- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Sage (bulimia nervosa)

Case study details.

Sage is a 26-year-old doctoral candidate in English literature at the local university. She is in good standing in her program and has plans to enter the job market in the fall. In your intake, she tells you she thinks she is “fat” and has been self-conscious about her body since the sixth grade, at which time she began menstruating and developing breasts earlier than the other girls in her class. She was teased for needing a bra and remembers feeling “chubby, too big, and just wanting to be small like [her] younger sister.” She started dieting in the seventh grade, following strict rules for weeks (e.g., she recalls the grapefruit only diet), then transitioning into what she called “bad” weeks. During these times, she would stock up on candy bars and other snack foods and eat them, often in her bedroom late at night. Her parents became concerned and tried to strictly limit her dieting. This led to eating “normal” during the day and binging on those candy bars she kept hidden in her bedroom at night if she felt sad, scared, or mad. She grew into a habit of eating to feel better – relief that was only temporary, as she would feel ashamed about what she had done and resolve to not do it again. In college, her pattern of emotional eating continued, which felt more distressing to her because of the pressure to look “as pretty and thin as the other girls.” In spring of her freshman year she experimented with throwing up after the late-night eating and found that, at least in the minutes that followed, she felt like she had much more control and believed this would help her to prevent the weight gain she so dreaded. She fell into a vicious cycle of late-night binges (typically consuming about 7 candy bars in 15 minutes, during which times Sage described feeling very out of control) followed by making herself throw up. In college, she engaged in these binge-purge episodes about 6 nights/week. At present, she is having a harder time hiding the episodes because she lives with her boyfriend; she estimates that they occur about 4 nights per week. The times when she feels the most compelled to binge and purge are when she has a major presentation coming up in her doctoral program and when she gets in a fight with her boyfriend. Her BMI is in the normal range, but she says she needs to lose weight. She wants to stop binging and purging because she does not want her boyfriend to find out, but she is also afraid that if she stops, she will gain weight.

- Binges and Purging

- Emotion Dysregulation

- Disordered Eating

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. bulimia nervosa.

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

CASE REPORT article

Case report: unexpected remission from extreme and enduring bulimia nervosa with repeated ketamine assisted psychotherapy.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 2 Behavioral Science Department, Utah Valley University, Orem, UT, United States

- 3 Division of Public Health, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 4 Marriage and Family Therapy Program, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 5 Riverwoods Behavioral Health, Provo, UT, United States

- 6 Department of Educational Psychology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

Background: Bulimia nervosa is a disabling psychiatric disorder that considerably impairs physical health, disrupts psychosocial functioning, and reduces overall quality of life. Despite available treatment, less than half of sufferers achieve recovery and approximately a third become chronically ill. Extreme and enduring cases are particularly resistant to first-line treatment, namely antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapy, and have the highest rate of premature mortality. Here, we demonstrate that in such cases, repeated sessions of ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP) is an effective treatment alternative for improving symptoms.

Case Presentation: A 21-year-old woman presented with extreme and enduring bulimia nervosa. She reported recurrent binge-eating and purging by self-induced vomiting 40 episodes per day, which proved refractory to both pharmacological and behavioral treatment at the outpatient, residential, and inpatient level. Provided this, her physician recommended repeated KAP as an exploratory and off-label intervention for her eating disorder. The patient underwent three courses of KAP over 3 months, with each course consisting of six sessions scheduled twice weekly. She showed dramatic reductions in binge-eating and purging following the first course of treatment that continued with the second and third. Complete cessation of behavioral symptoms was achieved 3 months post-treatment. Her remission has sustained for over 1 year to date.

Conclusions: To our knowledge, this is the first report of repeated KAP used to treat bulimia nervosa that led to complete and sustained remission, a rare outcome for severe and enduring cases, let alone extreme ones. Additionally, it highlights the degree to which KAP can be tailored at the individual level based on symptom severity and treatment response. While its mechanism of action is unclear, repeated KAP is a promising intervention for bulimia nervosa that warrants future research and clinical practice consideration.

Introduction

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is a disabling psychiatric disorder characterized by recurrent binge-eating (consuming objectively large amounts of food with a sense of lost control) and inappropriate compensatory behaviors (self-induced vomiting; laxative, diuretic, or medication misuse; and fasting or excessive exercise) aimed at preventing weight gain ( 1 , 2 ). Overtime, the severity of these patterns significantly disrupts physical health and psychosocial functioning, as well as impacts families and communities at large ( 3 ). Approximately 50 million people worldwide will develop BN at some point in their life ( 4 ). Moreover, studies have found BN to be associated with concomitant psychiatric comorbidity [e.g., mood disorders and substance abuse; ( 5 , 6 )] in addition to premature mortality due to medical complications ( 7 – 9 ). Death by suicide is also eight times more likely to occur among individuals with BN compared to the general population, with more than a third experiencing lifetime rates of non-suicidal self-injury ( 10 , 11 ).

While pharmacological (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and behavioral (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) interventions are effective in managing BN ( 12 , 13 ), many individuals do not respond to first-line treatment, are unsuccessful in later attempts, and fail to change over protracted periods ( 14 , 15 ). Nearly 30% of sufferers become chronically ill as a result ( 16 ). For such chronic refractory cases, the paucity of evidence-based treatments has prompted paradigm shifts toward harm reduction and palliative care over recovery ( 17 , 18 ).

Ketamine, a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAr) antagonist, is an emerging therapy for treatment-resistant mood disorders ( 19 , 20 ). Single-dose studies have consistently shown rapid antidepressant and anti-suicidal effects following ketamine treatment, though are relatively short-lived (1–4 weeks) ( 21 – 28 ). Ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP) has therefore been utilized to prolong ketamine's efficacy and maximize therapeutic outcomes ( 29 – 34 ). To date, few studies have used ketamine for the treatment of eating disorders, including one open-label study ( 35 ), two case reports ( 36 , 37 ), and one longitudinal case series ( 38 ), all of which administered ketamine without a psychotherapeutic component. Nonetheless, the results are encouraging. Here, we report the case of a young woman suffering from extreme and enduring BN, according to CARE (CAse REport) guidelines ( 39 ), who demonstrated remarkable symptom improvement following repeated sessions of KAP.

Case Presentation

A 21-year-old woman with BN of 9 years presented to the outpatient clinic, Forum Health. She was first diagnosed with BN, binge-eating/purging type, at 12.5 years of age to which the severity of her symptoms steadily increased overtime. On presentation, she reported alarming rates of binge-eating and purging by self-induced vomiting, averaging ~40 episodes per day for the last 12 months. Based on this frequency, her BN was categorized as “extreme” according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criterion (14 or more episodes per week). Clinical assessment and scoring on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire [EDE-Q; ( 40 , 41 )] additionally confirmed the severity of her illness. No laxative or diuretic abuse was reported. While not active in psychiatric treatment, the patient was taking potassium chloride 20 mEq extended-release twice daily for hypokalemia as well as trazodone 100 mg once daily in the evenings for sleep. At 161.92 cm tall and 46.26 kg in weight [body mass index (BMI) = 17.6 kg per m 2 ], the patient was amenorrheic and described body image disturbances, intense fear of gaining weight, and obsessive-compulsive tendencies around food (counting calories, binging by order of food group, and inability to discard uneaten items). She further displayed pronounced bilateral parotid sialadenosis (enlargement of the salivary glands) and pseudo-idiopathic edema, otherwise known as pseudo-bartter's syndrome (PBS): a rare and painful complication of BN characterized by hyperaldosteronism, metabolic alkalosis, and hypokalemia ( 42 ). As a University student studying cognitive neuroscience, the patient was obliged to take a medical leave due functional decline. “I lost all ability to take care of myself. I could not think clearly or show up for classes. I stopped socializing and running errands. I could hardly maintain basic hygiene.”

Her psychiatric history included an adolescent sexual assault by a treating physician (13 years of age [2011]); a suicide attempt by cut throat injury at the level of the hyoid bone, which required emergency transportation and thyroid cartilage repair as well as inpatient hospitalization (13 years of age [2011]); a second suicide attempt by drug overdose involving mixed opioids, barbiturates, and antidepressants that resulted in emergency room hospitalization (15 years of age [2013]); and a blitz rape (surprise attack) by an unknown assailant (19 years of age [2017]). The patient's history also contained reports of major depression, general anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. There was no family history of eating disorders, including BN.

