disappointment and the stifled desire for action here. Who wanted to go for a walk? And why was this person being prevented from going?

First Sentence Idea 3: Lyrical, Adjective-Rich Description of a Setting

We met for lunch at El Burrito Mexicano, a tiny Mexican lunch counter under the Red Line "El" tracks. ( Ted Mullin '06 for Carleton College )

Look at how much specificity this sentence packs in less than 20 words. Each noun and adjective is chosen for its ability to convey yet another detail. "Tiny" instead of "small" gives readers a sense of being uncomfortably close to other people and sitting at tables that don't quite have enough room for the plates. "Counter" instead of "restaurant" lets us immediately picture this work surface, the server standing behind it, and the general atmosphere. "Under the tracks" is a location deeply associated with being run down, borderline seedy, and maybe even dangerous.

Maybe it's because I live in Rhinelander, Wisconsin, where Brett Favre draws more of a crowd on Sunday than any religious service, cheese is a staple food, it's sub-zero during global warming, current "fashions" come three years after they've hit it big with the rest of the world, and where all children by the age of ten can use a 12-gauge like it's their job. ( Riley Smith '12 for Hamilton College )

This sentence manages to hit every stereotype about Wisconsin held by outsiders—football, cheese, polar winters, backwardness, and guns—and this piling on gives us a good sense of place while also creating enough hyperbole to be funny. At the same time, the sentence raises the tantalizing question: maybe what is because of Wisconsin?

High, high above the North Pole, on the first day of 1969, two professors of English Literature approached each other at a combined velocity of 1200 miles per hour. (David Lodge, Changing Places )

This sentence is structured in the highly specific style of a math problem, which makes it funny. However, at the heart of this sentence lies a mystery that grabs the reader's interest: why on earth would these two people be doing this?

First Sentence Idea 4: Counterintuitive Statement

To avoid falling into generalities with this one, make sure you're really creating an argument or debate with your counterintuitive sentence. If no one would argue with what you've said, then you aren't making an argument. ("The world is a wonderful place" and "Life is worth living" don't make the cut.)

If string theory is really true, then the entire world is made up of strings, and I cannot tie a single one. ( Joanna '18 for Johns Hopkins University )

There's a great switch here from the sub-microscopic strings that make up string theory to the actual physical strings you can tie in real life. This sentence hints that the rest of the essay will continue playing with linked, albeit not typically connected, concepts.

All children, except one, grow up. (J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan )

In just six words, this sentence upends everything we think we know about what happens to human beings.

First Sentence Idea 5: The End—Making the Rest of the Essay a Flashback

I've recently come to the realization that community service just isn't for me. ( Kyla '19 for Johns Hopkins University )

This seems pretty bold—aren't we supposed to be super into community service? Is this person about to declare herself to be totally selfish and uncaring about the less fortunate? We want to know the story that would lead someone to this kind of conclusion.

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. (Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude )

So many amazing details here. Why is the Colonel being executed? What does "discovering" ice entail? How does he go from ice-discoverer to military commander of some sort to someone condemned to capital punishment?

First Sentence Idea 6: Direct Question to the Reader

To work well, your question should be especially specific, come out of left field, or pose a surprising hypothetical.

How does an agnostic Jew living in the Diaspora connect to Israel? ( Essay #3 from Carleton College's sample essays )

This is a thorny opening, raising questions about the difference between being an ethnic Jew and practicing the religion of Judaism, and the obligations of Jews who live outside of Israel to those who live in Israel and vice versa. There's a lot of meat to this question, setting up a philosophically interesting, politically important, and personally meaningful essay.

While traveling through the daily path of life, have you ever stumbled upon a hidden pocket of the universe? ( First line from a student in Stanford's class of 2012 )

There's a dreamy and sci-fi element to this first sentence, as it tries to find the sublime ("the universe") inside the prosaic ("daily path of life").

First Sentence Idea 7: Lesson You Learned From the Story You're Telling

One way to think about how to do this kind of opening sentence well is to model it on the morals that ended each Aesop's fable . The lesson you learned should be slightly surprising (not necessarily intuitive) and something that someone else might disagree with.

Perhaps it wasn't wise to chew and swallow a handful of sand the day I was given my first sandbox, but it seemed like a good idea at the time. ( Meagan Spooner '07 for Hamilton College )

The best part of this hilarious sentence is that even in retrospect, eating a handful of sand is only possibly an unwise idea—a qualifier achieved through that great "perhaps." So does that mean it was wise in at least some way to eat the sand? The reader wants to know more.

