- Faena Miami Beach

- Faena Buenos Aires

- What is Aleph?

Slavoj Žižek's 10 Favorite Films In The Criterion Collection

Two quality criteria: slavoj žižek’s chosen films within the the criterion collection’s catalog..

If Žižek has earned the moniker “pop philosopher’ or ‘the Elvis of cultural theory’ it is thanks to the ease with which he moves between diverse areas of Western culture and with a certain fondness for cinema. He cites films that include blockbusters and art cinema as pretexts to discuss the validity of ideas and concepts by Marx, Lacan, Walter Benjamin and other theorists of critical thinking. Žižek takes scenes from films as a kind of nutshell in which you can find the most characteristic features of our societies.

The Slovenian philosopher does this for various reasons, one of which is very simple: because he has seen a lot of films. Žižek is a great film buff and is also a viewer that sees films differently thanks to his philosophical baggage, from an enriched point of view ––that hermeneutical perspective from which a gesture, a sequence or a detail can hold the possibility of conceptualization. It is not that the films of Alfred Hitchcock, for example, are Lacanian, but certain structures of society can be explained via Lacan’s ideas and, in the same way that films such as Vertigo (1958) or Psycho (1960) fall within those structures, they can be viewed in a Lacanian way.

Žižek recently visited the offices of The Criterion Collection, perhaps the most exquisite brand of movies sold for home viewing. Beyond its commercial success, the The Criterion Collection has somehow established itself as a critical effort; the films in its catalog are always accompanied by material that enrichens the viewers’ experience: unseen footage or out-takes, alternative endings, short documentaries on the filming of a certain movie and audio commentary that is a parallel accompaniment to the film. The latter is one of the most distinctive features of the collection because the people chosen as commentators are perfect for the film in question, either because they directed it, they are specialists in the material or because their profession brings a stimulating perspective to it.

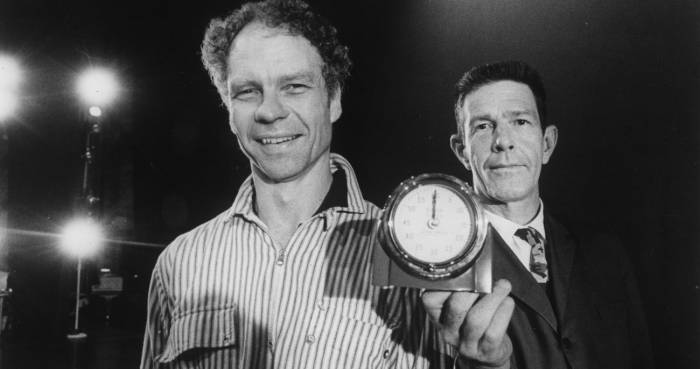

In fact Žižek has been one such commentator. For Alfonso Cuáron’s Y tu mama también (2002), The Criterion Collection chose the Slovenian to provide the voice-off commentary. It is therefore not such a surprise that Žižek would visit the collection’s offices and, once there, choose his 10 favorite films from the catalog, and for each one he has provided a brief commentary, a kind of spontaneous mini-critique attached to his selection.

Here is the Žižek’s top ten, which can be taken as a brief guide to the crossroads of cinema and criticism of the world in which we live.

Trouble in Paradise (1932) – dir. Ernst Lubitsch “It’s the best critique of capitalism.”

Sweet Smell of Success (1957) – dir. Alexander Mackendrick “It’s a nice depiction of the corruption of the American press.”

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) – dir. Peter Weir “I simply like early Peter Weir movies. … It’s like his version of Stalker.”

Murmur of the Heart (1971) – dir. Louis Malle “It’s one of those nice gentle French movies where you have incest. Portrayed as a nice secret between mother and son. I like this.”

The Joke (1969) – dir. Jaromil Jireš “The Joke is the first novel by Milan Kundera and I think it’s his only good novel. After that it all goes down.”

The Ice Storm (1997) – dir. Ang Lee “I have a personal attachment to this film. When James Schamus was writing the scenario, he told me he was reading a book of mine and that my theoretical book was inspiration [sic]. So it’s personal reason but I also loved the movie.”

Great Expectations (1946) dir. David Lean “I am simply a great fan of Dickens.”

Rossellini’s History Films (Box Set) – The Age of the Medici (1973), Cartesius (1974), Blaise Pascal (1972) “Rossellini’s history films, I prefer them. These late, long, boring TV movies. I think that the so-called great Rossellinis, for example German Year Zero and so on, they no longer really work. I think this is the Rossellini to be rehabilitated.”

City Lights (1931) – dir. Charlie Chaplin “What is there to say? This is one of the greatest movies of all time.”

Carl Theodor Dreyer Box Set – Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), Gertrud (1964) “It’s more out of my love for Denmark. It’s nice to know that in the ‘20s and ‘30s, Denmark was already a cinematic superpower.

Y Tu Mamá También (2002) – dir. Alfonso Cuáron “This is for obvious personal reasons. I do the comment. [He recorded the DVD Commentary for the movie] Although, I must say that my favorite Cuáron is Children of Men.”

Antichrist (2009) – dir. Lars Von Trier “I will probably not like it, but I like Von Trier. It is simply a part of a duty.”

Related Articles

Pictorial spiritism (a woman's drawings guided by a spirit)

There are numerous examples in the history of self-taught artists which suggest an interrogation of that which we take for granted within the universe of art. Such was the case with figures like

Astounding fairytale illustrations from Japan

Fairy tales tribal stories— are more than childish tales. Such fictions, the characters of which inhabit our earliest memories, aren’t just literary works with an aesthetic and pleasant purpose. They

A cinematic poem and an ode to water: its rhythms, shapes and textures

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. - John Keats Without water the equation of life, at least life as we know it, would be impossible. A growing hypothesis holds that water, including the

Watch beauty unfold through science in this "ode to a flower" (video)

The study of the microscopic is one of the richest, most aesthetic methods of understanding the world. Lucky is the scientist who, upon seeing something beautiful, is able to see all of the tiny

To invent those we love or to see them as they are? Love in two of the movies' favorite scenes

So much has been said already, of “love” that it’s difficult to add anything, much less something new. It’s possible, though, perhaps because even if you try to pass through the sieve of all our

This app allows you to find and preserve ancient typographies

Most people, even those who are far removed from the world of design, are familiar with some type of typography and its ability to transform any text, help out dyslexics or stretch an eight page paper

The secrets of the mind-body connection

For decades medical research has recognized the existence of the placebo effect — in which the assumption that a medication will help produces actual physical improvements. In addition to this, a

The sea as infinite laboratory

Much of our thinking on the shape of the world and the universe derives from the way scientists and artists have approached these topics over time. Our fascination with the mysteries of the

Sharing and collaborating - natural movements of the creative being

We might sometimes think that artistic or creative activity is, in essence, individualistic. The Genesis of Judeo-Christian tradition portrays a God whose decision to create the world is as vehement

John Malkovich becomes David Lynch (and other characters)

John Malkovich and David Lynch are, respectively, the actor and film director who’ve implicitly or explicitly addressed the issues of identity and its porous barriers through numerous projects. Now

Be in the Know.

Sign up to receive the latest news, events, special offers and more from Faena.

