Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Tips for Students > Dissertation Explained: A Grad Student’s Guide

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Dissertation Explained: A Grad Student’s Guide

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: March 10, 2020

In this article

Higher education is filled with milestones. When completing your PhD , you will be required to complete a dissertation. Even if you’ve heard this word thrown around before, you still may be questioning “What is a dissertation?” It’s a common question, especially for those considering to join or are already in a graduate program. As such, here’s everything you need to know about dissertations.

What is a Dissertation?

A dissertation is a written document that details research. A dissertation also signifies the completion of your PhD program. It is required to earn a PhD degree, which stands for Doctor of Philosophy.

A PhD is created from knowledge acquired from:

1. Coursework:

A PhD program consists of academic courses that are usually small in size and challenging in content. Most PhD courses consist of a high amount and level of reading and writing per week. These courses will help prepare you for your dissertation as they will teach research methodology.

2. Research:

For your dissertation, it is likely that you will have the choice between performing your own research on a subject , or expanding on existing research. Likely, you will complete a mixture of the two. For those in the hard sciences, you will perform research in a lab. For those in humanities and social sciences, research may mean gathering data from surveys or existing research.

3. Analysis:

Once you have collected the data you need to prove your point, you will have to analyze and interpret the information. PhD programs will prepare you for how to conduct analysis, as well as for how to position your research into the existing body of work on the subject matter.

4. Support:

The process of writing and completing a dissertation is bigger than the work itself. It can lead to research positions within the university or outside companies. It may mean that you will teach and share your findings with current undergraduates, or even be published in academic journals. How far you plan to take your dissertation is your choice to make and will require the relevant effort to accomplish your goals.

Moving from Student to Scholar

In essence, a dissertation is what moves a doctoral student into becoming a scholar. Their research may be published, shared, and used as educational material moving forwards.

Thesis vs. Dissertation

Basic differences.

Grad students may conflate the differences between a thesis and a dissertation.

Simply put, a thesis is what you write to complete a master’s degree. It summarizes existing research and signifies that you understand the subject matter deeply.

On the other hand, a dissertation is the culmination of a doctoral program. It will likely require your own research and it can contribute an entirely new idea into your field.

Structural Differences

When it comes to the structure, a thesis and dissertation are also different. A thesis is like the research papers you complete during undergraduate studies. A thesis displays your ability to think critically and analyze information. It’s less based on research that you’ve completed yourself and more about interpreting and analyzing existing material. They are generally around 100 pages in length.

A dissertation is generally two to three times longer compared to a thesis. This is because the bulk of the information is garnered from research you’ve performed yourself. Also, if you are providing something new in your field, it means that existing information is lacking. That’s why you’ll have to provide a lot of data and research to back up your claims.

Your Guide: Structuring a Dissertation

Dissertation length.

The length of a dissertation varies between study level and country. At an undergraduate level, this is more likely referred to as a research paper, which is 10,000 to 12,000 words on average. At a master’s level, the word count may be 15,000 to 25,000, and it will likely be in the form of a thesis. For those completing their PhD, then the dissertation could be 50,000 words or more.

Photo by Louis Reed on Unsplash

Format of the dissertation.

Here are the items you must include in a dissertation. While the format may slightly vary, here’s a look at one way to format your dissertation:

1. Title page:

This is the first page which includes: title, your name, department, degree program, institution, and submission date. Your program may specify exactly how and what they want you to include on the title page.

2. Acknowledgements:

This is optional, but it is where you can express your gratitude to those who have helped you complete your dissertation (professors, research partners, etc.).

3. Abstract:

The abstract is about 150-300 words and summarizes what your research is about. You state the main topic, the methods used, the main results, and your conclusion.

4. Table of Contents

Here, you list the chapter titles and pages to serve as a wayfinding tool for your readers.

5. List of Figures and Tables:

This is like the table of contents, but for graphs and figures.

6. List of Abbreviations:

If you’ve constantly abbreviated words in your content, define them in a list at the beginning.

7. Glossary:

In highly specialized work, it’s likely that you’ve used words that most people may not understand, so a glossary is where you define these terms.

8. Introduction:

Your introduction sets up the topic, purpose, and relevance. It’s where readers will understand what they expect to gain from your dissertation.

9. Literature Review / Theoretical Framework:

Based on the research you performed to create your own dissertation, you’ll want to summarize and address the gaps in what you researched.

10. Methodology

This is where you define how you conducted your research. It offers credibility for you as a source of information. You should give all the details as to how you’ve conducted your research, including: where and when research took place, how it was conducted, any obstacles you faced, and how you justified your findings.

11. Results:

This is where you share the results that have helped contribute to your findings.

12. Discussion:

In the discussion section, you explain what these findings mean to your research question. Were they in line with your expectations or did something jump out as surprising? You may also want to recommend ways to move forward in researching and addressing the subject matter.

13. Conclusion:

A conclusion ties it all together and summarizes the answer to the research question and leaves your reader clearly understanding your main argument.

14. Reference List:

This is the equivalent to a works cited or bibliography page, which documents all the sources you used to create your dissertation.

15. Appendices:

If you have any information that was ancillary to creating the dissertation, but doesn’t directly fit into its chapters, then you can add it in the appendix.

Drafting and Rewriting

As with any paper, especially one of this size and importance, the writing requires a process. It may begin with outlines and drafts, and even a few rewrites. It’s important to proofread your dissertation for both grammatical mistakes, but also to ensure it can be clearly understood.

It’s always useful to read your writing out loud to catch mistakes. Also, if you have people who you trust to read it over — like a peer, family member, mentor, or professor — it’s very helpful to get a second eye on your work.

How is it Different from an Essay?

There are a few main differences between a dissertation and an essay. For starters, an essay is relatively short in comparison to a dissertation, which includes your own body of research and work. Not only is an essay shorter, but you are also likely given the topic matter of an essay. When it comes to a dissertation, you have the freedom to construct your own argument, conduct your own research, and then prove your findings.

Types of Dissertations

You can choose what type of dissertation you complete. Often, this depends on the subject and doctoral degree, but the two main types are:

This relies on conducting your own research.

Non-empirical:

This relies on studying existing research to support your argument.

Photo by freddie marriage on Unsplash

More things you should know.

A dissertation is certainly no easy feat. Here’s a few more things to remember before you get started writing your own:

1. Independent by Nature:

The process of completing a dissertation is self-directed, and therefore can feel overwhelming. However, if you approach it like the new experience that it is with an open-mind and willingness to learn, you will make it through!

2. Seek Support:

There are countless people around to offer support. From professors to peers, you can always ask for help throughout the process.

3. Writing Skills:

The process of writing a dissertation will further hone your writing skills which will follow you throughout your life. These skills are highly transferable on the job, from having the ability to communicate to also developing analytical and critical thinking skills.

4. Time Management:

You can work backwards from the culmination of your program to break down this gargantuan task into smaller pieces. That way, you can manage your time to chip away at the task throughout the length of the program.

5. Topic Flexibility:

It’s okay to change subject matters and rethink the point of your dissertation. Just try as much as possible to do this early in the process so you don’t waste too much time and energy.

The Wrap Up

A dissertation marks the completion of your doctoral program and moves you from being a student to being a scholar. While the process is long and requires a lot of effort and energy, you have the power to lend an entirely new research and findings into your field of expertise.

As always, when in the thick of things, remember why you started. Completing both your dissertation and PhD is a commendable accomplishment.

