Four Optimization Meta-heuristic Approaches in Evaluating Groundwater Quality (Case study: Shiraz Plain)

- Research Paper

- Published: 20 June 2024

Cite this article

- Hossein Moayedi 1 , 2 ,

- Marjan Salari 3 ,

- T. N. G. Nguyen 4 &

- Atefeh Ahmadi Dehrashid 5

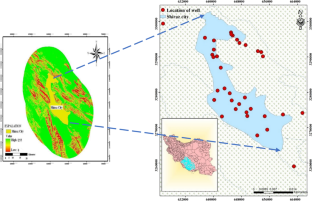

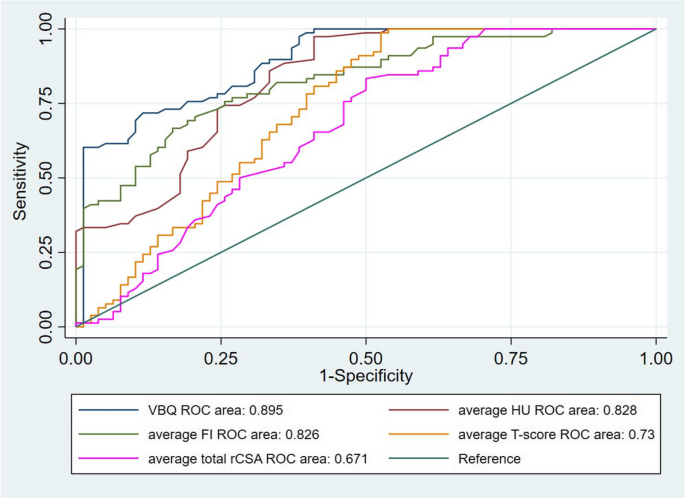

Estimating and predicting groundwater quality characteristics so that managers may make management decisions is one of the critical goals of water resource planners and managers. The complexity of groundwater networks makes it difficult to predict either the time or the location of groundwater. Many models have been created in this area, offering better management to preserve water quality. Most of these models call for input parameters that are either seldom accessible or expensively and laboriously measured. A better option among them is the Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Model, which draws inspiration from the human brain. This study uses Na + , Mg2 + , Ca2 + , Na%, K + , SO42 − , Cl − , pH, and HCO3 − quality parameters to estimate the Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR). The Shiraz Plain's groundwater quality was simulated using four optimization meta-heuristic methods, including biography-based optimization (BBO), black hole attack (BHA), sequential forward selection (SFS), and multi-verse optimization (MVO). These methods excel in adaptability, convergence speed, feature selection, diversity of solutions, and robustness to complex and noisy datasets, ultimately leading to more accurate and efficient predictive models than earlier methods. A statistical period of 16 years (2002–2018) was used to collect the groundwater quality data for the Shiraz plain to accomplish this purpose. The findings showed that the SFS-MLP approach was more accurate than the other methods with training and testing dataset values of R 2 = 0.9996 and 0.99923, RMSE = 0.04929 and 0.072, and MAE = 0.039357 and 0.048968, respectively. Additionally, the findings demonstrated that the SFS-MLP approach has a high capacity and accuracy for predicting and modeling groundwater quality. This study's findings also show that intelligence models and optimization algorithms may be used to mimic groundwater quality parameters effectively.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data Availability

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Adimalla N, Chen J, Qian H (2020) Spatial characteristics of heavy metal contamination and potential human health risk assessment of urban soils: a case study from an urban region of South India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 194:110406

Article Google Scholar

Ahmadi Dehrashid A, Dong H, Fatahizadeh M, Gholizadeh Touchaei H, Gör M, Moayedi H, Salari M, Thi QT (2024) A new procedure for optimizing neural network using stochastic algorithms in predicting and assessing landslide risk in East Azerbaijan. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-024-02690-7

Alfarrah N, Walraevens K (2018) Groundwater overexploitation and seawater intrusion in coastal areas of arid and semi-arid regions. Water 10(2):143

Al-Shurman M, Yoo SM, Park S (2004) Black hole attack in mobile ad hoc networks. Proceedings of the 42nd annual Southeast regional conference.

Badeenezhad A, Tabatabaee HR, Nikbakht H-A, Radfard M, Abbasnia A, Baghapour MA, Alhamd M (2020) Estimation of the groundwater quality index and investigation of the affecting factors their changes in Shiraz drinking groundwater. Iran Groundwater Sustain Develop 11:100435

Barbieri M, Ricolfi L, Vitale S, Muteto PV, Nigro A, Sappa G (2019) Assessment of groundwater quality in the buffer zone of limpopo national park, gaza province, southern Mozambique. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:62–77

Cherkaoui B, Beni-hssane A, Erritali M (2020) Variable control chart for detecting black hole attack in vehicular ad-hoc networks. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 11:5129–5138

Coulibaly P, Anctil F, Bobée B (1999) Prévision hydrologique par réseaux de neurones artificiels: état de l’art. Can J Civ Eng 26(3):293–304

Dai W (2021) Safety evaluation of traffic system with historical data based on Markov process and deep-reinforcement learning. J Comput Method Eng Appl 1(1):1–14

Google Scholar

Dai H, Ju J, Gui D, Zhu Y, Ye M, Cui J, Hu BX (2024a) A two-step Bayesian network-based process sensitivity analysis for complex nitrogen reactive transport modeling. J Hydrology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.130903

Dai H, Liu Y, Guadagnini A, Yuan S, Yang J, Ye M (2024b) Comparative assessment of two global sensitivity approaches considering model and parameter uncertainty. Water Resour Res 60(2):e2023WR0360976

Dai W (2022) Evaluation and improvement of carrying capacity of a traffic system. Innov Appl Eng Technol https://doi.org/10.58195/iaet.v1i1.001

Dai W (2023) Design of traffic improvement plan for line 1 Baijiahu station of Nanjing metro. Innov Appl Eng Technol https://doi.org/10.58195/iaet.v2i1.133

Deng H, Li W, Agrawal DP (2002) Routing security in wireless ad hoc networks. IEEE Commun Mag 40(10):70–75

El Bilali A, Taleb A (2020) Prediction of irrigation water quality parameters using machine learning models in a semi-arid environment. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci 19(7):439–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2020.08.001

El Bilali A, Taleb A, Brouziyne Y (2021a) Groundwater quality forecasting using machine learning algorithms for irrigation purposes. Agric Water Manage 245:106625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106625

El Bilali A, Taleb A, Nafii A, Alabjah B, Mazigh N (2021b) Prediction of sodium adsorption ratio and chloride concentration in a coastal aquifer under seawater intrusion using machine learning models. Environ Technol Innov 23:101641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101641

Fu Y, Zhou M, Guo X, Qi L (2019) Artificial-molecule-based chemical reaction optimization for flow shop scheduling problem with deteriorating and learning effects. Ieee Access 7:53429–53440

Haggerty R, Sun J, Yu H, Li Y (2023) Application of machine learning in groundwater quality modeling-A comprehensive review. Water Res 233:119745

Ibrahim H, Yaseen ZM, Scholz M, Ali M, Gad M, Elsayed S, Khadr M, Hussein H, Ibrahim HH, Eid MH (2023) Evaluation and prediction of groundwater quality for irrigation using an integrated water quality indices, machine learning models and GIS approaches: a representative case study. Water 15(4):694

Jha MK, Shekhar A, Jenifer MA (2020) Assessing groundwater quality for drinking water supply using hybrid fuzzy-GIS-based water quality index. Water Res 179:115867

Jia B, Zhou G (2023) (2023) Estimation of global karst carbon sink from 1950s to 2050s using response surface methodology. Geo-Spatial Inform Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/10095020.2023.2165974

Joseph VR (2022) Optimal ratio for data splitting. Stat Anal Data Mining: ASA Data Sci J 15(4):531–538

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Kang Q, Feng S, Zhou M, Ammari AC, Sedraoui K (2017) Optimal load scheduling of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles via weight-aggregation multi-objective evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst 18(9):2557–2568

Khan N, Malik A, Nehra K (2021) Groundwater hydro-geochemistry, quality, microbiology and human health risk assessment in semi-arid area of Rajasthan, India: a chemometric approach. Environ Monit Assess 193:1–36

Khashei-Siuki A, Kouchkzadeh M, Ghahraman B (2011) Predicting dryland wheat yield from meteorological data using expert system, Khorasan Province. Iran J Agric Sci Technol 13(4):627–640

Kong C, Li H, Zhang L, Zhu H, Liu T (2019) Link prediction on dynamic heterogeneous information networks. International Conference on Computational Data and Social Networks.