- Coffee House

Boringly postmodern and an ideological fantasy: Slavoj Žižek reviews Matrix Resurrections

- 12 January 2022, 12:47pm

Slavoj Žižek

The first thing that strikes the eye in the multitude of reviews of Matrix Resurrections is how easily the movie’s plot (especially its ending) has been interpreted as a metaphor for our socio-economic situation. Leftist pessimists read it as an insight into how, to put it bluntly, there is no hope for humanity: we cannot survive outside the Matrix (the network of corporate capital that controls us), freedom is impossible. Then there are social-democratic pragmatic ‘realists’ who see in the movie a vision of some kind of progressive alliance between humans and machines, sixty years after the destructive Machine Wars. In these wars ‘scarcity among the Machines led to a civil war that saw a faction of Machines and programs defect and join human society.’ The humans also change tack: Io (a human city in reality outside the Matrix led by General Niobe) is a much better place to live than Zion, their previous city in reality (there are clear hints of destructive revolutionary fanaticism in Zion in previous Matrix movies).

The scarcity among the Machines refers not just to the devastating effects of the war but above all to the lack of energy produced by humans for the Matrix. Remember the basic premise of the Matrix series: what we experience as the reality we live in is an artificial virtual reality generated by the ‘Matrix’, the mega-computer directly attached to all our minds; it is in place so that we can be effectively reduced to a passive state of living batteries providing the Matrix with energy. However, the unique impact of the film thus resides not so much in this premise, its central thesis, but in its central image of the millions of human beings leading a claustrophobic life in water-filled cocoons, kept alive in order to generate the energy for the Matrix. So when (some of the) people ‘awaken’ from their immersion into the Matrix-controlled virtual reality, this awakening is not an opening into the wide space of the external reality, but a horrible realisation of this enclosure, where each of us is effectively just a foetus-like organism, immersed in pre-natal fluid. This utter passivity is the foreclosed fantasy that sustains our conscious experience as active, self-positing subjects – it is the ultimate perverse fantasy , the notion that we are essentially instruments of the Other’s (the Matrix’s) jouissance , sucked out of our life-substance like batteries.

Therein resides the true libidinal enigma of this dispositif : why does the Matrix need human energy? That this is to solve the energy problem is, of course, meaningless: the Matrix could have easily found another, more reliable source of energy which would have not demanded the extremely complex arrangement of a virtual reality coordinated for millions of human units. The only consistent answer is: the Matrix feeds on the human’s jouissance. S o we are here back at the fundamental Lacanian thesis that the big Other itself, far from being an anonymous machine, needs the constant influx of jouissance . This is how we should turn around the state of things presented by the film: what the film renders as the scene of our awakening into our true situation is effectively its exact opposite, the very fundamental fantasy that sustains our being.

But how does the Matrix react to the fact that humans produce less energy? Here a new figure called Analyst enters : he discovers that if the Matrix manipulates fears and desires of humans, they produce more energy that can be sucked by the machines:

The Analyst is the new Architect, the manager of this new version of the Matrix. But where the Architect sought to control human minds through cold, hard math and facts, the Analyst likes to take a more personal approach, manipulating feelings to create fictions that keep the blue-pills in line. (He observes that humans will ‘believe the craziest shit,’ which really isn’t very far off from the truth if you’ve ever spent any time on Facebook.) The Analyst says that his approach has made humans produce more energy to feed the Machines than ever before, all while keeping them from wanting to escape the simulation.

Capital is not an objective fact like a mountain or a machine which will remain even if all people around it disappear, it exists only as a virtual Other of a society

With a little bit of irony we could say that the Analyst corrects the falling profit rate of using humans as energy batteries: he realizes that just stealing enjoyment from humans is not productive enough, we (the Matrix) should also manipulate the experience of humans that serve as batteries so that they will experience more enjoyment. Victims themselves have to enjoy: the more humans enjoy, the more surplus-enjoyment can be drawn from them – Lacan’s parallel between surplus-value and surplus-enjoyment is again confirmed here. The problem is just that, although the new regulator of the Matrix is called ‘Analyst” (with an obvious reference to the psychoanalyst), he doesn’t act as a Freudian analyst but as a rather primitive utilitarian, following the maxim: avoid pain and fear and get pleasure. There is no pleasure-in-pain, no ‘beyond the pleasure principle’, no death drive, in contrast to the first film in which Smith, the agent of the Matrix, gives a different, much more Freudian explanation:

Did you know that the first Matrix was designed to be a perfect human world? Where none suffered, where everyone would be happy? It was a disaster. No one would accept the programme. Entire crops of the humans serving as batteries were lost. Some believed we lacked the programming language to describe your perfect world. But I believe that, as a species, human beings define their reality through suffering and misery. The perfect world was a dream that your primitive cerebrum kept trying to wake up from. Which is why the Matrix was re-designed to this: the peak of your civilization.

Most popular

Limor simhony philpott, trump might be bad news for israel.

One could effectively claim that Smith (let us not forget: not a human being as others but a virtual embodiment of the Matrix – the big Other – itself) is the stand-in for the figure of the analyst within the universe of the film much more than the Analyst. This regression of the last film is confirmed by another archaic feature, the affirmation of the productive force of sexual relationship:

Analyst explains that after Neo and Trinity died, he resurrected them to study them, and found they overpowered the system when they worked together, but if they are kept close to each other without making contact, the other humans within the Matrix would produce more energy for the machines.

In many media Matrix Resurrections was hailed as less ‘binary’, as more open towards the ‘rainbow’ of transgender experiences – but, as we can see, the old Hollywood formula of the production of a couple-matrix is here again: ‘Neo himself has no interest in anything except rekindling his relationship with Trinity.’ This regression is grounded in what is false already in the first movie. The best known scene in the first Matrix occurs when Morpheus offers to Neo the choice between a Blue Pill and Red Pill. But this choice is a strange non-choice: when we live immersed in virtual reality we don’t take any pill, so the only choice is ‘Take the red pill or do nothing.’ The blue pill is a placebo, it changes nothing. Plus we don’t have only virtual reality regulated by the Matrix (accessible if we choose the blue pill) and external ‘real reality’ (the devastated real world full of ruins accessible if we choose the red pill); we have the Machine itself which constructs and regulates our experience (this, the flow of digital formulas and not the ruins, is what Morpheus refers to when he says Neo ‘Welcome to the desert of the real.’) This Machine is (in the film’s universe) an object present in ‘real reality’: gigantic computers constructed by humans which held us prisoners and regulate our experiences.

The choice between the blue pill and the red pill in the first Matrix movie is false, but this does not mean that all reality is just in our brain: we interact in a real world, but through our fantasies imposed on us by the symbolic universe in which we live. The symbolic universe is ‘transcendental’, the idea that there is an agent controlling it as an object is a paranoiac dream – the symbolic universe is no object in the world, it provides the very frame of how we approach objects. Today, however, we are getting closer and closer to manufactured machines which promise to provide a virtual universe into which we can enter (or which controls us against our will). China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences pursues what it calls the ‘intelligentization’ of warfare: ‘War has started to shift from the pursuit of destroying bodies to paralyzing and controlling the opponent.’ We can be sure that the West is doing the same – the only difference will be (maybe) that if it will go public about it, there will be a humanitarian twist (‘we are not killing humans, we are just for a brief time diverting their minds…’).

