An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research

Affiliation.

- 1 Maastricht University.

- PMID: 23531762

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- AM last page: A guide to research paradigms relevant to medical education. Bergman E, de Feijter J, Frambach J, Godefrooij M, Slootweg I, Stalmeijer R, van der Zwet J. Bergman E, et al. Acad Med. 2012 Apr;87(4):545. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824fbc8a. Acad Med. 2012. PMID: 22452919 No abstract available.

- AM last page. Understanding qualitative and quantitative research paradigms in academic medicine. Castillo-Page L, Bodilly S, Bunton SA. Castillo-Page L, et al. Acad Med. 2012 Mar;87(3):386. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318247c660. Acad Med. 2012. PMID: 22373638 No abstract available.

- AM last page: generalizability in medical education research. Artino AR Jr, Durning SJ, Boulet JR. Artino AR Jr, et al. Acad Med. 2011 Jul;86(7):917. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821fb99e. Acad Med. 2011. PMID: 21715999 No abstract available.

- Mixing it but not mixed-up: mixed methods research in medical education (a critical narrative review). Maudsley G. Maudsley G. Med Teach. 2011;33(2):e92-104. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.542523. Med Teach. 2011. PMID: 21275539 Review.

- [Qualitative methods in medical research--preconditions, potentials and limitations]. Malterud K. Malterud K. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002 Oct 20;122(25):2468-72. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002. PMID: 12448119 Review. Norwegian.

- Memes Adoption in Basic Medical Science Education as a Successful Learning Model: A Mixed Method Quasi-Experimental Study. Sharif A, Kasemy ZA, Rayan AH, Selim HMR, Aloshari SHA, Elkhamisy FAA. Sharif A, et al. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2024 May 29;15:487-500. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S461757. eCollection 2024. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2024. PMID: 38826694 Free PMC article.

- Barriers and facilitators associated with the upscaling of the Transmural Trauma Care Model: a qualitative study. Ratter J, Wiertsema S, Ettahiri I, Mulder R, Grootjes A, Kee J, Donker M, Geleijn E, de Groot V, Ostelo RWJG, Bloemers FW, van Dongen JM. Ratter J, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024 Feb 13;24(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-10643-7. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024. PMID: 38350997 Free PMC article.

- How can the perceptions and experiences of medical educator stakeholders inform selection into medicine? An interpretative phenomenological pilot study. Lombard M, Poropat A, Alldridge L, Rogers GD. Lombard M, et al. MedEdPublish (2016). 2018 Dec 11;7:282. doi: 10.15694/mep.2018.0000282.1. eCollection 2018. MedEdPublish (2016). 2018. PMID: 38089195 Free PMC article.

- The impact of patients' social backgrounds assessment on nursing care: Qualitative research. Mizumoto J, Son D, Izumiya M, Horita S, Eto M. Mizumoto J, et al. J Gen Fam Med. 2023 Sep 22;24(6):332-342. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.650. eCollection 2023 Nov. J Gen Fam Med. 2023. PMID: 38025935 Free PMC article.

- Primary care-led weight-management intervention: qualitative insights into patient experiences at two-year follow-up. Spreckley M, de Lange J, Seidell J, Halberstadt J. Spreckley M, et al. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2023 Dec;18(1):2276576. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2023.2276576. Epub 2023 Nov 20. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2023. PMID: 38016037 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Support & FAQ

AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research

- Onderwijsontwikkeling & Onderwijsresearch

- SHE School of Health Professions Education

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › Academic › peer-review

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 552 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 88 |

| Issue number | 4 |

| DOIs | |

| Publication status | Published - Apr 2013 |

- Education, Medical

- Qualitative Research

- Research Design

- Journal Article

Access to Document

- 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

T1 - AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research

AU - Frambach, Janneke M

AU - van der Vleuten, Cees P M

AU - Durning, Steven J

PY - 2013/4

Y1 - 2013/4

KW - Education, Medical

KW - Humans

KW - Qualitative Research

KW - Research Design

KW - Journal Article

U2 - 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

DO - 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

M3 - Article

C2 - 23531762

SN - 1040-2446

JO - Academic Medicine

JF - Academic Medicine

AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research.

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 552 |

| Number of pages | 1 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 88 |

| Issue number | 4 |

| State | Published - Apr 2013 |

Fingerprint

- quantitative research Social Sciences 100%

- qualitative research Social Sciences 78%

T1 - AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research.

AU - Frambach, Janneke M.

