AP ® Lang teachers: looking to help your students improve their rhetorical analysis essays?

Coach Hall Writes

clear, concise rhetorical analysis instruction.

How to Teach Synthesis

December 23, 2022 by Beth Hall

Wondering how to teach synthesis essay writing? This blog post contains some examples of synthesis activities that help make writing a synthesis essay more approachable for students.

Synthesis Dinner Party

The synthesis dinner party is a popular synthesis activity among AP ® Lang teachers. It is a great way to introduce students to the idea of having a “conversation of sources.”

Note: The “dinner party” concept came from Kenneth Burke in The Philosophy of Literary Form in 1941.

To prep, you’ll want to make a graphic organizer for your students. I usually make one on Google Slides. I use a rectangle for the “table.” Then I write the prompt in the form of a question in that box. Next, I add squares as seats around the table. If there are 6 sources, I add 6 squares: one at each end of the rectangle and two on each side. Honestly, this does not have to be fancy, but you can add fun graphics if you wish.

First, have your students read the sources independently or as a class. In order to do the synthesis dinner party well, students need to be familiar with the sources first.

Next, explain the premise of a dinner party. While students might not have attended a formal dinner party, they may have some frame of reference for seating at a family gathering or even the high school lunch table.

Explain to students that the sources will be the guests of a dinner party, and they are in charge of making a seating chart. They want to make sure that they seat sources in a way that will lead to “good” or “civil” conversation.

If it is the first time my students have done this activity, I usually draw the seating chart on my white board or display the slides on the TV in my classroom. Then, I’ll tell the students that I want them to fill in the seats at the opposite ends of the table first. I want them to put sources that contradict each other or would not get along in those seats. At this point, I like to ask “why would I put contrasting sources in those spots?” Students then answer that it is because those are the farthest apart.

Depending on the group of students, this may be an opportune time to mention that one of these sources could possibly be used as a counterargument for the other.

The first time students do this activity, it is helpful to let them work with a partner or small group to decide which sources belong on the ends. Then I have groups share out their decision and explain their reasoning.

There is more than one “right” answer. It’s all about being able to defend your reasoning, which means students can practice making claims as they determine their seating chart.

After seating the sources at the end of the table, students can then fill in the other seats. This requires students to think about commonalities between the source’s main ideas or positions. Sources that are seated next to one another may pair well in a paragraph when students write the essay.

Sometimes students may be unsure where to place neutral sources, but the good news is that if the source is neutral, it can pretty much be placed anywhere, so it may help to “seat” them last.

Extension Activity

In addition to having students verbally share their reasoning behind their placement of the “end of the table” sources, I like to have students write a brief paragraph after they have finalized their seating chart. In the paragraph, I ask them to explain their rationale for seating the sources where they did. For example, students might explain what the sources have in common or why a particular source needs to be seated away from another source. As previously stated, this is a simple way to have students practice writing a claim, but it also helps them articulate their line of reasoning for their seating chart.

While I don’t do the dinner party too often, this is a great synthesis activity for students who are unfamiliar with how to synthesize sources.

Synthesis Sources T-Chart

Making a t-chart is simple, but it is also one of my favorite tips for how to teach synthesis. This is a practical synthesis activity students can do on their own on exam day if they’d like to organize their thoughts.

I did this activity recently with my students. Our prompt was “Should kindergarten be transformed into a more academic environment?” After students have read the sources, have them make a t-chart. For our prompt, one side of the t-chart said “reasons kindergarten should be more academic,” and the other side said “reasons why kindergarten should not be more academic.”

Have students work with a partner or small group to add entries to their t-chart. They do not need equal entries on both sides of the t-chart.

It helps if students write the source(s) that correspond with each reason. This will help them if they write the synthesis essay in a future lesson.

Next, ask for volunteers to share out their reasons and make a collaborative t-chart as a class. Encourage students to add to their t-charts as needed.

Making a t-chart can help students identify potential main ideas for their essay. It also helps them realize which sources relate to each other or contradict each other.

Sticky Note Continuum

I like to do this synthesis activity after the t-chart activity. For the “sticky note continuum,” you’ll need sticky notes and a dry erase board or large piece of paper. Personally, I like to use these lined sticky notes.

To prep, draw a continuum on the board or on your paper. If desired, write the prompt in the form of a question above the continuum.

This is a photo of the synthesis sticky note continuum.

Have students work independently, with a partner, or as a small group to write a claim in response to the prompt. If needed, provide students with a sentence frame. I like to have students write their claim on a regular piece of paper first before writing it on a sticky note.

Allowing students to collaborate during this synthesis activity allows them to learn from each other. Have them to focus on the word choice and syntax of their claim.

Once students have written their claim, have them rewrite it on a sticky note. Next, they place it on the continuum where they think it belongs.

Want more tips for teaching AP ® Lang? Check out this blog post.

Looking for more tips for how to teach synthesis? Be sure to sign up for my teacher email list. When you do, you’ll receive my 5 tips for teaching rhetorical analysis. Don’t worry. I send synthesis teaching tips too.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Affiliate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

AP® Lang Teachers

Looking to help your students improve their rhetorical analysis essays?

January 8, 2023 at 9:04 pm

Are the sources for the kindergarten prompt posted anywhere? Thanks!

June 30, 2023 at 10:01 pm

The kindergarten prompt is in AP Classroom. I also add this article from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/10/the-joyful-illiterate-kindergartners-of-finland/408325/

Latest on Instagram

Shop My TPT Store

| Drew University On-Line Resources for Writers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