One of the names of ‘taking the blue pill’ is Zuckerberg’s project of the ‘Metaverse’: we take the blue pill by registering in the metaverse in which the limitations, tensions and frustrations of ordinary reality are magically left behind – but we have to pay a big price for it: ‘Mark Zuckerberg “has unilateral control over 3 billion people” due to his unassailable position at the top of Facebook, the whistleblower Frances Haugen told to the British MPs as she called for urgent external regulation to rein in the tech company’s management and reduce the harm being done to society.’ The big achievement of modernity, the public space, is thus disappearing. Days after the Haugen revelations, Zuckerberg announced that his company will change its name from Facebook to Meta, and outlined his vision of Metaverse in a speech that is a true neo-feudal manifesto:

Zuckerberg wants the metaverse to ultimately encompass the rest of our reality – connecting bits of real space here to real space there, while totally subsuming what we think of as the real world. In the virtual and augmented future Facebook has planned for us, it’s not that Zuckerberg’s simulations will rise to the level of reality, it’s that our behaviors and interactions will become so standardized and mechanical that it won’t even matter. Instead of making human facial expressions, our avatars can make iconic thumbs-up gestures. Instead of sharing air and space together, we can collaborate on a digital document. We learn to downgrade our experience of being together with another human being to seeing their projection overlaid into the room like an augmented reality Pokemon figure.

Metaverse will act as a virtual space beyond (meta) our fractured and hurtful reality, a virtual space in which we will smoothly interact through our avatars, with elements of augmented reality (reality overlaid with digital signs). It will thus be nothing less than metaphysics actualised: a metaphysical space fully subsuming reality which we will be allowed to enter in fragments only insofar as it will be overlaid by digital guidelines manipulating our perception and intervention. And the catch is that we will get a commons which is privately owned, with a private feudal lord overseeing and regulating our interaction.

This brings us back to the beginning of the movie where Neo visits a therapist (Analyst) in recovery from a suicide attempt. The source of his suffering is that he has no way of verifying the reality of his confused thoughts, so he is afraid of losing his mind. In the course of the film we learn that ‘the therapist is the least trustworthy source that Neo could have turned to. The therapist is not just part of a fantasy that might be a reality, and vice versa… He is just one more layer of fantasy-as-reality, and reality-as-fantasy, a mess of whims, and desires, and dreams that exists in two states at once.’ Is, then, Neo’s suspicion, which drove him to suicide, not just confirmed?

The film’s end brings hope by merely giving the opposite spin to this sad insight: yes, our world is composed just of layers of ‘fantasy-as-reality, and reality-as-fantasy, a mess of whims, and desires’, there is no Archimedean point which eludes the deceitful layers of fake realities. However, this very fact opens up a new space of freedom – the freedom to intervene and rewrite fictions that dominate us. Since our world is composed just of layers of ‘fantasy-as-reality, and reality-as-fantasy, a mess of whims, and desires’, this means that the Matrix is also a mess: the paranoiac version is wrong, there is no hidden agent (Architect or Analyst) who controls it all and secretly pulls the strings. The lesson is that ‘we should learn to fully embrace the power of the stories that we spin for ourselves, whether they be video games or complex narratives about our own pasts… – we might rewrite everything . We can make of fear and desire as we wish; we can alter and shape the people who we love, and we dream of.’ The movie thus ends with a rather boring version of the postmodern notion that there is no ultimate ‘real reality’, just an interplay of the multitude of digital fictions:

Neo and Trinity have given up on the search of epistemic foundations. They do not kill the therapist who has kept them in the bondage of The Matrix. Instead, they thank him. After all, through his work, they have discovered the great power of re-description, the freedom that comes when we stop our search for truth, whatever that nebulous concept might mean, and strive forever for new ways of understanding ourselves. And then, arm in arm, they take off, flying through a world that is theirs to make of.

The movie’s premise that machines need humans is thus correct – they need us not for our intelligence and conscious planning but at a more elementary level of libidinal economy. The idea that machines could reproduce without humans is similar to the dream of the market economy reproducing itself without humans. Some analysts recently proposed the idea that, with the explosive growth of robotisation of production and of artificial intelligence which will more and more play the managerial role of organising production, capitalism will gradually morph into a self-reproducing monster, a network of digital and production machines with less and less need for humans. Property and stocks will remain, but competition on stock exchanges will be done automatically, just to optimize profit and productivity. So for whom or what will things be produced? Will humans not remain as consumers?

Ideally, we can even imagine machines just feeding each other, producing machined parts, energy. Perversely attractive as it is, this prospect is an ideological fantasy: capital is not an objective fact like a mountain or a machine which will remain even if all people around it disappear, it exists only as a virtual Other of a society, a reified form of a social relationship, in the same way that values of stocks are the outcome of the interaction of thousands of individuals but appear to each of them as something objectively given.

Every reader has for sure noticed that, in my description of the movie, I heavily rely on a multitude of reviews which I extensively quote. The reason is now clear: in spite of its occasional brilliance, the film is ultimately not worth seeing – which is why I also wrote this review without seeing it. The editorial that appeared in Pravda on January 28, 1936, brutally dismissed Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District as ‘Muddle Instead of Music’. Although Matrix Resurrections is very intelligently made and full of admirable effects, it ultimately remains a muddle instead of a movie. Resurrections is the fourth film in the Matrix series, so let’s just hope that Lana’s next movie will be what the Fifth Symphony was for Shostakovich, an American artist’s creative response to justified criticism.

Unlock unlimited access

Subscribe to unlock 3 months of unlimited access for just £3

Already a subscriber? Log in

Drama on the London Underground

Because you read about film

Impossible to doze through, sadly: Twisters reviewed

Starmer’s army in private plane hypocrisy

Want to join the debate?

Join the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first 3 months for just £3.

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, chaz's journal, great movies, contributors, tiff: the pervert's guide to cinema.

Slavoj Zizek in the wake of Melanie Daniels, crossing Bodega Bay in a small motorboat.

At 150 minutes, in three parts, "The Pervert's Guide to Cinema" (catchy title, no?) is probably the fastest-moving, most shamelessly enjoyable film I've seen in Toronto so far this year. There is no story, and only one character -- but what a character he is. He's Slavoj Zizek (more precisely, Žižek), Slovenian philosopher and psychoanalyst, and he comes across as a delightfully unhinged Freudian maniac, the sort of heavily-accented mad doctor who might narrate an Ed Wood movie. But, believe it or not, he's the real thing. (I Googled him to be absolutely sure, and now I can't wait to read more of, and about, him.)

And what he does as narrator of this film (directed by Sophie Fiennes, sister of actors Ralph and Joseph) is talk -- and talk and talk and talk -- about movies. He's terrific at it, too. Turns out the good doctor is quite the cinephiliac (with a strong Freudian/Lacanian bent, natch), and in what feels almost like a two-and-a-half-hour free-association, he lets his brilliant and facile mind wander through many of the greatest films ever made -- with a heavy concentration on Hitchcock (emphasis on " Psycho " (1960), " Vertigo " and "The Birds"), David Lynch (" Lost Highway ," " Blue Velvet ," " Mulholland Drive ," " Wild at Heart ") and Andrei Tarkovsky (" Solaris, " "Stalker"). One image, one idea, flows into the next, which makes for an intoxicating strain of film criticism.

