Take control of your money! Save, budget and navigate your finances easier with AARP Money Map.

AARP daily Crossword Puzzle

Hotels with AARP discounts

Life Insurance

AARP Dental Insurance Plans

AARP MEMBERSHIP — Limited Time Offer-Memorial Day Sale

Join AARP for just $9 per year with a 5-year membership. Join now and get a FREE Gift! Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

- right_container

Work & Jobs

Social Security

AARP en Español

- Membership & Benefits

AARP Rewards

- AARP Rewards %{points}%

Conditions & Treatments

Drugs & Supplements

Health Care & Coverage

Health Benefits

Staying Fit

Your Personalized Guide to Fitness

Get Happier

Creating Social Connections

Brain Health Resources

Tools and Explainers on Brain Health

Your Health

8 Major Health Risks for People 50+

Scams & Fraud

Personal Finance

Money Benefits

View and Report Scams in Your Area

AARP Foundation Tax-Aide

Free Tax Preparation Assistance

AARP Money Map

Get Your Finances Back on Track

How to Protect What You Collect

Small Business

Age Discrimination

Flexible Work

Freelance Jobs You Can Do From Home

AARP Skills Builder

Online Courses to Boost Your Career

31 Great Ways to Boost Your Career

ON-DEMAND WEBINARS

Tips to Enhance Your Job Search

Get More out of Your Benefits

When to Start Taking Social Security

10 Top Social Security FAQs

Social Security Benefits Calculator

Medicare Made Easy

Original vs. Medicare Advantage

Enrollment Guide

Step-by-Step Tool for First-Timers

Prescription Drugs

9 Biggest Changes Under New Rx Law

Medicare FAQs

Quick Answers to Your Top Questions

Care at Home

Financial & Legal

Life Balance

LONG-TERM CARE

Understanding Basics of LTC Insurance

State Guides

Assistance and Services in Your Area

Prepare to Care Guides

How to Develop a Caregiving Plan

End of Life

How to Cope With Grief, Loss

Recently Played

Word & Trivia

Atari® & Retro

Members Only

Staying Sharp

Mobile Apps

More About Games

Right Again! Trivia

Right Again! Trivia – Sports

Atari® Video Games

Throwback Thursday Crossword

Travel Tips

Vacation Ideas

Destinations

Travel Benefits

Outdoor Vacation Ideas

Camping Vacations

Plan Ahead for Summer Travel

AARP National Park Guide

Discover Canyonlands National Park

History & Culture

8 Amazing American Pilgrimages

Entertainment & Style

Family & Relationships

Personal Tech

Home & Living

Celebrities

Beauty & Style

Movies for Grownups

Summer Movie Preview

Jon Bon Jovi’s Long Journey Back

Looking Back

50 World Changers Turning 50

Sex & Dating

Spice Up Your Love Life

Friends & Family

How to Host a Fabulous Dessert Party

Home Technology

Caregiver’s Guide to Smart Home Tech

Virtual Community Center

Join Free Tech Help Events

Create a Hygge Haven

Soups to Comfort Your Soul

AARP Solves 25 of Your Problems

Driver Safety

Maintenance & Safety

Trends & Technology

AARP Smart Guide

How to Clean Your Car

We Need To Talk

Assess Your Loved One's Driving Skills

AARP Smart Driver Course

Building Resilience in Difficult Times

Tips for Finding Your Calm

Weight Loss After 50 Challenge

Cautionary Tales of Today's Biggest Scams

7 Top Podcasts for Armchair Travelers

Jean Chatzky: ‘Closing the Savings Gap’

Quick Digest of Today's Top News

AARP Top Tips for Navigating Life

Get Moving With Our Workout Series

You are now leaving AARP.org and going to a website that is not operated by AARP. A different privacy policy and terms of service will apply.

Go to Series Main Page

What is Medicare assignment and how does it work?

Kimberly Lankford,

Because Medicare decides how much to pay providers for covered services, if the provider agrees to the Medicare-approved amount, even if it is less than they usually charge, they’re accepting assignment.

A doctor who accepts assignment agrees to charge you no more than the amount Medicare has approved for that service. By comparison, a doctor who participates in Medicare but doesn’t accept assignment can potentially charge you up to 15 percent more than the Medicare-approved amount.

That’s why it’s important to ask if a provider accepts assignment before you receive care, even if they accept Medicare patients. If a doctor doesn’t accept assignment, you will pay more for that physician’s services compared with one who does.

AARP Membership — $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

How much do I pay if my doctor accepts assignment?

If your doctor accepts assignment, you will usually pay 20 percent of the Medicare-approved amount for the service, called coinsurance, after you’ve paid the annual deductible. Because Medicare Part B covers doctor and outpatient services, your $240 deductible for Part B in 2024 applies before most coverage begins.

All providers who accept assignment must submit claims directly to Medicare, which pays 80 percent of the approved cost for the service and will bill you the remaining 20 percent. You can get some preventive services and screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies , without paying a deductible or coinsurance if the provider accepts assignment.

What if my doctor doesn’t accept assignment?

A doctor who takes Medicare but doesn’t accept assignment can still treat Medicare patients but won’t always accept the Medicare-approved amount as payment in full.

This means they can charge you up to a maximum of 15 percent more than Medicare pays for the service you receive, called “balance billing.” In this case, you’re responsible for the additional charge, plus the regular 20 percent coinsurance, as your share of the cost.

How to cover the extra cost? If you have a Medicare supplement policy , better known as Medigap, it may cover the extra 15 percent, called Medicare Part B excess charges.

All Medigap policies cover Part B’s 20 percent coinsurance in full or in part. The F and G policies cover the 15 percent excess charges from doctors who don’t accept assignment, but Plan F is no longer available to new enrollees, only those eligible for Medicare before Jan. 1, 2020, even if they haven’t enrolled in Medicare yet. However, anyone who is enrolled in original Medicare can apply for Plan G.

Remember that Medigap policies only cover excess charges for doctors who accept Medicare but don’t accept assignment, and they won’t cover costs for doctors who opt out of Medicare entirely.

Good to know. A few states limit the amount of excess fees a doctor can charge Medicare patients. For example, Massachusetts and Ohio prohibit balance billing, requiring doctors who accept Medicare to take the Medicare-approved amount. New York limits excess charges to 5 percent over the Medicare-approved amount for most services, rather than 15 percent.

AARP NEWSLETTERS

%{ newsLetterPromoText }%

%{ description }%

Privacy Policy

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

How do I find doctors who accept assignment?

Before you start working with a new doctor, ask whether he or she accepts assignment. About 98 percent of providers billing Medicare are participating providers, which means they accept assignment on all Medicare claims, according to KFF.

You can get help finding doctors and other providers in your area who accept assignment by zip code using Medicare’s Physician Compare tool .

Those who accept assignment have this note under the name: “Charges the Medicare-approved amount (so you pay less out of pocket).” However, not all doctors who accept assignment are accepting new Medicare patients.

AARP® Vision Plans from VSP™

Exclusive vision insurance plans designed for members and their families

What does it mean if a doctor opts out of Medicare?

Doctors who opt out of Medicare can’t bill Medicare for services you receive. They also aren’t bound by Medicare’s limitations on charges.

In this case, you enter into a private contract with the provider and agree to pay the full bill. Be aware that neither Medicare nor your Medigap plan will reimburse you for these charges.

In 2023, only 1 percent of physicians who aren’t pediatricians opted out of the Medicare program, according to KFF. The percentage is larger for some specialties — 7.7 percent of psychiatrists and 4.2 percent of plastic and reconstructive surgeons have opted out of Medicare.

Keep in mind

These rules apply to original Medicare. Other factors determine costs if you choose to get coverage through a private Medicare Advantage plan . Most Medicare Advantage plans have provider networks, and they may charge more or not cover services from out-of-network providers.

