Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2022

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

- Joanna Moncrieff 1 , 2 ,

- Ruth E. Cooper 3 ,

- Tom Stockmann 4 ,

- Simone Amendola 5 ,

- Michael P. Hengartner 6 &

- Mark A. Horowitz 1 , 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 28 , pages 3243–3256 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1.30m Accesses

287 Citations

9467 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Diagnostic markers

A Correspondence to this article was published on 16 June 2023

A Comment to this article was published on 16 June 2023

The serotonin hypothesis of depression is still influential. We aimed to synthesise and evaluate evidence on whether depression is associated with lowered serotonin concentration or activity in a systematic umbrella review of the principal relevant areas of research. PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO were searched using terms appropriate to each area of research, from their inception until December 2020. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses and large data-set analyses in the following areas were identified: serotonin and serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, concentrations in body fluids; serotonin 5-HT 1A receptor binding; serotonin transporter (SERT) levels measured by imaging or at post-mortem; tryptophan depletion studies; SERT gene associations and SERT gene-environment interactions. Studies of depression associated with physical conditions and specific subtypes of depression (e.g. bipolar depression) were excluded. Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed the quality of included studies using the AMSTAR-2, an adapted AMSTAR-2, or the STREGA for a large genetic study. The certainty of study results was assessed using a modified version of the GRADE. We did not synthesise results of individual meta-analyses because they included overlapping studies. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020207203). 17 studies were included: 12 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 1 collaborative meta-analysis, 1 meta-analysis of large cohort studies, 1 systematic review and narrative synthesis, 1 genetic association study and 1 umbrella review. Quality of reviews was variable with some genetic studies of high quality. Two meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining the serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, showed no association with depression (largest n = 1002). One meta-analysis of cohort studies of plasma serotonin showed no relationship with depression, and evidence that lowered serotonin concentration was associated with antidepressant use ( n = 1869). Two meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining the 5-HT 1A receptor (largest n = 561), and three meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining SERT binding (largest n = 1845) showed weak and inconsistent evidence of reduced binding in some areas, which would be consistent with increased synaptic availability of serotonin in people with depression, if this was the original, causal abnormaly. However, effects of prior antidepressant use were not reliably excluded. One meta-analysis of tryptophan depletion studies found no effect in most healthy volunteers ( n = 566), but weak evidence of an effect in those with a family history of depression ( n = 75). Another systematic review ( n = 342) and a sample of ten subsequent studies ( n = 407) found no effect in volunteers. No systematic review of tryptophan depletion studies has been performed since 2007. The two largest and highest quality studies of the SERT gene, one genetic association study ( n = 115,257) and one collaborative meta-analysis ( n = 43,165), revealed no evidence of an association with depression, or of an interaction between genotype, stress and depression. The main areas of serotonin research provide no consistent evidence of there being an association between serotonin and depression, and no support for the hypothesis that depression is caused by lowered serotonin activity or concentrations. Some evidence was consistent with the possibility that long-term antidepressant use reduces serotonin concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Beyond the serotonin deficit hypothesis: communicating a neuroplasticity framework of major depressive disorder

Genetic contributions to brain serotonin transporter levels in healthy adults

The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of 101 studies

Introduction.

The idea that depression is the result of abnormalities in brain chemicals, particularly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT), has been influential for decades, and provides an important justification for the use of antidepressants. A link between lowered serotonin and depression was first suggested in the 1960s [ 1 ], and widely publicised from the 1990s with the advent of the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Although it has been questioned more recently [ 5 , 6 ], the serotonin theory of depression remains influential, with principal English language textbooks still giving it qualified support [ 7 , 8 ], leading researchers endorsing it [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], and much empirical research based on it [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Surveys suggest that 80% or more of the general public now believe it is established that depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance’ [ 15 , 16 ]. Many general practitioners also subscribe to this view [ 17 ] and popular websites commonly cite the theory [ 18 ].

It is often assumed that the effects of antidepressants demonstrate that depression must be at least partially caused by a brain-based chemical abnormality, and that the apparent efficacy of SSRIs shows that serotonin is implicated. Other explanations for the effects of antidepressants have been put forward, however, including the idea that they work via an amplified placebo effect or through their ability to restrict or blunt emotions in general [ 19 , 20 ].

Despite the fact that the serotonin theory of depression has been so influential, no comprehensive review has yet synthesised the relevant evidence. We conducted an ‘umbrella’ review of the principal areas of relevant research, following the model of a similar review examining prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder [ 21 ]. We sought to establish whether the current evidence supports a role for serotonin in the aetiology of depression, and specifically whether depression is associated with indications of lowered serotonin concentrations or activity.

Search strategy and selection criteria

The present umbrella review was reported in accordance with the 2009 PRISMA statement [ 22 ]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO in December 2020 (registration number CRD42020207203) ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=207203 ). This was subsequently updated to reflect our decision to modify the quality rating system for some studies to more appropriately appraise their quality, and to include a modified GRADE to assess the overall certainty of the findings in each category of the umbrella review.

In order to cover the different areas and to manage the large volume of research that has been conducted on the serotonin system, we conducted an ‘umbrella’ review. Umbrella reviews survey existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses relevant to a research question and represent one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis available [ 23 ]. Although they are traditionally restricted to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we aimed to identify the best evidence available. Therefore, we also included some large studies that combined data from individual studies but did not employ conventional systematic review methods, and one large genetic study. The latter used nationwide databases to capture more individuals than entire meta-analyses, so is likely to provide even more reliable evidence than syntheses of individual studies.

We first conducted a scoping review to identify areas of research consistently held to provide support for the serotonin hypothesis of depression. Six areas were identified, addressing the following questions: (1) Serotonin and the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA–whether there are lower levels of serotonin and 5-HIAA in body fluids in depression; (2) Receptors - whether serotonin receptor levels are altered in people with depression; (3) The serotonin transporter (SERT) - whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter in people with depression (which would lower synaptic levels of serotonin); (4) Depletion studies - whether tryptophan depletion (which lowers available serotonin) can induce depression; (5) SERT gene – whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter gene in people with depression; (6) Whether there is an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression.

We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and large database studies in these six areas in PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO using the Healthcare Databases Advanced Search tool provided by Health Education England and NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). Searches were conducted until December 2020.

We used the following terms in all searches: (depress* OR affective OR mood) AND (systematic OR meta-analysis), and limited searches to title and abstract, since not doing so produced numerous irrelevant hits. In addition, we used terms specific to each area of research (full details are provided in Table S1 , Supplement). We also searched citations and consulted with experts.

Inclusion criteria were designed to identify the best available evidence in each research area and consisted of:

Research synthesis including systematic reviews, meta-analysis, umbrella reviews, individual patient meta-analysis and large dataset analysis.

Studies that involve people with depressive disorders or, for experimental studies (tryptophan depletion), those in which mood symptoms are measured as an outcome.

Studies of experimental procedures (tryptophan depletion) involving a sham or control condition.

Studies published in full in peer reviewed literature.

Where more than five systematic reviews or large analyses exist, the most recent five are included.

Exclusion criteria consisted of:

Animal studies.

Studies exclusively concerned with depression in physical conditions (e.g. post stroke or Parkinson’s disease) or exclusively focusing on specific subtypes of depression such as postpartum depression, depression in children, or depression in bipolar disorder.

No language or date restrictions were applied. In areas in which no systematic review or meta-analysis had been done within the last 10 years, we also selected the ten most recent studies at the time of searching (December 2020) for illustration of more recent findings. We performed this search using the same search string for this domain, without restricting it to systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Data analysis

Each member of the team was allocated one to three domains of serotonin research to search and screen for eligible studies using abstract and full text review. In case of uncertainty, the entire team discussed eligibility to reach consensus.

For included studies, data were extracted by two reviewers working independently, and disagreement was resolved by consensus. Authors of papers were contacted for clarification when data was missing or unclear.

We extracted summary effects, confidence intervals and measures of statistical significance where these were reported, and, where relevant, we extracted data on heterogeneity. For summary effects in the non-genetic studies, preference was given to the extraction and reporting of effect sizes. Mean differences were converted to effect sizes where appropriate data were available.

We did not perform a meta-analysis of the individual meta-analyses in each area because they included overlapping studies [ 24 ]. All extracted data is presented in Table 1 . Sensitivity analyses were reported where they had substantial bearing on interpretation of findings.

The quality rating of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was assessed using AMSTAR-2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) [ 25 ]. For two studies that did not employ conventional systematic review methods [ 26 , 27 ] we used a modified version of the AMSTAR-2 (see Table S3 ). For the genetic association study based on a large database analysis we used the STREGA assessment (STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies) (Table S4 ) [ 28 ]. Each study was rated independently by at least two authors. We report ratings of individual items on the relevant measure, and the percentage of items that were adequately addressed by each study (Table 1 , with further detail in Tables S3 and S4 ).

Alongside quality ratings, two team members (JM, MAH) rated the certainty of the results of each study using a modified version of the GRADE guidelines [ 29 ]. Following the approach of Kennis et al. [ 21 ], we devised six criteria relevant to the included studies: whether a unified analysis was conducted on original data; whether confounding by antidepressant use was adequately addressed; whether outcomes were pre-specified; whether results were consistent or heterogeneity was adequately addressed if present; whether there was a likelihood of publication bias; and sample size. The importance of confounding by effects of current or past antidepressant use has been highlighted in several studies [ 30 , 31 ]. The results of each study were scored 1 or 0 according to whether they fulfilled each criteria, and based on these ratings an overall judgement was made about the certainty of evidence across studies in each of the six areas of research examined. The certainty of each study was based on an algorithm that prioritised sample size and uniform analysis using original data (explained more fully in the supplementary material), following suggestions that these are the key aspects of reliability [ 27 , 32 ]. An assessment of the overall certainty of each domain of research examining the role of serotonin was determined by consensus of at least two authors and a direction of effect indicated.

Search results and quality rating

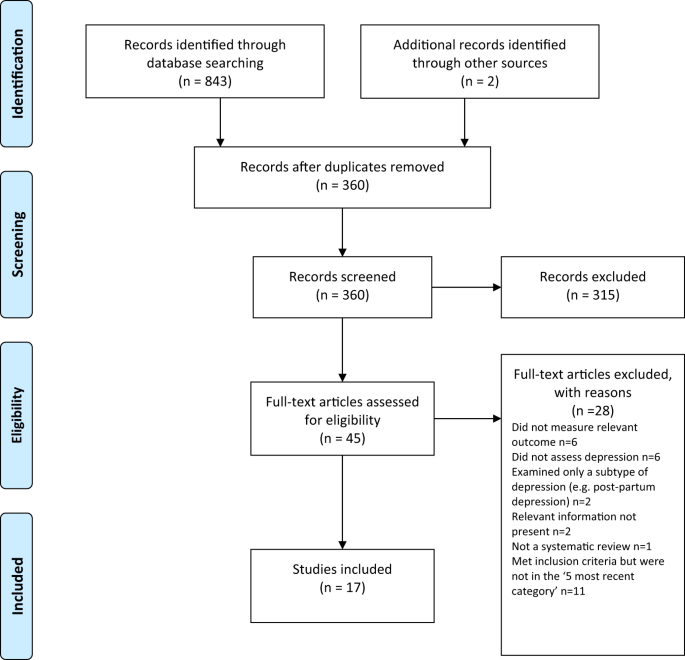

Searching identified 361 publications across the 6 different areas of research, among which seventeen studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 and Table S1 for details of the selection process). Included studies, their characteristics and results are shown in Table 1 . As no systematic review or meta-analysis had been performed within the last 10 years on serotonin depletion, we also identified the 10 latest studies for illustration of more recent research findings (Table 2 ).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagramme.

Quality ratings are summarised in Table 1 and reported in detail in Tables S2 – S3 . The majority (11/17) of systematic reviews and meta-analyses satisfied less than 50% of criteria. Only 31% adequately assessed risk of bias in individual studies (a further 44% partially assessed this), and only 50% adequately accounted for risk of bias when interpreting the results of the review. One collaborative meta-analysis of genetic studies was considered to be of high quality due to the inclusion of several measures to ensure consistency and reliability [ 27 ]. The large genetic analysis of the effect of SERT polymorphisms on depression, satisfied 88% of the STREGA quality criteria [ 32 ].

Serotonin and 5-HIAA

Serotonin can be measured in blood, plasma, urine and CSF, but it is rapidly metabolised to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). CSF is thought to be the ideal resource for the study of biomarkers of putative brain diseases, since it is in contact with brain interstitial fluid [ 33 ]. However, collecting CSF samples is invasive and carries some risk, hence large-scale studies are scarce.

Three studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (Table 1 ). One meta-analysis of three large observational cohort studies of post-menopausal women, revealed lower levels of plasma 5-HT in women with depression, which did not, however, reach statistical significance of p < 0.05 after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Sensitivity analyses revealed that antidepressants were strongly associated with lower serotonin levels independently of depression.

Two meta-analyses of a total of 19 studies of 5-HIAA in CSF (seven studies were included in both) found no evidence of an association between 5-HIAA concentrations and depression.

Fourteen different serotonin receptors have been identified, with most research on depression focusing on the 5-HT 1A receptor [ 11 , 34 ]. Since the functions of other 5-HT receptors and their relationship to depression have not been well characterised, we restricted our analysis to data on 5-HT 1A receptors [ 11 , 34 ]. 5-HT 1A receptors, known as auto-receptors, inhibit the release of serotonin pre-synaptically [ 35 ], therefore, if depression is the result of reduced serotonin activity caused by abnormalities in the 5-HT 1A receptor, people with depression would be expected to show increased activity of 5-HT 1A receptors compared to those without [ 36 ].

