Social Media Marketing: A Literature Review on Consumer Products

Proceedings of the International Conference on Business & Information (ICBI) 2020

15 Pages Posted: 10 Jun 2021

A Siriwardana

University of Kelaniya

Date Written: November 19, 2020

Social media is used by billions of people around the world and has fast become one of the defining technologies of our time. Social media allows people to freely interact with others and offers multiple ways for marketers to reach and engage with consumers. Due to its dynamic and emergent nature, the effectiveness of social media as a marketing communication channel has presented many challenges for marketers. It is considered to be different to traditional marketing channels. Many organizations are investing in their social media presence because they appreciate the need to engage in existing social media conversations in order to build their consumer brand. Social Medias are increasingly replacing traditional media, and more consumers are using them as a source of information about products, services and brands. The purpose of this paper is to focus on where to believe the future of social media lie when considering consumer products. The Paper followed a deductive approach and this paper attempts to review current scholarly on social media marketing literature and research, including its beginnings, current usage, benefits and downsides, and best practices. Further examinations to uncover the vital job of social media, inside a digitalized business period in promoting and branding consumer products. As a result of the comprehensive analysis, it undoubtedly displays that social media is a significant power in the present marketing scene.

Keywords: Consumer Products, Customer Engagement, Digitalization, Social Media

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

A Siriwardana (Contact Author)

University of kelaniya ( email ).

Kelaniya Sri Lanka Kelaniya, Western 11600 Sri Lanka

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, advertising, marketing & strategic communication ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Information Systems: Behavioral & Social Methods eJournal

Social media marketing strategy: definition, conceptualization, taxonomy, validation, and future agenda

- Conceptual/Theoretical Paper

- Open access

- Published: 10 June 2020

- Volume 49 , pages 51–70, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Fangfang Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4883-1730 1 ,

- Jorma Larimo 1 &

- Leonidas C. Leonidou 2

335k Accesses

30 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Although social media use is gaining increasing importance as a component of firms’ portfolio of strategies, scant research has systematically consolidated and extended knowledge on social media marketing strategies (SMMSs). To fill this research gap, we first define SMMS, using social media and marketing strategy dimensions. This is followed by a conceptualization of the developmental process of SMMSs, which comprises four major components, namely drivers, inputs, throughputs, and outputs. Next, we propose a taxonomy that classifies SMMSs into four types according to their strategic maturity level: social commerce strategy, social content strategy, social monitoring strategy, and social CRM strategy. We subsequently validate this taxonomy of SMMSs using information derived from prior empirical studies, as well with data collected from in-depth interviews and a quantitive survey among social media marketing managers. Finally, we suggest fruitful directions for future research based on input received from scholars specializing in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

The future of social media in marketing

Social media influencer marketing: foundations, trends, and ways forward

Online influencer marketing

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The past decade has witnessed the development of complex, multifarious, and intensified interactions between firms and their customers through social media usage. On the one hand, firms are taking advantage of social media platforms to expand geographic reach to buyers (Gao et al. 2018 ), bolster brand evaluations (Naylor et al. 2012 ), and build closer connections with customers (Rapp et al. 2013 ). On the other hand, customers are increasingly empowered by social media and taking control of the marketing communication process, and they are becoming creators, collaborators, and commentators of messages (Hamilton et al. 2016 ). As the role of social media has gradually evolved from a single marketing tool to that of a marketing intelligence source (in which firms can observe, analyze, and predict customer behaviors), it has become increasingly imperative for marketers to strategically use and leverage social media to achieve competitive advantage and superior performance (Lamberton and Stephen 2016 ).

Despite widespread understanding among marketers of the need to engage customers on social media platforms, relatively few firms have properly strategized their social media appearance and involvement (Choi and Thoeni 2016 ; Griffiths and Mclean 2015 ). Rather, for most companies, the ongoing challenge is not to initiate social media campaigns, but to combine social media with their marketing strategy to engage customers in order to build valuable and long-term relationships with them (Lamberton and Stephen 2016 ; Schultz and Peltier 2013 ). However, despite the vast opportunities social media offer to companies, there is no clear definition or comprehensive framework to guide the integration of social media with marketing strategies, to gain a rigorous understanding of the nature and role of social media marketing strategies (SMMSs) (Effing and Spil 2016 ).

Although some reviews focusing on the social media phenomenon are available (e.g., Lamberton and Stephen 2016 ; Salo 2017 ), to date, an integrative evaluation effort focusing on the strategic marketing perspective of social media is missing. This is partly because the social media literature largely derives elements from widely disparate fields, such as marketing, management, consumer psychology, and computer science (Aral et al. 2013 ). Moreover, research on SMMSs mainly covers very specific, isolated, and scattered aspects, which creates confusion and limits understanding of the subject (Lamberton and Stephen 2016 ). Furthermore, research deals only tangentially with a conceptualization, operationalization, and categorization of SMMSs, which limits theory advancement and practice development (Tafesse and Wien 2018 ).

To address these problems, and also to respond to repeated pleas from scholars in the field (e.g., Aral et al. 2013 ; Guesalaga 2016 ; Moorman and Day 2016 ; Schultz and Peltier 2013 to identify appropriate strategies to leverage social media in today’s changing marketing landscape, we aim to systematically consolidate and extend the knowledge accumulated from previous research on SMMSs. Specifically, our objectives are fivefold: (1) to clearly define SMMS by blending issues derived from the social media and marketing strategy literature streams; (2) to conceptualize the process of developing SMMSs and provide a theoretical understanding of its constituent parts; (3) to provide a taxonomy of SMMSs according to their level of strategic maturity; (4) to validate the practical value of this taxonomy using information derived from previous empirical studies, as well as from primary data collection among social media marketing managers; and (5) to develop an agenda for promising areas of future research on the subject.

Our study makes three major contributions to the social media marketing literature. First, it offers a definition and a conceptualization of SMMS that help alleviate definitional deficiency and increase conceptual clarity on the subject. By focusing on the role of social connectedness and interactions in resource integration, we stress the importance of transforming social media interactions and networks into marketing resources to help achieve specific strategic goals for the firm. In this regard, we provide theoretical justification of social media from a strategic marketing perspective. Second, using customer engagement as an overarching theory, we develop a model conceptualizing the SMMS developmental process. Through an analysis of each component of this process, we emphasize the role of insights from both firms and customers to better understand the dynamics of SMMS formulation. We also suggest certain theories to specifically explain the particular role played by each of these components in developing sound SMMSs. Third, we propose a taxonomy of SMMSs based on their level of strategic maturity that can serve as the basis for developing specific marketing strategy concepts and measurement scales within a social media context. We also expect this taxonomy to provide social media marketing practitioners with fruitful insights on why to select and how to use a particular SMMS in order to achieve superior marketing results.

Defining SMMS

Although researchers have often used the term “social media marketing strategy” in their studies (e.g., Choi and Thoeni 2016 ; Kumar et al. 2013 ; Zhang et al. 2017 ), they have yet to propose a clear definition. Despite the introduction of several close terms in the past, including “social media strategy” (Aral et al. 2013 ; Effing and Spil 2016 ), “online marketing strategy” (Micu et al. 2017 ), and “strategic social media marketing” (Felix et al. 2017 ), these either fail to take into consideration the different functions/features of social media or neglect key marketing strategy issues. What is therefore required is an all-encompassing definition of SMMS that will capture two fundamental elements—namely, social media and marketing strategy. Table 1 draws a comparison between social media and marketing strategy on five dimensions (i.e., core, orientation, resource, purpose, and premise) and presents the resulting profile of SMMS.

