A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2024 11:22 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

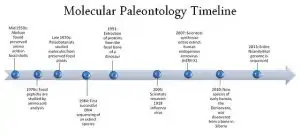

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

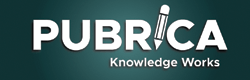

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

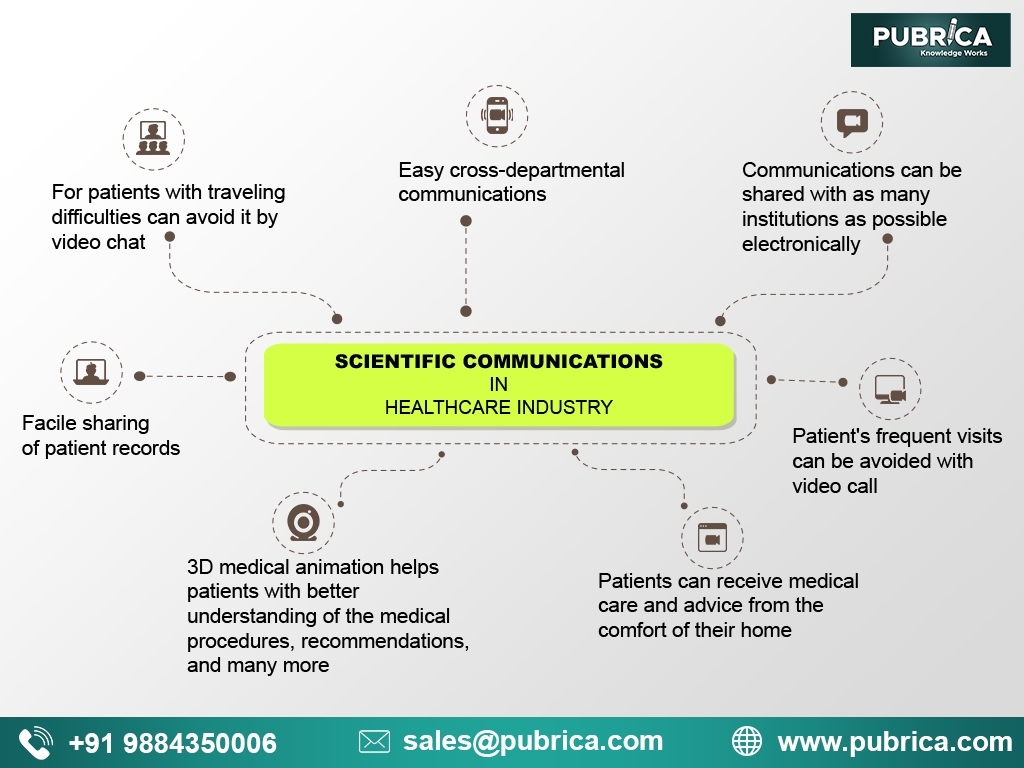

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

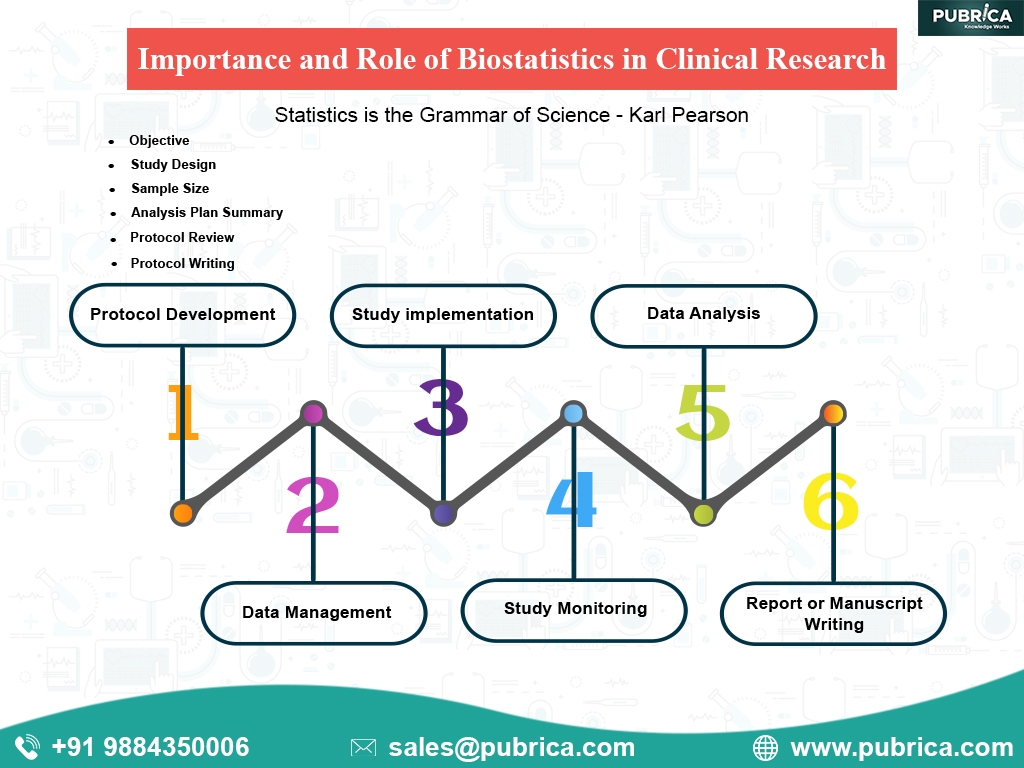

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

PUB - Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient) for drug development

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

PUB - Health Economics of Data Modeling

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS

- v.35(2); Jul-Dec 2014

Reviewing literature for research: Doing it the right way

Shital amin poojary.

Department of Dermatology, K J Somaiya Medical College, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Jimish Deepak Bagadia

In an era of information overload, it is important to know how to obtain the required information and also to ensure that it is reliable information. Hence, it is essential to understand how to perform a systematic literature search. This article focuses on reliable literature sources and how to make optimum use of these in dermatology and venereology.

INTRODUCTION

A thorough review of literature is not only essential for selecting research topics, but also enables the right applicability of a research project. Most importantly, a good literature search is the cornerstone of practice of evidence based medicine. Today, everything is available at the click of a mouse or at the tip of the fingertips (or the stylus). Google is often the Go-To search website, the supposed answer to all questions in the universe. However, the deluge of information available comes with its own set of problems; how much of it is actually reliable information? How much are the search results that the search string threw up actually relevant? Did we actually find what we were looking for? Lack of a systematic approach can lead to a literature review ending up as a time-consuming and at times frustrating process. Hence, whether it is for research projects, theses/dissertations, case studies/reports or mere wish to obtain information; knowing where to look, and more importantly, how to look, is of prime importance today.

