Chapter 8: Making Academic Arguments

8.3 Types of Evidence in Academic Arguments

Robin Jeffrey and Yvonne Bruce

All academic writers use evidence to support their claims. However, different writing tasks in different fields require different types of evidence. Often, a combination of different types of evidence is required in order to adequately support and develop a point. Evidence is not simply “facts.” Evidence is not simply “quotes.”

Evidence is what a writer uses to support or defend his or her argument, and only valid and credible evidence is enough to make an argument strong.

For a review of what evidence means in terms of developing body paragraphs within an essay, you can refer back to Section 4.3 .

As you develop your research-supported essay, consider not only what types of evidence might support your ideas but also what types of evidence will be considered valid or credible according to the academic discipline or academic audience for which you are writing.

Evidence in the Humanities: Literature, Art, Film, Music, Philosophy

- Scholarly essays that analyze original works

- Details from an image, a film, or other work of art

- Passages from a musical composition

- Passages of text, including poetry

Evidence in the Humanities: History

- Primary Sources (photos, letters, maps, official documents, etc.)

- Other books or articles that interpret primary sources or other evidence.

Evidence in the Social Sciences: Psychology, Sociology, Political Science, Anthropology

- Books or articles that interpret data and results from other people’s original experiments or studies.

- Results from one’s own field research (including interviews, surveys, observations, etc.)

- Data from one’s own experiments

- Statistics derived from large studies

Evidence in the Sciences: Biology, Chemistry, Physics

- Data from the author of the paper’s own experiments

What remains consistent no matter the discipline in which you are writing, however, is that “evidence” NEVER speaks for itself—you must integrate it into your own argument or claim and demonstrate that the evidence supports your thesis. In addition, be alert to evidence that seems to contradict your claims or offers a counterargument to it: rebutting that counterargument can be powerful evidence for your claim. You can also make evidence that isn’t there an integral part of your argument, too. If you can’t find the evidence you think you need, ask yourself why it seems to be lacking, or if its absence adds a new dimension to your thinking about the topic. Remember, evidence is not the piling up of facts or quotes: evidence is only one component of a strong, well supported, well argued, and well written composition.

8.3 Types of Evidence in Academic Arguments by Robin Jeffrey and Yvonne Bruce is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

6 Types of Evidence in Writing

Writing an essay is a lot like participating in a debate. You have a main point that you want to make, and you need to support it. So, the question is: how do you support your main point?

The best way is to provide evidence.

Evidence can come from many sources and take many forms, but generally speaking, there are six types of evidence.

Each type of evidence may carry more weight than others. Choosing which type of evidence to use depends on the purpose of the essay and the audience.

For example, for essays in psychology or sociology that will be read by professors, evidence from research papers and statistics will be suitable, and expected.

However, if writing for the general public, evidence in the form of quotes from experts or testimonials from people involved in the subject may be more effective.

Ideally, it is good to have a mix of the different types of evidence so that the essay is well-rounded.

Using various types of evidence also shows the reader that you have researched the topic thoroughly. That will add credibility to the essay as a whole and instill an impression that the author is competent and trustworthy.

Here is a brief description of the six main types of evidence.

You Might Also Like: Transition Words for Providing Evidence in Essays

Types of Evidence in Writing

1. anecdotal evidence.

Anecdotal evidence comes from personal experience. It can involve a story about something that happened to you, or an observation you made about friends, relatives, or other people.

An informal interview with someone affected by the topic you are writing about is also a form of anecdotal evidence. That interview may have been conducted by the author of the essay or presented on a news program.

Although it is not considered very strong evidence, it does have a purpose. Describing a personal experience early in the essay can help establish context, show relevance of the subject, or be a way to build a connection with the audience.

In some cases, anecdotal evidence can be quite effective. It can reveal deeply personal or emotional elements of a phenomenon that are very compelling. Not all essays need to be full of scientific references and statistics to be effective at making a point.

See More: 19 Anecdotal Evidence Examples

2. Testimonial Evidence

Offering the opinion of an expert is referred to as testimonial evidence. Their opinion can come from an interview or quote from a book or paper they authored.

The words of someone who is considered an expert in a subject can provide a lot of support to the point you are trying to make. It adds strength and shows that what you are saying is not just your opinion, but is also the opinion of someone that is recognized and respected in the subject.

If that expert has an advanced degree from a notable university, such as Princeton or Stanford, then make sure the reader knows that. Similarly, if they are the president or director of an institution that is heavily involved in the subject, then be sure to include those credentials as well.

If your essay is for an academic course, use proper citation. This often involves indicating the year of the quote, where it was published, and the page number where the quote comes from.

Finally, if quoting an expert, choose the quote carefully. Experts sometimes use language that is overly complex or contains jargon that many readers may not understand. Limiting the quote to 1 or 2 sentences is also a good idea.

3. Statistical Evidence

Statistical evidence involves presenting numbers that support your point. Statistics can be used to demonstrate the prevalence and seriousness of a phenomenon.

When used early in the essay, it informs the reader as to how important the topic is and can be an effective way to get the reader’s attention.

For example, citing the number of people that die each year because they weren’t wearing a seat belt, or the number of children suffering from malnutrition, tells the reader that the topic is serious.

In addition to stating statistics in the body of the essay, including a graph or two will help make the point easier to understand. A picture can be worth a thousand words also applies to graphs and charts.

Graphs and charts also create a sense of credibility and add an extra punch of strength to your arguments.

Statistics can also be used to counter common misconceptions. This is a good way to clear the air right away regarding an issue that may not be well understood or in which there has been a lot of misinformation presented previously.

When presenting statistics, establish credibility by citing the source. Make sure that source is reputable. Scientific publications or well-respected organizations such as the CDC are good examples.

If your essay is for an academic assignment, then be sure to follow the publication guidelines for that discipline. Papers in business, sociology, and law have different rules for how to cite sources.

As persuasive as statistics can be, beware that many readers may be suspicious. There is a belief among some people that statistics are often faked or manipulated. This is due, in part, to many people not understanding the peer-review process that occurs before scientific papers are published.

4. Textual Evidence

Textual evidence comes directly from a source document. This could be a literary work or historical document. It is frequently used in an argumentative essay or as part of a compare-and-contrast type of academic assignment.

For example, if conducting a character analysis of a character in a novel, then identifying key sentences that provide examples of their personality will help support your analysis.

There are several ways of incorporating textual evidence: quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing.

Quoting statements from the character themselves can be used to demonstrate their thought processes or personality flaws. Likewise, using the words of the author that describe the character will add support to your premise.

Paraphrasing involves conveying the points in the source document by using your own words. There is usually a degree of correspondence between the amount of text in the document and the paraphrased version. In other words, if your paraphrased version is longer than the section in the source document, then you should try again.

Summarizing involves condensing the text in the source document to its main points and highlighting the key takeaways you want the reader to focus on.

5. Analogical Evidence

An analogy is an example of a situation, but presented in a different context. Using an analogy is a great way to explain a complicated issue that is simpler and easier to digest.

Medical doctors often use analogies to describe health-related issues. For example, they might say that getting a yearly medical exam from your primary physician is like taking your car to the mechanic once a year to make sure everything is running okay.

One rule of thumb about analogies is that the simpler they are, the more easily understood. The analogy should have a degree of similarity with the issue being discussed, but, at the same time, be a bit different as well. Sorry about that; it’s a balance.