As an outpatient, she was treated with various pharmacotherapies (fluoxetine 40 mg once daily, citalopram 20 mg once daily, and naltrexone 50 mg twice daily), behavioral interventions (cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing), and nutritional counseling (dietary modification and time-based feeding). She additionally was prescribed spironolactone 25 mg twice daily, a potassium-sparing diuretic, on multiple occasions to treat PBS following attempts at purging cessation. However, the patient's binge-purge patterns continued. Finally, she received inpatient, residential, and intensive-outpatient eating disorder care (15–16 years of age [2013–2014]), which the patient described as a “traumatic experience” that resulted in immediate relapse upon discharge.

“My parents pulled me out of class and dropped me off at a center, leaving me there for almost 10 months. It was like being in prison. I was completely cut off from my friends and family. I was forced to eat unreasonable amounts of food at each meal. And I learned new [eating disorder] tricks from other patients that I tried later on. It was not a place conducive to recovery, at least for me. It just made my condition worse.”

Her medical history detailed emergency room hospitalizations for hypokalemia (16, 19, and 20 years of age [2014, 2017, 2018]), gastroesophageal reflux disorder (17–21 years of age [2015–2019]), gastric and duodenal ulcers (19 and 21 years of age [2017, 2019]), hypothyroidism (20–21 years of age [2018–2019]), and adrenocortical insufficiency (20–21 years of age [2018–2019]). Porcelain-laminate veneers were also placed on 10 of her teeth due to dental caries and enamel erosion from chronic purging (21 years of age [2019]).

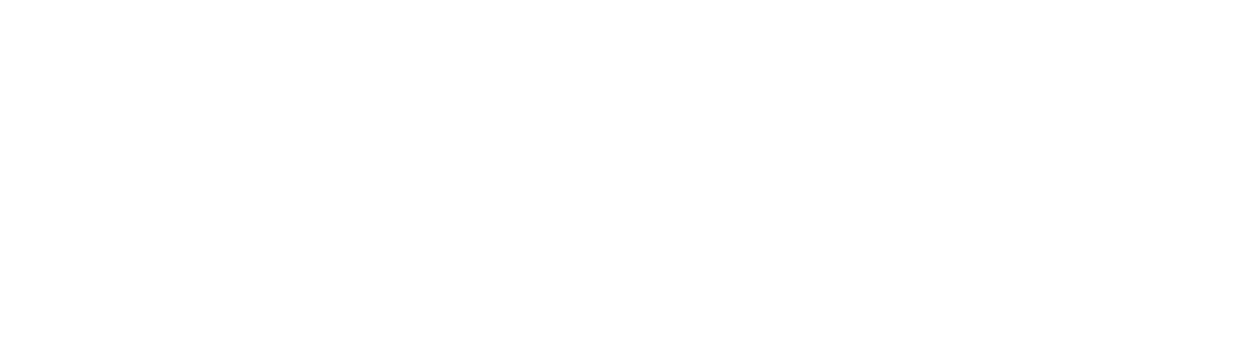

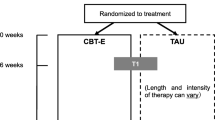

Given the patient's extreme and chronic refractory state, her physician recommended repeated KAP, with the understanding it constituted an exploratory and off-label intervention for her eating disorder. She consented to treatment following a comprehensive medical evaluation and in-depth review of the procedures, risks, and possible side effects. A signed consent form was obtained. Prior to treatment, she met with a clinical psychologist to establish rapport and therapeutic alliance. The patient then underwent one course of repeated KAP, consisting of six sessions scheduled twice weekly for 3 weeks, with a minimum interval between sessions of 48 h ( Figure 1 ). Each KAP session involved guided psychotherapy combined with racemic ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mg per kg bodyweight suspended in 0.9% normal saline) administered intravenously over 40 min. The drug regimen was standard practice in the clinic for sub-anesthetic ketamine infusions, which is most commonly used for treating psychiatric disorders and is supported by a substantial body of literature ( 43 , 44 ). A person-centered, humanistic approach to psychotherapy was employed to facilitate the process of self-actualization and therapeutic change. KAP sessions were preceded by 30 min of preparatory psychotherapy and delivered in a private room with dimmed lights, ambient music, and textile art on the ceiling. The intervention components and ketamine regimen remained the same for all five consecutive sessions; and blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation were continuously monitored. Due to the severity of her eating disorder, however, the patient returned to the clinic 1 month later for a second course of repeated KAP and then again 1 month later for a third.

Figure 1 . Timeline of clinical events. The patient received three courses of repeated KAP for extreme and enduring BN, consisting of six sessions per course scheduled twice weekly for 3 weeks. KAP, ketamine assisted psychotherapy; BN, bulimia nervosa; B/P, binge-eating and purging.