Literature search

Fink has defined research literature review as a “systematic, explicit and reproducible method for identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing the existing body of completed and recorded work produced by researchers, scholars and practitioners.”[ 1 ]

Review of research literature can be summarized into a seven step process: (i) Selecting research questions/purpose of the literature review (ii) Selecting your sources (iii) Choosing search terms (iv) Running your search (v) Applying practical screening criteria (vi) Applying methodological screening criteria/quality appraisal (vii) Synthesizing the results.[ 1 ]

This article will primarily concentrate on refining techniques of literature search.

Sources for literature search are enumerated in Table 1 .

Sources for literature search

PubMed is currently the most widely used among these as it contains over 23 million citations for biomedical literature and has been made available free by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), U.S. National Library of Medicine. However, the availability of free full text articles depends on the sources. Use of options such as advanced search, medical subject headings (MeSH) terms, free full text, PubMed tutorials, and single citation matcher makes the database extremely user-friendly [ Figure 1 ]. It can also be accessed on the go through mobiles using “PubMed Mobile.” One can also create own account in NCBI to save searches and to use certain PubMed tools.

PubMed home page showing location of different tools which can be used for an efficient literature search

Tips for efficient use of PubMed search:[ 2 , 3 , 4 ]

Use of field and Boolean operators

When one searches using key words, all articles containing the words show up, many of which may not be related to the topic. Hence, the use of operators while searching makes the search more specific and less cumbersome. Operators are of two types: Field operators and Boolean operators, the latter enabling us to combine more than one concept, thereby making the search highly accurate. A few key operators that can be used in PubMed are shown in Tables Tables2 2 and and3 3 and illustrated in Figures Figures2 2 and and3 3 .

