Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

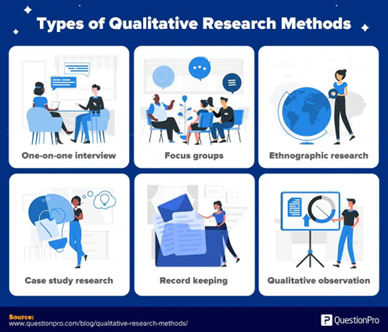

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Venturing into Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide to Getting Started

Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research Journal

- Journal Home

- Submissions

In this commentary, we offer an introduction to qualitative research. Our goal is to provide guidance so that others can avoid common missteps and benefit from our lessons learned. We explain what qualitative data and research are, the value of qualitative research, and features that make qualitative research excellent, as well as how qualitative data can be collected and used to study undergraduate research. Our advice and recommendations are targeted at researchers who, like us, were first trained in fields with tendencies to overlook or underestimate qualitative research and its contributions. We share examples from our own and others’ research related to undergraduate research settings. We provide a table of resources researchers may find useful as they continue to learn about and conduct qualitative studies.

Introduction

We both started our scholarly journeys as biologists. As we trained, we both grew interested in researching undergraduate education and we transitioned to doing education research. We quickly came to realize that our training in experimental approaches and quantitative methods was woefully insufficient to study the diversity of ways students think, believe, value, feel, behave, and change in a variety of learning environments and educational systems.

For instance, there are established ways to quantify some educational variables, but not others. In addition, there may be phenomena at play that we haven’t thought of or that might be counterintuitive, which could lead us to quantify things that end up being irrelevant or meaningless. Herein lies the power of qualitative research. Qualitative research generates new knowledge by enabling rich, multifaceted descriptions of phenomena of interest, known as constructs (i.e., latent, unobservable variables), and producing possible explanations of how phenomena are occurring (i.e., mechanisms or relationships between constructs in different contexts and situations with different individuals and groups).

In this essay, we aim to offer an approachable explanation of qualitative research, including the types of questions that qualitative research is suited to address, the characteristics of robust qualitative research, and guidance on how to get started. We use examples from our own and others’ research to illustrate our explanations, and we cite references where readers can learn more. We expect Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research (SPUR) readers from disciplines with a tradition of qualitative research might question why we would write this piece and what makes us qualified to do so. There are many scholars with much more qualitative research expertise than we have. Yet, we think we can offer a unique perspective to SPUR readers who are new to qualitative research or coming from disciplines where qualitative research is unfamiliar or undervalued. We have both designed, conducted, and published qualitative research in the context of undergraduate education and research experiences. We draw upon this experience in the recommendations we offer here.

Doing qualitative research involves acknowledging your “positionality,” or how your own background, lived experiences, and philosophical understandings of research influence how you approach and interpret the work (e.g., Hampton, Reeping, and Ozkan 2021; Holmes and Darwin 2020). Our positionalities have influenced our approach to this article and qualitative research generally. I (MAP) first learned about qualitative research from my undergraduate academic adviser. She invited me to help her implement and evaluate a capstone course in which groups of microbiology undergraduates engaged in a semester-long research project to address problems faced by community organizations (Watson, Willford, and Pfeifer 2018). At the time, I wasn’t aware of the long-standing history of qualitative research or its different forms and approaches. I just knew that reading quote data helped me understand human experiences in a way that survey numbers did not. Since my introduction to qualitative research, I’ve been fortunate to receive formal training. I consider my most valuable lessons about qualitative research to be through the practical experience of doing qualitative research and being mentored by qualitative researchers.

When I (ELD) first learned about qualitative research, I thought it meant words – perhaps collected through surveys, focus groups, interviews, or class recordings. I thought qualitative research would be easy – it was just words after all, and I had been using words almost my whole life. I assumed if I collected some words and summarized what I thought they meant (think word cloud), I would be doing qualitative research. As we will elaborate here, this is a limited view of what qualitative research is and what qualitative research can accomplish. When I began presenting qualitative research, I found it helpful to draw analogies to qualitative studies in natural science and medical disciplines. For instance, in the field of biology, the invention of technologies (e.g., lenses, microscopes) allowed for detailed observation and rich descriptions of cells (i.e., qualitative research) that led to the development of cell theory, the establishment of the field of cell biology, and quantitative research on cell structure, function, and dysfunction. In my own field of neuroscience, Henry Moliason, known as HM, was the focus of qualitative case study because he lost the ability to form new long-term memories due to a surgical treatment for severe epilepsy. Rich (i.e., comprehensive and detailed) description of Mr. Moliason’s memory impairment was the basis for hippocampal function being proposed as the main mechanism through which memories are formed. These examples of “non-numbery” research that produce influential descriptions and testable mechanisms helped me recognize the potential value and impact of qualitative research.

Types of Qualitative Research Questions

Qualitative research is useful for addressing two main types of questions: descriptive and mechanistic. Descriptive questions ask what is happening, for whom, and in what circumstances. Mechanistic questions ask how a phenomenon of interest happening. Here we explain each type of question and highlight some example studies conducted in the context of undergraduate research.

Descriptive Questions

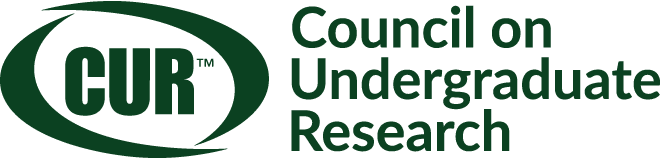

Descriptive research seeks to elucidate details that enhance our overall understanding of a particular phenomenon—it answers questions about what a phenomenon is, including its defining features (i.e., dimensions) and what makes it distinct from other phenomena (Loeb et al. 2017). Descriptive research can also reveal who experiences the phenomenon, as well as when and where a phenomenon occurs (Loeb et al. 2017). Details like these serve as a starting point for future research, policy development, and enhanced practice. For instance, Hunter, Laursen, and Seymour (2007) carried out a qualitative study that identified and described the benefits of undergraduate research from the perspectives of both students and faculty. This work prompted calls for expansion of undergraduate research nationally and led to numerous quantitative studies (Gentile, Brenner, and Stephens 2017). Among these were quantitative studies from our group on the influences of research mentors on undergraduate researchers (Aikens et al. 2016, 2017; Joshi, Aikens, and Dolan 2019). Although these studies were framed to identify beneficial outcomes, we observed that undergraduates who had less favorable experiences with mentors were opting not to participate in our studies. Given this observation and the dearth of research on negative experiences in undergraduate research, we carried out a descriptive qualitative study of the dimensions (i.e., the what) of negative mentoring—that is, problematic or ineffective mentoring—in undergraduate life science research (Limeri et al. 2019). This study revealed that negative mentoring in undergraduate research included the absence of support from mentors and actively harmful mentor behaviors. These results served as the basis for practical guidance on how to curtail negative mentoring and its effects and for ongoing quantitative research. We use this study as the basis for the extended examples highlighted in Table 1.