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

Advertisement

Being highly prolific in academic science: characteristics of individuals and their departments

- Open access

- Published: 24 August 2020

- Volume 81 , pages 1237–1255, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mary Frank Fox 1 &

- Irina Nikivincze 1

7691 Accesses

28 Citations

20 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The prolific (exceptionally high producers of scholarly publications) are strategic to the study of academic science. The highly prolific have been drivers of research activity and impact and are a window into the stratification that exists. For these reasons, we address key characteristics associated with being highly prolific. Doing this, we take a social-organizational approach and use distinctive survey data on both social characteristics of scientists and features of their departments, reported by US faculty in computer science, engineering, and sciences within eight US research universities. The findings point to a telling constellation of hierarchical advantages: rank, collaborative span, and favorable work climate. Notably, once we take rank into account, gender is not associated with being prolific. These findings have implications for understandings of being prolific, systems of stratification, and practices and policies in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

High research productivity in vertically undifferentiated higher education systems: who are the top performers, how long do top scientists maintain their stardom an analysis by region, gender and discipline: evidence from italy.

The European research elite: a cross-national study of highly productive academics in 11 countries

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The highly prolific are often considered standard-bearers of productivity. At the same time, their performance is baffling and the gist of speculation (and even suspicion) as to factors associated with it (Wager et al. 2015 ). Exceptionally high publication has been documented for close to a century. Yet few, including the prolific themselves, are able to explain how it occurs (Wolpert and Richards 2007 ) and the performance gets “mystified.” The issue here is not one of simply publishing, but rather being highly prolific in academic science. We use “highly prolific” to refer to a group (15.6%) who are in the right tail of the distribution of publication productivity (20 or more articles published/accepted in the prior 3 years). The rationale for this threshold, and the advantages of a 3-year period, appear in the “Method” section.

Academic sciences are a strategic case for the study of exceptional performance in higher education. First, in academic sciences, refereed articles are accepted widely as a measure of productivity. Social sciences and humanities are important in the study of higher education, but their metrics of performance are more variable (Braxton and Del Favero 2002 ). Second and related, in academic sciences, consensus is relatively high about the value of research performance (Shwed and Bearman 2010 ). Third, scientific fields have been influential in the shaping of graduate education, research specialization, external funding, and the decentralization of departments (Montgomery 1994 ). At the same time, findings about academic sciences may not necessarily generalize to fields, broadly.

Why focus on being prolific

We focus on being highly prolific for two fundamental reasons. First, the highly prolific account disproportionately for research activity. A recent study of 11 European nations showed that the highly prolific (upper 10%) accounted for 50% of publications; and without this group, the output of the given nations would be reduced significantly (Kwiek 2016 ). Another study of the most prolific (representing less than 1% of 15.2 million in the Scopus database) showed that the prolific accounted for 41.7% of papers published (Ioannidis et al. 2014 ).

The prolific are consequential also because they influence research by being “prescient,” and sometimes “disruptive.” An analysis of 8.86 million authors indicates that the highly prolific have few papers that are isolates, that is, within problem areas that fail to survive into a second year beyond publication; a lower than expected proportion in dying/receding areas; and a higher than expected proportion in areas that challenge the status quo (Klavans and Boyack 2011 ).

The prolific also garner the bulk of citations. In laser science technology, the prolific produce 25% of total articles, and on a per-paper basis, their articles have higher impact than those of the less prolific (Garg and Padhi 2000 ). Likewise, in environmental science and ecology, the highly cited are also prolific (Parker et al. 2013 ). This also occurs among Swedish authors of Web of Science publications (van den Besselaar and Sandstrom 2015 ). Thus, the prolific warrant our attention because they have been “drivers” of research activity and impact.

Second and related, the highly prolific are a window into stratified structures. Inequality is a persistent and pervasive feature of higher education (Taylor and Cantwell 2019 ). The factors associated with being highly prolific provide a view into hierarchies of people and groups. This is because the hierarchies are based partly on exceptional performance (Parker et al. 2010 ; Prpić 1996 ; van den Besselaar and Sandstrom 2015 ). The prolific, in turn, are characterized as “stars,” “eminent,” and “elite” (Klavans and Boyack 2011 ; Kwiek 2016 , 2018 ) within higher education systems that are strongly “status-seeking” in missions and motives (Taylor and Cantwell 2019 ). Understanding what predicts being prolific then gives insight into structures of stratification in which the prolific are a distinctive group (Kwiek 2019 , 27). Thus, the study of being prolific is revealing beyond the study of publication productivity, more broadly; and it provides insights into higher education.

To some extent, positive characterization of the prolific is contested, especially when it comes to the performance as a basis for resources distributed (Kwiek 2016 ). Stratification provides benchmarks for performance (Collins 2019 ); and it may also fragment and underserve groups of people (Lincoln et al. 2012 ). In either case (beneficial or not), the prolific are a special segment that can drive (and reflect) systems of rewards, honors, and accolades (Marginson 2014 ), bearing widely on academic lives. Thus, being prolific is a sensitive, as well as revealing, topic. This heightens the rationale for our inquiry.

Previous research: extent and limitations

Studies have addressed publication productivity, broadly, and point to individual characteristics, departmental and institutional features, and feedback processes of cumulative advantages and reinforcement, in explaining the number of publications produced (Fox 1985 ; Kwiek 2019 ; Ramsden 1994 ). These studies address the importance of characteristics including gender (Xie and Shauman 2003 ), research orientation (Cummings and Finkelstein 2012 ), collaborative practices (Lee and Bozeman 2005 ), and multiple projects undertaken, simultaneously (Fox and Mohapatra 2007 ). Features of work settings, such as prestige of institution (Long and Fox 1995 ), departmental climate (Smeby and Try 2005 ), and performance of departmental colleagues (Braxton 1983 ), relate to publication productivity. Feedback processes emphasize the influence of earlier success for continued research through accumulation of advantages (review in DiPrete and Eirich, 2006 ). A variation of this, termed “Matthew effect” (Merton 1968 ), points to greater recognition accruing to those with higher compared with lower repute that occurs especially in collaboration and independent multiple discoveries.

Few studies focus on being prolific—despite the importance of this topic. Those studies that do address being prolific rely predominately on bibliometric sources. Bibliometric studies have advantages of large numbers of cases from Scopus or Web of Science databases and enrich understandings. They point to the role of gender, institutional type, number of collaborators, and researchers’ national locations (e.g., US, UK, Israel) (see Abramo et al. 2009 ; Bosquet and Combes 2013 ; Garg and Padhi 2000 ; Parker et al. 2010 ).

At the same time, the bibliometric approaches do not permit analysis of work settings (resources, work climates) and characteristics such as work practices. Survey methods make it possible to analyze these variables. In doing so, they complement bibliometric inquiries. To date, however, survey approaches to being prolific are limited to two notable studies of European scientists. These show the prolific as older, with high rank, and international collaborations and orientations (Kwiek 2016 , 2018 ; Prpić 1996 ).

Present study: questions, perspective, and focal constructs and variables

We address the following questions about the prolific in higher education. How does exceptional (prolific) productivity relate to academic scientists’ individual characteristics (gender, rank, work practices) and their reported features of departments (resources, climates)? Why do the patterns matter?

We pursue these questions with a social-organizational perspective. This perspective combines views of individual characteristics and organizational conditions, and the links within and between characteristics and conditions, in understanding exceptional performance. The perspective is aligned with academic sciences because scientific research takes place “on site” within departments; it relies on cooperation of others and is tied with collaborative patterns. The work is fundamentally social and organizational (Fox and Mohapatra 2007 ; Lee and Bozeman 2005 ; Zhang 2010 ). Key issues are then: Which social characteristics and departmental conditions are associated with being prolific? How do these characteristics and conditions operate, either co-exiting as predictors, or mediating the effects of another? What are the implications of the results for understanding higher education? The perspective is identified as one needed—yet often missing—in the study of research activity (Antonelli et al. 2011 ). The perspective is also potentially consequential for understanding topics related (but not identical) to being prolific, such as exceptional creativity (Amabile et al. 1996 ) and innovation (Glynn 1996 ) and the organization of academic labor (Carayol and Matt 2004 ).

