How to Do Market Research for Small Business: 8 Affordable Market Research Techniques

Small business market research is a tough game.

If you Google “how to do market research,” you’ll come across a long list of tactics that are hard to use on a small business budget.

- Market research surveys

- Questionnaires

- Focus groups

- Competitive intelligence

- SWOT analysis

- Structured interviews.

The list goes on.

If you dig even further into market research techniques, you could quickly find yourself reading about the difference between qualitative and quantitative research, or even statistical sampling methods.

All of these market research techniques have their place. But when you’re wondering how to do market research for small business , you aren’t thinking about complicated statistical models or big budgets.

Market research firms sometimes run massive surveys and international focus groups. You might not have a way to reach 100,000 people with a survey, or the resources to set up multiple focus groups. Your market research process might not be able to include a ton of technology or statistics.

But there are still small business market research tools that work. Conducting market research for a new business or a small business can require some creativity.

With the right tactics, you can do affordable or even free market research that gets you the insights you need for your business.

How can market research benefit a small business owner?

Right now you’re probably wondering: why do you need market research?

Small businesses already have a lot of day-to-day operations to deal with.

It’s hard to make time to do market research for small businesses—especially if you also need to learn how to do market research in the first place.

But if you don’t periodically check in with your audience, you could be leaving business and revenue on the table without ever knowing.

There are many benefits of market research for small business, but the top ones include:

- Helping you create more compelling marketing materials

- Identifying more targeted niches interested in your company

- Suggesting ideas for new products or services based on pain points

- Minimizing the risk of bad positioning that costs you leads without you knowing

- Giving you early updates on industry trends before they become widespread. For a comprehensive overview of these trends, you can check out Incfile’s guide to small business trends

Simply put, effective market research helps you get inside your customers’ heads. How cool is that?

When you need to conduct market research on a tight budget, it can be tricky to find the techniques and market research tools that give the best value for the time and cost investment.

Here’s 8 of our favorite affordable market research techniques.

- Book reviews

- Facebook groups

- Competitors

- Behavior and analytics

- Ask your audience

1. Quora: How to use Quora for market research

Quora is a social media platform based on questions and answers. On Quora, users can submit questions on any topic they like, as well as answer questions related to their expertise.

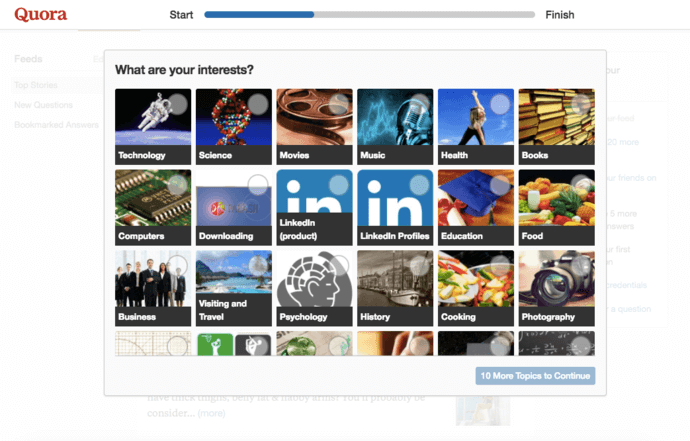

Getting started with Quora is easy: the platform guides you through the process and immediately prompts you to select your areas of interest.

Setting up your Quora profile will let you get notified when questions are tagged with the topics you select. That makes it easy to see what burning questions your audience is asking.

And because Quora orders its answers based on voting, you can also see which solutions they think are the most valuable.

For that reason, Quora market research can be a great method of collecting information on customer pain points. In market research for small businesses, free public questions from your audience is hard to beat.

If it fits into your marketing plan, you can also consider putting some effort into answering Quora questions. Repurposing your blog posts as part of a Quora marketing strategy can increase their reach and visibility.

2. Reddit: How to use Reddit for market research

Reddit bills itself as “the front page of the internet,” and for good reason—Alexa ranks Reddit as the eighth most trafficked website in the world and the fifth most trafficked in the United States.

Reddit contains a wide variety of communities, linked content, original content, and memes. But among cat videos and adorable GIFs, there are some surprisingly insightful conversations—discussions that are a gold mine for small business market research.

Reddit is organized into “subreddits,” which are communities focused on specific topics. Finding subreddits based on your industry is a good way to mine for pain points—and discover your audience’s candid thoughts.

Anonymity means that Redditors are often willing to share things they wouldn’t normally talk about in person. Reading discussion threads or even asking questions yourself can help you get insights from specific niches.

For example, if you run a fitness business and need to know how to do market research, you’ll find that there are quite a few opportunities to conduct customer research on Reddit.

Subreddits like these will show up:

- /r/bodybuilding

- /r/bodyweightfitness

Each of them serves different communities, and people often share their successes and struggles.

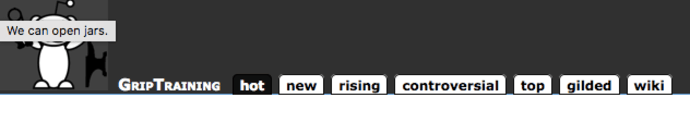

Reddit can also help track down a very narrow segment of a larger population. A subreddit like /r/griptraining is the very definition of niche—but if you run a rock climbing or powerlifting gym it could have valuable insights from your target audience.

Navigating Reddit can be a little tricky for new users. But once you figure it out, it’s a powerful tool to do market research for small business.

3. Book reviews: How to use Amazon book reviews for market research

This market research technique is a little bit unusual—but it’s all the more powerful because of how few people think of it.

When you need to conduct market research on a tight budget, you need to get creative. Book reviews offer a wealth of information, sometimes incredibly detailed and specific, that few people are taking advantage of.

Amazon reviews are public, and you probably have some idea of the most important or popular books in your field. Even if you don’t, Amazon charts are also freely available—it’s easy to find out what people are reading.

Once you’ve tracked down some popular books, take a look at the reviews. Amazon lets you easily sort reviews by how positive they are and how helpful they are, so you can dive in at whatever point you like.

Joana Wiebe of Copyhackers is a huge review mining advocate to get to know your audience – and rightfully so. You can hear exactly what people’s problems and wishes are in their exact language.

Positive reviews will be helpful because they can help you understand what people are benefiting from.

Negative or lukewarm reviews can be even more helpful because there’s a chance they call out needs or burning pains that the book didn’t answer—which may represent unmet needs your business can take advantage of.

