The Greek poet Homer is credited with being the first to write down the epic stories of 'The Iliad' and 'The Odyssey,' and the impact of his tales continues to reverberate through Western culture.

Who Was Homer?

The Greek poet Homer was born sometime between the 12th and 8th centuries BC, possibly somewhere on the coast of Asia Minor. He is famous for the epic poems The Iliad and The Odyssey , which have had an enormous effect on Western culture, but very little is known about their alleged author.

The Mystery of Homer

Homer is a mystery. The Greek epic poet credited with the enduring epic tales of The Iliad and The Odyssey is an enigma insofar as actual facts of his life go. Some scholars believe him to be one man; others think these iconic stories were created by a group. A variation on the group idea stems from the fact that storytelling was an oral tradition and Homer compiled the stories, then recited them to memory.

Homer’s style, whoever he was, falls more in the category of minstrel poet or balladeer, as opposed to a cultivated poet who is the product of a fervent literary moment, such as a Virgil or a Shakespeare. The stories have repetitive elements, almost like a chorus or refrain, which suggests a musical element. However, Homer’s works are designated as epic rather than lyric poetry, which was originally recited with a lyre in hand, much in the same vein as spoken-word performances.

All this speculation about who he was has inevitably led to what is known as the Homeric Question—whether he actually existed at all. This is often considered to be the greatest literary mystery.

When Was Homer Born?

Much speculation surrounds when Homer was born because of the dearth of real information about him. Guesses at his birth date range from 750 BC all the way back to 1200 BC, the latter because The Iliad encompasses the story of the Trojan War, so some scholars have thought it fit to put the poet and chronicler nearer to the time of that actual event. But others believe the poetic style of his work indicates a much later period. Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 BC), often called the father of history, placed Homer several centuries before himself, around 850 BC.

Part of the problem is that Homer lived before a chronological dating system was in place. The Olympic Games of classical Greece marked an epoch, with 776 BC as a starting point by which to measure out four-year periods for the event. In short, it is difficult to give someone a birth date when he was born before there was a calendar.

Where Was Homer Born?

Once again, the exact location of Homer’s birth cannot be pinpointed, although that doesn't stop scholars from trying. It has been identified as Ionia, Smyrna or, at any rate, on the coast of Asia Minor or the island of Chios. But seven cities lay claim to Homer as their native son.

There is some basis for some of these claims, however. The dialect that The Iliad and The Odyssey are written in is considered Asiatic Greek, specifically Ionic. That fact, paired with frequent mentions of local phenomena such as strong winds blowing from the northwest from the direction of Thrace, suggests, scholars feel, a familiarity with that region that could only mean Homer came from there.

The dialect helps narrow down his lifespan by coinciding it with the development and usage of language in general, but The Iliad and The Odyssey were so popular that this particular dialect became the norm for much of Greek literature going forward.

What Was Homer Like?

Virtually every biographical aspect ascribed to Homer is derived entirely from his poems. Homer is thought to have been blind, based solely on a character in The Odyssey , a blind poet/minstrel called Demodokos. A long disquisition on how Demodokos was welcomed into a gathering and regaled the audience with music and epic tales of conflict and heroes to much praise has been interpreted as Homer’s hint as to what his own life was like. As a result, many busts and statues have been carved of Homer with thick curly hair and beard and sightless eyes.

“Homer and Sophocles saw clearly, felt keenly, and refrained from much,” wrote Lane Cooper in The Greek Genius and Its Influence: Select Essays and Extracts in 1917, ascribing an emotional life to the writer. But he wasn't the first, nor was he the last. Countless attempts to recreate the life and personality of the author from the content of his epic poems have occupied writers for centuries.

'The Iliad' and 'The Odyssey'

The Odyssey picks up after the fall of Troy. Further controversy about authorship springs from the differing styles of the two long narrative poems, indicating they were composed a century apart, while other historians claim only decades –the more formal structure of The Iliad is attributed to a poet at the height of his powers, whereas the more colloquial, novelistic approach in The Odyssey is attributed to an elderly Homer.

Homer enriched his descriptive story with the liberal use of simile and metaphor, which has inspired a long path of writers behind him. His structuring device was to start in the middle– in medias res – and then fill in the missing information via remembrances.

The two narrative poems pop up throughout modern literature: Homer’s The Odyssey has parallels in James Joyce’s Ulysses , and his tale of Achilles in The Iliad is echoed in J.R.R. Tolkien 's The Fall of Gondolin . Even the Coen Brothers’ film O Brother, Where Art Thou? makes use of The Odyssey .

Other works have been attributed to Homer over the centuries, most notably the Homeric Hymns , but in the end, only the two epic works remain enduringly his.

"Plato tells us that in his time many believed that Homer was the educator of all Greece. Since then, Homer’s influence has spread far beyond the frontiers of Hellas [Greece]….” wrote Werner Jaeger in Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture . He was right. The Iliad and The Odyssey have provided not only seeds but fertilizer for almost all the other arts and sciences in Western culture. For the Greeks, Homer was a godfather of their national culture, chronicling its mythology and collective memory in rich rhythmic tales that have permeated the collective imagination.

Homer’s real life may remain a mystery, but the very real impact of his works continues to illuminate our world today.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Homer

- Birth Year: 800

- Birth Country: Greece

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: The Greek poet Homer is credited with being the first to write down the epic stories of 'The Iliad' and 'The Odyssey,' and the impact of his tales continues to reverberate through Western culture.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Nationalities

- Death Year: 701

- Death Country: Greece

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- Hateful to me as the gates of Hades is that man who hides one thing in his heart and speaks another.

- Yet, taught by time, my heart has learned to glow for other's good, and melt at other's woe.

- Light is the task where many share the toil.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Amanda Gorman

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

Maya Angelou

The Life and Work of Homer

Print Collector / Getty Images

- Figures & Events

- Ancient Languages

- Mythology & Religion

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Linguistics, University of Minnesota

- B.A., Latin, University of Minnesota

Homer was the most important and earliest of the Greek and Roman writers. Greeks and Romans didn't count themselves educated unless they knew his poems. His influence was felt not only on literature but on ethics and morality via lessons from his masterpieces. He is the first source to look for information on Greek myth and religion. Yet, despite his prominence, we have no firm evidence that he ever lived.

" Homer and Hesiod have ascribed to the gods all things that are a shame and a disgrace among mortals, stealing and adulteries and deceiving on one another. " —Xenophanes (a Pre-Socratic philosopher)

The Life of the Blind Bard

Because Homer performed and sang he is called a bard. He is thought to have been blind, and so is known as the blind bard, just as Shakespeare, calling on the same tradition, is known as the bard of Avon.

The name "Homer," which is an unusual one for the time, is thought to mean either "blind" or "captive". If "blind," it may have to do more with the portrayal of the Odyssean blind bard called Phemios than the poem's composer.

Homer's Birthplaces and Date

There are multiple cities in the ancient Greek world that lay the prestigious claim of being the birthplace of Homer. Smyrna is one of the most popular, but Chios, Cyme, Ios, Argos, and Athens are all in the running. The Aeolian cities of Asia Minor are most popular; outliers include Ithaca and Salamis.

Plutarch provides a choice of Salamis, Cyme, Ios, Colophon, Thessaly, Smyrna, Thebes , Chios, Argos, and Athens, according to a table showing ancient authors who provided biographical information on Homer, in "Lives of Homer (Continued)," by T. W. Allen; The Journal of Hellenic Studies , Vol. 33, (1913), pp. 19-26. Homer's death is less controversial, Ios being the overwhelming favorite.

Since it's not even clear that Homer lived, and since we don't have a fix on the location, it should come as no surprise that we don't know when he was born. He is generally considered to have come before Hesiod. Some thought him a contemporary of Midas (Certamen).

Homer is said to have had two daughters (generally, the symbolic ones of the Iliad and the Odyssey ), and no sons, according to West [citation below], so the Homeridai, who are referred to as Homer's followers and rhapsodes themselves, can't really claim to be descendants, although the idea has been entertained.

The Trojan War

Homer's name will always be linked with the Trojan War because Homer wrote about the conflict between Greeks and Trojans, known as the Trojan War, and the return voyages of the Greek leaders. He is credited with telling the whole story of the Trojan War, but that is false. There were plenty of other writers of what is called the "epic cycle" who contributed details not found in Homer.