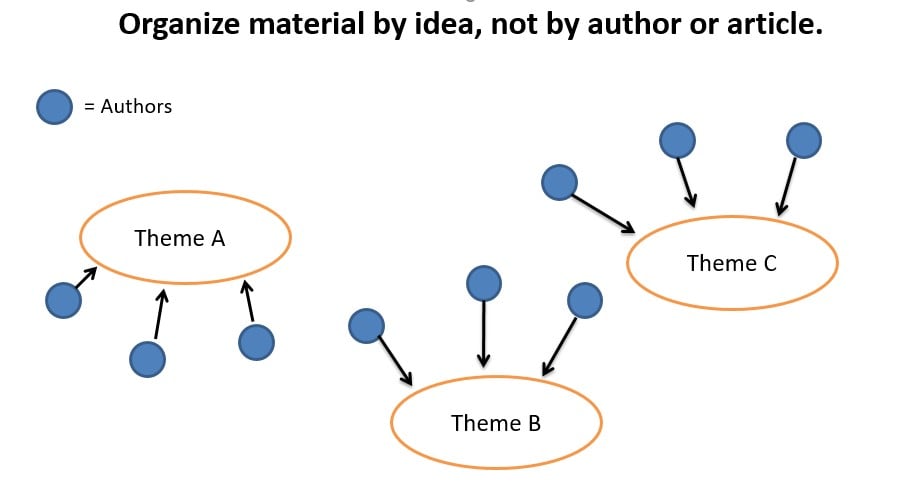

Whenever you report to a friend the things several other friends have said about a film or CD you engage in synthesis. People synthesize information naturally to help other see the connections between things they learn; for example, you have probably stored up a mental data bank of the various things you've heard about particular professors. If your data bank contains several negative comments, you might synthesize that information and use it to help you decide not to take a class from that particular professor. Synthesis is related to but not the same as classification, division, or comparison and contrast. Instead of attending to categories or finding similarities and differences, synthesizing sources is a matter of pulling them together into some kind of harmony. Synthesis searches for links between materials for the purpose of constructing a thesis or theory. The basic research report (described below as a background synthesis) is very common in the business world. Whether one is proposing to open a new store or expand a product line, the report that must inevitably be written will synthesize information and arrange it by topic rather than by source. Whether you want to present information on child rearing to a new mother, or details about your town to a new resident, you'll find yourself synthesizing too. And just as in college, the quality and usefulness of your synthesis will depend on your accuracy and organization. In the process of writing his or her background synthesis, the student explored the sources in a new way and become an expert on the topic. Only when one has reached this degree of expertise is one ready to formulate a thesis. Frequently writers of background synthesis papers develop a thesis before they have finished. In the previous example, the student might notice that no two colleges seem to agree on what constitutes "co-curricular," and decide to research this question in more depth, perhaps examining trends in higher education and offering an argument about what this newest trend seems to reveal. [ More information on developing a research thesis .] On the other hand, all research papers are also synthesis papers in that they combine the information you have found in ways that help readers to see that information and the topic in question in a new way. A research paper with a weak thesis (such as: "media images of women help to shape women's sense of how they should look") will organize its findings to show how this is so without having to spend much time discussing other arguments (in this case, other things that also help to shape women's sense of how they should look). A paper with a strong thesis (such as "the media is the single most important factor in shaping women's sense of how they should look") will spend more time discussing arguments that it rejects (in this case, each paragraph will show how the media is more influential than other factors in that particular aspect of women's sense of how they should look"). [See also thesis-driven research papers .] [See also " Preparing to Write the Synthesis Essay ," " Writing the Synthesis Essa y ," and " Revision . "] Because each discipline has specific rules and expectations, you should consult your professor or a guide book for that specific discipline if you are asked to write a review of the literature and aren't sure how to do it. [See also " Preparing to Write the Synthesis Essay ," " Writing the Synthesis Essa y," and " Revision ."] Regardless of whether you are synthesizing information from prose sources, from laboratory data, or from tables and graphs, your preparation for the synthesis will very likely involve comparison . It may involve analysis , as well, along with classification, and division as you work on your organization. Sometimes the wording of your assignment will direct you to what sorts of themes or traits you should look for in your synthesis. At other times, though, you may be assigned two or more sources and told to synthesize them. In such cases you need to formulate your own purpose, and develop your own perspectives and interpretations. A systematic preliminary comparison will help. Begin by summarizing briefly the points, themes, or traits that the texts have in common (you might find summary-outline notes useful here). Explore different ways to organize the information depending on what you find or what you want to demonstrate ( see above ). You might find it helpful to make several different outlines or plans before you decide which to use. As the most important aspect of a synthesis is its organization, you can't spend too long on this aspect of your paper! A synthesis essay should be organized so that others can understand the sources and evaluate your comprehension of them and their presentation of specific data, themes, etc. The following format works well: The introduction (usually one paragraph) 1. Contains a one-sentence statement that sums up the focus of your synthesis. 2. Also introduces the texts to be synthesized: (i) Gives the title of each source (following the citation guidelines of whatever style sheet you are using); (ii) Provides the name of each author; (ii) Sometimes also provides pertinent background information about the authors, about the texts to be summarized, or about the general topic from which the texts are drawn. The body of a synthesis essay: This should be organized by theme, point, similarity, or aspect of the topic. Your organization will be determined by the assignment or by the patterns you see in the material you are synthesizing. The organization is the most important part of a synthesis, so try out more than one format. Be sure that each paragraph : 1. Begins with a sentence or phrase that informs readers of the topic of the paragraph; 2. Includes information from more than one source; 3. Clearly indicates which material comes from which source using lead in phrases and in-text citations. [Beware of plagiarism: Accidental plagiarism most often occurs when students are synthesizing sources and do not indicate where the synthesis ends and their own comments begin or vice verse.] 4. Shows the similarities or differences between the different sources in ways that make the paper as informative as possible; 5. Represents the texts fairly--even if that seems to weaken the paper! Look upon yourself as a synthesizing machine; you are simply repeating what the source says, in fewer words and in your own words. But the fact that you are using your own words does not mean that you are in anyway changing what the source says. Conclusion. When you have finished your paper, write a conclusion reminding readers of the most significant themes you have found and the ways they connect to the overall topic. You may also want to suggest further research or comment on things that it was not possible for you to discuss in the paper. If you are writing a background synthesis, in some cases it may be appropriate for you to offer an interpretation of the material or take a position (thesis). Check this option with your instructor before you write the final draft of your paper.

Online Guide to Writing and ResearchThinking strategies and writing patterns, explore more of umgc.

Critical Strategies and Writing One of the basic academic writing activities is researching your topic and what others have said about it. Your goal should be to draw thoughts, observations, and claims about your topic from your research. We call this process of drawing from multiple sources “ synthesis .” Click on the accordion items below for more information. Definition, Use, and Sample SynthesisSynthesis defined. Synthesis Emerges from Analysis Synthesis emerges from analytical activities we discussed on the previous page: comparative analysis and analysis for cause and effect . For example, to communicate where scholars agree and where they disagree, one must analyze their work for similarities and differences. Also crucial for understanding scholarly discourse is understanding how a particular work of scholarship shapes the scholarship of others, causing them to head in new directions. When Should Synthesis Be Used?When to Use Synthesis Many college assignments require synthesis. A literature review, for example, requires that you make explanatory claims regarding a body of research. These should go beyond summary (mere description) to provide helpful characterizations that aid in understanding. Literature reviews can stand on their own, but often they are a part of a research paper, and research papers are where you will probably use synthesis most often. The purpose of a research paper is to derive meaning from a body of information collected through research. It is your job, as the writer, to communicate that meaning to your readers. Doing this requires that you develop an informed and educated opinion of what your research suggests about your subject. Communicating this opinion requires synthesis. Sample SynthesisIn 1655, an embassy of Dutch Jews led by Rabbi Menassah ben Israel traveled to London to meet with the Commonwealth’s new Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. The informal “Readmission” of Jews—who had been expelled from England by royal edict in 1290—resulting from the Whitehall conference was once hailed as a high point in the history of toleration. Yet in recent years, scholars have increasingly challenged the progressive nature of this event, both in its substance and its motivation (Kaplan 2007; Katznelson 2010; Walsham 2006) . “Toleration” in this case, as in many others, did not entail religious freedom or civic equality; Jews in England were granted legal residency and permitted to worship privately, but citizenship, public worship, and the printing of anything that “opposeth the Christian religion” remained off the cards. As for its motivation, Edward Whalley’s twofold argument was representative: the Jews “will bring in much wealth into this Commonwealth: and where wee both pray for theyre conversion and beleeve it shal be, I knowe not why wee shold deny the means” (Marshall 2006, 381–82) (Bejan, 2015, p. 1103). The author of the above passage, Teresa Bejan, has synthesized the work of a number of other scholars (Kaplan, Katznelson, Walsham, and Marshall) to situate her argument. Note how not all of these scholars are directly quoted, but they are cited because their work forms the basis of Bejan's work. Key Takeaways

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites. Table of Contents: Online Guide to WritingChapter 1: College Writing How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing? What Is College Writing? Why So Much Emphasis on Writing? Chapter 2: The Writing Process Doing Exploratory Research Getting from Notes to Your Draft Introduction Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy Rewriting: Getting Feedback Rewriting: The Final Draft Techniques to Get Started - Outlining Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas Writing: Outlining What You Will Write Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis Developing a Paper Using Strategies Kinds of Assignments You Will Write Patterns for Presenting Information Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts Supporting with Research and Examples Writing Essay Examinations Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question Chapter 4: The Research Process Planning and Writing a Research Paper Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources Research Resources: What Are Research Resources? Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure The Nature of Research The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated? The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed? The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research? Chapter 5: Academic Integrity Academic Integrity Giving Credit to Sources Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides Integrating Sources Practicing Academic Integrity Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources Types of Documentation Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style Types of Documentation: Note Citations Chapter 6: Using Library Resources Finding Library Resources Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing How Is Writing Graded? How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool The Draft Stage The Draft Stage: The First Draft The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft The Draft Stage: Using Feedback The Research Stage Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers Writing Arguments Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion Writing Arguments: Types of Argument Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your WritingDictionaries General Style Manuals Researching on the Internet Special Style Manuals Writing Handbooks Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer ReviewingCollaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve Collaborative Writing: Methodology Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan General Introduction Peer Reviewing Appendix C: Developing an Improvement PlanWorking with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project ScheduleDevising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule Reviewing Your Plan with Others By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Writing Across the Curriculum

Writing with Sources: Early-Semester Activities to Promote SynthesisWhile students in nearly every upper-division course will be asked to analyze and synthesize information, the meaning of these terms changes with instructional contexts. They may analyze scholarly arguments to make an assertion about the state of knowledge or create a new research question. Students may also analyze results from experimental tests to draw accurate conclusions from measurement, while in another course, they may be tasked with analyzing multiple policies or practices and then designing their own. Given the range of ways synthesis can work in writing, this blog post focuses on strategies for creating explicit description of what synthesis means, and offers some early semester assignments to help prepare students for this complex work. In this post, construction metaphors (“building” or “making” language) provide a helpful vocabulary for writing assignments that promote synthesis. Preparing the ground Synthesis assignments fall broadly in two groups: explanatory synthesis, where multiple sources are used to create a comprehensive description, and argumentative synthesis, where students are asked to advance a claim based on reasons and evidence. Clarifying your assignment's purpose and audience can help focus students on their writing task. Consider what you notice about writing in your field that succeeds in creating synthesis.

As an early assignment, ask students to write brief topic proposals or topic justification assignments that identify the topic, its relevance to the course, and some preliminary thoughts on potential questions about or connections between concepts and ideas. Emphasizing the role of connections among sources is critical here; not merely accumulating resources from multiple sources but seeing and describing their interrelationships. Gathering materials: Pre-fab or made from scratch?Students can think and write synthetically using resources selected by their instructors or by conducting their own searches for information. In cases where the task is unfamiliar, starting with shared resources can help students focus on concepts, themes, or issues without adding the challenge of selecting relevant resources. More advanced students may prefer the opportunity to follow their specialized interests and explore a wider literature. Early assignments with shared resourcesReading responses can be an effective early-semester assignment for engaging with course resources. Faculty can help students understand the content of their reading by offering context (answering those 5 Ws questions) for individual selections, but ask students to think about why certain readings might be offered together or in sequence. Better assignments will move beyond comparison and contrast into connections and implications. Source grids can also help students to draw connections between readings and resources. For example, in a nursing course, students are asked to produce summaries of course readings and organize them in a table that addresses the population studied, intervention, comparison, and outcome. EBSCO offers a nice summary of PICO questions here . Early assignments for information-seekingWhen students are asked to seek their own information or research their own topics, they will need to work harder to determine the relevance of information and criteria for attention and inclusion. Many instructors already assign online tutorials from the University libraries to help students navigate disciplinary databases and develop research questions. Subject librarians and department liaisons for your college, department, or program are excellent collaborators for designing such tasks . Information-seeking assignments can include mind maps (using what students already know to suggest search terms), summaries of reference articles , or initial reference lists . In addition, process-oriented assignments like research logs can help students to show their work by documenting their search strategies (databases, keywords, and limiters used). Additional ResourcesReading and Writing has just published a special issue (December 2022) under the title, Synthesis Tasks: Where reading and writing meet . Read the introduction from the editors . Further SupportSee the Teaching with Writing pages or teaching resources . As many of you know, our WAC program also hosts the popular Teaching with Writing event series. Each semester, this series offers free workshops and discussions. Visit us online and follow us on Twitter @UMNWriting . Looking to change up writing assignments or grading strategies? Talk to us! We like thinking with faculty members, instructors, and TA/GIs about any and all matters related to teaching with writing in courses across the University curriculum. Got questions about writing assignments and activities, grading writing, providing feedback, or using digital tools? Contact us to schedule a phone, email, or face-to-face teaching consultation.

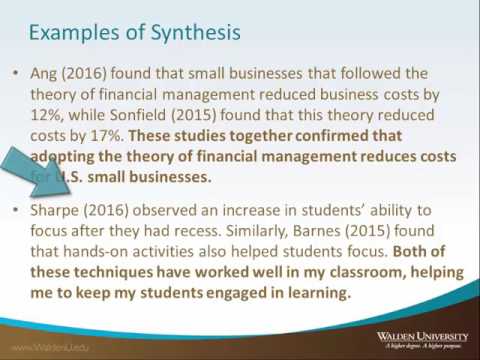

Using Evidence: SynthesisSynthesis video playlist. Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.  Basics of SynthesisAs you incorporate published writing into your own writing, you should aim for synthesis of the material. Synthesizing requires critical reading and thinking in order to compare different material, highlighting similarities, differences, and connections. When writers synthesize successfully, they present new ideas based on interpretations of other evidence or arguments. You can also think of synthesis as an extension of—or a more complicated form of—analysis. One main difference is that synthesis involves multiple sources, while analysis often focuses on one source. Conceptually, it can be helpful to think about synthesis existing at both the local (or paragraph) level and the global (or paper) level. Local SynthesisLocal synthesis occurs at the paragraph level when writers connect individual pieces of evidence from multiple sources to support a paragraph’s main idea and advance a paper’s thesis statement. A common example in academic writing is a scholarly paragraph that includes a main idea, evidence from multiple sources, and analysis of those multiple sources together. Global SynthesisGlobal synthesis occurs at the paper (or, sometimes, section) level when writers connect ideas across paragraphs or sections to create a new narrative whole. A literature review , which can either stand alone or be a section/chapter within a capstone, is a common example of a place where global synthesis is necessary. However, in almost all academic writing, global synthesis is created by and sometimes referred to as good cohesion and flow. Synthesis in Literature ReviewsWhile any types of scholarly writing can include synthesis, it is most often discussed in the context of literature reviews. Visit our literature review pages for more information about synthesis in literature reviews. Related WebinarsDidn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

Walden ResourcesDepartments.

