In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Table of Contents

What Is Voice in Writing?

- How Do I Find My Writer's Voice?

- How to Develop Your Writer's Voice

Writing Voice: What it Means & How to Find Yours

When you talk to someone, do you have to “find your voice?”

Of course not. You just talk.

Your voice isn’t something you “find.” It’s not hiding between the couch cushions or under the bed. It’s already there, inside of you and a part of you.

So why do so many writers talk about “finding” their voice like it’s a complicated thing?

Because they’re trying to look fancy and sophisticated. The fact is, it isn’t complicated. Elitist writers just want you to think it is.

Every Author has a unique voice, and you don’t have to do anything special to find it.

In this post, I’ll provide a definition of voice and debunk the myth that “finding your voice” is hard. Most importantly, I’ll show you exactly how to do it.

In writing, “voice” is how you speak and think. It’s all about the words you use and the patterns in your writing.

Do you use a lot of rhetorical questions? Long or short sentences? Slang?

Those are all ways your voice might come through in your writing.

Let’s look at a few examples of voice.

Tiffany Haddish is a comedian who grew up in one of the poorest neighborhoods of South Central Los Angeles. She’s made a living off making people laugh, without pulling any punches.

Here’s the opening of her book, The Last Black Unicorn :

When you read this, you can practically hear Tiffany talking. It’s like having a conversation with her. Her voice comes through loud and clear.

She uses humor. She’s candid, and she doesn’t always stick to formal, proper grammar.

Here’s another, very different example.

This is the opening to Can’t Hurt Me by David Goggins, a U.S. Armed Forces icon:

David’s voice is totally different from Tiffany’s. But it still feels like you’re having a conversation with him. It feels authentic.

His tone is more serious, but it’s still friendly. His sentences are short and direct (except for that last sentence, where he uses repetition to make a point). David’s writing is emphatic, and it makes you want to keep reading.

That’s the power of an Author’s voice.

It’s completely and totally theirs.

It’s real.

It’s powerful.

To be clear, your “voice” is different from your writing style .

Your voice is about how you communicate. In any conversation, on any given day, you’re using your natural voice.

Style is about how you approach the reader. It’s either geared toward persuading the reader, explaining something to the reader, telling the reader a story, or describing something to the reader.

No matter what your style is, you’ll have a consistent voice that shines through.

How Do I Find My Writer’s Voice?

You don’t.

People with literature degrees want you to believe that your writer’s voice is something you have to work really hard on. They’ll tell you it’s something you have to develop over time as part of your craft.

That’s not true. Your voice is already part of who you are.

So, if it’s already part of you, why is it hard to find?

It’s not.

Believe it or not, you don’t have to find your Author’s voice. It’s your own voice.

You already have a unique way of speaking/thinking/talking. That’s your writer’s voice. It’s the same thing.

You’re probably just getting in your own way because you’re not used to writing—and because you’ve bought into the belief that writing is “high art.”

It isn’t. Or at least it shouldn’t be.

Writing is about communicating ideas, not showing off.

You communicate every day. Trust yourself, and get out of your own way.

How to Develop Your Writer’s Voice

Your voice is already part of you, but if you’re like most people, you’re probably more comfortable speaking in your voice than writing in it.

If you find yourself in this camp, there are 6 things you can do to get yourself back on track.

To be clear, these aren’t tips for “finding your voice.” They’re tips for remembering you already have one.

1. Stop Trying to Sound Like Someone Else

One of the biggest writing mistakes is when people try to emulate someone else’s writing.

Don’t do this.

I don’t care how great a writer they are or how much you like their book. You’re not them. You’re you.

You have to be yourself because that’s who readers want to engage with. They picked up your book because they thought you could help them solve their problems . If they thought someone else could do it better, they would have bought their book instead.

Give readers what they want: your knowledge, in your words. If you speak to them clearly, honestly, and authentically, you’ll have a strong voice.

Chances are, you like the Authors you like because they stayed true to themselves. They stand out because they’ve let their authentic voice come through in their writing.

There’s nothing authentic about a copycat. And it only takes readers a minute to catch on when someone isn’t being real with them.

If you want to publish a good book , stop trying to live up to other good books. Instead, live up to yourself.

Let your unique point of view come through.

2. Stop Trying to Sound Smart

This is a subset of the first problem, but I’m highlighting it here because it’s something I see all the time .

Authors often try to use fancy words or complicated sentence structure because they think that’s how writing is “supposed” to sound.

Or, they think they have to “sound smart” for readers to perceive them as smart.

I don’t care how smart you are. No one wants to read complicated, dense writing. It doesn’t make you sound smart. It makes you sound unrelatable.

I blame English professors—and textbooks, most of which are horrible.They make people think they have to have some fancy literary voice if they want to be taken seriously.

But be honest. When’s the last time you’ve picked up a book in your spare time and said, “I really want something I have to slog through?”

So don’t make readers slog through your book. They won’t do it.

Complicated words won’t make you sound more authoritative.

Know what will? Good information, delivered clearly and plainly.

Keep your word choice simple and skip the “authorial voice” you think you “should” have.

People appreciate straight shooters more than they appreciate faux-intellectualism or headaches.

3. Stop Worrying About Grammar

The best way to write is the way you talk. And the way you talk won’t always be grammatically correct.

That’s fine.

Stop worrying about grammar, especially when you’re writing your first draft. In reality, grammar rules aren’t rules. They’re suggestions.

Grammar rules are arbitrary conventions that people agree on. Except there is no set of people who are in charge and no formal agreements. That’s why there are so many different grammar books out there.

There are only 2 reasons that grammar even matters in writing:

- It makes communication easier

- People expect good grammar (which is why it makes communication easier)

You want your book to look professional, but more importantly, you want your book to connect with readers.

People respond to people—not rules, and not grammar.

When you write the way you speak, people will connect with it.

Maybe that means using sentence fragments. Like this. Or maybe it means starting a sentence with a conjunction.

Maybe it means being colloquial. Did you notice that Tiffany Haddish said, “I look back over my life and I’m like, ‘For real, that happened?'”

Most grammar books would never encourage you to use “I’m like” as a stand-in for “I said.” But it sounds like Tiffany, and it makes her far more relatable.

Everyone has their own unique way of speaking. You should also embrace your own unique way of writing. It’s okay to break the rules.

Of course, you want your book to look professional, but you can always fix spelling and punctuation mistakes down the line.

Once you’re done writing, hand the manuscript over to a good editor , copyeditor , and/or proofreader . But even then, take their suggestions with a grain of salt.

The most important thing is to preserve your narrative voice and make a connection with the reader.

4. Stop Editing Yourself

I’ll take my earlier advice one step further: don’t just stop worrying about grammar. Stop worrying about how you sound at all.