All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. (Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina )

This immediately sets readers to mentally flip through every unhappy family they've ever known to double-check the narrator's assertion. Did he draw the right conclusion here? How did he come to this realization? The implication that he will tell us all about some dysfunctional drama also has a rubbernecking draw.

How to Write a Pivot Sentence in Your College Essay

This is the place in your essay where you go from small to big—from the life experience you describe in detail to the bigger point this experience illustrates about your world and yourself.

Typically, the pivot sentence will come at the end of your introductory section, about halfway through the essay. I say sentence, but this section could be more than one sentence (though ideally no longer than two or three).

So how do you make the turn? Usually you indicate in your pivot sentence itself that you are moving from one part of the essay to another. This is called signposting, and it's a great way to keep readers updated on where they are in the flow of the essay and your argument.

Here are three ways to do this, with real-life examples from college essays published by colleges.

Pivot Idea 1: Expand the Time Frame

In this pivot, you gesture out from the specific experience you describe to the overarching realization you had during it. Think of helper phrases such as "that was the moment I realized" and "never again would I."

Suddenly, two things simultaneously clicked. One was the lock on the door. (I actually succeeded in springing it.) The other was the realization that I'd been in this type of situation before. In fact, I'd been born into this type of situation. ( Stephen '19 for Johns Hopkins University )

This is a pretty great pivot, neatly connecting the story Stephen's been telling (about having to break into a car on a volunteering trip) and his general reliance on his own resourcefulness and ability to roll with whatever life throws at him. It's a double bonus that he accomplishes the pivot with a play on the word "click," which here means both the literal clicking of the car door latch and the figurative clicking his brain does. Note also how the pivot crystallizes the moment of epiphany through the word "suddenly," which implies instant insight.

But in that moment I realized that the self-deprecating jokes were there for a reason. When attempting to climb the mountain of comedic success, I didn't just fall and then continue on my journey, but I fell so many times that I befriended the ground and realized that the middle of the metaphorical mountain made for a better campsite. Not because I had let my failures get the best of me, but because I had learned to make the best of my failures. (Rachel Schwartzbaum '19 for Connecticut College)

This pivot similarly focuses on a "that moment" of illuminated clarity. In this case, it broadens Rachel's experience of stage fright before her standup comedy sets to the way she has more generally not allowed failures to stop her progress—and has instead been able to use them as learning experiences. Not only does she describe her humor as "self-deprecating," but she also demonstrates what she means with that great "befriended the ground" line.

It was on this first educational assignment that I realized how much could be accomplished through an animal education program—more, in some cases, than the aggregate efforts of all of the rehabilitators. I found that I had been naive in my assumption that most people knew as much about wildlife as I did, and that they shared my respect for animals. ( J.P. Maloney '07 for Hamilton College )

This is another classically constructed pivot, as J.P. segues from his negative expectations about using a rehabilitated wild owl as an educational animal to his understanding of how much this kind of education could contribute to forming future environmentalists and nature lovers. The widening of scope happens at once as we go from a highly specific "first educational assignment" to the more general realization that "much" could be accomplished through these kinds of programs.

Pivot Idea 2: Link the Described Experience With Others

In this pivot, you draw a parallel between the life event that you've been describing in your very short story and other events that were similar in some significant way. Helpful phrases include "now I see how x is really just one of the many x 's I have faced," "in a way, x is a good example of the x -like situations I see daily," and "and from then on every time I ..."

This state of discovery is something I strive for on a daily basis. My goal is to make all the ideas in my mind fit together like the gears of a Swiss watch. Whether it's learning a new concept in linear algebra, talking to someone about a programming problem, or simply zoning out while I read, there is always some part of my day that pushes me towards this place of cohesion: an idea that binds together some set of the unsolved mysteries in my mind. ( Aubrey Anderson '19 for Tufts University )

After cataloging and detailing the many interesting thoughts that flow through her brain in a specific hour, Aubrey uses the pivot to explain that this is what every waking hour is like for her "on a daily basis." She loves learning different things and finds a variety of fields fascinating. And her pivot lets us know that her example is a demonstration of how her mind works generally.

This was the first time I've been to New Mexico since he died. Our return brought so much back for me. I remembered all the times we'd visited when I was younger, certain events highlighted by the things we did: Dad haggling with the jewelry sellers, his minute examination of pots at a trading post, the affection he had for chilies. I was scared that my love for the place would be tainted by his death, diminished without him there as my guide. That fear was part of what kept my mother and me away for so long. Once there, though, I was relieved to realize that Albuquerque still brings me closer to my father. ( Essay #1 from Carleton College's sample essays )

In this pivot, one very painful experience of visiting a place filled with sorrowful memories is used as a way to think about "all the other times" the author had been to New Mexico. The previously described trip after the father's death pivots into a sense of the continuity of memory. Even though he is no longer there to "guide," the author's love for the place itself remains.