Homer and the Epic

Homer is the first and greatest writer of the Greek literary form known as epic and so it's in his work that people look for information about the poetic form. Epic was more than a monumental story, although it was that. Since bards sang stories from memory, they needed and used many helpfully mnemonic, rhythmic, poetic techniques that we find in Homer. Epic poetry was composed using a rigorous format.

Major Works Credited to Homer - Some in Error

Even if the name isn't his, a figure we think of as Homer is considered by many to be the writer of the Iliad , and possibly the Odyssey , although there are stylistic reasons, like inconsistencies, to debate whether one person wrote both. An inconsistency that resonates for me is that Odysseus uses a spear in The Iliad , but is an extraordinary archer in the Odyssey . He even describes his bow prowess demonstrated at Troy [source: "Notes on the Trojan War ," by Thomas D. Seymour, TAPhA 1900, p. 88.].

Homer is sometimes credited, although less credibly, with the Homeric Hymns . Currently, scholars think these must have been written more recently than the Early Archaic period (aka the Greek Renaissance), which is the era in which the greatest Greek epic poet is thought to have lived.

- Homeric Hymns

Homer's Major Characters

In Homer's Iliad , the lead character is the quintessential Greek hero, Achilles. The epic states that it is the story of the wrath of Achilles. Other important characters of the Iliad are the leaders of the Greek and Trojan sides in the Trojan War, and the highly partisan, human-seeming gods and goddesses—the deathless ones.

In The Odyssey , the lead character is the title character, the wily Odysseus. Other major characters include the family of the hero and the goddess Athena.

Perspective

Although Homer is thought to have lived in the early Archaic Age, the subject matter of his epics is the earlier, Bronze Age , Mycenaean era. Between then and when Homer may have lived there was a "dark age." Therefore Homer is writing about a period about which there is not a substantial written record. His epics give us a glimpse of this earlier life and social hierarchy, although it is important to realize that Homer is a product of his own times, when the polis (city-state) was beginning, as well as the mouthpiece for stories handed down the generations, and so details may not be true to the era of the Trojan War.

The Voice of the World

In his poem, "The Voice of the World," the 2nd-century Greek poet Antipater of Sidon, best known for writing about the Seven Wonders (of the ancient world), praises Homer to the skies, as can be seen in this public domain translation from the Greek Anthology:

" The herald of the prowess of heroes and the interpreter of the immortals, a second sun on the life of Greece, Homer, the light of the Muses, the ageless mouth of all the world, lies hid, O stranger, under the sea-washed sand. "

- "'Reading' Homer through Oral Tradition," by John Miles Foley; College Literature , Vol. 34, No. 2, Reading Homer in the 21st Century (Spring, 2007).

- The Invention of Homer, by M. L. West; The Classical Quarterly , New Series, Vol. 49, No. 2 (1999), pp. 364-382.

- Greek Gods, Myths, and Legends

- List of Characters in 'The Iliad'

- 'The Odyssey' Overview

- Who Is Who in Greek Legend

- Ancient/Classical History Study Guides

- Biography of Helen of Troy, Cause of the Trojan War

- Table of Roman Equivalents of Greek Gods

- Answers to FAQs About the Trojan War

- Understanding the Achaeans That Are Mentioned in Homer's Epics

- Ulysses (Odysseus)

- Most Important Figures in Ancient History

- The Major Events in the Trojan War

- Overview of the Archaic Age of Ancient Greek History

- The Genre of Epic Literature and Poetry

- Who Was Andromache?

Enable JavaScript and refresh the page to view the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

See how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Bibliography

Editorial and production teams, the mast project, picturing homer as a cult hero.

2024.05.28, rewritten from Classical Inquiries 2016.03.03 | By Gregory Nagy

This pre-edited standalone essay, rewritten for online publication in Classical Continuum , originally appeared in Classical Inquiries 2016.03.03. My rewritten version here supersedes the original version, partly because my online contributions to Classical Inquiries , extending from 2015.02.14 to 2021.10.13, are currently not being curated by the Center for Hellenic Studies.

Introduction

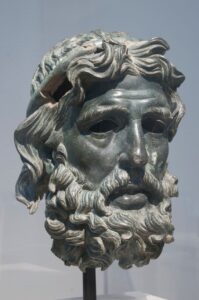

§0.1. This essay centers on a bronze statue of a head, dated somewhere between 227 and 221 BCE. The bronze head was on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in the context of a grand exhibition at the National Gallery, titled “Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World” and extending from December 13, 2015, to March 20, 2016. Together with Gloria Ferrari Pinney and Faya Causey, I was involved as a co-organizer of two public events focusing on two aspects of the exhibition. These events were panel discussions of two topics:

February 18, 2016: “A priestess or a goddess: The problem of identity in some female Hellenistic sculptures.”

February 25, 2016: “A poet or a god: The iconography of certain bearded male bronzes.”

About these two events I refer to overall reports, originally published in Classical Inquiries , by Keith DeStone, and now rewritten by him here:

https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/harvards-center-for-hellenic-studies-and-the-national-gallery-of-art-collaborate-to-shine-light-on-ancient-greek-bronzes-part-1-ed1/

https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/harvards-center-for-hellenic-studies-and-the-national-gallery-of-art-collaborate-to-shine-light-on-ancient-greek-bronzes-part-2-ed2/

At the second of the two events cited here, my friend Gloria Ferrari Pinney—hereafter I refer to her, in honor of our friendship, simply as Gloria—argued that the bronze head on loan from Houston is a representation of Homer. At the same event, I too offered supporting arguments, which were first published in my original essay of 2016.03.03 in Classical Inquires . As I now rewrite my essay, I must start by noting, with deep regret, the untimely death of Gloria in 2023.09.18, which now leaves me with the sad task of trying to sustain the essence of her argumentation without the benefit of any further consultation with her. I fear I can do no better than restate, as faithfully as possible, my memories of what Gloria had said about the bronze head in 2016.02.25. Taking my lead from what she did say, I will argue here that this bronze Homer—if indeed he is Homer, as I think he must be—is in this case imagined not only as the greatest of all poets but also as a cult hero.

§0.2. An essential aspect of GFP’s argument is the fact that the Houston bronze head resembles closely the head of the god Zeus himself as represented in statues and coins. In terms of this argument, Homer is figured as the greatest poet of the ancient Greeks just as Zeus is figured as their greatest god.

§0.3. There is further evidence, as Gloria shows, for the artistic construct of such a resemblance between Homer and Zeus. A most telling example is a marble monument known as the Arkhelaos Relief, conventionally dated to the second century BCE. The lower zone of the relief sculpture shows an enthroned Homer receiving sacrificial offerings while the upper zone shows Zeus himself, holding a scepter. Similarly, Homer holds a scepter, which is in his left hand. Also, he holds a scroll in his right hand. There is no mistake about the identification of Homer here, since the Arkhelaos Relief features adjacent lettering that reads ΟΜΗΡΟΣ ( Homēros ). We see comparable representations of an enthroned Homer as pictured on two coins, one from the city-state of Smyrna, reputed to be the place where he was born, and another from the island-state of Ios, where he was supposedly conceived—and where he died.

Smyrna, 190-130 BCE. Pictured is the poet Homer, seated and holding a staff and a scroll. ΣΜΥΡΝΑΙΩΝ = ‘of the people of Smyrna’. Named is a magistrate, AXIΛΛHTOΣ [A]XIΛΛHTO[Υ] = ‘Akhilletos, son of Akhilletos’. Pictured on the other side of the coin is the laureate head of Apollo. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

Ios, 4th century BCE. British Museum number 1951,1007.8. Obverse: pictured is the bearded head of Homer, bound with a fillet; inscription OMHPOY = ‘of Homer’. Reverse: g arland; inscription IHTΩN = ‘of the people of Ios’.

Picturing Homer as blind or as sighted

§1. As Gloria Pinney argues, the artistic construct of such a resemblance between Homer and Zeus comes with a requirement: Homer must be pictured as sighted, not blind. If Homer is to be compared to Zeus, he cannot be deformed by blindness, since the greatest of all gods must surely be exempt from such deformity.