We use sets of constructs (broad concepts) and variables (related measures) that reflect this perspective. As an individual characteristic, gender is key because a range of studies point to the lower productivity of women compared to men (see Ceci et al. 2014 )—with potential implications for gender disparity in exceptional performance (Fox et al. 2017 ). Academic rank is important because those who publish extensively achieve higher rank and those with high rank can accrue positions and networks that enable being prolific (Kwiek 2016 ; Prpić 1996 ; Teodorescu 2000 ). Work practices reflect ways of conducting work and are associated with exceptional productivity (Root-Berstein et al. 1995 ).

Of these practices, collaboration is important because, increasingly, scientific results are the product of teamwork and the pooling of knowledge and skills (Wuchty et al. 2007 ). Quality and quantity of collaboration support publication productivity (Lee and Bozeman 2005 ), and collaboration occurs more extensively among the eminent (Kwiek 2016 ). Here, our focus is on span of collaboration as a variable, in a way not previously analyzed in relationship to being prolific. Frequency of discussion about research is also important because it can help generate and sustain research activity, by providing room for speculation and sharing successes and failures (see Campbell 2003 ; Katz and Martin 1997 ).

From a social-organizational perspective, reported features of departmental settings are key constructs. They are important across fields, and especially so in academic science. This is because scientific research revolves strongly on cooperation with others and costly resources—so that settings can be highly salient (Fox and Mohapatra 2007 ). Quality of faculty and students (human resources) have the potential to shape and reflect research performance (Baird 1986 ; Braxton 1983 ). So do material resources of equipment and space. Equipment is essential to scientific discovery, even in some theoretical areas. Likewise, scientific research entails space, sometimes with special conditions such as “clean” areas or exhaust systems (Stephan 2012 ). Interestingly, Bland and Ruffin ( 1992 ) report that the perception of resources available (compared to measurable distribution of them) correlates with productivity.

Work climates are characterizations of settings—meanings that people attach to an organization and its values, practices, and goals (Patterson et al. 2005 ). Operationally, work climates are ways that people appraise their environments (Patterson et al. 2005 ) along dimensions that encompass the atmosphere or “personality” of a unit. Departmental work climates are consequential because they can activate interests, convey standards, and stimulate or depress performance (Fox and Mohapatra 2007 ; Louis et al. 2007 ; Torrisi 2013 ). A key study of the “state of research on work climates” points to renewed interest in work climate and the need for more definitive studies of climate and performance (Kuenzi and Schminke 2009 ). Accordingly, the analysis here of work climate and being prolific is unusual (or unique).

Our “Introduction” section has provided the rationale for studying the prolific; the extent and limitations of previous research; and the questions, perspective, and focal constructs and variables of this study. The following sections address the “Method” and “Findings”. The “Discussion and conclusions” section summarizes the contributions of the study and addresses broader implications of the findings.

The data are collected in surveys Footnote 1 of tenured and tenure-track faculty in departmental fields of computer science, engineering, and six fields of sciences (biology/life sciences, chemistry/microchemistry, earth/atmospheric, mathematics, physics, psychology Footnote 2 ). These fields encompass the range of classifications of the US National Science Foundation. The faculty members surveyed are in eight research universities identified by a strong baseline university as institutional peers in prestigious, national standing in scientific and technological fields. Footnote 3 These universities are within the Research I and Doctoral-Research Extensive categories of the Carnegie Classifications at the time of the survey. They are cross-regional within the USA (one southeast, two northeast, one northcentral, two midwest, one southeast, and two pacific west) and encompass public (four) and private (four) institutions. Research universities constitute an important grouping because they train doctoral students, confer numbers of degrees, receive federal grants, and contribute to research. They also set standards for rewards in other types of institutions (Fairweather 2005 ).

The survey is distinguished by inclusion of the population of women, except for sampling in life sciences and psychology ( n = 434), enabling analysis by gender, and a stratified, random (probability) sample of men by field ( n = 527). We accomplished this sample by (1) canvassing completely the websites of departmental fields within these eight institutions; (2) identifying the total population of tenured and tenure-track faculty; and (3) taking stratified random samples by field from known and specified populations (see Appendix —supplementary materials).

The resulting number of respondents to the survey is 327 men and 280 women. The overall response rate is 65% for both women and men respondents (a response rate that removes 24 ineligible cases from the base because of moves, retirements, and/or being deceased). This response reflects the use of customized letters and follow-ups to non-respondents, based on Dillman et al. ( 2014 ) protocols. The response here exceeds the rates of 50% (or less) most commonly reported in surveys of academics and scientists.

Our survey data are revealing but do not permit links to bibliometric (Web of Science, Scopus) data, the weighting of articles by numbers of authors, and inclusion of citations. This is because the identity (names) of survey respondents is protected by the given approval of the institutional review board, and thus, the means are unavailable for “tracing” respondents to other sources. Despite this, our method enabled collection of a range of important indicators that are absent from most bibliometric studies.

Measures of variables

Dependent variable.

The dependent variable is prolific (or not) based on self-reported number of articles published or accepted for publication in refereed journals in the prior 3 years and, for computer scientists, the number of refereed proceedings as well. Information on numbers of coauthors is not available. Footnote 4 The inclusion of refereed proceedings for computer scientists is in keeping with the Computing Research Association’s ( 1999 ) “best practices” that, in computing, proceedings are rigorously reviewed and a standard means of publication, along with refereed articles.

The measures of publications take into account: (1) types of publications, (2) time lags, (3) period of time, and (4) self-reporting of data. First, the survey asks respondents to list separately the number of articles published and those fully accepted in refereed journals and in conference proceedings—as well as counts of other types of publications. Collecting counts in other categories helps to reduce or eliminate respondents’ mis-categorizing them as “refereed articles” (or proceedings) and thus improves the validity of counts in the “core” publications. Second, the inclusion of the number of articles (and proceedings) published and separately, the number fully accepted for publication, addresses the time lags that occur between submission, acceptance, and publication. Third, specifying a prior 3-year period controls for the effects of seniority (available span of time) for publishing; and publications in a recent period may be analyzed in relationship to current departmental features reported (while a long span could not). Further, the measure goes beyond articles simply published in a 3-year period and includes those fully accepted, as indicated, and thus helps address lags in times to publication. Fourth, self-reported counts correlate highly with those listed in independent sources (Ehrenberg et al. 2009 ).

Definitions of the prolific commonly reflect a “power law of distribution” (Newman 2005 ), namely, that the bulk of counts occurs for a small number of cases; that a long-right tail of the distribution exists; and, classically, that about 80% of counts owe to 20% of the cases. Thus, to begin, we examined the distributions of counts of publication productivity for all respondents ( n = 607) and for those with cases complete ( n = 493) for our variables. These two distributions were comparable in the concentrations of publications in a small group; and in the percentages of respondents by gender, rank, and departmental field (Table 1 ). Further, results of Little’s MCAR test were not significant ( p = .155), indicating that data were missing completely at random.

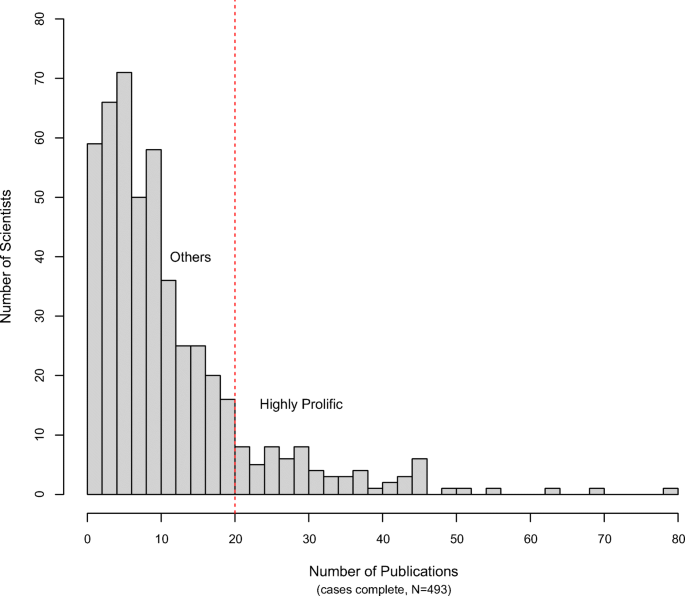

The distribution of publications for cases complete (Fig. 1 ) has a range of 0 to 80, skewness of 2.2, a mean of 11.6, and a median of 9. Notably, this distribution shows a flattening of counts at 20 or more articles in the 3-year period, representing 15.6% of these academic scientists. This cut-off point provides a fit to the resulting models here. Using points for prolific of (1) the upper 21% and (2) the upper 15% for each of the three major fields did not change results. Further, no significant differences appear in values of the independent variables for the upper 5% compared with the upper 15%; and an upper 5% is restricted because it contains only 25 respondents. The proportion of respondents (15.6%) who constitute the threshold for prolific here is within the range of proportions (10%–25%) identified as prolific in other groups over time (see Garg and Padhi 2000 ; Kwiek 2016 ).