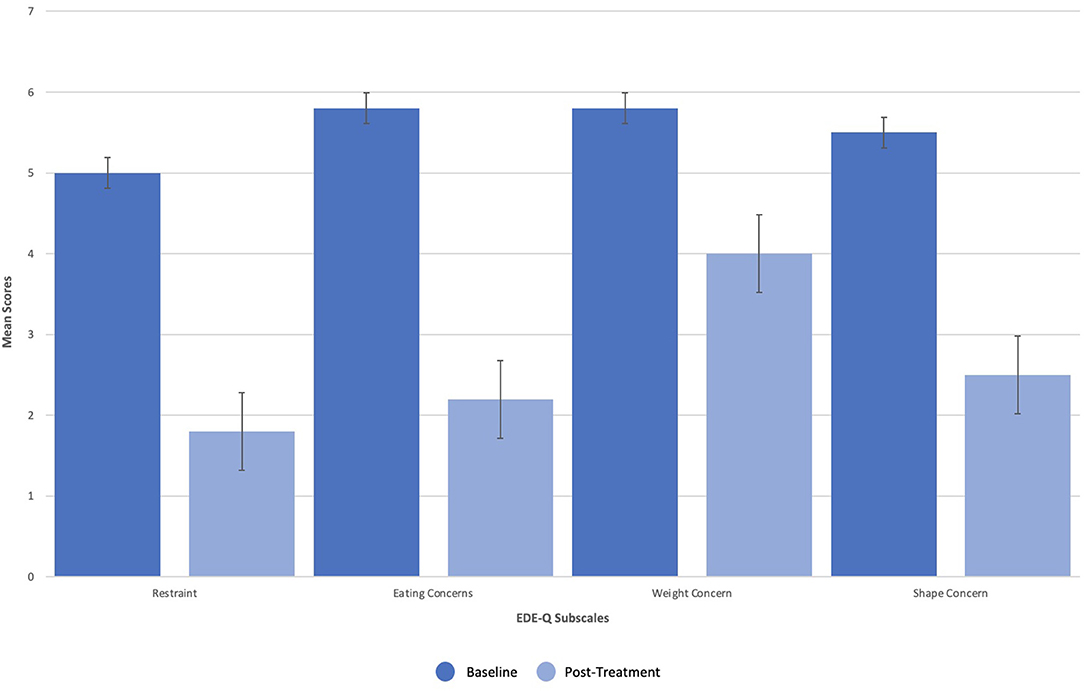

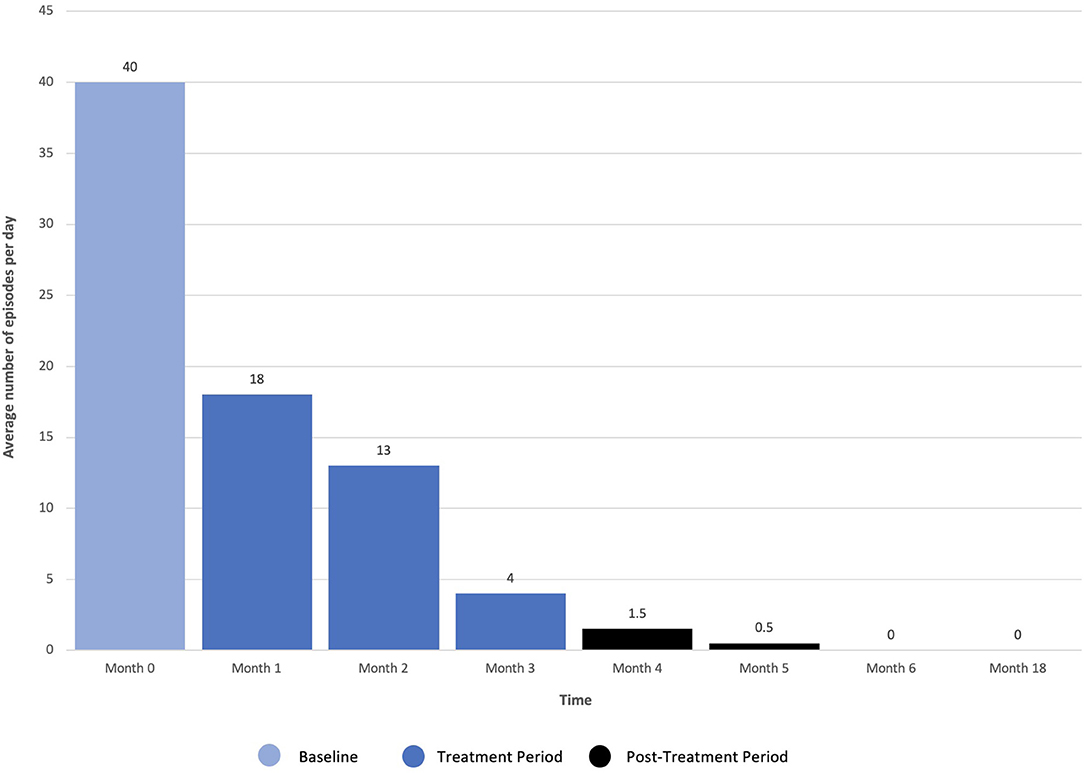

Dissociation, ego dissolution, and perceptual distortions were present during all KAP sessions, as evidenced by the patient's description of “being disconnected from reality,” “losing [her] sense of identity and self,” and “seeing abstract geometric patterns.” She further exhibited mild diplopia (double vision), nystagmus (involuntary oscillations of the eyes), and alogia (lack of speech) during treatment that resolved completely. No other side effects or adverse events were reported. The patient's eating disorder symptoms remitted over the course of treatments, as measured by change in scoring on the EDE-Q as well as entries from a daily tracking log that recorded frequency of binge-eating and purging. On the EDE-Q, her global score dropped from 31.8 at baseline to 15.0 by the end of all three courses (18 sessions), with similar patterns recorded across all four subscales: “Restraint” ( M = 5.0, SD = 2.2 to M = 1.8, SD = 1.3), “Eating Concern” ( M = 5.8, SD = 0.5 to M = 2.2, SD = 1.5), “Weight Concern” ( M = 5.8, SD = 0.5 to M = 4.0, SD = 1.9), and “Shape Concern” ( M = 5.5, SD = 0.8 to M = 2.5, SD = 1.6) ( Figure 2 ). Additionally, the patient's tracking log showed decreases in binge-eating and purging from 40 to 18 episodes per day after the first course of treatment (6 sessions), 18 to 13 episodes per day after the second course of treatment (12 sessions), and 13 to 4 episodes per day after the third course of treatment (18 sessions) ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 2 . Change in scoring on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q).

Figure 3 . Frequency of daily binge-eating and purging following repeated ketamine assisted psychotherapy.

Most notably, the patient stopped her binge-eating and purging behaviors 3 months post-treatment. Given her initial severity and chronic refractory state, this degree of improvement was striking. The patient's daily tracking log additionally showed no signs of relapse 1 year later, accompanied by marked improvement in psychosocial functioning. Specifically, she reported feeling “free” from intrusive BN thoughts and compulsions, “less impulsive” when faced with the urge to binge and purge, and “more confident” about her body in general. The patient has since resumed her academic studies in preparation for a doctoral program.

Severe, chronic, and refractory eating disorder symptoms are unfortunately common among patients with BN. In this case, we describe a young woman with extreme and enduring BN, who remained unresponsive to first-line treatment for nearly a decade, despite care at the outpatient, residential, and inpatient level. Her eating disorder was extreme, insofar as she engaged in recurrent binge-eating and purging by self-induced vomiting 40 episodes per day, which significantly exceeds DSM-5 criterion (14 or more episodes per week). Given the severity of her illness, complete and sustained remission with three courses of repeated KAP (18 sessions) was both remarkable and unanticipated. These findings are more robust provided the patient was not active in psychiatric treatment for 1 year prior to clinic admission, excluding her long-standing prescription of potassium chloride for hypokalemia and trazodone for sleep. If ketamine and psychotherapy act synergistically, with therapy priming and enhancing the response to treatment, then its combined effect may explain the striking improvements in symptoms. Serial treatments likely account for the durability of response necessary for sustained remission, which is consistent with literature ( 45 – 48 ).

Provided this is the first report of repeated KAP used as an exploratory and off-label intervention for BN, it is important to consider the a-priori context. Clinical recommendation to pursue repeated KAP was prompted by three factors. First, the patient's psychiatric and medical history that detailed unsuccessful treatment attempts, including pharmacotherapies, behavioral treatments, and nutritional counseling—even at higher levels of eating disorder care; and significant trauma to which accumulating evidence has shown ketamine to yield positive effects for ( 49 – 51 ). Second, her severe functional impairment in three major life domains, including academic work, social and family engagement, and personal responsibilities. The patient was binge-eating and purging nearly to the exclusion of all other activities, spending more time “alone in the bathroom than with [her] friends or family.” Finally, an open-label case series on repeated ketamine in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa, showing modest improvements in eating disorder symptoms ( 38 ).

The patient's impetus for treatment was largely driven by fear of premature mortality—that if she did not attempt something new, she was going to “eat [herself] to death,” quite literally. Serious degradation in the patient's physical and mental health status were particularly motivating. Apart from transient psychological (dissociation, ego dissolution, and perceptual distortions) and physiological (mild diplopia, nystagmus, and alogia) side effects of ketamine that resolved completely after each session, the treatment was well-tolerated. Following all three courses of treatment, the patient dramatically reduced her binge-eating and purging behaviors by 90% compared to baseline, as measured by the EDE-Q and daily tracking logs. She also demonstrated considerable improvements in disordered eating psychopathology that were captured by the subscales of the EDE-Q, most notably “Restraint” (e.g., dietary rules and avoidance of food) and “Eating Concerns” (e.g., preoccupation with calories and fear of losing control over eating). Moreover, the patient regained control of her impulsive eating as well as resolved her obsessive-compulsive neurosis, which align with previous BN-specific findings from a study on intermittent ketamine infusions in eating disorders ( 35 ). At 3 months follow-up, she achieved complete cessation of binge-eating and purging and no longer met diagnostic criteria for BN. The magnitude of response neither diminished over time, with no signs of relapse at 15 months follow-up, contrary to studies showing rapid decline of effects after treatment ( 28 , 52 , 53 ). With sustained remission, the patient has adopted a healthier relationship with food, established psychosocial stability in her life, and resumed her academic studies in preparation for graduate school.

This is a single case report with inherent limitations in generalizing the findings to other patients with BN. The lack of polypharmacy or medication washout is an additional limitation that may have unknowingly mediated improvements. Furthermore, it is unclear as to whether ketamine or psychotherapy produced greater clinical benefit, if both are coadjuvant and necessary, or if the treatment would have been as effective without psychotherapy and/or fewer sessions. Finally, a person-centered, humanistic approach to psychotherapy was employed, differing from more traditional methods, such as cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal, and psychodynamic therapy. Open pilot studies as well as fully-powered randomized controlled trials with longitudinal assessment are thus required to establish whether the outcome of this case can be replicated, to what degree ketamine and psychotherapy contribute to the overall success of the treatment, and the comparative efficacy of different psychotherapeutic interventions. Further research is also warranted to optimize KAP duration and frequency for this patient population.

Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that repeated KAP is an effective treatment for extreme and enduring BN, which is exceedingly resistant to first-line therapies and associated with poor prognosis. It further highlights the utility of combined strategies that may prolong ketamine's efficacy, and subsequently maximize therapeutic outcomes at the individual level.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

PH-B assessed, treated, and followed-up with the patient. AR interviewed the patient, conceptualized the case report, drafted the manuscript, and developed all figures. LKJ and SC contributed to the literature review and assisted with manuscript preparation. LG, QT, and MR provided substantial contributions to the interpretation of data as well as manuscript revisions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew Petersen, the lead physician on this case, for his contributions to this study and continued innovation in the field.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; BN, bulimia nervosa; DSM-5, diagnostics and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition; EDE-Q, eating disorder examination questionnaire; KAP, ketamine assisted psychotherapy; NMDAr, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; PBS, pseudo-bartter's syndrome.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 . 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Grilo CM, Ivezaj V, White MA. Evaluation of the DSM-5 severity indicator for bulimia nervosa. Behav Res Ther. (2015) 67:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.002

3. van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2020) 33:521–7. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000641

4. Qian J, Wu Y, Liu F, Zhu Y, Jin H, Zhang H, et al. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. (2021) 1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01162-z

5. Himmerich H, Hotopf M, Shetty H, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Hayes RD, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity as a risk factor for the mortality of people with bulimia nervosa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2019) 54:813–21. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01667-0

6. Dalle Grave R, Sartirana M, Calugi S. Complex Cases and Comorbidity in Eating Disorders: Assessment and Management . Springer Nature (2021). p. 79–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-69341-1

7. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2011) 68:724–31. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74

8. Huas C, Godart N, Caille A, Pham-Scottez A, Foulon C, Divac SM, et al. Mortality and its predictors in severe bulimia nervosa patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2013) 21:15–9. doi: 10.1002/erv.2178

9. Franko DL, Tabri N, Keshaviah A, Murray HB, Herzog DB, Thomas JJ, et al. Predictors of long-term recovery in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: data from a 22-year longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 96:183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.008

10. Preti A, Rocchi MB, Sisti D, Camboni MV, Miotto P. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the risk of suicide in eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. (2011) 124:6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01641.x

11. Cucchi A, Ryan D, Konstantakopoulos G, Stroumpa S, Kaçar AS, Renshaw S, et al. Lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. (2016) 46:1345–58. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000027

12. Mitchell JE, Agras S, Wonderlich S. Treatment of bulimia nervosa: where are we and where are we going? Int J Eat Disord. (2007) 40:95–101. doi: 10.1002/eat.20343

13. Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, Rustenbach SJ, Kersting A, Herpertz S. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. (2010) 43:205–17. doi: 10.1002/eat.20696

14. Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Myers TC, Kadlec K, LaHaise K, et al. Minimizing and treating chronicity in the eating disorders: a clinical overview. Int J Eat Disord. (2012) 45:467–75. doi: 10.1002/eat.20978

15. Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, Murray HB, Keshaviah A, Hastings E, et al. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. (2017) 78:184–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10393

16. Steinhausen HC, Weber S. The outcome of bulimia nervosa: findings from one-quarter century of research. Am J Psychiatry. (2009) 166:1331–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040582

17. Westmoreland P, Mehler PS. Caring for patients with severe and enduring eating disorders (SEED): certification, harm reduction, palliative care, and the question of futility. J Psychiatr Pract. (2016) 22:313–20. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000160

18. Strand M, Sjöstrand M, Lindblad A. A palliative care approach in psychiatry: clinical implications. BMC Med Ethics. (2020) 21:29. doi: 10.1186/s12910-020-00472-8

19. Park LT, Falodun TB, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine for treatment-resistant mood disorders. Focus. (2019) 17:8–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20180030

20. Wilkinson ST, Sanacora G. A new generation of antidepressants: an update on the pharmaceutical pipeline for novel and rapid-acting therapeutics in mood disorders based on glutamate/GABA neurotransmitter systems. Drug Discov Today. (2019) 24:606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.11.007

21. Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. (2000) 47:351–4. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00230-9

22. Zarate CA, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2006) 63:856–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856

23. Diazgranados N, Ibrahim L, Brutsche NE, Newberg A, Kronstein P, Khalife S, et al. A randomized add-on trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2010) 67:793–802. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.90

24. Zarate CA Jr., Brutsche NE, Ibrahim L, Franco-Chaves J, Diazgranados N, Cravchik A, et al. Replication of ketamine's antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: a randomized controlled add-on trial. Biol Psychiatry. (2012) 71:939–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010

25. Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Green CE, Perez AM, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:1134–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392

26. Lapidus KA, Levitch CF, Perez AM, Brallier JW, Parides MK, Soleimani L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. (2014) 76:970–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.026

27. Lai R, Katalinic N, Glue P, Somogyi AA, Mitchell PB, Leyden J, et al. Pilot dose–response trial of iv ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2014) 15:579–84. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2014.922697

28. Marcantoni WS, Akoumba BS, Wassef M, Mayrand J, Lai H, Richard-Devantoy S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of intravenous ketamine infusion for treatment resistant depression: January 2009–January 2019. J Affect Disord. (2020) 277:831–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.007

29. Krupitsky EM, Grinenko AY. Ketamine psychedelic therapy (KPT): a review of the results of ten years of research. J Psychoactive Drugs. (1997) 29:165–83. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1997.10400185

30. Kolp E, Young MS, Friedman H, Krupitsky E, Jansen K, O'Connor L. Ketamine-enhanced psychotherapy: preliminary clinical observations on its effects in treating death anxiety. Int J Transpers Stud. (2007) 26:1–7. doi: 10.24972/ijts.2007.26.1.1

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Calabrese L. Titrated serial ketamine infusions stop outpatient suicidality and avert ER visits and hospitalizations. Int J Psychiatr Res. (2019) 2:1–2. Available online at: http://scivisionpub.com/pdfs/titrated-serial-ketamine-infusions-stop-outpatient-suicidality-and-avert-er-visits-and-hospitalizations-918.pdf

32. Dore J, Turnipseed B, Dwyer S, Turnipseed A, Andries J, Ascani G, et al. Ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP): patient demographics, clinical data and outcomes in three large practices administering ketamine with psychotherapy. J Psychoactive Drugs. (2019) 51:189–98. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2019.1587556

33. Wheeler SW, Dyer NL. A systematic review of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for mental health: an evaluation of the current wave of research and suggestions for the future. Psychol Conscious. (2020) 7:279. doi: 10.1037/cns0000237

34. Halstead M, Reed S, Krause R, Williams MT. Ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD related to racial discrimination. J Clin Case Stud. (2021) 20:310–30. doi: 10.1177/1534650121990894

35. Mills IH, Park GR, Manara AR, Merriman RJ. Treatment of compulsive behaviour in eating disorders with intermittent ketamine infusions. QJM. (1998) 91:493–503. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/91.7.493

36. Dechant E, Boyle B, Ross RA. Ketamine in a patient with comorbid anorexia and MDD. J Women's Health Dev. (2020) 3:373–5. doi: 10.26502/fjwhd.2644-28840044

37. Scolnick B, Zupec-Kania B, Calabrese L, Aoki C, Hildebrandt T. Remission from chronic anorexia nervosa with ketogenic diet and ketamine: case report. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:763. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00763

38. Schwartz T, Trunko ME, Feifel D, Lopez E, Peterson D, Frank GK, et al. A longitudinal case series of IM ketamine for patients with severe and enduring eating disorders and comorbid treatment-resistant depression. Clin Case Rep. (2021) 9:e03869. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3869

39. Gagnier J, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley DS, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. (2013) 67:46–51. doi: 10.1111/head.12246

40. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O'Connor M. The eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. (1993) 6:1–8.

Google Scholar

41. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O'Connor M. Eating Disorder Examination (Edition 16.0 D). In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2008). p. 265–308.