AU - van der Vleuten, Cees P.M.

AU - Durning, Steven J.

PY - 2013/4

Y1 - 2013/4

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84878242017&partnerID=8YFLogxK

M3 - Article

C2 - 23531762

AN - SCOPUS:84878242017

JO - Unknown Journal

JF - Unknown Journal

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

- Corpus ID: 39554180

AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research.

- J. Frambach , C. V. D. van der Vleuten , S. Durning

- Published in Academic medicine : journal… 1 April 2013

- Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges

184 Citations

Exploring students’ perspectives on well-being and the change of united states medical licensing examination step 1 to pass/fail, assessment practices in continuing professional development activities in health professions: a scoping review, tools and instruments for needs assessment, monitoring and evaluation of health research capacity development activities at the individual and organizational level: a systematic review, elevating the behavioral and social sciences in premedical training: mcat2015, the meaning of feedback: medical students’ view, selection as a learning experience: an exploratory study, using focus groups in medical education research: amee guide no. 91, emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study, standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations, the introduction of advanced practice physiotherapy within dutch primary care is a quest for possibilities, added value, and mutual trust: a qualitative study amongst advanced practice physiotherapists and general practitioners.

- Highly Influenced

Related Papers

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

🇺🇦 make metadata, not war

AM Last Page: Quality Criteria in Qualitative and Quantitative Research

- J.M. Frambach

- C.P.M. van der Vleuten

- S.J. Durning

- Article / Letter to editor

- NCEBP 7: Effective primary care and public health

Similar works

Radboud Repository

This paper was published in Radboud Repository .

Having an issue?

Is data on this page outdated, violates copyrights or anything else? Report the problem now and we will take corresponding actions after reviewing your request.

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

90k Accesses

36 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Qualitative Research: Ethical Considerations

How to design bibliometric research: an overview and a framework proposal

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

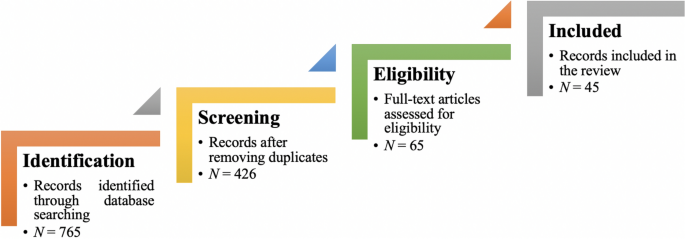

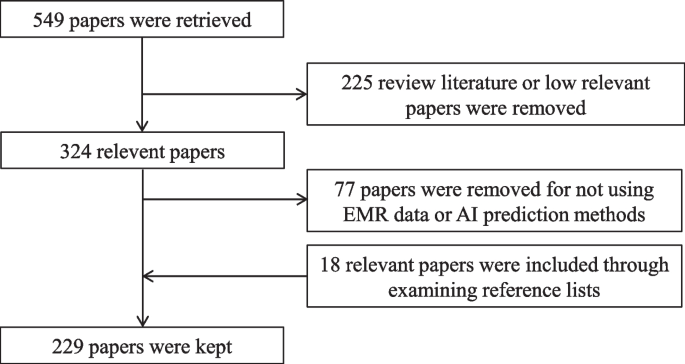

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

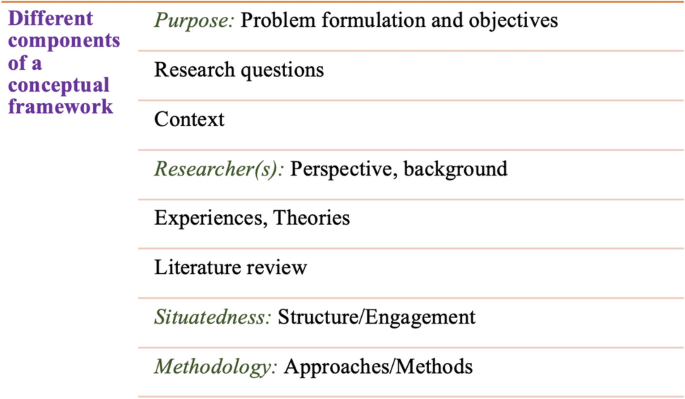

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

A synthesis of recommendations.

O’Brien, Bridget C. PhD; Harris, Ilene B. PhD; Beckman, Thomas J. MD; Reed, Darcy A. MD, MPH; Cook, David A. MD, MHPE

Dr. O’Brien is assistant professor, Department of Medicine and Office of Research and Development in Medical Education, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine, San Francisco, California.

