Are you an agency specialized in UX, digital marketing, or growth? Join our Partner Program

Learn / Guides / UX research guide

Back to guides

How to write effective UX research questions (with examples)

Collecting and analyzing real user feedback is essential in delivering an excellent user experience (UX). But not all user research is created equal—and done wrong, it can lead to confusion, miscommunication, and non-actionable results.

Last updated

Reading time.

You need to ask the right UX research questions to get the valuable insights necessary to continually optimize your product and generate user delight.

This article shows you how to write strong UX research questions, ensuring you go beyond guesswork and assumptions . It covers the difference between open- and close-ended research questions, explains how to go about creating your own UX research questions, and provides several examples to get you started.

Use Hotjar to ask your users the right UX research questions

Put your UX research questions to work with Hotjar's Feedback and Survey tools to uncover product experience insights

The different types of UX research questions

Let’s face it, asking the right UX research questions is hard. It’s a skill that takes a lot of practice and can leave even the most seasoned UX researchers drawing a blank.

There are two main categories of UX research questions: open-ended and close-ended, both of which are essential to achieving thorough, high-quality UX research. Qualitative research—based on descriptions and experiences—leans toward open-ended questions, whereas quantitative research leans toward closed-ended questions.

Let’s dive into the differences between them.

Open-ended UX research questions

Open-ended UX research questions are exactly what they sound like: they prompt longer, more free-form responses, rather than asking someone to choose from established possible answers—like multiple-choice tests.

Open questions are easily recognized because they:

Usually begin with how, why, what, describe, or tell me

Can’t be easily answered with just yes or no, or a word or two

Are qualitative rather than quantitative

If there’s a simple fact you’re trying to get to, a closed question would work. For anything involving our complex and messy human nature, open questions are the way to go.

Open-ended research questions aim to discover more about research participants and gather candid user insights, rather than seeking specific answers.

Some examples of UX research that use open-ended questions include:

Usability testing

Diary studies

Persona research

Use case research

Task analysis

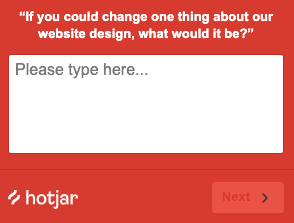

Check out a concrete example of an open-ended UX research question in action below. Hotjar’s Survey tool is a perfect way of gathering longer-form user feedback, both on-site and externally.

Pros and cons of open-ended UX research questions

Like everything in life, open-ended UX research questions have their pros and cons.

Advantages of open-ended questions include:

Detailed, personal answers

Great for storytelling

Good for connecting with people on an emotional level

Helpful to gauge pain points, frustrations, and desires

Researchers usually end up discovering more than initially expected

Less vulnerable to bias

Drawbacks include:

People find them more difficult to answer than closed-ended questions

More time-consuming for both the researcher and the participant

Can be difficult to conduct with large numbers of people

Can be challenging to dig through and analyze open-ended questions

Closed-ended UX research questions

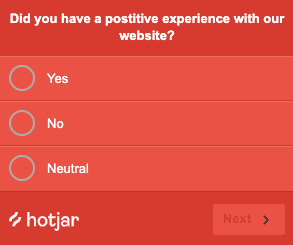

Close-ended UX research questions have limited possible answers. Participants can respond to them with yes or no, by selecting an option from a list, by ranking or rating, or with a single word.

They’re easy to recognize because they’re similar to classic exam-style questions.

More technical industries might start with closed UX research questions because they want statistical results. Then, we’ll move on to more open questions to see how customers really feel about the software we put together.

While open-ended research questions reveal new or unexpected information, closed-ended research questions work well to test assumptions and answer focused questions. They’re great for situations like:

Surveying a large number of participants

When you want quantitative insights and hard data to create metrics

When you’ve already asked open-ended UX research questions and have narrowed them down into close-ended questions based on your findings

If you’re evaluating something specific so the possible answers are limited

If you’re going to repeat the same study in the future and need uniform questions and answers

Wondering what a closed-ended UX research question might look in real life? The example below shows how Hotjar’s Feedback widgets help UX researchers hear from users 'in the wild' as they navigate.

The different types of closed-ended questions

There are several different ways to ask close-ended UX research questions, including:

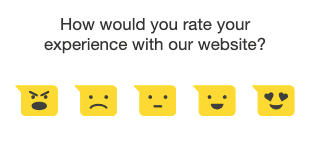

Customer satisfaction (CSAT) surveys

CSAT surveys are closed-ended UX research questions that explore customer satisfaction levels by asking users to rank their experience on some kind of scale, like the happy and angry icons in the image below.

On-site widgets like Hotjar's Feedback tool below excel at gathering quick customer insights without wreaking havoc on the user experience. They’re especially popular on ecommerce sites or after customer service interactions.

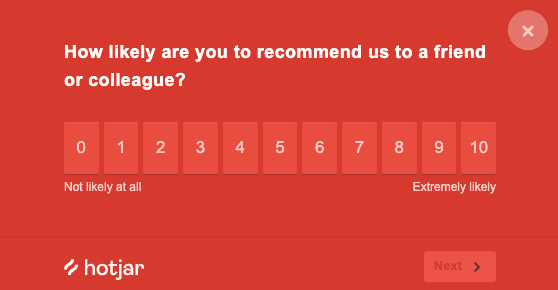

Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys

NPS surveys are another powerful type of (mostly) closed-ended UX research questions. They ask customers how likely they are to recommend a company, product, or service to their community. Responses to NPS surveys are used to calculate Net Promoter Score .

NPS surveys split customers into three categories:

Promoters (9-10): Your most enthusiastic, vocal, and loyal customers

Passives (7-8): Ho-hum. They’re more or less satisfied customers but could be susceptible to jumping ship

Detractors (0-6): Dissatisfied customers who are at a high risk of spreading bad reviews

Net Promoter Score is a key metric used to predict business growth, track long-term success, and gauge overall customer satisfaction.

Pro tip: while the most important question to ask in an NPS survey is readiness to recommend, it shouldn’t be the only one. Asking follow-up questions can provide more context and a deeper understanding of the customer experience. Combining Hotjar Feedback widgets with standalone Surveys is a great strategy for tracking NPS through both quick rankings and qualitative feedback.

Pros and cons of closed-ended research questions

Close-ended UX research questions have solid advantages, including:

More measurable data to convert into statistics and metrics

Higher response rates because they’re generally more straightforward for people to answer

Easier to coordinate when surveying a large number of people

Great for evaluating specifics and facts

Little to no irrelevant answers to comb through

Putting the UX researcher in control

But closed-ended questions can be tricky to get right. Their disadvantages include:

Leading participants to response bias

Preventing participants from telling the whole story

The lack of insight into opinions or emotions

Too many possible answers overwhelming participants

Too few possible answers, meaning the 'right' answer for each participant might not be included

How to form your own UX research questions

To create effective UX questions, start by defining your research objectives and hypotheses, which are assumptions you’ll put to the test with user feedback.

Use this tried-and-tested formula to create research hypotheses by filling in the blanks according to your unique user and business goals:

We believe (doing x)

For (x people)

Will achieve (x outcome)

For example: ' We believe adding a progress indicator into our checkout process (for customers) will achieve 20% lower cart abandonment rates.'

Pro tip: research hypotheses aren’t set in stone. Keep them dynamic as you formulate, change, and re-evaluate them throughout the UX research process, until your team comes away with increased certainty about their initial assumption.

When nailing down your hypotheses, remember that research is just as much about discovering new questions as it is about getting answers. Don’t think of research as a validation exercise where you’re looking to confirm something you already know. Instead, cultivate an attitude of exploration and strive to dig deeper into user emotions, needs, and challenges.

Once you have a working hypothesis, identify your UX research objective . Your objective should be linked to your hypothesis, defining what your product team wants to accomplish with your research—for example, ' We want to improve our cart abandonment rates by providing customers with a seamless checkout experience.'

