Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

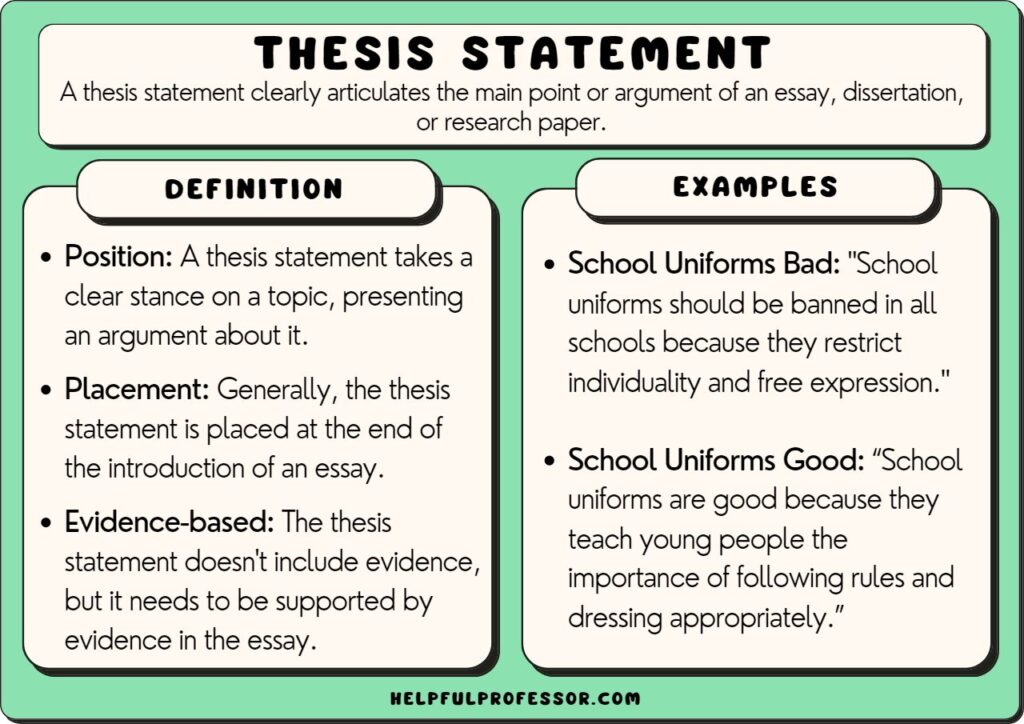

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

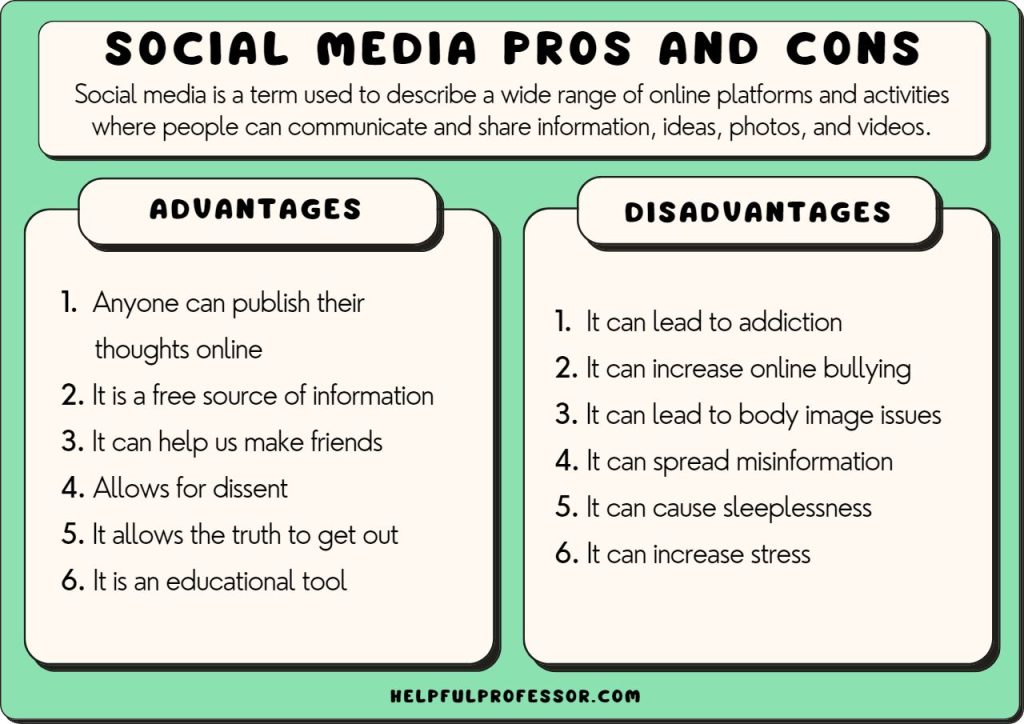

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Identifying Thesis Statements, Claims, and Evidence

Thesis statements, claims, and evidence, introduction.

The three important parts of an argumentative essay are:

- A thesis statement is a sentence, usually in the first paragraph of an article, that expresses the article’s main point. It is not a fact; it’s a statement that you could disagree with. Therefore, the author has to convince you that the statement is correct.

- Claims are statements that support the thesis statement, but like the thesis statement, are not facts. Because a claim is not a fact, it requires supporting evidence.

- Evidence is factual information that shows a claim is true. Usually, writers have to conduct their own research to find evidence that supports their ideas. The evidence may include statistical (numerical) information, the opinions of experts, studies, personal experience, scholarly articles, or reports.

Each paragraph in the article is numbered at the beginning of the first sentence.

Paragraphs 1-7

Identifying the Thesis Statement. Paragraph 2 ends with this thesis statement: “People’s prior convictions should not be held against them in their pursuit of higher learning.” It is a thesis statement for three reasons:

- It is the article’s main argument.

- It is not a fact. Someone could think that peoples’ prior convictions should affect their access to higher education.

- It requires evidence to show that it is true.

Finding Claims. A claim is statement that supports a thesis statement. Like a thesis, it is not a fact so it needs to be supported by evidence.

You have already identified the article’s thesis statement: “People’s prior convictions should not be held against them in their pursuit of higher learning.”

Like the thesis, a claim be an idea that the author believes to be true, but others may not agree. For this reason, a claim needs support.

- Question 1. Can you find a claim in paragraph 3? Look for a statement that might be true, but needs to be supported by evidence.

