Bondwine Books

The Fiction of Tom Simon & the Lies of H. Smiggy McStudge

- Foolishness

Creative discomfort and Star Wars

The fact is that this script feels rushed and not thought out, probably because it was rushed and not thought out. —‘Harry S. Plinkett’ (Mike Stoklasa) They’re already building sets. God help me! I’m going to have to start this script pretty soon. —George Lucas

It is not actually true that ‘all good writing is rewriting’. It would be nearer the truth to say that all good ideas are second ideas — or third, fourth, or 157th ideas. Writers are notoriously divisible into two warring camps, ‘outliners’ and ‘pantsers’. One of the most common triggers for a rewrite happens when you come up with a brilliant new idea halfway through a draft — and that idea makes a hash of everything you have already written. This, in the war of the writers, is a powerful weapon against the pantsers.

Jeff Bollow, for instance, in his book Writing FAST , recommends that you get your ideas right first, and write the draft later; but he also tells you never to use the first idea that comes to mind, for that only trains your mind to be lazy. If you do your brainstorming properly, and don’t start actually writing until your ideas are solid, you are much less likely to have to tear up a draft and start over. John Cleese touched on the same point in his 1991 talk on creativity :

Before you take a decision, you should always ask yourself the question, ‘When does this decision have to be taken?’ And having answered that, you defer the decision until then, in order to give yourself maximum pondering time, which will lead you to the most creative solution. And if, while you’re pondering, somebody accuses you of indecision, say: ‘Look, babycakes, I don’t have to decide till Tuesday, and I’m not chickening out of my creative discomfort by taking a snap decision before then. That’s too easy.’

That creative discomfort can make all the difference between great writing and dreck. One could argue the point endlessly, for there are examples to the contrary — snap decisions that turned out to be brilliant, slowly gestated ideas that still turned out useless. I would maintain that such cases are outliers: so much depends on the talent of the individual writer, and on sheer luck. What we want here is a controlled experiment. We could learn a great deal by taking the same writer and putting him through a series of similar projects. In half of them, he would have all the time he wanted to brainstorm, to throw away ideas when he came up with better ones, to tear up drafts, to indulge his creative discomfort. In the other half, whenever he had to make a decision, he would simply take the first workable idea that came to mind. Unfortunately, we can’t hire a writer to go through such an experiment. Fortunately, the experiment has already been made. The writer’s name was George Lucas.

Michael Kaminski’s Secret History of Star Wars (both the book and the website ) describes the experiment and its results in fascinating detail. For my present purpose, however, I will take only a few points from Kaminski’s (and Lucas’s) work, specifically about the writing process: two from the ‘Original Trilogy’, and three from the prequels. To begin, then:

In the early 1970s, fresh off the unexpected success of American Graffiti, Lucas decided to try his hand at a rollicking space opera in the style of the old Flash Gordon serials. Thwarted in his attempt to buy the film rights to Flash Gordon itself, he began scribbling names and ideas on notepads, trying to come up with a space opera all of his own. He read and reread pulp science fiction stories obsessively, especially E. E. ‘Doc’ Smith’s Lensman books. After a million and three false starts (this number has been verified by Science), he sent his agent a very brief synopsis called The Journal of the Whills, which began with the following helpful sentence:

This is the story of Mace Windy, a revered Jedi-Bendu of Opuchi, as related to us by C. J. Thorpe, padawaan learner to the famed Jedi.

The agent, Jeff Berg, reacted approximately as follows: ‘Mace Who, a revered What of Where, as related by the Whatsit learner to the famed How’s That Again? You gotta be kidding me!’ He gently advised his client to rewrite the synopsis in English. This was not an easy request for the young Lucas to fulfil. From beginning to end, the Star Wars saga — as it would eventually be called — is filled with characters who speak no English at all. But he did approximately comply, and eventually came up with a treatment for a project called (at this point) The Star Wars. He lifted most of the story from Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress. As in the Kurosawa film, the lead characters are a general and a princess, who are trying to escape the clutches of a wicked and decadent empire during a period of civil war. The general’s name is Luke Skywalker.

It took four years to turn this sketchy treatment into a movie. Along the way, Lucas put the script through four full drafts and innumerable small revisions. Seldom has a script been so struggled over. In some versions, the hero’s name is not Skywalker but Starkiller. (Sometimes both names, confusingly, are used in the same draft for two different characters.) The Jedi were written out of the second draft entirely, and then put back into the third. ‘The Force’ (sometimes called ‘the Force of Others’) is sometimes a purely mental power, somewhat similar to hypnosis, sometimes a physical super-power accessible to a trained mind. Han Solo was conceived as a repulsive green alien; then the green alien was renamed Greedo, and Han Solo (now a human) killed him.

Lucas, in those days, had a well-justified lack of confidence in his writing skills. Fortunately, he had continual recourse to help from better qualified people — Gary Kurtz, Francis Ford Coppola, and his wife Marcia, among many others. Important bits of the script were reworked on the set by the actors. Harrison Ford famously told Lucas: ‘George, you can type this shit, but you can’t say it’ — and then turned it into something that he could say. Lucas borrowed lines and motifs wherever he could, and when he could not borrow, he stole; but he remained in control at all times, and gradually shaped this magpie’s collection of material into a classic fairy tale — a fairy tale in space.

The original Star Wars became the surprise blockbuster of 1977, the biggest pop-culture phenomenon since Beatlemania. (I first saw it, as a boy of ten, at the old North Hill cinema in Calgary. In addition to the title, the marquee carried a shameless political plug: ‘R2-D2 FOR MAYOR’.) Lucas’s share of the profits was enough to bankroll a sequel without any financial input from a studio. Writing and directing the first film had nearly killed him; this time he hired help. The sequel was directed by Irvin Kershner, who would leave his own imprint on the story; but we are concerned here with the script. For that, Lucas wanted an honest-to-goodness, old-school space opera writer. A friend suggested Leigh Brackett: ‘Here is someone who wrote the cantina scene in Star Wars better than you did.’ Kaminski describes what happened next:

[Lucas] contacted the elderly Brackett, who was living in Los Angeles at that time, and asked her to write Star Wars II. ‘Have you ever written for the movies?’ Lucas asked her. ‘Yes, I have,’ Brackett replied simply — she began recounting her credits, which included Rio Bravo, El Dorado and The Big Sleep, co-written with William Faulkner, the Nobel-prize-winning novelist. An awkward silence followed. ‘Are you that Leigh Brackett?’ Lucas gasped. ‘Yes,’ she replied. ‘Isn’t that why you called me in?’ ‘No,’ Lucas said, ‘I called you in because you were a pulp science fiction writer.’

The Empire Strikes Back took less reworking than the original Star Wars. Partly this was because most of the principal characters had already been established, and much of the world-building was already worked out. Also, Leigh Brackett was simply a much more accomplished writer than Lucas. Unfortunately, she died shortly after completing the first draft, and Lucas was once more thrown upon his own resources. He did a very rough second draft — more like a treatment based on Brackett’s first draft, incorporating some of the changes he wanted to make — before turning the job over to Lawrence Kasdan, whose work on Raiders of the Lost Ark had thoroughly impressed him.

The general sequence of the script remained much the same in each version, starting with the rebels on the ice planet, then splitting up the cast as Luke went for his Jedi training, and ending with the climactic encounter with Darth Vader. The love story between Han and Leia was developed — here, again, Lucas stole what he could not borrow — with dialogue lifted from, of all places, Gone With the Wind. Here is a bit of dialogue from the book, between Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara:

‘I’ll bet you a box of bonbons against—’ His dark eyes wandered to her lips. ‘Against a kiss.’ ‘I don’t care for such personal conversation,’ she said coolly and managed a frown. ‘Besides, I’d just as soon kiss a pig.’ ‘There’s no accounting for tastes and I’ve always heard the Irish were partial to pigs — kept them under their beds, in fact. But, Scarlett, you need kissing badly.’

A good thief steals without getting caught; a great thief doesn’t care whether he is caught, for he makes the stolen goods his own. Somewhere along the way, someone — Lucas, Brackett, Kasdan, or Kershner — came up with a change that turned this rather arch dialogue into a defining moment for the characters and a classic scene in cinema:

Han Solo: Afraid I was gonna leave without giving you a goodbye kiss? Princess Leia: I’d just as soon kiss a Wookiee. Han Solo: I can arrange that. You could use a good kiss.

