Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a narrative essay | Example & tips

How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A narrative essay tells a story. In most cases, this is a story about a personal experience you had. This type of essay , along with the descriptive essay , allows you to get personal and creative, unlike most academic writing .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is a narrative essay for, choosing a topic, interactive example of a narrative essay, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about narrative essays.

When assigned a narrative essay, you might find yourself wondering: Why does my teacher want to hear this story? Topics for narrative essays can range from the important to the trivial. Usually the point is not so much the story itself, but the way you tell it.

A narrative essay is a way of testing your ability to tell a story in a clear and interesting way. You’re expected to think about where your story begins and ends, and how to convey it with eye-catching language and a satisfying pace.

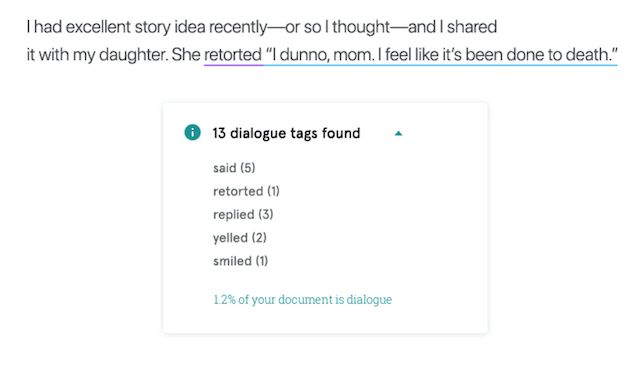

These skills are quite different from those needed for formal academic writing. For instance, in a narrative essay the use of the first person (“I”) is encouraged, as is the use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Narrative essay assignments vary widely in the amount of direction you’re given about your topic. You may be assigned quite a specific topic or choice of topics to work with.

- Write a story about your first day of school.

- Write a story about your favorite holiday destination.

You may also be given prompts that leave you a much wider choice of topic.

- Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself.

- Write about an achievement you are proud of. What did you accomplish, and how?

In these cases, you might have to think harder to decide what story you want to tell. The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to talk about a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

For example, a trip where everything went according to plan makes for a less interesting story than one where something unexpected happened that you then had to respond to. Choose an experience that might surprise the reader or teach them something.

Narrative essays in college applications

When applying for college , you might be asked to write a narrative essay that expresses something about your personal qualities.

For example, this application prompt from Common App requires you to respond with a narrative essay.

In this context, choose a story that is not only interesting but also expresses the qualities the prompt is looking for—here, resilience and the ability to learn from failure—and frame the story in a way that emphasizes these qualities.

An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt “Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself,” is shown below.

Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works.

Since elementary school, I have always favored subjects like science and math over the humanities. My instinct was always to think of these subjects as more solid and serious than classes like English. If there was no right answer, I thought, why bother? But recently I had an experience that taught me my academic interests are more flexible than I had thought: I took my first philosophy class.

Before I entered the classroom, I was skeptical. I waited outside with the other students and wondered what exactly philosophy would involve—I really had no idea. I imagined something pretty abstract: long, stilted conversations pondering the meaning of life. But what I got was something quite different.

A young man in jeans, Mr. Jones—“but you can call me Rob”—was far from the white-haired, buttoned-up old man I had half-expected. And rather than pulling us into pedantic arguments about obscure philosophical points, Rob engaged us on our level. To talk free will, we looked at our own choices. To talk ethics, we looked at dilemmas we had faced ourselves. By the end of class, I’d discovered that questions with no right answer can turn out to be the most interesting ones.

The experience has taught me to look at things a little more “philosophically”—and not just because it was a philosophy class! I learned that if I let go of my preconceptions, I can actually get a lot out of subjects I was previously dismissive of. The class taught me—in more ways than one—to look at things with an open mind.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you’re not given much guidance on what your narrative essay should be about, consider the context and scope of the assignment. What kind of story is relevant, interesting, and possible to tell within the word count?

The best kind of story for a narrative essay is one you can use to reflect on a particular theme or lesson, or that takes a surprising turn somewhere along the way.

Don’t worry too much if your topic seems unoriginal. The point of a narrative essay is how you tell the story and the point you make with it, not the subject of the story itself.

Narrative essays are usually assigned as writing exercises at high school or in university composition classes. They may also form part of a university application.

When you are prompted to tell a story about your own life or experiences, a narrative essay is usually the right response.

The key difference is that a narrative essay is designed to tell a complete story, while a descriptive essay is meant to convey an intense description of a particular place, object, or concept.

Narrative and descriptive essays both allow you to write more personally and creatively than other kinds of essays , and similar writing skills can apply to both.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Narrative Essay | Example & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/narrative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an expository essay, how to write a descriptive essay | example & tips, how to write your personal statement | strategies & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

The Ultimate Narrative Essay Guide for Beginners

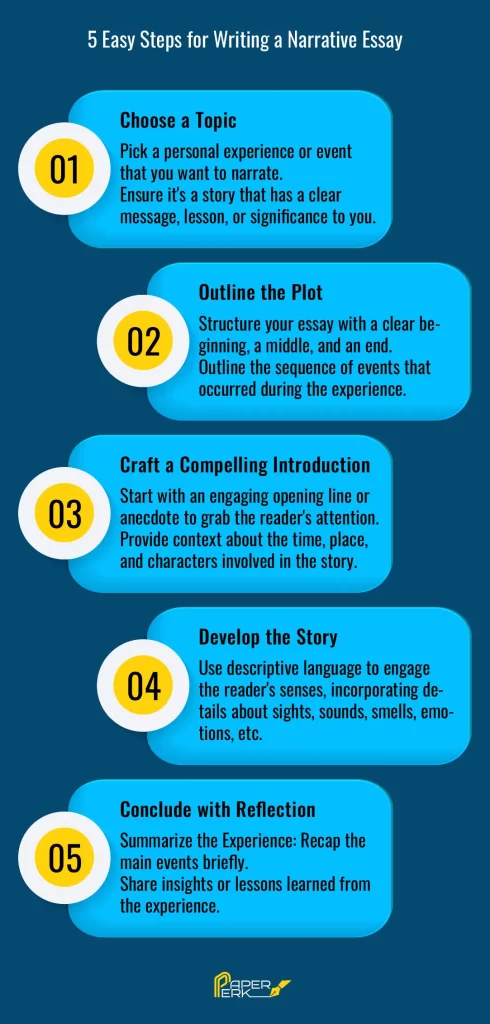

A narrative essay tells a story in chronological order, with an introduction that introduces the characters and sets the scene. Then a series of events leads to a climax or turning point, and finally a resolution or reflection on the experience.

Speaking of which, are you in sixes and sevens about narrative essays? Don’t worry this ultimate expert guide will wipe out all your doubts. So let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Everything You Need to Know About Narrative Essay

What is a narrative essay.

When you go through a narrative essay definition, you would know that a narrative essay purpose is to tell a story. It’s all about sharing an experience or event and is different from other types of essays because it’s more focused on how the event made you feel or what you learned from it, rather than just presenting facts or an argument. Let’s explore more details on this interesting write-up and get to know how to write a narrative essay.

Elements of a Narrative Essay

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements of a narrative essay:

A narrative essay has a beginning, middle, and end. It builds up tension and excitement and then wraps things up in a neat package.

Real people, including the writer, often feature in personal narratives. Details of the characters and their thoughts, feelings, and actions can help readers to relate to the tale.

It’s really important to know when and where something happened so we can get a good idea of the context. Going into detail about what it looks like helps the reader to really feel like they’re part of the story.