Field operators used in PubMed search

Boolean operators used in PubMed search

PubMed search results page showing articles on donovanosis using the field operator [TIAB]; it shows all articles which have the keyword “donovanosis” in either title or abstract of the article

PubMed search using Boolean operators ‘AND’, ‘NOT’; To search for articles on treatment of lepra reaction other than steroids, after clicking the option ‘Advanced search’ on the home page, one can build the search using ‘AND’ option for treatment and ‘NOT’ option for steroids to omit articles on steroid treatment in lepra reaction

Use of medical subject headings terms

These are very specific and standardized terms used by indexers to describe every article in PubMed and are added to the record of every article. A search using MeSH will show all articles about the topic (or keywords), but will not show articles only containing these keywords (these articles may be about an entirely different topic, but still may contain your keywords in another context in any part of the article). This will make your search more specific. Within the topic, specific subheadings can be added to the search builder to refine your search [ Figure 4 ]. For example, MeSH terms for treatment are therapy and therapeutics.

PubMed search using medical subject headings (MeSH) terms for management of gonorrhea. Click on MeSH database ( Figure 1 ) →In the MeSH search box type gonorrhea and click search. Under the MeSH term gonorrhea, there will be a list of subheadings; therapy, prevention and control, click the relevant check boxes and add to search builder →Click on search →All articles on therapy, prevention and control of gonorrhea will be displayed. Below the subheadings, there are two options: (1) Restrict to medical subject headings (MeSH) major topic and (2) do not include MeSH terms found below this term in the MeSH hierarchy. These can be used to further refine the search results so that only articles which are majorly about treatment of gonorrhea will be displayed

Two additional options can be used to further refine MeSH searches. These are located below the subheadings for a MeSH term: (1) Restrict to MeSH major topic; checking this box will retrieve articles which are majorly about the search term and are therefore, more focused and (2) Do not include MeSH terms found below this term in the MeSH hierarchy. This option will again give you more focused articles as it excludes the lower specific terms [ Figure 4 ].

Similar feature is available with Cochrane library (also called MeSH), EMBASE (known as EMTREE) and PsycINFO (Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms).

Saving your searches

Any search that one has performed can be saved by using the ‘Send to’ option and can be saved as a simple word file [ Figure 5 ]. Alternatively, the ‘Save Search’ button (just below the search box) can be used. However, it is essential to set up an NCBI account and log in to NCBI for this. One can even choose to have E-mail updates of new articles in the topic of interest.

Saving PubMed searches. A simple option is to click on the dropdown box next to ‘Send to’ option and then choose among the options. It can be saved as a text or word file by choosing ‘File’ option. Another option is the “Save search” option below the search box but this will require logging into your National Center for Biotechnology Information account. This however allows you to set up alerts for E-mail updates for new articles

Single citation matcher

This is another important tool that helps to find the genuine original source of a particular research work (when few details are known about the title/author/publication date/place/journal) and cite the reference in the most correct manner [ Figure 6 ].

Single citation matcher: Click on “Single citation matcher” on PubMed Home page. Type available details of the required reference in the boxes to get the required citation

Full text articles

In any search clicking on the link “free full text” (if present) gives you free access to the article. In some instances, though the published article may not be available free, the author manuscript may be available free of charge. Furthermore, PubMed Central articles are available free of charge.

Managing filters

Filters can be used to refine a search according to type of article required or subjects of research. One can specify the type of article required such as clinical trial, reviews, free full text; these options are available on a typical search results page. Further specialized filters are available under “manage filters:” e.g., articles confined to certain age groups (properties option), “Links” to other databases, article specific to particular journals, etc. However, one needs to have an NCBI account and log in to access this option [ Figure 7 ].