Pivot Idea 3: Extract and Underline a Trait or Value

In this type of pivot, you use the experience you've described to demonstrate its importance in developing or zooming in on one key attribute. Here are some ways to think about making this transition: "I could not have done it without characteristic y , which has helped me through many other difficult moments," or "this is how I came to appreciate the importance of value z, both in myself and in those around me."

My true reward of having Stanley is that he opened the door to the world of botany. I would never have invested so much time learning about the molecular structure or chemical balance of plants if not for taking care of him. ( Michaela '19 for Johns Hopkins University )

In this tongue-in-cheek essay in which Michaela writes about Stanley, a beloved cactus, as if "he" has human qualities and is her child, the pivot explains what makes this plant so meaningful to its owner. Without having to "take care of him," Michaela "would never have invested so much time learning" about plant biology. She has a deep affinity for the natural sciences and attributes her interest at least partly to her cactus.

By leaving me free to make mistakes and chase wild dreams, my father was always able to help ground me back in reality. Personal responsibilities, priorities and commitments are all values that are etched into my mind, just as they are within my father's. ( Olivia Rabbitt '16 for Connecticut College )

In Olivia's essay about her father's role in her life, the pivot discusses his importance by explaining his deep impact on her values. Olivia has spent the story part of her essay describing her father's background and their relationship. Now, she is free to show how without his influence, she would not be so strongly committed to "personal responsibilities, priorities and commitments."

College Essay Introduction Examples

We've collected many examples of college essays published by colleges and offered a breakdown of how several of them are put together . Now, let's check out a couple of examples of actual college essay beginnings to show you how and why they work.

Sample Intro 1

A blue seventh place athletic ribbon hangs from my mantel. Every day, as I walk into my living room, the award mockingly congratulates me as I smile. Ironically, the blue seventh place ribbon resembles the first place ribbon in color; so, if I just cover up the tip of the seven, I may convince myself that I championed the fourth heat. But, I never dare to wipe away the memory of my seventh place swim; I need that daily reminder of my imperfection. I need that seventh place.

Two years ago, I joined the no-cut swim team. That winter, my coach unexpectedly assigned me to swim the 500 freestyle. After stressing for hours about swimming 20 laps in a competition, I mounted the blocks, took my mark, and swam. Around lap 14, I looked around at the other lanes and did not see anyone. "I must be winning!" I thought to myself. However, as I finally completed my race and lifted my arms up in victory to the eager applause of the fans, I looked up at the score board. I had finished my race in last place. In fact, I left the pool two minutes after the second-to-last competitor, who now stood with her friends, wearing all her clothes.

(From "The Unathletic Department" by Meghan '17 for Johns Hopkins University )

Why Intro Sample 1 Works

Here are some of the main reasons that this essay's introduction is super effective.

#1: It's Got a Great First Sentence

The sentence is short but still does some scene setting with the descriptive "blue" and the location "from my mantel." It introduces a funny element with "seventh place"—why would that bad of a showing even get a ribbon? It dangles information just out of reach, making the reader want to know more: what was this an award for? Why does this definitively non-winning ribbon hang in such a prominent place of pride?

#2: It Has Lots of Detail

In the intro, we get physical actions: "cover up the tip," "mounted the blocks," "looked around at the other lanes," "lifted my arms up," and "stood with her friends, wearing all her clothes." We also get words conveying emotion: "mockingly congratulates me as I smile," "unexpectedly assigned," and "stressing for hours." Finally, we get descriptive specificity in the precise word choice: "from my mantel" and "my living room" instead of simply "in my house," and "lap 14" instead of "toward the end of the race."

#3: It Explains the Stakes

Even though everyone can imagine the lap pool, not everyone knows exactly what the "500 freestyle" race is. Meghan elegantly explains the difficulty by describing herself freaking out over "swimming 20 laps in a competition," which helps us to picture the swimmer going back and forth many times.

#4: It Has Great Storytelling

We basically get a sports commentary play-by-play here. Even though we already know the conclusion—Meghan came in 7th—she still builds suspense by narrating the race from her point of view as she was swimming it. She's nervous for a while, and then she starts the race.

Close to the end, she starts to think everything is going well ("I looked around at the other lanes and did not see anyone. 'I must be winning!' I thought to myself."). Everything builds to an expected moment of great triumph ("I finally completed my race and lifted my arms up in victory to the eager applause of the fans") but ends in total defeat ("I had finished my race in last place").