§2. But there are well-known examples of an alternative artistic construct that features Homer as blind, and this construct is amply attested in the visual arts. Further, such an artistic construct of a blind Homer matches what we read in the stories produced by the verbal arts of mythmaking about Homer’s life. In those stories as I analyzed them in an essay dated 2016.02.25 and, in an earlier essay dated 2016.02.18 , Homer in various different ways becomes a blind man in the course of his life. So, the question arises: what is the difference between a blind Homer and a sighted Homer?

§3. If we follow the logic of the artistic construct that we see at work in the Arkhelaos Relief, the enthroned Homer as pictured in that relief must surely be situated in a state of existence that follows his death. In other words, Homer now exists in an afterlife. That is why the Arkhelaos Relief has been thought to represent what is called the “apotheosis” of Homer: it is as if the greatest of poets had now become a theos or ‘god’, just as Zeus is a god. [1] And, in this transcendent state, Homer regains his vision. Here is a close-up of this transcendent Homer as represented in the Arkhelaos relief:

§4. I argue, however, that Homer in such a state of afterlife is not so much a god as he is a cult hero who looks like a god. Here I find it most useful to consult a book by W. H. D. Rouse on the iconography of votive offerings. [2] He collects images of cult heroes in the afterlife who are pictured as enthroned or reclining or engaged in other such poses. [3] In each case, as Rouse shows, the pose is matched by gods who are similarly engaged: in one particular case, Rouse describes the picturing of a reclining hero “with face approaching that of Zeus or Hades.” [4]

§5. Just as the enthroned Homer in the Arkhelaos relief receives sacrificial offerings from his worshippers, so also the enthroned cult heroes in the collection put together by Rouse are seen in the act of receiving offerings from their worshippers. Here is an example:

Bibliography Clay, D. 2004. Archilochos Heros: The Cult of Poets in the Greek Polis . Hellenic Studies 6. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. H24H . See Nagy 2013. Nagy, G. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours . Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013 . Rouse, W. H. D. 1902. Greek Votive Offerings: An Essay in the History of Greek Religion . Cambridge.

Notes [1] For a brief history of this terminology, which also inspired the painting “L’Apothéose d’Homère” by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1827), see Clay 2004:1. [2] Rouse 1902. [3] Rouse 1902:20, 34 (heroes enthroned); 22 (heroes reclining). [4] Rouse 1902:22.

Continue Reading

Archilochus, poet and cult hero.

The practice of worshipping the poet Archilochus as a cult hero was the context for narrating myths about him by…

Picturing Archilochus as a cult hero

This essay picks up from where I left off in an essay titled “Picturing Homer as a cult hero.” I…

On this coin, minted in the city-state of Smyrna, we see Homer seated on a throne, in the pose of…

Enable JavaScript and refresh the page to view the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

See how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Bibliographies

The ci poetry project, a question of “reception”: how could homer ever outlive his own moments of performance.

By Gregory Nagy

§0. In the cover illustration for this essay, a painter is picturing Homer at a moment of performance. Or, I could even say that we see Homer here in—not just at—a moment of performance. Homer sings, accompanying himself on his lyre. Viewing him and listening to him most attentively, in the imagination of our painter, are poets from Homer’s future “reception.” Most visible is old Dante himself, and, further away, we can spot a middle-aged Shakespeare, and, off to the side, a youngish Goethe is looking on. But these three canonical poets, representing the “reception” of Homer in future times far removed from the Homeric past, are not reading Homer here. No, they are pictured as actually hearing and even seeing that poet in a very special moment: they are witnessing Homer in the very act of his creating his own poetry. And that is actually how the ancient Greeks, in earlier periods of their prehistory and history, imagined Homer’s very own moments of poetic creation. In such earlier periods, Homer’s poetry-in-the-making was not a written text that was meant to be read. No, his poetry was an oral performance that was meant to be heard—and seen as well. In other words, the very idea of Homer in earlier periods of the ancient Greek world was linked to Homer’s oral performance, which was imagined as a composition-in-performance. But how could such a Homeric performance, as imagined in the ancient Greek world, outlive the life and times of a prototypical Homer? Or, to ask the question in a more fanciful way, how could Homer ever outlive his own moments of performance?

§1. Before I attempt to answer such a question, I must emphasize that the “reception” of Homer, grounded in the realities of ancient Greek history, was different from what is usually also called the “reception” of Homer in later times, when the poetry of Homer was no longer heard in oral performance. Contradicting the fantasy pictured by our painter, where canonical poets who lived in far later times could still get a chance to hear and to see an exquisite moment of composition-in-performance by Homer himself, the grim reality of Homeric “reception” in the poetic worlds of a Dante or a Shakespeare or a Goethe was a simple historical fact: the oral tradition of Homeric poetry was dead, and had been dead for a long time. In fact, Homeric oral poetry was already dying in the later periods of ancient Greek history. And, for the longest time by now, Homeric poetry has survived only as a written text to be read by its readers—sometimes in the original or, in most cases, in translations or in paraphrases. And here I return to my fanciful question: how, then, could Homer ever outlive his moments of in-person performance?

§2. Such a question, as I just posed it, can best be answered, I suggest, if we rethink the term “reception,” which I have so far been treating with indifference, isolating it within quotation-marks. As I have already suggested, however, a distinction needs to be made. For me, there are two different kinds of reception, and I will focus on the earlier kind. The later kind is all too familiar, corresponding to the use of the term reception in conventional literary criticism today, where it refers to the responses of readers to the written text of a given literary production. But here I introduce a different and defamiliarizing use of the term, focusing on an earlier kind of reception , referring to a “literary” production that is oral . In any given oral tradition of verbal art, the reception of this tradition by its audience—or, to say it better, by the society in which the oral tradition was generated—is not just incidental. It is essential. The reception of a textual tradition, if it gets neglected over time or even if it dies altogether, can still be brought back to life—however imperfectly—if any texts have survived. By contrast, death for the reception of an oral tradition signals death for such a tradition. An oral tradition cannot survive without reception. Even if some transcript of oral traditional performance survives, such a text cannot, of and by itself, bring back to life the structural realities of the oral tradition, and any new reception of such a text could now become simply a textual reception, even if the text imitates an oral performance or, better, serves as a script for such a would-be oral performance.

§3. With this distinction between oral and textual reception in place, I am ready to restate more clearly, I hope, an obvious historical fact: the oral reception of Homeric poetry is dead, and it died a very long time ago. But how long ago? It is difficult to give a precise answer, since only the textual reception survives, and it is only by studying the history of that reception that we have any hope of reconstructing, at least in broad outlines, the history of an earlier oral reception.

§4. In two twin books I have produced on the subject of Homeric poetry, Homer the Classic (2009|2008) and Homer the Preclassic (2010|2009), I have attempted to reconstruct the overall reception of this poetry, going backward in time, and thus showing that the relatively later phases of Homeric reception became merely textual, while the earlier phases were still oral.

§5. In two earlier twin books on the same subject of Homeric poetry, Poetry as Performance: Homer and Beyond (1996a) and Homeric Questions (1996b), I had attempted a different kind of reconstruction, going forward as well as backward in time. This kind of two-way reconstructing was an exercise in describing the periodizations of Homeric poetry by way of applying modes of diachronic as well as synchronic analysis. When I say “synchronic” and “diachronic” here, I am following the terminology of Ferdinand de Saussure (1916:117), and I draw special attention to the fact that, for Saussure, “diachronic” was synonymous with “evolutionary.” Accordingly, in my two earlier twin-books, I referred to my reconstruction of Homeric periodizations as an “evolutionary model” for explaining the textual destiny of Homeric poetry.

§6. As I look back on my “evolutionary model” as outlined in Poetry as Performance (1996:110) and in Homeric Questions (1996b:42), I now see that some clarification is needed with regard to my thinking about what I call “period 3,” a time-frame that extends, by my reckoning, from the middle of the sixth century BCE to the later part of the fourth. In my overall reconstruction, covering five “periods” in the evolution of Homeric poetry, I view this “period 3” as transitional—to the extent that my model allows for the possibility that scribes within this time-frame could and perhaps did make copies or “transcripts” of Homeric poetry. But I emphasized, in this context, that the existence of such “transcripts” would not have killed the oral reception of this poetry.