Frequency of publication counts for scientists in prior 3-year period

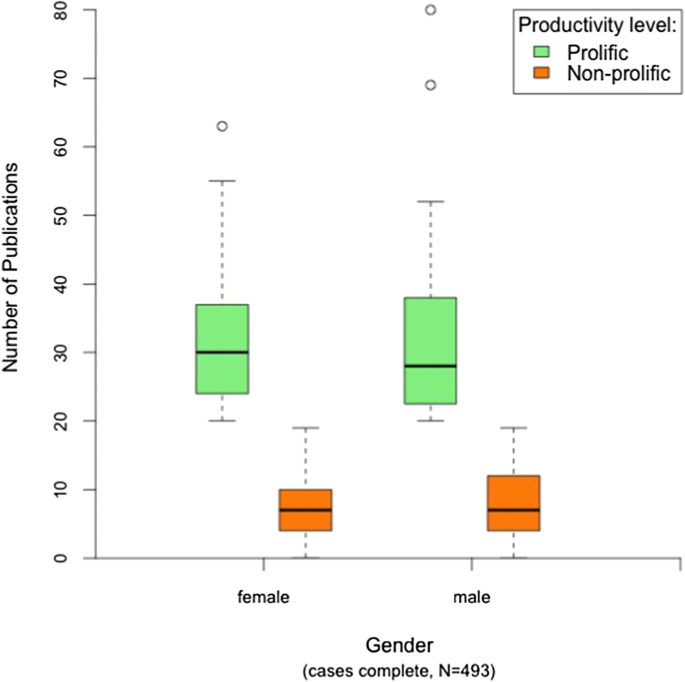

A potential question is whether the men and women differ in the distribution of actual counts within the categories of prolific and non-prolific. A box-plot (Fig. 2 ) shows similar mean and median counts for prolific and non-prolific women and men. This indicates that the cut-off points for prolific/non-prolific are not camouflaging actual counts among the women compared with men.

Box-plots of publication counts for prolific and non-prolific scientists, by gender. Box-plots graphically depict five publication statistics: the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile (see the boxes), the smallest and the largest extremes (the whiskers), and the outliers (circles)

Independent variables

The independent variables encompass (1) characteristics of individuals (gender, rank, and reported work practices) and (2) features of their departments (human and material resources, departmental climates).

Gender is coded as male (female as comparison). Ranks are full professor and associate professor (assistant professor as comparison). Work practices are span of collaboration and frequency of speaking about research. Collaborative span is based on reported collaboration in research proposals or publications (yes/no) in the past 3 years with faculty (a) within the home unit; (b) within the home university, but outside of home unit; and (c) in other institutions. Collaboration at each of these levels (a–c) constitutes a value of 1, so that the resulting measure can extend from 0 to 3. The question about frequency of speaking with faculty in home unit about research refers to speaking about “research projects and research interests.” This is coded as a dummy variable of speaking daily or weekly (compared with less than weekly).

For human resources, we considered reported quality (poor to excellent) of (a) faculty, (b) graduate students, and (c) undergraduate majors in the home unit. The quality of faculty and undergraduates had virtually no association with being prolific, while the quality of graduate students did (dummy, τb = .139, p < .001; scaled, τb = .149, p < .001). In keeping with the importance of graduate students for research in academic science, this measure was the stronger of the three variables (especially in its scaled form); and including this meets the need to limit the number of variables (in relationship to cases).

Quality of material resources takes the form of two binary variables of “excellent” (compared with “good,” “fair,” or “poor”) in reported quality of (a) space and (b) equipment. Conceptually, the variables go beyond sufficiency to measure excellence in space and equipment (related potentially to being prolific). Empirically, the recoding permits inclusion of both variables without the level of collinearity ( r = .54, p < .001) that exists for the variables in scaled form.

We measure work climate with questionnaire items asking respondents to rank their home unit along eight, scaled (5-point scale), bipolar dimensions of (1) formal-informal, (2) boring-exciting, (3) unhelpful-helpful, (4) uncreative-creative, (5) unfair-fair, (6) competitive-noncompetitive, (7) stressful-unstressful, and (8) noninclusive-inclusive.

We used exploratory factor analysis to detect an underlying structure among these (1–8). The interest was in communality (common variance) among the items. Thus, we used principal axis, rather than maximum likelihood, factoring. The results of oblique (oblimin) rotation were similar to orthogonal, and we chose the orthogonal (varimax) to more clearly separate the factors. One item (formal-informal) did not load on any factors (loadings below 0.5) and was removed.

The factor analysis identified three constructs of departmental climates: (1) “stimulating” (creative, exciting); (2) “collegial” (fair, helpful, inclusive); and (3) “competitive” (stressful, competitive). The correlations among the seven items and factor loadings appear in Table 2 . After identifying the factor structure, we created scores (unweighted scales) by adding the items with factor loadings of 0.55 or greater. Reliability tests (Chronbach’s alpha) produced values of 0.84 for stimulating, 0.74 for collegial, and 0.68 for competitive climates. The alpha value for competitive climate was lower than the others; and at the same time, the values for each climate are sufficient for inclusion.

Sensitivity tests

We considered other variables that do not appear in the final models. These variables did not differentiate faculty in research universities; did not relate closely to the perspective; introduced multicollinearity; and/or extended the number of variables beyond those appropriate for the number of cases. Footnote 5 Specifically, “great interest” in research and in teaching did not differentiate prolific and non-prolific faculty, in part, because of limited variation in these. This is also the case for being a principal investigator on a grant within the past 3 years and for the time between bachelor’s and doctoral degrees. Age and age-squared were co-linear with academic rank, and in the presence of rank, did not predict.

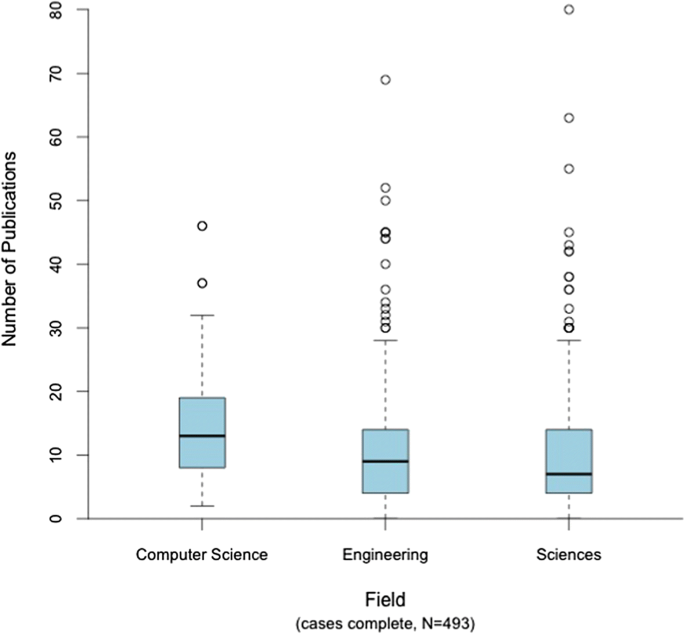

We explored the impact of fields (Table 3 ). The box-plots of publication counts in the three broad fields reveal greater similarity among engineering and sciences compared with computer science (Fig. 3 ). Engineering and sciences have faculty with zero publications and distant outliers. All faculty in computing published at least once in the last 3 years.