Not only that, but the mildly clichéd sports hype is hilariously undercut by reality ("I left the pool two minutes after the second-to-last competitor, who now stood with her friends, wearing all her clothes").

#5: It Uses a Pivot Sentence

This essay uses the time expansion method of pivoting: "But, I never dare to wipe away the memory of my seventh place swim; I need that daily reminder of my imperfection. I need that seventh place." Coming last in the race was something that happened once, but the award is now an everyday experience of humility.

The rest of the essay explores what it means for Meghan to constantly see this reminder of failure and to transform it into a sense of acceptance of her imperfections. Notice also that in this essay, the pivot comes before the main story, helping us "hear" the narrative in the way she wants us to.

Sample Intro 2

"Biogeochemical. It's a word, I promise!" There are shrieks and shouts in protest and support. Unacceptable insults are thrown, degrees and qualifications are questioned, I think even a piece of my grandmother's famously flakey parantha whizzes past my ear. Everyone is too lazy to take out a dictionary (or even their phones) to look it up, so we just hash it out. And then, I am crowned the victor, a true success in the Merchant household. But it is fleeting, as the small, glossy, plastic tiles, perfectly connected to form my winning word, are snatched out from under me and thrown in a pile with all the disgraced, "unwinning" tiles as we mix for our next game of Bananagrams. It's a similar donnybrook, this time ending with my father arguing that it is okay to use "Rambo" as a word (it totally is not).

Words and communicating have always been of tremendous importance in my life: from silly games like Bananagrams and our road-trip favorite "word game," to stunted communication between opposing grandparents, each speaking a different Indian language; from trying to understand the cheesemonger behind the counter with a deep southern drawl (I just want some Camembert!), to shaping a script to make people laugh.

Words are moving and changing; they have influence and substance.

From an Essay by Shaan Merchant ‘19 for Tufts University

Why Intro Sample 2 Works

Let's take a look at what qualities make this essay's introduction particularly memorable.

With the first sentence, we are immediately thrust into the middle of the action —into an exciting part of an argument about whether "biogeochemical" is really a word. We're also immediately challenged. Is this a word? Have I ever heard it before? Does a scientific neologism count as a word?

#2: It Shows Rather Than Tells

Since the whole essay is going to be about words, it makes sense for Shaan to demonstrate his comfort with all different kinds of language:

- Complex, elevated vocabulary, such as "biogeochemical" and "donnybrook"

- Foreign words, such as "parantha" and "Camembert"

- Colorful descriptive words, such as "shrieks and shouts," "famously flakey, "whizzes past," and "hash it out"

- "Fake" words, such as "unwinning" and "Rambo"

What's great is that Shaan is able to seamlessly mix the different tones and registers these words imply, going from cerebral to funny and back again.

#3: It Uses a Pivot Sentence

This essay uses the value-extraction style of pivot: "Words and communicating have always been of tremendous importance in my life." After we see an experience linking Shaan's clear love of his family with an interest in word games, he clarifies that this is exactly what the essay will be about—using a very straightforward pivoting sentence.

#4: It Piles On Examples to Avoid Vagueness

The danger of this kind of pivot sentence is slipping into vague, uninformative statements, such as "I love words." To avoid making a generalization the tells us nothing, the essay builds a list of examples of times when Shaan saw the way that words connect people: games ("Bananagrams and our road-trip favorite ‘word game,'"), his mixed-language family ("grandparents, each speaking a different Indian language"), encounters with strangers ("from trying to understand the cheesemonger"), and finally the more active experience of performing ("shaping a script to make people laugh").

But the essay stops short of giving so many examples that the reader drowns. I'd say three to five examples is a good range—as long as they're all different kinds of the same thing.

The Bottom Line: How to Start a College Essay

The college essay introduction should hook your reader and make her want to know more and read more.

Good personal statement introductions will contain the following features:

- A killer first line

- A detailed description of an experience from your life

- A pivot to the bigger picture, in which you explain why and how this experience has shaped you, your point of view, and/or your values.

You don't have to write the introduction first, and you certainly don't have to write your first sentence first . Instead, start by developing your story by telling it out loud to a friend. You can then work on your first sentence and your pivot.

The first sentence should either be short, punchy, and carry some ambiguity or questions, or be a detailed and beautiful description setting an easily pictured scene. The pivot, on the other hand, should answer the question, "How does the story you've told connect to a larger truth or insight about you?"

What's Next?

Wondering what to make of the Common Application essay prompts? We have the complete list of this year's Common App prompts with explanations of what each is asking as well as a guide to picking the Common App prompt that's perfect for you .