This was all very well; and between Kasdan’s snappy dialogue and Kershner’s mastery of emotional range as a director, the Han–Leia element of the story blossomed spontaneously. But that was only a subplot. A terrible shadow hung over the main plot: the shadow of Luke’s father.

Father Skywalker had actually appeared in one draft of the original Star Wars script, before Lucas decided that he was already dead when the story began. Now he somehow had to be worked into the sequel. One could hardly film a dramatic scene about a man who had been dead for twenty years. That meant that the other characters had to talk about him. ‘Show, don’t tell’ is a much abused bit of advice, but in drama and film, it really does apply. Showing saves time, and uses the full visual effect of the medium to convey an emotional impact that mere talking can never match. The conflict between the good Jedi, represented by Father Skywalker, and the evil Sith, represented by Darth Vader, could not easily be shown. The only way was to bring in Father Skywalker’s ghost along with Obi-Wan’s, as Leigh Brackett did in her first draft; and that, clearly, was one ghost too many.

Inspiration struck.

Unless Father Skywalker and Darth Vader were the same person.

It was a brilliant idea: simple, dramatic, crackling with emotional force. It simplified the story, got rid of the extra ghost, and gave the whole script a powerful new unity. Before the change, Luke was separated from Han and Leia, not just physically, but thematically. He was going off to Dagobah to follow in his father’s footsteps; Han and Leia were fleeing to Bespin to escape from Vader’s fleet. But if Luke’s father was Vader, that tied their motives together and welded the plot into a single, consistent emotional arc.

This is the kind of idea that is worth tearing up a draft for. From the original Journal of the Whills, it took Lucas five years to come up with it. Fortunately, this change did not require any changes to the first film — though it made Obi-Wan a liar, a fact for which his ghost would offer a lame excuse in Return of the Jedi. (He would have done better to admit that he was afraid to tell Luke too much of the truth.) It turned the second film into a tour de force. And it set up the conditions and the conflicts for the third film. What’s more, it did not require any significant change to the scene-by-scene structure of Leigh Brackett’s first draft; it only gave the scenes a new and deeper meaning. Unlike the four major drafts of Star Wars, which changed the original story beyond recognition, the redrafts of Empire only added strength to a structure that was already sound.

When it became clear that Star Wars was a hit, and sequels would be called for, Lucas gave out that it was the first episode in a twelve-part series that he called ‘The Adventures of Luke Skywalker’. In 1979, this idea disappeared down the memory hole. The first film became Episode IV, with the subtitle ‘A New Hope’ — which was added to the opening crawl for the theatrical re-release in 1981. Star Wars became the overall series title — a sound commercial decision, given the immense value of the brand name Lucas had created. The number of films in the projected series was cut down to nine. In a particularly Orwellian move, Lucas published the ‘official’ screenplay of Star Wars in 1979, labelled ‘Episode IV: A New Hope’, and incorporating many changes made between the fourth draft and the final movie; but he let on that this was the actual fourth draft, as written in 1976. It was the first of many attempts he would make to rewrite his own history. ‘Greedo shot first’ has a long lineage, if not an honourable one.

The Empire Strikes Back, as it turned out, was a brilliant movie; the trouble was that Lucas didn’t want brilliance, didn’t particularly understand it, and had not much idea how to make use of it. All along, he had wanted Empire to be short, quick-moving, and upbeat, like its predecessor; he was unhappy that Kasdan and Kershner turned it into something slower and grander and more introspective, and furiously angry with Kurtz for letting them go far over budget to do it. The immediate upshot was that Kurtz was replaced: Howard Kazanjian was hired to produce Return of the Jedi, in the hope that he would prove more obedient.

Jedi begins the downward spiral of the Star Wars sequels. Already we begin to see Lucas losing patience with his creative discomfort, taking snap decisions, seeking the easy way out of plot difficulties. He had already had the idea that Luke would have a sister, another potential Jedi; she appears under the name of Nellith in Brackett’s draft. That, and Yoda’s cryptic statement in Empire, ‘There is another,’ seem originally to have been intended as setup for Episodes VII through IX — and to heighten the immediate tension, by suggesting that Luke himself was expendable after all, and might not survive. But by the time he began work on Jedi, he was growing sick of the whole Star Wars phenomenon; he no longer had any intention of making six more episodes. So he took the easy way out by making Leia Luke’s sister, and also the ‘other’ that Yoda spoke of. There was nothing in Leia’s character to suggest a potential Jedi; but she was already there, and indeed, the only significant female character in the series. It was simply easier to write her as the ‘other’ than to introduce a new character for the purpose.

However, Jedi still works reasonably well. It carries on with the momentum generated by Empire, somewhat diminished by disco dance numbers and burp jokes, and by the need to find screen time for far too many Ewoks. Kershner and Kurtz were gone, but Kasdan was still on board as co-writer, and he outdid himself in developing the final three-way confrontation between Luke, Vader, and the Emperor. Lucas’s snap decisions, at this stage, were all about tying up loose ends of subplots; they could not detract from the main story of the film.

Let us skip forward a bit.

Fifteen years later, Lucas was hard at work on Episode I, to which he gave the puzzling title, The Phantom Menace. This time, he was the sole (credited) screenwriter, as well as the director, executive producer, chief cook, bottle-washer, studio mogul, greenlighter, Howard Hughes, and Citizen Kane. Unlike Empire and Jedi, the new script was his baby, solely — and he had not improved as a screenwriter with the years. When Kasdan was brought in to rewrite the second draft of Empire, he was incredulous at the sheer badness of the dialogue; he had not heard the inside story about all of Lucas’s helpers on the original Star Wars script. This time, Lucas’s inadequacies would be exposed to the world’s naked and unforgiving gaze.

I will pass over the inadequacies of the dialogue in the prequels, except to point out that with a very little more creative discomfort, Lucas could have hired a script doctor — a younger equivalent of Kasdan — to go over the lines and make them read more naturally. Lucas’s dialogue is too literal, too ‘on the nose’: he never learnt the discipline of trusting his actors to act. Things that could be better conveyed by indirection — an elliptical remark, delivered with the right tone and facial expressions — were stated baldly, in terms that left the actors very little to do. Partly, as I have heard, this was done to make the script easier to translate into foreign languages, in which the subtleties of the original might be lost. If that is so, it would have done no harm to save Lucas’s version as a master script for translators, and then hire a script doctor to translate it into English, inserting subtleties as required. But nobody seems to have thought of doing this.

What made Phantom so disappointing to grownups, and especially to those with fond memories of the characters and lines from Empire and Jedi, was that apart from the brilliant CGI work, it seemed to be built out of Tinkertoys. Every character and every action were obviously designed to get from one plot point to the next with a minimum of creative effort, and most of the plot points were apparently designed to lead into the visual set-pieces — the pod race, the battle on Naboo, and the utterly ridiculous scene in which the nine-year-old Anakin blows up the droid control ship with a one-man fighter that he doesn’t even know how to fly. The cumulative effect is bizarre: you might say that the picture had the brush-strokes of a Turner landscape, but the composition of a connect-the-dots puzzle.

Lucas did not write the Phantom script quickly; but he had many other cares, thanks to the multitude of hats he was wearing, and the script shows abundant signs that he skimped on the work. I will take one case as a sufficient example: the dire origin story of C-3PO.

Let us begin with the obvious. Young Anakin claims that he built Threepio to help his mother around the house. His mother, mind you, is a slave: she is supposed to be the help, not receive the help. This raises an awkward question. Droids are the accepted substitute for slave labour in the Star Wars universe. Why, then, does a scrap dealer, with a shop full of robots in assorted states of repair, need an organic slave as well as all his mechanical ones? It is never made very clear what kind of work Shmi Skywalker does for her master; her only function in the plot is to be owned, and to make her son grieve when he is separated from her. One wonders why she would be allowed to have a robot to help her at all. Why not just have the robot, and dispense with the human slave?