Now that you’ve formulated a hypothesis and research objective, you can create your general or 'big picture' research questions . These define precisely what you want to discover through your research, but they’re not the exact questions you’ll ask participants. This is an important distinction because big picture research questions focus on the researchers themselves rather than users.

A big picture question might be something like: ' How can we improve our cart abandonment rates?'

With a strong hypothesis, objective, and general research question in the bag, you’re finally ready to create the questions you’ll ask participants.

32 examples of inspiring UX research questions

There are countless different categories of UX research questions.

We focus on open-ended, ecommerce-oriented questions here , but with a few tweaks, these could be easily transformed into closed-ended questions.

For example, an open-ended question like, 'Tell us about your overall experience shopping on our website' could be turned into a closed-ended question such as, ' Did you have a positive experience finding everything you needed on our website?'

Screening questions

Screening questions are the first questions you ask UX research participants. They help you get to know your customers and work out whether they fit into your ideal user personas.

These survey question examples focus on demographic and experience-based questions. For instance:

Tell me about yourself. Who are you and what do you do?

What does a typical day look like for you?

How old are you?

What’s the highest level of education that you’ve completed?

How comfortable do you feel using the internet?

How comfortable do you feel browsing or buying products online?

How frequently do you buy products online?

Do you prefer shopping in person or online? Why?

Awareness questions

Awareness questions explore how long your participants have been aware of your brand and how much they know about it. Some good options include:

How did you find out about our brand?

What prompted you to visit our website for the first time?

If you’ve visited our website multiple times, what made you come back?

How long was the gap between finding out about us and your first purchase?

Expectation questions

Expectation questions investigate the assumptions UX research participants have about brands, products, or services before using them. For example:

What was your first impression of our brand?

What was your first impression of X product or service?

How do you think using X product or service would benefit you?

What problem would X product or service solve for you?

Do you think X product or service is similar to another one on the market? Please specify.

Task-specific questions

Task-specific questions focus on user experiences as they complete actions on your site. Some examples include:

Tell us what you thought about the overall website design and content layout

How was your browsing experience?

How was your checkout experience?

What was the easiest task to complete on our website?

What was the hardest task to complete on our website?

Experience questions

Experience questions dig deeper into research participants’ holistic journeys as they navigate your site. These include:

Tell us how you felt when you landed on our website homepage

How can we improve the X page of our website?

What motivated you to purchase X product or service?

What stopped you from purchasing X product or service?

Was your overall experience positive or negative while shopping on our website? Why?

Concluding questions

Concluding questions ask participants to reflect on their overall experience with your brand, product, or service. For instance:

What are your biggest questions about X product or service?

What are your biggest concerns about X product or service?

If you could change one thing about X product or service, what would it be?

Would you recommend X product or service to a friend?

How would you compare X product or service to X competitor?

Excellent research questions are key for an optimal UX

To create a fantastic UX, you need to understand your users on a deeper level.

Crafting strong questions to deploy during the research process is an important way to gain that understanding, because UX research shouldn’t center on what you want to learn but what your users can teach you.

UX research question FAQs

What are ux research questions.

UX research questions can refer to two different things: general UX research questions and UX interview questions.

Both are vital components of UX research and work together to accomplish the same goals—understanding user needs and pain points, challenging assumptions, discovering new insights, and finding solutions.

General UX research questions focus on what UX researchers want to discover through their study.

UX interview questions are the exact questions researchers ask participants during their research study.

What are examples of UX research questions?

UX research question examples can be split into several categories. Some of the most popular include:

Screening questions: help get to know research participants better and focus on demographic and experience-based information. For example: “What does a typical day look like for you?”

Awareness questions: explore how much research participants know about your brand, product, or service. For example: “What prompted you to visit our website for the first time?”

Expectation questions: investigate assumptions research participants have about your brand, product, or service. For example: “What was your first impression of X?”

Task-specific questions: dive into participants’ experiences trying to complete actions on your site. For example: “What was the easiest task to complete on our website?”

Experience questions: dig deep into participants’ overall holistic experiences navigating through your site. For example: “Was your overall experience shopping on our website positive or negative? Why?”

Concluding questions: ask participants to reflect on their overall experience with your brand, product, or service. For example: “What are your biggest concerns about (x product or service)?”

What’s the difference between open-ended and closed-ended UX research questions?

The difference between open- and closed-ended UX research questions is simple. Open-ended UX research questions prompt long, free-form responses. They’re qualitative rather than quantitative and can’t be answered easily with yes or no, or a word or two. They’re easy to recognize because they begin with terms like how, why, what, describe, and tell me.

On the other hand, closed-ended UX research questions have limited possible answers. Participants can respond to them with yes or no, by selecting an option from a list, by rating or ranking options, or with just a word or two.

UX research process

Previous chapter

UX research tools

Next chapter

UX Research: Objectives, Assumptions, and Hypothesis

by Rick Dzekman

An often neglected step in UX research

Introduction

UX research should always be done for a clear purpose – otherwise you’re wasting the both your time and the time of your participants. But many people who do UX research fail to properly articulate the purpose in their research objectives. A major issue is that the research objectives include assumptions that have not been properly defined.

When planning UX research you have some goal in mind:

- For generative research it’s usually to find out something about users or customers that you previously did not know

- For evaluative research it’s usually to identify any potential issues in a solution

As part of this goal you write down research objectives that help you achieve that goal. But for many researchers (especially more junior ones) they are missing some key steps:

- How will those research objectives help to reach that goal?

- What assumptions have you made that are necessary for those objectives to reach that goal?

- How does your research (questions, tasks, observations, etc.) help meet those objectives?

- What kind of responses or observations do you need from your participants to meet those objectives?

One approach people use is to write their objectives in the form of research hypothesis. There are a lot of problems when trying to validate a hypothesis with qualitative research and sometimes even with quantitative.

This article focuses largely on qualitative research: interviews, user tests, diary studies, ethnographic research, etc. With qualitative research in mind let’s start by taking a look at a few examples of UX research hypothesis and how they may be problematic.

Research hypothesis

Example hypothesis: users want to be able to filter products by colour.

At first it may seem that there are a number of ways to test this hypothesis with qualitative research. For example we might:

- Observe users shopping on sites with and without colour filters and see whether or not they use them

- Ask users who are interested in our products about how narrow down their choices

- Run a diary study where participants document the ways they narrowed down their searches on various stores

- Make a prototype with colour filters and see if participants use them unprompted

These approaches are all effective but they do not and cannot prove or disprove our hypothesis. It’s not that the research methods are ineffective it’s that the hypothesis itself is poorly expressed.

The first problem is that there are hidden assumptions made by this hypothesis. Presumably we would be doing this research to decide between a choice of possible filters we could implement. But there’s no obvious link between users wanting to filter by colour and a benefit from us implementing a colour filter. Users may say they want it but how will that actually benefit their experience?

The second problem with this hypothesis is that we’re asking a question about “users” in general. How many users would have to want colour filters before we could say that this hypothesis is true?

Example Hypothesis: Adding a colour filter would make it easier for users to find the right products

This is an obvious improvement to the first example but it still has problems. We could of course identify further assumptions but that will be true of pretty much any hypothesis. The problem again comes from speaking about users in general.

Perhaps if we add the ability to filter by colour it might make the possible filters crowded and make it more difficult for users who don’t need colour to find the filter that they do need. Perhaps there is a sample bias in our research participants that does not apply broadly to our user base.

It is difficult (though not impossible) to design research that could prove or disprove this hypothesis. Any such research would have to be quantitative in nature. And we would have to spend time mapping out what it means for something to be “easier” or what “the right products” are.

Example Hypothesis: Travelers book flights before they book their hotels

The problem with this hypothesis should now be obvious: what would it actually mean for this hypothesis to be proved or disproved? What portion of travelers would need to book their flights first for us to consider this true?

