- Ebert reviews

- On This Day

The Books: A Collection of Essays , ‘Charles Dickens’, by George Orwell

On the essays shelf :

Orwell’s essay on Dickens is a monster. It could be a small book. Dickens is one of my favorite authors, and Orwell’s essay is essential reading, one of the best things ever written about Dickens. It includes observations such as this, which I think is just so right on:

No one, at any rate no English writer, has written better about childhood than Dickens. In spite of all the knowledge that has accumulated since, in spite of the fact that children are now comparatively sanely treated, no novelist has shown the same power of entering into the child’s point of view. I must have been about nine years old when I first read David Copperfield . The mental atmosphere of the opening chapters was so immediately intelligible to me that I vaguely imagined they had been written by a child . And yet when one re-reads the book as an adult and sees the Murdstones, for instance, dwindle from gigantic figures of doom into semi-comic monsters, these passages lose nothing. Dickens has been able to stand both inside and outside the child’s mind, in such a way that the same scene can be wild burlesque or sinister reality, according to the age at which one reads it.

That has been exactly my experience but I certainly couldn’t put it into words like that.

Because this is Orwell we are talking about it, his essay on Dickens also has a political component. Dickens wrote a lot about the poor, obviously, and the plight of those with no power in society: women, children, the destitute. Because of this, socialists (of which Orwell was one) tried to “claim” him as one of their own. Orwell’s response is: “Not so fast …” The essay opens with an anecdote about Lenin seeing a production of Dickens’ The Cricket on the Hearth and walking out in disgust, finding the “middle-class sentimentality” intolerable. Lenin actually understood Dickens better than the socialists in Orwell’s day who wanted to turn him into some kind of class revolutionary. Orwell looks at the issue from all sides. It is a fascinating critical and political/social analysis. For example:

In Oliver Twist, Hard Times, Bleak House, Little Dorritt , Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked have swallowed him so completely that he has become a national institution himself.

Orwell breaks down how that occurred. He observes that Dickens did not write about the famous “proletariat”. He did not write about agricultural laborers or factory workers, the heroes of Socialist thinking. He wrote about bourgeois people: shopkeepers, bar owners, lawyers, innkeepers, servants: These are middle-class people, albeit with a grotesque edge. Dickens obviously had a social critique in his work, but unlike more proselytizing writers, he did not offer solutions, so much as present the problem. How is Oliver Twist saved? By one of those coincidental plot-points that operates so often in Dickens, where he is removed from the squalor of the streets into the glory of a wealthy neighborhood. This is written by a man who sees the issues but doesn’t really propose what we all should DO about them (besides notice that there are issues and sometimes the mere act of noticing is the most important step). Additionally, if you look closely at Dickens, as Orwell points out, “there is no clear sign that he wants the existing order overthrown, or that he believes it would make much difference if it were overthrown.” So why were socialists trying to claim him then?

If Dickens had a solution for the problems of the world, it would be something along the lines of: “Please be more kind and understanding towards one another.” This is not solely a political statement; it is more of a moral one, a Christian one. Dickens was a deeply moral writer. How David Copperfield is treated is abominable. But the system itself is not really called into question, at least not in any way that proposes a solution. Orwell criticizes Dickens for not proposing solutions, but he also sees him in a context that is revelatory. Orwell does not think a novelist has the same goal as a politician or social activist. It’s not Dickens’ job to say, “Here is what we should do about the poor.” But it is interesting that the most popular writer in English history (save Shakespeare) would be so easily claim-able by so many diverse groups as a propagandist for their cause. You can imagine the fun Dickens might have had with these groups, were he alive to know how his work was being utilized. Dickens pointed out the ills in English society, in the same way that William Blake did. And yet he did so in a way that somehow maintained the status quo at the same time. William Blake was far more of a revolutionary than Dickens was. “The whole system STINKS” was basically Blake’s point in his devastating poems about child chimney sweeps. Dickens has other concerns.

So to the socialists who think Dickens is one of them, Orwell says, “Come again? Have you read Tale of Two Cities ? You think he approves of revolution? What author have YOU been reading?”

Dickens is pretty contemptuous, overall, about the English education system. Schools suck, in Dickens’ world, which was probably an accurate reflection of what was going on (and something Orwell would clearly relate to, as we saw in his essay about his experience in an English boarding school ). Again, though, Dickens proposes no solution. He was not formally educated himself. Schoolmasters and teachers were ridiculous figures to him, pompous, cruel, unfair, and worthy of parody. It’s hard to find a good example of a teacher in Dickens’ work, which speaks volumes.