Thinking of applying to the University of California system? Check out our detailed guide on how to approach their essay prompts and craft your ideal UC essay .

If you're in the middle of the essay-writing process, you'll want to see our suggestions on what essay pitfalls to avoid .

Working on the rest of your college application? Read what admissions officers wish applicants knew before applying .

Anna scored in the 99th percentile on her SATs in high school, and went on to major in English at Princeton and to get her doctorate in English Literature at Columbia. She is passionate about improving student access to higher education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

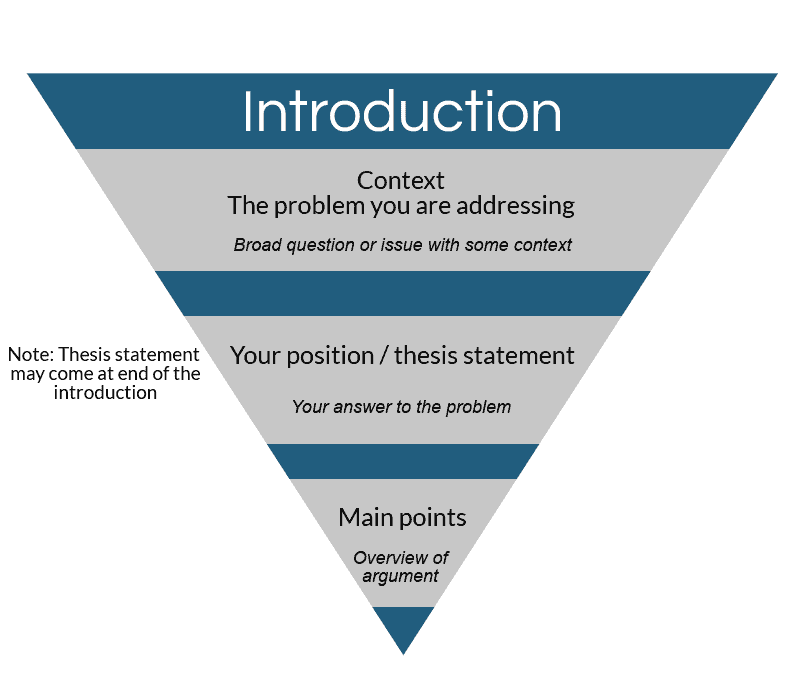

The writer of the academic essay aims to persuade readers of an idea based on evidence. The beginning of the essay is a crucial first step in this process. In order to engage readers and establish your authority, the beginning of your essay has to accomplish certain business. Your beginning should introduce the essay, focus it, and orient readers.

Introduce the Essay. The beginning lets your readers know what the essay is about, the topic . The essay's topic does not exist in a vacuum, however; part of letting readers know what your essay is about means establishing the essay's context , the frame within which you will approach your topic. For instance, in an essay about the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech, the context may be a particular legal theory about the speech right; it may be historical information concerning the writing of the amendment; it may be a contemporary dispute over flag burning; or it may be a question raised by the text itself. The point here is that, in establishing the essay's context, you are also limiting your topic. That is, you are framing an approach to your topic that necessarily eliminates other approaches. Thus, when you determine your context, you simultaneously narrow your topic and take a big step toward focusing your essay. Here's an example.

| was published in 1899, critics condemned the book as immoral. One typical critic, writing in the , feared that the novel might "fall into the hands of youth, leading them to dwell on things that only matured persons can understand, and promoting unholy imaginations and unclean desires" (150). A reviewer in the wrote that "there is much that is very improper in it, not to say positively unseemly." |

The paragraph goes on. But as you can see, Chopin's novel (the topic) is introduced in the context of the critical and moral controversy its publication engendered.

Focus the Essay. Beyond introducing your topic, your beginning must also let readers know what the central issue is. What question or problem will you be thinking about? You can pose a question that will lead to your idea (in which case, your idea will be the answer to your question), or you can make a thesis statement. Or you can do both: you can ask a question and immediately suggest the answer that your essay will argue. Here's an example from an essay about Memorial Hall.

The fullness of your idea will not emerge until your conclusion, but your beginning must clearly indicate the direction your idea will take, must set your essay on that road. And whether you focus your essay by posing a question, stating a thesis, or combining these approaches, by the end of your beginning, readers should know what you're writing about, and why —and why they might want to read on.

