Executive Branch of Government in the US Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Changes in constitutional powers and functions

Economic changes, public welfare, works cited.

US Executive is one of the primary constituent of the centralized government. It consists of numerous offices that play significant roles in running the branch. The President’s office, his vice and some of the departmental offices are some of the most prime administrative offices in the branch (Brown and Graham, 1). Since the branch was formed, many changes have taken place, in the effort of improving its efficiency.

As years passes by, the US constitution keep on changing following the numerous modifications done by the congress (the law-making body). This has immensely affected the roles and powers of the executive branch, since the offices have to meet their constitutional job requirements. Furthermore, change in legal functions alters the structures the executive branch, since they will have to introduce other offices, to assist in meeting the newly introduced requirements.

For instance, some of the executive functions and terms were altered by the congress under the twentieth amendment. The interlude between election and inaugural ceremony was altered, and thus the president alongside with his vice had to surrender their offices in January 20 th (noon), the year after general elections. This is because; initially, the period between election and inauguration was quite stretched i.e. approximately four months after voting.

Furthermore, the amendment also stated that, incase the presidential-elect passes away, then the vice president elect will assume the president’s position and thus sworn as the new president of US. There were also some modifications under the 22 nd amendment that extensively affected the executive offices (Wright, 64). The amendment transformed the number of times a citizen can hold a presidential office; the number was changed to a maximum of two terms in office (Findlaw).

The succession of the president was changed, in one of the amendment clause i.e. the vice will assume the president’s role, incase the president quits his position or dies. Furthermore, the amendment states that any position in the vice’s office will be appointed by the president; however, the appointee shall not assume the office until he or she is approved by the congress.

A country’s economy keeps on shifting from one position to another thus influencing various crucial institution and bureaus, including the executive branches.

In the past year, United States experienced several economic changes; for instance, the recessions, depressions, crunches and other similar economic difficulties. This experience has made United States alter some of its executive departments, as a strategy to curb the economic changes. As a result, some executive departments were removed, while others introduced; some were modified while others replaced.

For instance, commerce and labor department were split to form two autonomous departments (Infoplease). This move was an economic strategy for the improvement of commerce in the country i.e. to enhance local and international trade. Being a victim of several hash economic environment, the US government has incorporated several junior offices in their departments that assist in projecting its business environment.

Education department was formed to operate independently, after the amalgamation of several learning programs, from different bureaus. This change was effected in the late seventies as a progress to provide quality education to all students, regardless of their backgrounds.

Following the terrorist attack in 2001, several offices were merged to form a sovereign protection department i.e. the homeland security department (infoplease). The prime function of this department was to up the security of United States, and also to protect their citizens against unnecessary threats. As early as 1939, the federal security agency was changed following the demands to improve human healthiness and well being.

The Agency was transformed to a healthcare department i.e. health and human services department, which was expected to up the standards of health in the country. Some of the numerous function of this health care department was to provide health services to all citizens regardless of their background, abilities or situation; finance healthcare institutions such as Medicaid; conduct healthcare researches and so on.

Early in the 60’s, the united states were subjected to numerous housing challenges especially in urban centers. This pressured the government to create an executive department that would solely address matters pertaining housing and the growth of cities.

Consequently, a department in the name of housing and urban development was created as a substitute for the home finance and housing sub-division. The department was formed to offer several services to the ordinary citizens i.e. offer inexpensive housing services; uphold community development and many more others (Infoplease).

The department of labor underwent several transitions before it finally stood out as a sovereign department. Initially, labor functioned as an agency under a certain executive department prior to its operation in the labor and commerce department (Henry, 375). Early in the 90’s, labor was separated from the department and thus operated as an autonomous executive department. The change was influenced by the undying effort of guarding workers against overexploitation.

Several executive offices have been altered following the government’s attempt to regulate the activities of certain crucial offices. For instance, the national military bureau was transformed following the need to regulate its mandate. The name of the bureau was transformed and named as the department of defense, which was accompanied by numerous changes in its functions.

Some of the functions dispensed to this department included flood control; the control and regulation of the navy, marine and other such like agencies. Executive department such as the department of agriculture was established following the need to regulate food prices and input costs.

The need to regulate commerce in United States is one of the numerous factors that led to the split of labor and commerce department. Several aspects such as local trade, international trade, and technological growth had to be regulated adequately. However, this proved tricky without the sovereign existence of commerce department. As a result, the department of trade and labor was split to form two autonomous departments.

Over the years, United States has grown technologically, with the introduction of numerous ideologies and hi-tech devices. However, these inventions and innovations possess a number of negative and positive impacts, which can influence a country in various capacities. In the attempt to control these impacts, the executive experienced a stretch in their duties and thus increasing their scope. In other words, the executive had to perform extra roles due to technological advancements i.e. to develop policies that regulate their use.

The advances in technology, which are eventually incorporated in different departments, have immensely influenced the executive structures. Several offices have been created as a solution for the management of these high-tech equipments in different executive departments. For instance, the defense department has several technological departments that contain several offices responsible for developing and managing technical weapons.

The functions and names of offices in the executive branch have changed over the years, due to several factors. Some of the reason that influenced changes in departmental names and operations include economic changes, technological changes, a shift in public welfare demands and the need for office regulations. Some of the offices in the branch, which have grown and changed over the years, include the president office, executive departments and the vice president office.

Barrett, Henry. The President’s Cabinet, Studies in the Origin, Formation and Structure of an American Institution . Charleston: BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009 375.

Brown, Elizabeth and Graham, David. Leading the executive branch: strategies and options for achieving success . Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. 2007 1.

Findlaw. Amendment to the constitution of United States of America . London: Thomson Reuters business. 2010. Web. Available at: https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendments.html

Infoplease. Executive department . Berkeley: Pearson education 2007. Web. Available at: https://www.infoplease.com/history-and-government/executive-departments-and-agencies/executive-departments

Wright, John. The New York times Almanac 2002 . New York: Routledge. 2001 64.

- The Sovereign State Concept in Political Science

- The U.S. and European Sovereign Debt Levels

- Altered State of Consciousness

- Questioning and Criticizing Supreme Court Nominees

- "India Asks, Should Food Be a Right for the Poor?" by Yardley Jim

- Challenges of the Arab Gulf States

- The US Healthcare System: A Critical Discussion of Underlying Issues Using Economic Perspectives

- State and Local Government

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 5). Executive Branch of Government in the US. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-executive-branch/

"Executive Branch of Government in the US." IvyPanda , 5 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/the-executive-branch/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Executive Branch of Government in the US'. 5 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Executive Branch of Government in the US." July 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-executive-branch/.