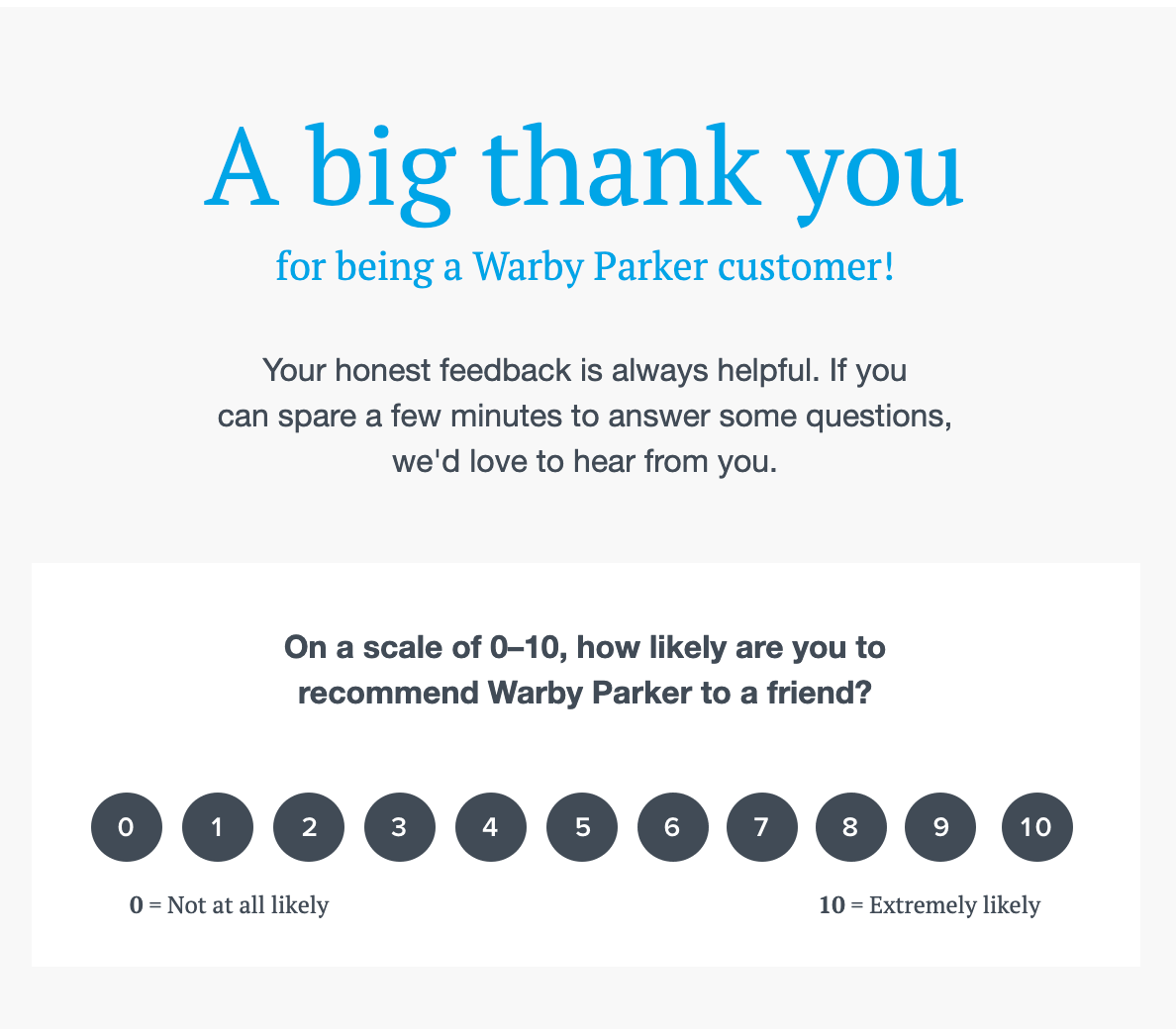

4. Surveys: How to use a survey for market research

When most people think of using a survey to do market research for small business, they think of a massive effort that goes out to thousands and thousands of customers.

No, you probably don’t have thousands and thousands of customers who will respond to a survey. And there are some types of survey research that really do require those kinds of numbers.

But others don’t. And those are the kind you can focus on as you learn how to do market research for your small business.

Setting up surveys that get sent to customers after a sale can help you get a sense of how satisfied they are and what needs to lead them to make a purchase.

Similarly, you can set up surveys that go out to people that didn’t make a purchase. What prevented them from buying? What might have caused them to make a different decision?

Even if you only ask those two survey questions, the answers can help you make adjustments for the next time around.

BONUS – this type of small business market research is easy to automate.

Setting up automations that trigger based on a purchase or lack of purchase is easy to do with marketing automation software. Set up survey questions once, then focus on other parts of your small business while the results come in.

5. Facebook groups: How to use Facebook for market research

Facebook has risen as one of the major community-building platforms for small business. Type your industry into Facebook search and you’re bound to find a variety of related groups.

Some Facebook groups will be run by other business owners, others are simply people interested in the same topics. Regardless, reading through the conversations and questions asked in Facebook groups can be a valuable source of market research.

When you’re using Facebook for market research, you have a few options.

Simply reading through existing conversations is a great way to get started.

Even though names on Facebook aren’t private, people are often more willing to share their goals or frustrations within a relatively private group.

Once you’ve observed for a while and understood a group’s tone and social norms, you can start to join the conversation. Becoming a member of a group and engaging in discussions can be a great way to ask questions and go beyond surface-level insights.

You can’t do this on another business’s page, and you have to be careful about coming off spammy, but Facebook groups can also help you get participants for a market research survey.

As you get more comfortable with how to do market research on Facebook, sharing a link to a survey can help you gather quantitative market research data.

As a free platform with over two billion monthly active users , Facebook can be a powerful way to do market research for small business.

6. Competitors: How to use competitor analysis for market research

Chances are you’re not the only business in your niche. How are the most popular websites in your industry trying to appeal to your audience?

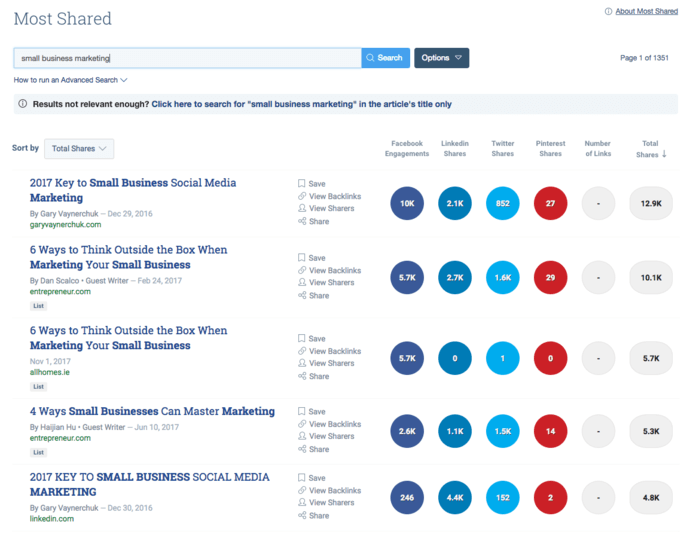

How can you tell which content is the most popular or successful? Use a tool like Buzzsumo to find the most shared content on a particular topic.

A tool like SEMrush can tell you which content ranks the highest in search engines. Both are good ways to identify potentially high-value topics.

Beyond content, look at the other marketing materials your competitors put out.

- What kind of messaging are they using on their website?

- How are they creating cross-sell and upsell opportunities?

- What does their team look like—who’s actually doing their marketing?

As you grow your business, this kind of information becomes more useful.

There’s no guarantee that your competitors are doing everything the best way—but seeing how they are managing their business can spark ideas to improve your own.

Here’s how you do this kind of research:

- Collect all of the info your competitors make publicly available

- Comb through their website and about page, download flyers and brochures, and check out the events they attend.

- Make absolutely sure you get on their email list , so you can see what kind of messages they like to send.

It’s worth taking competitor research with a grain of salt. Again, there’s no guarantee that competitors have done the level of customer research you’re looking for. Still, looking at competitor messaging is a useful way to infer the features and benefits that matter to your audience.

Competitor research isn’t a substitute for contacting your audience directly, but it can be a good starting point to figure out what kind of content is popular in your niche.

7. Behavior and analytics: How to use data for market research

It’s one thing to know what customers say they want. In any industry, professionals know that customers don’t always know how to solve their problems. Sometimes there’s a better question to ask for market research.

What do they actually do?

Tracking behavior on your website or engagement with your emails and messages is a great way to see which of your marketing efforts are most popular—and can help you adjust your marketing in the future.

Google Analytics is one powerful tool that can show you exactly how people engage with your website.

What content topics are the most popular? Make more content on those topics. Which pages have the best conversion rates? Direct more traffic to those pages. Your content marketing is also a source of information about your audience.

Combining website tracking with marketing automation can take things to the next level.

Marketing automation software can track email opens, link clicks, behavior on websites, replies/forwarding—and use those insights to automatically follow up with customers on what they care about most.

Of all the affordable small business market research techniques on this list, data is the most actionable. Analytics allow you to go from insight to action almost instantly—and sometimes automatically.

8. Ask your audience: How to use interviews for market research

Even though people don’t always say quite what they mean, there’s no substitute for direct, one-on-one conversations with your audience.

A market research interview allows free conversation that leads to deeper insights than survey or written answers. If you can get people to open up, you’ll be rewarded with detailed information about their pain points, struggles, and successes.

The style of the interview is less important than getting interviews done. You can do phone interviews, in-person interviews, even email interviews—and still get actionable insights.

The lessons you learn from talking to even 10 customers can change your business strategy, marketing, or client service. The ability to speak to customers using their own language is like a marketing superpower.

Customer interviews are the way to do it.

Entire businesses can be built on what your customers tell you. When you listen to your audience, you get to the heart of what they care about—and no amount of online market research or survey data can tell you that as precisely as they can.