Example Hypothesis: Most users who come to our app know where and when they want to fly

This hypothesis is better because it talks about “most users” rather than users in general. “Most” would need to be better defined but at least this hypothesis is possible to prove or disprove.

We could address this hypothesis with quantitative research. If we found out that it was true we could focus our design around the primary use case or do further research about how to attract users at different stages of their journey.

However there is no clear way to prove or disprove this hypothesis with qualitative research. If the app has a million users and 15/20 research participants tell you that this is true would your findings generalise to the entire user base? The margin of error on that finding is 20-25%, meaning that the true results could be closer to 50% or even 100% depending on how unlucky you are with your sample.

Example Hypothesis: Customers want their bank to help them build better savings habits

There are many things wrong with this hypothesis but we will focus on the hidden assumptions and the links to design decisions. Two big assumptions are that (1) it’s possible to find out what research participants want and (2) people’s wants should dictate what features or services to provide.

Research objectives

One of the biggest problem with using hypotheses is that they set the wrong expectations about what your research results are telling you. In Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman points out that:

- “extreme outcomes (both high and low) are more likely to be found in small than in large samples”

- “the prominence of causal intuitions is a recurrent theme in this book because people are prone to apply causal thinking inappropriately, to situations that require statistical reasoning”

- “when people believe a conclusion is true, they are also very likely to believe arguments that appear to support it, even when these arguments are unsound”

Using a research hypothesis primes us to think that we have found some fundamental truth about user behaviour from our qualitative research. This leads to overconfidence about what the research is saying and to poor quality research that could simply have been skipped in exchange for simply making assumption. To once again quote Kahneman: “you do not believe that these results apply to you because they correspond to nothing in your subjective experience”.

We can fix these problems by instead putting our focus on research objectives. We pay attention to the reason that we are doing the research and work to understand if the results we get could help us with our objectives.

This does not get us off the hook however because we can still create poor research objectives.

Let’s look back at one of our prior hypothesis examples and try to find effective research objectives instead.

Example objectives: deciding on filters

In thinking about the colour filter we might imagine that this fits into a larger project where we are trying to decide what filters we should implement. This is decidedly different research to trying to decide what order to implement filters in or understand how they should work. In this case perhaps we have limited resources and just want to decide what to implement first.

A good approach would be quantitative research designed to produce some sort of ranking. But we should not dismiss qualitative research for this particular project – provided our assumptions are well defined.

Let’s consider this research objective: Understand how users might map their needs against the products that we offer . There are three key aspects to this objective:

- “Understand” is a common form of research objective and is a way that qualitative research can discover things that we cannot find with quant. If we don’t yet understand some user attitude or behaviour we cannot quantify it. By focusing our objective on understanding we are looking at uncovering unknowns.

- By using the word “might” we are not definitively stating that our research will reveal all of the ways that users think about their needs.

- Our focus is on understanding the users’ mental models. Then we are not designing for what users say that they want and we aren’t even designing for existing behaviour. Instead we are designing for some underlying need.

The next step is to look at the assumptions that we are making. One assumption is that mental models are roughly the same between most people. So even though different users may have different problems that for the most part people tend to think about solving problems with the same mental machinery. As we do more research we might discover that this assumption is not true and there are distinctly different kinds of behaviours. Perhaps we know what those are in advance and we can recruit our research participants in a way that covers those distinct behaviours.

Another assumption is that if we understand our users’ mental models that we will be able to design a solution that will work for most people. There are of course more assumptions we could map but this is a good start.

Now let’s look at another research objective: Understand why users choose particular filters . Again we are looking to understand something that we did not know before.

Perhaps we have some prior research that tells us what the biggest pain points are that our products solve. If we have an understanding of why certain filters are used we can think about how those motivations fit in with our existing knowledge.

Mapping objectives to our research plan

Our actual research will involve some form of asking questions and/or making observations. It’s important that we don’t simply forget about our research objectives and start writing questions. This leads to completing research and realising that you haven’t captured anything about some specific objective.

An important step is to explicitly write down all the assumptions that we are making in our research and to update those assumptions as we write our questions or instructions. These assumptions will help us frame our research plan and make sure that we are actually learning the things that we think we are learning. Consider even high level assumptions such as: a solution we design with these insights will lead to a better experience, or that a better experience is necessarily better for the user.

Once we have our main assumptions defined the next step is to break our research objective down further.

Breaking down our objectives

The best way to consider this breakdown is to think about what things we could learn that would contribute to meeting our research objective. Let’s consider one of the previous examples: Understand how users might map their needs against the products that we offer

We may have an assumption that users do in fact have some mental representation of their needs that align with the products they might purchase. An aspect of this research objective is to understand whether or not this true. So two sub-objectives may be to (1) understand why users actually buy these sorts of products (if at all), and (2) understand how users go about choosing which product to buy.

Next we might want to understand what our users needs actually are or if we already have research about this understand which particular needs apply to our research participants and why.

And finally we would want to understand what factors go into addressing a particular need. We may leave this open ended or even show participants attributes of the products and ask which ones address those needs and why.

Once we have a list of sub-objectives we could continue to drill down until we feel we’ve exhausted all the nuances. If we’re happy with our objectives the next step is to think about what responses (or observations) we would need in order to answer those objectives.

It’s still important that we ask open ended questions and see what our participants say unprompted. But we also don’t want our research to be so open that we never actually make any progress on our research objectives.

Reviewing our objectives and pilot studies

At the end it’s important to review every task, question, scenario, etc. and seeing which research objectives are being addressed. This is vital to make sure that your planning is worthwhile and that you haven’t missed anything.

If there’s time it’s also useful to run a pilot study and analyse the responses to see if they help to address your objectives.

Plan accordingly

It should be easy to see why research hypothesis are not suitable for most qualitative research. While it is possible to create suitable hypothesis it is more often than not going to lead to poor quality research. This is because hypothesis create the impression that qualitative research can find things that generalise to the entire user base. In general this is not true for the sample sizes typically used for qualitative research and also generally not the reason that we do qualitative research in the first place.

Instead we should focus on producing effective research objectives and making sure every part of our research plan maps to a suitable objective.

Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

How to create a perfect design hypothesis

A design hypothesis is a cornerstone of the UX and UI design process. It guides the entire process, defines research needs, and heavily influences the final outcome.

Doing any design work without a well-defined hypothesis is like riding a car without headlights. Although still possible, it forces you to go slower and dramatically increases the chances of unpleasant pitfalls.

The importance of a hypothesis in the design process

Design change for your hypothesis, the objective of your hypothesis, mapping underlying assumptions in your hypothesis, example 1: a simple design hypothesis, example 2: a robust design hypothesis.

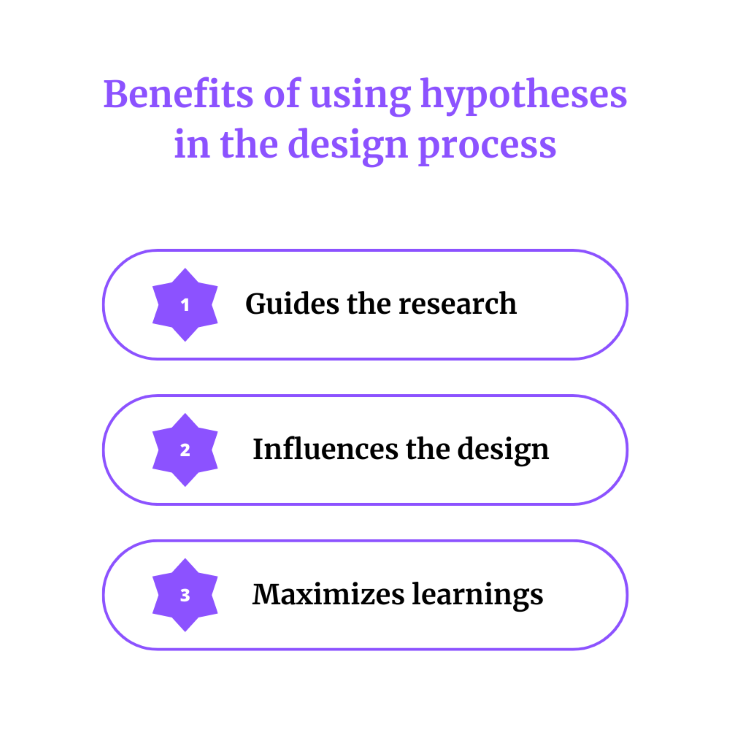

There are three main reasons why no discovery or design process should start without a well-defined and framed hypothesis. A good design hypothesis helps us:

- Guide the research

- Nail the solutions

- Maximize learnings and enable iterative design

A design hypothesis guides research

A good hypothesis not only states what we want to achieve but also the final objective and our current beliefs. It allows designers to assess how much actual evidence there is to support the hypothesis and focus their research and discovery efforts on areas they are least confident about.

Research for the sake of research brings waste. Research for the sake of validating specific hypotheses brings learnings.

A design hypothesis influences the design and solution

Design hypothesis gives much-needed context. It helps you:

- Ideate right solutions

- Focus on the proper UX

- Polish UI details

The more detailed and robust the design hypothesis, the more context you have to help you make the best design decisions.

A design hypothesis maximizes learnings and enables iterative design

If you design new features blindly, it’s hard to truly learn from the launch. Some metrics might go up. Others might go down, so what?

With a well-defined design hypothesis, you can not only validate whether the design itself works but also better understand why and how to improve it in the future. This helps you iterate on your learnings.

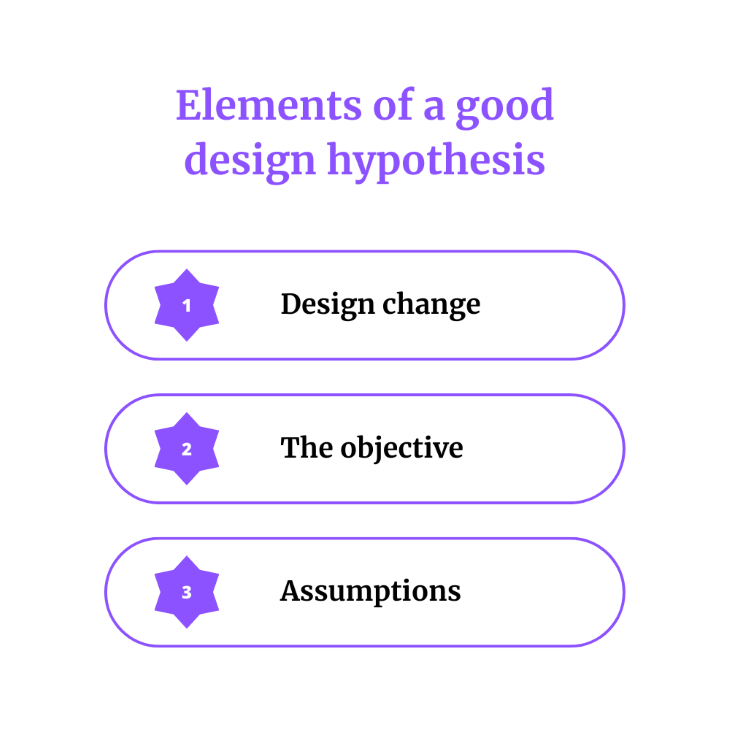

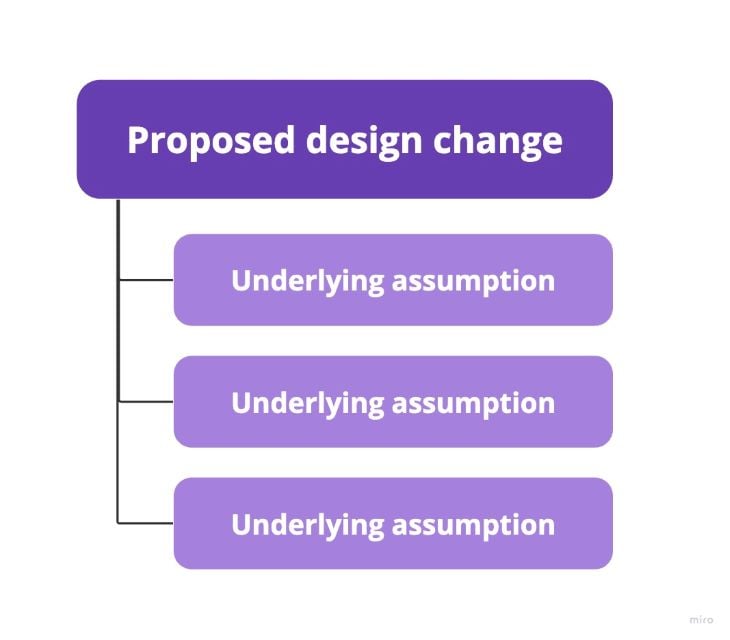

Components of a good design hypothesis

I am not a fan of templatizing how a solid design hypothesis should look. There are various ways to approach it, and you should choose whatever works for you best. However, there are three essential elements you should include to ensure you get all the benefits mentioned earlier of using design hypotheses, that is:

- Design change

- The objective

- Underlying assumptions

The fundamental part is the definition of what you are trying to do. If you are working on shortening the onboarding process, you might simply put “[…] we’d like to shorten the onboarding process […].”

The goal here is to give context to a wider audience and be able to quickly reference that the design hypothesis is concerning. Don’t fret too much about this part; simply boil the problem down to its essentials. What is frustrating your users?

In other words, the objective is the “why” behind the change. What exactly are you trying to achieve with the planned design change? The objective serves a few purposes.

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

First, it’s a great sanity check. You’d be surprised how many designers proposed various ideas, changes, and improvements without a clear goal. Changing design just for the sake of changing the design is a no-no.

It also helps you step back and see if the change you are considering is the best approach. For instance, if you are considering shortening the onboarding to increase the percentage of users completing it, are there any other design changes you can think of to achieve the same goal? Maybe instead of shortening the onboarding, there’s a bigger opportunity in simply adjusting the copy? Defining clear objectives invites conversations about whether you focus on the right things.

Additionally, a clearly defined objective gives you a measure of success to evaluate the effectiveness of your solution. If you believed you could boost the completion rate by 40 percent, but achieved only a 10 percent lift, then either the hypothesis was flawed (good learning point for the future), or there’s still room for improvements.

Last but not least, a clear objective is essential for the next step: mapping underlying assumptions.

Now that you know what you plan to do and which goal you are trying to achieve, it’s time for the most critical question.

Why do you believe the proposed design change will achieve the desired objective? Whether it’s because you heard some interesting insights during user interviews or spotted patterns in users’ behavioral data, note it down.

Even if you don’t have any strong justification and base your hypothesis on pure guesses (we all do that sometimes!), clearly name these beliefs. Listing out all your assumption will help you:

- Focus your discovery efforts on validating these assumptions to avoid late disappointments

- Better analyze results post-launch to maximize your learnings

You’ll see exactly how in the examples of good design hypotheses below.

Examples of good design hypotheses

Let’s put it all into practice and see what a good design hypothesis might look like.

I’ll use two examples:

- A simple design hypothesis

- A robust design hypothesis

You should still formulate a design hypothesis if you are working on minor changes, such as changing the copy on buttons. But there’s also no point in spending hours formulating a perfect hypothesis for a fifteen-minute test. In these cases, I’d just use a simple one-sentence hypothesis.

Yet, suppose you are working on an extensive and critical initiative, such as redesigning the whole conversion funnel. In that case, you might want to put more effort into a more robust and detailed design hypothesis to guide your entire process.

A simple example of a design hypothesis could be:

Moving the sign-up button to the top of the page will increase our conversion to registration by 10 percent, as most users don’t look at the bottom of the page.

Although it’s pretty straightforward, it still can help you in a few ways.