Kong C, Li H, Zhu H, Xiu Y, Liu J, Liu T (2019). Anonymized user linkage under differential privacy. Soft Computing in Data Science: 5th International Conference, SCDS 2019, Iizuka, Japan, August 28–29, 2019, Proceedings 5.

Kong C, Liu J, Li H, Liu Y, Zhu H, Liu T (2019) Drug abuse detection via broad learning. Web Information Systems and Applications: 16th International Conference, WISA 2019, Qingdao, China, September 20–22, 2019, Proceedings 16,

Kong C, Zhu H, Li H, Liu J, Wang Z, Qian Y (2019) Multi-agent negotiation in real-time bidding. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-TW).

Kumar S, Bharti V, Singh K, Singh T (2010) Quality assessment of potable water in the town of Kolasib, Mizoram (India). Environ Earth Sci 61:115–121

Kumar R, Singh S, Kumar R, Sharma P (2022) Groundwater quality characterization for safe drinking water supply in sheikhpura district of Bihar, India: a geospatial approach. Front Water 4:848018

Li J, Pang Z, Liu Y, Hu S, Jiang W, Tian L, Yang G, Jiang Y, Jiao X, Tian J (2023) Changes in groundwater dynamics and geochemical evolution induced by drainage reorganization: evidence from 81Kr and 36Cl dating of geothermal water in the Weihe Basin of China. Earth Planet Sci Lett 623:118425

Ma H (2010) An analysis of the equilibrium of migration models for biogeography-based optimization. Inf Sci 180(18):3444–3464

MacArthur RH, Wilson EO (2001) The theory of island biogeography (Vol. 1). Princeton university press.

Masoudi R, Mousavi SR, Rahimabadi PD, Panahi M, Rahmani A (2023) Assessing data mining algorithms to predict the quality of groundwater resources for determining irrigation hazard. Environ Monit Assess 195(2):319

Meng X, Li J, Zhou M, Dai X, Dou J (2016) Population-based incremental learning algorithm for a serial colored traveling salesman problem. IEEE Trans Syst, Man, Cyber: Syst 48(2):277–288

Mirjalili S, Mirjalili SM, Hatamlou A (2016) Multi-verse optimizer: a nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural Comput Appl 27(2):495–513

Mishra A, Nadkarni K, Patcha A (2004) Intrusion detection in wireless ad hoc networks. IEEE Wirel Commun 11(1):48–60

Moayedi H, Dehrashid AA (2023) A new combined approach of neural-metaheuristic algorithms for predicting and appraisal of landslide susceptibility mapping. Environ Sci Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-28133-4

Moayedi H, Canatalay PJ, Ahmadi Dehrashid A, Cifci MA, Salari M, Le BN (2023a) Multilayer perceptron and their comparison with two nature-inspired hybrid techniques of biogeography-based optimization (BBO) and backtracking search algorithm (BSA) for assessment of landslide susceptibility. Land 12(1):242

Moayedi H, Salari M, Dehrashid AA, Le BN (2023b) Groundwater quality evaluation using hybrid model of the multi-layer perceptron combined with neural-evolutionary regression techniques: case study of Shiraz plain. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-023-02429-w

Mohammed MA, Kaya F, Mohamed A, Alarifi SS, Abdelrady A, Keshavarzi A, Szabó NP, Szűcs P (2023) Application of GIS-based machine learning algorithms for prediction of irrigational groundwater quality indices. Front Earth Sci 11:1274142

Naghibi SA, Khodaei B, Hashemi H (2022) An integrated InSAR-machine learning approach for ground deformation rate modeling in arid areas. J Hydrol 608:127627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2022.127627

Organization WH (2006) The Guidelines: a framework for safe drinking water. Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality. 3rd ed. Geneva; WHO, 22–36.

Qiu Y, Wang J (2024). A machine learning approach to credit card customer segmentation for economic stability. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Economic Management and Big Data Applications, ICEMBDA 2023, October 27–29, 2023, Tianjin, China.

Qiu Y (2019) Estimation of tail risk measures in finance: approaches to extreme value mixture modeling Johns Hopkins university.

Rácz A, Bajusz D, Héberger K (2021) Effect of dataset size and train/test split ratios in QSAR/QSPR multiclass classification. Molecules 26(4):1111

Raschka S, Mirjalili V (2017). Python machine learning: Machine learning and deep learning with python. Scikit-Learn, and TensorFlow. Second edition ed, 3.

Raschka S, Mirjalili V (2019). Python machine learning: Machine learning and deep learning with python, scikit-learn, and TensorFlow 2. Packt Publishing Ltd.

Salami E, Salari M, Ehteshami M, Bidokhti N, Ghadimi H (2016) Application of artificial neural networks and mathematical modeling for the prediction of water quality variables (case study: southwest of Iran). Desalin Water Treat 57(56):27073–27084

Salari M, Rakhshandehroo G, Ehetshami M (2017) Investigating the spatial variability of some important groundwater quality factors based on the geostatistical simulation (case study: Shiraz plain). Desalin Water Treat 65:163–174

Salari M, Shahid ES, Afzali SH, Ehteshami M, Conti GO, Derakhshan Z, Sheibani SN (2018) Quality assessment and artificial neural networks modeling for characterization of chemical and physical parameters of potable water. Food Chem Toxicol 118:212–219

Shafiee S, Lied LM, Burud I, Dieseth JA, Alsheikh M, Lillemo M (2021) Sequential forward selection and support vector regression in comparison to LASSO regression for spring wheat yield prediction based on UAV imagery. Comput Electron Agric 183:106036

Shahida ES, Salarib M, Rastegarc M, Nikbakht S, Sheibania ME (2021) Artificial neural network and mathematical approach for estimation of surface water quality parameters (case study: California, USA). Sat 100:2

Sharma, Y., Mukherjee, A., Srivastava, J., Mahato, M., & Singh, T. (2008). Prediction of various parameters of a river for assessment of water quality by an intelligent technique. Chemical Product and Process Modeling , 3 (1).

Simon D (2008) Biogeography-based optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 12(6):702–713

Singh G, Rishi MS, Herojeet R, Kaur L, Sharma K (2020) Evaluation of groundwater quality and human health risks from fluoride and nitrate in semi-arid region of northern India. Environ Geochem Health 42:1833–1862

Singha S, Pasupuleti S, Singha SS, Singh R, Kumar S (2021) Prediction of groundwater quality using efficient machine learning technique. Chemosphere 276:130265

Song N, Qian L, Li X (2005) Wormhole attacks detection in wireless ad hoc networks: A statistical analysis approach. 19th IEEE international parallel and distributed processing symposium.

Sun B, Guan Y, Chen J, Pooch UW (2003) Detecting black-hole attack in mobile ad hoc networks.

Tian G, Hao N, Zhou M, Pedrycz W, Zhang C, Ma F, Li Z (2019) Fuzzy grey choquet integral for evaluation of multicriteria decision making problems with interactive and qualitative indices. IEEE Trans Syst, Man, Cyber: Syst 51(3):1855–1868

Tung TM, Yaseen ZM (2020) A survey on river water quality modelling using artificial intelligence models: 2000–2020. J Hydrol 585:124670

Verma A, Singh T (2013) Prediction of water quality from simple field parameters. Environ Earth Sci 69:821–829

Wang XP, Huang YS (2008) Predicting risks of capital flow using artificial neural network and levenberg marquardt algorithm. 2008 International Conference on Machine Learning and Cybernetics.