Managing filters. Simple filters are available on the ‘search results’ page. One can choose type of article, e.g., clinical trial, reviews etc. Further options are available in the “Manage filters” option, but this requires logging into National Center for Biotechnology Information account

The Cochrane library

Although reviews are available in PubMed, for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, Cochrane library is a much better resource. The Cochrane library is a collection of full length systematic reviews, which can be accessed for free in India, thanks to Indian Council of Medical Research renewing the license up to 2016, benefitting users all over India. It is immensely helpful in finding detailed high quality research work done in a particular field/topic [ Figure 8 ].

Cochrane library is a useful resource for reliable, systematic reviews. One can choose the type of reviews required, including trials

An important tool that must be used while searching for research work is screening. Screening helps to improve the accuracy of search results. It is of two types: (1) Practical: To identify a broad range of potentially useful studies. Examples: Date of publication (last 5 years only; gives you most recent updates), participants or subjects (humans above 18 years), publication language (English only) (2) methodological: To identify best available studies (for example, excluding studies not involving control group or studies with only randomized control trials).

Selecting the right quality of literature is the key to successful research literature review. The quality can be estimated by what is known as “The Evidence Pyramid.” The level of evidence of references obtained from the aforementioned search tools are depicted in Figure 9 . Systematic reviews obtained from Cochrane library constitute level 1 evidence.

Evidence pyramid: Depicting the level of evidence of references obtained from the aforementioned search tools

Thus, a systematic literature review can help not only in setting up the basis of a good research with optimal use of available information, but also in practice of evidence-based medicine.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Strategies to Find Sources

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Strategies to Find Sources

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- How to Pick a Topic

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

The Research Process

![why is related literature important in research Interative Litearture Review Research Process image (Planning, Searching, Organizing, Analyzing and Writing [repeat at necessary]](https://libapps.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/64450/images/ResearchProcess.jpg)

Planning : Before searching for articles or books, brainstorm to develop keywords that better describe your research question.

Searching : While searching, take note of what other keywords are used to describe your topic, and use them to conduct additional searches

♠ Most articles include a keyword section

♠ Key concepts may change names throughout time so make sure to check for variations

Organizing : Start organizing your results by categories/key concepts or any organizing principle that make sense for you . This will help you later when you are ready to analyze your findings

Analyzing : While reading, start making notes of key concepts and commonalities and disagreement among the research articles you find.

♠ Create a spreadsheet to record what articles you are finding useful and why.

♠ Create fields to write summaries of articles or quotes for future citing and paraphrasing .

Writing : Synthesize your findings. Use your own voice to explain to your readers what you learned about the literature on your topic. What are its weaknesses and strengths? What is missing or ignored?

Repeat : At any given time of the process, you can go back to a previous step as necessary.

Advanced Searching

All databases have Help pages that explain the best way to search their product. When doing literature reviews, you will want to take advantage of these features since they can facilitate not only finding the articles that you really need but also controlling the number of results and how relevant they are for your search. The most common features available in the advanced search option of databases and library online catalogs are:

- Boolean Searching (AND, OR, NOT): Allows you to connect search terms in a way that can either limit or expand your search results

- Proximity Searching (N/# or W/#): Allows you to search for two or more words that occur within a specified number of words (or fewer) of each other in the database

- Limiters/Filters : These are options that let you control what type of document you want to search: article type, date, language, publication, etc.

- Question mark (?) or a pound sign (#) for wildcard: Used for retrieving alternate spellings of a word: colo?r will retrieve both the American spelling "color" as well as the British spelling "colour."

- Asterisk (*) for truncation: Used for retrieving multiple forms of a word: comput* retrieves computer, computers, computing, etc.

Want to keep track of updates to your searches? Create an account in the database to receive an alert when a new article is published that meets your search parameters!

- EBSCOhost Advanced Search Tutorial Tips for searching a platform that hosts many library databases

- Library's General Search Tips Check the Search tips to better used our library catalog and articles search system

- ProQuest Database Search Tips Tips for searching another platform that hosts library databases

There is no magic number regarding how many sources you are going to need for your literature review; it all depends on the topic and what type of the literature review you are doing:

► Are you working on an emerging topic? You are not likely to find many sources, which is good because you are trying to prove that this is a topic that needs more research. But, it is not enough to say that you found few or no articles on your topic in your field. You need to look broadly to other disciplines (also known as triangulation ) to see if your research topic has been studied from other perspectives as a way to validate the uniqueness of your research question.