Be careful not to use an analogy that is too far-fetched. For example, comparing the human body to the universe is too much of a stretch. This might confuse the reader, make them feel frustrated because they don’t see the connection, and/or cause them to lose interest.

6. Hypothetical Evidence

Hypothetical evidence is presenting the reader with a “what if” kind of scenario. This is a great way to get the reader to consider possibilities that they may not have thought of previously.

One way to present a hypothetical is to pair it with a credible statistic. Ask the reader to consider what might happen in the context of those numbers.

Another strategy is to restate one of your arguments, and then present a hypothetical that aligns with that point. For example, if what you are saying is true, then X, Y, and Z may occur.

By providing a concrete hypothetical scenario, people can imagine what could happen. Opening a person’s mindset can be the first step towards an effective and persuasive essay.

There are many examples in history of phenomenon that people never thought possible, but later turned out to materialize. For example, climate change.

In the early days of climate science, the evidence was not readily available to a convincing degree to persuade the general public. However, extrapolating into the future through the use of hypotheticals can help people consider the possibility of fossil fuels causing climate crises.

The emotional dynamics activated when thinking about the future can help open some people’s eyes to different possibilities and generate concern. If only this had happened about 50 years ago.

Providing evidence for your main point in an essay can make it effective and persuasive. There are many types of evidence, and each one varies in terms of its strength and pertinence to the purpose of the essay.

In some situations, for example, anecdotal evidence and testimonials are sufficient to get a reader’s attention. In other situations, however, such as essays in the sciences, the reader will expect to see more than just opinions of the author.

Presenting statistics from reputable sources can add a lot of strength to an essay. While a lot of people are convinced by numbers, others are not.

Using quotes, either from experts or from a source document, are also effective ways to add support to the essay’s main point.

Analogies will help the reader understand a complex topic, while hypotheticals can be an effective way to get people to extend their thinking and consider what could happen if…

Incorporating several types of evidence is best. If all arguments in an essay only come from the author, it can come across as flimsy. A chair with three legs is better than a chair with two.

Bailey, S. (2003). Academic writing: A practical guide for students . Cheltenham, U.K.: Nelson Thornes Ltd.

Redman, P., & Maples, W. (2017). Good essay writing: A social sciences guide . Sage.

Savage, A., & Mayer, P. (2006). Effective academic writing: The short essay . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starkey, L. B. (2004). How to write great essays . Learning Express.

Warburton, N. (2020). The basics of essay writing . Routledge.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Forest Schools Philosophy & Curriculum, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori's 4 Planes of Development, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori vs Reggio Emilia vs Steiner-Waldorf vs Froebel

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Parten’s 6 Stages of Play in Childhood, Explained!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Using Research and Evidence

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What type of evidence should I use?

There are two types of evidence.

First hand research is research you have conducted yourself such as interviews, experiments, surveys, or personal experience and anecdotes.

Second hand research is research you are getting from various texts that has been supplied and compiled by others such as books, periodicals, and Web sites.

Regardless of what type of sources you use, they must be credible. In other words, your sources must be reliable, accurate, and trustworthy.

How do I know if a source is credible?

You can ask the following questions to determine if a source is credible.

Who is the author? Credible sources are written by authors respected in their fields of study. Responsible, credible authors will cite their sources so that you can check the accuracy of and support for what they've written. (This is also a good way to find more sources for your own research.)

How recent is the source? The choice to seek recent sources depends on your topic. While sources on the American Civil War may be decades old and still contain accurate information, sources on information technologies, or other areas that are experiencing rapid changes, need to be much more current.

What is the author's purpose? When deciding which sources to use, you should take the purpose or point of view of the author into consideration. Is the author presenting a neutral, objective view of a topic? Or is the author advocating one specific view of a topic? Who is funding the research or writing of this source? A source written from a particular point of view may be credible; however, you need to be careful that your sources don't limit your coverage of a topic to one side of a debate.

What type of sources does your audience value? If you are writing for a professional or academic audience, they may value peer-reviewed journals as the most credible sources of information. If you are writing for a group of residents in your hometown, they might be more comfortable with mainstream sources, such as Time or Newsweek . A younger audience may be more accepting of information found on the Internet than an older audience might be.

Be especially careful when evaluating Internet sources! Never use Web sites where an author cannot be determined, unless the site is associated with a reputable institution such as a respected university, a credible media outlet, government program or department, or well-known non-governmental organizations. Beware of using sites like Wikipedia , which are collaboratively developed by users. Because anyone can add or change content, the validity of information on such sites may not meet the standards for academic research.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

Using evidence.

Like a lawyer in a jury trial, a writer must convince her audience of the validity of her argument by using evidence effectively. As a writer, you must also use evidence to persuade your readers to accept your claims. But how do you use evidence to your advantage? By leading your reader through your reasoning.

The types of evidence you use change from discipline to discipline--you might use quotations from a poem or a literary critic, for example, in a literature paper; you might use data from an experiment in a lab report.

The process of putting together your argument is called analysis --it interprets evidence in order to support, test, and/or refine a claim . The chief claim in an analytical essay is called the thesis . A thesis provides the controlling idea for a paper and should be original (that is, not completely obvious), assertive, and arguable. A strong thesis also requires solid evidence to support and develop it because without evidence, a claim is merely an unsubstantiated idea or opinion.

This Web page will cover these basic issues (you can click or scroll down to a particular topic):

- Incorporating evidence effectively.

- Integrating quotations smoothly.

- Citing your sources.

Incorporating Evidence Into Your Essay

When should you incorporate evidence.

Once you have formulated your claim, your thesis (see the WTS pamphlet, " How to Write a Thesis Statement ," for ideas and tips), you should use evidence to help strengthen your thesis and any assertion you make that relates to your thesis. Here are some ways to work evidence into your writing:

- Offer evidence that agrees with your stance up to a point, then add to it with ideas of your own.

- Present evidence that contradicts your stance, and then argue against (refute) that evidence and therefore strengthen your position.

- Use sources against each other, as if they were experts on a panel discussing your proposition.

- Use quotations to support your assertion, not merely to state or restate your claim.

Weak and Strong Uses of Evidence

In order to use evidence effectively, you need to integrate it smoothly into your essay by following this pattern:

- State your claim.

- Give your evidence, remembering to relate it to the claim.

- Comment on the evidence to show how it supports the claim.

To see the differences between strong and weak uses of evidence, here are two paragraphs.

Weak use of evidence

Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This is a weak example of evidence because the evidence is not related to the claim. What does the claim about self-centeredness have to do with families eating together? The writer doesn't explain the connection.

The same evidence can be used to support the same claim, but only with the addition of a clear connection between claim and evidence, and some analysis of the evidence cited.

Stronger use of evidence

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

This is a far better example, as the evidence is more smoothly integrated into the text, the link between the claim and the evidence is strengthened, and the evidence itself is analyzed to provide support for the claim.

Using Quotations: A Special Type of Evidence

One effective way to support your claim is to use quotations. However, because quotations involve someone else's words, you need to take special care to integrate this kind of evidence into your essay. Here are two examples using quotations, one less effective and one more so.

Ineffective Use of Quotation

Today, we are too self-centered. "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This example is ineffective because the quotation is not integrated with the writer's ideas. Notice how the writer has dropped the quotation into the paragraph without making any connection between it and the claim. Furthermore, she has not discussed the quotation's significance, which makes it difficult for the reader to see the relationship between the evidence and the writer's point.