Centers and Offices

Student Resources

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved. Check Out the New Website Shop!  Novels & Picture Books Anchor Charts

3 Tips for Teaching SynthesisBy Mary Montero Share This Post:

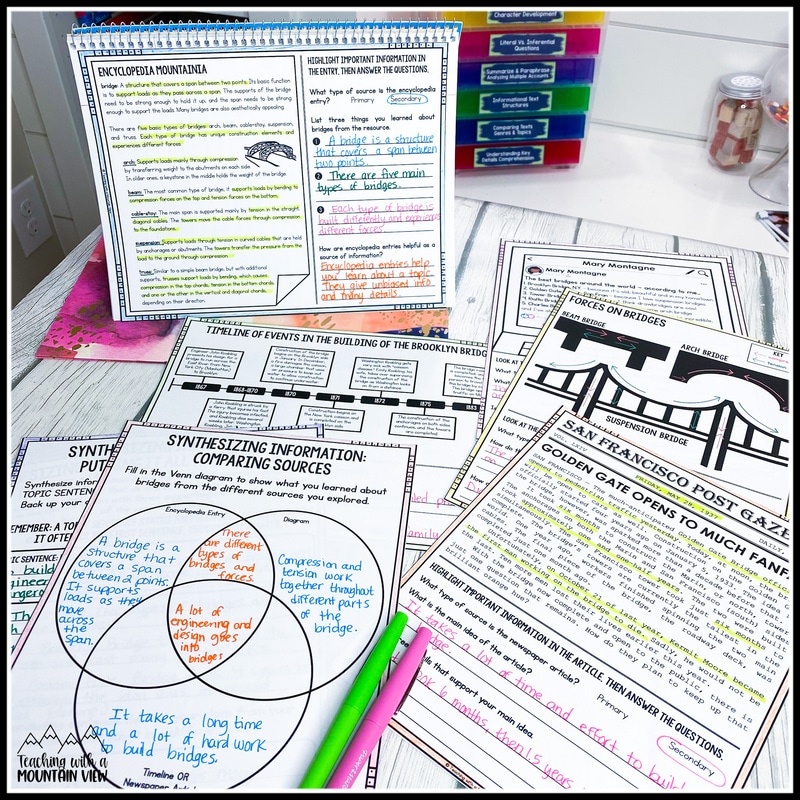

During a planning session one day, I was reviewing the standards for my upcoming unit. I read one of the standards to a teacher next to me: “How exactly do we teach students to ‘synthesize information to create a new understanding’?” I knew what the word synthesize meant, but I needed an authentic, easy-to-understand way to convey its meaning to my students. Here are my best three tips for teaching synthesis to your upper elementary students.  What exactly is synthesis and why do we teach it?Synthesizing is the process of combining sources to create a shared meaning. It’s a fancy word for something you actually do quite often. When a big news story comes out you might read about it in an article, hear about it from a friend, and watch a story about it on the news. You then combine different sources of information to create meaning. That is synthesizing information. This can be a challenging skill for students. Synthesizing or combining sources requires students to compare and contrast, make connections across texts and genres, have stellar reading comprehension, take notes and pick out key details, and more. However, challenging doesn’t have to mean impossible! With plenty of practice, students can master combining sources and synthesizing the information within them. Here are my favorite ways to help students master synthesizing.#1 create a synthesis statement. If your students are new to synthesis, consider starting small. Find two sources about a topic. Sources can be articles, videos, pictures, or diagrams. Make sure you find a super high-interest topic for this one! For example, students could watch a video about how candy corn is made and then read about the history of candy corn. After viewing both sources, they will craft a synthesis. To help students, you can provide them one of the following sentence frames:

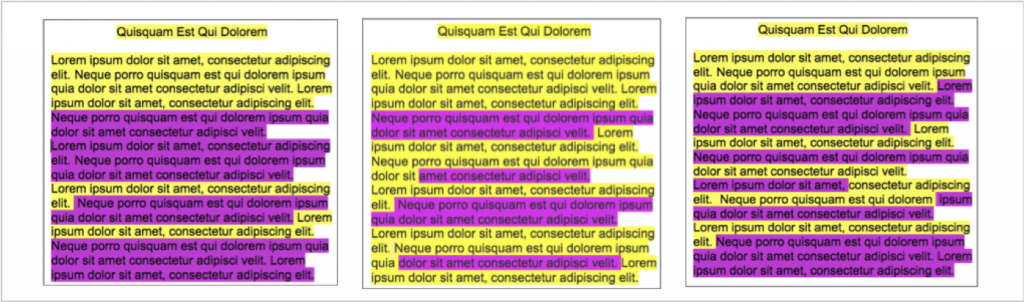

At this point, I encourage them to highlight information they learned from ONE source in one color and the other source in a different color. #2 Create a Synthesis from Multiple, Varied SourcesOnce students understand the basics of synthesis, you can push and challenge their knowledge further. One way to do this is through several sources on a similar topic. Students will combine the information from several sources to create one new meaning. This is a more challenging task for students, so don’t worry if your students don’t master it the first time. To make practicing combining sources easier, I created several nonfiction synthesis activities for students . In this resource, students are given 5 high-quality sources to read and make a synthesis from. Sources vary from social media posts, quotes, diagrams, encyclopedia entries, timelines, newspaper articles, etc. This resource also includes guided questions and tasks to help students with their synthesis. This resource is planned to help guide your students through the process of synthesis. Each synthesis activity focuses on a different topic: bridges, education rights, photosynthesis, and the Titanic. You can have access to all of these topics through Nonfiction Synthesizing and Combining Multiple Sources bundle.  #3 Research a TopicA very common way to practice synthesis in school is through research projects. Naturally, research projects require students to view many sources and combine the information they learn to answer a research question. The great part about research is that it can be as involved or as simple as you want it to be. For beginner students, you may want to give them a research question. For students with more research practice, they can create their own. Before diving into research, be sure to explain to students where they can find a variety of (good) sources. Define what a “good” source is (though this is covered extensively in the Nonfiction Synthesizing and Combining Multiple Sources bundle !). After students have collected their research, they will then draft a paragraph or essay. Their topic sentence and writing will be created from their synthesis of their sources! Related SkillsSynthesis can be a tough skill, but with enough practice, your students will begin to show mastery. If you want more tips on helping your students become successful synthesizers, check out these blog posts on comparing passages , writing summaries for texts , or analyzing firsthand and secondhand accounts (all skills needed fo r synthesizing!). Mary MonteroI’m so glad you are here. I’m a current gifted and talented teacher in a small town in Colorado, and I’ve been in education since 2009. My passion (other than my family and cookies) is for making teachers’ lives easier and classrooms more engaging. You might also like… Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *  ©2023 Teaching With a Mountain View . All Rights Reserved | Designed by Ashley Hughes Username or Email Address Remember Me Lost your password? Review CartNo products in the cart. How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple SourcesShona McCombes Content Manager B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands. Learn about our Editorial Process Saul Mcleod, PhD Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology. On This Page: When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in). Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point. At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge. Unsynthesized ExampleFranz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations. Synthesized ExampleStudies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample… Step 1: Organize your sourcesAfter collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together. Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources. One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this. Summary tableA summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers. Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with. For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion. For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.  The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings. Synthesis matrixA synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic. Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources. Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.  The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree. Step 2: Outline your structureNow you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them. For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings. There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis. If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically . That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature. If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically . That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.  Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically . That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method. If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically . That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing. Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentencesWhat sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence. This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it. A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content: “Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].” For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique: “Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.” By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing. As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature. Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic. Step 4: Revise, edit and proofreadLike any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work. Checklist for Synthesis

Further InformationHow to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize! Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources) How to write a Psychology Essay Module 8: Analysis and SynthesisSynthesis in practice, learning objectives.

Professors frequently expect you to interpret, make inferences, and otherwise synthesize—bring ideas together to make something new or find a new way of looking at something old. (It might help to think of synthesis as the opposite of analysis. To synthesize is to combine; to analyze is to break down.) Getting Better at SynthesisTo get an A on essays and papers in many courses, such as literature and history, what you write in reaction to the work of others should use synthesis to create new meaning or to show a deeper understanding of what you learned. To do so, it helps to look for connections and patterns. One way to synthesize when writing an argument essay, paper, or other project is to look for themes among your sources. So try categorizing ideas by topic rather than by source—making associations across and between sources. Synthesis can seem difficult, particularly if you are used to analyzing others’ points but not used to making your own. Like most things, however, it gets easier with practice. So don’t be hard on yourself if it seems difficult at first. EXAMPLE: Synthesis in an Argument In the movie, a successful young screenwriter named Gil is visiting Paris with his girlfriend and her parents, who are more politically conservative than he is. Inexplicably, every midnight he time-travels back to the 1920’s Paris, a time period he’s always found fascinating, especially because of the writers and painters—Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Picasso—with whom he’s now on a first-name basis. Gil is enchanted and always wants to stay in this fantastical past. But every morning, he’s back in the real present—feeling out of sync with his girlfriend and her parents. For your essay, you’ve tried to come up with a narrower topic, but so far nothing seems right. Suddenly, you start paying more attention to the girlfriend’s parents’ dialogue about politics, which amount to such phrases as “we have to go back to…,” “it was a better time,” “Americans used to be able to…” and “the way it used to be.” And then it clicks with you that the girlfriend’s parents are like Gil—longing for a different time, whether real or imagined. That kind of idea generation, where you find the connection and theme across related elements of the movie, is synthesis. You decide to write your essay to answer the research question: How is the motivation of Gil’s girlfriend’s parents similar to Gil’s? Your thesis becomes “Despite seeming to be very different, Gil and his girlfriend’s parents are similarly motivated, and Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris’s message about nostalgia can be applied to all of them.” Of course, you’ll have to try to convince your readers that your thesis is valid, and you may or not be successful,—but that’s true with all theses. And your professor will be glad to see the synthesis. Synthesizing From Multiple SourcesBelow are some questions that highlight ways in which the act of synthesizing brings together ideas and generates new knowledge. How do the sources speak to your specific argument or research question? Your argument or research question is the main unifying element in your project. Keep this in the forefront of your mind when you write about your sources. Explain how, specifically, each source supports your central claim/s or suggests possible answers to your question. For example: Does the source provide essential background information or a definitional foundation for your argument or inquiry? Does it present numerical data that supports one of your points or helps you answer a question you have posed? Does it present a theory that might be applied to some aspect of your project? Does it present a recognized expert’s insights on your topic? How do the sources speak to each other? Sometimes you will find explicit dialogue between sources (for example, Source A refutes Source B by name), and sometimes you will need to bring your sources into dialogue (for example, Source A does not mention Source B, but you observe that the two are advancing similar or dissimilar arguments). Attending to interrelationships among sources is at the heart of the task of synthesis.  Figure 1 . A strong argument will utilize many different sources to support itself. Synthesizing by identifying interrelationships among these sources will help to strengthen your paper. Begin by asking: What are the points of agreement? Where are there disagreements? But be aware that you are unlikely to find your sources in pure positions of “for” vs. “against.” You are more likely to find agreement in some areas and disagreement in other areas. You may also find agreement but for different reasons—such as different underlying values and priorities, or different methods of inquiry. Where are there, or aren’t there, information gaps? Where is the available information unreliable (for example, it might be difficult to trace back to primary sources), or limited, (for example, based on just a few case studies, or on just one geographical area), or difficult for non-specialists to access (for example, written in specialist language, or tucked away in a physical archive)? Does your inquiry contain sub-questions that may not at present be answerable, or that may not be answerable without additional primary research—for example, laboratory studies, direct observation, interviews with witnesses or participants, etc.? Or, alternatively, is there a great deal of reliable, accessible information that addresses your question or speaks to your argument or inquiry? In considering these questions, you are engaged in synthesis: you are conducting an overview assessment of the field of available information and in this way generating composite knowledge. Remember, synthesis is about pulling together information from a range of sources in order to answer a question or construct an argument. It is something you will be called upon to do in a wide variety of academic, professional, and personal contexts. Being able to dive into an ocean of information and surface with meaningful conclusions is an essential skill. Synthesis in Literature ReviewsOne place synthesis is usually required is in literature reviews for honors’ theses, master’s theses, and Ph.D. dissertations. In all those cases, literature reviews are intended to contribute more than annotated bibliographies do and to be arguments for the research conducted for the theses or dissertations. If you are writing an honors thesis, master’s thesis, or Ph.D. dissertation, you will find more help with Susan Imel’s Writing a Literature Review . Showing SynthesisSome ways to demonstrate synthesis in your writing is to compare and contrast multiple sources. Below are some examples of sentence structures that demonstrate synthesis: Synthesis that indicates agreement/support:

Synthesis that indicates disagreement/conflict:

What the above examples indicate is that synthesis is the careful weaving in of outside opinions in order to show your reader the many ideas and arguments on your topic and further assert your own. Notice, too, that the above examples are also signal phrases : language that introduces outside source material to be either quoted or paraphrased, i.e., “contrary to what Source A has argued, source B maintains ___________ .” Try It: Balancing Sources and SynthesisHere’s a technique to quickly assess whether there is enough of your original thought in your essay or paper, as opposed to information from your sources: Highlight what you have included as quotes, paraphrases, and summaries from your sources. Next, highlight in another color what you have written yourself. Then take a look at the pages and decide whether there is enough of your own thinking in them. For the mocked-up pages below, assume that the yellow-highlighted lines were written by the writer and the pink-highlighted lines are quotes, paraphrases, and summaries she pulled from her sources. Which page most demonstrates the writer’s own ideas?  Source: Joy McGregor. “A Visual Approach: Teaching Synthesis,” School Library Monthly, Volume XXVII, Number 8/May-June 2011. Answer: The Middle Sample. The yellow-highlighted sections in the middle sample shows more contributions from the author than from quotes, paraphrases, and summaries of other sources. signal phrase : a phrase that introduces outside sources material that will be quoted or paraphrased

How to Teach Synthesis Thinking in High School English

Over the course of a school year, one of my goals is to move my sophomores toward synthesis thinking. CCSS.ELA.R.7 and R.9 require synthesis thinking. Bloom’s Taxonomy also moves students toward synthesis as a means of achieving creation. As we enter second semester, it’s about time for my students to begin making the move from analysis to synthesis. Here’s how I know students are ready to make the move:

Now, I have an awesome English I team that helps students focus on these four aspects of writing. This means that when students come to me as sophomores, they have a strong foundation in analytical thought. After a semester, we’re usually ready to move into synthesis thinking. And that’s what we’re talking about today.  This post this post may contain affiliate links . Please read the Terms of Use . Choose Texts ThematicallyIn preparing to introduce students to synthesis thinking, it’s important to carefully select texts that touch on complementary subjects or topics. Here are some ideas for choosing texts that lend themselves to synthesis: First, look for a shared symbol .

Secondly, look for a similar subject or theme .

Thirdly, look for a shared historical or cultural perspective.

Fourthly, consider an in-depth author study to track an idea and its development across multiple texts.

Explicitly Introduce Synthesis“Synthesis” is a tier-two vocabulary term. In different contents, the definition may vary. However, at its core, synthesis is always about creation regardless of content area. Students draw on a variety of sources and ideas to arrive at a new understanding. To help students approach synthesis, I begin with some inquiry-based learning.

Develop Synthesis-Style PromptsWhen approaching synthesis writing, students often want to compare and contrast texts. While compare/contrast may be a great way to begin analysis, synthesis resists purely binary thinking. For teachers, this means designing prompts that do not lend themselves purely to compare/contrast-style thinking. Here are some stems to help design synthesis-style writing prompts:

Practice and Refine with FeedbackBecause synthesis requires a different lens, students do not magically arrive at synthesis thinking or writing on the first try. Instead, synthesis, like most skills, requires cycles of practice and feedback. It’s also important to note that synthesis and analysis are closely related. They complement one another. Before students can successfully synthesizes across texts, they must also be able to analyze texts. Analysis feeds synthesis, and synthesis leads to new analysis. Working across different media is another great way to practice synthesis and analysis. CCSS.ELA.RL.7 explicitly challenges students to work across media and formats. Of course, teachers often practice this with film representations of literary works, but artwork can also be a great tool to help students synthesize. Here are some options for visualizing synthesis:

How do you help your students work on synthesis thinking? Let us know in the comments!  Read these posts next... Professionalism: 1 Topic I’m No Longer Teaching in HS ELA 15 LGBTQ+ Titles To Make Your Classroom Library More Inclusive 6 Favorite Reading Strategies I Love for High School ELA 7 Powerful Speeches for Teaching Rhetorical Analysis in ELA Let's Stay in TouchJoin Moore English  Have a language expert improve your writingRun a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

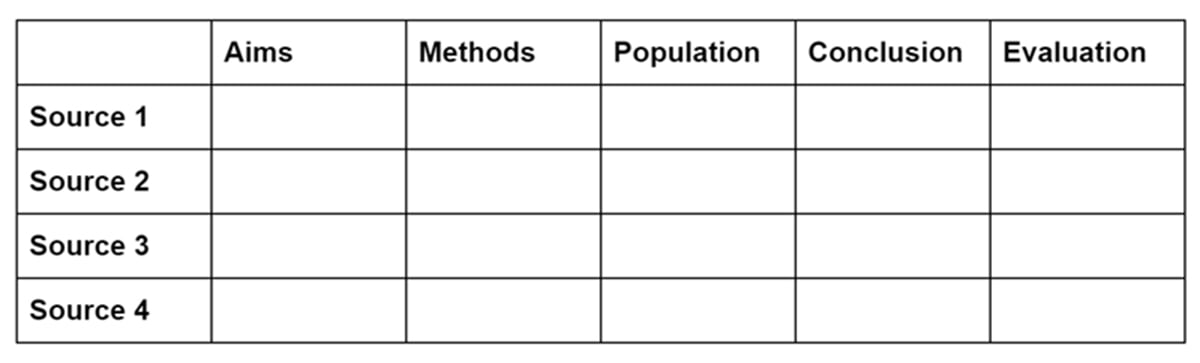

Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis MatrixPublished on July 4, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023. Synthesizing sources involves combining the work of other scholars to provide new insights. It’s a way of integrating sources that helps situate your work in relation to existing research. Synthesizing sources involves more than just summarizing . You must emphasize how each source contributes to current debates, highlighting points of (dis)agreement and putting the sources in conversation with each other. You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field or throughout your research paper when you want to position your work in relation to existing research. Table of contentsExample of synthesizing sources, how to synthesize sources, synthesis matrix, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about synthesizing sources. Let’s take a look at an example where sources are not properly synthesized, and then see what can be done to improve it. This paragraph provides no context for the information and does not explain the relationships between the sources described. It also doesn’t analyze the sources or consider gaps in existing research. Research on the barriers to second language acquisition has primarily focused on age-related difficulties. Building on Lenneberg’s (1967) theory of a critical period of language acquisition, Johnson and Newport (1988) tested Lenneberg’s idea in the context of second language acquisition. Their research seemed to confirm that young learners acquire a second language more easily than older learners. Recent research has considered other potential barriers to language acquisition. Schepens, van Hout, and van der Slik (2022) have revealed that the difficulties of learning a second language at an older age are compounded by dissimilarity between a learner’s first language and the language they aim to acquire. Further research needs to be carried out to determine whether the difficulty faced by adult monoglot speakers is also faced by adults who acquired a second language during the “critical period.” Scribbr Citation Checker NewThe AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

To synthesize sources, group them around a specific theme or point of contention. As you read sources, ask:

Once you have a clear idea of how each source positions itself, put them in conversation with each other. Analyze and interpret their points of agreement and disagreement. This displays the relationships among sources and creates a sense of coherence. Consider both implicit and explicit (dis)agreements. Whether one source specifically refutes another or just happens to come to different conclusions without specifically engaging with it, you can mention it in your synthesis either way. Synthesize your sources using:

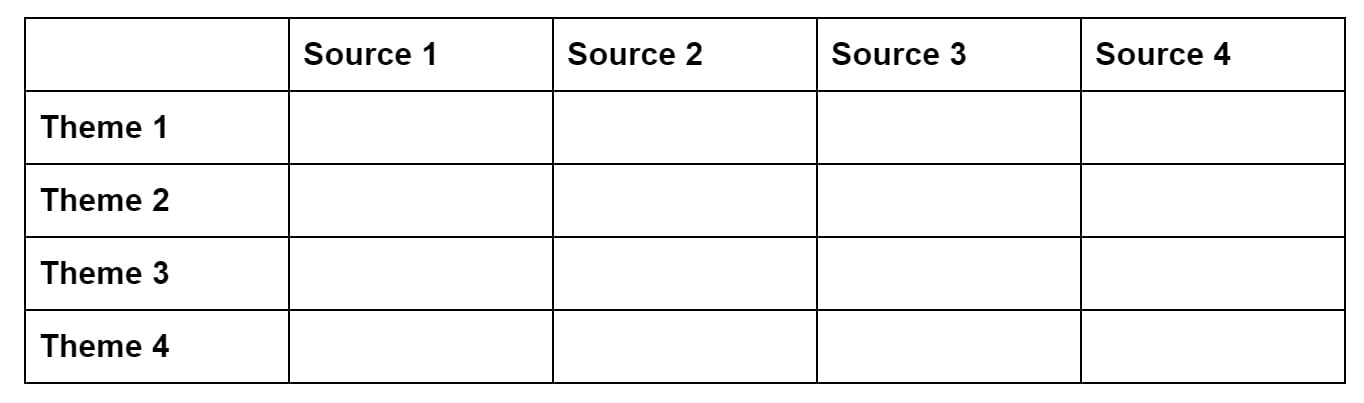

To more easily determine the similarities and dissimilarities among your sources, you can create a visual representation of their main ideas with a synthesis matrix . This is a tool that you can use when researching and writing your paper, not a part of the final text. In a synthesis matrix, each column represents one source, and each row represents a common theme or idea among the sources. In the relevant rows, fill in a short summary of how the source treats each theme or topic. This helps you to clearly see the commonalities or points of divergence among your sources. You can then synthesize these sources in your work by explaining their relationship.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Plagiarism

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.Synthesizing sources means comparing and contrasting the work of other scholars to provide new insights. It involves analyzing and interpreting the points of agreement and disagreement among sources. You might synthesize sources in your literature review to give an overview of the field of research or throughout your paper when you want to contribute something new to existing research. A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question . It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge. Topic sentences help keep your writing focused and guide the reader through your argument. In an essay or paper , each paragraph should focus on a single idea. By stating the main idea in the topic sentence, you clarify what the paragraph is about for both yourself and your reader. At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises). Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text. The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago . Cite this Scribbr articleIf you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator. Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix. Scribbr. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/synthesizing-sources/ Is this article helpful? Eoghan RyanOther students also liked, signal phrases | definition, explanation & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc., get unlimited documents corrected. ✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Synthesis writingResource type.  AP Language Essay Writing Unit Rhetorical Analysis, Argument & Synthesis AP Lang Title: Synthesis Essay Writing Unit: 14 Argument Essays for Engaged Learning Synthesis and Argument Writing : Does a #hashtag create real social change? American Dream Unit: Literature, Film Studies, Poetry, & Synthesis Essay Writing Synthesizing Texts: Synthesis Reading and Writing Lesson - Digital Synthesis and Argument Writing : Is True Love Fantasy or Destiny? Synthesis and Argument Writing : Is it ever okay to fail? Synthesis and Argument: Holiday Prompt for Essay Writing or Socratic Seminar Writing Conclusions Unit | Summarizing | Synthesizing | Sentences & Paragraphs AP Language & Composition - Mastering the Synthesis Essay Workshop Writing Unit Synthesis and Argument Writing : What is Happiness and is it Important? Thematic Unit: Immigration & The American Dream | Lit. & Synthesis Essay Writing RESEARCH SYNTHESIS ESSAY Writing Introductory Lesson Handouts Google Classroom Synthesis and Argument Writing : Are Creativity and Imagination Important? Muckraking & Investigative Journalism Unit - Synthesis & Research Writing Unit Distance Learning - The Synthesis Writing Process: College Ready Writing Writing a Synthesis Essay; Thesis for Synthesis Paper PPT Fairy Tales: Writing a Parody - Common Core/ Synthesis Activity AP Language & Composition - Synthesis Essay Writing Practice & Remediation Unit Synthesis Writing Unit: Should We Ban Plastic Straws? Digital Distance Learning Synthesis Writing Units High School ELA Curriculum: Nonfiction, Poetry, Fiction Writing the Synthesis Essay for AP Lang: Sentence Frames Writing Synthesis Lesson Bundle (Slides, Handout/Notes, & Practice WS) *DIGITAL*

5 Fantastic Strategies for Synthesizingby Erin | Nov 7, 2019 | Reading , Strategies  In order for a reader to be able to read and understand a text there is a great deal of work that they must do in their head. As shared in The Importance of Strategies , readers use a variety of strategic actions and strategies to process what they are reading. Synthesizing is one of twelve strategic action we will explore in this Strategic Action Series . This post may contain affiliate links that earn me a small commission, at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products I personally use and love, or think my readers will find useful. Visit my disclosure statement for more information. Strategies Change Over TimeWhen young children begin reading, they may use very simple strategies like memorizing or remembering the words in a story and reciting them as they see the pictures. As they learn more about letters, words, and books, they will begin using strategies like:

As young readers have more and more time to read and experience books, they develop their ability to use more sophisticated strategic actions as they read. IMPORTANT REMINDERIt is important to note that readers use strategic actions simultaneously. Unfortunately, many children view them as separate actions or even as their goal of their reading. This may be the case if you’ve ever heard your child say, “This week I am inferring.” This happens when strategies are talked about in isolation or if your child does most of their strategy work with worksheets. Even though we may attempt to strengthen a strategic action by talking about it in isolation, it is always important to remind your child that they use many strategic actions and strategies to understand what we are reading. Here is an example shared by Fountas and Pinnell in Guided Reading (2e)

Even though these actions are listed in a sequence, many take place simultaneously. Our brains can work so quickly and can do such much. Now let’s take a look at Synthesizing, a strategic action identified by Fountas and Pinnell ( Literacy Continuum , Expanded Edition, 2017).  SynthesizingReaders are continually encountering new information and ideas from texts. It is important for them to incorporate new information they gain from the text with they already understand and know. Incorporating this new knowledge with their existing knowledge helps readers think deeper, understand more perspectives, and gain understanding of experiences that they cannot directly experience. Check out the Reading Level Specific Posts to see questions you can ask or prompts you can give to support your child’s use of this strategic action.5 fantastic strategies to encourage synthesizing, 1. look for patterns with characters. Great for Reading Levels H-M Strategy Steps

You can prompt your child to think about the characters by asking the following questions:

2. Look for Repeating Words in NonfictionGreat for Reading Levels A-M

You can prompt your child to look for patterns in nonfiction by asking the following questions:

3. Pay Attention to Unusual BehaviorGreat for Reading Levels N and up Strategy Steps

You can prompt your child to pay attention to a character’s behavior changes by asking the following questions:

4. Going Beyond the TopicGreat for any Reading Levels M and up

Example: In Face to Face with Lions the main topic is Lions.

Example: Face to Face with Lions is about the importance of lions and how humans are impacting their survival. You can prompt your child to synthesize elements of the text by asking the following questions:

5. Nonfiction StructuresGreat for Reading Levels M and up

This strategy works if your child is familiar with nonfiction text structures:

You can prompt your child to identify the structure by asking the following questions:

Check out these posts for more strategies to support strategic actions:

Latest posts by Erin ( see all )

Please follow & like us :)Recent Posts

Information Literacy Resource BankSynthesis activity. This activity asks students to write a paragraph using information, evidence, or opinions from a selection of different sources. The aim is to help students develop their skills in synthesising information in order to support their arguments.  No comments. Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The SJT Clubs Are Now Open! Learn More Here! Susan Jones Teaching Teaching Resources Synthesizing Activities for First and Second GradeSusan Jones June 7, 2019 4 Comments This post may contain affiliate ads at no cost to you. See my disclosures for more information. When we teach students to synthesize, we let them know that they are combining what they already know with new information they learn from the text. As we do this, our thinking changes and grows! It’s important to teach students not to just repeat back what they’re learning. Instead, we want our students to realize that they’re actually processing the new information through synthesis. I wanted to share a few activities, book recommendations and ideas to help students practice synthesizing in first and second grade. LOOKING THROUGH BINOCULARS:When first teaching students about synthesizing, I really emphasize that we base our thoughts off what we know at the time. As we learn more information and gain more personal experiences in life, our thinking grows and changes. This introductory activity relates to the binoculars metaphor and has students thinking about what they see in each photo. We start with a zoomed in portion of the photo and share what we think the photo is. What is the subject here? What is happening in this photo? Why do you think that? Then, I let students know this was only a small portion of the bigger picture. So we take a step back and ask ourselves: What do we think is going on in the photo now? Has our thinking changed at all since the last picture? Why or why not? Lastly, we repeat those questions with the third and final photo. What new perspective have we gained by learning more information and seeing more of the big picture?  STICKY NOTE SYNTHESIZING:Debbie Miller describes synthesis as ripples made by throwing a rock in a pond. The first circle is our initial thinking. As we read and learn more information, our thinking expands and grows bigger, like the ripples in a pond. Using this model, I like to model synthesizing a text using this type of interactive anchor chart. I simply stop throughout different portions of the text and write down my thoughts (and subsequent changing thoughts) on a sticky notes and model putting them in different areas of the ripple pond (or bullseye model). The innermost circle is reserved for my initial thoughts/predictions based on the beginning of the book. Throughout the middle of the story, I will stop and add more of my thoughts as they change or as I gain new information. At the end of the story I will clarify anything I’ve learned add that newly gained information to the last ring.  If you’re looking for some great books for synthesizing here are a few of my favorites (affiliate links):  STOP & SYNTHESIZE:When I practice synthesizing with my students, I really let them know that this is when we are putting everything we’ve learned together. We are making inferences, we are using our schema, visualizing, etc. to gain a better understanding of what is happening in our stories. As we continue to read and use our skills, we synthesize and make sense of the story. Our thoughts change as we read more. You can use any of the books I previously mentioned, but I also wrote 4 short stories with stopping points for students to stop and synthesize what they’ve learned so far:  All of these passages, activities, and recording sheets (and much more) are included in my Comprehension Strategies that Stick unit below:  Pin to remember:  You may also enjoy these posts... Reader InteractionsJuly 1, 2019 at 2:57 am I love this activity and will use this with my first graders this year. Love your blog! Thank you so much for your ideas! September 23, 2019 at 10:42 pm love your stuff November 15, 2020 at 7:06 pm January 23, 2022 at 9:54 pm Leave a Comment Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .  Free CVC Word Mapping MatsSign up for my free email newsletter and receive these free CVC Word Mapping Mats to help with your next lesson plan! Check out these popular reading resources!We have loads of great reading resources over in the shop. Here are just a few I pulled together for you!  Blending Cards for a Phonics Blending Drill Decodable Phonics Comprehension Passages (BUNDLE) | DIGITAL & PRINTABLE Decodable Sentences: literacy intervention pages Phonics Games for 1st Grade: Print, Play, LEARN!Hello friends. Welcome to Susan Jones Teaching. When it comes to the primary grades, learning *All Things* in the K-2 world has been my passion for many years! I just finished my M.Ed. in Curriculum and Instruction and love sharing all the latest and greatest strategies I learn with you through this blog and my YouTube channel! I hope you'll enjoy learning along with me :) More About Me

What is Synthesis? Choosing High-Interest Topics Gather Multiple Sources Stating a Clear Objective and Task

Model Critical Reading The Secondary English Coffee Shop

Popular Posts Blog Archive

Grab Our Button © 2015 The Secondary English Coffee Shop . Ashleigh Template designed by Georgia Lou Studios All rights reserved. Customised by A Little Peace of Africa  Looking for The Read Aloud Library? 📖 LOGIN HERE

Shop ResourcesNovember 5, 2022How to teach synthesizing: helpful books and lesson ideas. An important component of reading comprehension is the ability to synthesize or draw from multiple sources to gain new information. If you teach reading strategies , chances are you’ve heard this term before, but what exactly does it mean for our young readers? And how can you help students learn this skill? Learning how to teach synthesizing in a way that young readers understand can be tricky. Figuring out how to teach synthesizing is hard because it can feel like an abstract concept for our younger students. To keep it simple for them, I like to tell them that synthesizing is when your thinking changes while reading a book. You may think one thing based off the cover and first few pages of the book, but as you keep reading, you realize that what you originally thought might not be correct and you need to change your thinking.  Why Synthesizing is ImportantIn reading, we teach students to synthesize because we want them to develop a deep meaning of the text and truly understand what they are reading. Synthesizing requires students to use many skills while reading like their schema, what is happening in the story, growing knowledge of characters and events, and using new information they read. Synthesizing is a key component of critical thinking, which is why it’s so important for students to be able to synthesize. It helps students think deeply about the information they’re learning. When students can synthesize while they read, it helps prepare them to synthesize in many other subject areas later. Introducing SynthesizingI like to first introduce synthesizing outside of reading. First, find a picture of something interesting. In my case, it was me bathing our dog outside. Show students one part of the picture (I showed my dog’s face) and ask them what’s happening in the picture. Then, I’d uncover a little bit more (me squatting down next to my dog) and ask students what they think is going on. Finally, I’d show the whole picture of me bathing my dog. We’d discuss how their thinking changed as they got more and more information. At first students may have though that it was just a picture of my dog. Then, they thought it was me and my dog. Finally, they thought it was me giving my dog a bath. With background knowledge and more information, their thinking changed. Books for Teaching SynthesizingAll of these books easily lend themselves to synthesizing and are engaging for kids. They are great for kindergarten through second grade readers.

Sentence Stems for SynthesizingEquipping readers with the right vocabulary will help them learn better and faster. We want them to be able to talk about their thinking accurately, so we have to show them how to explicitly. Here is a simple set of sentence stems you can use to help your students talk about synthesizing:

Taking the Guesswork Out of How to Teach SynthesizingIf you want to take all of the guesswork out of planning how to teach synthesizing, this is the resource for you! The Let’s Synthesize Interactive Read Aloud resource has 7 days of lesson plans with synthesizing reading activities that are perfect for the first grade or second grade classroom.  Inside you’ll find:

You can get your Let’s Synthesize resource HERE to be all set for teaching this important reading strategy.  Watch for the moments when your students “get it”. They’re some of my favorite ones! Once they do understand the concept of synthesizing, get ready to take them deeper into their thinking. Happy Teaching,

EASILY PLAN YOUR K-2 READING SMALL GROUPS Want to use the latest research to boost your readers during small groups? This FREE guide is packed with engaging ideas to help them grow!  Hi, I'm AmandaI’m a K-1 teacher who is passionate about making lessons your students love and that are easy to implement for teachers. Helping teachers like you navigate their way through their literacy block brings me great joy. I am a lifelong learner who loves staying on top of current literacy learning and practices. Here, you’ll find the tools you need to move your K-2 students forward! Reading CVCe Words | CVCe Worksheets for Science of Reading Centers Reading Beginning Blends and Ending Blends CenterYou may also enjoy....  Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

©2021 MRS RICHARDSON'S CLASS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.Site by ashley hughes.  Which type of professional development interests you?Literacy training videos, online workshops.  What are you looking for?Privacy overview.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS