Reading & Math for K-5

- Kindergarten

- Learning numbers

- Comparing numbers

- Place Value

- Roman numerals

- Subtraction

- Multiplication

- Order of operations

- Drills & practice

- Measurement

- Factoring & prime factors

- Proportions

- Shape & geometry

- Data & graphing

- Word problems

- Children's stories

- Leveled Stories

- Sentences & passages

- Context clues

- Cause & effect

- Compare & contrast

- Fact vs. fiction

- Fact vs. opinion

- Main idea & details

- Story elements

- Conclusions & inferences

- Sounds & phonics

- Words & vocabulary

- Reading comprehension

- Early writing

- Numbers & counting

- Simple math

- Social skills

- Other activities

- Dolch sight words

- Fry sight words

- Multiple meaning words

- Prefixes & suffixes

- Vocabulary cards

- Other parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Capitalization

- Narrative writing

- Opinion writing

- Informative writing

- Cursive alphabet

- Cursive letters

- Cursive letter joins

- Cursive words

- Cursive sentences

- Cursive passages

- Grammar & Writing

Download & Print From Only $1.79

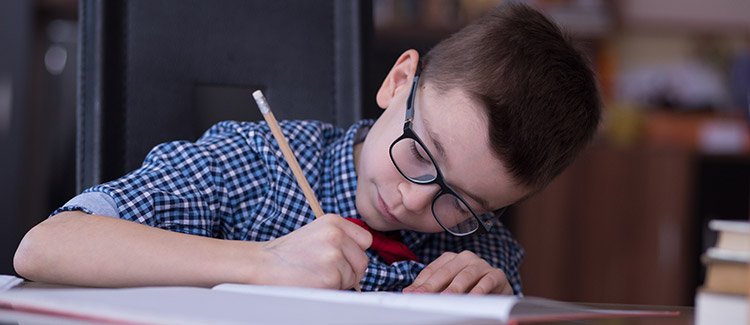

Free Worksheets for Kids

| For practicing some math skills, there is nothing more effective than a pencil and paper. Our free math worksheets for grades 1-6 cover math skills from counting and basic numeracy through advanced topics such as fractions and decimals. | |

| Use our reading comprehension worksheets to improve reading skills. Free stories followed by exercises, as well as worksheets on specific comprehension topics. | |

| Our printable preschool and kindergarten worksheets help kids learn their letters, numbers, shapes, colors and other basic skills. | |

| Our vocabulary worksheets provide vocabulary, word recognition and word usage exercises for grades 1-5. | |

| Our spelling worksheets help kids practice and improve spelling, a skill foundational to reading and writing. Spelling lists for each grade are provided. | |

| Learn about the parts of speech, sentences, capitalization and punctuation with our free & printable grammar and writing worksheets. | |

| Our free science worksheets Introduce concepts in the life sciences, earth sciences and physical sciences. Currently we have kindergarten through grade 3 science worksheets available. | |

| Kids can practice their handwriting skills with our free cursive writing worksheets. | |

| Free math flashcards and reading flashcards. |

What is K5?

K5 Learning offers free worksheets , flashcards and inexpensive workbooks for kids in kindergarten to grade 5. Become a member to access additional content and skip ads.

Our members helped us give away millions of worksheets last year.

We provide free educational materials to parents and teachers in over 100 countries. If you can, please consider purchasing a membership ($24/year) to support our efforts.

Members skip ads and access exclusive features.

Learn about member benefits

This content is available to members only.

Join K5 to save time, skip ads and access more content. Learn More

- Forgot Password?

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

CLICK HERE TO LEARN ABOUT MTM ALL ACCESS MEMBERSHIP FOR GRADES 6-ALGEBRA 1

Maneuvering the Middle

Student-Centered Math Lessons

Grading Math Homework Made Easy

Some of the links in this post are affiliate links that support the content on this site. Read our disclosure statement for more information.

Grading math homework doesn’t have to be a hassle! It is hard to believe when you have a 150+ students, but I am sharing an organization system that will make grading math homework much more efficient. This is a follow up to my Minimalist Approach to Homework post. The title was inspired by the Marie Kondo book, The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up . Though I utilized the homework agenda for many years prior to the book, it fits right in to the idea of only keeping things that bring you joy.

One thing is for sure, papers do not bring a teacher joy.

For further reading, check out these posts about homework:

- The Homework Agenda Part 2 (Grading Math Homework)

- Should Teachers Assign Math Homework?

I am also aware that homework brings on another conversation:

- what to do if it is not complete AKA missing assignments

Any teacher will tell you that a missing assignment is a giant pain. No one enjoys seeing the blank space in the grade book, especially a middle school teacher with 125+ students. (Side note, my first year I had 157. Pretty much insane.)

Grading Homework, Yes or No?

Goodness, this is a decision you have to make for you and the best interest of your students. In my experience, I would say I graded 85% of assignments for some type of accuracy. I am not a fan of completion grades. The purpose of homework is to practice, but we don’t want to practice incorrectly. Completion grades didn’t work for me, because I didn’t want students to produce low quality work.

Students had a “tutorial” class period (much like homeroom) in which they were allowed 20 minutes a day to work on assignments. I always encouraged students to work on math or come to my room for homework help. Yes, this often led to 40+ students in my room. But, that means 40 students were doing math practice. I love that.

I also believe that many students worked on it during that time because they knew it was for a grade. This helps to build intrinsic motivation.

Grading math homework: USING THE HOMEWORK AGENDA

During the warm up, I circulated and checked for homework completion. Students would receive a stamp or my initials on their Homework Agenda. Essentially, the Homework Agenda (freebie offered later in this post) is a one-pager that kept students homework organized. As a class, we quickly graded the homework assignment. Then, I briefly would answer or discuss a difficult question or two. To avoid cheating, any student who did not have their homework that day were required to clear their desk while we graded.

I would then present a grading scale. This is where I might make math teachers crazy, but I would be generous. Eight questions, ten points each. Missing two problems would result in an 80. I tried to make it advantageous to those who showed work and attempted, yet not just a “gimme” grade.

Students would record their grade on their Homework Agenda. They would repeat this for every homework assignment that week. A completed Homework Agenda would have 4 assignments’ names, with 4 teacher completion signatures, and 4 grades for each day of the week that I assigned homework.

Later in the class or the following day as I circulated, I was able to see on the front of the Homework Agenda how students were doing and discuss personally with them whether or not they needed to see me in tutorials. I was able to give specific praise to students who were giving 110% effort or making improvements.

This is why I love the Homework Agenda.

“There is no possible way, I could collect the assignments individually and return them in a timely fashion. I tried that my first year and there was no hope. Since using it, I am quickly able to provide individual and specific feedback in a timely manner. It opens up conversations and helps be to encourage and be a champion for my students. ”

On Friday, I would collect the Homework Agenda. If during the week you were absent, had an incomplete assignment, or didn’t complete one, Friday was D day. It was going in the grade book on Friday.

Here is my weekly process:

- Collect homework agendas

- Have frank conversation with students who did not have it

- Record grades on paper (mostly to make putting it in the computer faster because they were ordered)

- Record grades in computer

- Send the same email to parents of students that did not turn in the agenda – write one email, then BCC names.

- List names of missing assignments on post-it note next to desk (official, I know)

- Pull students from tutorial time (homeroom) who owed me the homework

- Follow up with any students who were absent Friday and still needed to turn in their homework to me

What About the Missi ng Assignments?

Yes, there will be missing assignments. Yes, students will come to Thursday and have lost their precious agenda. However, it won’t happen often to the same kiddo. My least organized student, who carried everything in their pocket, could fold that agenda up and hang onto it for a week. It was too valuable. Too many grades, too many assignments to redo.

We all know that it is much more work when students don’t complete their assignments. It would be a dream world if everyone turned in their work everyday. Unfortunately, we all live in reality.

We can vent our frustrations over students not doing work, which is legitimate. We can also work towards solutions.

The reality is that not every student has a support system at home. I would love for us to be that voice of inspiration and encouragement. Sometimes that voice sounds like tough love and a hounding for assignments and just being consistent that you value their education and you are not willing to let them give up on it.

They will appreciate it one day and you will be happy you did the extra work.

Want to try the Homework Agenda? Download the template here, just type and go!

This post is part 2 in a two part series. To read part 1, click here.

Digital Math Activities

Check out these related products from my shop.

Reader Interactions

42 comments.

February 29, 2016 at 2:39 pm

How do you prevent kids from cheating and writing a better grade than deserved? And you said 8 questions 10 points each, so do you then give them 20 points for attempting for making it an even 100?

March 1, 2016 at 2:46 am

Hi Lisa, thanks for the question. You make a great point about students wanting to write a better grade than they earned. The first few weeks, I really talk about what it means to be honest and check over their shoulders. As I walk around to check I will make sure everyone is marking their assignment correctly. I even will flip through what has been turned in on Fridays and double check or “spot” check. After several years of doing this, I can only count a handful of times when I had to deal with a situation. You would be surprised! Yes, I tried to make everything easy to grade as well as giving points for effort, especially if the assignment was difficult. Hope that helps!

May 20, 2016 at 10:03 pm

So do you have students turn in all the papers on friday as well or just the agenda? How do you spot check if you only collect the agenda?

May 20, 2016 at 10:38 pm

Hi Heather! Yes, I have students turn in their work with the agenda. If it was a handout/worksheet I provided, I just set the copier to staple it to the back. If it was something out of a text book, they would staple it to the agenda. Hope that helps!

June 4, 2016 at 9:42 pm

The ‘initials’ box on the homework agenda is for you to sign when checking who has it done? Or is the person correcting the paper initializing it?

Do you take off points for students not having an assignment done by the time Friday rolls around? Also, what does the small 1’s and 2’s in the corner of your gradebook mean?

June 5, 2016 at 6:56 am

Hi Alysia! I use the initials box to sign or stamp that it was complete before we graded it. I think you could have the student grading do that, but then you wouldn’t have a good grasp on how kids were doing throughout the week. I really liked going around at the beginning of class and touching base with students/seeing who needed extra help. Yes, I took off points for turing it in late. We had a standard policy on our campus that I followed. Also, by not having initials, it was by default late because it didn’t get checked when I came around. This section of my gradebook was during review for state testing, so the 1’s and 2’s were a little incentive I was running in my classroom. Review can be so boring and tedious, so I tried to spice it up with a sticker/point system for effort and making improvement. Hope this helps!

August 15, 2016 at 6:27 pm

I’m a bit confused how you assigned a grade to the homework assignment. First, you mentioned each problem was assigned 10 points. How did you determine how many points students would receive for each problem? If I read your blog correctly it sounds like you had the students score the assignment, how did you instruct them to score each problem? With 10 points for each problem it seems like there is a potential to have a wide range of scores for each problem based on who is grading it. Also, did the grader score it or did the student give their own work a grade? Sorry for all the questions…thank you!

August 16, 2016 at 6:43 am

Hi Tanya! In my example, there were eight problems but I only counted each as being worth ten points. That would be twenty points left over for trying/showing work/etc. As for marking it, each problem incorrect would be ten points off. Hope that helps. You could have either the student self grade or do a trade and grade method, whichever you felt more comfortable with.

November 28, 2016 at 1:28 am

Can you explain your grading system in the photo on this page where it reads, “Grading without the stacks of paper”? What do the small 1, 2 and 3’s mean? I assume your method on this posting is to avoid the complicated grading, but you’ve got me curious now about what method you were using in your photo. Thanks for clarifying this for me.

January 2, 2017 at 9:48 pm

The small numbers in the corner were used for an incentive. This photo is from a state assessment prep and I used various points for incentives to keep working!

December 26, 2016 at 7:31 pm

I like the idea of trade and grade. Right not I just check hw for completion and they get 5 points for doing the assignment. I treat this like extra credit for them. Most of them will at least attempt the problems and show their work. We also talk about just writing random numbers and how that will get no points.

December 26, 2016 at 7:34 pm

Ugh! The name is Celeste

March 11, 2017 at 7:25 pm

We aren’t allowed to do trade and grade due to privacy issues and legal issues. Otherwise, I do like this idea.

April 1, 2017 at 2:33 pm

I have heard that from other teachers. You could have them check their own, too.

May 30, 2017 at 3:19 pm

Do you allow them to redo and make corrections to their work for credit back? Or does the grade stand no matter what? This is why I go back and forth between correctness and completion. While they need to practice correctly, I don’t like being punitive for getting the answers wrong when they are learning the material for the first time. I want them to practice, and practice correctly. But I also want them to be motivated to persevere and relearn until they master the material.

June 4, 2017 at 6:10 am

Yes, it depended on the school policy but I would typically drop the lowest homework grade at the end of the grading period. If a student is willing to come in and work on their assignment (redo, a new one, etc), then I was always thrilled and would replace the grade! We want kids to learn from their mistakes. 🙂

June 4, 2017 at 1:48 pm

Regarding grading homework, my students have three homework assignments each week, with between 8 and 13 practice problems per assignment. I go through each problem and award 0-3 points per problem. 0 points if they did nothing. And then 1 point for attempting the problem, 1 point for showing necessary/appropriate work, and 1 point for a correct answer. This way, even if students get the problem wrong, they can still get 2 out of 3 points. If a student got each problem wrong, but were clearly trying, I would give them an overall grade of 70%.

June 20, 2017 at 8:13 pm

Great ideas! Love that!

August 31, 2019 at 8:27 am

Are you grading that, or the students?!?!

March 15, 2024 at 10:44 am

It depends! Usually I had my students grade!

June 15, 2017 at 4:54 pm

Do you staple the agenda to a homework packet to hand out on Monday?

June 20, 2017 at 8:07 pm

Yes! Well actually, I would copy it all together or if it was out of a text book, they would staple their work.

June 19, 2017 at 12:16 am

Our district insists that we MUST allow students an opportunity to complete assignments, and we have to accept them late. They do not specify how late though. I was bogged down with tons of late work this last year, and hated it. Can you please share with me your secret of how you handle late work, how late can it be, how much credit does it receive, and how do you grade it? That would help me tremendously. Thank You!

June 20, 2017 at 8:00 pm

We always had school policies for the amount of credit a student could earn, so I would follow that for credit. As far as actually collecting and grading, I did the following: 1. If it was late, I didn’t sign their assignment sheet. Instead I wrote late. 2. They had until Friday, when I collected the assignment sheet and homework to complete it. 3. On Friday, I would collect everything complete or not, and put grades in the grade book. Then, I would send an email to parents letting them know. Usually, kids would then be motivated to come to tutoring to complete any missing grades. I tried to not take any papers other than the Assignment Sheet and its corresponding work.

August 11, 2019 at 2:47 pm

If the students came in the next week and finished the missing assignment, would you give them full points or would they still lose some points for turning the assignment in late?

March 15, 2024 at 10:47 am

Hi, Jackie! I would go with your school’s grading policy.

August 12, 2018 at 1:55 pm

I really hate taking late work but when im forced to I tell my students that the highest grade they could receive is 5 points lower than the lowest grade fromthe student that turned it in on time.

July 17, 2017 at 3:30 pm

What percentage of their overall grade is homework? We are only allowed to give 10% which is why I only grade for completion and showing work. Maybe I’m not understanding correctly, but you have 80 points per assignment roughly?

August 11, 2017 at 5:26 am

Yes, I really tried to be generous and would give points for showing work/effort, to make the grading scale easy. Thanks!

July 30, 2017 at 9:07 pm

Love all the ideas. One question though – do you have any problems with kids not having their homework done, but making note of the correct answers while the class is grading and then just copying those answers later?

August 11, 2017 at 5:18 am

I would suggest to monitor and ask them to have a cleaned off desk if they did not have their assignment. Thanks!

August 22, 2017 at 11:37 am

What does your class look like on Fridays? If you only assign homework M-Th, when do your students get practice on the material that you teach on Friday?

September 2, 2017 at 9:01 pm

Hi Briana! I didn’t assign homework on Fridays, and really tried to plan for a cooperative learning activity if possible. This way we could practice what we did all week.

August 5, 2019 at 9:21 am

I love the idea of the homework agenda. I tried passing out papers and filing them but it was to time consuming. If students are allowed to take the packet back and forth every day what keeps them from sharing their answers to other students from another class period throughout the day? I love that you can put notes/reminders at the bottom of the agenda page.

June 11, 2018 at 11:07 am

Hello! Do you have a editable copy if your homework agenda anywhere? It seems like an interesting concept. I would love to see the overall layout.

March 15, 2024 at 10:13 am

Yes! You can get it here: https://www.maneuveringthemiddle.com/math-homework/

June 13, 2018 at 7:39 pm

What are your procedures for the agenda for those students who were absent the day you graded?

Hi, Brittany! What a great question. I would just collect any absent students’ packets when they return and grade them on my own.

December 2, 2018 at 11:21 am

I often give homework on Quizizz or EdPuzzle which scores for me. The kids who cannot do the assignment at home due to computer or internet issues can do it in tutoring. (I offer before school, after school, and lunch opportunities for tutoring.)

December 9, 2018 at 9:16 pm

How do you set up your homework agenda? In the date box do you put the due date? Or the date they receive the assignment? Do you have an example homework agenda?

December 22, 2018 at 11:34 am

Hi Alyssa! Yes, check out this blog post for more ideas and a sample: https://www.maneuveringthemiddle.com/math-homework/

August 20, 2019 at 11:41 pm

How and when in this process do you grade the homework for accuracy? At your quick glance at the start of class? On Friday after you collect the agenda and associated work? What mechanism do you use to provide constructive, timely feedback to the students?

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

How to Do Homework: 15 Expert Tips and Tricks

Coursework/GPA

Everyone struggles with homework sometimes, but if getting your homework done has become a chronic issue for you, then you may need a little extra help. That’s why we’ve written this article all about how to do homework. Once you’re finished reading it, you’ll know how to do homework (and have tons of new ways to motivate yourself to do homework)!

We’ve broken this article down into a few major sections. You’ll find:

- A diagnostic test to help you figure out why you’re struggling with homework

- A discussion of the four major homework problems students face, along with expert tips for addressing them

- A bonus section with tips for how to do homework fast

By the end of this article, you’ll be prepared to tackle whatever homework assignments your teachers throw at you .

So let’s get started!

How to Do Homework: Figure Out Your Struggles

Sometimes it feels like everything is standing between you and getting your homework done. But the truth is, most people only have one or two major roadblocks that are keeping them from getting their homework done well and on time.

The best way to figure out how to get motivated to do homework starts with pinpointing the issues that are affecting your ability to get your assignments done. That’s why we’ve developed a short quiz to help you identify the areas where you’re struggling.

Take the quiz below and record your answers on your phone or on a scrap piece of paper. Keep in mind there are no wrong answers!

1. You’ve just been assigned an essay in your English class that’s due at the end of the week. What’s the first thing you do?

A. Keep it in mind, even though you won’t start it until the day before it’s due B. Open up your planner. You’ve got to figure out when you’ll write your paper since you have band practice, a speech tournament, and your little sister’s dance recital this week, too. C. Groan out loud. Another essay? You could barely get yourself to write the last one! D. Start thinking about your essay topic, which makes you think about your art project that’s due the same day, which reminds you that your favorite artist might have just posted to Instagram...so you better check your feed right now.

2. Your mom asked you to pick up your room before she gets home from work. You’ve just gotten home from school. You decide you’ll tackle your chores:

A. Five minutes before your mom walks through the front door. As long as it gets done, who cares when you start? B. As soon as you get home from your shift at the local grocery store. C. After you give yourself a 15-minute pep talk about how you need to get to work. D. You won’t get it done. Between texts from your friends, trying to watch your favorite Netflix show, and playing with your dog, you just lost track of time!

3. You’ve signed up to wash dogs at the Humane Society to help earn money for your senior class trip. You:

A. Show up ten minutes late. You put off leaving your house until the last minute, then got stuck in unexpected traffic on the way to the shelter. B. Have to call and cancel at the last minute. You forgot you’d already agreed to babysit your cousin and bake cupcakes for tomorrow’s bake sale. C. Actually arrive fifteen minutes early with extra brushes and bandanas you picked up at the store. You’re passionate about animals, so you’re excited to help out! D. Show up on time, but only get three dogs washed. You couldn’t help it: you just kept getting distracted by how cute they were!

4. You have an hour of downtime, so you decide you’re going to watch an episode of The Great British Baking Show. You:

A. Scroll through your social media feeds for twenty minutes before hitting play, which means you’re not able to finish the whole episode. Ugh! You really wanted to see who was sent home! B. Watch fifteen minutes until you remember you’re supposed to pick up your sister from band practice before heading to your part-time job. No GBBO for you! C. You finish one episode, then decide to watch another even though you’ve got SAT studying to do. It’s just more fun to watch people make scones. D. Start the episode, but only catch bits and pieces of it because you’re reading Twitter, cleaning out your backpack, and eating a snack at the same time.

5. Your teacher asks you to stay after class because you’ve missed turning in two homework assignments in a row. When she asks you what’s wrong, you say:

A. You planned to do your assignments during lunch, but you ran out of time. You decided it would be better to turn in nothing at all than submit unfinished work. B. You really wanted to get the assignments done, but between your extracurriculars, family commitments, and your part-time job, your homework fell through the cracks. C. You have a hard time psyching yourself to tackle the assignments. You just can’t seem to find the motivation to work on them once you get home. D. You tried to do them, but you had a hard time focusing. By the time you realized you hadn’t gotten anything done, it was already time to turn them in.

Like we said earlier, there are no right or wrong answers to this quiz (though your results will be better if you answered as honestly as possible). Here’s how your answers break down:

- If your answers were mostly As, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is procrastination.

- If your answers were mostly Bs, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is time management.

- If your answers were mostly Cs, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is motivation.

- If your answers were mostly Ds, then your biggest struggle with doing homework is getting distracted.

Now that you’ve identified why you’re having a hard time getting your homework done, we can help you figure out how to fix it! Scroll down to find your core problem area to learn more about how you can start to address it.

And one more thing: you’re really struggling with homework, it’s a good idea to read through every section below. You may find some additional tips that will help make homework less intimidating.

How to Do Homework When You’re a Procrastinator

Merriam Webster defines “procrastinate” as “to put off intentionally and habitually.” In other words, procrastination is when you choose to do something at the last minute on a regular basis. If you’ve ever found yourself pulling an all-nighter, trying to finish an assignment between periods, or sprinting to turn in a paper minutes before a deadline, you’ve experienced the effects of procrastination.

If you’re a chronic procrastinator, you’re in good company. In fact, one study found that 70% to 95% of undergraduate students procrastinate when it comes to doing their homework. Unfortunately, procrastination can negatively impact your grades. Researchers have found that procrastination can lower your grade on an assignment by as much as five points ...which might not sound serious until you realize that can mean the difference between a B- and a C+.

Procrastination can also negatively affect your health by increasing your stress levels , which can lead to other health conditions like insomnia, a weakened immune system, and even heart conditions. Getting a handle on procrastination can not only improve your grades, it can make you feel better, too!

The big thing to understand about procrastination is that it’s not the result of laziness. Laziness is defined as being “disinclined to activity or exertion.” In other words, being lazy is all about doing nothing. But a s this Psychology Today article explains , procrastinators don’t put things off because they don’t want to work. Instead, procrastinators tend to postpone tasks they don’t want to do in favor of tasks that they perceive as either more important or more fun. Put another way, procrastinators want to do things...as long as it’s not their homework!

3 Tips f or Conquering Procrastination

Because putting off doing homework is a common problem, there are lots of good tactics for addressing procrastination. Keep reading for our three expert tips that will get your homework habits back on track in no time.

#1: Create a Reward System

Like we mentioned earlier, procrastination happens when you prioritize other activities over getting your homework done. Many times, this happens because homework...well, just isn’t enjoyable. But you can add some fun back into the process by rewarding yourself for getting your work done.

Here’s what we mean: let’s say you decide that every time you get your homework done before the day it’s due, you’ll give yourself a point. For every five points you earn, you’ll treat yourself to your favorite dessert: a chocolate cupcake! Now you have an extra (delicious!) incentive to motivate you to leave procrastination in the dust.

If you’re not into cupcakes, don’t worry. Your reward can be anything that motivates you . Maybe it’s hanging out with your best friend or an extra ten minutes of video game time. As long as you’re choosing something that makes homework worth doing, you’ll be successful.

#2: Have a Homework Accountability Partner

If you’re having trouble getting yourself to start your homework ahead of time, it may be a good idea to call in reinforcements . Find a friend or classmate you can trust and explain to them that you’re trying to change your homework habits. Ask them if they’d be willing to text you to make sure you’re doing your homework and check in with you once a week to see if you’re meeting your anti-procrastination goals.

Sharing your goals can make them feel more real, and an accountability partner can help hold you responsible for your decisions. For example, let’s say you’re tempted to put off your science lab write-up until the morning before it’s due. But you know that your accountability partner is going to text you about it tomorrow...and you don’t want to fess up that you haven’t started your assignment. A homework accountability partner can give you the extra support and incentive you need to keep your homework habits on track.

#3: Create Your Own Due Dates

If you’re a life-long procrastinator, you might find that changing the habit is harder than you expected. In that case, you might try using procrastination to your advantage! If you just can’t seem to stop doing your work at the last minute, try setting your own due dates for assignments that range from a day to a week before the assignment is actually due.

Here’s what we mean. Let’s say you have a math worksheet that’s been assigned on Tuesday and is due on Friday. In your planner, you can write down the due date as Thursday instead. You may still put off your homework assignment until the last minute...but in this case, the “last minute” is a day before the assignment’s real due date . This little hack can trick your procrastination-addicted brain into planning ahead!

If you feel like Kevin Hart in this meme, then our tips for doing homework when you're busy are for you.

How to Do Homework When You’re too Busy

If you’re aiming to go to a top-tier college , you’re going to have a full plate. Because college admissions is getting more competitive, it’s important that you’re maintaining your grades , studying hard for your standardized tests , and participating in extracurriculars so your application stands out. A packed schedule can get even more hectic once you add family obligations or a part-time job to the mix.

If you feel like you’re being pulled in a million directions at once, you’re not alone. Recent research has found that stress—and more severe stress-related conditions like anxiety and depression— are a major problem for high school students . In fact, one study from the American Psychological Association found that during the school year, students’ stress levels are higher than those of the adults around them.

For students, homework is a major contributor to their overall stress levels . Many high schoolers have multiple hours of homework every night , and figuring out how to fit it into an already-packed schedule can seem impossible.

3 Tips for Fitting Homework Into Your Busy Schedule

While it might feel like you have literally no time left in your schedule, there are still ways to make sure you’re able to get your homework done and meet your other commitments. Here are our expert homework tips for even the busiest of students.

#1: Make a Prioritized To-Do List

You probably already have a to-do list to keep yourself on track. The next step is to prioritize the items on your to-do list so you can see what items need your attention right away.

Here’s how it works: at the beginning of each day, sit down and make a list of all the items you need to get done before you go to bed. This includes your homework, but it should also take into account any practices, chores, events, or job shifts you may have. Once you get everything listed out, it’s time to prioritize them using the labels A, B, and C. Here’s what those labels mean:

- A Tasks : tasks that have to get done—like showing up at work or turning in an assignment—get an A.

- B Tasks : these are tasks that you would like to get done by the end of the day but aren’t as time sensitive. For example, studying for a test you have next week could be a B-level task. It’s still important, but it doesn’t have to be done right away.

- C Tasks: these are tasks that aren’t very important and/or have no real consequences if you don’t get them done immediately. For instance, if you’re hoping to clean out your closet but it’s not an assigned chore from your parents, you could label that to-do item with a C.

Prioritizing your to-do list helps you visualize which items need your immediate attention, and which items you can leave for later. A prioritized to-do list ensures that you’re spending your time efficiently and effectively, which helps you make room in your schedule for homework. So even though you might really want to start making decorations for Homecoming (a B task), you’ll know that finishing your reading log (an A task) is more important.

#2: Use a Planner With Time Labels

Your planner is probably packed with notes, events, and assignments already. (And if you’re not using a planner, it’s time to start!) But planners can do more for you than just remind you when an assignment is due. If you’re using a planner with time labels, it can help you visualize how you need to spend your day.

A planner with time labels breaks your day down into chunks, and you assign tasks to each chunk of time. For example, you can make a note of your class schedule with assignments, block out time to study, and make sure you know when you need to be at practice. Once you know which tasks take priority, you can add them to any empty spaces in your day.

Planning out how you spend your time not only helps you use it wisely, it can help you feel less overwhelmed, too . We’re big fans of planners that include a task list ( like this one ) or have room for notes ( like this one ).

#3: Set Reminders on Your Phone

If you need a little extra nudge to make sure you’re getting your homework done on time, it’s a good idea to set some reminders on your phone. You don’t need a fancy app, either. You can use your alarm app to have it go off at specific times throughout the day to remind you to do your homework. This works especially well if you have a set homework time scheduled. So if you’ve decided you’re doing homework at 6:00 pm, you can set an alarm to remind you to bust out your books and get to work.

If you use your phone as your planner, you may have the option to add alerts, emails, or notifications to scheduled events . Many calendar apps, including the one that comes with your phone, have built-in reminders that you can customize to meet your needs. So if you block off time to do your homework from 4:30 to 6:00 pm, you can set a reminder that will pop up on your phone when it’s time to get started.

This dog isn't judging your lack of motivation...but your teacher might. Keep reading for tips to help you motivate yourself to do your homework.

How to Do Homework When You’re Unmotivated

At first glance, it may seem like procrastination and being unmotivated are the same thing. After all, both of these issues usually result in you putting off your homework until the very last minute.

But there’s one key difference: many procrastinators are working, they’re just prioritizing work differently. They know they’re going to start their homework...they’re just going to do it later.

Conversely, people who are unmotivated to do homework just can’t find the willpower to tackle their assignments. Procrastinators know they’ll at least attempt the homework at the last minute, whereas people who are unmotivated struggle with convincing themselves to do it at a ll. For procrastinators, the stress comes from the inevitable time crunch. For unmotivated people, the stress comes from trying to convince themselves to do something they don’t want to do in the first place.

Here are some common reasons students are unmotivated in doing homework :

- Assignments are too easy, too hard, or seemingly pointless

- Students aren’t interested in (or passionate about) the subject matter

- Students are intimidated by the work and/or feels like they don’t understand the assignment

- Homework isn’t fun, and students would rather spend their time on things that they enjoy

To sum it up: people who lack motivation to do their homework are more likely to not do it at all, or to spend more time worrying about doing their homework than...well, actually doing it.

3 Tips for How to Get Motivated to Do Homework

The key to getting homework done when you’re unmotivated is to figure out what does motivate you, then apply those things to homework. It sounds tricky...but it’s pretty simple once you get the hang of it! Here are our three expert tips for motivating yourself to do your homework.

#1: Use Incremental Incentives

When you’re not motivated, it’s important to give yourself small rewards to stay focused on finishing the task at hand. The trick is to keep the incentives small and to reward yourself often. For example, maybe you’re reading a good book in your free time. For every ten minutes you spend on your homework, you get to read five pages of your book. Like we mentioned earlier, make sure you’re choosing a reward that works for you!

So why does this technique work? Using small rewards more often allows you to experience small wins for getting your work done. Every time you make it to one of your tiny reward points, you get to celebrate your success, which gives your brain a boost of dopamine . Dopamine helps you stay motivated and also creates a feeling of satisfaction when you complete your homework !

#2: Form a Homework Group

If you’re having trouble motivating yourself, it’s okay to turn to others for support. Creating a homework group can help with this. Bring together a group of your friends or classmates, and pick one time a week where you meet and work on homework together. You don’t have to be in the same class, or even taking the same subjects— the goal is to encourage one another to start (and finish!) your assignments.

Another added benefit of a homework group is that you can help one another if you’re struggling to understand the material covered in your classes. This is especially helpful if your lack of motivation comes from being intimidated by your assignments. Asking your friends for help may feel less scary than talking to your teacher...and once you get a handle on the material, your homework may become less frightening, too.

#3: Change Up Your Environment

If you find that you’re totally unmotivated, it may help if you find a new place to do your homework. For example, if you’ve been struggling to get your homework done at home, try spending an extra hour in the library after school instead. The change of scenery can limit your distractions and give you the energy you need to get your work done.

If you’re stuck doing homework at home, you can still use this tip. For instance, maybe you’ve always done your homework sitting on your bed. Try relocating somewhere else, like your kitchen table, for a few weeks. You may find that setting up a new “homework spot” in your house gives you a motivational lift and helps you get your work done.

Social media can be a huge problem when it comes to doing homework. We have advice for helping you unplug and regain focus.

How to Do Homework When You’re Easily Distracted

We live in an always-on world, and there are tons of things clamoring for our attention. From friends and family to pop culture and social media, it seems like there’s always something (or someone!) distracting us from the things we need to do.

The 24/7 world we live in has affected our ability to focus on tasks for prolonged periods of time. Research has shown that over the past decade, an average person’s attention span has gone from 12 seconds to eight seconds . And when we do lose focus, i t takes people a long time to get back on task . One study found that it can take as long as 23 minutes to get back to work once we’ve been distracte d. No wonder it can take hours to get your homework done!

3 Tips to Improve Your Focus

If you have a hard time focusing when you’re doing your homework, it’s a good idea to try and eliminate as many distractions as possible. Here are three expert tips for blocking out the noise so you can focus on getting your homework done.

#1: Create a Distraction-Free Environment

Pick a place where you’ll do your homework every day, and make it as distraction-free as possible. Try to find a location where there won’t be tons of noise, and limit your access to screens while you’re doing your homework. Put together a focus-oriented playlist (or choose one on your favorite streaming service), and put your headphones on while you work.

You may find that other people, like your friends and family, are your biggest distraction. If that’s the case, try setting up some homework boundaries. Let them know when you’ll be working on homework every day, and ask them if they’ll help you keep a quiet environment. They’ll be happy to lend a hand!

#2: Limit Your Access to Technology

We know, we know...this tip isn’t fun, but it does work. For homework that doesn’t require a computer, like handouts or worksheets, it’s best to put all your technology away . Turn off your television, put your phone and laptop in your backpack, and silence notifications on any wearable tech you may be sporting. If you listen to music while you work, that’s fine...but make sure you have a playlist set up so you’re not shuffling through songs once you get started on your homework.

If your homework requires your laptop or tablet, it can be harder to limit your access to distractions. But it’s not impossible! T here are apps you can download that will block certain websites while you’re working so that you’re not tempted to scroll through Twitter or check your Facebook feed. Silence notifications and text messages on your computer, and don’t open your email account unless you absolutely have to. And if you don’t need access to the internet to complete your assignments, turn off your WiFi. Cutting out the online chatter is a great way to make sure you’re getting your homework done.

#3: Set a Timer (the Pomodoro Technique)

Have you ever heard of the Pomodoro technique ? It’s a productivity hack that uses a timer to help you focus!

Here’s how it works: first, set a timer for 25 minutes. This is going to be your work time. During this 25 minutes, all you can do is work on whatever homework assignment you have in front of you. No email, no text messaging, no phone calls—just homework. When that timer goes off, you get to take a 5 minute break. Every time you go through one of these cycles, it’s called a “pomodoro.” For every four pomodoros you complete, you can take a longer break of 15 to 30 minutes.

The pomodoro technique works through a combination of boundary setting and rewards. First, it gives you a finite amount of time to focus, so you know that you only have to work really hard for 25 minutes. Once you’ve done that, you’re rewarded with a short break where you can do whatever you want. Additionally, tracking how many pomodoros you complete can help you see how long you’re really working on your homework. (Once you start using our focus tips, you may find it doesn’t take as long as you thought!)

Two Bonus Tips for How to Do Homework Fast

Even if you’re doing everything right, there will be times when you just need to get your homework done as fast as possible. (Why do teachers always have projects due in the same week? The world may never know.)

The problem with speeding through homework is that it’s easy to make mistakes. While turning in an assignment is always better than not submitting anything at all, you want to make sure that you’re not compromising quality for speed. Simply put, the goal is to get your homework done quickly and still make a good grade on the assignment!

Here are our two bonus tips for getting a decent grade on your homework assignments , even when you’re in a time crunch.

#1: Do the Easy Parts First

This is especially true if you’re working on a handout with multiple questions. Before you start working on the assignment, read through all the questions and problems. As you do, make a mark beside the questions you think are “easy” to answer .

Once you’ve finished going through the whole assignment, you can answer these questions first. Getting the easy questions out of the way as quickly as possible lets you spend more time on the trickier portions of your homework, which will maximize your assignment grade.

(Quick note: this is also a good strategy to use on timed assignments and tests, like the SAT and the ACT !)

#2: Pay Attention in Class

Homework gets a lot easier when you’re actively learning the material. Teachers aren’t giving you homework because they’re mean or trying to ruin your weekend... it’s because they want you to really understand the course material. Homework is designed to reinforce what you’re already learning in class so you’ll be ready to tackle harder concepts later.

When you pay attention in class, ask questions, and take good notes, you’re absorbing the information you’ll need to succeed on your homework assignments. (You’re stuck in class anyway, so you might as well make the most of it!) Not only will paying attention in class make your homework less confusing, it will also help it go much faster, too.

What’s Next?

If you’re looking to improve your productivity beyond homework, a good place to begin is with time management. After all, we only have so much time in a day...so it’s important to get the most out of it! To get you started, check out this list of the 12 best time management techniques that you can start using today.

You may have read this article because homework struggles have been affecting your GPA. Now that you’re on the path to homework success, it’s time to start being proactive about raising your grades. This article teaches you everything you need to know about raising your GPA so you can

Now you know how to get motivated to do homework...but what about your study habits? Studying is just as critical to getting good grades, and ultimately getting into a good college . We can teach you how to study bette r in high school. (We’ve also got tons of resources to help you study for your ACT and SAT exams , too!)

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Does homework really work?

by: Leslie Crawford | Updated: December 12, 2023

Print article

You know the drill. It’s 10:15 p.m., and the cardboard-and-toothpick Golden Gate Bridge is collapsing. The pages of polynomials have been abandoned. The paper on the Battle of Waterloo seems to have frozen in time with Napoleon lingering eternally over his breakfast at Le Caillou. Then come the tears and tantrums — while we parents wonder, Does the gain merit all this pain? Is this just too much homework?

However the drama unfolds night after night, year after year, most parents hold on to the hope that homework (after soccer games, dinner, flute practice, and, oh yes, that childhood pastime of yore known as playing) advances their children academically.

But what does homework really do for kids? Is the forest’s worth of book reports and math and spelling sheets the average American student completes in their 12 years of primary schooling making a difference? Or is it just busywork?

Homework haterz

Whether or not homework helps, or even hurts, depends on who you ask. If you ask my 12-year-old son, Sam, he’ll say, “Homework doesn’t help anything. It makes kids stressed-out and tired and makes them hate school more.”

Nothing more than common kid bellyaching?

Maybe, but in the fractious field of homework studies, it’s worth noting that Sam’s sentiments nicely synopsize one side of the ivory tower debate. Books like The End of Homework , The Homework Myth , and The Case Against Homework the film Race to Nowhere , and the anguished parent essay “ My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me ” make the case that homework, by taking away precious family time and putting kids under unneeded pressure, is an ineffective way to help children become better learners and thinkers.

One Canadian couple took their homework apostasy all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. After arguing that there was no evidence that it improved academic performance, they won a ruling that exempted their two children from all homework.

So what’s the real relationship between homework and academic achievement?

How much is too much?

To answer this question, researchers have been doing their homework on homework, conducting and examining hundreds of studies. Chris Drew Ph.D., founder and editor at The Helpful Professor recently compiled multiple statistics revealing the folly of today’s after-school busy work. Does any of the data he listed below ring true for you?

• 45 percent of parents think homework is too easy for their child, primarily because it is geared to the lowest standard under the Common Core State Standards .

• 74 percent of students say homework is a source of stress , defined as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss, and stomach problems.

• Students in high-performing high schools spend an average of 3.1 hours a night on homework , even though 1 to 2 hours is the optimal duration, according to a peer-reviewed study .

Not included in the list above is the fact many kids have to abandon activities they love — like sports and clubs — because homework deprives them of the needed time to enjoy themselves with other pursuits.

Conversely, The Helpful Professor does list a few pros of homework, noting it teaches discipline and time management, and helps parents know what’s being taught in the class.

The oft-bandied rule on homework quantity — 10 minutes a night per grade (starting from between 10 to 20 minutes in first grade) — is listed on the National Education Association’s website and the National Parent Teacher Association’s website , but few schools follow this rule.

Do you think your child is doing excessive homework? Harris Cooper Ph.D., author of a meta-study on homework , recommends talking with the teacher. “Often there is a miscommunication about the goals of homework assignments,” he says. “What appears to be problematic for kids, why they are doing an assignment, can be cleared up with a conversation.” Also, Cooper suggests taking a careful look at how your child is doing the assignments. It may seem like they’re taking two hours, but maybe your child is wandering off frequently to get a snack or getting distracted.

Less is often more

If your child is dutifully doing their work but still burning the midnight oil, it’s worth intervening to make sure your child gets enough sleep. A 2012 study of 535 high school students found that proper sleep may be far more essential to brain and body development.

For elementary school-age children, Cooper’s research at Duke University shows there is no measurable academic advantage to homework. For middle-schoolers, Cooper found there is a direct correlation between homework and achievement if assignments last between one to two hours per night. After two hours, however, achievement doesn’t improve. For high schoolers, Cooper’s research suggests that two hours per night is optimal. If teens have more than two hours of homework a night, their academic success flatlines. But less is not better. The average high school student doing homework outperformed 69 percent of the students in a class with no homework.

Many schools are starting to act on this research. A Florida superintendent abolished homework in her 42,000 student district, replacing it with 20 minutes of nightly reading. She attributed her decision to “ solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students .”

More family time

A 2020 survey by Crayola Experience reports 82 percent of children complain they don’t have enough quality time with their parents. Homework deserves much of the blame. “Kids should have a chance to just be kids and do things they enjoy, particularly after spending six hours a day in school,” says Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth . “It’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.”

By far, the best replacement for homework — for both parents and children — is bonding, relaxing time together.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How families of color can fight for fair discipline in school

Dealing with teacher bias

The most important school data families of color need to consider

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

Because differences are our greatest strength

Homework challenges and strategies

By Amanda Morin

Expert reviewed by Jim Rein, MA

At a glance

Kids can struggle with homework for lots of reasons.

A common challenge is rushing through assignments.

Once you understand a homework challenge, it’s easier to find solutions.

Most kids struggle with homework from time to time. But kids who learn and think differently may struggle more than others. Understanding the homework challenges your child faces can help you reduce stress and avoid battles.

Here are some common homework challenges and tips to help.

The challenge: Rushing through homework

Kids with learning difficulties may rush because they’re trying to get through what’s hard for them as fast as possible. For kids with ADHD, trouble with focus and working memory may be the cause.

Rushing through homework can lead to messy or incorrect homework. It can also lead to kids missing key parts of the assignment. One thing to try is having your child do the easiest assignments first and then move to harder ones.

Get more tips for helping grade-schoolers and middle-schoolers slow down on homework.

The challenge: Taking notes

Note-taking isn’t an easy skill for some kids. They may struggle with the mechanical parts of writing or with organizing ideas on a page. Kids may also find it hard to read text and take notes at the same time.

Using the outline method may help. It divides notes into main ideas, subtopics, and details.

Explore different note-taking strategies .

The challenge: Managing time and staying organized

Some kids struggle with keeping track of time and making a plan for getting all of their work done. That’s especially true of kids who have trouble with executive function.

Try creating a homework schedule and set a specific time and place for your child to get homework done. Use a timer to help your child stay on track and get a better sense of time.

Learn about trouble with planning .

The challenge: Studying effectively

Many kids need to be taught how to study effectively. But some may need concrete strategies.

One thing to try is creating a checklist of all the steps that go into studying. Have your child mark off each one. Lists can help kids monitor their work.

Explore more study strategies for grade-schoolers and teens .

The challenge: Recalling information

Some kids have trouble holding on to information so they can use it later. (This skill is called working memory. ) They may study for hours but remember nothing the next day. But there are different types of memory.

If your child has trouble with verbal memory, try using visual study aids like graphs, maps, or drawings.

Practice “muscle memory” exercises to help kids with working memory.

The challenge: Learning independently

It’s important for kids to learn how to do homework without help. Using a homework contract can help your child set realistic goals. Encourage “thinking out loud.”

Get tips for helping grade-schoolers do schoolwork on their own.

Sometimes, homework challenges don’t go away despite your best efforts. Look for signs that kids may have too much homework . And learn how to talk with teachers about concerns .

Key takeaways

Some kids have a hard time doing schoolwork on their own.

It can help to tailor homework strategies to a child’s specific challenges and strengths.

Sometimes, there’s too much homework for a child to handle. Talk to the teacher.

Explore related topics

Filter Results

- clear all filters

Resource Type

- Worksheets

- Guided Lessons

- Lesson Plans

- Hands-on Activities

- Interactive Stories

- Online Exercises

- Printable Workbooks

- Science Projects

- Song Videos

middle-school

- Fine arts

- Foreign language

- Math

- Reading & Writing

- Science

- Social emotional

- Social studies

- Typing

- Arts & crafts

- Coloring

- Holidays

- Offline games

- Pop Culture & Events

- Seasonal

- Teacher Resources

- Common Core

Fifth Grade Worksheets and Printables

Navigate Knowledge Road Blocks with Fifth Grade Worksheets

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Inside Fiji’s Fiery Battle Against Plastics

- Column: As Biden Vies to Salvage Nomination, Growing Chorus of Democrats Say It’s Too Late

- How to Watch Lost in 2024 Without Setting Yourself Up for Disappointment

- How to Buy Groceries Without Breaking the Bank

- The Rise of the Thirst Trap Villain

- Why So Many Bitcoin Mining Companies Are Pivoting to AI

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

New content!

Review articles, unit 1: proportional relationships, unit 2: rates and percentages, unit 3: integers: addition and subtraction, unit 4: rational numbers: addition and subtraction, unit 5: negative numbers: multiplication and division, unit 6: expressions, equations, & inequalities, unit 7: statistics and probability, unit 8: scale copies, unit 9: geometry.

- Indie 102.3

More young Denver students are reading at grade level, but not as many as before the pandemic

This story was originally published by Chalkbeat . Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters .

By Melanie Asmar, Chalkbeat

After switching its elementary reading curriculum to one aligned with the science of reading, Denver Public Schools is celebrating an increase in the percentage of kindergarten through third grade students who ended the school year reading on grade level.

But the test scores are still below pre-pandemic levels — a vexing outcome the district is acknowledging by adopting a new intervention program to help the most struggling learners. Studies show that students who don’t read proficiently by third grade are less likely to graduate.

The lower test scores show the long tail of pandemic learning loss. They indicate that the pandemic not only affected children who were in school when the virus hit in early 2020, but also those who were too young to be enrolled. This past year’s third graders were preschool age when COVID shuttered school buildings across the country. This past year’s kindergarteners were babies.

In a press release, DPS reported that 61% of kindergarten through third graders this past spring were reading at grade level or above. That’s up from 58% in the spring of 2023.

But in the spring of 2019 — before the pandemic — 68% of kindergarten through third graders were reading at grade level, meaning DPS’ young students are still seven percentage points below pre-pandemic levels. Reading and writing test scores for third through 11th graders won’t be released until August, but last year’s scores showed a similar pattern.

Past early literacy data has shown wide, 30-percentage point gaps between the scores of white students and Black and Hispanic students that DPS has struggled to close. The district did not release a breakdown by race of the spring 2024 early literacy test scores.

DPS adopted a new reading curriculum

DPS first raised the alarm about the pandemic’s effects on early literacy in the fall of 2021, when test scores showed a steep drop in the percentage of young students reading at grade level. The district laid out a series of steps to address the problem, some of which were already required by a pre-pandemic push to boost early literacy statewide.