- Access & Outreach

- Student Ambassadors

- How to handle an essay crisis: Ten top tips

It’s 9pm. You’ve had a fantastic evening chatting with friends – or maybe you were off at a society or sports training session, or even just catching up on some Netflix. That’s not the important bit here. You realise, as you return to your room, that you’ve got an impending deadline. The real crux of the issue? You’ve not cracked open even one of the books on the reading list, and the essay is due first thing tomorrow morning.

As much as we’d all like to pretend that we’re always organised and on top of our lives, the reality of life means that sometimes (perhaps due to other commitments, or just a healthy dose of procrastination) essays are left a little too close to the deadline for comfort. If you’re finding yourself in this situation for the first time, then allow me to welcome you to the world of the ‘essay crisis’! I have here for you my ten top tips for handling an essay crisis, which should be able to help you navigate the situation a little more smoothly (having tried and tested such steps more times than I would care to admit…).

If possible, avoid getting into an essay crisis in the first place Okay, so I know that, most likely, readers of this advice are already in an essay crisis, making this one perhaps slightly obsolete. But for the sake of any zealous readers acting pre-emptively, or for the sake of avoiding a repeat – it tends to be much more enjoyable not doing essays at the last minute. Sometimes, if you’ve been having a very busy week or just really needed a long chat with a friend, it’s unavoidable, but also take note if you are just procrastinating, and avoid ending up in the realm of the essay crisis if you can.

Try not to panic Moralising over, and into coping with the situation at hand. Perhaps the most important thing you can do is not panic. If you’re the kind of person who is easily stressed under pressure, then try to remember that panicking will not get the essay written or the books read any quicker – it will, in all likelihood, slow you down when time is limited and you probably really just want to go to bed. Keeping a level head will improve your clarity of thought and get the experience over that bit faster.

Break it down into smaller tasks It can seem really daunting at first, when faced with a long reading list and a blank word document, knowing in a few hours, you need a 2,000+ word essay with a coherent, well-explained argument. Break up the essay-writing process into a mini to-do list – for example, with each reading, planning the paragraphs, and then writing each major paragraph, as points on the list – to make the process a bit more manageable.

Be discerning with what you need to read Reading lists can be hugely variable in lengths. Personally, I’ve had anything from 4 to 15 pieces of reading, and know they can be even longer – and that’s without adding some of your own reading, if you really enjoy the topic. However, you should remember (and this applies beyond the realm of the essay crisis) that often you are not expected to have read everything on the list. There may be a few asterisked texts, which you should definitely read, but also try to assess for yourself what seems important and what is more niche. Lecture slides can be a good guide for this. It can also be worth asking friends or tutorial partners who have been more organised this time around if they can recommend any (or, even better, if they have notes they’d be willing to share).

Remove all distractions As painful as it may be at the time, Netflix, Facebook, and Buzzfeed quizzes will all still be available to you in a few hours. What won’t be there? The chance to work on your essay! Do whatever you need to do to really focus, whether that’s turning off your phone (I like the app Forest ) or shutting yourself in the library. You’ll worker faster and better this way.

Fortify yourself Chances are, you’re in for the long haul, so try to make it as pleasant as you can for yourself. Personally, I have a lovely comfy hoodie (a gift from a friend, chosen with essay crises in mind), and would recommend keeping snacks on hand (I like Bunny Bites , Tesco’s version of Pom Bears ). If you like to work with music, then select yourself some good tunes too.

Set targets as you go Something that keeps me motivated along the way is mini targets and self-imposed deadlines – for example, I’ll try to reach 1,000 words by 10pm. It tends to work even better if a friend sets the deadline, as then you’re held accountable (although potentially this should be avoided if said friend would also distract you).

Have fun, if you can! ‘Have fun?! I’m in a crisis here!’ – okay, but you made it through interviews and admissions tests and exams to earn your place here. You’re here because you really care about studying the subject, and because the tutors thought you were capable. Circumstances might not be ideal, but hopefully the subject matter is at least a little bit interesting, and if you can summon up some enthusiasm, the whole process will be much more fun.

Don’t compromise your health for an essay The workload can be intense at Oxford, and if it all gets too much, then don’t be afraid to submit what you can manage or ask for an extension for the sake of your health. This is a balancing act; maybe you’d manage an all-nighter, or maybe you don’t think you can take the pressure at the moment. The most important thing is to communicate with the tutors (or maybe even welfare in college, if you need it).

Try to learn from the experience To tie things off, I hope you come away from the essay crisis experience with more than a patchy knowledge of the tutorial topic and the opening hours of the college library. Hopefully, you’ll have learnt to get started a tad sooner next time – or at least, how to deal with it more smoothly the next time crisis hits!

Jessica Searle is a second-year PPEist, who has continued on with Politics and Economics. When she's not writing blog posts and trying to help improve access, she can usually be found promoting gender equality (as both Secretary for UNWomen Oxford and JCR Gender Equality Rep), or with a book in hand.

- How to write a good Personal Statement

© Merton College, Oxford 2024

Site by Franks + Franks & Olamalu

Essay and dissertation writing skills

Planning your essay

Writing your introduction

Structuring your essay

- Writing essays in science subjects

- Brief video guides to support essay planning and writing

- Writing extended essays and dissertations

- Planning your dissertation writing time

Structuring your dissertation

- Top tips for writing longer pieces of work

Advice on planning and writing essays and dissertations

University essays differ from school essays in that they are less concerned with what you know and more concerned with how you construct an argument to answer the question. This means that the starting point for writing a strong essay is to first unpick the question and to then use this to plan your essay before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard).

A really good starting point for you are these short, downloadable Tips for Successful Essay Writing and Answering the Question resources. Both resources will help you to plan your essay, as well as giving you guidance on how to distinguish between different sorts of essay questions.

You may find it helpful to watch this seven-minute video on six tips for essay writing which outlines how to interpret essay questions, as well as giving advice on planning and structuring your writing:

Different disciplines will have different expectations for essay structure and you should always refer to your Faculty or Department student handbook or course Canvas site for more specific guidance.

However, broadly speaking, all essays share the following features:

Essays need an introduction to establish and focus the parameters of the discussion that will follow. You may find it helpful to divide the introduction into areas to demonstrate your breadth and engagement with the essay question. You might define specific terms in the introduction to show your engagement with the essay question; for example, ‘This is a large topic which has been variously discussed by many scientists and commentators. The principal tension is between the views of X and Y who define the main issues as…’ Breadth might be demonstrated by showing the range of viewpoints from which the essay question could be considered; for example, ‘A variety of factors including economic, social and political, influence A and B. This essay will focus on the social and economic aspects, with particular emphasis on…..’

Watch this two-minute video to learn more about how to plan and structure an introduction:

The main body of the essay should elaborate on the issues raised in the introduction and develop an argument(s) that answers the question. It should consist of a number of self-contained paragraphs each of which makes a specific point and provides some form of evidence to support the argument being made. Remember that a clear argument requires that each paragraph explicitly relates back to the essay question or the developing argument.

- Conclusion: An essay should end with a conclusion that reiterates the argument in light of the evidence you have provided; you shouldn’t use the conclusion to introduce new information.

- References: You need to include references to the materials you’ve used to write your essay. These might be in the form of footnotes, in-text citations, or a bibliography at the end. Different systems exist for citing references and different disciplines will use various approaches to citation. Ask your tutor which method(s) you should be using for your essay and also consult your Department or Faculty webpages for specific guidance in your discipline.

Essay writing in science subjects

If you are writing an essay for a science subject you may need to consider additional areas, such as how to present data or diagrams. This five-minute video gives you some advice on how to approach your reading list, planning which information to include in your answer and how to write for your scientific audience – the video is available here:

A PDF providing further guidance on writing science essays for tutorials is available to download.

