French Revolution

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) was a period of major societal and political upheaval in France. It witnessed the collapse of the monarchy, the establishment of the First French Republic, and culminated in the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte and the start of the Napoleonic era. The French Revolution is considered one of the defining events of Western history.

The Revolution of 1789, as it is sometimes called to distinguish it from later French revolutions, originated from deep-rooted problems that the government of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) proved incapable of fixing; such problems were primarily related to France's financial troubles as well as the systemic social inequality embedded within the Ancien Régime . The Estates-General of 1789 , summoned to address these issues, resulted in the formation of a National Constituent Assembly, a body of elected representatives from the three societal orders who swore never to disband until they had written a new constitution. Over the next decade, the revolutionaries attempted to dismantle the oppressive old society and build a new one based on the principles of the Age of Enlightenment exemplified in the motto: " Liberté, égalité, fraternité ."

Although initially successful in establishing a French Republic, the revolutionaries soon became embroiled in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) in which France fought against a coalition of major European powers. The Revolution quickly devolved into violent paranoia, and 20-40,000 people were killed in the Reign of Terror (1793-94), including many of the Revolution's former leaders. After the Terror, the Revolution stagnated until 1799, when Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) took control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire , ultimately transitioning the Republic into the First French Empire (1804-1814, 1815). Although the Revolution failed to prevent France from falling back into autocracy, it managed to succeed in other ways. It inspired numerous revolutions throughout the world and helped shape the modern concepts of nation-states, Western democracies, and human rights.

Most of the causes of the French Revolution can be traced to economic and social inequalities that were exacerbated by the brokenness of the Ancien Régime (“old regime”), the name retroactively given to the political and social system of the Kingdom of France in the last few centuries of its initial existence. The Ancien Régime was divided into three estates, or social orders: the clergy, nobility, and commoners. The first two estates enjoyed many social privileges, including tax exemptions, that were not granted to the commoners, a class that made up well over 90% of the population. The Third Estate was burdened with manual labor as well as paying most of the taxes.

Rapid population growth contributed to the general suffering; by 1789, France was the most populous European state with over 28 million people. Job growth had not kept up with the swelling population, leaving 8- 12 million impoverished. Backwards agricultural techniques and a steady string of terrible harvests led to starvation. Meanwhile, a rising class of wealthy commoners, the bourgeoisie, threatened the privileged position of the aristocracy, increasing tensions between social classes. Ideas of the Age of Enlightenment also contributed to national unrest; people began to view the Ancien Régime as corrupt, mismanaged, and tyrannical. Hatred was especially directed toward Queen Marie Antoinette , who was seen to personify everything wrong with the government.

A final significant cause was France's monumental state debt, accumulated by its attempts to maintain its status as a global power. Expensive wars and other projects had put the French treasury billions of livres into debt, as it had been forced to take out loans at enormously high interest rates. The country's irregular systems of taxation were ineffective, and as creditors began to call for repayment in the 1780s, the government finally realized something had to be done.

The Gathering Storm: 1774-1788

On 10 May 1774, King Louis XV of France died after a reign of nearly 60 years, leaving his grandson to inherit a troubled and broken kingdom. Only 19 years old, Louis XVI was an impressionable ruler who adhered to the advice of his ministers and involved France in the American War of Independence. Although French involvement in the American Revolution succeeded in weakening Great Britain , it also added substantially to France's debt while the success of the Americans encouraged anti-despotic sentiments at home.

In 1786, Louis XVI was convinced by his finance minister, Charles-Alexandre Calonne, that the issue of state debt could no longer be ignored. Calonne presented a list of financial reforms and convened the Assembly of Notables of 1787 to rubberstamp them. The Notables, a mostly aristocratic assembly, refused and told Calonne that only an Estates-General could approve such radical reforms. This referred to an assembly of the three estates of pre-revolutionary France , a body that had not been summoned in 175 years. Louis XVI refused, realizing that an Estates-General could undermine his authority. Instead, he fired Calonne and took the reforms to the parlements .

The parlements were the 13 judicial courts that were responsible for registering royal decrees before they went into effect. Consisting of aristocrats, the parlements had long struggled against royal authority, still bitter that their class had been subjugated by the "sun king" Louis XIV of France a century before. Spotting a chance to recover some power, they refused to register the royal reforms and joined the Notables in advocating for an Estates-General. When the crown responded by exiling the courts, riots erupted across the country; the parlements had presented themselves as champions of the people, thereby winning the commoners' support. One of these riots erupted in Grenoble on 7 June 1788 and led the three estates of Dauphiné to gather without the king's consent. Known as the Day of Tiles, this is credited by some historians as the start of the Revolution. Realizing he had been bested, Louis XVI appointed the popular Jacques Necker as his new finance minister and scheduled an Estates-General to convene in May 1789.

Rise of the Third Estate: February-September 1789

Across France, 6 million people participated in the electoral process for the Estates-General, and a total 25,000 cahiers de doléances , or lists of grievances, were drawn up for discussion. When the Estates-General of 1789 finally convened on 5 May in Versailles, there were 578 deputies representing the Third Estate, 282 for the nobility, and 303 for the clergy. Yet the double representation of the Third Estate was meaningless, as votes would still be counted by estate rather than by head. As the upper classes were sure to vote together, the Third Estate was at a disadvantage.

Subsequently, the Third Estate refused to verify its own elections, a process needed to begin proceedings. It demanded votes to be counted by head, a condition the nobility staunchly refused. Meanwhile, Louis XVI's attention was drawn away by the death of his son, paralyzing royal authority. On 13 June, having reached an impasse, the Third Estate commenced roll call, breaking protocol by beginning proceedings without the consent of the king or the other orders. On 17 June, following a motion proposed by Abbé Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès , the Third Estate officially proclaimed itself a National Constituent Assembly. Two days later, the clergy formally voted to join it, and the nobility begrudgingly followed suit. On 20 June, after finding themselves locked out of the assembly hall, the deputies of the National Assembly met in the royal tennis court. There, they swore the Tennis Court Oath, promising never to disband until they had given France a new constitution. The French Revolution had begun.

Louis XVI realized he needed to regain control. In early July, he called over 30,000 soldiers into the Paris Basin, and on 11 July, he dismissed Necker and other ministers considered too friendly to the insolent revolutionaries. Fearing the king meant to crush the Revolution, the people of Paris rioted on 12 July. Their uprising climaxed on 14 July with the Storming of the Bastille , when hundreds of citizens successfully attacked the Bastille fortress to loot it for ammunition. The king backed down, sending away his soldiers and reinstating Necker. Unnerved by these events, the king's youngest brother, Comte d'Artois, fled France with an entourage of royalists on the night of 16 July; they were the first of thousands of émigrés to flee.