Finding Evidence.

Paragraphs 5-7 offer one type of evidence to support the claim you identified in the last question. Reread paragraphs 5-7.

- Question 2. Which word best describes the kind of evidence included in those paragraphs: A report, a study, personal experience of the author, statistics, or the opinion of an expert?

Paragraphs 8-10

Finding Claims

Paragraph 8 makes two claims:

- “The United States needs to have more of this transformative power of education.”

- “The country [the United States] incarcerates more people and at a higher rate than any other nation in the world.”

Finding Evidence

Paragraphs 8 and 9 include these statistics as evidence:

- “The U.S. accounts for less than 5 percent of the world population but nearly 25 percent of the incarcerated population around the globe.”

- “Roughly 2.2 million people in the United States are essentially locked away in cages. About 1 in 5 of those people are locked up for drug offenses.”

Question 3. Does this evidence support claim 1 from paragraph 8 (about the transformative power of education) or claim 2 (about the U.S.’s high incarceration rate)?

Question 4. Which word best describes this kind of evidence: A report, a study, personal experience of the author, statistics, or the opinion of an expert?

Paragraphs 11-13

Remember that in paragraph 2, Andrisse writes that:

- “People’s prior convictions should not be held against them in their pursuit of higher learning.” (Thesis statement)

- “More must be done to remove the various barriers that exist between formerly incarcerated individuals such as myself and higher education.” (Claim)

Now, review paragraphs 11-13 (Early life of crime). In these paragraphs, Andrisse shares more of his personal story.

Question 5. Do you think his personal story is evidence for statement 1 above, statement 2, both, or neither one?

Question 6. Is yes, which one(s)?

Question 7. Do you think his personal story is good evidence? Does it persuade you to agree with him?

Paragraphs 14-16

Listed below are some claims that Andrisse makes in paragraph 14. Below each claim, please write the supporting evidence from paragraphs 15 and 16. If you can’t find any evidence, write “none.”

Claim: The more education a person has, the higher their income.

Claim: Similarly, the more education a person has, the less likely they are to return to prison.

Paragraphs 17-19

Evaluating Evidence

In these paragraphs, Andrisse returns to his personal story. He explains how his father’s illness inspired him to become a doctor and shares that he was accepted to only one of six biomedical graduate programs.

Do you think that this part of Andrisse’s story serves as evidence (support) for any claims that you’ve identified so far? Or does it support his general thesis that “people’s prior convictions should not be held against them in pursuit of higher learning?” Please explain your answer.

Paragraphs 20-23

Andrisse uses his personal experience to repeat a claim he makes in paragraph 3, that “more must be done to remove the various barriers that exist between formerly incarcerated individuals such as myself and higher education.”

To support this statement, he has to show that barriers exist. One barrier he identifies is the cost of college. He then explains the advantages of offering Pell grants to incarcerated people.

What evidence in paragraphs 21-23 support his claim about the success of Pell grants?

Paragraphs 24-28 (Remove questions about drug crimes from federal aid forms)

In this section, Andrisse argues that federal aid forms should not ask students about prior drug convictions. To support that claim, he includes a statistic about students who had to answer a similar question on their college application.

What statistic does he include?

In paragraph 25, he assumes that if a question about drug convictions discourages students from applying to college, it will probably also discourage them from applying for federal aid.

What do you think about this assumption? Do you think it’s reasonable or do you think Andrisse needs stronger evidence to show that federal aid forms should not ask students about prior drug convictions?

Supporting English Language Learners in First-Year College Composition Copyright © by Breana Bayraktar is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.1 Developing a Strong, Clear Thesis Statement

Learning objectives.

- Develop a strong, clear thesis statement with the proper elements.

- Revise your thesis statement.

Have you ever known a person who was not very good at telling stories? You probably had trouble following his train of thought as he jumped around from point to point, either being too brief in places that needed further explanation or providing too many details on a meaningless element. Maybe he told the end of the story first, then moved to the beginning and later added details to the middle. His ideas were probably scattered, and the story did not flow very well. When the story was over, you probably had many questions.

Just as a personal anecdote can be a disorganized mess, an essay can fall into the same trap of being out of order and confusing. That is why writers need a thesis statement to provide a specific focus for their essay and to organize what they are about to discuss in the body.

Just like a topic sentence summarizes a single paragraph, the thesis statement summarizes an entire essay. It tells the reader the point you want to make in your essay, while the essay itself supports that point. It is like a signpost that signals the essay’s destination. You should form your thesis before you begin to organize an essay, but you may find that it needs revision as the essay develops.

Elements of a Thesis Statement

For every essay you write, you must focus on a central idea. This idea stems from a topic you have chosen or been assigned or from a question your teacher has asked. It is not enough merely to discuss a general topic or simply answer a question with a yes or no. You have to form a specific opinion, and then articulate that into a controlling idea —the main idea upon which you build your thesis.

Remember that a thesis is not the topic itself, but rather your interpretation of the question or subject. For whatever topic your professor gives you, you must ask yourself, “What do I want to say about it?” Asking and then answering this question is vital to forming a thesis that is precise, forceful and confident.

A thesis is one sentence long and appears toward the end of your introduction. It is specific and focuses on one to three points of a single idea—points that are able to be demonstrated in the body. It forecasts the content of the essay and suggests how you will organize your information. Remember that a thesis statement does not summarize an issue but rather dissects it.

A Strong Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement contains the following qualities.

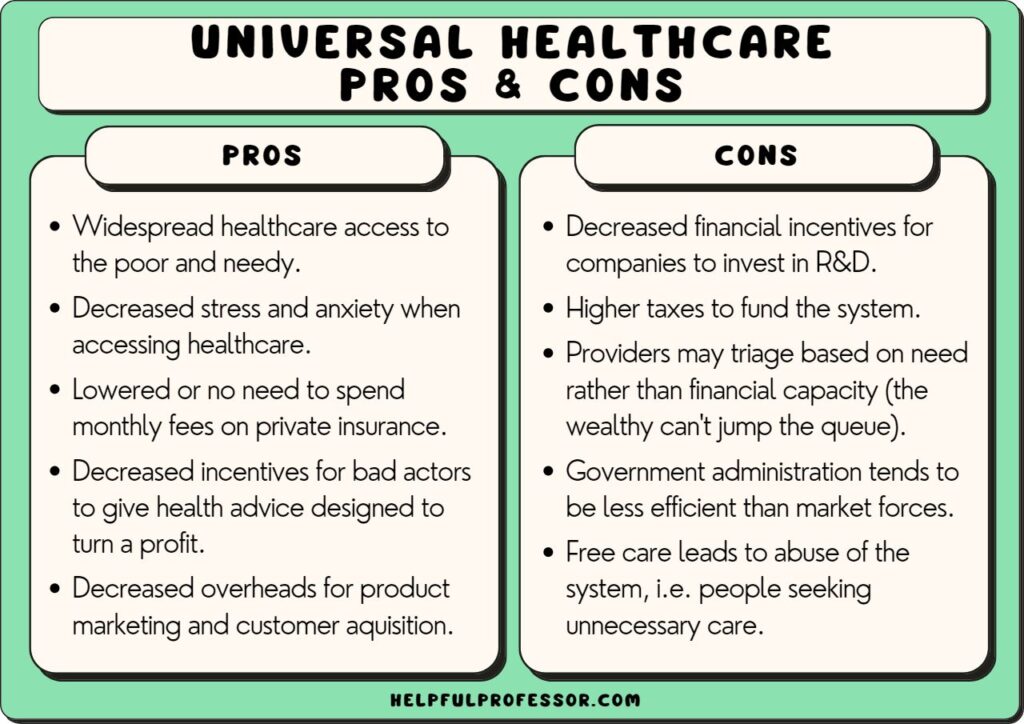

Specificity. A thesis statement must concentrate on a specific area of a general topic. As you may recall, the creation of a thesis statement begins when you choose a broad subject and then narrow down its parts until you pinpoint a specific aspect of that topic. For example, health care is a broad topic, but a proper thesis statement would focus on a specific area of that topic, such as options for individuals without health care coverage.

Precision. A strong thesis statement must be precise enough to allow for a coherent argument and to remain focused on the topic. If the specific topic is options for individuals without health care coverage, then your precise thesis statement must make an exact claim about it, such as that limited options exist for those who are uninsured by their employers. You must further pinpoint what you are going to discuss regarding these limited effects, such as whom they affect and what the cause is.

Ability to be argued. A thesis statement must present a relevant and specific argument. A factual statement often is not considered arguable. Be sure your thesis statement contains a point of view that can be supported with evidence.

Ability to be demonstrated. For any claim you make in your thesis, you must be able to provide reasons and examples for your opinion. You can rely on personal observations in order to do this, or you can consult outside sources to demonstrate that what you assert is valid. A worthy argument is backed by examples and details.

Forcefulness. A thesis statement that is forceful shows readers that you are, in fact, making an argument. The tone is assertive and takes a stance that others might oppose.

Confidence. In addition to using force in your thesis statement, you must also use confidence in your claim. Phrases such as I feel or I believe actually weaken the readers’ sense of your confidence because these phrases imply that you are the only person who feels the way you do. In other words, your stance has insufficient backing. Taking an authoritative stance on the matter persuades your readers to have faith in your argument and open their minds to what you have to say.

Even in a personal essay that allows the use of first person, your thesis should not contain phrases such as in my opinion or I believe . These statements reduce your credibility and weaken your argument. Your opinion is more convincing when you use a firm attitude.

On a separate sheet of paper, write a thesis statement for each of the following topics. Remember to make each statement specific, precise, demonstrable, forceful and confident.

- Texting while driving

- The legal drinking age in the United States

- Steroid use among professional athletes

Examples of Appropriate Thesis Statements

Each of the following thesis statements meets several of the following requirements:

- Specificity

- Ability to be argued

- Ability to be demonstrated

- Forcefulness

- The societal and personal struggles of Troy Maxon in the play Fences symbolize the challenge of black males who lived through segregation and integration in the United States.

- Closing all American borders for a period of five years is one solution that will tackle illegal immigration.

- Shakespeare’s use of dramatic irony in Romeo and Juliet spoils the outcome for the audience and weakens the plot.

- J. D. Salinger’s character in Catcher in the Rye , Holden Caulfield, is a confused rebel who voices his disgust with phonies, yet in an effort to protect himself, he acts like a phony on many occasions.

- Compared to an absolute divorce, no-fault divorce is less expensive, promotes fairer settlements, and reflects a more realistic view of the causes for marital breakdown.

- Exposing children from an early age to the dangers of drug abuse is a sure method of preventing future drug addicts.

- In today’s crumbling job market, a high school diploma is not significant enough education to land a stable, lucrative job.

You can find thesis statements in many places, such as in the news; in the opinions of friends, coworkers or teachers; and even in songs you hear on the radio. Become aware of thesis statements in everyday life by paying attention to people’s opinions and their reasons for those opinions. Pay attention to your own everyday thesis statements as well, as these can become material for future essays.

Now that you have read about the contents of a good thesis statement and have seen examples, take a look at the pitfalls to avoid when composing your own thesis:

A thesis is weak when it is simply a declaration of your subject or a description of what you will discuss in your essay.

Weak thesis statement: My paper will explain why imagination is more important than knowledge.

A thesis is weak when it makes an unreasonable or outrageous claim or insults the opposing side.

Weak thesis statement: Religious radicals across America are trying to legislate their Puritanical beliefs by banning required high school books.

A thesis is weak when it contains an obvious fact or something that no one can disagree with or provides a dead end.

Weak thesis statement: Advertising companies use sex to sell their products.

A thesis is weak when the statement is too broad.

Weak thesis statement: The life of Abraham Lincoln was long and challenging.

Read the following thesis statements. On a separate piece of paper, identify each as weak or strong. For those that are weak, list the reasons why. Then revise the weak statements so that they conform to the requirements of a strong thesis.

- The subject of this paper is my experience with ferrets as pets.

- The government must expand its funding for research on renewable energy resources in order to prepare for the impending end of oil.

- Edgar Allan Poe was a poet who lived in Baltimore during the nineteenth century.

- In this essay, I will give you lots of reasons why slot machines should not be legalized in Baltimore.

- Despite his promises during his campaign, President Kennedy took few executive measures to support civil rights legislation.

- Because many children’s toys have potential safety hazards that could lead to injury, it is clear that not all children’s toys are safe.

- My experience with young children has taught me that I want to be a disciplinary parent because I believe that a child without discipline can be a parent’s worst nightmare.

Writing at Work

Often in your career, you will need to ask your boss for something through an e-mail. Just as a thesis statement organizes an essay, it can also organize your e-mail request. While your e-mail will be shorter than an essay, using a thesis statement in your first paragraph quickly lets your boss know what you are asking for, why it is necessary, and what the benefits are. In short body paragraphs, you can provide the essential information needed to expand upon your request.

Thesis Statement Revision

Your thesis will probably change as you write, so you will need to modify it to reflect exactly what you have discussed in your essay. Remember from Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” that your thesis statement begins as a working thesis statement , an indefinite statement that you make about your topic early in the writing process for the purpose of planning and guiding your writing.

Working thesis statements often become stronger as you gather information and form new opinions and reasons for those opinions. Revision helps you strengthen your thesis so that it matches what you have expressed in the body of the paper.

The best way to revise your thesis statement is to ask questions about it and then examine the answers to those questions. By challenging your own ideas and forming definite reasons for those ideas, you grow closer to a more precise point of view, which you can then incorporate into your thesis statement.

Ways to Revise Your Thesis

You can cut down on irrelevant aspects and revise your thesis by taking the following steps:

1. Pinpoint and replace all nonspecific words, such as people , everything , society , or life , with more precise words in order to reduce any vagueness.

Working thesis: Young people have to work hard to succeed in life.

Revised thesis: Recent college graduates must have discipline and persistence in order to find and maintain a stable job in which they can use and be appreciated for their talents.

The revised thesis makes a more specific statement about success and what it means to work hard. The original includes too broad a range of people and does not define exactly what success entails. By replacing those general words like people and work hard , the writer can better focus his or her research and gain more direction in his or her writing.

2. Clarify ideas that need explanation by asking yourself questions that narrow your thesis.

Working thesis: The welfare system is a joke.

Revised thesis: The welfare system keeps a socioeconomic class from gaining employment by alluring members of that class with unearned income, instead of programs to improve their education and skill sets.

A joke means many things to many people. Readers bring all sorts of backgrounds and perspectives to the reading process and would need clarification for a word so vague. This expression may also be too informal for the selected audience. By asking questions, the writer can devise a more precise and appropriate explanation for joke . The writer should ask himself or herself questions similar to the 5WH questions. (See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information on the 5WH questions.) By incorporating the answers to these questions into a thesis statement, the writer more accurately defines his or her stance, which will better guide the writing of the essay.

3. Replace any linking verbs with action verbs. Linking verbs are forms of the verb to be , a verb that simply states that a situation exists.

Working thesis: Kansas City schoolteachers are not paid enough.

Revised thesis: The Kansas City legislature cannot afford to pay its educators, resulting in job cuts and resignations in a district that sorely needs highly qualified and dedicated teachers.

The linking verb in this working thesis statement is the word are . Linking verbs often make thesis statements weak because they do not express action. Rather, they connect words and phrases to the second half of the sentence. Readers might wonder, “Why are they not paid enough?” But this statement does not compel them to ask many more questions. The writer should ask himself or herself questions in order to replace the linking verb with an action verb, thus forming a stronger thesis statement, one that takes a more definitive stance on the issue:

- Who is not paying the teachers enough?

- What is considered “enough”?

- What is the problem?

- What are the results

4. Omit any general claims that are hard to support.

Working thesis: Today’s teenage girls are too sexualized.

Revised thesis: Teenage girls who are captivated by the sexual images on MTV are conditioned to believe that a woman’s worth depends on her sensuality, a feeling that harms their self-esteem and behavior.

It is true that some young women in today’s society are more sexualized than in the past, but that is not true for all girls. Many girls have strict parents, dress appropriately, and do not engage in sexual activity while in middle school and high school. The writer of this thesis should ask the following questions:

- Which teenage girls?

- What constitutes “too” sexualized?

- Why are they behaving that way?

- Where does this behavior show up?

- What are the repercussions?

In the first section of Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , you determined your purpose for writing and your audience. You then completed a freewriting exercise about an event you recently experienced and chose a general topic to write about. Using that general topic, you then narrowed it down by answering the 5WH questions. After you answered these questions, you chose one of the three methods of prewriting and gathered possible supporting points for your working thesis statement.

Now, on a separate sheet of paper, write down your working thesis statement. Identify any weaknesses in this sentence and revise the statement to reflect the elements of a strong thesis statement. Make sure it is specific, precise, arguable, demonstrable, forceful, and confident.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

In your career you may have to write a project proposal that focuses on a particular problem in your company, such as reinforcing the tardiness policy. The proposal would aim to fix the problem; using a thesis statement would clearly state the boundaries of the problem and tell the goals of the project. After writing the proposal, you may find that the thesis needs revision to reflect exactly what is expressed in the body. Using the techniques from this chapter would apply to revising that thesis.

Key Takeaways

- Proper essays require a thesis statement to provide a specific focus and suggest how the essay will be organized.

- A thesis statement is your interpretation of the subject, not the topic itself.

- A strong thesis is specific, precise, forceful, confident, and is able to be demonstrated.

- A strong thesis challenges readers with a point of view that can be debated and can be supported with evidence.

- A weak thesis is simply a declaration of your topic or contains an obvious fact that cannot be argued.

- Depending on your topic, it may or may not be appropriate to use first person point of view.

- Revise your thesis by ensuring all words are specific, all ideas are exact, and all verbs express action.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Thesis Statements

Thesis statements establish for your readers both the relationship between the ideas and the order in which the material will be presented. As the writer, you can use the thesis statement as a guide in developing a coherent argument. In the thesis statement you are not simply describing or recapitulating the material; you are taking a specific position that you need to defend . A well-written thesis is a tool for both the writer and reader, reminding the writer of the direction of the text and acting as a "road sign" that lets the reader know what to expect.

A thesis statement has two purposes: (1) to educate a group of people (the audience) on a subject within the chosen topic, and (2) to inspire further reactions and spur conversation. Thesis statements are not written in stone. As you research and explore your subject matter, you are bound to find new or differing points of views, and your response may change. You identify the audience, and your thesis speaks to that particular audience.

Preparing to Write Your Thesis: Narrowing Your Topic

Before writing your thesis statement, you should work to narrow your topic. Focus statements will help you stay on track as you delve into research and explore your topic.

- I am researching ________to better understand ________.

- My paper hopes to uncover ________about ________.

- How does ________relate to ________?

- How does ________work?

- Why is ________ happening?

- What is missing from the ________ debate?

- What is missing from the current understanding of ________?

Other questions to consider:

- How do I state the assigned topic clearly and succinctly?

- What are the most interesting and relevant aspects of the topic?

- In what order do I want to present the various aspects, and how do my ideas relate to each other?

- What is my point of view regarding the topic?

Writing a Thesis Statement

Thesis statements typically consist of a single sentence and stress the main argument or claim of your paper. More often than not, the thesis statement comes at the end of your introduction paragraph; however, this can vary based on discipline and topic, so check with your instructor if you are unsure where to place it.

Thesis statement should include three main components:

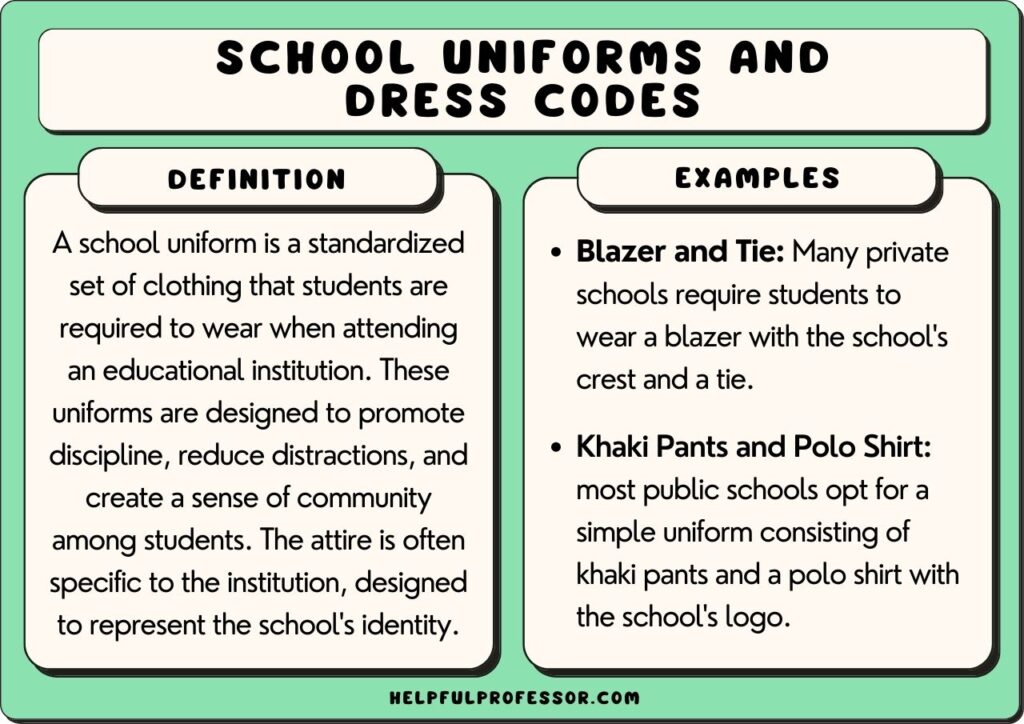

- TOPIC – the topic you are discussing (school uniforms in public secondary schools)

- CONTROLLING IDEA – the point you are making about the topic or significance of your idea in terms of understanding your position as a whole (should be required)

- REASONING – the supporting reasons, events, ideas, sources, etc. that you choose to prove your claim in the order you will discuss them. This section varies by type of essay and level of writing. In some cases, it may be left out (because they are more inclusive and foster unity)

A Strategy to Form Your Own Thesis Statement

Using the topic information, develop this formulaic sentence:

I am writing about_______________, and I am going to argue, show, or prove___________.

What you wrote in the first blank is the topic of your paper; what you wrote in the second blank is what focuses your paper (suggested by Patrick Hartwell in Open to Language ). For example, a sentence might be:

I am going to write about senior citizens who volunteer at literacy projects, and I am going to show that they are physically and mentally invigorated by the responsibility of volunteering.

Next, refine the sentence so that it is consistent with your style. For example:

Senior citizens who volunteer at literacy projects are invigorated physically and mentally by the responsibility of volunteering.

Here is a second example illustrating the formulation of another thesis statement. First, read this sentence that includes both topic and focusing comment:

I am going to write about how Plato and Sophocles understand the proper role of women in Greek society, and I am going to argue that though they remain close to traditional ideas about women, the authors also introduce some revolutionary views which increase women's place in society.

Now read the refined sentence, consistent with your style:

When examining the role of women in society, Plato and Sophocles remain close to traditional ideas about women's duties and capabilities in society; however, the authors also introduce some revolutionary views which increase women's place in society.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.6: Literary Thesis Statements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 43636

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The Literary Thesis Statement

Literary essays are argumentative or persuasive essays. Their purpose is primarily analysis, but analysis for the purposes of showing readers your interpretation of a literary text. So the thesis statement is a one to two sentence summary of your essay's main argument, or interpretation.

Just like in other argumentative essays, the thesis statement should be a kind of opinion based on observable fact about the literary work.

Thesis Statements Should Be

- This thesis takes a position. There are clearly those who could argue against this idea.

- Look at the text in bold. See the strong emphasis on how form (literary devices like symbolism and character) acts as a foundation for the interpretation (perceived danger of female sexuality).

- Through this specific yet concise sentence, readers can anticipate the text to be examined ( Huckleberry Finn) , the author (Mark Twain), the literary device that will be focused upon (river and shore scenes) and what these scenes will show (true expression of American ideals can be found in nature).

Thesis Statements Should NOT Be

- While we know what text and author will be the focus of the essay, we know nothing about what aspect of the essay the author will be focusing upon, nor is there an argument here.

- This may be well and true, but this thesis does not appear to be about a work of literature. This could be turned into a thesis statement if the writer is able to show how this is the theme of a literary work (like "Girl" by Jamaica Kincaid) and root that interpretation in observable data from the story in the form of literary devices.

- Yes, this is true. But it is not debatable. You would be hard-pressed to find someone who could argue with this statement. Yawn, boring.

- This may very well be true. But the purpose of a literary critic is not to judge the quality of a literary work, but to make analyses and interpretations of the work based on observable structural aspects of that work.

- Again, this might be true, and might make an interesting essay topic, but unless it is rooted in textual analysis, it is not within the scope of a literary analysis essay. Be careful not to conflate author and speaker! Author, speaker, and narrator are all different entities! See: intentional fallacy.

Thesis Statement Formula

One way I find helpful to explain literary thesis statements is through a "formula":

Thesis statement = Observation + Analysis + Significance

- Observation: usually regarding the form or structure of the literature. This can be a pattern, like recurring literary devices. For example, "I noticed the poems of Rumi, Hafiz, and Kabir all use symbols such as the lover's longing and Tavern of Ruin "

- Analysis: You could also call this an opinion. This explains what you think your observations show or mean. "I think these recurring symbols all represent the human soul's desire." This is where your debatable argument appears.

- Significance: this explains what the significance or relevance of the interpretation might be. Human soul's desire to do what? Why should readers care that they represent the human soul's desire? "I think these recurring symbols all show the human soul's desire to connect with God. " This is where your argument gets more specific.

Thesis statement: The works of ecstatic love poets Rumi, Hafiz, and Kabir use symbols such as a lover’s longing and the Tavern of Ruin to illustrate the human soul’s desire to connect with God .

Thesis Examples

SAMPLE THESIS STATEMENTS

These sample thesis statements are provided as guides, not as required forms or prescriptions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Literary Device Thesis Statement

The thesis may focus on an analysis of one of the elements of fiction, drama, poetry or nonfiction as expressed in the work: character, plot, structure, idea, theme, symbol, style, imagery, tone, etc.

In “A Worn Path,” Eudora Welty creates a fictional character in Phoenix Jackson whose determination, faith, and cunning illustrate the indomitable human spirit.

Note that the work, author, and character to be analyzed are identified in this thesis statement. The thesis relies on a strong verb (creates). It also identifies the element of fiction that the writer will explore (character) and the characteristics the writer will analyze and discuss (determination, faith, cunning).

The character of the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet serves as a foil to young Juliet, delights us with her warmth and earthy wit, and helps realize the tragic catastrophe.

The Genre / Theory Thesis Statement

The thesis may focus on illustrating how a work reflects the particular genre’s forms, the characteristics of a philosophy of literature, or the ideas of a particular school of thought.

“The Third and Final Continent” exhibits characteristics recurrent in writings by immigrants: tradition, adaptation, and identity.

Note how the thesis statement classifies the form of the work (writings by immigrants) and identifies the characteristics of that form of writing (tradition, adaptation, and identity) that the essay will discuss.

Samuel Beckett’s Endgame reflects characteristics of Theatre of the Absurd in its minimalist stage setting, its seemingly meaningless dialogue, and its apocalyptic or nihilist vision.

A close look at many details in “The Story of an Hour” reveals how language, institutions, and expected demeanor suppress the natural desires and aspirations of women.

Generative Questions

One way to come up with a riveting thesis statement is to start with a generative question. The question should be open-ended and, hopefully, prompt some kind of debate.

- What is the effect of [choose a literary device that features prominently in the chosen text] in this work of literature?

- How does this work of literature conform or resist its genre, and to what effect?

- How does this work of literature portray the environment, and to what effect?

- How does this work of literature portray race, and to what effect?

- How does this work of literature portray gender, and to what effect?

- What historical context is this work of literature engaging with, and how might it function as a commentary on this context?

These are just a few common of the common kinds of questions literary scholars engage with. As you write, you will want to refine your question to be even more specific. Eventually, you can turn your generative question into a statement. This then becomes your thesis statement. For example,

- How do environment and race intersect in the character of Frankenstein's monster, and what can we deduce from this intersection?

Expert Examples

While nobody expects you to write professional-quality thesis statements in an undergraduate literature class, it can be helpful to examine some examples. As you view these examples, consider the structure of the thesis statement. You might also think about what questions the scholar wondered that led to this statement!

- "Heart of Darkness projects the image of Africa as 'the other world,' the antithesis of Europe and therefore civilization, a place where man's vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality" (Achebe 3).

- "...I argue that the approach to time and causality in Boethius' sixth-century Consolation of Philosophy can support abolitionist objectives to dismantle modern American policing and carceral systems" (Chaganti 144).

- "I seek to expand our sense of the musico-poetic compositional practices available to Shakespeare and his contemporaries, focusing on the metapoetric dimensions of Much Ado About Nothing. In so doing, I work against the tendency to isolate writing as an independent or autonomous feature the work of early modern poets and dramatists who integrated bibliographic texts with other, complementary media" (Trudell 371).

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua. "An Image of Africa" Research in African Literatures 9.1 , Indiana UP, 1978. 1-15.

Chaganti, Seeta. "Boethian Abolition" PMLA 137.1 Modern Language Association, January 2022. 144-154.

"Thesis Statements in Literary Analysis Papers" Author unknown. https://resources.finalsite.net/imag...handout__1.pdf

Trudell, Scott A. "Shakespeare's Notation: Writing Sound in Much Ado about Nothing " PMLA 135.2, Modern Language Association, March 2020. 370-377.

Contributors and Attributions

Thesis Examples. Authored by: University of Arlington Texas. License: CC BY-NC

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

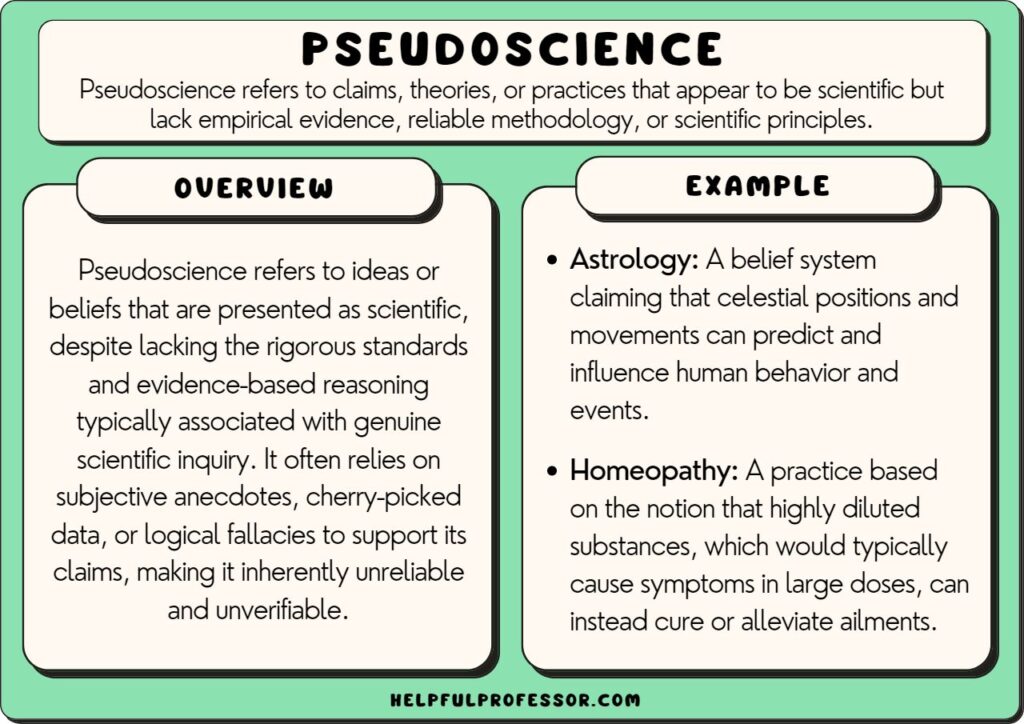

Much of the debate about identity in recent decades has been about personal identity, and specifically about personal identity over time, but identity generally, and the identity of things of other kinds, have also attracted attention. Various interrelated problems have been at the centre of discussion, but it is fair to say that recent work has focussed particularly on the following areas: the notion of a criterion of identity; the correct analysis of identity over time, and, in particular, the disagreement between advocates of perdurance and advocates of endurance as analyses of identity over time; the notion of identity across possible worlds and the question of its relevance to the correct analysis of de re modal discourse; the notion of contingent identity; the question of whether the identity relation is, or is similar to, the composition relation; and the notion of vague identity. A radical position, advocated by Peter Geach, is that these debates, as usually conducted, are void for lack of a subject matter: the notion of absolute identity they presuppose has no application; there is only relative identity. Another increasingly popular view is the one advocated by David Lewis: although the debates make sense they cannot genuinely be debates about identity, since there are no philosophical problems about identity. Identity is an utterly unproblematic notion. What there are, are genuine problems which can be stated using the language of identity. But since these can be restated without the language of identity they are not problems about identity. (For example, it is a puzzle, an aspect of the so-called “problem of personal identity”, whether the same person can have different bodies at different times. But this is just the puzzle whether a person can have different bodies at different times. So since it can be stated without the language of personal “identity”, it is not a problem about personal identity , but about personhood.) This article provides an overview of the topics indicated above, some assessment of the debates and suggestions for further reading.

1. Introduction

2. the logic of identity, 3. relative identity, 4. criteria of identity, 5. identity over time, 6. identity across possible worlds, 7. contingent identity, 8. composition as identity, 9. vague identity, 10. are there philosophical problems about identity, other internet resources, related entries.

To say that things are identical is to say that they are the same. “Identity” and “sameness” mean the same; their meanings are identical. However, they have more than one meaning. A distinction is customarily drawn between qualitative and numerical identity or sameness. Things with qualitative identity share properties, so things can be more or less qualitatively identical. Poodles and Great Danes are qualitatively identical because they share the property of being a dog, and such properties as go along with that, but two poodles will (very likely) have greater qualitative identity. Numerical identity requires absolute, or total, qualitative identity, and can only hold between a thing and itself. Its name implies the controversial view that it is the only identity relation in accordance with which we can properly count (or number) things: x and y are to be properly counted as one just in case they are numerically identical (Geach 1973).

Numerical identity is our topic. As noted, it is at the centre of several philosophical debates, but to many seems in itself wholly unproblematic, for it is just that relation everything has to itself and nothing else – and what could be less problematic than that? Moreover, if the notion is problematic it is difficult to see how the problems could be resolved, since it is difficult to see how a thinker could have the conceptual resources with which to explain the concept of identity whilst lacking that concept itself. The basicness of the notion of identity in our conceptual scheme, and, in particular, the link between identity and quantification has been particularly noted by Quine (1964).

Numerical identity can be characterised, as just done, as the relation everything has to itself and to nothing else. But this is circular, since “nothing else” just means “no numerically non-identical thing”. It can be defined, equally circularly (because quantifying over all equivalence relations including itself), as the smallest equivalence relation (an equivalence relation being one which is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, for example, having the same shape). Other circular definitions are available. Usually it is defined as the equivalence relation (or: the reflexive relation) satisfying Leibniz’s Law, the principle of the indiscernibility of identicals, that if x is identical with y then everything true of x is true of y . Intuitively this is right, but only picks out identity uniquely if “what is true of x ” is understood to include “being identical with x ”; otherwise it is too weak. Circularity is thus not avoided. Nevertheless, Leibniz’s Law appears to be crucial to our understanding of identity, and, more particularly, to our understanding of distinctness: we exhibit our commitment to it whenever we infer from “ Fa ” and “ Not-Fb ” that a is not identical with b . Strictly, what is being employed in such inferences is the contrapositive of Leibniz’s Law (if something true of a is false of b , a is not identical with b ), which some (in the context of the discussion of vague identity) have questioned, but it appears as indispensable to our grip on the concept of identity as Leibniz’s Law itself.

The converse of Leibniz’s Law, the principle of the identity of indiscernibles, that if everything true of x is true of y , x is identical with y , is correspondingly trivial if “what is true of x ” is understood to include “being identical with x ” (as required if Leibniz’s Law is to characterise identity uniquely among equivalence relations). But often it is read with “what is true of x ” restricted, e.g., to qualitative, non-relational, properties of x . It then becomes philosophically controversial. Thus it is debated whether a symmetrical universe is possible, e.g., a universe containing two qualitatively indistinguishable spheres and nothing else (Black 1952).

Leibniz’s Law has itself been subject to controversy in the sense that the correct explanation of apparent counter-examples has been debated. Leibniz’s Law must be clearly distinguished from the substitutivity principle, that if “ a ” and “ b ” are codesignators (if “ a = b ” is a true sentence of English) they are everywhere substitutable salva veritate . This principle is trivially false. “Hesperus” contains eight letters, “Phosphorus” contains ten, but Hesperus (the Evening Star) is Phosphorus (the Morning Star). Again, despite the identity, it is informative to be told that Hesperus is Phosphorus, but not to be told that Hesperus is Hesperus (“On Sense and Reference” in Frege 1969). Giorgione was so-called because of his size, Barbarelli was not, but Giorgione was Barbarelli (Quine, “Reference and Modality”, in 1963) . It is a necessary truth that 9 is greater than 7, it is not a necessary truth that the number of planets is greater than 7, although 9 is the number of planets. The explanation of the failure of the substitutivity principle can differ from case to case. In the first example, it is plausible to say that “‘Hesperus’ contains eight letters” is not about Hesperus, but about the name, and the same is true, mutatis mutandis , of “‘Phosphorus’ contains ten letters”. Thus the names do not have the same referents in the identity statement and the predications. In the Giorgione/Barbarelli example this seems less plausible. Here the correct explanation is plausibly that “is so-called because of his size” expresses different properties depending on the name it is attached to, and so expresses the property of being called “Barbarelli” because of his size when attached to “Barbarelli” and being called “Giorgione” because of his size when attached to “Giorgione”. It is more controversial how to explain the Hesperus/Phosphorus and 9/the number of planets examples. Frege’s own explanation of the former was to assimilate it to the “Hesperus”/“Phosphorus” case: in “It is informative to be told that Hesperus is Phosphorus” the names do not stand for their customary referent but for their senses. A Fregean explanation of the 9/number of planets example may also be offered: “it is necessary that” creates a context in which numerical designators stand for senses rather than numbers.

For present purposes the important point to recognise is that, however these counter-examples to the substitutivity principle are explained, they are not counter-examples to Leibniz’s Law, which says nothing about substitutivity of codesignators in any language.

The view of identity just put forward (henceforth “the classical view”) characterises it as the equivalence relation which everything has to itself and to nothing else and which satisfies Leibniz’s Law. These formal properties ensure that, within any theory expressible by means of a fixed stock of one- or many-place predicates, quantifiers and truth-functional connectives, any two predicates which can be regarded as expressing identity (i.e., any predicates satisfying the two schemata “for all x , Rxx ” and “for all x , for all y , Rxy → ( Fx → Fy )” for any one-place predicate in place of “ F ”) will be extensionally equivalent. They do not, however, ensure that any two-place predicate does express identity within a particular theory, for it may simply be that the descriptive resources of the theory are insufficiently rich to distinguish items between which the equivalence relation expressed by the predicate holds (“Identity” in Geach 1972).

Following Geach, call a two-place predicate with these properties in a theory an “I-predicate” in that theory. Relative to another, richer, theory the same predicate, interpreted in the same way, may not be an I-predicate. If so it will not, and did not even in the poorer theory, express identity. For example, “having the same income as” will be an I-predicate in a theory in which persons with the same income are indistinguishable, but not in a richer theory.

Quine (1950) has suggested that when a predicate is an I-predicate in a theory only because the language in which the theory is expressed does not allow one to distinguish items between which it holds, one can reinterpret the sentences of the theory so that the I-predicate in the newly interpreted theory does express identity. Every sentence will have just the same truth-conditions under the new interpretation and the old, but the references of its subsentential parts will be different. Thus, Quine suggests, if one has a language in which one speaks of persons and in which persons of the same income are indistinguishable the predicates of the language may be reinterpreted so that the predicate which previously expressed having the same income comes now to express identity. The universe of discourse now consists of income groups, not people. The extensions of the monadic predicates are classes of income groups, and, in general, the extension of an n -place predicate is a class of n -member sequences of income groups (Quine 1963: 65–79). Any two-place predicate expressing an equivalence relation could be an I-predicate relative to some sufficiently impoverished theory, and Quine’s suggestion will be applicable to any such predicate if it is applicable at all.

But it remains that it is not guaranteed that a two-place predicate that is an I-predicate in the theory to which it belongs expresses identity. In fact, no condition can be stated in a first-order language for a predicate to express identity, rather than mere indiscernibility by the resources of the language. However, in a second-order language, in which quantification over all properties (not just those for which the language contains predicates) is possible and Leibniz’s Law is therefore statable, identity can be uniquely characterised. Identity is thus not first-order, but only second-order definable.

This situation provides the basis for Geach’s radical contention that the notion of absolute identity has no application and that there is only relative identity. This section contains a brief discussion of Geach’s complex view. (For more details see the entry on relative identity , Deutsch 1997, Dummett 1981 and 1991, Hawthorne 2003 and Noonan 2017.) Geach maintains that since no criterion can be given by which a predicate expressing an I-predicate may be determined to express, not merely indiscernibility relative to the language to which it belongs, but also absolute indiscernibility, we should jettison the classical notion of identity (1991). He dismisses the possibility of defining identity in a second-order language on the ground of the paradoxical nature of unrestricted quantification over properties and aims his fire particularly at Quine’s proposal that an I-predicate in a first-order theory may always be interpreted as expressing absolute identity (even if such an interpretation is not required ). Geach objects that Quine’s suggestion leads to a “Baroque Meinongian ontology” and is inconsistent with Quine’s own expressed preference for “desert landscapes” (“Identity” in Geach 1972: 245).

We may usefully state Geach’s thesis using the terminology of absolute and relative equivalence relations. Let us say that an equivalence relation R is absolute if and only if, if x stands in it to y , there cannot be some other equivalence relation S , holding between anything and either x or y , but not holding between x and y . If an equivalence relation is not absolute it is relative. Classical identity is an absolute equivalence relation. Geach’s main contention is that any expression for an absolute equivalence relation in any possible language will have the null class as its extension, and so there can be no expression for classical identity in any possible language. This is the thesis he argues against Quine.

Geach also maintains the sortal relativity of identity statements, that “ x is the same A as y ” does not “split up” into “ x is an A and y is an A and x = y ”. More precisely stated, what Geach denies is that whenever a term “ A ” is interpretable as a sortal term in a language L (a term which makes (independent) sense following “the same”) the expression (interpretable as) “ x is the same A as y ” in language L will be satisfied by a pair < x , y > only if the I-predicate of L is satisfied by < x , y >. Geach’s thesis of the sortal relativity of identity thus neither entails nor is entailed by his thesis of the inexpressibility of identity. It is the sortal relativity thesis that is the central issue between Geach and Wiggins (1967 and 1980). It entails that a relation expressible in the form “ x is the same A as y ” in a language L , where “ A ” is a sortal term in L , need not entail indiscernibility even by the resources of L .

Geach’s argument against Quine exists in two versions, an earlier and a later.

In its earlier version the argument is merely that following Quine’s suggestion to interpret a language in which some expression is an I-predicate so that the I-predicate expresses classical identity sins against a highly intuitive methodological programme enunciated by Quine himself, namely that as our knowledge expands we should unhesitatingly expand our ideology, our stock of predicables, but should be much more wary about altering our ontology, the interpretation of our bound name variables (1972: 243).