Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Status | |

| Version | |

| Ad File | |

| Disable Ads Flag | |

| Environment | |

| Moat Init | |

| Moat Ready | |

| Contextual Ready | |

| Contextual URL | |

| Contextual Initial Segments | |

| Contextual Used Segments | |

| AdUnit | |

| SubAdUnit | |

| Custom Targeting | |

| Ad Events | |

| Invalid Ad Sizes |

Access provided by

Download started.

- PDF [1 MB] PDF [1 MB]

- Figure Viewer

- Download Figures (PPT)

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

Associations of time spent on homework or studying with nocturnal sleep behavior and depression symptoms in adolescents from Singapore

- Sing Chen Yeo, MSc Sing Chen Yeo Affiliations Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore Search for articles by this author

- Jacinda Tan, BSc Jacinda Tan Affiliations Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore Search for articles by this author

- Joshua J. Gooley, PhD Joshua J. Gooley Correspondence Corresponding author: Joshua J. Gooley, Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders Program, Duke-NUS Medical School Singapore, 8 College Road, Singapore 117549, Singapore Contact Affiliations Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Program in Neuroscience and Behavioral Disorders, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore Search for articles by this author

Participants

Measurements, conclusions.

- Sleep deprivation

Introduction

- Dewald J.F.

- Meijer A.M.

- Kerkhof G.A.

- Scopus (1045)

- Google Scholar

- Gooley J.J.

- Scopus (234)

- Chaput J.P.

- Poitras V.J.

- Scopus (558)

- Crowley S.J.

- Wolfson A.R.

- Carskadon M.A

- Scopus (397)

- Roenneberg T.

- Pramstaller P.P.

- Full Text PDF

- Scopus (1143)

- Achermann P.

- Scopus (354)

- Gradisar M.

- Scopus (83)

- Watson N.F.

- Martin J.L.

- Scopus (84)

- Robinson J.C.

- Scopus (670)

- Street N.W.

- McCormick M.C.

- Austin S.B.

- Scopus (16)

- Scopus (297)

- Scopus (300)

- Twenge J.M.

- Scopus (148)

- Galloway M.

- Scopus (67)

- Huang G.H.-.C.

- Scopus (124)

Participants and methods

Participants and data collection.

- Scopus (81)

Assessment of sleep behavior and time use

- Scopus (1330)

- Carskadon M.A.

- Scopus (565)

Assessment of depression symptoms

- Brooks S.J.

- Krulewicz S.P.

- Scopus (62)

Data analysis and statistics

- Fomberstein K.M.

- Razavi F.M.

- Scopus (56)

- Fuligni A.J.

- Scopus (238)

- Miller L.E.

- Scopus (445)

- Preacher K.J.

- Scopus (23450)

| Time spent on activities (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily activities | School days | Weekends | Cohen's d | ||

| Time in bed for sleep | 6.57 ± 1.23 | 8.93 ± 1.49 | −49.0 | <0.001 | −1.73 |

| Lessons/lectures/lab | 6.46 ± 1.11 | 0.07 ± 0.39 | 194.9 | <0.001 | 7.68 |

| Homework/studying | 2.87 ± 1.46 | 4.47 ± 2.45 | −30.0 | <0.001 | −0.79 |

| Media use | 2.06 ± 1.27 | 3.49 ± 2.09 | −32.4 | <0.001 | −0.83 |

| Transportation | 1.28 ± 0.65 | 0.98 ± 0.74 | 11.4 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Co-curricular activities | 1.22 ± 1.17 | 0.22 ± 0.69 | 28.4 | <0.001 | 1.04 |

| Family time, face-to-face | 1.23 ± 0.92 | 2.70 ± 1.95 | −32.5 | <0.001 | −0.97 |

| Exercise/sports | 0.86 ± 0.86 | 0.91 ± 0.97 | −2.2 | 0.031 | −0.06 |

| Hanging out with friends | 0.59 ± 0.77 | 1.24 ± 1.59 | −15.2 | <0.001 | −0.52 |

| Extracurricular activities | 0.32 ± 0.65 | 0.36 ± 0.88 | −1.9 | 0.057 | −0.06 |

| Part-time job | 0.01 ± 0.13 | 0.03 ± 0.22 | −2.4 | 0.014 | −0.08 |

- Open table in a new tab

- View Large Image

- Download Hi-res image

- Download (PPT)

- Scopus (35)

- Scopus (18)

- Scopus (59)

- Scopus (164)

- Scopus (85)

- Maddison R.

- Scopus (61)

- Lushington K.

- Pallesen S.

- Stormark K.M.

- Jakobsen R.

- Lundervold A.J.

- Sivertsen B

- Scopus (355)

- Scopus (32)

- Afzali M.H.

- Scopus (227)

- Abramson L.Y

- Scopus (1274)

- Spaeth A.M.

- Scopus (110)

- Gillen-O'Neel C.

- Fuligni A.J

- Scopus (77)

- Felden E.P.

- Rebelatto C.F.

- Andrade R.D.

- Beltrame T.S

- Twan D.C.K.

- Karamchedu S.

- Scopus (26)

Conflict of interest

Acknowledgments, appendix. supplementary materials.

- Download .docx (.51 MB) Help with docx files

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Article info

Publication history, identification.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2020.04.011

User license

For non-commercial purposes:

- Read, print & download

- Redistribute or republish the final article

- Text & data mine

- Translate the article (private use only, not for distribution)

- Reuse portions or extracts from the article in other works

Not Permitted

- Sell or re-use for commercial purposes

- Distribute translations or adaptations of the article

ScienceDirect

- Download .PPT

Related Articles

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Information

- Download Conflict of Interest Form

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Style Guidelines for In Memoriam

- Download Online Journal CME Program Application

- NSF CME Mission Statement

- Professional Practice Gaps in Sleep Health

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Activate Online Access

- Information for Advertisers

- Career Opportunities

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

- Press Releases

- More Periodicals

- Find a Periodical

- Go to Product Catalog

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

- Close Menu Search

- Recommend a Story

The Lion's Roar

May 24 Party Like It’s 1989: Lions Capture the 2024 Diamond Classic

May 24 Why Does the Early 20th Century Tend to Spark Nostalgia?

May 24 O.J Simpson Dead at 76: Football Star Turned Murderer

May 24 NAIA Bans Transgender Women From Women’s Sports

May 24 From Papyrus to Ashes: The Story of the Great Library of Alexandria

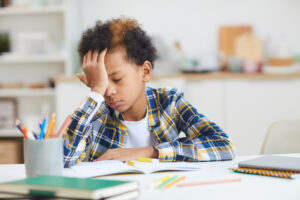

The Effects Homework Can Have On Teens’ Sleeping Habits

Jess Amabile '24 and February 25, 2021

Ever wonder why you feel like you never get enough sleep? Here’s a pretty good reason: large amounts of homework can be detrimental to a teen’s sleeping habits, even more so with high schoolers.

There have been many studies recently about the damage homework has to students’ health, mainly concerning lack of sleep in teenagers. According to an article published by US News called “The Importance of Sleep for Teen Mental Health” , it states that “ surveys show that less than 9 percent of teens get enough sleep”. This fact is devastating, especially considering the fact that teenagers take up about thirteen percent of the country’s population.

Also mentioned in “The Importance of Sleep for Teen Mental Health” , “ about forty-one million Americans get six or fewer hours of sleep per night”. If teenagers see their parents not getting enough sleep, it can convince them that there are things more important than sleep, such as something almost every teenager in America has to deal with–homework.

Homework is pretty stressful for teens, especially if they have other things to do. Many teens have long hours at school, which limits the time for them to do their insane amount of homework, attend extra-curricular activities, eat, do whatever they need to around the house, and sleep. And usually, sleeping is the last thing on the list of things to do before school the next day. Another article, “What’s preventing adequate teen sleep” , states that, “Homework is possibly the biggest factor that keeps teens from getting enough sleep…The sheer quantity of homework absorbs hours that should be dedicated to sleep”. Students generally have so much homework that they don’t have enough time to do everything else they need to do that day. So, sleeping is often the first thing teens eliminate from their schedule.

According to Oxford Learning , homework can have other negative effects on students. In their article, Oxford Learning remarks, “56 percent of students considered homework a primary source of stress. Too much homework can result in lack of sleep, headaches, exhaustion, and weight loss”.

Similarly, Stanford Medicine News Center reports that the founder of the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic stated, “‘I think high school is the real danger spot in terms of sleep deprivation,’ said William Dement, MD, Ph.D.”. Sleep deprivation is a real problem for high school students, and Stanford Medicine News Center continues on this topic by commenting, “Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts. It’s a problem that knows no economic boundaries”. If students are constantly battling sleep deprivation, how can they concentrate on schoolwork, or even be able to perform everyday tasks? This shows that homework greatly affects students in both mental and physical ways. If something is supposed to continue a lesson that was learned in school, why is it negatively affecting students’ lives?

Ask yourself: is homework really worth the extremely negative effects?

“What’s preventing adequate teen sleep”

http://sleepeducation.org/news/2017/07/26/what-is-preventing-adequate-teen-sleep

“The Importance of Sleep for Teen Mental Health”

https://health.usnews.com/health-care/for-better/articles/2018-07-02/the-importance-of-sleep-for-teen-mental-health

Oxford Learning

https://www.oxfordlearning.com/how-does-homework-affect-students/#:~:text=How%20Does%20Homework%20Affect%20Students,headaches%2C%20exhaustion%20and%20weight%20loss.

Stanford Medicine News Center

https://med.stanford.edu/news.html

What time should high school should start?

- 7:00 AM or earlier

- 7:30 AM (Current Start Time)

- After 9:00 AM

View Results

- Polls Archive

The Rebellion Against Instagram’s Unrealistic Body Expectations

News Consumption On Social Media

The Sound of Music

3 Underrated Old Hollywood Actresses That Everyone Should Know

The Timeline of Shirley Chisholm

6 Influential Black Americans That Schools Failed to Teach You About

West Lions Save Lives: SGO’s 2024 Blood Drive

TIMELINE: The College Application Process

Santa Claus: Has He Become a Fraud and Only a Model for Greed to Children?

George Santos Expelled From House of Representatives

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

We don't ship to your address!

- Choose your country

- Czech Republic

- Liechtenstein

- The Netherlands

- The United Kingdom

- kr. DANSK KRONE

- € EURO

- Ft MAGYAR FORINT

- £ POUND

- kr SVENSK KRONA

- zł ZłOTY

We're here to help

- Customer service

- Business-to-Business

- Shipping information

- Frequently asked questions

- Terms and Conditions

No products

You have to add to cart at least 0 bottles or any program to make checkout.

We are here to help you

How Does Homework Affect Students Sleep?

Published: June 21st, 2023

Exploring how homework affects students' sleep is an essential part of understanding the overall health and academic performance of our youth. The correlation between heavy workload from assignments and sleep deprivation has been a subject of multiple studies, with compelling findings.

Understanding the correlation between homework and teenage stress

Exploring the impact on quality sleep due to excessive homework, how late-night study impacts the circadian rhythm, the link between disturbed sleep patterns and academic performance, unpacking research findings linking heavy homework load with mental health issues, implications for future educational policies regarding home-based tasks, evaluating pros & cons related to assigning extensive workloads at elementary levels, suggesting alternatives for effective learning without compromising children's wellbeing, alfie kohn's perspective on education system practices, proposing changes toward balanced school schedules, assessing potential benefits shifting school start times based upon nsf recommendations, effective time management strategies, the impact of sleep deprivation on students, does homework affect sleep schedules, what percentage of students lose sleep due to homework, why does school cause sleep deprivation, why is sleep more important than homework.

This blog post delves into the impact that excessive homework can have on high school students' quality sleep, and how it might disrupt their natural circadian rhythm or sleep cycle. We will also explore its implications on mental health issues among younger kids who are often encouraged to go to bed earlier but struggle due to late-night study sessions.

The role of American education system practices in contributing to student's lack of adequate rest will be examined along with Alfie Kohn’s perspective about current education policies. Additionally, we'll discuss early school start times as another potential burden leading towards disturbed sleeping patterns.

Finally, we aim at proposing some changes for more balanced school schedules and providing tips for effectively managing time amidst academic responsibilities and extracurricular activities without being sleep deprived.

The Impact of Homework on Teenage Stress and Sleep

Homework is a major source of stress for teenagers, affecting their sleep patterns. According to studies, about 75% of high school students report grades and homework as significant stressors. This anxiety can lead to sleep deprivation, with over 50% of students reporting insufficient rest.

A heavy workload not only affects academic performance but also disrupts the normal sleep cycle. The pressure to excel academically leads many students into a vicious cycle where they stay up late completing tasks, wake up early for school, and end up being sleep deprived.

This lack of rest impairs cognitive functions like memory retention and problem-solving skills - both crucial for academic success. Furthermore, inadequate sleep may lead to ailments such as reduced immunity or persistent tiredness.

Sleep experts recommend that younger kids should go to bed earlier than teens because their biological clock naturally prompts them to feel sleepy around 8-9 PM. However, this becomes challenging when burdened with loads of assignments which extend their screen time significantly beyond recommended limits.

The blue light emitted by electronic devices used for studying suppresses melatonin production - a hormone that regulates our body's internal clock determining when we feel sleepy or awake (National Sleep Foundation). Consequently, these factors combined make falling asleep more difficult leading towards disrupted sleeping patterns ultimately affecting overall well-being including mental health status alongside academic performance negatively.

In conclusion, there needs to be an urgent reevaluation of how much work is assigned outside class hours considering potential adverse effects upon student's health, especially concerning adequate rest necessary for optimal functioning throughout day-to-day activities, whether within academia or other extracurricular responsibilities undertaken during leisure periods post-school schedules.

Analyzing Sleep Patterns Among Stressed Students

High schoolers are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of sleep deprivation due to the demands of juggling academics and extracurriculars. The pressure of balancing academics with extracurricular activities can lead to late nights and early mornings, leaving them feeling perpetually tired and impacting their academic performance.

The human body operates on a 24-hour internal clock known as the circadian rhythm. This biological process regulates our sleep-wake cycle, among other things. When students stay up late studying or completing homework, they disrupt this natural rhythm which can result in a range of health issues including chronic fatigue and weakened immunity.

Screen time is another factor that exacerbates this issue. Many students use electronic devices for research or writing assignments before bed, exposing themselves to blue light which further interferes with their circadian rhythms.

Regular slumber is a must for cognitive functions, such as memory consolidation and problem-solving aptitude - fundamental aspects of learning. Multiple studies have shown that when these patterns are disturbed due to excessive homework or late-night study sessions, it can negatively affect academic performance.

- Poor Concentration: Lack of adequate rest makes focusing on tasks more difficult, leading to decreased productivity during study hours.

- Inability To Retain Information: During deep stages of sleep, information from short-term memory gets transferred into long-term storage enabling better recall later; deprived individuals miss out on this critical process.

- Deteriorating Mental Health: Chronic lack of rest has been linked with increased levels of anxiety and depression amongst teenagers, impacting overall wellbeing and indirectly affecting grades too.

A report by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suggests there's an urgent need for schools to address these concerns seriously, considering the potential repercussions over students' physical and mental health alongside scholastic achievements. Making sure they get enough quality rest each night is essential for optimal functioning throughout the day, both inside and outside the classroom environments.

Investigating Time Spent on Homework and Its Effects on Mental Health

The amount of time spent on homework and studying significantly affects students' mental health. Multiple studies have shown that an excessive workload can lead to depression, stress, and sleep deprivation .

A comprehensive study involving 2386 adolescents assessed various aspects, including self-rated health, overweight status, and depression symptoms, alongside time spent on homework/studying. The researchers used ten different multiple linear regression models to test the association with the global Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale score. This approach allowed them to analyze how each aspect correlates with the others.

The results were revealing: there was a clear correlation between increased hours dedicated to home-based tasks and higher levels of depressive tendencies among high school students . These effects weren't limited only to academic performance but extended into their personal lives as well, affecting relationships, participation rates in extracurricular activities , and more.

This data suggests that we need a more balanced approach when it comes to assigning workloads at schools. Instead of piling up assignments indiscriminately, educators should aim for an optimal balance where learning is enhanced rather than hindered by excessive amounts of homework.

In light of this information, some countries are already taking steps towards reducing screen time requirements, especially during after-school hours. This allows younger kids to go to bed earlier, improving their sleep cycle quality significantly, which ultimately leads to better cognitive functioning the next day at school or other engagements they might have outside the academic context, like part-time jobs or family duties.

To sum up, a healthy balance between academic and other life obligations is essential to avoid potential repercussions in all aspects of a student's life. Neglecting to strike a balance between academic and other responsibilities can have severe repercussions, not only in terms of grades but also emotionally, socially, and mentally. Therefore, it is imperative to address this issue promptly and effectively with all stakeholders involved in the education sector worldwide today, tomorrow, and onwards too.

Excessive Workload Strain from Assignments in Younger Kids

The ongoing discussion about the implications of homework for younger students has drawn attention from educators, parents, and researchers. While assignments can reinforce what students learn during school hours, evidence supporting benefits from home-based tasks remains scarce before high-school levels. This is concerning considering the potential adverse effects an excessive workload can have on young minds.

On one hand, homework can instill discipline and help develop good study habits. On the other hand, too much of it could lead to sleep deprivation among younger kids who should ideally be going to bed earlier. The AAP suggests that 6-12 year olds should have 9-12 hours of rest, however this can be hard to attain when they are inundated with assignments.

Besides affecting their sleep cycle, overburdening them with academic responsibilities also leaves little room for extracurricular activities which play a crucial role in their overall development. It may even result in screen time replacing physical activity as children turn towards digital platforms to complete their assignments.

Rather than piling up work indiscriminately, schools could consider adopting strategies aimed at enhancing learning while ensuring the well-being of students. For instance, project-based learning could be an effective alternative where students actively explore real-world problems and challenges, thereby gaining deeper knowledge.

In addition to this approach would be limiting daily homework duration per grade level or introducing "homework-free" days during weekends or holidays providing ample rest periods essential for growth development amongst younger kids.

This shift not only ensures that our future generations aren't sleep deprived due to unnecessary academic pressure but also fosters a love for lifelong learning - something far more valuable than mere grades obtained through rote memorization.

American Education's Role In Student Sleep Deprivation

It's common for students in the US to be sleep deprived , not just because of academic pressures but also due to extracurricular activities . Late nights and early mornings disrupt a healthy sleep cycle , affecting student wellbeing.

Educational critic Alfie Kohn argues that the American education system emphasizes homework without considering its impact on student wellbeing. Many tasks assigned do not enhance learning but rather contribute towards stress and sleep deprivation among students. You can read more about his thoughts in his article titled " The Truth About Homework: Needless Assignments Persist Because of Widespread Misconceptions About Learning. "

Kohn suggests a shift towards assigning work aimed at enhancing learning rather than piling it up indiscriminately. Schools should recognize the importance of adequate rest for optimal functioning.

- Reduce homework loads: Lightening the load could help alleviate some of the pressure students feel, allowing them time to relax and get enough sleep each night.

- Consider late start times: Multiple studies suggest that starting school later in the morning could have numerous benefits including improved attendance rates and higher alertness, reducing instances of depressive tendencies significantly. (National Sleep Foundation (NSF))

- Promote good sleep hygiene: Schools can educate students about good sleep habits such as maintaining consistent bedtimes and wake-up times, limiting screen time before bedtime, and creating quiet, dark sleeping environments.

The key takeaway here is balance - between academics, extracurricular activities, family responsibilities, and personal downtime - which includes getting sufficient restful sleep every night.

Early School Start Times - An Additional Burden

Many adolescents in the US are finding that having to get up at sunrise is more of an encumbrance than a blessing. Parents and educators alike have reported that these early start times are inhibiting productivity throughout daytime schedules.

The National Sleep Foundation (NSF), an organization dedicated to improving health and well-being through sleep education and advocacy, suggests shifting school timings as one possible solution. This adjustment could result in improved attendance rates along with higher alertness among students during class hours.

The NSF study indicated that adjusting the school start time from 7:30 AM to 8:30 AM produced tangible improvements in student performance. The extra hour allowed teenagers' natural sleep cycle to align better with their academic schedule leading them to feel less sleep deprived.

- Better Attendance: Schools noted fewer tardies and absences after implementing later start times.

- Increase In Grades: Students showed improvement in core subjects like Math and English.

- Mental Health Benefits: A decrease was observed in instances of depressive tendencies significantly among students.

This shift not only helped improve academic outcomes but also had positive effects on mental health as teens were able to get adequate rest without having to sacrifice extracurricular activities or family duties.

The idea of starting schools later isn't new; however, its implementation has been slow due largely because changing such ingrained societal norms takes time. But if we want our younger kids performing optimally while avoiding unnecessary strain caused by excessive workload or screen time then we need to rethink how we structure our day-to-day lives. Research has demonstrated that inadequate rest can detrimentally affect our health and wellness, so it is essential to ensure we are getting enough sleep by retiring earlier and limiting screen time before bed.

Balancing Academic Responsibilities With Other Duties

As a student, you're expected to juggle academic responsibilities with other duties. Yet, it can be a challenge to effectively manage such a hectic schedule. Homework alone can take up to four hours a day, and that's not counting extracurricular activities or part-time jobs. So, how can you manage your time effectively amidst these multifarious responsibilities?

The key to managing your diverse obligations lies in effective time management strategies . Here are some tips that could help:

- Prioritize tasks: Not all assignments are created equal. Some require more effort and attention than others. Prioritizing your work can help you focus on what's most important first.

- Create a schedule: Having a set routine for studying can make it easier to stick to your commitments and avoid procrastination.

- Leverage technology: There are numerous apps available designed specifically for helping students manage their workload efficiently.

- Avoid multitasking: Multitasking often leads to mistakes and decreased productivity. Rather than attempting to juggle multiple tasks, give your full attention to one task until it is finished before progressing onto the next.

Sleep deprivation among high school students is a serious issue that needs urgent addressing. Multiple studies reveal that the majority of teenagers receive only six to eight hours of sleep per night despite needing more for optimal functioning. This lack of sleep not only affects academic performance but also overall health and wellbeing.

In addition, extracurricular activities and screen time can also affect younger kids' sleep cycle. The American education system has been criticized for promoting this unhealthy trend by assigning excessive amounts of homework without considering individual capacities or needs.

To combat this problem, parents need support from schools in ensuring children go to bed earlier while limiting their exposure to electronic devices during evening hours. This can significantly improve the quality of rest received each night, reducing instances of depressive tendencies associated with inadequate slumber patterns amongst adolescents today.

FAQs in Relation to How Does Homework Affect Students Sleep

Yes, excessive homework can lead to late-night studying, causing students to have inadequate sleep.

Around 56% of students reported losing sleep over schoolwork according to a Stanford study .

Schools may contribute to students' sleep deprivation through early start times and heavy academic loads.

Sleep is crucial for cognitive functions , including memory consolidation which aids in learning; overworking could hinder these processes.

Is Homework Ruining Your Sleep?

Excessive homework can negatively impact students' mental and physical health, leading to stress and lack of sleep.

Teachers can help by coordinating assignment deadlines and exploring alternatives like home-based tasks for younger children.

It's important for educators to recognize the effects of heavy academic loads on student productivity and well-being.

According to a study by the National Sleep Foundation, teenagers need 8-10 hours of sleep per night to function at their best.

Don't let homework rob you of your Z's - prioritize your health and well-being!

Check our wiki for more articles

Sign up to our newsletter and enjoy 10% off one order

Related blog posts

Lack of sleep effects on brain, dementia and sleep, sleeping on the couch, why do i feel sleepy all the tim..., menopause and sleep, how to function after sleepless ..., the best temperature for sleep i..., side effects of sleeping with a ..., why do i roll around in my sleep..., sleep latency, sleep deprivation headache, rhythmic movement disorder, sleep texting : causes and preve..., sleeping with pets: sleep qualit..., military sleep method for better..., improve sleep: the exercise and ..., paradoxical insomnia: causes and..., why you shouldn't always sleep w..., fasting and sleep, sudden tiredness during the day, sms sleep disorder, causes of insomnia in females, ostpartum insomnia, why do men sleep so much, elpenor syndrome, non-24 sleep wake disorder: caus..., daylight savings, how to relax before bed when str..., is it bad to eat before bed, short sleeper syndrome, sleeping with window open, boost sleep and productivity, minimizing screen time before bed, how sleep affects immunity, benefits of yoga for sleep, circadian rhythm fasting, how is sleep quality calculated, obesity and sleep: what is the c..., sleep deprivation and reaction time, sleeping in the dark, insomnia in elderly, do moon phases affect sleep, how to cool a room during summer, nightmare disorder: symptoms and..., fibromyalgia and sleeping too much, can too much exercise cause inso..., improve sleep and athletic perfo..., are we showering the right way f..., at what age do adults start taki..., is insomnia genetic, nightmares in children, the structure of sleeping patterns, how does technology affect sleep, watching tv before sleep: health..., is snoring harmless risks and t..., sleep and memory: a crucial conn..., daytime sleeping: better health,..., diet and sleep, can dogs have sleep apnea, what would happen if we get rid ..., how much sleep do athletes need ..., connection between gaming and sleep, seasonal insomnia, drinks to avoid sleep disruptions, why i sleep better away from home, sleep divorce, sleeping while working from home, exploring the best and worst cit..., sleep inequality, wildfire smoke and sleep, treatment strategies for chronic..., infradian rhythm for optimal wel..., how to not be tired all the time, what causes sleep apnea, 7 night sleep habit builder: gui..., how to improve sleep posture for..., how does social media affect sleep, how much sleep do we lose on tha..., how to achieve good sleep when y..., how working from home has change..., covid insomnia: causes, impacts ..., why do old people wake up so early, how long can you go without sleep, how to beat insomnia and anxiety, can sleep apnea be cured, can you die from lack of sleep, how many spiders do you swallow ..., do power naps work, best sleeping position for breat..., what to do when someone is snori..., how to sleep on a plane, teeth falling out dream, night eating syndrome, why is hyperthyroidism worse at ..., allergies and sleep, coffee naps : boost your energy, insomnia hypnosis, sleep and mental health, how to get more rem sleep, baby sleep cycles, shift work sleep disorder, sleep and epilepsy, the best breathing exercises for..., is dreaming a sign of good sleep, meditation and sleep, benefits of waking up early, how to fall back asleep, doe sleeping make you taller, how to prevent stuffy nose in th..., melatonin and birth control, nose bleeds at night, can lack of sleep cause nausea, 7 effective stretches to do befo..., can you sleep if you have a conc..., disturbed sleep, why do i keep yawning, how to interpret dreams, does turkey make you sleepy, sleep and weight loss, sleeping with socks: health bene..., pregnancy insomnia, sudden excessive sleepiness in e..., is lucid dreaming dangerous, how to hydrate overnight, what causes snoring in females, why you feel sleepy after workout, false awakening: causes and mana..., eating before bed: pros and cons, how long do dreams last, somniphobia: causes and treatments, parasomnia: causes, and treatments, how many calories do you burn sl..., how long does it take to fall as..., what causes snoring in kids, recurring dreams, sleeping upright, precognitive dreams, cold shower before bed, waking up gasping for breath, nightmares during pregnancy, ideal sleeping position during p..., how to wake up in the morning, how to stay awake when tired, fetal position sleep, why do i fart so much in the mor..., gaba for sleep, narcolepsy symptoms, how to wake up early, hypersomnia: causes and symptoms, staying up all night: effects an..., how to become a morning person, why shouldn't you workout before..., melatonin nightmares, what is pink noise, sleeping with eyes open, do blind people dream, cataplexy: symptoms and causes, valerian root for sleep, is sleep apnea genetic, headache from sleeping, micro sleep, binaural beats, foods that help you sleep, why is it so hard to wake up, woke up with blurry vision that ..., why do i moan in my sleep when s..., cbd oil for sleep, what is the 90 minute sleep stra..., what is the ultimate sleep pattern, how to fall asleep fast, master your bedtime routine for ..., how long does it take for the en..., what are the symptoms of low end..., are cannabinoids good for sleep, does cbd make it harder to sleep, does cbd reduce sleep quality, does cbd stop sleep.

- Our Mission

Homework, Sleep, and the Student Brain

At some point, every parent wishes their high school aged student would go to bed earlier as well as find time to pursue their own passions -- or maybe even choose to relax. This thought reemerged as I reread Anna Quindlen's commencement speech, A Short Guide to a Happy Life. The central message of this address, never actually stated, was: "Get a life."

But what prevents students from "getting a life," especially between September and June? One answer is homework.

Favorable Working Conditions

As a history teacher at St. Andrew's Episcopal School and director of the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning , I want to be clear that I both give and support the idea of homework. But homework, whether good or bad, takes time and often cuts into each student's sleep, family dinner, or freedom to follow passions outside of school. For too many students, homework is too often about compliance and "not losing points" rather than about learning.

Most schools have a philosophy about homework that is challenged by each parent's experience doing homework "back in the day." Parents' common misconception is that the teachers and schools giving more homework are more challenging and therefore better teachers and schools. This is a false assumption. The amount of homework your son or daughter does each night should not be a source of pride for the quality of a school. In fact, I would suggest a different metric when evaluating your child's homework. Are you able to stay up with your son or daughter until he or she finishes those assignments? If the answer is no, then too much homework is being assigned, and you both need more of the sleep that, according to Daniel T. Willingham , is crucial to memory consolidation.

I have often joked with my students, while teaching the Progressive Movement and rise of unions between the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, that they should consider striking because of how schools violate child labor laws. If school is each student's "job," then students are working hours usually assigned to Washington, DC lawyers (combing the hours of the school day, school-sponsored activities, and homework). This would certainly be a risky strategy for changing how schools and teachers think about homework, but it certainly would gain attention. (If any of my students are reading this, don't try it!)

So how can we change things?

The Scientific Approach

In the study "What Great Homework Looks Like" from the journal Think Differently and Deeply , which connects research in how the brain learns to the instructional practice of teachers, we see moderate advantages of no more than two hours of homework for high school students. For younger students, the correlation is even smaller. Homework does teach other important, non-cognitive skills such as time management, sustained attention, and rule following, but let us not mask that as learning the content and skills that most assignments are supposed to teach.

Homework can be a powerful learning tool -- if designed and assigned correctly. I say "learning," because good homework should be an independent moment for each student or groups of students through virtual collaboration. It should be challenging and engaging enough to allow for deliberate practice of essential content and skills, but not so hard that parents are asked to recall what they learned in high school. All that usually leads to is family stress.

But even when good homework is assigned, it is the student's approach that is critical. A scientific approach to tackling their homework can actually lead to deepened learning in less time. The biggest contributor to the length of a student's homework is task switching. Too often, students jump between their work on an assignment and the lure of social media. But I have found it hard to convince students of the cost associated with such task switching. Imagine a student writing an essay for AP English class or completing math proofs for their honors geometry class. In the middle of the work, their phone announces a new text message. This is a moment of truth for the student. Should they address that text before or after they finish their assignment?

Delayed Gratification

When a student chooses to check their text, respond and then possibly take an extended dive into social media, they lose a percentage of the learning that has already happened. As a result, when they return to the AP essay or honors geometry proof, they need to retrace their learning in order to catch up to where they were. This jump, between homework and social media, is actually extending the time a student spends on an assignment. My colleagues and I coach our students to see social media as a reward for finishing an assignment. Delaying gratification is an important non-cognitive skill and one that research has shown enhances life outcomes (see the Stanford Marshmallow Test ).

At my school, the goal is to reduce the barriers for each student to meet his or her peak potential without lowering the bar. Good, purposeful homework should be part of any student's learning journey. But it takes teachers to design better homework (which can include no homework at all on some nights), parents to not see hours of homework as a measure of school quality, and students to reflect on their current homework strategies while applying new, research-backed ones. Together, we can all get more sleep -- and that, research shows, is very good for all of our brains and for each student's learning.

- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Teens and healthy sleep habits

Cynthia Weiss

Share this:

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: My 14-year-old daughter goes to bed each night around 10 p.m. Some nights she complains that she cannot fall asleep until hours later. Although she wakes up and says she isn't tired, she does sleep in on weekends. I'm concerned about insomnia, but I’m also worried it’s affecting her ability to concentrate in school. What advice do you have?

ANSWER: Lots of children your daughter's age have trouble falling asleep easily at night. Though one might say your daughter has bouts of insomnia , in many cases, the reason for sleep challenges can be traced back to habits a child has developed that interfere with good sleep. Less often, it may be due to a sleep disorder .

Unfortunately, many teens don’t get the sleep they need. To be well-rested and to help them stay healthy, teenagers need about eight to 10 hours of sleep each night. Healthy sleep is important for many reasons. It can fight stress, improve mood and attitude, and provide energy. When teens are well-rested, they can concentrate, learn, listen and think better than when they’re tired. That can improve school participation and performance. Healthy sleep also contributes to a healthy body, helping it run the way it should.

Sleep challenges plague many teenagers, with about 70% of high school students reporting inadequate sleep on school nights. One of the big reasons is that their body’s internal clock shifts during the teen years. In the preteen years, the hormone melatonin, which signals to the body that it’s time to sleep, is released into the bloodstream earlier in the evening. In most teens, melatonin levels don’t rise until about 10:30 or 11 p.m., so they aren’t sleepy before then. But going to bed at that time means teens should ideally sleep until about 7:30 or 8 a.m. This isn’t an option for many because of school start times.

More than others, some teens tend to show a preference for the late evening hours. They are actually most energetic, intellectually productive and creative in the late evening. It is important to recognize that this is also a normal pattern. For those with these "night owl" tendencies, however, it is especially important to provide lots of light exposure and physical activity immediately upon awakening in the morning and to have dimmer lighting around the house during the evening hours.

One of the most important things teens can do to sleep well regularly is to set a consistent wake-up time and build a sleep schedule around it. It doesn’t have to be exactly the same, but the wake-up time should be within about a two-hour window every day of the week. This allows the body’s internal clock to run smoothly and avoid the difficulty of trying to readjust and get up on Monday morning at 6 a.m. after sleeping in until noon on the weekends.

Picking a reasonable bedtime and sticking to that most days can be very useful, too. When teens get up at the same time every day, they will get sleepy around the same time every night. Your daughter should listen to that and go to bed as soon as she feels tired.

There are also ways your daughter can make it easier for her body to sleep. For example, she should stay away from pop, sugar, caffeine and big meals two to three hours before going to bed. She should exercise, but do it at least two hours before bedtime. And she should not nap during the day.

Creating a sleep-friendly environment can make a difference, too. Electronic devices and screens, along with the lights on them, in a teen’s room at night often disrupt sleep. Avoid distractions by keeping TVs and computers out of bedrooms. Cellphones should be turned off at bedtime and stored outside the bedroom. For the best sleep, keep bedrooms cool, dark and quiet during the night.

Be mindful of how homework, extracurricular activities and after-school jobs can affect the goals you set. Often teens want to do as much as they can, but if the activities are too time-consuming, it may lead to a more significant amount of lost sleep. If your teen has a job, consider limiting it to no more than 15 hours a week with hours that do not interfere with sleep opportunity. Then it’s likely she'll still have enough time for homework and other activities without sacrificing sleep.

Work with your local school district to advocate for later school start times in accordance with the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommendations that school should not start before 8:30 a.m. for middle and high school.

If there are persistent problems falling asleep on a regular basis or if there are concerns for poor sleep quality, it is a good idea to work with a sleep specialist. Encourage your daughter to get more sleep each night. When she does, it’s quite likely that she’ll feel more alert, have more energy and be able to focus more effectively and for longer periods of time at school. — Robin Lloyd, M.D. , Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota

****************************

Related Articles

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Are you getting enough sleep for your best heart health? published 2/20/23

- News Release: Lack of sleep increases unhealthy abdominal fat published 3/28/22

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Why early treatment of esophageal cancer is critical What you need to know about the avian influenza outbreak

Related Articles

- Breathing Disorders

- Hypersomnias

- Movement Disorders

- Circadian Rhythm Disorders

- Parasomnias

- In-Lab Tests

- Home Based/Out of Lab

- Connected Care

- Consumer Sleep Tracking

- Therapy Devices

- Pharmaceuticals

- Surgeries & Procedures

- Behavioral Sleep Medicine

- Demographics

- Sleep & Body Systems

- Prevailing Attitudes

- Laws & Regulations

- Human Resources

- White Papers

Select Page

Early Start Times, Homework Impact Sleep for Teens

Dec 11, 2018 | Age | 0 |

New survey data released from Sleep Cycle, an alarm clock app, reveals how school schedules affect the quality and quantity of sleep for kids and teens.

The survey of more than 1,000 US adults and teens conducted by Propeller Research on behalf of Sleep Cycle in September 2018 found that schoolwork keeps kids and teens up too late, early school start times have them falling asleep in class, and even teens are on board with nap time.

Americans Kids Aren’t Getting Enough Sleep

The majority of parents (70%) agree that their children need a minimum of 8-9 hours of sleep to be well-rested, but nearly half (46%) report that their children get 7 hours or less.

Additionally, while more than three-quarters (77%) of American parents got naps when they were children in kindergarten, 4 in 10 say their child did not.

When they don’t get enough sleep, parents report that their children:

- Are moody — 64%

- Are grumpy and disagreeable — 61%

- Get into more trouble at school — 28%

- Make worse life choices — 20%

- Homework doesn’t help: The vast majority (88%) of teens say they must stay up late to finish school projects — 59% on a weekly or daily basis.

Late to Bed and Early to Rise

School start times also have more than a little to do with it:

- More than half (52%) of American parents and 61% of American teens think school starts too early.

- 55% of teens feel their school work suffers because of the early start time

- 59% say that early school start times inhibit them from being productive later in the day

- 70% feel they would have more productive school days if school started later — 64% of parents agree

- About a quarter of teens (27%) say they begin to feel alert after 9 am, but the majority (39%) don’t start feeling alert until after 10 am.

- Another 10% say they don’t ever feel alert in class.

Are Naps the Answer?

Almost half (46%) of parents feel the school day is also too long. Teens agree:

- 87% have had difficulty staying awake during class because they are tired

- More than two-thirds (69%) have actually fallen asleep

- 56% report feeling worn out at the end of each school day

- All but 3% say they come home tired at least one day a week

- More than three-quarters (76%) of parents feel their child would benefit from a designated nap or rest time at school — teens included. The vast majority (78%) of teens agree that they would benefit from a nap or rest in the course of the school day.

“American students are burning the candle at both ends—staying up late to do homework and waking up early to be back in class. It’s a vicious cycle,” says Carl Johan Hederoth, CEO of Sleep Cycle, in a release. “Parents can help by trying to establish a regular bedtime and by using Sleep Cycle to wake kids in their lightest phase of sleep so they can start each day feeling refreshed, even for those early classes.”

Related Posts

Teen Sleep Habits Impact Brain Development and Overall Health

June 21, 2023

Circadiance Embarks on Crowdfunding Campaign to Launch Pediatric Mask

August 13, 2014

The Snore Shop Targets Troubled Sleepers

June 7, 2015

High-resolution Images Show How the Brain Resets During Sleep

February 3, 2017

Upcoming Events

Prosleep 2024 users conference, you need sleep and so does your practice – st. louis, mo, esthetics: creating beautiful smiles, society of behavioral sleep medicine 6th annual scientific conference, collaboration cures 2024.

School and Sleep

Logan Foley

Editorial Director

Logan is a Certified Sleep Science Coach with a deep understanding of what it means to struggle with sleep. Her years of experience researching and testing sleep products – including mattresses, natural sleep aids, and bedding – are critical to her role helping lead the editorial team. As a chronic insomniac, she aims to bring her findings to anyone struggling with getting adequate rest. Her expertise is in creating informative, trustworthy, and useful health content. When she’s not testing mattresses or researching CBT-I, she enjoys spending time in the sunshine with her husband and her dogs Pepper and Winston.

Want to read more about all our experts in the field?

Getting enough rest is important for all students, from kindergarteners to collegiates. Early wake-up times, daylong course schedules, homework requirements, and extracurricular activities can all interfere with a student’s sleep schedule and leave them feeling tired in class the next day. These demands can increase in high school and college.

The Link Between Sleep and School Performance

Insufficient sleep is particularly problematic for children ages 13 and younger because they require more daily rest than older individuals. Elementary and middle school students typically need to sleep for nine to 11 hours each night, and early start times for schools can leave them with less time to complete their homework and relax in the evening. In recent years, some education experts have suggested starting classes later in the morning to help students feel less tired and more alert, but at many campuses across the country, the school day kicks off at 7 a.m. or earlier.

Many students also struggle with sleep during the transition period between summer vacation and the new school year. Parents can help their children get enough rest by encouraging proper sleep hygiene, which refers to habits and behaviors that promote high-quality sleep. Going to bed and getting up at the same times each day – even on the weekends – can establish a healthy sleep routine, as can “quiet time” in the evenings after their homework is finished. Avoiding caffeine and electronic devices in the hours leading up to bedtime may also be helpful.

About Our Editorial Team

Logan Foley, Editorial Director

Learn how sleep impacts school performance.

A Study Guide To Getting Sleep During Final Exams

Back to School Sleep Tips

How Would Later School Start Times Affect Sleep?

Improve Your Child’s School Performance With a Good Night’s Sleep

Other articles of interest, children, teens & sleep, sleep solutions, bedroom environment, sleep hygiene.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Homework, sleep insufficiency and adolescent neurobehavioral problems: Shanghai Adolescent Cohort

Affiliations.

- 1 Shanghai Key Laboratory of Embryo Original Diseases, The International Peace Maternity & Child Health Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200030, China.

- 2 Institute of Higher Education, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China.

- 3 Shanghai Changning Maternity & Infant Health Institute, Shanghai 200051, China.

- 4 Shanghai Key Laboratory of Embryo Original Diseases, The International Peace Maternity & Child Health Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200030, China; MOE-Shanghai Key Laboratory of Children's Environmental Health, Department of Child and Adolescent Healthcare, Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200092, China.

- 5 The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Zhejiang 310005, China.

- 6 MOE-Shanghai Key Laboratory of Children's Environmental Health, Department of Child and Adolescent Healthcare, Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200092, China.

- 7 Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Department, Shanghai 200070, China.

- 8 Shanghai Key Laboratory of Embryo Original Diseases, The International Peace Maternity & Child Health Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200030, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 37059191

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.04.008

Background: The prospective associations between homework burdens and adolescent neurobehavioral problems, and whether sleep-durations mediated and sex modified such associations remained unclear.

Methods: Using Shanghai-Adolescent-Cohort study, 609 middle-school students were recruited and investigations took place at Grade 6, 7 and 9. Information on homework burdens (defined by homework completion-time and self-perceived homework difficulty), bedtime/wake-up-time and neurobehavioral problems was collected. Two patterns of comprehensive homework burdens ('high' vs. 'low') were identified by latent-class-analysis and two distinct neurobehavioral trajectories ('increased-risk' vs. 'low-risk') were formed by latent-class-mixture-modeling.

Results: Among the 6th-9th graders, the prevalence-rates of sleep-insufficiency and late-bedtime ranged from 44.0 %-55.0 % and 40.3 %-91.6 %, respectively. High homework burdens were concurrently associated with increased-risks of neurobehavioral problems (IRRs: 1.345-1.688, P < 0.05) at each grade, and such associations were mediated by reduced sleep durations (IRRs for indirect-effects: 1.105-1.251, P < 0.05). High homework burden at the 6th-grade (ORs: 2.014-2.168, P < 0.05) or high long-term (grade 6-9) homework burden (ORs: 1.876-1.925, P < 0.05) significantly predicted increased-risk trajectories of anxiety/depression and total-problems, with stronger associations among girls than among boys. The longitudinal associations between long-term homework burdens and increased-risk trajectories of neurobehavioral problems were mediated by reduced sleep-durations (ORs for indirect-effects: 1.189-1.278, P < 0.05), with stronger mediation-effects among girls.

Limitations: This study was restricted to Shanghai adolescents.

Conclusions: High homework burden had both short-term and long-term associations with adolescent neurobehavioral problems, with stronger associations among girls, and sleep-insufficiency may mediate such associations in a sex-specific manner. Approaches targeting appropriate homework-load/difficulty and sleep restoration may help prevent adolescent neurobehavioral problems.

Keywords: Adolescent neurobehavioral problems; Homework burden; Mediation; Modification; Sleep.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

Conflict of interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Similar articles

- [Sleepiness among adolescents: etiology and multiple consequences]. Davidson-Urbain W, Servot S, Godbout R, Montplaisir JY, Touchette E. Davidson-Urbain W, et al. Encephale. 2023 Feb;49(1):87-93. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2022.05.004. Epub 2022 Aug 12. Encephale. 2023. PMID: 35970642 Review. French.

- Bidirectional associations among school bullying, depressive symptoms and sleep problems in adolescents: A cross-lagged longitudinal approach. He Y, Chen SS, Xie GD, Chen LR, Zhang TT, Yuan MY, Li YH, Chang JJ, Su PY. He Y, et al. J Affect Disord. 2022 Feb 1;298(Pt A):590-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.038. Epub 2021 Nov 17. J Affect Disord. 2022. PMID: 34800574

- Associations of time spent on homework or studying with nocturnal sleep behavior and depression symptoms in adolescents from Singapore. Yeo SC, Tan J, Lo JC, Chee MWL, Gooley JJ. Yeo SC, et al. Sleep Health. 2020 Dec;6(6):758-766. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.04.011. Epub 2020 Jun 12. Sleep Health. 2020. PMID: 32536472

- [The use of social media modifies teenagers' sleep-related behavior]. Royant-Parola S, Londe V, Tréhout S, Hartley S. Royant-Parola S, et al. Encephale. 2018 Sep;44(4):321-328. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2017.03.009. Epub 2017 Jun 8. Encephale. 2018. PMID: 28602529 French.

- The relation among sleep duration, homework burden, and sleep hygiene in chinese school-aged children. Sun WQ, Spruyt K, Chen WJ, Jiang YR, Schonfeld D, Adams R, Tseng CH, Shen XM, Jiang F. Sun WQ, et al. Behav Sleep Med. 2014 Sep 3;12(5):398-411. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2013.825837. Epub 2013 Nov 4. Behav Sleep Med. 2014. PMID: 24188543

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

The CavChron

How does homework affect a high school student’s sleep schedule.

Elise Dinbergs

Here at HBHS, this is a typical homework assignment from an AP level class. The amount of homework a student has can have disastrous effects on their health and sleep schedule. “Kids shouldn’t be given more than two hours of homework a day, [preferably] one hour a day outside of school,” said Christina Ellis.

Elise Dinbergs , Co-A&E Editor November 26, 2019

The average high school student struggles to find time in the day to balance their homework and extracurricular activities, which can often have a negative impact on them. For those attempting to find time to fit in all their homework and activities, sleeping may seem like an option instead of a need, but it really is necessary.

In our society today, students are pushed to succeed in various ways, whether it is through standardized testing, such as the PSAT, SAT, or ACT, or are exerted to their limit to get exceptional grades. Maintaining all these academic pressures can be disastrous to a teen’s physical and mental health, according to a study done by Stanford University’s Sleep Disorder Clinic. In fact, sleep deprivation among teens has many negative effects, such as drowsiness, bad grades, anxiety, and an inability to concentrate, just to name a few.

These problems continue to fester in teen’s lives, and oftentimes, kids don’t even realize that they are really tired. They are acclimated to doing homework and other assignments late into the night. Students would benefit if they spent less time on this homework, so that they wouldn’t be staying up too late and would be able to go to sleep at a healthy hour.

“Kids are staying up too late doing homework, and I think it would be better for everyone’s health if they got more sleep,” said Christina Ellis, a history teacher at HBHS. Time management is another skill that kids could use to figure out what they have to do and can do in a day. Waiting until the last minute to do assignments keeps kids awake late each night, which can create an unhealthy cycle of sleep deprivation.

Sleep deprivation is a huge problem across the country. Many students feel pressured to take as many high-level AP classes as they can to ‘succeed’, when in reality, it leaves them bogged down with homework and stress. Going a long period of time without adequate sleep can have negative impacts on a student’s academics , as their brains aren’t working as well as they should be.

The amount of homework students have nightly is based on the level of classes they are taking in school. Balancing sports and homework is not an easy feat, and teachers still assign the same homework, regardless of whether or not a student is extremely occupied that night with activities.

“I believe that 90 minutes of homework would be appropriate,” said Susan Joyce, a guidance counselor at HBHS. “Overloading a student with homework, after they have already sat through a 7 hour school day and extracurriculars, sports or jobs, and can exhaust them by the time they get home, so the student is too tired to complete any of their assignments.”

Sometimes, sleep deprivation due to homework is not at the fault of the student. Many teachers believe that they should assign a large amount of homework so that their students can succeed in class. When students are taking 6 or 7 classes with that kind of mentality, they can be overwhelmed.

“There’s certain classes that assign way too much homework and it’s overdoing it. I think most teachers’ mentality is more is more,” said Vero Leblanc ‘20. The pressure for a student to succeed is so elevated that it comes at the cost of that student’s health and wellbeing. Teachers at HBHS should work to plan their homework schedules accordingly, so that the students aren’t overwhelmed and can maintain a healthy sleep schedule.That way, they can be healthy and are able to perform better in class.

Elise Dinbergs ‘20 is joining the CavChron staff as a first-year A&E editor. She is really enthusiastic to fulfill this role, as she is heavily involved...

![does homework affect sleep schedule Steven Crooks grades a lab from his AP Physics 1 class. He is a new teacher, but already helping his students succeed with his grading philosophies and policies. “I want to see the thought process [in their work],” said Crooks.](https://cavchronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Grading-Philosophies-300x225.jpg)

Grading Philosophies

Are Midterms and Finals Important for High Schoolers?

I Will Follow You into the Dark: Just as Poignant 8 Years Later

2023: The Year the Movies Made a Comeback

Maggie Rogers Reflects on ‘Don’t Forget Me’

A Love for the Stage Changes Future Career Plans

Playing a Sport Six Years Later: Kate Berrigan Finds a Community

Last One, Best One: The Cheer Team Begins One of Their Best Seasons Yet

Bonjour Belgium: Gina Anton Studies Abroad Her Senior Year

2023: The Year of Swifties

Q&A with HBHS’s Nurses

Green Group: Growing Plants and Local Awareness

Sitting Down with Sal: A Q&A with Mrs. Salamone

HBHS’s New Faculty Members

HB’s Red Cross Club

The student news site of Hollis Brookline High School

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Mattress Education Mattress Sizes Mattress Types Choosing the Best Mattress Replacing a Mattress Caring for a Mattress Mattress Disposal Mattress Accessories Adjustable Beds Mattress Sizes Mattress Types Choosing the Best Mattress Replacing a Mattress Caring for a Mattress Mattress Disposal Mattress Accessories Adjustable Beds

- Better Sleep Sleep Positions Better Sleep Guide How to Sleep Better Tips for Surviving Daylight Saving Time The Ideal Bedroom Survey: Relationships & Sleep Children & Sleep Sleep Myths

- Resources Blog Research Press Releases

- Extras The Science of Sleep Stages of Sleep Sleep Disorders Sleep Safety Consequences of Poor Sleep Bedroom Evolution History of the Mattress

- August 12, 2023

Managing Homework and Bedtime Routine: Striking a Balance for School-Aged Children

Managing homework and bedtime routines: striking a balance for school-aged children.

As the school year gets underway, balancing children’s homework and bedtime routine can feel like a tightrope walk for parents. And the struggle is real—on one hand, it’s important for children to get enough sleep to support their cognitive development, memory consolidation, and learning. On the other hand, there’s a lot of homework to be done!

We’re here to guide you through the challenges of balancing homework and bedtime, so your young scholars can thrive in the classroom and under the covers.

The Importance of Sleep for School-Aged Children

Remember when naptime felt like a punishment? Turns out, sleep is the superhero of cognitive development . While our kids snooze, their brains are busy building memory bridges and sharpening their problem-solving skills. Adequate, quality sleep is the secret ingredient to their attention span, emotional resilience, and yes, even those pop quizzes.

Understanding the Challenges of Homework and Sleep

There are several challenges that can make it difficult for children to get enough sleep . First, there’s the nightly battle of sitting down to tackle homework. And then, the dreaded dilemma of: stay up to finish this assignment or prioritize sleep and go to bed? It’s a conundrum every parent faces.

Too Much Homework

Many school-aged children come home with a stack of homework that feels like more than they can complete in one night, which commonly leads to late nights and possibly sleep deprivation.

Screen Time

From TVs to smartphones, computers to tablets, many children spend hours each day using electronic devices. This screen time can stimulate the brain, interfering with their sleep and making it difficult for them to fall asleep.

Kids can experience stressors from a number of sources, including academic pressure, social demands, and even family problems at home. This stress can make it difficult not only to focus on homework but also to fall asleep and stay asleep.

Crafting a Homework Schedule that Respects Sleep Needs

Picture this: a homework schedule that respects both learning and essential snooze time. Dreamy, right? Here are a few things that parents can do to help your children create a homework management schedule that respects their sleep needs:

- Set limits on homework hours. The National Sleep Foundation recommends that children ages 9-13 should ideally get 9-11 hours of sleep per night, but sometimes it can feel like their homework workload can eat into those precious sleep hours. That’s why healthy time management habits are essential. Teaching your child how to prioritize tasks and set achievable goals can significantly impact the number of hours they spend on homework each night. Ultimately, helping them manage their workload effectively not only supports their learning journey but also ensures they have ample time for the quality sleep they need.

- Prioritize tasks. Help your child to prioritize their homework tasks so that they can focus on the most important assignments first and prevent feeling overwhelmed or stressed.

- Take breaks. Encourage your child to take breaks every 20-30 minutes while they’re working on homework. Regular breaks will help them stay focused and avoid getting burned out.

- Set a bedtime schedule and stick to it. Even on weekends, it’s important to stick to a regular bedtime schedule to regulate your child’s body clock and make it easier for them to fall asleep and stay asleep at night.

- Set a “no screen” rule for one hour before bed. The blue light emitted from screens can interfere with the production of melatonin, a hormone that helps to regulate sleep. Limiting screen time before bed will give your child’s eyes a break from the blue light emitted from screens and help them to wind down after a long day. If your child needs to use a screen before bed, finishing up homework or reading on a tablet, make sure their devices are scheduled to regularly shift into “night mode” a couple hours before bedtime.

Establishing a Consistent Bedtime Routine

A consistent bedtime routine isn’t just a calming ritual; it’s a sleep-inducing magic spell. Winding down with calming activities helps encourage sleep. Here are some healthy sleep habits to add to a nightly routine for a seamless transition to dreamland:

- Reading. Not only can reading help improve your child’s literacy skills, but it is also a great way for them to relax and unwind before bed.

- Taking a bath. A warm bath can help to soothe the body and mind, making it easier to fall asleep.

- Listening to calming music. Create a relaxing atmosphere and promote sleep with some quiet, calming music.

- Stretching. Gentle stretching can help relax the body and mind, making it easier to fall asleep.

- Meditation. Similar to stretching, meditation can help calm the mind and body and promote relaxation before bed.

Collaborative Communication Between Parents and Children

Striking a balance between homework and bedtime can feel like a science experiment—tinkering to figure out the right ratio between enforcing the rules and going with the flow or prioritizing wellness and completing tasks. But the truth is, there is no magical equation or one-size-fits-all solution to strike the right balance between homework management and bedtime.

In fact, a 2018 Better Sleep Council study found that homework-related stress is a significant concern for high school students, with more than three-fourths (75%) citing it as a source of stress. The study also found that students spending excessive time on homework (39% spending 3+ hours) may experience increased stress without proportional academic benefits, further underscoring the need for a more thoughtful approach to homework and its impact on sleep.

One way to help find the right balance for your kids? Keeping a line of open communication. Talk to your kids about their schoolwork and sleep needs . Our advice?

- Get their insight. Ask them about how much homework they have each night and how long they think it might take them to finish.

- Organize their workload. Get a homework planner to help them to prioritize their tasks and set achievable goals.

- Encourage participation. Involve them in crafting their routines, empowering them to take charge of their education and sleep.

- Work together. If they’re feeling overwhelmed or stressed, work together to find solutions.

This isn’t just about bedtime routine; it’s about fostering responsibility and finding balance.

Explore more sleep-related resources, tips, and research at bettersleep.org .

Related Posts

Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques for Reducing Insomnia and Enhancing Sleep Quality

10 Effective Tips to Improve Your Sleep Hygiene for a Restful Night

Summer Sleep Tips: Creating a Relaxing Summer Sleep Sanctuary

ABOUT THE BETTER SLEEP COUNCIL

- Mattress Education

- Better Sleep

- Privacy Policy

- Confidentiality Statement

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Put this information right at your fingertips with my book, It’s Never Too Late To Sleep Train

Craig Canapari, MD

Proven advice for better sleep in kids and parents

Homework vs. Sleep: A Cause of Stress in Teens (And Younger Kids)

Posted on August 31, 2015 by Craig Canapari M.D.

Homework stresses kids out; there is no way around this fact. The combination of heavy homework loads and early school start times is a major cause of sleep deprivation and consequent stress in teens, but this can be a problem even in younger kids.

When we moved to Connecticut, I was struck by the perception of some parents that my son’s classmates that he and his peers were not getting enough homework. I was shocked; these kids were in first grade at the time. Fortunately, my son’s teacher have resisted this pressure.

When I started looking into the evidence, I was surprised to find that there is not much evidence that homework before high school benefits children. I really love this article by Justin Coulson, a parenting expert and psychologist, detailing why he bans his school age children from doing homework , concluding from the evidence that homework does more harm than good. A recent study showed that some elementary school children had three times the recommended homework load . In spite of this, homework has started appearing even in kindergarten and the first great in spite of recommendations to the contrary. This has become a source of great stress to families.

Sleep deprivation in teenagers is an epidemic here in the US, with up to 90% of teenagers not getting enough sleep on school nights . The most important factor causing this is school start times that are too early for teenagers, who are hardwired to go to bed later and get up later compared with younger children (or grown-ups, for that matter). I’ve discussed this at length on my blog .

Another factor which can cause sleep deprivation is homework. Some studies suggest that the amount of homework which teenagers receive has stayed constant over time. I don’t pretend to be an educational expert, but I frequently see children and teenagers who have hours and hours of homework every night. This seems most common in teenagers who are striving to get into competitive colleges. This is piled on top of multiple extracurricular activities– sports, clubs, music lessons, and public service. Of course, the patients and families I see in clinic tend to be the people with the greatest difficulties with sleep. So I decided to look into this issue a bit more.

How common is excessive homework, anyway?

The recommendation of the National Education Association is that children received no more than ten minutes of homework per grade level. So a high school senior would max out at two hours of homework per night. An analysis published by the Brookings Institute concluded that there has been little change in the amount of homework assigned between 1984 and 2012 . About 15% of juniors and seniors did have greater than two hours of homework per night. Interestingly, the author also referenced a study which showed that about 15% of parents were concerned about excessive homework as well. This would suggest that the problem of excessive homework is occurring only in about one in six teenagers.

There is a perception that homework loads are excessive. This certainly may be the case in some communities or in high pressure schools. Teenagers certainly think that they have too much homework; here is a well researched piece written by a teenager who questions the utility of large amounts of homework.

Some generalities emerge from the educational research :

- Older students get more homework than younger students

- Race may play a role, with Asian students doing more homework

- Less experienced teachers assign more homework

- Math classes are the classes most likely to assign homework

How beneficial is homework?

The US is a relatively homework intense country, but does not score as well as countries where homework is less common. In high school age kids, homework does have benefits. However, 70 minutes total seems to be the sweet spot in terms of benefits ; homework in excess of this amount is associated with decreasing test scores.