Short videos to support your essay writing skills

There are many other resources at Oxford that can help support your essay writing skills and if you are short on time, the Oxford Study Skills Centre has produced a number of short (2-minute) videos covering different aspects of essay writing, including:

- Approaching different types of essay questions

- Structuring your essay

- Writing an introduction

- Making use of evidence in your essay writing

- Writing your conclusion

Extended essays and dissertations

Longer pieces of writing like extended essays and dissertations may seem like quite a challenge from your regular essay writing. The important point is to start with a plan and to focus on what the question is asking. A PDF providing further guidance on planning Humanities and Social Science dissertations is available to download.

Planning your time effectively

Try not to leave the writing until close to your deadline, instead start as soon as you have some ideas to put down onto paper. Your early drafts may never end up in the final work, but the work of committing your ideas to paper helps to formulate not only your ideas, but the method of structuring your writing to read well and conclude firmly.

Although many students and tutors will say that the introduction is often written last, it is a good idea to begin to think about what will go into it early on. For example, the first draft of your introduction should set out your argument, the information you have, and your methods, and it should give a structure to the chapters and sections you will write. Your introduction will probably change as time goes on but it will stand as a guide to your entire extended essay or dissertation and it will help you to keep focused.

The structure of extended essays or dissertations will vary depending on the question and discipline, but may include some or all of the following:

- The background information to - and context for - your research. This often takes the form of a literature review.

- Explanation of the focus of your work.

- Explanation of the value of this work to scholarship on the topic.

- List of the aims and objectives of the work and also the issues which will not be covered because they are outside its scope.

The main body of your extended essay or dissertation will probably include your methodology, the results of research, and your argument(s) based on your findings.

The conclusion is to summarise the value your research has added to the topic, and any further lines of research you would undertake given more time or resources.

Tips on writing longer pieces of work

Approaching each chapter of a dissertation as a shorter essay can make the task of writing a dissertation seem less overwhelming. Each chapter will have an introduction, a main body where the argument is developed and substantiated with evidence, and a conclusion to tie things together. Unlike in a regular essay, chapter conclusions may also introduce the chapter that will follow, indicating how the chapters are connected to one another and how the argument will develop through your dissertation.

For further guidance, watch this two-minute video on writing longer pieces of work .

Systems & Services

Access Student Self Service

- Student Self Service

- Self Service guide

- Registration guide

- Libraries search

- OXCORT - see TMS

- GSS - see Student Self Service

- The Careers Service

- Oxford University Sport

- Online store

- Gardens, Libraries and Museums

- Researchers Skills Toolkit

- LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com)

- Access Guide

- Lecture Lists

- Exam Papers (OXAM)

- Oxford Talks

Latest student news

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR?

Try our extensive database of FAQs or submit your own question...

Ask a question

Oxford University’s other diversity crisis

Good luck trying to become a professor if you don’t have family money.

By Emma Irving

O n a rainy summer’s day, I met Henry at a cosy pub on the outskirts of Oxford. A cheerful man in his 40s, with cherubic curls and a mischievous grin, he was wearing shorts in defiance of the British weather. As we waited to be seated, he eyed up a chicken-and-bacon club sandwich on a neighbouring table and joked, “I need a bit of fattening up, don’t you think?”

Once the waiter took our orders, Henry’s jovial demeanour faded. He nervously scanned the faces of the other diners, in case one belonged to a former colleague from the well-known university nearby. He didn’t want anyone to overhear what he was about to tell me about his past life in academia.

Henry was born into a poor farming family in rural south-west England. He was a bright and curious child and, at the age of 11, he won a bursary to a private boys’ school. Though dedicated to his studies, he continued to help out with farm chores. His mother would often wake him in the middle of the night to assist with a cow in labour. “I’d be there, half asleep, pulling on a rope tied to the calf’s leg,” before going to school the next day, he told me.

Even though no one in Henry’s family had gone to university before, his teacher encouraged him to apply to Oxford. Opening the acceptance letter was a “life-changing” moment, he said, “full of enjoyment and anticipation and excitement for the future”. He had sometimes felt like an outsider growing up: his academic ambition distinguished him from his family, and his background set him apart from his school friends. But at Oxford he never doubted that he belonged. He was popular with both peers and tutors, and received one of the few yearly academic scholarships available to undergraduates.

Henry thought about becoming a lawyer after university : the fact that law firms provided funding for the conversion course made this a viable path for someone who had no family wealth to rely on. But he also applied to a highly competitive masters programme at Oxford. When he was offered a place, one of his tutors urged him to accept, assuring him that he would have a successful career in academia. “I wouldn’t go as far as to say he twisted my arm,” Henry said. “But he certainly made it clear that he thought it would be a big shame for me not to go on and do that.”

Henry had sometimes felt like an outsider growing up: his academic ambition distinguished him from his family, and his background set him apart from his school friends

So Henry stayed at Oxford, completing a two-year masters degree before embarking on a PhD (which the university calls a DP hil). He received a grant for his postgraduate studies from the Arts and Humanities Research Council ( AHRC ), a funding body, but there was a cap of four years total funding per student. It normally takes five years to complete both a masters and DP hil in Henry’s subject, meaning students had to self-fund for a year. ( AHRC funding is now restricted to PhDs .)

Henry qualified for some hardship funding, but he realised that the rest of his tuition would have to be paid for through a combination of short-term, badly paid teaching roles and non-academic work. For the first year of his DP hil, he moved back in with his parents to save money on rent, commuting two-and-a-half hours to Oxford twice a week; he also worked at a company near his home two days a week. In his third year, he returned to Oxford, and held down three part-time jobs – all while completing a course of study that the university officially characterises as a “full-time occupation”.

Henry was nearly 30 when he finished his thesis. (He had extended his DP hil by a year to give him more time to fund his degree.) Although he still wanted to be an academic, he couldn’t help but compare himself with friends who had gone into other fields. In many other professions, nine years of training would easily lead to lucrative opportunities. But many of the roles open to postgraduates like Henry were fixed-term contract (or “casual”) positions – teaching-heavy jobs that often last just nine months to a year. These jobs are often poorly compensated and typically lack employment rights such as sick pay. Even so, competition for them is intense, so Henry felt lucky to secure a year-long lectureship at one of the 44 colleges that make up Oxford.

One might expect that a university as rich as Oxford – which has an estimated total endowment of £6.4bn, if colleges are included – would be able to fund many well-paid academic positions, and would be especially keen to employ its high-achieving graduates. But Henry’s role only paid a stipend of around £14,500. (A stipend is a fixed amount of money that is provided for training to offset specific expenses. It is not legally considered compensation for work performed.) That amount is not unusual for a stipendiary lectureship at Oxford, even today. At the time of writing, an advertised job at a college was offering a stipend of between £13,700 and £15,500 a year.

This is a shockingly low figure for people who have spent nearly a decade becoming experts in their fields. (In contrast, a newly qualified solicitor at one of Britain’s biggest law firms, who will have trained for five or six years, can expect to earn on average just over £72,000 annually.) The university itself estimates that the living costs of a single undergraduate or postgraduate with no dependents are between £14,600 and £21,100 a year in 2023. These stipends also fall far below the median annual salary in Britain, which was £33,000 in 2022. “They treat us like we are very low pond life,” said one academic, who held fixed-term contracts with the university and various colleges for 15 years. “They market [courses] on the basis of our reputations…and yet they won’t even give us a business card saying we teach at the university.” (Oxford declined to respond to this allegation and a number of other specific ones in this piece.)