Just get your ideas down on paper. Your first draft doesn’t have to be perfect. In fact, it won’t be.

Give yourself permission to write a mediocre first draft. Hell, give yourself permission to write a terrible first draft.

I always advise Authors to write what we call a “ vomit draft .” Spew your thoughts onto paper and stop worrying about whether they sound good.

Just get it all out. Get every thought that’s in your head onto the paper.

Like vomiting, it’s not going to be pretty. But it will be real. It will encapsulate your writing voice.

The more you agonize over putting your thoughts on paper, the less natural they’re going to sound. You’ll question your natural flow of thoughts, and you’ll probably edit out all the tics that make your voice sound like you.

Plus, it’s a lot easier to fix a second draft than it is to write a “perfect” first one.

Think of your vomit draft as a starting place that helps you drill down to the essence of your voice.

Here are 2 frames that might help you channel your own voice in the vomit draft:

- Imagine that you’re having a conversation with a friend. It takes the pressure off, guarantees that you’ll be more natural, and ensures that you’re thinking about what the other person is learning and taking in.

- Imagine you’re helping a stranger heal the same pain you had. This helps you focus on actionable advice and helps you stay focused on your reader.

Want to really ace this “writing voice” thing?

Envision yourself helping a friend through something difficult you’ve already figured out.

Why does this work? Because your mind won’t be on your voice at all. It will be focused on helping someone you care about.

Your voice will emerge organically.

5. Write Like You’re Not Finished

I just said that your vomit draft will probably be terrible. But in another sense, your vomit draft will be great .

That’s because it’s exactly what it needs to be: a draft.

Many successful people are perfectionists . They desperately want things to be “right,” and they have high expectations for themselves. When they write, they want every word to be spot-on.

Now, imagine if you put that much pressure on yourself every time you opened your mouth.

What would happen if every word you spoke had to be perfect ?

You’d never say anything.

You can’t have a natural voice—or a voice at all—if you’re hung up on perfectionism.

Every great book starts out as a bad book, or at least a mediocre book. I promise. That’s because writing a book is a long process. You can’t treat it like a one-and-done thing.

A book starts with a rough draft—emphasis on “rough.” Then, over time, it gets better. And better. And better.

I can’t tell you how many Authors I’ve seen who get discouraged at the beginning of the writing process. They let their fear get in the way, and they get stuck. They worry that their books won’t be “good enough” or that people won’t care.

Many of them give up.

It’s important to keep perspective. This is a process. Your voice will develop over successive drafts. It doesn’t have to be perfect right out of the gate.

Ernest Hemingway had one of the most distinctive voices in literature, and he was an obsessive editor. He was never content with his early drafts.

Stop trying to write like you’re writing a finished book. You’re not. You’re writing a draft. When you embrace that and loosen up, your writing voice will sound much more natural.

6. Talk It Out Instead of Writing It Down

An Author’s voice is called a “voice” for a reason. It’s directly related to how a person speaks and communicates.

One thing that makes tapping into your own voice so hard is that it’s hard to type as fast as you speak.

When you’re sitting at a keyboard, your ideas often outpace your ability to get them down. That interrupts your flow and makes the entire writing process feel stilted and awkward.

If you’re having trouble keeping up, stop trying to write. Talk it out instead.

After all, who said you had to write your book? You can speak it just as easily.

I recommend dictating your book and sending the recording to a transcription service .

With roughly 10 hours of talking and a few minutes of file conversion time, you’ll have a workable vomit draft.

Better yet, you’ll have a workable vomit draft in your own voice . Literally.

If you struggle with the idea of dictating that much content, go back to the 2 frames I suggested above. Instead of imagining talking to a friend, actually do it.

Have a conversation with someone else about your book’s subject, and use that conversation as your guide for your rough draft.

We’ve all heard of writer’s block , but there’s no such thing as speaker’s block. There’s a good reason for that.

It’s easy to talk to a friend. You don’t worry about sounding smart or needing to find your voice. You just speak, and your voice emerges naturally.

Don’t make writing a book more complicated than it has to be. When in doubt, let your actual voice do the “writing” for you.

The Scribe Crew

Read this next.

Authors Receive Authority – What does ‘The Medium Is the Message’ Really Mean?

Audiobooks: Who Benefits Most and Why Authors Should Consider Them

When Should You Hire a Ghostwriter for a Business Book?

Critical writing: Your voice

- Managing your reading

- Source reliability

- Critical reading

- Descriptive vs critical

- Deciding your position

- The overall argument

- Individual arguments

- Signposting

- Alternative viewpoints

- Critical thinking videos

Jump to content on this page:

“When academics write articles... they not only present their own ideas but also refer to the ideas of other academics. This means that they need a way to distinguish between their own ideas and the ideas of other people. They need to express their own voice and to refer to the voices of others.” Brick et al. (2019), Academic Success

Academic writing can feel incredibly disempowering. Students often feel they spend all of their time writing about the work of others, without ever demonstrating what they know or think. This is not the case. While all academic arguments must be based on appropriate evidence (references), you decide what evidence to include. You also decide how to critique or support every source you include. This is how your voice comes through in academic writing.

A critical aspect of higher education is the development of knowledge through debate and discourse. Good academic writing uses a mixture of the voices. In practical terms, this includes a blend of your voice and the voice of others . Whenever you are using the work of someone else, this must be appropriately cited and referenced. Referencing is an important part of voice as it helps to distinguish between your ideas and the ideas of others .

The four different voices of academic writing

There are four different types of voice that are used within academic writing:

- Own voice : An original point or claim written by the author of this work, or an aspect of analysis, synthesis or evaluation that comments on the work of others.

- External voice : The writer summarises or paraphrases the work of someone else. Their name is not mentioned directly in the text and the relevant source is represented through citation.

- Indirect voice: The writer summarises or paraphrases the work of someone else. Their name is mentioned in text and the source is appropriated cited.

- Direct voice: The writer directly quotes the work of someone else. Their direct words are reproduced, their name is mentioned in text and the source is appropriated cited.

Example: Using different voices

Let's look at a sample piece of level 5 writing to look at some of the different types of voice:

Public concern for food safety steadily grew from the 1970's onwards as food poisoning events increased. As these public concerns rose, the term ‘food scare’ started to appear in the media (Knowles et al, 2007). According to Campbell and Fitzgerald (2001), food scares were first associated with the malicious lacing of tablets with cyanide in mid-1980s USA, but once coined, soon became applied to the varied food safety issues that arose over subsequent years. Through this the media began to start portraying uncertainty over food safety, which has led to a wide variety of public responses. This is because "no unequivocal evidence is available for determining the role of socio-demographic characteristics in processing food safety information" (Mazzocchi et al., 2008:3). This means...

(Excerpt from: Fallin, 2009)

In this short except, all four types of voice are used.

The use of different voices is an essential aspect of the above excerpt's developing academic argument. As important as the evidence is, this must be articulated in the context of the argument - in this case, demonstrating public concern for food poisoning events. For this reason, the author's own voice is used as part of the argument and narrative.

Writer's own voice

The writer opens with a sentence to introduce their point. There is no need to reference this opening point as it will be argued within the paragraph - with the use of appropriate academic evidence.

Public concern for food safety steadily grew from the 1970's onwards as food poisoning events increased.

External voice

The writer then uses the external voice . This is because the author has fully summerised the work of Knowles, which is referenced using an in-text citation in Harvard/APA style. Knowles name is not mentioned in the main narrative of the text, but is appropriately cited in brackets.

As these public concerns rose, the term ‘food scare’ started to appear in the media (Knowles et al, 2007).

Indirect voice

The writer's next sentence uses the indirect voice . This is because they mention Campell and Fitzgernald by name, but go on to user their own words to summerise the work of these authors. Campell and Fitzgernald are appropriates cited to indicate the origin of this idea.

According to Campbell and Fitzgerald (2001), food scared were first associated with the malicious lacing of tablets with cyanide in mid-1980s USA, but once coined, soon became applied to the varied food safety issues that arose over subsequent years.

The writer has then again, used their voice to synthesis the evidence so far - and link to their next point. There is no need to reference this as it is build upon the above evidence.

Through this the media began to start portraying uncertainty over food safety, which has led to a wide variety of public responses.

Direct voice

The writer then goes on to use the direct voice . This is because they directly quote the work of Mazzocchi et al., using the authors exact words. This is represented by the quotation marks and is appropriately referenced.

This is because "no unequivocal evidence is available for determining the role of socio-demographic characteristics in processing food safety information" (Mazzocchi et al., 2008:3).

Activity: Identifying different voices

As you have seen from this page so far, the use of different academic voices is an essential aspect of both academic integrity (citations/referencing) and critical thinking (building an argument). As your writing develops, so will your use of voice. However, it is also important to be able to identify these voices in your reading. This will support you in identifying the argument of others - and the sources of evidence for them.

For this activity we will look at a piece of level 7 work and try to identify the different use of voice. Read the text below, and try to identify the different use of academic voice. Once you've finished your analysis, look at the next tab for the answers.

- Sample text

- Sample text + analysis

(Excerpt from: Fallin, 2015)

Voice, discipline and level

You will find different disciplines use voice in different ways. This is something you will identify the more you engage with the literature in your field. Your assessments are also an opportunity to develop this, and you will recieve feedback/feedforward from your lecturers and tutors to help you develop your writing in your field.

There is a great variation in how disciplines may approach voice, but here are some general overviews.

- Sciences favour external voice and own voice above that of indirect and direct voice. In fact, it is very rare you will find the direct voice in scientific writing. Sciences tend to focus on the re-articulation of core information and knowledge in the context of the current work. There is also less of a focus over who is involved in the work, so the use of the indirect voice is also rare. This is because citations are used to identify authorship, and this is not needed in the narrative.

- Social sciences will often use a mix of all voices, though the balance will depend on the work in question. While the external and own voice are the staple, there is a greater appreciation for theory and authorship, so the indirect voice is also common. There is still a focus on avoiding the use of direct voice (quotations) wherever possible, but they are appreciated where the context requires them.

- Arts and humanities also used a mix of all voices. There is a greater allowance for the direct voice, especially when quoting original or historical work for the purpose of analysis - but not as a means of padding out work. There must be synthesis and analysis for any use of the direct voice.

Level of study

It is also fair to say that your use of voice will vary heavily by level of study. For example, level 4 study generally focuses on acquiring core disciplinary knowledge. At this phase of your studies, your own voice is still developing, and you may find your use of the external, indirect and direct voice is greater. This inevitably rebalances at higher levels of study. By level 6 and 7 you should have really developed your own voice as a way to synthesis and narrate the ideas of others (presented in the other three voices).

- << Previous: Signposting

- Next: Alternative viewpoints >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/criticalwriting

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Writing Center

- Academic Essays

- Approaching Writing

- Sentence-level Writing

- Write for Student-Run Media

- Writing in the Core

- Access Smartthinking

- TutorTrac Appointments

- SMART Space

Your Writing “Voice”

What Is Voice in an Academic Essay or Some Other Type of Composition?

Voice has at least two distinct meanings:

- The audible sound of a person speaking (e.g., high-pitched, rhythmic, loud, soft, accent, pace). Even in writing, the author’s words create the “sound” of the writer talking. Effective writers can control the sound of their words in their readers’ heads.

- The communicator’s implied beliefs and values. Every utterance conveys the impression of a person behind the words—a “self” that may be authentic or constructed as a persona. This “self” can extend beyond an implied personality to include the communicator’s political, philosophical, and social values as well as his or her commitment to certain causes (civil rights, gay rights, women’s rights).

Elements of Voice

Because audiences experience a communicator’s voice as a whole expression, not a set of parts, a reconsideration of some commonly understood elements of voice may be useful.

- Tone. Tone is the communicator’s attitude toward the subject and audience as expressed in a text. For example, are you trying to convey anger, joy, sarcasm, contempt, anxiety, or respect? To gain control of your tone, read drafts aloud and listen to the attitudes you convey. Is the tone consistent throughout the text? Should it be? Have you struck the tone that you were hoping to strike?

- Style. Style is the distinctive way you express yourself. It can change from day to day but it is always you. The style that you choose for a particular writing assignment will largely depend on your subject, purpose, and audience. Style in writing is affected by such values as the level of formality/informality appropriate to the situation and by the simplicity or complexity of words, sentences, and paragraphs. To gain control of style, learn to analyze the purpose and audience. Decide how you want to present yourself and ensure that it suits the occasion.

- Values. Values include your political, social, religious, and philosophical beliefs. Your background, opinions, and beliefs will be part of everything you write, but you must learn when to express them directly and when not to. For example, including your values would enhance a personal essay or other autobiographical writing, but it might undermine a sense of objectivity in an interpretive or research paper. To gain control of the values in your writing, consider whether the purpose of the assignment calls for implicit or explicit value statements. Examine your drafts for opinion and judgment words that reveal your values and take them out if they are not appropriate.

- Authority. Authority comes from knowledge and is projected through self-confidence. You can exert and project real authority only if you know your material well, whether it’s the facts of your life or carefully researched material. The better you know your subject (and this is often learned through drafting), the more authoritative you will sound. Your audience will hear that authority in your words.