§7. And here is where I need to make a more specific clarification, since my use of this word “transcript” in this context has been criticized as inconsistent. The criticism is made in a book by Jonathan L. Ready (2019), with whose work on Homeric poetry I generally agree. But here I must engage in some friendly disagreement concerning his relevant criticism (especially at his p. 178). Although I state, at one point ( Homeric Questions p. 65), that a transcript could be used “to record any given composition and to control the circumstances of any given performance ,” this statement does not contradict a more general statement I make at a later point ( Homeric Questions p. 67), where I speak not about a transcript used as a “control” but simply as “an aid to performance.” I see no inconsistency here, since my point all along (starting at Homeric Questions p. 65) was that a transcript could potentially be used as an aid to performance—but not necessarily so. As for the “aid,” it could take the form of actual “control” over content, but that kind of “aid” would be an extreme case, and I left room for an opposite extreme, that is, in cases where a transcript, even if it exists, is not used at all as any kind of “aid” for performance. Accordingly, I also see no inconsistency in another relevant statement I made in another publication (Nagy 2014:100), where I say that my use of the term transcript “makes it clear that a transcript has no influence on performance.” If this statement (as quoted by Ready p. 178) is taken out of context, then, yes, I would have to restate by saying “a transcript does not necessarily have any influence on performance,” but this same statement, if it were to be read in context, would make such a restatement unnecessary. When I was saying that a transcript, of and by itself, has “no influence” on performance, I was responding to a mis-statement of my views in the work of another Homerist, Minna Skafte Jensen (2011:217), with whom I otherwise also generally agree. In this case, I disagree with her claim that “Nagy’s hypothesis attributes to the written transmission features that are characteristic of oral composition and transmission.” Contesting this mis-statement, I went on to say (Nagy 2014:100): “In fact, my point is just the opposite: period 3 is a time of oral transmission, not written transmission, and that is why I use the word transcript with reference to any possibility of existing texts.” In the same context, Jensen (2011:217) refers to “the dogma concerning the interaction between the two media [that is, the medium of oral performance and the medium of writing a text].” I quote again from my response (Nagy 2014:100): “But I posit no such ‘interaction’, and that is the point of my using the term ‘transcript’.” Also, just as a “transcript” in period 3 does not necessarily influence the oral reception, the same can be said even about a “script,” in the later “period 4,” which I dated as extending from the later part of the fourth century BCE to the middle of the second. Even a “script,” though it could potentially exert more control over a given performance, would not necessarily interfere with the oral reception of Homeric poetry—at least, not in the long run.

§8. In terms of my evolutionary model of Homeric poetry, then, oral reception cannot be equated with textual reception. This model, however, is not all that far removed from a theory developed by researchers who share my interest in studying oral traditions by combining the disciplines of linguistics and anthropology. The theory can be summarized this way: oral performance can become an “oral text.” The very idea of such an “oral text”—which, to my mind at least, is simply a metaphor—is perhaps best expressed in the cross-cultural formulation of Karin Barber (2007:1–2), who describes such an “oral text” as an oral performance that is “woven together in order to attract attention and outlast the moment.” The theory of such an “oral text,” which Barber (again, pp. 1–2) describes as a process of “entextualization” (as an example of other such formulations, I cite Bauman and Briggs 1990:73), has been re-applied in a lengthy book by Jonathan L. Ready (2019) on Homeric “orality” and “textuality.” In this work of Ready, I highlight one particular formulation of his (p. 18): “So performers make an oral text: they impart textuality, the attributes of an utterance capable of outliving the moment, to a verbal act.” This formulation comes close to what I think is happening in Homeric reception: such reception, to borrow the wording of Ready, is “capable of outliving the moment.”

§9. Such a mentality of “outliving the moment” in Homeric performance is encoded, I think, in the mythological framework of a literary form that I have described in earlier work as “Life of Homer” narratives. In the text of such “Lives” of Homer, Homeric poetry as oral performance is alive because Homer, the performer, is still alive. But how does such performance stay alive when Homer’s poetry is no longer performed by Homer? The answer, I think, is to be found in what the “Lives” actually narrate about Homer’s moments of performance.

§10. In a detailed article where I sum up my overall work on the “Lives” of Homer (Nagy 2015.12.18, linked here ), I offer a formula that can help explain why the genre of these “Lives” can keep Homer himself “alive” as the ultimate master of oral performance, just as the Provençal genre of the vida , as I showed in my previous essay for Classical Inquiries (2021.08.23, linked here ), can at least help keep alive the lives and times of a generic troubadour. In what follows, I epitomize the first ten paragraphs of the detailed article of mine that I have just cited, while leaving out the details that I have collected there:

§10.1. The article centers on the surviving texts of “Life of Homer” narrative traditions, to which I will refer hereafter simply as Lives of Homer:

I offer the following system for referring to these Lives, as printed by Allen 1912:

V1 = Vita Herodotea, pp. 192–218 V2 = Certamen, pp. 225–238 V3a = Plutarchean Vita, pp. 238–244 V3b = Plutarchean Vita, pp. 244–245 V4 = Vita quarta, pp. 245–246 V5 = Vita quinta, pp. 247–250 V6 = Vita sexta (the ‘Roman Life’), pp. 250–253 V7 = Vita septima , by way of Eustathius, pp. 253–254 V8 = Vita by way of Tzetzes, pp. 254–255 V9 = Vita by way of Eustathius ( Iliad IV17), p. 255 V10 = Vita by way of the Suda, pp. 256–268 V11 = Vita by way of Proclus, pp. 99–102

These Lives, I argue, can be read as sources of historical information about the reception of Homeric poetry. The information is varied and layered, requiring diachronic as well as synchronic analysis (as always, I use these terms as defined by Saussure 1916:117).

§10.2. The Lives portray the reception of Homeric poetry by narrating a series of events featuring “live” performances by Homer himself. In the narratives of the Lives, Homeric composition is consistently being situated in contexts of oral performance. In effect, the Lives explore the shaping power of positive and even negative responses by the audiences of Homeric poetry in ad hoc situations of oral performance.

§10.3. The narrative strategy of each of the Lives can be described as a staging of Homer’s reception. This staging takes the form of narrating a wide variety of occasions for Homeric performance. A premier occasion, as we shall see, is what can best be described as a pan-Hellenic festival.

§10.4. The Lives of Homer, especially as represented by the Herodotean Vita (= ‘V1’) and by the Certamen (‘The Contest of Homer and Hesiod’ = ‘V2’), highlight the performances of Homer at pan-Hellenic festivals. The background for such highlighting is the overall pan-Hellenic significance of performing Homeric poetry. To appreciate more fully this significance, I concentrate on the testimony of the Lives concerning the reception of Homer in two areas: (1) the Aeolic and Ionic cities of Asia Minor and outlying islands, and (2) the island of Delos, retrospectively figured as the notional center of the future Athenian Empire.

§10.5. The reception of Homer in these two areas has to be understood in the context of the festivals where Homeric poetry was performed. Here I introduce the term “aetiology” as a way of backing up the point I have just made about these pan-Hellenic festivals as the premier occasion of Homeric performance. By “aetiology,” I mean a myth that directly motivates a ritual (Nagy 1999:279). And two most relevant examples of ritual in this case are (1) the very idea of a festival and (2) the more basic idea of a sacrifice. Both ideas, sacrifice and festival , are conveyed by the Greek word thusia , which means not only ‘sacrifice’ but also, metonymically, ‘festival’. The second meaning is clearly attested in Plato Timaeus 26e, where thusia actually refers to a pan-Hellenic festival: in this case, the referent is none other than the premier festival of Athens, the Panathenaia (Nagy 2002:83). In the days of Plato, it was on this occasion, the Feast of the Panathenaia, that the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey were formally performed in Athens (Nagy 2002:9–22). I signal from the start the relevance of the Panathenaia and, more generally, of the word thusia , to my overall argument.

§10.6. I argue that the Lives of Homer functioned as aetiologies for festive occasions where Homeric poetry was seasonally performed and that they must be viewed as myths, not historical facts, about Homer. To say that we are dealing with myths, however, is not at all to say that there is no history to be learned from the Lives. Even though the various Homers of the various Lives are evidently mythical constructs, the actual constructing of myths about Homer can be seen as historical fact (Nagy 1999:ix paragraph 7, with note). The claims made about Homer in the Lives can be analyzed as evidence for the various different ways in which Homeric poetry was appropriated by various different cultural and political centers throughout the ancient Greek-speaking world.