Dr. Harris is professor and head, Department of Medical Education, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Dr. Beckman is professor of medicine and medical education, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Dr. Reed is associate professor of medicine and medical education, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Dr. Cook is associate director, Mayo Clinic Online Learning, research chair, Mayo Multidisciplinary Simulation Center, and professor of medicine and medical education, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Funding/Support: This study was funded in part by a research review grant from the Society for Directors of Research in Medical Education.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Disclaimer: The funding agency had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 .

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. O’Brien, Office of Research and Development in Medical Education, UCSF School of Medicine, Box 3202, 1855 Folsom St., Suite 200, San Francisco, CA 94143-3202; e-mail: [email protected] .

Purpose

Standards for reporting exist for many types of quantitative research, but currently none exist for the broad spectrum of qualitative research. The purpose of the present study was to formulate and define standards for reporting qualitative research while preserving the requisite flexibility to accommodate various paradigms, approaches, and methods.

Method

The authors identified guidelines, reporting standards, and critical appraisal criteria for qualitative research by searching PubMed, Web of Science, and Google through July 2013; reviewing the reference lists of retrieved sources; and contacting experts. Specifically, two authors reviewed a sample of sources to generate an initial set of items that were potentially important in reporting qualitative research. Through an iterative process of reviewing sources, modifying the set of items, and coding all sources for items, the authors prepared a near-final list of items and descriptions and sent this list to five external reviewers for feedback. The final items and descriptions included in the reporting standards reflect this feedback.

Results

The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) consists of 21 items. The authors define and explain key elements of each item and provide examples from recently published articles to illustrate ways in which the standards can be met.

Conclusions

The SRQR aims to improve the transparency of all aspects of qualitative research by providing clear standards for reporting qualitative research. These standards will assist authors during manuscript preparation, editors and reviewers in evaluating a manuscript for potential publication, and readers when critically appraising, applying, and synthesizing study findings.

Qualitative research contributes to the literature in many disciplines by describing, interpreting, and generating theories about social interactions and individual experiences as they occur in natural, rather than experimental, situations. 1–3 Some recent examples include studies of professional dilemmas, 4 medical students’ early experiences of workplace learning, 5 patients’ experiences of disease and interventions, 6–8 and patients’ perspectives about incident disclosures. 9 The purpose of qualitative research is to understand the perspectives/experiences of individuals or groups and the contexts in which these perspectives or experiences are situated. 1 , 2 , 10

Qualitative research is increasingly common and valued in the medical and medical education literature. 1 , 10–13 However, the quality of such research can be difficult to evaluate because of incomplete reporting of key elements. 14 , 15 Quality is multifaceted and includes consideration of the importance of the research question, the rigor of the research methods, the appropriateness and salience of the inferences, and the clarity and completeness of reporting. 16 , 17 Although there is much debate about standards for methodological rigor in qualitative research, 13 , 14 , 18–20 there is widespread agreement about the need for clear and complete reporting. 14 , 21 , 22 Optimal reporting would enable editors, reviewers, other researchers, and practitioners to critically appraise qualitative studies and apply and synthesize the results. One important step in improving the quality of reporting is to formulate and define clear reporting standards.

Authors have proposed guidelines for the quality of qualitative research, including those in the fields of medical education, 23–25 clinical and health services research, 26–28 and general education research. 29 , 30 Yet in nearly all cases, the authors do not describe how the guidelines were created, and often fail to distinguish reporting quality from the other facets of quality (e.g., the research question or methods). Several authors suggest standards for reporting qualitative research, 15 , 20 , 29–33 but their articles focus on a subset of qualitative data collection methods (e.g., interviews), fail to explain how the authors developed the reporting criteria, narrowly construe qualitative research (e.g., thematic analysis) in ways that may exclude other approaches, and/or lack specific examples to help others see how the standards might be achieved. Thus, there remains a compelling need for defensible and broadly applicable standards for reporting qualitative research.

We designed and carried out the present study to formulate and define standards for reporting qualitative research through a rigorous synthesis of published articles and expert recommendations.

We formulated standards for reporting qualitative research by using a rigorous and systematic approach in which we reviewed previously proposed recommendations by experts in qualitative methods. Our research team consisted of two PhD researchers and one physician with formal training and experience in qualitative methods, and two physicians with experience, but no formal training, in qualitative methods.

We first identified previously proposed recommendations by searching PubMed, Web of Science, and Google using combinations of terms such as “qualitative methods,” “qualitative research,” “qualitative guidelines,” “qualitative standards,” and “critical appraisal” and by reviewing the reference lists of retrieved sources, reviewing the Equator Network, 22 and contacting experts. We conducted our first search in January 2007 and our last search in July 2013. Most recommendations were published in peer-reviewed journals, but some were available only on the Internet, and one was an interim draft from a national organization. We report the full set of the 40 sources reviewed in Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, found at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 .

Two of us (B.O., I.H.) reviewed an initial sample of sources to generate a comprehensive list of items that were potentially important in reporting qualitative research (Draft A). All of us then worked in pairs to review all sources and code the presence or absence of each item in a given source. From Draft A, we then distilled a shorter list (Draft B) by identifying core concepts and combining related items, taking into account the number of times each item appeared in these sources. We then compared the items in Draft B with material in the original sources to check for missing concepts, modify accordingly, and add explanatory definitions to create a prefinal list of items (Draft C).

We circulated Draft C to five experienced qualitative researchers (see the acknowledgments) for review. We asked them to note any omitted or redundant items and to suggest improvements to the wording to enhance clarity and relevance across a broad spectrum of qualitative inquiry. In response to their reviews, we consolidated some items and made minor revisions to the wording of labels and definitions to create the final set of reporting standards—the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)—summarized in Table 1 .

To explicate how the final set of standards reflect the material in the original sources, two of us (B.O., D.A.C.) selected by consensus the 25 most complete sources of recommendations and identified which standards reflected the concepts found in each original source (see Table 2 ).

The SRQR is a list of 21 items that we consider essential for complete, transparent reporting of qualitative research (see Table 1 ). As explained above, we developed these items through a rigorous synthesis of prior recommendations and concepts from published sources (see Table 2 ; see also Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, found at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 ) and expert review. These 21 items provide a framework and recommendations for reporting qualitative studies. Given the wide range of qualitative approaches and methodologies, we attempted to select items with broad relevance.

The SRQR includes the article’s title and abstract (items 1 and 2); problem formulation and research question (items 3 and 4); research design and methods of data collection and analysis (items 5 through 15); results, interpretation, discussion, and integration (items 16 through 19); and other information (items 20 and 21). Supplemental Digital Appendix 2, found at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 , contains a detailed explanation of each item, along with examples from recently published qualitative studies. Below, we briefly describe the standards, with a particular focus on those unique to qualitative research.

Titles, abstracts, and introductory material. Reporting standards for titles, abstracts, and introductory material (problem formulation, research question) in qualitative research are very similar to those for quantitative research, except that the results reported in the abstract are narrative rather than numerical, and authors rarely present a specific hypothesis. 29 , 30

Research design and methods. Reporting on research design and methods of data collection and analysis highlights several distinctive features of qualitative research. Many of the criteria we reviewed focus not only on identifying and describing all aspects of the methods (e.g., approach, researcher characteristics and role, sampling strategy, context, data collection and analysis) but also on justifying each choice. 13 , 14 This ensures that authors make their assumptions and decisions transparent to readers. This standard is less commonly expected in quantitative research, perhaps because most quantitative researchers share positivist assumptions and generally agree about standards for rigor of various study designs and sampling techniques. 14 Just as quantitative reporting standards encourage authors to describe how they implemented methods such as randomization and measurement validity, several qualitative reporting criteria recommend that authors describe how they implemented a presumably familiar technique in their study rather than simply mentioning the technique. 10 , 14 , 32 For example, authors often state that data collection occurred until saturation, with no mention of how they defined and recognized saturation. Similarly, authors often mention an “iterative process,” with minimal description of the nature of the iterations. The SRQR emphasizes the importance of explaining and elaborating on these important processes. Nearly all of the original sources recommended describing the characteristics and role of the researcher (i.e., reflexivity). Members of the research team often form relationships with participants, and analytic processes are highly interpretive in most qualitative research. Therefore, reviewers and readers must understand how these relationships and the researchers’ perspectives and assumptions influenced data collection and interpretation. 15 , 23 , 26 , 34

Results. Reporting of qualitative research results should identify the main analytic findings. Often, these findings involve interpretation and contextualization, which represent a departure from the tradition in quantitative studies of objectively reporting results. The presentation of results often varies with the specific qualitative approach and methodology; thus, rigid rules for reporting qualitative findings are inappropriate. However, authors should provide evidence (e.g., examples, quotes, or text excerpts) to substantiate the main analytic findings. 20 , 29

Discussion. The discussion of qualitative results will generally include connections to existing literature and/or theoretical or conceptual frameworks, the scope and boundaries of the results (transferability), and study limitations. 10–12 , 28 In some qualitative traditions, the results and discussion may not have distinct boundaries; we recommend that authors include the substance of each item regardless of the section in which it appears.