- Social media

In a marketing context, social media are considered platforms on which people build networks and share information and/or sentiments (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010 ). With their distinctive nature of being “dynamic, interconnected, egalitarian, and interactive organisms” (Peters et al. 2013 , p. 281), social media have generated three fundamental shifts in the marketplace. First, social media enable firms and customers to connect in ways that were not possible in the past. Such connectedness is empowered by various platforms, such as social networking sites (e.g., Facebook), microblogging sites (e.g., Twitter), and content communities (e.g., YouTube), that allow social networks to build from shared interests and values (Kaplan and Haenlein 2010 ). In this regard, “social connectedness” has also been termed as “social ties” (e.g., Muller and Peres 2019 ; Quinton and Wilson 2016 ), and the strength and span of these ties determine whether they are strong or weak (Granovetter 1973 ). Prior studies have shown that tie strength is an important determinant of customer referral behaviors (e.g., Verlegh et al. 2013 ).

Second, social media have transformed the way firms and customers interact and influence each other. Social interaction involves “actions,” whether through communications or passive observations, that influence others’ choices and consumption behaviors (Chen et al. 2011 ). Nair et al. ( 2010 ) labeled such social interactions as “word-of-mouth (WOM) effect” or “contagion effects.” Muller and Peres ( 2019 ) argue that social interactions rely strongly on the social network structure and provide firms with measurable value (also referred to as “social equity”). In social media studies, researchers have long recognized the importance of social influence in affecting consumer decisions, and recent studies have shown that people’s connection patterns and the strength of social ties can signify the intensity of social interactions (e.g., Aral and Walker 2014 ; Katona et al. 2011 ).

Third, the proliferation of social media data has made it increasingly possible for companies to better manage customer relationships and enhance decision making in business (Libai et al. 2010 ). Social media data, together with other digital data, are widely characterized by the 3Vs (i.e., volume, variety, and velocity), which refer to the vast quantity of data, various sources of data, and expansive real-time data (Alharthi et al. 2017 ). A huge amount of social media data derived from different venues (e.g., social networks, blogs, forums) and in various formats (e.g., text, video, image) can now be easily extracted and usefully exploited with the aid of modern information technologies (Moe and Schweidel 2017 ). Thus, social media data can serve as an important source of customer analysis, market research, and crowdsourcing of new ideas, while capturing and creating value through social media data represents the development of a new strategic resource that can improve marketing outcomes (Gnizy 2019 ).

- Marketing strategy

According to Varadarajan ( 2010 ), a marketing strategy consists of an integrated set of decisions that helps the firm make critical choices regarding marketing activities in selected markets and segments, with the aim to create, communicate, and deliver value to customers in exchange for accomplishing its specific financial, market, and other objectives. According to the resource-based view of the firm (Barney 1991 ), organizational resources (e.g., financial, human, physical, informational, relational) help firms enhance their marketing strategies, achieve sustainable competitive advantage, and gain better performance. These resources can be either tangible or intangible and can be transformed into higher-order resources (i.e., competencies and capabilities), enabling the delivery of superior value to targeted buyers (Hunt and Morgan 1995 ; Teece and Pisano 1994 ).

Different marketing strategies can be arranged on a continuum, on which transaction marketing strategy and relationship marketing strategy represent its two ends, while in between are various mixed marketing strategies (Grönroos 1991 ). Webster ( 1992 ) notes that long-standing customer relationships should be at the core of marketing strategy, because customer interaction and engagement can be developed into valuable relational resources (Hunt et al. 2006 ). Morgan and Hunt ( 1999 ) also claim that firms capitalizing on long-term and trustworthy customer relationships can help design value-enhancing marketing strategies that will subsequently generate competitive advantages and lead to superior performance.

From a strategic marketing perspective, social media interaction entails a process that allows not only firms, but also customers to exchange resources. For example, Hollebeek et al. ( 2019 ) assert that customers can devote operant (e.g., knowledge) and operand (e.g., equipment) resources while interacting with firms. Importantly, Gummesson and Mele ( 2010 ) argue that interactions occur not simply in dyads, but also between multiple actors within a network, underscoring the critical role of network interaction in resource integration. Notably, customer-to-customer interactions are also essential, especially for the higher level of engagement behaviors (Fehrer et al. 2018 ).

Thus, social media interconnectedness and interactions (i.e., between firm–customer and between customer–customer) can be considered strategic resources, which can be further converted into marketing capabilities (Morgan and Hunt 1999 ). A case in point is social customer relationship management (CRM) capabilities, in which the firm cultivates the competency to use information generated from social media interactions to identify and develop loyal customers (Trainor et al. 2014 ). With the expanding role of social media from a single communication tool to one of gaining customer and market knowledge, marketers can strategically develop distinct resources from social media based on extant organizational resources and capabilities.

Drawing on the previous argumentation, we define SMMS as an organization’s integrated pattern of activities that, based on a careful assessment of customers’ motivations for brand-related social media use and the undertaking of deliberate engagement initiatives, transform social media connectedness (networks) and interactions (influences) into valuable strategic means to achieve desirable marketing outcomes. This definition is parsimonious because it captures the uniqueness of the social media phenomenon, takes into consideration the fundamental premises of marketing strategy, and clearly defines the scope of activities pertaining to SMMS.

Although the underlying roots of traditional marketing strategy and SMMS are similar, the two strategies have three distinctive differences: (1) as opposed to the traditional approach, which pays peripheral attention to the heterogeneity of motivations driving customer engagement, SMMS emphasizes that social media users must be motivated on intellectual, social, cultural, or other grounds to engage with firms (and perhaps more importantly with other customers) (Peters et al. 2013 ; Venkatesan 2017 ); (2) the consequences of SMMS are jointly decided by the firm and its customers (rather than by individual actors’ behaviors), and it is only when the firm and its customers interact and build relationships that social media technological platforms become real resource integrators (Singaraju et al. 2016 ; Stewart and Pavlou 2002 ); and (3) while customer value in traditional marketing strategies is narrowly defined to solely capture purchase behavior through customer lifetime value, in the case of SMMS, this value is expressed through customer engagement, comprising both direct (e.g., customer purchases) and indirect (e.g., product referrals to other customers) contributions to the value of the firm (Kumar and Pansari 2016 ; Venkatesan 2017 ).

Conceptualizing the process of developing SMMSs

The conceptualization of the process of developing SMMSs is anchored on customer engagement theory, which posits that firms need to take deliberate initiatives to motivate and empower customers to maximize their engagement value and yield superior marketing results (Harmeling et al. 2017 ). Kumar et al. ( 2010 ) distinguish between four different dimensions of customer engagement value, namely customer lifetime value, customer referral value, customer influence value, and customer knowledge value. This metric has provided a new approach for customer valuation, which can help marketers to make more effective and efficient strategic decisions that enable long-term value contributions to customers. In a social media context, this customer engagement value enables firms to capitalize on crucial customer resources (i.e., network assets, persuasion capital, knowledge stores, and creativity), of which the leverage can provide firms with a sustainable competitive advantage (Harmeling et al. 2017 ).

Customer engagement theory highlights the importance of understanding customer motivations as a prerequisite for the firm to develop effective SMMSs, because heterogeneous customer motivations resulting from different attitudes and attachments can influence their social media behaviors and inevitably SMMS outcomes (Venkatesan 2017 ). It also stresses the role of inputs from both firm (i.e., social media engagement initiatives) and customers (i.e., social media behaviors), as well as the importance of different degrees of interactivity and interconnectedness in yielding sound marketing outcomes (Harmeling et al. 2017 ). Pansari and Kumar et al. ( 2017 ) argue that firms can benefit from such customer engagement in both tangible (e.g., higher revenues, market share, profits) and intangible (e.g., feedbacks or new ideas that help to product/service development) ways.