Before choosing a Medicare Advantage plan, find out whether your chosen doctor or provider is covered and identify how much you’ll pay. You can use the Medicare Plan Finder to compare the Medicare Advantage plans and their out-of-pocket costs in your area.

Return to Medicare Q&A main page

Kimberly Lankford is a contributing writer who covers Medicare and personal finance. She wrote about insurance, Medicare, retirement and taxes for more than 20 years at Kiplinger’s Personal Finance and has written for The Washington Post and Boston Globe . She received the personal finance Best in Business award from the Society of American Business Editors and Writers and the New York State Society of CPAs’ excellence in financial journalism award for her guide to Medicare.

Discover AARP Members Only Access

Already a Member? Login

More on Medicare

How Do I Create a Personal Online Medicare Account?

You can do a lot when you decide to look electronically

I Got a Medicare Summary Notice in the Mail. What Is It?

This statement shows what was billed, paid in past 3 months

Understanding Medicare’s Options: Parts A, B, C and D

Making sense of the alphabet soup of health care choices

Recommended for You

AARP Value & Member Benefits

Learn, earn and redeem points for rewards with our free loyalty program

AARP® Dental Insurance Plan administered by Delta Dental Insurance Company

Dental insurance plans for members and their families

The National Hearing Test

Members can take a free hearing test by phone

AARP® Staying Sharp®

Activities, recipes, challenges and more with full access to AARP Staying Sharp®

SAVE MONEY WITH THESE LIMITED-TIME OFFERS

What Does It Mean for a Doctor to Accept Medicare Assignment?

Written by: Malini Ghoshal, RPh, MS

Reviewed by: Malinda Cannon, Licensed Insurance Agent

Key Takeaways

Doctors who accept Medicare assignment are paid agreed-upon rates for services.

It’s important to verify that your doctor accepts assignment before receiving services to avoid high out-of-pocket costs.

A doctor or clinician may be “non-participating” but can still agree to accept Medicare assignment for some services.

If you visit a doctor or clinician who has opted out (doesn’t accept Medicare), you may have to pay for your entire visit cost unless it’s a medical emergency.

Medigap Supplemental insurance (Medigap) plans won’t pay for service costs from doctors who don’t accept assignment.

One of the things that Original Medicare beneficiaries often enjoy about their coverage is that they can use it anywhere in the country. Unlike plans with provider networks, they can visit doctors either at home or on the road; both are covered the same.

But do all doctors accept Medicare patients?

Truth is, this wide-ranging coverage area only applies to doctors who accept Medicare assignment. Fortunately, most do. If you’re eligible for Medicare, it’s important to visit doctors and clinicians who accept Medicare assignment. This will help keep your out-of-pocket costs within your control. Doctors who agree to accept Medicare assignment sign an agreement that they’re willing to accept payment from Medicare for their services.

If you’re a current beneficiary or nearing enrollment, you may have other questions. Do all doctors accept Medicare Advantage plans? What about Medicare Supplement insurance (Medigap)? Read on to learn how to find doctors that accept Medicare assignment and how this keeps your healthcare costs down.

Find the Medicare Advantage plan that meets your needs.

What Is Medicare Assignment of Benefits?

When you’re eligible for Medicare, you have the option to visit doctors and clinicians who accept assignment. This means they are Medicare-approved providers who agree to receive Medicare reimbursement rates for covered services. This helps save you money.

If you have Original Medicare (Part A and B), your doctor visits are covered by your Part B plan. Inpatient services such as hospital stays and some skilled nursing care are covered by Part A .

In order for a participating doctor (or facility) to bill Medicare and be reimbursed, you must authorize Medicare to reimburse your doctor directly for your covered services. This is called the Medicare assignment of benefits. You transfer your right to receive Medicare payment for a covered service to your doctor or other provider.

Note: If you have a Medicare Supplement insurance ( Medigap ) plan to pay for out-of-pocket costs, you may also need to sign a separate assignment of benefits form for Medigap reimbursement. More on Medigap below.

How Can I Find Doctors Near Me That Accept Medicare?

There are several ways to find doctors and other clinicians who accept Medicare assignment close to you.

First, let’s take a look at the different types of Medicare providers.

They include:

Participating providers: Medicare-participating doctors and providers sign a participation agreement stating they will accept Medicare reimbursement rates for their services.

Non-participating providers: Doctors or providers who are non-participating providers are eligible to accept Medicare assignment but haven’t signed a Medicare agreement. They may choose to accept assignment on a case-by-case basis. If you visit a non-participating provider, make sure to ask if they accept assignment for your particular service. Also get a copy of their fees. They will need to select “yes” on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CMS Form 1500 to accept assignment for the service.

Opt-out providers: Some doctors and other providers choose not to accept Medicare. If they choose to opt out, the period is two years (based on Medicare guidelines). The opt-out automatically renews if the provider doesn’t request a change in their status. You would be responsible for paying all costs for services received from an opt-out provider. You cannot bill Medicare for reimbursement unless the service was an urgent or emergency medical need. According to a report from KFF , roughly 1% of non-pediatric physicians opted out of Medicare in 2023.

Visiting a doctor who doesn’t accept assignment may cost you more. These providers can charge you up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved rate for a given service. This 15% charge is called the limiting charge. Some states limit this extra charge to a certain percent. This may also be called the Part B excess charge.

Here are some tips for finding doctors and providers who accept Medicare assignment:

- The easiest way to find a doctor who accepts Medicare assignment is to contact their office and ask them directly.

- If you’re looking for a new doctor, you can use the Medicare search tool to find clinicians and doctors that accept Medicare assignment.

- You can also ask a state health insurance assistance program (SHIP) representative for help in locating a doctor that accepts Medicare assignment.

- Don’t assume that having a longstanding relationship with your doctor means nothing will ever change. Check in with them to make sure they still accept Medicare assignment and whether they’re planning to opt out.

Note: Your doctor can choose to become a non-participating provider or opt out of participating in Medicare. It’s important to verify they accept Medicare assignment before receiving any services.

Ready for a new Medicare Advantage plan?

Do Doctors Who Accept Medicare Have to Accept Supplement Plans?

If your doctor accepts Medicare assignment and you have Original Medicare (Medicare Part A and Part B) with a Medicare Supplement (Medigap) plan, they will accept the supplemental insurance. Depending on your Medigap plan coverage , it may pay all or part of your out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles, copayments and coinsurance.

However, if you have a Medicare Advantage plan (Part C), you may have a network of covered doctors under the plan. If you visit an out-of-network doctor, you may need to pay all or part of the cost for your services.

Keep in mind that you can’t have a Medigap supplemental plan if you have a Medicare Advantage plan.

If you have questions or want to learn more about different Medicare plans like Original Medicare with Medigap versus Medicare Advantage, GoHealth has licensed insurance agents ready to help. They can shop your different options and offer impartial guidance where you need it.

Do Most Doctors Accept Medicare Advantage Plans?

Many doctors accept Medicare Advantage (Part C) plans, but these plans often use provider networks. These networks are groups of doctors and providers in an area that have agreed to treat an insurance company’s customers. If you have a Part C plan, you may be required to see in-network doctors with few exceptions. However, these types of plans are popular options for all-in-one coverage for your health needs. Plans must offer Part A and B coverage, plus a majority also include Part D , or prescription drug coverage. But whether a doctor accepts a Medicare Advantage plan may depend on where you live and the type of Medicare Advantage plan you have.

There are several types of Medicare Advantage plans including:

- Health Maintenance Organization (HMO): These plans have a network of covered providers, as well as a primary care physician to manage your care. If you visit a doctor outside your plan network, you may have to pay the full cost of your visit.