Conclusion: Use market research to get inside your customers’ heads

If your business grows, you’ll eventually want to consider the focus group, survey, statistical analysis, and market trends approach to market research.

Those methods can reveal insights that are hard to find using more affordable market research techniques.

If you need to understand market saturation, or build a picture of how your pricing compares to the competition, you’ll eventually need to use some of the more traditional forms of market research.

But there’s value to doing market research before you have the budget for standard methods. Getting in touch with your customers’ needs can give you a huge edge as a small business.

Not a lot of people do market research for small business like this. Most prefer to wait until they can hire someone to do it for them (or just ignore it entirely). That’s where you can get a head start on others, as well as using features like Google Ads , company branding , and small business software .

Because of that, these types of affordable market research techniques are a huge competitive advantage—one that lets you get inside the heads of your customers and offer them exactly what they want to buy.

Thanks to Canva Presentations for creating a slide deck of this article: How to Do Market Research for Small Business

No credit card required. Instant set-up.

Please enter a valid email address to continue.

Related Posts

If someone off the street asked you to explain a microsite, could you do it? This post will teach you:...

2024 brings an abundance of remarkable choices for no-code software, empowering businesses to streamline operations and accelerate growth. This article...

32% of survey respondents already used AI and marketing automation for email messages and offers. And with technology like Chat...

Try it now, for free

| You might be using an unsupported or outdated browser. To get the best possible experience please use the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Microsoft Edge to view this website. |

Small Business Statistics Of 2024

Updated: Jan 31, 2024, 10:00am

Table of Contents

Small business employment statistics, small business job creation, small business salaries & wages, small business ownership statistics, online & e-commerce business statistics, small business costs, small business survival statistics, conclusion: what do these statistics mean for small businesses, methodology.

While giants in technology and multinational corporations often capture the public’s attention, it’s small businesses that form the crux of the American economy. As we step into 2024, these businesses continue to evolve, reflecting not only their enduring role in job creation but also their significant contributions to innovation, economic dynamism and the country’s overall prosperity. The latest small business statistics for 2024 do more than just present a snapshot of the current state of affairs; they offer a window into the emerging trends and future directions.

Featured Partners

ZenBusiness

$0 + State Fees

Varies By State & Package

On ZenBusiness' Website

On LegalZoom's Website

Northwest Registered Agent

$39 + State Fees

On Northwest Registered Agent's Website

$0 + State Fee

On Formations' Website

1. Almost all businesses across the U.S. are small businesses

While large corporations often grab headlines, it’s small businesses that form the bedrock of the American economy. Recent data from the U.S. Small Business Administration reveals a remarkable figure: 33.3 million businesses [1] in the United States qualify as small businesses, making up 99.9% of all U.S. businesses. This number not only reflects the dominance of small enterprises in the business sector but also shows their significant role in generating employment and contributing to economic stability, a trend that remains relevant in 2024.

2. Nearly half of all U.S. employees are employed by a small business

The impact of small businesses on the U.S. job market is more significant than often perceived. Although a majority of small businesses, over 80%, operate without any staff, these entities still employ a total of 61.6 million people. This figure represents 45.9% of the entire U.S. workforce [1] , a remarkable statistic especially when considering that fewer than 20% of small businesses have any employees. This data not only shows the importance of small enterprises in job creation but also their role in sustaining the economy. It’s clear that the growth of small businesses is integral to the nation’s employment health and overall economic success.

3. Over eight out of 10 small businesses have no employees

Reflecting a significant trend in the U.S. small business sector, data reveals that a vast majority, over 80%, of small businesses are solo ventures. Out of the 33.3 million small businesses in the country, 27.1 million are managed solely by their owners and do not employ any additional personnel [1] . This statistic sheds light on the significant number of individual entrepreneurs in the U.S. It demonstrates the independence and self-reliance characteristic of many small businesses, illustrating their unique role and contribution to the U.S. economy, even without a workforce.

4. Just 16% of small businesses have one to 19 employees

While the majority of small businesses in the U.S. operate without any employees, there is still a significant segment that does employ staff. Specifically, 16% of small businesses fall into the category of having between one and 19 employees. This equates to over 5.4 million businesses. On the larger end of the small business spectrum, only 647,921 businesses have a workforce size ranging from 20 to 499 employees [1] . These figures give insight into the distribution of employee numbers within small businesses, showing a majority leaning towards minimal or no staff, with a smaller yet notable proportion employing a larger number of workers.

5. Small businesses have added over 12.9 million jobs in the last 25 years

Despite the average small business being operated by a solo founder, these enterprises have been a significant source of job creation in the U.S. In the past 25 years, small businesses have been responsible for generating nearly 13 million net new jobs [1] . This accounts for approximately two-thirds of all new jobs added to the economy during this period. This trend emphasizes the enduring role of small businesses in bolstering employment, even as business continues to evolve. As we look toward the future, the continued contribution of small businesses to job creation remains a vital aspect of economic growth and resilience.

6. The leisure and hospitality industry has the highest average of jobs added per month over the last year

In the wake of the pandemic’s impact, the job market has shown remarkable resilience, especially in certain sectors. While the professional and business services industries have been significant contributors to job growth, adding over 1 million new jobs in the last 12 months, it’s the leisure and hospitality industry that stands out for its recovery pace. This sector has demonstrated the highest average monthly job growth, adding an average of 52,000 jobs per month over the last year [2] . This surge in job creation reflects not only a rebound from the severe impacts of the pandemic but also the sector’s critical role in the broader economic recovery. Overall, the labor market has seen an increase of 5.8 million jobs since last year, surpassing its February 2020 level by 240,000 jobs, signaling a strong recovery trajectory.

7. The industry with the most job openings is the professional and business services industry

The professional and business services industry now leads in job openings [2] , a shift from the previous trend where education and health services were more in demand. This change signals a strong need for skilled workers in areas such as management, administration and consulting. Job seekers exploring opportunities in this field may find promising prospects for stable employment. For businesses operating in these sectors, the surge in job openings presents challenges in attracting and maintaining a skilled workforce, reflecting the dynamic nature of job markets and the evolving needs of industries.

8. The industry with the highest projected job growth is home health and personal care

While the professional and business services industry currently leads in job openings, the home health and personal care sector is projected to experience the most significant job growth. An estimated increase of 22%, translating to over 804,000 new jobs [2] , is expected in the next decade. This surge in demand can be attributed to factors such as an aging population, which necessitates more in-home healthcare services. The trend towards personalized and patient-centric care models also plays a role, as does the increasing preference for in-home care over institutional settings.

While the professional and business services industry currently has the highest number of job openings, the home health and personal care industry is expected to see the highest growth. Over the next decade, it is estimated to see an increase at the astronomical rate of 22% and add a over 804,000 jobs. [2] This reveals projected growth within the home health and personal care industries, which is slated to increase in demand given the fact that the aging population is growing disproportionately larger than the younger generations.

9. The leisure and hospitality industry is still recovering from Covid-19

The Leisure and Hospitality industry, which experienced significant job losses due to the Covid-19 pandemic, is on a path to recovery. While the industry faced a shortfall of 633,000 jobs since February 2020 [2] , recent trends show positive momentum. In 2023, the industry has been adding an average of 41,000 jobs per month. This is a decrease from the 2022 average of 88,000 jobs per month, yet it represents continued progress. Despite these gains, employment in leisure and hospitality remains 223,000 jobs below its pre-pandemic level as of February 2020. The industry’s recovery, spurred by resumed travel and increased demand for leisure activities, is still unfolding as it works to regain its pre-pandemic strength.

10. Nevada and D.C. have the highest unemployment rates in the nation

Recent data places Nevada at the forefront in terms of unemployment rates in the United States, with a rate of 5.4% [2] . Following closely is the District of Columbia, recording a 5% unemployment rate [2] . These figures suggest particular economic challenges or labor market conditions unique to these regions. Nevada, known for its tourism-centric economy, particularly in areas such as Las Vegas, may reflect the lingering impacts of the pandemic on the hospitality and entertainment sectors. Similarly, D.C.’s rate could be influenced by its distinct urban and political dynamics.

Conversely, Maryland showcases the nation’s lowest unemployment rate at just 1.7% [2] . This could be attributed to the state’s diverse economy, which includes sectors such as bioscience, manufacturing and cybersecurity, coupled with its proximity to the federal government’s numerous agencies providing a stable employment base. Maryland’s low unemployment rate indicates strong job market health and potentially effective economic policies at play.

According to the most recent data, Nevada has the highest unemployment rate in the country at 5.4%. Right behind it is the District of Columbia at 5% [2] . Meanwhile, on the other end of the spectrum, Marylandhas the lowest unemployment rate at just 1.7% [2] .

11. New Jersey had the largest increase in unemployment over the last year

Over the last year, New Jersey has seen the most substantial rise in unemployment rates, with an uptick of 1.3% [2] . This change points to specific economic shifts or challenges within the state. On a different note, Maryland experienced the most significant reduction in unemployment, with a decrease of 1.5% [2] . This could be linked to its varied economic strengths, contributing to a more stable job market.

12. The number of U.S. jobs will increase by 87,000 in 2024

In 2024, the U.S. job market is projected to witness an increase, though modest, in the number of jobs. Specifically, employment across the United States is anticipated to grow by 87,000. To put this in perspective, considering the 9.6 million jobs lost due to the Covid-19 pandemic between May 2020 and September 2022 [2] , this increase represents a small step towards recovery. It’s a noticeable shift from the 2.72 million jobs added in 2023 [3] , indicating a slower pace of job market recovery in 2024. This suggests that while there is progress in regaining the jobs lost during the pandemic, the journey towards a full recovery is gradual and ongoing.

Over the next year, the number of jobs in the U.S. is expected to increase by 87,000. Granted, this is following immense job loss due to the pandemic. According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, [2] 9.6 million jobs were lost in the U.S. due to covid between May 2020 and September 2022. In other words, the projected job growth for 2023 remains just a fraction of what was lost during the pandemic. This indicates that while the nation is in recovery, it still has a long way to go.

13. By 2032, the number of U.S. jobs is projected to increase by 4.7 million

By 2032, the U.S. job market is expected to see an increase in employment, with a projected addition of 4.7 million jobs [2] . This expansion will bring total employment to an estimated 169.1 million. However, this growth, with an annual rate of just 0.03%, marks a significant slowdown compared to the previous decade's annual growth rate of 1.2% from 2012 to 2022 [2] . This slower pace of growth indicates a lengthy recovery period from the job losses incurred during the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite the increase in total jobs, by 2032, the U.S. will still be recovering from the pandemic's impact, as the growth falls short of fully compensating for the 9.6 million jobs lost during that period.

14. The fastest-growing industries are healthcare and social assistance

Not only do the healthcare and social assistance industries have the highest survival rate across all industries, but it also boasts the fastest growing industry. [2] . This growth is driven by increasing demand for health services due to an aging population and a broader recognition of the importance of mental health and social support services. Advances in medical technology and healthcare delivery, including the rise of telehealth and personalized medicine, further fuel this expansion. Additionally, the sector's resilience to economic fluctuations and its capacity to innovate in response to societal health challenges contribute to its rapid growth. With an ever-growing focus on health and well-being in society, these industries are expected to continue their upward trajectory, meeting essential needs and creating numerous job opportunities.

15. The industry that will add the most jobs is individual and family services

The individual and family services industry has the highest projected growth as it is estimated to add over one million jobs between 2019 and 2029. [2] The industry that is slated to have the second highest job growth in the nation is computer systems and design which is projected to add over 574,000 jobs in the next 10 years.

The individual and family services industry, with its projection to add over 1 million jobs between 2019 and 2029 [2] , reflects a growing societal emphasis on social welfare and mental health services. This surge in job creation is likely driven by increased public awareness and acceptance of mental health issues, alongside a growing aging population requiring more in-home and community-based services. The expansion of this industry signifies a shift towards prioritizing individual and family well-being in policy and practice.

In parallel, the computer systems and design industry, projected to add over 574,000 jobs in the next decade [2] , mirrors the ongoing digital transformation across all sectors. The increasing reliance on technology in everyday life and business operations has spurred demand for professionals skilled in these areas. This trend highlights the critical role of technology and digital innovation in driving economic growth and job creation in the modern economy.

16. The average salary of a small business owner is just 16% above the annual mean wage in the U.S.

Business owners and entrepreneurs may make up some of the wealthiest people in the world; however, the average small business owner salary is just 16% above the national average mean wage of $59,428 [5] at $69,119 [6] . Of course, the salary of the average business owner varies greatly. On the low end, small business owners earn an average salary of $32,000 and earn as much as $147,000 on the average high end, according to pay rate data from Payscale.

17. Hourly earnings have increased more than 4% over the last year

Over the past year, there has been a 4.6% increase in hourly earnings, which is notably higher than the current annual inflation rate of 3.2% [2] . This disparity indicates that the average wage growth has not only kept pace with but exceeded the rate of inflation. This trend suggests that, on average, employees have experienced an increase in real purchasing power, an encouraging sign amidst broader economic challenges. However, it's important to consider that these figures are averages and may not reflect the experiences of all workers, especially in industries where wage growth has been uneven. The context of these increases amidst global economic shifts and post-pandemic recovery efforts highlights the complex interplay between wages, inflation and overall economic health.

Over the year, hourly earnings have increased by 4.6%. Meanwhile, the annual inflation rate in the U.S. over the past 12 months is 3.2%, meaning that the increase in annual earnings was proportionate to the rising inflation rate.

18. Millennials own just 13% of small businesses in the U.S.

Despite that the Millennial generation is considered to be highly entrepreneurial, Millennials own just 13% of small businesses. Meanwhile, the vast majority of small businesses are owned by Boomers and Gen X, illustrating “the generation gap” [7] in business ownership. Granted, the average age to start a business is reportedly 35 years old, so the younger generation may simply need a bit more time for the reality to catch up to their desire to own a business.

19. More small businesses are owned by males than females

While males still own a majority of small businesses, the increasing percentage of female-owned businesses, currently at 43.4% [1] , shows a positive shift towards greater gender equality in entrepreneurship. This change reflects broader societal movements towards inclusivity and the breaking down of traditional barriers in the business world. The rise in female entrepreneurship is supported by a growing number of resources and networks dedicated to supporting women in business.

Similarly, the ownership of small businesses by racial minorities and veterans, although comparatively lower, is a significant aspect of the diverse entrepreneurial ventures in the U.S. The 20.4% of small businesses owned by racial minorities and the 14.5% owned by Hispanics highlight the contributions of diverse cultural perspectives to the economy [1] . Veteran-owned businesses, at 6.1% [1] , also play a unique role, often drawing on the skills and experiences gained during military service to drive business success.

Though the gap is narrowing, females only own 43.4% of small businesses. Racial minorities own 20.4% of small businesses—of which Hispanics own 14.5%. Veterans are one of the least represented groups, owning just 6.1% of small businesses in the U.S. [1]

20. Nearly one out of three businesses still don’t have a website

In an increasingly digital age where websites are becoming easier—and more affordable—than ever to build and maintain thanks to code-free web builders and immense online resources, still, only 71% of businesses have a website [8] . Of the nearly one-third favoring website-free, 20% say they use social media in lieu of creating a website. That doesn’t mean that is a widely advisable move, however, as millions look to Google to discover businesses for anything from deciding where to grab dinner to buying an automobile.

21. Over 25% of business is conducted online

Still not sure if a business website is really quite necessary? As of 2023, there were 2.64 billion e-commerce shoppers [3] . This equated to over a quarter of all business being conducted online [9] . As the pandemic limited the movement of people, more consumers resorted to the web to shop. And not just for things such as clothes and shoes, but groceries, alcohol, prescription medications, counseling and more.

22. Over three-quarters of shoppers visit a business’s website before its physical location

Just because a business operates in-person doesn’t mean brick-and-mortars don’t need a website. In fact, 76% [10] of online shoppers reportedly check a business’s website before visiting their physical store or location. As surprising as this may initially be, the reality is that the web has become consumers’ first stop. And this is good news for brick-and-mortar businesses because it means that you don’t have to depend solely on foot traffic or word of mouth to get customers or clients through your doors.

Start an LLC Online Today With ZenBusiness

Click on the state below to get started.

