Technology and Digital Media in the Classroom: A Guide for Educators

- January 23, 2020

Technology has done more to change school curriculum and practices than nearly anything else—and in such a short amount of time! While it can be hard to keep up with every trend in educational technology, the mindset you have when it comes to classroom tech matters just as much as which ones you use. By learning to view it as a means of enhancing your lessons and resources, you can provide your students with tools and opportunities they may not otherwise access.

So, why and how should you use technology in your classroom? Read on to discover the impact of technology in education and how to get the most from its unique benefits.

What Is the Proper Role of Technology in the Classroom?

If you struggle to use technology in your classroom, you’re not alone. Many educators aren’t motivated to use digital resources in class, often because they’re unsure how to use them effectively or are unaware of the benefits.[1] In such cases, it’s easy to question not only how to make technology useful, but also whether technology should be used in schools at all.

Even with the latest and best digital technology, classrooms will not benefit unless the students and faculty understand how to use it.[15] In fact, educational technology should never be viewed as a perfect resource to teach your students everything they need to know to succeed. Instead, view it as a tool that can inform and supplement lessons, and even then, only if teachers and administrators are well trained in its use.

While technology can be an excellent resource in a classroom, it’s important to set limitations. Technology—no matter how good—should never be a substitute for face-to-face interaction with a teacher or classmates.[4] Technology is best used to augment non-digital lessons rather than the other way around. The goal when using technology should be to enhance your teaching rather than replace it.[6]

Benefits of Using Tech and Digital Media in Education

With the help of technology, you can introduce your classroom to opportunities and resources they may not otherwise be able to access.[5] In fact, this is one of the greatest ways technology has changed education. You may not be able to take your students to one of NASA’s space centers to witness a rocket launch, for example, but you can teach them all about rockets using resources on NASA’s website . Video clips, educational games, and virtual simulations are just a few examples of technology resources you can use to engage and educate in the classroom.

Plus, the vast majority of today’s careers require at least some digital skills (which include anything from complex skills like coding to simpler ones like composing and sending emails). Using tech in class can prepare students to successfully enter the workforce after graduation.[4] Even though the technology is likely to change from their early school years to the time they start their first career, teaching digital literacy in elementary school is a great way to get students started.

Why else is understanding how to use technology in the classroom important? Using technology alongside non-digital lessons can have many academic and behavioral benefits for your students, including:[2,7,11,12]

- Longer attention span

- Increased intrinsic motivation to learn

- Higher classroom participation and student engagement

- Greater academic achievement

- Stronger digital literacy

And finally, the benefits of classroom technology can expand far beyond the classroom and right into your students’ homes.[4] Rather than handing out paper worksheets, you can send your students online lessons or activities to complete at their own convenience. This practice provides better flexibility, plus the opportunity for you to provide audio or video clips alongside homework assignments. Additionally, if you have under-resourced students in your classroom, you may be able to supplement the resources available to their families by providing take-home technology.

How to Get the Most from Technology in Schools

One of the major concerns parents and educators have with classroom technology is how to limit excessive screen time. The American Association of Pediatrics suggests the following screen time recommendations by age. Keep these guidelines in mind when you teach lessons that involve screen time in your classroom:[17]

- 2–5 years old : No more than one hour of high-quality digital activities or programming

- 6 or older : Consistent limits to prevent screen time getting in the way of sleep, physical activity, or other healthy behaviors

Whenever possible, prioritize active digital screen time over passive.[16] Active screen time, like playing an educational game or learning a new digital skill, engages a student’s mind or body in a way that involves more than observation. Passive screen time—think watching a video or listening to an online lecture—involves limited interaction or engagement with the technology. Active digital activities are more likely to help your students experience new concepts, and they encourage your class to work together during the lesson.

Although teachers at under-resourced and rural schools are less likely to use technology, any tech you have available can greatly add to the opportunities you provide your students.[13, 18] Technology can remove some of the physical or financial barriers to educational resources and experiences.[17] If you’re unable to go on a field trip, for example, you can access plenty of virtual field trips at no cost.[16] Use the technology you do have to supplement your lessons and provide students with information you may not otherwise be able to access.

And finally, use school technology to teach your students digital citizenship .[14] Broadly defined, digital citizenship is the safe, ethical, informed, and responsible use of technology.[16] It encompasses skills like internet safety, setting healthy screen time habits, and communicating with others online. Lessons that involve digital citizenship can help a student use technology responsibly well beyond their elementary school years.

6 Quick Tips for Using Technology in the Classroom

The benefits of technology in education can revolutionize your classroom, but only when used intentionally. All it takes is a little time and personal training to help you understand the ins and outs of useful classroom tech.

Keep these six strategies and ideas in mind to help you get the most out of your classroom technology:

- Always use technology or learning programs yourself before trying it with your students so you can troubleshoot any issues in advance.[9]

- Most of today’s students are digital natives and have grown up around technology for their entire life. Listen to what your students know about technology and ask them for tip. They may just teach you something new![8]

- Use digital resources (like apps, texts, or social media groups) to keep parents informed about class activities and upcoming assignments.[5]

- Prioritize active digital activities, like online learning games or interactive lessons, over passive activities (like watching a video).

- If you’re an administrator, schedule a faculty training session on how to use your school’s technology and answer any questions.[10]

- Focus your technology-based lessons on teaching your students digital citizenship , or skills that will help them thoughtfully and effectively navigate digital media.[14]

- Groff, J., and Mouza, C. A Framework for Addressing Challenges to Classroom Technology Use. AACE Journal, January 2008, 16(1), pp. 21-46.

- Levy, L.A. 7 Reasons Why Digital Literacy is Important for Teachers. Retrieved from usc.edu: https://www.rossieronline.usc.edu/blog/teacher-digital-literacy/.

- Van Dusen, L.M., and Worthen, B.R. Can Integrated Instructional Technology Transform the Classroom? Educational Leadership, October 1995, 53(2), pp. 28-33.

- Rosenberg, J. Technology in the classroom: Friend or Foe? Retrieved from huffpost.com: hhttps://www.huffpost.com/entry/technology-in-the-classro_2_b_2018558..

- Venezky, R.L. Technology in the classroom: steps toward a new vision. Education, Communication & Information, 2004, 4(1), pp. 3-21.

- Buckenmeyer, J.A. Beyond Computers In The Classroom: Factors Related To Technology Adoption To Enhance Teaching And Learning. Contemporary Issues in Education Research. April 2010, 3(4), pp. 27-36.

- Bester, G., and Brand, L. The effect of technology on learner attention and achievement in the classroom. South African Journal of Education, 2013, 33(2), pp. 1-15.

- Reissman, H. 7 smart ways to use technology in classrooms. Retrieved from ted.com: https://ideas.ted.com/7-smart-ways-to-use-technology-in-classrooms/.

- Edutopia Staff. How to Integrate Technology. Retrieved from edutopia.org: https://www.edutopia.org/technology-integration-guide-implementation. Winters-Robinson, E. How Tech Can Engage Students, Simplify the School Day and Save Time for Teachers. Retrieved from edsurge.com: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-10-15-how-tech-can-engage-students-simplify-the-school-day-and-save-time-for-teachers.

- Couse, L.J., and Chen, D.W. A Tablet Computer for Young Children? Exploring its Viability for Early Childhood Education. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 2010, 43(1), pp. 75-96.