W alk the streets of Oxford, and you will be plunged back into the Middle Ages. The university’s three oldest colleges (Balliol, Merton, and University) were founded in the mid-1200s, and many of the others were built by the mid-1500s. Visitors are charmed by the whirr and hum of intellectual life and the sandstone buildings that shift in colour from cream to burnished gold as the sun sets. But this seductive warren – bristling with spires and pinnacles, abounding with quadrangles and gardens glimpsed through gates – can also feel intimidating to outsiders.

As one might expect of an institution that has accreted over hundreds of years, the University of Oxford has a structure as labyrinthine as its surroundings. The central university funds and administers departments and faculties, where lectures and laboratory facilities are provided. The self-governing colleges admit students and deliver the intensive tutorials, often one-on-one, that make the Oxford experience distinctive. Academics with permanent positions usually have both a position in their faculty, such as a professorship, and a fellowship in one of the colleges.

The university has been a political and financial springboard for nearly a thousand years. Graduates from the university – and from Cambridge, its rival – fill the highest echelons of the law, media and politics in Britain and around the world. Of Britain’s 57 prime ministers, 30 graduated from Oxford.

Of the permanent academics who declared their ethnicity, 8.5% identify as coming from an ethnic minority; the average for British universities is 20%. Only 11 of the 1,952 permanent academic staff at Oxford are black

Over the past three decades, the university’s elite reputation has made it a target for grievances about Britain’s lack of social mobility. Both Oxford and Cambridge came under pressure to stop favouring private-school applicants, who tend to come from rich families, and to admit more state-school students from a range of backgrounds. Now Oxford spends around £13m a year on “access” initiatives , including outreach to state schools. The university also offers financial help to poorer students: today one in four British undergraduates at Oxford receives an annual bursary.

Measures like these have begun to make the student body more diverse. In 2021, more than two-thirds of undergraduates admitted to Oxford went to state-school – one of the highest ratios since the university began recording detailed admissions statistics in 2007. (Although, as less than a fifth of sixth-form students in the country are privately educated, they are still disproportionately represented at Oxford.) Gender and racial diversity also improved: in 2021, 55% of the British students admitted to Oxford were women, and the percentage of places offered to ethnic-minority students rose to 25%.

The picture is very different for those hoping to forge an academic career at Oxford. Around 80% of full professors are male; the average for British universities is 72%. Of the permanent academics who declared their ethnicity, 8.5% identify as coming from an ethnic minority; the average for British universities is 20%. Only 11 of the 1,952 permanent academic staff at Oxford are black.

These skewed statistics owe much to the rise of the gig economy in academia – and to Oxford’s particularly strong reliance on insecure contracts. According to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency ( HESA ) for the 2019-20 academic year, around one-third of all academic staff in Britain are employed on insecure fixed-term contracts. That figure jumps to two-thirds at Oxford, despite its resources. Cambridge, which shares many of Oxford’s institutional quirks, such as independent colleges, employs significantly less of its academic staff – two-fifths – on fixed-term contracts.

The actual rate of casual work across the university is likely to be even higher than these figures suggest because they only reflect contracts between staff and the central university; individual colleges decide their own employment contracts and are not obliged to collect data about them, despite the fact that most teaching roles are college-based. When approached for comment by 1843 magazine , an Oxford spokesperson acknowledged that “a significant number of our researchers are on fixed-term contracts, which is a consequence of the funding model for much of UK research and an issue right across the higher-education sector.”

Notably, Oxford does not publish data on the socio-economic backgrounds of its permanent academics. But I found, in nearly 30 interviews with fixed-term, permanent and former academics, that those who were not from affluent families found it difficult to withstand the precarity imposed by the academic gig-economy. These pressures seemed to be particularly acute for women and people from ethnic-minority backgrounds.

Casualisation, as this proliferation of insecure contracts has become known, works as a filter favouring the “gentleman academic” – someone who is rich enough to navigate the instability, poor pay and opaque hiring processes for permanent roles. “This is what it used to be in the 18th and 19th century where if you had money then you could have a sort of leisure job,” one academic who grew up in the care system told me. Although she continues to teach at Oxford, she is prioritising a secondary career in order to make ends meet.

W hen Henry began his teaching at Oxford, he hoped it would help him secure a permanent job. According to his recollection, no one employed by the university had ever outlined how unlikely this outcome was. He remembers being told on just one occasion – six years into his academic career – that permanent roles were scarce.

Over the next seven years, Henry hopped from one fixed-term contract to the next. (British law dictates that successive fixed-term contracts can last a maximum of four years in total before a person is, in most cases, presumed by law to be a permanent employee. But because each of the colleges at Oxford is considered a separate employer, academics can be caught in limbo for years.) As soon as he finished one contract, he would start searching for his next, a time-consuming process. Some of his contracts lasted only the academic year, which meant the summers – when most academics are meant to do their research – went unpaid, as did the months-long periods between contracts.

Henry was comparatively lucky: other academics he knew held ad-hoc teaching positions, which were paid by the hour. Even so, he shuttled from one house-share to the next, often unsure how he would pay the rent. His friends stopped inviting him out, because they knew he could not afford to join them. Another academic in a similar situation told me that she never put the heating on and shopped as frugally as possible; even so, she still only had about £7 a day to live on, once rent had been taken care of.

One academic I spoke to was informed, at the end of a lunch with her teaching supervisor, that her hours – and therefore her salary – were being halved with four weeks’ notice

It is not uncommon for fixed-term contract workers to struggle to make ends meet. Many are on contracts that mean they are only paid for the hours they spend teaching: they receive no pay for preparation, administration or pastoral care. This may prevent them from cobbling together several supposedly part-time fixed-term contracts, as, in reality, even one such contract may end up taking as many hours as a full-time role. A number of academics told me that they would often spend at least three or four hours preparing for an hour-long tutorial, for which they would then be paid £25 – pushing the cost of their labour far below the minimum wage (which, as of 2023, is £10.42 an hour for those aged over 23).

Short-term contracts can be altered or cancelled without much notice, which also takes a mental toll. One academic I spoke to was informed, at the end of a lunch with her teaching supervisor, that her hours – and therefore her salary – were being halved with four weeks’ notice. “It was just kind of a haphazard comment,” she said. She never received any formal notice.

Casual contracts offer a chance for academics to develop a professional relationship with the university but, paradoxically, their demands on academics’ time make it very difficult to secure a permanent position. Since teaching obligations and part-time work consumed his days and nights, Henry found it near-impossible to immerse himself in his own work. But, as he discovered when applying for jobs, institutions place the most value on research – even for fixed-term positions with no research element. The prospect of a permanent job seemed to recede ever further into the distance. “I know of no other industry where this absurd situation could possibly exist,” he told me. “A situation where doing your actual job well” – teaching – “is detrimental to your career prospects.”

This emphasis on research is a legacy of government policy going back nearly 40 years. In 1985, the Conservative government, which wanted universities to think of themselves more like businesses, decided to give more money to those institutions that prioritised research. For some universities, this created a virtuous cycle. Their excellence in research pushed them up the university league tables, meaning they got more money from external sources, such as government agencies, non-profit organisations and corporations. Oxford’s total research income is consistently the highest of any British university. In the 2020-21 academic year, the university received more than £800m in research funding; this year, the university again came top in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings – a spot it has held since 2017.

In order to hoover up money, universities have become more inclined to hire people with a track record of published research. But it has become increasingly hard to carve out time in the library without private means of support. As the tutor who grew up in care put it, academia is now “a lifestyle choice, not a career”.