Conflict or Challenge

A story in a narrative essay usually involves some kind of conflict or challenge that moves the plot along. It could be something inside the character, like a personal battle, or something from outside, like an issue they have to face in the world.

Theme or Message

A narrative essay isn’t just about recounting an event – it’s about showing the impact it had on you and what you took away from it. It’s an opportunity to share your thoughts and feelings about the experience, and how it changed your outlook.

Emotional Impact

The author is trying to make the story they’re telling relatable, engaging, and memorable by using language and storytelling to evoke feelings in whoever’s reading it.

Narrative essays let writers have a blast telling stories about their own lives. It’s an opportunity to share insights and impart wisdom, or just have some fun with the reader. Descriptive language, sensory details, dialogue, and a great narrative voice are all essentials for making the story come alive.

The Purpose of a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is more than just a story – it’s a way to share a meaningful, engaging, and relatable experience with the reader. Includes:

Sharing Personal Experience

Narrative essays are a great way for writers to share their personal experiences, feelings, thoughts, and reflections. It’s an opportunity to connect with readers and make them feel something.

Entertainment and Engagement

The essay attempts to keep the reader interested by using descriptive language, storytelling elements, and a powerful voice. It attempts to pull them in and make them feel involved by creating suspense, mystery, or an emotional connection.

Conveying a Message or Insight

Narrative essays are more than just a story – they aim to teach you something. They usually have a moral lesson, a new understanding, or a realization about life that the author gained from the experience.

Building Empathy and Understanding

By telling their stories, people can give others insight into different perspectives, feelings, and situations. Sharing these tales can create compassion in the reader and help broaden their knowledge of different life experiences.

Inspiration and Motivation

Stories about personal struggles, successes, and transformations can be really encouraging to people who are going through similar situations. It can provide them with hope and guidance, and let them know that they’re not alone.

Reflecting on Life’s Significance

These essays usually make you think about the importance of certain moments in life or the impact of certain experiences. They make you look deep within yourself and ponder on the things you learned or how you changed because of those events.

Demonstrating Writing Skills

Coming up with a gripping narrative essay takes serious writing chops, like vivid descriptions, powerful language, timing, and organization. It’s an opportunity for writers to show off their story-telling abilities.

Preserving Personal History

Sometimes narrative essays are used to record experiences and special moments that have an emotional resonance. They can be used to preserve individual memories or for future generations to look back on.

Cultural and Societal Exploration

Personal stories can look at cultural or social aspects, giving us an insight into customs, opinions, or social interactions seen through someone’s own experience.

Format of a Narrative Essay

Narrative essays are quite flexible in terms of format, which allows the writer to tell a story in a creative and compelling way. Here’s a quick breakdown of the narrative essay format, along with some examples:

Introduction

Set the scene and introduce the story.

Engage the reader and establish the tone of the narrative.

Hook: Start with a captivating opening line to grab the reader’s attention. For instance:

Example: “The scorching sun beat down on us as we trekked through the desert, our water supply dwindling.”

Background Information: Provide necessary context or background without giving away the entire story.

Example: “It was the summer of 2015 when I embarked on a life-changing journey to…”

Thesis Statement or Narrative Purpose

Present the main idea or the central message of the essay.

Offer a glimpse of what the reader can expect from the narrative.

Thesis Statement: This isn’t as rigid as in other essays but can be a sentence summarizing the essence of the story.

Example: “Little did I know, that seemingly ordinary hike would teach me invaluable lessons about resilience and friendship.”

Body Paragraphs

Present the sequence of events in chronological order.

Develop characters, setting, conflict, and resolution.

Story Progression : Describe events in the order they occurred, focusing on details that evoke emotions and create vivid imagery.

Example : Detail the trek through the desert, the challenges faced, interactions with fellow hikers, and the pivotal moments.

Character Development : Introduce characters and their roles in the story. Show their emotions, thoughts, and actions.

Example : Describe how each character reacted to the dwindling water supply and supported each other through adversity.

Dialogue and Interactions : Use dialogue to bring the story to life and reveal character personalities.

Example : “Sarah handed me her last bottle of water, saying, ‘We’re in this together.'”

Reach the peak of the story, the moment of highest tension or significance.

Turning Point: Highlight the most crucial moment or realization in the narrative.

Example: “As the sun dipped below the horizon and hope seemed lost, a distant sound caught our attention—the rescue team’s helicopters.”

Provide closure to the story.

Reflect on the significance of the experience and its impact.

Reflection : Summarize the key lessons learned or insights gained from the experience.

Example : “That hike taught me the true meaning of resilience and the invaluable support of friendship in challenging times.”

Closing Thought : End with a memorable line that reinforces the narrative’s message or leaves a lasting impression.

Example : “As we boarded the helicopters, I knew this adventure would forever be etched in my heart.”

Example Summary:

Imagine a narrative about surviving a challenging hike through the desert, emphasizing the bonds formed and lessons learned. The narrative essay structure might look like starting with an engaging scene, narrating the hardships faced, showcasing the characters’ resilience, and culminating in a powerful realization about friendship and endurance.

Different Types of Narrative Essays

There are a bunch of different types of narrative essays – each one focuses on different elements of storytelling and has its own purpose. Here’s a breakdown of the narrative essay types and what they mean.

Personal Narrative

Description : Tells a personal story or experience from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Reflects on personal growth, lessons learned, or significant moments.

Example of Narrative Essay Types:

Topic : “The Day I Conquered My Fear of Public Speaking”

Focus: Details the experience, emotions, and eventual triumph over a fear of public speaking during a pivotal event.

Descriptive Narrative

Description : Emphasizes vivid details and sensory imagery.

Purpose : Creates a sensory experience, painting a vivid picture for the reader.

Topic : “A Walk Through the Enchanted Forest”

Focus : Paints a detailed picture of the sights, sounds, smells, and feelings experienced during a walk through a mystical forest.

Autobiographical Narrative

Description: Chronicles significant events or moments from the writer’s life.

Purpose: Provides insights into the writer’s life, experiences, and growth.

Topic: “Lessons from My Childhood: How My Grandmother Shaped Who I Am”

Focus: Explores pivotal moments and lessons learned from interactions with a significant family member.

Experiential Narrative

Description: Relays experiences beyond the writer’s personal life.

Purpose: Shares experiences, travels, or events from a broader perspective.

Topic: “Volunteering in a Remote Village: A Journey of Empathy”

Focus: Chronicles the writer’s volunteering experience, highlighting interactions with a community and personal growth.

Literary Narrative

Description: Incorporates literary elements like symbolism, allegory, or thematic explorations.

Purpose: Uses storytelling for deeper explorations of themes or concepts.

Topic: “The Symbolism of the Red Door: A Journey Through Change”

Focus: Uses a red door as a symbol, exploring its significance in the narrator’s life and the theme of transition.

Historical Narrative

Description: Recounts historical events or periods through a personal lens.

Purpose: Presents history through personal experiences or perspectives.

Topic: “A Grandfather’s Tales: Living Through the Great Depression”

Focus: Shares personal stories from a family member who lived through a historical era, offering insights into that period.

Digital or Multimedia Narrative

Description: Incorporates multimedia elements like images, videos, or audio to tell a story.

Purpose: Explores storytelling through various digital platforms or formats.

Topic: “A Travel Diary: Exploring Europe Through Vlogs”

Focus: Combines video clips, photos, and personal narration to document a travel experience.

How to Choose a Topic for Your Narrative Essay?

Selecting a compelling topic for your narrative essay is crucial as it sets the stage for your storytelling. Choosing a boring topic is one of the narrative essay mistakes to avoid . Here’s a detailed guide on how to choose the right topic:

Reflect on Personal Experiences

- Significant Moments:

Moments that had a profound impact on your life or shaped your perspective.