Orient Readers. Orienting readers, locating them in your discussion, means providing information and explanations wherever necessary for your readers' understanding. Orienting is important throughout your essay, but it is crucial in the beginning. Readers who don't have the information they need to follow your discussion will get lost and quit reading. (Your teachers, of course, will trudge on.) Supplying the necessary information to orient your readers may be as simple as answering the journalist's questions of who, what, where, when, how, and why. It may mean providing a brief overview of events or a summary of the text you'll be analyzing. If the source text is brief, such as the First Amendment, you might just quote it. If the text is well known, your summary, for most audiences, won't need to be more than an identifying phrase or two:

| , Shakespeare's tragedy of `star-crossed lovers' destroyed by the blood feud between their two families, the minor characters . . . |

Often, however, you will want to summarize your source more fully so that readers can follow your analysis of it.

Questions of Length and Order. How long should the beginning be? The length should be proportionate to the length and complexity of the whole essay. For instance, if you're writing a five-page essay analyzing a single text, your beginning should be brief, no more than one or two paragraphs. On the other hand, it may take a couple of pages to set up a ten-page essay.

Does the business of the beginning have to be addressed in a particular order? No, but the order should be logical. Usually, for instance, the question or statement that focuses the essay comes at the end of the beginning, where it serves as the jumping-off point for the middle, or main body, of the essay. Topic and context are often intertwined, but the context may be established before the particular topic is introduced. In other words, the order in which you accomplish the business of the beginning is flexible and should be determined by your purpose.

Opening Strategies. There is still the further question of how to start. What makes a good opening? You can start with specific facts and information, a keynote quotation, a question, an anecdote, or an image. But whatever sort of opening you choose, it should be directly related to your focus. A snappy quotation that doesn't help establish the context for your essay or that later plays no part in your thinking will only mislead readers and blur your focus. Be as direct and specific as you can be. This means you should avoid two types of openings:

- The history-of-the-world (or long-distance) opening, which aims to establish a context for the essay by getting a long running start: "Ever since the dawn of civilized life, societies have struggled to reconcile the need for change with the need for order." What are we talking about here, political revolution or a new brand of soft drink? Get to it.

- The funnel opening (a variation on the same theme), which starts with something broad and general and "funnels" its way down to a specific topic. If your essay is an argument about state-mandated prayer in public schools, don't start by generalizing about religion; start with the specific topic at hand.

Remember. After working your way through the whole draft, testing your thinking against the evidence, perhaps changing direction or modifying the idea you started with, go back to your beginning and make sure it still provides a clear focus for the essay. Then clarify and sharpen your focus as needed. Clear, direct beginnings rarely present themselves ready-made; they must be written, and rewritten, into the sort of sharp-eyed clarity that engages readers and establishes your authority.

Copyright 1999, Patricia Kain, for the Writing Center at Harvard University

How to Start an Essay with Strong Hooks and Leads

ALWAYS START AN ESSAY WITH AN ENGAGING INTRODUCTION

Getting started is often the most challenging part of writing an essay, and it’s one of the main reasons our students are prone to leaving their writing tasks to the last minute.

But what if we could give our students some tried and tested tips and strategies to show them how to start an essay?

What if we could give them various strategies they could pull out of their writer’s toolbox and kickstart their essays at any time?

In this article, we’ll look at tried and tested methods and how to start essay examples to get your students’ writing rolling with momentum to take them to their essays’ conclusion.

Once you have worked past the start of your essay, please explore our complete guide to polishing an essay before submitting it and our top 5 tips for essay writing.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF AN ESSAY’S INTRODUCTION?

Essentially, the purpose of the introduction is to achieve two things:

1. To orientate the reader

2. To motivate the reader to keep reading.

An effective introduction will give the reader a clear idea of what the essay will be about. To do this, it may need to provide some necessary background information or exposition.

Once this is achieved, the writer will then make a thesis statement that informs the reader of the main ‘thrust’ of the essay’s position, the supporting arguments of which will be explored throughout the body paragraphs of the remainder of the essay.

When considering how to start an essay, ensure you have a strong thesis statement and support it through well-crafted arguments in the body paragraphs . These are complex skills in their own right and beyond the scope of this guide, but you can find more detail on these aspects of essay writing in other articles on this site that go beyond how to start an essay.

For now, our primary focus is on how to grab the reader’s attention right from the get-go.

After all, the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step or, in this case, a single opening sentence.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON WRITING HOOKS, LEADS & INTRODUCTIONS

Teach your students to write STRONG LEADS, ENGAGING HOOKS and MAGNETIC INTRODUCTIONS for ALL TEXT TYPES with this engaging PARAGRAPH WRITING UNIT designed to take students from zero to hero over FIVE STRATEGIC LESSONS.