First of all, it helps prioritize experiments. If there is another small experiment in the backlog, but with the hypothesis that it’ll improve conversion to registration by 15 percent, it might influence the order of things you work on.

Impact assessments (where the 10 percent or 15 percent comes from) are another quite advanced topic, so I won’t cover it in detail, but in most cases, you can ask your product manager and/or data analyst for help.

It also allows you to validate the hypothesis without even experimenting. If you guessed that people don’t look at the bottom of the page, you can check your analytics tools to see what the scroll rate is or check heatmaps.

Lastly, if your hypothesis fails (that is, the conversion rate doesn’t improve), you get valuable insights that can help you reassess other hypotheses based on the “most users don’t look at the bottom of the page” assumption.

Now let’s take a look at a slightly more robust assumption. An example could be:

Shortening the number of screens during onboarding by half will boost our free trial to subscription conversion by 20 percent because:

- Most users don’t complete the whole onboarding flow

- Shorter onboarding will increase the onboarding completion rate

- Focusing on the most important features will increase their adoption

- Which will lead to aha moments and better premium retention

- Users will perceive our product as simpler and less complex

The most significant difference is our effort to map all relevant assumptions.

Listing out assumptions can help you test them out in isolation before committing to the initiative.

For example, if you believe most users don’t complete the onboarding flow , you can check self-serve tools or ask your PM for help to validate if that’s true. If the data shows only 10 percent of users finish the onboarding, the hypothesis is stronger and more likely to be successful. If, on the other hand, most users do complete the whole onboarding, the idea suddenly becomes less promising.

The second advantage is the number of learnings you can get from the post-release analysis.

Say the change led to a 10 percent increase in conversion. Instead of blindly guessing why it didn’t meet expectations, you can see how each assumption turned out.

It might turn out that some users actually perceive the product as more complex (rather than less complex, as you assumed), as they have difficulty figuring out some functionalities that were skipped in the onboarding. Thus, they are less willing to convert.

Not only can it help you propose a second iteration of the experiment, that learning will help you greatly when working on other initiatives based on a similar assumption.

Closing thoughts

Ensuring everything you work on is based on a solid design hypothesis can greatly help you and your career.

It’ll guide your research and discovery in the right direction, enable better iterative design, maximize learning, and help you make better design decisions.

Some designers might think, “Hypotheses are the job of a product manager, not a designer.”

While that’s partly true, I believe designers should be proactive in working with hypotheses.

If there are none set, do it yourself for the sake of your own success. If all your designs succeed, or worse, flunk, no one will care who set or didn’t set the hypotheses behind these decisions. You’ll be judged, too.

If there’s a hypothesis set upfront, try to understand it, refine it, and challenge it if needed.

Most senior and desired product designers are not just pixel-pushers that do what they are being told to do, but they also play an active role in shaping the direction of the product as a whole. Becoming fluent in working with hypotheses is a significant step toward true seniority.

Header image source: IconScout

LogRocket : Analytics that give you UX insights without the need for interviews

LogRocket lets you replay users' product experiences to visualize struggle, see issues affecting adoption, and combine qualitative and quantitative data so you can create amazing digital experiences.

See how design choices, interactions, and issues affect your users — get a demo of LogRocket today .

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- #ux research

Stop guessing about your digital experience with LogRocket

Recent posts:.

The Double Diamond design process: An overview

Learn what the Double Diamond design process is and how to leverage it to design impactful solutions that engage users.

How should color symbolism shape your UX designs?

Every color choice you make for your designs is more powerful than you think. I talk all about color symbolism in this blog.

What is web brutalism, and how does it challenge modern UX design?

Web brutalism shuns convention for raw, bold style. Today, I discuss how it’s impacting modern web design.

The ADPList: Mentorship for UX designers

Think UX mentorship is just for newbies? Think again. In this blog, I talk all about why the ADPList is a must for all UX designers to level up and share design know-how!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Product Design (UX/UI) Bundle and save

User Research

Content Design

UX Design Fundamentals

Software and Coding Fundamentals for UX

- UX training for teams

- Hire our alumni

- Student Stories

- State of UX Hiring Report 2024

- Our mission

- Advisory Council

Education for every phase of your UX career

Professional Diploma

Learn the full user experience (UX) process from research to interaction design to prototyping.

Combine the UX Diploma with the UI Certificate to pursue a career as a product designer.

Professional Certificates

Learn how to plan, execute, analyse and communicate user research effectively.

Master content design and UX writing principles, from tone and style to writing for interfaces.

Understand the fundamentals of UI elements and design systems, as well as the role of UI in UX.

Short Courses

Gain a solid foundation in the philosophy, principles and methods of user experience design.

Learn the essentials of software development so you can work more effectively with developers.

Give your team the skills, knowledge and mindset to create great digital products.

Join our hiring programme and access our list of certified professionals.

Learn about our mission to set the global standard in UX education.

Meet our leadership team with UX and education expertise.

Members of the council connect us to the wider UX industry.

Our team are available to answer any of your questions.

Fresh insights from experts, alumni and the wider design community.

Success stories from our course alumni building thriving careers.

Discover a wealth of UX expertise on our YouTube channel.

Latest industry insights. A practical guide to landing a job in UX.

A complete guide to presenting UX research findings

In this complete guide to presenting UX research findings, we’ll cover what you should include in a UX research report, how to present UX research findings and tips for presenting your UX research.

Free course: Introduction to UX Design

What is UX? Why has it become so important? Could it be a career for you? Learn the answers, and more, with a free 7-lesson video course.

User experience research sets out to identify the problem that a product or service needs to solve and finds a way to do just that. Research is the first and most important step to optimising user experience.

UX researchers do this through interviews, surveys, focus groups, data analysis and reports. Reports are how UX researchers present their work to other stakeholders in a company, such as designers, developers and executives.

In this guide, we’ll cover what you should include in a UX research report, how to present UX research findings and tips for presenting your UX research.

Components of a UX research report

How to write a ux research report, 5 tips on presenting ux research findings.

Ready to present your research findings? Let’s dive in.

[GET CERTIFIED IN USER RESEARCH]

There are six key components to a UX research report.

Introduction

The introduction should give an overview of your UX research . Then, relate any company goals or pain points to your research. Lastly, your introduction should briefly touch on how your research could affect the business.

Research goals

Simply put, your next slide or paragraph should outline the top decisions you need to make, the search questions you used, as well as your hypothesis and expectations.

Business value

In this section, you can tell your stakeholders why your research matters. If you base this research on team-level or product development goals, briefly touch on those.

Methodology

Share the research methods you used and why you chose those methods. Keep it concise and tailored to your audience. Your stakeholders probably don’t need to hear everything that went into your process.

Key learnings

This section will be the most substantial part of your report or presentation. Present your findings clearly and concisely. Share as much context as possible while keeping your target audience – your stakeholders – in mind.

Recommendations

In the last section of your report, make actionable recommendations for your stakeholders. Share possible solutions or answers to your research questions. Make your suggestions clear and consider any future research studies that you think would be helpful.

1. Define your audience

Most likely, you’ll already have conducted stakeholder interviews when you were planning your research. Taking those interviews into account, you should be able to glean what they’re expecting from your presentation.

Tailor your presentation to the types of findings that are most relevant, how those findings might affect their work and how they prefer to receive information. Only include information they will care about the most in a medium that’s easy for them to understand.

Do they have a technical understanding of what you’re doing or should you keep it a non-technical presentation? Make sure you keep the terminology and data on a level they can understand.

What part of the business do they work in? Executives will want to know about how it affects their business, while developers will want to know what technological changes they need to make.

2. Summarise

As briefly as possible, summarise your research goals, business value and methodology. You don’t need to go into too much detail for any of these items. Simply share the what, why and how of your research.

Answer these questions:

- What research questions did you use, and what was your hypothesis?

- What business decision will your research assist with?

- What methodology did you use?

You can briefly explain your methods to recruit participants, conduct interviews and analyse results. If you’d like more depth, link to interview plans, surveys, prototypes, etc.