- Filer, D. Everyone’s Answering: Using Technology to Increase Classroom Participation. Nursing Education Perspectives, 2010, 31(4), pp. 247-250.

- Friedman, S. How Teachers Use Technology in the Classroom. Retrieved from thejournal.com: https://thejournal.com/articles/2019/04/15/how-teachers-use-technology-in-the-classroom.aspx.

- Mace, N. 8 Strategies to Manage the 21st Century Classroom . Retrieved from education.cu-portland.edu: https://education.cu-portland.edu/blog/classroom-resources/using-classroom-technology/.

- Keswani, B., Patni, P., and Banerjee, D. Role Of Technology In Education: A 21st Century Approach. Journal of Commerce and Instructional Technology, 2008, 8, pp.54-59.

- The Office of Educational Technology. Reimagining the Role of Technology in Education: 2017 National Education Technology Plan Update . Retrieved from tech.ed.gov: tech.ed.gov/files/2017/01/NETP17.pdf.

- Courville, K. Technology and its use in Education: Present Roles and Future Prospects. 2011 Recovery School District Technology Summit, 2011, pp. 1-19.

- Klopfer, E., Osterweil, S., Groff, J., and Haas, J. Using the technology of today, in the classroom today: the instructional power of digital games, social networking, simulations, and how teachers can leverage them . The Education Arcade, 2009, pp. 1-20.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics Announces New Recommendations for Children’s Media Use. Retrieved from aap.org: https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/Pages/American-Academy-of-Pediatrics-Announces-New-Recommendations-for-Childrens-Media-Use.aspx.

More education articles

10 of the Best Elementary Activities for the Last Days of School

The end of the school year can evoke a bittersweet feeling. It marks a moment for celebration as educators contemplate the growth and achievements of

Preparing Your Child for Kindergarten: 6 Important Skills to Foster

As someone who has had the privilege of being a kindergarten teacher, I vividly recall the excitement and anticipation of children stepping foot into my

National Poetry Month: Elementary Classroom Activities & Picture Books

Every April, the literary world comes alive with rhythm and rhyme as we celebrate National Poetry Month. For elementary school teachers, this month is an

Mental Health Awareness Month 2024: 7 Ways to Nurture Your Child’s Mental Health

MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving Awards Waterford.org a $10 Million Grant

REALIZING THE PROMISE:

Leading up to the 75th anniversary of the UN General Assembly, this “Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all?” publication kicks off the Center for Universal Education’s first playbook in a series to help improve education around the world.

It is intended as an evidence-based tool for ministries of education, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, to adopt and more successfully invest in education technology.

While there is no single education initiative that will achieve the same results everywhere—as school systems differ in learners and educators, as well as in the availability and quality of materials and technologies—an important first step is understanding how technology is used given specific local contexts and needs.

The surveys in this playbook are designed to be adapted to collect this information from educators, learners, and school leaders and guide decisionmakers in expanding the use of technology.

Introduction

While technology has disrupted most sectors of the economy and changed how we communicate, access information, work, and even play, its impact on schools, teaching, and learning has been much more limited. We believe that this limited impact is primarily due to technology being been used to replace analog tools, without much consideration given to playing to technology’s comparative advantages. These comparative advantages, relative to traditional “chalk-and-talk” classroom instruction, include helping to scale up standardized instruction, facilitate differentiated instruction, expand opportunities for practice, and increase student engagement. When schools use technology to enhance the work of educators and to improve the quality and quantity of educational content, learners will thrive.

Further, COVID-19 has laid bare that, in today’s environment where pandemics and the effects of climate change are likely to occur, schools cannot always provide in-person education—making the case for investing in education technology.

Here we argue for a simple yet surprisingly rare approach to education technology that seeks to:

- Understand the needs, infrastructure, and capacity of a school system—the diagnosis;

- Survey the best available evidence on interventions that match those conditions—the evidence; and

- Closely monitor the results of innovations before they are scaled up—the prognosis.

RELATED CONTENT

Podcast: How education technology can improve learning for all students

To make ed tech work, set clear goals, review the evidence, and pilot before you scale

The framework.

Our approach builds on a simple yet intuitive theoretical framework created two decades ago by two of the most prominent education researchers in the United States, David K. Cohen and Deborah Loewenberg Ball. They argue that what matters most to improve learning is the interactions among educators and learners around educational materials. We believe that the failed school-improvement efforts in the U.S. that motivated Cohen and Ball’s framework resemble the ed-tech reforms in much of the developing world to date in the lack of clarity improving the interactions between educators, learners, and the educational material. We build on their framework by adding parents as key agents that mediate the relationships between learners and educators and the material (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The instructional core

Adapted from Cohen and Ball (1999)

As the figure above suggests, ed-tech interventions can affect the instructional core in a myriad of ways. Yet, just because technology can do something, it does not mean it should. School systems in developing countries differ along many dimensions and each system is likely to have different needs for ed-tech interventions, as well as different infrastructure and capacity to enact such interventions.

The diagnosis:

How can school systems assess their needs and preparedness.

A useful first step for any school system to determine whether it should invest in education technology is to diagnose its:

- Specific needs to improve student learning (e.g., raising the average level of achievement, remediating gaps among low performers, and challenging high performers to develop higher-order skills);

- Infrastructure to adopt technology-enabled solutions (e.g., electricity connection, availability of space and outlets, stock of computers, and Internet connectivity at school and at learners’ homes); and

- Capacity to integrate technology in the instructional process (e.g., learners’ and educators’ level of familiarity and comfort with hardware and software, their beliefs about the level of usefulness of technology for learning purposes, and their current uses of such technology).

Before engaging in any new data collection exercise, school systems should take full advantage of existing administrative data that could shed light on these three main questions. This could be in the form of internal evaluations but also international learner assessments, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and/or the Progress in International Literacy Study (PIRLS), and the Teaching and Learning International Study (TALIS). But if school systems lack information on their preparedness for ed-tech reforms or if they seek to complement existing data with a richer set of indicators, we developed a set of surveys for learners, educators, and school leaders. Download the full report to see how we map out the main aspects covered by these surveys, in hopes of highlighting how they could be used to inform decisions around the adoption of ed-tech interventions.

The evidence:

How can school systems identify promising ed-tech interventions.

There is no single “ed-tech” initiative that will achieve the same results everywhere, simply because school systems differ in learners and educators, as well as in the availability and quality of materials and technologies. Instead, to realize the potential of education technology to accelerate student learning, decisionmakers should focus on four potential uses of technology that play to its comparative advantages and complement the work of educators to accelerate student learning (Figure 2). These comparative advantages include:

- Scaling up quality instruction, such as through prerecorded quality lessons.

- Facilitating differentiated instruction, through, for example, computer-adaptive learning and live one-on-one tutoring.

- Expanding opportunities to practice.

- Increasing learner engagement through videos and games.

Figure 2: Comparative advantages of technology

Here we review the evidence on ed-tech interventions from 37 studies in 20 countries*, organizing them by comparative advantage. It’s important to note that ours is not the only way to classify these interventions (e.g., video tutorials could be considered as a strategy to scale up instruction or increase learner engagement), but we believe it may be useful to highlight the needs that they could address and why technology is well positioned to do so.