Henry discussed his plight with a colleague who had moved back in with his parents for five years after completing his DP hil. He was able to dedicate himself entirely to research, which led to an offer for a permanent job at Oxford. The colleague advised Henry to cut down on the amount of time he dedicated to teaching. Henry tried to explain that it was impossible for him to do so. “If you went to your parents and said ‘Hey, listen, I’m just gonna live at home for five years and I want you to support me so I can get my dream job,’ I think most people’s parents would give you a good shake,” Henry said, his exasperation palpable. “But that’s why it is far easier to get a permanent academic job if you are rich than if you are poor.”

B ritish universities are enrolling more postgraduates than ever. At Oxford, between 2006 and 2021, the number of postgraduate students at the university almost doubled. These kinds of students are particularly lucrative for universities, as both domestic and international students usually have to pay hefty fees. Moreover, they often help to teach the growing number of undergraduates – most of whom pay the £9,250 annual cap on fees set by the national government in 2015. (From the 2015-16 academic year onwards, the cap on student numbers was removed, meaning that universities were allowed to recruit as many as they liked.) Postgraduates, even after receiving their doctorates, continue to benefit universities: early-career academics are an enthusiastic, inexpensive and expendable form of labour, willing to do anything to secure a rare permanent job.

At Oxford – an extremely desirable place to study and work – this dynamic is particularly pronounced. “It [has] prestige,” one academic put it bluntly. The academic who grew up in care explained that “what happens is the kids who come from [working-class] backgrounds are the most enamoured by the status,” said one academic. “They are the ones who want to stay on and do masters and PhDs , but they do not have the solid middle-class background that will allow them a cushion.”

Henry was already working over 50 hours a week. Now he began to spend an extra 20 hours a week on research

And, as Henry discovered, they have only a slender chance of carving out a viable career there. The turnover rate of permanent academics at British universities is low, meaning that the number of jobs available at any one time for the expanding glut of PhD students is very small. At Oxford, associate professors, who constitute the main academic grade, are initially appointed for a period of five years, after which a review takes place; if they pass, they have a job until retirement. At the time of writing, only five associate professorships were being advertised on Oxford’s cross-college jobs board.

Oxford’s institutional structure may impede efforts to diversify the backgrounds of its hires. Unlike other universities, hiring at Oxford is not organised centrally; instead, a small committee is appointed, usually constituting academics associated with the relevant college and department. Such committees may themselves lack diversity. “They have almost total autonomy over what they choose to do,” an associate professor told me. “Then there’s very little information sharing that happens from one committee to the next.” One academic I spoke to suggested there was a “culture of favouritism”, with some academics potentially benefiting from their connection to permanent academics – for example, a PhD supervisor who is particularly influential.

There is also no requirement for individual colleges to collect demographic data on their staff. According to Simukai Chigudu, an associate professor of African politics at the Department of International Development and a Fellow of St Antony’s College, this has implications for diversity of all kinds. “There isn’t a central mechanism to say we’re going to do a number of strategic hires in certain disciplines or with a certain profile,” he told me. Like most Oxford professors, Chigudu began his career on a fixed-term contract. He reckons he only managed to obtain a permanent job because his predecessor, one of the few black professors in Oxford, died, resulting in a vacancy in his department. The lack of transparency at Oxford, he believes, means that there is insufficient reflection about the demographic make-up of its academics: “We just keep reproducing ourselves,” he said.

Diversity among the academic body at Oxford is not helped by the fact that ethnic minorities and women are disproportionately represented (compared with white men) on the very fixed-term contracts that make it difficult to obtain permanent jobs. One young woman academic – an immigrant from an ethnic-minority family – said that “there’s often this assumption that if you’re in Oxford or Cambridge, you must come from a very privileged background.” Yet ethnic-minority academics are more likely to come from poorer backgrounds than their white counterparts: according to a 2020 report by the Social Metrics Commission, just under half of ethnic-minority families in the UK are poor, compared with one-fifth of white families. The academic had come to feel that, given the odds against her, she should be grateful for securing even a fixed-term contract.

Meanwhile many women academics seeking to have children are unlikely to receive maternity leave if on a fixed-term contract. One academic found out she was pregnant while on her third consecutive one-year contract with the same Oxford college; she had held a total of 13 different contracts over the previous five years. “It was very weird going on maternity leave knowing that that was the end of my job,” she told me. “It’s truly my dream job. And it was a completely irrational thing, but for a while I resented the baby because it felt like I had been forced to give up a job I love.”

These unsustainable emotional and financial dynamics lead many women and people from ethnic-minority or poor backgrounds to quit academia altogether. “I’ve compared it before to being in a slightly abusive relationship,” one woman, who left academia under the strain of becoming a mother, told me. “There’s always that little thread of hope that you’ll get there in the end, which keeps you hanging on and putting up with the poor conditions.”

B y 2014, half of Henry’s undergraduates were achieving firsts, the top mark, in their finals – an impressive success rate. But he still hadn’t published much research. He sought to explain his situation to the professors at his college and receive reassurance that he was on track for a permanent position. Instead they “casually dismissed” his worries about money, he said. “Of course, no universities say they do not want to hire poor people. But it was clear that it was socially taboo to even mention [his financial situation],” he claimed.

Henry felt there were few options open to him outside of academia. PhDs are often so specialised that many academics – particularly those in the humanities – can’t imagine what else they might do. He also feared that he would be considered a failure for giving up after coming so far. “One of the difficulties in leaving is that there’s almost a shame attached to [it],” another academic, who is now a teacher, told me. “There is a kind of mythology in meritocracy which is if you try hard enough, if you’re good enough, you will get there in the end…And of course the implication if you do leave is you weren’t good enough…rather than just saying there’s just not enough jobs.”

Two academics who were on fixed-term contracts at Oxford for 15 years – until their contracts were not renewed in 2022 – are now suing the university

He arranged a meeting with the college’s recently appointed “equality and diversity representative”, whom he hoped would be receptive to his concerns. Yet the representative rebuffed him, he said. He remembers the representative suggesting that he simply had to put in more hours and that the current selection criteria for permanent academic roles were fine. If Henry hadn’t published research by now, the representative said, then there was something wrong. “By that, I understood he meant: something wrong with you,” Henry recalled. “There was a sense of disgust at my saying…I needed to work for money.”

Already working over 50 hours a week, Henry now began to spend an extra 20 hours a week on research. He would read academic articles during meals and in bed. He cut himself off from friends and family. His partner Laura became concerned – Henry had loved going to the theatre, the cinema and dance classes with her (they had met while ballroom dancing). But he was no longer his gregarious self; instead, he was barely present.

Henry eventually came to what he described as a “completely overwhelming” realisation: that he had been “seriously exploited, seriously deceived” by the university. After years of hard work, “I had nothing. I had no savings. I was entirely burned out, and I had no career prospects. I realised I was at a dead end and would likely remain in the depths of poverty for the rest of my life.”

F or many years, Oxford’s culture of individualism, fractured collegiate structure and revolving door of fixed-term employees have largely prevented academics from taking collective action. Yet the university’s gig workers, along with those from other institutions, have managed to make some gains in recent years. Last November, the University and College Union ( UCU ) organised the biggest strike in the history of British higher education: over 70,000 lecturers, librarians and researchers across 150 universities, including Oxford, took part in three days of strikes. (In January, the Universities and Colleges Employers Association made a revised pay offer to the UCU , which found the new terms inadequate; they announced 18 further days of strike action in February and March. On February 17th the UCU announced a two week pause in the strikes to facilitate further negotiations, which are ongoing.)

Legal precedent, too, is changing. In October 2021, lecturers on independent-contractor contracts won a case against Goldsmiths University in London. Now, they are granted the same employment rights as full-time workers, such as the minimum wage, paid holiday, and protection against unlawful discrimination and salary deductions. Inspired by that case, two academics who were on fixed-term contracts at Oxford for 15 years – until their contracts were not renewed in 2022 – are suing the university.

