APA (7th Edition) Referencing Guide

- Information for EndNote Users

- Authors - Numbers, Rules and Formatting

- In-Text Citations

- Reference List

- Books & eBooks

- Book chapters

- Journal Articles

- Conference Papers

- Newspaper Articles

- Web Pages & Documents

- Specialised Health Databases

- Using Visual Works in Assignments & Class Presentations

- Using Visual Works in Theses and Publications

- Using Tables in Assignments & Class Presentations

- Custom Textbooks & Books of Readings

- ABS AND AIHW

- Videos (YouTube), Podcasts & Webinars

- Blog Posts and Social Media

- First Nations Works

- Dictionary and Encyclopedia Entries

- Personal Communication

- Theses and Dissertations

- Film / TV / DVD

- Miscellaneous (Generic Reference)

- AI software

APA 7th examples and templates

Apa formatting tips, thesis formatting, tables and figures, acknowledgements and disclaimers.

- What If...?

- Other Guides

- EscAPA7de - the APA escape room

- One Minute Video Series (APA)

You can view the samples here:

- APA Style Sample Papers From the official APA Style and Grammar Guidelines

Quick formatting notes taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association 7th edition

Use the same font throughout the text of your paper, including the title and any headings. APA lists the following options (p. 44):

- Sans serif fonts such as 11-point Calibri, 11 point-Arial, 10-point Lucida,

- Serif fonts such as 12-point Times new Roman, 11-point Georgia or 10-point Computer Modern.

(A serif font is one that has caps and tails - or "wiggly bits" - on it, like Times New Roman . The font used throughout this guide is a sans serif [without serif] font). You may want to check with your lecturer to see if they have a preference.

In addition APA suggests these fonts for the following circumstances:

- Within figures, use a sans serif font between 8 and 14 points.

- When presenting computer code, use a monospace font such as 10-point Lucida Console or 10-point Courier New.

- Footnotes: a 10-point font with single line spacing.

Line Spacing:

"Double-space the entire paper, including the title page, abstract, text, headings, block quotations, reference list, table and figure notes, and appendices, with the following exceptions:" (p. 45)

- Table and figures: Words within tables and figures may be single-, one-and-a-half- or double-spaced depending on what you decide creates the best presentation.

- Footnotes: Footnotes appearing at the bottom of the page to which they refer may be single-spaced and formatted with the default settings on your word processing program i.e. Word.

- Equations: You may triple- or quadruple-space before and after equations.

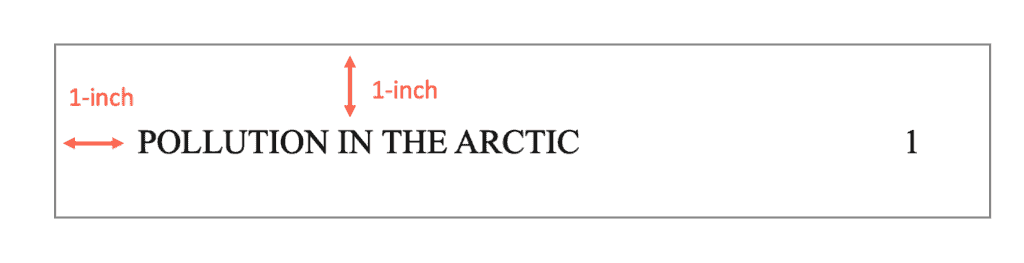

"Use 1 in. (2.54 cm) margins on all sides (top, bottom, left, and right) of the page." If your subject outline or lecturer has requested specific margins (for example, 3cm on the left side), use those.

"Align the text to the left and leave the right margin uneven ('ragged'). Do not use full justification, which adjusts the spacing between words to make all lines the same length (flush with the margins). Do not manually divide words at the end of a line" (p. 45).

Do not break hyphenated words. Do not manually break long DOIs or URLs.

Indentations:

"Indent the first line of every paragraph... for consistency, use the tab key... the default settings in most word-processing programs are acceptable. The remaining lines of the paragraph should be left-aligned." (p. 45)

Exceptions to the paragraph indentation requirements are as follows:

- Title pages to be centred.

- The first line of abstracts are left aligned (not indented).

- Block quotes are indented 1.27 cm (0.5 in). The first paragraph of a block quote is not indented further. Only the first line of the second and subsequent paragraphs (if there are any) are indented a further 1.27 cm (0.5 in). (see What if...Long quote in this LibGuide)

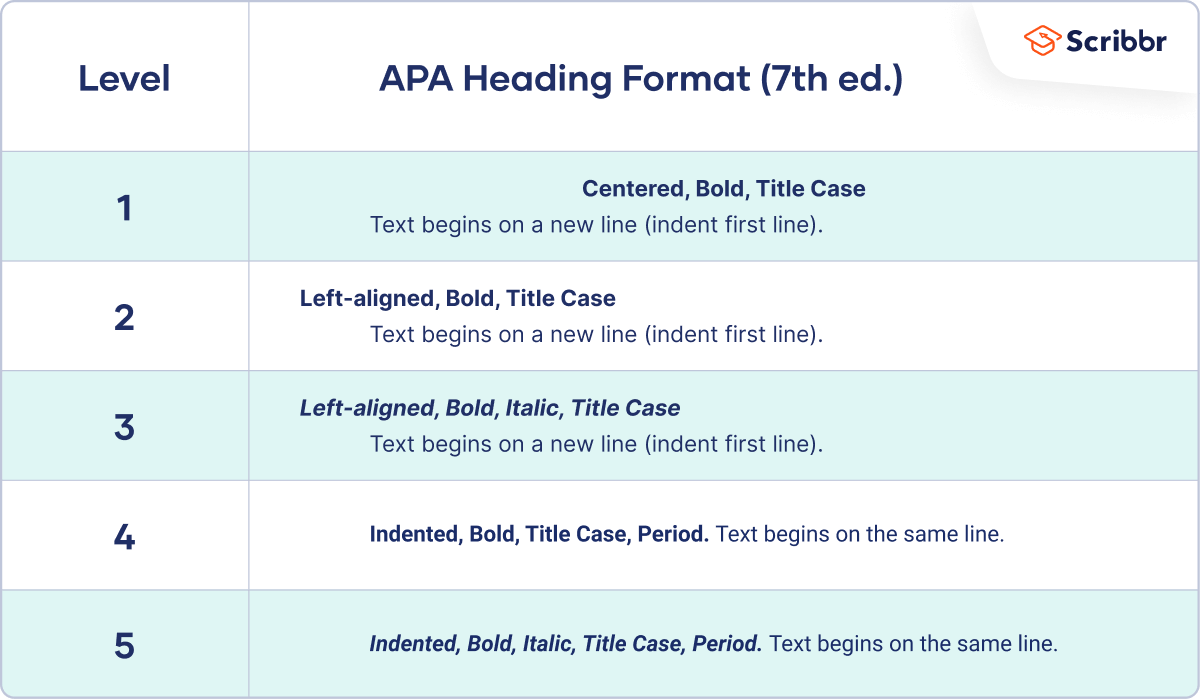

- Level 1 headings, including appendix titles, are centred. Level 2 and Level 3 headings are left aligned..

- Table and figure captions, notes etc. are flush left.

Page numbers:

Page numbers should be flush right in the header of each page. Use the automatic page numbering function in Word to insert page numbers in the top right-hand corner. The title page is page number 1.

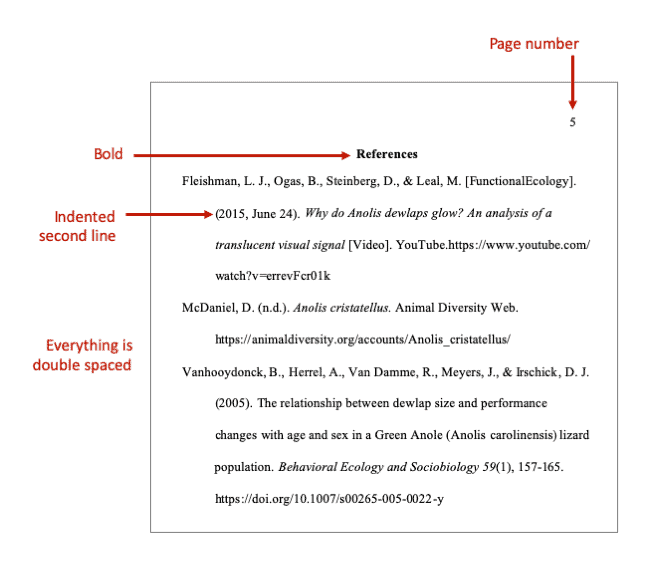

Reference List:

- Start the reference list on a new page after the text but before any appendices.

- Label the reference list References (bold, centred, capitalised).

- Double-space all references.

- Use a hanging indent on all references (first line is flush left, the second and any subsequent lines are indented 1.27 cm (0.5 in). To apply a hanging indent in Word, highlight all of your references and press Ctrl + T on a PC, or Command (⌘) + T on a Mac.

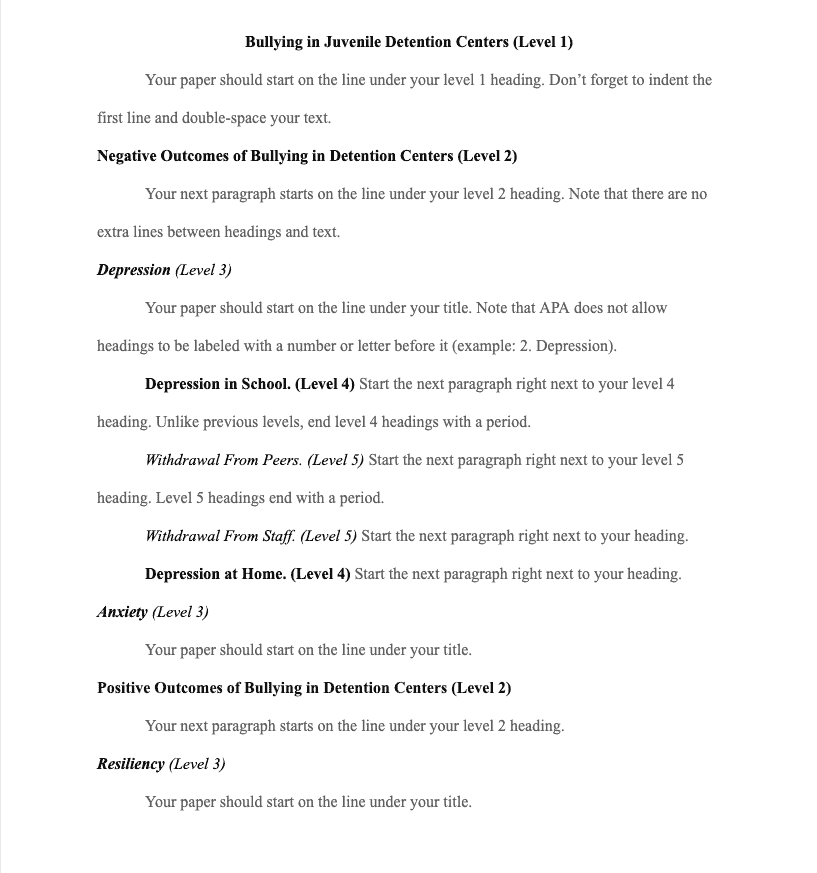

Level 1 Heading - Centered, Bold, Title Case

Text begins as a new paragraph i.e. first line indented...

Level 2 Heading - Flush Left, Bold, Title Case

Level 3 Heading - Flush Left, Bold, Italic, Title Case

Level 4 Heading Indented, Bold, Title Case Heading, Ending With a Full Stop. Text begins on the same line...