The purpose of the SRQR is to improve the quality of reporting of qualitative research studies. We hope that these 21 recommended reporting standards will assist authors during manuscript preparation, editors and reviewers in evaluating a manuscript for potential publication, and readers when critically appraising, applying, and synthesizing study findings. As with other reporting guidelines, 35–37 we anticipate that the SRQR will evolve as it is applied and evaluated in practice. We welcome suggestions for refinement.

Qualitative studies explore “how?” and “why?” questions related to social or human problems or phenomena. 10 , 38 Purposes of qualitative studies include understanding meaning from participants’ perspectives (How do they interpret or make sense of an event, situation, or action?); understanding the nature and influence of the context surrounding events or actions; generating theories about new or poorly understood events, situations, or actions; and understanding the processes that led to a desired (or undesired) outcome. 38 Many different approaches (e.g., ethnography, phenomenology, discourse analysis, case study, grounded theory) and methodologies (e.g., interviews, focus groups, observation, analysis of documents) may be used in qualitative research, each with its own assumptions and traditions. 1 , 2 A strength of many qualitative approaches and methodologies is the opportunity for flexibility and adaptability throughout the data collection and analysis process. We endeavored to maintain that flexibility by intentionally defining items to avoid favoring one approach or method over others. As such, we trust that the SRQR will support all approaches and methods of qualitative research by making reports more explicit and transparent, while still allowing investigators the flexibility to use the study design and reporting format most appropriate to their study. It may be helpful, in the future, to develop approach-specific extensions of the SRQR, as has been done for guidelines in quantitative research (e.g., the CONSORT extensions). 37

Limitations, strengths, and boundaries

We deliberately avoided recommendations that define methodological rigor, and therefore it would be inappropriate to use the SRQR to judge the quality of research methods and findings. Many of the original sources from which we derived the SRQR were intended as criteria for methodological rigor or critical appraisal rather than reporting; for these, we inferred the information that would be needed to evaluate the criterion. Occasionally, we found conflicting recommendations in the literature (e.g., recommending specific techniques such as multiple coders or member checking to demonstrate trustworthiness); we resolved these conflicting recommendations through selection of the most frequent recommendations and by consensus among ourselves.

Some qualitative researchers have described the limitations of checklists as a means to improve methodological rigor. 13 We nonetheless believe that a checklist for reporting standards will help to enhance the transparency of qualitative research studies and thereby advance the field. 29 , 39

Strengths of this work include the grounding in previously published criteria, the diversity of experience and perspectives among us, and critical review by experts in three countries.

Implications and application

Similar to other reporting guidelines, 35–37 the SRQR may be viewed as a starting point for defining reporting standards in qualitative research. Although our personal experience lies in health professions education, the SRQR is based on sources originating in diverse health care and non-health-care fields. We intentionally crafted the SRQR to include various paradigms, approaches, and methodologies used in qualitative research. The elaborations offered in Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 (see https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A218 ) should provide sufficient description and examples to enable both novice and experienced researchers to use these standards. Thus, the SRQR should apply broadly across disciplines, methodologies, topics, study participants, and users.

The SRQR items reflect information essential for inclusion in a qualitative research report, but should not be viewed as prescribing a rigid format or standardized content. Individual study needs, author preferences, and journal requirements may necessitate a different sequence or organization than that shown in Table 1 . Journal word restrictions may prevent a full exposition of each item, and the relative importance of a given item will vary by study. Thus, although all 21 standards would ideally be reflected in any given report, authors should prioritize attention to those items that are most relevant to the given study, findings, context, and readership.

Application of the SRQR need not be limited to the writing phase of a given study. These standards can assist researchers in planning qualitative studies and in the careful documentation of processes and decisions made throughout the study. By considering these recommendations early on, researchers may be more likely to identify the paradigm and approach most appropriate to their research, consider and use strategies for ensuring trustworthiness, and keep track of procedures and decisions.

Journal editors can facilitate the review process by providing the SRQR to reviewers and applying its standards, thus establishing more explicit expectations for qualitative studies. Although the recommendations do not address or advocate specific approaches, methods, or quality standards, they do help reviewers identify information that is missing from manuscripts.

As authors and editors apply the SRQR, readers will have more complete information about a given study, thus facilitating judgments about the trustworthiness, relevance, and transferability of findings to their own context and/or to related literature. Complete reporting will also facilitate meaningful synthesis of qualitative results across studies. 40 We anticipate that such transparency will, over time, help to identify previously unappreciated gaps in the rigor and relevance of research findings. Investigators, editors, and educators can then work to remedy these deficiencies and, thereby, enhance the overall quality of qualitative research.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Margaret Bearman, PhD, Calvin Chou, MD, PhD, Karen Hauer, MD, Ayelet Kuper, MD, DPhil, Arianne Teherani, PhD, and participants in the UCSF weekly educational scholarship works-in-progress group (ESCape) for critically reviewing the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

References Cited Only in Table 2

Supplemental digital content.

- ACADMED_89_9_2014_05_22_OBRIEN_1301196_SDC1.pdf; [PDF] (385 KB)

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework, summary of instructions for authors, common qualitative methodologies and research designs in health professions..., the problem and power of professionalism: a critical analysis of medical..., boyer's expanded definitions of scholarship, the standards for assessing....

Criteria for Quality in Quantitative and Qualitative Writing Research

Good writing research is characterized by evidence that is trustworthy, applicable to multiple practical settings, consistent and transparent about its position—regardless of whether a qualitative or a quantitative approach is used. Qualitative and quantitative writing research both require standards for good evidence, even though the articulation of criteria in the two approaches is different. Below, we provide a description of high quality writing research practices. While individual descriptors might not apply equally to all approaches, editors and authors can refer to these guidelines in assessing the quality of chapters.

| Techniques for Quality in Quantitative Writing Research | Quality Criteria in Quantitative Writing Research | Quality Principles | Quality Criteria in Qualitative Writing Research | Techniques for Quality in Qualitative Writing Research |

|

The extent to which observed effects can be attributed to the independent variable | Truth Value of Evidence |

The extent to which study findings are trustworthy and believable to others ), methods ( ), researchers ( ) and theories ( ). ). | ||

|

The extent to which results can be generalized from the research sample to the population . | Applicability of Evidence |

The extent to which findings can be transferred or applied in different settings e.g. ). | ||

|

The extent to which results are consistent if the study would be replicated | Consistency of Evidence |

The extent to which findings are consistent in relation to the contexts in which they were generated ). | ||

|

The extent to which personal biases are removed and value-free information is gathered | Ethical Treatment of Evidence |

The extent to which findings are based on the study's participants and settings and not researchers' biases | ||

Please also consult the series statement of ethical practices , its language policy , and the WAC Clearinghouse peer review process .

Suggestions for further reading:

- Levitt, H. M. (2019). Reporting qualitative research in psychology . APA.

- Cooper, H. (2019). Reporting quantitative research in psychology . APA.

This overview of quality criteria for the International Exchanges on the Study of Writing book series uses a similar layout and is informed by the article, "AM Last Page: Quality Criteria in Qualitative and Quantitative Research" by Janneke M. Frambach, Cees P. M. van der Vleuten, and Steven J.Durning, which was published in Academic Medicine (volume 88, issue 4, page 552) in April 2013. With the first author’s permission, we have adapted the table for research in writing studies. We also acknowledge revision comments for this document offered by Rebecca Babcock ( https://www.utpb.edu/directory/faculty -staff/babcock_r) and Ruth Villalón ( https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1600-8026 ).

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Ethics

Research across the disciplines: a road map for quality criteria in empirical ethics research

Marcel mertz.

1 Institute for History of Medicine and Medical Ethics, Research Unit Ethics, University of Cologne, Herderstr. 54, D-50931 Cologne, Germany

2 Institute for Ethics, History and Philosophy of Medicine, Hannover Medical School, Carl-Neuberg-Str. 1, D-30625 Hannover, Germany

Julia Inthorn

3 Department of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, University Medical Center Göttingen, Humboldtallee 36, D-37073 Göttingen, Germany

Günter Renz

4 Protestant Academy Bad Boll, Bad Boll, Akademieweg 11, D-73087 Bad Boll, Germany

Lillian Geza Rothenberger

5 Formerly at: Institute of Ethics and History in Medicine, Centre for Medicine, Society and Prevention, University of Tübingen, Gartenstr 47, D-72074 Tübingen, Germany

Sabine Salloch

6 Institute for Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, NRW Junior Research Group “Medical Ethics at the End of Life: Norm and Empiricism”, Ruhr University Bochum, Malakowturm, Markstr 258a, D-44799 Bochum, Germany

Jan Schildmann

Sabine wöhlke, silke schicktanz.

Research in the field of Empirical Ethics (EE) uses a broad variety of empirical methodologies, such as surveys, interviews and observation, developed in disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, and psychology. Whereas these empirical disciplines see themselves as purely descriptive, EE also aims at normative reflection. Currently there is literature about the quality of empirical research in ethics, but little or no reflection on specific methodological aspects that must be considered when conducting interdisciplinary empirical ethics. Furthermore, poor methodology in an EE study results in misleading ethical analyses, evaluations or recommendations. This not only deprives the study of scientific and social value, but also risks ethical misjudgement.

While empirical and normative-ethical research projects have quality criteria in their own right, we focus on the specific quality criteria for EE research. We develop a tentative list of quality criteria – a “road map” – tailored to interdisciplinary research in EE, to guide assessments of research quality. These quality criteria fall into the categories of primary research question, theoretical framework and methods , relevance , interdisciplinary research practice and research ethics and scientific ethos.

EE research is an important and innovative development in bioethics. However, a lack of standards has led to concerns about and even rejection of EE by various scholars. Our suggested orientation list of criteria, presented in the form of reflective questions, cannot be considered definitive, but serves as a tool to provoke systematic reflection during the planning and composition of an EE research study. These criteria need to be tested in different EE research settings and further refined.

Background a

Empirical ethics.

For roughly two decades there have been debates in bioethics about the question of how to address the challenge of best practice in interdisciplinary methodology. Empirical research in bioethics, principally using the methods of social sciences [ 1 , 2 ] b , has considerably increased during this period (e.g. [ 3 ]).

Generally speaking, this debate comes under the label of what is known as “empirical ethics” (abbreviated “EE”, e.g. [ 4 - 8 ]); some authors prefer to talk about “empirically informed ethics” or sometimes “evidence-based ethics” (e.g. [ 9 - 13 ]). This field calls for more empirical research, mainly from sociology, psychology or anthropology, and/or more consideration of empirical research results in normative bioethics c . Whereas empirical disciplines aim to be purely descriptive, however, EE has a strong normative objective: empirical research in EE is not an end in itself, but a required step towards a normative conclusion or statement with regard to empirical analysis, leading to a combination of empirical research with ethical analysis and argument.

Research problem

The widespread use of EE highlights the importance question above: what is the best practice for applying empirical methodologies in such an interdisciplinary setting? This interdisciplinary challenge is still not solved, and proponents of EE can self-critically assume that the quality of EE studies is often unsatisfactory. This problem can be tackled by two strategies: either focusing only on one particular methodology, or trying to establish standards for ‘good’ EE research. The advantage of the latter is obvious: methodologies are highly dependent on theoretical assumptions, and there is no such thing as one true theory, neither in empirical research nor in ethics. It therefore seems most appropriate to focus on best practice instead of perfecting one particular methodology in EE.

The lack of standards for assessing and safeguarding quality is not only a problem for scientific quality per se , but also an ethical problem: poor methodology in EE may give rise to misleading ethical analyses, evaluations or recommendations c , not only depriving the study of scientific and social value, but also risking ethical misjudgement. Improving the quality of EE is therefore an ethical necessity in itself.

Aims & premises

This article aims to provide a “road map” (see below) to assist researchers in conducting EE research, and also to initiate a more focused debate within bioethics about how to improve the quality of EE research. Our contribution should be understood primarily as a heuristic approach. As the discussion on quality criteria for EE research is rather new and touches on a number of complex topics within interdisciplinary research we would see our article as a first and provisional suggestion in this respect. We will discuss four domains of quality criteria and provide a tentative list of questions to be considered by researchers when engaging in EE research. Each formal quality criterion will therefore be guided by practical questions which illustrate its reflective and methodological purpose.

In this paper we will focus mainly on providing and discussing the abstract criteria, but will refrain from citing detailed examples for each criterion because of length limitations. While different application fields for quality criteria can be imagined (such as journal peer review, assessment of research proposals, or the planning of individual research projects), it should be noted that the criteria we present are only designed for guiding EE research (and, partially and indirectly, for reporting on it, since the reported study is what peer reviewers and readers of scientific literature ultimately see).