A More Effective Use of Quotation

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much any more as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence, as James Gleick says in his book, Faster . "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

The second example is more effective because it follows the guidelines for incorporating evidence into an essay. Notice, too, that it uses a lead-in phrase (". . . as James Gleick says in his book, Faster ") to introduce the direct quotation. This lead-in phrase helps to integrate the quotation with the writer's ideas. Also notice that the writer discusses and comments upon the quotation immediately afterwards, which allows the reader to see the quotation's connection to the writer's point.

REMEMBER: Discussing the significance of your evidence develops and expands your paper!

Citing Your Sources

Evidence appears in essays in the form of quotations and paraphrasing. Both forms of evidence must be cited in your text. Citing evidence means distinguishing other writers' information from your own ideas and giving credit to your sources. There are plenty of general ways to do citations. Note both the lead-in phrases and the punctuation (except the brackets) in the following examples:

Quoting: According to Source X, "[direct quotation]" ([date or page #]).

Paraphrasing: Although Source Z argues that [his/her point in your own words], a better way to view the issue is [your own point] ([citation]).

Summarizing: In her book, Source P's main points are Q, R, and S [citation].

Your job during the course of your essay is to persuade your readers that your claims are feasible and are the most effective way of interpreting the evidence.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Revising Your Paper

- Have I offered my reader evidence to substantiate each assertion I make in my paper?

- Do I thoroughly explain why/how my evidence backs up my ideas?

- Do I avoid generalizing in my paper by specifically explaining how my evidence is representative?

- Do I provide evidence that not only confirms but also qualifies my paper's main claims?

- Do I use evidence to test and evolve my ideas, rather than to just confirm them?

- Do I cite my sources thoroughly and correctly?

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

Systematic Reviews

- Levels of Evidence

- Evidence Pyramid

- Joanna Briggs Institute

The evidence pyramid is often used to illustrate the development of evidence. At the base of the pyramid is animal research and laboratory studies – this is where ideas are first developed. As you progress up the pyramid the amount of information available decreases in volume, but increases in relevance to the clinical setting.

Meta Analysis – systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

Systematic Review – summary of the medical literature that uses explicit methods to perform a comprehensive literature search and critical appraisal of individual studies and that uses appropriate st atistical techniques to combine these valid studies.

Randomized Controlled Trial – Participants are randomly allocated into an experimental group or a control group and followed over time for the variables/outcomes of interest.

Cohort Study – Involves identification of two groups (cohorts) of patients, one which received the exposure of interest, and one which did not, and following these cohorts forward for the outcome of interest.

Case Control Study – study which involves identifying patients who have the outcome of interest (cases) and patients without the same outcome (controls), and looking back to see if they had the exposure of interest.

Case Series – report on a series of patients with an outcome of interest. No control group is involved.

- Levels of Evidence from The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

- The JBI Model of Evidence Based Healthcare

- How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence From the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia. Book must be downloaded; not available to read online.

When searching for evidence to answer clinical questions, aim to identify the highest level of available evidence. Evidence hierarchies can help you strategically identify which resources to use for finding evidence, as well as which search results are most likely to be "best".

Image source: Evidence-Based Practice: Study Design from Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives. This work is licensed under a Creativ e Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

The hierarchy of evidence (also known as the evidence-based pyramid) is depicted as a triangular representation of the levels of evidence with the strongest evidence at the top which progresses down through evidence with decreasing strength. At the top of the pyramid are research syntheses, such as Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews, the strongest forms of evidence. Below research syntheses are primary research studies progressing from experimental studies, such as Randomized Controlled Trials, to observational studies, such as Cohort Studies, Case-Control Studies, Cross-Sectional Studies, Case Series, and Case Reports. Non-Human Animal Studies and Laboratory Studies occupy the lowest level of evidence at the base of the pyramid.

- Finding Evidence-Based Answers to Clinical Questions – Quickly & Effectively A tip sheet from the health sciences librarians at UC Davis Libraries to help you get started with selecting resources for finding evidence, based on type of question.

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review?

- Next: Locating Systematic Reviews >>

- Getting Started

- What is a Systematic Review?

- Locating Systematic Reviews

- Searching Systematically

- Developing Answerable Questions

- Identifying Synonyms & Related Terms

- Using Truncation and Wildcards

- Identifying Search Limits/Exclusion Criteria

- Keyword vs. Subject Searching

- Where to Search

- Search Filters

- Sensitivity vs. Precision

- Core Databases

- Other Databases

- Clinical Trial Registries

- Conference Presentations

- Databases Indexing Grey Literature

- Web Searching

- Handsearching

- Citation Indexes

- Documenting the Search Process

- Managing your Review

Research Support

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucdavis.edu/systematic-reviews

- Library databases

- Library website

Evidence-Based Research: Levels of Evidence Pyramid

Introduction.

One way to organize the different types of evidence involved in evidence-based practice research is the levels of evidence pyramid. The pyramid includes a variety of evidence types and levels.

- systematic reviews

- critically-appraised topics

- critically-appraised individual articles

- randomized controlled trials

- cohort studies

- case-controlled studies, case series, and case reports

- Background information, expert opinion

Levels of evidence pyramid

The levels of evidence pyramid provides a way to visualize both the quality of evidence and the amount of evidence available. For example, systematic reviews are at the top of the pyramid, meaning they are both the highest level of evidence and the least common. As you go down the pyramid, the amount of evidence will increase as the quality of the evidence decreases.

Text alternative for Levels of Evidence Pyramid diagram

EBM Pyramid and EBM Page Generator, copyright 2006 Trustees of Dartmouth College and Yale University. All Rights Reserved. Produced by Jan Glover, David Izzo, Karen Odato and Lei Wang.

Filtered Resources

Filtered resources appraise the quality of studies and often make recommendations for practice. The main types of filtered resources in evidence-based practice are:

Scroll down the page to the Systematic reviews , Critically-appraised topics , and Critically-appraised individual articles sections for links to resources where you can find each of these types of filtered information.

Systematic reviews

Authors of a systematic review ask a specific clinical question, perform a comprehensive literature review, eliminate the poorly done studies, and attempt to make practice recommendations based on the well-done studies. Systematic reviews include only experimental, or quantitative, studies, and often include only randomized controlled trials.

You can find systematic reviews in these filtered databases :

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Cochrane systematic reviews are considered the gold standard for systematic reviews. This database contains both systematic reviews and review protocols. To find only systematic reviews, select Cochrane Reviews in the Document Type box.

- JBI EBP Database (formerly Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database) This database includes systematic reviews, evidence summaries, and best practice information sheets. To find only systematic reviews, click on Limits and then select Systematic Reviews in the Publication Types box. To see how to use the limit and find full text, please see our Joanna Briggs Institute Search Help page .

You can also find systematic reviews in this unfiltered database :

To learn more about finding systematic reviews, please see our guide:

- Filtered Resources: Systematic Reviews

Critically-appraised topics

Authors of critically-appraised topics evaluate and synthesize multiple research studies. Critically-appraised topics are like short systematic reviews focused on a particular topic.

You can find critically-appraised topics in these resources:

- Annual Reviews This collection offers comprehensive, timely collections of critical reviews written by leading scientists. To find reviews on your topic, use the search box in the upper-right corner.