Suppose we let all this pass. Why, then, did Anakin build a protocol droid? Surely, if your mother were a maid-of-all-work and you wanted to build a machine to help her, you would not immediately think of making a slow-moving mechanical man who was ‘fluent in over six million forms of communication’. Owen Lars, in the original Star Wars, had no need for an interpreter; he bought C-3PO from an obvious fence, presumably at a bargain price, to talk sense into his moisture vaporators. But apparently Shmi, a scrap dealer’s slave on the same unimportant desert world, does need a translator; needs one so badly that her son decides to make her one out of spare parts as the ideal gift. It does not begin to be plausible; it hardly even pretends to be.

But these are side issues. The crucial fault, of course, is that young Anakin (as we, the audience, know in advance) will turn out to be Darth Vader; and yet, when they meet face to face after a lapse of many years, neither will recognize the other. Lucas made an attempt to save the appearances in Episode III, where Threepio’s memory is wiped. Even devoted fans of the series admit that this is clumsy. So why was it done this way at all?

The only answer appears to be that Lucas wanted C-3PO in all six episodes, and he needed a way to shoehorn him into Phantom — a film that otherwise had no need of him. So he gave him a cameo in the first place he could think of. This, surely, was a case that cried out for some creative discomfort. Lucas settled for a lazy idea when it would have been much easier, and immeasurably better artistically, to sweat over the problem until he came up with a good idea.

Before I sat down to write this essai, I spent a few minutes brainstorming for ideas on how better to introduce Threepio in Episode I. By your leave, I will offer the one that seemed to work best — the one that solved the most problems in the story. I don’t claim that it is the best possible idea; it is merely the most interesting of several that occurred to me when I troubled to think about the problem. Here it is:

What if C-3PO was a protocol droid working for the Trade Federation? We see an almost identical droid (silver, not gold) in the opening scene aboard the Trade Federation flagship; it’s the one that serves drinks to Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan while they wait in the conference room. This would improve the story in several ways. To begin with, it would give some personality to the protocol droid in the conference room — a scene that desperately needed something to make it interesting. It would give the two Jedi a better motive for going down to Naboo. Their stated motive is nonsense: you can’t warn somebody that an invasion fleet is coming by stowing away on the invasion fleet itself. But as a protocol droid, Threepio would have been a witness to the machinations that led the Trade Federation leaders to the brink of treason and open war. That information could have been vital to the Naboo side, and politically important to the Republic itself, and to the Jedi Council.

One can easily imagine the two Jedi taking Threepio by force, removing the restraining bolt that his previous master presumably gave him, and using him to bluff their way through to a shuttle that would take them down to Naboo. Threepio would likely have helped them, moved by a combination of gratitude (they set him free of the restraining bolt and some unsavoury owners) and timidity (these are, after all, Jedi, and we see them using the Force to smash droids into kindling). On Naboo he would have met R2-D2, who was assigned to the Queen’s yacht. They would have been a robotic Montague and Capulet; much could have been made of the process by which they learnt to work together, and turned from official enemies into bickering but steadfast friends.

This kind of comic relief was something Lucas knew how to write and direct; the byplay between the droids is one of the best things in the original Star Wars, and indeed they carry the action all by themselves for much of the first act. That suggests the best reason of all for introducing C-3PO this way: it would have cut Jar-Jar Binks completely out of the story. The idea of Jar-Jar was not fundamentally a bad one, but the execution was embarrassing. He introduces an element of the lowest slapstick into otherwise serious, or at least seriocomic, scenes; and Lucas simply has not got the skills to handle slapstick. Physical humour is a ‘low’ form of comedy, in that it makes few demands on the intelligence of its audience; but it requires tremendous technical skill to do properly. Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton were enormously respected by their fellow actors, who knew how hard it was to make people laugh in that way.

Episode II sees Lucas resorting to more and more implausible devices to rescue himself from his own hasty decisions. The movie scarcely hangs together at all: the characters go rabbiting all over the Galaxy on slight pretexts, and in consequence, have little time to interact with one another. What this episode should have done — what it needed to accomplish — was to show Anakin growing into an idealistic young Jedi knight, ‘the best star pilot in the galaxy’, and ‘a good friend’, as Obi-Wan called him in the original. The romance between Anakin and Padme could have been deferred to Episode III; or it could have been made a complication in the second act of Clones, a wedge that came between Obi-Wan and his apprentice.

But here again, Lucas took the easiest way out. Instead of showing us these things, he simply told us — in the most static and unconvincing way, by having Anakin and Obi-Wan reminisce about their adventures together for a minute or two in a moving lift. The adventure they alluded to would have made a splendid overture to the main story. It would have served the same function (and could have been about the same length) as the battle of Hoth in Empire or the Jabba the Hutt section of Jedi. That would have put the characters, especially Anakin, on a firm footing, and given the audience a solid impression of Anakin as a good guy. Instead, our first long look at the grown-up Anakin comes in static indoor scenes, where he paces up and down and complains incessantly about Obi-Wan to anyone who will sit still for it. He comes across as a whiny, spoilt adolescent, self-important, consumed with petty grievances, but too cowardly to complain to Obi-Wan himself. This is a disastrous error. It undermines the whole character of Anakin; we almost feel that his turning to the Dark Side is redundant. Lucas, in his own mind, firmly believed that the story arc of the prequels was about the good and virtuous Anakin being seduced by evil. But the good and virtuous Anakin only existed in Lucas’s mind. He never made it into the films.

Let us finish off with an example from Episode III: the death of Padme, which is a crucial point in the plot. We have a world in which the most hideously maimed and broken men can be put together again with prosthetic parts. We see it done with Anakin, who loses all four of his limbs, has the skin burnt off the rest of his body by hot lava — and lives. He is rebuilt into the dark and menacing form of Darth Vader. And yet Padme, having what (as far as we can tell) is a perfectly ordinary pregnancy, lying in an aseptic delivery room, surrounded by droid doctors and the best medical technology in the nascent Empire, can die in childbirth — not even from eclampsia or an infection, but simply from a broken heart. Women do die in childbirth sometimes, even with advanced medicine, and it is at least debatable that some women die of broken hearts; but never the two in combination. The presence of a newborn child concentrates the instincts and the affections wonderfully; it gives the most broken-hearted mother something to live for. Worst of all, Anakin has just turned to the Dark Side specifically to learn how to prevent Padme’s death — and yet he does absolutely nothing about it.

Once again, a few minutes’ thought suggested a number of alternatives to me; here is the one I personally like best. Lucas himself almost stumbled into it — but instead of filming it, he made it a lie told by the Emperor. When the newly built Vader takes his first lurching steps (so painfully reminiscent of Frankenstein ), he asks what has happened to Padme. ‘You killed her,’ says the Emperor. Very well: What if Anakin really did kill Padme? How would that come about?

We know that Anakin saw little of Padme during her pregnancy — the Jedi and the Emperor kept him too busy, and usually too far away. On the evidence of Vader’s dialogue in Jedi, he never knew that she was carrying twins. Let us suppose, then, that Padme is safely delivered of her two children while Anakin was away; that she knows he has turned to the Dark Side and is now the Emperor’s apprentice. What does she do? The obvious thing is to hide the children. She places Luke in the care of Anakin’s kinsman, Owen Lars — on the face of it, a fearfully stupid thing to do, for Vader knows that place all too well. But we may suppose that she works out her plan with Obi-Wan, and he chooses to go into retirement on Tattooine specifically to watch over the boy and protect him from the Empire. Then she hides Leia by having her adopted into the powerful Organa family on Alderaan.

At this point, both her children are in safe places, and all the witnesses are in hiding as well. (Except the droids in the delivery room; but she could have had their memories wiped, and we would be much more willing to accept it than we were with a known and beloved character like Threepio.) The only really dangerous witness — the first one Vader would seek out and interrogate — is now Padme herself. So she gets on her fancy ship with a skeleton crew, devoted family retainers who will join her on a suicide mission — and goes to seek out the command ship on which, even then, Vader and the Emperor are searching for her. She goes to meet her fate, and challenge it. Either the Emperor will die, and the threat will be ended, or she will die, and her children’s secret will be safe.