Level 5 Heading, Bold, Italic, Title Case Heading, Ending with a Full Stop. Text begins on the same line...

Please note : Any formatting requirements specified in the subject outline or any other document or web page supplied to the students by the lecturers should be followed instead of these guidelines.

What is an appendix?

Appendices contain matter that belongs with your paper, rather than in it.

For example, an appendix might contain

- the survey questions or scales you used for your research,

- detailed description of data that was referred to in your paper,

- long lists that are too unweildy to be given in the paper,

- correspondence recieved from the company you are analysing,

- copies of documents being discussed (if required),

You may be asked to include certain details or documents in appendices, or you may chose to use an appendix to illustrate details that would be inappropriate or distracting in the body of your text, but are still worth presenting to the readers of your paper.

Each topic should have its own appendix. For example, if you have a survey that you gave to participants and an assessment tool which was used to analyse the results of that survey, they should be in different appendices. However, if you are including a number of responses to that survey, do not put each response in a separate appendix, but group them together in one appendix as they belong together.

How do you format an appendix?

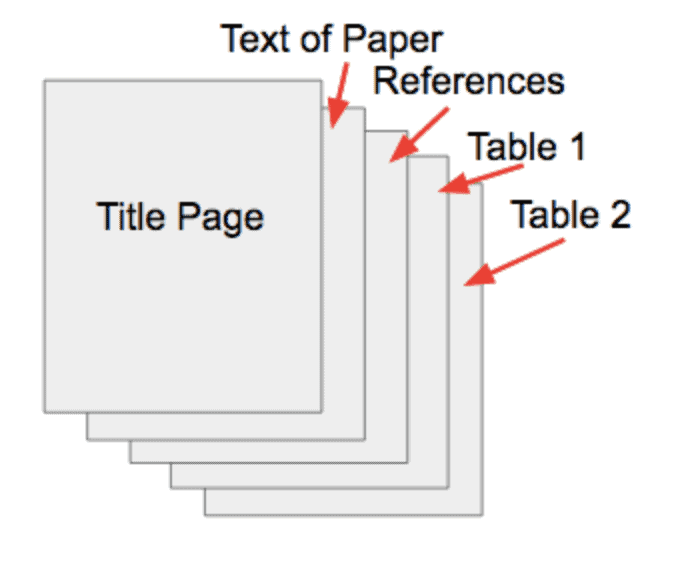

Appendices go at the very end of your paper , after your reference list. (If you are using footnotes, tables or figures, then the end of your paper will follow this pattern: reference list, footnotes, tables, figures, appendices).

Each appendix starts on a separate page. If you have only one appendix, it is simply labelled "Appendix". If you have more than one, they are given letters: "Appendix A", "Appendix B", "Appendix C", etc.

The label for your appendix (which is just "Appendix" or "Appendix A" - do not put anything else with it), like your refrerence list, is placed at the top of the page, centered and in bold , beginning with a capital letter.

You then give a title for your appendix, centered and in bold , on the next line.

Use title case for the appendix label and title.

The first paragraph of your appendix is not indented (it is flush with the left margin), but all other paragraphs follow the normal pattern of indenting the first line. Use double line spacing, just like you would for the body of your paper.

How do I refer to my appendices in my paper?

In your paper, when you mention information that will be included or expanded upon in your appendices, you refer to the appendix by its label and capitalise the letters that are capitalised in the label:

Questions in the survey were designed to illicit reflective responses (see Appendix A).

As the consent form in Appendix B illustrates...

How do I use references in my appendices?

Appendices are considered to be part of your paper for the purpose of referencing. Any in-text citations used in your appendix should be formatted exactly the same way you would format it in the body of your paper, and the references cited in your appendices will go in your reference list (they do not go in a special section of your reference list, but are treated like normal references).

If you have included reproduced matter in your appendices, treat them like an image or a table that has been copied or adapted. Place the information for the source in the notes under the reproduced matter (a full copyright acknowledgement for theses or works being published, or the shorter version used at JCU for assignments), and put the reference in the reference list.

- Thesis Formatting Guide Our Library Guide offers some advice on formatting a thesis for JCU higher degrees.

- Setting up a table in APA 7th

- Setting up a figure in APA 7th

If you are required to include an acknowledgement or disclaimer (for example, a statement of whether any part of your assignment was generated by AI, or if any part of your assignment was re-used, with permission, from a previous assignment), this should go in an author note .

The author note is placed on the bottom half of the title page, so if you are using an author note, you will need to use a title page. Place the section title Author Note in centre and in bold. Align the paragraph text as per a normal paragraph, beginning with an indent. See the second image on this page for an example of where to place the author note: Title Page Setup .

The APA Publication Manual lists several paragraphs that could be included in an author note, and specifies the order in which they should appear. For a student assignment, you will probably only require a paragraph or sentence on disclosures and acknowledgements.

An example author note for a student paper could be:

Author Note

This paper was prepared using Bing Copilot to assist with research and ChatGPT to assist with formatting the reference list. No generative AI software was used to create any part of the submitted text.

No generative AI software was used to create any part of this assignment.

- If the use of generative AI was permitted for drafting or developing parts of your assignment, you will need to include a description in the methodology section of your paper specifying what software was used, what it was used for and to what extent.

- If your subject outline has a specific disclaimer to use, use that wording in your author's note.

- If the use of generative AI software is permitted, you will still need to review the material produced by the software for suitability and accuracy, as the author of the paper is ultimately responsible for all of the content.

- << Previous: AI software

- Next: What If...? >>

- Last Updated: Jun 19, 2024 2:43 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jcu.edu.au/apa

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / APA Format

APA Format for Students & Researchers

In this guide, students and researchers can learn the basics of creating a properly formatted research paper according to APA guidelines.

It includes information on how to conceptualize, outline, and format the basic structure of your paper, as well as practical tips on spelling, abbreviation, punctuation, and more. The guide concludes with a complete sample paper as well as a final checklist that writers can use to prepare their work for submission.

APA Paper Formatting Basics

- All text should be double-spaced

- Use one-inch margins on all sides

- All paragraphs in the body are indented

- Make sure that the title is centered on the page with your name and school/institution underneath

- Use 12-point font throughout

- All pages should be numbered in the upper right hand corner

- The manual recommends using one space after most punctuation marks

- A shortened version of the title (“running head”) should be placed in the upper left hand corner

Table of Contents

Here’s a quick rundown of the contents of this guide on how to do APA format.

Information related to writing and organizing your paper:

- Paper and essay categories

General paper length

- Margin sizes

- Title pages

- Running Heads

- APA Outline

- APA Abstract

- The body of papers

- APA headings and subheadings

- Use of graphics (tables and figures)

Writing style tips:

Proper tone.

- Reducing bias and labels

- Abbreviation do’s and don’ts

- Punctuation

- Number rules

Citing Your Sources:

- Citing Sources

- In-text Citations

- Reference Page

Proofing Your Paper:

- Final checklist

- Submitting your project

APA Information:

- What is APA

- APA 7 Updates

What you won’t find in this guide: This guide provides information related to the formatting of your paper, as in guidelines related to spacing, margins, word choice, etc. While it provides a general overview of APA references, it does not provide instructions for how to cite in APA format.

For step-by-step instructions for citing books, journals, how to cite a website in APA format, information on an APA format bibliography, and more, refer to these other EasyBib guides:

- APA citation (general reference guide)

- APA In-text citation

- APA article citation

- APA book citation

- APA citation website

Or, you can use our automatic generator. Our APA formatter helps to build your references for you. Yep, you read that correctly.

Writing and Organizing Your APA Paper in an Effective Way

This section of our guide focuses on proper paper length, how to format headings, spacing, and more! This information can be found in Chapter 2 of the official manual (American Psychological Association, 2020, pp. 29-67).

Categories of papers

Before getting into the nitty-gritty details related to APA research paper format, first determine the type of paper you’re about to embark on creating:

Empirical studies

Empirical studies take data from observations and experiments to generate research reports. It is different from other types of studies in that it isn’t based on theories or ideas, but on actual data.

Literature reviews

These papers analyze another individual’s work or a group of works. The purpose is to gather information about a current issue or problem and to communicate where we are today. It sheds light on issues and attempts to fill those gaps with suggestions for future research and methods.

Theoretical articles

These papers are somewhat similar to a literature reviews in that the author collects, examines, and shares information about a current issue or problem, by using others’ research. It is different from literature reviews in that it attempts to explain or solve a problem by coming up with a new theory. This theory is justified with valid evidence.

Methodological articles

These articles showcase new advances, or modifications to an existing practice, in a scientific method or procedure. The author has data or documentation to prove that their new method, or improvement to a method, is valid. Plenty of evidence is included in this type of article. In addition, the author explains the current method being used in addition to their own findings, in order to allow the reader to understand and modify their own current practices.

Case studies

Case studies present information related an individual, group, or larger set of individuals. These subjects are analyzed for a specific reason and the author reports on the method and conclusions from their study. The author may also make suggestions for future research, create possible theories, and/or determine a solution to a problem.

Since APA style format is used often in science fields, the belief is “less is more.” Make sure you’re able to get your points across in a clear and brief way. Be direct, clear, and professional. Try not to add fluff and unnecessary details into your paper or writing. This will keep the paper length shorter and more concise.

Margin sizes in APA Format

When it comes to margins, keep them consistent across the left, right, top, and bottom of the page. All four sides should be the same distance from the edge of the paper. It’s recommended to use at least one-inch margins around each side. It’s acceptable to use larger margins, but the margins should never be smaller than an inch.

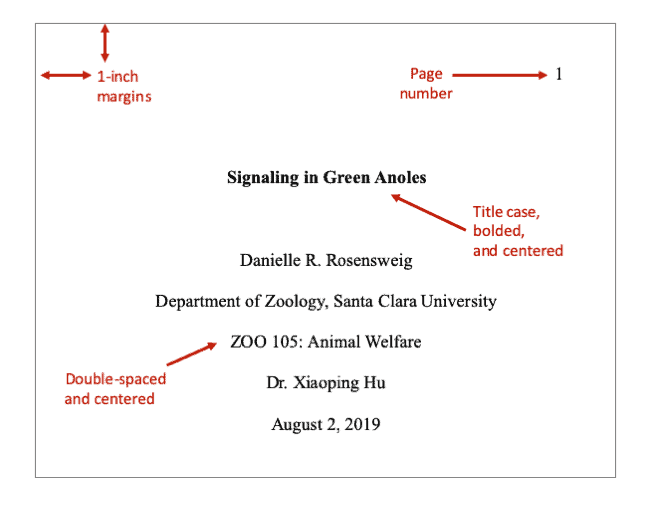

Title pages in APA Format

The title page, or APA format cover page, is the first page of a paper or essay. Some teachers and professors do not require a title page, but some do. If you’re not sure if you should include one or not, ask your teacher. Some appreciate the page, which clearly displays the writer’s name and the title of the paper.

