An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.19(7); 2022 Jul

Why restricting access to abortion damages women’s health

The plos medicine editors.

Public Library of Science, San Francisco, California, United States of America

Dr. Caitlin Moyer discusses the implications, for women globally, of restricting access to abortion care.

In late June, the landmark Roe v . Wade ruling was overturned by the United States Supreme Court, a decision, decried by human rights experts at the United Nations [ 1 ], that leaves many women and girls without the right to obtain abortion care that was established nearly 50 years ago. The consequences of limited or nonextant access to safe abortion services in the US remain to be seen; however, information gleaned from abortion-related policies worldwide provides insight into the likely health effects of this abrupt reversal in abortion policy. The US Supreme Court’s decision should serve to amplify the global call for strategies to mitigate the inevitable repercussions for women’s health.

Upholding reproductive rights is crucial for the health of women and girls worldwide, and access to a safe abortion is central to this, yet policies in several countries either severely limit or actively prevent access to appropriate abortion care and services [ 2 ]. However, there is little to suggest that those countries and jurisdictions with abortion bans or heavily restrictive laws see fewer abortions performed. According to a modeling study of pregnancy intentions and abortion from the 1990s to 2019, rates of unintended pregnancies ending in abortion are broadly similar regardless of a country’s legal status of abortion, and unintended pregnancy rates are higher among countries with abortion restrictions [ 3 ]. Abortion is widely considered to be a low-risk procedure. Abortion-related deaths most likely occur in the context of unsafe abortion practices and are reported to account for 8% (95% UI 4.7–13.2%) of maternal deaths [ 4 ], making them a top direct contributor to maternal deaths globally, alongside hemorrhage, hypertension, and sepsis. Restrictive abortion policies may not lower the overall rates of abortion, but they can drive increasing rates of unsafe abortions, as women resort to seeking abortions covertly. Such abortions are often performed by untrained practitioners or involve harmful methods. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most abortions that take place in countries with restrictive abortion access policies are not considered safe [ 5 ], potentially contributing to maternal morbidity and mortality. A study of 162 countries found that maternal mortality rates are lower in countries with more flexible abortion access laws [ 6 ], suggesting that changes in abortion policies could have grievous implications for maternal deaths.

It is not yet known if the reneging of federal protection of abortion rights will impact maternal deaths in the US; however, in the years following the 1973 Roe v . Wade decision, numbers of reported deaths associated with illegal abortions, defined as those performed by an unlicensed practitioner, declined, hovering between zero and 2 deaths from the 1980s to 2018, down from 35 in 1972 [ 7 ] and 19 reported in 1973 [ 8 ]. It is possible that limits on access to timely and safe abortion care could drive this number back up and add to the already unacceptably high maternal mortality rate in the US, potentially exacerbating the persistent disparities in maternal mortality based on socioeconomic deprivation, race and ethnicity, and other factors [ 9 ].

Legal and social barriers that impede access to safe abortions are detrimental to the health and survival of women and girls; thus, constructing policies ensuring access to safe abortion services should be an urgent priority. Placing undue hurdles between women and access to abortion care is associated with undesirable health outcomes. For example, a 2011 change to medication abortion laws in one US state that involved increased medication costs and restricted the timing and location where abortion services could be provided was associated with an increase in rates of women requiring additional medical interventions [ 10 ]. Lending international weight to this argument, dissolution of barriers to safe abortion access was emphasized in the March 2022 update of WHO guidance on abortion care [ 11 ], echoing a 2018 comment on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights released by the United Nations Human Rights Committee [ 12 ] that called on member states to remove existing barriers and not enact new restrictions on provision of safe abortion services so that pregnant women and girls do not need to turn to unsafe abortions.

In jurisdictions where prohibitive policies exist, more could be done to counter the impacts of new barriers by changing how abortion care is delivered and increasing accessibility. Protocols for the safe self-management of abortion can be implemented alongside provision of information and provider support. WHO guidance [ 11 ] suggests expanding the breadth of practitioners authorized to prescribe medical abortions to include nurses, midwives, and other cadres of healthcare workers. The guidelines also mention telemedicine as an approach to circumvent obstacles to seeking safe abortion services [ 11 ]. For those with access to the necessary technology, telemedicine services together with self-management of medication abortion can overcome travel-related barriers and ensure the privacy of those seeking treatment. Demands for telehealth services increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and, according to one study, remote provision of abortion services in the US may be a promising option to counteract barriers and facilitate access [ 13 ].

In 2022, restrictive policies or outright bans on abortion services are discriminatory against women, obstructing their right to maintain autonomy over their own sexual and reproductive health. A post- Roe legal landscape that renders abortion more difficult or impossible to obtain safely will exacerbate an increasingly bleak picture of maternal health in the US; however, the US is just one example where increased effort is needed to overcome barriers to improving women’s healthcare. The reality is that such barriers continue to represent a threat to the health of women worldwide. Evidence-based changes to policy and practice that break down barriers and build new roads are required to enable women to access the healthcare they need.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

The PLOS Medicine editors are Raffaella Bosurgi, Callam Davidson, Philippa Dodd, Louise Gaynor-Brook, Caitlin Moyer, Beryne Odeny, and Richard Turner.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Abortion research that matters: Using core outcomes to enable systematic review

Affiliations.

- 1 Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts, Boston, MA, United States.

- 2 Cochrane Fertility Regulation Review Group, Portland, OR, United States; Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Evidence-based Practice Center, Portland, OR, United States.

- 3 Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Evidence-based Practice Center, Portland, OR, United States; Department of OB/GYN, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, United States.

- 4 Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Evidence-based Practice Center, Portland, OR, United States; Department of OB/GYN, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, United States. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 36055361

- DOI: 10.1016/j.contraception.2022.05.014

Keywords: Abortion; GRADE; Outcomes; Standard outcomes; Systematic reviews.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Correcting the scientific record on abortion and mental health outcomes. Littell JH, Abel KM, Biggs MA, Blum RW, Foster DG, Haddad LB, Major B, Munk-Olsen T, Polis CB, Robinson GE, Rocca CH, Russo NF, Steinberg JR, Stewart DE, Stotland NL, Upadhyay UD, van Ditzhuijzen J. Littell JH, et al. BMJ. 2024 Feb 27;384:e076518. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-076518. BMJ. 2024. PMID: 38413135 No abstract available.

- Rhesus isoimmunisation in unsensitised RhD-negative individuals seeking abortion at less than 12 weeks' gestation: a systematic review. Chan MC, Gill RK, Kim CR. Chan MC, et al. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2022 Jul;48(3):163-168. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2021-201225. Epub 2021 Nov 24. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2022. PMID: 34819315 Free PMC article. Review.

- Standardizing abortion research outcomes (STAR): Results from an international consensus development study. Whitehouse KC, Stifani BM, Duffy JMN, Kim CR, Creinin MD, DePiñeres T, Winikoff B, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Blum J, Sherman RB, Lavelanet AF, Brahmi D, Grossman D, Tamang A, Gebreselassie H, Ponce de Leon RG, Ganatra B. Whitehouse KC, et al. Contraception. 2021 Nov;104(5):484-491. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.07.004. Epub 2021 Jul 14. Contraception. 2021. PMID: 34273335 Free PMC article.