Descriptive research is also suited to investigating the experiences of groups that are marginalized or minoritized in higher education. These studies offer insights into student experiences that may be otherwise overlooked or masked in larger quantitative studies (Vaccaro et al. 2015). For example, descriptive qualitative research shed light on how Black women in undergraduate and graduate STEM programs recognized and responded to structural racism, sexism, and race-gender bias. This research identified how high-achieving Black STEM students experienced racial battle fatigue and offered program-level suggestions for how to better support Black students (McGee and Bentley 2017). Descriptive qualitative research of deaf students involved in undergraduate research revealed that lack of awareness of Deaf culture of research mentors as well as lack of communication hindered students’ research experiences (Majocha et al. 2018). This research led to recommendations for research programs, research mentors, and students themselves. Another descriptive qualitative study showed how Latine students’ science identity changed over time when involved in an undergraduate research program (Vasquez-Salgado et al. 2023). Specifically, Vasguez-Salgado and colleagues identified patterns in students’ science identity through three waves of data collection spanning 18 months. Students’ identities showed consistent or fast achievement of feeling like a scientist, gradual achievement of feeling like a scientist, achievement adjustment of feeling like a scientist at one point and less so later in the program, or never feeling like a scientist. Together, these and other studies have generated knowledge that raises questions for future research and informs our collective efforts to make undergraduate research more accessible and inclusive.

Mechanistic Questions

Mechanistic qualitative research aims to address questions of how or why a phenomenon occurs. In the context of undergraduate research, an investigator may seek to understand how or why a particular practice or program design affects students. Recently, we conducted a mechanistic qualitative study that aimed, in part, to understand how early career researchers (undergraduate, postbaccalaureate, and graduate students) conceptualized their science identity (Pfeifer et al. 2023). Previous research theorized that someone is more likely to identify as a scientist if they are interested in science, believe they are competent in and can perform science, and feel recognized by others for their scientific aptitude or accomplishments (Carlone and Johnson 2007; Hazari et al. 2010; Potvin and Hazari 2013). However, this theory is somewhat limited in that it does not fully explain how context affects science identity or how science identity evolves, especially as researchers advance in their scientific training (Hazari et al. 2020; Kim and Sinatra 2018). To address this, we integrated science identity theory with research on professional identity development to design our study (Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann 2006). We analyzed data from two national samples, including open-ended survey responses from 548 undergraduates engaged in research training and interview data from 30 early career researchers in the natural sciences. We found that they conceptualized science identity as a continuum that encompassed being a science student, being a science researcher, and being a career researcher. How students saw their science identity depended on how they viewed the purpose of their daily research, the level of intellectual responsibility they have for their research, and the extent of their autonomy in their research. We consider these findings to be hypotheses that can be tested quantitatively to better understand science identity dynamics in research training contexts. By asking this mechanistic question about science identity, we sought to add to and refine existing theory.

Key Attributes of Qualitative Research

For any type of research to be meaningful, it must possess some degree of rigor—what qualitative researchers call trustworthiness (Morse et al. 2002; Yilmaz 2013). Qualitative research is more trustworthy if it is characterized by credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Creswell and Poth 2016; Lincoln and Guba 1985). For instance, like accuracy and precision in quantitative research, do qualitative findings reflect what is being studied and are the interpretations true to the data (credibility)? Similar to reproducibility in quantitative research, how can qualitative research findings be applied to similar contexts (transferability)? Like validity in quantitative research, to what degree are the framing, methods, and findings of qualitative research appropriate given the aims (dependability)? Similar to the idea of replicability in quantitative research, if the same analytic tools were applied to the same data set could similar findings be reached by someone outside the original research team (confirmability)? The exact dimensions of trustworthiness, how trustworthiness manifests in the research process, the best ways to achieve trustworthiness, and how to talk about trustworthiness in research products are the subject of ongoing and often-spirited debate (e.g., Gioia et al. 2022; Mays and Pope 2020; Morse et al. 2002; Ritchie et al. 2013; Tracy 2010; Welch 2018; Yadav 2022). Central to these dialogues is the fact that qualitative research is composed of different philosophical approaches that emerged and evolved from diverse social science fields (Creswell and Poth 2016; Ritchie et al. 2013). Identifying universally agreed-upon criteria and the means to achieve these criteria is complex.

In our own work, we have found Tracy’s (2010) eight criteria for excellent qualitative research particularly useful. These criteria have helped us design studies, make decisions during the course of research, and articulate in our papers how our research seeks to achieve trustworthiness (e.g., Pfeifer, Cordero, and Stanton 2023). The full list of criteria is: worthy topic, rich rigor, sincerity, credibility, resonance, significant contribution, ethical conduct, and meaningful coherence (Tracy 2010). These criteria borrow from and build on the presented concepts of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. In our view, these criteria are presented and described in a way that makes sense to us and fits our approach to research. Here we highlight two criteria that may be particularly relevant if you are new to qualitative research.

Worthy Topics

As scholars familiar with undergraduate research and scholarly inquiry, SPUR readers are well-positioned to design studies that address research questions that are significant and timely in the context of undergraduate research. The first step in doing qualitative research (or any research) is to figure out what you want to study. You’ll want to select a topic that you find interesting, relevant, or otherwise compelling so you are motivated to spend time and effort investigating it. One way to find a topic is to notice what is happening in your environment and your work. What are you observing about undergraduate research? Something about students who participate (or not)? Something about colleagues who work with undergraduate researchers (or not)? Something about the design, implementation, or outcomes of the research experience? Something about the programmatic or institutional context? For a topic to be worthy of research, it should be interesting to you and to others. Consider sharing your observations with a few critical friends (i.e., trusted colleagues who will give you honest feedback) about whether they find your observations interesting or worth your time and energy to explore.

Like other human research, qualitative studies must adhere to basic ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects 1978). Respect for persons means treating all people as autonomous and protecting individuals with diminished autonomy (e.g., students whom we teach and assess). Beneficence involves treating people in an ethical manner, including respecting their decisions, protecting them from harm, and securing their well-being. Justice refers to the balance between benefiting from research and bearing its burdens; in other words, people should be able to benefit from research and should not be expected to bear the burden of research if they cannot benefit. Although it is beyond the scope of this essay to provide guidance on how to adhere to these principles, it is important to recognize that qualitative methods like interviewing can be highly personal and sometimes powerful experiences for both participants (and researchers). Investigators should carefully consider how their participants may be affected by data collection. For example, you may interview or survey participants about a personally difficult or painful experience. Do you then bear responsibility for helping them find support to navigate these difficulties? What if a participant reveals to you a serious mental health issue or physical safety concern? These situations occurred during our negative mentoring studies. We provided information to participants about where they could seek counseling or support for specific issues that can occur with mentors, such as harassment and discrimination.

Certainly not all qualitative data collection brings up these issues, but it can and does happen more frequently than you might expect. Your institutional review board (IRB), collaborators, and critical friends can be helpful resources when planning for and navigating tough scenarios like this. If working with an IRB is new to you, we recommend finding colleagues at your institution who have conducted IRB-reviewed research and asking them for guidance and examples. Some IRBs offer training for individuals new to developing human research protocols, and there are likely to be templates for everything from recruitment letters to consent forms to study information. We have found the process of developing IRB protocols helps refine research questions and study plans. Furthermore, IRB review is needed before you collect data that will be used for your study; IRBs rarely if ever allow for retrospective review and approval. In our experience, these studies are likely to be determined as exempt from IRB review because they involve minimal risk and use standard educational research procedures. However, the IRB is still responsible for making this determination and is a valuable partner for helping investigators navigate sensitive or complex situations that occur in human research.