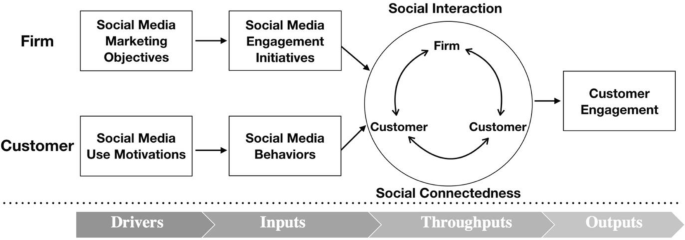

Based on consumer engagement theory, we therefore conceive the process of developing an SMMS as consisting of four interlocking parts: (1) drivers , that is, the firm’s social media marketing objectives and the customers’ social media use motivations; (2) inputs , that is, the firm’s social media engagement initiatives and the customers’ social media behaviors; (3) throughputs , that is, the way the firm connects and interacts with customers to exchange resources and satisfy needs; and (4) outputs , that is, the resulting customer engagement outcome. Figure 1 shows this developmental process of SMMS, while Table 2 indicates the specific theoretical underpinnings of each part comprising this process.

A conceptualization of the process of developing social media marketing strategies

Firms’ social media marketing objectives

Though operating in a similar context, SMMSs may differ depending on the firm’s strategic objectives (Varadarajan 2010 ). According to resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978 ), the firm’s social media marketing objectives can be justified by the need to acquire external resources (which do not exist internally) that will help it accommodate the challenges of environmental contingencies. In a social media context, customers can serve as providers of resources, which can take several forms (Harmeling et al. 2017 ). Felix et al. ( 2017 ) distinguish between proactive and reactive social media marketing objectives, which can differ by the type of market targeted (e.g., B2B vs. B2C) and firm size. While for proactive objectives, firms use social media to increase brand awareness, generate online traffic, and stimulate sales, in the case of reactive objectives, the emphasis is on monitoring and analyzing customer activities.

Customers’ social media use motivations

Social media use motivations refer to various incentives that drive people’s selection and use of specific social media (Muntinga et al. 2011 ). The existence of these motivations is theoretically grounded on uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al. 1973 ), which maintains that consumers are actively and selectively involved in media usage to gratify their psychological and social needs. In a social media context, motivations can range from utilitarian and hedonic purposes (e.g., incentives, entertainment) to relational reasons (e.g., identification, brand connection) (Rohm et al. 2013 ). Muntinga et al. ( 2011 ) also categorize consumer–brand social media interactions as motivated primarily by entertainment, information, remuneration, personal identity, social interaction, and empowerment.

Firms’ social media engagement initiatives

Firms take initiatives to motivate and engage customers so that they can make voluntary contributions in return (Harmeling et al. 2017 ; Pansari and Kumar 2017 ). These firm actions can also be theoretically explained by resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978 ), which argues that firms need to take initiatives to encourage customers to interact with them, to generate useful autonomous contributions that will alleviate resource shortages. Harmeling et al. ( 2017 ) identify two primary forms of a firm’s marketing initiatives to engage customers using social media: task-based and experiential. While task-based engagement initiatives encourage customer engagement behaviors with structured tasks (e.g., writing a review) and usually take place in the early stages of the firm’s social media marketing efforts, experiential engagement initiatives employ experiential events (e.g., multisensory events) to intrinsically motivate customer engagement and foster emotional attachment. Thus, firm engagement initiatives can be viewed as a continuum, where at one end, the firm uses monetary rewards to engage customers and, at the other end, the firm proactively works to deliver effective experiential incentives to motivate customer engagement.

Customers’ social media behaviors

The use of social media by customers yields different behavioral manifestations, ranging from passive (e.g., observing) to active (e.g., co-creation) (Maslowska et al. 2016 ). These customer social media behaviors can be either positive (e.g., sharing) or negative (e.g., create negative content), depending on customers’ attitudes and information processes during interactions (Dolan et al. 2016 ). Harmeling et al. ( 2017 ) characterize customers with positive behaviors as “pseudo marketers” because they contribute to firms’ marketing functions using their own resources, while those with negative behaviors may turn firm-created “hashtags” into “bashtags.” Drawing on uses and gratifications theory, Muntinga et al. ( 2011 ) also categorize customers’ brand-related behaviors in social media into three groups: consuming (e.g., reading a brand’s posts), contributing (e.g., rating products), and creating (e.g., publishing brand-related content).

Throughputs

Within the context of social media, both social connectedness and social interaction can be explained by social exchange theory, which proposes that social interactions are exchanges through which two parties acquire benefits (Blau 1964 ). Based on this theory, such a social exchange involves a sequence of interactions between firms and customers that are usually interdependent and contingent on others’ actions, with the goal to generate sound relationships (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005 ). Thus, successful exchanges can advance interpersonal connections (referred to as social exchange relationships) with beneficial effects for the interacting parties (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005 ).

Social connectedness

Social connectedness indicates the number of ties an individual has on social networks (Goldenberg et al. 2009 ), while Kumar et al. ( 2010 ) define connectedness with additional dimensions, including the number of connections, the strength of the connections, and the location in the network. Social media research suggests that connectedness has a significant impact on social influence. For example, Hinz et al. ( 2011 ) show that the use of “hubs” (highly connected people) in viral marketing campaigns can be eight times more successful than strategies using less connected people. Verlegh et al. ( 2013 ) also examine the impact of tie strength on making referrals in social media and confirm that people tend to interpret ambiguous information received from strong ties positively, but negatively when this information comes from weak ties.

Social interaction

Social interaction within a social media context is quite complex, as it represents multidirectional and interconnected information flows, rather than a pure firm monologue (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2013 ). This is because, on the one hand, social media have empowered customers to be equal actors in firm–customer interactions through sharing, gaming, expressing, and networking, while, on the other hand, customer–customer interactions have emerged as a growing market force, as customers can influence each other with regard to their attitudinal or behavioral changes (Peters et al. 2013 ). Chen et al. ( 2011 ) identify two types of social interactions—namely, opinion- or preference-based interactions (e.g., WOM) and action- or behavior-based interactions (e.g., observational learning)—with each requiring different strategic actions to be taken. Chahine and Malhotra ( 2018 ) also show that two-way (multiway) interaction strategies that allow reciprocity result in higher market reactions and more positive relationships.

- Customer engagement

The outputs are expressed in terms of customer engagement, which reflects the outcome of firm–customer (as well as customer–customer) connectedness and interaction in social media (Harmeling et al. 2017 ). Footnote 1 It is essentially a reflection of “the intensity of an individual’s participation in and connection with an organization’s offerings and/or organizational activities, which either the customer or the firm initiates” (Vivek et al. 2012 , p. 127). The more customers connect and interact with the firm’s activities, the higher is the level of customer engagement created (Kumar and Pansari 2016 ; Malthouse et al. 2013 ) and the higher the customer’s value addition to the firm (Pansari and Kumar 2017 ). Although the theoretical explanation of the notion of customer engagement has attracted a great deal of debate among scholars in the field, research (e.g., Brodie et al. 2011 ; Hollebeek et al. 2019 ; Kumar et al. 2019 ) has also begun adopting the service-dominant (S-D) logic (Vargo and Lusch 2004 ) because of its emphasis on customers’ interactive and value co-creation experiences in market relationships. Following the service-dominant (S-D) logic, Hollebeek et al. ( 2019 ) stress the role of customer resource integration, customer knowledge sharing, and learning as foundational in the customer engagement process, which can subsequently lead to customer individual/interpersonal operant resource development and co-creation.

Despite its pivotal role in social media marketing, extant literature has not yet attained agreement on the specific measurement of customer engagement. For example, Muntinga et al. ( 2011 ) conceptualize customer engagement in social media as comprising three stages: consuming (e.g., following, viewing content), contributing (e.g., rating, commenting), and creating (e.g., user-generated content). Maslowska et al. ( 2016 ) propose three levels of customer engagement behaviors: observing (e.g., reading content), participating (e.g., commenting on a post), and co-creating (e.g., partaking in product development). Moreover, Kumar et al. ( 2010 ) distinguish between transactional (i.e., buying the product) and non-transactional (i.e., sharing, commenting, referring, influencing) behaviors of customer engagement derived from social media connectedness and interactions.

Taxonomy of SMMSs

The distinctive differences among firms engaged in social media marketing with regard to their strategic objectives, organizational resources and capabilities, and focal industries and market structures, imply that there must also be differences in the SMMSs pursued. In this section, we first explain the criteria classifying SMMSs into different groups and then provide an analysis of their content.

Classification criteria of SMMSs

Drawing from the extant literature, we propose three important criteria that can be used to distinguish SMMSs: the nature of the firm’s strategic social media objectives with regard to using social media, the direction of interactions taking place between the firm and the customers, and the level of customer engagement achieved.

Strategic social media objectives refer to the specific organizational goals to be achieved by implementing SMMSs (Choi and Thoeni 2016 ; Felix et al. 2017 ). These can range from transactional to relational-oriented, depending on the strategist’s mental models of business–customer interactions (Rydén et al. 2015 ). Different mental models have a distinctive impact on managers’ social media sense-making, which is responsible for framing the specific role defined by social media in their marketing activities (Rydén et al. 2015 ). Rydén et al. ( 2015 ) identify four types of social media marketing objectives with four different mental models that can guide SMMSs —namely, to promote and sell (i.e., business-to-customers), to connect and collaborate (i.e., business-with-customers), to listen and learn (i.e., business-from-customers), and to empower and engage (i.e., business-for-customers).

The direction of the social media interactions can take three different forms. These include (1) one-way interaction , that is, traditional one-way communication in which the firm disseminates content (e.g., advertising) on social media and customers passively observe and react (Hoffman and Thomas 1996 ); (2) two-way interaction , that is, reciprocal and interactive communication with exchanges on social media, which can be further distinguished into firm-initiated interaction (in which the firm takes the initiative to begin the conversation) and customer participation (by liking, sharing, or commenting on the content) and customer-initiated interaction (in which the customer is the initiator of conversations by inquiring, giving feedback, or even posting negative comments about the firm, while the firm listens and responds to customer voice) (Van Noort and Willemsen 2012 ); and (3) collaborative interaction, that is, the highest level of interaction that builds on frequent and reciprocal activities in which both the firm and the customer have the power to influence each other (Joshi 2009 ).

With regard to the level of customer engagement, as noted previously, this heavily depends on the strength of connections and the intensity of interactions between the firm and the customers in social media, comprising both transactional and non-transactional elements (Kumar et al. 2010 ). Because customer engagement is the result of a dynamic and iterative process, which makes specifying the exact stage from participating to producing rather difficult (Brodie et al. 2011 ), we adopt the approach proposed by various scholars in the field (e.g., Dolan et al. 2016 ; Malthouse et al. 2013 ) to view this as a continuum, ranging from very low levels of engagement (e.g., “liking” a page) to very high levels of engagement (e.g., co-creation).

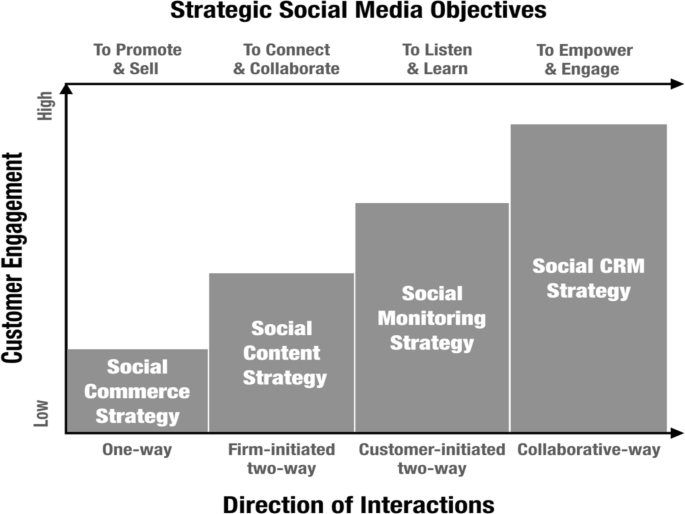

Types of SMMSs

With these three classificatory criteria, we can identify four distinct SMMSs, representing increasing levels of strategic maturity: social commerce strategy, social content strategy, social monitoring strategy, and social CRM strategy. Footnote 2 Fig. 2 illustrates this taxonomy for SMMSs, Table 3 shows the differences between these four strategies, while Appendix Table 6 provides real company examples using these strategies. In the following, we analyze each of these SMMSs by explaining their nature and characteristics, the particular role played by social media, and the specific organizational capabilities required for their adoption.

Taxonomy of social media marketing strategies

Social commerce strategy

Social commerce strategy refers to the “exchange-related activities that occur in, or are influenced by, an individual’s social network in computer-mediated social environments, whereby the activities correspond to the need recognition, pre-purchase, purchase, and post-purchase stages of a focal exchange” (Yadav et al. 2013 , p. 312). Rydén et al. ( 2015 , p. 6) claim that this way of using social media is not to create conversation and/or engagement; rather, the reasons for “the initial contact and the end purpose are to sell.” Similarly, Malthouse et al. ( 2013 ) argue that social media promotional activities do not actively engage customers because they do not make full use of the interactive role of social media. Thus, social commerce strategy can be considered as the least mature SMMS because it has a mainly transactional nature and is preoccupied with short-term goal-oriented activities (Grönroos 1994 ). It is essentially a one-way communication strategy intended to attract customers in the short run.

In this strategy, social media are claimed to be the new selling tool that has changed the way buyers and sellers interact (Marshall et al. 2012 ). They offer a new opportunity for sellers to obtain customer information and make the initial interaction with the customer more efficient (Rodriguez et al. 2012 ). Meanwhile, firms are also increasingly using social media as promising outlets for promotional/advertising purposes given their global reach (e.g., Dao et al. 2014 ; Zhang and Mao 2016 ), especially to the millennial generation (Confos and Davis 2016 ). However, as firms’ social media activities in this strategy are more transactional-oriented, customers tend to be passive and reactive. Customers contribute transactional value through purchases, but without a higher level of engagement. Therefore, we conclude that, within the context of this strategy, customers exchange their monetary resources (e.g., purchases) with the firm’s promotional offerings.

To better develop this strategy, Guesalaga ( 2016 ) highlights the need to understand the drivers of using social media in the selling process. He further stresses that personal commitment plays a crucial role in using social media as selling tools. Similarly, Järvinen and Taiminen ( 2016 ) urged for an integration of marketing with the sales department in order to gain better insights from social media marketing efforts. The importance of synergistic effects between social media and traditional media (e.g., press mentions, television, in-store promotions) has also been stressed in supporting social commerce activities (e.g., Jayson et al. 2018 ; Kumar et al. 2016 ; Stephen and Galak 2012 ). Thus, selling capabilities are crucial in this strategy, requiring the possession of adequate selling skills and the use of multiple selling channels to synergize social media effects.

Social content strategy

Social content strategy refers to “the creation and distribution of educational and/or compelling content in multiple formats to attract and/or retain customers” (Pulizzi and Barrett 2009 , p. 8). Thus, this type of SMMS aims to create and deliver timely and valuable content based on customer needs, rather than promoting products (Järvinen and Taiminen 2016 ). By attracting audiences with valuable content, the increase in customer engagement may ultimately boost product/service sales (Malthouse et al. 2013 ). Holliman and Rowley ( 2014 , p. 269) also claim that content marketing is a customer-centric strategy and describe the value of content as “being useful, relevant, compelling, and timely.” Therefore, this strategy provides a two-way communication in which firms take the initiative to deliver useful content and customers react positively to this content. The basic premises of this strategy are to create brand awareness and popularity through content virality, stimulate customer interactions, and spread positive WOM (De Vries et al. 2012 ; Swani et al. 2017 ).

Social media in this strategy have been widely used as communication tools for branding and WOM purposes (Holliman and Rowley 2014 ; Libai et al. 2013 ). On the one hand, firms generate content by their own efforts on social media (termed as ‘firm-generated’ or ‘marker-generated’ content) to actively engage consumers. On the other hand, firms encourage customers to generate the content (termed as ‘user-generated’ content) through the power of customer-to-customer interactions, as in the case of exchanging comments and sharing the brand-related content. In this way, firms provide valuable content in exchange for customer-owned resources, such as network assets and persuasion capital, to generate positive WOM and achieve a sustainable trusted brand status.

To pursue a social content strategy, firms build on capabilities focusing on how content is designed and presented (expressed in the form of a social message strategy) and how content is disseminated (expressed in the form of a seeding strategy). Thus, understanding customer engagement motivations and social media interactive characteristics is central to designing valuable content and facilitating customer interactions that would help to stimulate content sharing among customers (Malthouse et al. 2013 ). Designing compelling and valuable content in order to transform passive social media observers into active participants and collaborators is also key capability required by firms adopting this strategy (Holliman and Rowley 2014 ). Empowering customers and letting them speak for the brand is another way to engage customers with brands. Therefore, in this strategy, marketing communication capabilities are important for effective marketing content development and dissemination.

Social monitoring strategy

Social monitoring strategy refers to “a listening and response process through which marketers themselves become engaged” (Barger et al. 2016 , p. 278). In contrast with social content strategy, which is more of a “push” communication approach with content delivered, social monitoring strategy requires the firm’s active involvement in the whole communication process (from content delivery to customer response) (Barger et al. 2016 ). More specifically, social monitoring strategy is not only to observe and analyze the behaviors of customers in social media (Lamberton and Stephen 2016 ), but also to actively search for and respond to customer online needs and complaints (Van Noort and Willemsen 2012 ). A social monitoring strategy is thus characterized by a two-way communication process, in which the initiation comes from customers who comment and behave on social media, while the company takes advantage of customer behavior data to listen, learn, and react to its customers. Thus, the key objective of this strategy is to enhance customer satisfaction and cultivate stronger relationships with customers through ongoing social media listening and responding.

With today’s abundance of attitudinal and behavioral data, firms adopting this strategy use social media platforms as “tools” or “windows” to listen to customer voices and gain important market insights to support their marketing decisions (Moe and Schweidel 2017 ). Moreover, Carlson et al. ( 2018 ) argue that firms can take advantage of social media data to identify innovation opportunities and facilitate the innovation process. Hence, social media monitoring enables firms to assess consumers’ reactions, evaluate the prosperity of social media marketing initiatives, and allocate resources to different types of conversations and customer groups (Homburg et al. 2015 ). In other words, customers in this strategy are expected to be active in social media interactions, providing instantaneous and real-time feedback. This has in a way helped product development and experience improvements with resource inputs from customers’ knowledge stores.

Social monitoring strategy emphasizes the importance of carefully listening and responding to social media activities to have a better understanding of customer needs, gain critical market insights, and build stronger customer relationships (e.g., Timoshenko and Hauser 2019 ). It therefore requires firms to be actively involved in the whole communication process with customers, as customer engagement is not dependent on rewards, but is developed through the ongoing reciprocity between the firm and its customers (Barger et al. 2016 ). Thus, organizational capabilities, such as marketing sensing through effective information acquisition, interpretation and responding, are essential for the successful implementation of this strategy. More specifically, monitoring and text analysis techniques are needed to gather and capture social media data rapidly (Schweidel and Moe 2014 ). Noting the damage caused by electronic negative word of mouth (e-NWOM) on social media, firms adopting this strategy also require special capabilities to appropriately respond to customer online complaints and requests (Kim et al. 2016 ).

Social CRM strategy

Among the four SMMSs identified, social CRM strategy is characterized by the highest degree of strategic maturity, because it reflects “a philosophy and a business strategy supported by a technology platform, business rules, processes, and social characteristics, designed to engage the customer in a collaborative conversation in order to provide mutually beneficial value in a trusted and transparent business environment” (Greenberg 2009 , p. 34). The concept of social CRM is designed to combine the benefits derived from both the social media dimension (e.g., customer engagement) and the CRM dimension (e.g., customer retention) (Malthouse et al. 2013 ). In contrast with the traditional CRM approach, which assumes that customers are passive and only contribute to customer life value, social CRM strategy emphasizes the active role of customers who are empowered by social media and can make a contribution to multiple forms of value (Kumar et al. 2010 ). In brief, a social CRM strategy is a form of collaborative interaction, including firm–customer, inter-organizational, and inter-customer interactions, that are intended to engage and empower customers, so as to build mutually beneficial relationships with the firm and lead to superior performance.

Social media have become powerful enablers of CRM (Choudhury and Harrigan 2014 ). For example, Charoensukmongkol and Sasatanun ( 2017 ) argue that the integration of social media and CRM provides a possibility for firms to segment their customers based on similar characteristics, and can customize marketing offerings to the specific preferences of individual customers. With social CRM strategy, firms can enhance the likelihood of customer engagement through one-to-one social media interactions. Customers at this stage are collaborative and interactive in value creation, such as voluntarily providing innovative ideas and collaborating with brands (Jaakkola and Alexander 2014 ). Hence, besides resource like network assets, persuasion capital, and knowledge stores, engaged customers also contribute their creativity resource for value co-creation.

Social CRM capability is “a firm-level capability and refers to a firm’s competency in generating, integrating, and responding to information obtained from customer interactions that are facilitated by social media technologies” (Trainor et al. 2014 , p. 271). Therefore, firms should be extremely creative to combine social media data with its CRM system, as well as to link the massive social media data on customer activities to other data sources (e.g., customer service records) to generate better customer-learning and innovation opportunities (Choudhury and Harrigan 2014 ; Moe and Schweidel 2017 ). Social CRM strategy also emphasizes the significance of reciprocal information sharing and collaborations that are supported by the firm’s culture and commitment, operational resources, and cross-functional cooperation (Malthouse et al. 2013 ; Schultz and Peltier 2013 ). To sum up, social CRM capabilities, organizational learning capabilities connected with relationship management and innovation are essential prerequisites to building an effective social CRM strategy.

Validation of proposed SMMSs

Using the previously developed classification of SMMSs (i.e., social commerce strategy, social content strategy, social monitoring strategy, and social CRM strategy) as a basis, we reviewed the pertinent literature to collate useful knowledge supporting the content of each of these strategies. Table 4 provides a summary of the key empirical insights derived from the extant studies reviewed, together with resulting managerial lessons.

To validate the practical usefulness of our proposed classificatory framework of SMMSs, we first conducted a series of in-depth interviews with 15 social media marketing practitioners, who had their own firm/brand accounts on social media platforms, at least one year of social media marketing experience, and at least three years’ experience in their current organization (see Web Appendix 1 ). Interviewees represented companies located in China (8 companies), Finland (5 companies), and Sweden (2 companies) and involved in a variety of industries (e.g., digital tech, tourism, food, sport). All interviews were based on a specially designed guide (which was sent to participants in advance to prepare them for the interview) and were audiotaped and subsequently transcribed verbatim (see Web Appendix 2 ).

The main findings of this qualitative study are the following: (1) social media are mainly used as a key marketing channel to achieve business objectives, which, however, differentiates in terms of product-market type, organization size, and managerial mindset; (2) distinct differences exist across organizations in terms of their social media initiatives to deliver content, generate reactions, and develop social CRM; (3) there are marked variations in customer engagement levels across participant firms, resulting from the adoption of different SMMSs; (4) the firm’s propensity to use a specific SMMSs is enhanced by infrastructures, systems, and technologies that help to actively search, access, and integrate data from different sources, as well as facilitate the sharing and coordination of activities with customers; and (5) the adoption of a specific SMMS does not follow a sequential pattern in terms of strategic maturity development, but rather, depends on the firm’s strategic objectives, its willingness to commit the required resources, and the deployment of appropriate organizational capabilities.

To further confirm the existence of differences in profile characteristics among the four types of SMMSs, we conducted an electronic survey among a sample of 52 U.S. social media marketing managers who were randomly selected. For this purpose, we designed a structured questionnaire incorporating the key parameters related to SMMSs, namely firms’ strategic objectives, firms’ engagement initiatives, customers’ social media behaviors, social media resources and capabilities required, direction of interactions, and customer engagement levels (see Web Appendix 3 ).

Specifically, we found that: (1) each of the four SMMSs emphasize different types of strategic objectives, ranging from promoting and selling, in the case of social commerce strategy, to empowering and engaging in social CRM strategy; (2) experiential engagement initiatives geared to customer engagement were more evident at the advanced level, as opposed to the lower level strategies; (3) passive customer social media behaviors were more characteristic of the social commerce strategy, while more active customer behaviors were observed in the case of social CRM strategy; (4) the more advanced the maturity of the SMMS employed, the higher the level customer engagement, as well as the higher requirements in terms of organizational resources and specialized capabilities; and (5) one-way interaction was associated more with social commerce strategy, two-way interaction was more evident in the social content strategy and the social monitoring strategy, and collaborative interaction was a dominant feature in the social CRM strategy (see Web Appendix 4 ).

Future research directions

While the extant research offers insightful information and increased knowledge on SMMSs, there is still plenty of room to expand this field of research with other issues, especially given the rapidly changing developments in social media marketing practice. To gain a more accurate picture about the future of research on the subject, we sought the opinions of academic experts in the field through an electronically conducted survey among authors of academic journal articles written on the subject. We specifically asked them: (1) to suggest the three most important areas that research on SMMSs should focus on in the future; (2) within each of the areas suggested, to indicate three specific topics that need to be addressed more; and (3) within each topic, to illustrate analytical issues that warrant particular attention (see Web Appendix 5 ). Altogether, we received input from 43 social media marketing scholars who suggested 6 broad areas, 13 specific topics, and 82 focal issues for future research, which are presented in Table 5 .

Among the research issues proposed, finding appropriate metrics to measure performance in SMMSs seems to be an area to which top priority should be given. This is because performance is the ultimate outcome of these strategies, for which there is still little understanding due to the idiosyncratic nature of social media as a marketing tool (e.g., Beckers et al. 2017 ; Trainor et al. 2014 ). In particular, it is important to shed light on both short-term and long-term performance, as well as its effectiveness, efficiency, and adaptiveness aspects (e.g., Barger et al. 2016 ). Another key priority area stressed by experts in the field involves integrating to a greater extent various strategic issues regarding each of the marketing-mix elements in a social media context. This would help achieve better coordination between traditional and online marketing tools (e.g., Kolsarici and Vakratsas 2018 ; Kumar et al. 2017 ).

Respondents in our academic survey also stressed the evolutionary nature of knowledge with regard to each of the four SMMSs and proposed multiple issues for each of them. Particular attention should be paid to how inputs from customers and firms are interrelated in each of these strategies, taking into consideration the central role played by customer engagement behaviors and firm initiatives (e.g., Sheng 2019 ). Respondents also pinpointed the need for more emphasis on social CRM strategy (which is relatively under-researched), while there should also be a closer assessment of new developments in both marketing (e.g., concepts and tools) and social media (e.g., technologies and platforms) that can lead to the emergence of new types of SMMSs (e.g., Ahani et al. 2017 ; Choudhury and Harrigan 2014 ).

Respondents also noted that up to now the preparatory phase for designing SMMSs has been overlooked, and that therefore there is a need to shed more light on this because of its decisive role in achieving positive results. For example, issues relating to market/competitor analysis, macro-environmental scanning, and target marketing should be carefully studied in conjunction with formulating sound SMMSs, to better exploit opportunities and neutralize threats in a social media context (e.g., De Vries et al. 2017 ). By contrast, our survey among scholars in the field stressed the crucial nature of issues relating to SMMS implementation and control, which are of equal, or even greater, importance than those of strategy formulation (e.g., Järvinen and Taiminen 2016 ). The academics also indicated that, by their very nature, social media transcend national boundaries, thus leaving plenty of room to investigate the international ramifications of SMMSs, using cross-cultural research (e.g., Johnston et al. 2018 ).

Implications and conclusions

Theoretical implications.

Given the limited research on SMMSs, this study has several important theoretical implications. First, we are taking a step in this new theoretical direction by providing a workable definition and conceptualization of SMMS that combines both social media and marketing strategy dimensions. The study complements and extends previous research (e.g., Harmeling et al. 2017 ; Singaraju et al. 2016 ) that emphasized the value of social media as resource integrator in exchanging customer-owned resources, which can provide researchers with new angles to address the issue of integrating social media with marketing strategy. Such integrative efforts can have a meaningful long-term impact on building a new theory (or theories) of social media marketing. They also point to a deeper theoretical understanding of the roles played by resource identification, utilization, and reconfiguration in a SMMS context.

We have also extended the idea of “social interaction” and “social connectedness” in a social media context, which is critical because the power of a customer enabled by social media connections and interactions is of paramount importance in explaining the significance of SMMSs (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2013 ). More importantly, our study suggests that firms should take the initiative to motivate and engage customers, which will lead to wider and more extensive interactions. In particular, we show that a firm can leverage its social media usage through the use of different engagement initiatives to enforce customer interactivity and interconnectedness. Such enquiries can provide useful theoretical insights into the strategic marketing role played by social media in today’s highly digitalized and globalized world.

We are also furthering the customer engagement literature by proposing an SMMS developmental process. As firm–customer relationships evolve in a social media era, it is critical to identify those factors that have an impact on customer engagement. Although prior studies (e.g., Harmeling et al. 2017 ; Pansari and Kumar 2017 ) have demonstrated the engagement value contributed by customers and the need for engagement initiatives taken by firms, we are extending this idea to provide a more holistic view by highlighting the role of insights from both firms and customers to better understand the dynamics of SMMS formulation. We also suggest certain theories to specifically explain the role played by each of the components of the process in developing sound SMMSs. We capture the unique characteristics of social media by suggesting that these networks and interactions are tightly interrelated with the outcome of SMMS, which is customer engagement. Our proposed SMMS developmental process may therefore provide critical input for new studies focusing on customer engagement research.

Finally, we build on various criteria to distinguish among four SMMSs, each representing a different level of strategic maturity. We show that a SMMS is not homogeneous, but needs to be understood in a wider, more nuanced way, as having different strategies relying on different goals and deriving insights from firms and their customers, ultimately leading to different customer engagement levels. In this regard, the identification of the key SMMSs stemming from our analysis can serve as the basis for developing specific marketing strategy constructs and scales within a social media context. We also indicate that different SMMSs can be implemented and yield superior competitive advantage only when the firm is in a position to devote to it the right amount and type of resources and capabilities (e.g., Gao et al. 2018 ; Kumar and Pansari 2016 ).

Managerial implications

Our study also has serious implications for managers. First, our analysis revealed that the ever-changing digital landscape on a global scale calls for a reassessment of the ways to strategically manage brands and customers in a social media context. This requires companies to understand the different goals for using social media and to develop their strategies accordingly. As a starting point, firms could explore customer motivations for using social media and effectively deploy the necessary resources to accommodate these motivations. They should also think carefully about how to engage customers when implementing their marketing strategies, because social media become resource integrators only when customers interact with and provide information on them (Singaraju et al. 2016 ).

Managers need to set objectives at the outset to guide the effective development, implementation, and control of SMMSs. Our study suggests four key SMMSs achieving different business goals. For example, the goal of social commerce strategy is to attract customers with transactional interests, that of social content strategy and social monitoring strategy is to deliver valuable content and service to customers, and that of social CRM strategy is to build mutually beneficial customer relationships by integrating social media data with current organizational processes. Unfortunately, many companies, especially smaller ones, tend to create their social media presence for a single purpose only: to disseminate massive commercial information on their social media web pages in the hope of attracting customers, even though these customers may find commercially intensive content annoying.

This study also suggests that social media investments should focus on the integration of social media platforms with internal company systems to build special social media capabilities (i.e., creating, combining, and reacting to information obtained from customer interactions on social media). Such capabilities are vital in developing a sustainable competitive advantage, superior market and financial performance. However, to achieve this, firms must have the right organizational structural and cultural transformation, as well as substantial management commitment and continuous investment.

Lastly, social media have become powerful tools for CRM, helping to transform it from traditional one-way interaction to collaborative interaction. This implies that customer engagement means not only encouraging customer engagement on social media, but also proactively learning from and collaborating with customers. As Pansari and Kumar et al. ( 2017 ) indicate, customer engagement can contribute both directly (e.g., purchase) and indirectly (e.g., customer knowledge value) to the firm. Therefore, interacting with customers via social media provides tremendous opportunities for firms to learn more about their customers and opens up new possibilities for product/service co-creation.

Conclusions

The exploding use of social media in the past decade has underscored the need for guidance on how to build SMMSs that foster relationships with customers, advance customer engagement, and increase marketing performance. However, a comprehensive definition, conceptualization, and framework to guide the analysis and development of SMMSs are lacking. This can be attributed to the recent introduction of social media as a strategic marketing tool, while both academics and practitioners still lack the necessary knowledge on how to convert social media data into actionable strategic marketing tools (Moe and Schweidel 2017 ). This insufficiency also stems from the fact that the adoption of more advanced SMMSs requires the possession of specific organizational capabilities that can be used to leverage social media, with the support of a culture that encourages breaking free from obsolete mindsets, emphasizing employee skills with intelligence in data and customer analytical insights, and operational excellence in organizational structure and business processes (Malthouse et al. 2013 ).

Our study takes the first step toward addressing this issue and provides useful guidelines for leveraging social media use in strategic marketing. In particular, we provide a systematic consolidation and extension of the extant pertinent SMMS literature to offer a robust definition, conceptualization, taxonomy, and validation of SMMSs. Specifically, we have amply demonstrated that the mere use of social media alone does not generate customer value, which instead is attained through the generation of connections and interactions between the firm and its customers, as well as among customers themselves. These generated social networks and influences can subsequently be used strategically for resource transformation and exchanges between the interacting parties. Our conceptualization of the SMMS developmental process also suggests that firms first need to recognize customers’ motivations to engage in brand-related social media activities and encourage their voluntary contributions.

Although the four SMMSs identified in our study (i.e., social commerce strategy, social content strategy, social monitoring strategy, and social CRM strategy) denote progressing levels of strategic maturity, their adoption does not follow a sequential pattern. As our validation procedures revealed, this will be determined by the firm’s strategic objectives, resources, and capabilities. Moreover, the success of the various SMMSs will depend on the firm’s ability to identify and leverage customer-owned resources, as in the case of transforming customers from passive receivers of the firm’s social media offerings to active value contributors. It will also depend on the firm’s willingness to allocate resources in order to foster collaborative conversations, develop appropriate responses, and enhance customer relationships. These will all ultimately help to build a sustainable competitive advantage and enhance business performance.

Although in our conceptualization of the process of developing SMMSs we treat customer engagement as the output of this process, we fully acknowledge that firms’ ultimate objective to engage in social media marketing activities is to improve their market (e.g., customer equity) and financial (e.g., revenues) performance. In fact, extant social media marketing research (e.g., Kumar et al. 2010 ; Kumar and Pansari 2016 ; Harmeling et al. 2017 ) repeatedly stresses the conducive role of customer engagement in ensuring high performance results.

SMMSs are difficult to operationalize by focusing solely on the elements of the marketing mix (i.e., product, price, distribution, and promotion), mainly because many other important parameters are involved in their conceptualization, such as relationship management, market development, and business innovation issues. However, each SMMS seems to have a different marketing mix focus, with social commerce strategy emphasizing advertising and sales, social content strategy emphasizing branding and communication, social monitoring strategy emphasizing service and product development, and social CRM strategy emphasizing customer management and innovation.

Acommerce (2019). How L’Oréal uses e-commerce’s social commerce to simplify transaction and increase customer engagement. Available at https://www.acommerce.asia/case-study-loreal-social-commerce/ .

Ahani, A., Rahim, N. Z. A., & Nilashi, M. (2017). Forecasting social CRM adoption in SMEs: A combined SEM-neural network method. Computers in Human Behavior, 75 , 560–578.

Article Google Scholar

Alharthi, A., Krotov, V., & Bowman, M. (2017). Addressing barriers to big data. Business Horizons, 60 (3), 285–292.

Aral, S., & Walker, D. (2014). Tie strength, embeddedness, and social influence: A large-scale networked experiment. Management Science, 60 (6), 1352–1370.

Aral, S., Dellarocas, C., & Godes, D. (2013). Social media and business transformation: A framework for research. Information Systems Research, 24 (1), 3–13.

Barger, V., Peltier, J. W., & Schultz, D. E. (2016). Social media and consumer engagement: A review and research agenda. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 10 (4), 268–287.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 , 99–120.

Beckers, S. F. M., van Doorn, J., & Verhoef, P. C. (2017). Good, better, engaged? The effect of company-initiated customer engagement behavior on shareholder value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (3), 366–383.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life . New York: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Juric, B., & Ilic, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14 (3), 252–271.

Carlson, J., Rahman, M., Voola, R., & De Vries, N. (2018). Customer engagement behaviors in social media: Capturing innovation opportunities. Journal of Services Marketing, 32 (1), 83–94.

Chahine, S., & Malhotra, N. K. (2018). Impact of social media strategies on stock price: The case of twitter. European Journal of Marketing, 52 (7–8), 1526–1549.

Charoensukmongkol, P., & Sasatanun, P. (2017). Social media use for CRM and business performance satisfaction: The moderating roles of social skills and social media sales intensity. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22 (1), 25–34.

Chen, Y., Wang, Q., & Xie, J. (2011). Online social interactions: A natural experiment on word of mouth versus observational learning. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (2), 238–254.

Choi, Y., & Thoeni, A. (2016). Social media: Is this the new organizational stepchild? European Business Review, 28 (1), 21–38.

Choudhury, M. M., & Harrigan, P. (2014). CRM to social CRM: The integration of new technologies into customer relationship management. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 22 (2), 149–176.

Confos, N., & Davis, T. (2016). Young consumer-brand relationship building potential using digital marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 50 (11), 1993–2017.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31 (6), 874–900.

Dao, W. V. T., Le, A. N. H., Cheng, J. M. S., & Chen, D. C. (2014). Social media advertising value: The case of transitional economies in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Advertising, 33 (2), 271–294.

De Vries, L., Gensler, S., & Leeflang, P. S. H. (2012). Popularity of brand posts on brand fan pages: An investigation of the effects of social media marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26 (2), 83–91.

De Vries, L., Gensler, S., & Leeflang, P. S. H. (2017). Effects of traditional advertising and social messages on brand-building metrics and customer acquisition. Journal of Marketing, 81 (5), 1–15.

Dolan, R., Conduit, J., Fahy, J., & Goodman, S. (2016). Social media engagement behavior: A uses and gratifications perspective. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24 (3–4), 261–277.

Effing, R., & Spil, T. A. M. (2016). The social strategy cone: Towards a framework for evaluating social media strategies. International Journal of Information Management, 36 (1), 1–8.

Fehrer, J. A., Woratschek, H., Germelmann, C. C., & Brodie, R. J. (2018). Dynamics and drivers of customer engagement: Within the dyad and beyond. Journal of Service Management, 29 (3), 443–467.

Felix, R., Rauschnabel, P. A., & Hinsch, C. (2017). Elements of strategic social media marketing: A holistic framework. Journal of Business Research, 70 , 118–126.

Gao, H., Tate, M., Zhang, H., Chen, S., & Liang, B. (2018). Social media ties strategy in international branding: An application of resource-based theory. Journal of International Marketing, 26 (3), 45–69.

Gnizy, I. (2019). Big data and its strategic path to value in international firms. International Marketing Review, 36 (3), 318–341.

Goldenberg, J., Han, S., Lehmann, D. R., & Hong, J. W. (2009). The role of hubs in the adoption process. Journal of Marketing, 73 (2), 1–13.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78 (6), 1360–1380.

Greenberg, P. (2009). CRM at the speed of light: Social CRM strategies, tools, and techniques for engaging consumers . New York: McGraw-Hill Osborne Media.

Griffith, G. (2016). Get to know customers better by monitoring social media sentiment. Available at https://www.raconteur.net/business-innovation/get-to-know-customers-better-by-monitoring-social-media-sentiment .

Griffiths, M., & Mclean, R. (2015). Unleashing corporate communications via social media: A UK study of brand management and conversations with customers. Journal of Customer Behavior, 14 (2), 147–162.

Grönroos, C. (1991). The marketing strategy continuum: Towards a marketing concept for the 1990s. Management Decision, 29 (1), 72–76.

Grönroos, C. (1994). From marketing mix to relationship marketing. Management Decision, 32 (2), 4–20.

Guesalaga, R. (2016). The use of social media in sales: Individual and organizational antecedents, and the role of customer engagement in social media. Industrial Marketing Management, 54 , 71–79.

Gummesson, E., & Mele, C. (2010). Marketing as value co-creation through network interaction and resource integration. Journal of Business Market Management, 4 (4), 181–198.

Hamilton, M., Kaltcheva, V. D., & Rohm, A. J. (2016). Social media and value creation: The role of interaction satisfaction and interaction immersion. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 36 , 121–133.

Harmeling, C. M., Moffett, J. W., Arnold, M. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2017). Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (3), 312–335.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Hofacker, C. F., & Bloching, B. (2013). Marketing the pinball way: Understanding how social media change the generation of value for consumers and companies. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27 (4), 237–241.

Hinz, O., Skiera, B., Barrot, C., & Becker, J. U. (2011). Seeding strategies for viral marketing: An empirical comparison. Journal of Marketing, 75 (6), 55–71.

Hoffman, D. L., & Thomas, P. N. (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing, 60 (3), 50–69.

Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2019). S-D logic-informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 , 161–185.

Holliman, G., & Rowley, J. (2014). Business to business digital content marketing: Marketers’ perceptions of best practice. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 8 (4), 269–293.

Homburg, C., Ehm, L., & Artz, M. (2015). Measuring and managing consumer sentiment in an online community environment. Journal of Marketing Research, 52 (5), 629–641.

Hunt, S. D., & Morgan, R. M. (1995). The comparative advantage theory of competition. Journal of Marketing, 59 (2), 1–15.

Hunt, S. D., Arnett, D. B., & Madhavaram, S. (2006). The explanatory foundations of relationship marketing theory. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21 (2), 72–87.

Jaakkola, E., & Alexander, M. (2014). The role of customer engagement behavior in value co-creation: A service system perspective. Journal of Service Research, 17 (3), 247–261.

Järvinen, J., & Taiminen, H. (2016). Harnessing marketing automation for B2B content marketing. Industrial Marketing Management, 54 , 164–175.

Jayson, R., Block, M. P., & Chen, Y. (2018). How synergy effects of paid and digital owned media influence brand sales considerations for marketers when balancing media spend. Journal of Advertising Research, 58 (1), 77–89.

Johnston, W. J., Khalil, S., Le, A. N. H., & Cheng, J. M. S. (2018). Behavioral implications of international social media advertising: An investigation of intervening and contingency factors. Journal of International Marketing, 26 (2), 43–61.

Joshi, A. W. (2009). Continuous supplier performance improvement: Effects of collaborative communication and control. Journal of Marketing, 73 (1), 133–150.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53 (1), 59–68.

Katona, Z., Zubcsek, P. P., & Sarvary, M. (2011). Network effects and personal influences: The diffusion of an online social network. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (3), 425–443.

Katz, E., Gurevitch, M., & Haas, H. (1973). On the use of mass media for important things. American Sociological Review, 38 , 164–181.

Kim, S. J., Wang, R. J. H., Maslowska, E., & Malthouse, E. C. (2016). “Understanding a fury in your words”: The effects of posting and viewing electronic negative word-of-mouth on purchase behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior, 54 , 511–521.

Kolsarici, C., & Vakratsas, D. (2018). Synergistic, antagonistic, and asymmetric media interactions. Journal of Advertising, 47 (3), 282–300.

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive advantage through engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53 (4), 497–514.

Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmans, S. (2010). Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. Journal of Service Research, 13 (3), 297–310.

Kumar, V., Bhaskaran, V., Mirchandani, R., & Shah, M. (2013). Creating a measurable social media marketing strategy: Increasing the value and ROI of intangibles and tangibles for hokey pokey. Marketing Science, 32 (2), 194–212.

Kumar, A., Bezawada, R., Rishika, R., Janakiraman, R., & Kannan, P. K. (2016). From social to sale: The effects of firm-generated content in social media on customer behavior. Journal of Marketing, 80 (1), 7–25.

Kumar, V., Choi, J. W. B., & Greene, M. (2017). Synergistic effects of social media and traditional marketing on brand sales: Capturing the time-varying effects. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 268–288.

Kumar, V., Rajan, B., Gupta, S., & Dalla Pozza, I. (2019). Customer engagement in service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47 (1), 138–160.

Lamberton, C., & Stephen, A. T. (2016). A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. Journal of Marketing, 80 (6), 146–172.

Libai, B., Bolton, R., Bugel, M. S., de Ruyter, K., Gotz, O., Risselada, H., & Stephen, A. T. (2010). Customer-to-customer interactions: Broadening the scope of word of mouth research. Journal of Service Research, 13 (3), 267–282.

Libai, B., Muller, E., & Peres, R. (2013). Decomposing the value of word-of-mouth seeding programs: Acceleration versus expansion. Journal of Marketing Research, 50 (2), 161–176.

Malthouse, E. C., Haenlein, M., Skiera, B., Wege, E., & Zhang, M. (2013). Managing customer relationships in the social media era: Introducing the social CRM house. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27 (4), 270–280.

Marshall, G. W., Moncrief, W. C., Rudd, J. M., & Lee, N. (2012). Revolution in sales : The impact of social media and related technology on the selling environment. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32 (3), 349–363.

Maslowska, E., Malthouse, E. C., & Collinger, T. (2016). The customer engagement ecosystem. Journal of Marketing Management, 32 (5–6), 469–501.

Micu, A., Micu, A. E., Geru, M., & Lixandroiu, R. C. (2017). Analyzing user sentiment in social media: Implications for online marketing strategy. Psychology & Marketing, 34 (12), 1094–1100.

Moe, W. W., & Schweidel, D. A. (2017). Opportunities for innovation in social media analytics. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34 (5), 697–702.

Moorman, C., & Day, G. S. (2016). Organizing for marketing excellence. Journal of Marketing, 80 (6), 6–35.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. (1999). Relationship-based competitive advantage: The role of relationship marketing in marketing strategy. Journal of Business Research, 46 (3), 281–290.

Muller, E., & Peres, R. (2019). The effect of social networks structure on innovation performance: A review and directions for research. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36 (1), 3–19.

Muntinga, D. G., Moorman, M., & Smit, E. G. (2011). Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. International Journal of Advertising, 30 (1), 13–46.

Nair, H. S., Manchanda, P., & Bhatia, T. (2010). Asymmetric social interactions in physician prescription behavior: The role of opinion leaders. Journal of Marketing Research, 47 (5), 883–895.

Naylor, R. W., Lamberton, C. P., & West, P. M. (2012). Beyond the “like” button: The impact of mere virtual presence on brand evaluations and purchase intentions in social media settings. Journal of Marketing, 76 (6), 105–120.