When discussing specific studies, we report the magnitude of the effects of interventions using standard deviations (SDs). SDs are a widely used metric in research to express the effect of a program or policy with respect to a business-as-usual condition (e.g., test scores). There are several ways to make sense of them. One is to categorize the magnitude of the effects based on the results of impact evaluations. In developing countries, effects below 0.1 SDs are considered to be small, effects between 0.1 and 0.2 SDs are medium, and those above 0.2 SDs are large (for reviews that estimate the average effect of groups of interventions, called “meta analyses,” see e.g., Conn, 2017; Kremer, Brannen, & Glennerster, 2013; McEwan, 2014; Snilstveit et al., 2015; Evans & Yuan, 2020.)

*In surveying the evidence, we began by compiling studies from prior general and ed-tech specific evidence reviews that some of us have written and from ed-tech reviews conducted by others. Then, we tracked the studies cited by the ones we had previously read and reviewed those, as well. In identifying studies for inclusion, we focused on experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of education technology interventions from pre-school to secondary school in low- and middle-income countries that were released between 2000 and 2020. We only included interventions that sought to improve student learning directly (i.e., students’ interaction with the material), as opposed to interventions that have impacted achievement indirectly, by reducing teacher absence or increasing parental engagement. This process yielded 37 studies in 20 countries (see the full list of studies in Appendix B).

Scaling up standardized instruction

One of the ways in which technology may improve the quality of education is through its capacity to deliver standardized quality content at scale. This feature of technology may be particularly useful in three types of settings: (a) those in “hard-to-staff” schools (i.e., schools that struggle to recruit educators with the requisite training and experience—typically, in rural and/or remote areas) (see, e.g., Urquiola & Vegas, 2005); (b) those in which many educators are frequently absent from school (e.g., Chaudhury, Hammer, Kremer, Muralidharan, & Rogers, 2006; Muralidharan, Das, Holla, & Mohpal, 2017); and/or (c) those in which educators have low levels of pedagogical and subject matter expertise (e.g., Bietenbeck, Piopiunik, & Wiederhold, 2018; Bold et al., 2017; Metzler & Woessmann, 2012; Santibañez, 2006) and do not have opportunities to observe and receive feedback (e.g., Bruns, Costa, & Cunha, 2018; Cilliers, Fleisch, Prinsloo, & Taylor, 2018). Technology could address this problem by: (a) disseminating lessons delivered by qualified educators to a large number of learners (e.g., through prerecorded or live lessons); (b) enabling distance education (e.g., for learners in remote areas and/or during periods of school closures); and (c) distributing hardware preloaded with educational materials.

Prerecorded lessons

Technology seems to be well placed to amplify the impact of effective educators by disseminating their lessons. Evidence on the impact of prerecorded lessons is encouraging, but not conclusive. Some initiatives that have used short instructional videos to complement regular instruction, in conjunction with other learning materials, have raised student learning on independent assessments. For example, Beg et al. (2020) evaluated an initiative in Punjab, Pakistan in which grade 8 classrooms received an intervention that included short videos to substitute live instruction, quizzes for learners to practice the material from every lesson, tablets for educators to learn the material and follow the lesson, and LED screens to project the videos onto a classroom screen. After six months, the intervention improved the performance of learners on independent tests of math and science by 0.19 and 0.24 SDs, respectively but had no discernible effect on the math and science section of Punjab’s high-stakes exams.

One study suggests that approaches that are far less technologically sophisticated can also improve learning outcomes—especially, if the business-as-usual instruction is of low quality. For example, Naslund-Hadley, Parker, and Hernandez-Agramonte (2014) evaluated a preschool math program in Cordillera, Paraguay that used audio segments and written materials four days per week for an hour per day during the school day. After five months, the intervention improved math scores by 0.16 SDs, narrowing gaps between low- and high-achieving learners, and between those with and without educators with formal training in early childhood education.

Yet, the integration of prerecorded material into regular instruction has not always been successful. For example, de Barros (2020) evaluated an intervention that combined instructional videos for math and science with infrastructure upgrades (e.g., two “smart” classrooms, two TVs, and two tablets), printed workbooks for students, and in-service training for educators of learners in grades 9 and 10 in Haryana, India (all materials were mapped onto the official curriculum). After 11 months, the intervention negatively impacted math achievement (by 0.08 SDs) and had no effect on science (with respect to business as usual classes). It reduced the share of lesson time that educators devoted to instruction and negatively impacted an index of instructional quality. Likewise, Seo (2017) evaluated several combinations of infrastructure (solar lights and TVs) and prerecorded videos (in English and/or bilingual) for grade 11 students in northern Tanzania and found that none of the variants improved student learning, even when the videos were used. The study reports effects from the infrastructure component across variants, but as others have noted (Muralidharan, Romero, & Wüthrich, 2019), this approach to estimating impact is problematic.

A very similar intervention delivered after school hours, however, had sizeable effects on learners’ basic skills. Chiplunkar, Dhar, and Nagesh (2020) evaluated an initiative in Chennai (the capital city of the state of Tamil Nadu, India) delivered by the same organization as above that combined short videos that explained key concepts in math and science with worksheets, facilitator-led instruction, small groups for peer-to-peer learning, and occasional career counseling and guidance for grade 9 students. These lessons took place after school for one hour, five times a week. After 10 months, it had large effects on learners’ achievement as measured by tests of basic skills in math and reading, but no effect on a standardized high-stakes test in grade 10 or socio-emotional skills (e.g., teamwork, decisionmaking, and communication).

Drawing general lessons from this body of research is challenging for at least two reasons. First, all of the studies above have evaluated the impact of prerecorded lessons combined with several other components (e.g., hardware, print materials, or other activities). Therefore, it is possible that the effects found are due to these additional components, rather than to the recordings themselves, or to the interaction between the two (see Muralidharan, 2017 for a discussion of the challenges of interpreting “bundled” interventions). Second, while these studies evaluate some type of prerecorded lessons, none examines the content of such lessons. Thus, it seems entirely plausible that the direction and magnitude of the effects depends largely on the quality of the recordings (e.g., the expertise of the educator recording it, the amount of preparation that went into planning the recording, and its alignment with best teaching practices).

These studies also raise three important questions worth exploring in future research. One of them is why none of the interventions discussed above had effects on high-stakes exams, even if their materials are typically mapped onto the official curriculum. It is possible that the official curricula are simply too challenging for learners in these settings, who are several grade levels behind expectations and who often need to reinforce basic skills (see Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). Another question is whether these interventions have long-term effects on teaching practices. It seems plausible that, if these interventions are deployed in contexts with low teaching quality, educators may learn something from watching the videos or listening to the recordings with learners. Yet another question is whether these interventions make it easier for schools to deliver instruction to learners whose native language is other than the official medium of instruction.

Distance education

Technology can also allow learners living in remote areas to access education. The evidence on these initiatives is encouraging. For example, Johnston and Ksoll (2017) evaluated a program that broadcasted live instruction via satellite to rural primary school students in the Volta and Greater Accra regions of Ghana. For this purpose, the program also equipped classrooms with the technology needed to connect to a studio in Accra, including solar panels, a satellite modem, a projector, a webcam, microphones, and a computer with interactive software. After two years, the intervention improved the numeracy scores of students in grades 2 through 4, and some foundational literacy tasks, but it had no effect on attendance or classroom time devoted to instruction, as captured by school visits. The authors interpreted these results as suggesting that the gains in achievement may be due to improving the quality of instruction that children received (as opposed to increased instructional time). Naik, Chitre, Bhalla, and Rajan (2019) evaluated a similar program in the Indian state of Karnataka and also found positive effects on learning outcomes, but it is not clear whether those effects are due to the program or due to differences in the groups of students they compared to estimate the impact of the initiative.