- Preferred Provider Organization (PPO): You’ll probably still have a primary care physician, but these are more flexible plans that allow you to go out of network in some cases. But you may have to pay more.

- Private Fee for Service (PFFS): You may be able to visit any doctor or provider with these plans, but your costs may be higher.

- Special Needs Plan (SNP): This type of plan is only for certain qualified individuals who either have a specific health condition ( C-SNP ) or who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare insurance ( D-SNP ).

Still have questions? GoHealth has the answers you need.

What Are Medicare Assignment Codes?

Medicare assignment codes help Medicare pay for covered services. If your doctor or other provider accepts assignment and is a participating provider, they will file for reimbursement for services with a CMS-1500 form and the code will be “assigned.”

But non-participating providers can select “not assigned.” This means they are not accepting Medicare-assigned rates for a given service. They can charge up to 15% over the full Medicare rate for the service.

If you go to a doctor or provider who accepts assignment, you don’t need to file your own claim. Your doctor’s office will directly file with Medicare. Always check to make sure your doctor accepts assignment to avoid excess charges from your visit.

Health Insurance Claim Form . CMS.gov.

Lower costs with assignment . Medicare.gov.

How Many Physicians Have Opted-Out of the Medicare Program? KFF.org.

Joining a plan . Medicare.gov.

This website is operated by GoHealth, LLC., a licensed health insurance company. The website and its contents are for informational and educational purposes; helping people understand Medicare in a simple way. The purpose of this website is the solicitation of insurance. Contact will be made by a licensed insurance agent/producer or insurance company. Medicare Supplement insurance plans are not connected with or endorsed by the U.S. government or the federal Medicare program. Our mission is to help every American get better health insurance and save money. Any information we provide is limited to those plans we do offer in your area. Please contact Medicare.gov or 1-800-MEDICARE to get information on all of your options.

Let's see if you're missing out on Medicare savings.

We just need a few details.

Related Articles

What Is Medicare IRMAA?

What Is an IRMAA in Medicare?

How to Report Medicare Fraud

Medicare Fraud Examples & How to Report Abuse

How to Change Your Address with Medicare

Reporting a Change of Address to Medicare

Can I Get Medicare if I’ve Never Worked?

Can You Get Medicare if You've Never Worked?

Why Are Some Medicare Advantage Plans Free?

Why Are Some Medicare Advantage Plans Free? $0 Premium Plans Explained

What Is Medicare Assignment?

Am I Enrolled in Medicare?

When and How Do I Enroll?

When and How Do I Enroll in Medicare?

Medicare Frequently Asked Questions

Let’s see if you qualify for Medicare savings today!

Medicare Interactive Medicare answers at your fingertips -->

Participating, non-participating, and opt-out providers, outpatient provider services.

You must be logged in to bookmark pages.

Email Address * Required

Password * Required

Lost your password?

If you have Original Medicare , your Part B costs once you have met your deductible can vary depending on the type of provider you see. For cost purposes, there are three types of provider, meaning three different relationships a provider can have with Medicare . A provider’s type determines how much you will pay for Part B -covered services.

- These providers are required to submit a bill (file a claim ) to Medicare for care you receive. Medicare will process the bill and pay your provider directly for your care. If your provider does not file a claim for your care, there are troubleshooting steps to help resolve the problem .

- If you see a participating provider , you are responsible for paying a 20% coinsurance for Medicare-covered services.

- Certain providers, such as clinical social workers and physician assistants, must always take assignment if they accept Medicare.

- Non-participating providers can charge up to 15% more than Medicare’s approved amount for the cost of services you receive (known as the limiting charge ). This means you are responsible for up to 35% (20% coinsurance + 15% limiting charge) of Medicare’s approved amount for covered services.

- Some states may restrict the limiting charge when you see non-participating providers. For example, New York State’s limiting charge is set at 5%, instead of 15%, for most services. For more information, contact your State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP) .

- If you pay the full cost of your care up front, your provider should still submit a bill to Medicare. Afterward, you should receive from Medicare a Medicare Summary Notice (MSN) and reimbursement for 80% of the Medicare-approved amount .

- The limiting charge rules do not apply to durable medical equipment (DME) suppliers . Be sure to learn about the different rules that apply when receiving services from a DME supplier .

- Medicare will not pay for care you receive from an opt-out provider (except in emergencies). You are responsible for the entire cost of your care.

- The provider must give you a private contract describing their charges and confirming that you understand you are responsible for the full cost of your care and that Medicare will not reimburse you.

- Opt-out providers do not bill Medicare for services you receive.

- Many psychiatrists opt out of Medicare.

Providers who take assignment should submit a bill to a Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) within one calendar year of the date you received care. If your provider misses the filing deadline, they cannot bill Medicare for the care they provided to you. However, they can still charge you a 20% coinsurance and any applicable deductible amount.

Be sure to ask your provider if they are participating, non-participating, or opt-out. You can also check by using Medicare’s Physician Compare tool .

Update your browser to view this website correctly. Update my browser now

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Balance Billing in Health Insurance

- How It Works

- When It Happens

- What to Do If You Get a Bill

- If You Know in Advance

Balance billing happens after you’ve paid your deductible , coinsurance or copayment and your insurance company has also paid everything it’s obligated to pay toward your medical bill. If there is still a balance owed on that bill and the healthcare provider or hospital expects you to pay that balance, you’re being balance billed.

This article will explain how balance billing works, and the rules designed to protect consumers from some instances of balance billing.

Is Balance Billing Legal or Not?

Sometimes it’s legal, and sometimes it isn’t; it depends on the circumstances.

Balance billing is generally illegal :

- When you have Medicare and you’re using a healthcare provider that accepts Medicare assignment .

- When you have Medicaid and your healthcare provider has an agreement with Medicaid.

- When your healthcare provider or hospital has a contract with your health plan and is billing you more than that contract allows.

- In emergencies (with the exception of ground ambulance charges), or situations in which you go to an in-network hospital but unknowingly receive services from an out-of-network provider.

In the first three cases, the agreement between the healthcare provider and Medicare, Medicaid, or your insurance company includes a clause that prohibits balance billing.

For example, when a hospital signs up with Medicare to see Medicare patients, it must agree to accept the Medicare negotiated rate, including your deductible and/or coinsurance payment, as payment in full. This is called accepting Medicare assignment .

And for the fourth case, the No Surprises Act , which took effect in 2022, protects you from "surprise" balance billing.

Balance billing is usually legal :

- When you choose to use a healthcare provider that doesn’t have a relationship or contract with your insurer (including ground ambulance charges, even after implementation of the No Surprises Act).

- When you’re getting services that aren’t covered by your health insurance policy, even if you’re getting those services from a provider that has a contract with your health plan.

The first case (a provider not having an insurer relationship) is common if you choose to seek care outside of your health insurance plan's network.

Depending on how your plan is structured, it may cover some out-of-network costs on your behalf. But the out-of-network provider is not obligated to accept your insurer's payment as payment in full. They can send you a bill for the remainder of the charges, even if it's more than your plan's out-of-network copay or deductible.

(Some health plans, particularly HMOs and EPOs , simply don't cover non-emergency out-of-network services at all, which means they would not cover even a portion of the bill if you choose to go outside the plan's network.)

Getting services that are not covered is a situation that may arise, for example, if you obtain cosmetic procedures that aren’t considered medically necessary, or fill a prescription for a drug that isn't on your health plan's formulary . You’ll be responsible for the entire bill, and your insurer will not require the medical provider to write off any portion of the bill—the claim would simply be rejected.

Prior to 2022, it was common for people to be balance billed in emergencies or by out-of-network providers that worked at in-network hospitals. In some states, state laws protected people from these types of surprise balance billing if they had state-regulated health plans.