§10.7. Here I need to highlight again my main point about the Lives: all the claims about Homer, in all their varieties, specifically picture Homeric poetry as a medium of oral performance, featuring Homer himself as the master performer.

§10.8. For analyzing diachronically as well as synchronically the reception of Homer as reflected in the Lives, I propose to build a model for the periodization of this reception. Such a model needs to account for the accretive layering of narrative traditions contained within the final textual versions of these Lives. I posit three periods of ongoing reception: pre-Panathenaic, Panathenaic, and post-Panathenaic. By ‘post-Panathenaic’, I mean a period of Homeric reception marked by the usage of graphein ‘write’ in referring to Homer as an author. This usage needs to be distinguished from the usage of the Panathenaic and pre-Panathenaic periods, when Homer is said to poieîn ‘make’ whatever he composes, not to graphein ‘write’ it.

§10.9. The post-Panathenaic period is exemplified by sources like Plutarch and Pausanias, in whose writings Homer is already seen as an author who ‘writes’, graphei , whatever he composes. I cite a few examples: Plutarch De amore prolis 496d, Quaestiones convivales 668d; Pausanias 3.24.11, 8.29.2. The Panathenaic period, by contrast, is exemplified by Plato and Aristotle, in whose writings we still see Homer as an artisan who ‘makes’, poieî , and who is never pictured as one who ‘writes’, graphei . For examples of expressions involving ‘Homer’ as the subject and poieîn as the verb of that subject, I start with Aristotle De anima 404a, Nicomachean Ethics 3.1116a and 7.1145a, De generatione animalium 785a, Poetics 1448a, Politics 3.1278a and 8.1338a, Rhetoric 1.1370b. I cite also Plato Phaedo 94d, Hippias Minor 371a, Republic 2.378d, Ion 531c–d. I note with special interest the usage, here in the Ion and elsewhere, of poiēsis as the inner object of poieîn . Of related interest are collocations of poieîn with generic ho poiētēs ‘the maker’ (= the Poet) as subject, referring by default to Homer: the many examples include Plato Republic 3.392e (ὁ ποιητής φησι) and Aristotle De mundo 400a (ὥσπερ ἔφη καὶ ὁ ποιητής).

§10.10. I translate poieîn as ‘make’ in order to underline the fact that the direct object of this verb is not restricted to any particular product to be made by the subject—if the subject of the verb refers to an artisan. In other words, poieîn can convey the producing of any artifact as the product of any artisan. It is not restricted to the concept of the song / poem as artifact or of the songmaker / poet as artisan. To cite an early example: in Iliad 7.222, the artisan Tukhios epoiēsen ‘made’ the shield of Ajax. By contrast with the verb poieîn , the derivative nouns poiētēs and poiēsis are restricted, already in the earliest attestations, to the production of songs / poems. I stress the exclusion of artifacts other than songs / poems or of artisans other than songmakers / poets. The noun poiēma has likewise been restricted, though not completely; in the usage of Herodotus, for example, poiēma still designates artifacts other than song / poetry (1.25.1, 2.135.3, 4.5.3, 7.85.1). As for the compound noun formant ‑ poios , it is not at all restricted to song or to poetry.

§11. This Greek word poiēma , the earlier meaning of which is ‘artifact’ and the later meaning of which is simply ‘poem’, brings me back to the description, by Karin Barber (2007:1–2), of an “oral text” as an oral performance that is “woven together in order to attract attention and outlast the moment.” Barber’s metaphor, “woven together,” reminds me of the etymology of the word “text,” the metaphorical meaning of which is a “web” that is “woven” (Latin textus )—an artifact that is ever attracting attention, ever outlasting the moment.

Bibliography

Allen, T. W., ed. 1912. Homeri Opera V (Hymns, Cycle, fragments). Oxford.

Barber, K. 2005. “Text and Performance in Africa.” Oral Tradition 20:264–277.

Barber, K. 2007. The Anthropology of Texts, Persons and Publics: Oral and Written Culture in Africa and Beyond . Cambridge.

Bauman, R. 1977. Verbal Art as Performance . Long Grove, IL.

Bauman, R. 2004. A World of Others’ Words: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Intertextuality . Malden, MA.

Bauman, R., and C. L. Briggs. 1990. “Poetics and Performance as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life.” Annual Review of Anthropology 19:59–88.

Bird, G. D. 2010. Multitextuality in the Homeric Iliad: The Witness of Ptolemaic Papyri . Hellenic Studies 43. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Bird.The_Witness_of_Ptolemaic_Papyri.2010 .

Boutière, J., and A.-H. Schutz. 1950. 2nd ed., without Schutz and now, instead, with I.-M. Cluzel, 1964. Biographies des Troubadours: Textes provençaux des xiiie et xive siècles . Toulouse/Paris.

Finnegan, R. 1970. Oral Literature in Africa . Oxford.

Finnegan, R. 1977. Oral Poetry: Its Nature, Significance, and Social Context . Cambridge.

González, J. M. 2013. The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective . Hellenic Studies 47. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_GonzalezJ.The_Epic_Rhapsode_and_his_Craft.2013 .

Jensen, M. S. 1980. The Homeric Question and the Oral-Formulaic Theory . Copenhagen.

Jensen, M. S. 2011. Writing Homer: A study based on results from modern fieldwork . Copenhagen.

Lord, A. B. 1960 (/2000/2019). The Singer of Tales . Harvard Studies in Comparative Literature 24. Cambridge MA. 2nd ed. 2000, with new Introduction, by S. A. Mitchell and G. Nagy. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_LordA.The_Singer_of_Tales.2000 . 3rd edition by D. F. Elmer, 2019. Hellenic Studies 77, Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature 4. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC.

Nagy, G. 1979. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Baltimore. http://www.press.jhu.edu/books/nagy/BofATL/toc.html . Revised ed. with new introduction 1999, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Best_of_the_Achaeans.1999 .

Nagy, G. 1990. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past . Baltimore. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Pindars_Homer.1990 .

Nagy, G. 1996a. Poetry as Performance: Homer and Beyond. Cambridge. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Poetry_as_Performance.1996 .

Nagy, G. 1996b. Homeric Questions . Austin. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homeric_Questions.1996 .

Nagy, G. 2002a. Plato’s Rhapsody and Homer’s Music: The Poetics of the Panathenaic Festival in Classical Athens. Cambridge, MA, and Athens. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Platos_Rhapsody_and_Homers_Music.2002 .

Nagy, G. 2009. “Hesiod and the Ancient Biographical Traditions.” The Brill Companion to Hesiod , ed. F. Montanari, A. Rengakos, and Ch. Tsagalis, 271–311. Leiden. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:Nagy.Hesiod_and_the_Ancient_Biographical_Traditions.2009 .

Nagy, G. 2009|2008. Printed | Online version. Homer the Classic . Hellenic Studies 36. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Classic.2008 .

Nagy, G. 2010. “Homer Multitext project.” Online Humanities Scholarship: The Shape of Things to Come , ed. J. McGann, with A. Stauffer, D. Wheeles, and M. Pickard, 87-112. Rice University Press (ceased operations in 2010). Online version of the article is available at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:Nagy.The_Homer_Multitext_Project.2010 .

Nagy, G. 2010|2009. Printed | Online version. Homer the Preclassic . Berkeley and Los Angeles. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Preclassic.2009 .

Nagy, G. 2011a. “Diachrony and the Case of Aesop.” Classics@ 9: Defense Mechanisms in Interdisciplinary Approaches to Classical Studies and Beyond. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:Nagy.Diachrony_and_the_Case_of_Aesop.2011 .

Nagy, G. 2011b. “The Aeolic Component of Homeric Diction.” Proceedings of the 22nd Annual UCLA Indo-European Conference , ed. S. W. Jamison, H. C. Melchert, and B. Vine, 133–179. Bremen. In Nagy 2012 v1. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:Nagy.The_Aeolic_Component_of_Homeric_Diction.2011 .

Nagy, G. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours . Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013 .

Nagy, G. 2014. Review of Jensen 2011. Gnomon 86:97–101.

Nagy, G. 2015.12.18. “The Lives of Homer as Aetiologies for Homeric Poetry.” Classical Inquiries . https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/life-of-homer-myths-as-evidence-for-the-reception-of-homer/ .