The final scene would be very short: it would fall like a hammer blow to the vitals. There might be a short radio conversation between Vader and Padme while her ship locks in a collision course with his. ‘I can’t let the Republic die,’ she might say. ‘ You can’t let the Jedi die, Ani. Search your feelings!’ (When you are conducting a life-or-death negotiation and every second counts, the dialogue can afford to be on the nose.) The Emperor looks on, unconcerned and sneering: he knows how strong the Dark Side is, and what chains of shared guilt bind his new apprentice to him. We see Vader on the bridge as the ship approaches in the viewport. He looks back and forth between the Emperor and his wife, indecisive — as he will one day look between the Emperor and Luke. But this time, he is not strong enough; he capitulates. At the last possible moment, he gives the weapons officer the order to open fire, and Padme’s ship is obliterated. Cut to an exterior shot of the command ship, bits of burning metal glancing off the hull. On the soundtrack, we hear Vader’s cry of loss and grief, and the Emperor’s triumphant laughter.

This scenario, or something like it, would give Padme something to do, instead of being a stereotypical damsel in distress, and dying pointlessly of a broken heart. We could believe that a firebrand like Leia could be the daughter of such a mother. (Natalie Portman could have prepared for the role by carefully watching Leia’s scenes in A New Hope, and adopting similar mannerisms.) It would set up a resonance with the ending of Episode VI. Lucas is very fond of such resonances: he exploited them incessantly, even shamelessly, in the prequels. ‘Each stanza sort of rhymes with the last,’ as he puts it. The ending of Jedi would appear in a whole new light: Vader’s second chance, which he thought would never come: an opportunity to redeem his failure when Padme needed him most. Lucas had the right idea, or part of it, when he thought of making things rhyme. But rhyme in poetry is most effective at the end of a line. The word that rhymes is also the last word.

Those, at any rate, are the ideas: they took me all of fifteen minutes’ creative discomfort — much less time to invent them than it took to write them down. I have no doubt that Lucas could have come up with better ones than these if he had seriously tried. But he was too used to making snap decisions and having them obeyed. Lucasfilm had become his perfect machine, a machine that incorporated hundreds of talented men and women in its works; a machine that would instantly do, not what he wanted done, but what he told it to do — as literal-minded as a computer. The days when he worked with equals, like Coppola, Spielberg, Kurtz, or Kasdan, were long gone; now he had only subordinates, too timid to question him, too small in stature to challenge him to do better. With such servants, his own capacity for creative discomfort atrophied and, I fear, eventually died. And to a great extent, the Star Wars prequels died along with it, leaving behind only a gigantic mausoleum of bloodless fight scenes and visual effects. They could have done so much more. They could have lived.

Thanks– that’s a lot more history of Lucas and Star Wars than I knew.

What I did know was that “A long time ago in a galaxy far far away” is brilliant, or at least solidly memorable. When the text intro for A Phantom Memory started with talking about tax policy, I knew that I was doomed to watch a much inferior movie. Lucas had somehow lost his sense of taste. Your hypothesis that he was no longer using the strategy he needed to write well is plausible.

As for a slave having a robot, we consider it normal for slaves to have tools. A much richer society might supply slaves with robots, which is not to say that the economics in the movie make sense.

Depends, too, on what kind of slave she is. Ancient Rome had educated slaves (Greeks were particularly desirable) in positions of authority; skilled craftsmen and craftswomen slaves (like potters and weavers and dancers) made money for their owners from their skills.

Shmi may not just be a maid-of-all-work; she might be quite literally in charge of running all the affairs of her master’s household, including handling elements of his business. In which case, having a droid that can speak several languages and knows the pitfalls of cultural niceties in different societies would indeed be useful for a slave dealing with customers from all over the planet and off-planet as well.

And why own a human/other organic life-form slave instead of robots? Status. If robots are common enough that every household can have one, being able to own at least one slave means you’re wealthy/successful/important enough to be A Big Deal. Think of it this way – nearly everyone nowadays can drive a car, and nearly everyone owns a car. So why employ a chauffeur to drive you? It’s a sign that you’ve made it; you’re so incredibly busy and important, you’re too busy to drive yourself 🙂

A chauffeur can also mean that your work, accomplished while he’s driving, is profitable enough to pay for his salary and more as well.

These are all very good points. The problem is that what we see of Watto does nothing to support the theory that he is a high-class slave owner with a household of other high-status biological slaves that need to be managed. He’s described as a “junk dealer”, and gives every impression of being a scrounging bastard. The fact that he owns a slave at all is pretty inexplicable.

(I had to look up Watto’s name. I’m somewhat proud of this level of ignorance of the prequels.)

You wouldn’t need other organic slaves. She would have to deal with other merchants, for instance, for all the necessities.

Exactly. Watto doesn’t have a big household, but while he’s out wheeling and dealing, somebody has to be there to answer the door and make sure nobody robs the yard, and I don’t think Watto would trust a paid employee 🙂

I was too old to really be a “Star Wars” fan when it originally came out; by then, I was in my mid-teens and already a devoted Trekkie. But I enjoyed the first trilogy of films (even though I found the Ewoks creepy with their dead, black, glassy eyes – and in hindsight, they’re a terrible omen of what is coming later with Jar-Jar Binks).

However, after all the to-ing and fro-ing about the “nine pictures made up of three trilogies” and seeming as if it would never be finished, and the fiddling around they did with the original three (special editions, more special editions, re-editing, the infamous “Greedo shot first” meddling and the updated special effects), I had no great expectations for “The Phantom Menace” and I wasn’t disappointed.

I could see he was trying for the look and feel of the old “Flash Gordon”-type serials, but it didn’t gel with the shiny new tech on-screen. I didn’t see a real connection between Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon until the death scene of the latter, which was the first time I felt emotionally involved with their characters (not the fault of the actors); Jar-Jar – well, what needs to be said about Jar-Jar at this point? – and the biggest flaw was Anakin.

Nine years old was just too young . He needed to be at least twelve, and my own opinion is that fourteen would have been a better age. No matter how whizz-bang he may be with the Force, he’s untrained in its use and a small boy (which is what he is) is just not going to be physically able to race against adults the way we saw him doing, even if it is in the most souped-up pod onworld.

It also makes Shmi weirdly negligent about letting her nine year old son head off with strange men, in the full knowledge that this is pretty much the last time she’ll ever see him again. It makes Yoda’s warnings seem more like out-of-nowhere prejudice (he’s too old to be trained?) and even more, it makes the Anakin-Padme romance just plain creepy.

I agree with your take on how Padme should have died; th e notion of death in childbed as presented is ridiculous. An alternate explanation, if we must have her dying while giving birth, is that this is the reason Jedi are discouraged from falling in love and marrying – they do literally kill their wives because the activated midichlorians in their bloodstream act like the Rhesus negative factor (hey, if George Lucas can fudge his biology, so can I!)

That at least would give us a reason the Jedi Order frown on emotional attachments and discourage Anakin from being able to fall in love and marry (other than being cold-hearted jerks), it would explain why he feels guilty and responsible for endangering her and why he’s looking to the Dark Side for a way to cure or at least prevent her death, and it would explain why a healthy woman with an uncomplicated pregnancy with access to the best medical care giving birth in a hospital environment dies in childbed (rather than ‘you killed her by breaking her heart’).

Of course, it gives the extended universe problems because of the children born there to Jedi fathers.

Well, that can be handwaved too 🙂

When you have two Jedi or when you have a Jedi who knows the precautions to take, unlike Anakin (who just went right ahead and did what he wanted), it’s a different matter.

Anyway, I’ve always thought of the movie canon as being slightly different to the Expanded Universe comics, novels, etc. (primarily because George Lucas didn’t bother making the follow-up films about What Happens Next to Luke and the rest of them, so other people invented their own take on the mythos).

Bah. The less said about midichlorians, the better.

As a friend of mine said, “it was kind of disappointing to learn that all along The Force was just germs.”

it made Obi-Wan a liar, a fact for which his ghost would offer a lame excuse in Return of the Jedi. (He would have done better to admit that he was afraid to tell Luke too much of the truth.)

I would have put Obi-Wan in the dark — at that time, he really believed that the father was dead. It would also have shown that the good guys were ignorant of stuff and so strengthened the conflict.

Knobe being sincerely mistaken would have been good for a long-running gritty intrigue series where later how and why he was misinformed would itself be a clue to something, or he would be suspected as a secret villain because of it, etc.

But for a simple trilogy with a simple mythic design, imo the ‘metaphorical truth for Luke’s own good’ fits much better — and doesn’t require Knobe to be a perfect genius saint who planned this statement in advance. In the press of the conversation when it actually happened, he’d have many feelings suggesting such a statement: not wanting to hurt Luke more than necessary, not wanting to confuse him, wanting him to abandon hope of rescuing a live, good father, wanting him to focus on defeating Vader, etc.

A human juggling these feelings might have had the metaphor flash up unexpectedly and gone with it.

Darth Vader could have told him that he killed him. Simple, neat, and efficious. You have to skip the battle with Anakin — but, heck, Vader could have thrown him the lightsaber as proof, and they could really have fought.

I think that would have been a good way to go.

I think the “true from a certain perspective” idea has potential, too; it could have been better used in the prequels, by showing Obi-wan as more devious than Lucas actually shows him. We get something like this in the Clone Wars animated movie, which in many ways was the sort of prequel that Lucas should have done: Obi-wan wins a battle by conceding it and then making the discussion of terms of surrender so long and complicated that Anakin is able to take out the other side’s shield generator. It’s not really that he lied; there was nothing left to do but surrender. He just did it in a way that would give him better chances when the battle started again. Done rightly, it’s the sort of flaw that deepens a character. Being excessively inclined to hedge one’s bets is also a good flaw for a good guy to have; it’s definitely a flaw, but is not so bad as to taint the entire character, and can even be a reason for some of their successes. (It could also have been shown as the beginning of a rift between Obi-wan and Anakin, because it’s the sort of flaw that could have led to a situation in which what Obi-wan just sees as natural caution and tact for the good of everyone, including Anakin, is seen by Anakin as outright treachery and betrayal. Lucas was perhaps trying for something like this, given some of the things Senator Palpatine says about the Jedi in general, but it’s always left too vague and generic. It needed to be made personal; and Obi-wan is the only one who could have really made it so. And it would put Obi-wan’s relationship with Luke in a new light.)

I think we would have needed more deviousness in the first triology to convince me.

I agree with what deiseach said above: the biggest flaw of Episode I was making Anakin a 9-yr-old boy, which, among a host of other things, makes the campy “I care for you” scene between Anakin and Padme in the spaceship on the way to Coruscant completely unbelievable and very creepy (from Padme’s POV).

In terms of “creative discomfort,” what you’ve basically described is Wilhelm’s Law (after Kate Wilhelm), which can be stated as thus: Don’t accept your first three ideas because those are the ideas everybody else will think of. I never much thought of it in terms of “creative discomfort” before, but that’s exactly how it feels sometimes.

The one point I’d disagree with you on here is that one can be a “pantser” or “discovery” writer and still use Wilhelm’s Law … still allow oneself to suffer creative discomfort. The key is using it while you write — not just before you write. Take Stephen King, for example. He was 500 single-spaced pages into THE STAND before he hit a wall, and it took him six weeks of creative discomfort before he realized how to get the story moving again in a satisfying way. If I’m not mistaken, this is how Tolkien wrote THE LORD OF THE RINGS. He wrote until he got stuck, figured out how to get unstuck, then kept writing. The one difference is that Tolkien went back and started a new draft of his story from the very beginning whereas King did not. But that might be because of the solutions Tolkien came up with, not because King is a lazy writer (at least not while he was writing THE STAND; I do think King’s some later works suffer from a certain amount of laziness, particularly his endings).

Some of us simply cannot bring a story into being without actually writing it down. I’ve found that I need to work an idea for a little bit before I start writing, and that once I start writing, the opening suggests a basic line of progression. Once I reach the end of that progression, it’s time to stop and figure out what happens next. Sometimes, I’ve already written something I can build from, and other times I have to make something up out of the blue, which generally (but not always) requires going back and layering in this development at a logical place. Then I’m off and running again until I hit the next wall, and thus the process begins again. I tend to think of this as “cycle writing”: I just keep cycling through the manuscript until I finally reach the end.

The key for any writer is to figure out how best his creative voice or subconscious works. Outlining a story in advance — and even preparing a simple, five-page synopsis, like what we did at Dave Wolverton’s workshop — is too much of a critical exercise for me. When I do that, I approach the story as if it’s a puzzle to be put together … not as something organic. For whatever reason, I cannot breathe life into a planned story.

All that being said, I think the debate between outlining and discovery writing is a fundamentally ridiculous one. Every writer works differently. Sometimes, a novel forces a writer to work in a certain way. Let’s go back to Stephen King for a moment. King’s a discovery writer, but the plot of THE DEAD ZONE, by the nature of the idea, was largely in place before he even began writing. Sometimes, as in the case of Brandon Sanderson, one moves from being a discovery writer to an outliner. And sometimes, a writer ends up doing both. Dean Koontz has both outlined novels and written them from little more than a basic idea.

For every successful outline writer one can name, another can name a successful discovery writer. The whole notion that a pantser/discovery writer takes the first idea that comes to him is a fallacy.

Okay. I’m now stepping down from the soapbox. Besides my quibble about pantsers taking the easy way, I found your essay quite interesting, Tom. It’s very good, and it’s given me quite a bit to think about in terms of my own creative process.

Personally, I’m a pantser who outlines. I head down into the Valley Full of Cloud, a la Terry Pratchett, but first I blaze a trail through the valley, then I go back and build a full scale one, with steps on the steep parts, and bridges for the muddy ones. . . .

I’ve found that when I’m stuck on the outline, and I think I know what happens next, the best route is often to take that and make the exact opposite happen.

Rambled more about discovering as I go here

What works for me: I believe in a sort of milestone outlining process (here are the key focal scenes at the key points that make up the highlights of the story) but I’m confident I can figure out the “so how did we get there” part when and as I need to.

On the one hand, I could work it all out in advance as an exercise, but I think that kills the “creative discomfort” aspect, makes it too much of a “working to plan.” I try not to scene-map more than about half an act in advance in any real detail, so that I have enough time to chew on things that the bright ideas that come out (“of course! that’s how X gets connected to Y!”) can be easily incorporated into the loose outline structure of what’s left. Sort of an alternating flow of outline/pantser/modified outline, etc.

Whatever outline exists, with its vivid scenes that I will preserve no matter what, imposes enough structure that I can let the rest move forward a bit at a time looking for creative ways to get to those vivid scenes. (And sometimes I get new vivid scenes to add to the structure in the process, not just connective tissue.)

I still say that Anakin was using the Force to bend Padme’s mind. It even explains her bizarre fashion choices for dates.

What really makes that relationship both more plausible and much more squicky is if you postulate that maybe Anakin was influencing Padme *unconsciously*. What Force-users want badly enough has a disquieting tendency to come about, after all; and if *what* they want is a *who*, especially someone who has no Force-talent of her own and can’t detect or resist it…. Perhaps the reason the Jedi instituted celibacy isn’t philosophical but brutally practical: a non-Force-sensitive mind that becomes too entangled with a Force-sensitive one has a terrible tendency to collapse. (This would even explain Padme’s death; she’s not dying of “heartbreak” — she’s dying of psychic disruption caused by Anakin’s madness.)

That’s genius. Too bad Lucas didn’t think of it. Unfortunately, there’s NOTHING in the prequels to even suggest that interpretation.

Well, she *does* confess her love in Ep. 2 with the words “I’ve been dying a little bit each day since you came back into my life.”

Squint at that quote a little and you can make it sinister.

This unconscious mind-control process (causing someone unwilling to fall in love with you, because you want it so intensely and “you don’t need to check my eHarmony profile/ I don’t need to check your eHarmony profile”) was done much more effectively (and disturbingly) by Krysten Ritter than by Christensen, and a different incarnation of Peter Cushing was involved.

I hope you’re right, as for me most second thoughts are easier and more fun than first thoughts.

But here’s a possible counter-example — Casablanca — if the following account is correct.

[….] the second half of the movie was written on the fly, script changes coming in daily as the writers realized even they didn’t know which man Ilsa would end up with, and the executives at Warner Bros. increasingly beginning to panic. And like TPB, it’s not so much a single movie as a mashup of different genres that come together like some tasty jambalaya. It’s a war movie with no Allied soldiers, a spy thriller with no secret agents, a cop movie where the chief is on the take (and we love him for it), a comedy where the stakes are deadly, and a romance movie where the leading man doesn’t get the girl. It all shouldn’t work, but somehow it wonderfully does [….] http://jeriendhal.livejournal.com/1062202.html

A movie in 1940s Hollywood having a woman separate from her war-hero husband? Not in the cards. How to get her on the plane with him, that was what was up in the air.

I like another blogger’s suggestion that the proper viewing order for the Star Wars movies is “4-5-2-3-6”, dropping TPM entirely.

The fact that “Ewok” is “Wookiee” reversed (more or less) is no accident. The original Episode VI was to be set on the Wookiee planet, but Ewoks made better plush toys.

My take it on it here: http://fathermckenzie.blogspot.com.au/2010/04/moreover-if-star-wars-had-been-made.html . Partly my own imagination, but originally sparked by someone else’s suggestion in 1982…

I know a lot of people think that the only reason the prequels were bad was because of the writing and directing. I however, think the problem was mainly structural. The prequels ACT like prequels, but they aren’t numbered like prequels. In fact, if you watch the movies in the order they’re chronologically numbered, you’ll have a far less satisfying viewing experience than you would have had if you had watched the original trilogy first.

Generally speaking, the purpose of a prequel is to flesh out characters and settings that the audience already knows about. You’ll lose some suspense in the prequel story (since you already know the fates of some of the characters and places) but you’ll gain valuable backstory. There’s nothing wrong with this. Unfortunately, trying to incorporate a prequel story in a franchise like Star Wars is a losing proposition–this is a franchise which depends on suspense and shocking plot twists–on not knowing what’s around the next corner. Watching episodes 1-3 spoils the experience of watching episodes 4-6. It changes the dramatic landscape of many pivotal scenes–The ones where Yoda and Vader both reveal their true identities to Luke, for example. Instead of being jaw-dropping moments that change everything we know about the characters, they’re just “Hm. We know who these characters are. How’s Luke going to respond to the news once he finds out?” moments.

Many people suggest watching the episodes out of order, but for the sake of the franchise, I think the episodes really need to be renumbered. (Perhaps they can’t be officially. And I know the prequels are probably set in stone and can never be remade.) But if I were to write an Alternative Universe Fanfic and try to fix the series myself, here’s what I’d do:

1. Renumber the series so the episodes are in the proper watching order (OT first). 2. Tie the two trilogies together by the device of a framing story. New Hope, Empire and Jedi are the new Movies 1,2 and 3. Movie 4 then, which takes place after Jedi, starts in the present day just after the defeat of the Emperor. Luke and Leia are trying to reestablish the Jedi order and start doing research about their father. Through this research, they discover people who knew their father–people who can relate to them his early history, which is shown to the audience via flashback. (Alternatively, Anakin’s force ghost could show up and tell his kids his early history himself.) Think of this idea as the Godfather 2 idea: In that movie there’s a framing story which continues in the present and a flashback story detailing the early life of a deceased character. We could do the same for the prequel trilogy. It would allow the main story with our beloved, already established characters to continue, (thus injecting some much needed suspense into the proceedings) and it would also allow us to explore Vader’s backstory, giving us new insight into his character.

There are plenty of other ideas I’d push for the alternate universe canon, but those are the main two.

These are good and interesting ideas. I only wish some of them had occurred to Mr. Lucas when he was actually making the prequels.

Comment I think you should read: http://accordingtohoyt.com/2014/09/30/the-broken-hero/#comment-205596

I freaking loved that essay, and I wish we’d gotten THAT Star Wars.

Great and illuminating history of Star Wars and its possible alternate endings, but there’s just one thing wrong with your ending for Episode III (and Lucas’s as well). In “Jedi,” Leia tells Luke she remembers her mother, if only a little bit. That seems to indicate that Leia lived with her mother when she was very young and that Padme died later, perhaps hiding from Vader on Alderaan. After Padme dies, Leia is adopted by the Organia family, probably the family who arranged Padme and Leia to be hidden in the first place. It’s possible Padme hoped to live to ultimately be reunited with Luke when the children grew up, but she became ill or some other matter came up that killed her.

Alternately, your ending might still work if something could have motivated Padme to go after Vader and the Emperior just three or four years later, some dire crisis Padme hoped to prevent. This would solve the problem of Padme still dying young and yet having Leia remember her.

You’re quite right. On the other hand, the same thing is wrong with Lucas’s ending for Episode III (along with all the other things that are wrong with it). If Padme died in childbirth, then Leia could not have remembered her mother any more than Luke did.

I think the official retcon is that Leia had memories of her adoptive mother, who died when she was small. I suppose that retcon could be applied to my proposed ending as well, but that would be shirking the issue. So I shall say nothing in my defence, except to reiterate what I said in the essai: I do not claim that the best ideas possible; they are only what I was able to come up with in a few minutes’ thought.

It would seem that either George Lucas is a much less creative thinker than I am, or he never gave the plots of the prequels a few minutes’ thought; and neither one of those possibilities exactly covers him in glory. For my own part, I throw myself upon the mercy of the court.

Possibly she confused her mother with the woman who brought her to her adoptive family and possibly stayed with her.

Of course, the real question is that she takes it for granted that Luke knows she’s adopted when that was a deep dark secret.

Though I have been thinking and about the proposal that the delivery room doctors have their memory wiped: perhaps that’s a perk that robot doctors off, that their service to you can be guaranteed discrete; they will compartmentalize the memory and then delete it.

I think the official retcon is that Leia had memories of her adoptive mother, who died when she was small. I suppose that retcon could be applied to my proposed ending as well, but that would be shirking the issue.

This is easily solvable, acutally: Have Anakin destroy the ship, then add a last shot, perhaps mid-credit, of Padme flying away in some sort of escape pod. Both the Emperor and Vader believe she’s been killed.

Recently re-read Harry Potter , where we find another mother who died just as Padme did.

Of course, Merope Gaunt was a considerably weaker-willed and broken creatures than Padme. Who had brought disaster on her own head by her own folly.

I love your suggested fixes to the the three Star Wars ‘prequels.’ I hated those movies with a passion, because I’d loved the original so much. Your ideas would have made those ‘prequels’ worth watching.

However, I must take issue with your insistence that slow creation is better than fast creation.

I think you equate slow creation with a greater willingness to suffer creative discomfort. It’s a natural conclusion to draw. But there can be other reasons for being slow, such as fear of success, fear of failure, fear of taking the ideal out of an idea, because the idea translated into a written story nearly always falls short of the magnificence it possessed in one’s mind.

My own experience is that I must never settle for an unsatisfactory or plebeian idea or solution. But the right idea will usually come quite quickly, if I simply keep brainstorming ideas until the right one turns up. And, if it doesn’t turn up during the brainstorming, it will arrive the next morning after my sleeping brain rests with the fruits of brainstorming and produces my answer upon awakening.

The key is not slow or fast. The key is to remain steadfast in one’s standards and willing to suffer creative discomfort, for however long is necessary. Meanwhile, one does whatever is necessary to generate more ideas, one evaluates them, and chooses the one that comes “trailing glory.” My opinion. 😀

I agree with you that the key is not slow or fast. But the key is to spend enough time at the ‘creative discomfort’ stage, however long or short that time may be, and not simply to run with the first plausible idea that comes to mind. Slow work is not better work, but rushed work is nearly always shoddy work.

Thanks for the thoughtful post.

I’d have to examine with you here. Which isn’t something I normally do! I get pleasure from studying a publish that will make folks think. Also, thanks for allowing me to remark!

[…] Tom Simon on Creative discomfort and Star Wars: […]

[…] Tom Simon submits the excellent example of George Lucas. I’ll sum up his brilliant article with the observation that the original Star Wars trilogy stands as a storytelling masterpiece because Lucas took his time, recognized his limitations as a screenwriter, and asked more qualified people for help. This sober approach gave us such classic moments as Han’s (preemptive) murder of Greedo, the ambitious threefold conclusion to Return of the Jedi, and of course, the still unequaled revelation of Luke’s true parentage. […]

[…] Creative discomfort and Star Wars: […]

[…] Rory Modena: A talented writer explains the history of the Star Wars movies, and rewrites some of the clumsier pl… right before our eyes. A lot of what bothered him blew right past me; I knew it was a pulp film and […]

[…] Gone with the Wind: seriously. Watch The Empire Strikes Back and pay attention to Han and Leia’s dialogue. H/t Tom Simon. […]

[…] is a fun story with interesting, likeable characters set in a compelling world. Even the prequels, as poorly written and unwatchable as they are, featured original ideas. They weren’t executed well at all, but Lucas was at least […]

[…] is a fun story with interesting, likable characters set in a compelling world. Even the prequels, as poorly written and unwatchable as they are, featured original ideas. They weren’t executed well at all, but Lucas was at least […]

[…] “Creative Discomfort and Star Wars“ […]

[…] not new to the Internet. My favorite writer of fiction came to my attention through his thoughts to improve the Star Wars prequels. I will admit this is a bit different. Most people view the Star Wars prequels as inferior to the […]

Speak Your Mind Cancel reply

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |||

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 23 | |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

| 31 | ||||||

Sign up here and we'll keep you up to date on new releases and special events.

Books by Tom Simon

Essay collections

Thought clusters

Superversive fiction.

Abyss & Apex A webzine of science fiction & fantasy Edited by Wendy S. Delmater Sci Phi Journal A journal about science fiction and philosophy Edited by Jason Rennie SuperversiveSF Science Fiction for a more Civilized Age

Blogs for writers

The Passive Voice David P. Vandagriff Author Earnings Hugh Howey & Data Guy Let’s Get Digital David Gaughran J. A. Konrath

Other blogs I read

Jimmy Akin Mary Catelli Monster Hunter Nation Larry Correia Sarah Dimento Edward Feser The TOF Spot Michael Flynn Welcome to Arhyalon L. Jagi Lamplighter Kairos Brian Niemeier John C. Wright

Recent Posts

- Uninteresting things

- From the lecture notes of H. Smiggy McStudge

- Antici . . . pation

- I spy, with my altered eye

- The story so far

- A dash of rhetoric

Recent Comments

- Garth on Uninteresting things

- Mary Catelli on Uninteresting things

- Unconcord on Uninteresting things

- Codex on Style is the rocket

- Koby Itzhak on Uninteresting things

- Tom Simon on Uninteresting things

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Return to top of page

Copyright © 2024 · Prose on Genesis Framework · WordPress · Log in

Interview: New collection of Star Wars essays informs and inspires

By eric clayton | sep 30, 2023.

I was in seventh grade when I stumbled upon Star Wars and Philosophy: More Powerful Than You Can Possibly Imagine in my local—and now deceased—Borders bookstore. I was amazed and very much in over my head.

But still, the notion that my favorite franchise had something to say about ethics, power, democracy, and justice beyond the simple flash of dueling lightsabers was groundbreaking to my young mind. I gobbled that book up in the same way I gobbled up the Star Wars: The New Jedi Order novels.

Many years and many canon and legends tales later, I’m still struck by what Star Wars says about our very real, completely canon, and not all legendary lives. I’ve read books, essays, and articles on how Star Wars intersects with Hinduism, Zen Buddhism, and Daoism. I’ve interviewed theologians on the topic of Star Wars and Christian thought. And I’ve participated in the inspiring digital conference, “Realizing Resistance,” where academics from around the world talked about how lessons learned from a galaxy far, far away are quite applicable to our own environment, history, culture, and relationships.

It was at that same conference where I met Emily Strand and Dr. Amy Sturgis, two of my fellow conference presenters. Emily, a member of the 501st and Rebel Legions international Star Wars costuming associations, has a background in and teaches college-level courses on world religions. Amy’s research is on the intellectual history of speculative fiction, and she teaches at Lenoir-Rhyne University and Signum University. Both have published many books and articles, including the new Star Wars: Essays Exploring a Galaxy Far, Far Away .

The collection of essays is remarkable. Amy Richau examines the evolution of Twi’leks while John Jackson Miller tackles the sticky topic of canon. There are essays on video games, worldbuilding, and the depiction of motherhood. As Ian Doescher writes in the Foreword, “With each page, you smile at familiar references, you grapple with new ideas, you reshape your thoughts and beliefs, and you emerge with a new understanding and appreciation.”

Emily and Amy kindly shared their experience working on this project in an interview we conducted via email. As Emily says, “Academic writing on popular culture works because it represents not just one person’s ‘take’ but a community’s conversation. … [These] conversations are not rushing to be the first to notice something about the text, but consider what many people have noticed and draw specific conclusions about what it all means to enhance our enjoyment.”

“Star Wars is both timeless and timely, inspired by history and informed by the present,” Amy says. “Working on this project has left me with fresh energy as I contemplate new works of Star Wars storytelling.”

I believe the reflections Emily and Amy share in our conversation will inspire you, too, as we fans continue to integrate all Star Wars stories—old, new, forthcoming, and forgotten—into our work, relationships, and lives.

Eric: Why should fans care about approaching Star Wars through an academic lens? How does this deepen fandom and our understanding of Star Wars?

Amy: I wouldn’t presume to tell fans what they should or shouldn’t do but as a fan myself (since 1977!) as well as an academic, I can say that scholars who come from different disciplines with diverse tools and training find a variety of questions to ask of Star Wars that I myself wouldn’t think to pose — and the answers they find enhance my understanding and appreciation of the franchise. What these essays provide together is a snapshot of 46 years of transmedia Star Wars storytelling and the discussions it has launched, and that kind of big-picture perspective is valuable to have, no matter your entry point into the universe. I hope the questions raised here also serve as an invitation to readers to join in and continue the dialogue. This isn’t the first anthology of essays on Star Wars, and it won’t be the last, but my wish is that fans will find it deep in its investigations and broad in its implications, accessible and insightful, and — most of all — welcoming, a springboard for more thought and conversation about the stories they love.

Emily: There are countless YouTube (etc.) accounts solely for the purpose of providing analysis of popular stories. So why do we need academic writing like this? I appreciate academic writing on popular culture works because it represents not just one person’s “take” but a community’s conversation. One person writes a piece, another person (often several!) makes suggestions or challenges a particular insight, and the work changes in response. Even after a work is published, another scholar may disagree with it or want to add to it, and eventually they respond formally in their own published piece, or on an academic blog, etc. Thus the conversation continues. And the pace is different too—academic conversations are not rushing to be the first to notice something about the text, but they consider what many people have noticed (including non-academic sources) and draw specific conclusions about what it all means to enhance our enjoyment of franchises like Star Wars. Ultimately, Star Wars is a creative endeavor, a communicative endeavor. Academic writing on it asks and answers the question: what is it communicating? Is it communicating it well? What could it communicate? These big questions excite and engage me as a fan more than “hot takes” and “breakdowns.” But, as Amy said, to each his own!

Eric: Which essay most changed how you view Star Wars? What of your experience of Star Wars did it change and why?

Amy: I find the subject of gaming to be overlooked and underserved in scholarship generally. Because of this, I was especially delighted to learn from Aaron Masters about how the choices and consequences embedded in Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic II—The Sith Lords invite deep questioning and contemplation of the foundational ideas of Star Wars. In addition, by looking at the game of Sabacc both inside Star Wars stories and outside of them, in the real world as played by fans, Jennifer Russell-Long gave me a new appreciation of how games relate to community experience and cultural memory. That said, every one of the essays in this anthology changed how I view Star Wars. It was a privilege to help put all of these works by our expert essayists out into the galaxy.

Emily: This is a tough question because in some way, all the essays changed my thinking on Star Wars. That is—to me—the mark of a good academic piece: It’s perspective-shaping in its argument and it’s persuasive in its support for that argument. A few great examples of that in the book have to do with the roles of female characters: Amy Richau’s chapter on Twi’leks, Vikki Terrile’s chapter on makers in the Disney era, and Éloïse Thompson-Tremblay’s article on mothers. Each shows diverse aspects of women’s representation in Star Wars, and in the complexity and thoroughness with which they treat their subjects, they don’t allow for facile conclusions about women in a galaxy far, far away. They demonstrate that “it’s complicated,” and they also show that the depiction of women in Star Wars is evolving—and that’s exciting to think about.

Eric: In his foreword, Ian Doescher writes: “You make connections because Star Wars is part of your identity, and you want it to speak to your other interests.” What “other” interests has Star Wars spoken to in your own lives? How has it deepened those interests?

Amy: Star Wars has been in conversation with Star Trek in my head since I was very young, and the two continue to complement and contrast with each other in ways that challenge and inspire me. They’ve made me a lifelong student and devotee of speculative fiction. While each franchise suggests a very different view of history, both agree that we must be deeply aware of and thoughtful about what has happened before if we hope to make a positive impact on what comes next. The way these franchises comment on history and ask us to consider its patterns helped lead me to become a professional historian. I now take great joy in teaching and writing about history through speculative fiction, especially through Star Wars and Star Trek.

Emily: I came to Star Wars relatively late—as an adult. And I came to it as a gigantic Harry Potter fan. So I saw Star Wars through a Harry Potter lens. For instance, I love Star Wars Rebels because it really spoke to me as a Harry Potter fan: a magical, orphaned kid finds a new family and fights a super creepy bad guy who represents and enacts systematic oppression—those parallels seem intentional. We think of Star Wars as the “ur text” for pop culture phenomena, but it’s interesting to view it as influenced by other, later stories, like Potter. Kathryn N. McDaniel’s piece in our book draws wonderfully on these same assumptions in the way it parallels Rey in the Sequel films with Harry, in their character arcs and their growth into their roles as heroes.

Eric: What other avenues for Star Wars inquiry has this project opened up in your mind? What questions do you want answered next…and why?

Amy: I want to know what comes next for Star Wars! The essays in our anthology highlight points of continuity and evolution in Star Wars storytelling over time and across different formats, and their insights encourage me to continue to dig deeper. I’m particularly intrigued by how recent Star Wars works have sharpened the focus on those who are not Jedi or Sith but instead everyday people trying to survive. More than ever, I am interested in exploring how Star Wars creators and fans together are asking big questions about important subjects — about authoritarianism and control, for example, and resilience and resistance. In short, Star Wars is both timeless and timely, inspired by history and informed by the present, and working on this project has left me with fresh energy as I contemplate new works of Star Wars storytelling, why they matter and speak to us, and how their ideas will follow me into my research, classroom, and fandom community.

Emily: I hope to keep exploring the spiritual elements of Star Wars in ways that help fans understand ourselves and our instinctive reactions of wonder (as Ian Doescher puts it so well in the book’s foreword) and how we can foster that sense of wonder in other areas of life—to our and to society’s benefit. I’ve also gotten involved in Star Wars costuming in the last few years, and it’s been a great source of joy for me. But I also find the culture of it fascinating, and I can envision pursuing academic work that draws on the experience of being “embedded” with my local costuming communities. Ethnography could be a really interesting way to explore what motivates and drives these talented makers of costumes and props from a galaxy far, far away.

Learn more about the book, Star Wars: Essays Exploring a Galaxy Far, Far Away , and visit the editors’ official pages: Emily Strand and Amy Sturgis .

- Conventions & Events

- Film, Music & TV

- Literature & Art

- Vintage Collecting

- Collecting & Fashion Reviews

- Conventions & Events Reviews

- Film, Music & TV Reviews

- Gaming Reviews

- Literature & Art Reviews

- Fantha Tracks Radio

- What Is Fantha Tracks ?

- Contact The Editors

- Contribute News

- Advertise With Us

- Contact DPO

- Cookie Policy

- Contact DMCA

- Data Rectification

- Request Data

- Privacy Policy

- Terms And Conditions

- Disclosure Policy

- Privacy Center

San Diego Comic Con 2024: FiGPiN Dark Side Box Set

Young woman and the sea: becoming a legend, star wars lofi: nighttime at jabba’s palace, star wars fan fun day 2023: hazel lyth, naimos resident in andor, the acolyte: stunt sequences and martial arts action, the acolyte: leslye headland on the origins of mae and osha, star wars: galaxy of adventures: score co-ordinator vinicius barbosa pippa talks about his work, amandla stenberg talks the acolyte on the view, leslye headland on the stranger: “if i can get manny jacinto, this will work”, leslye headland on the jedi of the acolyte: “i hope it’s making people look at it from a different point of view”, starfury: invasion 2024: mary elizabeth winstead panel recap, starfury: invasion 2024: diana lee inosanto and nelson lee panel recap, film and tv review: the acolyte: ‘teach / corrupt’, comic review: darth vader (2020) #47, event review: starfury: invasion 2024, essay about star wars: how to write a stellar paper.

Today, Star Wars seems to be an irreplaceable part of our culture, and it concerns not only Americans but the whole words already. As an outstanding piece of the movie industry, and, in the wider sense, art, it deserves to be spoken and written about.

In the core, writing a Star Wars essay doesn’t differ much from writing any other essay. The same structure, the same logic of presenting arguments and proofs, the same intro and wind up. Still, it might be a little bit more difficult as the story requires additional research and the time to think it over. It’s always better to write it on your own, expressing what only you can express, but for critical moments when there is no time left, there is, luckily, a great online helper. With a single text message ‘ Write my paper about Star Wars’, you will gain its exceptional writers’ assistance as quickly as possible. With an outstanding essay writing service like WriteMyPaperHub, you will not have to spend so much time on reviewing the movie and compiling your thoughts together.

And now we will provide some glimpses on how to do it yourself – join us!

A Comprehensive Guide on How to Write a Star Wars College Essay

Before you start writing your first draft about the story, don’t think that you already know everything if you had seen the movie some time ago. To understand what you are describing, you need to delve deep into this Star Wars universe: devote an evening or two to reviewing these episodes, select and write down what has made a particular impact on you, and try to think of the ideas that stand behind the conversations and the plot turns.

Passing this preparatory stage, proceed to make the plan – first, think of what idea was the strongest and affected you greatly (ideally, not connected to politics). This idea will be a perfect ‘hook’ to place in the introduction and grasp the reader’s attention and awaken curiosity.

After that, there are more steps, since creating a well-shaped essay should be aimed at the wholesome picture, not a sum of several rough drafts.

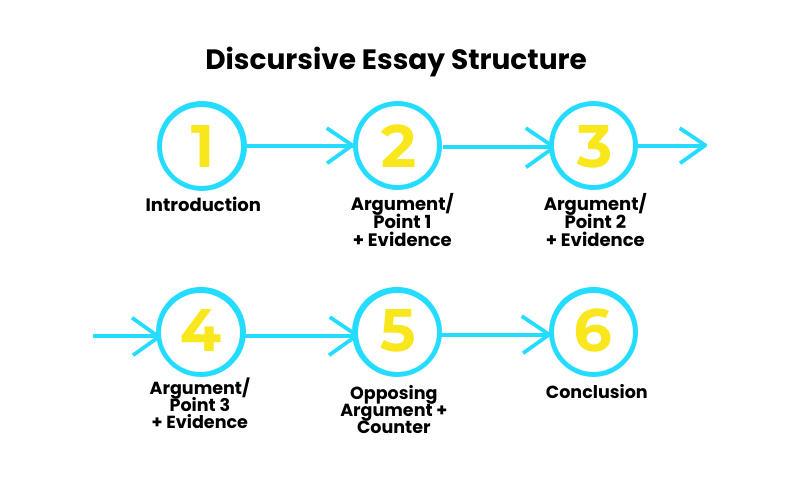

- Choose the conflict / main idea of your essay . This is the point that your whole essay will be devoted to – a good option will be to choose ever-relevant topics like teacher and learner, peace and war, human relationships including race and gender, etc. Here you can also add some interesting facts about the world of Star Wars. They will capture the attention and give you the space to continue the story, putting forward your thoughts and impressions.

- Choose the topic . Having the idea is great, but it will be conveyed only if you formulate it well. The topic should sound appealing but not be too straightforward or reveal the end conclusion that you are about to make. Besides, be careful with conclusions as it often happens that when you begin to write an essay, being quite convinced in one opinion, you end up thinking differently. In these cases, the topic should reflect a part of this change.

- Write the body part in a personalized manner . Here, in this essay, nobody needs you to retell the whole story, – you write this text to communicate to the world what you have seen in this most successful movie of all times because all of us see differently. Sure thing, you can mention the main events, characters, and parts of the plot, but be sure that you view them critically, analyzing each action to come to a certain logical conclusion and perceiving the story with your own unique background.