But not all states had these protections. And the majority of people with employer-sponsored health insurance are covered under self-insured plans, which are not subject to state regulations. This is why the No Surprises Act was so necessary.

How Balance Billing Works

When you get care from a doctor, hospital, or other healthcare provider that isn’t part of your insurer’s provider network (or, if you have Medicare, from a provider that has opted out of Medicare altogether , which is rare but does apply in some cases ), that healthcare provider can charge you whatever they want to charge you (with the exception of emergencies or situations where you receive services from an out-of-network provider while you're at an in-network hospital).

Since your insurance company hasn’t negotiated any rates with that provider, they aren't bound by a contract with your health plan.

Medicare Limiting Charge

If you have Medicare and your healthcare provider is a nonparticipating provider but hasn't entirely opted out of Medicare, you can be charged up to 15% more than the allowable Medicare amount for the service you receive (some states impose a lower limit).

This 15% cap is known as the limiting charge, and it serves as a restriction on balance billing in some cases. If your healthcare provider has opted out of Medicare entirely, they cannot bill Medicare at all and you'll be responsible for the full cost of your visit.

If your health insurance company agrees to pay a percentage of your out-of-network care, the health plan doesn’t pay a percentage of what’s actually billed . Instead, it pays a percentage of what it says should have been billed, otherwise known as a reasonable and customary amount.

As you might guess, the reasonable and customary amount is usually lower than the amount you’re actually billed. The balance bill comes from the gap between what your insurer says is reasonable and customary, and what the healthcare provider or hospital actually charges.

Let's take a look at an example in which a person's health plan has 20% coinsurance for in-network hospitalization and 40% coinsurance for out-of-network hospitalization. And we're going to assume that the No Surprises Act does not apply (ie, that the person chooses to go to an out-of-network hospital, and it's not an emergency situation).

In this scenario, we'll assume that the person already met their $1,000 in-network deductible and $2,000 out-of-network deductible earlier in the year (so the example is only looking at coinsurance).

And we'll also assume that the health plan has a $6,000 maximum out-of-pocket for in-network care, but no cap on out-of-pocket costs for out-of-network care:

When Does Balance Billing Happen?

In the United States, balance billing usually happens when you get care from a healthcare provider or hospital that isn’t part of your health insurance company’s provider network or doesn’t accept Medicare or Medicaid rates as payment in full.

If you have Medicare and your healthcare provider has opted out of Medicare entirely, you're responsible for paying the entire bill yourself. But if your healthcare provider hasn't opted out but just doesn't accept assignment with Medicare (ie, doesn't accept the amount Medicare pays as payment in full), you could be balance billed up to 15% more than Medicare's allowable charge, in addition to your regular deductible and/or coinsurance payment.

Surprise Balance Billing

Receiving care from an out-of-network provider can happen unexpectedly, even when you try to stay in-network. This can happen in emergency situations—when you may simply have no say in where you're treated or no time to get to an in-network facility—or when you're treated by out-of-network providers who work at in-network facilities.

For example, you go to an in-network hospital, but the radiologist who reads your X-rays isn’t in-network. The bill from the hospital reflects the in-network rate and isn't subject to balance billing, but the radiologist doesn’t have a contract with your insurer, so they can charge you whatever they want. And prior to 2022, they were allowed to send you a balance bill unless state law prohibited it.

Similar situations could arise with:

- Anesthesiologists

- Pathologists (laboratory doctors)

- Neonatologists (doctors for newborns)

- Intensivists (doctors who specialize in ICU patients)

- Hospitalists (doctors who specialize in hospitalized patients)

- Radiologists (doctors who interpret X-rays and scans)

- Ambulance services to get you to the hospital, especially air ambulance services, where balance billing was frighteningly common

- Durable medical equipment suppliers (companies that provide the crutches, braces, wheelchairs, etc. that people need after a medical procedure)

These "surprise" balance billing situations were particularly infuriating for patients, who tended to believe that as long as they had selected an in-network medical facility, all of their care would be covered under the in-network terms of their health plan.

To address this situation, many states enacted consumer protection rules that limited surprise balance billing prior to 2022. But as noted above, these state rules don't protect people with self-insured employer-sponsored health plans, which cover the majority of people who have employer-sponsored coverage.

There had long been broad bipartisan support for the idea that patients shouldn't have to pay additional, unexpected charges just because they needed emergency care or inadvertently received care from a provider outside their network, despite the fact that they had purposely chosen an in-network medical facility. There was disagreement, however, in terms of how these situations should be handled—should the insurer have to pay more, or should the out-of-network provider have to accept lower payments? This disagreement derailed numerous attempts at federal legislation to address surprise balance billing.

But the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, which was enacted in December 2020, included broad provisions (known as the No Surprises Act) to protect consumers from surprise balance billing as of 2022. The law applies to both self-insured and fully-insured plans, including grandfathered plans, employer-sponsored plans, and individual market plans.

It protects consumers from surprise balance billing charges in nearly all emergency situations and situations when out-of-network providers offer services at in-network facilities, but there's a notable exception for ground ambulance charges.

This is still a concern, as ground ambulances are among the medical providers most likely to balance bill patients and least likely to be in-network, and patients typically have no say in what ambulance provider comes to their rescue in an emergency situation. But other than ground ambulances, patients are no longer subject to surprise balance bills as of 2022.

The No Surprises Act did call for the creation of a committee to study ground ambulance charges and make recommendations for future legislation to protect consumers. The Biden Administration announced the members of that committee in late 2022, and the committee began holding meetings in May 2023.

Balance billing continues to be allowed in other situations (for example, the patient simply chooses to use an out-of-network provider). Balance billing can also still occur when you’re using an in-network provider, but you’re getting a service that isn’t covered by your health insurance. Since an insurer doesn’t negotiate rates for services it doesn’t cover, you’re not protected by that insurer-negotiated discount. The provider can charge whatever they want, and you’re responsible for the entire bill.

It is important to note that while the No Surprises Act prohibits balance bills from out-of-network working at in-network facilities, the final rule for implementation of the law defines facilities as "hospitals, hospital outpatient departments, critical access hospitals, and ambulatory surgical centers." Other medical facilities are not covered by the consumer protections in the No Surprises Act.

Balance billing doesn’t usually happen with in-network providers or providers that accept Medicare assignment . That's because if they balance bill you, they’re violating the terms of their contract with your insurer or Medicare. They could lose the contract, face fines, suffer severe penalties, and even face criminal charges in some cases.

If You Get an Unexpected Balance Bill

Receiving a balance bill is a stressful experience, especially if you weren't expecting it. You've already paid your deductible and coinsurance and then you receive a substantial additional bill—what do you do next?

First, you'll want to try to figure out whether the balance bill is legal or not. If the medical provider is in-network with your insurance company, or you have Medicare or Medicaid and your provider accepts that coverage, it's possible that the balance bill was a mistake (or, in rare cases, outright fraud).

And if your situation is covered under the No Surprises Act (ie, an emergency, or an out-of-network provider who treated you at an in-network facility), you should not be subject to a balance bill. So be sure you understand what charges you're actually responsible for before paying any medical bills.

If you think that the balance bill was an error, contact the medical provider's billing office and ask questions. Keep a record of what they tell you so that you can appeal to your state's insurance department if necessary.

If the medical provider's office clarifies that the balance bill was not an error and that you do indeed owe the money, consider the situation—did you make a mistake and select an out-of-network healthcare provider? Or was the service not covered by your health plan?

If you went to an in-network facility for a non-emergency, did you waive your rights under the No Surprises Act (NSA) and then receive a balance bill from an out-of-network provider? This is still possible in limited circumstances, but you would have had to sign a document indicating that you had waived your NSA protections.

Negotiate With the Medical Office

If you've received a legitimate balance bill, you can ask the medical office to cut you some slack. They may be willing to agree to a payment plan and not send your bill to collections as long as you continue to make payments.

Or they may be willing to reduce your total bill if you agree to pay a certain amount upfront. Be respectful and polite, but explain that the bill caught you off guard. And if it's causing you significant financial hardship, explain that too.

The healthcare provider's office would rather receive at least a portion of the billed amount rather than having to wait while the bill is sent to collections. So the sooner you reach out to them, the better.

Negotiate With Your Insurance Company

You can also negotiate with your insurer. If your insurer has already paid the out-of-network rate on the reasonable and customary charge, you’ll have difficulty filing a formal appeal since the insurer didn’t actually deny your claim . It paid your claim, but at the out-of-network rate.

Instead, request a reconsideration. You want your insurance company to reconsider the decision to cover this as out-of-network care , and instead cover it as in-network care. You’ll have more luck with this approach if you had a compelling medical or logistical reason for choosing an out-of-network provider .

If you feel like you’ve been treated unfairly by your insurance company, follow your health plan’s internal complaint resolution process.

You can get information about your insurer’s complaint resolution process in your benefits handbook or from your human resources department. If this doesn’t resolve the problem, you can complain to your state’s insurance department.

- Learn more about your internal and external appeal rights.

- Find contact information for your Department of Insurance using this resource .

If your health plan is self-funded , meaning your employer is the entity actually paying the medical bills even though an insurance company may administer the plan, then your health plan won't fall under the jurisdiction of your state’s department of insurance.

Self-funded plans are instead regulated by the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefit Services Administration. Get more information from the EBSA’s consumer assistance web page or by calling an EBSA benefits advisor at 1-866-444-3272.

If You Know You’ll Be Legally Balance Billed

If you know in advance that you’ll be using an out-of-network provider or a provider that doesn’t accept Medicare assignment, you have some options. However, none of them are easy and all require some negotiating.

Ask for an estimate of the provider’s charges. Next, ask your insurer what they consider the reasonable and customary charge for this service to be. Getting an answer to this might be tough, but be persistent.

Once you have estimates of what your provider will charge and what your insurance company will pay, you’ll know how far apart the numbers are and what your financial risk is. With this information, you can narrow the gap. There are only two ways to do this: Get your provider to charge less or get your insurer to pay more.

Ask the provider if he or she will accept your insurance company’s reasonable and customary rate as payment in full. If so, get the agreement in writing, including a no-balance-billing clause.

If your provider won’t accept the reasonable and customary rate as payment in full, start working on your insurer. Ask your insurer to increase the amount they’re calling reasonable and customary for this particular case.

Present a convincing argument by pointing out why your case is more complicated, difficult, or time-consuming to treat than the average case the insurer bases its reasonable and customary charge on.

Single-Case Contract

Another option is to ask your insurer to negotiate a single-case contract with your out-of-network provider for this specific service.

A single-case contract is more likely to be approved if the provider is offering specialized services that aren't available from locally-available in-network providers, or if the provider can make a case to the insurer that the services they're providing will end up being less expensive in the long-run for the insurance company.

Sometimes they can agree upon a single-case contract for the amount your insurer usually pays its in-network providers. Sometimes they’ll agree on a single-case contract at the discount rate your healthcare provider accepts from the insurance companies she’s already in-network with.

Or, sometimes they can agree on a single-case contract for a percentage of the provider’s billed charges. Whatever the agreement, make sure it includes a no-balance-billing clause.

Ask for the In-Network Coinsurance Rate

If all of these options fail, you can ask your insurer to cover this out-of-network care using your in-network coinsurance rate. While this won’t prevent balance billing, at least your insurer will be paying a higher percentage of the bill since your coinsurance for in-network care is lower than for out-of-network care.

If you pursue this option, have a convincing argument as to why the insurer should treat this as in-network. For example, there are no local in-network surgeons experienced in your particular surgical procedure, or the complication rates of the in-network surgeons are significantly higher than those of your out-of-network surgeon.

Balance billing refers to the additional bill that an out-of-network medical provider can send to a patient, in addition to the person's normal cost-sharing and the payments (if any) made by their health plan. The No Surprises Act provides broad consumer protections against "surprise" balance billing as of 2022.

A Word From Verywell

Try to prevent balance billing by staying in-network, making sure your insurance company covers the services you’re getting, and complying with any pre-authorization requirements. But rest assured that the No Surprises Act provides broad protections against surprise balance billing.

This means you won't be subject to balance bills in emergencies (except for ground ambulance charges, which can still generate surprise balance bills) or in situations where you go to an in-network hospital but unknowingly receive care from an out-of-network provider.

Congress.gov. H.R.133—Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 . Enacted December 27, 2021.

Kona M. The Commonwealth Fund. State balance billing protections . April 20, 2020.

Data.CMS.gov. Opt Out Affidavits .

Chhabra, Karan; Schulman, Kevin A.; Richman, Barak D. Health Affairs. Are Air Ambulances Truly Flying Out Of Reach? Surprise-Billing Policy And The Airline Deregulation Act . October 17, 2019.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2022 Employer Health Benefits Survey .

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Members of New Federal Advisory Committee Named to Help Improve Ground Ambulance Disclosure and Billing Practices for Consumers . December 13, 2022.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Advisory Committee on Ground Ambulance and Patient Billing (GAPB) .

Internal Revenue Service; Employee Benefits Security Administration; Health and Human Services Department. Requirements Related to Surprise Billing . August 26, 2022.

National Conference of State Legislatures. States Tackling "Balance Billing" Issue . July 2017.

By Elizabeth Davis, RN Elizabeth Davis, RN, is a health insurance expert and patient liaison. She's held board certifications in emergency nursing and infusion nursing.

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Medicare 101

Published: May 28, 2024

KFF Authors:

Juliette Cubanski

Meredith Freed

Nancy Ochieng

Alex Cottrill

Jeannie Fuglesten Biniek

Tricia Neuman

Juliette Cubanski , Meredith Freed , Nancy Ochieng , Alex Cottrill , Jeannie Fuglesten Biniek and Tricia Neuman

Table of Contents

What is medicare.

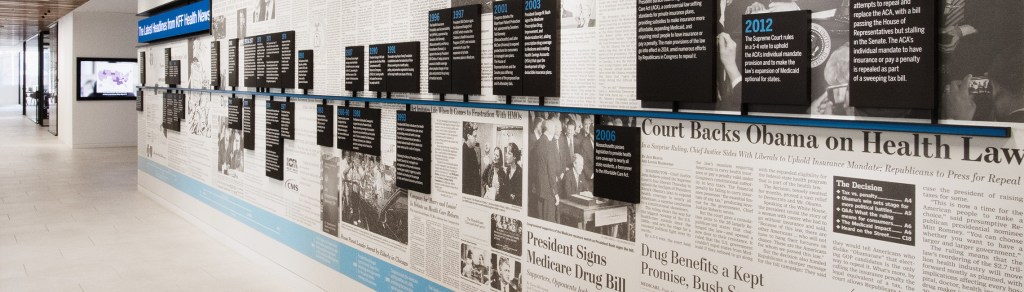

Medicare is the federal health insurance program established in 1965 under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act for people age 65 or older, regardless of income or medical history, and later expanded to cover people under age 65 with long-term disabilities. Today, Medicare provides health insurance coverage to 66 million people , including 58 million people age 65 or older and 8 million people under age 65. Medicare covers a comprehensive set of health care services, including hospitalizations, physician visits, and prescription drugs, along with post-acute care, skilled nursing facility care, home health care, hospice, and preventive services. People can choose to get coverage of Medicare benefits under traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage private plans.

Medicare spending comprised 12% of the federal budget in 2022 and 21% of national health care spending in 2021 . Funding for Medicare comes primarily from general revenues, payroll tax revenues, and premiums paid by beneficiaries. Over the longer term, the Medicare program faces financial pressures associated with higher health care costs, growing enrollment, and an aging population.

Who Is Covered by Medicare?

Most people become eligible for Medicare when they reach age 65, regardless of income, health status, or medical conditions. Residents of the U.S., including citizens and permanent residents, are eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A if they have worked at least 40 quarters (10 years) in jobs where they or their spouses paid Medicare payroll taxes and are at least 65 years old. People under age 65 who receive Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) payments generally become eligible for Medicare after a two-year waiting period. People diagnosed with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) become eligible for Medicare with no waiting period.

Medicare covers a diverse population in terms of demographics and health status, and this population is expected to grow larger and more diverse in the future as the U.S. population ages. Currently, most people with Medicare are White, female, and between the ages of 65 and 84 (Figure 1). The share of U.S. adults who are age 65 or older is projected to grow from 17% in 2020 to nearly a quarter of the nation’s total population in 2060, while people ages 80 and older will account for more than one-third of people 65 and older in 2060, up from one-quarter in 2020. As the U.S. population ages, the number of Medicare beneficiaries is projected to grow from around 63 million people in 2020 to just over 93 million people in 2060. The Medicare population will also grow more racially and ethnically diverse. By 2060, people of color will comprise close to half (47%) of the U.S. population ages 65 and older, nearly double the share in 2020 (25%).

While many Medicare beneficiaries enjoy good health, others live with health problems that affect their quality of life, including multiple chronic conditions, limitations in their activities of daily living, and cognitive impairments. In 2021, one-third (33%) of Medicare beneficiaries had four or more chronic conditions, more than a quarter (27%) had a functional impairment, and 17% had a cognitive impairment (Figure 2).

Most Medicare beneficiaries have limited financial resources, including income and assets. In 2023, half of all Medicare beneficiaries had incomes below $36,000 and savings below $103,800 per person. Median incomes for Medicare beneficiaries are lower among women than men, among people of color than White beneficiaries, and among beneficiaries under age 65 with disabilities than older beneficiaries (Figure 3).

What Does Medicare Cover and How Much Do People Pay for Medicare Benefits?

Benefits . Medicare covers a comprehensive set of medical care services, including hospital stays, physician visits, and prescription drugs. Medicare benefits are divided into four parts:

- Part A, also known as the Hospital Insurance (HI) program, covers inpatient care provided in hospitals and short-term stays in skilled nursing facilities, hospice care, post-acute home health care, and pints of blood received at a hospital or skilled nursing facility. An estimated 63.5 million people were enrolled in Part A in 2021. In 2021, 14% of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare had an inpatient hospital stay, while 8% used home health care services, and 4% had a skilled nursing facility stay (Figure 4). (Comparable utilization data for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage is not available.)

- Part B, the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) program, covers outpatient services such as physician visits, outpatient hospital care, and preventive services (e.g. mammography and colorectal cancer screening), among other medical benefits. An estimated 58 million people were enrolled in Part B in 2021. A larger share of beneficiaries use Part B services compared to Part A services. For example, in 2021, nearly 9 in 10 (88%) traditional Medicare beneficiaries used physician and other medical services covered under Part B and 66% used outpatient hospital services.

- Part C, more commonly referred to as the Medicare Advantage program, allows beneficiaries to enroll in a private plan, such as a health maintenance organization (HMO) or preferred provider organization (PPO), as an alternative to traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans cover all benefits under Medicare Part A, Part B, and, in most cases, Part D (Medicare’s outpatient prescription drug benefit), and typically offer extra benefits, such as dental services, eyeglasses, and hearing exams. In 2023, 31 million beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage , which is 51% of Medicare beneficiaries who are eligible to enroll in Medicare Advantage plans. (See “ What Is Medicare Advantage and How Is It Different From Traditional Medicare? ” for additional information.)

- Part D is a voluntary outpatient prescription drug benefit delivered through private plans that contract with Medicare, either stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or Medicare Advantage prescription drug (MA-PD) plans. In 2023, an estimated 50 million beneficiaries are enrolled in Part D . In 2021, nearly all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D (98%) used prescription drugs. (See “ What Is the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit? " for additional information.)

Although Medicare covers a comprehensive set of medical benefits, Medicare does not cover long-term care services. Additionally, coverage of vision services, dental care, and hearing aids is not part of the standard benefit, though most Medicare Advantage plans offer some coverage of these services .

Premiums and cost sharing . Medicare has varying premiums, deductibles, and coinsurance amounts that typically change yearly to reflect program cost changes.

- Part A: Most beneficiaries do not pay a monthly premium for Part A services, but are required to pay a deductible for inpatient hospitalizations ($1,632 in 2024). (People who are working contribute payroll taxes to Medicare and qualify for premium-free Part A at age 65 based on having paid 1.45% of their earnings over at least 40 quarters). Beneficiaries are generally subject to cost sharing for Part A benefits, including extended inpatient stays in a hospital ($408 per day for days 61-90 and $816 per day for days 91-150 in 2024) or skilled nursing facility ($204 per day for days 21-100 in 2024). There is no cost sharing for home health visits.

- Part B: Beneficiaries enrolled in Part B, including those in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, are generally required to pay a monthly premium ($174.70 in 2024). Beneficiaries with annual incomes greater than $103,000 for a single person or $206,000 for a married couple in 2024 pay a higher, income-related monthly Part B premium, ranging from $244.60 to $594. Approximately 8% of all Medicare beneficiaries are expected to pay income-related Part B premiums in 2024. Part B benefits are subject to an annual deductible ($240 in 2024), and most Part B services are subject to coinsurance of 20 percent.

- Part C: In addition to paying the Part B premium, Medicare Advantage enrollees may be charged a separate monthly premium for their Medicare Advantage plan, although 7 in 10 enrollees were in plans that charged no additional premium in 2023 . Medicare Advantage plans are generally prohibited from charging more than traditional Medicare, but vary in the deductibles and cost-sharing amounts they charge. Medicare Advantage plans may establish provider networks and require higher cost sharing for services received from non-network providers.

- Part D: Part D plans vary in terms of premiums, deductibles, and cost sharing. People in traditional Medicare who are enrolled in a separate stand-alone Part D plan generally pay a monthly Part D premium unless they qualify for full benefits through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program and are enrolled in a premium-free (benchmark) plan. In 2023, the average enrollment-weighted premium for stand-alone Part D plans was $40 per month , substantially higher than the enrollment-weighted average monthly portion of the premium for drug coverage in MA-PDs ($10 in 2023).

Sources of coverage . Most people with Medicare have some type of coverage that may protect them from unlimited out-of-pocket costs and may offer additional benefits, whether it’s coverage in addition to traditional Medicare or coverage from Medicare Advantage plans, which are required to have an out-of-pocket cap and typically offer supplemental benefits (Figure 5). However, based on KFF analysis of data from the 2021 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, 3 million people with Medicare have no additional coverage, which places them at risk of facing high out-of-pocket spending or going without needed medical care due to costs.

- Medicare Advantage plans now cover more than half of all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in both Part A and Part B, or 31 million people (in 2021, Medicare Advantage enrollment was just under half of beneficiaries, or around 27 million people). (See “What Is Medicare Advantage and How Is It Different From Traditional Medicare? ” for additional information.)

- Employer and union-sponsored plans provided some form of coverage to 15.2 million Medicare beneficiaries – one-quarter (26%) of Medicare beneficiaries overall in 2021. Of the total number of beneficiaries with employer coverage, 9.7 million beneficiaries had this coverage in addition to traditional Medicare (32% of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare), while 5.6 million beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage employer group plans. (These estimates exclude 5.2 million Medicare beneficiaries with Part A only in 2021, primarily because they or their spouse were active workers and had primary coverage from an employer plan.)

- Medicare supplement insurance, also known as Medigap, covered 2 in 10 (21%) Medicare beneficiaries overall, or 41% of those in traditional Medicare (12.5 million beneficiaries) in 2021. Medigap policies , sold by private insurance companies, fully or partially cover Medicare Part A and Part B cost-sharing requirements, including deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance.

- Medicaid, the federal-state program that provides health and long-term services and supports coverage to low-income people, was a source of coverage for 11 million Medicare beneficiaries with low incomes and modest assets in 2021 (19% of all Medicare beneficiaries), including 6.1 million enrolled in Medicare Advantage and 5.0 million in traditional Medicare. (This estimate is somewhat lower than KFF estimates published elsewhere due to different data sources and methods used.) For these beneficiaries, referred to as dual-eligible individuals, Medicaid typically pays the Medicare Part B premium and may also pay a portion of Medicare deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements. Most dual-eligible individuals are eligible for full Medicaid benefits, including long-term services and supports.

What Is Medicare Advantage and How Is It Different From Traditional Medicare?

Medicare Advantage, also known as Medicare Part C, allows beneficiaries to receive their Medicare benefits from a private health plan, such as an HMO or PPO. Medicare pays private insurers to provide Medicare-covered benefits (Part A and B, and often Part D) to enrollees. Virtually all Medicare Advantage plans include an out-of-pocket limit for benefits covered under Parts A and B, and most offer additional benefits not covered by traditional Medicare, such as vision, hearing, and dental. The average Medicare beneficiary can choose from 43 Medicare Advantage plans offered by eight insurance companies in 2024. These plans vary across many dimensions, including premiums, cost-sharing requirements, out-of-pocket limits, extra benefits, provider networks, prior authorization and referral requirements, denial rates, and prescription drug coverage.

More than half of all eligible Medicare beneficiaries (51% ), are currently enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, up from 25% in 2010 (Figure 6). The share of eligible Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans varies across states, ranging from 2% in Alaska to 60% in Alabama, Hawaii, and Michigan. Growth in Medicare Advantage enrollment is due to a number of factors. Medicare beneficiaries are attracted to Medicare Advantage due to the multitude of extra benefits, the simplicity of one-stop shopping (in contrast to traditional Medicare where beneficiaries might purchase a Part D plan and a Medigap plan), and the availability of plans with no premiums beyond the Part B premium, driven in part by the current payment system that generates high gross margins in this market (see “ How Does Medicare Pay Private Plans in Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D? ” for additional information) . Insurers market these plans aggressively, airing thousands of TV ads for Medicare Advantage during the Medicare open enrollment period. In some cases, Medicare beneficiaries have no choice but to be enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan for their retiree health benefits as some employers are shifting their retirees into these plans ; if they are dissatisfied with this option, they may have to give up retiree benefits altogether, although they would retain Medicare and have the option to choose traditional Medicare (potentially with a Medigap supplement).

There are several differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans can establish provider networks, the size of which can vary considerably for both physicians and hospitals , depending on the plan and the county where it is offered. These provider networks may also change over the course of the year. Medicare Advantage enrollees who seek care from an out-of-network provider may pay higher cost sharing or pay completely out of-pocket for their care. In contrast, traditional Medicare beneficiaries may see any provider that accepts Medicare and is accepting new patients. In 2019, 89% of non-pediatric office-based physicians accepted new Medicare patients , with little change over time. Only 1% of all non-pediatric physicians formally opted out of the Medicare program in 2023.

Medicare Advantage plans also often use tools to manage utilization and costs, such as requiring enrollees to receive prior authorization before a service will be covered and requiring enrollees to obtain a referral for specialists or mental health providers. In 2023, virtually all Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required prior authorization for some services, most often higher-cost services. Over 35 million prior authorization requests were submitted to Medicare Advantage plans in 2021 (Figure 7). Prior authorization and referrals to specialists are applied less frequently in traditional Medicare, with prior authorization generally applying to a limited set of services .

Medicare Advantage plans are required to use payments from the federal government that exceed their costs of covering Part A and B services ( known as rebates ) to provide supplemental benefits to enrollees, such as lower cost sharing, extra benefits not covered by traditional Medicare, or rebates toward Part B and/or Part D premiums. Examples of extra benefits include eyeglasses , hearing exams , preventive dental care , and gym memberships (Figure 8). ( See “ How Does Medicare Pay Private Plans in Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D? ” for a discussion of how Medicare pays Medicare Advantage plans ). [Additionally], Medicare Advantage plans must include a cap on out-of-pocket spending, providing protection from catastrophic medical expenses. Traditional Medicare does not have an out-of-pocket limit, though some have protection from catastrophic costs if they purchase a Medigap policy. (See “What Does Medicare Cover and How Much Do People Pay for Medicare Benefits?” for a brief discussion of Medigap .)

What Is the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit?

Medicare Part D , Medicare’s voluntary outpatient prescription drug benefit, was established by the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) and launched in 2006. Before the addition of the Part D benefit, Medicare did not cover the cost of outpatient prescription drugs. Under Part D, Medicare helps cover prescription drug costs through private plans that contract with Medicare to offer the Part D benefit to enrollees, which is unlike coverage of Part A and Part B benefits under traditional Medicare, and beneficiaries must enroll in a Part D plan if they want this benefit.

A total of 50.5 million people with Medicare are currently enrolled in plans that provide the Medicare Part D drug benefit, including plans open to everyone with Medicare (stand-alone prescription drug plans, or PDPs, and Medicare Advantage drug plans, or MA-PDs) and plans for specific populations (including retirees of a former employer or union and Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans, or SNPs). More than 13 million low-income beneficiaries receive extra help with their Part D plan premiums and cost sharing through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program (LIS).

For 2024, the average Medicare beneficiary has a choice of 21 stand-alone Part D plans and 36 Medicare Advantage drug plans . These plans vary in terms of premiums, deductibles and cost sharing, the drugs that are covered, any utilization management restrictions that apply, and pharmacy networks. People in traditional Medicare who are enrolled in a separate stand-alone Part D plan generally pay a monthly Part D premium unless they qualify for full benefits through the Part D LIS program and are enrolled in a premium-free (benchmark) plan. In 2023, the average enrollment-weighted premium for stand-alone Part D plans was $40 per month . In 2023, most stand-alone Part D plans included a deductible, averaging $411 . Plans generally impose a tiered structure to define cost-sharing requirements and cost-sharing amounts charged for covered drugs, typically charging lower cost-sharing amounts for generic drugs and preferred brands and higher amounts for non-preferred and specialty drugs, and a mix of flat dollar copayments and coinsurance (based on a percentage of a drug’s list price) for covered drugs.

The standard design of the Medicare Part D benefit currently has four distinct phases, where the share of drug costs paid by Part D enrollees, Part D plans, drug manufacturers, and Medicare varies. Based on changes in the Inflation Reduction Act, these shares will change in 2024 and 2025 (Figure 9). Most notably, the benefit includes catastrophic coverage for enrollees with high drug costs, a phase where Part D enrollees not receiving low-income subsidies have been responsible for paying 5% of their total drug costs. In 2024, costs in the catastrophic phase will change: the 5% coinsurance requirement for Part D enrollees will be eliminated and Part D plans will pay 20% of total drug costs in this phase instead of 15%. In 2025, out-of-pocket drug costs for Part D enrollees will be capped at $2,000. These changes are expected to help well over 1 million Part D enrollees with high drug costs each year.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 , signed into law by President Biden on August 16, 2022, includes several provisions to lower prescription drug costs for people with Medicare and reduce drug spending by the federal government, including several changes related to the Part D benefit. These provisions include (but are not limited to) (Figure 10):

- Requiring the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate the price of some drugs covered under Medicare, with negotiated prices first available for 10 Part D drugs in 2026 (and first available for Part B drugs in 2028). The law that established the Part D benefit included a provision known as the “ noninterference ” clause, which, to date, has prevented the HHS Secretary from being involved in price negotiations between drug manufacturers and pharmacies and Part D plan sponsors. In addition, the Secretary of HHS does not currently negotiate prices for drugs covered under Medicare Part B (administered by physicians).

- Adding a hard cap on out-of-pocket drug spending under Part D, which will phase in beginning in 2024, with a $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket spending in 2025. As noted above, under the original design of the Part D benefit, enrollees have had catastrophic coverage for high out-of-pocket drug costs, but there has been no limit on the total amount that beneficiaries pay out of pocket each year.

- Limiting the price of insulin products to no more than $35 per month in all Part D plans and in Part B and making adult vaccines covered under Part D available for free as of 2023. Until these provisions took effect, beneficiary costs for insulin and adult vaccines were subject to varying cost-sharing amounts.

- Expanding eligibility for full benefits under the Part D Low-Income Subsidy program in 2024, eliminating the partial LIS benefit for individuals with incomes between 135% and 150% of poverty. Beneficiaries who receive full LIS benefits pay no Part D premium or deductible and only modest copayments for prescription drugs until they reach the catastrophic threshold, at which point they face no additional cost sharing.

- Requiring drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to the federal government if prices for drugs covered under Part D and Part B increase faster than the inflation rate, with the initial period for measuring Part D drug price increases running from October 2022-September 2023. Previously, Medicare had no authority to limit annual price increases for drugs covered under Part B or Part D. Year-to-year drug price increases exceeding inflation are not uncommon and affect people with both Medicare and private insurance.

How Does Medicare Pay Hospitals, Physicians, and Other Providers in Traditional Medicare?

In 2023, Medicare is estimated to spend $436 billion on benefits covered under Part A and Part B for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Medicare pays providers in traditional Medicare using various payment systems depending on the setting of care (Figure 11).

Medicare relies on a number of different approaches when determining payments to providers for Part A and Part B services delivered to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. These providers include hospitals (for both inpatient and outpatient services), physicians, skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, and several other types of providers. Of the $436 billion in estimated spending on Medicare benefits covered under Part A and Part B in traditional Medicare in 2023, $144 billion (33%) is for hospital inpatient services and $62 billion (14%) is for hospital outpatient services, $72 billion (17%) is for services covered under the physician fee schedule, and $158 billion (36%) is for all other Part A or Part B services for beneficiaries in traditional Medicare.

Medicare uses prospective payment systems for most providers in traditional Medicare. These systems generally require that Medicare pre-determine a base payment rate for a given unit of service (e.g. a hospital stay, an episode of care, a particular service). Then, based on certain variables, such as the provider’s geographic location and the complexity of the patient receiving the service, Medicare adjusts its payment for each unit of service provided . Medicare updates payment rates annually for most payment systems to account for inflation adjustments.

The main features of hospital, physician, outpatient, and skilled nursing facility payment systems (altogether accounting for 70% of spending on Part A and Part B benefits in traditional Medicare) are described below:

- Inpatient hospitals (acute care) : Medicare pays hospitals per beneficiary discharge using the Inpatient Prospective Payment System . The rate for each discharge corresponds to one of over 750 different categories of diagnoses – called Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRGs), which reflect the principal diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, procedures performed, and other patient characteristics. DRGs that are likely to incur more intense levels of care and/or longer lengths of stay are assigned higher payments. Medicare’s payments to hospitals also account for a portion of hospitals’ capital and operating expenses.

- Medicare also makes additional payments to hospitals in particular situations. These include additional payments for rural or isolated hospitals that meet certain criteria. Further, Medicare makes additional payments to help offset costs incurred by hospitals that are not otherwise accounted for in the inpatient prospective payment system. These include add-on payments for treating a disproportionate share (DSH) of low-income patients, as well as for covering costs associated with care provided by medical residents, known as indirect medical education (IME). While not part of the Inpatient Prospective Payment System, Medicare also pays hospitals directly for the costs of operating residency programs, known as Graduate Medical Education (GME) payments.

- While not part of the Physician Fee Schedule, Medicare also pays for a limited number of drugs that physicians and other health care providers administer. For drugs administered by physicians, which are covered under Part B, Medicare reimburses providers based on a formula set at 106% of the Average Sales Price (ASP), which is the average price to all non-federal purchasers in the U.S, inclusive of rebates (other than rebates paid under the Medicaid program).

- Hospital outpatient departments : Medicare pays hospitals for ambulatory services provided in outpatient departments, using the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System , based on the classification of individual services into Ambulatory Payment Classifications (APC) with similar characteristics and expected costs. Final determination of Medicare payments for outpatient department services is complex. It incorporates both individual service payments and payments “packaged” with other services, partial hospitalization payments, as well as numerous exceptions, such as payments for new technologies. Medicare payment rates for services provided in hospital outpatient departments are typically higher than for similar services provided in physicians’ offices, and evidence indicates that providers have shifted the billing of services to higher-cost settings . There is bipartisan interest in proposals to expand so-called “site-neutral” payments, meaning that Medicare would align payment rates for the same service across settings.

- Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) : SNFs are freestanding or hospital-based facilities that provide post-acute inpatient nursing or rehabilitation services. Medicare pays SNFs based on the Skilled Nursing Facility Prospective Payment System , and payments to SNFs are determined using a base payment rate, adjusted for geographic differences in labor costs, case mix, and, in some cases, length of stay. Daily rates consider six care components – nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech–language pathology services, nontherapy ancillary services and supplies, and non–case mix (room and board services).

How Does Medicare Pay Private Plans in Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D?

Medicare Advantage . Medicare pays insurers offering Medicare Advantage plans a set monthly amount per enrollee. The payment is determined through an annual process in which plans submit “bids” for how much they estimate it will cost to provide benefits covered under Medicare Parts A and B for an average beneficiary. The bid is compared to a county “benchmark”, which is the maximum amount the federal government will pay for a Medicare Advantage enrollee and is a percentage of estimated spending in traditional Medicare in the same county, ranging from 95 percent in high-cost counties to 115 percent in low-cost counties. When the bid is below the benchmark in a given county, plans receive a portion of the difference (“the rebate”), which they must use to lower cost sharing, pay for extra benefits, or reduce enrollees’ Part B or Part D premiums. Payments to plans are risk adjusted, based on the health status and other characteristics of enrollees, including age, sex, and Medicaid enrollment. In addition, Medicare adopted a quality bonus program that increases the benchmark for plans that receive at least four out of five stars under the quality rating system, which increases plan payments.

Generally, Medicare pays more to private Medicare Advantage plans for enrollees than their costs would be in traditional Medicare. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) reports that while it costs Medicare Advantage insurers 82% of what it costs traditional Medicare to pay for Medicare-covered services, plans receive payments from CMS that are 122% of spending for similar beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, on average. The higher spending stems from features of the formula used to determine payments to Medicare Advantage plans, including setting benchmarks above traditional Medicare spending in half of counties and higher benchmarks due to the quality bonus program, resulting in bonus payments of nearly $13 billion in 2023 . This amount is more than four times greater than spending on bonus payments in 2015 (Figure 12).

The higher spending in Medicare Advantage is also related to the impact of coding intensity, where Medicare Advantage enrollees look sicker than they would if they were in traditional Medicare, resulting in plans receiving higher risk adjustments to their monthly per person payments, translating to an estimated $83 billion in excess payments to plans in 2024 .