Getting Started with Qualitative Research

Now that you have a sense of the purposes of qualitative research and what features help to ensure its quality, you are probably wondering how to do it. We want to emphasize that there are entire programs of study, whole courses, and lengthy texts that aim to teach qualitative research. We cannot come close to describing what can be learned from these more substantial resources. With this is mind, we share our own process of carrying out qualitative research as an example that others might find helpful to follow. We outline this “how to” as a series of steps, but qualitative research (like all research) is iterative and dynamic (University of California Museum of Paleontology 2022). Feel free to read through the steps in a linear fashion but then move in non-linear ways through the various steps. Extended discussion of each of these steps with examples from our research on negative mentoring is provided in Table 1 along with an abridged list of our go-to references.

Observe, Search, and Read

For a topic to be worthy of qualitative research (or any research), it should also have the potential to address a knowledge gap. After we identify a “worthy topic,” we try to find as much information about that topic as possible (Dolan 2013). We read, then we keep reading, and then we read some more. This may seem obvious, but we find that investing time reading literature can save us a lot of time designing, conducting, and writing up a study on a phenomenon that is already well known or understood by others and just not (yet) by us. To help us in our searching, we will sometimes reach out to colleagues in related fields to describe the phenomenon we are interested in studying and see if they have terms that they use to describe the phenomenon or theories they think are related. Theory informs our research questions, study designs, analytic approaches, and interpretation and reporting of findings, and enables alignment among all of these elements of research (e.g., Grant and Osanloo 2014; Luft et al. 2022; Spangler and Williams 2019). Theory also serves as a touchstone for connecting our findings to larger bodies of knowledge and communicating these connections in a way that promotes collective understanding of whatever we are investigating.

Formulate a Question

Once you have selected a topic and identified a knowledge gap, consider research questions that, if answered, would address the knowledge gap. Recall that qualitative research is suited to questions that require a descriptive (what) or mechanistic (how) answer.

Decide on a Study Design

Just like quantitative research, qualitative research has characteristic approaches, designs, and methodologies, each of which has affordances and constraints (Creswell and Poth 2016; Merriam 2014; Miles, Huberman, and Saldana 2014). Creswell and Poth provide a valuable resource for learning more about different types of qualitative research study designs, including which designs are suited to address which kinds of research questions. Given the labor intensiveness of qualitative data collection and analysis, it is critical to think carefully about how to recruit and select study participants. What this looks like and who might be appropriate study participants will depend on many factors, including the knowledge gap, research question, study design, and methods. Questions that can be helpful to ask are: Who do I need to study to answer my research question? What should the study participants have in common? In what ways should study participants vary to provide rich, complex, and varied insight into what I am studying? To whom do I want to generalize my findings, keeping in mind the qualitative nature of the work?

Based on the answers to these questions, you may opt for purposeful sampling in which you collect data only from participants who meet the characteristics you decide upon given the aims of your study. In this case, you will likely send a screening survey to potential participants to determine what their characteristics of interest are, which will help you decide if you will invite them for further data collection or not. A purposeful sample contrasts with a convenience sample where essentially any person who agrees to participate in the study will be selected for further data collection.