Wenjun D, Fatahizadeh M, Touchaei HG, Moayedi H, Foong LK (2023) Application of six neural network-based solutions on bearing capacity of shallow footing on double-layer soils. Steel Compos Struct 49(2):231–244

Xing K, Han L, Zhou M, Wang F (2011) Deadlock-free genetic scheduling algorithm for automated manufacturing systems based on deadlock control policy. IEEE Trans Syst, Man, Cyber, Part B Cyber 42(3):603–615

Zhang K, Li Y, Yu Z, Yang T, Xu J, Chao L, Ni J, Wang L, Gao Y, Hu Y (2022) Xin’anjiang nested experimental watershed (XAJ-NEW) for understanding multiscale water cycle: scientific objectives and experimental design. Engineering 18:207–217

Zhao J, Liu S, Zhou M, Guo X, Qi L (2018) Modified cuckoo search algorithm to solve economic power dispatch optimization problems. IEEE/CAA J Auto Sinica 5(4):794–806

Zhao Z, Liu S, Zhou M, Guo X, Qi L (2019) Decomposition method for new single-machine scheduling problems from steel production systems. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng 17(3):1376–1387

Zhao Y, Dai W, Wang Z, Ragab AE (2024) Application of computer simulation to model transient vibration responses of GPLs reinforced doubly curved concrete panel under instantaneous heating. Mater Today Commun 38:107949

Zheng Y-J, Ling H-F, Xue J-Y (2014) Disaster rescue task scheduling: An evolutionary multiobjective optimization approach. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput 6(2):288–300

Zhou G, Wang Z, Li Q (2022) Spatial negative co-location pattern directional mining algorithm with join-based prevalence. Remote Sens 14(9):2103

Zhou G, Su S, Xu J, Tian Z, Cao Q (2023) Bathymetry retrieval from spaceborne multispectral subsurface reflectance. IEEE J Select Topics Appl Earth Observ Remote Sens 16:2547–2558

Zhu H, Wang B (2021). Negative siamese network for classifying semantically similar sentences. 2021 International Conference on Asian Language Processing (IALP).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants, without whom this study would be impossible.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Research and Development, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, 550000, Vietnam

Hossein Moayedi

School of Engineering and Technology, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam

Department of Civil Engineering, Sirjan University of Technology, Sirjan, Iran

Marjan Salari

School of Engineering & Technology, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam

T. N. G. Nguyen

Department of Climatology Faculty of Natural Resources, , University of Kurdistan, Sanandaj, Iran

Atefeh Ahmadi Dehrashid

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Hossein Moayedi; Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft preparation; Marjan Salari: Investigation, visualization, writing-original draft preparation, TNG Nguyen; Visualization, Formal analysis, Atefeh Ahmadi Dehrashid; Writing-review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marjan Salari .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Moayedi, H., Salari, M., Nguyen, T.N.G. et al. Four Optimization Meta-heuristic Approaches in Evaluating Groundwater Quality (Case study: Shiraz Plain). Iran J Sci Technol Trans Civ Eng (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01501-x

Download citation

Received : 07 December 2023

Accepted : 31 May 2024

Published : 20 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01501-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Groundwater

- Artificial neural network

- Sodium adsorption ratio

- Swarm-based approach

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 19.6.2024 in Vol 12 (2024)

Effect of Implementing an Informatization Case Management Model on the Management of Chronic Respiratory Diseases in a General Hospital: Retrospective Controlled Study

Authors of this article:

- Yi-Zhen Xiao 1 , MBBS ;

- Xiao-Jia Chen 1 , MBBS ;

- Xiao-Ling Sun 1 , MBBS ;

- Huan Chen 1 , MM ;

- Yu-Xia Luo 1 , MBBS ;

- Yuan Chen 1 , MBBS ;

- Ye-Mei Liang 2 , MM

1 Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Yulin First People’s Hospital, , Yulin, , China

2 Department of Nursing, Yulin First People’s Hospital, , Yulin, , China

Corresponding Author:

Ye-Mei Liang, MM

Background: The use of chronic disease information systems in hospitals and communities plays a significant role in disease prevention, control, and monitoring. However, there are several limitations to these systems, including that the platforms are generally isolated, the patient health information and medical resources are not effectively integrated, and the “Internet Plus Healthcare” technology model is not implemented throughout the patient consultation process.

Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficiency of the application of a hospital case management information system in a general hospital in the context of chronic respiratory diseases as a model case.

Methods: A chronic disease management information system was developed for use in general hospitals based on internet technology, a chronic disease case management model, and an overall quality management model. Using this system, the case managers provided sophisticated inpatient, outpatient, and home medical services for patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Chronic respiratory disease case management quality indicators (number of managed cases, number of patients accepting routine follow-up services, follow-up visit rate, pulmonary function test rate, admission rate for acute exacerbations, chronic respiratory diseases knowledge awareness rate, and patient satisfaction) were evaluated before (2019‐2020) and after (2021‐2022) implementation of the chronic disease management information system.

Results: Before implementation of the chronic disease management information system, 1808 cases were managed in the general hospital, and an average of 603 (SD 137) people were provided with routine follow-up services. After use of the information system, 5868 cases were managed and 2056 (SD 211) patients were routinely followed-up, representing a significant increase of 3.2 and 3.4 times the respective values before use ( U =342.779; P <.001). With respect to the quality of case management, compared to the indicators measured before use, the achievement rate of follow-up examination increased by 50.2%, the achievement rate of the pulmonary function test increased by 26.2%, the awareness rate of chronic respiratory disease knowledge increased by 20.1%, the retention rate increased by 16.3%, and the patient satisfaction rate increased by 9.6% (all P <.001), while the admission rate of acute exacerbation decreased by 42.4% (P <.001) after use of the chronic disease management information system.

Conclusions: Use of a chronic disease management information system improves the quality of chronic respiratory disease case management and reduces the admission rate of patients owing to acute exacerbations of their diseases.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are examples of common chronic respiratory diseases. The prevalence of COPD among people 40 years and older in China is estimated to be 13.7%, with the total number of patients reaching nearly 100 million. The lengthy disease cycle, recurrent acute exacerbations, and low control rate were found to have a significant impact on the prognosis and quality of life of middle-aged and older patients with COPD [ 1 , 2 ]. Therefore, to decrease the morbidity and disability rates and enhance the quality of life of all patients with chronic respiratory diseases, it is crucial to investigate effective prevention and treatment methods and establish a life cycle management model for chronic respiratory diseases.

Since the development of information technology, the internet and medical technology have been applied to the management of chronic diseases [ 3 ]. The chronic disease information systems adopted in hospitals and communities, along with mobile medical apps, can enhance the self-management capabilities of patients and play a significant role in disease prevention, control, and monitoring [ 4 - 9 ]. However, the existing platforms are generally isolated, the patient health information and medical resources are not effectively integrated, and the Internet Plus Healthcare technology model is not implemented throughout the patient consultation process [ 3 , 9 ].

Yulin First People’s Hospital developed a chronic disease management information system based on the hospital information system (HIS) to fully and effectively utilize the medical resources in hospitals and to better support and adapt the system to the needs of patients with chronic diseases. In this study, we evaluated the impact of the use of this system on the efficacy of case management for patients with chronic respiratory diseases.

Chronic Respiratory Diseases Case Management Model Prior to Implementation of the Chronic Disease Management Information System

Yulin First People’s Hospital is a public grade-3 general hospital with 2460 open beds, a specialty clinic in the Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, and 180 beds in the Inpatient Department. Chronic respiratory diseases case management was initiated in 2019, which did not involve the use of an information system and was implemented by a chronic respiratory diseases case management team led by two nurses qualified as case managers, one chief physician, two supervisor nurses, and one technician. Under this system, patients with COPD, bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, pulmonary thromboembolism, lung cancer, and lung nodules were managed using the traditional inpatient-outpatient-home chronic respiratory diseases case management model, including 1024 cases managed from 2019 to 2020. Except for medical prescriptions and electronic medical records, the patient case management information such as the basic information form, follow-up form, patient enrollment form, inpatient follow-up register, patient medication and inhalation device use records, smoking cessation and vaccination records, and pulmonary rehabilitation and health education records was managed using Microsoft Excel forms that were regularly printed for filing.