We start from the premise – supported by our own research, and corroborated by several authors in the debate e.g. [ 6 , 8 , 14 - 18 ] – that empirical research is vital for the vast majority of normative ethical research. Here we focus on “applied ethics”, that is, research concerning analyses, evaluations and recommendations in ethically sensitive fields such as medicine and clinical research, genetics and neuroscience, and also economics and the media.

As far as empirical research is concerned, we limit our claims here to socio-empirical research, i.e. studies based on methodologies from the social sciences . As to the normative-ethical aspect of EE research, we primarily refer to normative-ethical research based on philosophical methods. While theological methods are also important and valuable, we did not assess them in the context of this work.

Definition of empirical ethics research

As a descriptive definition of EE could not claim to define “empirical ethics” for all instances in which this term is used for this, (see e.g. [ 11 , 15 , 19 ]) we will confine ourselves to a stipulative definition covering the various ways of conducting EE research (e.g. [ 6 , 14 , 17 , 20 , 21 ]).

EE research, as we understand it, is normatively oriented bioethical or medical ethical research that directly integrates empirical research e . Key elements of this kind of study are therefore that it encompasses (i) empirical research as well as (ii) normative argument or analysis, and (iii) attempts to integrate them in such a way that knowledge is produced which would not have been possible without combining them. Concerning (iii), we proceed on the assumption that descriptive and normative statements can and should be analytically distinguished from each other in order to evaluate their validity [ 22 - 24 ]. Some proponents of EE, e.g. those taking a phenomenological or hermeneutical approach (e.g. [ 7 , 25 - 27 ]), would assume that descriptive and normative statements are inevitably inseparable and indistinguishable. However, in the context of the current article, we exclude from our analysis approaches to EE research which are mainly hermeneutically or historically oriented. We believe that they can fruitfully contribute to EE research, but these approaches are in need of specific quality criteria that go beyond the scope of this paper. Nonetheless, the development of quality criteria or best practice standards might also be relevant for these approaches.

The above-mentioned integration of empirical research and a normative-ethical argument makes interdisciplinary work inevitable. It implies collaboration between researchers trained in different fields and methodologies. While it is theoretically possible for interdisciplinary research to be carried out by a single researcher skilled in more than one academic field, most EE research will benefit from interdisciplinary research teams (e.g. [ 8 ]). This is because the skills needed for applying both sound empirical research methods and thorough normative analysis and argument are seldom possessed by a single researcher.

Working in teams also offers the opportunity to overcome methodological biases, penchants for particular research approaches and intellectual myopia in terms of background assumptions. For example, in qualitative research (e.g. interviews, observations), intersubjective exchange during the interpretation process is a necessary precondition for enhancing the validity of the results. It also seems unlikely, on the basis of the criteria we are about to present, that such interdisciplinary (team-) work can be done (fully) independent of other team members, based on a strict division of labour between empirical researchers and ethicists. For all these reasons, in our further analysis we proceed on the assumption that EE research should best be carried out in an interdisciplinary research team.

“Road map” analogy

We propose to use the analogy of a “road map” in order to structure the different criteria in our paper, applying the metaphor of moving through a (not yet familiar) landscape for the conduct of EE research. According to this metaphor, the following criteria can be understood as “landmarks”, indicating what paths to take, how fast to go, and where to expect a rocky road or a dead end.

Mapping landmarks of quality and drafting a road map

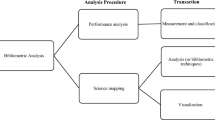

To survey specific “landmarks” of quality in EE research, and to draft a corresponding “road map”, our procedure consists of the following main steps (Figure 1 Search and analysis strategy , provides a graphical overview of the search and analysis strategy the working groups used during the project):

Search and analysis strategy.

(i) to analyse selected empirical quantitative and qualitative studies as well as theoretical ethics studies about living organ donation (“bottom-up-strategy”) regarding their use of empirical data and ethical concepts, and if they reflected upon that relationship;

(ii) to study, present and critically discuss already established quality criteria for each of the following three branches of relevant criteria, viz. a) empirical/social science research, b) philosophical/normative-ethical research, and c) EE research (“top-down-strategy”);

(iii) to consider, present and critically discuss research ethics criteria for each of the three branches, in the light of our experience in EE research and knowledge of the EE debate;

(iv) to develop a consensus among the authors;

(v) to refine the different branches and reduce complexity for publication; and

(vi) to draft a tentative checklist of questions which operationalises criteria pertinent to EE research.