Orwell speaks of Dickens’ refreshing lack of nationalism, another reason why socialists wanted to claim him. Orwell makes the accurate observation that Dickens does not “exploit” the “other” in his works. His books clamor with people from all different walks of life, Irishmen, Scotsmen, Englishmen … and all emerge as human, albeit often ridiculous. But we’re all ridiculous, to some degree. He is not in service to the King, or to England. He is a humanist. He does not wave a flag. This may not be as easily seen today, or it may not be seen as very important, because questions of nationalism are not as paramount as they were in the 30s and 40s, when nations were behaving like a bunch of lunatics. I’m not saying we’re out of the woods yet. But the time in which Orwell was writing, as well as his socialist Marxist background, informs his analysis in a way that is quite interesting. Orwell finds Dickens’ lack of patriotism refreshing. (It’s also probably one of the reasons why Dickens’ books have traveled so far and lasted so long: they are not rooted in a time and place, they do not read as propaganda for a cause, as so much of the literature done by Dickens’ contemporaries does. Dickens’ books are about people , not politics.) I absolutely love this section:

The fact that Dickens is always thought of as a caricaturist, although he was constantly trying to be something else, is perhaps the surest mark of his genius. The monstrosities that he created are still remembered as monstrosities, in spite of getting mixed up in would-be probable melodramas. Their first impact is so vivid that nothing that comes afterwards effaces it. As with the people one knew in childhood, one seems always to remember them in one particular attitude, doing one particular thing. Mrs. Squeers is always ladling out brimstone and treacle, Mrs. Gummidge is always weeping, Mrs. Gargery is always banging her husband’s head against the wall, Mrs. Jellyby is always scribbling tracta while her children fall into the area — and there they all are, fixed for ever like little twinkling miniatures painted on snuffbox lids, completely fantastic and incredible, and yet somehow more solid and infinitely more memorable than the efforts of serious novelists. Even by the standards of his time Dickens was an exceptionally artificial writer. As Ruskin said, he “chose to work in a circle of stage fire”. His characters are even more distorted and simplified than Smolett’s. But there are no rules in novel-writing, and for any work of art there is only one test worth bothering about — survival. By this test Dickens’s characters have succeeded, even if the people who remember them hardly think of them as human beings. They are monsters, but at any rate they exist .

While the political critique is fascinating, Orwell also analyzes Dickens on a purely literary level, and it is such a joy to read. (He is always a joy to read.)

As I said, the essay is a multi-piece monster, and should be read in its entirety, but here is a wonderful excerpt.

What is more striking, in a seemingly ‘progressive’ radical, is that he is not mechanically minded. He shows no interest either in the details of machinery or in the things machinery can do. As Gissing remarks, Dickens nowhere describes a railway journey with anything like the enthusiasm he shows in describing journeys by stage-coach. In nearly all of his books one has a curious feeling that one is living in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and in fact, he does tend to return to this period. Little Dorrit , written in the middle fifties, deals with the late twenties; Great Expectations (1861) is not dated, but evidently deals with the twenties and thirties. Several of the inventions and discoveries which have made the modern world possible (the electric telegraph, the breech-loading gun, India-rubber, coal gas, wood-pulp paper) first appeared in Dickens’s lifetime, but he scarcely notes them in his books. Nothing is queerer than the vagueness with which he speaks of Doyce’s ‘invention’ in Little Dorrit . It is represented as something extremely ingenious and revolutionary, ‘of great importance to his country and his fellow-creatures’, and it is also an important minor link in the book; yet we are never told what the ‘invention’ is! On the other hand, Doyce’s physical appearance is hit off with the typical Dickens touch; he has a peculiar way of moving his thumb, a way characteristic of engineers. After that, Doyce is firmly anchored in one’s memory; but, as usual, Dickens has done it by fastening on something external.

There are people (Tennyson is an example) who lack the mechanical faculty but can see the social possibilities of machinery. Dickens has not this stamp of mind. He shows very little consciousness of the future. When he speaks of human progress it is usually in terms of moral progress — men growing better; probably he would never admit that men are only as good as their technical development allows them to be. At this point the gap between Dickens and his modern analogue, H.G. Wells, is at its widest. Wells wears the future round his neck like a mill-stone, but Dickens’s unscientific cast of mind is just as damaging in a different way. What it does is to make any positive attitude more difficult for him. He is hostile to the feudal, agricultural past and not in real touch with the industrial present. Well, then, all that remains is the future (meaning Science, ‘progress’, and so forth), which hardly enters into his thoughts. Therefore, while attacking everything in sight, he has no definable standard of comparison. As I have pointed out already, he attacks the current educational system with perfect justice, and yet, after all, he has no remedy to offer except kindlier schoolmasters. Why did he not indicate what a school might have been? Why did he not have his own sons educated according to some plan of his own, instead of sending them to public schools to be stuffed with Greek? Because he lacked that kind of imagination. He has an infallible moral sense, but very little intellectual curiosity. And here one comes upon something which really is an enormous deficiency in Dickens, something, that really does make the nineteenth century seem remote from us — that he has no idea of work .

With the doubtful exception of David Copperfield (merely Dickens himself), one cannot point to a single one of his central characters who is primarily interested in his job. His heroes work in order to make a living and to marry the heroine, not because they feel a passionate interest in one particular subject. Martin Chuzzlewit, for instance, is not burning with zeal to be an architect; he might just as well be a doctor or a barrister. In any case, in the typical Dickens novel, the Deus Ex Machina enters with a bag of gold in the last chapter and the hero is absolved from further struggle. The feeling ‘This is what I came into the world to do. Everything else is uninteresting. I will do this even if it means starvation’, which turns men of differing temperaments into scientists, inventors, artists, priests, explorers and revolutionaries — this motif is almost entirely absent from Dickens’s books. He himself, as is well known, worked like a slave and believed in his work as few novelists have ever done. But there seems to be no calling except novel-writing (and perhaps acting) towards which he can imagine this kind of devotion. And, after all, it is natural enough, considering his rather negative attitude towards society. In the last resort there is nothing he admires except common decency. Science is uninteresting and machinery is cruel and ugly (the heads of the elephants). Business is only for ruffians like Bounderby. As for politics — leave that to the Tite Barnacles. Really there is no objective except to marry the heroine, settle down, live solvently and be kind. And you can do that much better in private life.

Here, perhaps, one gets a glimpse of Dickens’s secret imaginative background. What did he think of as the most desirable way to live? When Martin Chuzzlewit had made it up with his uncle, when Nicholas Nickleby had married money, when John Harman had been enriched by Boffin what did they do ?

The answer evidently is that they did nothing. Nicholas Nickleby invested his wife’s money with the Cheerybles and ‘became a rich and prosperous merchant’, but as he immediately retired into Devonshire, we can assume that he did not work very hard. Mr. and Mrs. Snodgrass ‘purchased and cultivated a small farm, more for occupation than profit.’ That is the spirit in which most of Dickens’s books end — a sort of radiant idleness. Where he appears to disapprove of young men who do not work (Harthouse, Harry Gowan, Richard Carstone, Wrayburn before his reformation) it is because they are cynical and immoral or because they are a burden on somebody else; if you are ‘good’, and also self-supporting, there is no reason why you should not spend fifty years in simply drawing your dividends. Home life is always enough. And, after all, it was the general assumption of his age. The ‘genteel sufficiency’, the ‘competence’, the ‘gentleman of independent means’ (or ‘in easy circumstances’)— the very phrases tell one all about the strange, empty dream of the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century middle bourgeoisie. It was a dream of complete idleness . Charles Reade conveys its spirit perfectly in the ending of Hard Cash . Alfred Hardie, hero of Hard Cash , is the typical nineteenth-century novel-hero (public-school style), with gifts which Reade describes as amounting to ‘genius’. He is an old Etonian and a scholar of Oxford, he knows most of the Greek and Latin classics by heart, he can box with prizefighters and win the Diamond Sculls at Henley. He goes through incredible adventures in which, of course, he behaves with faultless heroism, and then, at the age of twenty-five, he inherits a fortune, marries his Julia Dodd and settles down in the suburbs of Liverpool, in the same house as his parents-in-law:

They all lived together at Albion Villa, thanks to Alfred . . . Oh, you happy little villa! You were as like Paradise as any mortal dwelling can be. A day came, however, when your walls could no longer hold all the happy inmates. Julia presented Alfred with a lovely boy; enter two nurses and the villa showed symptoms of bursting. Two months more, and Alfred and his wife overflowed into the next villa. It was but twenty yards off; and there was a double reason for the migration. As often happens after a long separation, Heaven bestowed on Captain and Mrs. Dodd another infant to play about their knees, etc. etc. etc.

This is the type of the Victorian happy ending — a vision of a huge, loving family of three or four generations, all crammed together in the same house and constantly multiplying, like a bed of oysters. What is striking about it is the utterly soft, sheltered, effortless life that it implies. It is not even a violent idleness, like Squire Western’s.

That is the significance of Dickens’s urban background and his noninterest in the blackguardly-sporting military side of life. His heroes, once they had come into money and ‘settled down’, would not only do no work; they would not even ride, hunt, shoot, fight duels, elope with actresses or lose money at the races. They would simply live at home in feather-bed respectability, and preferably next door to a blood-relation living exactly the same life:

The first act of Nicholas, when he became a rich and prosperous merchant, was to buy his father’s old house. As time crept on, and there came gradually about him a group of lovely children, it was altered and enlarged; but none of the old rooms were ever pulled down, no old tree was ever rooted up, nothing with which there was any association of bygone times was ever removed or changed.

Within a stone’s-throw was another retreat enlivened by children’s pleasant voices too; and here was Kate . . . the same true, gentle creature, the same fond sister, the same in the love of all about her, as in her girlish days.

It is the same incestuous atmosphere as in the passage quoted from Reade. And evidently this is Dickens’s ideal ending. It is perfectly attained in Nicholas Nickleby, Martin Chuzzlewit and Pickwick , and it is approximated to in varying degrees in almost all the others. The exceptions are Hard Times and Great Expectations — the latter actually has a ‘happy ending’, but it contradicts the general tendency of the book, and it was put in at the request of Bulwer Lytton.

The ideal to be striven after, then, appears to be something like this: a hundred thousand pounds, a quaint old house with plenty of ivy on it, a sweetly womanly wife, a horde of children, and no work. Everything is safe, soft, peaceful and, above all, domestic. In the moss-grown churchyard down the road are the graves of the loved ones who passed away before the happy ending happened. The servants are comic and feudal, the children prattle round your feet, the old friends sit at your fireside, talking of past days, there is the endless succession of enormous meals, the cold punch and sherry negus, the feather beds and warming-pans, the Christmas parties with charades and blind man’s buff; but nothing ever happens, except the yearly childbirth. The curious thing is that it is a genuinely happy picture, or so Dickens is able to make it appear. The thought of that kind of existence is satisfying to him. This alone would be enough to tell one that more than a hundred years have passed since Dickens’s first book was written. No modern man could combine such purposelessness with so much vitality.

3 Responses to The Books: A Collection of Essays , ‘Charles Dickens’, by George Orwell

I may have to stop reading you Sheila. Now I’m possessed by an overwhelming desire to pull down all my Dickens and all my Orwell…and I don’t have the freaking time! (lol)

Congrats on the Ebert plug btw. Needless to say, he demonstrates excellent taste.

I know – I don’t have the time either. I immediately want to start in on Pickwick Papers or something.

And thanks – yes, it was so exciting that he would link to me!

As a writer, I find Dickens endlessly fascinating. Not only did he manage to stay inside and outside a child’s mind; he managed to do the same with his own.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Search for:

Recent Posts

- Review: The Wasp (2024)

- “ Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.” — Mary Shelley

- “In the 20s, you were a face. And that was enough. In the 30s, you also had to be a voice. And your voice had to match your face, if you can imagine that.” — Joan Blondell

- “We were reflecting what we could perceive, which was paranoia everywhere and irrational fear. Certainly, my films of the 1970s reflected just that.” — William Friedkin

- #tbt Scene: Warehouse in Manhattan, West 20s, late 90s

- “I just sat at the drums and said, ‘Can I have a go?’ I just took to it.” — Honey Lantree

- “I do not ever want to be a huge star.” — Tuesday Weld

- “Was it a millionaire who said, ‘Imagine no possessions’?” — Elvis Costello

- “You can understand a lot about yourself by working out which fairytale you use to present your world to yourself in.” — A.S. Byatt

- “I like to sing to women with meat on their bones and that long green stuff in their pocketbook.” — Wynonie Harris