► Are you working on something that has been studied extensively? Then you are going to find many sources and you will want to limit how far back you want to look. Use limiters to eliminate research that may be dated and opt to search for resources published within the last 5-10 years.

- << Previous: How to Pick a Topic

- Next: Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Frequently asked questions

What is the purpose of a literature review.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Frequently asked questions: Academic writing

A rhetorical tautology is the repetition of an idea of concept using different words.

Rhetorical tautologies occur when additional words are used to convey a meaning that has already been expressed or implied. For example, the phrase “armed gunman” is a tautology because a “gunman” is by definition “armed.”

A logical tautology is a statement that is always true because it includes all logical possibilities.

Logical tautologies often take the form of “either/or” statements (e.g., “It will rain, or it will not rain”) or employ circular reasoning (e.g., “she is untrustworthy because she can’t be trusted”).

You may have seen both “appendices” or “appendixes” as pluralizations of “ appendix .” Either spelling can be used, but “appendices” is more common (including in APA Style ). Consistency is key here: make sure you use the same spelling throughout your paper.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

Editing and proofreading are different steps in the process of revising a text.

Editing comes first, and can involve major changes to content, structure and language. The first stages of editing are often done by authors themselves, while a professional editor makes the final improvements to grammar and style (for example, by improving sentence structure and word choice ).

Proofreading is the final stage of checking a text before it is published or shared. It focuses on correcting minor errors and inconsistencies (for example, in punctuation and capitalization ). Proofreaders often also check for formatting issues, especially in print publishing.

The cost of proofreading depends on the type and length of text, the turnaround time, and the level of services required. Most proofreading companies charge per word or page, while freelancers sometimes charge an hourly rate.

For proofreading alone, which involves only basic corrections of typos and formatting mistakes, you might pay as little as $0.01 per word, but in many cases, your text will also require some level of editing , which costs slightly more.

It’s often possible to purchase combined proofreading and editing services and calculate the price in advance based on your requirements.

There are many different routes to becoming a professional proofreader or editor. The necessary qualifications depend on the field – to be an academic or scientific proofreader, for example, you will need at least a university degree in a relevant subject.

For most proofreading jobs, experience and demonstrated skills are more important than specific qualifications. Often your skills will be tested as part of the application process.

To learn practical proofreading skills, you can choose to take a course with a professional organization such as the Society for Editors and Proofreaders . Alternatively, you can apply to companies that offer specialized on-the-job training programmes, such as the Scribbr Academy .

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Reasons the Literature Review Is Crucial to Your Paper

3-minute read

- 8th November 2016

People often treat writing the literature review in an academic paper as a formality. Usually, this means simply listing various studies vaguely related to their work and leaving it at that.

But this overlooks how important the literature review is to a well-written experimental report or research paper. As such, we thought we’d take a moment to go over what a literature review should do and why you should give it the attention it deserves.

What Is a Literature Review?

Common in the social and physical sciences, but also sometimes required in the humanities, a literature review is a summary of past research in your subject area.

Sometimes this is a standalone investigation of how an idea or field of inquiry has developed over time. However, more usually it’s the part of an academic paper, thesis or dissertation that sets out the background against which a study takes place.

There are several reasons why we do this.

Reason #1: To Demonstrate Understanding

In a college paper, you can use a literature review to demonstrate your understanding of the subject matter. This means identifying, summarizing and critically assessing past research that is relevant to your own work.

Reason #2: To Justify Your Research

The literature review also plays a big role in justifying your study and setting your research question . This is because examining past research allows you to identify gaps in the literature, which you can then attempt to fill or address with your own work.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Reason #3: Setting a Theoretical Framework

It can help to think of the literature review as the foundations for your study, since the rest of your work will build upon the ideas and existing research you discuss therein.

A crucial part of this is formulating a theoretical framework , which comprises the concepts and theories that your work is based upon and against which its success will be judged.

Reason #4: Developing a Methodology

Conducting a literature review before beginning research also lets you see how similar studies have been conducted in the past. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research, you can thus make sure you adopt the most appropriate methods, data sources and analytical techniques for your own work.