In the coming weeks, the French countryside broke out into scattered riots, as rumors spread of aristocratic plots to deprive citizens of their liberties. These riots resulted in mini-Bastilles as peasants raided the feudal estates of local seigneurs, forcing nobles to renounce their feudal rights. Later known as the Great Fear , this wave of panic forced the National Assembly to confront the issue of feudalism . On the night of 4 August, in a wave of patriotic fervor, the Assembly announced that the feudal regime was "entirely destroyed" and ended the privileges of the upper classes. Later that month, it accepted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , a landmark human rights document that championed the general will of the people, separation of powers, and the idea that human rights were universal. These two achievements are considered the most important and longest-lasting accomplishments of the Revolution.

A People's Monarchy: 1789-1791

As the National Assembly slowly drafted its constitution, Louis XVI was sulking in Versailles. He refused to consent to the August Decrees and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, demanding instead that the deputies include his right to an absolute veto in the new constitution. This enraged the people of Paris, and on 5 October 1789, a crowd of 7,000 people, mostly market women , marched from Paris to Versailles in the pouring rain, demanding bread and that the king accept the Assembly's reforms. Louis XVI had no choice but to accept and was forced to leave his isolation at Versailles and accompany the women back to Paris, where he was installed in the Tuileries Palace . Known as the Women's March on Versailles , or the October Days, this insurrection led to the end of the Ancien Régime and the beginning of France's short-lived constitutional monarchy.

The next year and a half marked a relatively calm phase of the Revolution; indeed, many people believed the Revolution was over. Louis XVI agreed to adopt the Assembly's reforms and even appeared reconciled to the Revolution by accepting a tricolor cockade. The Assembly, meanwhile, began to rule France, adopting its own ill-fated currency, the assignat , to help tackle the outstanding debt. Having declawed the nobility, it now turned its attentions toward the Catholic Church. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy , issued on 12 July 1790, forced all clerics to swear oaths to the new constitution and put their loyalty to the state before their loyalty to the Pope in Rome . At the same time, church lands were confiscated by the Assembly, and the papal city of Avignon was reintegrated into France. These attacks on the church alienated many from the Revolution, including the pious Louis XVI himself.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the Bastille, saw a massive celebration on the Champ de Mars . Led by the Marquis de Lafayette , the Festival of the Federation was meant to mark the unity of the newly liberated French people under the magnanimous rule of their citizen-king. But the king had other plans. A year later, on the night of 20-21 June 1791, he and his family left the Tuileries in disguise and attempted to escape France in what has become known as the Flight to Varennes . They were quickly caught and returned to Paris, but their attempt had irrevocably destroyed any trust the people had in the monarchy. Calls began to mount for Louis XVI to be deposed, while some even began to seriously demand a French Republic. The issue divided the Jacobin Club, a political society where revolutionaries gathered to discuss their goals and agendas. Moderate members loyal to the idea of constitutional monarchy split to form the new Feuillant Club, while the remaining Jacobins were further radicalized.

On 17 July 1791, a crowd of demonstrators gathered on the Champ de Mars to demand the king's deposition. They were fired on by the Paris National Guard, commanded by Lafayette , resulting in 50 deaths. The Champ de Mars Massacre sent republicans on the run, giving the Feuillants enough time to push through their constitution, which centered around a weakened, liberal monarchy. On 30 September 1791, the new Legislative Assembly met, but despite the long-awaited constitution, the Revolution was more divided than ever.

Birth of a Republic: 1792-1793

Many deputies of the Legislative Assembly formed themselves into two factions: the more conservative Feuillants sat on the right of the Assembly president, while the radical Jacobins sat to his left, giving rise to the left/right political spectrum still used today. After the monarchs of Austria and Prussia threatened to destroy the Revolution in the Declaration of Pillnitz , a third faction split off from the Jacobins, demanding war as the only way to preserve the Revolution. This war party, later known as the Girondins, quickly dominated the Legislative Assembly, which voted to declare war on Austria on 20 April 1792. This began the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), as the old regimes of Europe , feeling threatened by the radical revolutionaries, joined together in a coalition against France.

Initially, the war went disastrously for the French. The summer of 1792 saw a Prussian army accompanied by French royalist émigrés slowly march toward Paris. In August, the invaders issued the Brunswick Manifesto, threatening to destroy Paris should any harm come to the French royal family. This threat sent the people of Paris into a hysterical panic that led to the Storming of the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792, the insurrection that finally toppled the monarchy. Still fearful of counter-revolutionary enemies who might aid the Prussians, Paris mobs then invaded the city's prisons and murdered over 1,100 people in the September Massacres .

On 20 September 1792, a French army finally halted the Prussian invasion at the miraculous Battle of Valmy . The next day, the jubilated Legislative Assembly officially proclaimed the French Republic. The later French Republican calendar dated itself from this moment, which was seen as the ultimate accomplishment of humankind. The Assembly was disbanded, and a National Convention was convened to draft a new constitution. One of the Convention's first tasks was to decide the fate of the deposed Louis XVI; ultimately, he was tried and guillotined on 21 January 1793, his family kept imprisoned in the Tower of the Temple until the trial and execution of Marie Antoinette that October. The trial and execution of Louis XVI shocked Europe, causing Great Britain, Spain, and the Dutch Republic to enter the coalition against France.

Reign of Terror: 1793-1794

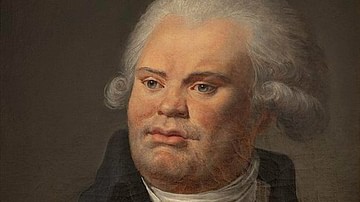

After the decline of the Feuillants, the Girondins became the Revolution's moderate faction. In early 1793, they were opposed by a group of radical Jacobins called the Mountain, primarily led by Maximilien Robespierre , Georges Danton , and Jean- Paul Marat. The Girondins and the Mountain maintained a bitter rivalry until the fall of the Girondins on 2 June 1793, when roughly 80,000 sans-culottes , or lower-class revolutionaries, and National Guards surrounded the Tuileries Palace, demanding the arrests of leading Girondins. This was accomplished, and the Girondin leaders were later executed.

The Mountain's victory deeply divided the nation. The assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday occurred amidst pockets of civil war that threatened to unravel the infant republic, such as the War in the Vendée and the federalist revolts . To quell this dissent and halt the advance of coalition armies, the Convention approved the creation of the Committee of Public Safety , which quickly assumed near total executive power. Through measures such as mass conscription, the Committee brutally crushed the civil wars and checked the foreign armies before turning its attention to unmasking domestic traitors and counter-revolutionary agents. The ensuing Reign of Terror, lasting from September 1793-July 1794 resulted in hundreds of thousands of arrests, 16,594 executions by guillotine, and tens of thousands of additional deaths. Aristocrats and clergymen were executed alongside former revolutionary leaders and thousands of ordinary people.

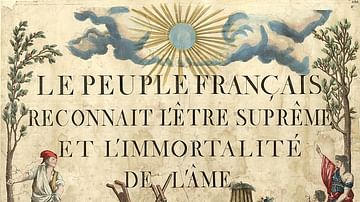

Robespierre accumulated almost dictatorial powers during this period. Attempting to curtail the Revolution's rampant dechristianization, he implemented the deistic Cult of the Supreme Being to ease France into his vision of a morally pure society. His enemies saw this as an attempt to claim total power and, fearing for their lives, decided to overthrow him; the fall of Maximilien Robespierre and his allies on 28 July 1794 brought the Terror to an end, and is considered by some historians to mark the decline of the Revolution itself.

Thermidorians & the Directory: 1794-1799

Robespierre's execution was followed by the Thermidorian Reaction , a period of conservative counter-revolution in which the vestiges of Jacobin rule were erased. The Jacobin Club itself was permanently closed in November 1794, and a Jacobin attempt to retake power in the Prairial Uprising of 1795 was crushed. The Thermidorians defeated a royalist uprising on 13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795) before adopting the Constitution of Year III (1795) and transitioning into the French Directory , the government that led the Republic in the final years of the Revolution.

Meanwhile, French armies had succeeded in pushing back the coalition's forces, defeating most coalition nations by 1797. The star of the war was undoubtedly General Napoleon Bonaparte, whose brilliant Italian campaign of 1796-97 catapulted him to fame. On 9 November 1799, Bonaparte took control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, bringing an end to the unpopular Directory. His ascendency marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Andress, David. The Terror . Time Warner Books Uk, 2005.

- Blanning, T. C. W. The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787-1802 . Hodder Education Publishers, 1996.

- Carlyle, Thomas & Sorensen, David R. & Kinser, Brent E. & Engel, Mark. The French Revolution . Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Davidson, Ian. The French Revolution. Pegasus Books, 2018.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Francois Furet & Mona Ozouf & Arthur Goldhammer. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Fraser, Antonia. Marie Antoinette. Anchor, 2002.

- Lefebvre, Georges & Palmer, R. R. & Palmer, R. R. & Tackett, Timothy. The Coming of the French Revolution . Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Lefebvre, Georges & White, John Albert. The Great Fear of 1789. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander. The Napoleonic Wars. Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Palmer, R. R. & Woloch, Isser. Twelve Who Ruled. Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Roberts, Andrew. Napoleon. Penguin Books, 2015.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens. Vintage, 1990.

- Scurr, Ruth. Fatal Purity. Holt Paperbacks, 2007.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de & Bevan, Gerald & Bevan, Gerald. The Ancien Régime and the Revolution . Penguin Classics, 2008.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What was the french revolution, what were 3 main causes of the french revolution, what began the french revolution, what ended the french revolution, what are some important events of the french revolution, related content.

Thermidorian Reaction

Georges Danton

Maximilien Robespierre

Fall of Maximilien Robespierre

Power Struggles in the Reign of Terror

Cult of the Supreme Being

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2023, January 12). French Revolution . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/French_Revolution/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " French Revolution ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified January 12, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/French_Revolution/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " French Revolution ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 12 Jan 2023. Web. 14 Jul 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 12 January 2023. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

History Cooperative

French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes

The French Revolution, a seismic event that reshaped the contours of political power and societal norms, began in 1789, not merely as a chapter in history but as a dramatic upheaval that would influence the course of human events far beyond its own time and borders.

It was more than a clash of ideologies; it was a profound transformation that questioned the very foundations of monarchical rule and aristocratic privilege, leading to the rise of republicanism and the concept of citizenship.

The causes of this revolution were as complex as its outcomes were far-reaching, stemming from a confluence of economic strife, social inequalities, and a hunger for political reform.

The outcomes of the French Revolution, embedded in the realms of political thought, civil rights, and societal structures, continue to resonate, offering invaluable insights into the power and potential of collective action for change.

Table of Contents

Time and Location

The French Revolution, a cornerstone event in the annals of history, ignited in 1789, a time when Europe was dominated by monarchical rule and the vestiges of feudalism. This epochal period, which spanned a decade until the late 1790s, witnessed profound social, political, and economic transformations that not only reshaped France but also sent shockwaves across the continent and beyond.

Paris, the heart of France, served as the epicenter of revolutionary activity , where iconic events such as the storming of the Bastille became symbols of the struggle for freedom. Yet, the revolution was not confined to the city’s limits; its influence permeated through every corner of France, from bustling urban centers to serene rural areas, each witnessing the unfolding drama of revolution in unique ways.

The revolution consisted of many complex factions, each representing a distinct set of interests and ideologies. Initially, the conflict arose between the Third Estate, which included a diverse group from peasants and urban laborers to the bourgeoisie, and the First and Second Estates, made up of the clergy and the nobility, respectively.

The Third Estate sought to dismantle the archaic social structure that relegated them to the burden of taxation while denying them political representation and rights. Their demands for reform and equality found resonance across a society strained by economic distress and the autocratic rule of the monarchy.

As the revolution evolved, so too did the nature of the conflict. The initial unity within the Third Estate fractured, giving rise to factions such as the Jacobins and Girondins, who, despite sharing a common revolutionary zeal, diverged sharply in their visions for France’s future.

The Jacobins , with figures like Maximilien Robespierre at the helm, advocated for radical measures, including the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic, while the Girondins favored a more moderate approach.

The sans-culottes , representing the militant working-class Parisians, further complicated the revolutionary landscape with their demands for immediate economic relief and political reforms.

The revolution’s adversaries were not limited to internal factions; monarchies throughout Europe viewed the republic with suspicion and hostility. Fearing the spread of revolutionary fervor within their own borders, European powers such as Austria, Prussia, and Britain engaged in military confrontations with France, aiming to restore the French monarchy and stem the tide of revolution.

These external threats intensified the internal strife, fueling the revolution’s radical phase and propelling it towards its eventual conclusion with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who capitalized on the chaos to establish his own rule.

READ MORE: How Did Napoleon Die: Stomach Cancer, Poison, or Something Else?

Causes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution’s roots are deeply embedded in a confluence of political, social, economic, and intellectual factors that, over time, eroded the foundations of the Ancien Régime and set the stage for revolutionary change.

At the heart of the revolution were grievances that transcended class boundaries, uniting much of the nation in a quest for profound transformation.

Economic Hardship and Social Inequality

A critical catalyst for the revolution was France’s dire economic condition. Fiscal mismanagement, costly involvement in foreign wars (notably the American Revolutionary War), and an antiquated tax system placed an unbearable strain on the populace, particularly the Third Estate, which bore the brunt of taxation while being denied equitable representation.

Simultaneously, extravagant spending by Louis XVI and his predecessors further drained the national treasury, exacerbating the financial crisis.

The social structure of France, rigidly divided into three estates, underscored profound inequalities. The First (clergy) and Second (nobility) Estates enjoyed significant privileges, including exemption from many taxes, which contrasted starkly with the hardships faced by the Third Estate, comprising peasants , urban workers, and a rising bourgeoisie.

This disparity fueled resentment and a growing demand for social and economic justice.

Enlightenment Ideals

The Enlightenment , a powerful intellectual movement sweeping through Europe, profoundly influenced the revolutionary spirit. Philosophers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu criticized traditional structures of power and authority, advocating for principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Their writings inspired a new way of thinking about governance, society, and the rights of individuals, sowing the seeds of revolution among a populace eager for change.

Political Crisis and the Estates-General

The immediate catalyst for the French Revolution was deeply rooted in a political crisis, underscored by the French monarchy’s chronic financial woes. King Louis XVI, facing dire fiscal insolvency, sought to break the deadlock through the convocation of the Estates-General in 1789, marking the first assembly of its kind since 1614.

This critical move, intended to garner support for financial reforms, unwittingly set the stage for widespread political upheaval. It provided the Third Estate, representing the common people of France, with an unprecedented opportunity to voice their longstanding grievances and demand a more significant share of political authority.

The Third Estate, comprising a vast majority of the population but long marginalized in the political framework of the Ancien Régime, seized this moment to assert its power. Their transformation into the National Assembly was a monumental shift, symbolizing a rejection of the existing social and political order.

The catalyst for this transformation was their exclusion from the Estates-General meeting, leading them to gather in a nearby tennis court. There, they took the historic Tennis Court Oath, vowing not to disperse until France had a new constitution.

This act of defiance was not just a political statement but a clear indication of the revolutionaries’ resolve to overhaul French society.

Amidst this burgeoning crisis, the personal life of Marie Antoinette , Louis XVI’s queen, became a focal point of public scrutiny and scandal.

Married to Louis at the tender age of fourteen, Marie Antoinette, the youngest daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, was known for her lavish lifestyle and the preferential treatment she accorded her friends and relatives.

READ MORE: Roman Emperors in Order: The Complete List from Caesar to the Fall of Rome

Her disregard for traditional court fashion and etiquette, along with her perceived extravagance, made her an easy target for public criticism and ridicule. Popular songs in Parisian cafés and a flourishing genre of pornographic literature vilified the queen, accusing her of infidelity, corruption, and disloyalty.

Such depictions, whether grounded in truth or fabricated, fueled the growing discontent among the populace, further complicating the already tense political atmosphere.

The intertwining of personal scandals with the broader political crisis highlighted the deep-seated issues within the French monarchy and aristocracy, contributing to the revolutionary fervor.

As the political crisis deepened, the actions of the Third Estate and the controversies surrounding Marie Antoinette exemplified the widespread desire for change and the rejection of the Ancient Régime’s corruption and excesses.

Key Concepts, Events, and People of the French Revolution

As the Estates General convened in 1789, little did the world know that this gathering would mark the beginning of a revolution that would forever alter the course of history.

Through the rise and fall of factions, the clash of ideologies, and the leadership of remarkable individuals, this era reshaped not only France but also set a precedent for future generations.

From the storming of the Bastille to the establishment of the Directory, each event and figure played a crucial role in crafting a new vision of governance and social equality.

Estates General

When the Estates General was summoned in May 1789, it marked the beginning of a series of events that would catalyze the French Revolution. Initially intended as a means for King Louis XVI to address the financial crisis by securing support for tax reforms, the assembly instead became a flashpoint for broader grievances.

Representing the three estates of French society—the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners—the Estates General highlighted the profound disparities and simmering tensions between these groups.

The Third Estate, comprising 98% of the population but traditionally having the least power, seized the moment to push for more significant reforms, challenging the very foundations of the Ancient Régime.

The deadlock over voting procedures—where the Third Estate demanded votes be counted by head rather than by estate—led to its members declaring themselves the National Assembly, an act of defiance that effectively inaugurated the revolution.

This bold step, coupled with the subsequent Tennis Court Oath where they vowed not to disperse until a new constitution was created, underscored a fundamental shift in authority from the monarchy to the people, setting a precedent for popular sovereignty that would resonate throughout the revolution.

Rise of the Third Estate

The Rise of the Third Estate underscores the growing power and assertiveness of the common people of France. Fueled by economic hardship, social inequality, and inspired by Enlightenment ideals, this diverse group—encompassing peasants, urban workers, and the bourgeoisie—began to challenge the existing social and political order.

Their transformation from a marginalized majority into the National Assembly marked a radical departure from traditional power structures, asserting their role as legitimate representatives of the French people. This period was characterized by significant political mobilization and the formation of popular societies and clubs, which played a crucial role in spreading revolutionary ideas and organizing action.

This newfound empowerment of the Third Estate culminated in key revolutionary acts, such as the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, a symbol of royal tyranny. This event not only demonstrated the power of popular action but also signaled the irreversible nature of the revolutionary movement.

The rise of the Third Estate paved the way for the abolition of feudal privileges and the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , foundational texts that sought to establish a new social and political order based on equality, liberty, and fraternity.

A People’s Monarchy

The concept of a People’s Monarchy emerged as a compromise in the early stages of the French Revolution, reflecting the initial desire among many revolutionaries to retain the monarchy within a constitutional framework.

This period was marked by King Louis XVI’s grudging acceptance of the National Assembly’s authority and the enactment of significant reforms, including the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the Constitution of 1791, which established a limited monarchy and sought to redistribute power more equitably.

However, this attempt to balance revolutionary demands with monarchical tradition was fraught with difficulties, as mutual distrust between the king and the revolutionaries continued to escalate.

The failure of the People’s Monarchy was precipitated by the Flight to Varennes in June 1791, when Louis XVI attempted to escape France and rally foreign support for the restoration of his absolute power.

This act of betrayal eroded any remaining support for the monarchy among the populace and the Assembly, leading to increased calls for the establishment of a republic.

The people’s experiment with a constitutional monarchy thus served to highlight the irreconcilable differences between the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and the traditional monarchical order, setting the stage for the republic’s proclamation.

Birth of a Republic

The proclamation of the First French Republic in September 1792 represented a radical departure from centuries of monarchical rule, embodying the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

This transition was catalyzed by escalating political tensions, military challenges, and the radicalization of the revolution, particularly after the king’s failed flight and perceived betrayal.

The Republic’s birth was a moment of immense optimism and aspiration, as it promised to reshape French society on the principles of democratic governance and civic equality. It also marked the beginning of a new calendar, symbolic of the revolutionaries’ desire to break completely with the past and start anew.

However, the early years of the Republic were marked by significant challenges, including internal divisions, economic struggles, and threats from monarchist powers in Europe.

These pressures necessitated the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror, measures aimed at defending the revolution but which also led to extreme political repression.

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror, from September 1793 to July 1794, remains one of the most controversial and bloodiest periods of the French Revolution. Under the auspices of the Committee of Public Safety, led by figures such as Maximilien Robespierre, the French government adopted radical measures to purge the nation of perceived enemies of the revolution.

This period saw the widespread use of the guillotine , with thousands executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activities or mere suspicion of disloyalty. The Terror aimed to consolidate revolutionary gains and protect the nascent Republic from internal and external threats, but its legacy is marred by the extremity of its actions and the climate of fear it engendered.

The end of the Terror came with the Thermidorian Reaction on 27th July 1794 (9th Thermidor Year II, according to the revolutionary calendar), which resulted in the arrest and execution of Robespierre and his closest allies.

This marked a significant turning point, leading to the dismantling of the Committee of Public Safety and the gradual relaxation of emergency measures. The aftermath of the Terror reflected a society grappling with the consequences of its radical actions, seeking stability after years of upheaval but still committed to the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality .

Thermidorians and the Directory

Following the Thermidorian Reaction , the political landscape of France underwent significant changes, leading to the establishment of the Directory in November 1795.

This new government, a five-member executive body, was intended to provide stability and moderate the excesses of the previous radical phase. The Directory period was characterized by a mix of conservative and revolutionary policies, aimed at consolidating the Republic and addressing the economic and social issues that had fueled the revolution.

Despite its efforts to navigate the challenges of governance, the Directory faced significant opposition from royalists on the right and Jacobins on the left, leading to a period of political instability and corruption.

The Directory’s inability to resolve these tensions and its growing unpopularity set the stage for its downfall. The coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, ended the Directory and established the Consulate, marking the end of the revolutionary government and the beginning of Napoleonic rule.

While the Directory failed to achieve lasting stability, it played a crucial role in the transition from radical revolution to the establishment of a more authoritarian regime, highlighting the complexities of revolutionary governance and the challenges of fulfilling the ideals of 1789.

French Revolution End and Outcome: Napoleon’s Rise

The revolution’s end is often marked by Napoleon’s coup d’état on 18 Brumaire , which not only concluded a decade of political instability and social unrest but also ushered in a new era of governance under his rule.

This period, while stabilizing France and bringing much-needed order, seemed to contradict the revolution’s initial aims of establishing a democratic republic grounded in the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Napoleon’s rise to power, culminating in his coronation as Emperor, symbolizes a complex conclusion to the revolutionary narrative, intertwining the fulfillment and betrayal of its foundational ideals.

Evaluating the revolution’s success requires a nuanced perspective. On one hand, it dismantled the Ancien Régime, abolished feudalism, and set forth the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, laying the cornerstone for modern democracy and human rights.

These achievements signify profound societal and legal transformations that resonated well beyond France’s borders, influencing subsequent movements for freedom and equality globally.

On the other hand, the revolution’s trajectory through the Reign of Terror and the subsequent rise of a military dictatorship under Napoleon raises questions about the cost of these advances and the ultimate realization of the revolution’s goals.

The French Revolution’s conclusion with Napoleon Bonaparte’s ascension to power is emblematic of its complex legacy. This period not only marked the cessation of years of turmoil but also initiated a new chapter in French governance, characterized by stability and reform yet marked by a departure from the revolution’s original democratic aspirations.

The Significance of the French Revolution

The French Revolution holds a place of prominence in the annals of history, celebrated for its profound impact on the course of modern civilization. Its fame stems not only from the dramatic events and transformative ideas it unleashed but also from its enduring influence on political thought, social reform, and the global struggle for justice and equality.

This period of intense upheaval and radical change challenged the very foundations of society, dismantling centuries-old institutions and laying the groundwork for a new era defined by the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

At its core, the French Revolution was a manifestation of human aspiration towards freedom and self-determination, a vivid illustration of the power of collective action to reshape the world. It introduced revolutionary concepts of citizenship and rights that have since become the bedrock of democratic societies.

Moreover, the revolution’s ripple effects were felt worldwide, inspiring a wave of independence movements and revolutions across Europe, Latin America, and beyond. Its legacy is a testament to the idea that people have the power to overthrow oppressive systems and construct a more equitable society.

The revolution’s significance also lies in its contributions to political and social thought. It was a living laboratory for ideas that were radical at the time, such as the separation of church and state, the abolition of feudal privileges, and the establishment of a constitution to govern the rights and duties of the French citizens.

These concepts, debated and implemented with varying degrees of success during the revolution, have become fundamental to modern governance.

Furthermore, the French Revolution is famous for its dramatic and symbolic events, from the storming of the Bastille to the Reign of Terror, which have etched themselves into the collective memory of humanity.

These events highlight the complexities and contradictions of the revolutionary process, underscoring the challenges inherent in profound societal transformation.

Key Figures of the French Revolution

The French Revolutions were painted by the actions and ideologies of several key figures whose contributions defined the era. These individuals, with their diverse roles and perspectives, were central in navigating the revolution’s trajectory, capturing the complexities and contradictions of this tumultuous period.

Maximilien Robespierre , often synonymous with the Reign of Terror, was a figure of paradoxes. A lawyer and politician, his early advocacy for the rights of the common people and opposition to absolute monarchy marked him as a champion of liberty.

However, as a leader of the Committee of Public Safety, his name became associated with the radical phase of the revolution, characterized by extreme measures in the name of safeguarding the republic. His eventual downfall and execution reflect the revolution’s capacity for self-consumption.

Georges Danton , another prominent revolutionary leader, played a crucial role in the early stages of the revolution. Known for his oratory skills and charismatic leadership, Danton was instrumental in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the First French Republic.

Unlike Robespierre, Danton is often remembered for his pragmatism and efforts to moderate the revolution’s excesses, which ultimately led to his execution during the Reign of Terror, highlighting the volatile nature of revolutionary politics.

Louis XVI, the king at the revolution’s outbreak, represents the Ancient Régime’s complexities and the challenges of monarchical rule in a time of profound societal change.

His inability to effectively manage France’s financial crisis and his hesitancy to embrace substantial reforms contributed to the revolutionary fervor. His execution in 1793 symbolized the revolution’s radical break from monarchical tradition and the birth of the republic.

Marie Antoinette, the queen consort of Louis XVI, became a symbol of the monarchy’s extravagance and disconnect from the common people. Her fate, like that of her husband, underscores the revolution’s rejection of the old order and the desire for a new societal structure based on equality and merit rather than birthright.

Jean-Paul Marat , a journalist and politician, used his publication, L’Ami du Peuple, to advocate for the rights of the lower classes and to call for radical measures against the revolution’s enemies.

His assassination by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer, in 1793 became one of the revolution’s most famous episodes, illustrating the deep divisions within revolutionary France.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte, though not a leader during the revolution’s peak, emerged from its aftermath to shape France’s future. A military genius, Napoleon used the opportunities presented by the revolution’s chaos to rise to power, eventually declaring himself Emperor of the French.

His reign would consolidate many of the revolution’s reforms while curtailing its democratic aspirations, embodying the complexities of the revolution’s legacy.

These key figures, among others, played significant roles in the unfolding of the French Revolution. Their contributions, whether for the cause of liberty, the maintenance of order, or the pursuit of personal power, highlight the multifaceted nature of the revolution and its enduring impact on history.

References:

(1) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 119-221.

(2) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 11-12

(3) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp. 56-57.

(4) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 24-25

(5) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 12-14.

(6) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 14-25

(7) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 63-65.

(8) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 242-244.

(9) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 74.

(10) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 82 – 84.

(11) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, p. 20.

(12) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 60-61.

(13) https://pages.uoregon.edu/dluebke/301ModernEurope/Sieyes3dEstate.pdf (14) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 104-105.

(15) French Revolution. “A Citizen Recalls the Taking of the Bastille (1789),” January 11, 2013. https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/humbert-taking-of-the-bastille-1789/.

(16) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 74-75.

(17) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 36-37.

(18) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From its origins to 1793. Routledge, 1957, pp. 121-122.

(19) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 428-430.

(20) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, p. 80.

(21) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 116-117.

(22) Fitzsimmons, Michael “The Principles of 1789” in McPhee, Peter, editor. A Companion to the French Revolution. Blackwell, 2013, pp. 75-88.

(23) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 68-81.

(24) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 45-46.

(25) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989,.pp. 460-466.

(26) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 524-525.

(27) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 47-48.

(28) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 51.

(29) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 128.

(30) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 30 -31.

(31) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp.. 53 -62.

(32) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 129-130.

(33) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 62-63.

(34) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 156-157, 171-173.

(35) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 65-66.

(36) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 543-544.

(37) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 179-180.

(38) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 184-185.

(39) Hampson, Norman. Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge, 1963, pp. 148-149.

(40) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 191-192.

(41) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From Its Origins to 1793. Routledge, 1962, pp. 252-254.

(42) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 88-89.

(43) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1990, pp. 576-79.

(44) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 649-51

(45) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 242-243.

(46) Connor, Clifford. Marat: The Tribune of the French Revolution. Pluto Press, 2012.

(47) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 722-724.

(48) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 246-47.

(49) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 209-210.

(50) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp 68-70.

(51) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 205-206

(52) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, 784-86.

(53) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 262.

(54) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 619-22.

(55) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 269-70.

(56) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 276.

(57) Robespierre on Virtue and Terror (1794). https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/robespierre-virtue-terror-1794/. Accessed 19 May 2020.

(58) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 290-91.

(59) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 293-95.

(60) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 49-51.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/the-french-revolution/ ">French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 12, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens radically altered their political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as the monarchy and the feudal system. The upheaval was caused by disgust with the French aristocracy and the economic policies of King Louis XVI, who met his death by guillotine, as did his wife Marie Antoinette. Though it degenerated into a bloodbath during the Reign of Terror, the French Revolution helped to shape modern democracies by showing the power inherent in the will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution , combined with extravagant spending by King Louis XVI , had left France on the brink of bankruptcy.

Not only were the royal coffers depleted, but several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.

In the fall of 1786, Louis XVI’s controller general, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, proposed a financial reform package that included a universal land tax from which the aristocratic classes would no longer be exempt.

Estates General

To garner support for these measures and forestall a growing aristocratic revolt, the king summoned the Estates General ( les états généraux ) – an assembly representing France’s clergy, nobility and middle class – for the first time since 1614.

The meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789; in the meantime, delegates of the three estates from each locality would compile lists of grievances ( cahiers de doléances ) to present to the king.

Rise of the Third Estate

France’s population, of course, had changed considerably since 1614. The non-aristocratic, middle-class members of the Third Estate now represented 98 percent of the people but could still be outvoted by the other two bodies.

In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate began to mobilize support for equal representation and the abolishment of the noble veto—in other words, they wanted voting by head and not by status.

While all of the orders shared a common desire for fiscal and judicial reform as well as a more representative form of government, the nobles in particular were loath to give up the privileges they had long enjoyed under the traditional system.

Tennis Court Oath

By the time the Estates General convened at Versailles , the highly public debate over its voting process had erupted into open hostility between the three orders, eclipsing the original purpose of the meeting and the authority of the man who had convened it — the king himself.

On June 17, with talks over procedure stalled, the Third Estate met alone and formally adopted the title of National Assembly; three days later, they met in a nearby indoor tennis court and took the so-called Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

Within a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles had joined them, and on June 27 Louis XVI grudgingly absorbed all three orders into the new National Assembly.

The Bastille

On June 12, as the National Assembly (known as the National Constituent Assembly during its work on a constitution) continued to meet at Versailles, fear and violence consumed the capital.

Though enthusiastic about the recent breakdown of royal power, Parisians grew panicked as rumors of an impending military coup began to circulate. A popular insurgency culminated on July 14 when rioters stormed the Bastille fortress in an attempt to secure gunpowder and weapons; many consider this event, now commemorated in France as a national holiday, as the start of the French Revolution.

The wave of revolutionary fervor and widespread hysteria quickly swept the entire country. Revolting against years of exploitation, peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and the aristocratic elite.

Known as the Great Fear ( la Grande peur ), the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from France and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism on August 4, 1789, signing what historian Georges Lefebvre later called the “death certificate of the old order.”

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

IIn late August, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen ( Déclaration des droits de l ’homme et du citoyen ), a statement of democratic principles grounded in the philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The document proclaimed the Assembly’s commitment to replace the ancien régime with a system based on equal opportunity, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty and representative government.

Drafting a formal constitution proved much more of a challenge for the National Constituent Assembly, which had the added burden of functioning as a legislature during harsh economic times.

For months, its members wrestled with fundamental questions about the shape and expanse of France’s new political landscape. For instance, who would be responsible for electing delegates? Would the clergy owe allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church or the French government? Perhaps most importantly, how much authority would the king, his public image further weakened after a failed attempt to flee the country in June 1791, retain?

Adopted on September 3, 1791, France’s first written constitution echoed the more moderate voices in the Assembly, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the king enjoyed royal veto power and the ability to appoint ministers. This compromise did not sit well with influential radicals like Maximilien de Robespierre , Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, who began drumming up popular support for a more republican form of government and for the trial of Louis XVI.

French Revolution Turns Radical

In April 1792, the newly elected Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and Prussia, where it believed that French émigrés were building counterrevolutionary alliances; it also hoped to spread its revolutionary ideals across Europe through warfare.

On the domestic front, meanwhile, the political crisis took a radical turn when a group of insurgents led by the extremist Jacobins attacked the royal residence in Paris and arrested the king on August 10, 1792.

The following month, amid a wave of violence in which Parisian insurrectionists massacred hundreds of accused counterrevolutionaries, the Legislative Assembly was replaced by the National Convention, which proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French republic.

On January 21, 1793, it sent King Louis XVI, condemned to death for high treason and crimes against the state, to the guillotine ; his wife Marie-Antoinette suffered the same fate nine months later.

Reign of Terror

Following the king’s execution, war with various European powers and intense divisions within the National Convention brought the French Revolution to its most violent and turbulent phase.

In June 1793, the Jacobins seized control of the National Convention from the more moderate Girondins and instituted a series of radical measures, including the establishment of a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity .

They also unleashed the bloody Reign of Terror (la Terreur), a 10-month period in which suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands. Many of the killings were carried out under orders from Robespierre, who dominated the draconian Committee of Public Safety until his own execution on July 28, 1794.

Did you know? Over 17,000 people were officially tried and executed during the Reign of Terror, and an unknown number of others died in prison or without trial.

Thermidorian Reaction

The death of Robespierre marked the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction, a moderate phase in which the French people revolted against the Reign of Terror’s excesses.

On August 22, 1795, the National Convention, composed largely of Girondins who had survived the Reign of Terror, approved a new constitution that created France’s first bicameral legislature.

Executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory ( Directoire ) appointed by parliament. Royalists and Jacobins protested the new regime but were swiftly silenced by the army, now led by a young and successful general named Napoleon Bonaparte .

French Revolution Ends: Napoleon’s Rise

The Directory’s four years in power were riddled with financial crises, popular discontent, inefficiency and, above all, political corruption. By the late 1790s, the directors relied almost entirely on the military to maintain their authority and had ceded much of their power to the generals in the field.

On November 9, 1799, as frustration with their leadership reached a fever pitch, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “ first consul .” The event marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era, during which France would come to dominate much of continental Europe.

Photo Gallery

French Revolution. The National Archives (U.K.) The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State . Versailles, from the French Revolution to the Interwar Period. Chateau de Versailles . French Revolution. Monticello.org . Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French Revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

French Revolution: Essay & Important Notes

What led to the french revolution.

At the close of the 18 th century, France had been long involved in the American Revolution and the extravagant spending of King Louis XVI led France to bankruptcy. Additionally, the common people of France were caught in a vicious cycle of poor harvest, cattle disease, and the increasing prices of bread. This led to widespread discontent and made the people revolt against the monarchy.

Prominent Events of the French Revolution

The entire period of the French Revolution saw several events. Some of the prominent ones include:

Rise of the Third Estate

The population of France had been changing for a long time and non-aristocratic members formed a major part of the Third Estate. However, the Third Estate was not provided equivalent powers and by 1798 began to mobilize for equal representation and wanted voting by head and not by status. The nobles were, however, not ready to part with their privileges and powers.

Tennis Court Oath

With increasing hostility between the three orders about the voting rights of the Third Estate, the title of the National Assembly was adopted by it at an indoor tennis court and took the Tennis Court Oath vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

The Bastille and Great Fear

As the National Assembly continued its work, violence and fear had consumed the capital city. The rumors of an impending military coup further put the people of Paris in fear. Many rioters marched into the Bastille fortress to collect gunpowder and weapons and this is what marked the beginning of the French Revolution. The revolutionary fear spread far and wide and peasants looted and burned homes of tax collectors and landlords who had exploited them. This agrarian revolt is termed as Great Fear and led the National Assembly to abolish feudalism in August 1789.

Declaration of Rights

The National Assembly adopted the Declaration of Rights of Man and of the citizen in August 1789. The declaration proclaimed to replace the ancient regime with a system based on equal opportunities, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty, and representative government.

Reign of Terror

During the French Revolution, the period marred with a lot of violence was known as the Reign of Terror. It was during this period that the revolution turned radical and King Louis XVI was sent to death from treason.

Violence during the French Revolution

End of the French Revolution

In 1795, the National Convention created the first bicameral legislature of France. The executive power was given to the five-member Directory. However, the members of the Directory were involved in corruption, inefficiency as well as the financial crisis. By the 1790s, most of the members of the Directory had ceded much of their power to the military generals. In 1799, frustrated with the leadership, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup and abolished the Directory, and appointed himself as France’s “first consul.” This led to the end of the French Revolution.

Important Notes

- French Revolution was started to bring about political changes in France.

- The revolution aimed to create a free and sovereign France.

- There were several important events during the French Revolution that were marred by violence and revolts by peasants.

The revolution came to an end with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Related Posts

The Ideas of Giuseppe Mazzini

Fall of Constantinople Effects

Industrial Revolution: Essay & Important Notes

Crisis of Feudalism

Quit India Movement: Essay and Important Facts

Civil Disobedience Movement: Essay & Important Notes

Add comment cancel reply.

French Revolution

French revolution essay questions, france before 1789.

1. Evaluate the French royal court at Versailles, why it existed and the contribution it made to French government and society.

2. “The French nobility did little but concern themselves with leisure, finery, decadence, affairs and intrigues.” To what extent is this statement true in the context of late 18th century France?

3. The presence of things like lettres du cachet and the Bastille give the impression that pre-revolutionary France was an authoritarian society that oppressed personal liberty and freedom. To what extent was this true?

4. Examine the role of religion in 18th century France, both in ideological and practical terms. How did ordinary French people view the Catholic church and its clergy?

5. Identify and discuss tensions between the Three Estates that may have contributed to revolutionary sentiment in 18th century France.

6. To what extent was feudalism a cause of the French Revolution? Describe how feudal bonds and dues impacted on the ordinary people of France during the 18th century.

7. Explain why the taxation regime and the collection of tax revenue in 18th century France failed to meet the fiscal requirements of the nation.

8. Some historians argue that commerce and trade in France were restricted by regulations that were overbearing, complex and inconsistent. What were the grievances of the merchant and capitalist class in pre-revolutionary France?

9. Discuss how the strains and stresses of imperialism might have weakened the domestic government in 18th century France, paving the way for revolutionary sentiment.

10. Consider the political, economic and social position of women in 18th century France. Did the women of France have more motivation or potential for revolution than the men?

Government and royalty in the ancien regime

1. Louis XIV is once reported as saying “L’etat, c’est moi” (‘The state is me’). To what extent was this true, both of Louis XIV and his two successors?

2. Describe the relationship between the Bourbon monarchy and the French people in the century before 1789. How did French kings impose their will on the nation?

3. In what ways did the Roman Catholic religion support the Bourbon monarchy – and how was the church itself supported by the state?

4. Discuss the relationship between the Bourbon monarchy and the Second Estate. How did tensions between the king and his nobles shape the political landscape?

5. Evaluate Louis XVI and his character, personal abilities and his suitability for leadership. Was he a flawed king, or simply a victim of circumstance?

6. Critically examine the relationship between Louis XVI and his ministers during the 1780s.

7. Explain why Marie Antoinette was a target for intrigue, gossip and propagandists. To what extent was her reputation deserved?

8. The extravagant spending of the royal family is often advanced as a major cause of the French Revolution. To what extent was this true?

9. Explain how the ideological foundations of the French monarchy were challenged and possibly undermined by Enlightenment philosophers and writers.

10. According to Simon Schama, the Bourbon monarchy was threatened by “whispering campaigns”. To what is he referring to, and how did they endanger the monarchy?

The troubled 1780s

1. Giving close attention to specific writers, explain how the Enlightenment challenged and undermined the old regime in 18th century France.

2. What contribution did salons , cafes and other social gatherings make to the rising revolutionary sentiment of the 1780s?

3. “The libelles and political pornography of the 1780s contained no significant political ideas so had little impact on the old regime”. To what extent was this true?

4. Identify and discuss two individuals who attempted to achieve fiscal and political reform in France during the 1780s. To what extent were they successful?

5. Explain how France’s involvement in the American Revolutionary War impacted on the nation in moral, ideological and practical terms.

6. Discuss the actions of the parlements and the Assembly of Notables in the late 1780s. How did these bodies contribute to the developing revolution?

7. Explain the events of 1788 that led to Louis XVI calling for the convocation of the Estates-General.

8. What were the Cahiers de Doleances and what did they suggest about the mood of the French people on the eve of the revolution?

9. Why did French harvests fail in the late 1780s, leading to a downturn in agricultural production? What impact did this have on the lives of ordinary people?

10. What factors and forces led to the failure of reformist policies in the 1780s? Did these reforms fail because of resistant conservative interests or a disinterested, incompetent royal government?

The drama of 1789

1. Who was the Abbe Sieyes and what contribution did he make to the French Revolution, both in ideological and practical terms?

2. What happened at the Reveillon factory in Paris in April 1789? What working class grievances, fears and rumours triggered these events?

3. Explain how issues of ceremony, procedure and voting created divisions within the Estates-General when it met in mid-1789.

4. For what reasons did the National Assembly form in June 1789? Was the formation of this body inevitable – or did it occur because of chance and circumstance?

5. “From the beginning of 1789, the push for economic and fiscal reform in France became a push for political reform.” Explain the meaning of this statement, referring to key ideas and events of 1789.

6. Discuss the context, reasons and outcomes of the sacking of Jacques Necker on July 11th 1789. What impact did this have on the unfolding revolution?

7. Why has the storming of the Bastille become the best-known event of the French Revolution? What were the outcomes of this event, in both real and symbolic terms?

8. What were the causes and outcomes of the Great Fear? Was this event evidence that the French peasantry was a revolutionary class?

9. Why did the newly formed National Constituent Assembly move to abolish feudalism in France on August 4th? How sincere were these reforms and did they last?

10. On the surface, the relocation of the royal family from Versailles to Paris, a few miles away, seems a minor event. Was this really the case? Why did the king and his family relocate and what impact did this have on the revolution?

Creating a new society

1. Examine the background, motives and political values of those who sat in the National Constituent Assembly between 1789 and its dissolution in 1791.

2. What steps did the National Constituent Assembly take to abolish or replace the political institutions and social inequalities of the ancien regime ?

3. While many aspects of the French Revolution have been forgotten or discredited, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen has endured. Summarise the political values and ideas contained in this critical document.

4. The most influential political figure of 1789-1791, argue many historians, is the Marquis de Lafayette. Describe Lafayette’s background, attributes and political values. To what extent did he truly represent the revolution in France?

5. Evaluate the political leadership of Honore Mirabeau in the revolution between June 1789 and his death in April 1791. Did Mirabeau seek to advance revolutionary change – or to restrict it?

6. What were the political, social and economic objectives of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy? Discuss the impact this reform had on the clergy, the king and the French people in general?

7. How successful was the National Constituent Assembly in resolving the economic and fiscal problems of the ancien regime ? Refer to three specific policies in your answer.

8. Evaluate the relationship between the National Constituent Assembly and the French peasantry and working classes. Did the Assembly implement policies that improved living and working conditions for ordinary people?

9. To what extent did the revolution enjoy popular support around France by the end of 1790? Which people, groups or regions were actively opposing the revolution?

10. What was the ‘flight to Varennes’ and why did it change the political landscape in the new society?

The descent into radicalism

1. What were the causes and outcomes of the Champ de Mars massacre? How and why did this event change the development of the new society?

2. Evaluate the brief life and political impact of the Legislative Assembly. Did this body suffer from internal failings – or was it simply a victim of treacherous times?

3. Discuss the fate of the moderate leaders Mirabeau, Lafayette and Bailly during the radical period. What were the events and factors that undermined their leadership?

4. How did France come to find itself at war with other European powers from 1792 onwards? What impact did war have on the government?

5. Explain how radical writers like Jean-Paul Marat and Camille Desmoulins influenced the development of the new society between 1789 and 1794.

6. What were the political clubs and what role did they play in the evolving new society? Discuss three specific clubs in your answer.

7. Why is August 10th 1792 considered a pivotal day in the course of the revolution? What impact did the events of this day have on French government and society?

8. Evaluate the fate of the king between June 1791 and his execution in January 1793. Could Louis XVI have saved himself – or was he already doomed?

9. Who were the sans-culottes and what were their grievances? Referring to at least three specific events, explain how they influenced the national government between 1791 and 1793.

10. Explain the composition of the National Convention and its various political divisions and factions.

The Terror and beyond

1. In what ways was French society reformed and reinvented between 1792 and 1794? Identify and discuss five elements of the ancien regime and its society that were abolished or reformed by the National Convention.

2. What was the Committee of Public Safety? How did this body come to possess arbitrary power – and what did it do with this power?

3. Identify and discuss three events or factors that you believe were the most significant causes of the Reign of Terror.

4. Explain the purpose and operation of the Paris Revolutionary Tribunal. How did these change as the Terror intensified in late 1793 and 1794?

5. Discuss the arguments advanced by Robespierre and his followers to justify the use of revolutionary terror.

6. What was the Cult of the Supreme Being and how successful was it in achieving its objectives?