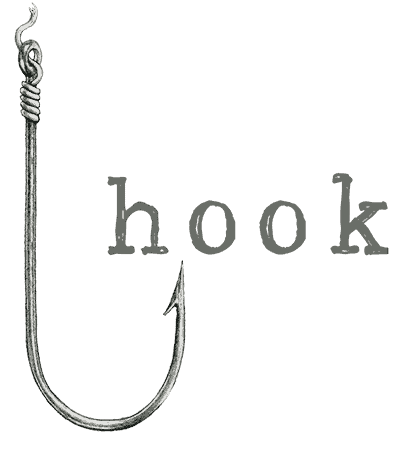

WHAT IS A “HOOK” IN ESSAY WRITING?

A hook is a sentence or phrase that begins your essay, grabbing the reader’s attention and making them want to keep reading. It is the first thing the reader will see, and it should be interesting and engaging enough to make them want to read more.

As you will learn from the how to start an essay examples below, a hook can be a quote, a question, a surprising fact, a personal story, or a bold statement. It should be relevant to the topic of your essay and should be able to create a sense of curiosity or intrigue in the reader. The goal of a hook is to make the reader want to read on and to draw them into the central argument or point of your essay.

Some famous examples of hooks in literature you may have encountered are as follows.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen” George Orwell in 1984

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife” – Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen in Pride and Prejudice

HOW TO HOOK THE READER WITH ATTENTION-GRABBING OPENING SENTENCES

We all know that every essay has a beginning, a middle , and an end . But, if our students don’t learn to grab the reader’s attention from the opening sentence, they’ll struggle to keep their readers engaged long enough to make it through the middle to the final full stop. Take a look at these five attention-grabbing sentence examples.

- “The secret to success is hidden in a single, elusive word: persistence.”

- “Imagine a world without electricity, where the only source of light is the flame of a candle.”

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, but most importantly, it was the time that changed everything.”

- “They said it couldn’t be done, but she proved them wrong with her grit and determination.”

- “He stood at the edge of the cliff, staring down at the tumultuous ocean below, knowing that one misstep could mean certain death.”

Regardless of what happens next, those sentences would make any reader stop whatever else they might focus on and read with more intent than before. They have provided the audience with a “hook” intended to lure us further into their work.

To become effective essay writers, your students need to build the skill of writing attention-grabbing opening sentences. The best way of achieving this is to use ‘hooks’.

There are several kinds of hooks that students can choose from. In this article, we’ll take a look at some of the most effective of these:

1. The Attention-Grabbing Anecdote

2. The Bold Pronouncement!

3. The Engaging Fact

4. Using an Interesting Quote

5. Posing a Rhetorical Question

6. Presenting a Contrast

How appropriate each of these hooks is will depend on the essay’s nature. Students must consider the topic, purpose, tone, and audience of the essay they’re writing before deciding how best to open it.

Let’s look at each of these essay hooks, along with a practice activity students can undertake to put their knowledge of each hook into action.

1: HOW TO START AN ESSAY WITH “THE ATTENTION-GRABBING ANECDOTE”

Anecdotes are an effective way for the student to engage the reader’s attention right from the start.

When the anecdote is based on the writer’s personal life, they are a great way to create intimacy between the writer and the reader from the outset.

Anecdotes are an especially useful starting point when the essay explores more abstract themes as they climb down the ladder of abstraction and fit the broader theme of the essay to the shape of the writer’s life.

Anecdotes work because they are personal, and because they’re personal, they infuse the underlying theme of the essay with emotion.

This expression of emotion helps the writer form a bond with the reader. And it is this bond that helps encourage the reader to continue reading.

Readers find this an engaging approach, mainly when the topic is complex and challenging.

Anecdotes provide an ‘in’ to the writing’s broader theme and encourage the reader to read on.

Examples of Attention-grabbing anecdotes

- “It was my first day of high school, and I was a bundle of nerves. I had always been a shy kid, and the thought of walking into a new school, surrounded by strangers was overwhelming. But as I walked through the front doors, something unexpected happened. A senior, who I had never met before, came up to me and said ‘Welcome to high school; it’s going to be an amazing four years.’ That one small act of kindness from a complete stranger made all the difference, and from that day on, I knew that I would be okay.”

- “I was in my math class and having a tough day. I had a test coming up, and I was struggling to understand the material. My teacher, who I had always thought was strict and unapproachable, noticed that I was struggling and asked if I needed help. I was surprised, but I took her up on her offer, and she spent extra time with me after class, helping me to understand the material. That experience taught me that sometimes, the people we think we know the least about are the ones who can help us the most.”