Reason #5: To Support Your Own Findings

The significance of any results you achieve will depend to some extent on how they compare to those reported in the existing literature. When you come to write up your findings, your literature review will therefore provide a crucial point of reference.

If your results replicate past research, for instance, you can say that your work supports existing theories. If your results are different, though, you’ll need to discuss why and whether the difference is important.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Service update: Some parts of the Library’s website will be down for maintenance on July 7.

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Literature Review in Research Writing

- 4 minute read

- 426.6K views

Table of Contents

Research on research? If you find this idea rather peculiar, know that nowadays, with the huge amount of information produced daily all around the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to keep up to date with all of it. In addition to the sheer amount of research, there is also its origin. We are witnessing the economic and intellectual emergence of countries like China, Brazil, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, for example, that are producing scholarly literature in their own languages. So, apart from the effort of gathering information, there must also be translators prepared to unify all of it in a single language to be the object of the literature survey. At Elsevier, our team of translators is ready to support researchers by delivering high-quality scientific translations , in several languages, to serve their research – no matter the topic.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a study – or, more accurately, a survey – involving scholarly material, with the aim to discuss published information about a specific topic or research question. Therefore, to write a literature review, it is compulsory that you are a real expert in the object of study. The results and findings will be published and made available to the public, namely scientists working in the same area of research.

How to Write a Literature Review

First of all, don’t forget that writing a literature review is a great responsibility. It’s a document that is expected to be highly reliable, especially concerning its sources and findings. You have to feel intellectually comfortable in the area of study and highly proficient in the target language; misconceptions and errors do not have a place in a document as important as a literature review. In fact, you might want to consider text editing services, like those offered at Elsevier, to make sure your literature is following the highest standards of text quality. You want to make sure your literature review is memorable by its novelty and quality rather than language errors.

Writing a literature review requires expertise but also organization. We cannot teach you about your topic of research, but we can provide a few steps to guide you through conducting a literature review:

- Choose your topic or research question: It should not be too comprehensive or too limited. You have to complete your task within a feasible time frame.

- Set the scope: Define boundaries concerning the number of sources, time frame to be covered, geographical area, etc.

- Decide which databases you will use for your searches: In order to search the best viable sources for your literature review, use highly regarded, comprehensive databases to get a big picture of the literature related to your topic.

- Search, search, and search: Now you’ll start to investigate the research on your topic. It’s critical that you keep track of all the sources. Start by looking at research abstracts in detail to see if their respective studies relate to or are useful for your own work. Next, search for bibliographies and references that can help you broaden your list of resources. Choose the most relevant literature and remember to keep notes of their bibliographic references to be used later on.

- Review all the literature, appraising carefully it’s content: After reading the study’s abstract, pay attention to the rest of the content of the articles you deem the “most relevant.” Identify methodologies, the most important questions they address, if they are well-designed and executed, and if they are cited enough, etc.

If it’s the first time you’ve published a literature review, note that it is important to follow a special structure. Just like in a thesis, for example, it is expected that you have an introduction – giving the general idea of the central topic and organizational pattern – a body – which contains the actual discussion of the sources – and finally the conclusion or recommendations – where you bring forward whatever you have drawn from the reviewed literature. The conclusion may even suggest there are no agreeable findings and that the discussion should be continued.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews constantly feed new research, that constantly feeds literature reviews…and we could go on and on. The fact is, one acts like a force over the other and this is what makes science, as a global discipline, constantly develop and evolve. As a scientist, writing a literature review can be very beneficial to your career, and set you apart from the expert elite in your field of interest. But it also can be an overwhelming task, so don’t hesitate in contacting Elsevier for text editing services, either for profound edition or just a last revision. We guarantee the very highest standards. You can also save time by letting us suggest and make the necessary amendments to your manuscript, so that it fits the structural pattern of a literature review. Who knows how many worldwide researchers you will impact with your next perfectly written literature review.

Know more: How to Find a Gap in Research .