This isn't quite the first film of this sort ("A Journey Through American Cinema with Martin Scorsese " springs to mind) -- but there ought to be more. The genre of movies about movies -- in-depth appreciations and evaluations of films that go beyond clip reels like "That's Entertainment!" into something deeper and, well, more entertaining -- is something I hope will blossom over the next few years. It's something I've been thinking about a lot: Film criticism needs to expand beyond mere words, and make better use of other media, including the web and film/video itself, where the images themselves can be seen while they are analyzed.

"Pervert's Guide" begins with a series of Rorschach ink blots, and the movie itself is a lot like those patterns. You may reject some of Zizek's theories or readings, but he's always playing around with fascinating ideas. Are Groucho, Chico and Harpo the Superego, Ego, and Id? Well, to some extent, but that's too neat a formula. And Zizek is flat-out wrong when he describes Harpo as both innocent and evil. Harpo is neither, and Zizek oughtta know better -- he's the Id (much more clearly than Grouch or Chico fit the roles he assigns them), and the Id is amoral, pure appetite, beyond good and evil.

But that's just a quibble. Zizek's central thesis, the way I see it, is that the forces that created the world of "reality" -- God, evolution, however you choose to conceive them -- have left it unfinished and in less than optimal working condition. (No argument from me there.) The world is broken and incomplete (and unstable, forever changing), and fantasy (in every sense of the word) is necessary to complete our experience of reality.

That's where the cinema comes in, as the form that most closely resembles and reflects our own (sub-)consciousness. We are limited in our exposure to reality (through our senses and our brains and our emotions) -- there's no such thing as direct contact with "reality" -- and so, the movies provide the necessary "phantasmic space" (or a similar marvelous phrase Zizek uses) in the place of the abyss. Or something like that.

This is the basic model Zizek employs to discuss expressions of desire, sexuality, horror, consciousness and myriad other concepts in film. As he says: "In sexuality, it's never only me and my partner. There is always some third, imagined element which makes it possible for me to engage in sexuality." He applies this principle splendidly to the erotic memory described (but never seen) in Ingmar Bergman's " Persona "; the written sexual fantasy that is enacted, and thus becomes a nightmare, in Michael Haneke's " The Piano Teacher " (Haneke's most disturbing film in my opinion -- much more so than the dry intellectual exercise of " Funny Games "); and to the pathetic and banal sexual imagination of Tom Cruise's character in Stanley Kubrick's yet-to-be-rediscovered masterpiece, " Eyes Wide Shut ." (Yes, the orgy scene is supposed to be that dull and ridiculous; that scene is the core of the film, and the key to what it's about.)

Zizek offers a perfect short-hand description of what's going on in "Eyes Wide Shut," when he says that after Nicole Kidman impregnates Cruise's character with her fantasy, he spends the rest of the movie trying to "catch up." (Zizek doesn't go much further, but I will: The movie begins with Kidman in the bathroom mirror. They're getting ready to go out and she asks him how she looks. He says she's "beautiful" -- but he doesn't even look at her. He no longer sees her at all; she's just a projection of his own idea of his "wife." That's why she lets him have it later when he smugly says he doesn't feel jealous or threatened when another man finds her attractive because he knows her . And he doesn't know the first thing about her....)

Zizek even takes a brief step into my particular area of fascination and expertise: plumbing in the cinema , and uses techniques similar to ones I've envisioned for exploring the subject (by placing himself into interiors and exteriors from the films). He cites the motel toilet scene in " The Conversation " as a metaphor for our experience of reality. When we flush, we know the excrement (or in that case, blood) doesn't really disappear, leaving a clean white bowl "Sanitized for Your Protection." It has to go somewhere. And our nightmare (defined by him more or less as fantasy made real) is that the awful stuff we've put down there could (and will, eventually) come back up. He compares Harry Caul ( Gene Hackman ) staring into the toilet bowl to the existential act of looking into the void -- and to the act of watching a movie screen, as the excrement is served back up. Ah, what a marvelous image for the magic of the movies!

For those who want to read more about Zizek and how his ideas relate to the movies (his newest book is called " The Parallax View ," after the terrific 1974 Alan Pakula thriller starring Warren Beatty ), I recommend starting off with the Wikipedia article , which includes this:

The fetish is the embodiment of a lie that enables us to endure an unbearable truth (Slavoj Žižek 2000). This is the Real itself (in the Lacanian sense), an isolated object (the Lacanian objet petit a ) whose fascinating and meaningful presence guarantees the structural real, the social order. This real enables one to gain a distance from everyday reality: one introduces an object that has no place inside it, that cannot be named or otherwise symbolized -- the photo collage of the beloved in the film " The Truman Show ," for example. What Žižek means is that every symbolic structure must contain an element that embodies the moment of its impossibility, around which it is organized. This is both impossible and real (in its effect) at the same time. The symptom on the other hand is the return of the repressed truth in a different form. Žižek explains this objet petit a —the MacGuffin—in the following way: "MacGuffin is objet petit a pure and simple: the lack, the remainder of the real that sets in motion the symbolic movement of interpretation, a hole at the center of the symbolic order, the mere appearance of some secret to be explained, interpreted, etc." ( Love thy symptom as thyself ).

After seeing "Pervert's Guide" (by myself), I met some friends for a fantastic Ethiopian feast at a nearby restaurant. Every movie we talked about reminded me of something Zizek had said -- or that he had triggered in my own head -- in "The Pervert's Guide to the Cinema." I couldn't shut up about it, even when I disagreed with Zizek (or, OK, maybe especially then). I think that's one measure of a good movie. And I'm sure I'll be reminded of more from this movie as I see more movies in the festival...

P.S. OK, one last thing from the Wikipedia article about Zizek's notion of " The Real, " much of which he also discusses in "Pervert's Guide":

The symbolic real: the signifier reduced to a meaningless formula (as in quantum physics, which like every science grasps at the real but only produces barely comprehensible concepts)

The real real: a horrific thing, that which conveys the sense of horror in horror films

The imaginary real: an unfathomable something that permeates things as a trace of the sublime. This form of the real becomes perceptible in the film " The Full Monty ," for instance, in the fact that in stripping the unemployed protagonists disrobe completely; in other words, through this extra gesture of voluntary degradation something else, of the order of the sublime, becomes visible.

Latest blog posts

Seven Samurai Continues Its Ride Through Cinema's Past and Future

What About Bob? On the Legacy of One of the Best-Loved Comedians, Bob Newhart (1929-2024)

Levan Akin on Making Films His Way, the Queer Art That Shaped Him, and His Touching New Drama Crossing

All About Suspense: Damian Mc Carthy on Oddity

Latest reviews.

Find Me Falling

Monica castillo.

Matt Zoller Seitz

Glenn Kenny

Sheila O'Malley

Lady in the Lake

Kaiya shunyata.

Great Absence

Brian tallerico.