Establishment of a Management Information System for Chronic Diseases

The information carrier forming the basis of the management information system is constituted by the model of internet technology, chronic disease case management models, and overall quality management. The key technology is to establish a scientific, refined, and feasible follow-up pathway according to the methods and procedures of chronic disease case management based on the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of single chronic diseases. The closed-loop management of the clinical pathway was conducted in accordance with the Deming cycle (plan-do-check-act), and dynamic monitoring of single-disease health-sensitive and quality-sensitive indicators was carried out. The successfully developed system was installed on the hospital server to connect personal terminals (medical terminals and customer apps) to the existing HIS, which includes electronic medical records and medical advice.

Using the single-disease path assessment or plan scale as a framework, the system can automatically collect and integrate the majority of the medical information of patients with chronic respiratory diseases and provide these patients with inpatient, outpatient, and home intelligent medical services. Patients with chronic diseases who enroll in use of the system can use the app to schedule appointments for medical guidance, payment, and result queries; receive health guidance information; perform self-health assessments; write a treatment diary; and obtain medical communication materials.

The medical terminal consists of five functional modules: user entry, data statistics and query, quality control, knowledge base, and module management. As the core of the system, the user entry module can manage case information in seven steps: enrollment, assessment, planning, implementation, feedback, evaluation, and settlement [ 10 - 14 ]. Each step has a corresponding assessment record scale as well as the health-sensitive and quality-sensitive indicators. The structure of the HIS-based chronic disease management information system is shown in Figure 1 .

Implementation of the Chronic Disease Information Management System

Using the chronic disease management information system, two full-time case managers oversaw the case management of 2747 patients diagnosed with six diseases among chronic respiratory diseases between 2021 and 2022. The operation process was broken down into enrollment, assessment, planning, implementation, evaluation, feedback, and settlement stages.

Case managers entered the system through the medical app, selected a disease and an enrolled patient from the list of patients (the system automatically captures the patient’s name and ID number according to the International Classification of Diseases [ ICD ] code) in accordance with the chronic respiratory diseases diagnostic criteria to sign the enrollment contract and determine the relationship between the personal information and data [ 15 - 19 ].

The system can be seamlessly integrated with multiple workstations on the HIS to automatically capture the basic information, electronic medical records, medical advice, and inspection materials, and can generate questionnaires or assessment scales for patients with chronic respiratory diseases such as the COPD Assessment Test, Asthma Control Test, modified Medical Research Council scale, form for lung function test results, inhalation device technique evaluation form, 6-minute walk test record, rehabilitation assessment form, health promotion form, and nutritional assessment form. The above materials can be added or removed based on the requirements for individual patients.

The case managers drafted the follow-up plan based on the patient assessment criteria and included the patients on the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up lists. If the patient satisfied the self-management and indicator control requirements after follow-up, they could be settled and included in the annual follow-up cohort. Case managers can set up follow-up warning and treatment, involving the return visit plan, health education, follow-up content, pathway, and time, and notify the patients and nurses on day 7 and at months 1, 3, 6, and 12 after discharge. The nurses should promptly deal with patients who miss their scheduled follow-up visit.

Implementation

During the inpatient or outpatient care, supervising physicians, nurses, and patients collaborated with each other to implement the treatment. Case managers monitored the patients, evaluated them, documented the results, interpreted various test indicators, and provided health guidance. The chronic disease management information system acquired the corresponding data for chronic disease–sensitive indicators from outpatient and inpatient orders and medical records automatically. The chronic respiratory diseases management team reviewed the patients’ conditions and the dynamics of chronic disease–sensitive indicators to make accurate decisions based on the current situation. The outpatient physicians obtained the single-disease package advice and personalized prescriptions to modify the diagnosis and treatment scheme.

Case managers highlighted evaluation and health education. First, they assessed and examined the content of the previous education and recorded and analyzed the patients’ conditions, medication, diet, nutrition, rehabilitation exercises, and self-management. Second, they prepared the personalized health education plan, return visit plan, and rehabilitation plan, and used standardized courseware, educational videos, and health prescriptions to provide the patients with one-on-one health guidance. Finally, they sent the management tasks and educational contents to the phones of the patients for consolidating the learning in the hospital, as an outpatient, and at home.

Patients can access their biochemical, physical, and chemical data as well as chronic disease–sensitive indicators in the hospital, as an outpatient, and at home for self-health management. Case managers can also perform online assessment, appraisal, and guidance via telephone, WeChat, and the chronic disease information system and record the data. Client mobile terminals can receive SMS text message alerts and the main interface of the chronic disease information system would display reminders of follow-up and return visits within ±7 days.

If a patient was out of contact for 3 months, died, or refused to accept the treatment, case managers could settle the case.

Evaluation of the Effect of Implementing the Chronic Disease Management Information System

Evaluation method.

In accordance with case quality management indicators [ 20 ], two full-time case managers collected and evaluated data in the process of the follow-up procedure. To reduce the potential for evaluation bias, the case managers consistently communicated and learned to standardize the evaluation method. The cases were divided based on different chronic respiratory diseases case management models (ie, before and after use of the chronic disease information system). The following case management quality indicators were evaluated under the noninformation system management model (2019‐2020) and under the chronic disease management information system model (2021‐2022): number of managed cases, number of patients accepting routine follow-up services, follow-up visit rate, pulmonary function test rate, admission rate for acute exacerbations, chronic respiratory diseases knowledge awareness rate, and patient satisfaction. Excel sheets were used to acquire data prior to incorporation of the chronic disease management information system into the new information system.

Evaluation Indicators

The annual number of cases was calculated as the sum of the number of newly enrolled patients and the number of initially enrolled patients. The number of cases was calculated as the sum of the number of cases in different years. The number of routine follow-up visits represents the number of patients who completed the treatment plan. The follow-up visit rate was calculated as the number of completed follow-up visits in the year divided by the number of planned follow-up visits in the same year. The pulmonary function test rate was calculated as the number of pulmonary function tests completed for patients scheduled for follow-up during the year divided by the number of pulmonary function tests for patients scheduled for follow-up during the year. The admission rate for acute exacerbations was calculated as the number of recorded patients admitted to the hospital due to acute exacerbations divided by the total number of patients recorded. The chronic respiratory diseases knowledge awareness rate was determined by the number of people having sufficient knowledge divided by the total number of people tested. This knowledge indicator was based on the self-prepared chronic respiratory diseases knowledge test scale, which consists of 10 items determined using the Delphi method (following expert consultation) through review of the literature, including common symptoms, disease hazards, treatment medication, diet, living habits, exercise, negative habits affecting the disease, regular review items, effective methods for cough and sputum removal, appointments, and follow-ups. The content of the questionnaire was refined by disease type, and the reviewers included 11 personnel with the title of Deputy Chief Nurse or above in the Internal Medicine Department of the hospital. The expert authority coefficients were 0.85 and 0.87 and the coordination coefficients were 0.50 and 0.67 for the two rounds of review, respectively; the χ 2 test showed a statistically significant value of P =.01. Patient satisfaction was assessed with a self-made questionnaire that showed good internal reliability (Cronbach α=0.78) and content validity (0.86). The questionnaire items included the reminder of return visits, practicability of health education content, and service attitude of medical staff; the full-time case managers surveyed the patients (or their caregivers) at the time of return visits after the third quarter of each year. Satisfaction items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale with a score of 1‐5, and a mean ≥4 points for an individual indicated satisfaction. Patient satisfaction was then calculated as the number of satisfied patients divided by the total number of managed patients.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 16.0 software was used for data analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare continuous variables between groups and the χ 2 test was performed to compare categorical variables between groups. P <.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Yulin First People’s Hospital (approval number: YLSY-IRB-RP-2024005). The study did not interfere with routine diagnosis and treatment, did not affect patients’ medical rights, and did not pose any additional risks to patients. Therefore, after discussion with the Ethics Committee of Yulin First People’s Hospital, it was decided to waive the requirement for informed consent from patients. Patients’ personal privacy and data confidentiality have been upheld throughout the study.

