21 Action Research Examples (In Education)

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

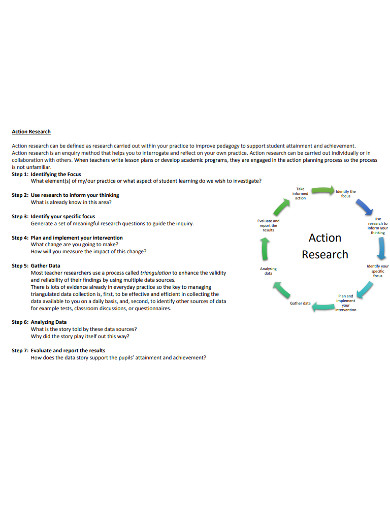

Action research is an example of qualitative research . It refers to a wide range of evaluative or investigative methods designed to analyze professional practices and take action for improvement.

Commonly used in education, those practices could be related to instructional methods, classroom practices, or school organizational matters.

The creation of action research is attributed to Kurt Lewin , a German-American psychologist also considered to be the father of social psychology.

Gillis and Jackson (2002) offer a very concise definition of action research: “systematic collection and analysis of data for the purpose of taking action and making change” (p.264).

The methods of action research in education include:

- conducting in-class observations

- taking field notes

- surveying or interviewing teachers, administrators, or parents

- using audio and video recordings.

The goal is to identify problematic issues, test possible solutions, or simply carry-out continuous improvement.

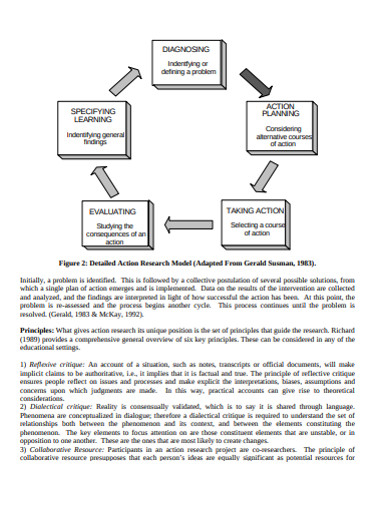

There are several steps in action research : identify a problem, design a plan to resolve, implement the plan, evaluate effectiveness, reflect on results, make necessary adjustment and repeat the process.

Action Research Examples

- Digital literacy assessment and training: The school’s IT department conducts a survey on students’ digital literacy skills. Based on the results, a tailored training program is designed for different age groups.

- Library resources utilization study: The school librarian tracks the frequency and type of books checked out by students. The data is then used to curate a more relevant collection and organize reading programs.

- Extracurricular activities and student well-being: A team of teachers and counselors assess the impact of extracurricular activities on student mental health through surveys and interviews. Adjustments are made based on findings.

- Parent-teacher communication channels: The school evaluates the effectiveness of current communication tools (e.g., newsletters, apps) between teachers and parents. Feedback is used to implement a more streamlined system.

- Homework load evaluation: Teachers across grade levels assess the amount and effectiveness of homework given. Adjustments are made to ensure a balance between academic rigor and student well-being.

- Classroom environment and learning: A group of teachers collaborates to study the impact of classroom layouts and decorations on student engagement and comprehension. Changes are made based on the findings.

- Student feedback on curriculum content: High school students are surveyed about the relevance and applicability of their current curriculum. The feedback is then used to make necessary curriculum adjustments.

- Teacher mentoring and support: New teachers are paired with experienced mentors. Both parties provide feedback on the effectiveness of the mentoring program, leading to continuous improvements.

- Assessment of school transportation: The school board evaluates the efficiency and safety of school buses through surveys with students and parents. Necessary changes are implemented based on the results.

- Cultural sensitivity training: After conducting a survey on students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences, the school organizes workshops for teachers to promote a more inclusive classroom environment.

- Environmental initiatives and student involvement: The school’s eco-club assesses the school’s carbon footprint and waste management. They then collaborate with the administration to implement greener practices and raise environmental awareness.

- Working with parents through research: A school’s admin staff conduct focus group sessions with parents to identify top concerns.Those concerns will then be addressed and another session conducted at the end of the school year.

- Peer teaching observations and improvements: Kindergarten teachers observe other teachers handling class transition techniques to share best practices.

- PTA surveys and resultant action: The PTA of a district conducts a survey of members regarding their satisfaction with remote learning classes.The results will be presented to the school board for further action.

- Recording and reflecting: A school administrator takes video recordings of playground behavior and then plays them for the teachers. The teachers work together to formulate a list of 10 playground safety guidelines.

- Pre/post testing of interventions: A school board conducts a district wide evaluation of a STEM program by conducting a pre/post-test of students’ skills in computer programming.

- Focus groups of practitioners : The professional development needs of teachers are determined from structured focus group sessions with teachers and admin.

- School lunch research and intervention: A nutrition expert is hired to evaluate and improve the quality of school lunches.

- School nurse systematic checklist and improvements: The school nurse implements a bathroom cleaning checklist to monitor cleanliness after the results of a recent teacher survey revealed several issues.

- Wearable technologies for pedagogical improvements; Students wear accelerometers attached to their hips to gain a baseline measure of physical activity.The results will identify if any issues exist.

- School counselor reflective practice : The school counselor conducts a student survey on antisocial behavior and then plans a series of workshops for both teachers and parents.

Detailed Examples

1. cooperation and leadership.

A science teacher has noticed that her 9 th grade students do not cooperate with each other when doing group projects. There is a lot of arguing and battles over whose ideas will be followed.

So, she decides to implement a simple action research project on the matter. First, she conducts a structured observation of the students’ behavior during meetings. She also has the students respond to a short questionnaire regarding their notions of leadership.

She then designs a two-week course on group dynamics and leadership styles. The course involves learning about leadership concepts and practices . In another element of the short course, students randomly select a leadership style and then engage in a role-play with other students.

At the end of the two weeks, she has the students work on a group project and conducts the same structured observation as before. She also gives the students a slightly different questionnaire on leadership as it relates to the group.

She plans to analyze the results and present the findings at a teachers’ meeting at the end of the term.

2. Professional Development Needs

Two high-school teachers have been selected to participate in a 1-year project in a third-world country. The project goal is to improve the classroom effectiveness of local teachers.

The two teachers arrive in the country and begin to plan their action research. First, they decide to conduct a survey of teachers in the nearby communities of the school they are assigned to.

The survey will assess their professional development needs by directly asking the teachers and administrators. After collecting the surveys, they analyze the results by grouping the teachers based on subject matter.

They discover that history and social science teachers would like professional development on integrating smartboards into classroom instruction. Math teachers would like to attend workshops on project-based learning, while chemistry teachers feel that they need equipment more than training.

The two teachers then get started on finding the necessary training experts for the workshops and applying for equipment grants for the science teachers.

3. Playground Accidents

The school nurse has noticed a lot of students coming in after having mild accidents on the playground. She’s not sure if this is just her perception or if there really is an unusual increase this year. So, she starts pulling data from the records over the last two years. She chooses the months carefully and only selects data from the first three months of each school year.

She creates a chart to make the data more easily understood. Sure enough, there seems to have been a dramatic increase in accidents this year compared to the same period of time from the previous two years.

She shows the data to the principal and teachers at the next meeting. They all agree that a field observation of the playground is needed.

Those observations reveal that the kids are not having accidents on the playground equipment as originally suspected. It turns out that the kids are tripping on the new sod that was installed over the summer.

They examine the sod and observe small gaps between the slabs. Each gap is approximately 1.5 inches wide and nearly two inches deep. The kids are tripping on this gap as they run.

They then discuss possible solutions.

4. Differentiated Learning

Trying to use the same content, methods, and processes for all students is a recipe for failure. This is why modifying each lesson to be flexible is highly recommended. Differentiated learning allows the teacher to adjust their teaching strategy based on all the different personalities and learning styles they see in their classroom.

Of course, differentiated learning should undergo the same rigorous assessment that all teaching techniques go through. So, a third-grade social science teacher asks his students to take a simple quiz on the industrial revolution. Then, he applies differentiated learning to the lesson.

By creating several different learning stations in his classroom, he gives his students a chance to learn about the industrial revolution in a way that captures their interests. The different stations contain: short videos, fact cards, PowerPoints, mini-chapters, and role-plays.

At the end of the lesson, students get to choose how they demonstrate their knowledge. They can take a test, construct a PPT, give an oral presentation, or conduct a simulated TV interview with different characters.

During this last phase of the lesson, the teacher is able to assess if they demonstrate the necessary knowledge and have achieved the defined learning outcomes. This analysis will allow him to make further adjustments to future lessons.

5. Healthy Habits Program

While looking at obesity rates of students, the school board of a large city is shocked by the dramatic increase in the weight of their students over the last five years. After consulting with three companies that specialize in student physical health, they offer the companies an opportunity to prove their value.

So, the board randomly assigns each company to a group of schools. Starting in the next academic year, each company will implement their healthy habits program in 5 middle schools.

Preliminary data is collected at each school at the beginning of the school year. Each and every student is weighed, their resting heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol are also measured.

After analyzing the data, it is found that the schools assigned to each of the three companies are relatively similar on all of these measures.

At the end of the year, data for students at each school will be collected again. A simple comparison of pre- and post-program measurements will be conducted. The company with the best outcomes will be selected to implement their program city-wide.

Action research is a great way to collect data on a specific issue, implement a change, and then evaluate the effects of that change. It is perhaps the most practical of all types of primary research .

Most likely, the results will be mixed. Some aspects of the change were effective, while other elements were not. That’s okay. This just means that additional modifications to the change plan need to be made, which is usually quite easy to do.

There are many methods that can be utilized, such as surveys, field observations , and program evaluations.

The beauty of action research is based in its utility and flexibility. Just about anyone in a school setting is capable of conducting action research and the information can be incredibly useful.

Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Gillis, A., & Jackson, W. (2002). Research Methods for Nurses: Methods and Interpretation . Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of SocialIssues, 2 (4), 34-46.

Macdonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13 , 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37 Mertler, C. A. (2008). Action Research: Teachers as Researchers in the Classroom . London: Sage.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

2 thoughts on “21 Action Research Examples (In Education)”

Where can I capture this article in a better user-friendly format, since I would like to provide it to my students in a Qualitative Methods course at the University of Prince Edward Island? It is a good article, however, it is visually disjointed in its current format. Thanks, Dr. Frank T. Lavandier

Hi Dr. Lavandier,

I’ve emailed you a word doc copy that you can use and edit with your class.

Best, Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

100 Questions (and Answers) About Action Research

- By: Luke Duesbery & Todd Twyman

- Publisher: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Series: SAGE 100 Questions and Answers

- Publication year: 2020

- Online pub date: February 08, 2021

- Discipline: Business and Management

- Methods: Action research , Research questions , Research design

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781544305455

- Keywords: decision making , health sciences , journals , social justice , social media , students , teaching Show all Show less

- Print ISBN: 9781544305431

- Online ISBN: 9781071849408

- Buy the book icon link

Subject index

100 Questions (and Answers) About Action Research identifies and answers the essential questions on the process of systematically approaching your practice from an inquiry-oriented perspective, with a focus on improving that practice. This unique text offers progressive instructors an alternative to the research status quo and serves as a reference for readers to improve their practice as advocates for those they serve. The Question and Answer format makes this an ideal supplementary text for traditional research methods courses, and also a helpful guide for practitioners in education, social work, criminal justice, health, business, and other applied disciplines.

Front Matter

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- What Is This Book About?

- What Is Action Research, and Where Did It Come From?

- What Are the Key Features of Action Research I Should Remember?

- How Is Action Research Like and Unlike Other Research?

- How Do You Choose Your Action Research Style?

- Why Should I Bother With Action Research?

- How Is Action Research Cyclical?

- How Much Time Does an Action Research Project Really Take?

- What Is an Action Research Disposition?

- Why Is Knowing Yourself Important While Doing Action Research?

- Do I Need to Know About Statistics for Action Research?

- What’s the Difference Between Theory and Conceptual Frameworks in Action Research?

- How Does Action Research Fit in Education?

- How Does Action Research Fit in the Health Sciences?

- How Does Action Research Fit in the Behavioral and Social Sciences?

- How Does Action Research Fit in Business, Management, and Industry?

- How Can a Gender Theory Approach Impact Action Research?

- How Does Critical Race Theory Impact Action Research?

- What Is the Difference Between Exploratory and Confirmatory Action Research?

- What Are the Weaknesses of Action Research?

- How Can Action Research Be a Form of Social Justice?

- Why Is Ethics Important in Educational Research and Action Research in Particular?

- Do I Need to Get Some Kind of Approval for My Action Research?

- What Is Informed Consent, and Why Is It Important?

- Who Are the Stakeholders in Action Research, and Why Are They Important?

- Why Is It Important to Strive for Confidentiality and Anonymity?

- Should I Treat Children in Action Research Differently Than Adults?

- What Does a Sample Consent Letter Look Like?

- What’s a Literature Review, and Do I Need One?

- What Are the Steps in Doing an Efficient Literature Review or Synthesis?

- Should I Read Action Research Articles?

- How Do I Evaluate the Articles I Find?

- How Do I Plan for My Action Research Project Before I Start?

- How Do I Narrow Down My Topic?

- How Do I Make Sure My Research Is Rigorous?

- What Do Good Action Research Questions Look Like?

- What Is the Difference Between Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Action Research Design?

- What Are Common Qualitative Research Designs in Action Research?

- What Are Common Quantitative Research Designs in Action Research?

- What Are Some Better Quantitative Action Research Designs?

- What Are Some Common Mixed-Method Action Research Designs?

- Can a Program Evaluation Also Be Action Research?

- How Do I Choose My Action Research Design?

- What Are Referents, and Which Work Best With Action Research?

- How Do I Randomly Choose My Participants?

- How Do I Not Randomly Choose My Participants?

- How Do I Create Groups?

- What Is a Case Study?

- When and How Would I Use Interviews?

- In General, What Are the Different Kinds of Interviews?

- How Do I Write Interview Questions and Interpret the Answers?

- Why Would I Use Focus Groups?

- How Do I Conduct Focus Groups?

- How Do Ethnographic Data Collection Methods Support Action Research?

- Can You Tell Me What I Need to Know About Surveys?

- How Do I Write Good Survey Questions?

- Can I Use Direct Observations in Action Research?

- What Are the Elements of Conducting Effective Observations?

- How Do Interval Observations Enrich Action Research?

- What Are Experimental Designs, and Are They Practical in Action Research?

- What Are Quasi-experimental Designs, and Where Do They Fit in?

- Can You Tell Me More About Action Research Designs That Use Groups?

- Do I Collect Data Once or a Bunch of Times?

- Are Single-Case and Single-Subject Designs Different?

- I Wrote My Question and Chose My Design. What Kind of Data Do I Need?

- How Are Descriptive and Inferential Statistics Different?

- What Is Visual Data Analysis?

- What Does It Mean to Triangulate My Data?

- What’s the Big Deal About Reliability?

- What’s the Big Deal About Validity?

- Why Do I Need to Care About Internal Validity?

- What Kind of Threats to Internal Validity Are Common in Action Research?

- What Are Blocking Variables?

- What Are Ordinal, Interval, and Categorical Data Types, and Which Works Best With Action Research?

- Does Generalizability Matter in Action Research?

- Now I Have All These Data. What Is the Best Way to Present My Results?

- How Do I Tell a Story With My Data?

- What Is the Difference Between the Mean and Median, and Why Is It Important?

- How Do Inferential Statistics Work?

- How Can I Use Inferential Statistics in My Action Research?

- What Is an Effect Size, and Who Is Cohen?

- How Do I Deal With Missing Data?

- What Are Some Good Action Research Analytic Tools I Can Use?

- Why Is Using Data Displays an Important Step?

- What Are the Elements of a Good Table?

- What Are the Elements of a Good Graph?

- How Do I Evaluate the Quality of My Action Research Project?

- Now That I Am Done, How Do I Add Value to the Field?

- What Professional Organizations Are Available to Give Me Support?

- Are Social Media Outlets Appropriate for Sharing My Action Research?

- Can I Formally Publish My Action Research Project?

- What Are the Most Helpful Action Research Journals?

- Should I Repeat (Replicate) My Action Research Project?

- Is Action Research in Any Way Political? How Do I Navigate That?

- How Can I Create an Inquiry-Oriented Disposition in My Everyday Life?

- Why Develop an Action Research Community?

- Why Would I Want or Need to Write a Report on My Action Research?

- What Are the Key Elements of an Action Research Report?

- I Really Liked Learning About Action Research. What Is Next?

- What Other Books in This Series Might Interest Me, and How Do They Fit Together?

Back Matter

- Appendix : Important Action Research Literature

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Types, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

By engaging in cycles of planning, observation, action, and reflection, action research enables participants to identify challenges, implement solutions, and evaluate outcomes. This approach generates practical knowledge and empowers individuals and organizations to effect meaningful change in their contexts.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system .

What is Action Research?

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research , it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

Important Types of Action Research

Here are the main types of action research:

1. Practical Action Research

It focuses on solving specific problems within a local context, often involving teachers or practitioners seeking to improve practices.

2. Participatory Action Research (PAR)

A research process in which people, staff, and activists work together to generate knowledge from a study on an issue that adds value and supports their actions for social change.

3. Critical Action Research

Built to address power and social injustices in light of the Hegemonic Underpinnings, this research facilitates a callback, self-reflection, and thorough societal reformations.

4. Collaborative Action Research

In this form of research, a team of practitioners joins to do project work as part of an overall effort to improve. The work continues into the analysis phase with these same folks across all stages.

5. Reflective Action Research

This kind of research emphasizes individual or group reflection on practices. The key to this model is that it encourages reflective and deliberate practice, thus promoting learning and unfolding within ongoing experiences.

6. Transformative Action Research

This model empowers participants to address issues within their communities related to social justice and transformation.

Each type serves different contexts and goals, contributing to the overall effectiveness of action research.

Stages of Action Research

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation . This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

The Steps of Conducting Action Research

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

1. Identify The Action Research Question or Problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

2. Review Existing Knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design .

3. Plan The Research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools , and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

4. Collect Data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups . Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

5. Analyze The Data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

6. Reflect on The Findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

7. Develop an Action Plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

8. Implement The Action Plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

9. Evaluate and Monitor Progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

10. Reflect and Iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Examples of Action Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Action Research

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

Why QuestionPro Research Suite is Great for Action Research?

QuestionPro Research Suite is an ideal choice for action research, which typically involves multiple rounds of data collection , analysis, and intervention cycles. This is one reason it might be great for that:

01. Data Collection

QuestionPro offers flexible and adaptable methods for data dissemination. You can collect and store crucial business data from secure, personalized questionnaires , and distribute them through emails, SMSs, or even popular social media platforms and mobile apps.

This adaptability is particularly useful for action research, which often requires a variety of data collection techniques.

02. Advanced Analysis Tools

- Efficient Data Analysis: Built-in tools simplify both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

- Powerful Segmentation: Cross-tabulation lets you compare and track changes across cycles.

- Reliable Insights: This robust toolset enhances confidence in research outcomes.

03. Collaboration and Real-Time Reporting

Multiple researchers can collaborate within the platform, sharing permissions and changes in real-time while creating reports. Asynchronous collaboration: Conversation threads and comments can be in one place, ensuring all team members stay updated and are aligned with stakeholders throughout each action research phase.

04. User-Friendly Interface

At the user level, what kind of data visualization charts/graphs, tables, etc., should be provided to visualize the complex findings most often done through these)? Across all solutions, we need fully customizable dashboards to offer perfect vision to different people so they can make decisions and take action based on this data.

05. Automation and Integration Capabilities

- Workflow Automation: Enables recurring surveys or updates to run seamlessly.

- Time Savings: Frees up time in long-term research projects.

- Integrations: Connects with popular CRMs and other applications.

- Simplified Data Addition: This makes incorporating data from external sources easy.

These features make QuestionPro Research Suite a powerful tool for action research. It makes it easy to manage data, conduct analyses, and drive actionable insights through iterative research cycles.

Action research is a dynamic and participatory approach that empowers individuals and communities to address real-world challenges through systematic inquiry and reflection.

The methods used in action research help gather valuable insights and foster continuous improvement, leading to meaningful change across various fields. By promoting iterative cycles, action research generates knowledge and encourages a culture of learning and adaptation, making it a crucial tool for driving transformation.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Research Suite if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

Maximize Employee Feedback with QuestionPro Workforce’s Slack Integration

Nov 6, 2024

2024 Presidential Election Polls: Harris vs. Trump

Nov 5, 2024

Your First Question Should Be Anything But, “Is The Car Okay?” — Tuesday CX Thoughts

QuestionPro vs. Qualtrics: Who Offers the Best 360-Degree Feedback Platform for Your Needs?

Nov 4, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Linking Research to Action: A Simple Guide to Writing an Action Research Report

What Is Action Research, and Why Do We Do It?

Action research is any research into practice undertaken by those involved in that practice, with the primary goal of encouraging continued reflection and making improvement. It can be done in any professional field, including medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, and education. Action research is particularly popular in the field of education. When it comes to teaching, practitioners may be interested in trying out different teaching methods in the classroom, but are unsure of their effectiveness. Action research provides an opportunity to explore the effectiveness of a particular teaching practice, the development of a curriculum, or your students’ learning, hence making continual improvement possible. In other words, the use of an interactive action-and-research process enables practitioners to get an idea of what they and their learners really do inside of the classroom, not merely what they think they can do. By doing this, it is hoped that both the teaching and the learning occurring in the classroom can be better tailored to fit the learners’ needs.

You may be wondering how action research differs from traditional research. The term itself already suggests that it is concerned with both “action” and “research,” as well as the association between the two. Kurt Lewin (1890-1947), a famous psychologist who coined this term, believed that there was “no action without research; no research without action” (Marrow, 1969, p.163). It is certainly possible, and perhaps commonplace, for people to try to have one without the other, but the unique combination of the two is what distinguishes action research from most other forms of enquiry. Traditional research emphasizes the review of prior research, rigorous control of the research design, and generalizable and preferably statistically significant results, all of which help examine the theoretical significance of the issue. Action research, with its emphasis on the insider’s perspective and the practical significance of a current issue, may instead allow less representative sampling, looser procedures, and the presentation of raw data and statistically insignificant results.

What Should We Include in an Action Research Report?

The components put into an action research report largely coincide with the steps used in the action research process. This process usually starts with a question or an observation about a current problem. After identifying the problem area and narrowing it down to make it more manageable for research, the development process continues as you devise an action plan to investigate your question. This will involve gathering data and evidence to support your solution. Common data collection methods include observation of individual or group behavior, taking audio or video recordings, distributing questionnaires or surveys, conducting interviews, asking for peer observations and comments, taking field notes, writing journals, and studying the work samples of your own and your target participants. You may choose to use more than one of these data collection methods. After you have selected your method and are analyzing the data you have collected, you will also reflect upon your entire process of action research. You may have a better solution to your question now, due to the increase of your available evidence. You may also think about the steps you will try next, or decide that the practice needs to be observed again with modifications. If so, the whole action research process starts all over again.

In brief, action research is more like a cyclical process, with the reflection upon your action and research findings affecting changes in your practice, which may lead to extended questions and further action. This brings us back to the essential steps of action research: identifying the problem, devising an action plan, implementing the plan, and finally, observing and reflecting upon the process. Your action research report should comprise all of these essential steps. Feldman and Weiss (n.d.) summarized them as five structural elements, which do not have to be written in a particular order. Your report should:

- Describe the context where the action research takes place. This could be, for example, the school in which you teach. Both features of the school and the population associated with it (e.g., students and parents) would be illustrated as well.

- Contain a statement of your research focus. This would explain where your research questions come from, the problem you intend to investigate, and the goals you want to achieve. You may also mention prior research studies you have read that are related to your action research study.

- Detail the method(s) used. This part includes the procedures you used to collect data, types of data in your report, and justification of your used strategies.

- Highlight the research findings. This is the part in which you observe and reflect upon your practice. By analyzing the evidence you have gathered, you will come to understand whether the initial problem has been solved or not, and what research you have yet to accomplish.

- Suggest implications. You may discuss how the findings of your research will affect your future practice, or explain any new research plans you have that have been inspired by this report’s action research.

The overall structure of your paper will actually look more or less the same as what we commonly see in traditional research papers.

What Else Do We Need to Pay Attention to?

We discussed the major differences between action research and traditional research in the beginning of this article. Due to the difference in the focus of an action research report, the language style used may not be the same as what we normally see or use in a standard research report. Although both kinds of research, both action and traditional, can be published in academic journals, action research may also be published and delivered in brief reports or on websites for a broader, non-academic audience. Instead of using the formal style of scientific research, you may find it more suitable to write in the first person and use a narrative style while documenting your details of the research process.

However, this does not forbid using an academic writing style, which undeniably enhances the credibility of a report. According to Johnson (2002), even though personal thoughts and observations are valued and recorded along the way, an action research report should not be written in a highly subjective manner. A personal, reflective writing style does not necessarily mean that descriptions are unfair or dishonest, but statements with value judgments, highly charged language, and emotional buzzwords are best avoided.

Furthermore, documenting every detail used in the process of research does not necessitate writing a lengthy report. The purpose of giving sufficient details is to let other practitioners trace your train of thought, learn from your examples, and possibly be able to duplicate your steps of research. This is why writing a clear report that does not bore or confuse your readers is essential.

Lastly, You May Ask, Why Do We Bother to Even Write an Action Research Report?

It sounds paradoxical that while practitioners tend to have a great deal of knowledge at their disposal, often they do not communicate their insights to others. Take education as an example: It is both regrettable and regressive if every teacher, no matter how professional he or she might be, only teaches in the way they were taught and fails to understand what their peer teachers know about their practice. Writing an action research report provides you with the chance to reflect upon your own practice, make substantiated claims linking research to action, and document action and ideas as they take place. The results can then be kept, both for the sake of your own future reference, and to also make the most of your insights through the act of sharing with your professional peers.

Feldman, A., & Weiss, T. (n.d.). Suggestions for writing the action research report . Retrieved from http://people.umass.edu/~afeldman/ARreadingmaterials/WritingARReport.html

Johnson, A. P. (2002). A short guide to action research . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Marrow, A. J. (1969). The practical theorist: The life and work of Kurt Lewin . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Tiffany Ip is a lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University. She gained a PhD in neurolinguistics after completing her Bachelor’s degree in psychology and linguistics. She strives to utilize her knowledge to translate brain research findings into practical classroom instruction.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of considerations are necessary to take action in your educational context?

- How do you facilitate an action plan without disrupting your teaching?

- How do you respond when the unplanned happens during data collection?

An action research project is a practical endeavor that will ultimately be shaped by your educational context and practice. Now that you have developed a literature review, you are ready to revise your initial plans and begin to plan your project. This chapter will provide some advice about your considerations when undertaking an action research project in your classroom.

Maintain Focus

Hopefully, you found a lot a research on your topic. If so, you will now have a better understanding of how it fits into your area and field of educational research. Even though the topic and area you are researching may not be small, your study itself should clearly focus on one aspect of the topic in your classroom. It is important to maintain clarity about what you are investigating because a lot will be going on simultaneously during the research process and you do not want to spend precious time on erroneous aspects that are irrelevant to your research.

Even though you may view your practice as research, and vice versa, you might want to consider your research project as a projection or megaphone for your work that will bring attention to the small decisions that make a difference in your educational context. From experience, our concern is that you will find that researching one aspect of your practice will reveal other interconnected aspects that you may find interesting, and you will disorient yourself researching in a confluence of interests, commitments, and purposes. We simply want to emphasize – don’t try to research everything at once. Stay focused on your topic, and focus on exploring it in depth, instead of its many related aspects. Once you feel you have made progress in one aspect, you can then progress to other related areas, as new research projects that continue the research cycle.

Identify a Clear Research Question

Your literature review should have exposed you to an array of research questions related to your topic. More importantly, your review should have helped identify which research questions we have addressed as a field, and which ones still need to be addressed . More than likely your research questions will resemble ones from your literature review, while also being distinguishable based upon your own educational context and the unexplored areas of research on your topic.

Regardless of how your research question took shape, it is important to be clear about what you are researching in your educational context. Action research questions typically begin in ways related to “How does … ?” or “How do I/we … ?”, for example:

Research Question Examples

- How does a semi-structured morning meeting improve my classroom community?

- How does historical fiction help students think about people’s agency in the past?

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences?

- How do we increase student responsibility for their own learning as a team of teachers?

I particularly favor questions with I or we, because they emphasize that you, the actor and researcher, will be clearly taking action to improve your practice. While this may seem rather easy, you need to be aware of asking the right kind of question. One issue is asking a too pointed and closed question that limits the possibility for analysis. These questions tend to rely on quantitative answers, or yes/no answers. For example, “How many students got a 90% or higher on the exam, after reviewing the material three times?

Another issue is asking a question that is too broad, or that considers too many variables. For example, “How does room temperature affect students’ time-on-task?” These are obviously researchable questions, but the aim is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables that has little or no value to your daily practice.

I also want to point out that your research question will potentially change as the research develops. If you consider the question:

As you do an activity, you may find that students are more comfortable and engaged by acting sentences out in small groups, instead of the whole class. Therefore, your question may shift to:

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences, in small groups ?

By simply engaging in the research process and asking questions, you will open your thinking to new possibilities and you will develop new understandings about yourself and the problematic aspects of your educational context.

Understand Your Capabilities and Know that Change Happens Slowly

Similar to your research question, it is important to have a clear and realistic understanding of what is possible to research in your specific educational context. For example, would you be able to address unsatisfactory structures (policies and systems) within your educational context? Probably not immediately, but over time you potentially could. It is much more feasible to think of change happening in smaller increments, from within your own classroom or context, with you as one change agent. For example, you might find it particularly problematic that your school or district places a heavy emphasis on traditional grades, believing that these grades are often not reflective of the skills students have or have not mastered. Instead of attempting to research grading practices across your school or district, your research might instead focus on determining how to provide more meaningful feedback to students and parents about progress in your course. While this project identifies and addresses a structural issue that is part of your school and district context, to keep things manageable, your research project would focus the outcomes on your classroom. The more research you do related to the structure of your educational context the more likely modifications will emerge. The more you understand these modifications in relation to the structural issues you identify within your own context, the more you can influence others by sharing your work and enabling others to understand the modification and address structural issues within their contexts. Throughout your project, you might determine that modifying your grades to be standards-based is more effective than traditional grades, and in turn, that sharing your research outcomes with colleagues at an in-service presentation prompts many to adopt a similar model in their own classrooms. It can be defeating to expect the world to change immediately, but you can provide the spark that ignites coordinated changes. In this way, action research is a powerful methodology for enacting social change. Action research enables individuals to change their own lives, while linking communities of like-minded practitioners who work towards action.

Plan Thoughtfully

Planning thoughtfully involves having a path in mind, but not necessarily having specific objectives. Due to your experience with students and your educational context, the research process will often develop in ways as you expected, but at times it may develop a little differently, which may require you to shift the research focus and change your research question. I will suggest a couple methods to help facilitate this potential shift. First, you may want to develop criteria for gauging the effectiveness of your research process. You may need to refine and modify your criteria and your thinking as you go. For example, we often ask ourselves if action research is encouraging depth of analysis beyond my typical daily pedagogical reflection. You can think about this as you are developing data collection methods and even when you are collecting data. The key distinction is whether the data you will be collecting allows for nuance among the participants or variables. This does not mean that you will have nuance, but it should allow for the possibility. Second, criteria are shaped by our values and develop into standards of judgement. If we identify criteria such as teacher empowerment, then we will use that standard to think about the action contained in our research process. Our values inform our work; therefore, our work should be judged in relation to the relevance of our values in our pedagogy and practice.

Does Your Timeline Work?

While action research is situated in the temporal span that is your life, your research project is short-term, bounded, and related to the socially mediated practices within your educational context. The timeline is important for bounding, or setting limits to your research project, while also making sure you provide the right amount of time for the data to emerge from the process.

For example, if you are thinking about examining the use of math diaries in your classroom, you probably do not want to look at a whole semester of entries because that would be a lot of data, with entries related to a wide range of topics. This would create a huge data analysis endeavor. Therefore, you may want to look at entries from one chapter or unit of study. Also, in terms of timelines, you want to make sure participants have enough time to develop the data you collect. Using the same math example, you would probably want students to have plenty of time to write in the journals, and also space out the entries over the span of the chapter or unit.

In relation to the examples, we think it is an important mind shift to not think of research timelines in terms of deadlines. It is vitally important to provide time and space for the data to emerge from the participants. Therefore, it would be potentially counterproductive to rush a 50-minute data collection into 20 minutes – like all good educators, be flexible in the research process.

Involve Others

It is important to not isolate yourself when doing research. Many educators are already isolated when it comes to practice in their classroom. The research process should be an opportunity to engage with colleagues and open up your classroom to discuss issues that are potentially impacting your entire educational context. Think about the following relationships:

Research participants

You may invite a variety of individuals in your educational context, many with whom you are in a shared situation (e.g. colleagues, administrators). These participants may be part of a collaborative study, they may simply help you develop data collection instruments or intervention items, or they may help to analyze and make sense of the data. While the primary research focus will be you and your learning, you will also appreciate how your learning is potentially influencing the quality of others’ learning.

We always tell educators to be public about your research, or anything exciting that is happening in your educational context, for that matter. In terms of research, you do not want it to seem mysterious to any stakeholder in the educational context. Invite others to visit your setting and observe your research process, and then ask for their formal feedback. Inviting others to your classroom will engage and connect you with other stakeholders, while also showing that your research was established in an ethic of respect for multiple perspectives.

Critical friends or validators

Using critical friends is one way to involve colleagues and also validate your findings and conclusions. While your positionality will shape the research process and subsequently your interpretations of the data, it is important to make sure that others see similar logic in your process and conclusions. Critical friends or validators provide some level of certification that the frameworks you use to develop your research project and make sense of your data are appropriate for your educational context. Your critical friends and validators’ suggestions will be useful if you develop a report or share your findings, but most importantly will provide you confidence moving forward.

Potential researchers

As an educational researcher, you are involved in ongoing improvement plans and district or systemic change. The flexibility of action research allows it to be used in a variety of ways, and your initial research can spark others in your context to engage in research either individually for their own purposes, or collaboratively as a grade level, team, or school. Collaborative inquiry with other educators is an emerging form of professional learning and development for schools with school improvement plans. While they call it collaborative inquiry, these schools are often using an action research model. It is good to think of all of your colleagues as potential research collaborators in the future.

Prioritize Ethical Practice

Try to always be cognizant of your own positionality during the action research process, its relation to your educational context, and any associated power relation to your positionality. Furthermore, you want to make sure that you are not coercing or engaging participants into harmful practices. While this may seem obvious, you may not even realize you are harming your participants because you believe the action is necessary for the research process.

For example, commonly teachers want to try out an intervention that will potentially positively impact their students. When the teacher sets up the action research study, they may have a control group and an experimental group. There is potential to impair the learning of one of these groups if the intervention is either highly impactful or exceedingly worse than the typical instruction. Therefore, teachers can sometimes overlook the potential harm to students in pursuing an experimental method of exploring an intervention.

If you are working with a university researcher, ethical concerns will be covered by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If not, your school or district may have a process or form that you would need to complete, so it would beneficial to check your district policies before starting. Other widely accepted aspects of doing ethically informed research, include:

Confirm Awareness of Study and Negotiate Access – with authorities, participants and parents, guardians, caregivers and supervisors (with IRB this is done with Informed Consent).

- Promise to Uphold Confidentiality – Uphold confidentiality, to your fullest ability, to protect information, identity and data. You can identify people if they indicate they want to be recognized for their contributions.

- Ensure participants’ rights to withdraw from the study at any point .

- Make sure data is secured, either on password protected computer or lock drawer .

Prepare to Problematize your Thinking

Educational researchers who are more philosophically-natured emphasize that research is not about finding solutions, but instead is about creating and asking new and more precise questions. This is represented in the action research process shown in the diagrams in Chapter 1, as Collingwood (1939) notes the aim in human interaction is always to keep the conversation open, while Edward Said (1997) emphasized that there is no end because whatever we consider an end is actually the beginning of something entirely new. These reflections have perspective in evaluating the quality in research and signifying what is “good” in “good pedagogy” and “good research”. If we consider that action research is about studying and reflecting on one’s learning and how that learning influences practice to improve it, there is nothing to stop your line of inquiry as long as you relate it to improving practice. This is why it is necessary to problematize and scrutinize our practices.

Ethical Dilemmas for Educator-Researchers

Classroom teachers are increasingly expected to demonstrate a disposition of reflection and inquiry into their own practice. Many advocate for schools to become research centers, and to produce their own research studies, which is an important advancement in acknowledging and addressing the complexity in today’s schools. When schools conduct their own research studies without outside involvement, they bypass outside controls over their studies. Schools shift power away from the oversight of outside experts and ethical research responsibilities are shifted to those conducting the formal research within their educational context. Ethics firmly grounded and established in school policies and procedures for teaching, becomes multifaceted when teaching practice and research occur simultaneously. When educators conduct research in their classrooms, are they doing so as teachers or as researchers, and if they are researchers, at what point does the teaching role change to research? Although the notion of objectivity is a key element in traditional research paradigms, educator-based research acknowledges a subjective perspective as the educator-researcher is not viewed separately from the research. In action research, unlike traditional research, the educator as researcher gains access to the research site by the nature of the work they are paid and expected to perform. The educator is never detached from the research and remains at the research site both before and after the study. Because studying one’s practice comprises working with other people, ethical deliberations are inevitable. Educator-researchers confront role conflict and ambiguity regarding ethical issues such as informed consent from participants, protecting subjects (students) from harm, and ensuring confidentiality. They must demonstrate a commitment toward fully understanding ethical dilemmas that present themselves within the unique set of circumstances of the educational context. Questions about research ethics can feel exceedingly complex and in specific situations, educator- researchers require guidance from others.

Think about it this way. As a part-time historian and former history teacher I often problematized who we regard as good and bad people in history. I (Clark) grew up minutes from Jesse James’ childhood farm. Jesse James is a well-documented thief, and possibly by today’s standards, a terrorist. He is famous for daylight bank robberies, as well as the sheer number of successful robberies. When Jesse James was assassinated, by a trusted associate none-the-less, his body travelled the country for people to see, while his assailant and assailant’s brother reenacted the assassination over 1,200 times in theaters across the country. Still today in my hometown, they reenact Jesse James’ daylight bank robbery each year at the Fall Festival, immortalizing this thief and terrorist from our past. This demonstrates how some people saw him as somewhat of hero, or champion of some sort of resistance, both historically and in the present. I find this curious and ripe for further inquiry, but primarily it is problematic for how we think about people as good or bad in the past. Whatever we may individually or collectively think about Jesse James as a “good” or “bad” person in history, it is vitally important to problematize our thinking about him. Talking about Jesse James may seem strange, but it is relevant to the field of action research. If we tell people that we are engaging in important and “good” actions, we should be prepared to justify why it is “good” and provide a theoretical, epistemological, or ontological rationale if possible. Experience is never enough, you need to justify why you act in certain ways and not others, and this includes thinking critically about your own thinking.

Educators who view inquiry and research as a facet of their professional identity must think critically about how to design and conduct research in educational settings to address respect, justice, and beneficence to minimize harm to participants. This chapter emphasized the due diligence involved in ethically planning the collection of data, and in considering the challenges faced by educator-researchers in educational contexts.

Planning Action

After the thinking about the considerations above, you are now at the stage of having selected a topic and reflected on different aspects of that topic. You have undertaken a literature review and have done some reading which has enriched your understanding of your topic. As a result of your reading and further thinking, you may have changed or fine-tuned the topic you are exploring. Now it is time for action. In the last section of this chapter, we will address some practical issues of carrying out action research, drawing on both personal experiences of supervising educator-researchers in different settings and from reading and hearing about action research projects carried out by other researchers.

Engaging in an action research can be a rewarding experience, but a beneficial action research project does not happen by accident – it requires careful planning, a flexible approach, and continuous educator-researcher reflection. Although action research does not have to go through a pre-determined set of steps, it is useful here for you to be aware of the progression which we presented in Chapter 2. The sequence of activities we suggested then could be looked on as a checklist for you to consider before planning the practical aspects of your project.

We also want to provide some questions for you to think about as you are about to begin.

- Have you identified a topic for study?

- What is the specific context for the study? (It may be a personal project for you or for a group of researchers of which you are a member.)

- Have you read a sufficient amount of the relevant literature?

- Have you developed your research question(s)?

- Have you assessed the resource needed to complete the research?

As you start your project, it is worth writing down:

- a working title for your project, which you may need to refine later;

- the background of the study , both in terms of your professional context and personal motivation;

- the aims of the project;

- the specific outcomes you are hoping for.

Although most of the models of action research presented in Chapter 1 suggest action taking place in some pre-defined order, they also allow us the possibility of refining our ideas and action in the light of our experiences and reflections. Changes may need to be made in response to your evaluation and your reflections on how the project is progressing. For example, you might have to make adjustments, taking into account the students’ responses, your observations and any observations of your colleagues. All this is very useful and, in fact, it is one of the features that makes action research suitable for educational research.

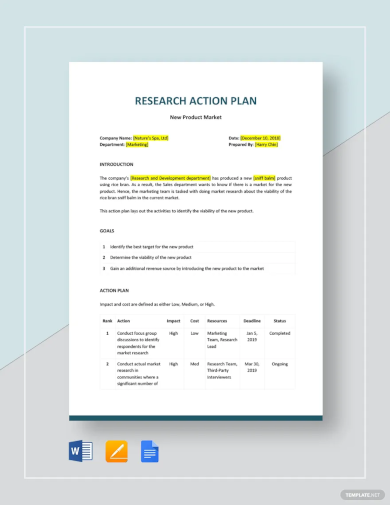

Action research planning sheet

In the past, we have provided action researchers with the following planning list that incorporates all of these considerations. Again, like we have said many times, this is in no way definitive, or lock-in-step procedure you need to follow, but instead guidance based on our perspective to help you engage in the action research process. The left column is the simplified version, and the right column offers more specific advice if need.

Figure 4.1 Planning Sheet for Action Research

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Action research in the classroom: A teacher's guide

November 26, 2021

Discover best practices for action research in the classroom, guiding teachers on implementing and facilitating impactful studies in schools.

Main, P (2021, November 26). Action research in the classroom: A teacher's guide. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/action-research-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide

What is action research?

Action research is a participatory process designed to empower educators to examine and improve their own practice. It is characterized by a cycle of planning , action, observation, and reflection, with the goal of achieving a deeper understanding of practice within educational contexts. This process encourages a wide range of approaches and can be adapted to various social contexts.

At its core, action research involves critical reflection on one's actions as a basis for improvement. Senior leaders and teachers are guided to reflect on their educational strategies , classroom management, and student engagement techniques. It's a collaborative effort that often involves not just the teachers but also the students and other stakeholders, fostering an inclusive process that values the input of all participants.

The action research process is iterative, with each cycle aiming to bring about a clearer understanding and improvement in practice. It typically begins with the identification of real-world problems within the school environment, followed by a circle of planning where strategies are developed to address these issues. The implementation of these strategies is then observed and documented, often through journals or participant observation, allowing for reflection and analysis.

The insights gained from action research contribute to Organization Development, enhancing the quality of teaching and learning. This approach is strongly aligned with the principles of Quality Assurance in Education, ensuring that the actions taken are effective and responsive to the needs of the school community.

Educators can share their findings in community forums or through publications in journals, contributing to the wider theory about practice . Tertiary education sector often draws on such studies to inform teacher training and curriculum development.

In summary, the significant parts of action research include:

- A continuous cycle of planning, action, observation, and reflection.

- A focus on reflective practice to achieve a deeper understanding of educational methodologies.

- A commitment to inclusive and participatory processes that engage the entire school community.

Creating an action research project

The action research process usually begins with a situation or issue that a teacher wants to change as part of school improvement initiatives .

Teachers get support in changing the ' interesting issue ' into a 'researchable question' and then taking to experiment. The teacher will draw on the outcomes of other researchers to help build actions and reveal the consequences .

Participatory action research is a strategy to the enquiry which has been utilised since the 1940s. Participatory action involves researchers and other participants taking informed action to gain knowledge of a problematic situation and change it to bring a positive effect. As an action researcher , a teacher carries out research . Enquiring into their practice would lead a teacher to question the norms and assumptions that are mostly overlooked in normal school life . Making a routine of inquiry can provide a commitment to learning and professional development . A teacher-researcher holds the responsibility for being the source and agent of change.

Examples of action research projects in education include a teacher working with students to improve their reading comprehension skills , a group of teachers collaborating to develop and implement a new curriculum, or a school administrator conducting a study on the effectiveness of a school-wide behavior management program.