Advertisement

Supported by

Movie Review

Food for Thought in 'Slavoj Zizek: The Reality of the Virtual'

- Share full article

By Nathan Lee

- June 2, 2006

For those who found the recent documentary "Zizek!" spoiled by an excess of action sequences, there is now "Slavoj Zizek: The Reality of the Virtual," in which the Slovenian intellectual of the title sits in front of a camera and does nothing but talk. And talk.

Shot by Ben Wright over the course of a single day, here is the apotheosis of the talking-head movie, made up entirely of seven long, static takes of Mr. Zizek seated in front of a bookshelf. His discourse is accompanied by a habitual repertory of twitches, spasms and uncontrolled perspiration, an alarming frenzy of exuberance that contributes to his reputation as a rock star of philosophy.

Academic circles may debate whether Mr. Zizek is a legitimate philosopher or merely an especially learned and witty synthesizer. For the general audiences who flock to his lectures, it's enough to witness the ontology of difference explained vis-à-vis Woody Allen's "Love and Death," and to grapple with the notion of chocolate laxative as an "almost Hegelian direct coincidence of the opposites." You'll never look at "The Sound of Music" (if not the reality of the virtual) the same way again.

"There is nothing more miserable today," Mr. Zizek concludes, "than those people who organize their life in order to enjoy themselves." The linchpin of his lecture is the notion that if the goal of classic psychoanalysis was to liberate people from their repressions, mental health under late capitalism requires the struggle to free ourselves from the compulsion to satisfy an endless and irrational set of desires. Food for thought, if definitely an acquired taste.

Slavoj Zizek: The Reality of the Virtual

Opens today in Manhattan

Produced, directed and edited by Ben Wright; directors of photography, Mr. Wright and Daniel Copley; released by Olive Films. At the Quad Cinema, 34 West 13th Street, Greenwich Village. Running time: 71 minutes. This film is not rated.

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

Slavoj Žižek Names His 5 Favorite Films

in Film , Philosophy | May 25th, 2017 Leave a Comment

Anyone who has read the prose of philosopher-provocateur Slavoj Žižek , a potent mixture of the academic and the psychedelic, has to wonder what material has influenced his way of thinking. Those who have seen his film-analyzing documentaries The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema and The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology might come to suspect that he’s watched even more than he’s read, and the interview clip above gives us a sense of which movies have done the most to shape his internal universe. Asked to name his five favorite films, he improvises the following list:

- Melancholia (Lars von Trier), “because it’s the end of the world, and I’m a pessimist. I think it’s good if the world ends”

- The Fountainhead (King Vidor, 1949), “ultracapitalist propaganda, but it’s so ridiculous that I cannot but love it”

- A Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929), “standard but I like it.” It’s free to watch online.

- Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), because “ Vertigo is still too romantic” and “after Psycho , everything goes down”

- To Be or Not to Be (Ernst Lubitsch, 1942), “madness, you cannot do a better comedy”

You can watch a part of Žižek’s breakdown of Psycho , which he describes as “the perfect film for me,” in the Pervert’s Guide to Cinema clip just above . He views the house of Norman Bates, the titular psycho, as a reproduction of “the three levels of human subjectivity. The ground floor is ego: Norman behaves there as a normal son, whatever remains of his normal ego taking over. Up there it’s the superego — maternal superego, because the dead mother is basically a figure of superego. Down in the cellar, it’s the id, the reservoir of these illicit drives.” Ultimately, “it’s as if he is transposing her in his own mind as a psychic agency from superego to id.” But given that Žižek’s interpretive powers extend to the hermenutics of toilets and well beyond, he could probably see just about anything as a Freudian nightmare.

You can watch another of Žižek’s five favorite films, Dziga Vertov’s A Man with a Movie Camera , which we featured here on Open Culture a few years ago, just above. Whether or not you can tune into the right intellectual wavelength to enjoy Žižek’s own work, the man can certainly put together a stimulating viewing list.

For more of his recommendations — and his distinctive justifications for those recommendations — have a look at his picks from the Criterion Collection and his explanation of the greatness of Andrei Tarkovsky . If university superstardom one day stops working out for him, he may well have a bright future as a revival-theater programmer.

Related Content:

Slavoj Žižek Names His Favorite Films from The Criterion Collection

Slavoj Žižek Explains the Artistry of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Films: Solaris , Stalker & More

In His Latest Film, Slavoj Žižek Claims “The Only Way to Be an Atheist is Through Christianity”

Free: Dziga Vertov’s A Man with a Movie Camera , the 8th Best Film Ever Made

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rules for Watching Psycho (1960)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer , the video series The City in Cinema , the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? , and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog . Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Faceboo k .

by Colin Marshall | Permalink | Comments (0) |

Related posts:

Comments (0).

Be the first to comment.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Sign up for Newsletter

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Zizek! (2005)

- User Reviews

Awards | FAQ | User Ratings | External Reviews | Metacritic Reviews

- User Ratings

- External Reviews

- Metacritic Reviews

- Full Cast and Crew

- Release Dates

- Official Sites

- Company Credits

- Filming & Production

- Technical Specs

- Plot Summary

- Plot Keywords

- Parents Guide

Did You Know?

- Crazy Credits

- Alternate Versions

- Connections

- Soundtracks

Photo & Video

- Photo Gallery

- Trailers and Videos

Related Items

- External Sites

Related lists from IMDb users

Recently Viewed

Get the Reddit app

Come here for focussed discussion and debate on the Giant of Ljubljana, Slavoj Žižek and the Slovenian school of psychoanalytically informed philosophy. This is NOT a satire/meme sub.

Zizek on Matrix Resurrections: A muddle instead of a movie

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Fandango at Home

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- 78% Twisters Link to Twisters

- 86% Longlegs Link to Longlegs

- 92% National Anthem Link to National Anthem

New TV Tonight

- 83% Cobra Kai: Season 6

- 86% Kite Man: Hell Yeah!: Season 1

- 100% Simone Biles: Rising: Season 1

- 67% Lady in the Lake: Season 1

- 80% Marvel's Hit-Monkey: Season 2

- 58% Those About to Die: Season 1

- 50% Emperor of Ocean Park: Season 1

- -- Mafia Spies: Season 1

- -- The Ark: Season 2

- -- Unprisoned: Season 2

Most Popular TV on RT

- 80% Star Wars: The Acolyte: Season 1

- 93% The Boys: Season 4

- 100% Supacell: Season 1

- 89% The Bear: Season 3

- 76% Presumed Innocent: Season 1

- 89% Sunny: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- 89% Sunny: Season 1 Link to Sunny: Season 1

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

50 Best 1980s Cult Movies & Classics

71 Best Sci-Fi Movies of the 1950s

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

Renewed and Cancelled TV Shows 2024

Cobra Kai : Season 6, Part 1 First Reviews: Funny and Emotional, but Give Us the Rest Already

- Trending on RT

- Emmy Nominations

- Twisters First Reviews

- Popular Movies

The Pervert's Guide to Ideology

Where to watch.

Rent The Pervert's Guide to Ideology on Apple TV, or buy it on Apple TV.

Critics Reviews

Audience reviews, cast & crew.

Sophie Fiennes

Slavoj Zizek

Lizzie Francke

Executive Producer

Julia Godzinskaya

Tabitha Jackson

More Like This

Related movie news.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Philosophy › Slavoj Žižek and Film Theory

Slavoj Žižek and Film Theory

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on August 4, 2018 • ( 0 )

We need the excuse of a fiction to stage what we really are. ( Slavoj Zizek , in The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema [dir. Sophie Fiennes, 2005])

Would you allow this guy to take your daughter to a movie? Of course not. [Laughs] (Ibid.)

LOST HIGHWAY

One of the early sequences of Sophie Fiennes’s film The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2006) opens with Slovenian cultural analyst and philosopher Slavoj Zizek dressed in a yellow shirt, sitting a little uncomfortably at the helm of a motorized dingy, which, he declares, is floating in the middle of Bodega Bay, the location for Alfred Hitchcock ‘s film The Birds (1963). The sequence then cuts back and forth between scenes from The Birds and Zizek ‘s animated explanations of how the Oedipal tensions between the central character Mitch (Rod Taylor) and his mother underpin an explanation of why the birds inexplicably attack; they are, he suggests, “raw incestuous energy” A little later, with the outboard engine now running, relaxing into his role, Zizek turns to the camera and declares: “You know what I am thinking now? I am thinking like Melanie, I am thinking I want to fuck Mitch” This sequence of Fiennes’s film illustrates the almost perfect conflation of “Zizek the person” with “Zizek the scholar” and now “Zizek the film star” The characteristic frenzy of his tics and spasms, the wild gesticulations of his hands and tugging at his beard, the ever-increasing circles of sweat widening under his arms, his strong Central European accent in English, and above all his outrageous and unselfconscious bad taste in jokes and examples, scatological as well as sexual, all translate directly into print and now on to screen. On screen we have a sense of the unrestrained energy of Zizek ‘s published ideas, which rush ahead of themselves and frenetically dissipate into a web of disseminated connections, of what Robert Boynton calls a “trademark synthesis of philosophical verve and rhetorical playfulness” (1998: 42-3). Zizek the film star also plays to the marketing on the back covers of his books – The Elvis of Cultural Theory and “An academic rock star”1 – and to Zizek the global academic, who is feted on the international academic conference circuit, has run for the office of President of Slovenia, written copy for the catalogue of American outfitters Abercrombie and Fitch, collaborated with experimental punk rock band Laibach and has featured in no fewer than five films.

Slavoj Zizek

However, among many film theorists Zizek ‘s status as film critic (and film star) is that of a clown: the Charlie Chaplin of film theory! This is not only the result of his distinctive personality but also the product of his prolific writing, which employs the thrust of “cut and paste”; articles, essays, chapters, bad jokes and film examples get re-used time and time again, forcing his reader to tease out a philosophical argument from among the asides and at times dubious vignettes.2 Indeed, towards the end of another documentary, Zizek! (dir. Astra Taylor , 2005), in which he also stars, Zizek himself wonders in a psychoanalytic vein whether the attempts to turn him into a figure of fun may represent in fact a deep resistance to taking him seriously.

Most film critics have been scathing of what they see as Zizek ‘s utilitarian plundering in a “machinic” fashion of, in the main, Hollywood feature films to advance and illustrate aspects of his Marxist and psychoanalytical theoretical project. His references to film, it is consistently argued, are merely incidental illustrations, which show little concern for or interest in the fundamental basics of film study.3 We might cite the only one of Zizek’s monographs dedicated to an individual film as such, The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime (2000b), on David Lynch ‘s Lost Highway (1997), as a case in point since it fails to address significant aspects of the film text in favour of an extended exploration of the Lacanian position on fantasy. About one-third into Lost Highway the protagonist, Fred ( Bill Pullman ), who has been sentenced to death for the murder of his unfaithful wife, Renee ( Patricia Arquette ), inexplicably transforms into another person, Pete ( Balthazar Getty ), in his prison cell. It is a transformation from the dull, drab existence of the impotent husband with a mousy non-communicative wife to the exciting and dangerous life of the young virile Pete, who is seduced by the sexually aggressive femme fatale blond reincarnation of Renee named Alice and uncannily played by the same actress. The problem of the film is: how are we to understand this inexplicable (“unreal”) transformation? We can understand it, suggests Zizek , not through any exploration of a formal distinctiveness but by understanding the film as an illustration of the Lacanian notion of “traversing the fantasy”, the re-avowal of subjective responsibility that comes at the end of the psychoanalytic cure. Traversing the fantasy means the recognition that in the long term, Zizek argues, in order to avoid a clash of fantasies we have to acknowledge that fantasy functions merely to screen the abyss or inconsistency in the Other, and we must cease positing that the Other has stolen the “lost” object of our desire. In “traversing” or “going through” the fantasy all we have to do is experience how there is nothing “behind” it, and how fantasy masks precisely this “nothing”. In Lost Highway , Lynch achieves resolution of the contradiction by staging two solutions one after the other on the same level: Renee is destroyed, killed, punished; Alice eludes the control of the male protagonist and disappears triumphantly along the lost highway

THE PARALLAX VIEW

One of the most sustained criticisms of Zizek ‘s (lack of) film criticism has come from veteran cognitivist and post-theorist David Bordwell (2005), who attacks Zizek with the charge of fundamentally lacking responsibility to scholarly process and serious engagement with the nuts and bolts of film studies. This attack is prompted in no small part by Zizek ‘s scathing, and far wittier, dismantling of post-theory in the opening pages of his only complete “film book”, The Fright of Real Tears (2001), before he offers, through analysis of the films of Krzysztof Kieślowski , the alternative of a later Lacanian reading of the film text’s organization of enjoyment. Of course, such oppositions, deconstructionists versus cognitivists or Lacanians versus post-theorists, are dialectical, and Zizek ‘s understanding and exploitation of dialectics underpins his entire project. However, Zizek rereads the traditional dialectical process of Hegel in a more radical fashion. In Zizek s version, the dialectic does not produce a resolution or a synthesized viewpoint; rather, it points out that contradiction is an internal condition of every identity. An idea about something is always disrupted by a discrepancy, but that discrepancy is necessary for the idea to exist in the first place. For Zizek, the truth is always found not in the compromise or middle way but in the contradiction rather than the smoothing out of differences.

The importance of the revised dialectic is paralleled by the Zizekian notion of “the parallax view”, which he defines as follows:

The standard definition of parallax is: the apparent displacement of an object (the shift of its position against a background), caused by a change in observational position that provides a new line of sight. The philosophical twist to be added, of course, is that the observed difference is not simply “subjective”, due to the fact that the same object which exists “out there” is seen from two different stances, or points of view. It is rather that, as Hegel would have put it, subject and object are inherently “mediated”, so that an “epistemological” shift in the subjects point of view always reflects an “ontological” shift in the object itself. Or – to put it in Lacanese – the subjects gaze is always-already inscribed into the perceived object itself, in the guise of its “blind spot”, that which is “in the object more than the object itself”, the point from which the object returns the gaze. (2006a: 17)

Zizek is interested in the “parallax gap” separating two points between which no synthesis or mediation is possible, a gap linked by an “impossible short circuit” of levels that can never meet. At the root of this category is the gap or split (beance) within human subjectivity identified by Jacques Lacan , where the split or barred subject (symbolized by the matheme $) denotes the impossibility of a fully present selfconsciousness. How can one read a book like The Parallax View (2006a) except with a parallax view – by reading, that is, what seems to be there but is never there? The early responses to Zizek’s book, and several bloggers’ websites, have lamented the fact there is not one mention of Alan J. Pakula ‘s film The Parallax View (1974), which is obviously the source of Zizek’s title. How might we explain the perversity of Zizek naming a monumental book that he describes as his “magnum opus” after a film and then not discussing it? And there is also the odd fact that, given that it is an optical phenomenon under discussion, the film references in The Parallax View are minimal. But it would seem that the parallax in Zizek’s sense is present in the film, and the book, in the gap between explanations that account for the immediacy of an event and explanations that account for the totality offerees behind them; or, perhaps, better, in the way that investigating a crime or matter shifts imperceptibly into becoming part of the very crime or matter. Warren Beatty s character in Pakulas film moves from being a reporter to being part of the situation, to being involved, hence suggesting the presence of the observer within the frame. Similarly, for Zizek the shift is from cognitive responses to the moving image (what the screen places in our heads) to an interest in cinema as the screen onto which we project our desires.

A similar “parallax view” marks Zizek ‘s ambivalent relationship to cultural studies. It might seem that Zizek’s interest in mass-cultural objects such as Titanic (dir. James Cameron , 1997), or the novels of Stephen King, are merely part of a recent “turn” to the study of popular culture. By locating his theorizing within popular culture Zizek would seem to share this approach and the assertion that, in Raymond Williams ‘s (1958) words, culture is “ordinary”. Indeed, the charge of Bordwell and others is that with Zizek we have an emphasis of context above text, and that the film text for Zizek is significant not for its own sake, its aesthetic greatness, but for what it might reveal to us about the cultural context from whence it came. However, cultural studies is the object of some of Zizeks most scathing criticism. Zizek approaches the popular from the opposite (parallax) angle: rather than treating high works of art as if they were popular, Zizek treats the popular work of art as if it were “high”; the popular texts in some way transcend their context and testify to some truth that the context obscures. Take his response to the liberal claim that the film Fight Club (dir. David Fincher , 1999) is pro-violence and proto-fascist. Zizek counters that the message of the film is not about “liberating violence” and that it is the reality of the appearance that “violence 311 LAURENCE SIMMONS hurts” that is its true message after all. The fights are “part of a potentially redemptive disciplinary drive … an indication that fighting brings the participants close to the excess-of-life over and above the simple run of life” (2004: 174).

THE LADY VANISHES

For Lacan there are two steps in the psychoanalytic process: interpreting symptoms and traversing fantasy. When we are confronted with the patient s symptoms, we must first interpret them, and penetrate through them to the fundamental fantasy, as the kernel of enjoyment, which is blocking the further movement of interpretation. Then we must accomplish the crucial step of going through the fantasy, of obtaining distance from it, of experiencing how the fantasy-formation is just masking, filling out a certain void, lack, an empty place in the Other. But even so there were patients who had traversed the fantasy and obtained distance from the fantasy-framework of their reality but whose key symptom still persisted. Lacan tried to answer this challenge with the concept of the sinthome . The word sinthome in French is a fifteenth- and sixteenthcentury way of writing the modern word symptome (symptom). By suggesting a word that is derived from an archaic form of writing L acan also shifts the inflection of the term to the letter rather than the signifier (as message to be deciphered). The letter as the site where meaning becomes undone is, for Lacan , a primary inscription of subjectivity. The pronunciation sinthome in French also produces the associations of saint homme (holy man) and synth-homme (synthetic [artificial] man). When it occurs, a symptom causes discomfort and displeasure; nevertheless, we embrace its interpretation with pleasure. But why, in spite of its interpretation, does the symptom not dissolve itself? Why does it persist? The answer, of course, is enjoyment. The symptom is not only a ciphered message; it is a way for the subject to organize his or her enjoyment. Treatment is not strictly speaking directed towards the symptom. The symptom is what the subject must cling to since it is what uniquely characterizes him or her. Zizek ‘s film example is from Ridley Scott ‘s Alien (1979): the figure of the alien, while it is external to the crew on board the spaceship, is also what, by virtue of its threat to them, confers unity on the spaceship crew. Indeed, the ambiguous relationship we have to our sinthomes – one in which we enjoy our suffering and suffer our enjoyments – is like the relationship of the character Ripley ( Sigourney Weaver ) to the alien, which she fears but progressively identifies with (we need only think of the famous scene at the end of the film where she “undresses” for the alien).

Let us take Hitchcock ‘s The Lady Vanishes (1938), and Zizeks influential interpretations of Hitchcock s films in general, as further illustrations of this ambiguity. The existence of an old lady is understood, or made to pass, as a hallucination of the central character Iris. The old woman, Miss Froy ( May Whitty ), is a mother-figure to – but also a counterpart/mirror of – the young woman, Iris ( Margaret Lockwood ), who is the “ideal woman”, the ideal partner in the sexual relation. Iris is returning to London to be married to a boring father figure whom she does not love. His name, Lord Charles Fotheringale, tells us everything. Iris in fact is the woman who, according to Lacanian theory, does not exist. The attraction of the theme is that through the disappearance of her double (mOther), Miss Froy, she is “made to exist”. Zizek suggests that the woman who disappears is always “the woman with whom the sexual relationship would be possible, the elusive shadow of a Woman who would not just be another woman” (1991: 92). At the end Iris falls for Gilbert (Michael Redgrave), who throughout the film has played the role of naughty child (without a father). Hitchcock’s films are full of “the woman who knows too much” (intellectually superior but sexually unattractive, bespectacled but able see into what remains hidden from others: Ingrid Bergman as Alicia in Spellbound [1945]; Ruth Roman as Anne in Strangers on a Train [1951]; Barbara Bel Geddes as Midge in Vertigo [1958]). How can we interpret this motif? These figures are not symbols but, on the other hand, they are not insignificant details of individual films; they persist across a number of Hitchcock films. Zizek ‘s answer is that they are sinthornes . They designate the limit of interpretation, they resist interpretation; they fix or tie together a certain core of enjoyment.

Zizek pursues the difference between the early structuralist Lacan of the 1950s and the late Lacan of the fundamental recalcitrance of the Real of the 1960s on. The Lacanian concept of the Real – the most under-represented component of the triad of the Real, the Symbolic and the Imaginary4 – provides another way to approach that which cannot be spoken (drawn into the Symbolic), because it eludes the ability of the ontological subject to signify it. The Real is the hidden/traumatic underside of our existence or sense of reality, whose disturbing effects are felt in strange and unexpected places. For Zizek, material contained within the pre-ontological, like abject material, can and does emerge into the ontological sphere and once there, however troubling or traumatic, it is made meaning of. Zizek s examples are the Mother Superior who emerges at the close of Vertigo’, who “functions as a kind of negative deus ex rnachina, a sudden intrusion in no way properly grounded in the narrative logic, the prevents the happy ending” (2002: 208); and the swamp that Norman (Anthony Perkins) sinks Marions (Janet Leigh) car into in Psycho “is another in the series of entrance points to the preontological netherworld” (ibid). Nevertheless, despite its irruption into the film text, the Real resists every attempt to render it meaningful and those elements that inhabit it continually elude signification. As such, it is a version of the mythic creature called by Lacan the lamella. On the one hand, the lamella is a thin plate-like strata, like those of a shell or the layers found in geological formations; on the other, it can refer to flat amoeba-like organisms that reproduce asexually Zizek notes, “As Lacan puts it, the lamella does not exist, it insists: it is unreal, an entity of pure semblance, a multiplicity of appearances that seem to enfold a central void – its status is purely phantasmatic” (2006b: 62). In its materializations the lamella marks an Otherness beyond intersubjectivity. Lacan ‘s description, Zizek declares, reminds us of the creatures in horror movies: vampires, zombies, the undead, the monsters of science fiction. Indeed, it is the alien from Scott’s film that may conjure up the lamella in its purest form. Uncannily, Lacan writes in Seminar 11 , a decade before the film appeared, “But suppose it comes and envelopes your face while you are quietly asleep” (Lacan 1979:197); “it is as if Lacan somehow saw the film before it was even made” suggests Zizek (2006b: 63). We think immediately of the scene in the womb-like cave of the unknown planet when the alien leaps from its throbbing egg-like globe and sticks to Executive Officer Kane’s ( John Hurt ) face. This amoeba-like flattened creature that envelops the face stands for irrepressible life beyond all the finite forms that are merely its representatives. In later scenes of the film the alien is able to assume a multitude of different shapes; it is immortal and indestructible. The Real of the lamella is an entity of pure surface without density, an infinitely plastic object that can change its form. It is indivisible, indestructible and immortal, like the living dead, which, after every attempt at annihilation, simply reconstitute themselves and continue on.

With regard to science fiction film, Zizek talks about the Lacanian notion of the Thing (das Ding), used by Freud to designate the ultimate object of our desires in its unbearable intensity, a mechanism that directly materializes the impenetrability of our unacknowledged fantasies. In the film Solaris (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky , 1972), for example, it relates to “the deadlocks of sexual relationship” (Zizek 1999: 222). A space agency psychologist is sent to an abandoned spaceship above a newly discovered planet. Solaris is a planet with a fluid surface that imitates recognizable forms. Scientists in the film hypothesize that Solaris is a gigantic brain that somehow reads our minds. Soon after his arrival Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), the psychologist, finds his dead wife at his side in bed. In fact his wife had committed suicide years ago on Earth after Kelvin deserted her. The dead wife pops up everywhere, sticks around and finally Kevin grasps that she is a materialization of his own innermost traumatic fantasies. He discovers that she does not have human chemical composition. The dead wife, because she has no material identity of her own, thus acquires the status of the Real. However, the wife then becomes aware of the tragedy of her status, that she only exists in the Other s dream and has no innermost substance, and her only option is to commit suicide a second time by swallowing a chemical that will prevent her recomposition. The planet Solaris here, Zizek argues, is the Lacanian Thing ( das Ding ), a sort of obscene jelly, the traumatic Real where Symbolic distance collapses: “it provides – or rather imposes on us – the answer before we even raise the question, directly materialising our innermost fantasies which support our desire” (1999: 223).

WILD AT HEART

Zizek can be credited with a revival of interest in specifically Lacanian psychoanalytical film criticism, but, as we have seen, his approach also represents a decisive shift from Laura Mulvey’s analysis of the gaze of mastery (1975) and Jean-Pierre Oudart ‘s notion of suture and cinematic identification (1977-8), to focus on questions of fantasy and spectator enjoyment. Thus concepts of the gaze and identification in Zizek ‘s film commentary are linked to issues of desire and the fantasmatic support of reality as a defence against the Real.5 A case in point is Zizek s repeated analysis of the sexual assault scene from Lynch ‘s Wild at Heart (1990).6 In this scene Bobby Peru ( Willem Dafoe ) invades the motel room of Lula Fortune (Laura Dern) and after repeated verbal and physical harassment coerces her into saying to him, “Fuck me!” As soon as the exhausted Dern utters the barely audible words that would signal her consent to the sexual act, Dafoe withdraws, puts on a pleasant face and politely retorts: “No thanks, I don t have time today, I’ve got to go; but on another occasion I would do it gladly.” Our uneasiness with this scene, suggests Zizek , lies in the fact that Dafoe’s “unexpected rejection is his ultimate triumph and, in a way, humiliates her more than direct rape” but also that “just prior to her ‘Fuck me!’, the camera focuses on [Derris] right hand, which she slowly spreads out – the sign of her acquiescence, the proof that he has stirred her fantasy” (2006a: 69).

A keystone to Zizek s edifice is the Lacanian notion oi jouissance , which, characteristically, he simply translates as “enjoyment”.7 For Zizek, jouissance is both a feature of individual subjectivity, an explanation of our individual obsessions and investments, and a phenomenon that best describes the political dynamics of collective violence; for example, it is the envy of the jouissance of the Other (as neighbour) that accounts for racism and extreme forms of nationalism. What gets on our nerves about the Other is his or her enjoyment (smelly food, noisy conversation in another language), strange customs (chador) or attitudes to work (he or she is either a workaholic stealing our jobs or a bludger living off our benefits) (see Zizek 1993: 200-205). One of Zizek ‘s central concerns is the status of enjoyment within ideological discourse, where, in our so-called permissive society, there is an obscene command to enjoy that marks the return of the Freudian superego. For example, there is a paradox between the greater possibilities of sexual pleasure in more open societies such as ours and the pursuit of such pleasure, which turns into a duty. The superego stands between these two: the command to enjoy and the duty to enjoy. The law is a renunciation of enjoyment that manifests itself by telling you what you cannot do; in contrast the superego orders you to enjoy what you can do – permitted enjoyment becomes an obligation to enjoy. But of course, Zizek notes, when enjoyment becomes compulsory it is no longer enjoyment.

A PERVERT’S GUIDE TO CINEMA

We might question whether what is at stake in Zizekian film criticism is a pervert s guide to cinema or a cinema guide for perverts. There is the fact or possibility of Zizek ‘s cinematic perversion, which, as we have seen, is a mainstay of many responses from within film studies to his texts, but what if it were possible for this perversion to be more complex than might initially appear, and, secondly, for it to serve a critical and heretical function? Here Zizek s own thoughts on the relationship between cinema and perversion prove illuminating. Zizeks use of Lacan ‘s definition of perversion hinges on the structural aspect of perversion: what is perverse in film viewing is the subjects identification with the gaze of an other, a moment that represents a shift in subjective position within the interplay of gazes articulated by the cinematic text. Utilizing an example from Michael Mann ‘s Manhunter (1986), Zizek comments that the moment Will Graham ( William Petersen ), the FBI profiler, recognizes that the victims’ home movies, which he is watching, are the same films that provided the sadistic killer with vital information, his “obsessive gaze, surveying every detail of the scenery, coincides with the gaze of the murderer” (1991: 108). This identification, Zizek continues, “is extremely unpleasant and obscene … [because] such a coincidence of gazes defines the position of the pervert” (ibid). As Will examines home movies, seeking as a profiler whatever they have in common, his gaze shifts from their content to their status as home movies, thereby coinciding with the gaze of the murderer; in so doing he identifies the form of the movies he is watching and with them. It is their very status as home movies that is the key to unravelling the mystery of Manhunter .