1. IvyPanda . "Executive Branch of Government in the US." July 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-executive-branch/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Executive Branch of Government in the US." July 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-executive-branch/.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- The Interior Lowlands and their upland fringes

- The Appalachian Mountain system

- The Atlantic Plain

- The Western Cordillera

- The Western Intermontane Region

- The Eastern systems

- The Pacific systems

- Climatic controls

- The change of seasons

- The Humid East

- The Humid Pacific Coast

- The Dry West

- The Humid–Arid Transition

- The Western mountains

- Animal life

- Early models of land allocation

- Creating the national domain

- Distribution of rural lands

- Patterns of farm life

- Regional small-town patterns

- Weakening of the agrarian ideal

- Impact of the motor vehicle

- Reversal of the classic rural dominance

- Classic patterns of siting and growth

- New factors in municipal development

- The new look of the metropolitan area

- Individual and collective character of cities

- The supercities

- The hierarchy of culture areas

- New England

- The Midland

- The Midwest

- The problem of “the West”

- Ethnic European Americans

- African Americans

- Asian Americans

- Middle Easterners

- Native Americans

- Religious groups

- Immigration

- Strengths and weaknesses

- Labour force

- Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

- Biological resources

- Manufacturing

- Foreign trade

- Roads and railroads

- Water and air transport

The executive branch

The legislative branch, the judicial branch.

- State and local government

- Voting and elections

- Money and campaigns

- Political parties

- National security

- Domestic law enforcement

- Health and welfare

- The visual arts and postmodernism

- The theatre

- Motion pictures

- Popular music

- The European background

- The New England colonies

- The middle colonies

- The Carolinas and Georgia

- Imperial organization

- Political growth

- Population growth

- Economic growth

- Land, labour, and independence

- Colonial culture

- From a city on a hill to the Great Awakening

- Colonial America, England, and the wider world

- The Native American response

- The tax controversy

- Constitutional differences with Britain

- The Continental Congress

- The American Revolutionary War

- Treaty of Paris

- Problems before the Second Continental Congress

- State politics

- The Constitutional Convention

- The social revolution

- Religious revivalism

- The Federalist administration and the formation of parties

- The Jeffersonian Republicans in power

- Madison as president and the War of 1812

- The Indian-American problem

- Effects of the War of 1812

- National disunity

- Transportation revolution

- Beginnings of industrialization

- Birth of American Culture

- Education and the role of women

- The democratization of politics

- The Jacksonians

- The major parties

- Minor parties

- Abolitionism

- Support of reform movements

- Religious-inspired reform

- Westward expansion

- Attitudes toward expansionism

- Sectionalism and slavery

- Popular sovereignty

- Polarization over slavery

- The coming of the war

- Moves toward emancipation

- Sectional dissatisfaction

- Foreign affairs

- Lincoln’s plan

- The Radicals’ plan

- Johnson’s policy

- “Black Codes”

- Civil rights legislation

- The South during Reconstruction

- The Ulysses S. Grant administrations, 1869–77

- The era of conservative domination, 1877–90

- Jim Crow legislation

- Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

- Westward migration

- Urban growth

- The mineral empire

- The open range

- The expansion of the railroads

- Indian policy

- The dispersion of industry

- Industrial combinations

- Foreign commerce

- Formation of unions

- The Haymarket Riot

- The Rutherford B. Hayes administration

- The administrations of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur

- The surplus and the tariff

- The public domain

- The Interstate Commerce Act

- The election of 1888

- The Sherman Antitrust Act

- The silver issue

- The McKinley tariff

- The agrarian revolt

- The Populists

- The election of 1892

- Cleveland’s second term

- Economic recovery

- The Spanish-American War

- The new American empire

- The Open Door in the Far East

- Building the Panama Canal and American domination in the Caribbean

- Origins of progressivism

- Urban reforms

- Reform in state governments

- Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive movement

- The Republican insurgents

- The 1912 election

- The New Freedom and its transformation

- Woodrow Wilson and the Mexican Revolution

- Loans and supplies for the Allies

- German submarine warfare

- Arming for war

- Break with Germany

- Mobilization

- America’s role in the war

- Wilson’s vision of a new world order

- The Paris Peace Conference and the Versailles Treaty

- The fight over the treaty and the election of 1920

- Postwar conservatism

- Peace and prosperity

- New social trends

- The Great Depression

- Agricultural recovery

- Business recovery

- The second New Deal and the Supreme Court

- The culmination of the New Deal

- An assessment of the New Deal

- The road to war

- War production

- Financing the war

- Social consequences of the war

- The 1944 election

- The new U.S. role in world affairs

- The Truman Doctrine and containment

- Postwar domestic reorganization

- The Red Scare

- The Korean War

- Peace, growth, and prosperity

- Domestic issues

- World affairs

- An assessment of the postwar era

- The New Frontier

- The Great Society

- The civil rights movement

- Latino and Native American activism

- Social changes

- The Vietnam War

- Domestic affairs

- The Watergate scandal

- The Gerald R. Ford administration

- Domestic policy

- The Ronald Reagan administration

- The George H.W. Bush administration

- The Bill Clinton administration

- The George W. Bush administration

- Election and inauguration

- Tackling the “Great Recession,” the “Party of No,” and the emergence of the Tea Party movement

- Negotiating health care reform

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)

- Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Military de-escalation in Iraq and escalation in Afghanistan

- The 2010 midterm elections

- WikiLeaks, the “Afghan War Diary,” and the “Iraq War Log”

- The repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” the ratification of START, and the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords

- Budget compromise

- The Arab Spring, intervention in Libya, and the killing of Osama bin Laden

- The debt ceiling debate

- The failed “grand bargain”

- Raising the debt ceiling, capping spending, and the efforts of the “super committee”

- Occupy Wall Street, withdrawal from Iraq, and slow economic recovery

- Deportation policy changes, the immigration law ruling, and sustaining Obamacare’s “individual mandate”

- The 2012 presidential campaign, a fluctuating economy, and the approaching “fiscal cliff”

- The Benghazi attack and Superstorm Sandy

- The 2012 election

- The Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting

- “Sequester” cuts, the Benghazi furor, and Susan Rice on the hot seat

- The IRS scandal, the Justice Department’s AP phone records seizure, and Edward Snowden’s leaks

- Removal of Mohammed Morsi, Obama’s “red line” in Syria, and chemical weapons

- The decision not to respond militarily in Syria

- The 2013 government shutdown

- The Obamacare rollout

- The Iran nuclear deal, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, and the Ukraine crisis

- The rise of ISIL (ISIS), the Bowe Bergdahl prisoner swap, and imposition of stricter carbon emission standards

- The child migrant border surge, air strikes on ISIL (ISIS), and the 2014 midterm elections

- Normalizing relations with Cuba, the USA FREEDOM Act, and the Office of Personnel Management data breach

- The Ferguson police shooting, the death of Freddie Gray, and the Charleston church shooting

- Same-sex marriage and Obamacare Supreme Court rulings and final agreement on the Iran nuclear deal

- New climate regulations, the Keystone XL pipeline, and intervention in the Syrian Civil War

- The Merrick Garland nomination and Supreme Court rulings on public unions, affirmative action, and abortion

- The Orlando nightclub shooting, the shooting of Dallas police officers, and the shootings in Baton Rouge

- The campaign for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination

- The campaign for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination

- Hillary Clinton’s private e-mail server, Donald Trump’s Access Hollywood tape, and the 2016 general election campaign

- Trump’s victory and Russian interference in the presidential election

- “America First,” the Women’s Marches, Trump on Twitter, and “fake news”