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Research Gap

Types of Scientific Articles

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Open access

- Published: 03 July 2024

The impact of evidence-based nursing leadership in healthcare settings: a mixed methods systematic review

- Maritta Välimäki 1 , 2 ,

- Shuang Hu 3 ,

- Tella Lantta 1 ,

- Kirsi Hipp 1 , 4 ,

- Jaakko Varpula 1 ,

- Jiarui Chen 3 ,

- Gaoming Liu 5 ,

- Yao Tang 3 ,

- Wenjun Chen 3 &

- Xianhong Li 3

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 452 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

458 Accesses

Metrics details

The central component in impactful healthcare decisions is evidence. Understanding how nurse leaders use evidence in their own managerial decision making is still limited. This mixed methods systematic review aimed to examine how evidence is used to solve leadership problems and to describe the measured and perceived effects of evidence-based leadership on nurse leaders and their performance, organizational, and clinical outcomes.

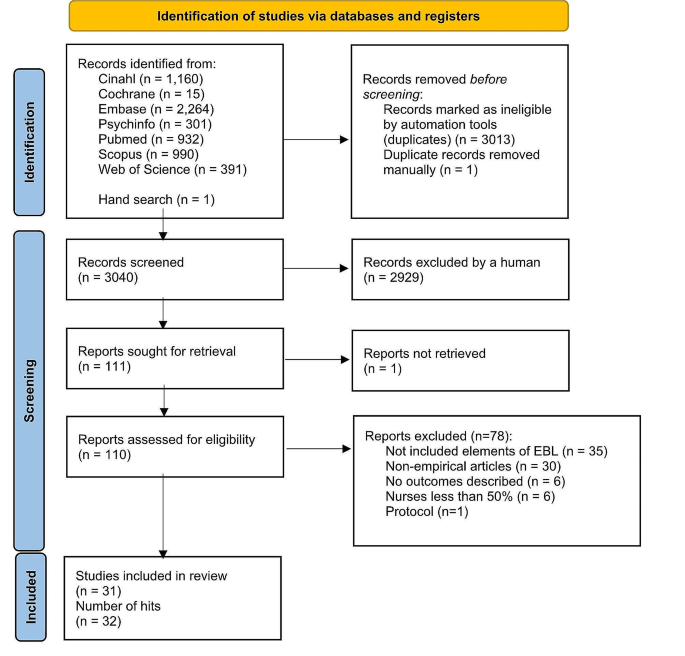

We included articles using any type of research design. We referred nurses, nurse managers or other nursing staff working in a healthcare context when they attempt to influence the behavior of individuals or a group in an organization using an evidence-based approach. Seven databases were searched until 11 November 2021. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-experimental studies, JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool were used to evaluate the Risk of bias in quasi-experimental studies, case series, mixed methods studies, respectively. The JBI approach to mixed methods systematic reviews was followed, and a parallel-results convergent approach to synthesis and integration was adopted.

Thirty-one publications were eligible for the analysis: case series ( n = 27), mixed methods studies ( n = 3) and quasi-experimental studies ( n = 1). All studies were included regardless of methodological quality. Leadership problems were related to the implementation of knowledge into practice, the quality of nursing care and the resource availability. Organizational data was used in 27 studies to understand leadership problems, scientific evidence from literature was sought in 26 studies, and stakeholders’ views were explored in 24 studies. Perceived and measured effects of evidence-based leadership focused on nurses’ performance, organizational outcomes, and clinical outcomes. Economic data were not available.

Conclusions

This is the first systematic review to examine how evidence is used to solve leadership problems and to describe its measured and perceived effects from different sites. Although a variety of perceptions and effects were identified on nurses’ performance as well as on organizational and clinical outcomes, available knowledge concerning evidence-based leadership is currently insufficient. Therefore, more high-quality research and clinical trial designs are still needed.

Trail registration

The study was registered (PROSPERO CRD42021259624).