Two meta-analyses satisfied inclusion criteria, involving five of the same studies [ 37 , 38 ] (see Table 1 ). The majority of results across the two analyses suggested either no difference in 5-HT 1A receptors between people with depression and controls, or a lower level of these inhibitory receptors, which would imply higher concentrations or activity of serotonin in people with depression. Both meta-analyses were based on studies that predominantly involved patients who were taking or had recently taken (within 1–3 weeks of scanning) antidepressants or other types of psychiatric medication, and both sets of authors commented on the possible influence of prior or current medication on findings. In addition, one analysis was of very low quality [ 37 ], including not reporting on the numbers involved in each analysis and using one-sided p-values, and one was strongly influenced by three studies and publication bias was present [ 38 ].

The serotonin transporter (SERT)

The serotonin transporter protein (SERT) transports serotonin out of the synapse, thereby lowering the availability of serotonin in the synapse [ 39 , 40 ]. Animals with an inactivated gene for SERT have higher levels of extra-cellular serotonin in the brain than normal [ 41 , 42 , 43 ] and SSRIs are thought to work by inhibiting the action of SERT, and thus increasing levels of serotonin in the synaptic cleft [ 44 ]. Although changes in SERT may be a marker for other abnormalities, if depression is caused by low serotonin availability or activity, and if SERT is the origin of that deficit, then the amount or activity of SERT would be expected to be higher in people with depression compared to those without [ 40 ]. SERT binding potential is an index of the concentration of the serotonin transporter protein and SERT concentrations can also be measured post-mortem.

Three overlapping meta-analyses based on a total of 40 individual studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (See Table 1 ) [ 37 , 39 , 45 ]. Overall, the data indicated possible reductions in SERT binding in some brain areas, although areas in which effects were detected were not consistent across the reviews. In addition, effects of antidepressants and other medication cannot be ruled out, since most included studies mainly or exclusively involved people who had a history of taking antidepressants or other psychiatric medications. Only one meta-analysis tested effects of antidepressants, and although results were not influenced by the percentage of drug-naïve patients in each study, numbers were small so it is unlikely that medication-related effects would have been reliably detected [ 45 ]. All three reviews cited evidence from animal studies that antidepressant treatment reduces SERT [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. None of the analyses corrected for multiple testing, and one review was of very low quality [ 37 ]. If the results do represent a positive finding that is independent of medication, they would suggest that depression is associated with higher concentrations or activity of serotonin.

Depletion studies

Tryptophan depletion using dietary means or chemicals, such as parachlorophenylalanine (PCPA), is thought to reduce serotonin levels. Since PCPA is potentially toxic, reversible tryptophan depletion using an amino acid drink that lacks tryptophan is the most commonly used method and is thought to affect serotonin within 5–7 h of ingestion. Questions remain, however, about whether either method reliably reduces brain serotonin, and about other effects including changes in brain nitrous oxide, cerebrovascular changes, reduced BDNF and amino acid imbalances that may be produced by the manipulations and might explain observed effects independent of possible changes in serotonin activity [ 49 ].

One meta-analysis and one systematic review fulfilled inclusion criteria (see Table 1 ). Data from studies involving volunteers mostly showed no effect, including a meta-analysis of parallel group studies [ 50 ]. In a small meta-analysis of within-subject studies involving 75 people with a positive family history, a minor effect was found, with people given the active depletion showing a larger decrease in mood than those who had a sham procedure [ 50 ]. Across both reviews, studies involving people diagnosed with depression showed slightly greater mood reduction following tryptophan depletion than sham treatment overall, but most participants had taken or were taking antidepressants and participant numbers were small [ 50 , 51 ].

Since these research syntheses were conducted more than 10 years ago, we searched for a systematic sample of ten recently published studies (Table 2 ). Eight studies conducted with healthy volunteers showed no effects of tryptophan depletion on mood, including the only two parallel group studies. One study presented effects in people with and without a family history of depression, and no differences were apparent in either group [ 52 ]. Two cross-over studies involving people with depression and current or recent use of antidepressants showed no convincing effects of a depletion drink [ 53 , 54 ], although one study is reported as positive mainly due to finding an improvement in mood in the group given the sham drink [ 54 ].

SERT gene and gene-stress interactions

A possible link between depression and the repeat length polymorphism in the promoter region of the SERT gene (5-HTTLPR), specifically the presence of the short repeats version, which causes lower SERT mRNA expression, has been proposed [ 55 ]. Interestingly, lower levels of SERT would produce higher levels of synaptic serotonin. However, more recently, this hypothesis has been superseded by a focus on the interaction effect between this polymorphism, depression and stress, with the idea that the short version of the polymorphism may only give rise to depression in the presence of stressful life events [ 55 , 56 ]. Unlike other areas of serotonin research, numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of genetic studies have been conducted, and most recently a very large analysis based on a sample from two genetic databanks. Details of the five most recent studies that have addressed the association between the SERT gene and depression, and the interaction effect are detailed in Table 1 .

Although some earlier meta-analyses of case-control studies showed a statistically significant association between the 5-HTTLPR and depression in some ethnic groups [ 57 , 58 ], two recent large, high quality studies did not find an association between the SERT gene polymorphism and depression [ 27 , 32 ]. These two studies consist of by far the largest and most comprehensive study to date [ 32 ] and a high-quality meta-analysis that involved a consistent re-analysis of primary data across all conducted studies, including previously unpublished data, and other comprehensive quality checks [ 27 , 59 ] (see Table 1 ).

Similarly, early studies based on tens of thousands of participants suggested a statistically significant interaction between the SERT gene, forms of stress or maltreatment and depression [ 60 , 61 , 62 ], with a small odds ratio in the only study that reported this (1.18, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.28) [ 62 ]. However, the two recent large, high-quality studies did not find an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression (Border et al [ 32 ] and Culverhouse et al.) [ 27 ] (see Table 1 ).

Overall results

Table 3 presents the modified GRADE ratings for each study and the overall rating of the strength of evidence in each area. Areas of research that provided moderate or high certainty of evidence such as the studies of plasma serotonin and metabolites and the genetic and gene-stress interaction studies all showed no association between markers of serotonin activity and depression. Some other areas suggested findings consistent with increased serotonin activity, but evidence was of very low certainty, mainly due to small sample sizes and possible residual confounding by current or past antidepressant use. One area - the tryptophan depletion studies - showed very low certainty evidence of lowered serotonin activity or availability in a subgroup of volunteers with a family history of depression. This evidence was considered very low certainty as it derived from a subgroup of within-subject studies, numbers were small, and there was no information on medication use, which may have influenced results. Subsequent research has not confirmed an effect with numerous negative studies in volunteers.

Our comprehensive review of the major strands of research on serotonin shows there is no convincing evidence that depression is associated with, or caused by, lower serotonin concentrations or activity. Most studies found no evidence of reduced serotonin activity in people with depression compared to people without, and methods to reduce serotonin availability using tryptophan depletion do not consistently lower mood in volunteers. High quality, well-powered genetic studies effectively exclude an association between genotypes related to the serotonin system and depression, including a proposed interaction with stress. Weak evidence from some studies of serotonin 5-HT 1A receptors and levels of SERT points towards a possible association between increased serotonin activity and depression. However, these results are likely to be influenced by prior use of antidepressants and its effects on the serotonin system [ 30 , 31 ]. The effects of tryptophan depletion in some cross-over studies involving people with depression may also be mediated by antidepressants, although these are not consistently found [ 63 ].

The chemical imbalance theory of depression is still put forward by professionals [ 17 ], and the serotonin theory, in particular, has formed the basis of a considerable research effort over the last few decades [ 14 ]. The general public widely believes that depression has been convincingly demonstrated to be the result of serotonin or other chemical abnormalities [ 15 , 16 ], and this belief shapes how people understand their moods, leading to a pessimistic outlook on the outcome of depression and negative expectancies about the possibility of self-regulation of mood [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]. The idea that depression is the result of a chemical imbalance also influences decisions about whether to take or continue antidepressant medication and may discourage people from discontinuing treatment, potentially leading to lifelong dependence on these drugs [ 67 , 68 ].

As with all research synthesis, the findings of this umbrella review are dependent on the quality of the included studies, and susceptible to their limitations. Most of the included studies were rated as low quality on the AMSTAR-2, but the GRADE approach suggested some findings were reasonably robust. Most of the non-genetic studies did not reliably exclude the potential effects of previous antidepressant use and were based on relatively small numbers of participants. The genetic studies, in particular, illustrate the importance of methodological rigour and sample size. Whereas some earlier, lower quality, mostly smaller studies produced marginally positive findings, these were not confirmed in better-conducted, larger and more recent studies [ 27 , 32 ]. The identification of depression and assessment of confounders and interaction effects were limited by the data available in the original studies on which the included reviews and meta-analyses were based. Common methods such as the categorisation of continuous measures and application of linear models to non-linear data may have led to over-estimation or under-estimation of effects [ 69 , 70 ], including the interaction between stress and the SERT gene. The latest systematic review of tryptophan depletion studies was conducted in 2007, and there has been considerable research produced since then. Hence, we provided a snapshot of the most recent evidence at the time of writing, but this area requires an up to date, comprehensive data synthesis. However, the recent studies were consistent with the earlier meta-analysis with little evidence for an effect of tryptophan depletion on mood.

Although umbrella reviews typically restrict themselves to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we aimed to provide the most comprehensive possible overview. Therefore, we chose to include meta-analyses that did not involve a systematic review and a large genetic association study on the premise that these studies contribute important data on the question of whether the serotonin hypothesis of depression is supported. As a result, the AMSTAR-2 quality rating scale, designed to evaluate the quality of conventional systematic reviews, was not easily applicable to all studies and had to be modified or replaced in some cases.

One study in this review found that antidepressant use was associated with a reduction of plasma serotonin [ 26 ], and it is possible that the evidence for reductions in SERT density and 5-HT 1A receptors in some of the included imaging study reviews may reflect compensatory adaptations to serotonin-lowering effects of prior antidepressant use. Authors of one meta-analysis also highlighted evidence of 5-HIAA levels being reduced after long-term antidepressant treatment [ 71 ]. These findings suggest that in the long-term antidepressants might produce compensatory changes [ 72 ] that are opposite to their acute effects [ 73 , 74 ]. Lowered serotonin availability has also been demonstrated in animal studies following prolonged antidepressant administration [ 75 ]. Further research is required to clarify the effects of different drugs on neurochemical systems, including the serotonin system, especially during and after long-term use, as well as the physical and psychological consequences of such effects.

This review suggests that the huge research effort based on the serotonin hypothesis has not produced convincing evidence of a biochemical basis to depression. This is consistent with research on many other biological markers [ 21 ]. We suggest it is time to acknowledge that the serotonin theory of depression is not empirically substantiated.

Data availability

All extracted data is available in the paper and supplementary materials. Further information about the decision-making for each rating for categories of the AMSTAR-2 and STREGA are available on request.

Coppen A. The biochemistry of affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:1237–64.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. What Is Psychiatry? 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-psychiatry-menu .

GlaxoSmithKline. Paxil XR. 2009. www.Paxilcr.com (site no longer available). Last accessed 27th Jan 2009.

Eli Lilly. Prozac - How it works. 2006. www.prozac.com/how_prozac/how_it_works.jsp?reqNavId=2.2 . (site no longer available). Last accessed 10th Feb 2006.

Healy D. Serotonin and depression. BMJ: Br Med J. 2015;350:h1771.

Article Google Scholar

Pies R. Psychiatry’s New Brain-Mind and the Legend of the “Chemical Imbalance.” 2011. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatrys-new-brain-mind-and-legend-chemical-imbalance . Accessed March 2, 2021.

Geddes JR, Andreasen NC, Goodwin GM. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2020.

Book Google Scholar

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 10th Editi. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW); 2017.

Cowen PJ, Browning M. What has serotonin to do with depression? World Psychiatry. 2015;14:158–60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ. How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:409–18.

Yohn CN, Gergues MM, Samuels BA. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol Brain. 2017;10:28.

Hahn A, Haeusler D, Kraus C, Höflich AS, Kranz GS, Baldinger P, et al. Attenuated serotonin transporter association between dorsal raphe and ventral striatum in major depression. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:3857–66.

Amidfar M, Colic L, Kim MWAY-K. Biomarkers of major depression related to serotonin receptors. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2018;14:239–44.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Albert PR, Benkelfat C, Descarries L. The neurobiology of depression—revisiting the serotonin hypothesis. I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:2378–81.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pilkington PD, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. The Australian public’s beliefs about the causes of depression: associated factors and changes over 16 years. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:356–62.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. A disease like any other? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321–30.

Read J, Renton J, Harrop C, Geekie J, Dowrick C. A survey of UK general practitioners about depression, antidepressants and withdrawal: implementing the 2019 Public Health England report. Therapeutic Advances in. Psychopharmacology. 2020;10:204512532095012.

Google Scholar

Demasi M, Gøtzsche PC. Presentation of benefits and harms of antidepressants on websites: A cross-sectional study. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2020;31:53–65.

Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Kirsch I. Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder? BMJ Evidence-Based. Medicine. 2020;25:130–130.

Moncrieff J, Cohen D. Do antidepressants cure or create abnormal brain states? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e240.

Kennis M, Gerritsen L, van Dalen M, Williams A, Cuijpers P, Bockting C. Prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:321–38.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21:95–100.

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2,. version 6.Cochrane; 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Huang T, Balasubramanian R, Yao Y, Clish CB, Shadyab AH, Liu B, et al. Associations of depression status with plasma levels of candidate lipid and amino acid metabolites: a meta-analysis of individual data from three independent samples of US postmenopausal women. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00870-9 .

Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T, et al. Collaborative meta-analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:133–42.

Little J, Higgins JPT, Ioannidis JPA, Moher D, Gagnon F, von Elm E, et al. STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)— An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000022.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. What is quality of evidence and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8.

Yoon HS, Hattori K, Ogawa S, Sasayama D, Ota M, Teraishi T, et al. Relationships of cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels with clinical variables in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e947–56.

Kugaya A, Seneca NM, Snyder PJ, Williams SA, Malison RT, Baldwin RM, et al. Changes in human in vivo serotonin and dopamine transporter availabilities during chronic antidepressant administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:413–20.

Border R, Johnson EC, Evans LM, Smolen A, Berley N, Sullivan PF, et al. No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:376–87.

Ogawa S, Tsuchimine S, Kunugi H. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite concentrations in depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of historic evidence. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;105:137–46.

Nautiyal KM, Hen R. Serotonin receptors in depression: from A to B. F1000Res. 2017;6:123.

Rojas PS, Neira D, Muñoz M, Lavandero S, Fiedler JL. Serotonin (5‐HT) regulates neurite outgrowth through 5‐HT1A and 5‐HT7 receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92:1000–9.

Kaufman J, DeLorenzo C, Choudhury S, Parsey RV. The 5-HT1A receptor in Major Depressive Disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:397–410.

Nikolaus S, Müller H-W, Hautzel H. Different patterns of 5-HT receptor and transporter dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders – a comparative analysis of in vivo imaging findings. Rev Neurosci. 2016;27:27–59.

Wang L, Zhou C, Zhu D, Wang X, Fang L, Zhong J, et al. Serotonin-1A receptor alterations in depression: A meta-analysis of molecular imaging studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:1–9.

Kambeitz JP, Howes OD. The serotonin transporter in depression: Meta-analysis of in vivo and post mortem findings and implications for understanding and treating depression. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:358–66.

Meyer JH. Imaging the serotonin transporter during major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:86–102.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mathews TA, Fedele DE, Coppelli FM, Avila AM, Murphy DL, Andrews AM. Gene dose-dependent alterations in extraneuronal serotonin but not dopamine in mice with reduced serotonin transporter expression. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;140:169–81.

Shen H-W, Hagino Y, Kobayashi H, Shinohara-Tanaka K, Ikeda K, Yamamoto H, et al. Regional differences in extracellular dopamine and serotonin assessed by in vivo microdialysis in mice lacking dopamine and/or serotonin transporters. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1790–9.

Hagino Y, Takamatsu Y, Yamamoto H, Iwamura T, Murphy DL, Uhl GR, et al. Effects of MDMA on extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in mice lacking dopamine and/or serotonin transporters. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:91–5.

Zhou Z, Zhen J, Karpowich NK, Law CJ, Reith MEA, Wang D-N. Antidepressant specificity of serotonin transporter suggested by three LeuT-SSRI structures. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:652–7.

Gryglewski G, Lanzenberger R, Kranz GS, Cumming P. Meta-analysis of molecular imaging of serotonin transporters in major depression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1096–103.

Benmansour S, Owens WA, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Frazer A. Serotonin clearance in vivo is altered to a greater extent by antidepressant-induced downregulation of the serotonin transporter than by acute blockade of this transporter. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6766–72.

Benmansour S, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Gerhardt GA, Javors MA, Gould GG, et al. Effects of chronic antidepressant treatments on serotonin transporter function, density, and mRNA level. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10494–501.

Horschitz S, Hummerich R, Schloss P. Down-regulation of the rat serotonin transporter upon exposure to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2181–4.

Young SN. Acute tryptophan depletion in humans: a review of theoretical, practical and ethical aspects. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38:294–305.

Ruhe HG, Mason NS, Schene AH. Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: a meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:331–59.

Fusar-Poli P, Allen P, McGuire P, Placentino A, Cortesi M, Perez J. Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies of the effects of acute tryptophan depletion: A systematic review of the literature. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:131–43.

Hogenelst K, Schoevers RA, Kema IP, Sweep FCGJ, aan het Rot M. Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:111–20.

Weinstein JJ, Rogers BP, Taylor WD, Boyd BD, Cowan RL, Shelton KM, et al. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on raphé functional connectivity in depression. Psychiatry Res. 2015;234:164–71.

Moreno FA, Erickson RP, Garriock HA, Gelernter J, Mintz J, Oas-Terpstra J, et al. Association study of genotype by depressive response during tryptophan depletion in subjects recovered from major depression. Mol. Neuropsychiatry. 2015;1:165–74.

Munafò MR. The serotonin transporter gene and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:915–7.

Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003;301:386–9.

Kiyohara C, Yoshimasu K. Association between major depressive disorder and a functional polymorphism of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) transporter gene: A meta-analysis. Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20:49–58.

Oo KZ, Aung YK, Jenkins MA, Win AK. Associations of 5HTTLPR polymorphism with major depressive disorder and alcohol dependence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:842–57.

Culverhouse RC, Bowes L, Breslau N, Nurnberger JI, Burmeister M, Fergusson DM, et al. Protocol for a collaborative meta-analysis of 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:1–12.

Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:444.

Sharpley CF, Palanisamy SKA, Glyde NS, Dillingham PW, Agnew LL. An update on the interaction between the serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress and depression, plus an exploration of non-confirming findings. Behav Brain Res. 2014;273:89–105.

Bleys D, Luyten P, Soenens B, Claes S. Gene-environment interactions between stress and 5-HTTLPR in depression: A meta-analytic update. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:339–45.

Delgado PL. Monoamine depletion studies: implications for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:22–26.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kemp JJ, Lickel JJ, Deacon BJ. Effects of a chemical imbalance causal explanation on individuals’ perceptions of their depressive symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2014;56:47–52.

Lebowitz MS, Ahn W-K, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Fixable or fate? Perceptions of the biology of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:518.

Zimmermann M, Papa A. Causal explanations of depression and treatment credibility in adults with untreated depression: Examining attribution theory. Psychol Psychother. 2020;93:537–54.

Maund E, Dewar-Haggart R, Williams S, Bowers H, Geraghty AWA, Leydon G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to discontinuing antidepressant use: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:38–62.

Eveleigh R, Speckens A, van Weel C, Oude Voshaar R, Lucassen P. Patients’ attitudes to discontinuing not-indicated long-term antidepressant use: barriers and facilitators. Therapeutic Advances in. Psychopharmacology. 2019;9:204512531987234.

Harrell FE Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer, Cham; 2015.

Schafer JL, Kang J. Average causal effects from nonrandomized studies: a practical guide and simulated example. Psychol Methods. 2008;13:279–313.

Pech J, Forman J, Kessing LV, Knorr U. Poor evidence for putative abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid neurotransmitters in patients with depression versus healthy non-psychiatric individuals: A systematic review and meta-analyses of 23 studies. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:6–16.

Fava GA. May antidepressant drugs worsen the conditions they are supposed to treat? The clinical foundations of the oppositional model of tolerance. Therapeutic Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320970325.

Kitaichi Y, Inoue T, Nakagawa S, Boku S, Kakuta A, Izumi T, et al. Sertraline increases extracellular levels not only of serotonin, but also of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and striatum of rats. Eur J Pharm. 2010;647:90–6.

Gartside SE, Umbers V, Hajós M, Sharp T. Interaction between a selective 5‐HT1Areceptor antagonist and an SSRI in vivo: effects on 5‐HT cell firing and extracellular 5‐HT. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1064–70.

Bosker FJ, Tanke MAC, Jongsma ME, Cremers TIFH, Jagtman E, Pietersen CY, et al. Biochemical and behavioral effects of long-term citalopram administration and discontinuation in rats: role of serotonin synthesis. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:948–57.

Download references

There was no specific funding for this review. MAH is supported by a Clinical Research Fellowship from North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT). This funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK

Joanna Moncrieff & Mark A. Horowitz

Research and Development Department, Goodmayes Hospital, North East London NHS Foundation Trust, Essex, UK

Faculty of Education, Health and Human Sciences, University of Greenwich, London, UK

Ruth E. Cooper

Psychiatry-UK, Cornwall, UK

Tom Stockmann

Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Simone Amendola

Department of Applied Psychology, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Zurich, Switzerland

Michael P. Hengartner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JM conceived the idea for the study. JM, MAH, MPH, TS and SA designed the study. JM, MAH, MPH, TS, and SA screened articles and abstracted data. JM drafted the first version of the manuscript. JM, MAH, MPH, TS, SA, and REC contributed to the manuscript’s revision and interpretation of findings. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joanna Moncrieff .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author). SA declares no conflicts of interest. MAH reports being co-founder of a company in April 2022, aiming to help people safely stop antidepressants in Canada. MPH reports royalties from Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK for his book published in December, 2021, called “Evidence-biased Antidepressant Prescription.” JM receives royalties for books about psychiatric drugs, reports grants from the National Institute of Health Research outside the submitted work, that she is co-chairperson of the Critical Psychiatry Network (an informal group of psychiatrists) and a board member of the unfunded organisation, the Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry. Both are unpaid positions. TS is co-chairperson of the Critical Psychiatry Network. RC is an unpaid board member of the International Institute for Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry 28 , 3243–3256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Download citation

Received : 21 June 2021

Revised : 31 May 2022

Accepted : 07 June 2022

Published : 20 July 2022

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Association between junk food consumption and mental health problems in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Hanieh-Sadat Ejtahed

- Parham Mardi

- Mostafa Qorbani

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

The involvement of serotonin in major depression: nescience in disguise?

- Danilo Arnone

- Catherine J. Harmer

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

- Chloe E. Page

- C. Neill Epperson

- Scott M. Thompson

Serotonin effects on human iPSC-derived neural cell functions: from mitochondria to depression

- Iseline Cardon

- Sonja Grobecker

- Christian H. Wetzel

Neither serotonin disorder is at the core of depression nor dopamine at the core of schizophrenia; still these are biologically based mental disorders

- Konstantinos N. Fountoulakis

- Eva Maria Tsapakis

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Call to +1 844 889-9952

Literature Review on Depression

| 📄 Words: | 2255 |

|---|---|

| 📝 Subject: | |

| 📑 Pages: | 8 |

| 📚 Topics: | , , |

Depression alters one’s mood, making one feel sad and lose interest in people, events, and objects, and thus may cause physical and emotional problems. It may involve treatment in the long run if it persists, which includes medication and psychotherapy. This paper will focus on a detailed summary of other researchers’ work addressing the issue of depression using several databases and carry out a curative study on depression in full text. The following literature review is based on selected articles meeting the criteria of inclusion.

According to Lim et al. (2018), depression in the general population is a common mental health condition. It is highly associated with sadness, low self-esteem, poor concentration, anxiety, interest loss, and a feeling of being a quilt. The study also shows that the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted that depression will be ranked as the second global disease burden by 2020. The research also covered the nomothetic and idiographic measures of depression, which means that the assessed item is common to every person at different degree levels. In contrast, the idiographic measure is based on the distinct features and views of the patient. The study concludes that during the patient assessment on the defined objective of treatment, idiographic measures are preferred due to being more relevant.

An investigation done by Bernaras et al. (2019) states that depression is the main cause of disability-related illness in the world. The research focused on depression among children and adolescents since these two groups are agilely associated with high incidence. It also analyses the theories that construct and explain depression and provides an overview of disorders among children and adolescents. In this study, the authors conclude that depression in terms of the mental distinction between adults and children has no difference, and thus, the theory of explanation is highly taken into account to elaborate a better understanding of depression. The research further stated that treatment and prevention should be multifactorial (Bernaras et al., 2019). Besides, it is estimated that universal programs can be more efficient considering their wide application. The research results are limited in providing a good conclusion and fail to demonstrate any solid long-term efficacy.

Bernaras et al.(2019) in their examination found that biological factors such as tryptophan have a strong influence on the appearance of a depressive disorder. The increase seen in the prevalence of depression is explained by having negative interpersonal relations and the relationship with one’s surroundings accompanied by social-cultural changes. Additionally, the authors conclude that many instruments can be applied in elevating depression, but it is more important to have a continued test to diagnose the condition at the early stages. Regarding the prevention programs, the study suggested that they should be implemented at early initial ages, and finally, most depression treatments are more rigorous and effective.

Additionally, Health Quality Ontario (2017) suggests that the most diagnosed disorders in Canada on depression are major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders that are mostly associated with high disorders and economic hardship. It is important to note that the treatment of the two conditions is known to include pharmacological and psychological preventions. The highly used psychological interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive therapy, and interpersonal therapy.

The study supports the fact that depression is the world’s second-largest health problem based on illness-induced disability. The three most used psychotherapeutic treatments which are well explained in this research include CBT, interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy. CBT focuses on helping patients understand how automated thoughts on beliefs, expectations, and attitudes have a major contribution to anxiety and sadness. Interpersonal therapy aims to identify and solve problems through the establishment and maintenance of a satisfying relationship. Lastly, supportive therapy is an unstructured approach that relies on the basic interpersonal skills of the therapist.

Research conducted by Lu (2019) on adolescent depression on the topic of national trends, health care disparities, and risk factors shows that in the US, depression is a major cause of suicide among adolescents in aged between 10 and 19. Suicide is marked as the third major cause of death in the US, and research reflects that depression is the major factor in these cases. According to Lu (2019), depression is mostly underdiagnosed among adolescents, although mental health treatment is available. Lu (2019) states that if depression is not treated at the early age of an adolescent, it can have substantial negative effects on health and social results in late adolescence and adulthood.

Findings from the study revealed a growing number of untreated adolescents with major depression from 2011 to 2016 from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data. The research outcomes highlighted some of the major causes of depression among young people. Such factors include some sociodemographic, school, and family parameters, and the underutilization of mental health services. The study findings also highlight the importance of family and school in the treatment of depression. Finally, it was proved that adolescents with less family attention were more vulnerable to depression and less likely to receive mental and medical treatment.

The treatment of depression among adults in the United has been covered by a study done by Olfson et al. (2016). Based on the national survey conducted from 2001 to 2003, it was approximated that 49.5 percent of adults with a history of depression had not received any treatment, and about 48.4 percent had not received mental treatment over the past year (Olfson et al., 2016). According to the study, the US Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended adult screening on depression and a follow-up on the treatment that should be provided through a clinical setting arrangement.

The study findings showed that although there is the increased use of antidepressants, there still exists a gap in the treatment of depression. The number of adults who received screening for depression did not receive treatment that year. The research also showed that there was a low hood on receiving treatment to racial /ethnic minority groups. Regarding the application of antidepressants, the patient who had less serious depression had a high likelihood of receiving antidepressants than seriously depressed patients.

Antipsychotics, anxiolytics and mood stabilizers were mostly used to treat patients with higher than lower degrees of distress. Olfson et al. (2016) stated that this type of medication was mostly kept to treat patients with more complicated and resistant to treatment conditions. Antipsychotic treatment is suitable for patients with resistance to the use of antidepressants. Anxiolytics largely aid in managing anxiety problems that do not respond to the use of antidepressants. Finally, mood stabilizers help in the adjustment of agitations related to depression.

Research by Stark et al. (2018) on the issue of depression perspective in older primary care patients, treatment, and depression management opportunities showed that depression in old age is very common and has health-related consequences on the elderly. Research findings showed that symptoms like sadness and withdrawal are associated with older people. The consequences of depression can lead to death through suicide, social isolation, loss of family and work, and low esteem. The causes of the condition, as stated by Stark et al. (2018), are classified based on changing life events and internal factors.

According to Stark et al. (2018), depression does not only occur at young age people but is also a threat to older people. In age-related causes, the increased incidence of deaths among relatives can cause loneliness and boredom. Treatment of depression among older adults is possible. The main obstacles to the successful recovery from depression among the elderly, according to research, include beliefs on there is no treatment for depression among older people as well as fear of stigmatization. Similarly, it is believed that people should only care about their problems.

Research on adolescent depression, in particular, the one conducted by Lu (2019), has greatly contributed to literature work. Vrijen et al. (2016) have concentrated their research on predicting depression through the slow identification of facial happiness during early adolescent stages. As seen from previous research, depression remains a major concern in mental health problems. The study proved how facial emotions in the early ages of depression could predict depressive disorders and symptoms.

Research findings suggested that facial emotion identification prejudice may be a symptom corresponding trait marker for depressive disorder and anhedonia. The associations were found only based on multi-emotional models. The study found that individuals who portray sadness in comparison to happy ones are more likely to develop depression or anhedonia symptoms. The emotion identification effects on depressive disorders are mainly seen as carried by the symptoms of anhedonia but not symptoms of sadness. There is a relationship between symptoms of anhedonia and facial emotion identification (Vrijen et al., 2016). On the elimination of adolescents, the research findings were stronger on the predictive value on the identification of facial reactions for individuals with depressive disorders related to anhedonia and despair and may inversely be connected with facial identification of emotions.

Furthermore, depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients showed that the features are very common in people with mental disorders and gave a considerable number of effects on patient quality of health. The results of previous studies vary from the consideration presented in the research by Wang et al. (2017). In this study, it was found that the number of outpatients from otolaryngology clinics was higher, marking 53.0 %. The research also highlighted that depression was a mediator among conditions in otolaryngology.

The outcomes also have shown that there is a psychoneuroimmunology link between medical illness and depression. Besides, stroke burdens were found to cause depression among patients and their caregivers. For patience with stroke, it was found that novel rehabilitation interventions might reduce depression. A medical professional often overlooks depression or depressive symptoms due to not having been offered specific mental health training. In this research, it was found that outpatients between the age of 30 and 40 had related depression prevalence as compared to outpatients between the age of 80 and 90 years old. The result contradicts research done by Benaras et al. (2019) on depression among children and adolescents, which focused on the rise of the incidence of suicide cases caused by depression. Yang’s study showed that depression levels declined with age. The author presents different results as he stresses that there was no pattern on depression centering his argument on age.

Depression has been a global problem that has raised concerns among employees and employers. According to McCart and Nesbit (2020), the number of days of absenteeism in jobs results from depression is higher than those related to diseases like heart attack and hypertension all put together. According to the study, billions of dollars are spent on medical care, mortality due to suicide, and the loss of productivity as a result of depression. McCart and Nesbit (2020) have discussed a connection between disorders caused by depression and such chronic conditions as the unemployment period and the total income.

In the employment setting, research has shown that some reasons make it difficult to diagnose depression. In the workplace, employees can avoid diagnosis because of the lack of skills by physicians, stigma, unavailability of treatment and providers, restrictions on drugs, psychotherapeutic care, and limitations due to third-party coverage. The study results from most organizations lack a way of huddling the employee’s depression. Education institutions were found to be having programs that help depressed personnel. Other organizations stated that depression is a personal issue, and unless an employee asks for help, the services are not openly offered.

Among pregnant women, depression has been found to affect both the mother and the unborn child. Looking at both depression and anxiety during the period of antenatal and post-natal, there is a notable effect of depression among these groups. According to Smith et al. (2019), there is a preference in pregnant women for non-pharmacological treatment options; instead, they prefer the use of therapies and complementary medicines to manage the symptoms.

Martínez-Paredes and Jácome-Pérez (2019) conducted a similar study on depression among pregnant women, which confirmed that depression in this group is common psychiatric mobility. Diagnosis of depression is based on guidelines by the DSM-5 to validate scales like the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. According to medical professionals, the research also shows negative effects on the treatment, diagnosis, and recognition of the fetus. The study concluded that depression is a common condition among pregnant women, though it is underlooked as its symptoms are linked to pregnancy.

Several personal and mental effects are caused by depression among patients of total knee arthroplasty. Findings of the research have indicated that patients with higher education levels have less depression and are happier before surgery. Results have also illustrated that people with depression and anxiety were found to improve at a low rate than other groups. It also stated that patients with greater health were seen to have a considerable improvement in mental health. The conclusion of the research showed that the main determinant of physical, mental, and functional outcomes was depression.

Depression remains to be among the top five illnesses in the world, and research works have reflected that age does not matter, with everyone being at risk of developing the condition. In most studies, it is indicated as the main cause of suicide and death among children and adolescents. There are ways to help individuals suffering from despair such as the use of antidepressants among people with low depression levels. Likewise, early detection and treatment of the disorder can help individuals in their late adolescent stages and adulthood. Families can offer their support instead of contributing and worsening this condition.

Bernaras, E., Jaureguizar, J., & Garaigordobil, M. (2019). Child and adolescent depression: A review of theories, evaluation instruments, prevention programs, and treatments . Frontiers in Psychology, 10 (543), 1-24. Web.

Health Quality Ontario. (2017). Psychotherapy for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: A health technology assessment. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, 17 (15), 1-167.

Lim, G. Y., Tam, W. W., Lu, Y., Ho, C. S., Zhang, M. W., & Ho, R. C. (2018). Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014 . Scientific reports , 8 (1), 1-10. Web.

Lu, W. (2019). Adolescent depression: National trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities . American Journal of Health Behavior, 43 (1), 181-194. Web.

McCart A, & Nesbit, J. (2020). S trategies to support employees with depression: Applying the Centers for Disease Control health scorecard . Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 9 (5), 1-4. Web.

Martínez-Paredes, J. F., & Jácome-Pérez, N. (2019). Depression in pregnancy . Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría (English ed.) , 48 (1), 58-65. Web.

Moghtadaei, M., Yeganeh, A., Hosseinzadeh, N., Khazanchin, A., Moaiedfar, M., Jolfaei, A. G., & Nasiri, S. (2020). The Impact of depression, personality, and mental health on outcomes of total knee arthroplasty . Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery, 12 (4), 456-463. Web.

Olfson, M., Blanco, C., & Marcus, S. C. (2016). Treatment of adult depression in the United States . JAMA Internal Medicine, 176 (10), 1482-1491. Web.

Smith, C. A., Shewamene, Z., Galbally, M., Schmied, V., & Dahlen, H. (2019). The effect of complementary medicines and therapies on maternal anxiety and depression in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis . Journal of Affective Disorders , 245 , 428-439. Web.

Stark, A., Kaduszkiewicz, H., Stein, J., Maier, W., Heser, K., Weyerer, S., Werle, J., Wiese, B., Mamone, S., König, H., & Bock, J. O. (2018). A qualitative study on older primary care patients’ perspectives on depression and its treatments-potential barriers to and opportunities for managing depression . BMC Family Practice, 19 (1), 1-10. Web.

Vrijen, C., Hartman, C. A., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2016). Slow identification of facial happiness in early adolescence predicts the onset of depression during eight years of follow-up. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25 (11), 1255-1266. Web.

Wang, J., Wu, X., Lai, W., Long, E., Zhang, X., Li, W.,… & Wang, D. (2017). Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among outpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis . BMJ Open , 7 (8). Web.

Cite this paper

Select style

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

PsychologyWriting. (2024, January 24). Literature Review on Depression. https://psychologywriting.com/literature-review-on-depression/

"Literature Review on Depression." PsychologyWriting , 24 Jan. 2024, psychologywriting.com/literature-review-on-depression/.

PsychologyWriting . (2024) 'Literature Review on Depression'. 24 January.

PsychologyWriting . 2024. "Literature Review on Depression." January 24, 2024. https://psychologywriting.com/literature-review-on-depression/.

1. PsychologyWriting . "Literature Review on Depression." January 24, 2024. https://psychologywriting.com/literature-review-on-depression/.

Bibliography

PsychologyWriting . "Literature Review on Depression." January 24, 2024. https://psychologywriting.com/literature-review-on-depression/.

#Depression: Findings from a Literature Review of 10 Years of Social Media and Depression Research

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- University of Pittsburgh

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- FUTURE GENER COMP SY

- Henrique S. Silva

- Laura A. Stockdale

- Lect Notes Comput Sci

- Christopher C. Frye

- Julissa Murrieta

- Lucia Lushi Chen

- Christopher H. K. Cheng

- CLIN SOC WORK J

- Gretchen Anstadt

- Bryan Casselman

- Kamala Ganesh

- NEW MEDIA SOC

- Jennifer Park

- Jada Hallman

- Jeff Hancock

- Pinar Ozturk

- Andrea Forte

- Kristen Purcell

- Clive E Adams

- MED CARE RES REV

- Marilyn F Downs

- Ezra Golberstein

- FIELD METHOD

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Contributing studies for clinically elevated depression symptoms are presented in order of largest to smallest prevalence rate. Square data markers represent prevalence rates, with lines around the marker indicating 95% CIs. The diamond data marker represents the overall effect size based on included studies.

Contributing studies for clinically elevated anxiety symptoms are presented in order of largest to smallest prevalence rate. Square data markers represent prevalence rates, with lines around the marker indicating 95% CIs. The diamond data marker represents the overall effect size based on included studies.

eTable 1. Example Search Strategy from Medline

eTable 2. Study Quality Evaluation Criteria

eTable 3. Quality Assessment of Studies Included

eTable 4. Sensitivity analysis excluding low quality studies (score=2) for moderators of the prevalence of clinically elevated depressive symptoms in children and adolescence during COVID-19

eTable 5. Sensitivity analysis excluding low quality studies (score=2) for moderators of the prevalence of clinically elevated anxiety symptoms in children and adolescence during COVID-19

eFigure 1. PRISMA diagram of review search strategy

eFigure 2. Funnel plot for studies included in the clinically elevated depressive symptoms

eFigure 3. Funnel plot for studies included in the clinically elevated anxiety symptoms

- Pediatric Depression and Anxiety Doubled During the Pandemic JAMA News From the JAMA Network October 5, 2021 Anita Slomski

- Guidelines Synopsis: Screening for Anxiety in Adolescent and Adult Women JAMA JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis March 8, 2022 This JAMA Clinical Guidelines Synopsis summarizes the 2020 Women’s Preventive Services Initiative recommendation on screening for anxiety in adolescent and adult women. Tiffany I. Leung, MD, MPH; Adam S. Cifu, MD; Wei Wei Lee, MD, MPH

- Addressing the Global Crisis of Child and Adolescent Mental Health JAMA Pediatrics Editorial November 1, 2021 Tami D. Benton, MD; Rhonda C. Boyd, PhD; Wanjikũ F.M. Njoroge, MD

- Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on Adolescents With Eating Disorders JAMA Pediatrics Comment & Response February 1, 2022 Thonmoy Dey, BSc; Zachariah John Mansell, BSc; Jasmin Ranu, BSc

See More About

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Others Also Liked

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

- CME & MOC

Racine N , McArthur BA , Cooke JE , Eirich R , Zhu J , Madigan S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19 : A Meta-analysis . JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–1150. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Manage citations:

© 2024