23. Labor remains the number one cost for businesses at 70% of spending

For most businesses, the biggest cost is labor. It makes up 70% of a business’s spending [11] , taking up a large piece of the pie. For this reason, it’s not surprising then that one of the first areas a business looks to save money on is labor costs, whether that’s through layoffs, outsourcing to more affordable staff overseas or employing software that helps reduce the number of hands on deck a business needs to operate.

24. Inventory is the second biggest cost for small businesses

On average, the next biggest cost behind labor for businesses is inventory, which makes up an average of 25% to 35% of a business’s budget [12] . Though inventory should equate to revenue down the line, it does represent a large upfront cost for small businesses that may be on a tight budget. For this reason, the popularity of dropshipping continues to grow, as do smaller minimum quantity orders to help reduce the upfront investment and the space required for storage—never mind the chances of damage or inventory spoiling.

25. Marketing accounts for just 9% of a business’s revenue on average

It’s common to hear of astronomical advertising budgets and campaign spending, and yet advertising makes up just 1% of the average business’s revenue [13] . One of the most popular advertising channels, with 83% [3] of businesses using it, is now social media. This is likely due to the value of a pay-per-click-based ad platform where advertisers only pay when users interact with their ad, the ease of use across said platforms and the sheer accessibility they offer to businesses of all sizes and budgets.

26. Small Business Spending Adjustments in Response to 3% Inflation Rise

As the economic environment continues to evolve, small businesses face the challenge of adapting to inflationary pressures. According to the CPI inflation calculator [2] , $1 in November 2022 is equivalent to $1.03 in November 2023, indicating a noticeable rise in costs over the year. This increase affects various aspects of running a business, from payroll and material costs to utilities and property taxes.

In response to these growing expenses, many small businesses have been reevaluating and adjusting their spending strategies. While specific data from 2022 showed that over half of small businesses cut costs, the trend likely persists as businesses seek innovative ways to maintain financial stability. This includes adopting remote work models to reduce office expenses, seeking more cost-effective manufacturing or supply options and leveraging technology such as artificial intelligence to boost productivity and reduce operational downtime. These measures reflect not just a reaction to the immediate challenges of inflation but also a strategic shift towards greater operational efficiency and resilience in a fluctuating economic climate.

27. Over 180,000 more small businesses opened than closed in the last year

From March 2021 to March 2022, approximately 1.4 million new small businesses opened, according to data from the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) [1] . That is 447,519 more small businesses that opened within this timeframe than closed. This increase shows positive growth towards business ownership, and the shift towards entrepreneurship following the pandemic and tremendous job loss.

28. One in five businesses fail within the first year

Chances are you’re familiar with the statistic that half of all businesses fail. However, this only paints a partial picture. To get the complete picture, it should be noted that 20% of businesses fail in the first year, 30% in the second year and 50% by year five [15] . This illustrates how pivotal the first five years of business are for new ventures.

29. Businesses are most likely to fail from running out of capital

A significant factor in the failure of new businesses is financial challenges. Data shows that 38% of businesses fail due to exhausting their cash reserves or the inability to secure additional capital. This points to the essential role of financial management in the survival and growth of startups and young companies.

In comparison, 42% of businesses that close within the first five years do so because of inadequate market demand [16] . However, the issue of capital is not merely about having funds; it's about managing these resources effectively to reach and engage the target market. For entrepreneurs, this means balancing the act of capturing market demand with maintaining robust financial health to ensure long-term business sustainability.

30. Lack of market need is the second most common reason small businesses fail

Following closely behind financial challenges, the second most common reason for small business failure is insufficient market demand, accounting for a significant portion of closures. While 38% of small businesses struggle due to running out of capital [16] , the lack of market need presents an equally pressing challenge. For a small business to be successful, it's imperative not only to have adequate capital to sustain operations in the early stages but also to ensure there is a consistent and growing demand for its products or services.

31. The construction industry has the highest failure rate

When examining failure rates by industry, the construction sector stands out with the highest rate of business failures, at 25% in the first year [17] . This high failure rate in construction may stem from various factors inherent to the industry, such as the complexity of projects, fluctuating material costs and the need for skilled labor. Additionally, the industry's sensitivity to economic cycles and changes in real estate demand can add to the challenges faced by new businesses. These dynamics illustrate the unique pressures within the construction sector, requiring businesses to navigate a range of operational and financial challenges from the outset.

32. The industries with the highest survival rate are healthcare and social assistance

Contrasting with other sectors, businesses in the healthcare and social assistance industries show remarkable resilience, boasting the highest survival rates [17] . This durability can be attributed to factors such as consistent demand for health and social services, regardless of economic fluctuations. The essential nature of services provided, ranging from medical care to social work, ensures a steady need, contributing to the longevity of businesses in this sector. Additionally, advancements in medical technology and an increasing focus on health and well-being across populations further support the growth and sustainability of these industries. The healthcare and social assistance sector's ability to adapt to changing demographics and health needs plays a significant role in its stability and enduring success.

On the other end of the spectrum, the healthcare and social assistance industries have the highest survival rates. [17]

Small businesses can glean a lot of insight by looking at business statistics. Not only does data help provide intel on the general business climate—the one in which all businesses operate within, but statistics can also be leveraged to enable businesses to better plan for the future based on the direction in which the data is pointing to. Of course, while every business will potentially interpret and apply the data differently, this is exactly what can help give one small business a leg up on those that do not.

To compile our list of the top small business statistics of 2024, we went directly to the information powerhouses, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the United States Small Business Administration (SBA) to acquire and analyze available data. We considered the source quality, relevance and timeliness of the data to present, compare, contrast and overlay data to create more useful insights for small businesses.

Visit our hub to view more statistics pages .

- U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

- Forbes Advisor

- Guidant Financial

- Visual Objects

- Best LLC Services

- Best Registered Agent Services

- Best Trademark Registration Services

- Top LegalZoom Competitors

- Best Business Loans

- Best Business Plan Software

- ZenBusiness Review

- LegalZoom LLC Review

- Northwest Registered Agent Review

- Rocket Lawyer Review

- Inc. Authority Review

- Rocket Lawyer vs. LegalZoom

- Bizee Review (Formerly Incfile)

- Swyft Filings Review

- Harbor Compliance Review

- Sole Proprietorship vs. LLC

- LLC vs. Corporation

- LLC vs. S Corp

- LLP vs. LLC

- DBA vs. LLC

- LegalZoom vs. Incfile

- LegalZoom vs. ZenBusiness

- LegalZoom vs. Rocket Lawyer

- ZenBusiness vs. Incfile

- How To Start A Business

- How to Set Up an LLC

- How to Get a Business License

- LLC Operating Agreement Template

- 501(c)(3) Application Guide

- What is a Business License?

- What is an LLC?

- What is an S Corp?

- What is a C Corp?

- What is a DBA?

- What is a Sole Proprietorship?

- What is a Registered Agent?

- How to Dissolve an LLC

- How to File a DBA

- What Are Articles Of Incorporation?

- Types Of Business Ownership

Next Up In Company Formation

- Best Online Legal Services

- How To Write A Business Plan

- Member-Managed LLC Vs. Manager-Managed LLC

- Starting An S-Corp

- LLC Vs. C Corp

- How Much Does It Cost To Start An LLC?

Best West Virginia Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best Vermont Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best Rhode Island Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best Wisconsin Registered Agent Services Of 2024

Best South Dakota Registered Agent Services Of 2024

B2B Marketing In 2024: The Ultimate Guide

Kelly Main is a Marketing Editor and Writer specializing in digital marketing, online advertising and web design and development. Before joining the team, she was a Content Producer at Fit Small Business where she served as an editor and strategist covering small business marketing content. She is a former Google Tech Entrepreneur and she holds an MSc in International Marketing from Edinburgh Napier University. Additionally, she is a Columnist at Inc. Magazine.

The Ultimate Guide to Market Research for Small Businesses

- by Alice Ananian

- June 26, 2024

Starting a business is an exciting venture but also a challenging one. One of the most crucial steps in this journey is conducting thorough market research. Understanding your market is key to making informed decisions, developing effective strategies, and ultimately achieving success. In this ultimate guide, we’ll explore why market research is essential, how to do it, the tools you’ll need, and how prelaunch activities can offer valuable insights.

Why You Need to Conduct Market Research

Imagine launching a product or service into a black box. You have no idea who your ideal customer is, what their needs are, or even if there’s a market for what you’re offering. Yikes! This is where market research comes in.

Think of market research as your business’s roadmap to success. By gathering data and insights about your target audience and the competitive landscape, you can make informed decisions about everything from product development to marketing strategies. Here are some key reasons why market research is essential:

Know Your Customer: Understanding your target audience’s demographics, needs, preferences, and buying behaviors allows you to tailor your offerings directly to them.

Identify Opportunities: Market research can reveal gaps in the market or unmet customer needs. This can spark innovative ideas for new products or services.

Stay Competitive: Knowing your competition’s strengths and weaknesses helps you differentiate your brand and develop a winning strategy.

Reduce Risk: Market research can help you identify potential challenges before you invest heavily in product development or marketing campaigns.

Measure Success: By tracking market trends and customer feedback, you can gauge the effectiveness of your strategies and make adjustments as needed.

In short, market research is an investment that can pay off significantly. It equips you with the knowledge and insights you need to navigate the ever-changing marketplace and achieve sustainable growth.

How to Do Market Research for a Small Business

So, you’re convinced of the importance of market research, but where do you begin? This step-by-step guide will equip you with the tools to conduct effective market research on a budget:

Step 1: Define Your Research Goals

Before diving in, identify what you want to achieve. Are you trying to understand customer needs for a new product? Maybe you want to analyze the effectiveness of your current marketing strategy. Having clear goals keeps your research focused and helps you choose the most relevant methods.

Step 2: Leverage Secondary Research (Free or Low-Cost)

Secondary research involves utilizing existing data collected by others. This is a fantastic way to gain a broad understanding of your market landscape without breaking the bank. Here are some resources:

Government Websites: The U.S. Small Business Administration provides a wealth of free market research tools and industry reports.

Industry Associations: Many industry associations publish reports and data on market trends, demographics, and competitor analysis. Consider the list below as a starting point and adjust it based on your particular niche:

American Marketing Association (AMA)

- Focus: Marketing trends, consumer behavior, and advertising effectiveness.

- Publications: Journal of Marketing , Marketing News

National Retail Federation (NRF)

- Focus: Retail industry trends, consumer behavior, and sales data.

- Publications: NRF Retail Sales Report , Consumer View

International Data Corporation (IDC)

- Focus: Technology market trends, IT spending, and competitive analysis.

- Publications: Worldwide Quarterly PC Tracker , IT Market Reports

Consumer Technology Association (CTA)

- Focus: Consumer electronics and technology trends.

- Publications: Consumer Technology Ownership and Market Potential Study

National Association of Realtors (NAR)

- Focus: Real estate market trends, housing statistics, and buyer/seller demographics.

- Publications: Existing Home Sales , NAR Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers .

Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO)

- Focus: Biotechnology industry trends, research and development, and market data.

- Publications: BIO Industry Analysis Reports , Emerging Therapeutic Company Investment Report .

Gartner, Inc.

- Focus: Technology market trends, IT spending, and strategic insights.

- Publications: Gartner Magic Quadrant

World Travel & Tour i sm Council (WTTC)

- Focus: Global travel and tourism trends, economic impact, and market analysis.

- Publications: WTTC Economic Impact Reports , Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report .

Food Marketing Institute (FMI)

- Focus: Food retail industry trends, consumer shopping behavior, and sales data.

- Publications: The Food Retailing Industry Speaks , U.S. Grocery Shopper Trends .

Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)

- Focus: Computing and IT industry trends, research developments, and technological advancements.

- Publications: Communications of the ACM, ACM Transactions on Computer Systems

International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC)

Focus: Shopping center industry trends, retail real estate, and consumer behavior.

Publications: ICSC Research Reports , Shopping Centers: America’s First and Foremost Marketplace .

Market Research Reports: Public libraries often offer access to subscription-based market research databases, allowing you to download relevant reports. Visit your local library to find out what resources they have.

Step 3: Conduct Primary Research to Gather Specific Insights

Secondary research provides a foundation, but primary research allows you to delve deeper into your target audience’s thoughts and behaviors. Here are some cost-effective methods to consider:

Online Surveys: Free survey tools like Google Forms or SurveyMonkey allow you to gather feedback from a large pool of potential customers. Keep your surveys concise and easy to complete to ensure a high response rate.

Social Media Listening: Tools like Brandwatch or Hootsuite allow you to track conversations about your industry or brand on social media platforms. This can reveal valuable insights into customer sentiment and preferences. Also consider using this AI Market Research tool that gathers information on competitor products from Amazon, analyzes their feedback, and gives you a summary with all the juicy details that will help you create a product your customers will love.

Focus Groups: Gather a small group of potential customers for a moderated discussion about your product, service, or industry. This allows for in-depth exploration of their thoughts and experiences. For more information on conducting focus groups, click here .

Pro tip: Gathering primary resources is easier said than done, so we recommend on using tools that pool the resources for you. For example, when it comes to online surveys Prelaunch is a concept validation platform that lets you develop a landing page to test the waters for a product your considering on selling.

Here, you’ll see how people react, what comments they have, if there is adequate market demand, and even how much people are willing to pay. A quick embedded survey is posed both to those who showed interest in your product and – wait for it – those who were even willing to pay a special price for it before you created it.

Step 4: Analyze Your Findings and Draw Conclusions

Once you’ve collected your data, it’s time to make sense of it all. Organize your findings from both secondary and primary research. Look for patterns, trends, and recurring themes. What do these insights tell you about your target market and your competitive landscape?

Not sure you have time for all that? You’re not the only one. That’s why Prelaunch compiles all the info derived from your primary sources into a single Dashboard that clearly breaks down who your customers are and what they want.

Step 5: Take Action and Refine

Use your market research to inform your business decisions. This could involve modifying your product or service offering, developing targeted marketing campaigns, or adjusting your pricing strategy. Remember, market research is an ongoing process. As your business evolves, revisit your research and adapt your strategies based on new data and market trends.

That’s why we always say Prelaunch as soon as possible. Even if you only have quality rendered images of your product, imagine how much your prototype could improve if your customers pointed out your blind spots beforehand. Having a landing page that interested people visit and tracking what they have to say is a solid place to start from.

Market Research Tools for Small Businesses

Several tools can simplify and enhance your market research efforts. Here are some must-haves for small businesses:

Survey Tools

- SurveyMonkey : A popular and easy-to-use tool that allows you to create surveys, quizzes, and polls. It offers a free plan with limited features and paid plans with more advanced features such as branching logic and skip logic.

- Typeform : Another user-friendly survey tool that allows you to create visually appealing surveys. It offers a free plan with limited features, and paid plans with more advanced features such as logic jumps and custom branding.

- Prelaunch : The platform does not have surveys as a separate feature per say, but rather makes a few targeted question an embedded part of the process when users visit a product’s landing page.

- Google Forms : A free survey tool from Google that is easy to use and integrates seamlessly with other Google products. It is a good option for simple surveys with a limited number of questions.

Social Media Listening Tools

- Brandwatch : A powerful social listening tool that allows you to track brand mentions, analyze sentiment, and identify influencers. It offers a free trial, but paid plans are required for access to most features.

- Hootsuite : A social media management tool that also offers social listening capabilities. It allows you to track brand mentions, analyze sentiment, and schedule social media posts. It offers a free plan with limited features, and paid plans with more advanced features.

- AI Market Research Tool by Prelaunch : This tool can analyze thousands of reviews and feedback on Amazon to uncover the top customer praises and complaints.

- Sprout Social : Another social media management tool that offers social listening capabilities. It allows you to track brand mentions, analyze sentiment, and engage with customers on social media. It offers a free trial, but paid plans are required for access to most features.

Website Analytics Tools

- Google Analytics : A free website analytics tool from Google that provides insights into website traffic, user behavior, and conversions. It is a must-have tool for any small business with a website.

- Hotjar : A website heatmap and analytics tool that allows you to see how visitors are interacting with your website. It offers a free plan with limited features, and paid plans with more advanced features such as session recordings and form analytics.

- Crazy Egg : Another website heatmap and analytics tool that allows you to see how visitors are interacting with your website. It offers a free trial, but paid plans are required for access to most features.

- Ahrefs : A powerful SEO tool that allows you to track keywords, analyze backlinks, and conduct competitor analysis. It offers a free trial, but paid plans are required for access to most features.

- SEMrush : Another powerful SEO tool that offers similar features to Ahrefs. It offers a free trial, but paid plans are required for access to most features.

- Moz : An SEO tool that offers a variety of features, including keyword research, backlink analysis, and on-page optimization tools. It offers a free plan with limited features, and paid plans with more advanced features.

These are just a few of the many market research tools available for small businesses. The best tool for you will depend on your specific needs and budget. Be sure to research different tools and compare features before making a decision.

Conducting market research is a vital step for small businesses and entrepreneurs. It provides the data and insights needed to make informed decisions, understand your target audience, identify opportunities, and gain a competitive advantage. By following the steps outlined in this guide and utilizing the recommended tools, you can conduct effective market research and set your business up for success.

Remember, market research is an ongoing process. Continuously gather and analyze data to stay ahead of trends and adapt to changing market conditions. And don’t forget to leverage prelaunch activities to refine your product and marketing strategies.

1. What is market research?

Market research is the process of gathering information about your target market, competitors, and the overall industry landscape. This information can be used to make informed business decisions about everything from product development and pricing to marketing strategies and sales tactics.

2. Why is market research important?

Market research is crucial for small businesses because it helps you:

- Understand your customers: Identify their needs, preferences, and buying behaviors.

- Identify opportunities: Discover gaps in the market or unmet customer needs that your business can address.

- Stay competitive: Analyze your competition’s strengths and weaknesses to differentiate your brand and develop a winning strategy.

- Reduce risk: Make informed decisions to avoid costly mistakes in product development or marketing campaigns.

- Measure success: Track market trends and customer feedback to gauge the effectiveness of your strategies and make adjustments as needed.

3. How much does market research cost for a small business?

Market research can be conducted on a budget. Here’s a breakdown of costs:

- Free or Low-Cost Options: Utilize free government resources, industry reports, and online survey tools like Google Forms.

- Moderate Cost: Consider social listening tools with free trials or student research partnerships with universities. Another option is to use tools that combine things like social listening and primary research in one like Prelaunch.

- Higher Cost: Invest in professional market research agencies for in-depth studies, but this might not be necessary for every small business.

Remember, effective market research doesn’t have to be expensive. By being resourceful and focusing on your specific needs, you can gain valuable insights to propel your small business forward.

4. What are some common market research methods for small businesses?

Secondary Research: Leverage existing data from government websites, industry associations, and market research reports.

Surveys & Online Polls: Gather feedback from a large pool of potential customers through free survey tools.

Social Media Listening: Track brand mentions and analyze customer sentiment on social media platforms.

Focus Groups: Conduct moderated discussions with a small group of potential customers to gain in-depth insights.

Website Analytics: Utilize tools like Google Analytics to understand website traffic, user behavior, and conversions.

Alice Ananian

Alice has over 8 years experience as a strong communicator and creative thinker. She enjoys helping companies refine their branding, deepen their values, and reach their intended audiences through language.

Related Articles

Comprehensive Guide to Market Research Types and Methods

- April 1, 2024

Market Segmentation Analysis in 2024: The Ultimate Guide

21 Best Market Research Resources for Small Businesses

Noah Parsons

8 min. read

Updated May 10, 2024

When you’re starting your business , you need to have a deep understanding of your customers. In fact, knowing your customers inside and out is probably the most important key to success.

Your customers are the people who desperately need your product or service. You need to know who they are, why they want your solution, what they like and dislike, and even what they had for breakfast. Knowing all of this will help you find more customers and build a better product that your customers will clamor to buy and tell their friends and colleagues about.

This is where market research comes in.

- What is market research?

Market research is the process of gaining information about your target market —a fancy way of saying “getting to know your customers.” Ideally, you find specific information about your target market and the key factors that influence their buying decisions. This is a key step in your larger market analysis.

As you get started, you’ll need to determine what type of market research is going to work best for you. Make that decision based on the value of the insights you think you’ll gain, versus the time and effort you need to invest to find the information.

Market research is often confused with an elaborate process conducted by fancy consultants that takes a tremendous amount of time and money. That’s certainly not true. You can, and should, do most of your own market research, and it doesn’t even have to be that hard.

After I explain the different types of market research, I’ll share all the resources you can use to do your own.

- Types of market research explained

1. Primary market research

Primary market research is research that you conduct yourself, rather than information that you find that’s already published. You gather this information by talking directly with your potential customers. This can either be exploratory research, where you ask open-ended questions, or specific research, where you try to obtain quantifiable results.

Here are a few methods you can use to conduct primary research.

Conduct focus groups

A focus group requires you to gather a small group of people together for a discussion with an assigned leader.

Survey your customers

Distribute these both to existing customers and potential customers. Sending out a survey using tools like SurveyMonkey is a great way to collect this type of information from current or potential customers of your business. You can even run tiny surveys right on your website with services like Qualaroo . Make sure to ask specific questions—but try not to lead people toward the answer you want to hear. Be as objective as you can.

Brought to you by

Create a professional business plan

Using ai and step-by-step instructions.

Secure funding

Validate ideas

Build a strategy

Assess your competition

Look at your competition’s solutions, technologies, and what niche they occupy. This can help you better understand their position in the market and how you can compete. Complete a competitive matrix or SWOT Analysis to streamline your competitive analysis.

Hold one-on-one interviews

Find potential customers and talk with them about their problems and your solutions to those problems. Ideally, conduct these in-depth interviews in your customer’s workplace, or wherever they will be when they might consider shopping for your solution. You can also just ask to conduct these interviews remotely.

2. Secondary market research

Market research may also come from secondary sources. This is information others have already acquired and published about customers in your industry.

Access to this secondary market research data may be yours for the asking, and cost you only an email, letter, or phone call. Much of it is entirely free and easily available online. Here are a few ways to gather secondary market research.

Trade associations

Trade associations are organizations that serve specific industries. There’s almost certainly one for your industry. Once you find it, contact them and ask them for information about their industry and markets in the industry.

Government information

The U.S. government has a treasure trove of information to wade through. The data is all free but may take a little bit of time to find.

Third-party research sites

For reasonable fees, there are market research companies that will sell you pre-written industry reports that provide information on industries and their target markets.

- Best market research resources

There’s so much information out there that it can be difficult to know where to start with your market research. Here are our favorite resources for doing market research.

U.S. government resources

If your business is operating within or expanding to the United States, these are the top sites you should use for your research.

- U.S. Census : This is a great starting point for data about the U.S. population. You can drill into the data and find out nearly anything you want to know about different locations and demographics.

- Census Business Builder : Beyond population data, you can look at how much people in your industry spend.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics : A fantastic site for information on specific industries, like hiring and expense trends as well as industry sizes. If your target market is other businesses, this is a good place to look for data.

- Consumer Expenditure Survey : If you want to know what people spend their money on, this is your go-to source.

- CensusViewer : While it’s not a U.S. government resource, this free tool leverages US Census data and other data sources to give you access to data in an easy-to-use format that you can explore both visually on a map or in data reports for cities, counties, and entire states.

- Economic Indicators : Offers free economic, demographic, and financial information.

- Pew Research Center: A nonpartisan fact tank that was founded with the mission of informing the public about the issues, attitudes, and trends shaping the world. They conduct public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis, and other data-driven social science research.

Industry summaries

If you’re looking for information about specific industries, these are some of the best options to look into.

- SBDCNet Business Snapshots : You’ll find a great collection of industry profiles that describe how industries are growing and changing, who their customers are, and what typical startup costs are. You should also check out their list of market research resources, sorted by industry .

- Hoovers Industry Research : While not a free resource, the industry summary data provided here can be helpful if you need in-depth industry reports.

- IBISWorld: Regularly updated industry reports, that provide insight regarding the current status, market outlook, and competitive landscape of a given industry. It is a subscription service, but you can download free reports to test it out.

Business location market research tools

Interested in learning more about the demographics and customer base in a given geographic location? Check out these resources.

- ZoomProspector : This tool can help you find the ideal location for your business, or find new locations similar to where you already are for expansion and growth.

- MyBestSegments : This tool from Nielsen is a great resource for finding out what demographic and psychographic groups live in a given zip code or where the highest concentration of a given segment lives. While the most detailed data is not free, you can get a lot of great insights from the free version.

- SizeUp: This is a useful mapping tool to help determine where your target customers are. It’s very useful to help you determine the ideal location for your business.

Survey tools

If you plan on conducting primary research, here are some of the surveying tools you should look into.

- SurveyMonkey : Should you need to poll a group for business purposes, SurveyMonkey is free and reliable. Simply build the survey and send it out to your audience.

- Google Consumer Surveys : You don’t need to have a contact list to send out a survey on this site. With Google Surveys, you can target users from around the web and get instant feedback on your business idea.

- TypeForm : Whether you need a simple form or a survey, TypeForm does it beautifully. It’s especially good on mobile.

- Qualaroo : If you run a website and want to get quick feedback from the people that are already showing up there, Qualaroo is a great tool for this purpose.

Trade and industry associations

Many industries are blessed with an active trade association that serves as a vital source of industry-specific information. Such associations regularly publish directories for their members, and the better ones publish statistical information that tracks industry sales, profits, ratios, economic trends, and other valuable data.

- Wikipedia’s list of U.S. trade groups : This is a fairly comprehensive list to kickstart your research.

- Directory of Associations : Another long list of associations. You should be able to find an association for your industry here.

Market trends

- Google Trends : Use Google Trends to discover what people are searching on and how search volume on important topics is changing over time.

- Statista : If you’re looking for statistics and trends, Statista is a great place to get started. You’ll find data on virtually everything here.

- Leverage market research to inform your business decisions

Doing market research is a powerful way to reduce the risk for your small business or startup. The more you know about your customers and your industry, the less likely you are to waste money on marketing and advertising campaigns that don’t reach the right people.

You probably already have a gut feeling about who your customers are and what their needs and pain points are. But taking the time to validate (or invalidate) your assumptions can make a big difference to your company’s bottom line and long-term viability.

Noah is the COO at Palo Alto Software, makers of the online business plan app LivePlan. He started his career at Yahoo! and then helped start the user review site Epinions.com. From there he started a software distribution business in the UK before coming to Palo Alto Software to run the marketing and product teams.

Table of Contents

Related Articles

8 Min. Read

How to Create a Market Penetration Strategy — 2024 Guide

12 Min. Read

6 Things to Consider Before Entering a Market

6 Min. Read

10 Ways to Find out What Your Competitors Are Doing

4 Min. Read

Industry Research Versus Market Research: What’s the Difference?

The Bplans Newsletter

The Bplans Weekly

Subscribe now for weekly advice and free downloadable resources to help start and grow your business.

We care about your privacy. See our privacy policy .

The quickest way to turn a business idea into a business plan

Fill-in-the-blanks and automatic financials make it easy.

No thanks, I prefer writing 40-page documents.

Discover the world’s #1 plan building software

Need a hand creating engaging content? Try Buffer for free →

How to Do Market Research for Small Businesses

Market research is the process of organizing information about your target audience. It’s the single most important thing you can do to attract and delight customers, launch high-value products, and maintain a competitive edge. But, when you’re a small business owner, you’re juggling so many responsibilities that market research gets put on the backburner. Big businesses spend months and huge budgets to understand their customers, but small business owners have to be thriftier to understand their customers without access to big-budget resources. In this guide, we break down exactly how you can conduct market research to grow your small business with minimal investments in time and budget.

Define your buyer personas

A buyer persona is a fictional, descriptive profile used to target people most likely to become loyal customers. Buyer personas tell you who your customers are, their interests, behaviors, and spending patterns. Understanding your customers as humans and not just a set of data helps you to create content and messaging tailored to their specific needs. For example, if you own a dog food company, your buyer persona might highlight someone named “Eric.” Eric is 36 years old and works as a field engineer in Indianapolis. He wants to keep his dog healthy, but his job is stressful and time-consuming, so he doesn’t have a lot of time to take his dog on walks. Eric needs to buy dog food he can trust to be made with whole foods, tastes good to his pet, and is affordable for his income level.

Even though the person in your buyer persona isn’t real, you want to treat them as a model customer. Give them a name, and add details about their life like age, location, interests, and buying behaviors. If it’s helpful, you can also find a stock photo of a person who embodies your ideal customer as a handy visual. Be sure to include common pain points faced by your persona, so you can determine any niche markets your product can fill. Aim to keep your buyer personas limited to no more than five. Having more than one type of buyer persona is perfectly fine, but it's important you’re realistic about who you're able to effectively reach when developing a marketing campaign.

Analyze your competition

Competitor analysis is an exercise in unpacking who your top competitors are and what makes them successful (or not successful) in engaging with your potential customers. Understanding the ways other businesses are successful will help you make informed decisions and identify ways you can outperform the competition. Conducting a competitor analysis involves a little bit of research. Get started by identifying both local and online businesses that compete with your own. Comb through their website and other marketing channels to examine their customer-facing experience, taking a close look at:

- Website performance: Do the pages load quickly? Is it easy to navigate?

- Social media platforms: How do they engage with their followers?

- Pricing structure: How much do they charge for products and services? Are their prices appropriate for the audience?

- Reviews: How do their customers feel about them? Keep in mind businesses with higher reviews are your stronger competitors.

Gather information about your competitors with our Competitor Analysis Google Sheets template , using it to pinpoint trends and see comparisons between businesses.

Ask your most loyal customers what they love about your business

One valuable way to learn what’s working, or not working, among your most valuable customers is to go straight to the source: the people who are already buying from you. These are the people who embody your ideal customer base. We’re willing to bet these customers also look a lot like one of your buyer personas. Luckily, with the advent of social media and digital technology, it’s easy and cost-effective to talk with customers directly.

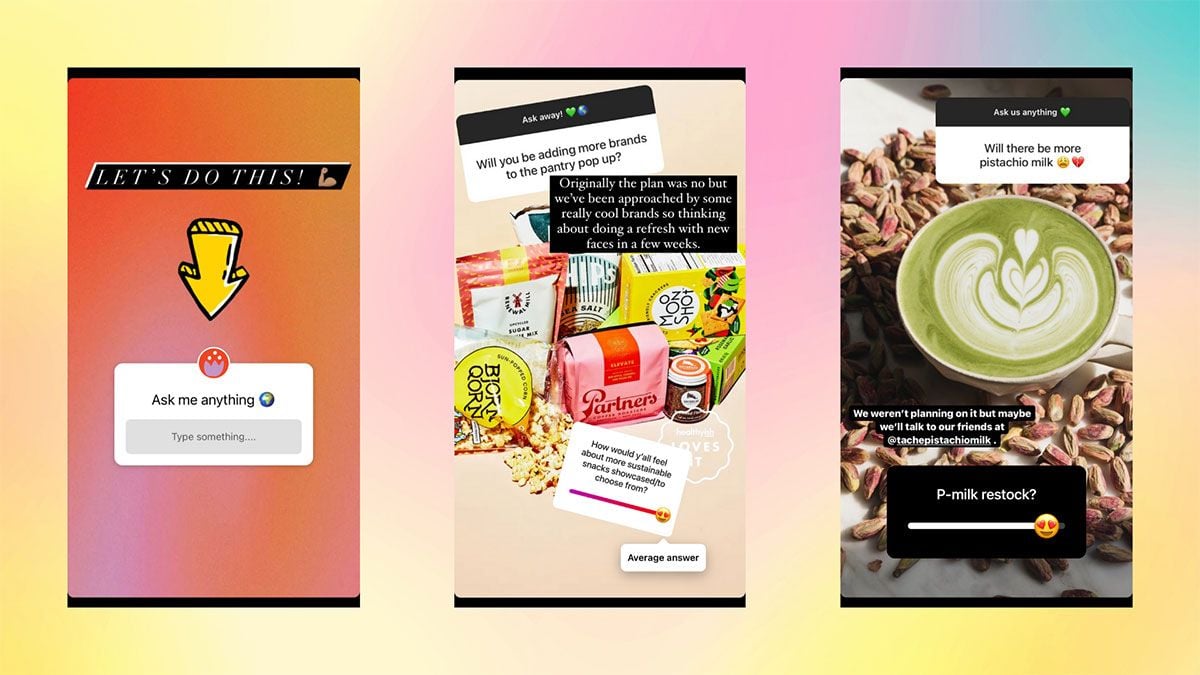

Ask for customer feedback with surveys