- Women's experiences of induced abortion resulting from unplanned pregnancy: a qualitative systematic review protocol. Marques PF, Coelho EAC, Bertolozzi MR, Hoga LAK, Fonseca JG, Rodrigues IR. Marques PF, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018 Nov;16(11):2097-2102. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003594. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018. PMID: 30439745

- [EARLY AND HABITUAL INTERRUPTION OF PREGNANCY]. DA CUNHA DP. DA CUNHA DP. Rev Clin Inst Matern Lisb. 1963 Jul-Dec;14:5-22. Rev Clin Inst Matern Lisb. 1963. PMID: 14242616 Review. Portuguese. No abstract available.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Why restricting access to abortion damages women’s health

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Public Library of Science, San Francisco, California, United States of America

- The PLOS Medicine Editors

Published: July 26, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004075

- Reader Comments

Citation: The PLOS Medicine Editors (2022) Why restricting access to abortion damages women’s health. PLoS Med 19(7): e1004075. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004075

Copyright: © 2022 The PLOS Medicine Editors. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors’ individual competing interests are at http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/s/staff-editors . PLOS is funded partly through manuscript publication charges, but the PLOS Medicine Editors are paid a fixed salary (their salaries are not linked to the number of papers published in the journal).

The PLOS Medicine editors are Raffaella Bosurgi, Callam Davidson, Philippa Dodd, Louise Gaynor-Brook, Caitlin Moyer, Beryne Odeny, and Richard Turner.

In late June, the landmark Roe v . Wade ruling was overturned by the United States Supreme Court, a decision, decried by human rights experts at the United Nations [ 1 ], that leaves many women and girls without the right to obtain abortion care that was established nearly 50 years ago. The consequences of limited or nonextant access to safe abortion services in the US remain to be seen; however, information gleaned from abortion-related policies worldwide provides insight into the likely health effects of this abrupt reversal in abortion policy. The US Supreme Court’s decision should serve to amplify the global call for strategies to mitigate the inevitable repercussions for women’s health.

Upholding reproductive rights is crucial for the health of women and girls worldwide, and access to a safe abortion is central to this, yet policies in several countries either severely limit or actively prevent access to appropriate abortion care and services [ 2 ]. However, there is little to suggest that those countries and jurisdictions with abortion bans or heavily restrictive laws see fewer abortions performed. According to a modeling study of pregnancy intentions and abortion from the 1990s to 2019, rates of unintended pregnancies ending in abortion are broadly similar regardless of a country’s legal status of abortion, and unintended pregnancy rates are higher among countries with abortion restrictions [ 3 ]. Abortion is widely considered to be a low-risk procedure. Abortion-related deaths most likely occur in the context of unsafe abortion practices and are reported to account for 8% (95% UI 4.7–13.2%) of maternal deaths [ 4 ], making them a top direct contributor to maternal deaths globally, alongside hemorrhage, hypertension, and sepsis. Restrictive abortion policies may not lower the overall rates of abortion, but they can drive increasing rates of unsafe abortions, as women resort to seeking abortions covertly. Such abortions are often performed by untrained practitioners or involve harmful methods. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most abortions that take place in countries with restrictive abortion access policies are not considered safe [ 5 ], potentially contributing to maternal morbidity and mortality. A study of 162 countries found that maternal mortality rates are lower in countries with more flexible abortion access laws [ 6 ], suggesting that changes in abortion policies could have grievous implications for maternal deaths.

It is not yet known if the reneging of federal protection of abortion rights will impact maternal deaths in the US; however, in the years following the 1973 Roe v . Wade decision, numbers of reported deaths associated with illegal abortions, defined as those performed by an unlicensed practitioner, declined, hovering between zero and 2 deaths from the 1980s to 2018, down from 35 in 1972 [ 7 ] and 19 reported in 1973 [ 8 ]. It is possible that limits on access to timely and safe abortion care could drive this number back up and add to the already unacceptably high maternal mortality rate in the US, potentially exacerbating the persistent disparities in maternal mortality based on socioeconomic deprivation, race and ethnicity, and other factors [ 9 ].

Legal and social barriers that impede access to safe abortions are detrimental to the health and survival of women and girls; thus, constructing policies ensuring access to safe abortion services should be an urgent priority. Placing undue hurdles between women and access to abortion care is associated with undesirable health outcomes. For example, a 2011 change to medication abortion laws in one US state that involved increased medication costs and restricted the timing and location where abortion services could be provided was associated with an increase in rates of women requiring additional medical interventions [ 10 ]. Lending international weight to this argument, dissolution of barriers to safe abortion access was emphasized in the March 2022 update of WHO guidance on abortion care [ 11 ], echoing a 2018 comment on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights released by the United Nations Human Rights Committee [ 12 ] that called on member states to remove existing barriers and not enact new restrictions on provision of safe abortion services so that pregnant women and girls do not need to turn to unsafe abortions.

In jurisdictions where prohibitive policies exist, more could be done to counter the impacts of new barriers by changing how abortion care is delivered and increasing accessibility. Protocols for the safe self-management of abortion can be implemented alongside provision of information and provider support. WHO guidance [ 11 ] suggests expanding the breadth of practitioners authorized to prescribe medical abortions to include nurses, midwives, and other cadres of healthcare workers. The guidelines also mention telemedicine as an approach to circumvent obstacles to seeking safe abortion services [ 11 ]. For those with access to the necessary technology, telemedicine services together with self-management of medication abortion can overcome travel-related barriers and ensure the privacy of those seeking treatment. Demands for telehealth services increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and, according to one study, remote provision of abortion services in the US may be a promising option to counteract barriers and facilitate access [ 13 ].

In 2022, restrictive policies or outright bans on abortion services are discriminatory against women, obstructing their right to maintain autonomy over their own sexual and reproductive health. A post- Roe legal landscape that renders abortion more difficult or impossible to obtain safely will exacerbate an increasingly bleak picture of maternal health in the US; however, the US is just one example where increased effort is needed to overcome barriers to improving women’s healthcare. The reality is that such barriers continue to represent a threat to the health of women worldwide. Evidence-based changes to policy and practice that break down barriers and build new roads are required to enable women to access the healthcare they need.

- 1. United Nations, Human Rights Office: UN Human Rights Media Center [Internet]. Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR); c1996–2022. Joint web statement by UN Human rights experts on Supreme Court decision to strike down Roe v. Wade; 2022 Jun 24 [cited 30 Jun 2022]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2022/06/joint-web-statement-un-human-rights-experts-supreme-court-decision-strike-down ]

- 2. Center for Reproductive Rights. The World’s Abortion Laws [Internet]. New York (NY): Center for Reproductive Rights; c1992–2022. [cited June 30, 2022]. Available from: https://reproductiverights.org/maps/worlds-abortion-laws/

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 11. World Health Organization. Abortion Care Guideline. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 Mar 8. 170 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039483 .