Nagy, G. 2016| 2015. Masterpieces of Metonymy: From Ancient Greek Times to Now . Hellenic Studies 72. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Masterpieces_of_Metonymy.2015 .

Nagy, G. 2016.11.03. “Some jottings on the pronouncements of the Delphic Oracle.” Classical Inquiries . https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/some-jottings-on-the-pronouncements-of-the-delphic-oracle/ .

Nagy, G. 2021.08.23. “Jaufré Rudel, his ‘distant love’, and the death of the distant lover in his vida .” Classical Inquiries . https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/jaufre-rudel-his-distant-love-and-the-death-of-the-distant-lover-in-his-vida/ .

PP . See Nagy 1996a.

PH . See Nagy 1990.

Pickens, R. T. 1977. “Jaufre Rudel et la poétique de la mouvance.” Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 20:323–337.

Pickens, R. T, ed. 1978. The Songs of Jaufré Rudel . Toronto.

Pickens, R. T. 1978b. “La Poétique de Marie de France d’après les Prologues des Lais.” Les Lettres Romanes 32:367–384.

Pickens, R. T. 1994. “‘Old’ Philology and the Crisis of the ‘New’.” In The Future of the Middle Ages: Medieval Literature in the 1990s , ed. W. D. Paden, 53–86. Gainesville, FL.

Ready, J. L. 2019. Orality, Textuality, and the Homeric Epics: An Interdisciplinary Study of Oral Texts, Dictated Texts, and Wild Texts . Oxford.

Saussure, F. de. 1916. Cours de linguistique générale . Paris. Critical ed. 1972 by T. de Mauro.

Zumthor, P. 1972. Essai de poétique médiévale . Paris.

Zumthor, P. 1983. Introduction à la poésie orale . Paris.

Zumthor, P. 1984. La Poésie de la Voix dans la civilisation médiévale . Paris.

Zumthor, P. 1987. La Lettre et la voix: De la “littérature” médiévale . Paris.

Continue Reading

Mast@chs – summer seminar 2021 (friday, july 23): summaries of presentations and discussion, to zeus, by carol rumens, the god and the goat, by rowan ricardo phillips.

Nine Essays on Homer

Michael nagler , university of california, berkeley.

If one did not know that the authors of these varied essays were graduate students, one would assume from their uniformly high quality that one were reading the work of distinguished scholars with whose names one were somehow unfamiliar. The genesis of the collection is an interdisciplinary seminar at Harvard University presided over by Gregory Nagy and Emily Vermeule, with Charles Segal keeping a watchful eye on the proceedings. Those three must be as proud of this volume as of their own distinguished contributions to Homer studies.

The articles are from different perspectives but share a set of historical and critical assumptions and each one of them manages to reveal resonances of meaning in the rich thought-world of epic performance that have hitherto escaped us. That shared set of assumptions is not in itself surprising: excising supposed interpolations, for example, is out of tune with these times and in particular with the work of these students, who, like this reviewer, have been influenced by Prof. Nagy’s view of ‘Homer’ as diachronic process. The approaches are not ‘trendy,’ however, in the sense of being overly concerned with theory (either deconstructive or oral) or very strongly ideological: Andrea Kouklanakis is well aware that Thersites and his various ineptitudes “can be seen as a linguistic metaphor for the Homeric construction of rebellion” (45; though Thalmann’s work on Thersites is not mentioned in this essay), but she does not reduce the epic to a tract on social control systems or contort the overlay of Thersites’s social and speech-performative handicaps into some kind of post-modern theory that would deflect attention from any reality beyond the text itself. Though I, for one, found myself more often in disagreement with this essay than with most of the others, it is, like them, as balanced as it is revealing.

The collection is ‘interdisciplinary’ in the sense that it reflects the ample range of disciplines in which Profs. Nagy and Vermeule have worked, and then some, but the end result is not the kind of book where an archeologist would only read one part and a literary person another: an interesting coherence has emerged. Anyone interested in seeing more deeply into how Homer worked (what- or whoever one takes ‘Homer’ to be) will likely read it with uniform interest from cover to cover. In the introduction, Editors Carlisle and Levaniouk articulate a number of sound methodological principles which characterize the essays: etymologies, for example, “can be abused by being applied arbitrarily, but they can also become relevant when they have demonstrably poetic associations and cohere with other elements of the narrative”; and “if an etymology is “confirmed” by the context, it becomes a powerful tool for uncovering a diachronic depth of associations that enrich our understanding of Homeric poetry” (xv and xix). This is ‘clarifying Homer from Homer’ in the best sense, and all nine of these writers demonstrate that repeatedly, not only in connection with etymology (around which two of the essays revolve) but in other ways as well.

One is tempted to get into a detailed engagement with all nine of these studies, but perhaps it would be more practical to highlight a few points in a some of them — a hard enough choice since, as mentioned, they are uniformly rewarding.

Olga Levaniouk’s essay on Penelope, beginning with the “complex interactions between the pênelops of poetry and mythology and the pênelops of natural history” (96), systematically, and with admirable sensitivity, traces the idea of the weeping bird in Greek (and I might add, Indian) poetic associations through the meandering, branching and reconnecting synapses of the mythology, that lead — as mythological associations ultimately do when pursued with due tenacity — to ‘first things’, in this case the solar mythology of the Odyssey with which we are most familiar from the work of Douglas Frame. Today we tend to be most interested in the social relevance of these ‘cosmic’ themes, and Levaniouk in fact treats the liminal status of Penelope with great empathy. Again, what is noteworthy is the balance of all these dimensions, and L. treats them as an organic whole, which is exactly what they are, for poetry, myth and the tensions of human social interaction gain richness of association from each other at every point. The essay gives us exactly what we would want from good criticism and searching scholarship: recovery of lost associations, a great gain in our appreciation of ‘the poet’s’ richness. It would have been admirable enough as a mature piece of research that leaves no reference unturned (as far as I can see); but it is also full of nuanced observations. To cite just one: “The expression οἴκτρ’ ὀλοφυρομένη ‘piteously weeping’, used here about Penelope … is a metrical doublet of παῖδ’ ὀλοφυρομένη ‘bewailing her child’ used to describe the nightingale in Book 19″ (109), a topos brought into constant association with the state of Penelope as a woman caught by conflicting loyalties and uncertain future, and a ‘reading’ of that state.

Yet, as L. points out, Penelope’s halcyon / nightingale / pênelops identity has other dimensions, and there are resonances with other bird ‘species’ (or topoi) which broaden the protectiveness of birds toward their young in a way that is equally relevant to Penelope’s typology in the Odyssey. Here one is reminded that geese (one of the birds brought into resonance with Penelope) were known in antiquity not only for “guarding their nest” (97) but for guarding cities: most famously Rome. This is much later than the Greek sources relevant to Homer, of course, but the fact is that Penelope and Odysseus together ‘save’ not only their well-built home and its holdings (taking the text’s viewpoint, or one of them, that the suitors are disruptive interlopers): in doing so they emblematically save the world-order itself.

Several of the essays deal with animals and birds. John Watrous (“Artemis and the Lion: Two similes in Odyssey 6,” 165-177) argues, intriguingly, that Circe’s theriomorphic transformation of Odysseus’s men brings into the ‘tenor’ of the narrative line what is elsewhere always left in the ‘vehicle’ of simile (a reversal, one might add, that is typical of the mirror-world of the Adventures), so that “the spells of the goddess threaten to collapse” these poetic worlds and “It is only through the timely intervention of the master shape-changer Hermes that Odysseus is able to resist Circe’s spells and force the goddess to restore tenor and vehicle to their rightful places by returning his men to their human forms” (175).

Brian Breed (“Odysseus Back Home and Back From the Dead,” 137-164) shows that the returned hero’s apparently harsh and unnecessary test of Laertes which has bothered critics for millenia is mandated by the demands of a partly-concealed theme, the dreaded alternative ‘return’ of Odysseus as avenging hero. Thomas E. Jenkins (“Homêros ekainopoiêse: Theseus, Aithra and Variation in Homeric Myth-Making”, 207-226) shows that Iliad 3.144 cannot be excised from the Teichoscopia because it is part of a ring-composition by means of which Helen summons up what is a poignantly impossible story in this context: her rescue from abduction by her Tyndareid brothers. Jenkins is doing much more than saving one line from the athetizer’s dagger, he serves up eye-opening repercussions for our understanding of the handling of myth and even more generally ‘innovation’ in oral epic composition, and of the way the skilled performer can invoke themes into a subtext which plays against the main (selected, ‘true’) narrative without being fully realized in it.