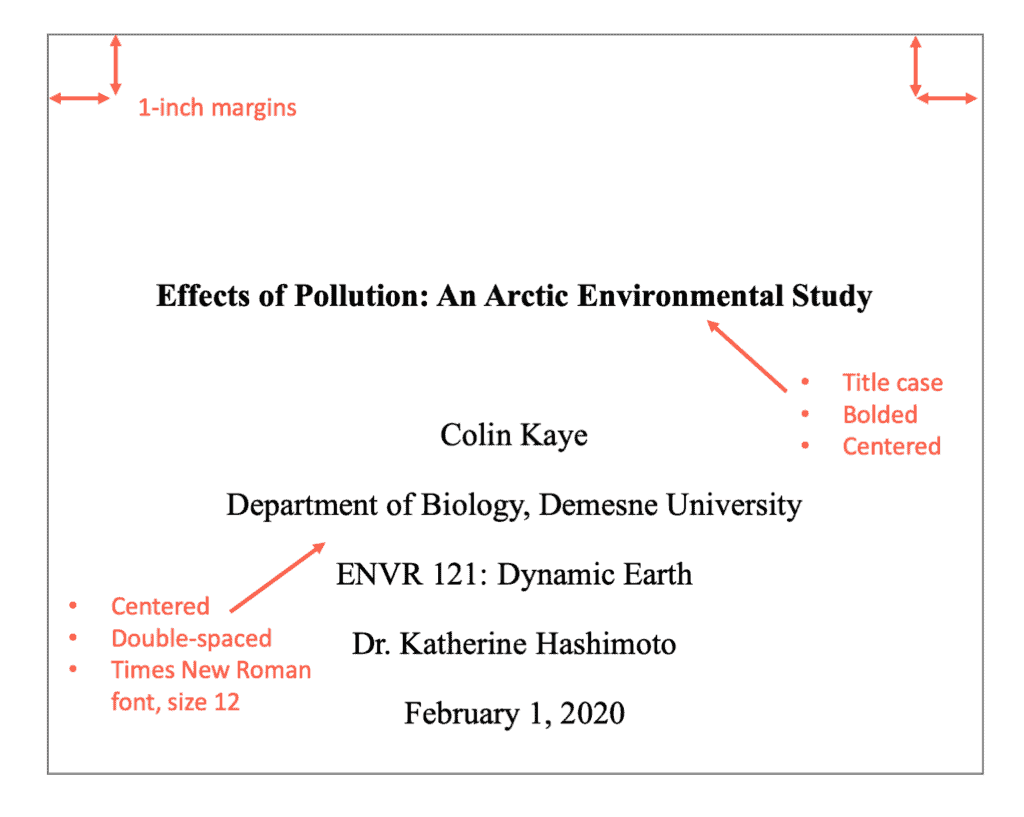

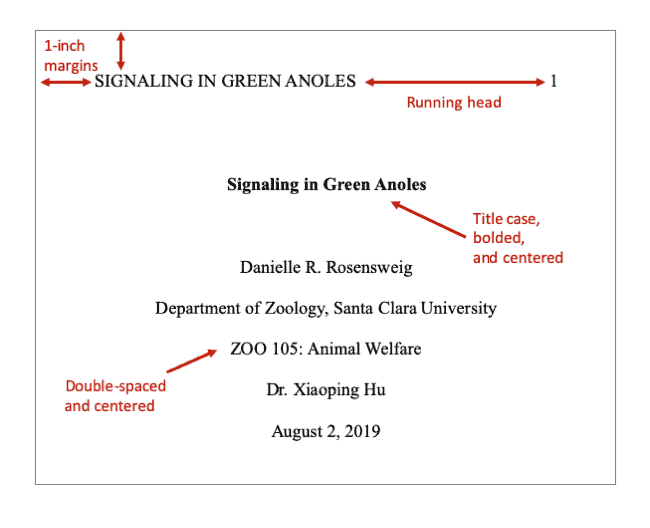

The APA format title page for student papers includes six main components:

- the title of the APA format paper

- names of all authors

- institutional affiliation

- course number and title

- instructor’s name

Title pages for professional papers also require a running head; student papers do not.

Some instructors and professional publications also ask for an author’s note. If you’re required or would like to include an author’s note, place it below the institutional affiliation. Examples of information included in an author’s note include an ORCID iD number, a disclosure, and an acknowledgement.

Here are key guidelines to developing your title page:

- The title of the paper should capture the main idea of the essay, but should not contain abbreviations or words that serve no purpose. For example, instead of using the title “A Look at Amphibians From the Past,” title the paper “Amphibians From the Past.” Delete the unnecessary fluff!

- Center the title on the page and place it about 3-4 lines from the top.

- The title should be bolded, in title case, and the same font size as your other page text. Do not underline or italicize the title. Other text on the page should be plain (not bolded , underlined, or italicized ).

- All text on the title page should be double-spaced. The APA format examples paper below displays proper spacing, so go take a look!

- Do not include any titles in the author’s name such as Dr. or Ms. In contrast, for your instructor’s name, use the form they prefer (e.g., Sagar Parekh, PhD; Dr. Minako Asato; Professor Nathan Ian Brown; etc.).

- The institutional affiliation is the school the author attends or the location where the author conducted the research.

In a hurry? Try the EasyBib title page maker to easily create a title page for free.

Sample of an APA format title page for a student paper:

Sample of title page for a professional paper:

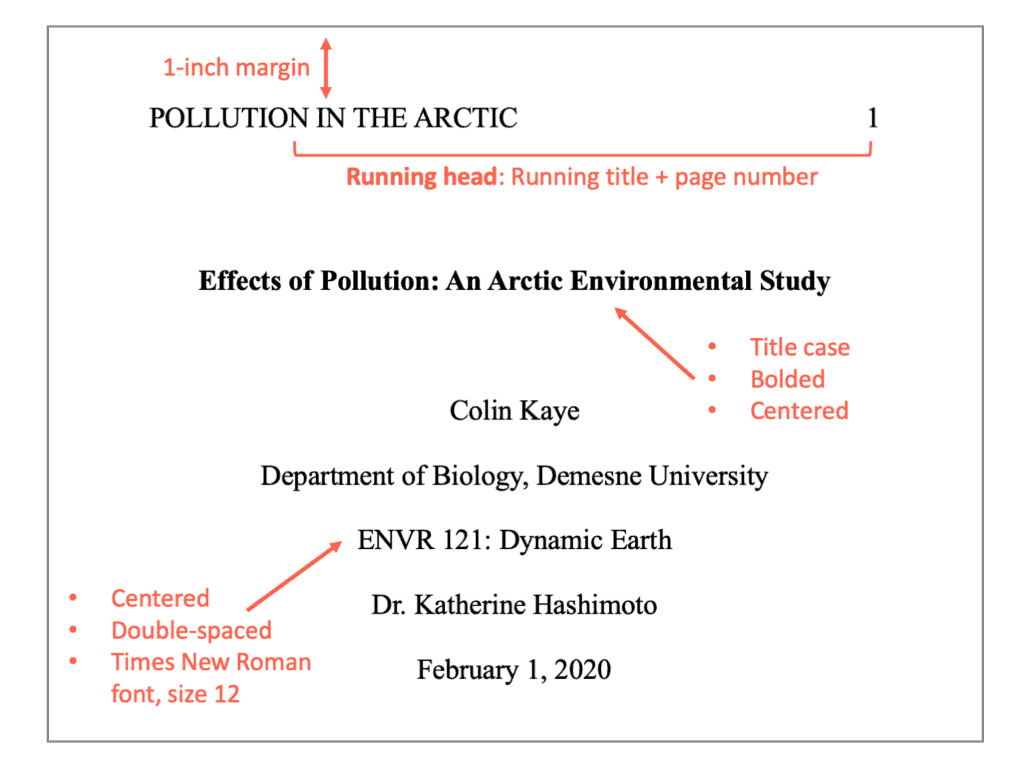

Running heads in APA Format

The 7th edition of the American Psychological Association Publication Manual (p. 37) states that running heads are not required for student papers unless requested by the instructor. Student papers still need a page number included in the upper right-hand corner of every page. The 6th edition required a running head for student papers, so be sure to confirm with your instructor which edition you should follow. Of note, this guide follows the 7th edition.

Running heads are required for professional papers (e.g., manuscripts submitted for publication). Read on for instructions on how to create them.

Are you wondering what is a “running head”? It’s basically a page header at the top of every page. To make this process easier, set your word processor to automatically add these components onto each page. You may want to look for “Header” in the features.

A running head/page header includes two pieces:

- the title of the paper

- page numbers.

Insert page numbers justified to the right-hand side of the APA format paper (do not put p. or pg. in front of the page numbers).

For all pages of the paper, including the APA format title page, include the “TITLE OF YOUR PAPER” justified to the left in capital letters (i.e., the running head). If your full title is long (over 50 characters), the running head title should be a shortened version.

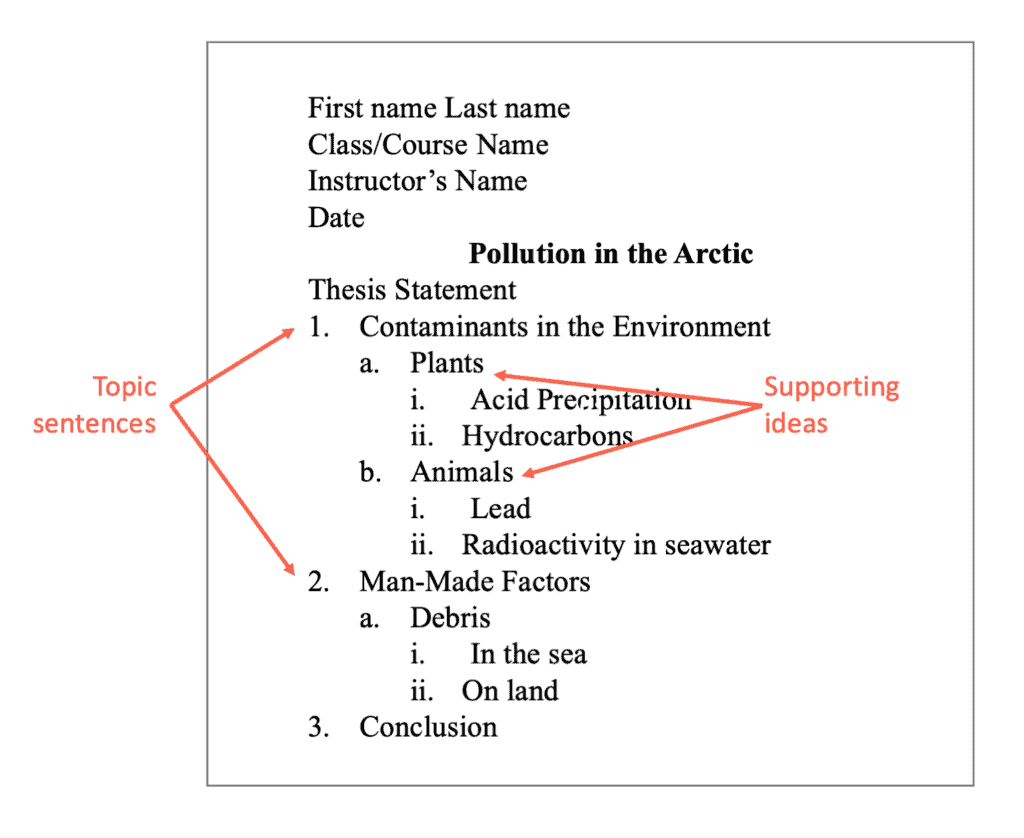

Preparing outlines in APA Format

Outlines are extremely beneficial as they help writers stay organized, determine the scope of the research that needs to be included, and establish headings and subheadings.

There isn’t an official or recommended “APA format for outline” structure. It is up to the writer (if they choose to make use of an outline) to determine how to organize it and the characters to include. Some writers use a mix of roman numerals, numbers, and uppercase and lowercase letters.

Even though there isn’t a required or recommended APA format for an outline, we encourage writers to make use of one. Who wouldn’t want to put together a rough outline of their project? We promise you, an outline will help you stay on track.

Here’s our version of how APA format for outlines could look:

Don’t forget, if you’re looking for information on APA citation format and other related topics, check out our other comprehensive guides.