- 12. United Nations, Human Rights Committee (124th session (8 Oct– 2 Nov 2018). General comment no. 36, Article 6, Right to life. Geneva: UN Human Rights Committee; 2019 Sep 3. 21 p.

May 5, 2022

Abortion Rights Are Good Health Care and Good Science

Restricting access to abortion goes against science, safety, and human dignity and portends a dangerous future

By The Editors

Abortion rights demonstrators outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Wednesday, May 4, 2022.

Valerie Plesch/Bloomberg via Getty Images

The U.S. Supreme Court is about to make a huge mistake.

If the leaked draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is a true indication of the Court’s will, federal abortion rights in this country are about to be struck down. In doing so the Court will not only side against popular opinion on a crucial issue of bodily autonomy, but also signal that politics and religion play a more important role in health care than do science and evidence.

For almost 50 years people in the U.S. who have needed to end a pregnancy have had a legal right to do so. Accessibility and affordability have always been barriers, and anti-abortion lawmakers have chipped away at this right, set forth in Roe v. Wade , but the ability to get a safe and legal abortion before fetal viability was settled law.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The new decision would strike down Roe and Planned Parenthood v. Casey , an opinion that overturned a Pennsylvania law that required a pregnant married woman to notify her husband in order to obtain abortion services. Many states, mainly governed by conservative lawmakers, have already passed or are planning to introduce laws that either ban abortion outright or put such severe restrictions on this medical procedure that it will be practically impossible to legally end a pregnancy. Some states will make criminals of doctors and other health care providers who perform abortions. Some laws set to go into effect after a Supreme Court ruling would deny people the right to end pregnancies that happen after rape or incest, or that pose grave medical dangers. These laws are contrary to all relevant science, and any health-related claims used to support them are demonstrably wrong.

In passing these laws, anti-abortion legislators often claim that abortion harms people who are pregnant. In a landmark study from the University of California, San Francisco, scientists found the opposite: d enying people abortions led to worse mental and physical health , as well as financial stability. The Turnaway Study looked at about 1,000 women who were seeking abortions, and followed them for five years. Some were just early enough in their pregnancies that they got the procedure, and others were turned away because their pregnancies were slightly past the legal cutoff where they lived. Women who had abortions reported fewer mental health issues, even years later, and their most common reaction was relief . Women denied abortions often experienced brief declines in mental health and higher anxiety.

Women denied abortions were more likely to end up poor, unemployed or receiving government assistance, even though before they asked for an abortion they were in a similar financial place as women who were able to get one. This study, and others, tell us what will happen in a post- Roe world , when people are forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term because they are denied a most basic form of health care and the ability to make decisions about their own bodies. Access to abortion largely appears to have very positive effects on people’s lives.

The fight against abortion rights is often depicted as a religious mission, but not all religions or religious believers oppose abortion. We note that these political moves are part of a long-standing effort by some conservative Christians, as well as anti-abortion politicians and activists.

By forcing people to have children when they don’t want to, these ideologues strip women of political and earning power, in some cases making them dependent upon men. By forcing people to have children when they are not financially secure, these laws prolong patterns of poverty. And the states with the most restrictive abortion policies often have the worst social safety nets, the worst maternal mortality rates and the greatest health care inequities.

This ideology denies the dangers of pregnancy, despite the fact that in some U.S. states maternal mortality approaches that of some developing nations. Some of the abortion restrictions states have passed are pegged to an early stage of pregnancy. But the biological and genetic problems that lead to complications with pregnancy are too numerous to list, and too variable from person to person to assign a deadline to. Gestational age cutoffs, “heartbeat” laws and total bans go against the basic workings of human biology.

Regardless of how they legally justify their ruling, the justices of the Supreme Court who choose to strike down abortion rights are telling the American public that science doesn’t matter, that evidence can be ignored. High courts have similarly said as much in striking down mask and vaccine mandates during the COVID pandemic. The logic of Alito’s draft—the right to an abortion is not in the Constitution—could apply to all reproductive health, including the Griswold v. Connecticut Supreme Court decision that overturned a law banning birth control. The highest court in the land must value evidence and respect best medical practices, and yet the conservative majority clearly doesn’t.

President Joe Biden and other pro-choice elected officials have said they will work to protect abortion rights. There are legislative means to ensure some degree of abortion access. But with our current federal legislature and the filibuster in place, getting the needed votes to pass measures protecting abortion will be difficult, if not impossible. We hope lawmakers will see abortion rights as an issue that makes it necessary to break through legislative roadblocks.

As our Supreme Court is poised to radically constrain the lives of so many people in the U.S, we applaud those states that are strengthening their abortion protections. We applaud those people who are continuing to fight the legal and practical battles for our right to health care and our right to privacy. And we applaud the health care workers—the doctors, the nurses, the medical assistants—and the volunteers, donors and programs that help people who are pregnant care for themselves and their health. Safe and accessible reproductive health care is a basic right that is supported by science, medicine, and respect for human dignity. Everyone should have access to it.

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Abortion Restrictions and the Threat to Women’s Health

The abortion rights landscape a year after Roe v. Wade was overturned

Annalies Winny

It’s been almost a year since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade , dismantling the constitutional right to abortion more than 50 years after the case was decided.

Now, the legal battleground of reproductive rights has grown even more tense. At least a dozen states have banned abortion entirely, and more states are seeking to further restrict access to abortion—making the U.S. an outlier on the global stage: Some 59% of the world's female population currently reside in a country where abortion is broadly allowed.

“And generally over the past several decades, there has been a trend toward increasing liberalization. So this is part of a very unique change in policy happening in the U.S.,” Suzanne Bell , PhD ’18, MPH, said during a May 18 media briefing .

During the briefing, Bell, an assistant professor in Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Bloomberg School, and Joanne Rosen , JD, MA, a senior lecturer in Health Policy and Management , discussed the state of abortion access in the U.S. and the impact on women’s health—and on physicians—since Roe was overturned. They outlined how abortion restrictions worsen health disparities, how states have responded to Roe’s dismantling, and the potential ramifications of litigation to restrict access to medication abortion for women across the country.

How states have responded

With federal protections for abortion overturned, states were empowered to regulate reproductive health. Rosen noted that some have passed legislation shoring up access to abortion. Fifteen states where abortion remains legal have enacted various additional protections, such as permitting the use of state funds to cover abortion costs; allowing non-physician health professionals to perform abortions; protecting physicians from prosecution, extradition, or other legal action by states that have banned abortion; and prohibiting the disclosure of patients’ medical records without patient permission.

Other states, however, have moved to further erode access, Rosen explained. Even before Dobbs was decided, abortion-hostile states enacted 108 abortion restrictions —in 2021 alone. This is the single highest number of abortion restrictions in any year since Roe was decided in 1973, according to the Guttmacher Institute. In the 11 months since Dobbs was decided, abortion has been banned in 14 states.