An Oxford spokesperson told 1843 magazine that “the university acknowledges the pressures of working on fixed-term contracts and that these can bear disproportionately on women and ethnic minority groups.” It has introduced some measures that it claims will improve conditions for early-career academics and institutional diversity. In September it appointed its first chief diversity officer, and fixed-term researchers can now apply for internal funds to cover research costs. According to the spokesperson, Oxford exceeded its 2020 target to ensure that women comprise at least a third of the members of important decision-making bodies, and has “announced an independent review of pay and working conditions for all staff at the university.”

“My career will never get back onto the same track as if I’d left university at the same time as my friends did”

Questions remain over how effective these measures will be. And for some scholars, like Henry, the changes are coming too late. He left academia at the end of 2015, after a breakdown. “I was very close to being suicidal and it was only through Laura’s support and the National Health Service that I managed to hold things together and get through,” he said. (He completed six weeks of talking therapy.)

He is now married to Laura and works in an administrative role in a town outside Oxford. “My career will never get back onto the same track as if I’d left university at the same time as my friends did,” he said. “But in some ways I think I was very lucky. I was the very last generation who didn’t pay university fees. I was in a pretty bad way when I decided to leave academia. But if I had £50,000 of undergraduate debt and £25,000 of postgraduate debt, I would have…” He looked down at his plate. “Let’s just say, I don’t like to think about what I would have done.”

Henry and I left the pub. The rain had stopped, and the sun had come out. To the south Oxford stood, proud and beautiful. The city looked from another time, or another world. Henry caught my eye and smiled. He turned his back on the place and slowly walked away. ■

Some names have been changed

CORRECTION: This piece has been updated to reflect that postgraduates at Oxford are not expected to teach unpaid.

Emma Irving is newsletters editor at The Economist

ILLUSTRATIONS: EWELINA KARPOWIAK

More from 1843 magazine

1843 magazine | The rage of Ukraine’s army wives

Two years ago their husbands signed up to defend their country. They still have no idea when they will come home

1843 magazine | America’s gerontocrats are more radical than they look

A conservative writer argues that his country’s rulers exhibit the vices of youth, not old age

1843 magazine | Rogue otters and vicious letterboxes: on the campaign trail in the Outer Hebrides

The remote Scottish constituency has all Britain’s problems but worse

1843 magazine | Canadian Sikhs thought they were safe to protest against India. Then one of them was gunned down

Sikhs campaigning for an independent state believe they are in the Indian government’s sights

1843 magazine | No British election is complete without a man with a bin on his head

Joke candidates reveal the carnival element of British democracy

1843 magazine | “Monkeys with a grenade”: inside the nuclear-power station on Ukraine’s front line

Former employees say the plant is being dangerously mismanaged by the Russians

A collapsed dike near Papendrecht, Netherlands during the 1953 North Sea flood disaster. Courtesy the Dutch National Archives

The disruption nexus

Moments of crisis, such as our own, are great opportunities for historic change, but only under highly specific conditions.

by Roman Krznaric + BIO

Polycrisis. Metacrisis. Omnicrisis. Permacrisis. Call it what you like. We are immersed in an age of extreme turbulence and interconnected global threats. The system is starting to flicker – chronic droughts, melting glaciers, far-Right extremism, AI risk, bioweapons, rising food and energy prices, rampant viruses, cyberattacks.

The ultimate question hanging over us is whether these multiple crises will contribute to civilisational breakdown or whether humanity will successfully rise to such challenges and bend rather than break with the winds of change. It has been commonly argued – from Karl Marx to Milton Friedman to Steve Jobs – that it is precisely moments of crisis like these that provide opportunities for transformative change and innovation. Might it be possible to leverage the instability that appears to threaten us?

The problem is that so often crises fail to bring about fundamental system change, whether it is the 2008 financial crash or the wildfires and floods of the ongoing climate emergency. So in this essay, based on my latest book History for Tomorrow: Inspiration from the Past for the Future of Humanity (2024), I want to explore the conditions under which governments respond effectively to crises and undertake rapid and radical policy change. What would it take, for instance, for politicians to stop dithering and take the urgent action required to tackle global heating?

My motives stem from a palpable sense of frustration. Around two decades ago, when I first began to grasp the scale of the climate crisis, especially after reading Bill McKibben’s book The End of Nature (1989), I thought that, if there were just a sufficient number of climate disasters in a short space of time – like hurricanes hitting Shanghai and New York in the same week as the river Thames flooded central London – then we might wake up to the crisis. But in the intervening years I’ve come to realise I was mistaken: there are simply too many reasons for governments not to act, from the lobbying power of the fossil fuel industry to the pathological fear of abandoning the goal of everlasting GDP growth.

This sent me on a quest to search history for broad patterns of how crises bring about substantive change. What did I discover? That agile and transformative crisis responses have usually occurred in four contexts: war, disaster, revolution and disruption. Before delving into these – and offering a model of change I call the disruption nexus – it is important to clarify the meaning of ‘crisis’ itself.

L et’s get one thing straight from the outset: John F Kennedy was wrong when he said that the Chinese word for ‘crisis’ ( wēijī, 危机) is composed of two characters meaning ‘danger’ and ‘opportunity’. The second character, jī (机), is actually closer to meaning ‘change point’ or ‘critical juncture’. This makes it similar to the English word ‘crisis’, which comes from the ancient Greek krisis , whose verb form, krino , meant to ‘choose’ or ‘decide’ at a critical moment. In the legal sphere, for example, a krisis was a crucial decision point when someone might be judged guilty or innocent.

The meaning and application of this concept has evolved over time. For Thomas Paine in the 18th century, a crisis was a threshold moment when a whole political order could be overturned and where a fundamental moral decision was required, such as whether or not to support the war for American independence. Karl Marx believed capitalism experienced inevitable crises, which could result in economic and political rupture. More recently, Malcolm Gladwell has popularised the idea of a ‘tipping point’ – a similar moment of rapid transformation or contagion in which a system undergoes large-scale change. In everyday language, we use the term ‘crisis’ to describe an instance of intense difficulty or danger in which there is an imperative to act, whether it is a crisis in a marriage or the planetary ecological crisis.

Overall, we can think of a crisis as an emergency situation requiring a bold decision to go in one direction rather than another. So what wisdom does history offer for helping us to understand what it takes for governments to act boldly – and effectively – in response to a crisis?

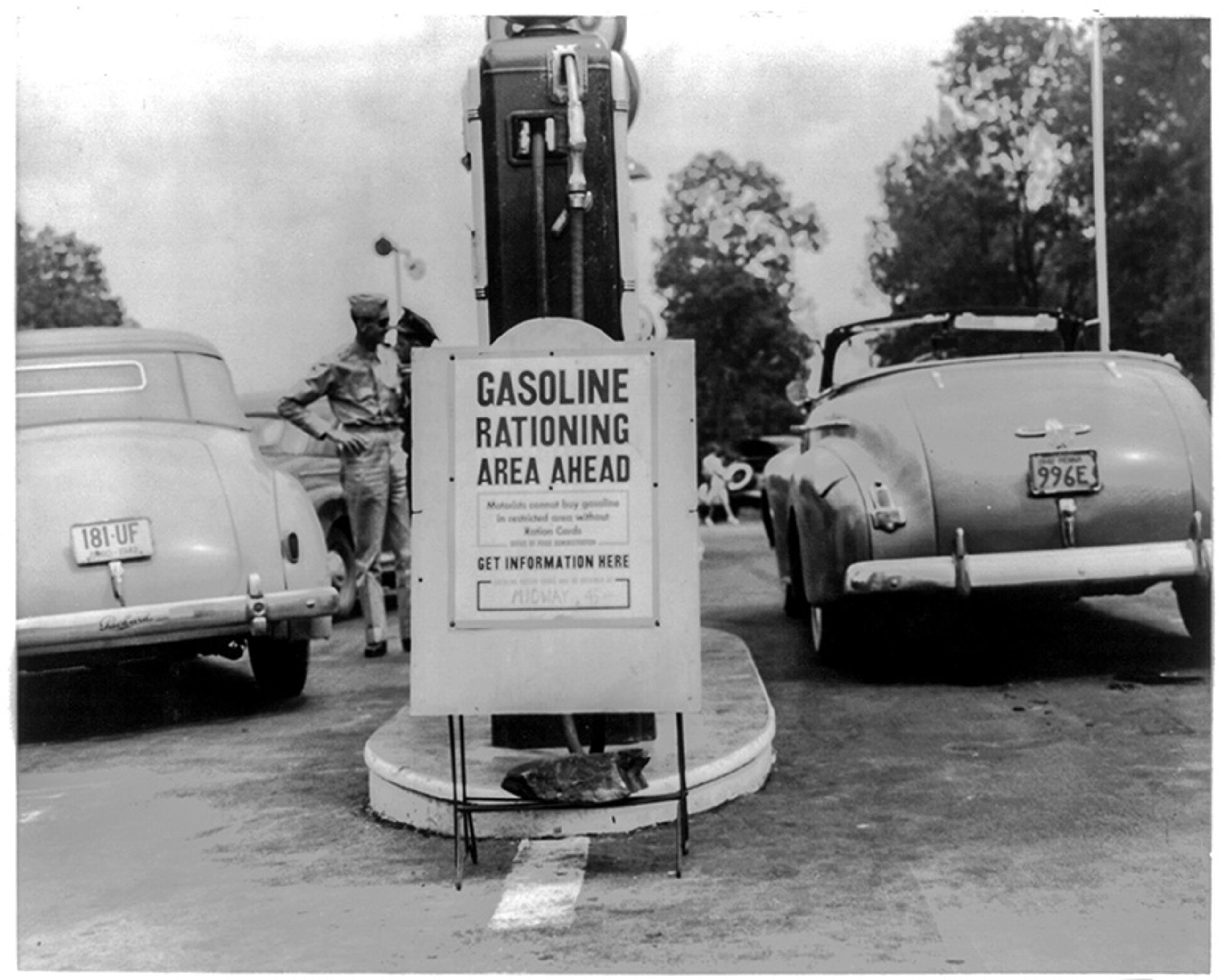

T he most common context in which governments carry out transformative and effective crisis responses is during war. Consider the United States during the Second World War. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, the US government instigated a seismic economic restructuring to put the country on a war footing. Despite fierce opposition from industry, there was a ban on the manufacture of private cars, and petrol was rationed to three gallons per week. The president Franklin D Roosevelt increased the top rate of federal income tax to 94 per cent by the end of the war, while the government borrowed heavily and spent more between 1942 and 1945 than in the previous 150 years. And all of this state intervention was happening in the homeland of free market capitalism. Moreover, the wartime crisis prompted the US to throw the political rulebook out the window and enter a military alliance with its ideological arch enemy, the USSR, to defeat their common enemy.

Gasoline rationing on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, 1942. Courtesy the Library of Congress

A second context in which governments take radical crisis action is in the wake of disasters. Following devastating floods in 1953 , which killed almost 2,000 people, the Dutch government embarked on building a remarkably ambitious flood-defence system called the Delta Works, whose cost was the equivalent of 20 per cent of GDP at the time. No government today is doing anything close to this in response to the climate crisis – not even in the Netherlands, where one-quarter of the country is below sea level and flooding has been a critical threat for centuries.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides another example. In response to the public health emergency, Britain’s ruling Conservative Party introduced a series of radical policy measures that would be generally considered inconceivable by a centre-Right government: they shut schools and businesses, closed the borders, banned sports events and air travel, poured billions into vaccination programmes and even paid the salaries of millions of people for more than a year. It was absolutely clear to them that this was a problem that markets would be unable to solve.

The reality is that the climate emergency is the wrong kind of crisis

A third category of rapid, transformative change is in the context of revolutions, which can generate upheavals that create dramatic openings in the political system. The Chinese Communist Party, for instance, introduced a radical land redistribution programme during the civil war in the late 1940s and following the revolution of 1949, confiscating agricultural property from wealthy landlords and putting it into the hands of millions of poor peasant farmers.

Similarly, the Cuban Revolution of 1959 provided an opportunity for Fidel Castro’s regime to launch the Cuban National Literacy Campaign. In early 1961, more than a quarter of a million volunteers were recruited – 100,000 under the age of 18, and more than half of them women – to teach 700,000 Cubans to read and write. It was one of the most successful mass education programmes in modern history: within a year, national illiteracy had been reduced from 24 per cent to just 4 per cent. Whatever your views on Castro’s Cuba, there is no doubt that revolutions can drive radical change.

These three contexts – war, disaster and revolution – help explain the overwhelming failure of governments to take sufficient action on a crisis such as climate change. The reality is that it is the wrong kind of crisis and doesn’t fit neatly into any of these three categories. It is not like a war, with a clearly identifiable external enemy. It is not taking place in the wake of a revolutionary moment that could inspire transformative action. And it doesn’t even resemble a crisis like the Dutch floods of 1953: in that case the government acted only after the disaster, having ignored years of warnings from water engineers (in fact, unrealised plans for the Delta Works already existed), whereas today we ideally need nations to act before more ecological disasters hit and we cross irreversible tipping points of change. Prevention rather than cure is the only safe option.

D oes that mean there is little hope of governments taking urgent action in response to a crisis like the ecological emergency or other existential threats? Is human civilisation destined to break rather than successfully bend in the face of such critical challenges? Fortunately, there is a fourth crisis context that can jumpstart radical policy change: disruption.