- Scuttling U.S. participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, reconsidering the Keystone XL pipeline, and withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement

- ICE enforcement and removal operations

- The travel ban

- Pursuing “repeal and replacement” of Obamacare

- John McCain’s opposition and the failure of “skinny repeal”

- Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, the air strike on Syria, and threatening Kim Jong-Un with “fire and fury”

- Violence in Charlottesville, the dismissal of Steve Bannon, the resignation of Michael Flynn, and the investigation of possible collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign

- Jeff Session’s recusal, James Comey’s firing, and Robert Mueller’s appointment as special counsel

- Hurricanes Harvey and Maria and the mass shootings in Las Vegas, Parkland, and Santa Fe

- The #MeToo movement, the Alabama U.S. Senate special election, and the Trump tax cut

- Withdrawing from the Iran nuclear agreement, Trump-Trudeau conflict at the G7 summit, and imposing tariffs

- The Trump-Kim 2018 summit, “zero tolerance,” and separation of immigrant families

- The Supreme Court decision upholding the travel ban, its ruling on Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, No. 16-1466 , and the retirement of Anthony Kennedy

- The indictment of Paul Manafort, the guilty pleas of Michael Flynn and George Papadopoulos, and indictments of Russian intelligence officers

- Cabinet turnover

- Trump’s European trip and the Helsinki summit with Vladimir Putin

- The USMCA trade agreement, the allegations of Christine Blasey Ford, and the Supreme Court confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh

- Central American migrant caravans, the pipe-bomb mailings, and the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting

- The 2018 midterm elections

- The 2018–19 government shutdown

- Sessions’s resignation, choosing a new attorney general, and the ongoing Mueller investigation

- The Mueller report

- The impeachment of Donald Trump

- The coronavirus pandemic

- The killing of George Floyd and nationwide racial injustice protests

- The 2020 U.S. election

- The COVID-19 vaccine rollout, the Delta and Omicron variants, and the American Rescue Plan Act

- Economic recovery, the American Rescue Plan Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the failure of Build Back Better

- Stalled voting rights legislation, the fate of the filibuster, and the appointment of Ketanji Brown Jackson to the U.S. Supreme Court

- Foreign affairs: U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

- The Buffalo and Uvalde shootings, overturning Roe v. Wade , and the January 6 attack hearings

- Presidents of the United States

- Vice presidents of the United States

- First ladies of the United States

- State maps, flags, and seals

- State nicknames and symbols

- How did Ernest Hemingway influence others?

- What was Ernest Hemingway’s childhood like?

- When did Ernest Hemingway die?

- What did Martin Luther King, Jr., do?

- What is Martin Luther King, Jr., known for?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Library of Congress - The Beginnings of American Railroads and Mapping

- HistoryNet - States’ Rights and The Civil War

- EH.net - Urban Mass Transit In The United States

- Encyclopedia of Alabama - States' Rights

- Central Intelligence Agency - The World Factbook - United States

- U.S. Department of State - Office of the Historian - The United States and the French Revolution

- American Battlefield Trust - Slavery in the United States

- United States - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- United States - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The executive branch is headed by the president , who must be a natural-born citizen of the United States, at least 35 years old, and a resident of the country for at least 14 years. A president is elected indirectly by the people through the Electoral College system to a four-year term and is limited to two elected terms of office by the Twenty-second Amendment (1951). The president’s official residence and office is the White House , located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. in Washington, D.C. The formal constitutional responsibilities vested in the presidency of the United States include serving as commander in chief of the armed forces; negotiating treaties; appointing federal judges, ambassadors, and cabinet officials; and acting as head of state. In practice, presidential powers have expanded to include drafting legislation, formulating foreign policy , conducting personal diplomacy, and leading the president’s political party .

The members of the president’s cabinet —the attorney general and the secretaries of State , Treasury , Defense , Homeland Security , Interior , Agriculture , Commerce , Labor , Health and Human Services , Housing and Urban Development , Transportation , Education , Energy , and Veterans Affairs —are appointed by the president with the approval of the Senate; although they are described in the Twenty-fifth Amendment as “the principal officers of the executive departments,” significant power has flowed to non-cabinet-level presidential aides, such as those serving in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the Council of Economic Advisers , the National Security Council (NSC), and the office of the White House Chief of Staff; cabinet-level rank may be conferred to the heads of such institutions at the discretion of the president. Members of the cabinet and presidential aides serve at the pleasure of the president and may be dismissed by him at any time.

Recent News

The executive branch also includes independent regulatory agencies such as the Federal Reserve System and the Securities and Exchange Commission . Governed by commissions appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate (commissioners may not be removed by the president), these agencies protect the public interest by enforcing rules and resolving disputes over federal regulations. Also part of the executive branch are government corporations (e.g., the Tennessee Valley Authority , the National Railroad Passenger Corporation [ Amtrak ], and the U.S. Postal Service), which supply services to consumers that could be provided by private corporations, and independent executive agencies (e.g., the Central Intelligence Agency , the National Science Foundation , and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration ), which comprise the remainder of the federal government.

The U.S. Congress , the legislative branch of the federal government, consists of two houses: the Senate and the House of Representatives . Powers granted to Congress under the Constitution include the power to levy taxes, borrow money, regulate interstate commerce , impeach and convict the president, declare war, discipline its own membership, and determine its rules of procedure.

With the exception of revenue bills, which must originate in the House of Representatives, legislative bills may be introduced in and amended by either house, and a bill—with its amendments—must pass both houses in identical form and be signed by the president before it becomes law. The president may veto a bill, but a veto can be overridden by a two-thirds vote of both houses. The House of Representatives may impeach a president or another public official by a majority vote; trials of impeached officials are conducted by the Senate, and a two-thirds majority is necessary to convict and remove the individual from office. Congress is assisted in its duties by the General Accounting Office (GAO), which examines all federal receipts and expenditures by auditing federal programs and assessing the fiscal impact of proposed legislation, and by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), a legislative counterpart to the OMB, which assesses budget data, analyzes the fiscal impact of alternative policies, and makes economic forecasts.

The House of Representatives is chosen by the direct vote of the electorate in single-member districts in each state. The number of representatives allotted to each state is based on its population as determined by a decennial census ; states sometimes gain or lose seats, depending on population shifts. The overall membership of the House has been 435 since the 1910s, though it was temporarily expanded to 437 after Hawaii and Alaska were admitted as states in 1959. Members must be at least 25 years old, residents of the states from which they are elected, and previously citizens of the United States for at least seven years. It has become a practical imperative—though not a constitutional requirement—that a member be an inhabitant of the district that elects him. Members serve two-year terms, and there is no limit on the number of terms they may serve. The speaker of the House , who is chosen by the majority party, presides over debate, appoints members of select and conference committees, and performs other important duties; he is second in the line of presidential succession (following the vice president). The parliamentary leaders of the two main parties are the majority floor leader and the minority floor leader. The floor leaders are assisted by party whips , who are responsible for maintaining contact between the leadership and the members of the House. Bills introduced by members in the House of Representatives are received by standing committees, which can amend , expedite, delay, or kill legislation. Each committee is chaired by a member of the majority party, who traditionally attained this position on the basis of seniority, though the importance of seniority has eroded somewhat since the 1970s. Among the most important committees are those on Appropriations, Ways and Means, and Rules. The Rules Committee, for example, has significant power to determine which bills will be brought to the floor of the House for consideration and whether amendments will be allowed on a bill when it is debated by the entire House.

Each state elects two senators at large. Senators must be at least 30 years old, residents of the state from which they are elected, and previously citizens of the United States for at least nine years. They serve six-year terms, which are arranged so that one-third of the Senate is elected every two years. Senators also are not subject to term limits. The vice president serves as president of the Senate, casting a vote only in the case of a tie, and in his absence the Senate is chaired by a president pro tempore, who is elected by the Senate and is third in the line of succession to the presidency. Among the Senate’s most prominent standing committees are those on Foreign Relations, Finance, Appropriations, and Governmental Affairs. Debate is almost unlimited and may be used to delay a vote on a bill indefinitely. Such a delay, known as a filibuster , can be ended by three-fifths of the Senate through a procedure called cloture . Treaties negotiated by the president with other governments must be ratified by a two-thirds vote of the Senate. The Senate also has the power to confirm or reject presidentially appointed federal judges, ambassadors, and cabinet officials.

The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court of the United States , which interprets the Constitution and federal legislation. The Supreme Court consists of nine justices (including a chief justice ) appointed to life terms by the president with the consent of the Senate. It has appellate jurisdiction over the lower federal courts and over state courts if a federal question is involved. It also has original jurisdiction (i.e., it serves as a trial court) in cases involving foreign ambassadors, ministers, and consuls and in cases to which a U.S. state is a party.

Most cases reach the Supreme Court through its appellate jurisdiction. The Judiciary Act of 1925 provided the justices with the sole discretion to determine their caseload. In order to issue a writ of certiorari , which grants a court hearing to a case, at least four justices must agree (the “Rule of Four”). Three types of cases commonly reach the Supreme Court: cases involving litigants of different states, cases involving the interpretation of federal law, and cases involving the interpretation of the Constitution. The court can take official action with as few as six judges joining in deliberation, and a majority vote of the entire court is decisive; a tie vote sustains a lower-court decision. The official decision of the court is often supplemented by concurring opinions from justices who support the majority decision and dissenting opinions from justices who oppose it.

Because the Constitution is vague and ambiguous in many places, it is often possible for critics to fault the Supreme Court for misinterpreting it. In the 1930s, for example, the Republican-dominated court was criticized for overturning much of the New Deal legislation of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt . In the area of civil rights , the court has received criticism from various groups at different times. Its 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , which declared school segregation unconstitutional, was harshly attacked by Southern political leaders, who were later joined by Northern conservatives . A number of decisions involving the pretrial rights of prisoners, including the granting of Miranda rights and the adoption of the exclusionary rule , also came under attack on the ground that the court had made it difficult to convict criminals. On divisive issues such as abortion , affirmative action , school prayer, and flag burning, the court’s decisions have aroused considerable opposition and controversy, with opponents sometimes seeking constitutional amendments to overturn the court’s decisions.

At the lowest level of the federal court system are district courts ( see United States District Court ). Each state has at least one federal district court and at least one federal judge. District judges are appointed to life terms by the president with the consent of the Senate. Appeals from district-court decisions are carried to the U.S. courts of appeals ( see United States Court of Appeals ). Losing parties at this level may appeal for a hearing from the Supreme Court. Special courts handle property and contract damage suits against the United States ( United States Court of Federal Claims ), review customs rulings (United States Court of International Trade), hear complaints by individual taxpayers (United States Tax Court) or veterans (United States Court of Appeals for Veteran Claims), and apply the Uniform Code of Military Justice ( United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces ).

U.S. Presidency

The power of the executive branch of the U.S. government has grown substantially since its inception, continuing and expanding its influence on all facets of American political life. The impact of the U.S. presidency has evolved particularly in relation to civil rights, foreign relations and the handling of war and peace. The influence of the media has altered presidential policy. In this Vanderbilt University Special Collections and Archives exhibit, we use artifacts to convey the challenges and triumphs of the American presidency and its extensive role in American politics.

Expanding Power of the Executive Branch

Brennan Ferrington, Curator

![history of the executive branch essay [Abraham Lincoln & Franklin Delano Roosevelt], composite](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/us-presidency/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2021/12/Presidential-Power-Collage-1200-640x480.png)

[Abraham Lincoln & Franklin Delano Roosevelt], composite

This composite image of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano...

Treaty of Versailles

Right to Left: Woodrow Wilson, Georges Clemenceau, David Lloyd...

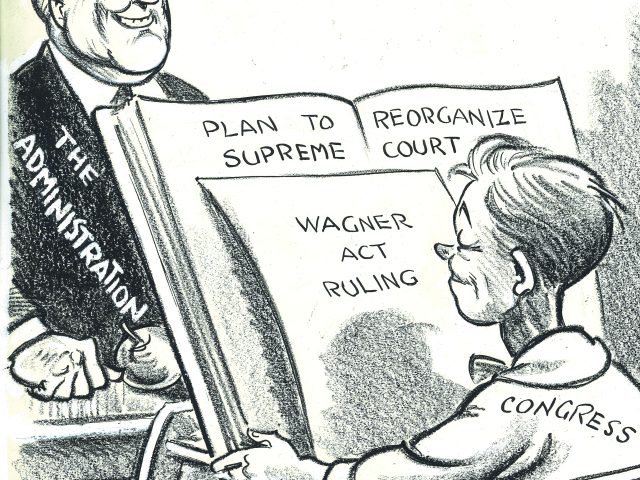

No Telling What He’ll Learn

In this cartoon, FDR teaches Congress the power of his plan to...

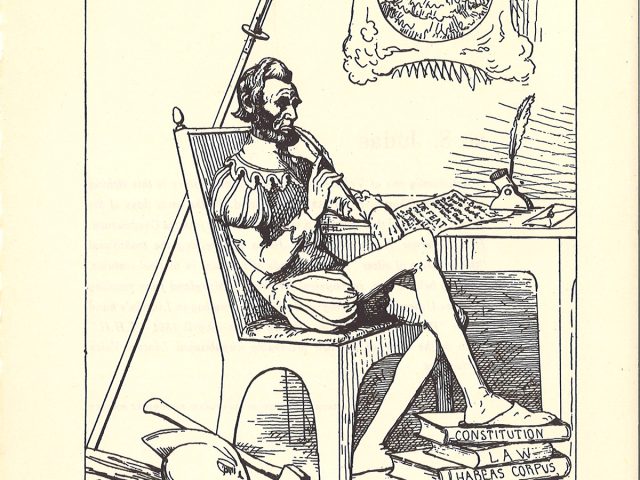

The Knight of Rueful Countenance

Caricaturist Adalbert Volck created several political cartoons...

7a. The Evolution of the Presidency

The 21st Century dawned on a very different presidency than the one created at the end of the 1700s. Constitutional provisions limited the early presidency, although the personalities of the first three — George Washington , John Adams , and Thomas Jefferson — shaped it into a more influential position by the early 1800s. However, throughout the 1800s until the 1930s, Congress was the dominant branch of the national government. Then, throughout the rest of the 20th Century, the balance of power shifted dramatically, so that the executive branch currently has at least equal power to the legislative branch. How did this shift happen?

Constitutional Qualifications and Powers

Article II of the Constitution defines the qualifications, benefits, and powers of the presidency. The President must be at least 35 years old, and must have resided in the United States for no fewer than 14 years. Presidents must be "natural born" citizens. The Constitution states that the President should be paid a "compensation" that cannot be increased or decreased during a term. Congress determines the salary, which increased in 2001 to $400,000, doubling the salary that was set back in the 1960s.

Article II of the Constitution

The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

[The Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by Ballot for two Persons, of whom one at least shall not be an Inhabitant of the same State with themselves. And they shall make a List of all the Persons voted for, and of the Number of Votes for each; which List they shall sign and certify, and transmit sealed to the Seat of the Government of the United States, directed to the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall, in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the Certificates, and the Votes shall then be counted. The Person having the greatest Number of Votes shall be the President, if such Number be a Majority of the whole Number of Electors appointed; and if there be more than one who have such Majority, and have an equal Number of Votes, then the House of Representatives shall immediately choose by Ballot one of them for President; and if no Person have a Majority, then from the five highest on the List the said House shall in like Manner choose the President. But in choosing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote; A quorum for this Purpose shall consist of a Member or Members from two thirds of the States, and a Majority of all States shall be necessary to a Choice. In every Case, after the Choice of the President, the Person having the greatest Number of Votes of the Electors shall be the Vice President. But if there should remain two or more who have equal Votes, the Senate shall choose from them by Ballot the Vice President.]*

*Changed by the Twelfth Amendment.

The Congress may determine the Time of choosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

No Person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President; neither shall any person be eligible to that Office who shall not have attained to the Age of thirty five Years, and been fourteen Years a Resident within the United States.

[In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.]*

*Changed by the Twenty-fifth Amendment.

The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive within that Period any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them.

Before he enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation:--"I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.''

The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other officers of the United States, whose appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by law: but the Congress may by Law vest the appointment of such inferior officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments.

The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session.

He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient; he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper; he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.

The Constitution assigned the following powers to the President:

The Strengthening of the Presidency

Because the Constitution gave the President such limited power, Congress dominated the executive branch until the 1930s. With only a few exceptions, Presidents played second fiddle to Congress for many years. However, those exceptions — Andrew Jackson , Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson — provided the basis for the turning point that came with the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s.

Andrew Jackson , greatly loved by the masses, used his image and personal power to strengthen the developing party system by rewarding loyal followers with presidential appointments. Jackson also made extensive use of the veto and asserted national power by facing down South Carolina's nullification of a federal tariff law. Jackson vetoed more bills than the six previous Presidents combined.

Abraham Lincoln assumed powers that no President before him had claimed, partly because of the emergency created by the Civil War (1861-1865). He suspended habeas corpus (the right to an appearance in court), and jailed people suspected of disloyalty. He ignored Congress by expanding the size of the army and ordering blockades of southern ports without the consent of Congress.

Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson each expanded the powers of the presidency. Roosevelt worked closely with Congress, sending it messages defining his legislative powers. He also took the lead in developing the international power of the United States. Wilson helped formulate bills that Congress considered, and World War I afforded him the opportunity to take a leading role in international affairs.

Franklin Roosevelt, who was elected four times to the presidency, led the nation through the crises of the Great Depression and World War II . Roosevelt gained power through his New Deal programs to regulate the economy, and the war required that he lead the country in foreign affairs as well.

So, the powers of the modern presidency have been shaped by a combination of constitutional and evolutionary powers. The forceful personalities of strong Presidents have expanded the role far beyond the greatest fears of the antifederalists of the late 1700s.

Report broken link

If you like our content, please share it on social media!

Copyright ©2008-2022 ushistory.org , owned by the Independence Hall Association in Philadelphia, founded 1942.

THE TEXT ON THIS PAGE IS NOT PUBLIC DOMAIN AND HAS NOT BEEN SHARED VIA A CC LICENCE. UNAUTHORIZED REPUBLICATION IS A COPYRIGHT VIOLATION Content Usage Permissions

The Origin of the Executive

By natalie bolton and gordon lloyd, introduction:.

To assist teachers in teaching the founding of the U.S. government, Professor Gordon Lloyd has created a website in collaboration with the Ashbrook Center at Ashland University on the American Founding . In an effort to assist students in understanding how the executive and judicial branches of government were established, two lesson plans have been created that combine content from websites created by Gordon Lloyd that tell the story of the founding. Students will review several primary source documents including Articles and Amendments of the U.S. Constitution and Federalist and Antifederalist papers to understand and explain the origins of the executive and judicial branches of the United States. The following lesson will explore the origin of the Executive using primary sources from Madison’s Notes on the Convention , Article II of the United States Constitution , Amendment XXII , Old Whig V , Cato IV , Federalist 70 and Federalist 71 . This lesson has been written as a Historical Scene Investigation (HSI). The HSI instructional model consists of the following four steps: Becoming a Detective Investigating the Evidence Searching for Clues Cracking the Case In the “ Becoming a Detective ” stage, students are introduced to the historical scene under investigation. Here background information and context are provided for the students. Students are then presented with an Engaging Question to guide their inquiry. Finally, students are presented with a task to help them answer the question – or crack the case. From this point, students move on to the “ Investigating the Evidence ” section. Students are provided links to appropriate digital primary sources to help them crack the case. These documents might include text files, images, audio, or video clips. In the “ Searching for Clues ” stage, students are provided with a set of questions for their Detective’s Log, guiding their analysis of the evidence. This can be very structured, or more open-ended, depending on the instructional goals. Often, these questions will be provided in the form of a printable handout from which students work. Finally, in the “ Cracking the Case ” section, students present their answer, along with a rationale rooted in the evidence, to the initial question. Additionally, students are encouraged to enter new questions that have arisen during the process for future investigation. For every case, there is a section for the teacher. This section will list particular objectives for the activity and will also provide additional contextual information and resources as well as instructional strategies that the teacher might find useful. The model is intentionally standardized so that teachers can easily browse the activities without getting bogged down in unusual terminology. Ultimately, the hope is that teachers do what they do best-that is, download an activity and either use it “as is” or cut, rearrange or extend an activity for use within their particular classroom. (Description of HSI Model taken with permission from: http://web.wm.edu/hsi/model.html )

Guiding Question:

How does Article II of the United States Constitution promote a republic and balance the need for energy in the Executive with the need for liberty?

Learning Objective:

After completing this lesson, students should be able to: Analyze Federalist and Antifederalist papers and explain the arguments and compromises that were made to balance the need for energy and the need for liberty with the establishment of the Executive branch as described in Article II of the U.S. Constitution.

Background Information for the Teacher:

The years were 1787 and 1788. Along with the debate over the Constitution that was taking place in the state legislatures, an “out-of-doors” debate raged in newspapers and pamphlets throughout America’s thirteen states following the Constitutional Convention over the Constitution that had been proposed. Origin of The Federalist The eighty-five essays appeared in one or more of the following four New York newspapers: 1) The New York Journal , edited by Thomas Greenleaf, 2) Independent Journal , edited by John McLean, 3) New York Advertiser , edited by Samuel and John Loudon, and 4) Daily Advertiser , edited by Francis Childs. Initially, they were intended to be a twenty essay response to the Antifederalist attacks on the Constitution that were flooding the New York newspapers right after the Constitution had been signed in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. The Cato letters started to appear on September 27, George Mason’s objections were in circulation and the Brutus essays were launched on October 18. The number of essays in The Federalist was extended in response to the relentless, and effective, Antifederalist criticism of the proposed Constitution. McLean bundled the first 36 essays togetherthey appeared in the newspapers between October 27, 1787 and January 8, 1788and published them as Volume 1 on March 22, 1788. Essays 37 through 77 of The Federalist appeared between January 11, and April 2, 1788. On May 28, McLean took Federalist 37-77 as well as the yet to be published Federalist 78-85 and issued them all as Volume 2 of The Federalist . Between June 14 and August 16, these eight remaining essaysFederalist 78-85appeared in the Independent Journal and New York Packet . The Status of The Federalist One of the persistent questions concerning the status of The Federalist is this: is it a propaganda tract written to secure ratification of the Constitution and thus of no enduring relevance or is it the authoritative expositor of the meaning of the Constitution having a privileged position in constitutional interpretation? It is tempting to adopt the former position because 1) the essays originated in the rough and tumble of the ratification struggle. It is also tempting to 2) see The Federalist as incoherent; didn’t Hamilton and Madison disagree with each other within five years of co-authoring the essays? Surely the seeds of their disagreement are sown in the very essays! 3) The essays sometimes appeared at a rate of about three per week and, according to Madison, there were occasions when the last part of an essay was being written as the first part was being typed. 1) One should not confuse self-serving propaganda with advocating a political position in a persuasive manner. After all, rhetorical skills are a vital part of the democratic electoral process and something a free people have to handle. These are op-ed pieces of the highest quality addressing the most pressing issues of the day. 2) Moreover, because Hamilton and Madison parted ways doesn’t mean that they weren’t in fundamental agreement in 1787-1788 about the need for a more energetic form of government. And just because they were written with certain haste doesn’t mean that they were unreflective and not well written. Federalist 10, the most famous of all the essays, is actually the final draft of an essay that originated in Madison’s Vices in 1787, matured at the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, and was refined in a letter to Jefferson in October 1787. All of Jay’s essays focus on foreign policy, the heart of the Madisonian essays are Federalist 37-51 on the great difficulty of founding, and Hamilton tends to focus on the institutional features of federalism and the separation of powers. I suggest, furthermore, that the moment these essays were available in book form, they acquired a status that went beyond the more narrowly conceived objective of trying to influence the ratification of the Constitution. The Federalist now acquired a “timeless” and higher purpose, a sort of icon status equal to the very Constitution that it was defending and interpreting. And we can see this switch in tone in Federalist 37 when Madison invites his readers to contemplate the great difficulty of founding. Federalist 38 , echoing Federalist 1 , points to the uniqueness of the America Founding: never before had a nation been founded by the reflection and choice of multiple founders who sat down and deliberated over creating the best form of government consistent with the genius of the American people. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Constitution as the work of “demigods,” and The Federalist “the best commentary on the principles of government, which ever was written.” There is a coherent teaching on the constitutional aspects of a new republicanism and a new federalism in The Federalist that makes the essays attractive to readers of every generation. Authorship of The Federalist A second question about The Federalist is how many essays did each person write? James Madisonat the time a resident of New York since he was a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress that met in New YorkJohn Jay, and Alexander Hamiltonboth of New Yorkwrote these essays under the pseudonym, “Publius.” So one answer to the question is that how many essays each person wrote doesn’t matter since everyone signed off under the same pseudonym, “Publius.” But given the iconic status of The Federalist , there has been an enduring curiosity about the authorship of the essays. Although it is virtually agreed that Jay wrote only five essays, there have been several disputes over the decades concerning the distribution of the essays between Hamilton and Madison. Suffice it to note, that Madison’s last contribution was Federalist 63 , leaving Hamilton as the exclusive author of the nineteen Executive and Judiciary essays. Madison left New York in order to comply with the residence law in Virginia concerning eligibility for the Virginia ratifying convention . There is also widespread agreement that Madison wrote the first thirteen essays on the great difficulty of founding. There is still dispute over the authorship of Federalist 50-58, but these have persuasively been resolved in favor of Madison. Outline of The Federalist A third question concerns how to “outline” the essays into its component parts. We get some natural help from the authors themselves. Federalist 1 outlines the six topics to be discussed in the essays without providing an exact table of contents. The authors didn’t know in October 1787 how many essays would be devoted to each topic. Nevertheless, if one sticks with the “formal division of the subject” outlined in the first essay, it is possible to work out the actual division of essays into the six topic areas or “points” after the fact so to speak. Martin Diamond was one of the earliest scholars to break The Federalist into its component parts. He identified Union as the subject matter of the first thirty-six Federalist essays and Republicanism as the subject matter of last forty-nine essays. There is certain neatness to this breakdown, and accuracy to the Union essays. The first three topics outlined in Federalist 1 are 1) the utility of the union, 2) the insufficiency of the present confederation under the Articles of Confederation , and 3) the need for a government at least as energetic as the one proposed. The opening paragraph of Federalist 15 summarizes the previous fourteen essays and says: “in pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the pursuance of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the ‘insufficiency of the present confederation.'” So we can say with confidence that Federalist 1-14 is devoted to the utility of the union. Similarly, Federalist 23 opens with the following observation: “the necessity of a Constitution, at least equally energetic as the one proposed is the point at the examination of which we are now arrived.” Thus Federalist 15-22 covered the second point dealing with union or federalism. Finally, Federalist 37 makes it clear that coverage of the third point has come to an end and new beginning has arrived. And since McLean bundled the first thirty-six essays into Volume 1, we have confidence in declaring a conclusion to the coverage of the first three points all having to do with union and federalism. The difficulty with the Diamond project is that it becomes messy with respect to topics 4, 5, and 6 listed in Federalist 1 : 4) the Constitution conforms to the true principles of republicanism , 5) the analogy of the Constitution to state governments, and 6) the added benefits from adopting the Constitution. Let’s work our way backward. In Federalist 85 , we learn that “according to the formal division of the subject of these papers announced in my first number, there would appear still to remain for discussion two points,” namely, the fifth and sixth points. That leaves, “republicanism,” the fourth point, as the topic for Federalist 37-84, or virtually the entire Part II of The Federalist . I propose that we substitute the word Constitutionalism for Republicanism as the subject matter for essays 37-51, reserving the appellation Republicanism for essays 52-84. This substitution is similar to the “Merits of the Constitution” designation offered by Charles Kesler in his new introduction to the Rossiter edition; the advantage of this Constitutional approach is that it helps explain why issues other than Republicanism strictly speaking are covered in Federalist 37-46. Kesler carries the Constitutional designation through to the end; I suggest we return to Republicanism with Federalist 52 . Taken from Introduction to The Federalist . The Four Options of Antifederalism It is helpful to consider four options when reflecting on the importance of the Antifederalists . They are 1) incoherent and irrelevant, 2) coherent and irrelevant, 3) incoherent and relevant, and 4) coherent and relevant. And which option we choose is in large part linked to a) how we define the Antifederalist project, b) how we interpret The Federalist and c) whether or not we are willing to retrieve the Antifederalists on their own terms or whether we see them as valuable in a quarrel over the American regime. One way to define the Antifederalists is that they are those who opposed ratification of the unamended Constitution in 1787-1788. This definition might well make them lower case antifederalists or anti-federalists. The point is that they are both incoherent and irrelevant. A broader definition, one that reaches back to Montesquieu or to Aristotle introduces the possibility that they may be either coherent but irrelevant (Cecelia Kenyon) or incoherent but relevant (Herbert Storing). The upper case and hyphenated Anti-Federalist nomenclature is the preferred appellation for this approach. There is one last choice the Antifederalists are coherent and relevant and this suggests that we call them Antifederalists, upper case and non-hyphenated. This fourth approach argues that their coherence and relevance is located in their basically American and new world character. They are neither Kenyon’s “men of little faith” nor Storing’s “incomplete reasoners,” and thus “junior founders.” Their thought is grounded in the American struggle for independence, draws strength from the colonial tradition, the natural rights tradition, and new state constitutions that emerged between 1776 and 1780. Their thought is moreover informed by the Articles of Confederation of the 1780s, matured by the debates over the creation and adoption of the Constitution , culminates with the adoption of the Bill of Rights and then bids farewell to its creative phase with the introduction of the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions . I encourage the reader to consider this broader, and basically American and new world, definition of the Antifederalist project. The Antifederalist Reputation This reputation of the Antifederalists as irrelevant, even proto-Calhoun, disunionists was shaped, in part, by Alexander Hamilton’s observation in Federalist 1 : “we already hear it whispered in the private circles of those who oppose the new Constitution, that the thirteen States are of too great an extent for any general system, and that we must of necessity resort to separate confederacies of distinct portions of the whole.” The response by the Antifederalist, “Centinel,” to Hamilton has been largely ignored: this claim of disunion, he said, is “from the deranged brain of Publius, a New York writer, who has devoted much time, and wasted more paper in combating chimeras of his own creation.” James Madison’s commentary in Federalist 38 was no doubt also influential in portraying the Antifederalists as incoherent. Madison asks: “Are they agreed, are any two of them agreed, in their objections to the remedy proposed, or in the proper one to be substituted? Let them speak for themselves.” But Madison does not “let them speak for themselves.” When the Antifederalists are permitted to speak for themselves, as Antifederalist Melancton Smith demonstrates, a remarkably coherent alternative emerges. “An Old Whig” makes the same point: “about the same time, in very different parts of the continent, the very same objections have been made, and the very same alterations proposed by different writers, who I verily believe, know nothing at all of each other.” This appeared six weeks prior to Federalist 38 . When the Antifederalists are permitted to speak for themselves, a coherent and relevant account emerges. The Federalist argues for checks and balances, especially against the legislature; the Antifederalists support term limits and rotation in office for all elected and appointed officials. But this is why Kenyon calls them irrelevant; they held to a scheme of representation that was outmoded even for 1787. By contrast, The Federalist argues that the representative needs a longer duration in office than provided by traditional republicanism in order to exercise the responsibilities of the office and resist the narrow and misguided demands of an overbearing and unjust majority. Because the Antifederalists were dubious that one could be both democratic and national, they urged less independence for the elected representatives. They claimed that practical experience demonstrated that short terms in office, reinforced by term limits, would be an indispensable additional security to the objective of the election system to secure that the representatives were responsible to the people. For the Antifederalists, a responsible representative the essential characteristic of republicanism was constitutionally obliged to be responsive to the sovereign people. Ultimately, the “accountability” of the representative was secured by “rotation in office,” the vital principle of representative democracy. This is the concept of the citizen-politician who serves the public briefly and then returns to the private sphere. In Federalist 23 , Hamilton describes the Antifederalist position as “absurd” because they admit the legitimacy of the ends and then are squeamish, even, cowardly, about the means: “For the absurdity must continually stare us in the face of confiding to a government the direction of the most essential national interests, without daring to trust it to the authorities which are indispensable to their proper and efficient management. Let us not attempt to reconcile contradictions, but firmly embrace a rational alternative.” The Antifederalists, according to Hamilton, are mushy thinkers; they fuss over means rather than focusing on ends. Storing totally agrees: they should have focused on the ends of union and the (limited) role of the states in the accomplishment of those ends. The Antifederalists, according to Hamilton and Storing, wanted union but argued against giving the union the means to secure the ends. They were absurd and thus they were incoherent. But there is more. According to Storing, the Antifederalists also avoided the hard and “ugly truth” of Federalist 51 : the people can’t govern themselves voluntarily. This truth, says Storing, is something that the Federalists faced squarely. Coherent and Relevant Perhaps that the Antifederalists have a coherent understanding of federalism and republicanism grounded in “democratic federalism” and “constitutional republicanism” and that this coherent understanding is worth keeping alive in the twenty-first century because it addresses what ails the contemporary American federal republic. Antifederalist thought is the built-in American antidote for the ills of the American federal republic. In particular, the three other alternative explanations either read history backwards or import European or ancient categories to explain an American experience. The Antifederalists are not primarily interested in the “good government” project of The Federalist or the “best regime” project of the ancients, or the “exit rights” project of the secessionists or many of the other projects invented by the various historical schools; instead, I suggest they are interested in the creation and preservation of free government. They remind us that free government means limited government, and thus the political project should be focused on limiting rather than empowering politicians. Antifederalist statesmanship involves an attachment to means, rather than an administration of ends. There is nothing absurd or incoherent about being fussy over the use and misuse of means because means are actually powers and the abuse of powers sets us down the slippery slope to old world tyranny. The Antifederalists speak to those who have become increasingly disillusioned by the collapse of decentralized state and local government, the greater intervention by the federal government in economic matters, the blurring of the separation of powers, and the replacement of voluntary associations by government programs. The Antifederalists warn: beware the dangers of “democratic nationalism,” and “delegated constitutionalism.” These are warnings from within the very American System itself. They warn us that there is something morally corrosive about the exercise of political power and thus they remind us about the need for the rule of law. And they warn about the dangers of the Federalist temptation with empire abroad. The Antifederalists are not isolationists, men of little faith, or junior partners; they are “Antitemptationalists” with a message of liberty and responsibility that resonates across the centuries. “On the most important points,” then, the Antifederalists were not only in agreement but their position was coherent and is currently relevant. They believed that republican liberty was best preserved in small units where the people had an active and continuous part to play in government. Although they thought that the Articles best secured this concept of republicanism, they were willing to bestow more authority on the federal government as long as this didn’t undermine the principles of federalism and republicanism. They argued that the Constitution placed republicanism in danger because it undermined the pillars of small territorial size, frequent elections, short terms in office, and accountability to the people, and, at the same time, encouraged the representatives to become independent from the people and the state governments. They warned that unless restrictions were placed on the powers of Congress, the Executive, and the Judiciary, the potentiality for the abuse of power would become a reality. These warnings culminated in their insistence on a Bill of Rights which, in conjunction with small territory, representative dependency, and strict construction, they conceived as the ultimate “auxiliary precaution.” The expression of discontent over the last fifty years about American politics has an ominous ring, revealing the widespread Antifederal mood in the electorate. Among the dramatic changes in recent American politics are the alarming alienation of the citizenry from the electoral system, the increased presence of the centralized Administrative State, and the dangerous consequences of an activist judiciary that openly thwarts the deliberate sense of the majority. These are all Antifederalist concerns about the tyranny of politicians. The term limits movement of the late twentieth century demonstrates that the Antifederalist message keep your representatives on a short leash, otherwise you will lose your freedom still resonates with the American people, because Antifederalism is very much part of the American political experience. When we hear the claim that our representatives operate independently of the people, and that the Congress fails to represent the broad cross-section of interests in America, we are hearing an echo of the Antifederalist critique of representation. When we hear that the federal government has spawned a vast and irresponsive administrative bureaucracy that interferes too much with the life of American citizens, we are reminded of the warnings of the Antifederalists concerning consolidated government. They warn that, in effect, executive orders, executive privileges, and executive agreements will create the “Imperial Presidency.” And they warn that an activist judiciary will undermine the deliberate sense of the majority. The criticism that Americans have abandoned a concern for their religious heritage and neglected the importance of local customs, habits, and morals, recalls the Antifederalist dependence upon self-restraint and self-reliance. When we hear a concern for the passing of decentralization old time federalism we are hearing the Antifederalist lament. The Antifederalist project calls for a rejuvenation of interest in Antifederalist “democratic federalism” and “constitutional republicanism.” Since American politics is often a debate over the possibilities and limitations of the separation of powers, an independent judiciary, federalism, and representative government, it is vital that the potency of Antifederalist political analysis be restored. If the electorate has “lost faith” in the responsibility of the representatives in every branch of government, then the very concept of representation undergirding the country is in crisis. What is the solution? If no one cares either about the question, or the solution, then America is perhaps doomed to go the way of previous great regimes, and the experiment in “republican government” is exactly what opponents through the centuries have predicted it would be: a complete failure thus proving that the human race is incapable of being governed other than by force and fraud. Antifederalist political science advocated concentration of the power of the people and eliminating temptations for the concentration of power in officeholders. The heart of their method was to propose a scheme of representation that safeguarded interests and avoid the clashes of factions. This called for certain homogeneity of interests, as opposed to the Madisonian encouragement of diverse interests. The latter approach they rejected as unnecessary and dangerous. They placed their faith instead in the virtue of “middling” Americans a virtue that was not informed by ancient Sparta or even ancient Rome but by the modern doctrine of personal self-reliance coupled with holding their representatives “in the greatest responsibility to their constituents.” The Antifederalists viewed the Constitution as creating mutually independent sovereign agents. They argued that such independent rulers would “erect an interest separate from the ruled,” which will tempt them to lose both their federal and their republican mores. The Antifederalists concluded that unless executive power was yet more limited, representation more broadened, presidents and senators made more responsible to the people and the state governments protected unless the arrangement was significantly modified the proposed regime would necessarily destroy political liberty by destroying the sovereignty of the people, the litmus test of republicanism. As an expression of this “constitutional republicanism,” they insisted on a Bill of Rights as a declaration of popular sovereignty. In conclusion, the Antifederalists warned about the tendency of the American system toward the consolidation of political power in a) the nation to the detriment of the various states, and b) one branch of the federal government at the expense of the separation of powers. They warned about c) the corrupting influence that political power has on even decent people, whom decent people elected into office, and d) that the rule of law has a privileged position in republican government. They also anticipated the idea that e) all politics is or should be local and thus particular attachments rather than abstract ideas matter in the preservation of a liberal political order. Taken from Introduction to the Antifederalists .

Preparing to Teach this Lesson:

Prior to teaching this lesson the teacher should cover content related to the Articles of Confederation and its weaknesses. The teacher should familiarize her/himself with Madison’s Notes on the Constitutional Convention of 1787 on the following days outlined below. Gordon Lloyd has presented the content of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 as a Four Act Drama . Students and teacher should also be familiar with the Federalist and Antifederalist Debates . Three activities are outlined below and should be implemented in order. Activity 1: Becoming a Detective Students are introduced to the historical scene under investigation. Here background information and context are provided for the students on Establishing the Electoral College and the Presidency . Students are then presented with an engaging question to guide their inquiry. The engaging question for the lesson is, “How does Article II of the United States Constitution promote a republic and balance the need for energy in the Executive with the need for liberty? Finally, students are presented with a task to help them answer the question or crack the case.

Activity 2: Investigating the Evidence

Students are provided links to appropriate digital primary sources using the American Founding website to help them crack the case.

Activity 3: Searching for Clues

Students are provided with a set of questions for their Detective’s Log, guiding their analysis of the evidence. Students are provided a printable handout, Detective Log, to work from.

Analyzing Primary Sources:

If your students lack experience in dealing with primary sources, you might use one or more preliminary exercises to help them develop these skills. The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress includes a set of such activities. Another useful resource is the Digital Classroom of the National Archives, which features a set of Document Analysis Worksheets . Finally, History Matters offers pages on “ Making Sense of Maps ” and “ Making Sense of Oral History ” which give helpful advice to teachers in getting their students to use such sources effectively.

Suggested Activities:

Introduction to Case:

In this case, students explore a series of artifacts using the American Founding website . The artifacts serve as evidence taken from Major Themes at the Constitutional Convention , Federalist and Antifederalist Debates , and Document Library . As students explore the artifacts/evidence, they will work through a “detective’s log” to help them analyze and chart findings from the sources. In the end, students are asked to write an essay answering the following question: How does Article II of the United States Constitution promote a republic and balance the need for energy in the Executive with the need for liberty? Additionally, students will be asked to indicate whether they were satisfied with the evidence and to list any additional questions that have been left unanswered through the investigation.

Activity 1: Becoming a Detective

Students are introduced to the historical scene under investigation. Here background information and context are provided for the students on the Establishing the Electoral College and the Presidency . As students read background information, they will complete the concept ladder resource , developing a question for each rung of the concept ladder based on their prior knowledge of American history and reading of the Establishing the Electoral College and the Presidency introduction. Students’ questions should represent what they expect to be answered in their investigation of the Executive. Students are then presented with an engaging question to guide their inquiry. The engaging question for the lesson is, “How does Article II of the United States Constitution promote a republic and balance the need for energy in the Executive with the need for liberty?” Finally, students are presented with the task to help them answer the question or crack the case. Teachers should share the Detective Log handout at this time.