These are only examples of the rich work offered by every one of the nine contributors to this volume. Outside of a very few tiny mistranslations ( ἔχω , on p. 3, is probably subjunctive; φίλος, φίλη is the ‘inalienable possession marker’, not ‘dear’) this is fine, mature work. One would indeed have liked to be a fly on the wall in that seminar room. But for those of us who did not enjoy that privileged coign of vantage, this book will do nicely.

Tomorrow, When the War Began

John marsden, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions, homer quotes in tomorrow, when the war began.

I went for a walk back up the track, to the last of Satan’s Steps. The sun had already warmed the great granite wall and I leaned against it with my eyes half shut, thinking about our hike, and the path and the man who’d built it, and this place called Hell. “Why did people call it Hell?” I wondered. All those cliffs and rocks, and that vegetation, it did look wild. But wild wasn’t Hell. Wild was fascinating, difficult, wonderful. No place was Hell, no place could be Hell. It’s the people calling it Hell, that’s the only thing that made it so. People just sticking names on places, so that no one could see those places properly any more. Every time they looked at them or thought about them the first thing they saw was a huge big sign saying “Housing Commission” or “private school” or “church” or “mosque” or “synagogue.” They stopped looking once they saw those signs.

Robyn took over. “We’ve got to think, guys. I know we all want to rush off, but this is one time we can’t afford to give in to feelings. There could be a lot at stake here. Lives even. We’ve got to assume that something really bad is happening, something quite evil. If we’re wrong, then we can laugh about it later, but we’ve got to assume that they’re not down the pub or gone on a holiday.”

“Maybe all my mother’s stories made me think of it before you guys. And like Robyn said before, if we’re wrong,” he was struggling to get the words out, his face twisting like someone having a stroke, “if we’re wrong you can laugh as long and loud as you want. But for now, for now, let’s say it’s true. Let’s say we’ve been invaded. I think there might be a war.”

Homer was becoming more surprising with every passing hour. It was getting hard to remember that this fast-thinking guy, who’d just spent fifteen minutes getting us laughing and talking and feeling good again, wasn’t even trusted to hand out the books at school.

We’ve got to stick together, that’s all I know. We all drive each other crazy at times, but I don’t want to end up here alone, like the Hermit. Then this really would be Hell. Humans do such terrible things to each other that sometimes my brain tells me they must be evil. But my heart still isn’t convinced. I just hope we can survive.

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Winslow homer (1836–1910).

Boys in a Dory

Winslow Homer

Prisoners from the Front

Eagle Head, Manchester, Massachusetts (High Tide)

A Basket of Clams

The Veteran in a New Field

Inside the Bar

Northeaster

Flower Garden and Bungalow, Bermuda

Snap the Whip

The Gulf Stream

Fishing Boats, Key West

Dressing for the Carnival

H. Barbara Weinberg Department of American Paintings and Sculpture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

Winslow Homer (1836–1910) is regarded by many as the greatest American painter of the nineteenth century. Born in Boston and raised in rural Cambridge, he began his career as a commercial printmaker , first in Boston and then in New York, where he settled in 1859. He briefly studied oil painting in the spring of 1861. In October of the same year, he was sent to the front in Virginia as an artist-correspondent for the new illustrated journal Harper’s Weekly . Homer’s earliest Civil War paintings, dating from about 1863, are anecdotal, like his prints. As the war drew to a close, however, such canvases as The Veteran in a New Field ( 67.187.131 ) and Prisoners from the Front ( 22.207 ) reflect a more profound understanding of the war’s impact and meaning.

For Homer, the late 1860s and the 1870s were a time of artistic experimentation and prolific and varied output. He resided in New York City, making his living chiefly by designing magazine illustrations and building his reputation as a painter, but he found his subjects in the increasingly popular seaside resorts in Massachusetts and New Jersey, and in the Adirondacks, rural New York State, and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Late in 1866, motivated probably by the chance to see two of his Civil War paintings at the Exposition Universelle, Homer had begun a ten-month sojourn in Paris and the French countryside. While there is little likelihood of influence from members of the French avant-garde, Homer shared their subject interests, their fascination with serial imagery, and their desire to incorporate into their works outdoor light, flat and simple forms (reinforced by their appreciation of Japanese design principles ), and free brushwork.

Women at leisure and children at play or simply preoccupied by their own concerns were regular subjects for the artist in the 1870s. In addition to expanding his mastery of oil paint during that decade, Homer began to create watercolors, and their success enabled him to give up his work as a freelance illustrator by 1875. He had been in Virginia during the war , and he returned there at least once during the mid-1870s, apparently to observe and portray what had happened to the lives of former slaves during the first decade of Emancipation.

In the early 1880s, Homer came increasingly to desire solitude, and his art took on a new intensity. In 1881, he traveled to England on his second and final trip abroad. After passing briefly through London, he settled in Cullercoats, a village near Tynemouth on the North Sea, remaining there from the spring of 1881 to November 1882. He became sensitive to the strenuous and courageous lives of its inhabitants, particularly the women, whom he depicted hauling and cleaning fish, mending nets, and, most poignantly, standing at the water’s edge, awaiting the return of their men. When the artist returned to New York, both he and his art were greatly changed.

In the summer of 1883, Homer moved from New York to Prouts Neck, Maine, a peninsula ten miles south of Portland. Except for vacation trips to the Adirondacks, Canada, Florida, and the Caribbean, where he produced dazzling watercolors , Homer lived at Prouts Neck until his death. He enjoyed isolation and was inspired by privacy and silence to paint the great themes of his career: the struggle of people against the sea and the relationship of fragile, transient human life to the timelessness of nature. In ambitious works of the 1880s, men challenge the ocean’s power with their own strength and cunning or respond to the ocean’s overwhelming force in scenes of dramatic rescue. By about 1890, however, Homer left narrative behind to concentrate on the beauty, force, and drama of the sea itself. In their dynamic compositions and richly textured passages, his late seascapes capture the look and feel (and even suggest the sound) of masses of onrushing and receding water. For Homer’s contemporaries, these were the most extravagantly admired of all his works. They remain among his most famous today, appreciated for their virtuoso brushwork, depth of feeling, and hints of modernist abstraction.

Weinberg, H. Barbara. “Winslow Homer (1836–1910).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/homr/hd_homr.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Cikovsky, Nicolai, Jr., and Franklin Kelly. Winslow Homer . Exhibition catalogue. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Additional Essays by H. Barbara Weinberg

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) .” (July 2011)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ American Impressionism .” (October 2004)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) .” (October 2004)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910 .” (September 2009)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ Americans in Paris, 1860–1900 .” (October 2006)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ Childe Hassam (1859–1935) .” (October 2004)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) .” (April 2010)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926) .” (October 2004)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ Thomas Eakins (1844–1916): Painting .” (October 2004)

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “ The Ashcan School .” (April 2010)

Related Essays

- America Comes of Age: 1876–1900

- American Impressionism

- American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910

- Americans in Paris, 1860–1900

- Nineteenth-Century American Drawings

- Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907)

- The Barbizon School: French Painters of Nature

- Childe Hassam (1859–1935)

- Claude Monet (1840–1926)

- The Daguerreian Era and Early American Photography on Paper, 1839–60

- Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

- Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900)

- Frederic Remington (1861–1909)

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- The Hudson River School

- Impressionism: Art and Modernity

- John Singer Sargent (1856–1925)

- Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926)

- The Nabis and Decorative Painting

- The Print in the Nineteenth Century

- Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823–1880)

- Thomas Cole (1801–1848)

- Thomas Eakins (1844–1916): Painting

- Unfinished Works in European Art, ca. 1500–1900

- Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850

- The United States and Canada, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- 19th Century A.D.