In one context (Mexico), this type of distance education had positive long-term effects. Navarro-Sola (2019) took advantage of the staggered rollout of the telesecundarias (i.e., middle schools with lessons broadcasted through satellite TV) in 1968 to estimate its impact. The policy had short-term effects on students’ enrollment in school: For every telesecundaria per 50 children, 10 students enrolled in middle school and two pursued further education. It also had a long-term influence on the educational and employment trajectory of its graduates. Each additional year of education induced by the policy increased average income by nearly 18 percent. This effect was attributable to more graduates entering the labor force and shifting from agriculture and the informal sector. Similarly, Fabregas (2019) leveraged a later expansion of this policy in 1993 and found that each additional telesecundaria per 1,000 adolescents led to an average increase of 0.2 years of education, and a decline in fertility for women, but no conclusive evidence of long-term effects on labor market outcomes.

It is crucial to interpret these results keeping in mind the settings where the interventions were implemented. As we mention above, part of the reason why they have proven effective is that the “counterfactual” conditions for learning (i.e., what would have happened to learners in the absence of such programs) was either to not have access to schooling or to be exposed to low-quality instruction. School systems interested in taking up similar interventions should assess the extent to which their learners (or parts of their learner population) find themselves in similar conditions to the subjects of the studies above. This illustrates the importance of assessing the needs of a system before reviewing the evidence.

Preloaded hardware

Technology also seems well positioned to disseminate educational materials. Specifically, hardware (e.g., desktop computers, laptops, or tablets) could also help deliver educational software (e.g., word processing, reference texts, and/or games). In theory, these materials could not only undergo a quality assurance review (e.g., by curriculum specialists and educators), but also draw on the interactions with learners for adjustments (e.g., identifying areas needing reinforcement) and enable interactions between learners and educators.

In practice, however, most initiatives that have provided learners with free computers, laptops, and netbooks do not leverage any of the opportunities mentioned above. Instead, they install a standard set of educational materials and hope that learners find them helpful enough to take them up on their own. Students rarely do so, and instead use the laptops for recreational purposes—often, to the detriment of their learning (see, e.g., Malamud & Pop-Eleches, 2011). In fact, free netbook initiatives have not only consistently failed to improve academic achievement in math or language (e.g., Cristia et al., 2017), but they have had no impact on learners’ general computer skills (e.g., Beuermann et al., 2015). Some of these initiatives have had small impacts on cognitive skills, but the mechanisms through which those effects occurred remains unclear.

To our knowledge, the only successful deployment of a free laptop initiative was one in which a team of researchers equipped the computers with remedial software. Mo et al. (2013) evaluated a version of the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program for grade 3 students in migrant schools in Beijing, China in which the laptops were loaded with a remedial software mapped onto the national curriculum for math (similar to the software products that we discuss under “practice exercises” below). After nine months, the program improved math achievement by 0.17 SDs and computer skills by 0.33 SDs. If a school system decides to invest in free laptops, this study suggests that the quality of the software on the laptops is crucial.

To date, however, the evidence suggests that children do not learn more from interacting with laptops than they do from textbooks. For example, Bando, Gallego, Gertler, and Romero (2016) compared the effect of free laptop and textbook provision in 271 elementary schools in disadvantaged areas of Honduras. After seven months, students in grades 3 and 6 who had received the laptops performed on par with those who had received the textbooks in math and language. Further, even if textbooks essentially become obsolete at the end of each school year, whereas laptops can be reloaded with new materials for each year, the costs of laptop provision (not just the hardware, but also the technical assistance, Internet, and training associated with it) are not yet low enough to make them a more cost-effective way of delivering content to learners.

Evidence on the provision of tablets equipped with software is encouraging but limited. For example, de Hoop et al. (2020) evaluated a composite intervention for first grade students in Zambia’s Eastern Province that combined infrastructure (electricity via solar power), hardware (projectors and tablets), and educational materials (lesson plans for educators and interactive lessons for learners, both loaded onto the tablets and mapped onto the official Zambian curriculum). After 14 months, the intervention had improved student early-grade reading by 0.4 SDs, oral vocabulary scores by 0.25 SDs, and early-grade math by 0.22 SDs. It also improved students’ achievement by 0.16 on a locally developed assessment. The multifaceted nature of the program, however, makes it challenging to identify the components that are driving the positive effects. Pitchford (2015) evaluated an intervention that provided tablets equipped with educational “apps,” to be used for 30 minutes per day for two months to develop early math skills among students in grades 1 through 3 in Lilongwe, Malawi. The evaluation found positive impacts in math achievement, but the main study limitation is that it was conducted in a single school.

Facilitating differentiated instruction

Another way in which technology may improve educational outcomes is by facilitating the delivery of differentiated or individualized instruction. Most developing countries massively expanded access to schooling in recent decades by building new schools and making education more affordable, both by defraying direct costs, as well as compensating for opportunity costs (Duflo, 2001; World Bank, 2018). These initiatives have not only rapidly increased the number of learners enrolled in school, but have also increased the variability in learner’ preparation for schooling. Consequently, a large number of learners perform well below grade-based curricular expectations (see, e.g., Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2011; Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). These learners are unlikely to get much from “one-size-fits-all” instruction, in which a single educator delivers instruction deemed appropriate for the middle (or top) of the achievement distribution (Banerjee & Duflo, 2011). Technology could potentially help these learners by providing them with: (a) instruction and opportunities for practice that adjust to the level and pace of preparation of each individual (known as “computer-adaptive learning” (CAL)); or (b) live, one-on-one tutoring.

Computer-adaptive learning

One of the main comparative advantages of technology is its ability to diagnose students’ initial learning levels and assign students to instruction and exercises of appropriate difficulty. No individual educator—no matter how talented—can be expected to provide individualized instruction to all learners in his/her class simultaneously . In this respect, technology is uniquely positioned to complement traditional teaching. This use of technology could help learners master basic skills and help them get more out of schooling.

Although many software products evaluated in recent years have been categorized as CAL, many rely on a relatively coarse level of differentiation at an initial stage (e.g., a diagnostic test) without further differentiation. We discuss these initiatives under the category of “increasing opportunities for practice” below. CAL initiatives complement an initial diagnostic with dynamic adaptation (i.e., at each response or set of responses from learners) to adjust both the initial level of difficulty and rate at which it increases or decreases, depending on whether learners’ responses are correct or incorrect.