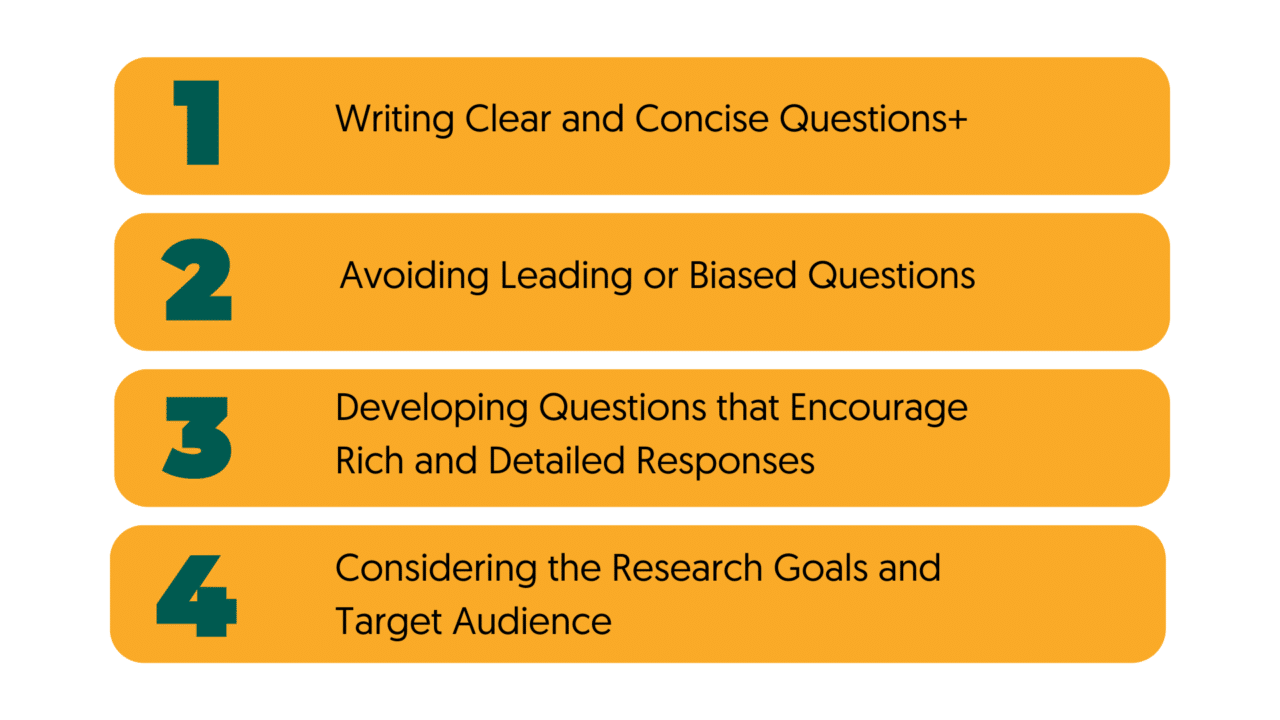

Collect and Analyze Data Systematically

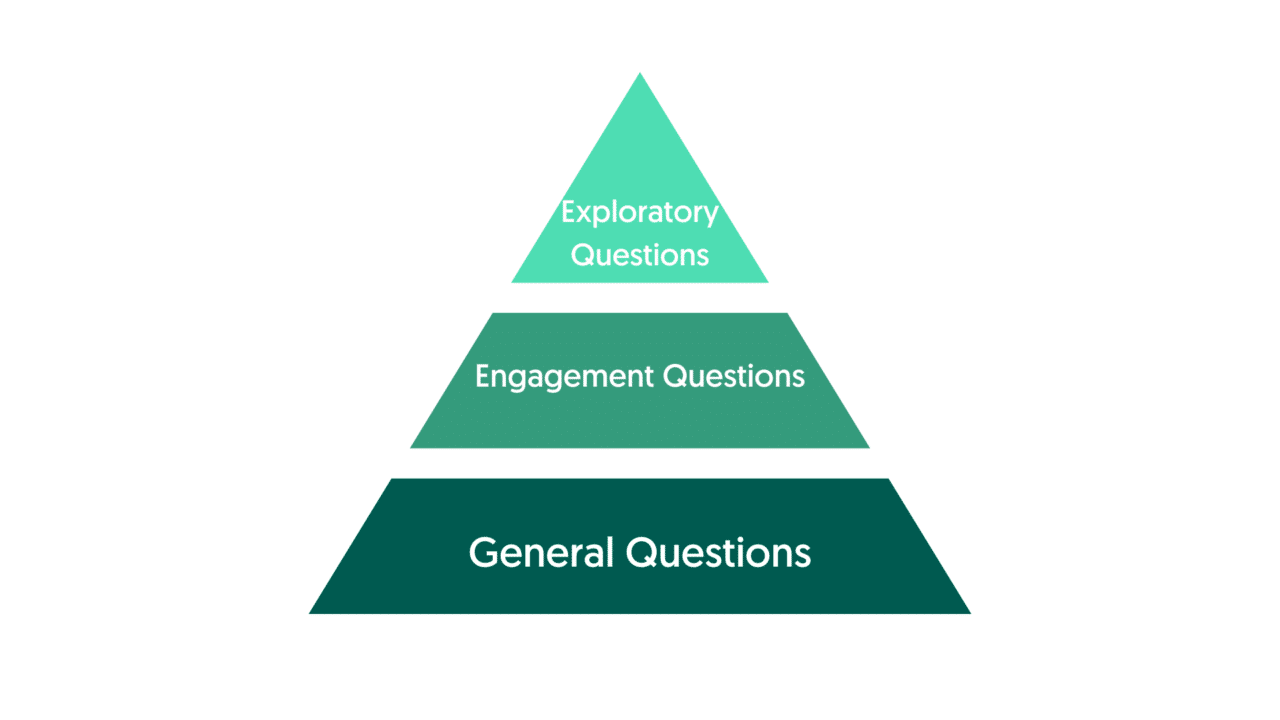

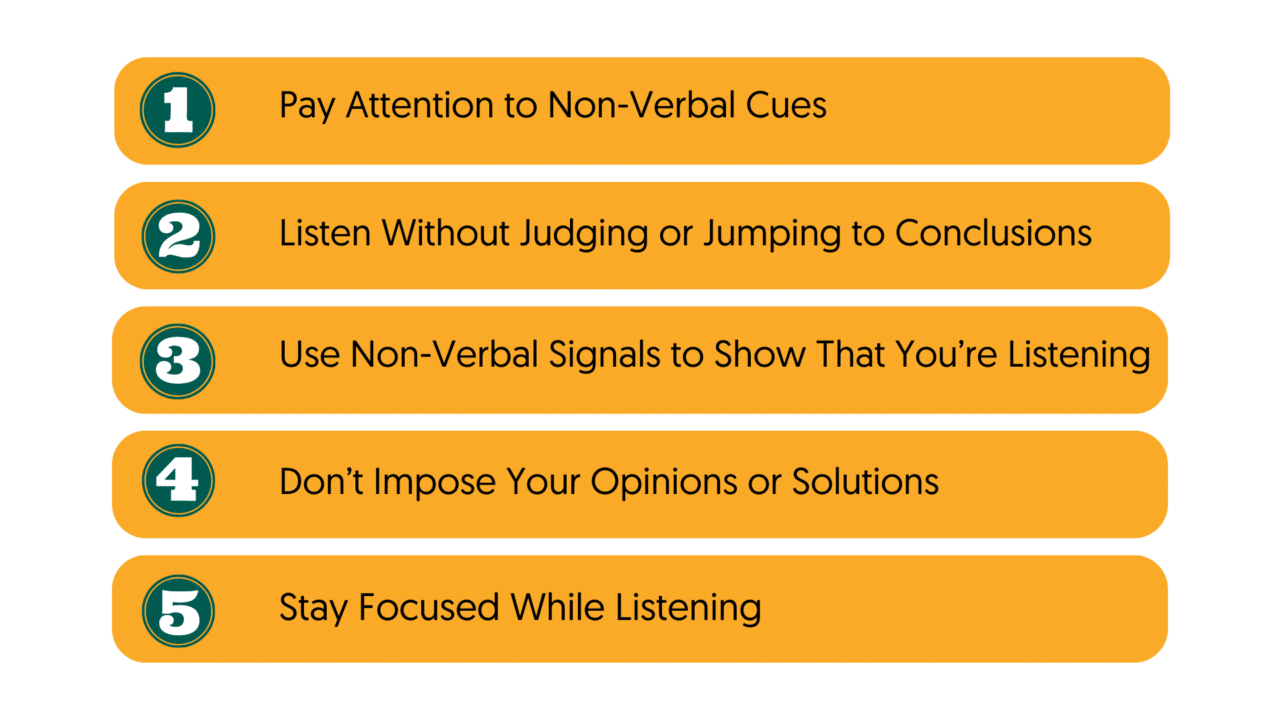

Qualitative data can be collected in a variety of ways, including surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as audio and video recordings of learning experiences such as class sessions. To decide which method(s) to use for data collection, it is helpful to consider what you aim to learn from study participants. Surveys tend to be easier to distribute to a larger sample, but may elicit shorter or shallower responses, which are challenging to interpret because there is less information (i.e., words) and no opportunity to clarify with participants. Focus groups can be effective for quickly gathering input from a group of participants. However, social dynamics may result in one or a few people dominating the discussion, or “group think,” when people agree with one another rather than providing their own unique perspectives. Interviews with individuals can be a rich and varied data source because each participant has time and space to offer their own distinct perspective. Interviews also allow for follow-up questions that are difficult through survey methods. Yet, conducting interviews skillfully—avoiding leading questions and ensuring that the line of questioning yields the desired data—takes a lot of thought and practice. Kvale (1996) offers detailed guidance on how to design and carry out research interviews. Observing an expert interviewer and having them observe and give feedback as you interview can help improve your skills. Audio and video recordings of learning experiences like class sessions or group work can provide a plethora of information (e.g., verbal and nonverbal exchanges among students or between students and instructors) in a more natural setting than surveys or interviews. Yet deciding what information will serve as data to answer your research question, or how that large body of data will be systematically analyzed, can be cumbersome.

Regardless of the data collection method, you’ll need to decide how much data to collect. There is no one right sample size. A good rule of thumb is collecting data until you reach “saturation,” which is the notion that the same ideas are coming up repeatedly and that no new ideas are emerging during data collection. This means that your data collection and analysis are likely to overlap in time, with some data collection then some analysis and then more data collection.

Analytic methods in qualitative research vary widely in their interpretive complexity. As natural scientists, we favor sticking close to the data and analyzing using a method called qualitative content analysis. Content analysis involves taking quotes or segments of text and capturing their meaning with short words or phrases called codes. The process of developing codes and systematically applying them to a dataset is called coding. Coding is highly iterative and time-consuming because it typically requires multiple, careful passes through the dataset to ensure all codes have been evenly applied to all data. In a recent study, we spent 10 to 15 person-hours to code a single interview, and about 400 person-hours to complete coding for a 30-participant study. The time involved in coding depends on what is being studied, the type of coding, and who is coding the data. Saldaña (2016) provides excellent guidance on the coding process, including various ways of making sense of codes by grouping them into themes. Content analysis is just one approach to qualitative data analysis. We encourage you to learn more about different forms of qualitative approaches and choose what works best for you, including your skill level, research goals, and data (e.g., Creswell and Poth 2016; Starks and Brown Trinidad 2007).

Interpret and Write Results

There are many ways to effectively write up results, often called findings, from qualitative research. Because qualitative research involves extensive interpretation, it can sometimes be easier to integrate the results and discussion of a qualitative paper. Integration allows the interpretation (discussion) to be directly supported by the evidence in the form of quotations (results). The conclusions of the paper should avoid repeating the results and instead comment on the implications and applications of the findings: why they matter and what to do as a result. Because qualitative data are quotations rather than numbers, qualitative papers tend to be longer than papers presenting quantitative studies. That said, qualitative papers should still aim to be succinct. For instance, depending on the approach and methods, quotations can be lightly edited to remove extra words or filler language (e.g., um, uh) that is a natural part of language but otherwise irrelevant to the findings. Presenting only the most pertinent part of a quotation not only facilitates succinctness, but helps readers attend to the specific evidence that supports the claims being made. Another strategy to shorten qualitative papers is to present some findings in supplemental materials.

Final Recommendations

In closing our article, we offer some advice that we wish we knew when we began conducting qualitative research. We hope that these recommendations will help you think through issues that are likely emerge as you delve deeper into qualitative analysis, both as a producer and a consumer of qualitative research.

Consensus Coding in Qualitative Analysis

In qualitative analysis, we work to ensure that the analysis yields trustworthy findings by coding to consensus, meaning that the analytic team reaches 100 percent agreement on the application of each code to the data. Any disagreement between coders is discussed until a resolution is resolved. In some cases, these discussions may result in a code description being redefined. Redefinition of a code requires that all data previously coded using the original code be reanalyzed to ensure fit with the revised definition. As you might imagine, coding to consensus can be time-consuming. Yet, in our experience, the time invested in coding to consensus is well spent because the analysis yields deeper insights about the data and phenomenon being investigated. We also see coding to consensus as a great way to take advantage of the diverse viewpoints that team members bring to our research. By coding to consensus, we consider multiple interpretations of the data throughout the analysis process. We are well-positioned to develop theory (as appropriate for our study design) as a team because we all have engaged in meaningful conversations about our findings throughout analysis.

Some qualitative research relies on a calculated measure of intercoder reliability (ICR) instead of coding to consensus. ICR values indicate how often a set of coders agree on the application of a code in the dataset. This quantification of coding is tempting because we love numbers, yet it can also be problematic (O’Connor and Joffe 2020). For instance, aiming for high ICR can create situations when coders are pressured to agree with each other rather than bringing their own unique perspective to the coding process (e.g., Belur et al. 2018; Morse 1997). Quantifying qualitative work also can imply a false precision in the analysis. In some research, ICR is calculated partway through the analysis to determine whether an “acceptable” level of agreement has been reached, at which point the remainder of the data are coded by just one researcher. This approach of using ICR as a cut-off runs counter to what many argue is the value of qualitative research: generating new theoretical understandings informed by multiple perspectives.

Using Numbers in Qualitative Analysis

Although numbers certainly have a place in qualitative analysis (Sandelowski 2001), we encourage researchers to move beyond word clouds or frequency counts of codes and themes in their results for two reasons. First, a code or theme that is infrequently observed in the data set can still be important to the phenomenon being studied. As an analogy, consider making qualitative observations of living cells under a typical light microscope. We would most frequently see a relatively stationary cell that is punctuated by a relatively rare cell division or mitosis. If we only reported stationary observations in findings, we would overlook describing mitosis, one of the most dynamic and fundamental processes that cells display. Second, given limited sample sizes, it may be that a unique and important code or theme is reported by only one participant in the data set. In fact, rare observations can serve as “a-ha moments” that lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. These rare observations also may inspire new studies about topics that were not initially anticipated; this speaks to the value of qualitative research.

Closing Thoughts

We encourage readers to continue to learn about qualitative research as there is much that could not be addressed in a single article. For instance, we did not introduce how philosophical stances, like how someone views the nature of truth or what counts as evidence, influence the research process. (Creswell and Poth 2016). For now, we will close with one final piece of advice. We both became better qualitative researchers by working with mentors and collaborators who have this expertise. We encourage you to find colleagues in your networks or at your institutions who may be interested in being a collaborator, mentor, or critical friend. The complexity of students and their experiences lend themselves to qualitative approaches. We hope this article might serve as an impetus for you to learn more about qualitative research and even start your own investigations.

Data Availability Statement

The data included in this commentary have been published in an open-access journal under a Creative Commons license. Citations are included in the text.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under award number OCE-2019589. This is the National Science Foundation’s Center for Chemical Currencies of a Microbial Planet (C-Comp) publication #026. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. We thank Patricia Mabrouk for inviting us to contribute this commentary. We thank members of the Biology Education Research Group at the University of Georgia and Daniel Dries, Joseph Provost, and Verónica Segarra for their thoughtful feedback on manuscript drafts.

Agee, Jane. 2009. “Developing Qualitative Research Questions: A Reflective Process.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 22: 431–447. doi: 10.1080/09518390902736512

Aikens, Melissa L., Melissa M. Robertson, Sona Sadselia, Keiana Watkins, Mara Evans, Christopher R. Runyon, Lillian T. Eby, and Erin L. Dolan. 2017. “Race and Gender Differences in Undergraduate Research Mentoring Structures and Research Outcomes.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 16(2): ar34. doi:10.1187/cbe.16-07-0211

Aikens, Melissa L., Sona Sadselia, Keiana Watkins, Mara Evans, Lillian T. Eby, and Erin L. Dolan. 2016. “A Social Capital Perspective on the Mentoring of Undergraduate Life Science Researchers: An Empirical Study of Undergraduate–Postgraduate–Faculty Triads.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 15(2): ar16. doi: 10.1187/cbe.15-10-0208

Anfara, Vincent A., Kathleen M. Brown, and Terri L. Mangione. 2002. “Qualitative Analysis on Stage: Making the Research Process More Public.” Educational Researcher 31(7): 28–38. doi:10.3102/0013189X031007028

Belur, Jyoti, Lisa Tompson, Amy Thornton, and Miranda Simon. 2018. “Interrater Reliability in Systematic Review Methodology: Exploring Variation in Coder Decision-Making.” Sociological Methods & Research 50: 837–865. doi:10.1177/0049124118799372

Carlone, Heidi B., and Angela Johnson. 2007. “Understanding the Science Experiences of Successful Women of Color: Science Identity as an Analytic Lens.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 44: 1187–1218. doi: 10.1002/tea.20237

Castillo-Montoya, Milagros. 2016. “Preparing for Interview Research: The Interview Protocol Refinement Framework.” Qualitative Report 21: 811–831. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2337

Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis . London: Sage.

Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches . Sage.

Dolan, Erin L. 2013. “Biology Education Scholarship.” IBiology. https://www.ibiology.org/career-exploration/biology-educationscholarship

Gentile, Jim, Kerry Brenner, and Amy Stephens, eds. 2017. Undergraduate Research Experiences for STEM Students: Successes, Challenges, and Opportunities . Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24622/undergraduate-research-experiences-for-stem-students-successes-challenges-and-opportunities

Gioia, Denny, Kevin Corley, Kathleen Eisenhardt, Martha Feldman, Ann Langley, Jane Lê, Karen Golden-Biddle, et al. 2022. “A Curated Debate: On Using ‘Templates’ in Qualitative Research.” Journal of Management Inquiry 31: 231–52. doi:10.1177/10564926221098955

Goldberg, Abbie E., and Katherine R. Allen. 2015. “Communicating Qualitative Research: Some Practical Guideposts for Scholars.” Journal of Marriage and Family 77 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1111/jomf.12153

Grant, Cynthia, and Azadeh Osanloo. 2014. “Understanding, Selecting, and Integrating a Theoretical Framework in Dissertation Research: Creating the Blueprint for Your ‘House.’” Administrative Issues Journal 4(2): 4. https://dc.swosu.edu/aij/vol4/iss2/4

Hampton, Cynthia, David Reeping, and Desen Sevi Ozkan. 2021. “Positionality Statements in Engineering Education Research: A Look at the Hand That Guides the Methodological Tools.” Studies in Engineering Education 1(2): 126–141. doi: 10.21061/see.13

Hazari, Zahra, Deepa Chari, Geoff Potvin, and Eric Brewe. 2020. “The Context Dependence of Physics Identity: Examining the Role of Performance/Competence, Recognition, Interest, and Sense of Belonging for Lower and Upper Female Physics Undergraduates.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 57:1583–1607. doi: 10.1002/tea.21644

Hazari, Zahra, Gerhard Sonnert, Philip M. Sadler, and Marie-Claire Shanahan. 2010. “Connecting High School Physics Experiences, Outcome Expectations, Physics Identity, and Physics Career Choice: A Gender Study.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 47: 978–1003. doi: 10.1002/tea.20363

Holmes, Andrew, and Gary Darwin. 2020. “Researcher Positionality: A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research; A New Researcher Guide.” Shanlax International Journal of Education 8(4): 1–10. doi: 10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

Hunter, Anne-Barrie, Sandra L. Laursen, and Elaine Seymour. 2007. “Becoming a Scientist: The Role of Undergraduate Research in Students’ Cognitive, Personal, and Professional Development.” Science Education 91: 36–74. doi: 10.1002/sce.20173

Joshi, Megha, Melissa L. Aikens, and Erin L. Dolan. 2019. “Direct Ties to a Faculty Mentor Related to Positive Outcomes for Undergraduate Researchers.” BioScience 69: 389–397. doi10.1093/biosci/biz039

Kim, Ann Y., and Gale M. Sinatra. 2018. “Science Identity Development: An Interactionist Approach.” International Journal of STEM Education 5: 51. doi: 10.1186/s40594-018-0149-9

Knott, Eleanor, Aliya Hamid Rao, Kate Summers, and Chana Teeger. 2022. “Interviews in the Social Sciences.” Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2: 73. doi: 10.1038/s43586-022-00150-6

Korstjens, Irene, and Albine Moser. 2017. “Series: Practical Guidance to Qualitative Research. Part 2: Context, Research Questions and Designs.” European Journal of General Practice 23: 274–279. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375090

Kvale, Steinar. 1996. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kyngäs, Helvi, Kristina Mikkonen, and Maria Kääriäinen, eds. 2020. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research . Cham: Springer International. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6

Limeri, Lisa B., Muhammad Zaka Asif, Benjamin H. T. Bridges, David Esparza, Trevor T. Tuma, Daquan Sanders, Alexander J. Morrison, Pallavi Rao, Joseph A. Harsh, and Adam V. Maltese. 2019. “‘Where’s My Mentor?!’ Characterizing Negative Mentoring Experiences in Undergraduate Life Science Research.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 18(4): ar61. doi: 10.1187/cbe.19-02-0036

Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry . Sage.

Loeb, Susanna, Susan Dynarski, Daniel McFarland, Pamela Morris, Sean Reardon, and Sarah Reber. 2017. “Descriptive Analysis in Education: A Guide for Researchers.” NCEE 2017-4023. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Luft, Julie A., Sophia Jeong, Robert Idsardi, and Grant Gardner. 2022. “Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 21(3): rm33. doi: 10.1187/cbe.21-05-0134

Majocha, Megan, Zachary Davenport, Derek C. Braun, and Cara Gormally. 2018. “‘Everyone Was Nice . . . But I Was Still Left Out’: An Interview Study about Deaf Interns’ Research Experiences in STEM.” Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education 19(1): 19.1.10. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v19i1.1381

Mays, Nicholas, and Catherine Pope. 2020. “Quality in Qualitative Research.” In Qualitative Research in Health Care , ed. Catherine Pope and Nicholas Mays, 211–233. doi:10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGee, Ebony O., and Lydia Bentley. 2017. “The Troubled Success of Black Women in STEM.” Cognition and Instruction 35: 265–289. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2017.1355211

Merriam, Sharan B. 2014. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco: Wiley.

Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldana. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morse, Janice M. 1997. “‘Perfectly Healthy, but Dead’: The Myth of Inter-Rater Reliability.” Qualitative Health Research 7:445–47. doi: 10.1177/104973239700700401

Morse, Janice M., Michael Barrett, Maria Mayan, Karin Olson, and Jude Spiers. 2002. “Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 1(2): 13–22. Doi:10.1177/160940690200100202

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. 1978. “The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research.” 3 vols. Bethesda, MD: National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/779133

O’Connor, Cliodhna, and Helene Joffe. 2020. “Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19:1609406919899220. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220

Pfeifer, Mariel A., Julio J. Cordero, and Julie Dangremond Stanton. 2023. “What I Wish My Instructor Knew: How Active Learning Influences the Classroom Experiences and Self-Advocacy of STEM Majors with ADHD and Specific Learning Disabilities.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 2(1): ar2. doi: 10.1187/cbe.21-12-0329

Pfeifer, Mariel A., C. J. Zajic, Jared M. Isaacs, Olivia A. Erickson, and Erin L. Dolan. 2023. “Beyond Performance, Competence, and Recognition: Forging a Science Researcher Identity in the Context of Research Training.” BioRxiv 2023.03.22.533783. doi: 10.1101/2023.03.22.533783

Potvin, Geoff, and Zahra Hazari. 2013. “The Development and Measurement of Identity across the Physical Sciences.” 2013 PERC Proceedings . American Association of Physics Teachers. https://www.compadre.org/Repository/document/ServeFile.cfm?ID=13182&DocID=3729

Pratt, Michael G., Kevin W. Rockmann, and Jeffrey B. Kaufmann. 2006. “Constructing Professional Identity: The Role of Work and Identity Learning Cycles in the Customization of Identity among Medical Residents.” Academy of Management Journal 49: 235–262. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2006.20786060

Ritchie, Jane, Jane Lewis, Carol McNaughton Nicholls, and Rachel Ormston. 2013. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers . Sage.

Roulston, Kathryn, Kathleen deMarrais, and Jamie B. Lewis. 2003. “Learning to Interview in the Social Sciences.” Qualitative Inquiry 9: 643–668. doi: 10.1177/1077800403252736

Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers . 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

Sandelowski, Margarete. 1995. “Qualitative Analysis: What It Is and How to Begin.” Research in Nursing & Health 18: 371–375. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180411

Sandelowski, Margarete. 1998. “Writing a Good Read: Strategies for Re-Presenting Qualitative Data.” Research in Nursing & Health 21: 375–382. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199808)21:4<375::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-C

Sandelowski, Margarete. 2001. “Real Qualitative Researchers Do Not Count: The Use of Numbers in Qualitative Research.” Research in Nursing & Health 24: 230–240. doi: 10.1002/nur.1025

Spangler, Denise A., and Steven R. Williams. 2019. “The Role of Theoretical Frameworks in Mathematics Education Research.” In Designing, Conducting, and Publishing Quality Research in Mathematics Education , ed. Keith R. Leatham, 3–16. Research in Mathematics Education. Cham: Springer International. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-23505-5_1

Starks, Helene, and Susan Brown Trinidad. 2007. “Choose Your Method: A Comparison of Phenomenology, Discourse Analysis, and Grounded Theory.” Qualitative Health Research 17: 1372–1380. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307031

Tracy, Sarah J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight ‘Big-Tent’ Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16:837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

University of California Museum of Paleontology. 2022. “Understanding Science: Science Flowchart.” UC Museum of Paleontology Understanding Science. https://undsci.berkeley.edu/science-flowchart

Vaccaro, Annemarie, Ezekiel W. Kimball, Ryan S. Wells, and Benjamin J. Ostiguy. “Researching students with disabilities: The importance of critical perspectives.” New directions for institutional research 2014, no. 163 (2015): 25-41. doi: 10.1002/ir.20084

Vasquez-Salgado, Yolanda, Tissyana C. Camacho, Isabel López, Gabriela Chavira, Carrie L. Saetermoe, and Crist Khachikian. 2023. “‘I Definitely Feel like a Scientist’: Exploring Science Identity Trajectories among Latinx Students in a Critical Race Theory–Informed Undergraduate Research Experience.” Infant and Child Development 32(3): e2371. doi: 10.1002/icd.2371

Watson, Rachel M., John D. Willford, and Mariel A. Pfeifer. 2018. “A Cultured Learning Environment: Implementing a Problem-and Service-Based Microbiology Capstone Course to Assess Process- and Skill-Based Learning Objectives.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning 12(1): article 8. doi:10.7771/1541-5015.1694

Welch, Catherine. 2018. “Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate.” In Collaborative Research Design: Working with Business for Meaningful Findings , 401–412. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5008-4

Yadav, Drishti. 2022. “Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review.” Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 31 679–689. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Yilmaz, Kaya. 2013. “Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: Epistemological, Theoretical, and Methodological Differences.” European Journal of Education 48: 311–325. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12014

Mariel A. Pfeifer

University of Georgia, [email protected]

Mariel A. Pfeifer is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia’s SPREE (Social Psychology of Research Experiences and Education) Lab. Her passion for biology education research was sparked by her experiences as an undergraduate teaching assistant, a pre-service science teacher, and a disability services coordinator. Soon Pfeifer will begin her new role as an assistant professor of biology at the University of Mississippi.

Erin L. Dolan is a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and Georgia Athletic Association Professor of Innovative Science Education at the University of Georgia As a graduate student, Dolan volunteered in K–12 schools, which inspired her pursuit of a biology education career. She teaches introductory biology and her research group, the SPREE Lab, works to delineate features of undergraduate and graduate research that influence students’ career decisions.

More Articles in this Issue

Table of contents – fall 2023, quantifying equity in the american theater: student research at the intersection of performance and data analysis.

Dramatic literature courses in the undergraduate theater curriculum traditionally include the study of plays: their structure and themes. In a course titled Contemporary Female Playwrights at Davidson College, the learning goals go beyond script analysis and include strategies for documenting and redressing the underrepresentation of female and BIPOC playwrights in American theater.

Building Research Skills through an Undergraduate Research Project on Local Community

This research aims to build economic research skills and stimulate students’ interest in the local economy through data-based undergraduate research in entry-level economics courses. The authors developed two assignments and one student survey assessing students’ learning outcomes and implemented them in two introductory-level classes from fall 2019 to fall 2021. The survey responses confirmed that the assignments positively affected students’ primary research skills and increased students’ interest in local economic issues. The study also provides empirical evidence that undergraduate research can be carried out in both face-to-face and online classes. It confirms the positive contribution of exposing students to the research culture early in their academic journey by improving students’ skills in collecting, processing, and interpreting data on the local economy.

Fulfilling the Land-Grant Mission in Undergraduate Research in English Studies

The pandemic provided a natural experiment to test an alternative approach to teaching a traditional classroom-based research methods course; as teachers, we should not wait for such interventions but try out various strategies for effectiveness. Remote mentoring is entirely feasible for successful undergraduate research experiences. This is a particularly crucial finding in the humanities, which relies very much on discussion-based formats rather than lectures for its courses. Faculty have learned new technologies, such as Zoom, to ensure that meaningful interactions would occur.

Making Research Accessible for All through a Fully Online Cancer Genomics CURE

Course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) can engage large numbers of students and provide a structured environment in which to learn valuable research skills. The ability to implement laboratory-based CUREs was hindered by the COVID-19 pandemic, generating a greater need for online options. A pilot study of an adaptation of a fully online cancer genomics CURE is described here. Students utilized freely available databases such as cBioPortal to develop novel scientific questions, generate and analyze data, collaborate with peers, and present their findings in an online environment. This format preserved the defining aspects of CUREs while promoting student ownership over their projects. Although the most common challenge was developing a hypothesis, students valued peer and instructor feedback throughout the process as well as flexible formats for communicating their research findings.

Laboratory-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences (LUREs): Evidence of Effectiveness from the Social Sciences

The impact of undergraduate research experiences (UREs) is supported by evidence from physical and life science fields, especially when student-apprentices work in traditional laboratories. Within social sciences specifically, some excellent student outcomes associated with UREs adhere to non–lab-based modalities like course-based research experiences (CUREs). Here, the authors evaluate the laboratory-based undergraduate research experiences (LUREs) as a potentially valuable approach for incorporating social science undergraduates in research. Using comparative analysis of survey data from students completing three types of social science-based UREs (n = 235), individual research experiences (IREs), CUREs, or LUREs, students perceived gains overall regardless of the type of experience, with some indication that LUREs are the most effective.

SUREbyts: Presenting Early-Year Undergraduate Students with Videos on Research Topics

Undergraduate research initiatives such as mentoring programs, conferences, and journals typically focus on the later stages of undergraduate studies. It is not unusual for a student to reach the final year of their program without developing their awareness of research within their discipline or their institution. SUREbyts is a project that provides first- and second-year undergraduate students with access to research through video recordings of professional researchers and research students discussing their own research, with each video structured around a research question with a set of possible solutions. This article presents the successes and challenges faced by the project’s initial implementation in six higher education institutions in Ireland and offers advice to institutions globally that are considering engaging their students with research in this way.

Systematic Review of Outcomes for Faculty Mentors in Undergraduate Research

Significant research has highlighted the benefits and outcomes of mentored research experiences for undergraduate students. Substantially less empirical research has examined the benefits and outcomes of these experiences for the other member of the mentoring dyad: the mentors themselves. To address this gap, a systematic review of 1,915 articles was conducted. After review, 16 articles were determined relevant. Articles were categorized based on design and theoretical framework. Further analysis revealed three categorizations: faculty mentor outcomes, barriers to mentorship of undergraduate research students, and supporting factors associated with mentorship of students. Results indicate that faculty mentors in undergraduate research contexts face more barriers to mentorship than supporting factors. Three lines of inquiry are proposed for future researchers.

Undergraduate Research: Why and How Do We Mentor?

Our advocacy for undergraduate research, mentorship, and equity is strengthened by being explicit about why they are vital. Research mentors guide undergraduates in learning how to learn, in evaluating evidence, and in discovering talents and career interests. Our mission can be extended by bringing a research perspective to the courses we teach. Effective mentorship involves appreciating individual differences while having shared goals. As mentors, we aim to provide undergraduates with opportunities to participate in research that can lead to discovering new knowledge. Students can build on this experience to become proactive in making a difference. The global future depends on today’s undergraduates, who are tomorrow’s decision-makers, innovators, and leaders.

Step Up for SPUR

This editorial details observations from a departing associate editor of SPUR about the experience of working on the journal. The author contextualizes this work within the academic journal editorial process, focusing on specific challenges in recruiting reviewers for the peer review process. The author stresses the importance of broad participation from the undergraduate research community, including submitting articles to SPUR , accepting requests to review manuscripts, and participating in the editorial board, all to ensure the sustainability and intellectual vitality of the journal.

SUBSCRIPTION

SPUR advances knowledge and understanding of novel and effective approaches to mentored undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry by publishing high-quality, rigorously peer reviewed studies written by scholars and practitioners of undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry. The SPUR Journal is a leading CUR member benefit. Gain access to all electronic articles by joining CUR.

- Find Studies

For Researchers

- Learn about Research

What is a qualitative research study?

A qualitative study is one that collects and looks at qualitative data – essentially, words! Researchers will talk to people to learn about their thoughts, beliefs, and experiences in their own words. This information can help researchers, healthcare providers, and people who design policies and programs know things like:

- What life is like for people impacted by a health condition

- How people feel about social issues

- How to design programs so that they fit with people’s lives.

How are qualitative research studies different from other types of studies?

Sometimes, questions are best answered by clinical trials or by looking at statistics or numbers. These kinds of studies are called quantitative research. Other times, questions are best answered by hearing about people’s experiences and perspectives in their own words. This is where qualitative studies come in!

For example, let’s say we want to study we want to better understand people’s exercise habits.

In a quantitative study, meaning one focused on numbers, we might study questions like:

- What percent of people exercise regularly?

- What is the average number of minutes people exercise each week?

- How do these numbers vary between people of different socioeconomic statuses?

In a qualitative study, we might study questions like:

- How do people feel about exercise?

- What things prevent people from exercising?

- What strategies help people exercise?

Together, these questions can paint a richer picture of what is happening. If we know that some groups of people exercise less than others, we don’t necessarily know why that is the case. If we talk to people directly, we can better understand their experiences, challenges they face, and strategies that are helpful. This information may help us design more effective programs to encourage exercising.

How is a qualitative research study conducted?

In qualitative research, we study the experiences, stories, and perspectives that people share with researchers – this is qualitative data . Usually, researchers will collect qualitative data by talking to people through interviews or focus groups. Interviews are one-on-one conversations where researchers ask people about their experiences and thoughts related to a certain topic. Focus groups are similar, except that the conversation happens with a group of people. Interviews and focus groups can happen in-person or virtually (over the phone or on an online platform like Zoom). Researchers usually record these conversations so that they can transcribe them, meaning write them out word for word. Generally, they will remove people’s names and other identifying information from the transcripts. Then they review the de-identified transcript data and identify concepts or themes from across all the conversations.

While this is the most common type of qualitative study, there are lots of other ways to do qualitative research too! For example, researchers can study what people write in journals or surveys, or even look at drawings or photos people have created about their experiences.

How is qualitative research shared?

Researchers will summarize the information they learned from their conversations, often by writing a report or paper. This summary will not include people’s names but might include quotations or stories people shared. This lets healthcare providers, researchers, and others better understand how people think and feel about different topics. This understanding can help us develop and improve healthcare delivery, programs, and policies. Participating in a qualitative research study is a great way to share your story and contribute to improving health!

Copyright © 2013-2022 The NC TraCS Institute, the integrated home of the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program at UNC-CH. This website is made possible by CTSA Grant UL1TR002489 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Helpful Links

- My UNC Chart

- Find a Doctor

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

Basics of qualitative research

Types, aspects, examples, benefits and challenges, how qualitative research complements quantitative research, how is qualitative research reported.

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Ethnographical research

Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is an essential approach in various academic disciplines and professional fields, as it seeks to understand and interpret the meanings, experiences, and social realities of people in their natural settings. This type of research employs an array of qualitative methods to gather and analyze non-numerical data, such as words, images, and behaviors, and aims to generate in-depth and contextualized insights into the phenomena under study.

Qualitative research is designed to address research questions that focus on understanding the "why" and "how" of human behavior, experiences, and interactions, rather than just the "what" or "how many" that quantitative methods typically seek to answer. The main purpose of qualitative research is to gain a rich and nuanced understanding of people's perspectives, emotions, beliefs, and motivations in relation to specific issues, situations, or phenomena.

Characteristics of qualitative research

Several key characteristics distinguish qualitative research from other types of research, such as quantitative research:

Naturalistic settings : Qualitative researchers collect data in the real-world settings where the phenomena of interest occur, rather than in controlled laboratory environments. This allows researchers to observe and understand the participants' behavior, experiences, and social interactions in their natural context.

Inductive approach : Unlike quantitative research, which often follows a deductive approach , qualitative research begins with the collection of data and then seeks to develop theories, concepts, or themes that emerge from the data. This inductive approach enables researchers to stay open to new insights and unexpected findings.

Holistic perspective : Qualitative research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena under study by considering multiple dimensions, such as the social, cultural, historical, and psychological aspects that shape people's experiences and behavior.

Subjectivity and interpretation : Epistemology plays a crucial role in qualitative research. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their biases, assumptions, and values , and to consider how these may influence their data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Flexibility : Qualitative research methods are often flexible and adaptable, allowing researchers to refine their research questions , sampling strategies, or data collection techniques as new insights and perspectives emerge during the research process.

Key principles of qualitative research

Qualitative research is guided by several fundamental principles that shape its approach, methods, and analysis:

Empathy and reflexivity : Qualitative researchers strive to empathize with the participants and to understand their perspectives, experiences, and emotions from their viewpoint. This requires researchers to be attentive, open-minded, and sensitive to the participants' verbal and non-verbal cues. At the same, qualitative researchers critically reflect on their participants’ perspectives, experiences, and emotions to develop their findings and conclusions, instead of taking these at face value. In addition, it is important for the researcher to reflect on how their own role and viewpoint may be shaping the research.

Trustworthiness : Establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research involves demonstrating credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Researchers can enhance trustworthiness by using various strategies, such as triangulation, member checking , peer debriefing , and reflexivity .

Iterative analysis : Qualitative data analysis is an ongoing and iterative process, in which researchers continually review, compare, and revise their interpretations as they collect and analyze more data. This iterative process allows researchers to refine their understanding of the phenomena and to develop more robust and nuanced theories, concepts, or themes.

Rich description : Providing detailed, vivid, and context-sensitive descriptions of the data is essential in qualitative research. Rich descriptions help convey the complexity and nuances of the phenomena under study, and enable readers to assess the relevance and transferability of the findings to other settings or populations.

What are the common types of qualitative research?

Qualitative research is an umbrella term for various methodologies that focus on understanding and interpreting human experiences, behaviors, and social phenomena within their context. These approaches seek to gather in-depth, rich data through the analysis of language, actions, and expressions. Five common types of qualitative research are narrative research , phenomenology , grounded theory , ethnography , and case study .

Narrative research : This approach focuses on the stories and experiences of individuals, aiming to understand their lives and personal perspectives. Researchers can collect data through interviews, letters, diaries, or autobiographies, and analyze these narratives to identify recurring themes, patterns, and meanings . Narrative research can be valuable for exploring individual identities, cultural beliefs, and historical events.

Phenomenology : Phenomenology seeks to understand the essence of a particular phenomenon by analyzing the experiences and perceptions of individuals who have gone through that phenomenon . Researchers can explore participants' thoughts, feelings, and experiences through in-depth interviews, observations, or written materials. The goal is to describe the commonalities and variations in these experiences, ultimately revealing the underlying structures and meaning of the phenomenon under study.

Grounded theory : This inductive research method aims to generate new theories by systematically collecting and analyzing data. Researchers begin with an open-ended research question and gather data through observations, interviews, and document analysis . They then use a process of coding and constant comparison to identify patterns, categories, and relationships in the data. This iterative process continues until a comprehensive, grounded theory emerges that is based in the recollected data and explains the topic of interest.