Who Said ‘Dulce et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori’?

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Let’s begin this week with a nice straightforward poetry question. Which poet gave us the quotation, ‘dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’?

The war poet Wilfred Owen has made these words resonate with new meaning in the last century or so, but we owe the line to a much older, very different poet.

A Summary and Analysis of Ray Bradbury’s ‘Zero Hour’

‘Zero Hour’ is a 1949 short story by the American author Ray Bradbury (1920-2012), included in his 1953 collection The Illustrated Man . In the story, which is set in a future America, a young girl is befriended by an alien who needs her help to invade Earth and kill the adults.

You can read ‘Zero Hour’ here before proceeding to our summary and analysis of Bradbury’s story below. The story takes around fifteen minutes to read.

‘To Strive, to Seek, to Find, and Not to Yield’: Tennyson’s Ulysses

The line ‘to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield’, with its quartet of infinitives, is one of Tennyson’s most memorable quotations. The line concludes one of his finest dramatic monologues (a literary mode Tennyson, along with his fellow Victorian poet Robert Browning, did much to invent and develop), ‘Ulysses’.

A Summary and Analysis of ‘The Story of the Late Mr Elvesham’ by H. G. Wells

‘The Story of the Late Mr Elvesham’ was first published in May 1896 in the Idler magazine. It’s one of the best stories of H. G. Wells (1866-1946), who left behind dozens of classic short tales which laid the foundations for modern science fiction.

A Summary and Analysis of E. E. Cummings’ ‘In Spite of Everything’

‘In Spite of Everything’ (or, as the poet himself has it, without capitals, ‘in spite of everything’) is a short lyric poem by the American modernist poet E. E. Cummings (or, as he would himself have it, e. e. cummings). Cummings (1894-1962) was an innovative and distinctive poet famed for his lack of capital letters in his poetry and his idiosyncratic approach to punctuation.

The “Girl’s Girls” Have Lost The Plot

Everyone is rushing to prove they support women unconditionally — and accuse others of falling short.

Burgundy Chrome Nails Are The Coolest Fall Mani Trend

Your November Money Horoscope

Blair Waldorf Basically Invented All Of 2024’s Biggest Trends

How To Throw A Tasteful Adult Tantrum

Here's Your Horoscope For Saturday, November 2

Camila Cabello Dressed As Regina George & She Was, Like, Really Pretty

Babe, Wake Up — Emily Ratajkowski Went As Jennifer Lopez For Halloween

Whoops, Did He Forget To Mention He's A Republican?

“Pilates Princess” Makeup Is Trending & It’s So Pretty

Caroline Stanbury & Chanel Ayan Know How To Get Under Your Skin

Tamra Judge Doesn’t Have Any Regrets

Scheana Shay Doesn’t Care If You Don’t Like Her

Lisa Vanderpump Is Still Not Over This Staged Storyline

Chelsea Lazkani Isn't Holding Back

The Selling Sunset star gets candid about Season 8’s emotional roller coaster.

Porsha Williams Swears By This $7 Shampoo

Tate McRae Covers Her Body In This $58 Glitter Oil Before Each Concert

Paige Lorenze Is Defining #Tenniscore Glam

Meredith Duxbury Is In Her Soft-Girl Makeup Era

Sivan Ayla’s Secret To Looking Sun-Kissed Year Round

The influencer and founder shares the secrets to her Cali-girl aesthetic.

At 28, Molly Shannon Nearly Gave It All Up

At 28, Kathryn Hahn Made A Life-Changing Decision

At 28, Molly Sims Was Gearing Up To Wear A $30 Million Diamond Bikini

At 28, Kelly Rutherford Splurged On Her First Hermès Bag

At 28, Jane Lynch Began Letting Go Of Her Fears

In her late 20s, she could’ve taken a lesson from her Only Murders character, Sazz Pataki.

Scarlett Johansson Has A Hack For The Perfect Cappuccino

Alison Roman Doesn't Mind If You Order Takeout

Jordan Chiles Is A Girl’s Girl Who Thinks Women Deserve More

Morgan Riddle Shares The “Gross” Airplane Habit She Can’t Get On Board With

Cass DiMicco Has A Hack For Crushing Early Morning Pilates Classes

The OG fashion influencer now runs an accessories brand beloved by Hailey Bieber and Kendall Jenner.

Bustle Originals

Florence Pugh & Andrew Garfield Are Done Wasting Time

The stars of We Live in Time say making their new A24 tearjerker made them rethink everything: “It definitely gave me the kick up the ass.”