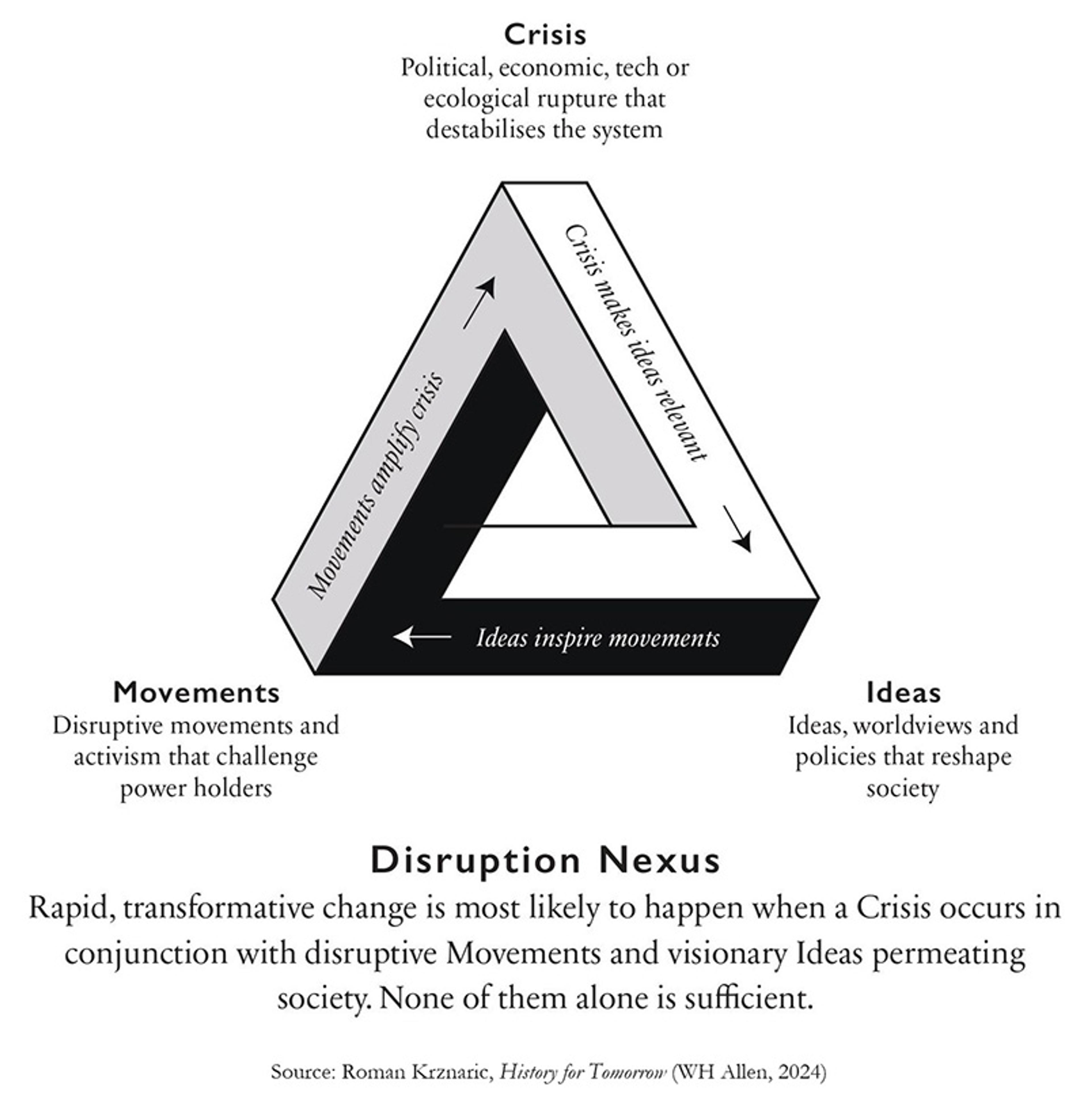

By ‘disruption’ I am referring to a moment of system instability that provides opportunities for rapid transformation, which is created by a combination or nexus of three interlinked factors: some kind of crisis (though typically not as extreme as a war, revolution or cataclysmic disaster), which combines with disruptive social movements and visionary ideas. These three elements are brought together in a model I have developed called the Disruption Nexus (see graphic). Here is how it works.

Let’s begin with the top corner of the triangular diagram labelled ‘crisis’. The model is based on a recognition that most crises – such as the 2008 financial meltdown or the recent droughts in Spain – are rarely in and of themselves sufficient to induce rapid and far-reaching policy change (unlike a war). Rather, the historical evidence suggests that a crisis is most likely to create substantive change if two other factors are simultaneously present: movements and ideas.

Public meetings and pamphlets were not enough to tip the balance against the powerful slave-owning lobby

Social movements play a fundamental role in processes of historical change. Typically, they do this through amplifying crises that may be quietly simmering under the surface or that are ignored by dominant actors in society. As Naomi Klein writes in her book This Changes Everything (2014):

Slavery wasn’t a crisis for British and American elites until abolitionism turned it into one. Racial discrimination wasn’t a crisis until the civil rights movement turned it into one. Sex discrimination wasn’t a crisis until feminism turned it into one. Apartheid wasn’t a crisis until the anti-apartheid movement turned it into one.

Her view – which I think is absolutely right – is that today’s global ecological movement needs to do exactly the same thing and actively generate a sense of crisis, so the political class recognises that ‘climate change is a crisis worthy of Marshall Plan levels of response’.

Multiple historical examples, which I have explored in detail in my book History for Tomorrow (and where you can find a full list of references), bear out this close relationship between disruptive movements and crisis.

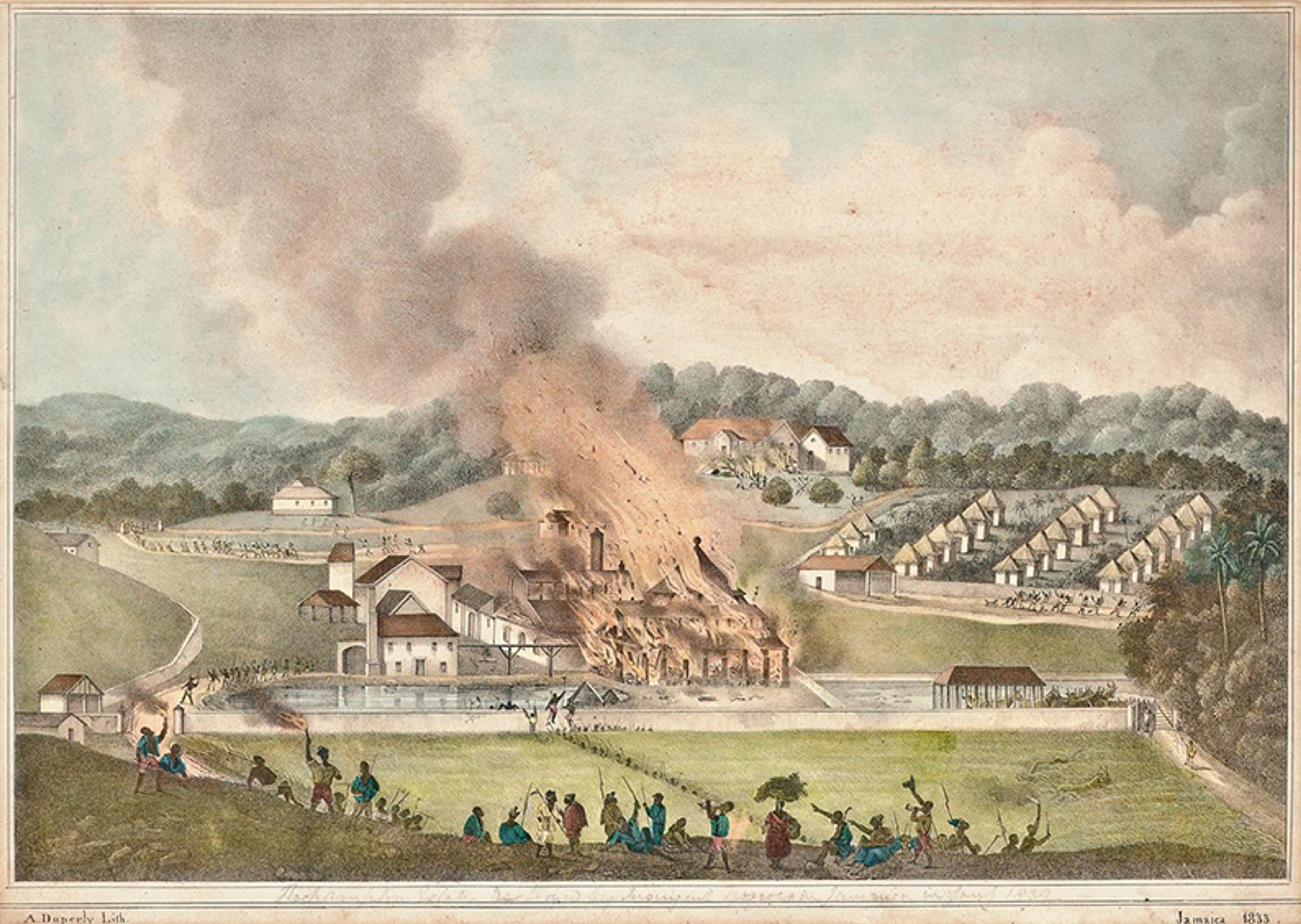

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 in Britain provides a case in point. There was certainly a generalised sense of political crisis in the country in the early 1830s. Urban radicals were pressuring the government to widen the electoral franchise, and impoverished agricultural workers had risen up in the Captain Swing Riots. On top of this, antislavery activists were continuing their decades-long struggle: more than 700,000 people remained enslaved on British-owned sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Yet their largely reformist strategy – such as holding public meetings and distributing pamphlets – was still not enough to tip the balance against the powerful slave-owning lobby.

The turning point came in 1831 in an act of disruption and defiance that created shockwaves in Britain: the Jamaica slave revolt. More than 20,000 enslaved workers rose up in rebellion, setting fire to more than 200 plantations. The revolt was crushed but their actions sent a wave of panic through the British establishment, who concluded that if they did not grant emancipation then the colony could be lost. As the historian David Olusoga points out in Black and British (2016), the Jamaica rebellion was ‘the final factor that tipped the scales in favour of abolition’. In the absence of this disruptive movement, it might have taken decades longer for abolition to enter the statute books.

The Destruction of the Roehampton Estate (1832) by Adolphe Duperly, during the Jamaica rebellion. Courtesy Wikimedia

Another case concerns the granting of the vote to women in Finland in 1906. During the political crisis of the general strike of 1905 – an uprising against Russian imperialism in Finland – the Finnish women’s movement took advantage of the situation by taking to the streets along with trade unionists. The League of Working Women, part of the growing Social Democratic movement, staged more than 200 public protests for the right of all women to vote and run for office, mobilising tens of thousands of women in mass demonstrations. By magnifying the existing crisis, they were able to finally overcome the parliamentary opposition to female suffrage.

More recently, the mass popular uprisings in Berlin in November 1989 amplified the political crisis that had been brewing over previous months, with turmoil in the East German government and destabilising pro-democracy protests having taken place across the Eastern Bloc, partly fuelled by the reforms of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Their actions made history on 9 November when the Berlin Wall was finally breached and the system itself visibly came tumbling down.

In all the above cases, however, a third element alongside movements and crisis was required to bring about change: the presence of visionary ideas. In Capitalism and Freedom (1962), the economist Milton Friedman wrote that, while a crisis is an opportunity for change, ‘when that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around’. From a different perspective, Hannah Arendt argued that a crisis was a fruitful moment for questioning orthodoxies and established ideas as it brought about ‘the ruin of our categories of thought and standards of judgement’, such that ‘traditional verities seem no longer to apply’. Dominant old ideas are in a state of flux and uncertainty, and fresh ones are potentially ready to take their place. In these three historical examples, disruptive ideas around racial equality, women’s rights and democratic freedoms were vital inspiration for the success of transformational movements.

The 2008 financial crash illustrates what happens in the absence of unifying ideas. Two corners of the triangle were in place: the crisis of the crash itself and the Occupy Movement calling for change. What was missing, though, were the new economic ideas and models to challenge the failing system (exemplified by the Occupy slogan ‘Occupy Everything, Demand Nothing’). The result was that the traditional power brokers in the investment banks managed to get themselves bailed out and the old financial system remained intact. This would be less likely to happen today, when new economic models such as ‘doughnut economics’, degrowth and modern monetary theory have gained far more public prominence.

I s the disruption nexus a watertight theory of historical change? Absolutely not. There are no iron laws of history, no universal patterns that stand outside space and time. I’m a firm believer in the statistician George Box’s dictum that ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’.

Several caveats are worth noting. I’m certainly not claiming that transformative change will always take place if all three elements of the disruption nexus are in place: sometimes, the power of the existing system is simply too entrenched (that’s why US peace activists were unable to stop the Vietnam War in the late 1960s – although they certainly managed to turn large swathes of the public against it). My argument is rather that change is most likely when all three ingredients of the nexus are present.

Occasionally, crisis responses can come into conflict with one another, making it difficult to take effective action: in 2018, when the French government attempted to increase carbon taxes on fuel to reduce CO 2 emissions, it was met with the gilets jaunes (yellow vest) movement, which argued that the taxes were unjust given the cost-of-living crisis that had been pushing up energy and food prices.

Furthermore, at times, other factors apart from disruptive movements or visionary ideas will come into play to help create change, such as the role of individual leadership. This was evident in the struggle against slavery, with important parts played by figures including Samuel Sharpe, Elizabeth Heyrick and Thomas Clarkson. The full story of abolition cannot be told without them.

The interplay of the three elements creates a surge of political will, that elusive ingredient of change

Finally, it is vital to recognise that crises can be taken in multiple directions. The Great Depression of the 1930s may have contributed to the rise of progressive Social Democratic welfare states in Scandinavia, but it equally aided the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy. When it comes to crises, be careful what you wish for. Those who desire an avalanche of crises to kickstart change are playing with fire.

Perhaps the greatest virtue of the disruption nexus model – in which movements amplify crisis, crisis makes ideas relevant, and ideas inspire movements – is that it provides a substantive role for collective human agency. During a wartime crisis, military and political leaders typically take charge. In contrast, a disruption nexus provides opportunities for everyday citizens to organise and take action that can potentially shift governments to a critical decision point – a krisis in the ancient Greek sense – where they feel compelled to respond to an increasingly turbulent situation with radical policy measures. The interplay of the three elements creates a surge of political will, that elusive ingredient of change.

History tells us that this is our greatest hope for the kind of green Marshall Plan that a crisis such as the planetary ecological emergency calls for. This is not a time for lukewarm reform or ‘proportionate responses’. ‘The crucial problems of our time no longer can be left to simmer on the low flame of gradualism,’ wrote the historian Howard Zinn in 1966. If we are to bend rather than break over the coming decades, we will need rebellious movements and system-changing ideas to coalesce with the environmental crisis into a Great Disruption that redirects humanity towards an ecological civilisation.

Will we rise to the challenge? Here it is useful to make a distinction between optimism and hope. We can think of optimism as a glass-half-full attitude that everything will be fine despite the evidence. I’m far from optimistic. As Peter Frankopan concludes in The Earth Transformed (2023): ‘Much of human history has been about the failure to understand or adapt to changing circumstances in the physical and natural world around us.’ That is why the great ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia and the Yucatán peninsula have disappeared.

On the other hand, I am a believer in radical hope, by which I mean recognising that the chances of success may be slim but still being driven to act by the values and vision you are rooted in. Time and again, humankind has risen up collectively, often against the odds, to tackle shared problems and overcome crises.

The challenge we face as a civilisation is to draw on history for tomorrow, and turn radical hope into action.

History of ideas

Baffled by human diversity

Confused 17th-century Europeans argued that human groups were separately created, a precursor to racist thought today

Jacob Zellmer

Archaeology

Beyond kingdoms and empires

A revolution in archaeology is transforming our picture of past populations and the scope of human freedoms

David Wengrow

Meaning and the good life

Philosophy was once alive

I was searching for meaning and purpose so I became an academic philosopher. Reader, you might guess what happened next

Pranay Sanklecha

History of technology

Learning to love monsters

Windmills were once just machines on the land but now seem delightfully bucolic. Could wind turbines win us over too?

Stephen Case

Global history

The route to progress

Anticolonial modernity was founded upon the fight for liberation from communists, capitalists and imperialists alike

Frank Gerits

Thinkers and theories

Paper trails

Husserl’s well-tended archive has given him a rich afterlife, while Nietzsche’s was distorted by his axe-grinding sister

Peter Salmon

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications