Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Steps for Revising Your Paper

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you have plenty of time to revise, use the time to work on your paper and to take breaks from writing. If you can forget about your draft for a day or two, you may return to it with a fresh outlook. During the revising process, put your writing aside at least twice—once during the first part of the process, when you are reorganizing your work, and once during the second part, when you are polishing and paying attention to details.

Use the following questions to evaluate your drafts. You can use your responses to revise your papers by reorganizing them to make your best points stand out, by adding needed information, by eliminating irrelevant information, and by clarifying sections or sentences.

Find your main point.

What are you trying to say in the paper? In other words, try to summarize your thesis, or main point, and the evidence you are using to support that point. Try to imagine that this paper belongs to someone else. Does the paper have a clear thesis? Do you know what the paper is going to be about?

Identify your readers and your purpose.

What are you trying to do in the paper? In other words, are you trying to argue with the reading, to analyze the reading, to evaluate the reading, to apply the reading to another situation, or to accomplish another goal?

Evaluate your evidence.

Does the body of your paper support your thesis? Do you offer enough evidence to support your claim? If you are using quotations from the text as evidence, did you cite them properly?

Save only the good pieces.

Do all of the ideas relate back to the thesis? Is there anything that doesn't seem to fit? If so, you either need to change your thesis to reflect the idea or cut the idea.

Tighten and clean up your language.

Do all of the ideas in the paper make sense? Are there unclear or confusing ideas or sentences? Read your paper out loud and listen for awkward pauses and unclear ideas. Cut out extra words, vagueness, and misused words.

Visit the Purdue OWL's vidcast on cutting during the revision phase for more help with this task.

Eliminate mistakes in grammar and usage.

Do you see any problems with grammar, punctuation, or spelling? If you think something is wrong, you should make a note of it, even if you don't know how to fix it. You can always talk to a Writing Lab tutor about how to correct errors.

Switch from writer-centered to reader-centered.

Try to detach yourself from what you've written; pretend that you are reviewing someone else's work. What would you say is the most successful part of your paper? Why? How could this part be made even better? What would you say is the least successful part of your paper? Why? How could this part be improved?

Revising Drafts

Rewriting is the essence of writing well—where the game is won or lost. —William Zinsser

What this handout is about

This handout will motivate you to revise your drafts and give you strategies to revise effectively.

What does it mean to revise?

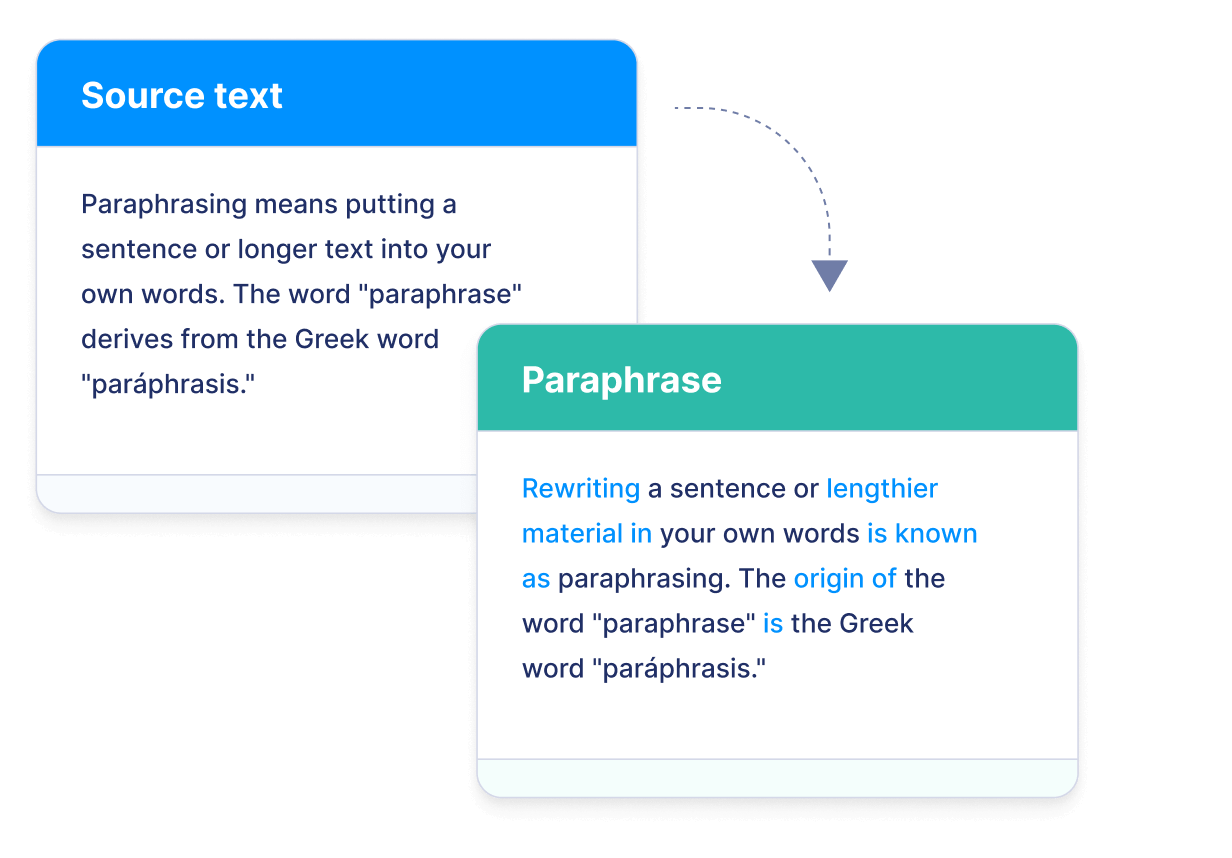

Revision literally means to “see again,” to look at something from a fresh, critical perspective. It is an ongoing process of rethinking the paper: reconsidering your arguments, reviewing your evidence, refining your purpose, reorganizing your presentation, reviving stale prose.

But I thought revision was just fixing the commas and spelling

Nope. That’s called proofreading. It’s an important step before turning your paper in, but if your ideas are predictable, your thesis is weak, and your organization is a mess, then proofreading will just be putting a band-aid on a bullet wound. When you finish revising, that’s the time to proofread. For more information on the subject, see our handout on proofreading .

How about if I just reword things: look for better words, avoid repetition, etc.? Is that revision?

Well, that’s a part of revision called editing. It’s another important final step in polishing your work. But if you haven’t thought through your ideas, then rephrasing them won’t make any difference.

Why is revision important?

Writing is a process of discovery, and you don’t always produce your best stuff when you first get started. So revision is a chance for you to look critically at what you have written to see:

- if it’s really worth saying,

- if it says what you wanted to say, and

- if a reader will understand what you’re saying.

The process

What steps should i use when i begin to revise.

Here are several things to do. But don’t try them all at one time. Instead, focus on two or three main areas during each revision session:

- Wait awhile after you’ve finished a draft before looking at it again. The Roman poet Horace thought one should wait nine years, but that’s a bit much. A day—a few hours even—will work. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself, and don’t be lazy. Ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

- As The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers puts it, “THINK BIG, don’t tinker” (61). At this stage, you should be concerned with the large issues in the paper, not the commas.

- Check the focus of the paper: Is it appropriate to the assignment? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track through the entire paper?

- Think honestly about your thesis: Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point, or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed altogether? For more information visit our handout on thesis statements .

- Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction state clearly what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

What are some other steps I should consider in later stages of the revision process?

- Examine the balance within your paper: Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of detail early on and then let your points get thinner by the end?

- Check that you have kept your promises to your readers: Does your paper follow through on what the thesis promises? Do you support all the claims in your thesis? Are the tone and formality of the language appropriate for your audience?

- Check the organization: Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Do the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper work better if you moved some things around? For more information visit our handout on reorganizing drafts.

- Check your information: Are all your facts accurate? Are any of your statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

- Check your conclusion: Does the last paragraph tie the paper together smoothly and end on a stimulating note, or does the paper just die a slow, redundant, lame, or abrupt death?

Whoa! I thought I could just revise in a few minutes

Sorry. You may want to start working on your next paper early so that you have plenty of time for revising. That way you can give yourself some time to come back to look at what you’ve written with a fresh pair of eyes. It’s amazing how something that sounded brilliant the moment you wrote it can prove to be less-than-brilliant when you give it a chance to incubate.

But I don’t want to rewrite my whole paper!

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

But I work so hard on what I write that I can’t afford to throw any of it away

If you want to be a polished writer, then you will eventually find out that you can’t afford NOT to throw stuff away. As writers, we often produce lots of material that needs to be tossed. The idea or metaphor or paragraph that I think is most wonderful and brilliant is often the very thing that confuses my reader or ruins the tone of my piece or interrupts the flow of my argument.Writers must be willing to sacrifice their favorite bits of writing for the good of the piece as a whole. In order to trim things down, though, you first have to have plenty of material on the page. One trick is not to hinder yourself while you are composing the first draft because the more you produce, the more you will have to work with when cutting time comes.

But sometimes I revise as I go

That’s OK. Since writing is a circular process, you don’t do everything in some specific order. Sometimes you write something and then tinker with it before moving on. But be warned: there are two potential problems with revising as you go. One is that if you revise only as you go along, you never get to think of the big picture. The key is still to give yourself enough time to look at the essay as a whole once you’ve finished. Another danger to revising as you go is that you may short-circuit your creativity. If you spend too much time tinkering with what is on the page, you may lose some of what hasn’t yet made it to the page. Here’s a tip: Don’t proofread as you go. You may waste time correcting the commas in a sentence that may end up being cut anyway.

How do I go about the process of revising? Any tips?

- Work from a printed copy; it’s easier on the eyes. Also, problems that seem invisible on the screen somehow tend to show up better on paper.

- Another tip is to read the paper out loud. That’s one way to see how well things flow.

- Remember all those questions listed above? Don’t try to tackle all of them in one draft. Pick a few “agendas” for each draft so that you won’t go mad trying to see, all at once, if you’ve done everything.

- Ask lots of questions and don’t flinch from answering them truthfully. For example, ask if there are opposing viewpoints that you haven’t considered yet.

Whenever I revise, I just make things worse. I do my best work without revising

That’s a common misconception that sometimes arises from fear, sometimes from laziness. The truth is, though, that except for those rare moments of inspiration or genius when the perfect ideas expressed in the perfect words in the perfect order flow gracefully and effortlessly from the mind, all experienced writers revise their work. I wrote six drafts of this handout. Hemingway rewrote the last page of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times. If you’re still not convinced, re-read some of your old papers. How do they sound now? What would you revise if you had a chance?

What can get in the way of good revision strategies?

Don’t fall in love with what you have written. If you do, you will be hesitant to change it even if you know it’s not great. Start out with a working thesis, and don’t act like you’re married to it. Instead, act like you’re dating it, seeing if you’re compatible, finding out what it’s like from day to day. If a better thesis comes along, let go of the old one. Also, don’t think of revision as just rewording. It is a chance to look at the entire paper, not just isolated words and sentences.

What happens if I find that I no longer agree with my own point?

If you take revision seriously, sometimes the process will lead you to questions you cannot answer, objections or exceptions to your thesis, cases that don’t fit, loose ends or contradictions that just won’t go away. If this happens (and it will if you think long enough), then you have several choices. You could choose to ignore the loose ends and hope your reader doesn’t notice them, but that’s risky. You could change your thesis completely to fit your new understanding of the issue, or you could adjust your thesis slightly to accommodate the new ideas. Or you could simply acknowledge the contradictions and show why your main point still holds up in spite of them. Most readers know there are no easy answers, so they may be annoyed if you give them a thesis and try to claim that it is always true with no exceptions no matter what.

How do I get really good at revising?

The same way you get really good at golf, piano, or a video game—do it often. Take revision seriously, be disciplined, and set high standards for yourself. Here are three more tips:

- The more you produce, the more you can cut.

- The more you can imagine yourself as a reader looking at this for the first time, the easier it will be to spot potential problems.

- The more you demand of yourself in terms of clarity and elegance, the more clear and elegant your writing will be.

How do I revise at the sentence level?

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and follow Peter Elbow’s advice: “Look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious awkwardness’s that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored—where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression; get back to the energy. Listen even for the tiniest jerk or stumble in your reading, the tiniest lessening of your energy or focus or concentration as you say the words . . . A sentence should be alive” (Writing with Power 135).

Practical advice for ensuring that your sentences are alive:

- Use forceful verbs—replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with “She defends the idea.”

- Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

- Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the following sentence, “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn,” would be much better this way, “Huck Finn repeatedly addresses the issue of integrity.”

- Check your sentence variety. If more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern.

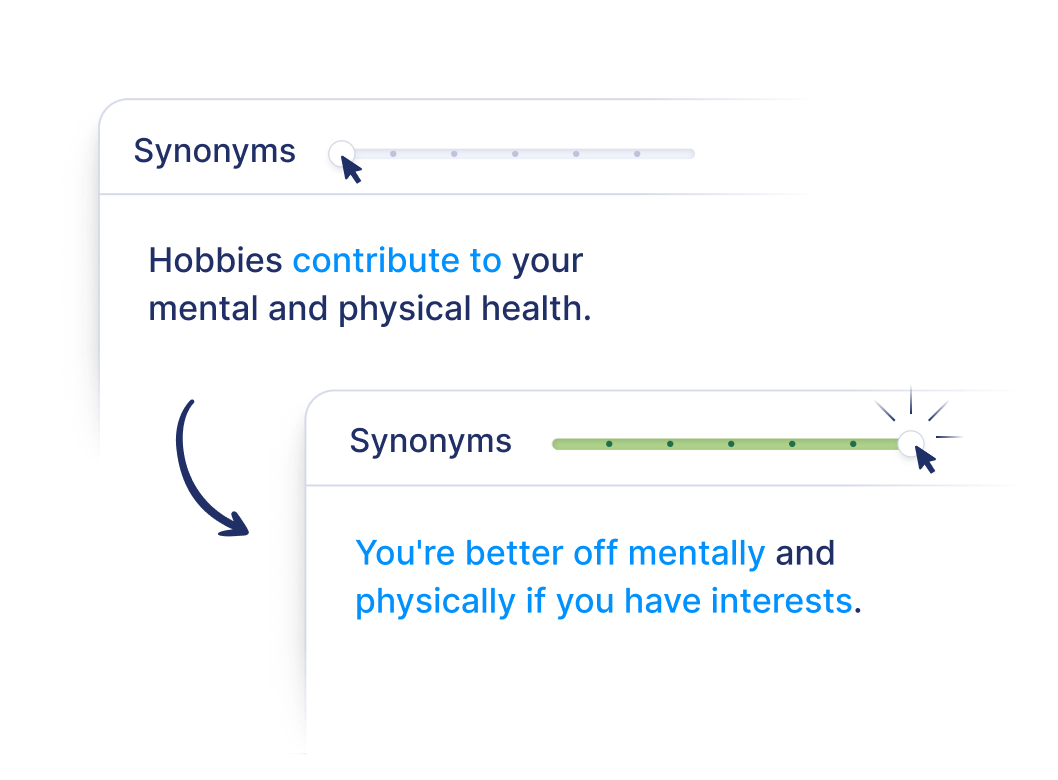

- Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

- Look for sentences that start with “It is” or “There are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

- For more information, please visit our handouts on word choice and style .

How can technology help?

Need some help revising? Take advantage of the revision and versioning features available in modern word processors.

Track your changes. Most word processors and writing tools include a feature that allows you to keep your changes visible until you’re ready to accept them. Using “Track Changes” mode in Word or “Suggesting” mode in Google Docs, for example, allows you to make changes without committing to them.

Compare drafts. Tools that allow you to compare multiple drafts give you the chance to visually track changes over time. Try “File History” or “Compare Documents” modes in Google Doc, Word, and Scrivener to retrieve old drafts, identify changes you’ve made over time, or help you keep a bigger picture in mind as you revise.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Zinsser, William. 2001. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction , 6th ed. New York: Quill.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.4 Revising and Editing

Learning objectives.

- Identify major areas of concern in the draft essay during revising and editing.

- Use peer reviews and editing checklists to assist revising and editing.

- Revise and edit the first draft of your essay and produce a final draft.

Revising and editing are the two tasks you undertake to significantly improve your essay. Both are very important elements of the writing process. You may think that a completed first draft means little improvement is needed. However, even experienced writers need to improve their drafts and rely on peers during revising and editing. You may know that athletes miss catches, fumble balls, or overshoot goals. Dancers forget steps, turn too slowly, or miss beats. For both athletes and dancers, the more they practice, the stronger their performance will become. Web designers seek better images, a more clever design, or a more appealing background for their web pages. Writing has the same capacity to profit from improvement and revision.

Understanding the Purpose of Revising and Editing

Revising and editing allow you to examine two important aspects of your writing separately, so that you can give each task your undivided attention.

- When you revise , you take a second look at your ideas. You might add, cut, move, or change information in order to make your ideas clearer, more accurate, more interesting, or more convincing.

- When you edit , you take a second look at how you expressed your ideas. You add or change words. You fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. You improve your writing style. You make your essay into a polished, mature piece of writing, the end product of your best efforts.

How do you get the best out of your revisions and editing? Here are some strategies that writers have developed to look at their first drafts from a fresh perspective. Try them over the course of this semester; then keep using the ones that bring results.

- Take a break. You are proud of what you wrote, but you might be too close to it to make changes. Set aside your writing for a few hours or even a day until you can look at it objectively.

- Ask someone you trust for feedback and constructive criticism.

- Pretend you are one of your readers. Are you satisfied or dissatisfied? Why?

- Use the resources that your college provides. Find out where your school’s writing lab is located and ask about the assistance they provide online and in person.

Many people hear the words critic , critical , and criticism and pick up only negative vibes that provoke feelings that make them blush, grumble, or shout. However, as a writer and a thinker, you need to learn to be critical of yourself in a positive way and have high expectations for your work. You also need to train your eye and trust your ability to fix what needs fixing. For this, you need to teach yourself where to look.

Creating Unity and Coherence

Following your outline closely offers you a reasonable guarantee that your writing will stay on purpose and not drift away from the controlling idea. However, when writers are rushed, are tired, or cannot find the right words, their writing may become less than they want it to be. Their writing may no longer be clear and concise, and they may be adding information that is not needed to develop the main idea.

When a piece of writing has unity , all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense. When the writing has coherence , the ideas flow smoothly. The wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and from paragraph to paragraph.

Reading your writing aloud will often help you find problems with unity and coherence. Listen for the clarity and flow of your ideas. Identify places where you find yourself confused, and write a note to yourself about possible fixes.

Creating Unity

Sometimes writers get caught up in the moment and cannot resist a good digression. Even though you might enjoy such detours when you chat with friends, unplanned digressions usually harm a piece of writing.

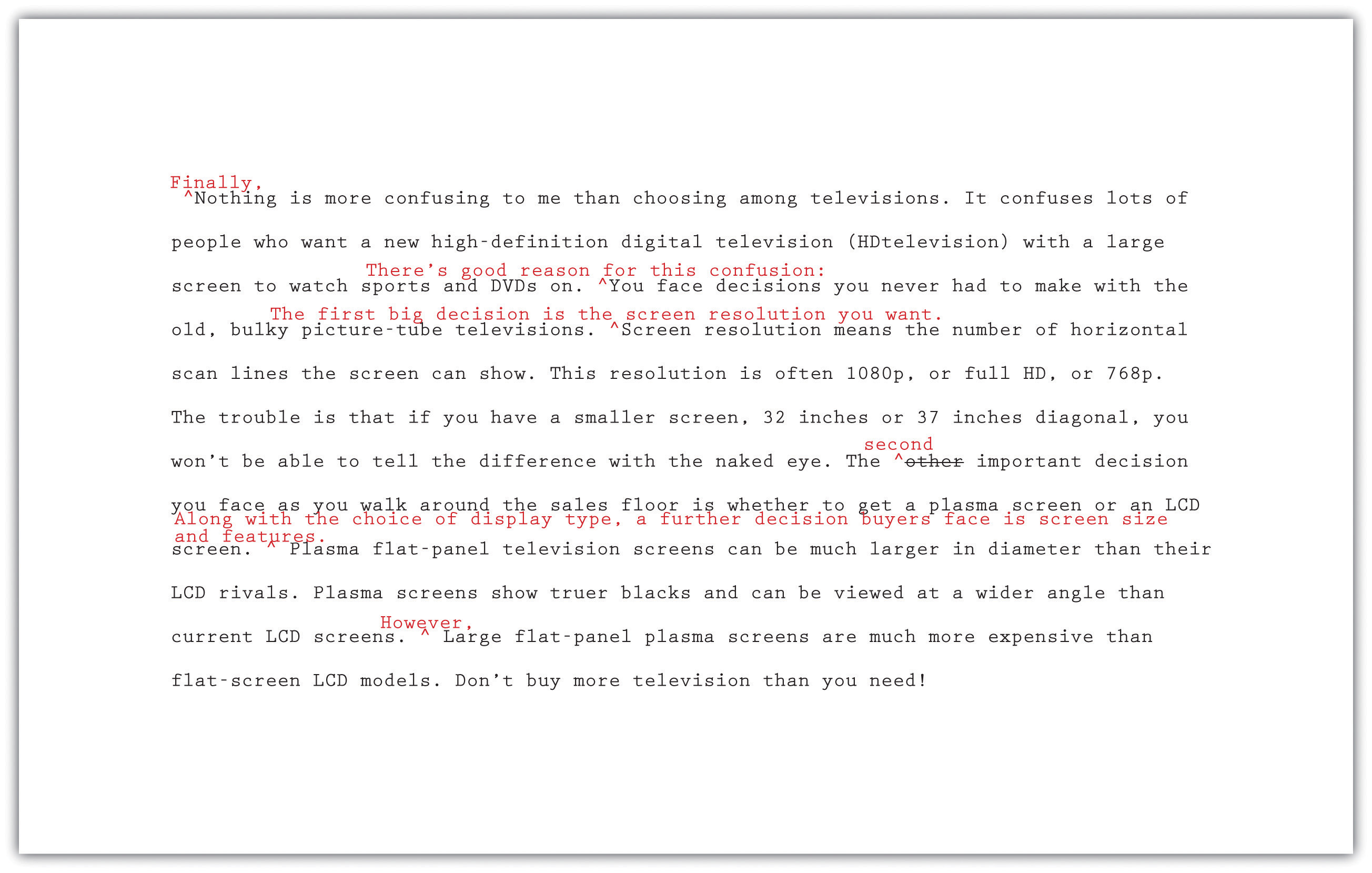

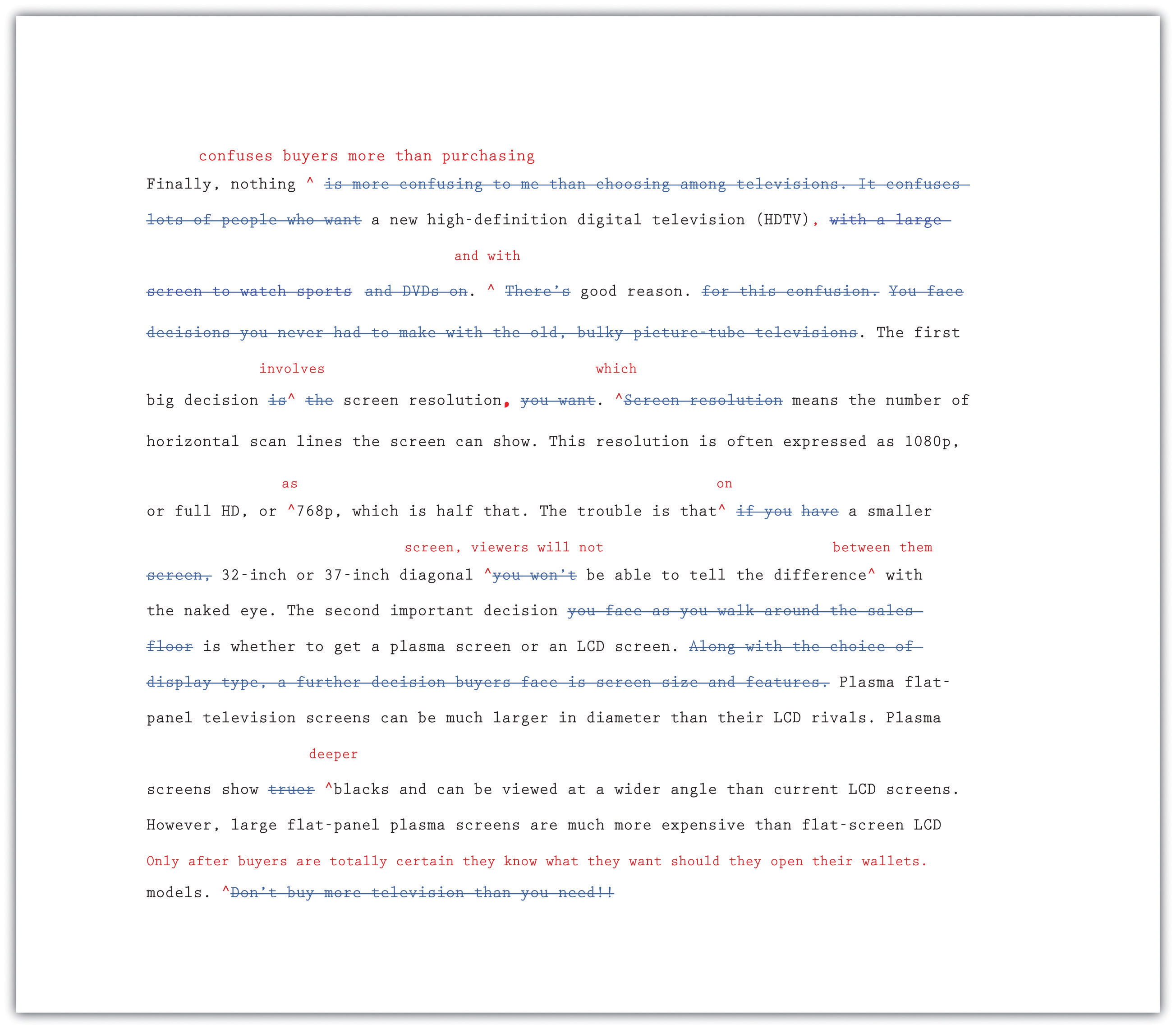

Mariah stayed close to her outline when she drafted the three body paragraphs of her essay she tentatively titled “Digital Technology: The Newest and the Best at What Price?” But a recent shopping trip for an HDTV upset her enough that she digressed from the main topic of her third paragraph and included comments about the sales staff at the electronics store she visited. When she revised her essay, she deleted the off-topic sentences that affected the unity of the paragraph.

Read the following paragraph twice, the first time without Mariah’s changes, and the second time with them.

Nothing is more confusing to me than choosing among televisions. It confuses lots of people who want a new high-definition digital television (HDTV) with a large screen to watch sports and DVDs on. You could listen to the guys in the electronics store, but word has it they know little more than you do. They want to sell what they have in stock, not what best fits your needs. You face decisions you never had to make with the old, bulky picture-tube televisions. Screen resolution means the number of horizontal scan lines the screen can show. This resolution is often 1080p, or full HD, or 768p. The trouble is that if you have a smaller screen, 32 inches or 37 inches diagonal, you won’t be able to tell the difference with the naked eye. The 1080p televisions cost more, though, so those are what the salespeople want you to buy. They get bigger commissions. The other important decision you face as you walk around the sales floor is whether to get a plasma screen or an LCD screen. Now here the salespeople may finally give you decent info. Plasma flat-panel television screens can be much larger in diameter than their LCD rivals. Plasma screens show truer blacks and can be viewed at a wider angle than current LCD screens. But be careful and tell the salesperson you have budget constraints. Large flat-panel plasma screens are much more expensive than flat-screen LCD models. Don’t let someone make you by more television than you need!

Answer the following two questions about Mariah’s paragraph:

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

- Now start to revise the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” . Reread it to find any statements that affect the unity of your writing. Decide how best to revise.

When you reread your writing to find revisions to make, look for each type of problem in a separate sweep. Read it straight through once to locate any problems with unity. Read it straight through a second time to find problems with coherence. You may follow this same practice during many stages of the writing process.

Writing at Work

Many companies hire copyeditors and proofreaders to help them produce the cleanest possible final drafts of large writing projects. Copyeditors are responsible for suggesting revisions and style changes; proofreaders check documents for any errors in capitalization, spelling, and punctuation that have crept in. Many times, these tasks are done on a freelance basis, with one freelancer working for a variety of clients.

Creating Coherence

Careful writers use transitions to clarify how the ideas in their sentences and paragraphs are related. These words and phrases help the writing flow smoothly. Adding transitions is not the only way to improve coherence, but they are often useful and give a mature feel to your essays. Table 8.3 “Common Transitional Words and Phrases” groups many common transitions according to their purpose.

Table 8.3 Common Transitional Words and Phrases

| after | before | later |

| afterward | before long | meanwhile |

| as soon as | finally | next |

| at first | first, second, third | soon |

| at last | in the first place | then |

| above | across | at the bottom |

| at the top | behind | below |

| beside | beyond | inside |

| near | next to | opposite |

| to the left, to the right, to the side | under | where |

| indeed | hence | in conclusion |

| in the final analysis | therefore | thus |

| consequently | furthermore | additionally |

| because | besides the fact | following this idea further |

| in addition | in the same way | moreover |

| looking further | considering…, it is clear that | |

| but | yet | however |

| nevertheless | on the contrary | on the other hand |

| above all | best | especially |

| in fact | more important | most important |

| most | worst | |

| finally | last | in conclusion |

| most of all | least of all | last of all |

| admittedly | at this point | certainly |

| granted | it is true | generally speaking |

| in general | in this situation | no doubt |

| no one denies | obviously | of course |

| to be sure | undoubtedly | unquestionably |

| for instance | for example | |

| first, second, third | generally, furthermore, finally | in the first place, also, last |

| in the first place, furthermore, finally | in the first place, likewise, lastly | |

After Maria revised for unity, she next examined her paragraph about televisions to check for coherence. She looked for places where she needed to add a transition or perhaps reword the text to make the flow of ideas clear. In the version that follows, she has already deleted the sentences that were off topic.

Many writers make their revisions on a printed copy and then transfer them to the version on-screen. They conventionally use a small arrow called a caret (^) to show where to insert an addition or correction.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph.

2. Now return to the first draft of the essay you wrote in Section 8 “Writing Your Own First Draft” and revise it for coherence. Add transition words and phrases where they are needed, and make any other changes that are needed to improve the flow and connection between ideas.

Being Clear and Concise

Some writers are very methodical and painstaking when they write a first draft. Other writers unleash a lot of words in order to get out all that they feel they need to say. Do either of these composing styles match your style? Or is your composing style somewhere in between? No matter which description best fits you, the first draft of almost every piece of writing, no matter its author, can be made clearer and more concise.

If you have a tendency to write too much, you will need to look for unnecessary words. If you have a tendency to be vague or imprecise in your wording, you will need to find specific words to replace any overly general language.

Identifying Wordiness

Sometimes writers use too many words when fewer words will appeal more to their audience and better fit their purpose. Here are some common examples of wordiness to look for in your draft. Eliminating wordiness helps all readers, because it makes your ideas clear, direct, and straightforward.

Sentences that begin with There is or There are .

Wordy: There are two major experiments that the Biology Department sponsors.

Revised: The Biology Department sponsors two major experiments.

Sentences with unnecessary modifiers.

Wordy: Two extremely famous and well-known consumer advocates spoke eloquently in favor of the proposed important legislation.

Revised: Two well-known consumer advocates spoke in favor of the proposed legislation.

Sentences with deadwood phrases that add little to the meaning. Be judicious when you use phrases such as in terms of , with a mind to , on the subject of , as to whether or not , more or less , as far as…is concerned , and similar expressions. You can usually find a more straightforward way to state your point.

Wordy: As a world leader in the field of green technology, the company plans to focus its efforts in the area of geothermal energy.

A report as to whether or not to use geysers as an energy source is in the process of preparation.

Revised: As a world leader in green technology, the company plans to focus on geothermal energy.

A report about using geysers as an energy source is in preparation.

Sentences in the passive voice or with forms of the verb to be . Sentences with passive-voice verbs often create confusion, because the subject of the sentence does not perform an action. Sentences are clearer when the subject of the sentence performs the action and is followed by a strong verb. Use strong active-voice verbs in place of forms of to be , which can lead to wordiness. Avoid passive voice when you can.

Wordy: It might perhaps be said that using a GPS device is something that is a benefit to drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Revised: Using a GPS device benefits drivers who have a poor sense of direction.

Sentences with constructions that can be shortened.

Wordy: The e-book reader, which is a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle bought an e-book reader, and his wife bought an e-book reader, too.

Revised: The e-book reader, a recent invention, may become as commonplace as the cell phone.

My over-sixty uncle and his wife both bought e-book readers.

Now return once more to the first draft of the essay you have been revising. Check it for unnecessary words. Try making your sentences as concise as they can be.

Choosing Specific, Appropriate Words

Most college essays should be written in formal English suitable for an academic situation. Follow these principles to be sure that your word choice is appropriate. For more information about word choice, see Chapter 4 “Working with Words: Which Word Is Right?” .

- Avoid slang. Find alternatives to bummer , kewl , and rad .

- Avoid language that is overly casual. Write about “men and women” rather than “girls and guys” unless you are trying to create a specific effect. A formal tone calls for formal language.

- Avoid contractions. Use do not in place of don’t , I am in place of I’m , have not in place of haven’t , and so on. Contractions are considered casual speech.

- Avoid clichés. Overused expressions such as green with envy , face the music , better late than never , and similar expressions are empty of meaning and may not appeal to your audience.

- Be careful when you use words that sound alike but have different meanings. Some examples are allusion/illusion , complement/compliment , council/counsel , concurrent/consecutive , founder/flounder , and historic/historical . When in doubt, check a dictionary.

- Choose words with the connotations you want. Choosing a word for its connotations is as important in formal essay writing as it is in all kinds of writing. Compare the positive connotations of the word proud and the negative connotations of arrogant and conceited .

- Use specific words rather than overly general words. Find synonyms for thing , people , nice , good , bad , interesting , and other vague words. Or use specific details to make your exact meaning clear.

Now read the revisions Mariah made to make her third paragraph clearer and more concise. She has already incorporated the changes she made to improve unity and coherence.

1. Answer the following questions about Mariah’s revised paragraph:

2. Now return once more to your essay in progress. Read carefully for problems with word choice. Be sure that your draft is written in formal language and that your word choice is specific and appropriate.

Completing a Peer Review

After working so closely with a piece of writing, writers often need to step back and ask for a more objective reader. What writers most need is feedback from readers who can respond only to the words on the page. When they are ready, writers show their drafts to someone they respect and who can give an honest response about its strengths and weaknesses.

You, too, can ask a peer to read your draft when it is ready. After evaluating the feedback and assessing what is most helpful, the reader’s feedback will help you when you revise your draft. This process is called peer review .

You can work with a partner in your class and identify specific ways to strengthen each other’s essays. Although you may be uncomfortable sharing your writing at first, remember that each writer is working toward the same goal: a final draft that fits the audience and the purpose. Maintaining a positive attitude when providing feedback will put you and your partner at ease. The box that follows provides a useful framework for the peer review session.

Questions for Peer Review

Title of essay: ____________________________________________

Date: ____________________________________________

Writer’s name: ____________________________________________

Peer reviewer’s name: _________________________________________

- This essay is about____________________________________________.

- Your main points in this essay are____________________________________________.

- What I most liked about this essay is____________________________________________.

These three points struck me as your strongest:

These places in your essay are not clear to me:

a. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because__________________________________________

b. Where: ____________________________________________

Needs improvement because ____________________________________________

c. Where: ____________________________________________

The one additional change you could make that would improve this essay significantly is ____________________________________________.

One of the reasons why word-processing programs build in a reviewing feature is that workgroups have become a common feature in many businesses. Writing is often collaborative, and the members of a workgroup and their supervisors often critique group members’ work and offer feedback that will lead to a better final product.

Exchange essays with a classmate and complete a peer review of each other’s draft in progress. Remember to give positive feedback and to be courteous and polite in your responses. Focus on providing one positive comment and one question for more information to the author.

Using Feedback Objectively

The purpose of peer feedback is to receive constructive criticism of your essay. Your peer reviewer is your first real audience, and you have the opportunity to learn what confuses and delights a reader so that you can improve your work before sharing the final draft with a wider audience (or your intended audience).

It may not be necessary to incorporate every recommendation your peer reviewer makes. However, if you start to observe a pattern in the responses you receive from peer reviewers, you might want to take that feedback into consideration in future assignments. For example, if you read consistent comments about a need for more research, then you may want to consider including more research in future assignments.

Using Feedback from Multiple Sources

You might get feedback from more than one reader as you share different stages of your revised draft. In this situation, you may receive feedback from readers who do not understand the assignment or who lack your involvement with and enthusiasm for it.

You need to evaluate the responses you receive according to two important criteria:

- Determine if the feedback supports the purpose of the assignment.

- Determine if the suggested revisions are appropriate to the audience.

Then, using these standards, accept or reject revision feedback.

Work with two partners. Go back to Note 8.81 “Exercise 4” in this lesson and compare your responses to Activity A, about Mariah’s paragraph, with your partners’. Recall Mariah’s purpose for writing and her audience. Then, working individually, list where you agree and where you disagree about revision needs.

Editing Your Draft

If you have been incorporating each set of revisions as Mariah has, you have produced multiple drafts of your writing. So far, all your changes have been content changes. Perhaps with the help of peer feedback, you have made sure that you sufficiently supported your ideas. You have checked for problems with unity and coherence. You have examined your essay for word choice, revising to cut unnecessary words and to replace weak wording with specific and appropriate wording.

The next step after revising the content is editing. When you edit, you examine the surface features of your text. You examine your spelling, grammar, usage, and punctuation. You also make sure you use the proper format when creating your finished assignment.

Editing often takes time. Budgeting time into the writing process allows you to complete additional edits after revising. Editing and proofreading your writing helps you create a finished work that represents your best efforts. Here are a few more tips to remember about your readers:

- Readers do not notice correct spelling, but they do notice misspellings.

- Readers look past your sentences to get to your ideas—unless the sentences are awkward, poorly constructed, and frustrating to read.

- Readers notice when every sentence has the same rhythm as every other sentence, with no variety.

- Readers do not cheer when you use there , their , and they’re correctly, but they notice when you do not.

- Readers will notice the care with which you handled your assignment and your attention to detail in the delivery of an error-free document..

The first section of this book offers a useful review of grammar, mechanics, and usage. Use it to help you eliminate major errors in your writing and refine your understanding of the conventions of language. Do not hesitate to ask for help, too, from peer tutors in your academic department or in the college’s writing lab. In the meantime, use the checklist to help you edit your writing.

Editing Your Writing

- Are some sentences actually sentence fragments?

- Are some sentences run-on sentences? How can I correct them?

- Do some sentences need conjunctions between independent clauses?

- Does every verb agree with its subject?

- Is every verb in the correct tense?

- Are tense forms, especially for irregular verbs, written correctly?

- Have I used subject, object, and possessive personal pronouns correctly?

- Have I used who and whom correctly?

- Is the antecedent of every pronoun clear?

- Do all personal pronouns agree with their antecedents?

- Have I used the correct comparative and superlative forms of adjectives and adverbs?

- Is it clear which word a participial phrase modifies, or is it a dangling modifier?

Sentence Structure

- Are all my sentences simple sentences, or do I vary my sentence structure?

- Have I chosen the best coordinating or subordinating conjunctions to join clauses?

- Have I created long, overpacked sentences that should be shortened for clarity?

- Do I see any mistakes in parallel structure?

Punctuation

- Does every sentence end with the correct end punctuation?

- Can I justify the use of every exclamation point?

- Have I used apostrophes correctly to write all singular and plural possessive forms?

- Have I used quotation marks correctly?

Mechanics and Usage

- Can I find any spelling errors? How can I correct them?

- Have I used capital letters where they are needed?

- Have I written abbreviations, where allowed, correctly?

- Can I find any errors in the use of commonly confused words, such as to / too / two ?

Be careful about relying too much on spelling checkers and grammar checkers. A spelling checker cannot recognize that you meant to write principle but wrote principal instead. A grammar checker often queries constructions that are perfectly correct. The program does not understand your meaning; it makes its check against a general set of formulas that might not apply in each instance. If you use a grammar checker, accept the suggestions that make sense, but consider why the suggestions came up.

Proofreading requires patience; it is very easy to read past a mistake. Set your paper aside for at least a few hours, if not a day or more, so your mind will rest. Some professional proofreaders read a text backward so they can concentrate on spelling and punctuation. Another helpful technique is to slowly read a paper aloud, paying attention to every word, letter, and punctuation mark.

If you need additional proofreading help, ask a reliable friend, a classmate, or a peer tutor to make a final pass on your paper to look for anything you missed.

Remember to use proper format when creating your finished assignment. Sometimes an instructor, a department, or a college will require students to follow specific instructions on titles, margins, page numbers, or the location of the writer’s name. These requirements may be more detailed and rigid for research projects and term papers, which often observe the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA) style guides, especially when citations of sources are included.

To ensure the format is correct and follows any specific instructions, make a final check before you submit an assignment.

With the help of the checklist, edit and proofread your essay.

Key Takeaways

- Revising and editing are the stages of the writing process in which you improve your work before producing a final draft.

- During revising, you add, cut, move, or change information in order to improve content.

- During editing, you take a second look at the words and sentences you used to express your ideas and fix any problems in grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure.

- Unity in writing means that all the ideas in each paragraph and in the entire essay clearly belong together and are arranged in an order that makes logical sense.

- Coherence in writing means that the writer’s wording clearly indicates how one idea leads to another within a paragraph and between paragraphs.

- Transitional words and phrases effectively make writing more coherent.

- Writing should be clear and concise, with no unnecessary words.

- Effective formal writing uses specific, appropriate words and avoids slang, contractions, clichés, and overly general words.

- Peer reviews, done properly, can give writers objective feedback about their writing. It is the writer’s responsibility to evaluate the results of peer reviews and incorporate only useful feedback.

- Remember to budget time for careful editing and proofreading. Use all available resources, including editing checklists, peer editing, and your institution’s writing lab, to improve your editing skills.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening, search form, you are here.

- Step 4: Revise

Instructions for Revising

"Few of my novels contain a single sentence that closely resembles the sentence I first set down. I just find that I have to keep zapping and zapping the English language until it starts to behave in some way that vaguely matches my intentions." —Michael Cunningham

Thus when you finish the first draft,

- Let it sit, preferably at least 24 hours, but certainly several hours.

- Print out a clean copy.

- Read it all the way through with no pen in your hand. You will see things you want to change and will get a good look at the “forest” this way without getting caught up in changing individual tress.

- Then write down some notes at the end of the clean copy: what do YOU notice and believe needs to be done to the paper globally?

- Then go read or others’ comments. Do you agree? Of course, if it’s your professor’s comments, you may not have much choice but to make the changes. But if you disagree with your professor’s comments or don’t understand, be sure to ask her about it! If the comments are from a classmate, however, and they suggest a change you disagree with them about, don't make it. (If two of your classmates say the same thing, it would probably be wise to listen to them!)

- If you see a small error such as a misspelled word or an incorrect verb tense, of course, go ahead and change it, but generally focus on global changes for now—i.e., add, rewrite, and delete sentences or paragraphs, reorder the paper, and so on.

- Be sure to SAVE EACH DRAFT WITH A NEW NUMBER, such as "Alien Invation_1," "Alien Invasion_2," and so on, BEFORE you start making changes! You may cut something that you find you want to add back later.

- After you have put in a set of revisions, let the paper sit for another day and then repeat the revision process as many times as possible.

- Only then, when you feel the paper is structurally complete, move on to Step 5, Editing .

An Essay Revision Checklist

Guidelines for Revising a Composition

Maica / Getty Images

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Revision means looking again at what we have written to see how we can improve it. Some of us start revising as soon as we begin a rough draft —restructuring and rearranging sentences as we work out our ideas. Then we return to the draft, perhaps several times, to make further revisions.

Revision as Opportunity

Revising is an opportunity to reconsider our topic, our readers, even our purpose for writing . Taking the time to rethink our approach may encourage us to make major changes in the content and structure of our work.

As a general rule, the best time to revise is not right after you've completed a draft (although at times this is unavoidable). Instead, wait a few hours—even a day or two, if possible—in order to gain some distance from your work. This way you'll be less protective of your writing and better prepared to make changes.

One last bit of advice: read your work aloud when you revise. You may hear problems in your writing that you can't see.

"Never think that what you've written can't be improved. You should always try to make the sentence that much better and make a scene that much clearer. Go over and over the words and reshape them as many times as is needed," (Tracy Chevalier, "Why I Write." The Guardian , 24 Nov. 2006).

Revision Checklist

- Does the essay have a clear and concise main idea? Is this idea made clear to the reader in a thesis statement early in the essay (usually in the introduction )?

- Does the essay have a specific purpose (such as to inform, entertain, evaluate, or persuade)? Have you made this purpose clear to the reader?

- Does the introduction create interest in the topic and make your audience want to read on?

- Is there a clear plan and sense of organization to the essay? Does each paragraph develop logically from the previous one?

- Is each paragraph clearly related to the main idea of the essay? Is there enough information in the essay to support the main idea?

- Is the main point of each paragraph clear? Is each point adequately and clearly defined in a topic sentence and supported with specific details ?

- Are there clear transitions from one paragraph to the next? Have key words and ideas been given proper emphasis in the sentences and paragraphs?

- Are the sentences clear and direct? Can they be understood on the first reading? Are the sentences varied in length and structure? Could any sentences be improved by combining or restructuring them?

- Are the words in the essay clear and precise? Does the essay maintain a consistent tone ?

- Does the essay have an effective conclusion —one that emphasizes the main idea and provides a sense of completeness?

Once you have finished revising your essay, you can turn your attention to the finer details of editing and proofreading your work.

Line Editing Checklist

- Is each sentence clear and complete ?

- Can any short, choppy sentences be improved by combining them?

- Can any long, awkward sentences be improved by breaking them down into shorter units and recombining them?

- Can any wordy sentences be made more concise ?

- Can any run-on sentences be more effectively coordinated or subordinated ?

- Does each verb agree with its subject ?

- Are all verb forms correct and consistent?

- Do pronouns refer clearly to the appropriate nouns ?

- Do all modifying words and phrases refer clearly to the words they are intended to modify?

- Is each word spelled correctly?

- Is the punctuation correct?

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- Revision and Editing Checklist for a Narrative Essay

- revision (composition)

- 11 Quick Tips to Improve Your Writing

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- Conciseness for Better Composition

- Paragraph Writing

- How Do You Edit an Essay?

- Self-Evaluation of Essays

- The Difference Between Revising and Editing

- What Is Expository Writing?

- How To Write an Essay

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

Revision Techniques

Skills: Revision Techniques

Re- vision is about needing to re- see your text, even if you’ve already spent hours conceptualizing and drafting it. Experienced self-editors know that they need to create some distance from their papers and complete proof-read in multiple stages, each time paying attention to just a handful of specific issues.

Get Some Distance

Set your paper aside for a few hours (or even a few days) and read it with fresh eyes. Imagine yourself in your reader’s shoes (whether that be a professor, an employer, or an admissions committee member). Would you understand everything? Did you provide enough explanation? Is the order of ideas clear?

Reverse Outline

A reverse outline is where you summarize each paragraph based on what you actually see there. Ignore what you meant to write; instead, make notes on what you actually wrote.

Some people reverse outline by making bullet points. Other people use notecards or sticky notes so that they can play with the structure afterwards.

Train Your Attention

Our minds benefit from attending to only one or two things at a time. Plan on making several focused passes through your paper where you pay attention to one thing as you read.

For example:

Spend a focused pass paying attention to one thing that you know you need to work on: topic sentences; citing sources; comma splices; verb tense; concision; etc. Read your paper aloud Use ctrl+F (or command +F) to search for repetitive words in your document.

As you can see, the editing process takes time, so block off time to read and re-read your text. Writers improve their writing techniques one thing at a time.

Share your paper with another person.

They can provide the fresh perspective you may need. Our writing center consultants are available for this very purpose! Check our schedule!

Other resources

OWL Purdue: Where to Begin (with Proofreading) : this handout walks a writer through some general strategies for proofreading. Be sure to check the related pages in the sidebar for more strategies about how to locate patterns.

Writers Workshop

Revision is a key element of the writing process, allowing you to re-vision—or re-see—your work from a new perspective and envision how it might work more effectively. As such, revision often focuses on big picture elements such as the organization of your ideas, your argument and supporting evidence, and the clarity of your ideas and analysis. Revision can take place frequently throughout your writing process, as you incorporate feedback from others and review your work on your own. Below, we provide guidance on:

Deciding What to Revise

- Revising Your Argument

- Revising Your Evidence and Source Use

- Revising Your Organization

There are many starting points to begin your revision process, including:

- Previous feedback on your draft from your instructor, your peers, and / or the Writers Workshop

- Class assignment documents such as your prompt, the rubric, and other resources from class, all of which can help you determine what to prioritize in your process

- Reading your work aloud

- Setting your draft aside so that you can return to it later with a fresh perspective

Revising Your Argument

Arguments play a central role in U.S. academic writing and typically reflect the key claim(s) you’re making in your work. In your revision process, then, it’ll often be important to ensure both that you have have a clearly stated argument and that your argument is well-supported by evidence. To do so, you can:

- Identify what your argument is and where it is located

- Ask yourself whether your argument will be clear to your audience as well. (Better yet, get feedback from a friend or Writers Workshop consultant!)

- Review your use of sources and/or evidence. Is your argument convincing? Do you support your argument with strong evidence?

- Address and refute counterarguments

Revising Your Evidence

First, read your paper and highlight every instance where you summarize, quote, or refer to sources. What do you notice overall? Are you using too many sources? Too few sources? Are you analyzing them? Are you connecting them to your argument? Using these observations, determine which of the following you want to focus on in your revisions.

Revising the Amount of Source Material

- Have you used enough sources to support your argument?

- Are there points that could be made clearer or could be better supported by additional sources or additional information from sources?

Revising Summary and Analysis of Sources

- Are you clearly analyzing the source and explaining its connections to your argument?

- Too much summary might indicate you need more examples or analysis

- Too many quotes might indicate you need more analysis

- Not enough examples or quotes might indicate you need more support for your argument

Revising Your Use of Evidence

- Does each example or source have a purpose?

- Do you introduce each source or example?

- Do you explain your evidence’s connection to your argument?

- Are you citing all ideas and language that come from sources?

- Have you included a works cited or reference page providing complete citations for each source you used?

Revising the Kind of Sources You’re Using

- Are you using evidence and examples that your audience will find convincing?

- Are your sources reliable?

- Do you need additional sources or evidence to strengthen support for your argument?

Revising Your Organization

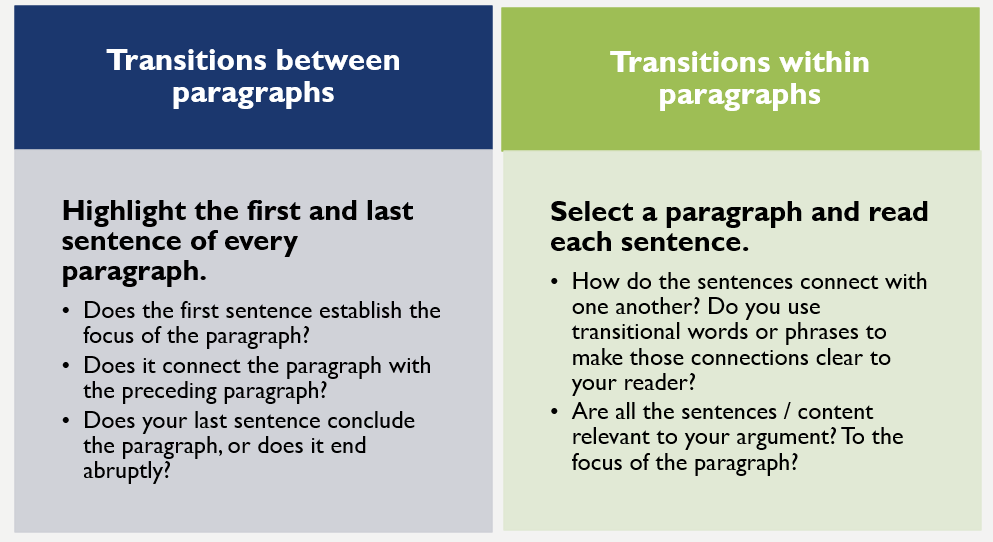

Effective organization relies on both your overall structure of ideas, including the relevance and order of information, as well as how you move between ideas via your transitions between and within paragraphs.

Revising the Overall Structure

- Read each paragraph of your paper. In the margins of your paper, write the focus or theme of each paragraph. Then, write how the paragraph connects with your argument.

- Outline (or reverse outline) your paper, including the main ideas of each paragraph and your supporting points or evidence.

- Do you present your ideas in a logical order based on your argument? Could ideas or paragraphs be rearranged to make your ideas clearer or to more strongly support your argument?

Revising Individual Paragraphs

If you’re having trouble identifying the focus of a paragraph, that suggests you may need to work on the revision of individual paragraphs.

- Try to write a topic sentence that tells your reader what they’re supposed to conclude from this paragraph.

- Reread the individual sentences of the paragraph. Where do you shift focus in the paragraph? What topics are you trying to cover in each sentence? Do they relate to one another? Do they need to be rearranged?

Revising Transitions between Paragraphs

Related Links:

- Asking for Feedback

- Editing and Proofreading

- Make an Appointment

Copyright University of Illinois Board of Trustees Developed by ATLAS | Web Privacy Notice

ThinkWritten

8 Tips for Revising Your Writing in the Revision Process

Revising your writing doesn’t have to be a long painful process. Follow these tips to make your revision process a fun and easy one. One of my favorite Billy Joel songs is “Get It Right the First Time.” It’s a great song, but an impossible goal, even for someone with as much talent as him….

We may receive a commission when you make a purchase from one of our links for products and services we recommend. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for support!

Sharing is caring!

Revising your writing doesn’t have to be a long painful process. Follow these tips to make your revision process a fun and easy one.

One of my favorite Billy Joel songs is “Get It Right the First Time.” It’s a great song, but an impossible goal, even for someone with as much talent as him.

As a writer, you are going to need to understand why they call it a “first” draft – there is an understanding that there will be more than one.

Revising your writing is as important as the actual act of writing. It’s where you polish your piece to make it ready for the rest of the world, even if that only includes one other person.

Here are some tips for how to revise your writing:

1. Wait Until the First Draft is Done

That’s right. Wait. Finish writing your first draft before you dive headlong into the revision process. There are a few reasons for this. First, every moment you spend revising an incomplete manuscript is time that could be better spent working on the actual manuscript.

If you deviate from the process of writing, it can be hard to get back into the flow of creation. Don’t deviate from the plan. Stay on course and wait until you’ve arrived at your destination to start editing.

The second reason echoes the first. If you distract yourself from the goal of finishing your manuscript, there is the danger of falling down the rabbit hole of self-doubt. You could make endless tweaks to a single sentence, and that may call into question the whole paragraph. Maybe the page. Maybe the whole section or chapter. Maybe you should scrap the whole thing and just start over?

There is a creature in your head that whispers vicious things in your own voice and makes you second guess your ability or your ideas. You want to starve that voice of attention, so get the work of a first draft done first. Then you can say you did it! And that voice will have nothing else to say.

2. The Rule of Two

After you have finished your first draft (and maybe let it rest for a bit – like a fine steak), you need to read through it at least twice.

First, the technical run – spelling and grammar. Fix all those your/you’re/yore and there/their/they’re flops and make sure you haven’t left any incomplete sentences, run-ons, or adverbs (we’ll get to these in a minute). Ensure voice consistency (active, please), and maintain perspective (first person, second person, third person omniscient/limited).

Second, make substantive corrections. Edit out inconsistencies and anything that messes with the overall flow of the work.

See Related Article: What’s the Difference Between Editing vs. Revising?

As you make your runs through the text, keep these other pointers in mind:

3. Take Notes

While reading through the first time (and, for longer works, as you are writing) make notes SEPARATE from the actual text.

I keep a Rhodia Squared dot pad handy for just about everything – sketching out ideas in visual form, writing notes about characters and places (especially how to SPELL their names), and sometimes the alternate ideas that voice I mentioned before comes up with (we may not always agree, but sometimes it has a good idea or two).

Take note as you run your first technical revisions about anything you want to revisit during the second part of your revision process. That will make it easier to come back to, and, let’s be fair, the biggest lie we tell ourselves is “I don’t need to write that down. I’ll remember it later.”

4. Don’t Trust Technology Too Much

Spelling and Grammar checks have come a long way since the first time I installed Microsoft Word back in the mid 90’s. Unfortunately, not far enough. As I write this, Word has highlighted at least a half-dozen grammatical non-errors.

As you build your skills as a writer, put a few tools in your toolbox to help you better understand how language works. English is a fickle mistress, and I will evangelize the Elements of Style until my dying breath. It’s a quick read with loads of great information to help you be a better writer and communicator in general. Get a copy (it’s cheap) and keep it handy. Refer to it for any questions on grammar you might have.

5. Adverbs are the Devil

Lazy writers use adverbs. Period. If you are doing your job well enough, describing the scene and the characters, the reader will understand how an action is performed well enough without any of those -ly words hanging about. Think about these examples below – what sounds better?

“I’ll get you for this!” he said angrily.

He shook his fist, knuckles white with rage, and shouted “I’ll get you for this!”

Same idea, but I think we can agree the second version transmits it with better clarity. Do your best to avoid adverbs. You won’t be perfect – none of us are – but do your best.

6. Kill Your Darlings

This is the hardest part of revising your writing. Sure, it’s easy to know when your writing is bad, and little is more satisfying than culling the weak from your word-herd. But what about those times when you read your own writing and fall in love…and then suddenly realize that this spectacular bit of prose doesn’t actually belong with the rest of the work. Maybe you could make it fit, or tweak somewhere else to force it to work.

It’s a difficult decision, but in the end the best and simplest way to deal with this scenario is to swipe the red pen and take it out. Aside from the mechanical process of fixing your spelling mistakes and revising for voice, your primary concern during the revision process is to remove everything that isn’t the story.

That means sometimes you have to kill your darlings – those bits of work that really sing, but brought the wrong sheet music to choir practice. If you feel terrible about it, cut and paste into a separate document to look at it later.

7. Know When to Stop Revising

Remember when we talked about that voice? It can show up during the regular revision process, too. When you get to the end of your second run through the text, you are going to be tempted to go through again. And again. And again.

If your immediate feeling about concluding the revision process is contentment, then stop. Tell yourself that it is good enough. Fix yourself a coffee or a cocktail or whatever you do to celebrate and enjoy the moment. Kick your feet up and relax. You have earned it, my friend!

8. Open the Door

The last and most stressful part of the whole process is to let someone else have a crack at it. This should be your Designated Reader – a person who knows you; someone you can trust to give honest feedback about your work.

It doesn’t hurt if they have an interest in your genre (and some technical know-how of the craft), but that isn’t totally necessary. If you can watch them read it, don’t. It’s as private a matter for someone to read your work as it was for you to write it.

Give them space and time, and be prepared for feedback of all kinds. If you hit a home run, then great! You’re ready for the next step. If your Designated Reader has some valuable critique, make targeted changes. Remember to know when enough is enough.

Do you have any tips to share about how to revise your first draft? Share your tips for revising your writing in the comments below!

Bill comes from a mishmash of writing experiences, having covered topics ranging from defining thematic periodicity of heroic medieval literature to technical manuals on troubleshooting mobile smart device operating systems. He holds graduate degrees in literature and business administration, is an avid fan of table-top and post-to-play online role playing games, serves as a mentor on the D&D DMs Only Facebook group, and dabbles in writing fantasy fiction and passable poetry when he isn’t busy either with work or being a husband and father.

Similar Posts

Tools & Resources for Writers and Authors

How to Write a Short Story

How to Use Evernote to Plan a Novel

How to Write a Novel: Writing a Book in 4 Steps

The Hero’s Journey: A 17 Step Story Structure Beat Sheet

How to Avoid Over Planning Your Novel

- Twin Cities

- Campus Today

- Directories

University of Minnesota Crookston

- Mission, Vision & Values

- Campus Directory

- Campus Maps/Directions

- Transportation and Lodging

- Crookston Community

- Chancellor's Office

- Quick Facts

- Tuition & Costs

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Organizational Chart

- Accreditation

- Strategic Planning

- Awards and Recognition

- Policies & Procedures

- Campus Reporting

- Public Safety

- Admissions Home

- First Year Student

- Transfer Student

- Online Student

- International Student

- Military Veteran Student

- PSEO Student

- More Student Types...

- Financial Aid

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Request Info

- Visit Campus

- Admitted Students

- Majors, Minors & Programs

- Agriculture and Natural Resources

- Humanities, Social Sciences, and Education

- Math, Science and Technology

- Teacher Education Unit

- Class Schedules & Registration

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Organizations

- Events Calendar

- Student Activities

- Outdoor Equipment Rental

- Intramural & Club Sports

- Wellness Center

- Golden Eagle Athletics

- Health Services

- Career Services

- Counseling Services

- Success Center/Tutoring

- Computer Help Desk

- Scholarships & Aid

- Eagle's Essentials Pantry

- Transportation

- Dining Options

- Residential Life

- Safety & Security

- Crookston & NW Minnesota

- Important Dates & Deadlines

- Cross Country

- Equestrian - Jumping Seat

- Equestrian - Western

- Teambackers

- Campus News

- Student Dates & Deadlines

- Social Media

- Publications & Archives

- Summer Camps

- Alumni/Donor Awards

- Alumni and Donor Relations

Writing Center

How to revise drafts, now the real work begins....

After writing the first draft of an essay, you may think much of your work is done, but actually the real work – revising – is just beginning. The good news is that by this point in the writing process you have gained some perspective and can ask yourself some questions: Did I develop my subject matter appropriately? Did my thesis change or evolve during writing? Did I communicate my ideas effectively and clearly? Would I like to revise, but feel uncertain about how to do it?

Also see the UMN Crookston Writing Center's Revising and Editing Handout .

How to Revise

First, put your draft aside for a little while. Time away from your essay will allow for more objective self-evaluation. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself; ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

Check the focus of the paper. Is it appropriate to the assignment prompt? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track throughout the entire paper? (At this stage, you should be concerned with the large, content-related issues in the paper, not the grammar and sentence structure).

Get feedback . Since you already know what you’re trying to say, you aren’t always the best judge of where your draft is clear or unclear. Let another reader tell you. Then discuss aloud what you were trying to achieve. In articulating for someone else what you meant to argue, you will clarify ideas for yourself.

Think honestly about your thesis. Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point? Or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed completely?

Examine the balance within your paper. Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of details early on and then let your points get thinner by the end? Based on what you did in the previous step, restructure your argument: reorder your points and cut anything that’s irrelevant or redundant. You may want to return to your sources for additional supporting evidence.

Now that you know what you’re really arguing, work on your introduction and conclusion . Make sure to begin your paragraphs with topic sentences, linking the idea(s) in each paragraph to those proposed in the thesis.

Proofread. Aim for precision and economy in language. Read aloud so you can hear imperfections. (Your ear may pick up what your eye has missed). Note that this step comes LAST. There’s no point in making a sentence grammatically perfect if it’s going to be changed or deleted anyway.

As you revise your own work, keep the following in mind:

Revision means rethinking your thesis. It is unreasonable to expect to come up with the best thesis possible – one that accounts for all aspects of your topic – before beginning a draft, or even during a first draft. The best theses evolve; they are actually produced during the writing process. Successful revision involves bringing your thesis into focus—or changing it altogether.

Revision means making structural changes. Drafting is usually a process of discovering an idea or argument. Your argument will not become clearer if you only tinker with individual sentences. Successful revision involves bringing the strongest ideas to the front of the essay, reordering the main points, and cutting irrelevant sections. It also involves making the argument’s structure visible by strengthening topic sentences and transitions.

Revision takes time. Avoid shortcuts: the reward for sustained effort is an essay that is clearer, more persuasive, and more sophisticated.

Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction clearly state what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

Check the organization. Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Doe the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper be work better if you moved some things around?

Check your information. Are all your facts accurate? Are any of our statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

Revising Sentences

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious places that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored – where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression: get back to the energy.

Tips for writing good sentences:

Use forceful verbs – replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with ‘she defends the idea.” Also, try to stay in the active voice.

Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the sentence “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn ” would be much better this way: “ Huck Finn repeated addresses the issue of integrity.”

Check your sentence variety. IF more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern. Also, try to mix simple sentences with compound and compound-complex sentences for variety.

Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

Look for sentences that start with “it is” or “there are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

By Jocelyn Rolling, English Instructor Last edited October 2016 by Allison Haas, M.A.

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Revision -- the process of revisiting, rethinking, and refining written work to improve its content , clarity and overall effectiveness -- is such an important part of the writing process that experienced writers often say "writing is revision." This article reviews research and theory on what revision is and why it's so important to writers. Case studies , writing protocols, and interviews of writers at work have found that revision is guided by inchoate, preverbal feelings and intuition--what Sondra Perl calls " felt sense "; by reasoning and openness to strategic searching , counterarguments , audience awareness , and critique ; and by knowledge of discourse conventions , such as mastery of standard written English , genre , citation , and the stylistic expectations of academic writing or professional writing . Understanding revision processes can help you become a more skilled and confident writer--and thinker.

Synonyms – Related Terms

In workplace and school settings , people use a variety of terms to describe revision or the act of revising , including

- a high-level review

- a global review

- a substantive rewrite

- a major rewrite

- Slashing and Throwing Out

On occasion, students or inexperienced writers may conflate revision with editing and proofreading . However, subject matter experts in writing studies do not use these terms interchangeably. Rather, they distinguish these intellectual strategies by noting their different foci:

a focus on the global perspective :

- audience awareness

- purpose & organization (e.g., What’s my thesis ?)

- invention , especially content development

- Content Development