- “It was the last day of 8th grade, and we were all sitting in the auditorium, waiting for the ceremony to begin. Suddenly, the principal got on stage and announced that there was a surprise guest speaker. I was confused and curious, but when the guest walked out on stage, I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was my favorite rapper who had come to speak to us about the importance of education. That moment was a turning point for me, it showed me that if you work hard and believe in yourself, anything is possible.”

Attention-Grabbing Anecdote Teaching Strategies

One way to help students access their personal stories is through sentence starters, writing prompts, or well-known stories and their themes.

First, instruct students to choose a theme to write about. For example, if we look at the theme of The Boy Who Cried Wolf, something like: we shouldn’t tell lies, or people may not believe us when we tell the truth.

Fairytales and fables are great places for students to find simple themes or moral lessons to explore for this activity.

Once they’ve chosen a theme, encourage the students to recall a time when this theme was at play in their own lives. In the case above, a time when they paid the cost, whether seriously or humorously, for not telling the truth.

This memory will form the basis for a personal anecdote that will form a ‘hook’. Students can practice replicating this process for various essay topics.

It’s essential when writing anecdotes that students attempt to capture their personal voice.

One way to help them achieve this is to instruct them to write as if they were orally telling their story to a friend.

This ‘vocal’ style of writing helps to create intimacy between writer and reader, which is the hallmark of this type of opening.

2: HOW TO START AN ESSAY WITH “THE BOLD PRONOUNCEMENT”

As the old cliché “Go big or go home!” would have it, making a bold pronouncement at the start of an essay is one surefire way to catch the reader’s attention.

Bold statements exude confidence and assure the reader that this writer has something to say that’s worth hearing. A bold statement placed right at the beginning suggests the writer isn’t going to hedge their bets or perch passively on a fence throughout their essay.

The bold pronouncement technique isn’t only useful for writing a compelling opening sentence, the formula can be used to generate a dramatic title for the essay.

For example, the recent New York Times bestseller ‘Everybody Lies’ by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz is an excellent example of the bold pronouncement in action.

Examples of Bold Pronouncements

- “I will not be just a statistic, I will be the exception. I will not let my age or my background define my future, I will define it myself.”

- “I will not be afraid to speak up and make my voice heard. I will not let anyone silence me or make me feel small. I will stand up for what I believe in and I will make a difference.”

- “I will not be satisfied with just getting by. I will strive for greatness and I will not be content with mediocrity. I will push myself to be the best version of me, and I will not settle for anything less.”

Strategies for Teaching how to write a Bold Pronouncement

Give the students a list of familiar tales; again, Aesop’s Fables make for a good resource.

In groups, have them identify some tales’ underlying themes or morals. For this activity, these can take the place of an essay’s thesis statement.

Then, ask the students to discuss in their groups and collaborate to write a bold pronouncement based on the story. Their pronouncement should be short, pithy, and, most importantly, as bold as bold can be.

3: HOW TO START AN ESSAY WITH “THE ENGAGING FACT”

In our cynical age of ‘ fake news ’, opening an essay with a fact or statistic is a great way for students to give authority to their writing from the very beginning.

Students should choose the statistic or fact carefully, it should be related to their general thesis, and it needs to be noteworthy enough to spark the reader’s curiosity.

This is best accomplished by selecting an unusual or surprising fact or statistic to begin the essay with.

Examples of the Engaging Fact

- “Did you know that the average teenager spends around 9 hours a day consuming media? That’s more than the time they spend sleeping or in school!”

- “The brain continues to develop until the age of 25, which means that as a teenager, my brain is still going through major changes and growth. This means I have a lot of potential to learn and grow.”

- “The average attention span of a teenager is shorter than that of an adult, meaning that it’s harder for me to focus on one task for an extended time. This is why it is important for me to balance different activities and take regular breaks to keep my mind fresh.”

Strategies for teaching how to write engaging facts

This technique can work well as an extension of the bold pronouncement activity above.

When students have identified each of the fables’ underlying themes, have them do some internet research to identify related facts and statistics.

Students highlight the most interesting of these and consider how they would use them as a hook in writing an essay on the topic.

4: HOW TO START AN ESSAY USING “AN INTERESTING QUOTATION”

This strategy is as straightforward as it sounds. The student begins their essay by quoting an authority or a well-known figure on the essay’s topic or related topic.

This quote provides a springboard into the essay’s subject while ensuring the reader is engaged.

The quotation selected doesn’t have to align with the student’s thesis statement.

In fact, opening with a quotation the student disagrees with can be a great way to generate a debate that grasps the reader’s attention from the outset.

Examples of starting an essay with an interesting quotation.