Existing evidence on this specific type of programs is highly promising. Most famously, Banerjee et al. (2007) evaluated CAL software in Vadodara, in the Indian state of Gujarat, in which grade 4 students were offered two hours of shared computer time per week before and after school, during which they played games that involved solving math problems. The level of difficulty of such problems adjusted based on students’ answers. This program improved math achievement by 0.35 and 0.47 SDs after one and two years of implementation, respectively. Consistent with the promise of personalized learning, the software improved achievement for all students. In fact, one year after the end of the program, students assigned to the program still performed 0.1 SDs better than those assigned to a business as usual condition. More recently, Muralidharan, et al. (2019) evaluated a “blended learning” initiative in which students in grades 4 through 9 in Delhi, India received 45 minutes of interaction with CAL software for math and language, and 45 minutes of small group instruction before or after going to school. After only 4.5 months, the program improved achievement by 0.37 SDs in math and 0.23 SDs in Hindi. While all learners benefited from the program in absolute terms, the lowest performing learners benefited the most in relative terms, since they were learning very little in school.

We see two important limitations from this body of research. First, to our knowledge, none of these initiatives has been evaluated when implemented during the school day. Therefore, it is not possible to distinguish the effect of the adaptive software from that of additional instructional time. Second, given that most of these programs were facilitated by local instructors, attempts to distinguish the effect of the software from that of the instructors has been mostly based on noncausal evidence. A frontier challenge in this body of research is to understand whether CAL software can increase the effectiveness of school-based instruction by substituting part of the regularly scheduled time for math and language instruction.

Live one-on-one tutoring

Recent improvements in the speed and quality of videoconferencing, as well as in the connectivity of remote areas, have enabled yet another way in which technology can help personalization: live (i.e., real-time) one-on-one tutoring. While the evidence on in-person tutoring is scarce in developing countries, existing studies suggest that this approach works best when it is used to personalize instruction (see, e.g., Banerjee et al., 2007; Banerji, Berry, & Shotland, 2015; Cabezas, Cuesta, & Gallego, 2011).

There are almost no studies on the impact of online tutoring—possibly, due to the lack of hardware and Internet connectivity in low- and middle-income countries. One exception is Chemin and Oledan (2020)’s recent evaluation of an online tutoring program for grade 6 students in Kianyaga, Kenya to learn English from volunteers from a Canadian university via Skype ( videoconferencing software) for one hour per week after school. After 10 months, program beneficiaries performed 0.22 SDs better in a test of oral comprehension, improved their comfort using technology for learning, and became more willing to engage in cross-cultural communication. Importantly, while the tutoring sessions used the official English textbooks and sought in part to help learners with their homework, tutors were trained on several strategies to teach to each learner’s individual level of preparation, focusing on basic skills if necessary. To our knowledge, similar initiatives within a country have not yet been rigorously evaluated.

Expanding opportunities for practice

A third way in which technology may improve the quality of education is by providing learners with additional opportunities for practice. In many developing countries, lesson time is primarily devoted to lectures, in which the educator explains the topic and the learners passively copy explanations from the blackboard. This setup leaves little time for in-class practice. Consequently, learners who did not understand the explanation of the material during lecture struggle when they have to solve homework assignments on their own. Technology could potentially address this problem by allowing learners to review topics at their own pace.

Practice exercises

Technology can help learners get more out of traditional instruction by providing them with opportunities to implement what they learn in class. This approach could, in theory, allow some learners to anchor their understanding of the material through trial and error (i.e., by realizing what they may not have understood correctly during lecture and by getting better acquainted with special cases not covered in-depth in class).

Existing evidence on practice exercises reflects both the promise and the limitations of this use of technology in developing countries. For example, Lai et al. (2013) evaluated a program in Shaanxi, China where students in grades 3 and 5 were required to attend two 40-minute remedial sessions per week in which they first watched videos that reviewed the material that had been introduced in their math lessons that week and then played games to practice the skills introduced in the video. After four months, the intervention improved math achievement by 0.12 SDs. Many other evaluations of comparable interventions have found similar small-to-moderate results (see, e.g., Lai, Luo, Zhang, Huang, & Rozelle, 2015; Lai et al., 2012; Mo et al., 2015; Pitchford, 2015). These effects, however, have been consistently smaller than those of initiatives that adjust the difficulty of the material based on students’ performance (e.g., Banerjee et al., 2007; Muralidharan, et al., 2019). We hypothesize that these programs do little for learners who perform several grade levels behind curricular expectations, and who would benefit more from a review of foundational concepts from earlier grades.

We see two important limitations from this research. First, most initiatives that have been evaluated thus far combine instructional videos with practice exercises, so it is hard to know whether their effects are driven by the former or the latter. In fact, the program in China described above allowed learners to ask their peers whenever they did not understand a difficult concept, so it potentially also captured the effect of peer-to-peer collaboration. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed this gap in the evidence.

Second, most of these programs are implemented before or after school, so we cannot distinguish the effect of additional instructional time from that of the actual opportunity for practice. The importance of this question was first highlighted by Linden (2008), who compared two delivery mechanisms for game-based remedial math software for students in grades 2 and 3 in a network of schools run by a nonprofit organization in Gujarat, India: one in which students interacted with the software during the school day and another one in which students interacted with the software before or after school (in both cases, for three hours per day). After a year, the first version of the program had negatively impacted students’ math achievement by 0.57 SDs and the second one had a null effect. This study suggested that computer-assisted learning is a poor substitute for regular instruction when it is of high quality, as was the case in this well-functioning private network of schools.

In recent years, several studies have sought to remedy this shortcoming. Mo et al. (2014) were among the first to evaluate practice exercises delivered during the school day. They evaluated an initiative in Shaanxi, China in which students in grades 3 and 5 were required to interact with the software similar to the one in Lai et al. (2013) for two 40-minute sessions per week. The main limitation of this study, however, is that the program was delivered during regularly scheduled computer lessons, so it could not determine the impact of substituting regular math instruction. Similarly, Mo et al. (2020) evaluated a self-paced and a teacher-directed version of a similar program for English for grade 5 students in Qinghai, China. Yet, the key shortcoming of this study is that the teacher-directed version added several components that may also influence achievement, such as increased opportunities for teachers to provide students with personalized assistance when they struggled with the material. Ma, Fairlie, Loyalka, and Rozelle (2020) compared the effectiveness of additional time-delivered remedial instruction for students in grades 4 to 6 in Shaanxi, China through either computer-assisted software or using workbooks. This study indicates whether additional instructional time is more effective when using technology, but it does not address the question of whether school systems may improve the productivity of instructional time during the school day by substituting educator-led with computer-assisted instruction.

Increasing learner engagement

Another way in which technology may improve education is by increasing learners’ engagement with the material. In many school systems, regular “chalk and talk” instruction prioritizes time for educators’ exposition over opportunities for learners to ask clarifying questions and/or contribute to class discussions. This, combined with the fact that many developing-country classrooms include a very large number of learners (see, e.g., Angrist & Lavy, 1999; Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2015), may partially explain why the majority of those students are several grade levels behind curricular expectations (e.g., Muralidharan, et al., 2019; Muralidharan & Zieleniak, 2014; Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). Technology could potentially address these challenges by: (a) using video tutorials for self-paced learning and (b) presenting exercises as games and/or gamifying practice.

Video tutorials

Technology can potentially increase learner effort and understanding of the material by finding new and more engaging ways to deliver it. Video tutorials designed for self-paced learning—as opposed to videos for whole class instruction, which we discuss under the category of “prerecorded lessons” above—can increase learner effort in multiple ways, including: allowing learners to focus on topics with which they need more help, letting them correct errors and misconceptions on their own, and making the material appealing through visual aids. They can increase understanding by breaking the material into smaller units and tackling common misconceptions.