- Guideline Central This free database offers quick-reference guideline summaries organized by a new non-profit initiative which will aim to fill the gap left by the sudden closure of AHRQ’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC).

- JBI EBP Database (formerly Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database) To find critically-appraised topics in JBI, click on Limits and then select Evidence Summaries from the Publication Types box. To see how to use the limit and find full text, please see our Joanna Briggs Institute Search Help page .

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Evidence-based recommendations for health and care in England.

- Filtered Resources: Critically-Appraised Topics

Critically-appraised individual articles

Authors of critically-appraised individual articles evaluate and synopsize individual research studies.

You can find critically-appraised individual articles in these resources:

- EvidenceAlerts Quality articles from over 120 clinical journals are selected by research staff and then rated for clinical relevance and interest by an international group of physicians. Note: You must create a free account to search EvidenceAlerts.

- ACP Journal Club This journal publishes reviews of research on the care of adults and adolescents. You can either browse this journal or use the Search within this publication feature.

- Evidence-Based Nursing This journal reviews research studies that are relevant to best nursing practice. You can either browse individual issues or use the search box in the upper-right corner.

To learn more about finding critically-appraised individual articles, please see our guide:

- Filtered Resources: Critically-Appraised Individual Articles

Unfiltered resources

You may not always be able to find information on your topic in the filtered literature. When this happens, you'll need to search the primary or unfiltered literature. Keep in mind that with unfiltered resources, you take on the role of reviewing what you find to make sure it is valid and reliable.

Note: You can also find systematic reviews and other filtered resources in these unfiltered databases.

The Levels of Evidence Pyramid includes unfiltered study types in this order of evidence from higher to lower:

You can search for each of these types of evidence in the following databases:

TRIP database

Background information & expert opinion.

Background information and expert opinions are not necessarily backed by research studies. They include point-of-care resources, textbooks, conference proceedings, etc.

- Family Physicians Inquiries Network: Clinical Inquiries Provide the ideal answers to clinical questions using a structured search, critical appraisal, authoritative recommendations, clinical perspective, and rigorous peer review. Clinical Inquiries deliver best evidence for point-of-care use.

- Harrison, T. R., & Fauci, A. S. (2009). Harrison's Manual of Medicine . New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. Contains the clinical portions of Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine .

- Lippincott manual of nursing practice (8th ed.). (2006). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Provides background information on clinical nursing practice.

- Medscape: Drugs & Diseases An open-access, point-of-care medical reference that includes clinical information from top physicians and pharmacists in the United States and worldwide.

- Virginia Henderson Global Nursing e-Repository An open-access repository that contains works by nurses and is sponsored by Sigma Theta Tau International, the Honor Society of Nursing. Note: This resource contains both expert opinion and evidence-based practice articles.

- Previous Page: Phrasing Research Questions

- Next Page: Evidence Types

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Types of Assignments

Cristy Bartlett and Kate Derrington

Introduction

As discussed in the previous chapter, assignments are a common method of assessment at university. You may encounter many assignments over your years of study, yet some will look quite different from others. By recognising different types of assignments and understanding the purpose of the task, you can direct your writing skills effectively to meet task requirements. This chapter draws on the skills from the previous chapter, and extends the discussion, showing you where to aim with different types of assignments.

The chapter begins by exploring the popular essay assignment, with its two common categories, analytical and argumentative essays. It then examines assignments requiring case study responses , as often encountered in fields such as health or business. This is followed by a discussion of assignments seeking a report (such as a scientific report) and reflective writing assignments, common in nursing, education and human services. The chapter concludes with an examination of annotated bibliographies and literature reviews. The chapter also has a selection of templates and examples throughout to enhance your understanding and improve the efficacy of your assignment writing skills.

Different Types of Written Assignments

At university, an essay is a common form of assessment. In the previous chapter Writing Assignments we discussed what was meant by showing academic writing in your assignments. It is important that you consider these aspects of structure, tone and language when writing an essay.

Components of an essay

Essays should use formal but reader friendly language and have a clear and logical structure. They must include research from credible academic sources such as peer reviewed journal articles and textbooks. This research should be referenced throughout your essay to support your ideas (See the chapter Working with Information ).

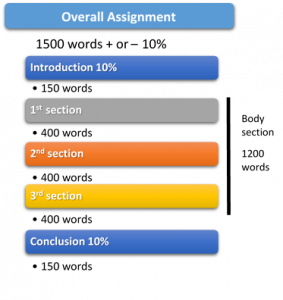

If you have never written an essay before, you may feel unsure about how to start. Breaking your essay into sections and allocating words accordingly will make this process more manageable and will make planning the overall essay structure much easier.

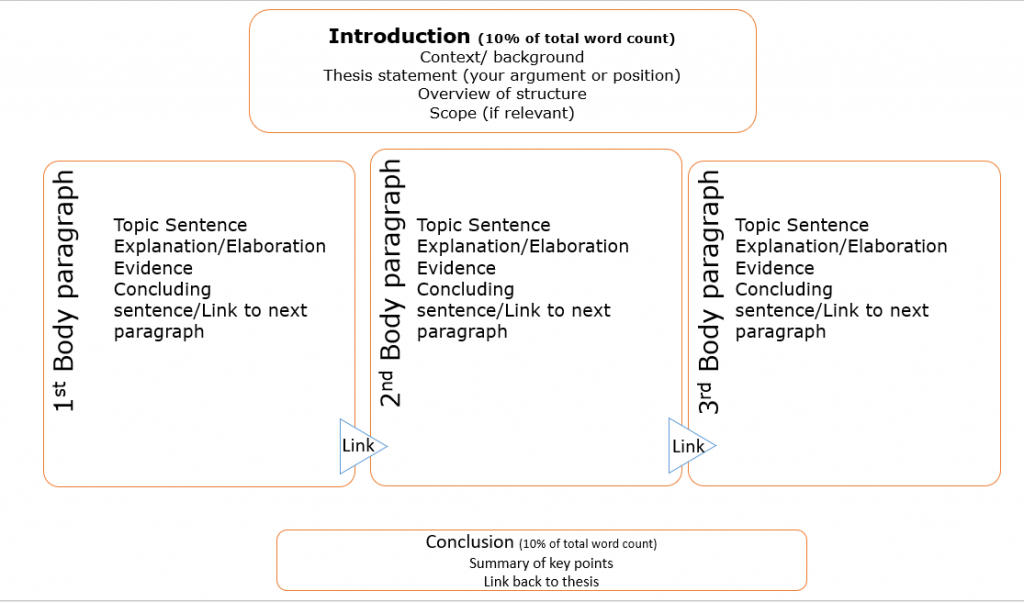

- An essay requires an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion.

- Generally, an introduction and conclusion are approximately 10% each of the total word count.

- The remaining words can then be divided into sections and a paragraph allowed for each area of content you need to cover.

- Use your task and criteria sheet to decide what content needs to be in your plan

An effective essay introduction needs to inform your reader by doing four basic things:

Table 20.1 An effective essay

An effective essay body paragraph needs to:

An effective essay conclusion needs to:

Common types of essays

You may be required to write different types of essays, depending on your study area and topic. Two of the most commonly used essays are analytical and argumentative . The task analysis process discussed in the previous chapter Writing Assignments will help you determine the type of essay required. For example, if your assignment question uses task words such as analyse, examine, discuss, determine or explore, you would be writing an analytical essay . If your assignment question has task words such as argue, evaluate, justify or assess, you would be writing an argumentative essay . Despite the type of essay, your ability to analyse and think critically is important and common across genres.

Analytical essays

These essays usually provide some background description of the relevant theory, situation, problem, case, image, etcetera that is your topic. Being analytical requires you to look carefully at various components or sections of your topic in a methodical and logical way to create understanding.

The purpose of the analytical essay is to demonstrate your ability to examine the topic thoroughly. This requires you to go deeper than description by considering different sides of the situation, comparing and contrasting a variety of theories and the positives and negatives of the topic. Although in an analytical essay your position on the topic may be clear, it is not necessarily a requirement that you explicitly identify this with a thesis statement, as is the case with an argumentative essay. If you are unsure whether you are required to take a position, and provide a thesis statement, it is best to check with your tutor.

Argumentative essays

These essays require you to take a position on the assignment topic. This is expressed through your thesis statement in your introduction. You must then present and develop your arguments throughout the body of your assignment using logically structured paragraphs. Each of these paragraphs needs a topic sentence that relates to the thesis statement. In an argumentative essay, you must reach a conclusion based on the evidence you have presented.

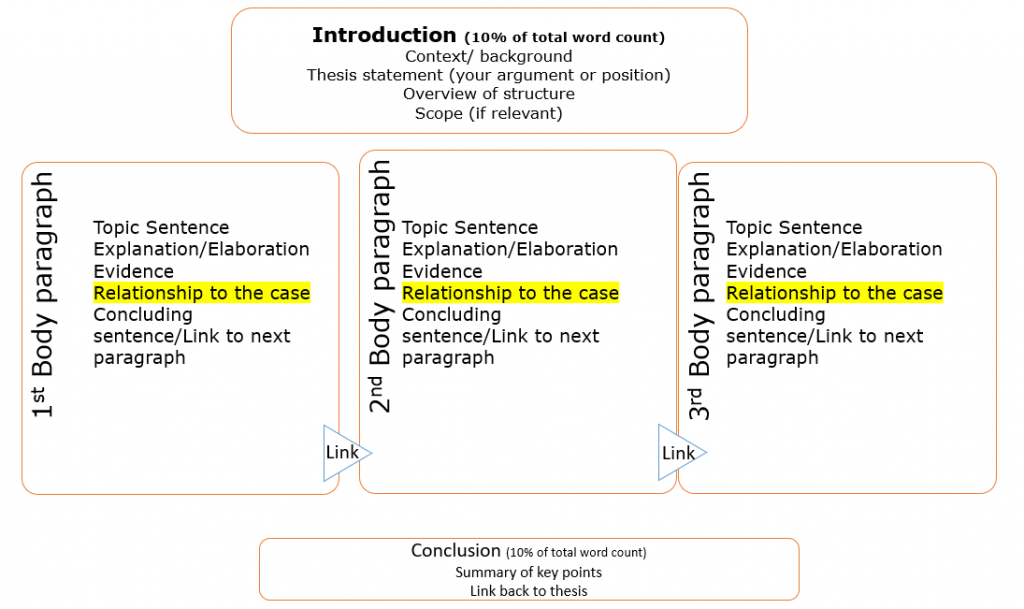

Case Study Responses

Case studies are a common form of assignment in many study areas and students can underperform in this genre for a number of key reasons.

Students typically lose marks for not:

- Relating their answer sufficiently to the case details

- Applying critical thinking

- Writing with clear structure

- Using appropriate or sufficient sources

- Using accurate referencing

When structuring your response to a case study, remember to refer to the case. Structure your paragraphs similarly to an essay paragraph structure but include examples and data from the case as additional evidence to support your points (see Figure 20.5 ). The colours in the sample paragraph below show the function of each component.

The Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) Code of Conduct and Nursing Standards (2018) play a crucial role in determining the scope of practice for nurses and midwives. A key component discussed in the code is the provision of person-centred care and the formation of therapeutic relationships between nurses and patients (NMBA, 2018). This ensures patient safety and promotes health and wellbeing (NMBA, 2018). The standards also discuss the importance of partnership and shared decision-making in the delivery of care (NMBA, 2018, 4). Boyd and Dare (2014) argue that good communication skills are vital for building therapeutic relationships and trust between patients and care givers. This will help ensure the patient is treated with dignity and respect and improve their overall hospital experience. In the case, the therapeutic relationship with the client has been compromised in several ways. Firstly, the nurse did not conform adequately to the guidelines for seeking informed consent before performing the examination as outlined in principle 2.3 (NMBA, 2018). Although she explained the procedure, she failed to give the patient appropriate choices regarding her health care.

Topic sentence | Explanations using paraphrased evidence including in-text references | Critical thinking (asks the so what? question to demonstrate your student voice). | Relating the theory back to the specifics of the case. The case becomes a source of examples as extra evidence to support the points you are making.

Reports are a common form of assessment at university and are also used widely in many professions. It is a common form of writing in business, government, scientific, and technical occupations.

Reports can take many different structures. A report is normally written to present information in a structured manner, which may include explaining laboratory experiments, technical information, or a business case. Reports may be written for different audiences including clients, your manager, technical staff, or senior leadership within an organisation. The structure of reports can vary, and it is important to consider what format is required. The choice of structure will depend upon professional requirements and the ultimate aims of the report. Consider some of the options in the table below (see Table 20.2 ).

Table 20.2 Explanations of different types of reports

Reflective writing.

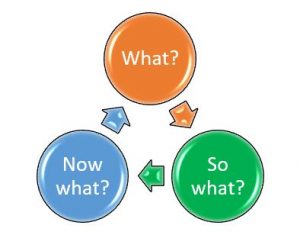

Reflective writing is a popular method of assessment at university. It is used to help you explore feelings, experiences, opinions, events or new information to gain a clearer and deeper understanding of your learning. A reflective writing task requires more than a description or summary. It requires you to analyse a situation, problem or experience, consider what you may have learnt and evaluate how this may impact your thinking and actions in the future. This requires critical thinking, analysis, and usually the application of good quality research, to demonstrate your understanding or learning from a situation. Essentially, reflective practice is the process of looking back on past experiences and engaging with them in a thoughtful way and drawing conclusions to inform future experiences. The reflection skills you develop at university will be vital in the workplace to assist you to use feedback for growth and continuous improvement. There are numerous models of reflective writing and you should refer to your subject guidelines for your expected format. If there is no specific framework, a simple model to help frame your thinking is What? So what? Now what? (Rolfe et al., 2001).

Table 20.3 What? So What? Now What? Explained.

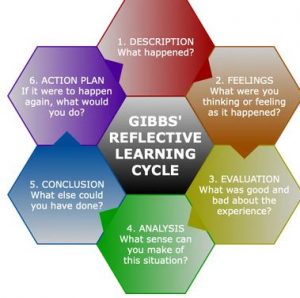

The Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle

The Gibbs’ Cycle of reflection encourages you to consider your feelings as part of the reflective process. There are six specific steps to work through. Following this model carefully and being clear of the requirements of each stage, will help you focus your thinking and reflect more deeply. This model is popular in Health.

The 4 R’s of reflective thinking

This model (Ryan and Ryan, 2013) was designed specifically for university students engaged in experiential learning. Experiential learning includes any ‘real-world’ activities including practice led activities, placements and internships. Experiential learning, and the use of reflective practice to heighten this learning, is common in Creative Arts, Health and Education.

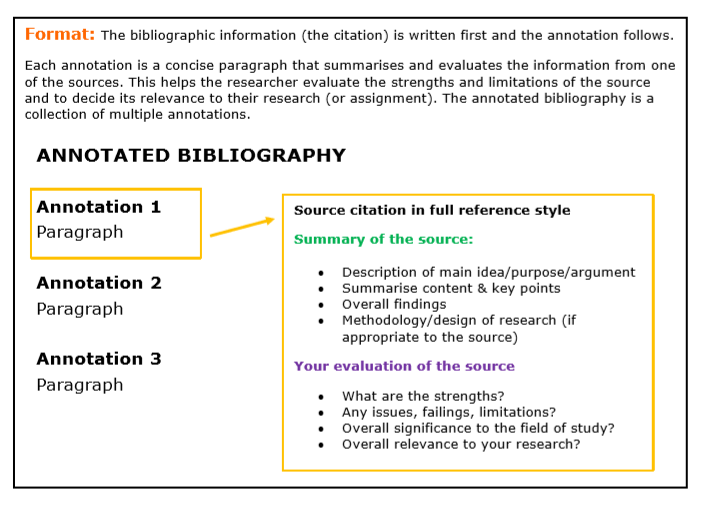

Annotated Bibliography

What is it.

An annotated bibliography is an alphabetical list of appropriate sources (books, journals or websites) on a topic, accompanied by a brief summary, evaluation and sometimes an explanation or reflection on their usefulness or relevance to your topic. Its purpose is to teach you to research carefully, evaluate sources and systematically organise your notes. An annotated bibliography may be one part of a larger assessment item or a stand-alone assessment piece. Check your task guidelines for the number of sources you are required to annotate and the word limit for each entry.

How do I know what to include?

When choosing sources for your annotated bibliography it is important to determine:

- The topic you are investigating and if there is a specific question to answer

- The type of sources on which you need to focus

- Whether they are reputable and of high quality

What do I say?

Important considerations include:

- Is the work current?

- Is the work relevant to your topic?

- Is the author credible/reliable?

- Is there any author bias?

- The strength and limitations (this may include an evaluation of research methodology).

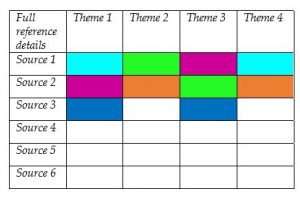

Literature Reviews

It is easy to get confused by the terminology used for literature reviews. Some tasks may be described as a systematic literature review when actually the requirement is simpler; to review the literature on the topic but do it in a systematic way. There is a distinct difference (see Table 20.4 ). As a commencing undergraduate student, it is unlikely you would be expected to complete a systematic literature review as this is a complex and more advanced research task. It is important to check with your lecturer or tutor if you are unsure of the requirements.

Table 20.4 Comparison of Literature Reviews

Generally, you are required to establish the main ideas that have been written on your chosen topic. You may also be expected to identify gaps in the research. A literature review does not summarise and evaluate each resource you find (this is what you would do in an annotated bibliography). You are expected to analyse and synthesise or organise common ideas from multiple texts into key themes which are relevant to your topic (see Figure 20.10 ). Use a table or a spreadsheet, if you know how, to organise the information you find. Record the full reference details of the sources as this will save you time later when compiling your reference list (see Table 20.5 ).

Overall, this chapter has provided an introduction to the types of assignments you can expect to complete at university, as well as outlined some tips and strategies with examples and templates for completing them. First, the chapter investigated essay assignments, including analytical and argumentative essays. It then examined case study assignments, followed by a discussion of the report format. Reflective writing , popular in nursing, education and human services, was also considered. Finally, the chapter briefly addressed annotated bibliographies and literature reviews. The chapter also has a selection of templates and examples throughout to enhance your understanding and improve the efficacy of your assignment writing skills.

- Not all assignments at university are the same. Understanding the requirements of different types of assignments will assist in meeting the criteria more effectively.

- There are many different types of assignments. Most will require an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion.

- An essay should have a clear and logical structure and use formal but reader friendly language.

- Breaking your assignment into manageable chunks makes it easier to approach.

- Effective body paragraphs contain a topic sentence.

- A case study structure is similar to an essay, but you must remember to provide examples from the case or scenario to demonstrate your points.

- The type of report you may be required to write will depend on its purpose and audience. A report requires structured writing and uses headings.

- Reflective writing is popular in many disciplines and is used to explore feelings, experiences, opinions or events to discover what learning or understanding has occurred. Reflective writing requires more than description. You need to be analytical, consider what has been learnt and evaluate the impact of this on future actions.

- Annotated bibliographies teach you to research and evaluate sources and systematically organise your notes. They may be part of a larger assignment.

- Literature reviews require you to look across the literature and analyse and synthesise the information you find into themes.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ryan, M. & Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development , 32(2), 244-257. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.661704

Academic Success Copyright © 2021 by Cristy Bartlett and Kate Derrington is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Current students

- Staff intranet

- Find an event

- Academic writing

- Types of academic writing

- Planning your writing

- Structuring written work

- Grammar, spelling and vocabulary

- Editing and proofreading

Evidence, plagiarism and referencing

- Resources and support

Using evidence

Many types of university assignments are persuasive or critical . In these types of texts, you need to provide evidence to support your claims.

Different disciplines use different types of evidence. For example, in arts disciplines, published sources are the main evidence, while science disciplines often use various types of empirical data (such as statistics or other experimental results) as the main evidence.

In addition to finding the right kind of evidence you need to evaluate the quality of evidence - not all pieces of evidence will be equally valuable for you to use. You should consider:

- whether the evidence directly demonstrates support for a claim you are making. For example, does it show that another scholar agrees with your argument, or that results confirm your interpretation?

- the reliability of the evidence. Is it published in a peer-reviewed journal or a book by a reputable publisher? Is the author someone who has expertise and status in the field? Has the data been obtained through a rigorous methodology, using an appropriate sample?

- if it meets the standards for good evidence in your discipline. For example, in some disciplines, such as information technology, sources need to be quite recent, as publications that are two years old may already be out of date. In other disciplines, like philosophy, sources that are more than 200 years old may still be authoritative and relevant.

If you’re not sure what type of evidence you should use, or what is good-quality evidence in your discipline, you could start by:

- checking the assignment instructions and any rubrics/marking guide/grade descriptors provided

- asking your lecturer/tutor for more information

- discussing it with other students

- looking at the type of evidence used in the readings for that unit of study.

Plagiarism is using someone else’s work as if it were your own. It is a type of academic dishonesty.

Make sure you’re familiar with what is considered plagiarism and what the consequences are .

Avoiding plagiarism

To avoid plagiarism, you need to be aware of what it is , and have good writing skills and referencing knowledge. You need to be able to:

- paraphrase and summarise

- know when to quote a source and when to paraphrase it

- link information from sources with your own ideas

- correctly use referencing conventions .

When you quote a source, you use an extract exactly as it was used in/by the source. You indicate a quote by using quotation marks or indenting the text for long quotes.

When you paraphrase or summarise, you put the author’s ideas in your own words. However, you still need to attribute the idea to the author by including a reference.

It’s usually better to paraphrase than quote, as it shows a higher level of thinking, understanding and writing skills. To rephrase ideas, you need a large vocabulary of formal and technical words for the subject matter, as well as grammatical flexibility.

To develop your skills in quoting, summarising and paraphrasing, visit the Write Site or attend a Learning Hub (Academic Language and Learning) workshop .

If you have a language background other than English, you can also work on these skills by spending as many hours per day as possible in English conversation. You can also study the vocabulary and grammar patterns used in the books and articles you’re reading for your course.

Referencing

In order to avoid plagiarism, you need to acknowledge your sources through referencing.

There are several different referencing conventions, also called citation styles, such as Harvard, American Psychological Association and MLA. The referencing convention you use depends on your discipline.

You should be told which system to use by your lecturer, school, department and/or faculty at the beginning of the year or semester. You will be told either in a set of general guidelines, the outline for the unit of study or in the instructions for a particular assignment. Occasionally, you will be allowed to choose the citation style you prefer, as long as it is consistently used. If you’re not sure which system to use, ask your lecturer.

Find out how to reference on the Library website .

If you have a lot of references, you can use software such as EndNote to automatically apply the right format to each reference. EndNote can be downloaded for free from the Library’s website . The Library also runs classes on using EndNote.

This material was developed by the the Learning Hub (Academic Language and Learning), which offers workshops, face-to-face consultations and resources to support your learning. Find out more about how they can help you develop your communication, research and study skills .

See our Writing skills handouts .

Related links

- Learning Hub (Academic Language and Learning)

- Learning Hub (Academic Language and Learning) workshops

- Prepare your thesis

- Academic dishonesty and plagiarism

- Website feedback

Your feedback has been sent.

Sorry there was a problem sending your feedback. Please try again

You should only use this form to send feedback about the content on this webpage – we will not respond to other enquiries made through this form. If you have an enquiry or need help with something else such as your enrolment, course etc you can contact the Student Centre.

- Find an expert

- Media contacts

Student links

- How to log in to University systems

- Class timetables

- Our rankings

- Faculties and schools

- Research centres

- Campus locations

- Find a staff member

- Careers at Sydney

- Emergencies and personal safety

- Accessibility

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Evidence Analysis and Processing

Evidence refers to information or objects that may be admitted into court for judges and juries to consider when hearing a case. Evidence can come from varied sources — from genetic material or trace chemicals to dental history or fingerprints. Evidence can serve many roles in an investigation, such as to trace an illicit substance, identify remains or reconstruct a crime.

NIJ funds research and development to improve how law enforcement gathers and uses evidence. It supports the enhancement and creation of tools and techniques to identify, collect, analyze, interpret and preserve evidence.

On this page, find links to articles, awards, events, publications, and multimedia related to evidence analysis and processing.

- Drug-Impaired Driving: The Contribution of Emerging and Undertested Drugs

- Determining the Age-At-Death of Infants, Children, and Teens

- Highlighting Significant NIJ Forensic Science Investments: The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Site Visit

Events and Trainings

- Foundational Statistics for Forensic Toxicology Webinar Series

- FBI Laboratory Decision Analysis Studies in Pattern Evidence Examinations

- Direct Analysis in Real Time Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS) for Seized Drug Analysis

Publications

- Evidence-Based Evaluation Of The Analytical Schemes In ASTM E2329-17 Standard Practice For Identification Of Seized Drugs For Methamphetamine Samples

- Justice Today Podcast: Closing Cases Using Gunshot Residue

- View related awards

- Find sites with statistics related to: Evidence analysis and processing

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Types of Assignments

Gen Ed courses transcend disciplinary boundaries in a variety of ways, so the types of writing assignments that they include also often venture outside the traditional discipline-specific essays. You may encounter a wide variety of assignment types in Gen Ed, but most can be categorized into four general types:

- Traditional academic assignments include the short essays or research papers most commonly associated with college-level assignments. Generally speaking, these kinds of assignments are "expository" in nature, i.e., they ask you to engage with ideas through evidence-base argument, written in formal prose. The majority of essays in Expos courses fall into this category of writing assignment types.

- Less traditional academic assignments include elements of engagement in academia not normally encountered by undergraduates.

- Traditional non-academic assignments include types of written communication that students are likely to encounter in real world situations.

- Less traditional non-academic assignments are those that push the boundaries of typical ‘writing’ assignments and are likely to include some kind of creative or artistic component.

Examples and Resources

Traditional academic.

For most of us, these are the most familiar types of college-level writing assignments. While they are perhaps less common in Gen Ed than in departmental courses, there are still numerous examples we could examine.

Two illustrations of common types include:

Example 1: Short Essay Professor Michael Sandel asks the students in his Gen Ed course on Tech Ethics to write several short essays over the course of the semester in which they make an argument in response to the course readings. Because many students will never have written a philosophy-style paper, Professor Sandel offers students a number of resources—from a guide on writing in philosophy, to sample graded essays, to a list of logical fallacies—to keep in mind.

Example 2: Research Paper In Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Cares?, a Gen Ed course co-taught by multiple global health faculty members, students write a 12–15 page research paper on a biosocial analysis of a global health topic of their choosing for the final assignment. The assignment is broken up into two parts: (1) a proposal with annotated bibliography and (2) the final paper itself. The prompt clearly outlines the key qualities and features of a successful paper, which is especially useful for students who have not yet written a research paper in the sciences.

Less Traditional Academic

In Gen Ed, sometimes assignments ask students to engage in academic work that, while familiar to faculty, is beyond the scope of the typical undergraduate experience.

Here are a couple of examples from Gen Ed courses:

Example 1: Design a conference For the final project in her Gen Ed course, Global Feminisms, Professor Durba Mitra asks her students to imagine a dream conference in the style of the feminist conferences they studied in class. Students are asked to imagine conference panels and events, potential speakers or exhibitions, and advertising materials. While conferences are a normal occurrence for graduate students and professors, undergraduates are much less likely to be familiar with this part of academic life, and this kind of assignment might require more specific background and instructions as part of the prompt.

Example 2: Curate a museum exhibit In his Gen Ed class, Pyramid Schemes, Professor Peter Der Manuelian's final project offers students the option of designing a virtual museum exhibit . While exhibit curation can be a part of the academic life of an anthropologist or archaeologist, it's not often found in introductory undergraduate courses. In addition to selecting objects and creating a virtual exhibit layout, students also wrote an annotated bibliography as well as an exhibit introduction for potential visitors.

Traditional Non-academic

One of the goals of Gen Ed is to encourage students to engage with the world around them. Sometimes writing assignments in Gen Ed directly mirror types of writing that students are likely to encounter in real-world, non-academic settings after they graduate.

The following are several examples of such assignments:

Example 1: Policy memo In Power and Identity in the Middle East, Professor Melani Cammett assigns students a group policy memo evaluating "a major initiative aimed at promoting democracy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)." The assignment prompt is actually structured as a memo, providing context for students who likely lack experience with the format. It also outlines the key characteristics of a good memo, and it provides extensive advice on the process—especially important when students are working in groups.

Example 2: Letter In Loss, Professor Kathleen Coleman asks students to write a letter of condolence . The letter has an unusual audience: a mother elephant who lost her calf. Since students may not have encountered this type of writing before, Professor Coleman also provides students with advice on process, pointing to some course readings that might be a good place to start. She also suggests a list of outside resources to help students get into the mindframe of addressing an elephant.

Example 3: Podcast Podcasts are becoming increasingly popular in Gen Ed classes, as they are in the real world. Though they're ultimately audio file outputs, they usually require writing and preparing a script ahead of time. For example, in Music from Earth, Professor Alex Rehding asks students to create a podcast in which they make an argument about a song studied in class. He usefully breaks up the assignments into two parts: (1) researching the song and preparing a script and (2) recording and making sonic choices about the presentation, offering students the opportunity to get feedback on the first part before moving onto the second.

Less Traditional Non-academic

These are the types of assignments that perhaps are less obviously "writing" assignments. They usually involve an artistic or otherwise creative component, but they also often include some kind of written introduction or artist statement related to the work.

The following are several examples from recently offered Gen Ed courses:

Example 1: Movie Professor Peter Der Manuelian offers students in his class, Pyramid Schemes, several options for the final project, one of which entails creating a 5–8 minute iMovie making an argument about one of the themes of the course. Because relatively few students have prior experience making films, the teaching staff provide students with a written guide to making an iMovie as well as ample opportunities for tech support. In addition to preparing a script as part of the production, students also submit both an annotated bibliography and an artist’s statement.

Example 2: Calligram In his course, Understanding Islam and Contemporary Muslim Societies, Professor Ali Asani asks students to browse through a provided list of resources about calligrams, which are an important traditional Islamic art form. Then they are required to "choose a concept or symbol associated with God in the Islamic tradition and attempt to represent it through a calligraphic design using the word Allah," in any medium they wish. Students also write a short explanation to accompany the design itself.

Example 3: Soundscape In Music from Earth, Professor Alex Rehding has students create a soundscape . The soundscape is an audio file which involves layering sounds from different sources to create a single piece responding to an assigned question (e.g. "What sounds are characteristic of your current geographical region?"). Early on, as part of the development of the soundscape, students submit an artist's statement that explains the plan for the soundscape, the significance of the sounds, and the intention of the work.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Receiving Feedback

Assignment Decoder

Writing Guide: Types of Assignments & Best Practices

- Home & Appointments

- Types of Assignments & Best Practices

- Tables & Figures

- Thesis & Project Guide

The most common types of writing assignments you will encounter at MLTS

- How to approach a writing assignment

- Expository writing & research papers

- Compare & Contrast paper

- Book & Literature Reviews

- Reflective writing

- Online discussion posts

- Thesis/Project

As a graduate student, you will be assigned a variety of types of writing projects. A good rule of thumb in approaching any writing project is to ask yourself: for whom am I writing and why? Or, who is my audience and what do they expect from my writing? Your assignments will almost invariably require you to make one or more arguments. A good argument is well-written, logical, and supported by evidence.

Expository writing involves understanding, explaining, analyzing, and/or evaluating a topic. It includes your standard graduate school essay, book review, or research paper where your instructor requires you to analyze and/or study a topic. In general, your audience for such assignments will be your course instructor. You can think of such writing assignments as your instructor asking you to make an argument. Your instructor wants to gauge your creative thinking skills and how well you understand the course material by seeing how well you can make an argument related to that material. Remember: a good argument is well-written, logical, and supported by evidence.

An expository paper is therefore not about you (at least not directly); it is about the facts you have learned and researched and the argument you have built from those facts. Therefore, unless you are quoting someone, you should avoid using first person pronouns (the words I, me, my, we, us, our ) in your writing. Let your facts and arguments speak for themselves instead of beginning statements with "I think" or "I believe."

A compare & contrast assignment is a type of expository & research paper assignment. It is important to organize your writing around the themes you are comparing & contrasting. If, for example, you are assigned to compare & contrast, say, Augustine's Confessions and The Autobiography of Malcolm X , a common mistake students make is to write the first part of their essay strictly about Augustine's Confessions , and the second part of the essay strictly about The Autobiography of Malcolm X . In a good compare & contrast essay, you instead explore an issue in every paragraph or two, and show how, in this case, both Augustine & Malcolm X share common ground or differ on that issue. Then, move onto another issue and show how both Augustne and Malcolm X covered it.

Unless your instructor directs you otherwise, you should not use first person pronouns ( I, me, my ) in such a paper.

A book review assignment is meant to be an analysis of a book, not a chapter-by-chapter summary of a book. Instead of organizing your paper sequentially (the first paragraph is about chapter 1, the second paragraph is about chapter 2, etc.), organize your paragraphs around the themes of the book that are thread throughout the book. Topics to consider in a book review include (but are not limited to):

- What are the author's arguments, and how successful is she in making those arguments?

- What sort of sources does the author utilize?

- What methodology/methodologies does the author utilize?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the book?

A literature review is similar to a book review assignment in that it is meant to be an analysis of a theme or themes across several books/articles. What have various authors written about your topic? That said, as you will typically have less space to talk about each work (perhaps a paragraph or less for each work as opposed to multiple pages), you might end up moving from one author's findings to another. For a literature review in a thesis, think of a literature review as a mini-essay within your broader thesis with its own mini-introduction, thesis statement, and conclusion.

Unless your instructor directs you otherwise, book reviews and literature reviews should be written like expository & research papers. In particular, you should not use first person pronouns ( I, me, my ). So, instead of writing: "I think this book is a good analysis of ___," write: "This book is a good analysis of ___."

Reflective essays are especially common in theology courses. Reflective writing requires that you explicitly write about yourself and your own views. To put it another way, you typically have two audiences to write for in such an assignment: your instructor and yourself. As such, and unlike a standard expository paper, such essays require you to write about yourself using first person pronouns ( I, me, my) and use statements like “I think” and “I believe.” Otherwise, a reflective essay shares a lot with expository writing. You are still making arguments, and you still need evidence from cited sources! Unless your instructor tells you otherwise, you should still include a good title, introduction paragraph, thesis statement, conclusion, and bibliography.

For online courses, you will likely have to take part in classroom or group discussions online, in which you will be encouraged or even required to respond to your classmates. Such writing assignments often include a reflective element. Discussion posts are almost always shorter than essays and as such may not need long introductions or conclusions. That said, a discussion post is not like a Facebook or social media post! Good discussion posts are long and well-written enough to convey one or more thoughtful, insightful observations; you cannot just "like" someone else's post or only write "Good job!" If you decide to challenge or critique a classmate’s post—and you are certainly encouraged to do so!—you should do so in a respectful and constructive manner. As your main audience for online discussions are your own classmates and, to a lesser extent, your instructor, it is often okay to use relatively more informal language and to refer to yourself using first person pronouns ( I, me, my ). Finally, as with reflective essays, discussion posts still benefit from evidence. Even if a discussion post is relatively less formal than an essay, if you quote, paraphrase, or draw ideas from outside sources, you still must cite them! If the online medium does not allow for footnotes, use parenthetical references for citations (see chapter 19 of Turabian).

Those of you taking preaching courses or earning a DMin degree will have to write and submit your sermons. On one hand, your main audience for such a writing assignment is the congregation to whom you may preach. The language, tone, message, level of detail, etc. of a good sermon will depend on the precise context of your congregation and the message you want to impart. Therefore, unlike an expository essay or a reflective essay, you have a lot more freedom in how you chose to organize your sermon, as well as how formal or not you want the language to be.