Efforts to ban medication abortion nationwide

A Texas case seeking to revoke the FDA’s approval of the safe and effective drug mifepristone—which was used in 53% of abortions in 2020—has “extraordinary” implications that go beyond the possibility of taking mifepristone off the shelves, said Rosen. The litigation also sets a dangerous precedent for court interference in the FDA’s scientific approval process. If the plaintiffs are successful, it “would be the first time a court has abrogated the FDA’s approval of a drug over the objections of the FDA,” Rosen explained. The consequences could be far-reaching, potentially affecting access to any number of drugs for political or ideological reasons.

Other efforts to abolish abortion center on reviving the Comstock Act, an 1873 law banning, among other things, the mailing or transport of products “intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion.” The Comstock Act is one of many “zombie laws”—meaning they’ve long been considered invalid but remain technically on the books—that could see a revival given the precedent set by overturning Roe and invalidating Planned Parenthood v. Casey , the 1992 decision that upheld the right to abortion. Other “zombie laws” in the same legal vein as Comstock, with the same potential for revival, concern same sex marriage and sexual activity and interracial marriage.

Concerns for physicians

The wave of abortion bans have broader implications for the health care workforce.

For one, physicians working in states that ban abortion must contend with “risk management committees” set up by hospitals to determine whether an abortion is warranted in an urgent health care situation where the life of a pregnant person is at risk. “In this context, physicians are finding it difficult to use best medical practices to protect their patients’ well-being”—and they’re concerned about the genuine risk of criminal prosecution, Rosen said.

In this environment, it’s getting harder for hospitals in abortion-hostile states to attract and retain obstetricians and gynecologists, and raising questions about the future of training for these specialties in those states.

“Are they going to entirely leave hostile states and set up their training program elsewhere?” asked Bell. “Or are the people that received training in those states just not going to receive the appropriate training? I think we have yet to see what those full ramifications are.”

Deepening disparities

All of these challenges stand to exacerbate existing disparities in access to quality reproductive health care, Bell added.

Black women are three times as likely, and Hispanic women twice as likely, to seek abortions than white women. And half of all women who get abortions live below the poverty line—many of them in states that limit or are seeking to limit abortions, explained Bell .

Being denied an abortion comes with substantial health risks—especially for vulnerable groups. The risk of maternal death is 15 times higher for carrying a pregnancy to term than it is for abortion, and pregnancy-related complications are 2 to more than 25 times higher for pregnancies ending in birth compared to abortion, Bell explained.

“We have maternal mortality rates that are in some cases twice as high in restrictive states as they are in supportive abortion states,” said Bell—and those restrictions undermine the delivery of basic services, Bell added.

“I want to emphasize that abortion is health care,” Bell said. “Recent state restrictions, coupled with ongoing efforts to curtail access to medication abortion pills nationwide, are an attempt to interfere with the delivery of evidence-based health care and control pregnant people’s bodies, with harmful consequences for individuals and population health.”

Annalies Winny is a producer and writer at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- A Brief History of Abortion in the U.S.

- Mifepristone On Trial: An Unprecedented Overreach (podcast)

- What’s Happening With Abortion Access Six Months After the SCOTUS Decision (podcast)

Related Content

Extreme Heat Hazards

The Problem with Pulse Oximeters: A Long History of Racial Bias

Important Abortion Cases in a Holding Pattern Following SCOTUS Decisions

Abortion Bans and Infant Deaths

We Must Safeguard the Health of Haiti’s Women and Girls

The Most Important Study in the Abortion Debate

Researchers rigorously tested the persistent notion that abortion wounds the women who seek it.

The demographer Diana Greene Foster was in Orlando last month, preparing for the end of Roe v. Wade , when Politico published a leaked draft of a majority Supreme Court opinion striking down the landmark ruling. The opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, would revoke the constitutional right to abortion and thus give states the ability to ban the medical procedure.

Foster, the director of the Bixby Population Sciences Research Unit at UC San Francisco, was at a meeting of abortion providers, seeking their help recruiting people for a new study . And she was racing against time. She wanted to look, she told me, “at the last person served in, say, Nebraska, compared to the first person turned away in Nebraska.” Nearly two dozen red and purple states are expected to enact stringent limits or even bans on abortion as soon as the Supreme Court strikes down Roe v. Wade , as it is poised to do. Foster intends to study women with unwanted pregnancies just before and just after the right to an abortion vanishes.

Read: When a right becomes a privilege

When Alito’s draft surfaced, Foster told me, “I was struck by how little it considered the people who would be affected. The experience of someone who’s pregnant when they do not want to be and what happens to their life is absolutely not considered in that document.” Foster’s earlier work provides detailed insight into what does happen. The landmark Turnaway Study , which she led, is a crystal ball into our post- Roe future and, I would argue, the single most important piece of academic research in American life at this moment.

The legal and political debate about abortion in recent decades has tended to focus more on the rights and experience of embryos and fetuses than the people who gestate them. And some commentators—including ones seated on the Supreme Court—have speculated that termination is not just a cruel convenience, but one that harms women too . Foster and her colleagues rigorously tested that notion. Their research demonstrates that, in general, abortion does not wound women physically, psychologically, or financially. Carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term does.

In a 2007 decision , Gonzales v. Carhart , the Supreme Court upheld a ban on one specific, uncommon abortion procedure. In his majority opinion , Justice Anthony Kennedy ventured a guess about abortion’s effect on women’s lives: “While we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon, it seems unexceptionable to conclude some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained,” he wrote. “Severe depression and loss of esteem can follow.”

Was that really true? Activists insisted so, but social scientists were not sure . Indeed, they were not sure about a lot of things when it came to the effect of the termination of a pregnancy on a person’s life. Many papers compared individuals who had an abortion with people who carried a pregnancy to term. The problem is that those are two different groups of people; to state the obvious, most people seeking an abortion are experiencing an unplanned pregnancy, while a majority of people carrying to term intended to get pregnant.

Foster and her co-authors figured out a way to isolate the impact of abortion itself. Nearly all states bar the procedure after a certain gestational age or after the point that a fetus is considered viable outside the womb . The researchers could compare people who were “turned away” by a provider because they were too far along with people who had an abortion at the same clinics. (They did not include people who ended a pregnancy for medical reasons.) The women who got an abortion would be similar, in terms of demographics and socioeconomics, to those who were turned away; what would separate the two groups was only that some women got to the clinic on time, and some didn’t.

In time, 30 abortion providers—ones that had the latest gestational limit of any clinic within 150 miles, meaning that a person could not easily access an abortion if they were turned away—agreed to work with the researchers. They recruited nearly 1,000 women to be interviewed every six months for five years. The findings were voluminous, resulting in 50 publications and counting. They were also clear. Kennedy’s speculation was wrong: Women, as a general point, do not regret having an abortion at all.

Researchers found, among other things, that women who were denied abortions were more likely to end up living in poverty. They had worse credit scores and, even years later, were more likely to not have enough money for the basics, such as food and gas. They were more likely to be unemployed. They were more likely to go through bankruptcy or eviction. “The two groups were economically the same when they sought an abortion,” Foster told me. “One became poorer.”