In spite of the popularity of instructional videos, there is relatively little evidence on their effectiveness. Yet, two recent evaluations of different versions of the Khan Academy portal, which mainly relies on instructional videos, offer some insight into their impact. First, Ferman, Finamor, and Lima (2019) evaluated an initiative in 157 public primary and middle schools in five cities in Brazil in which the teachers of students in grades 5 and 9 were taken to the computer lab to learn math from the platform for 50 minutes per week. The authors found that, while the intervention slightly improved learners’ attitudes toward math, these changes did not translate into better performance in this subject. The authors hypothesized that this could be due to the reduction of teacher-led math instruction.

More recently, Büchel, Jakob, Kühnhanss, Steffen, and Brunetti (2020) evaluated an after-school, offline delivery of the Khan Academy portal in grades 3 through 6 in 302 primary schools in Morazán, El Salvador. Students in this study received 90 minutes per week of additional math instruction (effectively nearly doubling total math instruction per week) through teacher-led regular lessons, teacher-assisted Khan Academy lessons, or similar lessons assisted by technical supervisors with no content expertise. (Importantly, the first group provided differentiated instruction, which is not the norm in Salvadorian schools). All three groups outperformed both schools without any additional lessons and classrooms without additional lessons in the same schools as the program. The teacher-assisted Khan Academy lessons performed 0.24 SDs better, the supervisor-led lessons 0.22 SDs better, and the teacher-led regular lessons 0.15 SDs better, but the authors could not determine whether the effects across versions were different.

Together, these studies suggest that instructional videos work best when provided as a complement to, rather than as a substitute for, regular instruction. Yet, the main limitation of these studies is the multifaceted nature of the Khan Academy portal, which also includes other components found to positively improve learner achievement, such as differentiated instruction by students’ learning levels. While the software does not provide the type of personalization discussed above, learners are asked to take a placement test and, based on their score, educators assign them different work. Therefore, it is not clear from these studies whether the effects from Khan Academy are driven by its instructional videos or to the software’s ability to provide differentiated activities when combined with placement tests.

Games and gamification

Technology can also increase learner engagement by presenting exercises as games and/or by encouraging learner to play and compete with others (e.g., using leaderboards and rewards)—an approach known as “gamification.” Both approaches can increase learner motivation and effort by presenting learners with entertaining opportunities for practice and by leveraging peers as commitment devices.

There are very few studies on the effects of games and gamification in low- and middle-income countries. Recently, Araya, Arias Ortiz, Bottan, and Cristia (2019) evaluated an initiative in which grade 4 students in Santiago, Chile were required to participate in two 90-minute sessions per week during the school day with instructional math software featuring individual and group competitions (e.g., tracking each learner’s standing in his/her class and tournaments between sections). After nine months, the program led to improvements of 0.27 SDs in the national student assessment in math (it had no spillover effects on reading). However, it had mixed effects on non-academic outcomes. Specifically, the program increased learners’ willingness to use computers to learn math, but, at the same time, increased their anxiety toward math and negatively impacted learners’ willingness to collaborate with peers. Finally, given that one of the weekly sessions replaced regular math instruction and the other one represented additional math instructional time, it is not clear whether the academic effects of the program are driven by the software or the additional time devoted to learning math.

The prognosis:

How can school systems adopt interventions that match their needs.

Here are five specific and sequential guidelines for decisionmakers to realize the potential of education technology to accelerate student learning.

1. Take stock of how your current schools, educators, and learners are engaging with technology .

Carry out a short in-school survey to understand the current practices and potential barriers to adoption of technology (we have included suggested survey instruments in the Appendices); use this information in your decisionmaking process. For example, we learned from conversations with current and former ministers of education from various developing regions that a common limitation to technology use is regulations that hold school leaders accountable for damages to or losses of devices. Another common barrier is lack of access to electricity and Internet, or even the availability of sufficient outlets for charging devices in classrooms. Understanding basic infrastructure and regulatory limitations to the use of education technology is a first necessary step. But addressing these limitations will not guarantee that introducing or expanding technology use will accelerate learning. The next steps are thus necessary.

“In Africa, the biggest limit is connectivity. Fiber is expensive, and we don’t have it everywhere. The continent is creating a digital divide between cities, where there is fiber, and the rural areas. The [Ghanaian] administration put in schools offline/online technologies with books, assessment tools, and open source materials. In deploying this, we are finding that again, teachers are unfamiliar with it. And existing policies prohibit students to bring their own tablets or cell phones. The easiest way to do it would have been to let everyone bring their own device. But policies are against it.” H.E. Matthew Prempeh, Minister of Education of Ghana, on the need to understand the local context.

2. Consider how the introduction of technology may affect the interactions among learners, educators, and content .

Our review of the evidence indicates that technology may accelerate student learning when it is used to scale up access to quality content, facilitate differentiated instruction, increase opportunities for practice, or when it increases learner engagement. For example, will adding electronic whiteboards to classrooms facilitate access to more quality content or differentiated instruction? Or will these expensive boards be used in the same way as the old chalkboards? Will providing one device (laptop or tablet) to each learner facilitate access to more and better content, or offer students more opportunities to practice and learn? Solely introducing technology in classrooms without additional changes is unlikely to lead to improved learning and may be quite costly. If you cannot clearly identify how the interactions among the three key components of the instructional core (educators, learners, and content) may change after the introduction of technology, then it is probably not a good idea to make the investment. See Appendix A for guidance on the types of questions to ask.

3. Once decisionmakers have a clear idea of how education technology can help accelerate student learning in a specific context, it is important to define clear objectives and goals and establish ways to regularly assess progress and make course corrections in a timely manner .

For instance, is the education technology expected to ensure that learners in early grades excel in foundational skills—basic literacy and numeracy—by age 10? If so, will the technology provide quality reading and math materials, ample opportunities to practice, and engaging materials such as videos or games? Will educators be empowered to use these materials in new ways? And how will progress be measured and adjusted?

4. How this kind of reform is approached can matter immensely for its success.

It is easy to nod to issues of “implementation,” but that needs to be more than rhetorical. Keep in mind that good use of education technology requires thinking about how it will affect learners, educators, and parents. After all, giving learners digital devices will make no difference if they get broken, are stolen, or go unused. Classroom technologies only matter if educators feel comfortable putting them to work. Since good technology is generally about complementing or amplifying what educators and learners already do, it is almost always a mistake to mandate programs from on high. It is vital that technology be adopted with the input of educators and families and with attention to how it will be used. If technology goes unused or if educators use it ineffectually, the results will disappoint—no matter the virtuosity of the technology. Indeed, unused education technology can be an unnecessary expenditure for cash-strapped education systems. This is why surveying context, listening to voices in the field, examining how technology is used, and planning for course correction is essential.

5. It is essential to communicate with a range of stakeholders, including educators, school leaders, parents, and learners .

Technology can feel alien in schools, confuse parents and (especially) older educators, or become an alluring distraction. Good communication can help address all of these risks. Taking care to listen to educators and families can help ensure that programs are informed by their needs and concerns. At the same time, deliberately and consistently explaining what technology is and is not supposed to do, how it can be most effectively used, and the ways in which it can make it more likely that programs work as intended. For instance, if teachers fear that technology is intended to reduce the need for educators, they will tend to be hostile; if they believe that it is intended to assist them in their work, they will be more receptive. Absent effective communication, it is easy for programs to “fail” not because of the technology but because of how it was used. In short, past experience in rolling out education programs indicates that it is as important to have a strong intervention design as it is to have a solid plan to socialize it among stakeholders.

Beyond reopening: A leapfrog moment to transform education?

On September 14, the Center for Universal Education (CUE) will host a webinar to discuss strategies, including around the effective use of education technology, for ensuring resilient schools in the long term and to launch a new education technology playbook “Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all?”

file-pdf Full Playbook – Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all? file-pdf References file-pdf Appendix A – Instruments to assess availability and use of technology file-pdf Appendix B – List of reviewed studies file-pdf Appendix C – How may technology affect interactions among students, teachers, and content?

About the Authors

Alejandro j. ganimian, emiliana vegas, frederick m. hess.

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

What is Educational Technology? [Definition, Examples & Impact]

What is Educational Technology? [Tools & Media]

What is educational technology [theory & practice], careers in educational technology [value of a master’s degree].

From the ancient abacus to handheld calculators, from slide projectors and classroom film strips to virtual reality and next-generation e-learning, educational technology continues to evolve in exciting new ways — inspiring teachers and students alike.

Technology is continually changing the way we work and play, create and communicate. So it’s only natural that advancements in digital technology are also creating game-changing opportunities in the world of education.

For teachers, technology is opening up new possibilities to enrich and stimulate young minds. Today, there is growing excitement around the potential for assistive technology, virtual and augmented reality, high-tech collaboration tools, gamification, podcasting, blogging, 3D printing, artificial intelligence, personalized learning and much more.

Here, we’ll explore some of the most promising examples of educational technology and some specific edtech tools and trends. But first let’s take a closer look at what we mean when we talk about “educational technology,” because the discussion can refer to both:

- The theory and practice of educational approaches to learning, as well as

- The technological tools that assist in the development and communication of knowledge

One important definition of educational technology focuses on “the technological tools and media that assist in the communication of knowledge, and its development and exchange.”

Take augmented reality and virtual reality , for example. Writing about the “Top 6 Digital Transformation Trends In Education” in Forbes.com, technology innovation specialist Daniel Newman discusses using AR and VR to “enhance teacher instruction while simultaneously creating immersive lessons that are fun and engaging for the student.” He invites us to imagine using virtual reality to transport students to ancient Greece.

Gamification combines playing and learning by utilizing gaming as an instructional tool, according to Newman, who explains that incorporating gaming technology into the classroom “can make learning difficult subject matter more exciting and interactive.”

Regarding artificial intelligence , Newman notes that a university in Australia used IBM’s Watson to create a virtual student advisory service that was available 24/7/365. Apparently Watson’s virtual advisors fielded more than 30,000 questions in the first trimester, freeing up human advisors to handle more complex issues.

ProwdigyGame.com, whose free curriculum-aligned math game for Grades 1-8 is used by millions of students, teachers and parents, offers specific tips for leveraging educational technology tools in a report titled “25 Easy Ways to Use Technology in the Classroom.” Their ideas include:

- Running a Virtual Field Trip : Explore famous locations such as the Empire State Building or the Great Barrier Reef; or preview actual field trips by using technology to “visit” the locations beforehand.

- Participating in a Webquest : These educational adventures encourage students to find and process information by adding an interesting spin to the research process. For example, they could be placed in the role of detective to solve a specific “case,” collecting clues about a curriculum topic by investigating specified sources and web pages.

- Podcasting : Playing relevant podcasts — or assisting students in creating their own — can be a great way to supplement lessons, engage auditory learners and even empower students to develop new creative skills.

Educational technology strategist David Andrade reports in EdTechMagazine.com ( “What Is on the Horizon for Education Technology?” ) that current tools and trends include online learning and makerspaces, “with robotics and virtual reality expected to be widely adopted in the near future.” Peeking a little further into the future, Andrade says studies indicate that “artificial intelligence and wearable technology will be considered mainstream within four to five years.”

In practice, future innovation will come from the hearts and minds of the teachers who develop the knowledge and skills needed to discover the most engaging, effective ways to use educational technology strategies in classrooms, and virtual classrooms, far and wide.

Another essential definition of educational technology focuses on the theory and practice of utilizing new technology to develop and implement innovative educational approaches to learning and student achievement.

Behind all the high-tech tools, the digital bells and whistles, are the teachers who possess the skill — and the inspiration — to use these new technologies to expand the educational universe of their students.

According to a report by the International Society for Technology in Education ( “11 Hot EdTech Trends to Watch” ), “the most compelling topics among educators who embrace technology for learning and teaching are not about the tech at all, but about the students.”

Benefits for students include expanded opportunities for personalized learning , more collaborative classrooms and new strategies such as so-called “flipped learning,” in which students are introduced to the subject material outside the classroom (often online), with classroom time then being used to deepen understanding through discussion and problem-solving activities with peers.

For teachers who aspire to make an impact in this discipline, earning a master’s in educational technology is obviously about learning new tools, strategies and practices, but it’s also about understanding the supporting structures that must be in place to ensure the most successful outcomes. These include:

- Policy and legal issues

- Ethical issues (student privacy, etc.)

- Funding, grants and budgets

- Real-world applications (the world of work, partnership opportunities, etc.)

- Networking basics, hardware, learning management software

- Equity (community/school access and assets, student access)

- Ability to complete a school or district needs assessment/site tech survey analysis

Therefore, for educators who are inspired by the immense potential of educational technology, the value of a master’s degree cannot be overstated.

“We need technology in every classroom and in every student and teacher’s hand,” says education technology pioneer David Warlick, “because it is the pen and paper of our time, and it is the lens through which we experience much of our world.”

In recent years, rising interest in educational technology has led to the emergence of new advanced degree programs that are designed to prepare educators to shift into an innovator’s mindset and become transformative technology leaders in their classroom, school or district.

The best programs are structured to impart a comprehensive understanding of the tools used in educational technology, the theories and practices, and critically important related issues (budgeting, legal/ethical considerations, real-world partnership opportunities, educational equity, etc.) that are essential for such technology-enhanced programs to deliver on their potential to inspire student learning, achievement and creativity.

For example, the University of San Diego, well-known for its innovative, online Master of Education program, is launching a new specialization. The program is designed to prepare teachers to become effective K-12 technology leaders and coaches, virtual educators and instructional innovators who embrace technology-influenced teaching practices to empower student learning.

The program’s fully online format — in which students learn from expert instructors who possess deep experience in the field, while also interacting with fellow teachers from across the country — enables busy education professionals to complete their master’s degree in 20 months while working full time.

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Top 11 Reasons to get Your Master of Education Degree

Free 22-page Book

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Global Education Monitoring Report

- 2023 GEM REPORT

Technology in education

- Recommendations

- 2023 Webpage

- Press Release

- RELATED PUBLICATIONS

- Background papers

- 2021/2 GEM Report

- 2020 Report

- 2019 Report

- 2017/8 Report

- 2016 Report

A tool on whose terms?

Ismael Martínez Sánchez/ProFuturo

- Monitoring SDG 4

- 2023 webpage

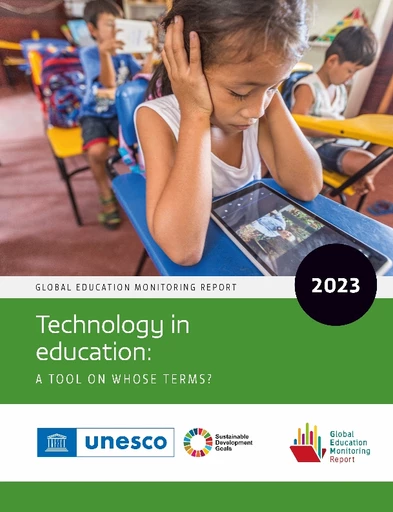

Major advances in technology, especially digital technology, are rapidly transforming the world. Information and communication technology (ICT) has been applied for 100 years in education, ever since the popularization of radio in the 1920s. But it is the use of digital technology over the past 40 years that has the most significant potential to transform education. An education technology industry has emerged and focused, in turn, on the development and distribution of education content, learning management systems, language applications, augmented and virtual reality, personalized tutoring, and testing. Most recently, breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), methods have increased the power of education technology tools, leading to speculation that technology could even supplant human interaction in education.

In the past 20 years, learners, educators and institutions have widely adopted digital technology tools. The number of students in MOOCs increased from 0 in 2012 to at least 220 million in 2021. The language learning application Duolingo had 20 million daily active users in 2023, and Wikipedia had 244 million page views per day in 2021. The 2018 PISA found that 65% of 15-year-old students in OECD countries were in schools whose principals agreed that teachers had the technical and pedagogical skills to integrate digital devices in instruction and 54% in schools where an effective online learning support platform was available; these shares are believed to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, the percentage of internet users rose from 16% in 2005 to 66% in 2022. About 50% of the world’s lower secondary schools were connected to the internet for pedagogical purposes in 2022.

The adoption of digital technology has resulted in many changes in education and learning. The set of basic skills that young people are expected to learn in school, at least in richer countries, has expanded to include a broad range of new ones to navigate the digital world. In many classrooms, paper has been replaced by screens and pens by keyboards. COVID-19 can be seen as a natural experiment where learning switched online for entire education systems virtually overnight. Higher education is the subsector with the highest rate of digital technology adoption, with online management platforms replacing campuses. The use of data analytics has grown in education management. Technology has made a wide range of informal learning opportunities accessible.

Yet the extent to which technology has transformed education needs to be debated. Change resulting from the use of digital technology is incremental, uneven and bigger in some contexts than others. The application of digital technology varies by community and socioeconomic level, by teacher willingness and preparedness, by education level, and by country income. Except in the most technologically advanced countries, computers and devices are not used in classrooms on a large scale. Technology use is not universal and will not become so any time soon. Moreover, evidence is mixed on its impact: Some types of technology seem to be effective in improving some kinds of learning. The short- and long-term costs of using digital technology appear to be significantly underestimated. The most disadvantaged are typically denied the opportunity to benefit from this technology.

Too much attention on technology in education usually comes at a high cost. Resources spent on technology, rather than on classrooms, teachers and textbooks for all children in low- and lower-middle-income countries lacking access to these resources are likely to lead to the world being further away from achieving the global education goal, SDG 4. Some of the world’s richest countries ensured universal secondary schooling and minimum learning competencies before the advent of digital technology. Children can learn without it.

However, their education is unlikely to be as relevant without digital technology. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights defines the purpose of education as promoting the ‘full development of the human personality’, strengthening ‘respect for … fundamental freedoms’ and promoting ‘understanding, tolerance and friendship’. This notion needs to move with the times. An expanded definition of the right to education could include effective support by technology for all learners to fulfil their potential, regardless of context or circumstance.

Clear objectives and principles are needed to ensure that technology use is of benefit and avoids harm. The negative and harmful aspects in the use of digital technology in education and society include risk of distraction and lack of human contact. Unregulated technology even poses threats to democracy and human rights, for instance through invasion of privacy and stoking of hatred. Education systems need to be better prepared to teach about and through digital technology, a tool that must serve the best interests of all learners, teachers and administrators. Impartial evidence showing that technology is being used in some places to improve education, and good examples of such use, need to be shared more widely so that the optimal mode of delivery can be assured for each context.

CAN TECHNOLOGY HELP SOLVE THE MOST IMPORTANT CHALLENGES IN EDUCATION?

Discussions about education technology are focused on technology rather than education. The first question should be: What are the most important challenges in education? As a basis for discussion, consider the following three challenges:

- Equity and inclusion: Is fulfilment of the right to choose the education one wants and to realize one’s full potential through education compatible with the goal of equality? If not, how can education become the great equalizer?

- Quality: Do education’s content and delivery support societies in achieving sustainable development objectives? If not, how can education help learners to not only acquire knowledge but also be agents of change?

- Efficiency: Does the current institutional arrangement of teaching learners in classrooms support the achievement of equity and quality? If not, how can education balance individualized instruction and socialization needs?

How best can digital technology be included in a strategy to tackle these challenges, and under what conditions? Digital technology packages and transmits information on an unprecedented scale at high speed and low cost. Information storage has revolutionized the volume of accessible knowledge. Information processing enables learners to receive immediate feedback and, through interaction with machines, adapt their learning pace and trajectory: Learners can organize the sequence of what they learn to suit their background and characteristics. Information sharing lowers the cost of interaction and communication. But while such technology has tremendous potential, many tools have not been designed for application to education. Not enough attention has been given to how they are applied in education and even less to how they should be applied in different education contexts.

On the question of equity and inclusion , ICT – and digital technology in particular – helps lower the education access cost for some disadvantaged groups: Those who live in remote areas are displaced, face learning difficulties, lack time or have missed out on past education opportunities. But while access to digital technology has expanded rapidly, there are deep divides in access. Disadvantaged groups own fewer devices, are less connected to the internet (Figure 1) and have fewer resources at home. The cost of much technology is falling rapidly but is still too high for some. Households that are better off can buy technology earlier, giving them more advantages and compounding disparity. Inequality in access to technology exacerbates existing inequality in access to education, a weakness exposed during the COVID-19 school closures.

Figure 1: Internet connectivity is highly unequal

Percentage of 3- to 17-year-olds with internet connection at home, by wealth quintile, selected countries, 2017–19 Source: UNICEF database.

Education quality is a multifaceted concept. It encompasses adequate inputs (e.g. availability of technology infrastructure), prepared teachers (e.g. teacher standards for technology use in classrooms), relevant content (e.g. integration of digital literacy in the curriculum) and individual learning outcomes (e.g. minimum levels of proficiency in reading and mathematics). But education quality should also encompass social outcomes. It is not enough for students to be vessels receiving knowledge; they need to be able to use it to help achieve sustainable development in social, economic and environmental terms.

There are a variety of views on the extent to which digital technologies can enhance education quality. Some argue that, in principle, digital technology creates engaging learning environments, enlivens student experiences, simulates situations, facilitates collaboration and expands connections. But others say digital technology tends to support an individualized approach to education, reducing learners’ opportunities to socialize and learn by observing each other in real-life settings. Moreover, just as new technology overcomes some constraints, it brings its own problems. Increased screen time has been associated with adverse impact on physical and mental health. Insufficient regulation has led to unauthorized use of personal data for commercial purposes. Digital technology has also helped spread misinformation and hate speech, including through education.