What Is Voice in an Academic Essay?

Many students arrive at college with the notion that they must not use the first-person “I” point of view when writing an academic essay . The personal voice, so goes the reasoning, undermines the student writer’s authority by making the analysis or argument or whatever the student is writing seem too subjective or opinionated to be academic. The student who subscribes to this notion is correct—or possibly incorrect; it depends on how the assignment has been designed. One advantage of not using the first-person “I” is that it challenges the student to present ideas as objective claims, which will amplify the degree to which the claims require support to be convincing. Notice the different effects of these two claims:

I feel that Pablo Picasso’s reputation as a great artist conflicts with what his biographers have to say about his personal relationships, especially with women.

Pablo Picasso’s reputation as a great artist conflicts with what his biographers have to say about his personal relationships, especially with women.

The only measurable difference between the two sentences above is that the first of them is couched in the first-person phrase “I feel.” The two sentences differ more consequentially in terms of effect, however. The writer—and readers—of the second sentence are probably going to sense more strongly the need for support to make the claim convincing. That’s a good thing, for it indicates to the writer the work that needs to be done to make the claim convincing.

The disadvantage of keeping the first-person “I” voice out of an essay is that it may squelch something unique and authentic about the writer’s voice and vision, turning the essay into something more formal in tone—something more conventionally academic, let’s say. What is more, while denying the first-person “I” a place in an academic essay may heighten awareness of an essay’s argumentative weaknesses, it also participates in a tradition that privileges certain modes of thought and expression. The traditional ways of approaching academic essays, instructors are coming to accept, may be too limiting for today’s students.

So, is the first-person “I” correct or incorrect? Ask your instructor this question before you begin writing your academic essay . Talk about what you need, in terms of voice, to convey your ideas most effectively.

Quick tip about citing sources in MLA style

What’s a thesis, sample mla essays.

- Student Life

- Career Success

- Champlain College Online

- About Champlain College

- Centers of Experience

- Media Inquiries

- Contact Champlain

- Maps & Directions

- Consumer Information

- Generating Ideas

- Drafting and Revision

- Sources and Evidence

- Style and Grammar

- Specific to Creative Arts

- Specific to Humanities

- Specific to Sciences

- Specific to Social Sciences

- CVs, Résumés and Cover Letters

- Graduate School Applications

- Other Resources

- Hiatt Career Center

- University Writing Center

- Classroom Materials

- Course and Assignment Design

- UWP Instructor Resources

- Writing Intensive Requirement

- Criteria and Learning Goals

- Course Application for Instructors

- What to Know about UWS

- Teaching Resources for WI

- FAQ for Instructors

- FAQ for Students

- Journals on Writing Research and Pedagogy

- University Writing Program

- Degree Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Brandeis Online

- Summer Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Financial Aid

- Summer School

- Centers and Institutes

- Funding Resources

- Housing/Community Living

- Clubs and Organizations

- Community Service

- Brandeis Arts Engagement

- Rose Art Museum

- Our Jewish Roots

- Mission and Diversity Statements

- Administration

- Faculty & Staff

- Alumni & Friends

- Parents & Families

- 75th Anniversary

- Campus Calendar

- Directories

- New Students

- Shuttle Schedules

- Support at Brandeis

Writing Resources

Voice and analysis in your essay, the tour guide approach.

This handout is available for download in DOCX format and PDF format .

Several people have asked me what I mean when I ask for more VOICE in your essay. This is a great question, and it gets to the heart of what analysis looks like in a research paper. The goal of a research paper is to use the literature (your research) to support your own unique argument. This is different from a literature review, which simply reviews what others have said about a topic. In a research paper, there is some literature review, typically towards the beginning, but the larger goal is to DO SOMETHING with this literature to show your own take on the topic . This is analysis and it is what gives voice to your essay. One way to think about voice is to see yourself as the TOUR GUIDE of your essay.

Imagine a tour of a city. The guide's job is to take people from place to place, showing them things that make the city special. A mediocre guide might just say, "This is Westminster Abbey," "This is Big Ben," etc. They might provide facts, such as who is buried at Westminster Abbey, but they don't put any of the information in context. You might as well do a self-guided tour. This is the equivalent of a literature review: you describe all of the studies and theories, but you don't tell the reader what to do with this new knowledge. The EVIDENCE is there, but the ANALYSIS is missing.

On the other hand, a good tour guide doesn't just show you the buildings. Instead, they tell you about how these monuments reflect the history and culture of the city. They put the buildings into context to tell a story and give you a sense of place, time, purpose, etc. This is the equivalent of a good research paper. It takes evidence (data, observations, theories) and does something with it to communicate a new angle to your reader. It argues something, using the literature as a foundation on which to build the new, original argument.

Good tour guides (writers) insert their voice often. The voice can be heard in topic sentences , where the writer tells the reader how the paragraph fits into the larger argument (i.e., how it connects to the thesis). The voice can be heard in the analysis in the paragraphs as the writer tells the reader what has been learned and what it means for the larger argument. The voice often gets stronger as the essay progresses—especially since earlier paragraphs often contain more background information and later paragraphs are more likely to contain argument built on that background information. A good tour guide also:

- Doesn't tell the reader things they already know

- Doesn't over-explain or provide unnecessary detail

- Doesn't rush— if they move too fast, their tour won't be able to keep up

- Keeps things interesting (doesn't visit boring sites!)

- Keeps things organized (no backtracking to sites they've already visited)

How to use this in your writing:

Analysis is any moment in which you tell the reader your interpretation, how ideas fit together, why something matters, etc. It is when your voice comes through, as opposed to the authors of the articles you cite.

What might analysis / tour guiding look like in a research essay?

- Critique of the literature (methodological flaws, different interpretations of findings, etc.)

- Resolution of contradictory evidence

- Analysis of differing theories (in light of the evidence)

- Incorporation of various lenses, e.g., cultural or societal influences, cross-cultural similarities or differences, etc.

- Historical changes

- Fusion of literature or topics that are not obviously related

- Transitional language that connects pieces of the argument

Credit: Elissa Jacobs, University Writing Program

- Resources for Students

- Writing Intensive Instructor Resources

- Research and Pedagogy

The Writer's Voice in Literature and Rhetoric

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In rhetoric and literary studies, voice is the distinctive style or manner of expression of an author or narrator . As discussed below, voice is one of the most elusive yet important qualities in a piece of writing .

"Voice is usually the key element in effective writing," says teacher and journalist Donald Murray. "It is what attracts the reader and communicates to the reader. It is that element that gives the illusion of speech ." Murray continues: "Voice carries the writer's intensity and glues together the information that the reader needs to know. It is the music in writing that makes the meaning clear" ( Expecting the Unexpected: Teaching Myself--and Others--to Read and Write , 1989).

Etymology From the Latin, "call"

Quotes on Writer's Voice

Don Fry: Voice is the sum of all strategies used by the author to create the illusion that the writer is speaking directly to the reader from the page.

Ben Yagoda: Voice is the most popular metaphor for writing style, but an equally suggestive one may be delivery or presentation, as it includes body language, facial expression, stance, and other qualities that set speakers apart from one another.

Mary McCarthy: If one means by style the voice , the irreducible and always recognizable and alive thing, then of course style is really everything.

Peter Elbow: I think voice is one of the main forces that draws us into texts . We often give other explanations for what we like ('clarity,' 'style,' 'energy,' 'sublimity,' 'reach,' even 'truth'), but I think it's often one sort of voice or another. One way of saying this is that voice seems to overcome ' writing ' or textuality . That is, speech seems to come to us as listener; the speaker seems to do the work of getting the meaning into our heads. In the case of writing, on the other hand, it's as though we as reader have [to] go to the text and do the work of extracting the meaning. And speech seems to give us more sense of contact with the author.

Walker Gibson: The personality I am expressing in this written sentence is not the same as the one I orally express to my three-year-old who at this moment is bent on climbing onto my typewriter. For each of these two situations, I choose a different ' voice ,' a different mask, in order to accomplish what I want accomplished.

Lisa Ede: Just as you dress differently on different occasions, as a writer you assume different voices in different situations. If you're writing an essay about a personal experience, you may work hard to create a strong personal voice in your essay. . . . If you're writing a report or essay exam, you will adopt a more formal, public tone. Whatever the situation, the choice you make as you write and revise . . . will determine how readers interpret and respond to your presence.

Robert P. Yagelski: If voice is the writer's personality that a reader 'hears' in a text, then tone might be described as the writer's attitude in a text. The tone of a text might be emotional (angry, enthusiastic, melancholy), measured (such as in an essay in which the author wants to seem reasonable on a controversial topic), or objective or neutral (as in a scientific report). . . . In writing, tone is created through word choice, sentence structure, imagery, and similar devices that convey to a reader the writer's attitude. Voice, in writing, by contrast, is like the sound of your spoken voice: deep, high-pitched, nasal. It is the quality that makes your voice distinctly your own, no matter what tone you might take. In some ways, tone and voice overlap, but voice is a more fundamental characteristic of a writer, whereas tone changes upon the subject and the writer's feelings about it.

Mary Ehrenworth and Vicki Vinton: If, as we believe, grammar is linked to voice, students need to be thinking about grammar far earlier in the writing process . We cannot teach grammar in lasting ways if we teach it as a way to fix students' writing, especially writing they view as already complete. Students need to construct knowledge of grammar by practicing it as part of what it means to write, particularly in how it helps create a voice that engages the reader on the page.

Louis Menand: One of the most mysterious of writing’s immaterial properties is what people call ' voice .' . . . Prose can show many virtues, including originality, without having a voice. It may avoid cliché , radiate conviction, be grammatically so clean that your grandmother could eat off it. But none of this has anything to do with this elusive entity the 'voice.' There are probably all kinds of literary sins that prevent a piece of writing from having a voice, but there seems to be no guaranteed technique for creating one. Grammatical correctness doesn’t insure it. Calculated incorrectness doesn’t, either. Ingenuity, wit, sarcasm , euphony, frequent outbreaks of the first-person singular—any of these can enliven prose without giving it a voice.

- The Essay: History and Definition

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- Stylistics and Elements of Style in Literature

- What Is Tone In Writing?

- Imitation in Rhetoric and Composition

- Definition of Audience

- Mood in Composition and Literature

- Writers on Writing: The Art of Paragraphing

- First-Person Point of View

- What is an Implied Author?

- Definition and Examples of Narratives in Writing

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- Characteristics of a Formal Prose Style

- Third-Person Point of View

- Definition and Examples of Explication (Analysis)

Definition of Voice

Types of voice, examples of voice in literature, example #1: various works (by multiple authors).

Stream of Consciousness is a narrative voice that comprises the thought processes of the characters. James Joyce ’s novel , Ulysses , and William Faulkner ’s novels, As I Lay Dying , and The Sound and Fury , are modes of stream of consciousness narrative.

Example #2: To Kill a Mockingbird (By Harper Lee)

Example #3: the tell-tale heart (by edgar allan poe).

Edgar Allan Poe ’s short story The Tell-Tale Heart is an example of first‑person unreliable narrative voice, which is significantly unknowledgeable, biased, childish, and ignorant, which purposefully tries to deceive the readers. As the story proceeds, readers notice the voice is unusual, characterized by starts and stops. The character directly talks to the readers, showing a highly exaggerated and wrought style. It is obvious that the effectiveness of this story relies on its style, voice, and structure, which reveal the diseased state of mind of the narrator.

Example #4: Frankenstein (By Mary Shelley)

Example #5: old man and the sea (by george r. r. martin).

Third person narrative voice employs a third‑person point of view. In a third‑person subjective voice, a narrator describes feelings, thoughts, and opinions of one or more characters. Hemingway’s novel Old Man and the Sea , and George R. R. Martin’s fantasy novel A Song of Ice and Fire, present examples of third person subjective voice.

Example #6: Hills Like White Elephants (By Ernest Hemingway)

Function of voice, related posts:, post navigation.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Develop a Voice

I. What is Voice?

In literature, the voice expresses the narrator or author’s emotions, attitude, tone and point of view through artful, well thought out use of word choice and diction. A voice may be formal or informal; serious or lighthearted; positive or negative; persuasive or argumentative; comical or depressed; witty or straightforward; objective or subjective—truly, voice can reflect any and all feelings and perspectives. A work’s voice directly contributes to its tone and mood; helping the writer create the desired effect he wants his words to have on readers.

A piece of literature’s voice is one of its most defining and important features and can completely change the way a story is read and received. For example, you could tell the same story in two ways; on version through a very positive narrator, and the other through a very negative narrator, and the results would be very, very different. Likewise, you could have two different authors or narrators addressing the same subject—the voice will vary depending on their feelings about that subject, which will in turn affect the way it is presented.

Last, it’s important to distinguish between literary voice as described above, and the sound of someone’s physical voice. The sound of someone’s voice is just a physical characteristic, whereas a literary voice is a part of writing and storytelling.

II. Examples of Voice

Here are some examples of greetings from different voices:

- Good day, m’lady

- Good day, madame

- Greetings, sir

- What’s up, dude?

- Hello there

- ‘Ello gov’na

- G’day, mate

Each greeting has the same basic meaning but is expressed in a completely different voice. Several factors contribute to each voice—for example, some are formal while some are informal; some show an accent; some use slang; and some even use different languages.