Jonathan Daviss Doesn’t Stop Moving

As Outer Banks returns for Season 4, Netflix’s YA juggernaut is served by, and serving, the dogged actor.

Harry Lawtey Is All Heart

The star of Industry and Joker: Folie à Deux takes love stories seriously — even the f*cked up ones.

Shailene Woodley Lives For Pleasure

In Three Women , the actor digs into the mess of sex and gender in America. Off the clock? She’s touching grass.

Stassi Schroeder Is So Over Secrets

The former Vanderpump Rules star spent her 20s baring all for Bravo. Now, in her new book, she’s sharing the struggles the cameras didn’t see — and plotting her return to reality TV.

Kristin Cavallari Hopes She’s Not Famous Forever

The Uncommon James founder and erstwhile reality TV star is already planning her exit from public life.

The Private World Of Kerry Washington

Her characters are famous for handling messy situations, often through sheer force of will. Can that approach succeed in real life?

How To Get Laid, According To Luann De Lesseps

The Countess is one of the great daters of reality television. Can she help us through the sex recession?

Miranda Cosgrove’s Almost Normal Life

Filming a destination rom-com gifted the actor a bit of real-life escapism from heartbreak at home.

Paapa Essiedu Is A Classically Trained Charmer

In The Effect — Essiedu’s buzziest role since I May Destroy You — the British actor brought Shakespearean precision to a very messy romance.

Justin H. Min, Reluctant Hollywood Heartthrob

In The Greatest Hits , he plays a classic romantic lead for the first time. He has some thoughts about that.

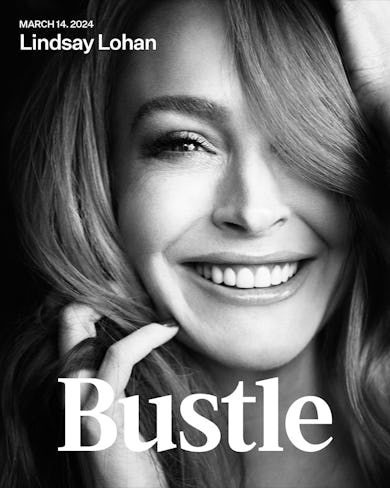

Lindsay’s Glorious Return

Lindsay Lohan is back. She’s bringing the peace she’s found — abroad and in marriage and motherhood — with her.

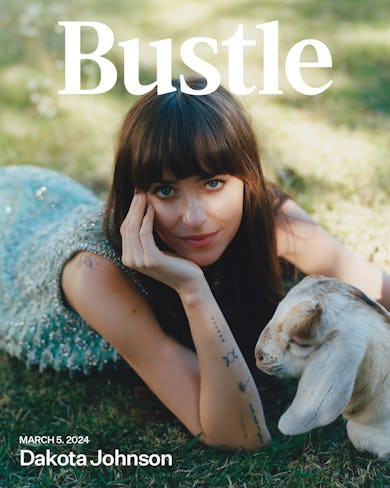

Dakota Johnson Can’t Fake It

On set, at junkets and in her relationships, the actor — and literary tastemaker with a new book club — favors blunt truths. And the occasional mischievous fib.

Are We Finally Ready For Diablo Cody?

With the release of Lisa Frankenstein — and the resuscitation of Jennifer’s Body — it seems culture has caught up to the audacious screenwriter.

Her Boss Got #MeToo’d. She’s Still With Him.

Melissa DeRosa was one of the most influential millennials in politics until her boss Andrew Cuomo was felled by sexual harassment allegations. Can she make a comeback without renouncing him?

Jake Johnson Is In A Long-Term Relationship With His Fans

The New Girl star’s directorial debut, comedy-thriller Self Reliance , pays homage to the will-they-won’t-they romance that made him famous.

Entertainment

The 'Golden Bachelor' Effect

When it comes to on-screen romance, Hollywood is having a real senior moment. Will viewers tune in?

There’s A Reason Why You Love Doomed Romance

Celebrity News

Paris Hilton Exposed Her Cleavage In A Britney Spears Halloween Costume

Hailey Bieber’s Red Halloween Hair Was Pure Fire

Kendall & Kylie Jenner Recreated An Iconic 'Lizzie McGuire' Scene For Halloween

Ashley Tisdale’s Brunette Shag & ’70s-Style Wispy Bangs Are A Vibe

Shawn Mendes Addresses Pregnancy Scare Lyrics In His New Song

In partnership with the United States Olympic & Paralympic Committee, Bustle editors are reporting live from the city of lights.

Getting Ready With Ubah Hassan For New York City’s Angel Ball

The RHONY star takes Bustle along for the prestigious event.

Ariana Grande Gave Bridal Vibes In A Sheer White Bustier Gown

Bella Hadid Wore Tighty-Whities As Pants With This “Ugly” Shoe Trend

Heidi Klum’s Wildest Halloween Costumes Of All Time

Celebrity Style

Heidi Klum Just Won Halloween 2024 With Her Costume

Sabrina Carpenter Made Spooky SZN Spicy In 4 Cheeky Costumes

Finally on screen together, Florence Pugh and Andrew Garfield say their new A24 tearjerker made them rethink everything: “It definitely gave me the kick up the ass.”

Dolly Parton Is Just A Girl

The superstar chats with Bustle about her makeup line and her earliest beauty memory.

Frosted Brows, Plum Pouts, & More Of Winter’s Biggest Makeup Trends

This $5 TRESemmé Hairspray Is A Must For The Perfect Slicked-Back Bun

Pamela Anderson Wants You To Have Makeup-Free Dinner Parties

Beauty News

15 Beauty Launches Our Editors Loved This Month

Some conservative men are downplaying their political views for the sake of their love lives.

According To TikTok, Making Out Is Even Hotter Than Sex

The Pros & Cons Of Sleeping Naked

TikTok’s “First Love Theory” Might Explain Why You’re Not Over Your Ex

Mental Health

How To Feel Less Tired On Mondays, According To Therapists

The Viral "October Theory" Will Change How You See Fall

How Tay & Taylor Lautner Brush Off The Haters

“Email Apnea” Might Be Why You Feel So Stressed Out At Work

Libras Need To Try These 3 Self-Care Tips

With exclusive celebrity interviews, the best new beauty trends, and earth shattering relationship advice, our award-winning daily newsletter has everything you need to sound like a person who’s on TikTok, even if you aren’t.

In The Clerb, We All Diet Coke Fam

It isn’t just a soda. It’s a way of life.

I Love My Friends. I Ignore Their Texts Anyway.

Here's Your November Horoscope

TikToker Delaney Rowe Doesn’t Mind A DM Slide

Here’s The Type Of Influencer You Should Be, Based On Your Zodiac Sign

I Woke Up In Stars Hollow For A Week With My Hatch Alarm Clock

Your Comprehensive Fall 2024 Shopping Guide

Flattering Outfits Under $35 That Are So Hot Right Now

Cute clothes you’ll want to wear all the time that won’t break the bank.

Her Halloween costume was so plastic. Cold, shiny, hard plastic.

In her nakedest look, no less.

Think pink.

She was completely unrecognizable.

That’s hot.

Oh, she made quite an impression.

Beyoncé Dressed As Rock Icon Betty Davis For Halloween

Some fans are speculating about the costume’s hidden meaning.

PSA: Kylie Jenner Recreated Demi Moore’s Striptease Bikini Look

A new Halloween queen entered the chat.

She dressed up as an iconic early 2000s cartoon character.

COMMENTS

George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984, presents a terrifying vision of a future society ruled by a totalitarian government that seeks to control every aspect of its citizens’ lives. Throughout the novel, Orwell employs various symbols to convey the themes of rebellion and hope. One …

Nineteen Eighty-Four (also published as 1984) is a dystopian novel and cautionary tale by English writer Eric Arthur Blair, who wrote under the pen name George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and final book completed in his lifetime. Thematically, it centres on the consequences of totalitarianism, mass surveillance, and repressive regimentation of people and behaviours within society. Orwell, a staunch believer in democratic socialism and m…

Nineteen Eighty-Four: plot summary. In the year 1984, Britain has been renamed Airstrip One and is a province of Oceania, a vast totalitarian superstate ruled by ‘the Party’, …

State-Ranking Common Module Essay Response. George Orwell’s 1949 Swiftian satire Nineteen Eighty-Four invites us to appreciate the intricate nature of humanity by representing how the …

In his essay “ 1984: Enigmas of Power,” Irving Howe writes, “There can be no ‘free space’ in the lives of the Outer Party faithful, nothing that remains beyond the command of the …

Quick answer: The quotation on the last page of George Orwell's 1984 in which it says "he had won the victory over himself" is highly ironic. He has won no victory except in the …

Through 1984, Orwell, delves deeply into the consequences of absolute societal control, effectively illustrating how totalitarian regimes manipulate collective experiences, such as the …

From its first page to its very last line, 1984 was hurtling the narrative towards the inevitable, heartbreaking conclusion: When the rats come chomping, we are all capable of …