3. Show key learnings

Your stakeholders will probably be pressed for time. They won’t be able to process raw data and they usually don’t want to see all of the work you’ve done. What they’re looking for are key insights that matter the most to them specifically. This is why it’s important to know your audience.

Summarise a few key points at the beginning of your report. The first thing they want to see are atomic research nuggets. Create condensed, high-priority bullet points that get immediate attention. This allows people to reference it quickly. Then, share relevant data or artefacts to illustrate your key learnings further.

Relevant data:

- Recurring trends and themes

- Relevant quotes that illustrate important findings

- Data visualisations

Relevant aspects of artefacts:

- Quotes from interviews

- User journey maps

- Affinity diagrams

- Storyboards

For most people you’ll present to, a summary of key insights will be enough. But, you can link to a searchable repository where they can dig deeper. You can include artefacts and tagged data for them to reference.

[GET CERTIFIED IN UX]

4. Share insights and recommendations

Offer actionable recommendations, not opinions. Share clear next steps that solve pain points or answer pending decisions. If you have any in mind, suggest future research options too. If users made specific recommendations, share direct quotes.

5. Choose a format

There are two ways you could share your findings in a presentation or a report. Let’s look at these two categories and see which might be the best fit for you.

Usually, a presentation is best for sharing data with a large group and when presenting to non-technical stakeholders. Presentations should be used for visual communication and when you only need to include relevant information in a brief summary.

A presentation is usually formatted in a:

- Case studies

- Atomic research nuggets

- Pre-recorded video

If you’re presenting to a smaller group, technical stakeholder or other researchers, you might want to use a report. This gives you the capacity to create a comprehensive record. Further, reports could be categorised based on their purpose as usability, analytics or market research reports.

A report is typically formatted in a:

- Notion or Confluence page

- Slack update

You might choose to write a report first, then create a presentation. After the presentation, you can share a more in-depth report. The report could also be used for records later.

1. Keep it engaging

When you’re presenting your findings, find ways to engage those you’re presenting to. You can ask them questions about their assumptions or what you’re presenting to get them more involved.

For example, “What do you predict were our findings when we asked users to test the usability of the menu?” or “What suggestions do you think users had for [a design problem]?”

If you don’t want to engage them with questions, try including alternative formats like videos, audio clips, visualisations or high-fidelity prototypes. Anything that’s interactive or different will help keep their engagement. They might engage with these items during or after your presentation.

Another way to keep it engaging is to tell a story throughout your presentation. Some UX researchers structure their presentations in the form of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey . Start in the middle with your research findings and then zoom out to your summary, insights and recommendations.

2. Combine qualitative and quantitative data

When possible, use qualitative data to back up quantitative data. For example, include a visualisation of poll results with a direct quote about that pain point.

Use this opportunity to show the value of the work you do and build empathy for your users. Translate your findings into a format that your stakeholders – designers, developers or executives – will be able to understand and act upon.

3. Make it actionable

Actionable presentations are engaging and they should have some business value . That means they need to solve a problem or at least move toward a solution to a problem. They might intend to optimise usability, find out more about the market or analyse user data.

Here are a few ways to make it actionable:

- Include a to-do list at the end

- Share your deck and repository files for future reference

- Recommend solutions for product or business decisions

- Suggest what kind of research should happen next (if any)

- Share answers to posed research questions

4. Keep it concise and effective

Make it easy for stakeholders to dive deeper if they want to but make it optional. Yes, this means including links to an easily searchable repository and keeping your report brief.

Humans tend to focus best on just 3-4 things at a time. So, limit your report to three or four major insights. Additionally, try to keep your presentation down to 20-30 minutes.

Remember, you don’t need to share everything you learned. In your presentation, you just need to show your stakeholders what they are looking for. Anything else can be sent later in your repository or a more detailed PDF report.

5. Admit the shortcomings of UX research

If you get pushback from stakeholders during your presentation, it’s okay to share your constraints.

Your stakeholders might not understand that your sample size is big enough or how you chose the users in your study or why you did something the way you did. While qualitative research might not be statistically significant, it’s usually representative of your larger audience and it’s okay to point that out.

Because they aren’t researchers, it’s your job to explain your methodology to them but also be upfront about the limitations UX research can pose. When all of your cards are on the table, stakeholders are more likely to trust you.

When it comes to presenting your UX research findings, keep it brief and engaging. Provide depth with external resources after your presentation. This is how you get stakeholders to find empathy for your users. This is how you master the art of UX.

Need to go back to the basics and learn more about UX research? Dive into these articles:

What is UX research? The 9 best UX research tools to use in 2022

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the best UX insights and career advice direct to your inbox each month.

Thanks for subscribing to our newsletter

You'll now get the best career advice, industry insights and UX community content, direct to your inbox every month.

Upcoming courses

Professional diploma in ux design.

Learn the full UX process, from research to design to prototyping.

Professional Certificate in UI Design

Master key concepts and techniques of UI design.

Certificate in Software and Coding Fundamentals for UX

Collaborate effectively with software developers.

Certificate in UX Design Fundamentals

Get a comprehensive introduction to UX design.

Professional Certificate in Content Design

Learn the skills you need to start a career in content design.

Professional Certificate in User Research

Master the research skills that make UX professionals so valuable.

Upcoming course

Build your UX career with a globally-recognised, industry-approved certification. Get the mindset, the skills and the confidence of UX designers.

You may also like

What are the Gestalt principles and how do designers use them

The 9 best UI design courses to consider in 2024

The importance of ethnography in user research

Build your UX career with a globally recognised, industry-approved qualification. Get the mindset, the confidence and the skills that make UX designers so valuable.

5 November 2024

Integrations

What's new?

In-Product Prompts

Participant Management

Interview Studies

Prototype Testing

Card Sorting

Tree Testing

Live Website Testing

Automated Reports

Templates Gallery

Choose from our library of pre-built mazes to copy, customize, and share with your own users

Browse all templates

Financial Services

Tech & Software

Product Designers

Product Managers

User Researchers

By use case

Concept & Idea Validation

Wireframe & Usability Test

Content & Copy Testing

Feedback & Satisfaction

Content Hub

Educational resources for product, research and design teams

Explore all resources

Question Bank

Maze Research Success Hub

Guides & Reports

Help Center

Future of User Research Report

The Optimal Path Podcast

User Research

Jul 23, 2024 • 13 minutes read

How to write clear UX research objectives that define research direction (+ 20 examples)

Clear and effective UX research objectives are the starting point of successful studies. Here's what separates good from bad, plus 20 examples to learn from.

Armin Tanovic

Conducting a UX research study helps get feedback on your user’s pain points, expectations, and needs. The insights you collect inform your design decisions, ultimately helping you provide better user experiences.

But before it all begins, you need a solid UX research objective. These specific goals outline the direction for your entire research project; UX research objectives are the north star of any research study—guiding your project toward game-changing insights.

In this article, we’ll cover 20 examples of UX research objectives and explain how to write your own, to set your UX research project up for success.

Exceed your UX research goals with Maze

Maze’s comprehensive suite of UX research methods help you test designs, analyze feedback, and uncover user insights to transform your entire product design process.

Why do you need UX research objectives?

A UX research objective is an overarching goal you set to define the purpose of your UX research study. It determines the direction of your entire UX research project and enables you to choose the best UX research methods for collecting insights .

They also ultimately serve as guidelines and a benchmark for success, enabling you to track your progress and measure the impact of your UX research .

UX research objectives help you:

- Focus your research efforts: A specific objective helps you and your team focus on specific tasks and methods that collect relevant feedback from your users

- Align team members and stakeholders: Use your objective to ensure stakeholders and team members are all on the same page, setting the stage for seamless collaboration across multiple departments

- Allocate resources efficiently: Your objective allows you to allocate time, budget, and personnel while prioritizing tasks that lead directly to project success

- Inform success criteria: With a clear research objective, you define what success looks like, outline metrics to track and KPIs to focus on

What makes a good UX research objective (and a bad one)?

A good UX research objective guides your UX research efforts with a clear definition of what you want to achieve, why you want to achieve it, and what success looks like. Good research objectives should follow the SMART framework:

- Specific: Your objective should be clear and precise enough to guide research without ambiguity

- Measurable: You should be able to measure your objective’s success in one way or another, whether that’s during the research phase or any other phase of the UX design and development phase

- Achievable: It must be realistically possible for you to achieve your objectives with the time, resources, and research methods you have available to you

- Relevant: It should be closely tied into your user’s overall goals and your business objectives

- Time-bound: You need to be able to put some form of time frame on the objective if necessary (even if that’s implicit)

An example of a SMART UX research objective:

✅ “Evaluate onboarding usability and increase onboarding task completion to 70% over a period of three months.”

This is an objective you can work toward. It has a clear purpose, measurement criteria, and timeline. Bad UX research objectives, however, fail to set a direction for your UX research project. They’re broad, unspecific, and vague , such as:

❌ “Improve the onboarding process for users”

You see? With the first objective, you know exactly what you intend to accomplish through UX research. Perhaps you can already visualize which methods to use, like UX surveys or usability testing .

Option one is a strong UX research objective because it points you in a specific direction. Option two, on the other hand, fails to define boundaries for your UX research project. It doesn’t outline a specific direction or intent that enables you to evaluate the success of your study.

20 Examples of UX research objectives to suit each stage of the product development process

Let’s say you’re designing an e-commerce platform. Your UX objectives will look different depending on where you are in the design process .

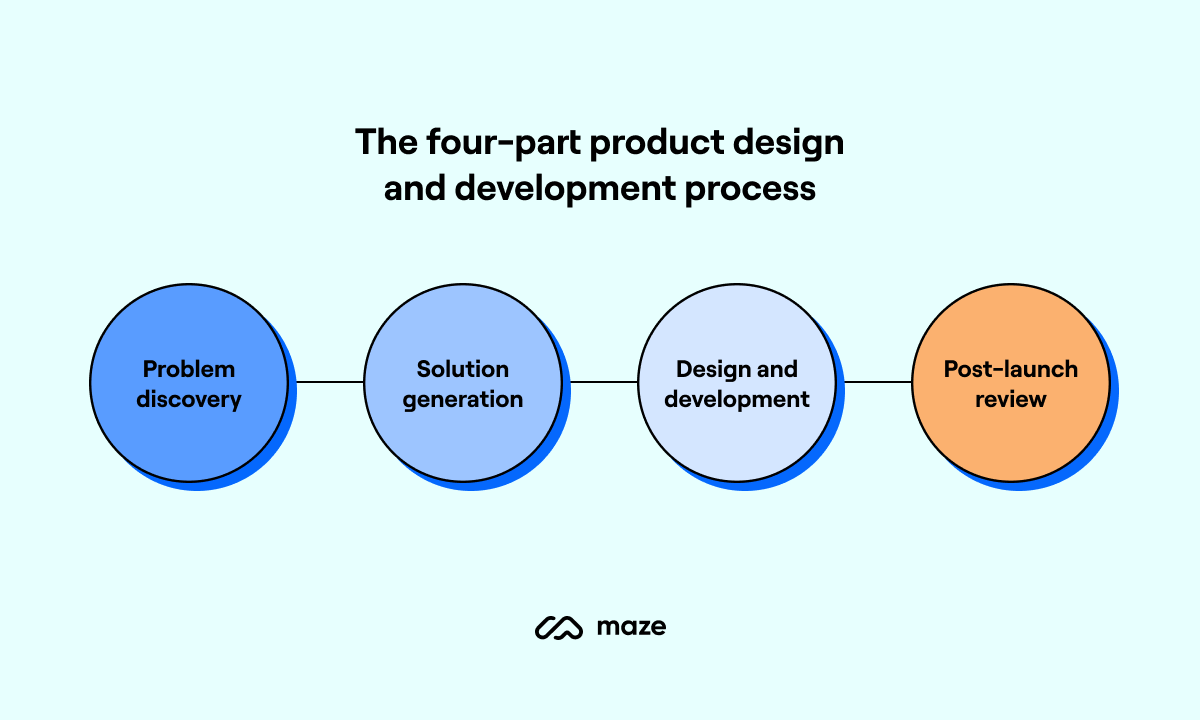

To help you create effective objectives for your specific phase, we’ve distilled the design and product development process down into four clear phases, and provided five examples for each stage.

Just to say—these examples don’t always include specific metrics to track, or timelines for the research, as these elements of a SMART goal are very individual to each project.

The product design and development process

5 Example UX research objectives for the problem discovery phase

In the problem discovery phase, you’re looking to conduct generative research to uncover the pain points and problems users have when using your product. This could be anything from issues navigating the interface, to missing features that would help users achieve their specific goals.

Potential UX research objective examples are:

- Create three personas that represent our users and their problems

- Uncover what usability problems users have while interacting with our product

- Map out the user journey from sign up to the aha! moment

- Investigate if users have problems navigating our product’s onboarding process

- Identify specific drop-off points within the user journey

⚙️ Need a tool to help achieve your research objectives during problem discovery research sessions? Maze’s Interview Studies and Feedback Surveys are a great way to collect qualitative and quantitative data to identify user issues and pain points to inform your research objectives.

5 Example UX research objectives for the solution generation phase

Once you know what issues users have with your product, you still need to understand the root causes, what users expect from solutions, and how you can introduce a solution that optimizes the experience.

Here, you need to propose specific design solutions that could potentially smooth out interactions and eliminate friction points throughout the user journey.

Going back to our e-commerce example, potential UX research objective examples are:

- Understand what specific usability issues might be causing customer drop-off at the checkout phase

- Establish what users expect from their user profile management experience

- Gauge user interest in a profile dashboard to help users better navigate their profile page

- Investigate if personalization could make the website more intuitive for users

- Explore potential solutions for users who abandon their shopping carts during the checkout phase in the user journey

5 Example UX research objectives for the design and development phase

During this phase, you’re designing and developing the proposed solution you generated during the previous step. But before these solutions go live, you need to test if they adequately solve user problems as you anticipated.

This typically involves creating and testing a prototype . Some UX research objectives during the design and development phase include:

- Establish if users can complete tasks with the lo-fi prototype design of the proposed solution

- Understand which of two dashboard wireframes is more intuitive to existing users

- Validate the information architecture of your design prototype

- Uncover if users have any usability issues with our proposed design

- Evaluate new feature interest to prioritize development initiatives

5 Example UX research objectives for the post-launch phase

UX research is an iterative, continuous process. There’s no start or finish, it’s a cycle that continually repeats. Once you design, develop, and launch a new product, feature, or experience—you need to research its impact. Setting post-launch UX research objectives measures if your UX research process was a success. Five of these objectives could be:

- Establish if we’ve solved core usability problems for users with the new feature

- Understand if users are more satisfied with their overall experience since introducing the new feature

- Evaluate user satisfaction with the updated interface’s usability

- Identify the impact our new feature had on user engagement and conversion rates

- Determine if our initial hypothesis was correct e.g. the solution will increase customer retention

⚙️ Looking for a tool to help hit your UX research objectives post-launch? Maze’s Live Website Testing and In-Product Prompt are purpose-built to help you gather real-time user insights.

How to write clear and effective research objectives: 4 Best practices

Writing your own UX research objective can be daunting. After all, it serves as the foundation for your entire UX research project. A wrong objective is a missed opportunity to start your UX research strong and guide your research team, resources, and efforts in the direction of actionable insights. That’s why we’ve outlined steps and best practices to help you get it right.

Begin by assessing both user and stakeholder needs. Use reviews, user personas , results from past UX projects or your UX research repository to identify the most pressing concerns for your users. Then, balance them with your stakeholders’ wider business goals . Finally, write what you intend to uncover through your next project, based on user needs and stakeholder goals.

To ensure your UX research objectives are as effective as can be, follow these four best practices.

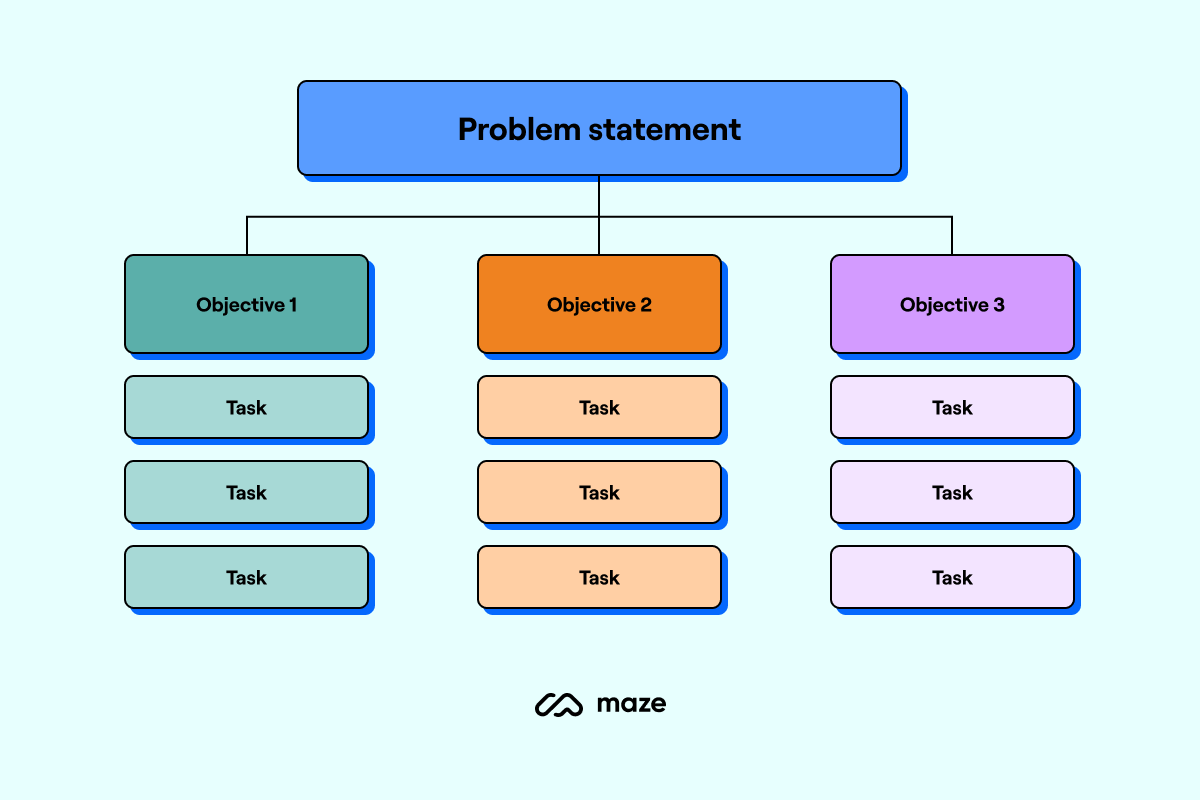

1. Start with a problem statement

Having trouble defining your project’s objective? Start with a problem statement instead. These should clearly define the issues your users are having—they identify and call out pain points, enabling you to get a better idea of what your objectives should be.

This will not only help you think of objectives, but help you organize your team further and delegate tasks.

For example, a problem statement could be “Users are having trouble navigating their customer profile pages” From there, your objective may become “Uncover specific usability and navigation issues with design elements on the profile page.”

A problem statement helps inform your research objectives and research questions by highlighting the overall issue you’re looking to solve.

2. Make UX research objectives actionable

One thing that all strong UX research objectives share is their actionability. Your objective should be active, defining what you want to achieve from the very start of the sentence.

Doing so ties it to a tangible outcome, helping you clarify what you want while pointing your efforts in the right direction.

Here are some actionable ways to start your UX research objectives:

- Evaluate the usability of…

- Identify user friction points throughout…

- Measure increases in…

- Compare satisfaction between…

- Explore potential solutions for…

- Understand how users approach…

- Assess if users…

Starting your objective with a command helps structure your objective from the get-go.

3. Use only one to three objectives per study

Write too many objectives, and you risk being able to focus on none—ultimately putting your project’s success at risk.

While branching out your efforts is beneficial for more complex studies, having too many objectives can result in spreading your resources too thin.

One to three objectives per study is a good rule of thumb. This range ensures you maintain clarity and focus throughout your project—the whole reason you're writing UX research objectives in the first place.

Make sure that the objectives of your research project are connected in scope and theme, too. If you’re using more than one objective, each should allow you to hone in on a specific issue from multiple angles, not explore three different issues. With the above example, a group of three objectives might look like:

- “Assess the ease of navigation and efficiency of the search functionality on user’s profile pages.”

- “Understand how users prefer to view products and settings on their profile pages.”

- “Evaluate the effectiveness of the product dashboard on user profile pages.”

4. Ask stakeholders and team members for feedback

With your freshly-written UX research objectives, you’re probably excited to get started on your UX research. However, you still need to get feedback from stakeholders and team members. Doing so helps you identify:

- The relevance of your outlined objective

- Potential roadblocks during later phases of your UX research project

- How well your objectives align with wider business goals

You might need to refine your UX research objectives based on the feedback you receive. For example, stakeholders might raise concerns about your objective’s feasibility or question if it can help achieve wider business goals like reducing churn or increasing retention. Don’t be afraid to revisit and rework your objectives until everyone’s aligned. This will lead to a stronger result overall.

Achieve your UX research objectives with Maze

UX research objectives are the starting point for a fully-fledged UX research plan . From there, you can begin your project, test with real users, and get the insights you need for designing user-centered products .

Given you have the right tool, that is.

Maze is a leading user research platform that makes the process easy. Choose from a wide range of moderated and unmoderated UX research methods and get shareable insights with automated reporting features that make presenting your findings to stakeholders a breeze.

Frequently asked questions about UX research objectives

How do you write a user research plan in UX?

A UX research plan is a systematic roadmap for organizing your UX research efforts. To create one, you need to outline:

- Research methodologies

- Participants

- Deliverables

What is an example of a research goal in UX?

An example of a research goal in UX would be “identify navigation issues for the checkout process on our new e-commerce app.”

What is the purpose of UX research?

UX research aims to understand user behaviors, needs, and preferences to inform the product design process and improve user experience. Through user research methods, organizations can uncover insights that help them create more intuitive, relevant, and successful products.

What’s the difference between UX research objectives and UX research goals?

UX research objectives and UX research goals are generally interchangeable terms but often differ in the level of specificity and detail. UX research objectives are more specific, measurable, and actionable, often supporting broader goals. UX research goals, on the other hand, are broad, often general statements that state what UX research aims to achieve.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Formulating a UX research hypothesis helps guide your UX research project in the right direction, collect insights, and evaluate not only whether an idea is worth pursuing, but how to go after it.

Design Hypothesis is a process of creating a hypothesis or assumption about how a specific design change can improve a product/campaign’s performance. It involves collecting data, generating ideas, …

A design hypothesis is a cornerstone of the UX and UI design process. It guides the entire process, defines research needs, and heavily influences the final outcome. Doing any design work without a well-defined …

Learn to create a solid UX research hypothesis with UserTesting's 5 rules. Ensure your hypotheses are specific, measurable, and repeatable. | UserTesting Resources

Get the mindset, the confidence and the skills that make UX designers so valuable. In this complete guide to presenting UX research findings, we’ll cover what you should include in a UX research report, how to present …

Clear and effective UX research objectives are the starting point of successful studies. Here's what separates good from bad, plus 20 examples to learn from. Writer. Conducting a UX research study helps get feedback on …