Recent Comments

- jeffry gagnon on The Books: “Rally Round the Flag, Boys!” (Max Shulman)

- sheila on “Was it a millionaire who said, ‘Imagine no possessions’?” — Elvis Costello

- Roger T Shrubber on “Was it a millionaire who said, ‘Imagine no possessions’?” — Elvis Costello

- sheila on “The thing I really wanna say is—and really, really mean is that real things last. Any way you look at it. Real things last.” — Dale Hawkins

- mutecypher on “Was it a millionaire who said, ‘Imagine no possessions’?” — Elvis Costello

- Bill Wolfe on “The thing I really wanna say is—and really, really mean is that real things last. Any way you look at it. Real things last.” — Dale Hawkins

- Leigh Harwood on “I love humanity but I hate people.” — poet Edna St. Vincent Millay

- sheila on “A ‘smartcracker’ they called me, and that makes me sick and unhappy.” — Dorothy Parker

- Mike Molloy on “A ‘smartcracker’ they called me, and that makes me sick and unhappy.” — Dorothy Parker

George Orwell on Charles Dickens and Revolutions

George Orwell was initially tempted to dismiss Charles Dickens because he seemed to have “no political program” to offer. But soon Orwell recognized this presumed defect to be a virtue and decided that Dickens was a moralist, not a revolutionary.

Today both left and right try to claim Orwell, who died in 1950, a confirmed opponent of Stalin and Stalinism. However, there is no doubt that he regarded himself as a man of the left. During World War II he called himself a “left-wing patriot.” And during the early stages of the Cold War he was by his own definition both a “democratic socialist” and an anti-communist.

Many on the left today could turn to Dickens or Orwell and find much with which to agree—especially when it comes to assessing what has or has not gone wrong in modern Western society… and why. But what to do in response? Ah, that is the question.

Many on the left like to compare the recent violence in our cities to violence on the road to 1776. The Stamp Act riots usually stand as Exhibit A. Violence then and violence now: It’s all the same, because it’s all directed at the same goal. Or is it?

Last summer an Antifa leader in Portland was quoted as saying that this is our moment to “fix everything.” Dickens and Orwell would have shuddered upon reading such a line.

During World War II Orwell wrote a lengthy and largely celebratory essay on Dickens. The heart of it concerned Dickens’ thoughts on social change. The original American revolution of 1776 (and the “fix everything” French revolution of 1789) might well have been hovering in the background, but neither was ever mentioned.

The ever-angry Dickens saw two possible paths for a society “beset by social inequalities,” as Orwell put it. One was that of the revolutionary. The other was that of the moralist.

Orwell was initially tempted to dismiss Dickens, because he seemed to have “no political program” to offer. But before he was finished, that presumed “defect” turned out to be a “virtue.” Dickens, Orwell decided, was a moralist, and not a revolutionary.

As such, Charles Dickens was convinced that the world will change only when people first have a “change of heart.” In the end the questions are these: Do you work on changing the system by attempting to do the impossible; i.e., change human nature? Or do you recognize that only when people have a change of heart will society improve?

It was rightly clear to Orwell that Dickens was forever holding out for the latter. Why? Because he decided that Dickens intuitively understood something that would become all too obvious in the 20 th century; namely, that the revolutionary fix-everything approach “always results in a new abuse of power.”

As Orwell the anti-communist knew full well, there is “always a new tyrant waiting to take over from the old tyrant.” In fact, the new tyrant is likely to be even more tyrannical than the predecessor. Tsar Nicholas II, meet Lenin. Such a result is especially inevitable if the original motivation of the tyrant-in-training is to overhaul the entire society.

Strictly speaking, the American rebels of 1776 were neither hardcore revolutionaries nor Dickensian moralists. If anything, they were conservative rebels and hopeful moralists. Their immediate goal was to fix something, but far from everything. Their long term hope was to create a country filled with those who had had or could have a change of heart.

By cutting ties with England, the American rebels had addressed the most immediate problem that needed fixing. That act alone preserved liberties that they had but feared they were losing; hence the conservative nature of this “revolution.” The small step they took to “fix something” proved to be a giant step for all for generations to come.

Clearly, theirs was not simply a moral revolution, but many of the leading rebels were quite aware that their new republic could only be maintained by a moral people. John Adams was chief among them. Post-1776 America could only succeed if it was a nation of laws. Morality had to undergird those laws. And religion, in turn, had to undergird morality.

If there was no call to “fix everything,” there was also no call for everyone to have an immediate change of heart. Most importantly, there was no impetus to trade one tyrant for another. But the stage was set to build a country where ongoing changes of heart could, and in many case would, bring about the decent society that Adams, as well as Dickens and Orwell, hoped to see.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now .

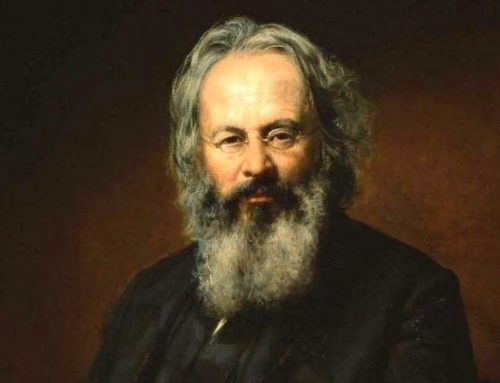

The featured image combines an image of George Orwell and an image of Charles Dickens , both of which are in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

All comments are moderated and must be civil, concise, and constructive to the conversation. Comments that are critical of an essay may be approved, but comments containing ad hominem criticism of the author will not be published. Also, comments containing web links or block quotations are unlikely to be approved. Keep in mind that essays represent the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Imaginative Conservative or its editor or publisher.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: chuck chalberg.

Related Posts

Tocqueville and a New Science of Politics

Remembering Donald S. Lutz, Pirate Scholar

Making America Great Again: Orestes Brownson on National Greatness

How to Read the Declaration of Independence

Therein lies the rub. How can you change a heart when the Bible tells us that the heart is “desperately wicked”. We are seeing, right now, in South Africa and before in the US, what happens when those desperately wicked hearts have no superior force to fear. The result is total anarchy. In SA even some police have joined in the looting.

Matt 21 spells out the coming storm, let no man be deceived. The only rescue is faith in Christ,

Fair enough, not to mention darn right. Orwell was not a believer, but he was quite worried that the loss of the faith in the west was likely to doom the west.

Having written a good deal about both George Orwell and Charles Dickens, I was delighted to see this fresh perspective by M. Chalberg. My congratulations, Sincerely John Rodden

Though Chalberg didn’t draw the parallel, unless tacitly understood, between Burke the moralist and Paine the revolutionary, between old testament christianity (status quo) and new testament christianity (revolution), that was Dickens’ dilemma; he favoured the latter.

Leave A Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Charles Dickens, the review of George Orwell. First published: March 11, 1940 by/in Inside the Whale and Other Essays, GB, London. ... John Chivery is another, and there is a rather ill-natured treatment of this theme in the 'swarry' in Pickwick Papers. Here Dickens describes the Bath footmen as living a kind of fantasy-life, holding dinner ...

Essay. I. Dickens is one of those writers who are well worth stealing. Even the. burial of his body in Westminster Abbey was a species of theft, if you. come to think of it. When Chesterton wrote his introductions to the Everyman Edition of. Dickens's works, it seemed quite natural to him to credit Dickens with.

While the political critique is fascinating, Orwell also analyzes Dickens on a purely literary level, and it is such a joy to read. (He is always a joy to read.) As I said, the essay is a multi-piece monster, and should be read in its entirety, but here is a wonderful excerpt. A Collection of Essays, 'Charles Dickens', by George Orwell

Both were angry, very, very angry—and legitimately so. These well-known Englishmen were Charles Dickens and George Orwell. The anger of each was not unrelated to the anger of some of the American left today. Dickens was angered by the impact of the industrial revolution on his country and on himself. Orwell was angry at the entire capitalist ...

1812-1817 — Infancy in Portsmouth and London. Born on 7th February 1812 at a house in Mile End Terrace, Portsmouth, Hampshire. His father, John Dickens, worked as a clerk in the pay office of the Royal Dockyard. Family moved to London in 1814 when John was posted there. 1817-1822 — Happy boyhood in Kent.

Inside the Whale was published by Victor Gollancz as a book of essays on 11 March 1940. Orwell refers to it as a "book" in part three of the essay. ... "Charles Dickens" (1940) "Boys' Weeklies" (1940) ... The back cover of the 1962 edition notes that the front cover is a photograph of a selection of books from George Orwell's personal library ...

Read George Orwell's Charles Dickens free online! Click on any of the links on the right menubar to browse through Charles Dickens. The complete works of george orwell, searchable format. Also contains a biography and quotes by George Orwell.

Note: Most of these essays have appeared in print before, and several of them more than once. "Charles Dickens" and "Boys' Weeklies" appeared in my book, Inside the Whale."Boys' Weeklies" also appeared in Horizon, as did "Wells, Hitler and the World State", "The Art of Donald McGill", "Rudyard Kipling", "W. B. Yeats" and "Raffles and Miss Blandish".

Oddly enough, Orwell might have endorsed these critiques, in much the same way as he complains that Charles Dickens's moral criticism amounts to "an enormous platitude: If men would behave ...

George Orwell's Essays illuminate the life and work of one of the greatest writers of this century - a man who elevated political writing to an art ... With great originality and wit Orwell unfolds his views on subjects ranging from a revaluation of Charles Dickens to the nature of Socialism, from a comic yet profound discussion of naughty ...

Critical Essays. (Orwell) First edition (publ. Secker & Warburg) Critical Essays (1946) is a collection of wartime pieces by George Orwell. It covers a variety of topics in English literature, and also includes some pioneering studies of popular culture. It was acclaimed by critics, and Orwell himself thought it one of his most important books.

Orwell on Dickens. Coming to the Orwell board for the first time I was pleasantly surprised to see that there is a whole section dedicated to his Dickens essay. Orwell's essay on Dickens is probably the best explanation of Dickens that I've ever read, and shows that Orwell's insight was not limited to political and social matters but extended ...

Both of them are in public domain. A s well as being a tour guide, David is a local politician in Islington, the area of London where he lives, and where both George Orwell and Charles Dickens lived. He was Mayor of Islington 2018-2019. Prior to local politics, he worked in international politics working for the European Union in Brussels after ...

I've just discovered Orwell's superb 1939 essay on Dickens, and can't believe I've never read it before. The last section is reproduced below & gives a flavour of what to expect. ... - "Charles Dickens" by George Orwell, 1939. Tweet. Author Chris Cleave Posted on September 29, 2010 January 28, 2015 Categories What I'm reading. One thought ...

A Collection of essays by George Orwell. Welcome to the second essay from George Orwell's collection tackling the body of work of Charles Dickens! He not only critiques Dickens, but he critiques critics critiquing Dickens. This is one of his longest and most well-regarded literary critiques, published in 1940 and interestingly, Dickens was one ...

A brilliant essayist with a magnificent command of the English language, Orwell in this first collection dealt with Charles Dickens, the English "boys' weeklies", and Henry Miller. He used his subjects to dwell on a wide variety of issues including "cultural unity", propaganda, and literary trends.

A collection of essays by Orwell, George, 1903-1950. Publication date 1954 Topics English essays Publisher Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday ... English Item Size 489.6M . Such, such were the joys... -- Charles Dickens -- The art of Donald McGill -- Rudyard Kipling -- Raffles and Miss Blandish -- Shooting an elephant -- Politics and the English ...

As a critic, George Orwell cast a wide net. Equally at home in discussing Charles Dickens and Charlie Chaplin, he moved back and forth across the porous borders between essay and journalism, high art and low. A frequent commentator on literature, language, film and drama throughout his career, Orwell turned increasingly to the critical essay in the 1940s, when his most important experiences ...

A collection of essays by Orwell, George, 1903-1950. Publication date 1953 Topics Orwell, George, 1903-1950, English authors Publisher San Diego : Harcourt Brace Jovanovich ... such were the joys ..." -- Charles Dickens -- The art of Donald McGill -- Rudyard Kipling -- Raffles and Miss Blandish -- Shooting an elephant -- Politics and the ...

While George Orwell (1903-1950) was at times a critic of Dickens, in his 1939 essay Charles Dickens he, like many others before, again brought to light the author still relevant today and worthy of continued study: Nearly everyone, whatever his actual conduct may be, responds emotionally to the idea of human brotherhood. Dickens voiced a code ...

Collected essays by Orwell, George, 1903-1950. Publication date 1961 Publisher London : Secker & Warburg Collection trent_university; internetarchivebooks; inlibrary; printdisabled Contributor Internet Archive Language English Item Size 1111793953. 434 p Notes. Some pages are have pen writting.