Characteristics of Patient Populations Before and After Implementation of the Information System

There was no significant difference in age and gender distributions in the patient populations that received care before and after implementation of the chronic disease management information system ( Table 1 ).

| Characteristic | Before use (n=1024) | After use (n=2747) | ² value | value | ||

| 1.046 | 1 | .31 | ||||

| Men | 677 (66.1) | 1767 (64.3) | ||||

| Women | 347 (33.9) | 980 (35.7) | ||||

| 0.997 | 3 | .80 | ||||

| <30 | 26 (2.6) | 73 (2.7) | ||||

| 30-59 | 370 (36.1) | 1013 (36.9) | ||||

| 60-79 | 510 (49.8) | 118 (11.5) | ||||

| >80 | 1322 (48.1) | 339 (12.3) | ||||

Comparison of Workload Before and After Implementation of the Information Management System

Before use of the system, 1808 cases were managed, with a mean of 603 (SD 137) cases having routine follow-up visits. After use of the system, 5868 cases were managed, with a mean of 2056 (SD 211) routine follow-up visits. Therefore, the number of managed cases and the number of follow-up visits significantly increased by 3.2 and 3.4 times, respectively, after use of the system (U =342.779; P< .001).

Comparison of Quality Indicators of Managed Cases Before and After Implementation of the Information System

The quality indicators in the two groups are summarized in Table 2 . Compared with the corresponding indicators before use of the system, the follow-up visit rate increased by 50.2%, the pulmonary function test rate increased by 26.2%, the chronic respiratory diseases knowledge awareness rate increased by 20.1%, the retention rate increased by 16.3%, and the patient satisfaction increased by 9.6%; moreover, the admission rate for acute exacerbations decreased by 42.4%.

| Quality indicators | Before use (n=1024), n (%) | After use (n=2747), n (%) | ² value ( =1) | value |

| Subsequent visit rate | 209 (20.4) | 1939 (70.6) | 7.660 | <.001 |

| Lung function test achievement rate | 190 (18.6) | 1231 (44.8) | 2.190 | <.001 |

| CRD knowledge awareness rate | 443 (43.3) | 1742 (63.4) | 1.243 | <.001 |

| Retention rate | 787 (76.9) | 2560 (93.2) | 1.995 | <.001 |

| Acute exacerbation admission rate | 663 (64.7) | 613 (22.3) | 5.999 | <.001 |

| Patient satisfaction | 862 (84.2) | 2577 (93.8) | 86.190 | .01 |

a CRD: chronic respiratory disease.

Principal Findings

The main purpose of this study was to build a chronic disease management information system and apply it to the case management of chronic respiratory diseases. Our evaluation showed that the chronic disease management information system not only improves the efficiency and quality of case management but also has a benefit for maintaining the stability of the condition for patients with respiratory diseases, reduces the number of acute disease exacerbations, increases the rate of outpatient return, and improves patients’ adherence with disease self-management. Thus, a chronic disease management information system is worth popularizing and applying widely.

Value of the HIS-Based Chronic Disease Management Information System

Chronic diseases constitute a significant public health issue in China. Public hospitals play important roles in the health service system, particularly large-scale public hospitals with the most advanced technologies, equipment, and enormous medical human resources, which can greatly aid in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases and also serve as important hubs for the graded treatment of chronic diseases. Moreover, a significant number of patients with chronic diseases visit large hospitals, making them important sources of big data on chronic diseases [ 21 ]. Adoption of an HIS-based chronic disease management information system can make full use of and exert the advantages of large-scale public hospitals in terms of labor, technology, and equipment in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of chronic diseases; enhance the cohesiveness of the case management team in chronic disease management; and achieve prehospital, in-hospital, and posthospital continuity of care for patients with chronic diseases. Overall, use of a chronic disease management information system can enhance the quality and efficiency of chronic disease management and lay a good foundation for teaching and research on chronic diseases.

Improved Efficiency of Case Management

China was relatively late in applying case management practices, and chronic disease management has traditionally been primarily conducted offline [ 14 , 20 ] or supplemented by management with apps and WeChat [ 7 , 8 ]. Traditional case management methods require case managers to manually search, record, store, query, count, and analyze information. This manual process necessitates substantial time and makes it challenging to realize a comprehensive, systematic, and dynamic understanding of patient information, resulting in a small number of managed cases and follow-up visits. With the application of information technology, use of an HIS-based chronic disease monitoring and case management system can automatically extract and integrate patient information, thereby increasing the efficiency of chronic disease management and reduce costs [ 4 , 22 ]. In this study, two case managers played leading roles both before and after implementation of the information system; however, compared with the situation before the use of the system, the numbers of both managed cases and of follow-up visits increased, reaching 3.2 and 3.4 times the preimplementation values, respectively. The information system can automatically obtain a patient’s name and ID number based on the ICD code, which can expand the range of enrollment screening and appoint the register of patients as planned. In addition, the information system can automatically obtain outpatient, inpatient, and home medical information for the postillness life cycle management of patients. Moreover, the intuitive, clear, and dynamic indicator charts on the system can save a significant amount of time for diagnosis and treatment by medical staff, while the paperless office and online data-sharing functions can essentially solve the problem of managing files by case managers to ultimately enhance efficiency.

Improved Quality of Case Management

According to evidence-based medicine, the seven steps of case management represent the optimal clinical pathway [ 10 - 14 , 22 ]. In this study, the concept of an Internet-Plus medical service was introduced; that is, the chronic disease management information system was established based on the HIS data and case management model [ 22 ] and the function of a mobile medical terminal app was incorporated in the system [ 6 , 7 ]. Compared with the noninformation system case management model, this system has several advantages. First, owing to the swift management mode, it can overcome the limitations of time and space [ 4 - 8 ]. Second, multichannel health education and communication can enhance patients’ knowledge and skills, as well as their compliance with self-management, based on diversified forms of image data such as graphics and audio [ 6 , 22 ]. Third, the use of intelligent management can remind doctors and patients to complete management work and follow-up visits as planned, and to perform intelligent pushes of patient outcome indicators to improve confidence in the treatment [ 22 ]. Fourth, this system enables information sharing and big data analysis, as well as multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment based on the matching of doctor-patient responsibility management, which can be more conducive to the precise health management of patients.

Compared with the traditional case management model, information-based case management significantly increased the follow-up visit rate, lung function test rate, chronic respiratory diseases knowledge awareness rate of patients, patient satisfaction rate, and retention rate. Among these indicators, the follow-up visit rate and lung function test rate represent aspects related to the patients’ own management of their condition [ 1 ]. The results of this study are consistent with previous findings related to information-based management of chronic diseases in China, demonstrating that such a management system was more conducive to planned, systematic, and personalized education and follow-up by the case management team, thereby promoting the virtuous cycle of compliance with self-management and reducing the number of acute exacerbations among patients with chronic respiratory diseases, ultimately enhancing the precision of medical resource allocation and hospital management [ 22 , 23 ].

Helping Patients With COPD Maintain Stability of Their Condition

The admission rate for acute exacerbations serves as a common indicator of the quality of the treatment of chronic respiratory diseases [ 23 ]. The deployment of a clinical pathway–based hospital case management information system significantly reduced the admission rate for acute exacerbations and enhanced the quality of treatment for chronic respiratory diseases, indicating its high clinical significance. There are several reasons for these observed benefits. First, home care and self-management are essential in the management of chronic respiratory diseases. The information-based case management model improved the patients’ knowledge and skills along with their compliance with self-management. Consequently, the standardized self-management process helped to reduce the number of acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory diseases and thus lowered the admission rate. Second, the information-based case management model increased the regular return rate, which allowed the medical staff to identify the potential risk factors for acute exacerbations in a timely manner, deal with them when they occur, and prepare personalized treatment plans and precise health management schemes. This consequently enabled adjustment of treatment schemes in real time, reduced the number of admissions due to acute exacerbations, and lowered the readmission rate. For hospitals interested in implementing a similar model, we suggest first conducting a detailed review of the current situation prior to making adequate changes based on the relevant disease and patient populations.

Consequently, the HIS-based case information management model could improve efficiency, enhance the quality of case management, and aid in stabilizing the conditions of patients with chronic respiratory diseases. In contrast to the hospital case management information system reported by Yuan et al [ 22 ], the system described in this study includes a personal terminal app. Previous studies confirmed that a stand-alone mobile health app could improve patient compliance and disease control [ 6 - 8 ]; thus, whether this system can be used to manage specialized disease cohorts for patients with chronic diseases remains to be determined. In this study, the effect on the retention rate of patients was confirmed; however, the overall operational indicators for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases should be further determined.

With the advancement of information technology, the internet and medical technology have been applied to the management of chronic diseases. As an information-based platform for the case management of patients with chronic respiratory diseases, a newly developed chronic disease management information system was introduced in this study. This system is capable of designing the follow-up time registration, follow-up content, approaches, methods, quality control, and feedback process for a single chronic respiratory disease via the single-disease clinical pathway following the case management process (enrollment, assessment, planning, implementation, feedback, and evaluation). Use of this system can encourage patients with chronic respiratory diseases to adhere to regular follow-up and form an outpatient-inpatient-home chronic disease management strategy. This can help in reducing the admission rate for acute exacerbations, increase the return visit rate, and improve the correctness and compliance of home self-management of patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Owing to these benefits, wide adoption of such information systems for the management of chronic diseases can offer substantial economic and social value.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to all the people who provided help with our article. This study was supported by a grant from Yulin City Science and Technology Planning Project (20202002).

Data Availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' Contributions

YML, YZX, XLS, and YXL designed this study. XLS and XJC wrote the draft of the paper. YML, YZX, and YC contributed final revisions to the article. XJC, HC, and YC collected the data. XJC, YML, YXL, and HC performed the statistical analysis. YML received funding support. All authors read and approved the final draft of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

- Anaev EK. Eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review. Ter Arkh. Oct 11, 2023;95(8):696-700. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Shakeel I, Ashraf A, Afzal M, et al. The molecular blueprint for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a new paradigm for diagnosis and therapeutics. Oxid Med Cell Longev. Dec 2023;2023:2297559. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Morimoto Y, Takahashi T, Sawa R, et al. Web portals for patients with chronic diseases: scoping review of the functional features and theoretical frameworks of telerehabilitation platforms. J Med Internet Res. Jan 27, 2022;24(1):e27759. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Donner CF, ZuWallack R, Nici L. The role of telemedicine in extending and enhancing medical management of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicina. Jul 18, 2021;57(7):726. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Wu F, Burt J, Chowdhury T, et al. Specialty COPD care during COVID-19: patient and clinician perspectives on remote delivery. BMJ Open Respir Res. Jan 2021;8(1):e000817. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Hallensleben C, van Luenen S, Rolink E, Ossebaard HC, Chavannes NH. eHealth for people with COPD in the Netherlands: a scoping review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. Jul 2019;14:1681-1690. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Gokalp H, de Folter J, Verma V, Fursse J, Jones R, Clarke M. Integrated telehealth and telecare for monitoring frail elderly with chronic disease. Telemed J E Health. Dec 2018;24(12):940-957. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- McCabe C, McCann M, Brady AM. Computer and mobile technology interventions for self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. May 23, 2017;5(5):CD011425. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Briggs AM, Persaud JG, Deverell ML, et al. Integrated prevention and management of non-communicable diseases, including musculoskeletal health: a systematic policy analysis among OECD countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(5):e001806. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Franek J. Home telehealth for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2012;12(11):1-58. [ Medline ]

- Shah A, Hussain-Shamsy N, Strudwick G, Sockalingam S, Nolan RP, Seto E. Digital health interventions for depression and anxiety among people with chronic conditions: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. Sep 26, 2022;24(9):e38030. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Sugiharto F, Haroen H, Alya FP, et al. Health educational methods for improving self-efficacy among patients with coronary heart disease: a scoping review. J Multidiscip Healthc. Feb 2024;17:779-792. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Metzendorf MI, Wieland LS, Richter B. Mobile health (m-health) smartphone interventions for adolescents and adults with overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Feb 20, 2024;2(2):CD013591. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Reig-Garcia G, Suñer-Soler R, Mantas-Jiménez S, et al. Assessing nurses' satisfaction with continuity of care and the case management model as an indicator of quality of care in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Jun 19, 2021;18(12):6609. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Aggelidis X, Kritikou M, Makris M, et al. Tele-monitoring applications in respiratory allergy. J Clin Med. Feb 4, 2024;13(3):898. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Seid A, Fufa DD, Bitew ZW. The use of internet-based smartphone apps consistently improved consumers' healthy eating behaviors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Digit Health. 2024;6:1282570. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Verma L, Turk T, Dennett L, Dytoc M. Teledermatology in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2024;28(2):153-157. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Tański W, Stapkiewicz A, Szalonka A, Głuszczyk-Ferenc B, Tomasiewicz B, Jankowska-Polańska B. The framework of the pilot project for testing a telemedicine model in the field of chronic diseases - health challenges and justification of the project implementation. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2023;51(6):674-681. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Popp Z, Low S, Igwe A, et al. Shifting from active to passive monitoring of Alzheimer disease: the state of the research. J Am Heart Assoc. Jan 16, 2024;13(2):e031247. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Sagare N, Bankar NJ, Shahu S, Bandre GR. Transforming healthcare: the revolutionary benefits of cashless healthcare services. Cureus. Dec 2023;15(12):e50971. [ CrossRef ] [ Medline ]

- Noncommunicable Diseases, Rehabilitation and Disability (NCD), Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting (SMR) WHO Team. Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor. World Health Organization; 2017. URL: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513029 [Accessed 2024-05-09]

- Yuan W, Zhu T, Wang Y, et al. Research on development and application of case management information system in general hospital. Nurs Res. 2022;36(12):2251-2253.

- 2020 GOLD report. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2020. URL: https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/ [Accessed 2024-05-09]

Abbreviations

| chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| hospital information system |

| : |

Edited by Christian Lovis; submitted 15.06.23; peer-reviewed by Kuang-Ming Kuo; final revised version received 14.04.24; accepted 17.04.24; published 19.06.24.

© Yi-Zhen Xiao, Xiao-Jia Chen, Xiao-Ling Sun, Huan Chen, Yu-Xia Luo, Yuan Chen, Ye-Mei Liang. Originally published in JMIR Medical Informatics (https://medinform.jmir.org), 19.6.2024.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work, first published in JMIR Medical Informatics, is properly cited. The complete bibliographic information, a link to the original publication on https://medinform.jmir.org/ , as well as this copyright and license information must be included.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

A proposed methodology for the dynamic standard evaluation of water quality in estuaries: a case study of the pearl river estuary, 1. introduction, 2. method construction, 2.1. classification of seawater quality in the seawater quality standards, 2.2. surface water function and standard classification in surface water environmental quality standards, 2.3. construction of dynamic standard methods for water quality in estuarine areas, 3. application example: evaluation of water quality in the pre (pb, ph, pi, do, cu, zn, cd, and hg), 3.1. description of the monitoring area, 3.2. sample collection and analysis, 3.3. analytical quality assurance, 3.4. results, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Li, M.; Pang, B.; Lan, W.; Fu, J. Delineation of estuarine mixed zone and establishment of nutrient standard limits. China Environ. Monit. 2020 , 36 , 74–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alber, M. A conceptual model of estuarine freshwater inflow management. Estuaries 2002 , 25 , 1246–1261. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Bao, M.; Li, X. Analysis of water quality evaluation standards for estuaries. Jiangsu Water Resour. 2022 , 4 , 62–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, J.; Han, G.; Zhang, Z. The Latest Progress in International Marine Environmental Monitoring and Evaluation ; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meng, W. Research on China’s Ocean Engineering and Technology Development Strategy: Ocean Environment and Ecology Volume ; Ocean Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen, J. Estuarine Water Eco-Health Assessment Technical Method and Application ; Ocean University of China: Qingdao, China, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang, F.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Yu, L.; Wang, J. Analysis on the problems of environmental quality standards for surface water and seawater in China. Mar. Dev. Manag. 2018 , 35 , 36–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- GB3097-1997 ; National Seawater Quality Standard of the People’s Republic of China. National Environmental Protection Administration: Beijing, China, 1997.

- GB3838-2002 ; General Administration of Quality Supervision of Inspection and Quarantine of China. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China Environmental Quality Standard for Surface Water. State Environmental Protection Administration: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Quan, Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, L.; Shi, B. Water quality analysis and evaluation of main estuaries in Qinhuangdao. Bull. Oceanol. Limnol. 2016 , 38 , 24–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Zheng, B. Problems and countermeasures of water environmental management in estuaries. Res. Environ. Sci. 2017 , 30 , 645–653. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bricker, S.B.; Ferreira, J.G.; Simas, T. An integrated methodology for assessment of estuarine trophic status. Ecol. Model. 2003 , 169 , 39–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ireland Environmental Protection Agency. Water Quality in Ireland 2001–2003 ; Environmental Protection Agency: Wexford, Ireland, 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- OSPAR Commission. OSPAR Integrated Report 2003 on the Eutrophication Status of the OSPAR Maritime Area Based upon the First Application of the Comprehensive Procedure ; The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic: Paris, France, 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Office of Environment and Heritage. Assessing Estuary Ecosystem Health: Sampling, Data Analysis and Reporting Protocols ; State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage: Parramatta, NSW, Australia, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peng, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Q. Ecosystem health assessment for Huangbai river based on PSR model. Water Resour. Prot. 2016 , 32 , 141–153. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ye, S.F.; Liu, X.; Ding, D.W. Ecosystem health assessment of the Changjiang river estuary: Indicator system and its primarily assessment. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2007 , 29 , 128–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council, Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New Zealand. Australia and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality ; Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conberra Council: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- European Commission. Guidance on Typology, Reference Conditions and Classification Systems for Transitional and Coastal Water ; European Commission: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Estuarine and Coastal Marine Waters: Bioassessment and Biocriteria Technical Guidance ; Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- European Commission. Common Implementation Stategy for the Water Framework Directive (2000/30/EC-Technical Guidance for Deriving Environmental Quality Standards ; European Commission: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. National Estuary Program Coastal Condition Report. Chapter 5: Gulf of Mexico National Estuary Program Coastal Condition, Sarasota Bay Estuary Program ; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schuwirth, N. Towards an integrated surface water quality assessment: Aggregation over multiple pollutants and time. Water Res. 2020 , 186 , 761–774. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Reichert, J.; Schellenberg, J.; Schubert, P.; Wilke, T. Responses of reef building corals to microplastic exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2018 , 237 , 955–960. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bawiec, A.; Paweska, K.; Jarzab, A. Changes in the Microbial Composition of Municipal Wastewater Treated in Biological Processes. J. Eco. Eng. 2016 , 17 , 41–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lal, P.P.; Juste-Poinapen Ms, N.; Poinapen, J. Assessing the water quality of Suva foreshore for the establishment of estuary and marine recreational water guidelines in the Fiji Islands. Water Sci. Technol. 2021 , 84 , 3040–3054. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Singh, V.P.; He, Y.; Bai, X. An improved index for water quality evaluation in an estuary region: A case study in the Eastern Pearl River Delta, China. Water Policy 2019 , 21 , 310–325. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tri, D.Q.; Linh, N.T.M.; Thai, T.H.; Kandasamy, J. Application of 1D–2D coupled modeling in water quality assessment: A case study in Ca Mau Peninsula, Vietnam. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2019 , 113 , 83–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tao, W.; Niu, L.; Dong, Y.; Fu, T.; Lou, Q. Nutrient pollution and its dynamic source-sink pattern in the Pearl River Estuary (South China). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021 , 8 , 713907. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Li, X.Q.; Lu, C.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Zhao, H.D.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, H.B. Low dissolved oxygen in the Pearl River estuary in summer: Long-term spatio-temporal patterns, trends, and regulating factors. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020 , 151 , 110814. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tao, W.; Niu, L.X.; Liu, F.; Cai, H.Y.; Ou, S.Y.; Zeng, D.N.; Lou, Q.S.; Yang, Q.S. Influence of river-tide dynamics on phytoplankton variability and their ecological implications in two Chinese tropical estuaries. Ecol. Indic. 2020 , 115 , 106458. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Niu, L.X.; Cai, H.Y.; Jia, L.W.; Luo, X.X.; Tao, W.; Dong, Y.H.; Yang, Q.S. Metal pollution in the Pearl River Estuary and implications for estuary management: The influence of hydrological connectivity associated with estuarine mixing. EES 2021 , 225 , 112747. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tian, F.G.; Ni, Z.X.; Huang, B.B.; Lou, Q.S.; Zhong, Y.H.; Deng, W. Distribution characters of heavy metals in seawater and surface sediments in Daya Bay. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2022 , 41 , 462–474. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tao, W.; Li, H.D.; Zhang, W.P.; Lou, Q.S.; Gong, J.; Ye, J.J. Characteristics of Heavy Metals in Seawater and Sediments from Daya Bay (South China): Environmental Fates, Source Apportionment and Ecological Risks. Sustainability 2021 , 13 , 10237. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Similarities and Differences | Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water (GB3838-2002) | Seawater Quality Standard (GB3097-1997) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Categories Correspondence Relationship | Class I | Source water and nature reserves | N/A | |

| Class II | First-grade protection area of centralized surface drinking water sources, habitat of rare aquatic organisms, and feeding ground for young fish | Marine nature reserves, rare and endangered marine life reserves, and marine fishery waters | Class I | |

| Class III | Class II protection zone of centralized surface water sources for drinking water, fishery waters such as aquaculture, and swimming areas | Aquaculture areas, bathing beaches, and industrial water areas directly related to human consumption | Class II | |

| Class IV | General industrial water areas and entertainment water areas where the human body is not directly in contact | General industrial water area, coastal scenic tourist area | Class III | |

| Class V | Agricultural water use areas and general landscape requirements for water areas | Marine port waters and marine development operation areas | Class IV | |

| Element | A | A | A | A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb (mg/L) | ≤0.001 | ≤0.005 | ≤0.010 | ≤0.050 |

| pH | 7.8~8.5 | 6.8~8.8 | ||

| PI (mg/LO ) | ≤2 | ≤3 | ≤4 | ≤5 |

| DO (mg/L) | >6 | >5 | >4 | >3 |

| Cu (mg/L) | ≤0.005 | ≤0.010 | ≤0.050 | |

| Zn (mg/L) | ≤0.020 | ≤0.050 | ≤0.10 | ≤0.50 |

| Cd (mg/L) | ≤0.001 | ≤0.005 | ≤0.010 | |

| Hg (mg/L) | ≤0.00005 | ≤0.0002 | ≤0.0005 | |

| Element | B | B | B | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb (mg/L) | ≤0.01 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.1 |

| pH | 6~9 | |||

| PI (mg/LO ) | ≤4 | ≤6 | ≤10 | ≤15 |

| DO (mg/L) | ≥6 | ≥5 | ≥3 | ≥2 |

| Cu (mg/L) | ≤1.0 | ≤1.0 | ≤1.0 | ≤1.0 |

| Zn (mg/L) | ≤1.0 | ≤1.0 | ≤2.0 | ≤2.0 |

| Cd (mg/L) | ≤0.005 | ≤0.005 | ≤0.005 | ≤0.01 |

| Hg (mg/L) | ≤0.00005 | ≤0.0001 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.001 |

| Sites | S01 | S02 | S03 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | Water depth (m) | 0.5 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 7.0 |

| Salinity (S) | 16.453 | 17.641 | 17.565 | 17.643 | 15.405 | 16.439 | |

| Pb (mg/L) | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0010 | 0.0013 | 0.0007 | 0.0006 | |

| pH | 7.62 | 7.62 | 7.64 | 7.62 | 7.57 | 7.58 | |

| PI (mg/LO ) | 1.61 | 1.90 | 1.42 | 2.00 | 1.53 | 1.92 | |

| DO (mg/L) | 5.38 | 5.32 | 5.82 | 5.42 | 5.27 | 5.33 | |

| Cu (mg/L) | 0.0020 | 0.0016 | 0.0020 | 0.0022 | 0.0026 | 0.0022 | |

| Zn (mg/L) | 0.0069 | 0.0072 | 0.0109 | 0.0076 | 0.0071 | 0.0071 | |

| Cd (mg/L) | 0.00037 | 0.00038 | 0.00044 | 0.00042 | 0.0004 | 0.00043 | |

| Hg (mg/L) | 0.000028 | 0.000042 | 0.000030 | 0.000038 | 0.000028 | 0.000042 | |

| Rising tide | Water depth (m) | 0.5 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 8.0 |

| Salinity (S) | 15.660 | 15.663 | 15.435 | 15.743 | 13.551 | 14.529 | |

| Pb (mg/L) | 0.0008 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | |

| pH | 7.58 | 7.43 | 7.51 | 7.51 | 7.38 | 7.38 | |

| PI (mg/LO ) | 2.56 | 2.15 | 3.02 | 3.15 | 3.49 | 3.12 | |

| DO (mg/L) | 5.24 | 5.24 | 4.93 | 4.76 | 4.39 | 4.58 | |

| Cu (mg/L) | 0.0016 | 0.0018 | 0.0017 | 0.0015 | 0.0015 | 0.0015 | |

| Zn (mg/L) | 0.0079 | 0.0079 | 0.0078 | 0.0066 | 0.0073 | 0.0068 | |

| Cd (mg/L) | 0.00037 | 0.0004 | 0.00033 | 0.00033 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | |

| Hg (mg/L) | 0.000024 | 0.000034 | 0.000031 | 0.000034 | 0.000028 | 0.000037 | |

| Sites | S01 | S02 | S03 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | |||||||

| Pb | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class II | Class I | Class I | |

| pH | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | |

| PI | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| DO | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | |

| Cu | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Zn | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Cd | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Hg | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Rising tide | |||||||

| Pb | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| pH | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | |

| PI | Class II | Class II | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | |

| DO | Class II | Class II | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | |

| Cu | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Zn | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Cd | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Hg | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| Sites | Depth (m) | Salinity (S) | C (mg/L) | C (mg/L) | C (mg/L) | C (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | S01 | 0.5 | 16.453 | 0.0052 | 0.0262 | 0.0288 | 0.0735 |

| 8.0 | 17.641 | 0.0055 | 0.0277 | 0.0302 | 0.0752 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 17.565 | 0.0055 | 0.0276 | 0.0301 | 0.0751 | |

| 8.0 | 17.643 | 0.0055 | 0.0277 | 0.0302 | 0.0752 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 15.405 | 0.0050 | 0.0248 | 0.0276 | 0.0720 | |

| 7.0 | 16.439 | 0.0052 | 0.0261 | 0.0288 | 0.0735 | ||

| Rising tide | S01 | 0.5 | 15.660 | 0.0050 | 0.0251 | 0.0279 | 0.0724 |

| 7.0 | 15.663 | 0.0050 | 0.0251 | 0.0279 | 0.0724 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 15.435 | 0.0050 | 0.0248 | 0.0276 | 0.0721 | |

| 7.0 | 15.743 | 0.0050 | 0.0252 | 0.0280 | 0.0725 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 13.551 | 0.0045 | 0.0224 | 0.0255 | 0.0694 | |

| 8.0 | 14.529 | 0.0047 | 0.0237 | 0.0266 | 0.0708 |

| Sites | Depth (m) | Salinity (S) | C | C | C | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | S01 | 0.5 | 16.453 | 6.85~8.74 | 6.85~8.74 | 6.38~8.89 | 6.38~8.89 |

| 8.0 | 17.641 | 6.91~8.75 | 6.91~8.75 | 6.40~8.90 | 6.40~8.90 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 17.565 | 6.90~8.75 | 6.90~8.75 | 6.40~8.90 | 6.40~8.90 | |

| 8.0 | 17.643 | 6.91~8.75 | 6.91~8.75 | 6.40~8.90 | 6.40~8.90 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 15.405 | 6.79~8.72 | 6.79~8.72 | 6.35~8.89 | 6.35~8.89 | |

| 7.0 | 16.439 | 6.85~8.73 | 6.85~8.73 | 6.38~8.89 | 6.38~8.89 | ||

| Rising tide | S01 | 0.5 | 15.660 | 6.81~8.72 | 6.81~8.72 | 6.36~8.89 | 6.36~8.89 |

| 7.0 | 15.663 | 6.81~8.72 | 6.81~8.72 | 6.36~8.89 | 6.36~8.89 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 15.435 | 6.79~8.72 | 6.79~8.72 | 6.35~8.89 | 6.35~8.89 | |

| 7.0 | 15.743 | 6.81~8.72 | 6.81~8.72 | 6.36~8.89 | 6.36~8.89 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 13.551 | 6.70~8.69 | 6.70~8.69 | 6.31~8.88 | 6.31~8.88 | |

| 8.0 | 14.529 | 6.75~8.71 | 6.75~8.71 | 6.33~8.88 | 6.33~8.88 |

| Sites | Depth (m) | Salinity (S) | C (mg/LO ) | C (mg/LO ) | C (mg/LO ) | C (mg/LO ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | S01 | 0.5 | 16.453 | 2.940 | 4.410 | 6.821 | 9.701 |

| 8.0 | 17.641 | 3.008 | 4.512 | 7.024 | 10.040 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 17.565 | 3.004 | 4.506 | 7.011 | 10.019 | |

| 8.0 | 17.643 | 3.008 | 4.512 | 7.025 | 10.041 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 15.405 | 2.880 | 4.320 | 6.641 | 9.401 | |

| 7.0 | 16.439 | 2.939 | 4.409 | 6.818 | 9.697 | ||

| Rising tide | S01 | 0.5 | 15.660 | 2.895 | 4.342 | 6.685 | 9.474 |

| 7.0 | 15.663 | 2.895 | 4.343 | 6.685 | 9.475 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 15.435 | 2.882 | 4.323 | 6.646 | 9.410 | |

| 7.0 | 15.743 | 2.900 | 4.349 | 6.699 | 9.498 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 13.551 | 2.774 | 4.162 | 6.323 | 8.872 | |

| 8.0 | 14.529 | 2.830 | 4.245 | 6.491 | 9.151 |

| Sites | Depth (m) | Salinity (S) | C (mg/L) | C (mg/L) | C (mg/L) | C (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | S01 | 0.5 | 16.453 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.470 | 2.470 |

| 8.0 | 17.641 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.504 | 2.504 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 17.565 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.502 | 2.502 | |

| 8.0 | 17.643 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.504 | 2.504 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 15.405 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.440 | 2.440 | |

| 7.0 | 16.439 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.470 | 2.470 | ||

| Rising tide | S01 | 0.5 | 15.660 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.447 | 2.447 |

| 7.0 | 15.663 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.448 | 2.448 | ||

| S02 | 0.5 | 15.435 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.441 | 2.441 | |

| 7.0 | 15.743 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.450 | 2.450 | ||

| S03 | 0.5 | 13.551 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.387 | 2.387 | |

| 8.0 | 14.529 | 6.000 | 5.000 | 3.415 | 2.415 |

| Sites | S01 | S02 | S03 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebb tide | |||||||

| salinity | 16.453 | 17.641 | 17.565 | 17.643 | 15.405 | 16.439 | |

| Pb | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| pH | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| PI | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| DO | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | |

| Rising tide | |||||||

| Salinity | 15.660 | 15.663 | 15.435 | 15.743 | 13.551 | 14.529 | |

| Pb | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | ClassI | Class I | |

| pH | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | Class I | |

| PI | Class I | Class I | Class II | Class II | Class II | Class II | |

| DO | Class II | Class II | Class III | Class III | Class III | Class III | |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. A Proposed Methodology for the Dynamic Standard Evaluation of Water Quality in Estuaries: A Case Study of the Pearl River Estuary. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024 , 12 , 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12071039

Wang Z, Zhang H. A Proposed Methodology for the Dynamic Standard Evaluation of Water Quality in Estuaries: A Case Study of the Pearl River Estuary. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering . 2024; 12(7):1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12071039

Wang, Zhongyuan, and Hongkang Zhang. 2024. "A Proposed Methodology for the Dynamic Standard Evaluation of Water Quality in Estuaries: A Case Study of the Pearl River Estuary" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 12, no. 7: 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse12071039

Article Metrics

Further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.