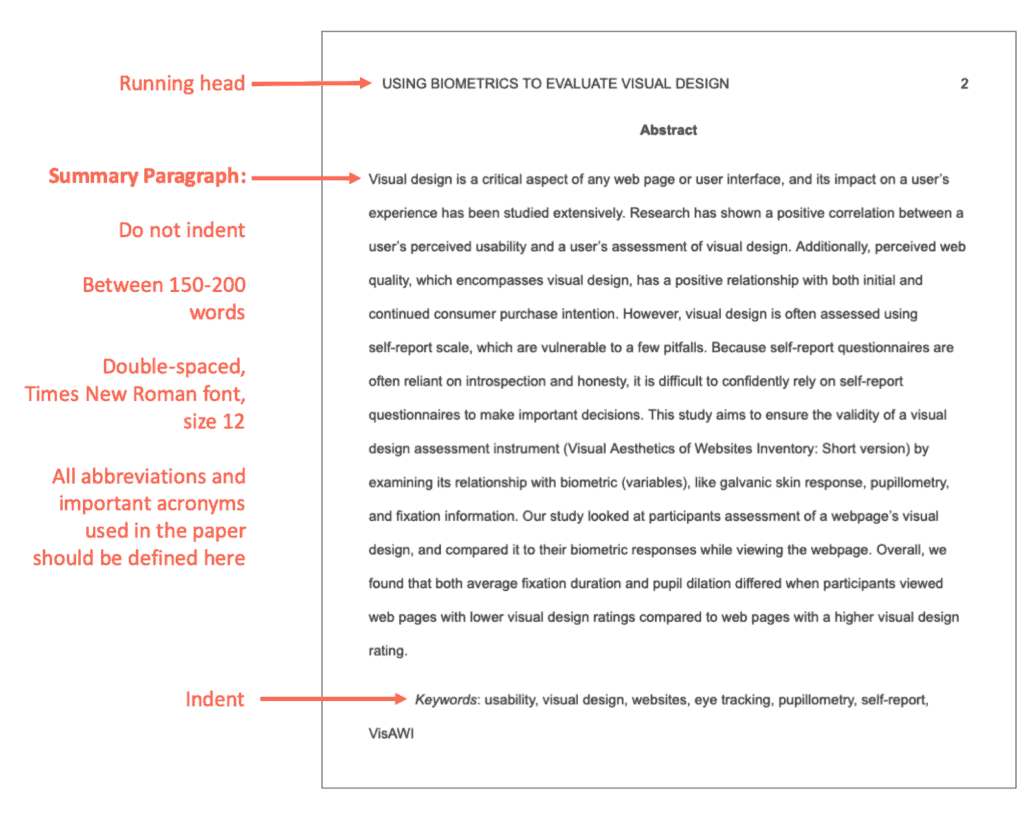

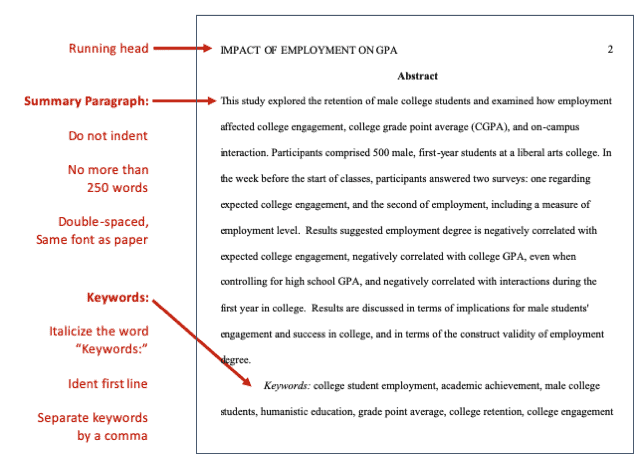

How to form an abstract in APA

An APA format abstract (p. 38) is a summary of a scholarly article or scientific study. Scholarly articles and studies are rather lengthy documents, and abstracts allow readers to first determine if they’d like to read an article in its entirety or not.

You may come across abstracts while researching a topic. Many databases display abstracts in the search results and often display them before showing the full text of an article or scientific study. It is important to create a high quality abstract that accurately communicates the purpose and goal of your paper, as readers will determine if it is worthy to continue reading or not.

Are you wondering if you need to create an abstract for your assignment? Usually, student papers do not require an abstract. Abstracts are not typically seen in class assignments, and are usually only included when submitting a paper for publication. Unless your teacher or professor asked for it, you probably don’t need to have one for your class assignment.

If you’re planning on submitting your paper to a journal for publication, first check the journal’s website to learn about abstract and APA paper format requirements.

Here are some helpful suggestions to create a dynamic abstract:

- Abstracts are found on their own page, directly after the title or cover page.

- Professional papers only (not student papers): Include the running head on the top of the page.

- On the first line of the page, center the word “Abstract” (but do not include quotation marks).

- On the following line, write a summary of the key points of your research. Your abstract summary is a way to introduce readers to your research topic, the questions that will be answered, the process you took, and any findings or conclusions you drew. Use concise, brief, informative language. You only have a few sentences to share the summary of your entire document, so be direct with your wording.

- This summary should not be indented, but should be double-spaced and less than 250 words.

- If applicable, help researchers find your work in databases by listing keywords from your paper after your summary. To do this, indent and type Keywords : in italics. Then list your keywords that stand out in your research. You can also include keyword strings that you think readers will type into the search box.

- Active voice: The subjects reacted to the medication.

- Passive voice: There was a reaction from the subjects taking the medication.

- Instead of evaluating your project in the abstract, simply report what it contains.

- If a large portion of your work includes the extension of someone else’s research, share this in the abstract and include the author’s last name and the year their work was released.

APA format example page:

Here’s an example of an abstract:

Visual design is a critical aspect of any web page or user interface, and its impact on a user’s experience has been studied extensively. Research has shown a positive correlation between a user’s perceived usability and a user’s assessment of visual design. Additionally, perceived web quality, which encompasses visual design, has a positive relationship with both initial and continued consumer purchase intention. However, visual design is often assessed using self-report scale, which are vulnerable to a few pitfalls. Because self-report questionnaires are often reliant on introspection and honesty, it is difficult to confidently rely on self-report questionnaires to make important decisions. This study aims to ensure the validity of a visual design assessment instrument (Visual Aesthetics of Websites Inventory: Short version) by examining its relationship with biometric (variables), like galvanic skin response, pupillometry, and fixation information. Our study looked at participants assessment of a webpage’s visual design, and compared it to their biometric responses while viewing the webpage. Overall, we found that both average fixation duration and pupil dilation differed when participants viewed web pages with lower visual design ratings compared to web pages with a higher visual design rating.

Keywords : usability, visual design, websites, eye tracking, pupillometry, self-report, VisAWI

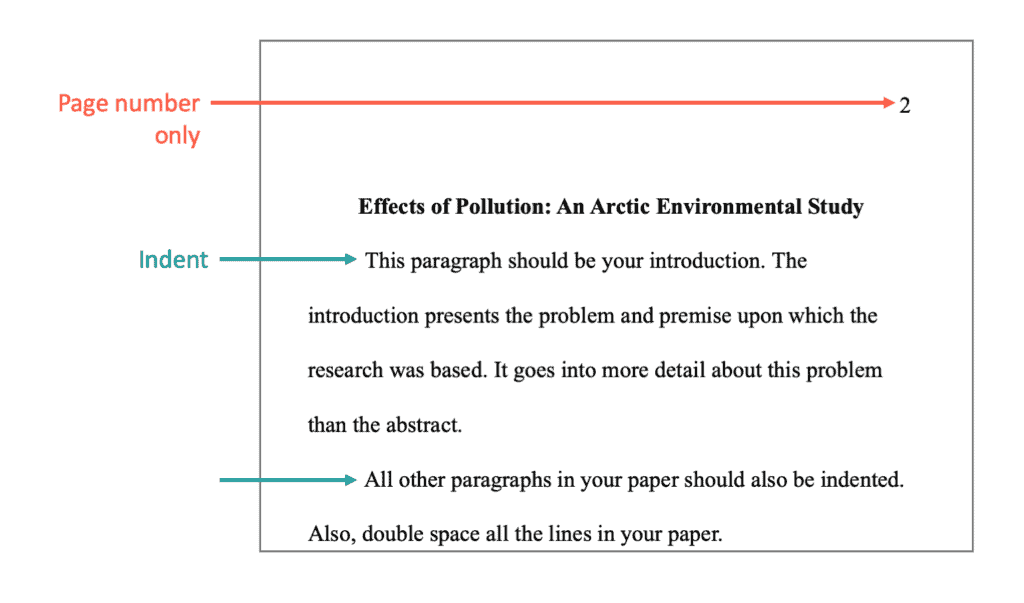

The body of an APA paper

On the page after the title page (if a student paper) or the abstract (if a professional paper), begin with the body of the paper.

Most papers follow this format:

- At the top of the page, add the page number in the upper right corner of all pages, including the title page.

- On the next line write the title in bold font and center it. Do not underline or italicize it.

- Begin with the introduction and indent the first line of the paragraph. All paragraphs in the body are indented.

Sample body for a student paper:

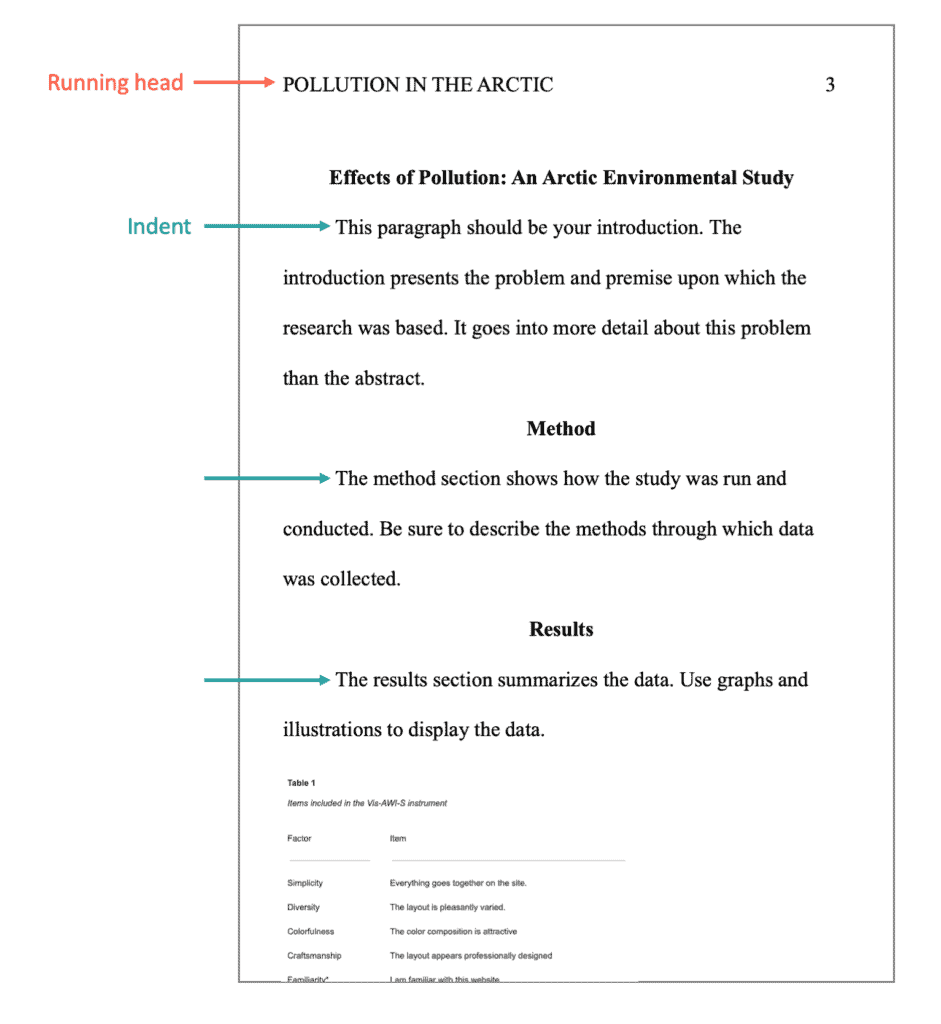

Most scientific or professional papers have additional sections and guidelines:

- Start with the running head (title + page number). The heading title should be in capital letters. The abstract page should be page 2.

- The introduction presents the problem and premise upon which the research was based. It goes into more detail about this problem than the abstract.

- Begin a new section with the Method and use this word as the subtitle. Bold and center this subtitle. The Method section shows how the study was run and conducted. Be sure to describe the methods through which data was collected.

- Begin a new section with the Results . Bold and center this subtitle. The Results section summarizes your data. Use charts and graphs to display this data.

- Draw conclusions and support how your data led to these conclusions.

- Discuss whether or not your hypothesis was confirmed or not supported by your results.

- Determine the limitations of the study and next steps to improve research for future studies.

Sample body for a professional paper:

Keep in mind, APA citation format is much easier than you think, thanks to EasyBib.com. Try our automatic generator and watch how we create APA citation format references for you in just a few clicks. While you’re at it, take a peek at our other helpful guides, such as our APA reference page guide, to make sure you’re on track with your research papers.

Proper usage of headings & subheadings in APA Format

Headings (p. 47) serve an important purpose in research papers — they organize your paper and make it simple to locate different pieces of information. In addition, headings provide readers with a glimpse to the main idea, or content, they are about to read.

In APA format, there are five levels of headings, each with a different formatting:

- This is the title of your paper

- The title should be centered in the middle of the page

- The title should be bolded

- Use uppercase and lowercase letters where necessary (called title capitalization)

- Place this heading against the left margin

- Use bold letters

- Use uppercase and lowercase letters where necessary

- Place this heading against the left side margin

- End the heading with a period

- Indented in from the left margin

Following general formatting rules, all headings are double spaced and there are no extra lines or spaces between sections.

Here is a visual APA format template for levels of headings:

Use of graphics (tables and figures) in APA Format

If you’re looking to jazz up your project with any charts, tables, drawings, or images, there are certain APA format rules (pp. 195-250) to follow.

First and foremost, the only reason why any graphics should be added is to provide the reader with an easier way to see or read information, rather than typing it all out in the text.

Lots of numbers to discuss? Try organizing your information into a chart or table. Pie charts, bar graphs, coordinate planes, and line graphs are just a few ways to show numerical data, relationships between numbers, and many other types of information.

Instead of typing out long, drawn out descriptions, create a drawing or image. Many visual learners would appreciate the ability to look at an image to make sense of information.

Before you go ahead and place that graphic in your paper, here are a few key guidelines:

- Follow them in the appropriate numerical order in which they appear in the text of your paper. Example : Figure 1, Figure 2, Table 1, Figure 3.

- Example: Figure 1, Figure 2, Table 1, Figure 3

- Only use graphics if they will supplement the material in your text. If they reinstate what you already have in your text, then it is not necessary to include a graphic.

- Include enough wording in the graphic so that the reader is able to understand its meaning, even if it is isolated from the corresponding text. However, do not go overboard with adding a ton of wording in your graphic.

- Left align tables and figures

In our APA format sample paper , you’ll find examples of tables after the references. You may also place tables and figures within the text just after it is mentioned.

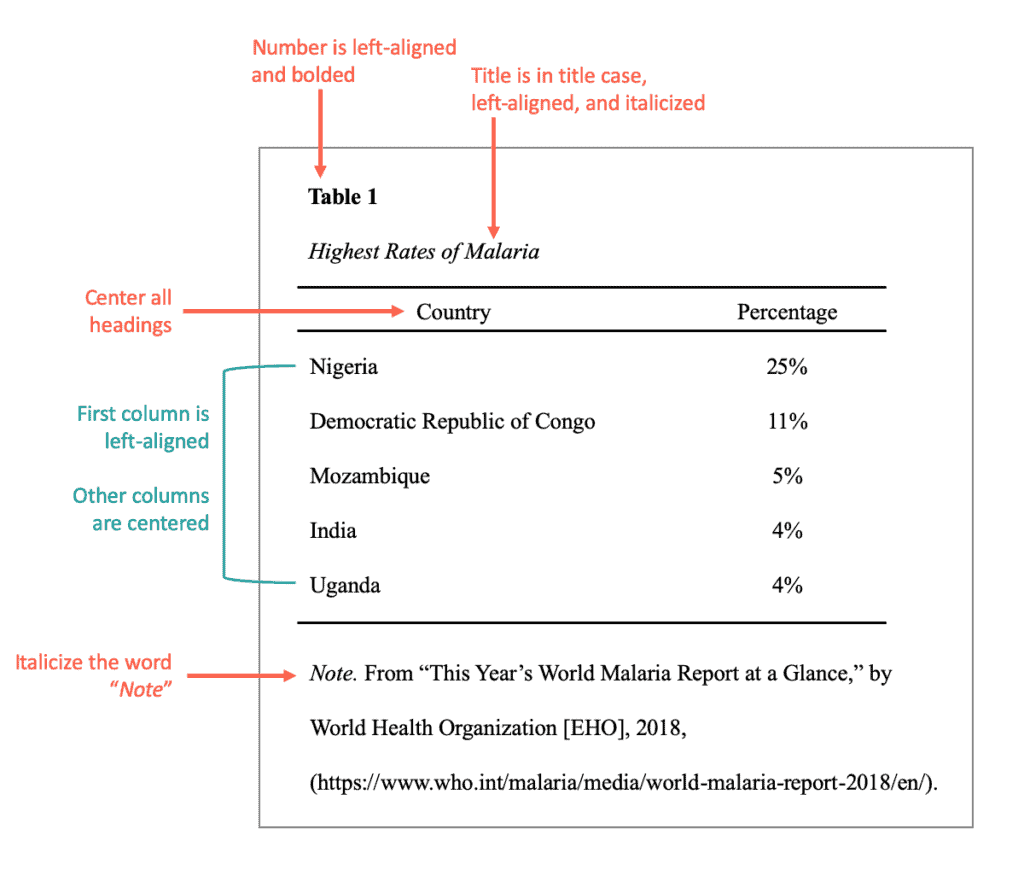

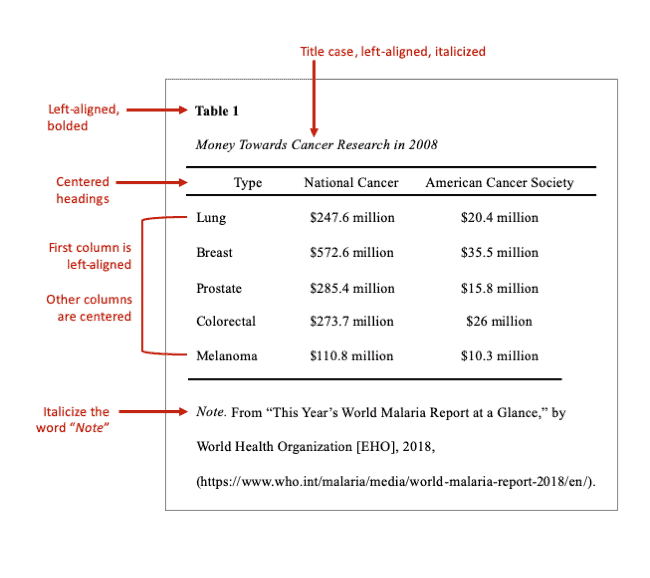

Is there anything better than seeing a neatly organized data table? We think not! If you have tons of numbers or data to share, consider creating a table instead of typing out a wordy paragraph. Tables are pretty easy to whip up on Google Docs or Microsoft Word.

General format of a table should be:

- Table number

- Choose to type out your data OR create a table. As stated above, in APA format, you shouldn’t have the information typed out in your paper and also have a table showing the same exact information. Choose one or the other.

- If you choose to create a table, discuss it very briefly in the text. Say something along the lines of, “Table 1 displays the amount of money used towards fighting Malaria.” Or, “Stomach cancer rates are displayed in Table 4.”

- If you’re submitting your project for a class, place your table close to the text where it’s mentioned. If you’re submitting it to be published in a journal, most publishers prefer tables to be placed in the back. If you’re unsure where to place your tables, ask!

- Include the table number first and at the top. Table 1 is the first table discussed in the paper. Table 2 is the next table mentioned, and so on. This should be in bold.

- Add a title under the number. Create a brief, descriptive title. Capitalize the first letter for each important word. Italicize the title and place it under the table number.

- Only use horizontal lines.

- Limit use of cell shading.

- Keep the font at 12-point size and use single or double spacing. If you use single spacing in one table, make sure all of the others use single spaces as well. Keep it consistent.

- All headings should be centered.

- In the first column (called the stub), center the heading, left-align the information underneath it (indent 0.15 inches if info is more than one line).

- Information in other columns should be centered.

- General . Information about the whole table.

- Specific . Information targeted for a specific column, row, or cell.

- Probability . Explains what certain table symbols mean. For example, asterisks, p values, etc.

Here’s an APA format example of a table:

We know putting together a table is pretty tricky. That’s why we’ve included not one, but a few tables on this page. Scroll down and look at the additional tables in the essay in APA format example found below.

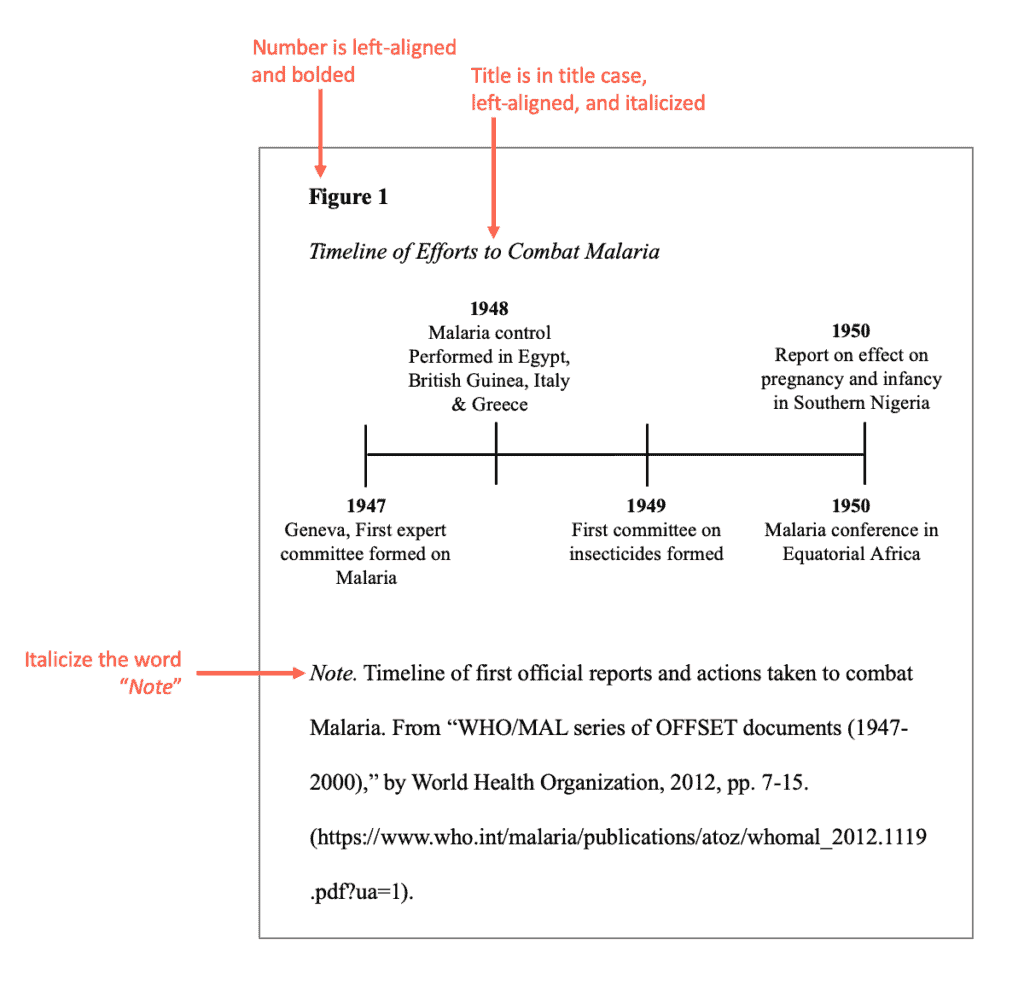

Figures represent information in a visual way. They differ from tables in that they are visually appealing. Sure, tables, like the one above, can be visually appealing, but it’s the color, circles, arrows, boxes, or icons included that make a figure a “figure.”

There are many commonly used figures in papers. Examples APA Format:

- Photographs

- Hierarchy charts

General format of a figure is the same as tables. This means each should include:

- Figure number

Use the same formatting tables use for the number, title, and note.

Here are some pointers to keep in mind when it comes to APA format for figures:

- Only include a figure if it adds value to your paper. If it will truly help with understanding, include it!

- Either include a figure OR write it all out in the text. Do not include the same information twice.

- If a note is added, it should clearly explain the content of the figure. Include any reference information if it’s reproduced or adapted.

APA format sample of a figure:

Photographs:

We live in a world where we have tons of photographs available at our fingertips.

Photographs found through Google Images, social media, stock photos made available from subscription sites, and tons of other various online sources make obtaining photographs a breeze. We can even pull out our cell phones, and in just a few seconds, take pictures with our cameras.

Photographs are simple to find, and because of this, many students enjoy using them in their papers.

If you have a photograph you would like to include in your project, here are some guidelines from the American Psychological Association.

- Create a reference for the photograph. Follow the guidelines under the table and figure sections above.

- Do not use color photos. It is recommended to use black and white. Colors can change depending on the reader’s screen resolution. Using black and white ensures the reader will be able to view the image clearly. The only time it is recommended to use color photos is if you’re writing about color-specific things. For example, if you’re discussing the various shades of leaf coloration, you may want to include a few photographs of colorful leaves.

- If there are sections of the photograph that are not related to your work, it is acceptable to crop them out. Cropping is also beneficial in that it helps the reader focus on the main item you’re discussing.

- If you choose to include an image of a person you know, it would be respectful if you ask their permission before automatically including their photo in your paper. Some schools and universities post research papers online and some people prefer that their photos and information stay off the Internet.

B. Writing Style Tips

Writing a paper for scientific topics is much different than writing for English, literature, and other composition classes. Science papers are much more direct, clear, and concise. This section includes key suggestions, explains how to write in APA format, and includes other tidbits to keep in mind while formulating your research paper.

Verb usage in APA

Research experiments and observations rely on the creation and analysis of data to test hypotheses and come to conclusions. While sharing and explaining the methods and results of studies, science writers often use verbs.

When using verbs in writing, make sure that you continue to use them in the same tense throughout the section you’re writing. Further details are in the publication manual (p. 117).

Here’s an APA format example:

We tested the solution to identify the possible contaminants.

It wouldn’t make sense to add this sentence after the one above:

We tested the solution to identify the possible contaminants. Researchers often test solutions by placing them under a microscope.

Notice that the first sentence is in the past tense while the second sentence is in the present tense. This can be confusing for readers.

For verbs in scientific papers, the APA manual recommends using:

- Past tense or present perfect tense for the explantation of the procedure

- Past tense for the explanation of the results

- Present tense for the explanation of the conclusion and future implications

If this is all a bit much, and you’re simply looking for help with your references, try the EasyBib.com APA format generator . Our APA formatter creates your references in just a few clicks. APA citation format is easier than you think thanks to our innovative, automatic tool.

Even though your writing will not have the same fluff and detail as other forms of writing, it should not be boring or dull to read. The Publication Manual suggests thinking about who will be the main reader of your work and to write in a way that educates them.

How to reduce bias & labels

The American Psychological Association strongly objects to any bias towards gender, racial groups, ages of individuals or subjects, disabilities, and sexual orientation (pp. 131-149). If you’re unsure whether your writing is free of bias and labels or not, have a few individuals read your work to determine if it’s acceptable.

Here are a few guidelines that the American Psychological Association suggests :

- Only include information about an individual’s orientation or characteristic if it is important to the topic or study. Do not include information about individuals or labels if it is not necessary.

- If writing about an individual’s characteristic or orientation, for essay APA format, make sure to put the person first. Instead of saying, “Diabetic patients,” say, “Patients who are diabetic.”

- Instead of using narrow terms such as, “adolescents,” or “the elderly,” try to use broader terms such as, “participants,” and “subjects.”

- “They” or “their” are acceptable gender-neutral pronouns to use.

- Be mindful when using terms that end with “man” or “men” if they involve subjects who are female. For example, instead of using “Firemen,” use the term, “Firefighter.” In general, avoid ambiguity.

- When referring to someone’s racial or ethnic identity, use the census category terms and capitalize the first letter. Also, avoid using the word, “minority,” as it can be interpreted as meaning less than or deficient. Instead, say “people of color” or “underrepresented groups.”

- When describing subjects in APA format, use the words “girls” and “boys” for children who are under the age of 12. The terms, “young woman,” “young man,” “female adolescent,” and “male adolescent” are appropriate for subjects between 13-17 years old; “Men,” and “women,” for those older than 18. Use the term, “older adults.” for individuals who are older. “Elderly,” and “senior,” are not acceptable if used only as nouns. It is acceptable to use these terms if they’re used as adjectives.

Read through our example essay in APA format, found in section D, to see how we’ve reduced bias and labels.

Spelling in APA Format

- In APA formatting, use the same spelling as words found in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (American English) (p. 161).

- If the word you’re trying to spell is not found in Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, a second resource is Webster’s Third New International Dictionary .

- If attempting to properly spell words in the psychology field, consult the American Psychological Association’s Dictionary of Psychology

Thanks to helpful tools and features, such as the spell checker, in word processing programs, most of us think we have everything we need right in our document. However, quite a few helpful features are found elsewhere.

Where can you find a full grammar editor? Right here, on EasyBib.com. The EasyBib Plus paper checker scans your paper for spelling, but also for any conjunction , determiner, or adverb out of place. Try it out and unlock the magic of an edited paper.

Abbreviation do’s and don’ts in APA Format

Abbreviations can be tricky. You may be asking yourself, “Do I include periods between the letters?” “Are all letters capitalized?” “Do I need to write out the full name each and every time?” Not to worry, we’re breaking down the publication manual’s abbreviations (p. 172) for you here.

First and foremost, use abbreviations sparingly.

Too many and you’re left with a paper littered with capital letters mashed together. Plus, they don’t lend themselves to smooth and easy reading. Readers need to pause and comprehend the meaning of abbreviations and quite often stumble over them.

- If the abbreviation is used less than three times in the paper, type it out each time. It would be pretty difficult to remember what an abbreviation or acronym stands for if you’re writing a lengthy paper.

- If you decide to sprinkle in abbreviations, it is not necessary to include periods between the letters.

- Example: While it may not affect a patient’s short-term memory (STM), it may affect their ability to comprehend new terms. Patients who experience STM loss while using the medication should discuss it with their doctor.

- Example : AIDS

- The weight in pounds exceeded what we previously thought.

Punctuation in APA Format

One space after most punctuation marks.

The manual recommends using one space after most punctuation marks, including punctuation at the end of a sentence (p. 154). It doesn’t hurt to double check with your teacher or professor to ask their preference since this rule was changed recently (in 2020).

The official APA format book was primarily created to aid individuals with submitting their paper for publication in a professional journal. Many schools adopt certain parts of the handbook and modify sections to match their preference. To see an example of an APA format research paper, with the spacing we believe is most commonly and acceptable to use, scroll down and see section D.

For more information related to the handbook, including frequently asked questions, and more, here’s further reading on the style

It’s often a heated debate among writers whether or not to use an Oxford comma (p. 155), but for this style, always use an Oxford comma. This type of comma is placed before the words AND and OR or in a series of three items.

Example of APA format for commas: The medication caused drowsiness, upset stomach, and fatigue.

Here’s another example: The subjects chose between cold, room temperature, or warm water.

Apostrophes

When writing a possessive singular noun, you should place the apostrophe before the s. For possessive plural nouns, the apostrophe is placed after the s.

- Singular : Linda Morris’s jacket

- Plural : The Morris’ house

Em dashes (long dash) are used to bring focus to a particular point or an aside. There are no spaces after these dashes (p. 157).

Use en dashes (short dash) in compound adjectives. Do not place a space before or after the dash. Here are a few examples:

- custom-built

- 12-year-old

Number rules in APA Format

Science papers often include the use of numbers, usually displayed in data, tables, and experiment information. The golden rule to keep in mind is that numbers less than 10 are written out in text. If the number is more than 10, use numerals.

APA format examples:

- 14 kilograms

- seven individuals

- 83 years old

- Fourth grade

The golden rule for numbers has exceptions.

In APA formatting, use numerals if you are:

- Showing numbers in a table or graph

- 4 divided by 2

- 6-month-olds

Use numbers written out as words if you are:

- Ninety-two percent of teachers feel as though….

- Hundred Years’ War

- One-sixth of the students

Other APA formatting number rules to keep in mind:

- World War II

- Super Bowl LII

- It’s 1980s, not 1980’s!

Additional number rules can be found in the publication manual (p. 178)

Need help with other writing topics? Our plagiarism checker is a great resource for anyone looking for writing help. Say goodbye to an out of place noun , preposition , or adjective, and hello to a fully edited paper.

Overview of APA references

While writing a research paper, it is always important to give credit and cite your sources; this lets you acknowledge others’ ideas and research you’ve used in your own work. Not doing so can be considered plagiarism , possibly leading to a failed grade or loss of a job.

APA style is one of the most commonly used citation styles used to prevent plagiarism. Here’s more on crediting sources . Let’s get this statement out of the way before you become confused: An APA format reference and an APA format citation are two different things! We understand that many teachers and professors use the terms as if they’re synonyms, but according to this specific style, they are two separate things, with different purposes, and styled differently.

A reference displays all of the information about the source — the title, the author’s name, the year it was published, the URL, all of it! References are placed on the final page of a research project.

Here’s an example of a reference:

Wynne-Jones, T. (2015). The emperor of any place . Candlewick Press.

An APA format citation is an APA format in-text citation. These are found within your paper, anytime a quote or paraphrase is included. They usually only include the name of the author and the date the source was published.

Here’s an example of one:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is even discussed in the book, The Emperor of Any Place . The main character, Evan, finds a mysterious diary on his father’s desk (the same desk his father died on, after suffering from a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy attack). Evan unlocks the truth to his father and grandfather’s past (Wynne-Jones, 2015).

Both of the ways to credit another individual’s work — in the text of a paper and also on the final page — are key to preventing plagiarism. A writer must use both types in a paper. If you cite something in the text, it must have a full reference on the final page of the project. Where there is one, there must be the other!

Now that you understand that, here’s some basic info regarding APA format references (pp. 281-309).

- Each reference is organized, or structured, differently. It all depends on the source type. A book reference is structured one way, an APA journal is structured a different way, a newspaper article is another way. Yes, it’s probably frustrating that not all references are created equal and set up the same way. MLA works cited pages are unique in that every source type is formatted the same way. Unfortunately, this style is quite different.

- Most references follow this general format:

Author’s Last name, First initial. Middle initial. (Year published). Title of source . URL.

Again, as stated in the above paragraph, you must look up the specific source type you’re using to find out the placement of the title, author’s name, year published, etc.

For more information on APA format for sources and how to reference specific types of sources, use the other guides on EasyBib.com. Here’s another useful site .

Looking for a full visual of a page of references? Scroll down and take a peek at our APA format essay example towards the bottom of this page. You’ll see a list of references and you can gain a sense of how they look.

Bonus: here’s a link to more about the fundamentals related to this particular style. If you want to brush up or catch up on the Modern Language Association’s style, here’s a great resource on how to cite websites in MLA .

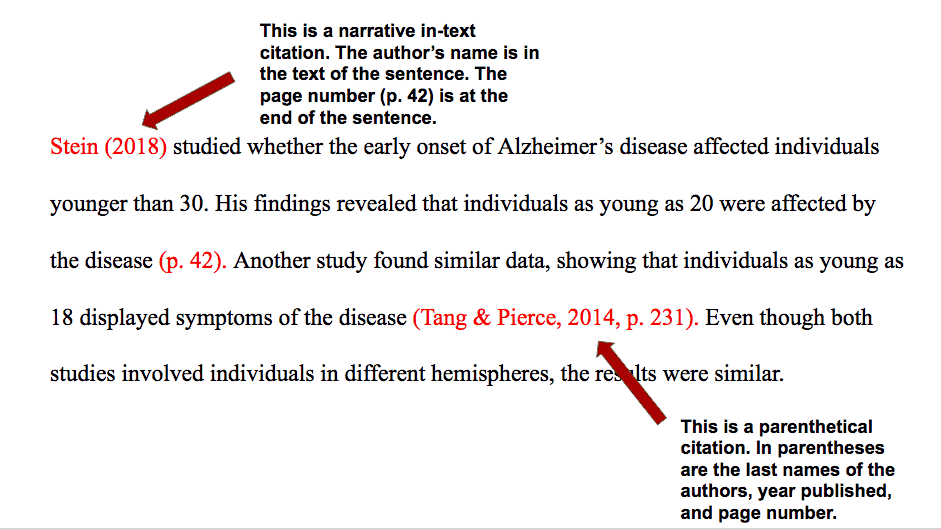

In-text APA citation format

Did you find the perfect quote or piece of information to include in your project? Way to go! It’s always a nice feeling when we find that magical piece of data or info to include in our writing. You probably already know that you can’t just copy and paste it into your project, or type it in, without also providing credit to the original author.

Displaying where the original information came from is much easier than you think.Directly next to the quote or information you included, place the author’s name and the year nearby. This allows the reader of your work to see where the information originated.

APA allows for the use of two different forms of in-text citation, parenthetical and narrative Both forms of citation require two elements:

- author’s name

- year of publication

The only difference is the way that this information is presented to the reader.

Parenthetical citations are the more commonly seen form of in-text citations for academic work, in which both required reference elements are presented at the end of the sentence in parentheses. Example:

Harlem had many artists and musicians in the late 1920s (Belafonte, 2008).

Narrative citations allow the author to present one or both of the required reference elements inside of the running sentence, which prevents the text from being too repetitive or burdensome. When only one of the two reference elements is included in the sentence, the other is provided parenthetically. Example:

According to Belafonte (2008), Harlem was full of artists and musicians in the late 1920s.

If there are two authors listed in the source entry, then the parenthetical reference must list them both:

(Smith & Belafonte, 2008)

If there are three or more authors listed in the source entry, then the parenthetical reference can abbreviate with “et al.”, the latin abbreviation for “and others”:

(Smith et al., 2008)

The author’s names are structured differently if there is more than one author. Things will also look different if there isn’t an author at all (which is sometimes the case with website pages). For more information on APA citation format, check out this page on the topic: APA parenthetical citation and APA in-text citation . There is also more information in the official manual in chapter 8.

If it’s MLA in-text and parenthetical citations you’re looking for, we’ve got your covered there too! You might want to also check out his guide on parenthetical citing .

Would you benefit from having a tool that helps you easily generate citations that are in the text? Check out EasyBib Plus!

References page in APA Format

An APA format reference page is easier to create than you probably think. We go into detail on how to create this page on our APA reference page . We also have a guide for how to create an annotated bibliography in APA . But, if you’re simply looking for a brief overview of the reference page, we’ve got you covered here.

Here are some pointers to keep in mind when it comes to the references page in APA format:

- This VIP page has its very own page. Start on a fresh, clean document (p. 303).

- Center and bold the title “References” (do not include quotation marks, underline, or italicize this title).

- Alphabetize and double-space ALL entries.

- Use a readable font, such as Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Lucida (p. 44).

- Every quote or piece of outside information included in the paper should be referenced and have an entry.

- Even though it’s called a “reference page,” it can be longer than one page. If your references flow onto the next page, then that’s a-okay.

- Only include the running head if it is required by your teacher or you’re writing a professional paper.

Sample reference page for a student paper:

Here’s another friendly reminder to use the EasyBib APA format generator (that comes with EasyBib Plus) to quickly and easily develop every single one of your references for you. Try it out! Our APA formatter is easy to use and ready to use 24/7.

Final APA Format Checklist

Prior to submitting your paper, check to make sure you have everything you need and everything in its place:

- Did you credit all of the information and quotes you used in the body of your paper and show a matching full reference at the end of the paper? Remember, you need both! Need more information on how to credit other authors and sources? Check out our other guides, or use the EasyBib APA format generator to credit your sources quickly and easily. EasyBib.com also has more styles than just the one this page focuses on.

- 12-pt. Times New Roman

- 11-pt. Calibri, Arial, Georgia

- 10-pt. Lucida, Sans Unicode, Computer Modern

- If you created an abstract, is it directly after the title page? Some teachers and professors do not require an abstract, so before you go ahead and include it, make sure it’s something he or she is expecting.

- Professional paper — Did you include a running head on every single page of your project?

- Student paper — Did you include page numbers in the upper right-hand corner of all your pages?

- Are all headings, as in section or chapter titles, properly formatted? If you’re not sure, check section number 9.

- Are all tables and figures aligned properly? Did you include notes and other important information directly below the table or figure? Include any information that will help the reader completely understand everything in the table or figure if it were to stand alone.

- Are abbreviations used sparingly? Did you format them properly?

- Is the entire document double spaced?

- Are all numbers formatted properly? Check section 17, which is APA writing format for numbers.

- Did you glance at the sample paper? Is your assignment structured similarly? Are all of the margins uniform?

Submitting Your APA Paper

Congratulations for making it this far! You’ve put a lot of effort into writing your paper and making sure the t’s are crossed and the i’s are dotted. If you’re planning to submit your paper for a school assignment, make sure you review your teacher or professor’s procedures.

If you’re submitting your paper to a journal, you probably need to include a cover letter.

Most cover letters ask you to include:

- The author’s contact information.

- A statement to the editor that the paper is original.

- If a similar paper exists elsewhere, notify the editor in the cover letter.

Once again, review the specific journal’s website for exact specifications for submission.

Okay, so you’re probably thinking you’re ready to hit send or print and submit your assignment. Can we offer one last suggestion? We promise it will only take a minute.

Consider running your paper through our handy dandy paper checker. It’s pretty simple.

Copy and paste or upload your paper into our checker. Within a minute, we’ll provide feedback on your spelling and grammar. If there’s a pronoun , interjection , or verb out of place, we’ll highlight it and offer suggestions for improvement. We’ll even take it a step further and point out any instances of possible plagiarism.

If it sounds too good to be true, then head on over to our innovative tool and give it a whirl. We promise you won’t be disappointed.

What is APA Format?

APA stands for the American Psychological Association . In this guide, you’ll find information related to “What is APA format?” in relation to writing and organizing your paper according to the American Psychological Association’s standards. Information on how to cite sources can be found on our APA citation page. The official American Psychological Association handbook was used as a reference for our guide and we’ve included page numbers from the manual throughout. However, this page is not associated with the association.

You’ll most likely use APA format if your paper is on a scientific topic. Many behavioral and social sciences use this organization’s standards and guidelines.

What are behavioral sciences? Behavioral sciences study human and animal behavior. They can include:

- Cognitive Science

- Neuroscience

What are social sciences? Social sciences focus on one specific aspect of human behavior, specifically social and cultural relationships. Social sciences can include:

- Anthropology

- Political Science

- Human Geography

- Archaeology

- Linguistics

What’s New in the 7th Edition?

This citation style was created by the American Psychological Association. Its rules and guidelines can be found in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . The information provided in the guide above follows the 6th edition (2009) of the manual. The 7th edition was published in 2020 and is the most recent version.

The 7th edition of the Publication Manual is in full color and includes 12 sections (compared to 8 sections in the 6th edition). In general, this new edition differentiates between professional and student papers, includes guidance with accessibility in mind, provides new examples to follow, and has updated guidelines.We’ve selected a few notable updates below, but for a full view of all of the 7th edition changes visit the style’s website linked here .

- Paper title

- Student name

- Affiliation (e.g., school, department, etc.)

- Course number and title

- Course instructor

- 6th edition – Running head: SMARTPHONE EFFECTS ON ADOLESCENT SOCIALIZATION

- 7th edition – SMARTPHONE EFFECTS ON ADOLESCENT SOCIALIZATION

- Pronouns . “They” can be used as a gender-neutral pronoun.

- Bias-free language guidelines . There are updated and new sections on guidelines for this section. New sections address participation in research, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality.

- Spacing after sentences. Add only a single space after end punctuation.

- Tables and figures . The citing format is now streamlined so that both tables and figures should include a name and number above the table/figure, and a note underneath the table/figure.

- 6th ed. – (Ikemoto, Richardson, Murphy, Yoshida 2016)

- 7th ed. – (Ikemoto et al., 2016)

- Citing books. The location of the publisher can be omitted. Also, e-books no longer need to mention the format (e.g., Kindle, etc.)

- Example: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-019-0153-5

- Using URLs. URLs no longer need to be prefaced by the words “Retrieved from.”

New citing information . There is new guidance on citing classroom or intranet resources, and oral traditions or traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples.

Visit our EasyBib Twitter feed to discover more citing tips, fun grammar facts, and the latest product updates.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.) (2020). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Published October 31, 2011. Updated May 14, 2020.

Written and edited by Michele Kirschenbaum and Elise Barbeau. Michele Kirschenbaum is a school library media specialist and the in-house librarian at EasyBib.com. Elise Barbeau is the Citation Specialist at Chegg. She has worked in digital marketing, libraries, and publishing.

APA Formatting Guide

APA Formatting

- Annotated Bibliography

- Block Quotes

- et al Usage

- Multiple Authors

- Paraphrasing

- Page Numbers

- Parenthetical Citations

- Sample Paper

- View APA Guide

Citation Examples

- Book Chapter

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Newspaper Article

- Website (no author)

- View all APA Examples

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

We should not use “et al.” in APA reference list entries. If the number of authors in the source is up to and including 20, list all author names and use an ampersand (&) before the final author’s name. If the number of authors is more than 20, list the first 19 authors’ names followed by an ellipsis (but no ampersand), and then add the final author’s name. An example of author names in a reference entry having more than 20 authors is given below:

Author Surname1, F. M., Author Surname2, F. M., Author Surname3, F. M., Author Surname4, F. M., Author Surname5, F. M., Author Surname6, F. M., Author Surname7, F. M., Author Surname8, F. M., Author Surname9, F. M., Author Surname10, F. M., Author Surname11, F. M., Author Surname12, F. M., Author Surname13, F. M., Author Surname14, F. M., Author Surname15, F. M., Author Surname16, F. M., Author Surname17, F. M., Author Surname18, F. M., Author Surname19, F. M., . . . Last Author Surname, F. M. (Publication Year).

Alvarez, L. D., Peach, J. L., Rodriguez, J. F., Donald, L., Thomas, M., Aruck, A., Samy, K., Anthony, K., Ajey, M., Rodriguez, K. L., Katherine, K., Vincent, A., Pater, F., Somu, P., Pander, L., Berd, R., Fox, L., Anders, A., Kamala, W., . . . Nicole Jones, K. (2019).

Note that, unlike references with 2 to 20 author names, the symbol “&” is not used here before the last author’s name.

APA 7, released in October 2019, has some new updates. Here is a brief description of the updates made in APA 7.

Different types of papers and best practices are given in detail in Chapter 1.

How to format a student title page is explained in Chapter 2. Examples of a professional paper and a student paper are included.

Chapter 3 provides additional information on qualitative and mixed methods of research.

An update on writing style is included in Chapter 4.

In chapter 5, some best practices for writing with bias-free language are included.

Chapter 6 gives some updates on style elements including using a single space after a period, including a citation with an abbreviation, the treatment of numbers in abstracts, treatment for different types of lists, and the formatting of gene and protein names.

In Chapter 7, additional examples are given for tables and figures for different types of publications.

In Chapter 8, how to format quotations and how to paraphrase text are covered with additional examples. A simplified version of in-text citations is clearly illustrated.

Chapter 9 has many updates: listing all author names up to 20 authors, standardizing DOIs and URLs, and the formatting of an annotated bibliography.

Chapter 10 includes many examples with templates for all reference types. New rules covering the inclusion of the issue number for journals and the omission of publisher location from book references are provided. Explanations of how to cite YouTube videos, power point slides, and TED talks are included.

Chapter 11 includes many legal references for easy understanding.

Chapter 12 provides advice for authors on how to promote their papers.

For more information on some of the changes found in APA 7, check out this EasyBib article .

APA Citation Examples

Writing Tools

Citation Generators

Other Citation Styles

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

APA Style: APA Style: Overview

What is apa style.

The American Psychological Association (APA) developed a set of standards that writers in the social sciences follow to create consistency throughout publications. These rules address:

- crediting sources

- document formatting

- writing style and organization

APA's guidelines assist readers in recognizing a writer's ideas and information, rather than having to adjust to inconsistent formatting. In this way, APA allows writers to express themselves clearly and easily to readers. The APA materials developed in the Walden Writing Center are based on The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Seventh Edition , often referred to on this website as "APA 7" or "the APA manual."

Why APA Style?

When you are writing as a student, you are entering into a new writing community ; just as you would need to learn the customs and rules of any new country you visit, you need to learn the customs and rules of academic writing. These guidelines will be different than guidelines for writing in other environments (such as letters to friends, emails to coworkers, or writing for blogs). The academic community has its own rules. These standards help writers

- improve clarity

- avoid distracting the reader

- indicate sources for evidence

- provide uniform formatting

To learn more about transitioning into academic writing, view "What Is Academic Writing?" Remember that it’s your job as the author to engage your readers, and inconsistencies in formatting and citations distract the reader from the content of your writing. By using APA style, you allow your readers to focus on the ideas you are presenting, offering a familiar format to discuss your new ideas.

Getting Started With APA Style

APA style can seem overwhelming at first. To get started, take some time to look through these resources:

- Familiarize yourself with the column on the left; peruse the different pages to see what APA has to say about citations, reference entries, capitalization, numbers, et cetera.

- Find our APA templates , determining which is the most appropriate for your assignments (hint: the first "Course Paper" template is best for most course assignments).

- Use this APA Checklist to review your assignments, ensuring you have remembered all of APA's rules.

- If you previously used the 6th edition of APA, visit our APA 6 and APA 7 Comparison Tables to learn what’s new in the 7th edition.

- Review one of our APA webinars (like "How and When to Include APA Citations" ), based on your interest.

- Find the APA resources in our APA Scavenger Hunt , helping to familiarize yourself with the APA resources we have on the website.

- Check out our APA-related blog posts .

Lastly, have a question? Ask OASIS !

Crash Course in APA Style Video

- Crash Course in APA Style (video transcript)

Methods to the Madness Video Playlist

Writing Center Blog Posts on APA

Related resources.

Knowledge Check: APA Style Overview

Knowledge Check

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Next Page: APA Manual Quick Guide

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

APA Style (7th ed.)

- Getting Started

- Formatting Your Paper

- Elements of Citation

- In-Text Citations

- Reference List

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) & Generated Text

- Business Sources

- Government Documents

- Journal Articles

- Lecture Notes, PowerPoint Slides, Handouts

- Media Kits, Press Releases

- Newspapers & Magazines

- Personal Communication

- Oral Communications with Indigenous Elders & Knowledge Keepers

- Social Media

- Software & Computer Code

- Tables & Figures

- Videos & Film

- APA Resources

Getting Started with APA Style, 7th ed.

About this guide.

This guide offers a variety of examples for different types of sources commonly used in academic assignments. Examples are based on our interpretation of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th edition. You can also view APA's official Style & Grammar Guidelines online.

Your professor may have different citing expectations than the rules outlined in this guide. Always check at the beginning of term and before starting assignments that the citing rules you are using are appropriate for your class.

Tutoring and library staff can answer questions about citing your sources, and can help clarify citation rules. Our role is to help students learn how to cite. Students are responsible for proofreading their own citations.

Book a Citation Appointment

Appointments with English/Writing Tutors or AIR Specialists can be booked through TutorOcean.

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 12:30 PM

- URL: https://sheridancollege.libguides.com/apa

Connect with us

APA Citation Guide (APA 7th Edition): Welcome

- Advertisements

- Artificial Intelligence

- Audio Materials

- Books, eBooks, Course Packs, Lab Manuals & Pamphlets

- Business Reports from Library Databases

- Case Studies

- Class Notes, Class Recordings, Class Lectures and Presentations

- Creative Commons Licensed Works

- Digital Assignments: Citing Your Sources This link opens in a new window

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Games & Objects

- Government Documents

- Images, Infographics, Maps, Charts & Tables

- Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers (Oral Communication)

- Journal Articles

- Legal Resources

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Personal Communications (including interviews, emails, intranet resources)

- Religious & Classical (e.g., Ancient Greek, Roman) Works

- Social Media

- Theses & Dissertations

- Websites (including documents/PDFs posted on websites)

- When Information is Missing

- Works in Another Language / Translations

- Works Quoted in Another Source (Indirect Sources)

- Quoting vs. Paraphrasing

- APA Citation FAQs

- Plagiarism This link opens in a new window

- APA for Faculty This link opens in a new window

What is APA Citation Style?

APA Style is a set of guidelines for writing, formatting research papers and assignments, and referencing sources. When citing in APA, you need to cite all the sources that you have used within the body of your work (in-text citation), and in the References List at the end of your essay or assignment. Seneca Libraries citation support and resources are based on the latest edition of the APA Publication Manual (7th edition).

- See the citation examples tab for guidelines on how to cite a variety of sources in APA

- See the APA Citation FAQs for answers to common APA questions

- Check out a video and infographic which highlights major changes in APA Style 7th edition

Academic Integrity Badges: For information and questions about earning badges, please see Academic Integrity: Student Resources , or contact [email protected].

Online Citation Workshops

Attend a live workshop to learn about the basics of citing your sources and get answers to your citation questions . (Note: We encourage students to join before the workshop start time as a courtesy to other attendees)

Can't attend a workshop? View the APA | MLA | APA & MLA recording , or view the p resentation slides: APA | MLA | APA & MLA

- Sample Papers

- Setting Up Your Paper

- Annotated Bibliography

- Common Mistakes

Note: To edit the templates in Google Docs, upload them into your Google Drive and open as a Google doc.

- APA 7th ed. Sample Paper (Seneca example)

- APA 7th ed. Sample Paper - Group Assignment (Seneca example)

- APA 7th ed. Sample Paper - With Figures (Seneca Example)

- APA 7th ed. Sample Paper - With Appendix (Seneca Example)

- APA Checklist Finished your assignment? Use this checklist to ensure you haven't missed information needed for APA Style.

Tips for formatting your APA Style paper

Margins : Add 1 inch margins on all sides.

Header : Starting with your title page, add page numbers at the top right corner of the page.

Line Spacing : Double-space your text.

Paragraph Alignment & Indentation : Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inch. Align your paragraphs to the left margin.

Recommended Fonts: Unless specified by your instructor, APA recommends the following fonts:

- 11-point Calibri

- 11-point Arial

- 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode

- 12-point Times New Roman

- 11-point Georgia

- 10-point Computer Modern

- Heading Levels (APA Style) If your instructor requires you to use APA Style headings and sub-headings, this document will show you how they work.

- Annotated Bibliography Guide An overview to writing an annotated bibliography and APA annotated bibliography template.

Live Citation Chat

Note: This citation guide is based on the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). The contents are accurate to the best of our knowledge. Some examples illustrate Seneca Libraries' recommendations and are marked as modifications of the official APA guidelines.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . It is used/adapted with the permission of Seneca Libraries. For information please contact [email protected] . When copying this guide, please retain this box.

- Next: Citation Examples >>

- Last Updated: Jun 25, 2024 5:07 PM

- URL: https://library.senecapolytechnic.ca/apa

- Plagiarism and grammar

- Citation guides

APA Citation Generator

Don't let plagiarism errors spoil your paper, a comprehensive guide to apa citations and format, overview of this guide:.

This page provides you with an overview of APA format, 7th edition. Included is information about referencing, various citation formats with examples for each source type, and other helpful information.

If you’re looking for MLA format , check out the Citation Machine MLA Guide. Also, visit the Citation Machine homepage to use the APA formatter, which is an APA citation generator, and to see more styles .

Being responsible while researching

When you’re writing a research paper or creating a research project, you will probably use another individual’s work to help develop your own assignment. A good researcher or scholar uses another individual’s work in a responsible way. This involves indicating that the work of other individuals is included in your project (i.e., citing), which is one way to prevent plagiarism.

Plagiarism? What is it?

The word plagiarism is derived from the Latin word, plagiare , which means “to kidnap.” The term has evolved over the years to now mean the act of taking another individual’s work and using it as your own, without acknowledging the original author (American Psychological Association, 2020 p. 21). Plagiarism can be illegal and there can be serious ramifications for plagiarizing someone else’s work. Thankfully, plagiarism can be prevented. One way it can be prevented is by including citations and references in your research project. Want to make them quickly and easily? Try the Citation Machine citation generator, which is found on our homepage.

All about citations & references

Citations and references should be included anytime you use another individual’s work in your own assignment. When including a quote, paraphrased information, images, or any other piece of information from another’s work, you need to show where you found it by including a citation and a reference. This guide explains how to make them.

APA style citations are added in the body of a research paper or project and references are added to the last page.

Citations , which are called in-text citations, are included when you’re adding information from another individual’s work into your own project. When you add text word-for-word from another source into your project, or take information from another source and place it in your own words and writing style (known as paraphrasing), you create an in-text citation. These citations are short in length and are placed in the main part of your project, directly after the borrowed information.

References are found at the end of your research project, usually on the last page. Included on this reference list page is the full information for any in-text citations found in the body of the project. These references are listed in alphabetical order by the author's last name.

An APA in-text citation includes only three items: the last name(s) of the author(s), the year the source was published, and sometimes the page or location of the information. References include more information such as the name of the author(s), the year the source was published, the full title of the source, and the URL or page range.

Why is it important to include citations & references