Now, read these two sentences:

The sun is a glorious glowing orb of golden heat and light, giving life to everything it touches. *** The sun is a flaming ball of fire and blinding light, burning anything that’s under its rays for too long.

The voice of the first sentence is pleasant and appreciative, expressing that the sun is a wonderful thing. The second’s voice carries the opposite attitude; expressing that the sun is harsh and damaging. The two distinct voices can influence how we perceive the sun.

III. Types of Voice

Voice is determined by either the person telling the story (the narrator) or the person writing the story (the author), and can be further defined by the voices of characters in a story. Basically, it’s important to remember that a work’s voice is not always reflective of the author’s own opinions or attitudes.

a. Narrator’s voice

The narrator’s voice expresses the attitude of the person who is actually directly telling us the story. It is partially determined by the narrator’s role in the story ( narrative style)—whether the narrator is part of the story or telling it from an outside perspective obviously affects his attitude and the way he’ll express himself. For instance, a first person narrator (a character in the story narrating from their point of view, using I, me and we ) may be more invested in what happens than a third objective person narrator (a narrator who is not a character in the story and doesn’t have a stake in what’s happening). But from whatever point of view, the narrator is the one who readers hear the story from, and so his voice is what influences the entire way readers experience the work.

b. Author’s voice

The author’s voice directly reflects the attitude of the author himself. Even when a work has a narrator, an author’s voice can certainly come through. That said, an author’s voice tends to be most prominent in nonfiction, where a writer is often directly expressing his own knowledge and opinion. News sources provide great examples of authors’ voices—though the news should really be neutral, it often clearly shows the voice of the network or the writer. For instance, many would say that Fox News has a conservative voice and that CBS has a more liberal voice.

c. Character Voices

An author may also choose to show the voices of characters in addition to the voice of a third person narrator, or the narrator may be a character within the story. So, with this technique, readers are able to understand the attitudes of those who are direct part of the story. Sometimes, an author may tell a story from the perspectives of several characters, using multiple voices that approach the same events with different attitudes.

IV. Importance of Voice

As mentioned above, the voice is an essential part of the way a story or piece of writing is delivered. Works of literature need voices to help them stand out in style and deliver stories and content in the most effective way possible.

V. Examples of Voice in Literature

In Susanna Kaysen’s memoir Girl, Interrupted we get to experience a story from a very unique perspective—that of the author, who is actually writing about her time as a patient in psychiatric hospital. The voice of the story is unique in that it reflects the author’s attitude about the events, but the author is also the real-life protagonist of the story. Here, Susanna recounts her appointment with a psychiatrist:

“You need a rest,” he announced. I did need a rest, particularly since I’d gotten up so early that morning in order to see this doctor, who lived out in the suburbs. I’d changed trains twice. And I would have to retrace my steps to get to my job. Just thinking of it made me tired. “Don’t you think?” He was still standing in front of me. “Don’t you think you need a rest?”

Here, Susanna’s voice is almost misleading to the audience—in fact, she is expressing that she thinks she needs a rest because she had a long morning. But knowing it is a psychiatrist asking her, we know that Susanna is having psychological issues, and that the rest he speaks of is actually a rest in a psychiatric facility.

One of the kookiest voices in literature comes from Dr. Seuss, known for his unruly rhyme patterns, made up words and overall silly voice. In his beloved classic The Cat in the Hat, Doctor Seuss tells his story with three voices—the children, the fish, and the Cat in the Hat. Here are two stanzas , one showing the fish’s voice, one showing the Cat’s:

our fish said, ‘no! no! make that cat go away! tell that cat in the hat you do NOT want to play. he should not be here. he should not be about. he should not be here when your mother is out!’ ‘now! now! have no fear. have no fear!’ said the cat. ‘my tricks are not bad,’ said the cat in the hat. ‘why, we can have lots of good fun, if you wish, with a game that i call up-up-up with a fish!’

On top of the author’s overall whimsical voice, we get to hear from two of the characters, who though speaking to the same issue, are very different and express opposite attitudes. The first voice is that of the fish, who is stern and serious, warning the children that they should not play with the Cat; the second is that of the Cat; lighthearted and dismissive, telling everyone not to worry and that they should definitely play with him. Dr Seuss uses these two distinct voices to help show the difficult situation the kids are in—one voice says play, the other says don’t!

VI. Examples in Pop Culture

In the 2015 film Room , a mother and her five year old child are prisoners inside their captor’s shed. Ma, the mother, has been there for seven years, while Jack, her son, has never left ‘Room’—Ma has taught Jack that Room is the whole world, and there’s nothing outside of it. Throughout the film, we get to hear some of Jack’s explanations about life in Room:

Here, you can see Ma depressed in bed while hearing Jack speak about room. His voice (his literary voice, not the literal sound of his voice) reflects his surprisingly positive perspective on the world. Through Jack’s commentary we understand how Ma has been able to endure this terrible situation—Jack doesn’t know any other home, and sees the best in Room. Jack sees the good in the things where we might see problems, like a bent spoon and a toilet in the centre of a home. His innocent voice is what makes the film slightly less painful.

George R.R. Martin is well known for storytelling through multiple characters and voices in his novels, and the same goes when he adapts the stories for the TV series Game of Thrones. Voice can be harder to express on screen, but Game of Thrones still finds a way to replicate what Martin does on the page. For instance, this clip shows us the voices of several groups of characters during a tragic event:

Through different perspectives during these infamous events of the Red Wedding, we experience the voice of vengeance from Lord Frey (who leads the massacre), the voice of desperation from the Starks as they are killed one by one (the current victims), the voices of arrogance from the knights who kill the wolf, and the voice of hopelessness from Arya (who sees what’s happening from the outside), and the voice of reason from the Hound (who takes Arya away).

VII. Conclusion

In the end, it’s always important to think about the voice of your writing. It determines so much of how a story works, from the way it is told to how the reader understands and feels about the characters and events. The voice is what determines a work’s mood and tone, and ultimately what distinguishes one story or piece of writing from the next!

VIII. Related Terms

A narrator is the person telling the story. In literature, the voice is not the narrator himself, but rather every narrator has a voice.

The mood of a story is the overall feeling that it gives off to its readers. A story’s voice helps contribute to its mood.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice

Style is the way in which something is written, as opposed to the meaning of what is written. In writing, however, the two are very closely linked. As the package for the meaning of the text, style influences the reader’s impression of the information itself. Style includes diction and tone. The main goal in considering style is to present your information in a manner appropriate for both the audience and the purpose of the writing. Consistency is vital. Switching styles can distract the reader and diminish the believability of the paper’s argument.

Diction is word choice. When writing, use vocabulary suited for the type of assignment. Words that have almost the same denotation (dictionary meaning) can have very different connotations (implied meanings).

| are not angry | aren't mad | ain't ticked |

Besides the level of formality, also consider positive or negative connotations of the words chosen.

| pruning the bushes | slashing at the bushes |

| the politician's stance | the politician's spin |

Some types of diction are almost never advisable in writing. Avoid clichés, vagueness (language that has more than one equally probable meaning), wordiness, and unnecessarily complex language.

Aside from individual word choice, the overall tone, or attitude, of a piece of writing should be appropriate to the audience and purpose. The tone may be objective or subjective, logical or emotional, intimate or distant, serious or humorous. It can consist mostly of long, intricate sentences, of short, simple ones, or of something in between. (Good writers frequently vary the length of their sentences.)

One way to achieve proper tone is to imagine a situation in which to say the words being written. A journal might be like a conversation with a close friend where there is the freedom to use slang or other casual forms of speech. A column for a newspaper may be more like a high-school graduation speech: it can be more formal, but it can still be funny or familiar. An academic paper is like a formal speech at a conference: being interesting is desirable, but there is no room for personal digressions or familiar usage of slang words.

In all of these cases, there is some freedom of self-expression while adapting to the audience. In the same way, writing should change to suit the occasion.

Tone vs. Voice

Anything you write should still have your voice: something that makes your writing sound uniquely like you. A personal conversation with a friend differs from a speech given to a large group of strangers. Just as you speak to different people in different ways yet remain yourself, so the tone of your writing can vary with the situation while the voice -- the essential, individual thoughts and expression -- is still your own.

“Don’t play what’s there; play what’s not there.” - Miles Davis “The notes I handle no better than many pianists. But the pauses between the notes—ah, that is where the art resides.” - Artur Schnabel (1882–1951), German-born U.S. pianist.

These two musicians expressed the same thought in their own unique voices.

Reference: Strunk, William Jr., and E. B. White. The Elements of Style . 4th ed., Allyn and Bacon, 2000.

Copyright © 2009 Wheaton College Writing Center

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

Thinking strategies and writing patterns, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

While reading, have you ever felt as though an author was talking to you inside your head? Perhaps you felt this sensation while reading a social media post, an article, or even a book. Writers achieve the feeling of someone talking to you through style, voice, and tone. Mastering these will help your readers know how to feel about your writing and help you communicate in a way that is unique to you.

- APPLICATION

In popular usage, the word “style” means a vague sense of personal style, or personality. Applied to writing, “style” does have this connotation—especially in fiction. However, style in writing has a more formal and unique meaning, too. Applied to writing, “style” is a technical term for word patterns that create a certain effect on readers.

If a piece of writing reflects a consistent choice of patterns, then it feels coherent and harmonious. This coherence and harmony can be quite pleasing for readers, and writers aspire to it. However, writers do not always choose a style. Rather, context, content, and purpose dictate the style a writer should use.

For example:

Genre will dictate a fiction writer’s style. Specific academic disciplines will dictate style for an academic writer. Both genre and discipline have stylistic conventions that writers take into account when creating a written work. When writing, pay close attention to the genre and discipline in which you are writing.

When writers speak of style in a more personal sense, they often use the word “voice.” When you hear an author talking inside your head, “voice” is what that author sounds like.

Of all the writerly qualities, voice is the most difficult to analyze and describe. Most writers have difficulty expressing what their voice is and how they achieved it, though most will allow their voice developed over time and after much practice. Still, there are qualities that, when identified and practiced, can help you develop your own voice.

Look closely at professional writing, and you may notice a certain rhythm or cadence to it. This rhythm is an element of voice.

Read a number of works from the same author, and you may notice common word choices, perhaps not the same words, but similar words or word patterns. Word choice (also called “diction”) is an element of voice.

Punctuation

You may also notice that some authors come across as flamboyant while others come across as blunt or assertive. Still others may come across as always second-guessing themselves, adding qualifications and asides to their statements. An author often achieves these qualities through carefully placed punctuation, another element of voice.

To assert your own personal writing style, practice rhythm and cadence, pay careful attention to word choice and develop an understanding of how punctuation can be used to express ideas.

Even when indulging their own voices, authors must keep in mind context, content, and purpose. To do this, they make adjustments to their voices using “tone.”

Tone is the attitude conveyed by an author’s voice. We use two general distinctions when discussing tone: informal and formal.

An Informal Tone

Ever read something, and your heart swells with pride? Or maybe you get angry, or you get scared. Write informally, and you’ll use emotions - big ones. You’ll use contractions, too. A lot of times, when you write informally, you talk about yourself and use the first-person pronoun (I). Sometimes you talk to the reader and use the second-person pronoun (you). An informal tone sounds conversational and familiar like you do when you talk with a friend.

A Formal Tone

When using a formal tone, authors avoid discussion about themselves. They use the third-person perspective. They do not use contractions, and they emphasize reason and logic. Though an author might appeal to an emotion, the emotional appeal would be subtler and more nuanced. Most of all, however, a formal tone suggests politeness and respect.

Key Takeaways

- When writing, mirror your style after the genre you are writing for.

- You can develop your own voice in your writing by paying special attention to rhythm, diction, and punctuation.

- Use an informal tone for creative writing, personal narratives, and personal essays.

- Use a formal tone for most essays, research papers, reports, and business writing

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Why is ‘voice’ important in academic writing?

This is the first of three chapter about Balancing Voices . To complete this reader, read each chapter carefully and then unlock and complete our materials to check your understanding.

– Introduce the concept of ‘voice’ in academic writing

– Discuss the importance of balancing author voices

– Provide examples of source voice and writer voice in context

Chapter 1: Why is ‘voice’ important in academic writing?

Chapter 2: What are the three different types of ‘voice’?

Chapter 3: How can I effectively balance ‘voice’ in my writing?

Of the many writing skills that exist, students often struggle most with the concept of voice in academic writing – yet creating a balance of voice is perhaps one of the most important aspects of this style. The following three chapters therefore attempt to deal firstly with the concept of voice and why it’s used in academic writing before exploring how to use and identify the three different types of voice. Finally, how to effectively include and balance voice in your own writing is discussed in some detail.

What is ‘voice’?

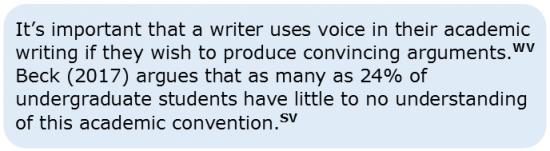

Although how voice is identified in academic writing varies slightly from institution to institution, the general concept of voice is mostly agreed upon. Put simply, voice when writing academically describes whether the information in a text has been provided by the writer or by another source author, and such voice may be analysed on a clause-by-clause or sentence-by-sentence basis. Writer voice is therefore used to indicate and introduce the opinions and ideas of the writer, while source voice may be used to introduce evidence, concepts or ideas from a published piece of research – otherwise known as a source . The following two example sentences show how both writer voice ( WV ) and source voice ( SV ) may be used together:

Why is ‘voice’ important?

There are three primary reasons that the distinction between writer voice and source voice should be clearly indicated in a piece of academic writing.

1. Including Sources

Sources that provide support for the writer’s arguments and ideas are a critical aspect of academic writing. By using integral citations , the writer can introduce various sources in their writing in the form of source voice . Such sources may be introduced to define a concept , support an argument , provide explanations and examples, or to provide the direct words of an author through quotations .

2. Writing Convincing Arguments

Source voice is most often used by academics to introduce sources that will make that writer’s research more convincing. Particularly at the undergraduate level, a reader (or marking tutor) will likely care little for the ideas and opinions of an inexperienced and unpublished researcher; instead, by supporting those ideas with appropriate sources, the writer is able to make their arguments more convincing. If a reader sees that the writer’s ideas are supported by external evidence and agreement, then those ideas will be stronger and more difficult to refute.

3. Separating Opinions

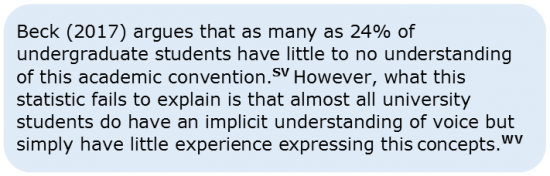

The final reason that voice is important is that it helps the writer to separate their opinions from the opinions of other authors. Perhaps the writer wishes to introduce a counter argument in an evaluative essay and intends to show that they don’t necessarily agree with the included source’s research or ideas. To do this, the writer might use clear source voice , indicating that the evidence they’ve provided may or may not be separate from the writer’s own opinion. Consider the following example:

It’s clear from the second sentence in this example that the writer ( WV ) disagrees with Beck’s (2017) argument ( SV ). The use of clear source voice and writer voice has therefore enabled the writer to separate their opinions from the opinions of another author. However, as will be shown in Chapter 2, there are in fact three types of voice that a writer may use to their advantage. Continue reading to find out more about the third and final type: mixed voice .

Downloadables

Once you’ve completed all three chapters about voice , you might also wish to download our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets to test your progress or print for your students. These professional PDF worksheets can be easily accessed for only a few Academic Marks .

Our voice academic reader (including all three chapters about this topic) can be accessed here at the click of a button.

Gain unlimited access to our voice beginner worksheet, with activities and answer keys designed to check a basic understanding of this reader’s chapters.

To check a confident understanding of this reader’s chapters, click on the button below to download our voice intermediate worksheet with activities and answer keys.

Our voice advanced worksheet with activities and answer keys has been created to check a sophisticated understanding of this reader’s chapters.

To save yourself 3 Marks , click on the button below to gain unlimited access to all of our voice guidance and worksheets. The All-in-1 Pack includes every chapter on this topic, as well as our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets in one handy PDF.

Click on the button below to gain unlimited access to our voice teacher’s PowerPoint, which should include everything you’d need to successfully introduce this topic.

Collect Academic Marks

- 100 Marks for joining

- 25 Marks for daily e-learning

- 100-200 for feedback/testimonials

- 100-500 for referring your colleages/friends

- How It Works

- Prices & Discounts

Active Voice vs Passive Voice in Essay Writing: What's the Difference?

Table of contents

Every type of writing, spanning academic assignments, research proposals, movie or book reviews, newspaper articles, technical or scientific writing, and more, requires a verb in the sentence to express an action being taken.

Essentially, we know that there are two types of voices in writing – active voice vs. passive voice. Both voices have a different sentence structure, length, purpose, and tone of writing.

Now when you analyze your writing, you would be able to find specific sentences that pop out and leave a mark on the reader while some sentences remain bland and unengaging.

This will determine your active voice sentences and your passive voice sentences.

You think to yourself, “how do I choose the right voice for my writing?”

What is Active Voice in Essay Writing

In a sentence, the active voice is used when the subject or person in this specific sentence is the one who is carrying out an action that was represented by the verb. The subject is always a noun or a pronoun and this voice is used to express information in a stronger, more direct, clear, and easier-to-read way than passive voice sentences.

Active voice highlights a logical flow to your sentences and makes your writing feel alive and current – which is pivotal to use in your formal academic writing assignments to get top-scoring grades.

What is Passive Voice in Essay Writing

The passive voice, in a sentence, is used to emphasize the action taken place by the subject according to the verb. In this, the passive phrase always contains a conjugated form of ‘to be’ and the past participle of the main verb.

Due to this, passive sentences also include prepositions, which makes them longer and wordier than active voice sentences.

Active Voice vs. Passive Voice

Now, let us understand the difference between active voice vs. passive voice in writing.

The choice between using active voice vs. passive voice in writing always comes down to the requirements that are suitable for the type of sentences you choose to write.

For most of the writing that you do, be it blogs, emails, different types of academic essays, and more, an active voice is ideal to use for communicating and expressing your thoughts, facts, and ideas more clearly and efficiently. This way, your essay papers or other academic assessments stand out amongst the rest.

Use your judgment to write in an active voice if accuracy is not an important aspect, and always keep your readers in mind. In this case, academic writing teachers - ranging from middle school to college/universities, prefer reading your assignments in an active voice as it makes your arguments, thoughts, and sentence structures confident, brief, and compelling.

However, there are a few exceptions to using passive voice

- If the reader is aware of the subject;

- In expository writing (where the primary goal is to provide an explanation or a context);

- Crime reports, data analysis;

- Scientific and technical writing.

Passive voice is majorly used while writing assignments that direct the reader's focus onto the specific action taking place rather than the subject. It is also used when you need an authoritative tone, like on a banner or a sign on a bulletin board.

Passive voice is ideally used when the person involved in the action is not known and/or is insignificant. Similarly, if you are writing something that requires you to be objective with its solution and analysis – like a research paper, lab report , or newspaper article – using passive voice should be your go-to choice. This allows you to avoid personal pronouns, which in turn, helps you present your analysis or information in an unbiased and coherent way.

However, if your writing is meant to engage your target audience, such as a novel, then writing your sentences with a passive voice will not only flatten your content and make your writing clumsy to read, but your paper would also inherit all the extra words that would make your write-ups vague and too wordy.

2. Examples of active and passive voice