42. Nitsch A, Dlugosz H, Gibson D, Mehler PS. Medical complications of bulimia nervosa. Clevel Clin J Med. (2021) 88:333–43. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.88a.20168

43. Andrade C. Ketamine for depression, 4: in what dose, at what rate, by what route, for how long, and at what frequency? J Clin Psychiatry. (2017) 78:e852–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17f11738

44. Peyrovian B, McIntyre RS, Phan L, Lui LM, Gill H, Majeed A, et al. Registered clinical trials investigating ketamine for psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. (2020) 127:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.03.020

45. Murrough JW, Perez AM, Pillemer S, Stern J, Parides MK, aan het Rot M, et al. Rapid and longer-term antidepressant effects of repeated ketamine infusions in treatment-resistant major depression. Biol Psychiatry. (2013) 74:250–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.022

46. Albott CS, Lim KO, Forbes MK, Erbes C, Tye SJ, Grabowski JG, et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of repeated ketamine infusions for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. (2018) 79:17m11634. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11634

47. Phillips JL, Norris S, Talbot J, Birmingham M, Hatchard T, Ortiz A, et al. Single, repeated, and maintenance ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2019) 176:401–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18070834

48. Krystal JH, Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Charney DS, Duman RS. Ketamine: a paradigm shift for depression research and treatment. Neuron. (2019) 101:774–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.005

49. McGhee LL, Maani CV, Garza TH, Gaylord KM, Black IH. The correlation between ketamine and posttraumatic stress disorder in burned service members. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2008) 64:S195–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160ba1d

50. Feder A, Parides MK, Murrough JW, Perez AM, Morgan JE, Saxena S, et al. Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2014) 71:681–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.62

51. Feder A, Rutter SB, Schiller D, Charney DS. The emergence of ketamine as a novel treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Adv Pharmacol. (2020) 89:261–86. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2020.05.004

52. aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, Perez AM, Reich DL, Charney DS, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. (2010) 67:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038

53. Newport DJ, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, Potash JB, Tohen M, Nemeroff CB, et al. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am J Psychiatry. (2015) 172:950–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040465

Keywords: bulimia nervosa, eating disorder, binge-eating, purging, ketamine, ketamine assisted psychotherapy, psychopharmacology, case report

Citation: Ragnhildstveit A, Jackson LK, Cunningham S, Good L, Tanner Q, Roughan M and Henrie-Barrus P (2021) Case Report: Unexpected Remission From Extreme and Enduring Bulimia Nervosa With Repeated Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatry 12:764112. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.764112

Received: 25 August 2021; Accepted: 27 October 2021; Published: 17 November 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Ragnhildstveit, Jackson, Cunningham, Good, Tanner, Roughan and Henrie-Barrus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anya Ragnhildstveit, anya.ragnhildstveit@utah.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- June 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 6 CURRENT ISSUE pp.461-564

- May 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 5 pp.347-460

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

The Outcome of Bulimia Nervosa: Findings From One-Quarter Century of Research

- Hans-Christoph Steinhausen M.D., Ph.D., D.M.Sc.

- Sandy Weber Cand.Phil.

Search for more papers by this author

Objective: The present review addresses the outcome of bulimia nervosa, effect variables, and prognostic factors. Method: A total of 79 study series covering 5,653 patients suffering from bulimia nervosa were analyzed with regard to recovery, improvement, chronicity, crossover to another eating disorder, mortality, and comorbid psychiatric disorders at outcome. Forty-nine studies dealt with prognosis only. Final analyses on prognostic factors were based on 4,639 patients. Results: Joint analyses of data were hampered by a lack of standardized outcome criteria. There were large variations in the outcome parameters across studies. Based on 27 studies with three outcome criteria (recovery, improvement, chronicity), close to 45% of the patients on average showed full recovery of bulimia nervosa, whereas 27% on average improved considerably and nearly 23% on average had a chronic protracted course. Crossover to another eating disorder at the follow-up evaluation in 23 studies amounted to a mean of 22.5%. The crude mortality rate was 0.32%, and other psychiatric disorders at outcome were very common. Among various variables of effect, duration of follow-up had the largest effect size. The data suggest a curvilinear course, with highest recovery rates between 4 and 9 years of follow-up evaluation and reverse peaks for both improvement and chronicity, including rates of crossover to another eating disorder, before 4 years and after 10 years of follow-up evaluation. For most prognostic factors, there was only conflicting evidence. Conclusions: One-quarter of a century of specific research in bulimia nervosa shows that the disorder still has an unsatisfactory outcome in many patients. More refined interventions may contribute to more favorable outcomes in the future.

The introduction and definition of bulimia nervosa were presented only 30 years ago. In his salient publication, Gerald Russell (1) emphasized the dread of overeating, various compensatory measures, and the morbid fear of gaining weight and getting fat. Within this relatively short period of time, a remarkably large number of outcome studies have been published. Early reviews included one review based on eight studies (2) and another on 24 follow-up studies (3) . The latter found a mean recovery rate of 47.5% and mean rates of 26% for both improvement and chronicity. Shortly before the turn of the century, Keel and Mitchell (4) analyzed the course of 56 patient series and found a recovery rate of 50% and chronicity in 20% of the patients. The mortality rate of 0.3% was slightly lower than that reported in the prior review of 24 studies (3) . The review by Vaz (5) concentrated on prognostic factors only, and Quadflieg and Fichter (6) reviewed various outcome measures in a total of 33 studies. Finally, a recent, more selective review based on very rigorous inclusion criteria by Berkman et al. (7) provided findings from 13 patient series. Steinhausen’s analysis (8) of the outcome of anorexia nervosa in the second half of the last century served as a model for the present review.

Selection criteria for the inclusion of studies in the present review were 1) data on at least one out of five outcome measures for bulimia nervosa after a minimum follow-up evaluation period of 6 months following the treatment episode and/or 2) data on any prognostic factor of the disorder. The aforementioned reviews consisted of a total of 141 studies. A systematic search with various databases was performed using the terms “bulimia nervosa,” “outcome,” “follow-up,” and “prognosis.” A search using PubMed led to an additional 60 studies, and a search using PsycINFO resulted in 19 studies. Thus, before applying any exclusion criteria, a total of 220 published studies were available. As a result of duplicate or review-type studies, 68 studies were excluded. Furthermore, 26 studies did not include sufficient information on the duration of follow-up evaluation or provided pre-post measures only or were based only on follow-up periods <6 months. In another 21 studies, information on the course of the disorder was insufficient (e.g., no information on sample size or no independent assessment of anorexia and bulimia nervosa patients was provided). Finally, there were 14 studies dealing with prognostic factors only, and another 12 studies presented additional data based on the same patient cohort. Thus, at the end, a total of 79 patient series were entered into the analyses for the outcome of bulimia nervosa in the present review. Findings were published between 1981 and 2007. Data based on reports from a total of 32 studies were extracted by the expert senior author. Decisions on the inclusion of the remaining studies were jointly made by both the junior and senior authors.

Study Characteristics

The 79 published reports (9 – 87) were composed of 5,653 patients (group mean size=71.6 [SD=113.4], range=4–884). There were considerable differences in design, group size, methods, duration of follow-up evaluation, and missing data. Diagnostic classification changed considerably over the period in which the studies were conducted. Since the 1990s, there has been an increasing reliance on DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. In 46 studies consisting of 2,508 patients, the mean age at onset was 17.2 years (SD=1.7, range=4.3–23.2), and the mean age at follow-up assessment was 28.4 years (SD=4.3, range=16.6–38.0) in 39 studies consisting of 2,478 patients. The mean duration of follow-up evaluation varied between 6 months and 12.5 years (mean=3.2 months [SD=3.3]) in 77 studies of 5,239 patients. In 66 studies of 3,830 patients, a total of 75 men (1.9%) were included.

A minority of studies used combined intervention and follow-up evaluation, whereas the majority of studies used only limited evaluation of treatment effects. The available information on treatment was classified as 1) nonbehavioral psychotherapy, 2) unspecified medical intervention, 3) cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), 4) family intervention, or 5) mixed or uncontrolled intervention.

In the analyses for prognostic factors, 35 studies included information on prognostic factors in addition to data on outcome (10 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 30 , 34 – 36 , 40 – 44 , 52 , 54 , 55 , 57 , 61 , 63 , 65 , 68 , 71 – 73 , 75 , 76 , 83 , 88 – 92) , and 14 studies (93 – 106) dealt exclusively with prognostic factors. The total sample of these studies on prognosis consisted of 4,639 patients (mean=94.62 [SD=133.76], range=4–884).