Peer Review reports

Global health demands have set new roles for nurse leaders [ 1 ].Nurse leaders are referred to as nurses, nurse managers, or other nursing staff working in a healthcare context who attempt to influence the behavior of individuals or a group based on goals that are congruent with organizational goals [ 2 ]. They are seen as professionals “armed with data and evidence, and a commitment to mentorship and education”, and as a group in which “leaders innovate, transform, and achieve quality outcomes for patients, health care professionals, organizations, and communities” [ 3 ]. Effective leadership occurs when team members critically follow leaders and are motivated by a leader’s decisions based on the organization’s requests and targets [ 4 ]. On the other hand, problems caused by poor leadership may also occur, regarding staff relations, stress, sickness, or retention [ 5 ]. Therefore, leadership requires an understanding of different problems to be solved using synthesizing evidence from research, clinical expertise, and stakeholders’ preferences [ 6 , 7 ]. If based on evidence, leadership decisions, also referred as leadership decision making [ 8 ], could ensure adequate staffing [ 7 , 9 ] and to produce sufficient and cost-effective care [ 10 ]. However, nurse leaders still rely on their decision making on their personal [ 11 ] and professional experience [ 10 ] over research evidence, which can lead to deficiencies in the quality and safety of care delivery [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. As all nurses should demonstrate leadership in their profession, their leadership competencies should be strengthened [ 15 ].

Evidence-informed decision-making, referred to as evidence appraisal and application, and evaluation of decisions [ 16 ], has been recognized as one of the core competencies for leaders [ 17 , 18 ]. The role of evidence in nurse leaders’ managerial decision making has been promoted by public authorities [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Evidence-based management, another concept related to evidence-based leadership, has been used as the potential to improve healthcare services [ 22 ]. It can guide nursing leaders, in developing working conditions, staff retention, implementation practices, strategic planning, patient care, and success of leadership [ 13 ]. Collins and Holton [ 23 ] in their systematic review and meta-analysis examined 83 studies regarding leadership development interventions. They found that leadership training can result in significant improvement in participants’ skills, especially in knowledge level, although the training effects varied across studies. Cummings et al. [ 24 ] reviewed 100 papers (93 studies) and concluded that participation in leadership interventions had a positive impact on the development of a variety of leadership styles. Clavijo-Chamorro et al. [ 25 ] in their review of 11 studies focused on leadership-related factors that facilitate evidence implementation: teamwork, organizational structures, and transformational leadership. The role of nurse managers was to facilitate evidence-based practices by transforming contexts to motivate the staff and move toward a shared vision of change.

As far as we are aware, however, only a few systematic reviews have focused on evidence-based leadership or related concepts in the healthcare context aiming to analyse how nurse leaders themselves uses evidence in the decision-making process. Young [ 26 ] targeted definitions and acceptance of evidence-based management (EBMgt) in healthcare while Hasanpoor et al. [ 22 ] identified facilitators and barriers, sources of evidence used, and the role of evidence in the process of decision making. Both these reviews concluded that EBMgt was of great importance but used limitedly in healthcare settings due to a lack of time, a lack of research management activities, and policy constraints. A review by Williams [ 27 ] showed that the usage of evidence to support management in decision making is marginal due to a shortage of relevant evidence. Fraser [ 28 ] in their review further indicated that the potential evidence-based knowledge is not used in decision making by leaders as effectively as it could be. Non-use of evidence occurs and leaders base their decisions mainly on single studies, real-world evidence, and experts’ opinions [ 29 ]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses rarely provide evidence of management-related interventions [ 30 ]. Tate et al. [ 31 ] concluded based on their systematic review and meta-analysis that the ability of nurse leaders to use and critically appraise research evidence may influence the way policy is enacted and how resources and staff are used to meet certain objectives set by policy. This can further influence staff and workforce outcomes. It is therefore important that nurse leaders have the capacity and motivation to use the strongest evidence available to effect change and guide their decision making [ 27 ].

Despite of a growing body of evidence, we found only one review focusing on the impact of evidence-based knowledge. Geert et al. [ 32 ] reviewed literature from 2007 to 2016 to understand the elements of design, delivery, and evaluation of leadership development interventions that are the most reliably linked to outcomes at the level of the individual and the organization, and that are of most benefit to patients. The authors concluded that it is possible to improve individual-level outcomes among leaders, such as knowledge, motivation, skills, and behavior change using evidence-based approaches. Some of the most effective interventions included, for example, interactive workshops, coaching, action learning, and mentoring. However, these authors found limited research evidence describing how nurse leaders themselves use evidence to support their managerial decisions in nursing and what the outcomes are.