Read: The calamity of unwanted motherhood

In addition, those denied a termination were more likely to be with a partner who abused them. They were more likely to end up as a single parent. They had more trouble bonding with their infants, were less likely to agree with the statement “I feel happy when my child laughs or smiles,” and were more likely to say they “feel trapped as a mother.” They experienced more anxiety and had lower self-esteem, though those effects faded in time. They were half as likely to be in a “very good” romantic relationship at two years. They were less likely to have “aspirational” life plans.

Their bodies were different too. The ones denied an abortion were in worse health, experiencing more hypertension and chronic pain. None of the women who had an abortion died from it. This is unsurprising; other research shows that the procedure has extremely low complication rates , as well as no known negative health or fertility effects . Yet in the Turnaway sample, pregnancy ended up killing two of the women who wanted a termination and did not get one.

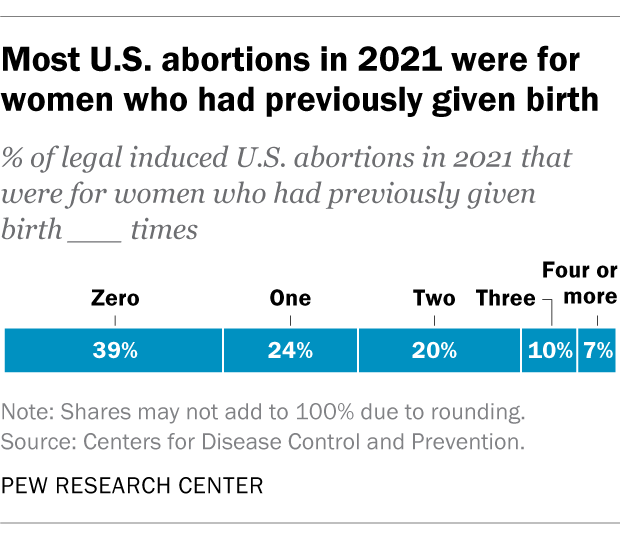

The Turnaway Study also showed that abortion is a choice that women often make in order to take care of their family. Most of the women seeking an abortion were already mothers. In the years after they terminated a pregnancy, their kids were better off; they were more likely to hit their developmental milestones and less likely to live in poverty. Moreover, many women who had an abortion went on to have more children. Those pregnancies were much more likely to be planned, and those kids had better outcomes too.

The interviews made clear that women, far from taking a casual view of abortion, took the decision seriously. Most reported using contraception when they got pregnant, and most of the people who sought an abortion after their state’s limit simply did not realize they were pregnant until it was too late. (Many women have irregular periods, do not experience morning sickness, and do not feel fetal movement until late in the second trimester.) The women gave nuanced, compelling reasons for wanting to end their pregnancies.

Afterward, nearly all said that termination had been the right decision. At five years, only 14 percent felt any sadness about having an abortion; two in three ended up having no or very few emotions about it at all. “Relief” was the most common feeling, and an abiding one.

From the May 2022 issue: The future of abortion in a post- Roe America

The policy impact of the Turnaway research has been significant, even though it was published during a period when states have been restricting abortion access. In 2018, the Iowa Supreme Court struck down a law requiring a 72-hour waiting period between when a person seeks and has an abortion, noting that “the vast majority of abortion patients do not regret the procedure, even years later, and instead feel relief and acceptance”—a Turnaway finding. That same finding was cited by members of Chile’s constitutional court as they allowed for the decriminalization of abortion in certain circumstances.

Yet the research has not swayed many people who advocate for abortion bans, believing that life begins at conception and that the law must prioritize the needs of the fetus. Other activists have argued that Turnaway is methodologically flawed; some women approached in the clinic waiting room declined to participate, and not all participating women completed all interviews . “The women who anticipate and experience the most negative reactions to abortion are the least likely to want to participate in interviews,” the activist David Reardon argued in a 2018 article in a Catholic Medical Association journal.

Still, four dozen papers analyzing the Turnaway Study’s findings have been published in peer-reviewed journals; the research is “the gold standard,” Emily M. Johnston, an Urban Institute health-policy expert who wasn’t involved with the project, told me. In the trajectories of women who received an abortion and those who were denied one, “we can understand the impact of abortion on women’s lives,” Foster told me. “They don’t have to represent all women seeking abortion for the findings to be valid.” And her work has been buttressed by other surveys, showing that women fear the repercussions of unplanned pregnancies for good reason and do not tend to regret having a termination. “Among the women we spoke with, they did not regret either choice,” whether that was having an abortion or carrying to term, Johnston told me. “These women were thinking about their desires for themselves, but also were thinking very thoughtfully about what kind of life they could provide for a child.”

The Turnaway study , for Foster, underscored that nobody needs the government to decide whether they need an abortion. If and when America’s highest court overturns Roe , though, an estimated 34 million women of reproductive age will lose some or all access to the procedure in the state where they live. Some people will travel to an out-of-state clinic to terminate a pregnancy; some will get pills by mail to manage their abortions at home; some will “try and do things that are less safe,” as Foster put it. Many will carry to term: The Guttmacher Institute has estimated that there will be roughly 100,000 fewer legal abortions per year post- Roe . “The question now is who is able to circumvent the law, what that costs, and who suffers from these bans,” Foster told me. “The burden of this will be disproportionately put on people who are least able to support a pregnancy and to support a child.”

Ellen Gruber Garvey: I helped women get abortions in pre- Roe America

Foster said that there is a lot we still do not know about how the end of Roe might alter the course of people’s lives—the topic of her new research. “In the Turnaway Study, people were too late to get an abortion, but they didn’t have to feel like the police were going to knock on their door,” she told me. “Now, if you’re able to find an abortion somewhere and you have a complication, do you get health care? Do you seek health care out if you’re having a miscarriage, or are you too scared? If you’re going to travel across state lines, can you tell your mother or your boss what you’re doing?”

In addition, she said that she was uncertain about the role that abortion funds —local, on-the-ground organizations that help people find, travel to, and pay for terminations—might play. “We really don’t know who is calling these hotlines,” she said. “When people call, what support do they need? What is enough, and who falls through the cracks?” She added that many people are unaware that such services exist, and might have trouble accessing them.

People are resourceful when seeking a termination and resilient when denied an abortion, Foster told me. But looking into the post- Roe future, she predicted, “There’s going to be some widespread and scary consequences just from the fact that we’ve made this common health-care practice against the law.” Foster, to her dismay, is about to have a lot more research to do.

- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2021

Impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes: a systematic review protocol

- Foluso Ishola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8644-0570 1 ,

- U. Vivian Ukah 1 &

- Arijit Nandi 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 192 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

A country’s abortion law is a key component in determining the enabling environment for safe abortion. While restrictive abortion laws still prevail in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many countries have reformed their abortion laws, with the majority of them moving away from an absolute ban. However, the implications of these reforms on women’s access to and use of health services, as well as their health outcomes, is uncertain. First, there are methodological challenges to the evaluation of abortion laws, since these changes are not exogenous. Second, extant evaluations may be limited in terms of their generalizability, given variation in reforms across the abortion legality spectrum and differences in levels of implementation and enforcement cross-nationally. This systematic review aims to address this gap. Our aim is to systematically collect, evaluate, and synthesize empirical research evidence concerning the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs.

We will conduct a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on changes in abortion laws and women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will search Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases, as well as grey literature and reference lists of included studies for further relevant literature. As our goal is to draw inference on the impact of abortion law reforms, we will include quasi-experimental studies examining the impact of change in abortion laws on at least one of our outcomes of interest. We will assess the methodological quality of studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series checklist. Due to anticipated heterogeneity in policy changes, outcomes, and study designs, we will synthesize results through a narrative description.

This review will systematically appraise and synthesize the research evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes in LMICs. We will examine the effect of legislative reforms and investigate the conditions that might contribute to heterogeneous effects, including whether specific groups of women are differentially affected by abortion law reforms. We will discuss gaps and future directions for research. Findings from this review could provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services and scale up accessibility.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019126927

Peer Review reports

An estimated 25·1 million unsafe abortions occur each year, with 97% of these in developing countries [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Despite its frequency, unsafe abortion remains a major global public health challenge [ 4 , 5 ]. According to the World health Organization (WHO), nearly 8% of maternal deaths were attributed to unsafe abortion, with the majority of these occurring in developing countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Approximately 7 million women are admitted to hospitals every year due to complications from unsafe abortion such as hemorrhage, infections, septic shock, uterine and intestinal perforation, and peritonitis [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. These often result in long-term effects such as infertility and chronic reproductive tract infections. The annual cost of treating major complications from unsafe abortion is estimated at US$ 232 million each year in developing countries [ 10 , 11 ]. The negative consequences on children’s health, well-being, and development have also been documented. Unsafe abortion increases risk of poor birth outcomes, neonatal and infant mortality [ 12 , 13 ]. Additionally, women who lack access to safe and legal abortion are often forced to continue with unwanted pregnancies, and may not seek prenatal care [ 14 ], which might increase risks of child morbidity and mortality.

Access to safe abortion services is often limited due to a wide range of barriers. Collectively, these barriers contribute to the staggering number of deaths and disabilities seen annually as a result of unsafe abortion, which are disproportionately felt in developing countries [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. A recent systematic review on the barriers to abortion access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) implicated the following factors: restrictive abortion laws, lack of knowledge about abortion law or locations that provide abortion, high cost of services, judgmental provider attitudes, scarcity of facilities and medical equipment, poor training and shortage of staff, stigma on social and religious grounds, and lack of decision making power [ 17 ].

An important factor regulating access to abortion is abortion law [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Although abortion is a medical procedure, its legal status in many countries has been incorporated in penal codes which specify grounds in which abortion is permitted. These include prohibition in all circumstances, to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, and on request with no requirement for justification [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

Although abortion laws in different countries are usually compared based on the grounds under which legal abortions are allowed, these comparisons rarely take into account components of the legal framework that may have strongly restrictive implications, such as regulation of facilities that are authorized to provide abortions, mandatory waiting periods, reporting requirements in cases of rape, limited choice in terms of the method of abortion, and requirements for third-party authorizations [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. For example, the Zambian Termination of Pregnancy Act permits abortion on socio-economic grounds. It is considered liberal, as it permits legal abortions for more indications than most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; however, abortions must only be provided in registered hospitals, and three medical doctors—one of whom must be a specialist—must provide signatures to allow the procedure to take place [ 22 ]. Given the critical shortage of doctors in Zambia [ 23 ], this is in fact a major restriction that is only captured by a thorough analysis of the conditions under which abortion services are provided.

Additionally, abortion laws may exist outside the penal codes in some countries, where they are supplemented by health legislation and regulations such as public health statutes, reproductive health acts, court decisions, medical ethic codes, practice guidelines, and general health acts [ 18 , 19 , 24 ]. The diversity of regulatory documents may lead to conflicting directives about the grounds under which abortion is lawful [ 19 ]. For example, in Kenya and Uganda, standards and guidelines on the reduction of morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion supported by the constitution was contradictory to the penal code, leaving room for an ambiguous interpretation of the legal environment [ 25 ].

Regulations restricting the range of abortion methods from which women can choose, including medication abortion in particular, may also affect abortion access [ 26 , 27 ]. A literature review contextualizing medication abortion in seven African countries reported that incidence of medication abortion is low despite being a safe, effective, and low-cost abortion method, likely due to legal restrictions on access to the medications [ 27 ].

Over the past two decades, many LMICs have reformed their abortion laws [ 3 , 28 ]. Most have expanded the grounds on which abortion may be performed legally, while very few have restricted access. Countries like Uruguay, South Africa, and Portugal have amended their laws to allow abortion on request in the first trimester of pregnancy [ 29 , 30 ]. Conversely, in Nicaragua, a law to ban all abortion without any exception was introduced in 2006 [ 31 ].

Progressive reforms are expected to lead to improvements in women’s access to safe abortion and health outcomes, including reductions in the death and disabilities that accompany unsafe abortion, and reductions in stigma over the longer term [ 17 , 29 , 32 ]. However, abortion law reforms may yield different outcomes even in countries that experience similar reforms, as the legislative processes that are associated with changing abortion laws take place in highly distinct political, economic, religious, and social contexts [ 28 , 33 ]. This variation may contribute to abortion law reforms having different effects with respect to the health services and outcomes that they are hypothesized to influence [ 17 , 29 ].

Extant empirical literature has examined changes in abortion-related morbidity and mortality, contraceptive usage, fertility, and other health-related outcomes following reforms to abortion laws [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. For example, a study in Mexico reported that a policy that decriminalized and subsidized early-term elective abortion led to substantial reductions in maternal morbidity and that this was particularly strong among vulnerable populations such as young and socioeconomically disadvantaged women [ 38 ].

To the best of our knowledge, however, the growing literature on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health services and outcomes has not been systematically reviewed. A study by Benson et al. evaluated evidence on the impact of abortion policy reforms on maternal death in three countries, Romania, South Africa, and Bangladesh, where reforms were immediately followed by strategies to implement abortion services, scale up accessibility, and establish complementary reproductive and maternal health services [ 39 ]. The three countries highlighted in this paper provided unique insights into implementation and practical application following law reforms, in spite of limited resources. However, the review focused only on a selection of countries that have enacted similar reforms and it is unclear if its conclusions are more widely generalizable.

Accordingly, the primary objective of this review is to summarize studies that have estimated the causal effect of a change in abortion law on women’s health services and outcomes. Additionally, we aim to examine heterogeneity in the impacts of abortion reforms, including variation across specific population sub-groups and contexts (e.g., due to variations in the intensity of enforcement and service delivery). Through this review, we aim to offer a higher-level view of the impact of abortion law reforms in LMICs, beyond what can be gained from any individual study, and to thereby highlight patterns in the evidence across studies, gaps in current research, and to identify promising programs and strategies that could be adapted and applied more broadly to increase access to safe abortion services.

The review protocol has been reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [ 40 ] (Additional file 1 ). It was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database CRD42019126927.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies.

This review will consider quasi-experimental studies which aim to estimate the causal effect of a change in a specific law or reform and an outcome, but in which participants (in this case jurisdictions, whether countries, states/provinces, or smaller units) are not randomly assigned to treatment conditions [ 41 ]. Eligible designs include the following:

Pretest-posttest designs where the outcome is compared before and after the reform, as well as nonequivalent groups designs, such as pretest-posttest design that includes a comparison group, also known as a controlled before and after (CBA) designs.

Interrupted time series (ITS) designs where the trend of an outcome after an abortion law reform is compared to a counterfactual (i.e., trends in the outcome in the post-intervention period had the jurisdiction not enacted the reform) based on the pre-intervention trends and/or a control group [ 42 , 43 ].

Differences-in-differences (DD) designs, which compare the before vs. after change in an outcome in jurisdictions that experienced an abortion law reform to the corresponding change in the places that did not experience such a change, under the assumption of parallel trends [ 44 , 45 ].

Synthetic controls (SC) approaches, which use a weighted combination of control units that did not experience the intervention, selected to match the treated unit in its pre-intervention outcome trend, to proxy the counterfactual scenario [ 46 , 47 ].

Regression discontinuity (RD) designs, which in the case of eligibility for abortion services being determined by the value of a continuous random variable, such as age or income, would compare the distributions of post-intervention outcomes for those just above and below the threshold [ 48 ].

There is heterogeneity in the terminology and definitions used to describe quasi-experimental designs, but we will do our best to categorize studies into the above groups based on their designs, identification strategies, and assumptions.

Our focus is on quasi-experimental research because we are interested in studies evaluating the effect of population-level interventions (i.e., abortion law reform) with a design that permits inference regarding the causal effect of abortion legislation, which is not possible from other types of observational designs such as cross-sectional studies, cohort studies or case-control studies that lack an identification strategy for addressing sources of unmeasured confounding (e.g., secular trends in outcomes). We are not excluding randomized studies such as randomized controlled trials, cluster randomized trials, or stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trials; however, we do not expect to identify any relevant randomized studies given that abortion policy is unlikely to be randomly assigned. Since our objective is to provide a summary of empirical studies reporting primary research, reviews/meta-analyses, qualitative studies, editorials, letters, book reviews, correspondence, and case reports/studies will also be excluded.

Our population of interest includes women of reproductive age (15–49 years) residing in LMICs, as the policy exposure of interest applies primarily to women who have a demand for sexual and reproductive health services including abortion.

Intervention

The intervention in this study refers to a change in abortion law or policy, either from a restrictive policy to a non-restrictive or less restrictive one, or vice versa. This can, for example, include a change from abortion prohibition in all circumstances to abortion permissible in other circumstances, such as to save the woman’s life, to preserve the woman’s health, in cases of rape, incest, fetal impairment, for economic or social reasons, or on request with no requirement for justification. It can also include the abolition of existing abortion policies or the introduction of new policies including those occurring outside the penal code, which also have legal standing, such as:

National constitutions;

Supreme court decisions, as well as higher court decisions;

Customary or religious law, such as interpretations of Muslim law;

Medical ethical codes; and

Regulatory standards and guidelines governing the provision of abortion.

We will also consider national and sub-national reforms, although we anticipate that most reforms will operate at the national level.

The comparison group represents the counterfactual scenario, specifically the level and/or trend of a particular post-intervention outcome in the treated jurisdiction that experienced an abortion law reform had it, counter to the fact, not experienced this specific intervention. Comparison groups will vary depending on the type of quasi-experimental design. These may include outcome trends after abortion reform in the same country, as in the case of an interrupted time series design without a control group, or corresponding trends in countries that did not experience a change in abortion law, as in the case of the difference-in-differences design.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes.

Access to abortion services: There is no consensus on how to measure access but we will use the following indicators, based on the relevant literature [ 49 ]: [ 1 ] the availability of trained staff to provide care, [ 2 ] facilities are geographically accessible such as distance to providers, [ 3 ] essential equipment, supplies and medications, [ 4 ] services provided regardless of woman’s ability to pay, [ 5 ] all aspects of abortion care are explained to women, [ 6 ] whether staff offer respectful care, [ 7 ] if staff work to ensure privacy, [ 8 ] if high-quality, supportive counseling is provided, [ 9 ] if services are offered in a timely manner, and [ 10 ] if women have the opportunity to express concerns, ask questions, and receive answers.

Use of abortion services refers to induced pregnancy termination, including medication abortion and number of women treated for abortion-related complications.

Secondary outcomes

Current use of any method of contraception refers to women of reproductive age currently using any method contraceptive method.

Future use of contraception refers to women of reproductive age who are not currently using contraception but intend to do so in the future.

Demand for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who are currently using, or whose sexual partner is currently using, at least one contraceptive method.

Unmet need for family planning refers to women of reproductive age who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

Fertility rate refers to the average number of children born to women of childbearing age.

Neonatal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death of newborn babies within the first 28 days of life.

Maternal morbidity and mortality refer to disability or death due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth.

There will be no language, date, or year restrictions on studies included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in a low- and middle-income country. We will use the country classification specified in the World Bank Data Catalogue to identify LMICs (Additional file 2 ).

Search methods

We will perform searches for eligible peer-reviewed studies in the following electronic databases.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) (from 1946 to present)

Embase Classic+Embase on OvidSP (from 1947 to present)

CINAHL (1973 to present); and

Web of Science (1900 to present)

The reference list of included studies will be hand searched for additional potentially relevant citations. Additionally, a grey literature search for reports or working papers will be done with the help of Google and Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Search strategy

A search strategy, based on the eligibility criteria and combining subject indexing terms (i.e., MeSH) and free-text search terms in the title and abstract fields, will be developed for each electronic database. The search strategy will combine terms related to the interventions of interest (i.e., abortion law/policy), etiology (i.e., impact/effect), and context (i.e., LMICs) and will be developed with the help of a subject matter librarian. We opted not to specify outcomes in the search strategy in order to maximize the sensitivity of our search. See Additional file 3 for a draft of our search strategy.

Data collection and analysis

Data management.

Search results from all databases will be imported into Endnote reference manager software (Version X9, Clarivate Analytics) where duplicate records will be identified and excluded using a systematic, rigorous, and reproducible method that utilizes a sequential combination of fields including author, year, title, journal, and pages. Rayyan systematic review software will be used to manage records throughout the review [ 50 ].

Selection process

Two review authors will screen titles and abstracts and apply the eligibility criteria to select studies for full-text review. Reference lists of any relevant articles identified will be screened to ensure no primary research studies are missed. Studies in a language different from English will be translated by collaborators who are fluent in the particular language. If no such expertise is identified, we will use Google Translate [ 51 ]. Full text versions of potentially relevant articles will be retrieved and assessed for inclusion based on study eligibility criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or will involve a third reviewer as an arbitrator. The selection of studies, as well as reasons for exclusions of potentially eligible studies, will be described using a PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction

Data extraction will be independently undertaken by two authors. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two authors will meet with the third author to resolve any discrepancies. A piloted standardized extraction form will be used to extract the following information: authors, date of publication, country of study, aim of study, policy reform year, type of policy reform, data source (surveys, medical records), years compared (before and after the reform), comparators (over time or between groups), participant characteristics (age, socioeconomic status), primary and secondary outcomes, evaluation design, methods used for statistical analysis (regression), estimates reported (means, rates, proportion), information to assess risk of bias (sensitivity analyses), sources of funding, and any potential conflicts of interest.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers with content and methodological expertise in methods for policy evaluation will assess the methodological quality of included studies using the quasi-experimental study designs series risk of bias checklist [ 52 ]. This checklist provides a list of criteria for grading the quality of quasi-experimental studies that relate directly to the intrinsic strength of the studies in inferring causality. These include [ 1 ] relevant comparison, [ 2 ] number of times outcome assessments were available, [ 3 ] intervention effect estimated by changes over time for the same or different groups, [ 4 ] control of confounding, [ 5 ] how groups of individuals or clusters were formed (time or location differences), and [ 6 ] assessment of outcome variables. Each of the following domains will be assigned a “yes,” “no,” or “possibly” bias classification. Any discrepancies will be resolved by consensus or a third reviewer with expertise in review methodology if required.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [ 53 ].

Data synthesis

We anticipate that risk of bias and heterogeneity in the studies included may preclude the use of meta-analyses to describe pooled effects. This may necessitate the presentation of our main findings through a narrative description. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles according to the following key headings:

Information on the differential aspects of the abortion policy reforms.

Information on the types of study design used to assess the impact of policy reforms.

Information on main effects of abortion law reforms on primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Information on heterogeneity in the results that might be due to differences in study designs, individual-level characteristics, and contextual factors.

Potential meta-analysis

If outcomes are reported consistently across studies, we will construct forest plots and synthesize effect estimates using meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed using the I 2 test where I 2 values over 50% indicate moderate to high heterogeneity [ 54 ]. If studies are sufficiently homogenous, we will use fixed effects. However, if there is evidence of heterogeneity, a random effects model will be adopted. Summary measures, including risk ratios or differences or prevalence ratios or differences will be calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analysis of subgroups

If there are sufficient numbers of included studies, we will perform sub-group analyses according to type of policy reform, geographical location and type of participant characteristics such as age groups, socioeconomic status, urban/rural status, education, or marital status to examine the evidence for heterogeneous effects of abortion laws.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted if there are major differences in quality of the included articles to explore the influence of risk of bias on effect estimates.

Meta-biases

If available, studies will be compared to protocols and registers to identify potential reporting bias within studies. If appropriate and there are a sufficient number of studies included, funnel plots will be generated to determine potential publication bias.

This systematic review will synthesize current evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms on women’s health. It aims to identify which legislative reforms are effective, for which population sub-groups, and under which conditions.

Potential limitations may include the low quality of included studies as a result of suboptimal study design, invalid assumptions, lack of sensitivity analysis, imprecision of estimates, variability in results, missing data, and poor outcome measurements. Our review may also include a limited number of articles because we opted to focus on evidence from quasi-experimental study design due to the causal nature of the research question under review. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature, provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence and discuss the potential effects of any limitations to our overall conclusions. Protocol amendments will be recorded and dated using the registration for this review on PROSPERO. We will also describe any amendments in our final manuscript.

Synthesizing available evidence on the impact of abortion law reforms represents an important step towards building our knowledge base regarding how abortion law reforms affect women’s health services and health outcomes; we will provide evidence on emerging strategies to influence policy reforms, implement abortion services, and scale up accessibility. This review will be of interest to service providers, policy makers and researchers seeking to improve women’s access to safe abortion around the world.

Abbreviations

Cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature

Excerpta medica database

Low- and middle-income countries

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols

International prospective register of systematic reviews

Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, Johnson BR, Tuncalp O, Assifi A, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010-14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2372–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Guttmacher Institute. Induced Abortion Worldwide; Global Incidence and Trends 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-worldwide . Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Singh S, Remez L, Sedgh G, Kwok L, Onda T. Abortion worldwide 2017: uneven progress and unequal access. NewYork: Guttmacher Institute; 2018.

Book Google Scholar

Fusco CLB. Unsafe abortion: a serious public health issue in a poverty stricken population. Reprod Clim. 2013;2(8):2–9.

Google Scholar

Rehnstrom Loi U, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Faxelid E, Klingberg-Allvin M. Health care providers’ perceptions of and attitudes towards induced abortions in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia: a systematic literature review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1502-2 .

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tuncalp O, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):E323–E33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benson J, Nicholson LA, Gaffikin L, Kinoti SN. Complications of unsafe abortion in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1996;11(2):117–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/11.2.117 .

Abiodun OM, Balogun OR, Adeleke NA, Farinloye EO. Complications of unsafe abortion in South West Nigeria: a review of 96 cases. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2013;42(1):111–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Singh S, Maddow-Zimet I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: a review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG. 2016;123(9):1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13552 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Vlassoff M, Walker D, Shearer J, Newlands D, Singh S. Estimates of health care system costs of unsafe abortion in Africa and Latin America. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35(3):114–21. https://doi.org/10.1363/3511409 .

Singh S, Darroch JE. Adding it up: costs and benefits of contraceptive services. Estimates for 2012. New York: Guttmacher Institute and United Nations Population Fund; 2012.

Auger N, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Sauve R. Abortion and infant mortality on the first day of life. Neonatology. 2016;109(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442279 .

Krieger N, Gruskin S, Singh N, Kiang MV, Chen JT, Waterman PD, et al. Reproductive justice & preventable deaths: state funding, family planning, abortion, and infant mortality, US 1980-2010. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:277–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.007 .

Banaem LM, Majlessi F. A comparative study of low 5-minute Apgar scores (< 8) in newborns of wanted versus unwanted pregnancies in southern Tehran, Iran (2006-2007). J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(12):898–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050802372390 .

Bhandari A. Barriers in access to safe abortion services: perspectives of potential clients from a hilly district of Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:87.

Seid A, Yeneneh H, Sende B, Belete S, Eshete H, Fantahun M, et al. Barriers to access safe abortion services in East Shoa and Arsi Zones of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J Health Dev. 2015;29(1):13–21.

Arroyave FAB, Moreno PA. A systematic bibliographical review: barriers and facilitators for access to legal abortion in low and middle income countries. Open J Prev Med. 2018;8(5):147–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpm.2018.85015 .

Article Google Scholar

Boland R, Katzive L. Developments in laws on induced abortion: 1998-2007. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2008;34(3):110–20. https://doi.org/10.1363/3411008 .

Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S, Johnson BR Jr, Ganatra B. Global Abortion Policies Database: a descriptive analysis of the legal categories of lawful abortion. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0183-1 .

United Nations Population Division. Abortion policies: A global review. Major dimensions of abortion policies. 2002 [Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/abortion/abortion-policies-2002.asp .

Johnson BR, Lavelanet AF, Schlitt S. Global abortion policies database: a new approach to strengthening knowledge on laws, policies, and human rights standards. Bmc Int Health Hum Rights. 2018;18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0174-2 .