Outcome Measures

The five central outcome criteria for the present analyses were recovery, improvement, chronicity, mortality, and crossover to other eating disorders. In addition, information on comorbid mental disorders was collected. Information on recovery was provided in the studies as part of 1) a three-level classification in combination with improvement and chronicity, 2) a two-level classification mostly in combination with chronicity, or 3) a single criterion. There were 22 synonyms of recovery (e.g., “abstinent”). Improvement was most commonly used as a medium category of a three-level classification. In a few instances, rates of improvement were reported in combination with recovery only. Among the 27 synonyms of improvement were terms such as “intermediate course,” “some remaining symptoms,” or “partial remission.” Finally, among 21 synonyms of chronicity, the most common were “bulimia nervosa,” and “poor course.” Some studies used crossover to another eating disorder according to DSM-IV criteria as an outcome category in addition to recovery and chronicity. All mortality rates represented crude mortality rates. None of the studies reported standardized mortality rates.

Statistical Analyses

The five outcome measures were calculated in percentages that were rounded to the nearest whole value. In order to take into account the large variation in sample sizes, weighted percentages were calculated by weighting each reported rate with the size of the study group. Data for all studies were converted into individual data for performance of statistical analyses using SPSS 14 (SPSS, Chicago).

All analyses were based on adjusted sample sizes at follow-up assessments rather than actual sample sizes after patient recruitment. Differences between these two figures were considered the dropout rate. The latter was dichotomized into high (≥16% of the original sample) and low (0%–15% of the original sample) categories and served as a first independent effect variable. In accordance with previous analyses (8) , the duration of follow-up evaluations was the second independent effect variable and categorized as <4 years, 4 to 9 years, or ≥10 years. Studies with a variable length of course were not considered for analyses of effect. In case there was more than one report based on the same cohort, only the last report with the longest duration of follow-up assessment was considered for the analyses. The third independent variable was represented by the type of intervention. Because of limited data, the aforementioned classification of available information on treatment into five types was restricted to the following three types: nonbehavioral psychotherapy, unspecified medical therapy, and CBT.

Effects of these three variables for treatment type on four outcome measures were analyzed using multivariate analyses of variance. In addition, effect sizes were calculated using partial eta-squared (η 2 ) as a measure of association between independent and dependent variables. According to Cohen (107) , η 2 =0.01–0.059 represents a small effect, η 2 =0.06–0.13 represents a median effect, and there is a large effect starting with η 2 =0.14. Furthermore, the frequencies of positive, negative, and insignificant prognostic factors were calculated.

Main Outcome Findings

Detailed information on crossover diagnoses was available in 23 studies. As shown in Table 1 , more than one-fifth of the patients fulfilled this criterion, with a majority of 16% on average crossing over to eating disorder not otherwise specified, which in most cases was a subclinical manifestation of bulimia nervosa, and nearly 6% on average developed full anorexia nervosa. A few patients developed binge eating disorder.

Seventy-six studies reported on mortality, and there were 14 deaths among 4,309 patients, leading to a crude mortality rate of 0.32%. For two patients, car accidents were the cause of death, four deaths were the result of suicide, one death was the result of a drug overdose, two deaths were caused by an eating disorder, and no causes of death were given for two subjects.

There was a large list of reported comorbid mental disorders. At follow-up assessments, patients most frequently suffered from affective disorders, followed by neurotic disorders (mostly anxiety disorders). Nonspecific personality disorders and borderline personality disorder were also frequent. Substance use disorders were less frequently seen, and obsessive-compulsive and schizophrenia spectrum disorders were described only in a single study.

Findings From Repeated Follow-Up Assessments

A few studies shed some light on the differential course of bulimia nervosa across time. Fichter and Quadflieg (91) published findings after 2-, 6-, and 12-year follow-up evaluations (34) and found substantial improvement in patients who completed longer follow-up assessment periods. Similarly, in the study by Herzog et al. (42) , recovery rates increased between the first follow-up assessment after 2 years and the second follow-up assessment after 7 years, but rates of improvement and chronicity declined correspondingly. Another study on intervention (59) found that the reduction of binge eating episodes and compensatory vomiting and laxative abuse remained constant between the 6- and 12-month follow-up evaluations. A change in outcome rates was observed in two smaller studies. Nevonen and Broberg (64) found a decreased recovery rate and an increased improvement rate between 1 and 2.5 years of follow-up evaluation when comparing individual and group psychotherapy. Similarly, in a very small sample of six patients, Toro et al. (80) observed that all patients were recovered at the first follow-up evaluation, but only four patients remained recovered after 25 years.

Intervention Effects on Outcome

There are various intervention studies on bulimia nervosa that include follow-up assessments. Two studies (28 , 30) compared three types of interventions and found that both interpersonal therapy and CBT were superior to behavior therapy without cognitive components. Other studies reported that CBT was superior to interpersonal therapy (29 , 84) or found no significant differences in the effects of either CBT or the combination of behavior therapy and hypnotherapy (40) . In another study (12) , more patients became symptom-free by the use of a self-help manual rather than CBT. Physical activity, but not diet counseling, was shown to be superior to CBT in one report (78) .

In a study on the optimization of CBT (82) , one group of patients used a self-help manual and received additional CBT when necessary. The other patients received behavior therapy only. There were no significant differences between these two approaches. In a study on the effectiveness of either the antidepressant fluoxetine or interpersonal therapy after a first inefficient phase of CBT (62) , no significant differences between the two approaches were found.

When comparing the effects of the antidepressant desipramine, CBT, or a combination of both measures (11) , CBT or the combined intervention resulted in stronger reduction of symptoms after 24 weeks relative to the pure antidepressant treatment. Adding exposure and response prevention to CBT did not result in improved results (19) . Another study (59) revealed that relative to a coping with stress program, diet counseling led to a more rapid improvement of eating behavior and to reduction and abstinence of binge eating episodes.

Two studies on the effects of family therapy revealed contradictory findings. One study (74) found that family intervention was inferior to individual psychotherapy, whereas family therapy was found to be superior in another study (39) . No significant differences were found in the effectiveness of group versus individual psychotherapy (64) . Finally, a positive effect of after-treatment control visits on the course of bulimia nervosa has been documented (58) .

Effect Variables

As a result of methodological restrictions, the presentation of findings based on effect analyses was limited to the set of 27 studies that used the three-level classification with recovery, improvement, and chronicity, supplemented by the smaller number of studies that provided additional information on rates of diagnoses for crossover to other eating disorders. There were no missing data in this data set.

Dropout rate

Duration of follow-up evaluation.

Bulimia Nervosa Clinical Presentation

- Author: Guido Klaus Wilhelm Frank, MD; Chief Editor: David Bienenfeld, MD more...

- Sections Bulimia Nervosa

- Practice Essentials

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology

- Mortality/Morbidity

- Patient Education

- Diagnostic Criteria

- Physical Examination

- Comorbidities

- Complications

- Laboratory Studies

- Imaging Studies

- Other Tests

- Approach Considerations

- Medical Care

- Nonpharmacologic Interventions

- Pharmacologic Treatments

- Surgical Care

- Consultations

- Long-Term Monitoring

- Media Gallery

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is often not diagnosed for many months or even years after onset because of patients' secretiveness about their symptoms, usually associated with a great deal of shame. These patients often see physicians for other problems, such as anxiety, depression, infertility, bowel irregularities, fatigue, or palpitations. Similarly, they may see mental health professionals for mood and anxiety problems, personality issues, relationship issues, histories of childhood or adolescent trauma, or substance abuse, without revealing the presence of an eating disorder.

One common presenting scenario is that of a patient who is concerned about their weight who seeks help with weight loss. Symptoms may include bloating, constipation, and menstrual irregularities. Far less often, people may present with palpitations resulting from arrhythmias, which are often associated with electrolyte abnormalities and dehydration. BN is also often, but not always, characterized by an inappropriate premium placed on slender physical appearance. It is important to note that the diagnostic criteria do not necessarily require an individual to express a desire to lose weight or change their appearance to meet criteria for BN. Some, especially younger patients, may not be able or willing to articulate why they engage in eating disorder behaviors. Others may express a motivation for control, a fear of fullness, or other reasons for their disordered eating behaviors. Failure to make an appropriate eating disorder diagnosis that an individual would otherwise meet criteria for, whether it be anorexia nervosa (AN), BN, or other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED), because of a lack of expressed concern or denial of concern about body weight/shape is dangerous for patients’ physical and mental health due to causing delays in diagnosis that can contribute to significant morbidity and mortality.

A dietary history may reveal attempts to control weight by dieting and abstaining entirely from high-calorie foods at all times except during binge eating episodes. Often, an all-encompassing preoccupation with food and eating is present, and recurring cycles of extreme dieting and/or fasting may alternate with gorging behavior. The clinician should inquire further about types of foods and quantities of foods consumed when a patient endorses binging behavior. A binge eating episode, by definition, must constitute consumption of more food than would typically be consumed in a single setting by an individual, so there is some subjectivity in what is a binge. Some patients with AN or with periods of very restrictive eating patterns may endorse a “binge,” but on further inquiry may be describing an episode that would be either less than or normative for typical eating for a non-eating-disordered individual but perceived subjectively as a binge eating episode. In the context of highly restrictive eating, any instance of normative eating, such as consuming a dessert, eating high-calorie snacks, or even allowing oneself to eat until feeling full, might appear to be binge eating to an individual who is used to eating very little amounts of food most of the time.

Most patients self-induce vomiting by gagging themselves with their fingers or a toothbrush. Some patients are able to regurgitate reflexively, without requiring external stimulation of the pharynx. [ 34 ] A minority of patients will chew, then regurgitate, without actually swallowing the food. One particularly dangerous form of vomiting is via induction through the use of emetics (eg, ipecac). Ipecac is a tightly binding and slowly released mycotoxin that may lead to fatal cardiomyopathy in habitual users. Up to 40% of patients misuse laxatives, thinking that their use will help them lose weight. In fact, laxative misuse results in additional dehydration and often electrolyte abnormalities as well. Screening for laxative use should be a routine topic of assessment.

For children and adolescents, the parents/guardians of the patient should be asked to check for signs of vomiting and laxative misuse in the home when the patient is denying purging behavior but there is a strong suspicion of purging behaviors occurring. Indications of surreptitious purging behaviors that parents/guardians should be instructed to look for in the home include hidden vomitus in concealed places in the home (eg, closets, floorboards), concealed laxatives in the patients’ room or belongings, clogged drains with vomit, vomit in trash cans, and so on. The parents/guardians should also be instructed to be observant for other signs of purging behavior both for diagnostic and preventative purposes such as unusual online orders (which could be for laxatives or other emetics) and unusually long periods of time spent in the bathroom or shower, which may or may not be after meals and may or may not be accompanied by retching noises. For both children and adults, collateral informants can be very useful sources of information for the clinician about surreptitious purging or other eating disorder behaviors.

Clinicians should be aware of misconceptions that eating disorders are almost exclusively present in young women to avoid missing diagnoses of BN or other eating disorders in male patients or older patients. Additionally, it is a misconception that eating disorders, including BN, mostly occur in White women and people from Western cultures. While research is still evolving on the epidemiology of BN and other eating disorders in males, older individuals, people in developing countries, and so on, in the authors’ clinical experiences, we have encountered a great many patients with BN and other eating disorders who are male, not White, and of a great many different ethnic and racial backgrounds.

Patients with BN may experience the following symptoms:

General - Dizziness, lightheadedness, palpitations (due to dehydration, orthostatic hypotension, possibly hypokalemia)

Gastrointestinal symptoms - Pharyngeal irritation, abdominal pain (more common among persons who self-induce vomiting), blood in vomitus (from esophageal irritation and more rarely actual tears, which may be fatal), difficulty swallowing, bloating, flatulence, constipation, and obstipation

Pulmonary symptoms - Uncommonly aspiration pneumonitis or, more rarely, pneumomediastinum

A high index of suspicion is required in any depressed or anxious weight-conscious young woman.

A set of screening questions, such as the SCOFF mnemonic questionnaire, [ 35 ] is useful to obtain a quick impression as to the potential need for further in-depth questioning. The SCOFF questionnaire includes the following 5 questions:

Do you make yourself S ick because you feel uncomfortably full?

Do you worry you have lost Co ntrol over how much you eat?

Have you recently lost more than O ne stone (about 14 lbs or 6.35 kg) in a 3-month period?

Do you believe yourself to be F at when others say you are too thin?

Would you say that F ood dominates your life?

The Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (ESP) questionnaire is an alternative screening tool. [ 36 ] It contains the following 5 questions:

Are you satisfied with your eating patterns?

Do you ever eat in secret?

Does your weight affect the way you feel about yourself?

Have family members suffered from an eating disorder?

Do you currently suffer with or have you in the past suffered with an eating disorder?

The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) is a self-report population-based screening instrument that patients can complete in the waiting room prior to seeing the health care provider. [ 37 ] (See Psych Central for more information.)

Family history of eating disorders, anxiety, mood disorders, and alcohol and/or substance abuse/dependence may contribute to the risk of BN and should be investigated.

Generally, patients with BN are more likely than controls to view their families as conflicted, badly organized, non-cohesive, and lacking in nurturance and caring. These patients have also been shown to more often appear to be angrily submissive to hostile and neglectful parents.

Perceptions of appearance-related teasing by family members may be present. [ 38 ]

For individuals still living with their parents, careful assessment of the family’s dynamics should be undertaken.

Physiological abnormalities

Many physiological abnormalities may be seen in association with eating disorders, but virtually all appear to be consequences of the abnormal behaviors, not their causes. In most cases of BN, laboratory abnormalities are relatively minor. In cases of very frequent purging (eg, daily or multiple times per day), abnormalities in electrolyte and serum amylase levels occur, but these and most other laboratory abnormalities are reversible with weight restoration and cessation of compensatory behaviors.

Among the identified metabolic consequences sometimes seen in BN are low plasma insulin, C peptide, triiodothyronine, and glucose values, as well as increased beta-hydroxybutyrate and free fatty acid levels. Both fasting and post-binge/post-vomiting hypoglycemia are sometimes seen in some patients with BN. Some studies suggest increased secretory diurnal amplitudes in cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in BN as well as blunted responses to corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH). However, these findings have been inconsistent among research studies.

Reports have also suggested abnormal responses to dexamethasone suppression like those seen in AN and major depressive disorder, more common among individuals with significant dietary restriction. Some authors have attributed these abnormalities to impaired dexamethasone absorption, which is demonstrated in some patients with BN. Similar to findings in AN, patients with BN tend to have higher growth hormone levels at night, while nocturnal prolactin levels tend to be less than those seen in controls.

About half of women with BN have anovulatory cycles, while about 20% have luteal phase defects. Patients with anovulatory cycles generally have impaired luteinizing hormone pulsatile secretion patterns and associated reduced estradiol and progesterone pulse amplitudes. [ 39 , 40 ]

Although the implications of many research findings are still unclear, and none of the following offer clinical tests of any merit, reports suggest involvement of the serotonin transporter, [ 41 , 42 ] autoantibodies against neuropeptides, [ 43 ] various chromosome regions, [ 44 ] brain-derived neurotrophic factor, [ 45 ] and peptides leptin and ghrelin. [ 46 ] In a few instances, cerebral hemispheric lesions may be involved in pathogenesis. [ 47 ] Regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities have been noted in adolescents. [ 48 ] Endogenous opioids and beta-endorphins have been implicated in the maintenance of binge eating. Therefore, diagnosis of BN and other eating disorders should be made mostly on the basis of interview with the patient and their collateral informants as well as behavioral observation at times (eg, purging witnessed by family or a staff member). Laboratory tests and physical examination can provide important information about comorbid medical sequelae of BN, but diagnosis requires a thorough diagnostic interview and clinical history.

The underlying causes for buimia nervosa (BN) remain elusive. However, a variety of biological and psychological factors have been suggested to be involved the development of BN.

Behavioral traits

BN has long been associated with inadequate mechanisms to control food intake beyond ones physiological needs, and behavioral traits could contribute. [ 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 ]

Emotion regulation has been defined as the “extrinsic and intrinsic process responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions, to accomplish one’s goals." [ 188 ] A disturbance in emotion regulation has been found in eating disorders. [ 189 ] Individuals with BN have difficulties modulating strong emotions and controlling rash, impulsive response. [ 190 ] Most but not all studies suggest that negative affect precedes binge eating episodes, [ 191 ] followed by initial relief. [ 192 , 193 ]

Impulsivity, the “opposite to aspects of executive function,” [ 194 ] is a tendency to act with insufficient forethought, or a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard for the negative consequences of these reactions. Impulsivity has relevance for binge eating behaviors, as those episodes typically occur impulsively in response to an external or internal trigger. Increased impulsivity had been found across BN. [ 195 , 196 ] Overall, the literature on executive function in BN is limited, but there is evidence that altered impulsivity and executive function distinguish binge eating individuals from normal weight or obese controls.

Negative urgency, the tendency to experience strong impulses under the influence of negative emotions, or to act rashly when distressed, is related to emotion regulation and impulsivity and has been associated with binge eating. [ 197 , 198 ] Negative urgency is a trait that is triggered by negative affect and may result in binge eating in vulnerable individuals. [ 199 , 200 , 201 , 202 , 203 , 204 ] Interestingly, negative urgency and affect seem to be more relevant than impulsivity, at least for some with binge eating. [ 205 ]

Sensitivity to reward and punishment described in the reinforcement sensitivity theory (RST) provides a framework for how differences in brain systems' responsiveness to reward and punishment are reflected in individual personality. [ 206 , 207 ] Reward sensitivity influences decision making in eating disorders. [ 208 ] Sensitivity to reward was found elevated in BN and it has been hypothesized that an imbalance between reward sensitivity, impulsivity and inhibition are mechanistically involved in binge eating. [ 209 , 210 , 211 ] In addition, individuals with binge eating behaviors showed greater risk taking, and obese binge eating disorder has been associated with altered value computation and discrimination of salient stimuli. [ 212 ]

Taken together, emotion regulation, impulsivity, negative affect, negative urgency, and sensitivity to reward have been linked to binge eating and may create a vulnerability for developing or perpetuation BN behaviors. [ 213 ] However, we do not have a transdiagnostic model for their underlying neurobiology.

Neurocircuitry of emotion regulation, impulsiveness, and cognitive control in BN

A complex interplay exists between emotion regulation and cognitive control. Emotions affect attention, drive cognitive bias, and may interrupt proper decision making; on the other hand, attention to specific goals can control emotions and override strong feelings. [ 214 , 215 , 216 ] Control of food cravings is thought to involve prefrontal cortical areas, whereas greater caloric intake has been related to higher activation in gustatory cortex and brain regions for reward computation. [ 217 , 218 , 219 ] Little is known about how emotion regulation and cognitive control circuits affect binge eating. One study found reduced prefrontal cortical activity in BN when viewing food pictures. [ 220 ] BN showed hypoactivity in brain areas involved in self-regulation and impulse control, such as the prefrontal cortex or insula. [ 221 , 222 , 223 , 224 ] Only one study directly investigated negative affect in relation to binge eating in BN, finding a positive correlation between negative affect and striatal brain response during anticipation of a milkshake. [ 225 ] Altogether, studies suggest altered brain function related to emotion regulation in individuals with binge eating, but the literature is inconsistent.

Neurotransmitters and hormones

Animal models have shown that dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine have all been associated with cognitive control and impulse control in frontal cortical circuits. [ 226 , 227 ] For instance, dopamine D2 and serotonin 2A and 2C receptor signaling can modulate impulsivity. [ 228 , 229 ] Human studies in BN found that serotonin 1A or dopamine D2/3 receptor binding correlated with harm avoidance or behavior inhibition. [ 230 , 231 ] Endocrine factors such as ghrelin, leptin, sex hormones, and cortisol can influence food intake behaviors, [ 232 ] but how they contribute to eating disorders is still elusive. [ 233 , 234 ] Basic research on the gut–brain axis showed how leptin or ghrelin activate brain stem and ventral striatum to activate dopamine circuits and motivation to eat. [ 231 , 234 ] Stress, via cortisol and gut hormone activation, leads to dopamine-mediated decreased food intake in animals, although in humans stress often leads to increased food intake, suggesting a different pathophysiology. [ 235 ] Dopamine drives motivation and food approach, while hedonic aspects of food intake (“liking”) are processed by opioids. [ 236 , 237 ] Those systems could be altered premorbidly as a vulnerability factor but also change in response to extremes of eating, which is an important part of our overall model of eating disorder pathophysiology. [ 238 ] Dopamine has a unique position. It is the only neurotransmitter that we have a mathematical understanding of neuronal function for, which can be used for computational modeling of brain function. Dopamine mediates reward learning [ 239 ] and has been implicated in the pathophysiology of taste and reward processing in eating disorders using the so-called prediction error model, which provides a very strong framework to study reward function in eating disorders. [ 240 , 241 , 242 , 243 , 244 ]

Although patients with bulimia nervosa (BN) are often unremarkable in general appearance and frequently have no signs of illness on physical examination, several characteristic findings may occur.

Physical findings may include the following:

- Bilateral parotid enlargement, largely consequent to noninflammatory stimulation of the salivary glands, may be seen. [ 65 ] See parotid gland swelling in following image.

Parotid hypertrophy. Reprinted with permission from Mandel, L and Siamak, A. Diagnosing bulimia nervosa with parotid gland swelling. J Am Dent Assoc 2004, Vol 135, No 5, 613-616.

See the list below:

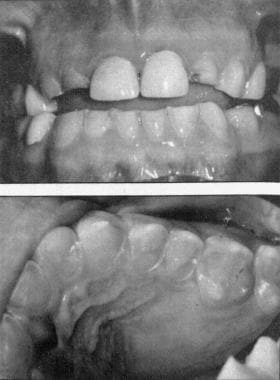

- In patients with significant self-induced vomiting, erosions of the lingual surface of the teeth, loss of enamel, periodontal disease, and extensive dental caries may be observed, as in the following image. [ 66 ]

Dental caries. Reprinted with permission from Wolcott, RB, Yager, J, Gordon, G. Dental sequelae to the binge-purge syndrome (bulimia): report of cases. JADA. 1984; 109:723-725.

- Russell sign (one of the few physical examination findings in psychiatry) manifests as callosities, scarring, and abrasions on the knuckles secondary to repeated self-induced vomiting. [ 67 ]

Russell sign. Reprinted with permission from Glorio R, et al. Prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in 200 patients with eating disorders. Int J Derm, 2000, 39(5), 348-353.

Other cutaneous manifestations can include telogen effluvium (sudden, diffuse hair loss), acne, xerosis (dry skin), nail dystrophy (degeneration), and scarring resulting from cutting, burning, and other self-induced trauma. [ 68 ]

Other nonspecific but suggestive findings that may reflect the severity of the disease include bradycardia or tachycardia, hypothermia, and hypotension (often associated with dehydration). Edema, particularly of the feet (and less commonly the hands), is found more often among patients with a history of diuretic abuse, laxative abuse, or both or in patients with significant protein malnourishment causing hypoalbuminemia.

Some patients may be clinically obese, but morbid obesity is rare. Patients with BN who are overweight may have excessive fat folds that favor humidity and maceration with bacterial and fungal overgrowth, striae due to skin overextension, stasis pigmentation related to peripheral vascular disease, and plantar hyperkeratosis due to increased weight. [ 68 ]

A community-based household survey involving 52,095 adults in 19 countries found, after adjustment for pertinent comorbidities, that the rate of BN among the 2580 identified cases of adult-onset diabetes mellitus was twice that of non-diabetic individuals. [ 69 ]

A typical Mental Status Examination for a patient with BN is detailed below. (The formal Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination [MMSE] is usually unnecessary in the evaluation of patients with BN because symptoms of dementia and delirium are not common in these patients.)

Appearance: Patients are typically neat, well dressed, and show attention to detail. Grooming is often meticulous and may further demonstrate a patient's concern about personal appearance.

Behavior: Patients usually do not have kinetic abnormalities, but anxious feelings may heighten psychomotor agitation. Movements are spontaneous, and patients generally are cooperative and able to carry out requested tasks.

Cooperation: Patients generally avoid eye contact due to shame and embarrassment.

Mood and affect: Patients often demonstrate a depressed mood but may also have significant anxiety.

Speech: Content and articulation are generally normal.

Thought process: Patients likely have a linear thought process that is goal-directed.

Thought content: Thoughts tend to revolve around food and concerns regarding body image and weight.

Perceptual disturbances: Delusions and hallucinations are typically absent.

Suicidal ideation: Suicidal ideation is a significant consideration, especially in patients with depressed moo. Although suicidal ideation is often restricted to thoughts rather than concrete plans, suicidal thinking should be taken very seriously.

Homicidal ideations: Homicidal ideation is not typically associated with those diagnosed with BN.