Example: A moment of triumph, overcoming a fear, a life-changing decision, or an unforgettable experience.

- Emotional Resonance:

Events that evoke strong emotions or feelings.

Example: Joy, fear, sadness, excitement, or moments of realization.

- Lessons Learned:

Experiences that taught you valuable lessons or brought about personal growth.

Example: Challenges that led to personal development, shifts in mindset, or newfound insights.

Explore Unique Perspectives

- Uncommon Experiences:

Unique or unconventional experiences that might captivate the reader’s interest.

Example: Unusual travels, interactions with different cultures, or uncommon hobbies.

- Different Points of View:

Stories from others’ perspectives that impacted you deeply.

Example: A family member’s story, a friend’s experience, or a historical event from a personal lens.

Focus on Specific Themes or Concepts

- Themes or Concepts of Interest:

Themes or ideas you want to explore through storytelling.

Example: Friendship, resilience, identity, cultural diversity, or personal transformation.

- Symbolism or Metaphor:

Using symbols or metaphors as the core of your narrative.

Example: Exploring the symbolism of an object or a place in relation to a broader theme.

Consider Your Audience and Purpose

- Relevance to Your Audience:

Topics that resonate with your audience’s interests or experiences.

Example: Choose a relatable theme or experience that your readers might connect with emotionally.

- Impact or Message:

What message or insight do you want to convey through your story?

Example: Choose a topic that aligns with the message or lesson you aim to impart to your readers.

Brainstorm and Evaluate Ideas

- Free Writing or Mind Mapping:

Process: Write down all potential ideas without filtering. Mind maps or free-writing exercises can help generate diverse ideas.

- Evaluate Feasibility:

The depth of the story, the availability of vivid details, and your personal connection to the topic.

Imagine you’re considering topics for a narrative essay. You reflect on your experiences and decide to explore the topic of “Overcoming Stage Fright: How a School Play Changed My Perspective.” This topic resonates because it involves a significant challenge you faced and the personal growth it brought about.

Narrative Essay Topics

50 easy narrative essay topics.

- Learning to Ride a Bike

- My First Day of School

- A Surprise Birthday Party

- The Day I Got Lost

- Visiting a Haunted House

- An Encounter with a Wild Animal

- My Favorite Childhood Toy

- The Best Vacation I Ever Had

- An Unforgettable Family Gathering

- Conquering a Fear of Heights

- A Special Gift I Received

- Moving to a New City

- The Most Memorable Meal

- Getting Caught in a Rainstorm

- An Act of Kindness I Witnessed

- The First Time I Cooked a Meal

- My Experience with a New Hobby

- The Day I Met My Best Friend

- A Hike in the Mountains

- Learning a New Language

- An Embarrassing Moment

- Dealing with a Bully

- My First Job Interview

- A Sporting Event I Attended

- The Scariest Dream I Had

- Helping a Stranger

- The Joy of Achieving a Goal

- A Road Trip Adventure

- Overcoming a Personal Challenge

- The Significance of a Family Tradition

- An Unusual Pet I Owned

- A Misunderstanding with a Friend

- Exploring an Abandoned Building

- My Favorite Book and Why

- The Impact of a Role Model

- A Cultural Celebration I Participated In

- A Valuable Lesson from a Teacher

- A Trip to the Zoo

- An Unplanned Adventure

- Volunteering Experience

- A Moment of Forgiveness

- A Decision I Regretted

- A Special Talent I Have

- The Importance of Family Traditions

- The Thrill of Performing on Stage

- A Moment of Sudden Inspiration

- The Meaning of Home

- Learning to Play a Musical Instrument

- A Childhood Memory at the Park

- Witnessing a Beautiful Sunset

Narrative Essay Topics for College Students

- Discovering a New Passion

- Overcoming Academic Challenges

- Navigating Cultural Differences

- Embracing Independence: Moving Away from Home

- Exploring Career Aspirations

- Coping with Stress in College

- The Impact of a Mentor in My Life

- Balancing Work and Studies

- Facing a Fear of Public Speaking

- Exploring a Semester Abroad

- The Evolution of My Study Habits

- Volunteering Experience That Changed My Perspective

- The Role of Technology in Education

- Finding Balance: Social Life vs. Academics

- Learning a New Skill Outside the Classroom

- Reflecting on Freshman Year Challenges

- The Joys and Struggles of Group Projects

- My Experience with Internship or Work Placement

- Challenges of Time Management in College

- Redefining Success Beyond Grades

- The Influence of Literature on My Thinking

- The Impact of Social Media on College Life

- Overcoming Procrastination

- Lessons from a Leadership Role

- Exploring Diversity on Campus

- Exploring Passion for Environmental Conservation

- An Eye-Opening Course That Changed My Perspective

- Living with Roommates: Challenges and Lessons

- The Significance of Extracurricular Activities

- The Influence of a Professor on My Academic Journey

- Discussing Mental Health in College

- The Evolution of My Career Goals

- Confronting Personal Biases Through Education

- The Experience of Attending a Conference or Symposium

- Challenges Faced by Non-Native English Speakers in College

- The Impact of Traveling During Breaks

- Exploring Identity: Cultural or Personal

- The Impact of Music or Art on My Life

- Addressing Diversity in the Classroom

- Exploring Entrepreneurial Ambitions

- My Experience with Research Projects

- Overcoming Impostor Syndrome in College

- The Importance of Networking in College

- Finding Resilience During Tough Times

- The Impact of Global Issues on Local Perspectives

- The Influence of Family Expectations on Education

- Lessons from a Part-Time Job

- Exploring the College Sports Culture

- The Role of Technology in Modern Education

- The Journey of Self-Discovery Through Education

Narrative Essay Comparison

Narrative essay vs. descriptive essay.

Here’s our first narrative essay comparison! While both narrative and descriptive essays focus on vividly portraying a subject or an event, they differ in their primary objectives and approaches. Now, let’s delve into the nuances of comparison on narrative essays.

Narrative Essay:

Storytelling: Focuses on narrating a personal experience or event.

Chronological Order: Follows a structured timeline of events to tell a story.

Message or Lesson: Often includes a central message, moral, or lesson learned from the experience.

Engagement: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling storyline and character development.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, using “I” and expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a plot with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Focuses on describing characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Conflict or Challenge: Usually involves a central conflict or challenge that drives the narrative forward.

Dialogue: Incorporates conversations to bring characters and their interactions to life.

Reflection: Concludes with reflection or insight gained from the experience.

Descriptive Essay:

Vivid Description: Aims to vividly depict a person, place, object, or event.

Imagery and Details: Focuses on sensory details to create a vivid image in the reader’s mind.

Emotion through Description: Uses descriptive language to evoke emotions and engage the reader’s senses.

Painting a Picture: Creates a sensory-rich description allowing the reader to visualize the subject.

Imagery and Sensory Details: Focuses on providing rich sensory descriptions, using vivid language and adjectives.

Point of Focus: Concentrates on describing a specific subject or scene in detail.

Spatial Organization: Often employs spatial organization to describe from one area or aspect to another.

Objective Observations: Typically avoids the use of personal opinions or emotions; instead, the focus remains on providing a detailed and objective description.

Comparison:

Focus: Narrative essays emphasize storytelling, while descriptive essays focus on vividly describing a subject or scene.

Perspective: Narrative essays are often written from a first-person perspective, while descriptive essays may use a more objective viewpoint.