- American Art

- American Barbizon School

- American Scene Painting

- Great Britain and Ireland

- North America

- Printmaking

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Homer, Winslow

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Sea Change” by H. Barbara Weinberg

- Connections: “Perfection” by Barbara Weinberg

- Connections: “Water” by Lyn Younes

Biography of Homer

Beyond a few fragments of information, historians and classicists can only speculate about the life of the man who composed The Iliad and The Odyssey . The details are few. We do not even know the century in which he lived, and it is difficult to say with absolute certainty that the same poet composed both works. The Greeks attributed both of the epics to the same man, and we have little hard evidence that would make us doubt the ancient authorities, but uncertainty is a constant feature of scholarly work dealing with Homer's era of Greek history.

The Greeks hailed him as their greatest poet, as well as their first. Although the Greeks recognized other poets who composed in Greek before Homer, no texts from these earlier poets survived. Perhaps they were lost, or perhaps they were never written down; Homer himself was probably on the cusp between the tradition of oral poetry and the new invention of written language. Texts of The Iliad and The Odyssey existed from at least the sixth century BC, and probably for a considerable span of time before that. These two great epic poems also had a life in performance: through the centuries, professional artists made their living by reciting Homer, performing the great epics for audiences that often know great parts of the poem by heart.

It is impossible to pin down with any certainty when Homer lived. Eratosthenes gives the traditional date of 1184 BC for the end of the Trojan War, the semi-mythical event that forms the basis for the Iliad. The great Greek historian Herodotus put the date at 1250 BC. These dates were arrived at in a very approximate manner; Greek historians usually used genealogy and estimation when trying to find the dates for events in the distant past. But Greek historians were far less certain about the dates for Homer's life. Some said he was a contemporary of the events of The Iliad , while others placed him sixty or a hundred or several hundred years afterward. Herodotus estimated that Homer lived and wrote in the ninth century BC. He almost certainly lived in one of the Greek city-states in Asia Minor. All of the traditional sources say that he was blind.

Over the course of millennia of scholarly speculation, prevailing theories about Homer and his relationship to his work have had time to change and change again. At various times over the centuries, scholars have suggested that he was only a transmitter, or that he never existed, and the epics attributed to him were the patchwork effort of generations of bards. Modern scholars, however, tend to accept that The Iliad and The Odyssey are more than amalgams handed down from antiquity, and that there was in fact a great poet who had a hand in creating these epics in the forms we know today. Current scholarship holds that Homer was a great bard who lived between the eighth and seventh centuries BC. Although there is little doubt that Homer inherited a massive amount of material from generations of bards before him, most scholars believe now that Homer was an innovator and an original artist as well as a transmitter. Writing probably played a role in the composition of his great poems. Current theories depict Homer as a master of oral poetry who used the new invention of writing to aid him in composing epics on a grander scale than had ever been done before. There are signs in The Iliad that might suggest unfinished revision; these massive projects may have been reworked again and again over the course of the poet's whole life. A performer as well as a poet, Homer may have composed the poems through a mixture of utilizing old material, writing and revising, and oral improvisation.

Little can be known with certainty. But even though the details of Homer's life remain -- and probably will always remain -- an enigma, his great epics come down to us intact. His works have formed a foundation for all the Western literature that has followed, and his characters and stories have had an impact on three thousand years' worth of readers. Facts about the poet's life can do little to add to that legacy. Legend says that as a child, Alexander the Great slept with a copy of The Iliad under his pillow; the fact that Alexander was neither the first nor the last boy to do so says more about Homer's genius than any biography could, no matter how detailed or complete.

Study Guides on Works by Homer

Iliad homer.

Consisting of 15,693 lines of verse, the Iliad has been hailed as the greatest epic of Western civilization. Although we know little about the time period when it was composed and still less about the epic's composer, the Iliad's influence on...

- Study Guide

- Lesson Plan

The Odyssey Homer

Most likely written between 750 and 650 B.C., The Odyssey is an epic poem about the wanderings of the Greek hero Odysseus following his victory in the Trojan War (which, if it did indeed take place, occurred in the 12th-century B.C. in Mycenaean...

essays by Thomas Van Nortwick, notes by Rob Hardy

Book 12 Essays

By Thomas Van Nortwick

Odysseus and his crew return to Circe’s island and bury Elpenor. Odysseus recounts his adventures to Circe.

Bringing his hero back from Hades, the poet faces some challenges. After the extraordinary encounters with the dead, there might well be a letdown in dramatic tension and thus in the audience’s attention. We suspect that Ithaka cannot be too far in the distance at this point, and we might be getting eager to move on to the showdown with the suitors, which Homer has been dangling before us since Zeus’s reply to Athena in Book Five:

My child, what is this word that has escaped your teeth? Is this not your plan, as you have counseled it, that Odysseus will return and take revenge on those men?

Odyssey 5.21–23

We also know that this poet likes nothing better than to delay fulfilling expectations he has stirred in us, keeping us engaged. So perhaps the homecoming is on the horizon, but probably not right away. Meanwhile, when Odysseus reaches Calypso’s island, he is alone. And we learned in the first few verses of the poem that Helios did away with the rest of the crew because they ate his sacred cattle. We have yet to discover how that happened.

The book begins with the soothing rhythms of familiar traditional language, as if to mark a return to the comfort of the human world as Odysseus and the crew left it when they went into the Underworld:

‘αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ ποταμοῖο λίπεν ῥόον Ὠκεανοῖο νηῦς, ἀπὸ δ᾽ ἵκετο κῦμα θαλάσσης εὐρυπόροιο νῆσόν τ᾽ Αἰαίην, ὅθι τ᾽ Ἠοῦς ἠριγενείης οἰκία καὶ χοροί εἰσι καὶ ἀντολαὶ Ἠελίοιο, νῆα μὲν ἔνθ᾽ ἐλθόντες ἐκέλσαμεν ἐν ψαμάθοισιν, ἐκ δὲ καὶ αὐτοὶ βῆμεν ἐπὶ ῥηγμῖνι θαλάσσης: ἔνθα δ᾽ ἀποβρίξαντες ἐμείναμεν Ἠῶ δῖαν. ἦμος δ᾽ ἠριγένεια φάνη ῥοδοδάκτυλος Ἠώς...

But when the ship left the streams of the Ocean, and came to the waves of the wide-running sea and the island of Aiaia, where lie the house of early Dawn and her dancing spaces and the rising of Helios, we landed there and drove the ship up on the sand and jumped out on the edge of the sea, drifting off to sleep to await bright Dawn. But when early born, rosy fingered Dawn appeared…

Odyssey 12.1–8

Odysseus sends his men back to the “house of Circe” to retrieve the body of Elpenor (9) and we note the closing of the circle that began with the first ill-fated visit in Book Ten (10.203–243). Circe reappears as a boundary figure like Siduri the barkeep on the edge of the “waters of death” in The Epic of Gilgamesh , with each figure marking the entrance to and exit from the Underworld.

The next six verses cover the funeral and burial of Elpenor, a swift conclusion to that bifurcated episode. The poet seems intent on moving on, leaving the grim darkness behind, speeding toward the next part of the story. Vergil’s version of this episode in the Aeneid , the burial of Misenus, covers fifty verses ( Aen. 6.156–182; 212–235), a somber recollection of the dead man’s life, followed by a meticulous account of the rites themselves. Comparing the two passages is a lesson in how tone and structure can influence our perception of character. While he is expansive in other descriptions of burial ( Il. 23.108–153; 24.788–804; Od. 24.43–97), Homer’s style here is relatively spare and workmanlike: weeping, the crew members gather wood, burn the body, then heap up the funeral mound and plant an oar on top. Vergil’s style is much more lyrical, softening the stark reality of the death that occasions it. His full description of the rites adds a solemn air to the passage, while situating the burial in the Italian landscape. We get the impression that Homer is not interested in Elpenor, except as an example of the perils of low self-control. By bringing him back to our attention, however briefly, the poet tunes our ears for the crew’s much more catastrophic failure of self-control with the cattle of the sun and, with the final image of the oar, Odysseus’s own death far in the future. Vergil’s Misenus, on the other hand, comes alive for us in the affectionate biography that precedes his burial. The event itself celebrates the Trojans’ final arrival—after may false starts—at their new homeland and ends by focusing on the landscape again. Homer’s aims are structural and thematic, the man and his burial fixed economically in our minds by the planting of the oar. Vergil’s passage is all about tone and atmosphere, inviting us to admire the beautiful new land, which forms a poignant backdrop for the final celebration of a worthy man.