Box-plots of publication counts, by field. Box-plots graphically depict five publication statistics: the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile (see the boxes), the smallest and the largest extremes (the whiskers), and the outliers (circles)

We could not use each field of science because some were small Footnote 6 ; had few faculty members; and were sensitive to zero cell count problem, that is, to the invariance of the dependent and independent variables (Menard 2010 ). However, we analyzed fields or clusters of fields as predictors of the actual publication counts (a continuous variable rather than being prolific or not) in a negative binomial (and in a Poisson) regression for overdispersed distributions. The results (not displayed) were consistent with those of logistic regression and average field output. They show that, compared with being in engineering, locations in computer science, chemistry, or physics were associated with statistically significant increases in publication counts; being in mathematics decreased the count. Field was a good predictor of counts of publications, but not a good predictor of being highly prolific.

Finally, we assessed the potential interaction of gender and rank with being prolific. First, we addressed the interaction in a logistic regression. The product term was not statistically significant and could not be interpreted. A second diagnostic, Jaccard’s ( 2001 ) method of testing two-way interactions with a moderator (gender), showed the odds of being prolific as a function of gender and rank. The odds ratios for each rank were equal, confirming the absence of interaction of rank and gender. However, further tests showed that rank mediated the relationship between gender and being prolific; and the “Findings” and “Discussion and conclusions” sections address this.

Means of analysis

We use three multi-stage logistic regression models to assess characteristics associated with being prolific. These models express the relationship between being prolific (compared with not) and (1) the individual characteristics of gender and academic rank; (2) the preceding (model 1) with addition of work practices; and (3) the preceding (model 2) with addition of reported departmental features. In the analysis of extremes (as is the case of prolific), logistic regression is advantageous over a linear probability because it can handle extremes, and a linear probability model is likely to yield out-of-bound predicted probabilities (Menard 2010 ).

The logistic regressions present the predictive value (log odds) that an independent variable has for being prolific. The coefficients may be interpreted as a change in the log odds of a response per unit of change in the independent variable. The multi-stage models allow us to assess the independent variables in the absence and presence of other variables. Alterations in values and significance can point to covariation between the variables in the earlier model with those in the subsequent model(s).

Cross-sectional data and logistic regression allow us to explore patterns of relationships but do not establish causal order, as addressed in the “Discussion and conclusions” section. With these caveats, we use the term “predictor” for independent variables because this term is commonly used and understood in logistic regression.

The findings depict the results of the sequence of the three logistic regression models with predictors of being prolific (Table 4 ). This section presents the central results, and further implications appear in the next section.

The first logistic model includes gender and academic ranks. Higher ranks predict being prolific. Having a rank of full professor (compared with assistant professor) strongly and positively predicts being prolific (log odds = 3.254, p < .01). Having a rank of associate professor also predicts being prolific (log odds = 2.672, p < .05); however, this rank is not as strong a predictor as full professor. In the presence of rank, male gender does not significantly predict being prolific, although, by itself (analyses not shown), gender does. This suggests covariation between gender and rank (but not interaction of gender and rank, addressed in the “Method” section). Notable implications appear in the following section.

In the second logistic model, added are the work practices of speaking daily or weekly about research with faculty in the home unit and the span of collaboration in research proposals and papers within the prior 3 years. Speaking frequently about research is a work practice that encompasses elements of exchange that go beyond formal collaboration in proposals and publications. However, this is not associated with being prolific. Span of collaboration is a predictor (log odds = 0.535, p < .01). A wider span of collaboration (with faculty in home unit, on campus but not in home unit, and outside of the home institution), compared with a more narrow span of collaboration (or none at all), is associated with being prolific. This points to the prolific as strongly collaborative researchers with those both near (those in the home department and on campus) and far (those outside of their institution). We discuss the complexities of collaborative span in the following section.

In this second model, academic ranks remain strong and significant predictors. The log odds of holding a rank of full professor or associate professor barely reduce with the addition of work practices in the second, compared with the first, model. This indicates that as positive predictors, ranks are not simply a function of collaborative span associated with academic scientists’ higher positions. Rather, both rank and collaborative span coexist as predictors. Gender remains non-significant in the second, as well as the first, model.

In the third model, added are faculty members’ characterizations (perceptions) of their departments in levels of human and material resources and work climates. Among these, the significant predictor of prolific is being in a department characterized as “stimulating” (log odds = 0.281, p < .01). Location in a department characterized as “collegial” is not a significant predictor (log odds = −0.062, p = .302); nor is location in a strongly “competitive” setting (log odds = −.006, p = .930). In the following section, we discuss the prospect that those who are unusually productive may regard their departments as stimulating and/or may create micro-environments within departments that are stimulating.

The human resource of quality of graduate students does not predict being prolific (log odds = 0.214, p = .444) in this model. Neither do material resources of space (log odds = −.295, p = .346) or equipment (log odds = .051, p = .875). Further, the characterizations of departments do not alter notably the levels and significance of the predictors in the earlier models, namely, academic ranks and collaborative span. In this third, final model, being a full professor continues to be a strong and significant predictor (log odds = 3.324, p < .01). Being an associate professor is less strong than being full professor, but still a significant predictor (log odds = 2.626, p < .05). Likewise, a span of collaboration remains a strong predictor in this third model (log odds = .55, p < .05). Thus, the academic scientists’ rank and collaboration are predictors that owe little to the characterizations of the departments in which they are located. Overall, outside of the stimulating climate, characterizations of departments are not as strong as rank and collaborative span in capturing prolific productivity among these academic scientists.

Discussion and conclusions

Being prolific is a distinction that underlies depictions of “superstar” (Klavans and Boyack 2011 ), “eminent” (Kwiek 2016 ), and “elite” scientists (Parker et al. 2013 ). In this sense, the prolific constitute a basis of social stratification in higher education that bears on academic lives. Yet, the features associated with being prolific have been only rarely investigated with reliable survey data, particularly with key characteristics of individuals and their departments, and links between them, which reflect a social-organizational perspective. Thus, we take up the widely expressed and long-standing “need to know more” about the highly prolific as a distinctive and revealing group in higher education (Garrison et al. 1992 ; Kwiek 2016 ; Parker et al. 2010 ; Prpić 1996 ).

We do this using survey data with a strong (65%) response rate among academic scientists in eight US research universities. Scientists in these settings are an important group because their institutions define themselves through research (including external funding and graduate degrees awarded). However, only 15.6% of prolific academic scientists, by our measure, account for 44% of all publications in this study. In the prior section, we identified stable features (across the models) associated with being prolific. Now, we discuss the results in relationship to the social-organizational perspective that frames our study. We consider noteworthy findings and their broader implications and also address limitations of the data and areas for continuing inquiry.

Results from our sequential models (previous section) point to ways that gender and rank, work practices, and reported features of departmental environments operate in predicting being prolific. First, the initial model contains rank and gender because interest persists in gender and research performance; and rank is a fundamental feature of academic positions. As a predictor of being prolific, gender bears on understandings of other disparities (recognition, rewards) among male and female scientists that, in turn, relate to performance (Fox et al. 2017 ; Xie and Shauman 2003 ). Rank (especially full professor) is associated with being prolific, and in the presence of rank, gender is not. Moreover, rank remains a stable predictor across models. The implications are notable.

The findings here indicate covariation of gender and rank in relationship to being prolific. This points to rank as key to understandings of gender disparities (Fox 2020 ; Rørstad and Aksnes 2015 ; Xie and Shauman 2003 ). This does not mean that access to academic rank is equitable; evidence exists to the contrary (Fox 2020 ; Xie & Shaumann, 2003 ). Rather, we find that rank mediates the relationship between gender and being prolific. This indicates that gender does not directly influence being prolific here; it does so by means of rank (the mediator). To put it another way: among the women here who have high academic rank, the odds of being prolific are not significantly lower than those of men. From a social-organizational perspective, this is a notable social link: rank is a conduit in the relationship between gender and being prolific.

More broadly, being prolific is a senior professors’ game, contrary to some popular lore about this. Our measure of prolific is based on publication in the prior 3-year period (not across the career). This means, in turn, that the relationship between rank and being prolific is a complex issue and not simply a matter of longer time to accrue publications for those at higher ranks. Higher rank potentially confers (and reflects) advantages of research experience, lead roles on teams, and integration into scientific communities (Rørstad and Aksnes 2015 ). Further, ranks are not simply a function of collaborative span or perceptions about work climates. As emphasized, the coefficients for rank do not reduce in models with inclusion of these variables. In addition, rank remains strongly associated with being prolific, controlling for fields (Appendix Table 4 —supplementary materials).

Funding agencies may be fueling the salience of rank by requiring that proposals contain preliminary results and, in turn, favoring research programs of established scientists (Stephan 2012 ). Relatedly, increased use of H-index (based on the number of papers and their citations) favors established scientists (Lawrence 2007 ) and may also support the salience of rank. Fu0rther, gendered processes of evaluation can contribute to the importance of rank as a mediator of gender in being prolific.

Second, the practice of frequency of speaking with departmental faculty about research, introduced in the second model, represents informal exchange. This is not equivalent to formal collaboration, measured here as coauthoring proposals and publications. From a social-organizational perspective, speaking daily or weekly about research may help generate and sustain research activity (Campbell 2003 ; Katz and Martin 1997 ). However, compared with actual collaboration in proposals and publications, speaking frequently is not significant in predicting being prolific. This, in turn, may be a potential issue for types of interaction that departments seek to encourage.

Third, we measure span of collaborators in a revealing way: a range of having (faculty) collaborators in home department, in units within the university but outside home department, and in other universities. We find that a wider span is associated with being prolific. This reflects teamwork as a mode of scientific production (Wuchty et al. 2007 ) with benefits derived. Footnote 7 In broader implications, however, collaboration may also come with tensions and costs, including time, energy, and interpersonal struggles (see Bikard et al. 2015 ). As a part of this, Bikard et al. ( 2015 ) focus on trade-offs between collaboration and credit for research, and the potential for a junior ranked researcher’s credit in publication to be reduced as a member of a collaborative team. Bozeman and Youtie ( 2017 ) also point to challenges that exist in assigning credit for teams of authors and to vulnerabilities for junior colleagues. A reasonable consideration is that the prolific may lose less in credit/recognition when collaborating than do the non-prolific. Thus, for the prolific, collaborative span may be relatively low on drawbacks and high on benefits. This would be consistent with the classic “Matthew effect” of those already advantaged becoming yet more advantaged, especially in cases of collaboration where credit accrues to the more eminent coauthors (Merton 1968 ). Our findings point then to complex social-organizational dimensions of collaboration in “who benefits,” depending on the rank and position of academic scientists.

Fourth, overall, the departmental features do not predict as strongly as the individual, social characteristics, and especially rank. Perceptions about human and material departmental resources are not associated with being prolific. A possible factor here is that the distribution of material resources does not correspond to the distribution of prolific performance. One argument is that decision makers at departmental levels may avoid extremely unequal distributions of resources and suppress incentives for the most productive in the resources distributed (Hicks and Katz 2011 ). Another argument is that the highly prolific in research universities may see themselves as the sources (rather than recipients) for the departments’ resources because of their own grants, awards, and networks. It is likely that, outside of research universities, resources would be stronger predictors of being prolific (at the same time, the proportions of prolific in these settings are unknown). From our perspective, the issue exists of social-organizational dimensions of resources in “who benefits” in being prolific and in which types of institutions.

Fifth, the departmental feature associated with being prolific is being a unit perceived as stimulating. This may occur in a range of ways. Being in a stimulating department may promote and/or sustain being prolific. Alternately, or in parallel, being prolific may foster positive perceptions of, and experiences with, work climate. On balance, this means that the prolific may also be cultivating stimulating environments in their labs, and these, in turn, may constitute their own (“micro-level”) departmental climates. The decentralization of academic science departments into autonomous laboratories, funded and administered by principal investigators (Roth and Sonnert 2011 ), is consistent with this. Work climate is a novel dimension in this study of the prolific and merits continuing investigation.

Thus, we find a constellation of telling hierarchical advantages associated with being prolific: (1) the individual characteristic of academic rank, (2) the work practice of collaborative span, and (3) the departmental condition of a stimulating work climate. By itself, gender predicts being prolific, but in the presence of rank, it does not. It is the case that the data are cross-sectional and the causal relations between the hierarchical advantages and being prolific can operate in a range of directions, as recognized in this article. At the same time, the analyses point to key patterns of association : variables that do and do not predict, variables that co-exist, and variables that mediate in striking ways. The patterns depicted here help to break ground in understanding being prolific among US academic science from a social-organizational perspective: they identify characteristics of individuals and their settings, and links between them, which predict exceptional performance. Understanding these informs a long-standing question, posed in opening of our article: how exceptional performance occurs among academic scientists.

What, then, are the implications of the findings here for educational and science policy makers dealing with broader aggregates (beyond individuals in departments)? Policy makers’ decisions include whether and how to distribute resources to small groups with established impact and/or whether and how to expand such groups. When seeking to use resources to expand performance, policy makers frequently look to presumed powers of collaboration. Optimism abounds in the efficacy of large, collaborative groups for enhancing innovation and performance. This is evidenced in the research award programs and policies at the highest national levels (as in the US National Institutes of Health and the National Science Board) (Bikard et al. 2015 ; Bozeman and Youtie 2017 ). The optimism, however, is infrequently informed, or tempered, by the costs, as well as benefits, of collaboration, and by costs that may assumed disproportionately among the less eminent. This means that efforts to distribute research activity and impact more widely are not easily attained and that existing pockets of the prolific are not easily expanded. While we find that collaborative span is associated with being prolific at the individual-level, it may also be that benefits work more advantageously among the already eminent. From our social organizational perspective, the implications for policy are that returns to investments in collaboration do not exist apart from complex considerations of rank, raised here.

Finally, our study informs and promotes continuing inquiry. Understandings of being prolific can be extended by considering academic scientists’ combinations of administrative and research activities (Pelz and Andrews 1976 ), the presence of sustained research funding (Pao 1991 ), and partnerships with industry (Warshaw and Hearn 2014 ). Including rapidly developing fields such as those of biomedicine, would also be valuable, given that the fields are fast moving, well funded, and populated by clusters of prolific authors (Pei and Porter 2011 ). Such social and organizational dimensions will continue to advance understandings of being prolific, systems of stratification, and implications for practices and policies in higher education, presented here.

The surveys were conducted in 2003–2004. Since 2004, universities have experienced increased entrepreneurial activity, global collaboration, and competition for resources. However, these changes have been stronger outside of, compared with inside, the USA (Bloch et al. 2018 ).

The National Science Foundation (National Science Board, 2016 ) categorizes psychology as a distinct scientific field.

The baseline university was surveyed, but not on issues of publication productivity.

At the same time, adjusting for numbers of coauthors does not affect measures of productivity at the individual level (Mairesse and Pezzoni 2015 , 290).

The total number of variables included in models is governed in part by the number of positive/negative events available for analysis (Peduzzi et al. 1996 ).

After removing the smallest academic field of mathematics ( n = 21), regression results show that chemistry/biochemistry is the only field associated with being prolific.

Collaborative span encompasses international collaboration as well. However, this measure is not available here.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C., & Caprasecca, A. (2009). The contribution of star scientists to differences in research productivity. Scientometrics, 81 (3), 136–156.

Google Scholar

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (5), 1154–1183.

Antonelli, C., Franzoni, C., & Geuna, A. (2011). The organization, economics, and policy of scientific research: what we do know and what we don’t know—an agenda for research. Industrial and Corporate Change, 20 (1), 201–213.

Baird, L. L. (1986). What characterizes a productive research department? Research in Higher Education, 25 (3), 211–225.

Bikard, M., Murray, F., & Gans, J. S. (2015). Exploring trade-offs in the organization of scientific work: collaboration and scientific reward. Management Science, 61 (7), 1473–1495.

Bland, C. J., & Ruffin, M. T. (1992). Characteristics of a productive research environment: literature review. Academic Medicine, 67 (6), 385–397.

Bloch, R., Mitterle, A., Paradeise, C., & Peter, T. (2018). Universities and the production of elites . Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bosquet, C., & Combes, P. P. (2013). Are academics who publish more also more cited? Individual determinants of publication and publication records. Scientometrics, 97 (3), 831–857.

Bozeman, B., & Youtie, J. (2017). The strength of numbers: the new science of team science . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Braxton, J. M. (1983). Departmental colleagues and individual faculty publication productivity. The Review of Higher Education, 6 (2), 115–128.

Braxton, J. M., & Del Favero, M. (2002). Evaluating scholarship performance: traditional and emergent assessment templates. New Directions for Institutional Research, 114 , 19–32.

Campbell, R. A. (2003). Preparing the next generation of scientists: the social process of managing students. Social Studies of Science, 33 (6), 897–927.

Carayol, N., & Matt, M. (2004). Does research organization influence academic production? Laboratory level evidence from a large European university. Research Policy, 33 (8), 1081–1102.

Ceci, S. J., Ginther, D. K., Kahn, S., & Williams, W. M. (2014). Women in academic science: a changing landscape. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15 (3), 75–141.

Collins, R. (2019). The credential society: a historical sociology of education and stratification . New York: Columbia University Press.

Computing Research Association. (1999). Best Practices Memo: Evaluating computer scientists and engineers for promotion and tenure. Computing Research News, A-B.

Cummings, W. & Finkelstein, M. (2012) Scholars in the changing American Academy . Springer.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method . John Wiley & Sons.

DiPrete, T. R. & Eirich, G. (2006). Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: a review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annual Review of Sociology, 32 , 271–297.

Ehrenberg, R., Zuckerman, H., Groen, J., & Brucker, S. (2009). Changing the education of scholars: an introduction to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Graduate Education Initiative. In R. Ehrenberg & C. Kuh (Eds.), Doctoral education and the faculty of the future (pp. 15–34). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fairweather, J. S. (2005). Beyond the rhetoric: trends in the relative value of teaching and research in faculty salaries. The Journal of Higher Education, 76 (4), 401–422.

Fox, M. F. (1985). Publication, performance, and reward in science and scholarship. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 1 , 255–282.

Fox M. F. (2020) Gender, science, and academic rank: Key issues and approaches. Quantitative Science Studies, 1 (3), 1001–1006

Fox, M. F., & Mohapatra, S. (2007). Social-organizational characteristics of work and publication productivity among academic scientists in doctoral-granting departments. The Journal of Higher Education, 78 (5), 542–571.

Fox, M. F., Whittington, K. B., & Linkova, M. (2017). Gender, (in) equity, and the scientific workforce. In U. Felt, R. Fouche, C. Miller, & L. Smith-Doerr (Eds.), Handbook of science and technology studies. (pp. 701–731). MIT Press.

Garg, K. C., & Padhi, P. (2000). Scientometrics of prolific and non-prolific authors in laser science and technology. Scientometrics, 49 (3), 359–371.

Garrison, H. H., Herman, S. S., & Lipton, J. A. (1992). Measuring characteristics of scientific research: a comparison of bibliographic and survey data. Scientometrics, 24 (2), 359–370.

Glynn, M. A. (1996). Innovative genius: a framework for relating individual and organizational intelligences to innovation. Academy of Management Review, 21 (4), 1081–1111.

Hicks, D., & Katz, J. S. (2011). Equity and excellence in research funding. Minerva, 49 (2), 137–151.

Ioannidis, J., Boyack, K., & Klavans, R. (2014). Estimates of the continuously publishing core in the scientific workforce. PLoS One, 9 (7), e101698.

Jaccard, J. (2001). Interaction effects in logistic regression. Sage University papers series on quantitative applications in the social sciences, 07–135 . Thousand Oakes: Sage.

Katz, J. S., & Martin, B. R. (1997). What is research collaboration? Research Policy, 26 (1), 1–18.

Klavans, R., & Boyack, K. (2011). Scientific superstars and their effect on the evolution of science. Paper presented at science and technology indicators conference, Rome, Italy.

Kuenzi, M., & Schminke, M. (2009). Assembling fragments into a lens: a review, critique, and proposed research agenda for the organizational work climate literature. Journal of Management, 35 (3), 634–717.

Kwiek, M. (2016). The European research elite: a cross-national study of highly productive academics in 11 countries. Higher Education, 71 (3), 379–397.

Kwiek, M. (2018). High research productivity in vertically undifferentiated higher education systems: who are the top performers? Scientometrics, 115 (1), 415–462.

Kwiek, M. (2019). Changing European academics: a comparative study of social stratification, work patterns and research productivity . London: Routledge.

Lawrence, P. A. (2007). The mismeasurement of science. Current Biology, 17 (15), R583–R585.

Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35 (5), 673–702.

Lincoln, A. E., Pincus, S., Koster, J. B., & Leboy, P. S. (2012). The Matilda effect in science: awards and prizes in the US, 1990s and 2000s. Social Studies of Science, 42 (2), 307–320.

Long, J. S., & Fox, M. F. (1995). Scientific careers: universalism and particularism. Annual Review of Sociology, 21 (1), 45–71.

Louis, K. S., Holdsworth, J. M., Anderson, M. S., & Campbell, E. G. (2007). Becoming a scientist: the effects of work-group size and organizational climate. The Journal of Higher Education, 78 (3), 311–336.

Mairesse, J., & Pezzoni, M. (2015). Does gender affect scientific performance? Revue Economique, 66 (1), 65–114.

Marginson, S. (2014) University research: the social contribution of university research. In J. C. Shin & U. Teichler (Eds.), The Future of the Post-massified University at the Crossroads (pp. 101–118). Springer International Publishing.

Menard, S. W. (2010). Logistic regression: from introductory to advanced concepts and applications . Los Angeles: Sage.

Merton, R. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159 (January), 56–63.

Montgomery, S. L. (1994). Minds for the making. In The role of science in American education, 1750–1900 . New York: Guilford Press.

National Science Board. (2016). Science and Engineering Indicators (NSB-2016) . Arlington: National Science Foundation.

Newman, M. E. J. (2005). Power laws, Pareto distributions, and Zipf’s law. Contemporary Physics, 46 (5), 323–351.

Pao, M. (1991). On the relationship of funding and research publications. Scientometrics, 20 (1), 257–281.

Parker, J., Lortie, C., & Allesina, S. (2010). Characterizing a scientific elite: the social characteristics of the world’s most highly cited scientists in environmental science and ecology. Scientometrics, 85 (1), 129–143.

Parker, J., Allesina, S., & Lortie, C. (2013). Characterizing a scientific elite (B): publication and citation patterns of the most highly cited scientists in environmental science and ecology. Scientometrics, 94 (2), 469–480.

Patterson, M. G., West, W. A., Shackelton, V., Dawson, J. F., Lathom, R., Maitlis, S., Robinson, D., & Wallace, S. M. (2005). Validating the organizational climate measure. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26 (4), 379–408.

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Kemper, E., Holford, T. R., & Feinstein, A. R. (1996). A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 49 (12), 1373–1379.

Pei, R., & Porter, A. L. (2011). Profiling leading scientists in nanobiomedical science: interdisciplinarity and potential leading indicators of research directions. R&D Management, 41 (3), 288–306.

Pelz, D., & Andrews, F. (1976). Scientists in organizations: productive climates for research and development . Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research.

Prpić, K. (1996). Characteristics and determinants of eminent scientists’ productivity. Scientometrics, 36 (2), 185–206.

Ramsden, P. (1994). Describing and explaining research productivity. Higher Education, 28 (2), 207–226.

Root-Berstein, R. S., Berstein, M., & Garnier. (1995). Correlations between avocations, scientific style, work habits, and professional impact of scientists. Creativity Research Journal, 8 (2), 115–137.

Rørstad, K., & Aksnes, D. W. (2015). Publication rate expressed by age, gender and academic position—a large-scale analysis of Norwegian academic staff. Journal of Informetrics, 9 (2), 317–333.

Roth, W., & Sonnert, G. (2011). The costs and benefits of ‘red tape’: anti-bureaucratic structure and gender inequity in a science research organization. Social Studies of Science, 41 (3), 385–409.

Shwed, U., & Bearman, P. S. (2010). The temporal structure of scientific consensus formation. American Sociological Review, 75 (6), 817–840.

Smeby, J. C., & Try, S. (2005). Departmental contexts and faculty research activity in Norway. Research in Higher Education, 46 (6), 593–619.

Stephan, P. (2012). How economics shapes science . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Taylor, B. J., & Cantwell, B. (2019). Unequal higher education: Wealth, status, and student opportunity . Rutgers University Press.

Teodorescu, D. (2000). Correlates of faculty publication productivity: a cross-national analysis. Higher Education, 39 (2), 201–222.

Torrisi, B. (2013). Academic productivity correlated with well-being at work. Scientometrics, 94 (2), 801–815.

van den Besselaar, P., & Sandstrom, U. (2015). Does quantity make a difference? In A. Salah, & S. Sugimoto (Eds.), Proceedings of International Conference on Scientometrics and Informetrics (ISSI) (pp. 577–583). Istanbul, Turkey.

Wager, E., Singhvi, S., & Kleinert, S. (2015). Too much of a good thing? An observational study of prolific authors. PeerJ, 3 , e1154. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1154 .

Article Google Scholar

Warshaw, J. B., & Hearn, J. C. (2014). Leveraging university research to serve economic development: an analysis of policy dynamics in and across three US states. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36 (2), 196–211.

Wolpert, L., & Richards, A. (2007). Passionate minds: The inner world of scientists . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wuchty, S., Jones, B., & Uzzi, B. (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316 (5827), 1036–1039.

Xie, Y., & Shauman, K. (2003). Women in science: career processes and outcomes . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Zhang, J. Y. (2010). The organization of scientists and its relation to scientific productivity: perceptions of Chinese stem cell researchers. Biosocieties, 5 (2), 219–235.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology, 307 DM Smith Building, 685 Cherry Street, Atlanta, GA, 30332-0345, USA

Mary Frank Fox & Irina Nikivincze

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mary Frank Fox .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 41 kb)

(DOC 58 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fox, M.F., Nikivincze, I. Being highly prolific in academic science: characteristics of individuals and their departments. High Educ 81 , 1237–1255 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00609-z

Download citation

Published : 24 August 2020

Issue Date : June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00609-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Prolific publication

- Academic science

- Universities

- Stratification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of prolific

- cornucopian

fertile , fecund , fruitful , prolific mean producing or capable of producing offspring or fruit.

fertile implies the power to reproduce in kind or to assist in reproduction and growth

; applied figuratively, it suggests readiness of invention and development.

fecund emphasizes abundance or rapidity in bearing fruit or offspring.

fruitful adds to fertile and fecund the implication of desirable or useful results.

prolific stresses rapidity of spreading or multiplying by or as if by natural reproduction.

Examples of prolific in a Sentence

Word history.

French prolifique , from Middle French, from Latin proles + Middle French -figue -fic

1650, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Dictionary Entries Near prolific

proliferous

Cite this Entry

“Prolific.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/prolific. Accessed 18 Nov. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of prolific, more from merriam-webster on prolific.

Nglish: Translation of prolific for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of prolific for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

How to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), plural and possessive names: a guide, the difference between 'i.e.' and 'e.g.', why is '-ed' sometimes pronounced at the end of a word, what's the difference between 'fascism' and 'socialism', popular in wordplay, 8 words with fascinating histories, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, birds say the darndest things, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 10 scrabble words without any vowels, games & quizzes.

10 Steps to becoming a prolific scholar

1) Write 15–30 minutes daily

According to Gray, “Inspiration follows a daily writing habit, it doesn’t precede it.” She advises writing daily and making your writing a priority by scheduling it first in your workday – even if you are between projects.

2) Record Your Minutes Spent Writing—Share Records Daily

Gray argues that it is not enough simply to develop a habit of writing daily, but that it is important to share your results with someone who can hold you accountable. She says, “Hold yourself accountable to a writing coach the way athletes do. Be accountable for writing daily.” Even a quick email with just two digits in the subject line – your minutes spent writing – can serve as accountability communication with your coach. A good coach will be invested in your writing, so Gray suggests selecting someone who cares about your success and whose opinion you care deeply about.

3) Write informally from the first day of your research project

Writing freely without trying to revise your paragraphs as you write is a tactic that Gray says may seem pointless but leads you to more focused, purposeful writing. She also states that our time spent reading should be focused on reading to write, not on reading to learn.

4) Outline based on an exemplar – an excellent paper, grant proposal, thesis, etc. on a subject as close to your research as possible

“Writing becomes easier when working with an outline because you are filling in blanks”, states Gray. By starting with an exemplar, you can outline the topics covered in the model and further outline what you will do in your paper to parallel the original work.

5) Identify key sentences

“Key sentences represent the point of the paragraph, are often found early in the paragraph, and cover everything in the paragraph – but no more”, says Gray. Once identified, the key sentences are used to organize paragraphs by transition, topic, and support or evidence.

6) Make a list of key sentences – an after the fact outline or “reverse outline” to help organize between paragraphs

With the reverse outline, Gray advises reading the key sentences both backwards and forwards. First, read them backwards to check for purpose and remove ones that don’t serve the purpose of the paper. Next, read them forward to check for organization, reordering as necessary. Finally, re-read your changes and repeat the process as needed.

7) Seek informal feedback before formal review

There are two key types of informal reviewers that Gray suggests seeking before the formal review – non-experts and Capital-E experts. Non-experts may be outside your discipline – even family and friends, whereas the Capital-E experts are those you cite most in your work. Gray says that with either audience it is important to ask pointed questions. For non-experts, ask “In what two places is my paper 1) least clear, 2) least organized, and 3) least persuasive?” When approaching the Capital-E experts, she adds “explain how their work informed yours, ask specific questions, ask for a ‘quick read’, ask ‘where to send the manuscript’, and volunteer to read for them” for a greater response rate.

8) Respond effectively to feedback

The goal of review and feedback is improvement, but in order to improve you must be open to and act upon the feedback received. Gray makes two suggestions for responding effectively to feedback. First, “listen without judgement, keep your readers talking or writing, and realize that when it comes to clarity the reader is always right.” Second, “respond thoroughly and quickly by doing something with each feedback item.”

9) Read your manuscript out loud

Reading out loud just before sending to press allows you to “see your manuscript through a new lens and make your prose more conversational”, says Gray. To slow the process down, she suggests reading paragraph by paragraph backwards. Where you find wordy sentences, break them apart. To untangle sentences, she adds, “put the subject and verb together within the first seven words of the sentence.”

10) Kick it out the door and make them say No!

At this point, Gray says only three obstacles remain – pride, perfectionism, and fear of rejection. Offering advice on how to overcome all three, she concludes, “Your job is to write it and submit it. Your reviewer’s job is to tell you if it will embarrass you publicly, so kick it out the door and make them say yes.”

The complete session recordings are available in TAA’s Presentations on Demand library.

Tara’s book, Publish & Flourish: Become a Prolific Scholar , can be purchased in both paperback and eBook versions.