Purpose: Narrative essays aim to convey a message or lesson through a story, while descriptive essays aim to paint a detailed picture for the reader without necessarily conveying a specific message.

Narrative Essay vs. Argumentative Essay

The narrative essay and the argumentative essay serve distinct purposes and employ different approaches:

Engagement and Emotion: Aims to captivate the reader through a compelling story.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience or lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s point of view, sharing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Emphasizes a storyline with a beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Message or Lesson: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Argumentative Essay:

Persuasion and Argumentation: Aims to persuade the reader to adopt the writer’s viewpoint on a specific topic.

Logical Reasoning: Presents evidence, facts, and reasoning to support a particular argument or stance.

Debate and Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and counter them with evidence and reasoning.

Thesis Statement: Includes a clear thesis statement that outlines the writer’s position on the topic.

Thesis and Evidence: Starts with a strong thesis statement and supports it with factual evidence, statistics, expert opinions, or logical reasoning.

Counterarguments: Addresses opposing viewpoints and provides rebuttals with evidence.

Logical Structure: Follows a logical structure with an introduction, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, and a conclusion reaffirming the thesis.

Formal Language: Uses formal language and avoids personal anecdotes or emotional appeals.

Objective: Argumentative essays focus on presenting a logical argument supported by evidence, while narrative essays prioritize storytelling and personal reflection.

Purpose: Argumentative essays aim to persuade and convince the reader of a particular viewpoint, while narrative essays aim to engage, entertain, and share personal experiences.

Structure: Narrative essays follow a storytelling structure with character development and plot, while argumentative essays follow a more formal, structured approach with logical arguments and evidence.

In essence, while both essays involve writing and presenting information, the narrative essay focuses on sharing a personal experience, whereas the argumentative essay aims to persuade the audience by presenting a well-supported argument.

Narrative Essay vs. Personal Essay

While there can be an overlap between narrative and personal essays, they have distinctive characteristics:

Storytelling: Emphasizes recounting a specific experience or event in a structured narrative form.

Engagement through Story: Aims to engage the reader through a compelling story with characters, plot, and a central theme or message.

Reflective: Often includes reflection on the significance of the experience and the lessons learned.

First-Person Perspective: Typically narrated from the writer’s viewpoint, expressing personal emotions and thoughts.

Plot Development: Focuses on developing a storyline with a clear beginning, middle, climax, and resolution.

Character Development: Includes descriptions of characters, their interactions, emotions, and growth.

Central Message: Conveys a central message, moral, or insight derived from the experience.

Personal Essay:

Exploration of Ideas or Themes: Explores personal ideas, opinions, or reflections on a particular topic or subject.

Expression of Thoughts and Opinions: Expresses the writer’s thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on a specific subject matter.

Reflection and Introspection: Often involves self-reflection and introspection on personal experiences, beliefs, or values.

Varied Structure and Content: Can encompass various forms, including memoirs, personal anecdotes, or reflections on life experiences.

Flexibility in Structure: Allows for diverse structures and forms based on the writer’s intent, which could be narrative-like or more reflective.

Theme-Centric Writing: Focuses on exploring a central theme or idea, with personal anecdotes or experiences supporting and illustrating the theme.

Expressive Language: Utilizes descriptive and expressive language to convey personal perspectives, emotions, and opinions.

Focus: Narrative essays primarily focus on storytelling through a structured narrative, while personal essays encompass a broader range of personal expression, which can include storytelling but isn’t limited to it.

Structure: Narrative essays have a more structured plot development with characters and a clear sequence of events, while personal essays might adopt various structures, focusing more on personal reflection, ideas, or themes.

Intent: While both involve personal experiences, narrative essays emphasize telling a story with a message or lesson learned, while personal essays aim to explore personal thoughts, feelings, or opinions on a broader range of topics or themes.

A narrative essay is more than just telling a story. It’s also meant to engage the reader, get them thinking, and leave a lasting impact. Whether it’s to amuse, motivate, teach, or reflect, these essays are a great way to communicate with your audience. This interesting narrative essay guide was all about letting you understand the narrative essay, its importance, and how can you write one.

Order Original Papers & Essays

Your First Custom Paper Sample is on Us!

Timely Deliveries

No Plagiarism & AI

100% Refund

Try Our Free Paper Writing Service

Related blogs.

Connections with Writers and support

Privacy and Confidentiality Guarantee

Average Quality Score

When writers set down the facts of their lives into a compelling story , they’re writing a narrative essay. Personal narrative essays explore the events of the writer’s own life, and by crafting a nonfiction piece that resonates as storytelling, the essayist can uncover deeper truths in the world.

Narrative essays weave the author’s factual lived experiences into a compelling story.

So, what is a narrative essay? Whether you’re writing for college applications or literary journals , this article separates fact from fiction. We’ll look at how to write a narrative essay through a step-by-step process, including a look at narrative essay topics and outlines. We’ll also analyze some successful narrative essay examples.

Learn how to tell your story, your way. Let’s dive into this exciting genre!

What is a Narrative Essay?

The narrative essay is a branch of creative nonfiction . Also known as a personal essay, writers of this genre are tasked with telling honest stories about their lived experiences and, as a result, arriving at certain realizations about life.

Think of personal narrative essays as nonfiction short stories . While the essay and the short story rely on different writing techniques, they arrive at similar outcomes: a powerful story with an idea, theme , or moral that the reader can interpret for themselves.

Now, if you haven’t written a narrative essay before, you might associate the word “essay” with high school English class. Remember those tedious 5-paragraph essays we had to write, on the topic of some book we barely read, about subject matter that didn’t interest us?

Don’t worry—that’s not the kind of essay we’re talking about. The word essay comes from the French essayer , which means “to try.” That’s exactly what writing a narrative essay is: an attempt at organizing the real world into language—a journey of making meaning from the chaos of life.

Narrative essays work to surface meaning from lived experience.

Narrative Essay Example

A great narrative essay example is the piece “Flow” by Mary Oliver, which you can read for free in Google Books .

The essay dwells on, as Mary Oliver puts it, the fact that “we live in paradise.” At once both an ode to nature and an urge to love it fiercely, Oliver explores our place in the endless beauty of the world.

Throughout the essay, Oliver weaves in her thoughts about the world, from nature’s noble beauty to the question “What is the life I should live?” Yet these thoughts, however profound, are not the bulk of the essay. Rather, she arrives at these thoughts via anecdotes and observations: the migration of whales, the strings of fish at high tide, the inventive rescue of a spiny fish from the waterless shore, etc.

What is most profound about this essay, and perhaps most amusing, is that it ends with Oliver’s questions about how to live life. And yet, the stories she tells show us exactly how to live life: with care for the world; with admiration; with tenderness towards all of life and its superb, mysterious, seemingly-random beauty.

Such is the power of the narrative essay. By examining the random facts of our lives, we can come to great conclusions.

What do most essays have in common? Let’s look at the fundamentals of the essay, before diving into more narrative essay examples.

Narrative Essay Definition: 5 Fundamentals

The personal narrative essay has a lot of room for experimentation. We’ll dive into those opportunities in a bit, but no matter the form, most essays share these five fundamentals.

- Personal experience

- Meaning from chaos

- The use of literary devices

Let’s explore these fundamentals in depth.

All narrative essays have a thesis statement. However, this isn’t the formulaic thesis statement you had to write in school: you don’t need to map out your argument with painstaking specificity, you need merely to tell the reader what you’re writing about.

Take the aforementioned essay by Mary Oliver. Her thesis is this: “How can we not know that, already, we live in paradise?”

It’s a simple yet provocative statement. By posing her thesis as a question, she challenges us to consider why we might not treat this earth as paradise. She then delves into her own understanding of this paradise, providing relevant stories and insights as to how the earth should be treated.

Now, be careful with abstract statements like this. Mary Oliver is a master of language, so she’s capable of creating a thesis statement out of an abstract idea and building a beautiful essay. But concrete theses are also welcome: you should compel the reader forward with the central argument of your work, without confusing them or leading them astray.

You should compel the reader forward with the central argument of your work, without confusing them or leading them astray

2. Personal Experience

The personal narrative essay is, shockingly, about personal experience. But how do writers distill their experiences into meaningful stories?

There are a few techniques writers have at their disposal. Perhaps the most common of these techniques is called braiding . Rather than focusing on one continuous story, the writer can “braid” different stories, weaving in and out of different narratives and finding common threads between them. Often, the subject matter of the essay will require more than one anecdote as evidence, and braiding helps the author uphold their thesis while showing instead of telling .

Another important consideration is how you tell your story . Essayists should consider the same techniques that fiction writers use. Give ample consideration to your essay’s setting , word choice , point of view , and dramatic structure . The narrative essay is, after all, a narrative, so tell your story how it deserves to be told.

3. Meaning from Chaos

Life, I think we can agree, is chaotic. While we can trace the events of our lives through cause and effect, A leads to B leads to C, the truth is that so much of our lives are shaped through circumstances beyond our control.

The narrative essay is a way to reclaim some of that control. By distilling the facts of our lives into meaningful narratives, we can uncover deeper truths that we didn’t realize existed.

By distilling the facts of our lives into meaningful narratives, we can uncover deeper truths that we didn’t realize existed.

Consider the essay “ Only Daughter ” by Sandra Cisneros. It’s a brief read, but it covers a lot of different events: a lonesome childhood, countless moves, university education, and the trials and tribulations of a successful writing career.

Coupled with Cisneros’ musings on culture and gender roles, there’s a lot of life to distill in these three pages. Yet Cisneros does so masterfully. By organizing these life events around her thesis statement of being an only daughter, Cisneros finds meaning in the many disparate events she describes.

As you go about writing a narrative essay, you will eventually encounter moments of insight . Insight describes those “aha!” moments in the work—places in which you come to deeper realizations about your life, the lives of others, and the world at large.

Now, insight doesn’t need to be some massive, culture-transforming realization. Many moments of insight are found in small interactions and quiet moments.

For example, In the above essay by Sandra Cisneros, her moments of insight come from connecting her upbringing to her struggle as an only daughter. While her childhood was often lonely and disappointing, she realizes in hindsight that she’s lucky for that upbringing: it helped nurture her spirit as a writer, and it helped her pursue a career in writing. These moments of gratitude work as insight, allowing her to appreciate what once seemed like a burden.

When we reach the end of the essay, and Cisneros describes how she felt when her father read one of her stories, we see what this gratitude is building towards: love and acceptance for the life she chose.

5. Literary Devices

The personal narrative essay, as well as all forms of creative writing, uses its fair share of literary devices . These devices don’t need to be complex: you don’t need a sprawling extended metaphor or an intricate set of juxtapositions to make your essay compelling.

However, the occasional symbol or metaphor will certainly aid your story. In Mary Oliver’s essay “Flow,” the author uses literary devices to describe the magnificence of the ocean, calling it a “cauldron of changing greens and blues” and “the great palace of the earth.” These descriptions reinforce the deep beauty of the earth.

In Sandra Cisneros’ essay “Only Daughter,” the author employs different symbols to represent her father’s masculinity and sense of gender roles. At one point, she lists the few things he reads—sports journals, slasher magazines, and picture paperbacks, often depicting scenes of violence against women. These symbols represent the divide between her father’s gendered thinking and her own literary instincts.

More Narrative Essay Examples

Let’s take a look at a few more narrative essay examples. We’ll dissect each essay based on the five fundamentals listed above.

Narrative Essay Example: “Letting Go” by David Sedaris

Read “Letting Go” here in The New Yorker .

Sedaris’ essay dwells on the culture of cigarette smoking—how it starts, the world it builds, and the difficulties in quitting. Let’s analyze how this narrative essay example uses the five fundamentals of essay writing.

- Thesis: There isn’t an explicitly defined thesis, which is common for essays that are meant to be humorous or entertaining. However, this sentence is a plausible thesis statement: “It wasn’t the smoke but the smell of it that bothered me. In later years, I didn’t care so much, but at the time I found it depressing: the scent of neglect.”

- Personal Experience: Sedaris moves between many different anecdotes about smoking, from his family’s addiction to cigarettes to his own dependence. We learn about his moving around for cheaper smokes, his family’s struggle to quit, and the last cigarette he smoked in the Charles de Gaulle airport.

- Meaning from Chaos: Sedaris ties many disparate events together. We learn about his childhood and his smoking years, but these are interwoven with anecdotes about his family and friends. What emerges is a narrative about the allure of smoking.

- Insight: Two parts of this essay are especially poignant. One, when Sedaris describes his mother’s realization that smoking isn’t sophisticated, and soon quits her habit entirely. Two, when Sedaris is given the diseased lung of a chain smoker, and instead of thinking about his own lungs, he’s simply surprised at how heavy the lung is.

- Literary Devices: Throughout the essay, Sedaris demonstrates how the cigarette symbolizes neglect: neglect of one’s body, one’s space, and one’s self-presentation.

Narrative Essay Example: “My Mother’s Tongue” by Zavi Kang Engles

Read “My Mother’s Tongue” here in The Rumpus .

Engles’ essay examines the dysphoria of growing up between two vastly different cultures and languages. By asserting the close bond between Korean language and culture, Engles explores the absurdities of growing up as a child of Korean immigrants. Let’s analyze how this narrative essay example uses the five fundamentals of essay writing.

- Thesis: Engles’ essay often comes back to her relationship with the Korean language, especially as it relates to other Korean speakers. This relationship is best highlighted when she writes “I glowed with [my mother’s] love, basked in the warm security of what I thought was a language between us. Perhaps this is why strangers asked for our photos, in an attempt to capture a secret world between two people.”This “secret world” forms the crux of her essay, charting not only how Korean-Americans might exist in relation to one another, but also how Engles’ language is strongly tied to her identity and homeland.

- Personal Experience: Engles writes about her childhood attachment to both English and Korean, her adolescent fallout with the Korean language, her experiences as “not American enough” in the United States and “not Korean enough” in Korea, and her experiences mourning in a Korean hospital.

- Meaning from Chaos: In addition to the above events, Engles ties in research about language and identity (also known as code switching ). Through language and identity, the essay charts the two different cultures that the author stands between, highlighting the dissonance between Western individualism and an Eastern sense of belonging.

- Insight: There are many examples of insight throughout this essay as the author explores how out of place she feels, torn between two countries. An especially poignant example comes from Engles’ experience in a Korean hospital, where she writes “I didn’t know how to mourn in this country.”

- Literary Devices: The essay frequently juxtaposes the languages and cultures of Korea and the United States. Additionally, the English language comes to symbolize Western individualism, while the Korean language comes to symbolize Eastern collectivism.

Narrative Essay Example: 3 Rules for Middle-Age Happiness by Deborah Copaken

Read “3 Rules for Middle-Age Happiness” here in The Atlantic .

Copaken’s essay explores her relationship to Nora Ephron, the screenwriter for When Harry Met Sally . Let’s analyze how this narrative essay example uses the five fundamentals of essay writing.

- Thesis: This essay hands us the thesis statement in its subtitle: “Gather friends and feed them, laugh in the face of calamity, and cut out all the things—people, jobs, body parts—that no longer serve you.”

- Personal Experience: Copaken weaves two different threads through this essay. One thread is her personal life, including a failing marriage, medical issues, and her attempts at building a happy family. The other is Copaken’s personal relationship to Ephron, whose advice coincides with many of the essay’s insights.

- Meaning from Chaos: This essay organizes its events chronologically. However, the main sense of organization is found in the title: many of the essayist’s problems can be perceived as middle-aged crises (family trouble, divorce, death of loved ones), but the solutions to those crises are simpler than one might realize.

- Insight: In writing this essay, Copaken explores her relationship to Ephron, as well as Copaken’s own relationship to her children. She ties these experiences together at the end, when she writes “The transmission of woes is a one-way street, from child to mother. A good mother doesn’t burden her children with her pain. She waits until it becomes so heavy, it either breaks her or kills her, whichever comes first.”

- Literary Devices: The literary devices in this article explore the author’s relationship to womanhood. She wonders if having a hysterectomy will make her “like less of a woman.” Also important is the fact that, when the author has her hysterectomy, her daughter has her first period. Copaken uses this to symbolize the passing of womanhood from mother to daughter, which helps bring her to the above insight.

How to Write a Narrative Essay in 5 Steps

No matter the length or subject matter, writing a narrative essay is as easy as these five steps.

1. Generating Narrative Essay Ideas

If you’re not sure what to write about, you’ll want to generate some narrative essay ideas. One way to do this is to look for writing prompts online: Reedsy adds new prompts to their site every week, and we also post writing prompts every Wednesday to our Facebook group .

Taking a step back, it helps to simply think about formative moments in your life. You might a great idea from answering one of these questions:

- When did something alter my worldview, personal philosophy, or political beliefs?

- Who has given me great advice, or helped me lead a better life?

- What moment of adversity did I overcome and grow stronger from?

- What is something that I believe to be very important, that I want other people to value as well?

- What life event of mine do I not yet fully understand?

- What is something I am constantly striving for?

- What is something I’ve taken for granted, but am now grateful for?

Finally, you might be interested in the advice at our article How to Come Up with Story Ideas . The article focuses on fiction writers, but essayists can certainly benefit from these tips as well.

2. Drafting a Narrative Essay Outline

Once you have an idea, you’ll want to flesh it out in a narrative essay outline.

Your outline can be as simple or as complex as you’d like, and it all depends on how long you intend your essay to be. A simple outline can include the following:

- Introduction—usually a relevant anecdote that excites or entices the reader.

- Event 1: What story will I use to uphold my argument?

- Analysis 1: How does this event serve as evidence for my thesis?

- Conclusion: How can I tie these events together? What do they reaffirm about my thesis? And what advice can I then impart on the reader, if any?

One thing that’s missing from this outline is insight. That’s because insight is often unplanned: you realize it as you write it, and the best insight comes naturally to the writer. However, if you already know the insight you plan on sharing, it will fit best within the analysis for your essay, and/or in the essay’s conclusion.

Insight is often unplanned: you realize it as you write it, and the best insight comes naturally to the writer.

Another thing that’s missing from this is research. If you plan on intertwining your essay with research (which many essayists should do!), consider adding that research as its own bullet point under each heading.

For a different, more fiction-oriented approach to outlining, check out our article How to Write a Story Outline .

3. Starting with a Story

Now, let’s tackle the hardest question: how to start a narrative essay?

Most narrative essays begin with a relevant story. You want to draw the reader in right away, offering something that surprises or interests them. And, since the essay is about you and your lived experiences, it makes sense to start your essay with a relevant anecdote.

Think about a story that’s relevant to your thesis, and experiment with ways to tell this story. You can start with a surprising bit of dialogue , an unusual situation you found yourself in, or a beautiful setting. You can also lead your essay with research or advice, but be sure to tie that in with an anecdote quickly, or else your reader might not know where your essay is going.

For examples of this, take a look at any of the narrative essay examples we’ve used in this article.

Theoretically, your thesis statement can go anywhere in the essay. You may have noticed in the previous examples that the thesis statement isn’t always explicit or immediate: sometimes it shows up towards the center of the essay, and sometimes it’s more implied than stated directly.

You can experiment with the placement of your thesis, but if you place your thesis later in the essay, make sure that everything before the thesis is intriguing to the reader. If the reader feels like the essay is directionless or boring, they won’t have a reason to reach your thesis, nor will they understand the argument you’re making.

4. Getting to the Core Truth

With an introduction and a thesis underway, continue writing about your experiences, arguments, and research. Be sure to follow the structure you’ve sketched in your outline, but feel free to deviate from this outline if something more natural occurs to you.

Along the way, you will end up explaining why your experiences matter to the reader. Here is where you can start generating insight. Insight can take the form of many things, but the focus is always to reach a core truth.

Insight might take the following forms:

- Realizations from connecting the different events in your life.

- Advice based on your lived mistakes and experiences.

- Moments where you change your ideas or personal philosophy.

- Richer understandings about life, love, a higher power, the universe, etc.

5. Relentless Editing

With a first draft of your narrative essay written, you can make your essay sparkle in the editing process.

Remember, a first draft doesn’t have to be perfect, it just needs to exist.

Remember, a first draft doesn’t have to be perfect, it just needs to exist. Here are some things to focus on in the editing process:

- Clarity: Does every argument make sense? Do my ideas flow logically? Are my stories clear and easy to follow?

- Structure: Does the procession of ideas make sense? Does everything uphold my thesis? Do my arguments benefit from the way they’re laid out in this essay?

- Style: Do the words flow when I read them? Do I have a good mix of long and short sentences? Have I omitted any needless words ?

- Literary Devices: Do I use devices like similes, metaphors, symbols, or juxtaposition? Do these devices help illustrate my ideas?

- Mechanics: Is every word spelled properly? Do I use the right punctuation? If I’m submitting this essay somewhere, does it follow the formatting guidelines?

Your essay can undergo any number of revisions before it’s ready. Above all, make sure that your narrative essay is easy to follow, every word you use matters, and that you come to a deeper understanding about your own life.

Above all, make sure that your narrative essay is easy to follow, every word you use matters, and that you come to a deeper understanding about your own life.

Next Steps for Narrative Essayists

When you have a completed essay, what’s next? You might be interested in submitting to some literary journals . Here’s 24 literary journals you can submit to—we hope you find a great home for your writing!

If you’re looking for additional feedback on your work, feel free to join our Facebook group . You can also take a look at our upcoming nonfiction courses , where you’ll learn the fundamentals of essay writing and make your story even more compelling.

Writing a narrative essay isn’t easy, but you’ll find that the practice can be very rewarding. You’ll learn about your lived experiences, come to deeper conclusions about your personal philosophies, and perhaps even challenge the way you approach life. So find some paper, choose a topic, and get writing—the world is waiting for your story!

Sean Glatch

Thanks for a superbly efficient and informative article…

We’re glad it was helpful, Mary!

Very helpful,, Thanks!!!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 great narrative essay examples + tips for writing.

General Education

A narrative essay is one of the most intimidating assignments you can be handed at any level of your education. Where you've previously written argumentative essays that make a point or analytic essays that dissect meaning, a narrative essay asks you to write what is effectively a story .

But unlike a simple work of creative fiction, your narrative essay must have a clear and concrete motif —a recurring theme or idea that you’ll explore throughout. Narrative essays are less rigid, more creative in expression, and therefore pretty different from most other essays you’ll be writing.

But not to fear—in this article, we’ll be covering what a narrative essay is, how to write a good one, and also analyzing some personal narrative essay examples to show you what a great one looks like.

What Is a Narrative Essay?

At first glance, a narrative essay might sound like you’re just writing a story. Like the stories you're used to reading, a narrative essay is generally (but not always) chronological, following a clear throughline from beginning to end. Even if the story jumps around in time, all the details will come back to one specific theme, demonstrated through your choice in motifs.

Unlike many creative stories, however, your narrative essay should be based in fact. That doesn’t mean that every detail needs to be pure and untainted by imagination, but rather that you shouldn’t wholly invent the events of your narrative essay. There’s nothing wrong with inventing a person’s words if you can’t remember them exactly, but you shouldn’t say they said something they weren’t even close to saying.

Another big difference between narrative essays and creative fiction—as well as other kinds of essays—is that narrative essays are based on motifs. A motif is a dominant idea or theme, one that you establish before writing the essay. As you’re crafting the narrative, it’ll feed back into your motif to create a comprehensive picture of whatever that motif is.

For example, say you want to write a narrative essay about how your first day in high school helped you establish your identity. You might discuss events like trying to figure out where to sit in the cafeteria, having to describe yourself in five words as an icebreaker in your math class, or being unsure what to do during your lunch break because it’s no longer acceptable to go outside and play during lunch. All of those ideas feed back into the central motif of establishing your identity.

The important thing to remember is that while a narrative essay is typically told chronologically and intended to read like a story, it is not purely for entertainment value. A narrative essay delivers its theme by deliberately weaving the motifs through the events, scenes, and details. While a narrative essay may be entertaining, its primary purpose is to tell a complete story based on a central meaning.

Unlike other essay forms, it is totally okay—even expected—to use first-person narration in narrative essays. If you’re writing a story about yourself, it’s natural to refer to yourself within the essay. It’s also okay to use other perspectives, such as third- or even second-person, but that should only be done if it better serves your motif. Generally speaking, your narrative essay should be in first-person perspective.

Though your motif choices may feel at times like you’re making a point the way you would in an argumentative essay, a narrative essay’s goal is to tell a story, not convince the reader of anything. Your reader should be able to tell what your motif is from reading, but you don’t have to change their mind about anything. If they don’t understand the point you are making, you should consider strengthening the delivery of the events and descriptions that support your motif.

Narrative essays also share some features with analytical essays, in which you derive meaning from a book, film, or other media. But narrative essays work differently—you’re not trying to draw meaning from an existing text, but rather using an event you’ve experienced to convey meaning. In an analytical essay, you examine narrative, whereas in a narrative essay you create narrative.

The structure of a narrative essay is also a bit different than other essays. You’ll generally be getting your point across chronologically as opposed to grouping together specific arguments in paragraphs or sections. To return to the example of an essay discussing your first day of high school and how it impacted the shaping of your identity, it would be weird to put the events out of order, even if not knowing what to do after lunch feels like a stronger idea than choosing where to sit. Instead of organizing to deliver your information based on maximum impact, you’ll be telling your story as it happened, using concrete details to reinforce your theme.

3 Great Narrative Essay Examples

One of the best ways to learn how to write a narrative essay is to look at a great narrative essay sample. Let’s take a look at some truly stellar narrative essay examples and dive into what exactly makes them work so well.

A Ticket to the Fair by David Foster Wallace

Today is Press Day at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, and I’m supposed to be at the fairgrounds by 9:00 A.M. to get my credentials. I imagine credentials to be a small white card in the band of a fedora. I’ve never been considered press before. My real interest in credentials is getting into rides and shows for free. I’m fresh in from the East Coast, for an East Coast magazine. Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish. I think they asked me to do this because I grew up here, just a couple hours’ drive from downstate Springfield. I never did go to the state fair, though—I pretty much topped out at the county fair level. Actually, I haven’t been back to Illinois for a long time, and I can’t say I’ve missed it.

Throughout this essay, David Foster Wallace recounts his experience as press at the Illinois State Fair. But it’s clear from this opening that he’s not just reporting on the events exactly as they happened—though that’s also true— but rather making a point about how the East Coast, where he lives and works, thinks about the Midwest.

In his opening paragraph, Wallace states that outright: “Why exactly they’re interested in the Illinois State Fair remains unclear to me. I suspect that every so often editors at East Coast magazines slap their foreheads and remember that about 90 percent of the United States lies between the coasts, and figure they’ll engage somebody to do pith-helmeted anthropological reporting on something rural and heartlandish.”

Not every motif needs to be stated this clearly , but in an essay as long as Wallace’s, particularly since the audience for such a piece may feel similarly and forget that such a large portion of the country exists, it’s important to make that point clear.

But Wallace doesn’t just rest on introducing his motif and telling the events exactly as they occurred from there. It’s clear that he selects events that remind us of that idea of East Coast cynicism , such as when he realizes that the Help Me Grow tent is standing on top of fake grass that is killing the real grass beneath, when he realizes the hypocrisy of craving a corn dog when faced with a real, suffering pig, when he’s upset for his friend even though he’s not the one being sexually harassed, and when he witnesses another East Coast person doing something he wouldn’t dare to do.

Wallace is literally telling the audience exactly what happened, complete with dates and timestamps for when each event occurred. But he’s also choosing those events with a purpose—he doesn’t focus on details that don’t serve his motif. That’s why he discusses the experiences of people, how the smells are unappealing to him, and how all the people he meets, in cowboy hats, overalls, or “black spandex that looks like cheesecake leotards,” feel almost alien to him.

All of these details feed back into the throughline of East Coast thinking that Wallace introduces in the first paragraph. He also refers back to it in the essay’s final paragraph, stating:

At last, an overarching theory blooms inside my head: megalopolitan East Coasters’ summer treats and breaks and literally ‘getaways,’ flights-from—from crowds, noise, heat, dirt, the stress of too many sensory choices….The East Coast existential treat is escape from confines and stimuli—quiet, rustic vistas that hold still, turn inward, turn away. Not so in the rural Midwest. Here you’re pretty much away all the time….Something in a Midwesterner sort of actuates , deep down, at a public event….The real spectacle that draws us here is us.

Throughout this journey, Wallace has tried to demonstrate how the East Coast thinks about the Midwest, ultimately concluding that they are captivated by the Midwest’s less stimuli-filled life, but that the real reason they are interested in events like the Illinois State Fair is that they are, in some ways, a means of looking at the East Coast in a new, estranging way.

The reason this works so well is that Wallace has carefully chosen his examples, outlined his motif and themes in the first paragraph, and eventually circled back to the original motif with a clearer understanding of his original point.

When outlining your own narrative essay, try to do the same. Start with a theme, build upon it with examples, and return to it in the end with an even deeper understanding of the original issue. You don’t need this much space to explore a theme, either—as we’ll see in the next example, a strong narrative essay can also be very short.

Death of a Moth by Virginia Woolf

After a time, tired by his dancing apparently, he settled on the window ledge in the sun, and, the queer spectacle being at an end, I forgot about him. Then, looking up, my eye was caught by him. He was trying to resume his dancing, but seemed either so stiff or so awkward that he could only flutter to the bottom of the window-pane; and when he tried to fly across it he failed. Being intent on other matters I watched these futile attempts for a time without thinking, unconsciously waiting for him to resume his flight, as one waits for a machine, that has stopped momentarily, to start again without considering the reason of its failure. After perhaps a seventh attempt he slipped from the wooden ledge and fell, fluttering his wings, on to his back on the window sill. The helplessness of his attitude roused me. It flashed upon me that he was in difficulties; he could no longer raise himself; his legs struggled vainly. But, as I stretched out a pencil, meaning to help him to right himself, it came over me that the failure and awkwardness were the approach of death. I laid the pencil down again.

In this essay, Virginia Woolf explains her encounter with a dying moth. On surface level, this essay is just a recounting of an afternoon in which she watched a moth die—it’s even established in the title. But there’s more to it than that. Though Woolf does not begin her essay with as clear a motif as Wallace, it’s not hard to pick out the evidence she uses to support her point, which is that the experience of this moth is also the human experience.

In the title, Woolf tells us this essay is about death. But in the first paragraph, she seems to mostly be discussing life—the moth is “content with life,” people are working in the fields, and birds are flying. However, she mentions that it is mid-September and that the fields were being plowed. It’s autumn and it’s time for the harvest; the time of year in which many things die.

In this short essay, she chronicles the experience of watching a moth seemingly embody life, then die. Though this essay is literally about a moth, it’s also about a whole lot more than that. After all, moths aren’t the only things that die—Woolf is also reflecting on her own mortality, as well as the mortality of everything around her.

At its core, the essay discusses the push and pull of life and death, not in a way that’s necessarily sad, but in a way that is accepting of both. Woolf begins by setting up the transitional fall season, often associated with things coming to an end, and raises the ideas of pleasure, vitality, and pity.

At one point, Woolf tries to help the dying moth, but reconsiders, as it would interfere with the natural order of the world. The moth’s death is part of the natural order of the world, just like fall, just like her own eventual death.

All these themes are set up in the beginning and explored throughout the essay’s narrative. Though Woolf doesn’t directly state her theme, she reinforces it by choosing a small, isolated event—watching a moth die—and illustrating her point through details.

With this essay, we can see that you don’t need a big, weird, exciting event to discuss an important meaning. Woolf is able to explore complicated ideas in a short essay by being deliberate about what details she includes, just as you can be in your own essays.

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

On the twenty-ninth of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born. Over a month before this, while all our energies were concentrated in waiting for these events, there had been, in Detroit, one of the bloodiest race riots of the century. A few hours after my father’s funeral, while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel, a race riot broke out in Harlem. On the morning of the third of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.

Like Woolf, Baldwin does not lay out his themes in concrete terms—unlike Wallace, there’s no clear sentence that explains what he’ll be talking about. However, you can see the motifs quite clearly: death, fatherhood, struggle, and race.

Throughout the narrative essay, Baldwin discusses the circumstances of his father’s death, including his complicated relationship with his father. By introducing those motifs in the first paragraph, the reader understands that everything discussed in the essay will come back to those core ideas. When Baldwin talks about his experience with a white teacher taking an interest in him and his father’s resistance to that, he is also talking about race and his father’s death. When he talks about his father’s death, he is also talking about his views on race. When he talks about his encounters with segregation and racism, he is talking, in part, about his father.

Because his father was a hard, uncompromising man, Baldwin struggles to reconcile the knowledge that his father was right about many things with his desire to not let that hardness consume him, as well.

Baldwin doesn’t explicitly state any of this, but his writing so often touches on the same motifs that it becomes clear he wants us to think about all these ideas in conversation with one another.

At the end of the essay, Baldwin makes it more clear:

This fight begins, however, in the heart and it had now been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair. This intimation made my heart heavy and, now that my father was irrecoverable, I wished that he had been beside me so that I could have searched his face for the answers which only the future would give me now.

Here, Baldwin ties together the themes and motifs into one clear statement: that he must continue to fight and recognize injustice, especially racial injustice, just as his father did. But unlike his father, he must do it beginning with himself—he must not let himself be closed off to the world as his father was. And yet, he still wishes he had his father for guidance, even as he establishes that he hopes to be a different man than his father.

In this essay, Baldwin loads the front of the essay with his motifs, and, through his narrative, weaves them together into a theme. In the end, he comes to a conclusion that connects all of those things together and leaves the reader with a lasting impression of completion—though the elements may have been initially disparate, in the end everything makes sense.

You can replicate this tactic of introducing seemingly unattached ideas and weaving them together in your own essays. By introducing those motifs, developing them throughout, and bringing them together in the end, you can demonstrate to your reader how all of them are related. However, it’s especially important to be sure that your motifs and clear and consistent throughout your essay so that the conclusion feels earned and consistent—if not, readers may feel mislead.

5 Key Tips for Writing Narrative Essays

Narrative essays can be a lot of fun to write since they’re so heavily based on creativity. But that can also feel intimidating—sometimes it’s easier to have strict guidelines than to have to make it all up yourself. Here are a few tips to keep your narrative essay feeling strong and fresh.

Develop Strong Motifs

Motifs are the foundation of a narrative essay . What are you trying to say? How can you say that using specific symbols or events? Those are your motifs.

In the same way that an argumentative essay’s body should support its thesis, the body of your narrative essay should include motifs that support your theme.

Try to avoid cliches, as these will feel tired to your readers. Instead of roses to symbolize love, try succulents. Instead of the ocean representing some vast, unknowable truth, try the depths of your brother’s bedroom. Keep your language and motifs fresh and your essay will be even stronger!

Use First-Person Perspective

In many essays, you’re expected to remove yourself so that your points stand on their own. Not so in a narrative essay—in this case, you want to make use of your own perspective.

Sometimes a different perspective can make your point even stronger. If you want someone to identify with your point of view, it may be tempting to choose a second-person perspective. However, be sure you really understand the function of second-person; it’s very easy to put a reader off if the narration isn’t expertly deployed.

If you want a little bit of distance, third-person perspective may be okay. But be careful—too much distance and your reader may feel like the narrative lacks truth.

That’s why first-person perspective is the standard. It keeps you, the writer, close to the narrative, reminding the reader that it really happened. And because you really know what happened and how, you’re free to inject your own opinion into the story without it detracting from your point, as it would in a different type of essay.

Stick to the Truth

Your essay should be true. However, this is a creative essay, and it’s okay to embellish a little. Rarely in life do we experience anything with a clear, concrete meaning the way somebody in a book might. If you flub the details a little, it’s okay—just don’t make them up entirely.

Also, nobody expects you to perfectly recall details that may have happened years ago. You may have to reconstruct dialog from your memory and your imagination. That’s okay, again, as long as you aren’t making it up entirely and assigning made-up statements to somebody.

Dialog is a powerful tool. A good conversation can add flavor and interest to a story, as we saw demonstrated in David Foster Wallace’s essay. As previously mentioned, it’s okay to flub it a little, especially because you’re likely writing about an experience you had without knowing that you’d be writing about it later.

However, don’t rely too much on it. Your narrative essay shouldn’t be told through people explaining things to one another; the motif comes through in the details. Dialog can be one of those details, but it shouldn’t be the only one.

Use Sensory Descriptions

Because a narrative essay is a story, you can use sensory details to make your writing more interesting. If you’re describing a particular experience, you can go into detail about things like taste, smell, and hearing in a way that you probably wouldn’t do in any other essay style.

These details can tie into your overall motifs and further your point. Woolf describes in great detail what she sees while watching the moth, giving us the sense that we, too, are watching the moth. In Wallace’s essay, he discusses the sights, sounds, and smells of the Illinois State Fair to help emphasize his point about its strangeness. And in Baldwin’s essay, he describes shattered glass as a “wilderness,” and uses the feelings of his body to describe his mental state.

All these descriptions anchor us not only in the story, but in the motifs and themes as well. One of the tools of a writer is making the reader feel as you felt, and sensory details help you achieve that.