- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Science, health, and public trust.

September 8, 2021

Explaining How Research Works

We’ve heard “follow the science” a lot during the pandemic. But it seems science has taken us on a long and winding road filled with twists and turns, even changing directions at times. That’s led some people to feel they can’t trust science. But when what we know changes, it often means science is working.

Explaining the scientific process may be one way that science communicators can help maintain public trust in science. Placing research in the bigger context of its field and where it fits into the scientific process can help people better understand and interpret new findings as they emerge. A single study usually uncovers only a piece of a larger puzzle.

Questions about how the world works are often investigated on many different levels. For example, scientists can look at the different atoms in a molecule, cells in a tissue, or how different tissues or systems affect each other. Researchers often must choose one or a finite number of ways to investigate a question. It can take many different studies using different approaches to start piecing the whole picture together.

Sometimes it might seem like research results contradict each other. But often, studies are just looking at different aspects of the same problem. Researchers can also investigate a question using different techniques or timeframes. That may lead them to arrive at different conclusions from the same data.

Using the data available at the time of their study, scientists develop different explanations, or models. New information may mean that a novel model needs to be developed to account for it. The models that prevail are those that can withstand the test of time and incorporate new information. Science is a constantly evolving and self-correcting process.

Scientists gain more confidence about a model through the scientific process. They replicate each other’s work. They present at conferences. And papers undergo peer review, in which experts in the field review the work before it can be published in scientific journals. This helps ensure that the study is up to current scientific standards and maintains a level of integrity. Peer reviewers may find problems with the experiments or think different experiments are needed to justify the conclusions. They might even offer new ways to interpret the data.

It’s important for science communicators to consider which stage a study is at in the scientific process when deciding whether to cover it. Some studies are posted on preprint servers for other scientists to start weighing in on and haven’t yet been fully vetted. Results that haven't yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny should be reported on with care and context to avoid confusion or frustration from readers.

We’ve developed a one-page guide, "How Research Works: Understanding the Process of Science" to help communicators put the process of science into perspective. We hope it can serve as a useful resource to help explain why science changes—and why it’s important to expect that change. Please take a look and share your thoughts with us by sending an email to [email protected].

Below are some additional resources:

- Discoveries in Basic Science: A Perfectly Imperfect Process

- When Clinical Research Is in the News

- What is Basic Science and Why is it Important?

- What is a Research Organism?

- What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?

- Basic Research – Digital Media Kit

- Decoding Science: How Does Science Know What It Knows? (NAS)

- Can Science Help People Make Decisions ? (NAS)

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

2.1 Why Is Research Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( Figure 2.2 ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behavior is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behavior by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades. Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores (Shaw & Tan, 2015). Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills (Massimini & Peterson, 2009). Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student's acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children's development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life (Blann, 2005). While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective (Neil & Christensen, 2009; Peters-Scheffer, Didden, Korzilius, & Sturmey, 2011). While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants (Barnett, 2011). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about early childhood program effectiveness to learn how scientists evaluate effectiveness and how best to invest money into programs that are most effective.

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine that your sister, Maria, expresses concern about her two-year-old child, Umberto. Umberto does not speak as much or as clearly as the other children in his daycare or others in the family. Umberto's pediatrician undertakes some screening and recommends an evaluation by a speech pathologist, but does not refer Maria to any other specialists. Maria is concerned that Umberto's speech delays are signs of a developmental disorder, but Umberto's pediatrician does not; she sees indications of differences in Umberto's jaw and facial muscles. Hearing this, you do some internet searches, but you are overwhelmed by the breadth of information and the wide array of sources. You see blog posts, top-ten lists, advertisements from healthcare providers, and recommendations from several advocacy organizations. Why are there so many sites? Which are based in research, and which are not?

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

NOTABLE RESEARCHERS

Psychological research has a long history involving important figures from diverse backgrounds. While the introductory chapter discussed several researchers who made significant contributions to the discipline, there are many more individuals who deserve attention in considering how psychology has advanced as a science through their work ( Figure 2.3 ). For instance, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) was the first woman to earn a PhD in psychology. Her research focused on animal behavior and cognition (Margaret Floy Washburn, PhD, n.d.). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was a preeminent first-generation American psychologist who opposed the behaviorist movement, conducted significant research into memory, and established one of the earliest experimental psychology labs in the United States (Mary Whiton Calkins, n.d.).

Francis Sumner (1895–1954) was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in 1920. His dissertation focused on issues related to psychoanalysis. Sumner also had research interests in racial bias and educational justice. Sumner was one of the founders of Howard University’s department of psychology, and because of his accomplishments, he is sometimes referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology.” Thirteen years later, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895–1934) became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in psychology. Prosser’s research highlighted issues related to education in segregated versus integrated schools, and ultimately, her work was very influential in the hallmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional (Ethnicity and Health in America Series: Featured Psychologists, n.d.).

Although the establishment of psychology’s scientific roots occurred first in Europe and the United States, it did not take much time until researchers from around the world began to establish their own laboratories and research programs. For example, some of the first experimental psychology laboratories in South America were founded by Horatio Piñero (1869–1919) at two institutions in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Godoy & Brussino, 2010). In India, Gunamudian David Boaz (1908–1965) and Narendra Nath Sen Gupta (1889–1944) established the first independent departments of psychology at the University of Madras and the University of Calcutta, respectively. These developments provided an opportunity for Indian researchers to make important contributions to the field (Gunamudian David Boaz, n.d.; Narendra Nath Sen Gupta, n.d.).

When the American Psychological Association (APA) was first founded in 1892, all of the members were White males (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.). However, by 1905, Mary Whiton Calkins was elected as the first female president of the APA, and by 1946, nearly one-quarter of American psychologists were female. Psychology became a popular degree option for students enrolled in the nation’s historically Black higher education institutions, increasing the number of Black Americans who went on to become psychologists. Given demographic shifts occurring in the United States and increased access to higher educational opportunities among historically underrepresented populations, there is reason to hope that the diversity of the field will increasingly match the larger population, and that the research contributions made by the psychologists of the future will better serve people of all backgrounds (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.).

The Process of Scientific Research

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas ( Figure 2.4 ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure 2.5 .

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable , or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors ( Figure 2.6 ). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/2-1-why-is-research-important

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

What Is the Importance of Research? 5 Reasons Why Research is Critical

by Logan Bessant | Nov 16, 2021 | Science

Most of us appreciate that research is a crucial part of medical advancement. But what exactly is the importance of research? In short, it is critical in the development of new medicines as well as ensuring that existing treatments are used to their full potential.

Research can bridge knowledge gaps and change the way healthcare practitioners work by providing solutions to previously unknown questions.

In this post, we’ll discuss the importance of research and its impact on medical breakthroughs.

The Importance Of Health Research

The purpose of studying is to gather information and evidence, inform actions, and contribute to the overall knowledge of a certain field. None of this is possible without research.

Understanding how to conduct research and the importance of it may seem like a very simple idea to some, but in reality, it’s more than conducting a quick browser search and reading a few chapters in a textbook.

No matter what career field you are in, there is always more to learn. Even for people who hold a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in their field of study, there is always some sort of unknown that can be researched. Delving into this unlocks the unknowns, letting you explore the world from different perspectives and fueling a deeper understanding of how the universe works.

To make things a little more specific, this concept can be clearly applied in any healthcare scenario. Health research has an incredibly high value to society as it provides important information about disease trends and risk factors, outcomes of treatments, patterns of care, and health care costs and use. All of these factors as well as many more are usually researched through a clinical trial.

What Is The Importance Of Clinical Research?

Clinical trials are a type of research that provides information about a new test or treatment. They are usually carried out to find out what, or if, there are any effects of these procedures or drugs on the human body.

All legitimate clinical trials are carefully designed, reviewed and completed, and need to be approved by professionals before they can begin. They also play a vital part in the advancement of medical research including:

- Providing new and good information on which types of drugs are more effective.

- Bringing new treatments such as medicines, vaccines and devices into the field.

- Testing the safety and efficacy of a new drug before it is brought to market and used in clinical practice.

- Giving the opportunity for more effective treatments to benefit millions of lives both now and in the future.

- Enhancing health, lengthening life, and reducing the burdens of illness and disability.

This all plays back to clinical research as it opens doors to advancing prevention, as well as providing treatments and cures for diseases and disabilities. Clinical trial volunteer participants are essential to this progress which further supports the need for the importance of research to be well-known amongst healthcare professionals, students and the general public.

Five Reasons Why Research is Critical

Research is vital for almost everyone irrespective of their career field. From doctors to lawyers to students to scientists, research is the key to better work.

- Increases quality of life

Research is the backbone of any major scientific or medical breakthrough. None of the advanced treatments or life-saving discoveries used to treat patients today would be available if it wasn’t for the detailed and intricate work carried out by scientists, doctors and healthcare professionals over the past decade.

This improves quality of life because it can help us find out important facts connected to the researched subject. For example, universities across the globe are now studying a wide variety of things from how technology can help breed healthier livestock, to how dance can provide long-term benefits to people living with Parkinson’s.

For both of these studies, quality of life is improved. Farmers can use technology to breed healthier livestock which in turn provides them with a better turnover, and people who suffer from Parkinson’s disease can find a way to reduce their symptoms and ease their stress.

Research is a catalyst for solving the world’s most pressing issues. Even though the complexity of these issues evolves over time, they always provide a glimmer of hope to improving lives and making processes simpler.

- Builds up credibility

People are willing to listen and trust someone with new information on one condition – it’s backed up. And that’s exactly where research comes in. Conducting studies on new and unfamiliar subjects, and achieving the desired or expected outcome, can help people accept the unknown.

However, this goes without saying that your research should be focused on the best sources. It is easy for people to poke holes in your findings if your studies have not been carried out correctly, or there is no reliable data to back them up.

This way once you have done completed your research, you can speak with confidence about your findings within your field of study.

- Drives progress forward

It is with thanks to scientific research that many diseases once thought incurable, now have treatments. For example, before the 1930s, anyone who contracted a bacterial infection had a high probability of death. There simply was no treatment for even the mildest of infections as, at the time, it was thought that nothing could kill bacteria in the gut.

When antibiotics were discovered and researched in 1928, it was considered one of the biggest breakthroughs in the medical field. This goes to show how much research drives progress forward, and how it is also responsible for the evolution of technology .

Today vaccines, diagnoses and treatments can all be simplified with the progression of medical research, making us question just what research can achieve in the future.

- Engages curiosity

The acts of searching for information and thinking critically serve as food for the brain, allowing our inherent creativity and logic to remain active. Aside from the fact that this curiosity plays such a huge part within research, it is also proven that exercising our minds can reduce anxiety and our chances of developing mental illnesses in the future.

Without our natural thirst and our constant need to ask ‘why?’ and ‘how?’ many important theories would not have been put forward and life-changing discoveries would not have been made. The best part is that the research process itself rewards this curiosity.

Research opens you up to different opinions and new ideas which can take a proposed question and turn into a real-life concept. It also builds discerning and analytical skills which are always beneficial in many career fields – not just scientific ones.

- Increases awareness

The main goal of any research study is to increase awareness, whether it’s contemplating new concepts with peers from work or attracting the attention of the general public surrounding a certain issue.

Around the globe, research is used to help raise awareness of issues like climate change, racial discrimination, and gender inequality. Without consistent and reliable studies to back up these issues, it would be hard to convenience people that there is a problem that needs to be solved in the first place.

The problem is that social media has become a place where fake news spreads like a wildfire, and with so many incorrect facts out there it can be hard to know who to trust. Assessing the integrity of the news source and checking for similar news on legitimate media outlets can help prove right from wrong.

This can pinpoint fake research articles and raises awareness of just how important fact-checking can be.

The Importance Of Research To Students

It is not a hidden fact that research can be mentally draining, which is why most students avoid it like the plague. But the matter of fact is that no matter which career path you choose to go down, research will inevitably be a part of it.

But why is research so important to students ? The truth is without research, any intellectual growth is pretty much impossible. It acts as a knowledge-building tool that can guide you up to the different levels of learning. Even if you are an expert in your field, there is always more to uncover, or if you are studying an entirely new topic, research can help you build a unique perspective about it.

For example, if you are looking into a topic for the first time, it might be confusing knowing where to begin. Most of the time you have an overwhelming amount of information to sort through whether that be reading through scientific journals online or getting through a pile of textbooks. Research helps to narrow down to the most important points you need so you are able to find what you need to succeed quickly and easily.

It can also open up great doors in the working world. Employers, especially those in the scientific and medical fields, are always looking for skilled people to hire. Undertaking research and completing studies within your academic phase can show just how multi-skilled you are and give you the resources to tackle any tasks given to you in the workplace.

The Importance Of Research Methodology

There are many different types of research that can be done, each one with its unique methodology and features that have been designed to use in specific settings.

When showing your research to others, they will want to be guaranteed that your proposed inquiry needs asking, and that your methodology is equipt to answer your inquiry and will convey the results you’re looking for.

That’s why it’s so important to choose the right methodology for your study. Knowing what the different types of research are and what each of them focuses on can allow you to plan your project to better utilise the most appropriate methodologies and techniques available. Here are some of the most common types:

- Theoretical Research: This attempts to answer a question based on the unknown. This could include studying phenomena or ideas whose conclusions may not have any immediate real-world application. Commonly used in physics and astronomy applications.

- Applied Research: Mainly for development purposes, this seeks to solve a practical problem that draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge. Commonly used in STEM and medical fields.

- Exploratory Research: Used to investigate a problem that is not clearly defined, this type of research can be used to establish cause-and-effect relationships. It can be applied in a wide range of fields from business to literature.

- Correlational Research: This identifies the relationship between two or more variables to see if and how they interact with each other. Very commonly used in psychological and statistical applications.

The Importance Of Qualitative Research

This type of research is most commonly used in scientific and social applications. It collects, compares and interprets information to specifically address the “how” and “why” research questions.

Qualitative research allows you to ask questions that cannot be easily put into numbers to understand human experience because you’re not limited by survey instruments with a fixed set of possible responses.

Information can be gathered in numerous ways including interviews, focus groups and ethnographic research which is then all reported in the language of the informant instead of statistical analyses.

This type of research is important because they do not usually require a hypothesis to be carried out. Instead, it is an open-ended research approach that can be adapted and changed while the study is ongoing. This enhances the quality of the data and insights generated and creates a much more unique set of data to analyse.

The Process Of Scientific Research

No matter the type of research completed, it will be shared and read by others. Whether this is with colleagues at work, peers at university, or whilst it’s being reviewed and repeated during secondary analysis.

A reliable procedure is necessary in order to obtain the best information which is why it’s important to have a plan. Here are the six basic steps that apply in any research process.

- Observation and asking questions: Seeing a phenomenon and asking yourself ‘How, What, When, Who, Which, Why, or Where?’. It is best that these questions are measurable and answerable through experimentation.

- Gathering information: Doing some background research to learn what is already known about the topic, and what you need to find out.

- Forming a hypothesis: Constructing a tentative statement to study.

- Testing the hypothesis: Conducting an experiment to test the accuracy of your statement. This is a way to gather data about your predictions and should be easy to repeat.

- Making conclusions: Analysing the data from the experiment(s) and drawing conclusions about whether they support or contradict your hypothesis.

- Reporting: Presenting your findings in a clear way to communicate with others. This could include making a video, writing a report or giving a presentation to illustrate your findings.

Although most scientists and researchers use this method, it may be tweaked between one study and another. Skipping or repeating steps is common within, however the core principles of the research process still apply.

By clearly explaining the steps and procedures used throughout the study, other researchers can then replicate the results. This is especially beneficial for peer reviews that try to replicate the results to ensure that the study is sound.

What Is The Importance Of Research In Everyday Life?

Conducting a research study and comparing it to how important it is in everyday life are two very different things.

Carrying out research allows you to gain a deeper understanding of science and medicine by developing research questions and letting your curiosity blossom. You can experience what it is like to work in a lab and learn about the whole reasoning behind the scientific process. But how does that impact everyday life?

Simply put, it allows us to disprove lies and support truths. This can help society to develop a confident attitude and not believe everything as easily, especially with the rise of fake news.

Research is the best and reliable way to understand and act on the complexities of various issues that we as humans are facing. From technology to healthcare to defence to climate change, carrying out studies is the only safe and reliable way to face our future.

Not only does research sharpen our brains, but also helps us to understand various issues of life in a much larger manner, always leaving us questioning everything and fuelling our need for answers.

Logan Bessant is a dedicated science educator and the founder of Science Resource Online, launched in 2020. With a background in science education and a passion for accessible learning, Logan has built a platform that offers free, high-quality educational resources to learners of all ages and backgrounds.

Related Articles:

- What is STEM education?

- How Stem Education Improves Student Learning

- What Are the Three Domains for the Roles of Technology for Teaching and Learning?

- Why Is FIDO2 Secure?

Featured Articles

Significance of a Study: Revisiting the “So What” Question

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 December 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- James Hiebert 6 ,

- Jinfa Cai 7 ,

- Stephen Hwang 7 ,

- Anne K Morris 6 &

- Charles Hohensee 6

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

19k Accesses

Every researcher wants their study to matter—to make a positive difference for their professional communities. To ensure your study matters, you can formulate clear hypotheses and choose methods that will test them well, as described in Chaps. 1, 2, 3 and 4. You can go further, however, by considering some of the terms commonly used to describe the importance of studies, terms like significance, contributions, and implications. As you clarify for yourself the meanings of these terms, you learn that whether your study matters depends on how convincingly you can argue for its importance. Perhaps most surprising is that convincing others of its importance rests with the case you make before the data are ever gathered. The importance of your hypotheses should be apparent before you test them. Are your predictions about things the profession cares about? Can you make them with a striking degree of precision? Are the rationales that support them compelling? You are answering the “So what?” question as you formulate hypotheses and design tests of them. This means you can control the answer. You do not need to cross your fingers and hope as you collect data.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Part I. Setting the Groundwork

One of the most common questions asked of researchers is “So what?” What difference does your study make? Why are the findings important? The “so what” question is one of the most basic questions, often perceived by novice researchers as the most difficult question to answer. Indeed, addressing the “so what” question continues to challenge even experienced researchers. It is not always easy to articulate a convincing argument for the importance of your work. It can be especially difficult to describe its importance without falling into the trap of making claims that reach beyond the data.

That this issue is a challenge for researchers is illustrated by our analysis of reviewer comments for JRME . About one-third of the reviews for manuscripts that were ultimately rejected included concerns about the importance of the study. Said another way, reviewers felt the “So what?” question had not been answered. To paraphrase one journal reviewer, “The manuscript left me unsure of what the contribution of this work to the field’s knowledge is, and therefore I doubt its significance.” We expect this is a frequent concern of reviewers for all research journals.

Our goal in this chapter is to help you navigate the pressing demands of journal reviewers, editors, and readers for demonstrating the importance of your work while staying within the bounds of acceptable claims based on your results. We will begin by reviewing what we have said about these issues in previous chapters. We will then clarify one of the confusing aspects of developing appropriate arguments—the absence of consensus definitions of key terms such as significance, contributions, and implications. Based on the definitions we propose, we will examine the critical role of alignment for realizing the potential significance of your study. Because the importance of your study is communicated through your evolving research paper, we will fold suggestions for writing your paper into the discussion of creating and executing your study.

We laid the groundwork in Chap. 1 for what we consider to be important research in education:

In our view, the ultimate goal of education is to offer all students the best possible learning opportunities. So, we believe the ultimate purpose of scientific inquiry in education is to support the improvement of learning opportunities for all students…. If there is no way to imagine a connection to improving learning opportunities for students, even a distant connection, we recommend you reconsider whether it is an important hypothesis within the education community.

Of course, you might prefer another “ultimate purpose” for research in education. That’s fine. The critical point is that the argument for the importance of the hypotheses you are testing should be connected to the value of a long-term goal you can describe. As long as most of the educational community agrees with this goal, and you can show how testing your hypotheses will move the field forward to achieving this goal, you will have developed a convincing argument for the importance of your work.

In Chap. 2 , we argued the importance of your hypotheses can and should be established before you collect data. Your theoretical framework should carry the weight of your argument because it should describe how your hypotheses will extend what is already known. Your methods should then show that you will test your hypotheses in an appropriate way—in a way that will allow you to detect how the results did, and did not, confirm the hypotheses. This will, in turn, allow you to formulate revised hypotheses. We described establishing the importance of your study by saying, “The importance can come from the fact that, based on the results, you will be able to offer revised hypotheses that help the field better understand an issue relevant for improving all students’ learning opportunities.”

The ideas from Chaps. 1 , 2 , and 3 go a long way toward setting the parameters for what counts as an important study and how its importance can be determined. Chapter 4 focused on ensuring that the importance of a study can be realized. The next section fills in the details by proposing definitions for the most common terms used to claim importance: significance, contributions, and implications.

You might notice that we do not have a chapter dedicated to discussing the presentation of the findings—that is, a “results” chapter. We do not mean to imply that presenting results is trivial. However, we believe that if you follow our recommendations for writing your evolving research paper, presenting the results will be quite straightforward. The key is to present your results so they can be most easily compared with your predictions. This means, among other things, organizing your presentation of results according to your earlier presentation of hypotheses.

Part II. Clarifying Importance by Revisiting the Definitions of Key Terms

What does it mean to say your findings are significant? Statistical significance is clear. There are widely accepted standards for determining the statistical significance of findings. But what about educational significance? Is this the same as claiming that your study makes an important contribution? Or, that your study has important implications? Different researchers might answer these questions in different ways. When key terms like these are overused, their definitions gradually broaden or shift, and they can lose their meaning. That is unfortunate, because it creates confusion about how to develop claims for the importance of a study.

By clarifying the definitions, we hope to clarify what is required to claim that a study is significant , that it makes a contribution , and that it has important implications . Not everyone defines the terms as we do. Our definitions are probably a bit narrower or more targeted than those you may encounter elsewhere. Depending on where you want to publish your study, you may want to adapt your use of these terms to match more closely the expectations of a particular journal. But the way we define and address these terms is not antithetical to common uses. And we believe ridding the terms of unnecessary overlap allows us to discriminate among different key concepts with respect to claims for the importance of research studies. It is not necessary to define the terms exactly as we have, but it is critical that the ideas embedded in our definitions be distinguished and that all of them be taken into account when examining the importance of a study.

We will use the following definitions:

Significance: The importance of the problem, questions, and/or hypotheses for improving the learning opportunities for all students (you can substitute a different long-term goal if its value is widely shared). Significance can be determined before data are gathered. Significance is an attribute of the research problem , not the research findings .

Contributions : The value of the findings for revising the hypotheses, making clear what has been learned, what is now better understood.

Implications : Deductions about what can be concluded from the findings that are not already included in “contributions.” The most common deductions in educational research are for improving educational practice. Deductions for research practice that are not already defined as contributions are often suggestions about research methods that are especially useful or methods to avoid.

Significance

The significance of a study is built by formulating research questions and hypotheses you connect through a careful argument to a long-term goal of widely shared value (e.g., improving learning opportunities for all students). Significance applies both to the domain in which your study is located and to your individual study. The significance of the domain is established by choosing a goal of widely shared value and then identifying a domain you can show is connected to achieving the goal. For example, if the goal to which your study contributes is improving the learning opportunities for all students, your study might aim to understand more fully how things work in a domain such as teaching for conceptual understanding, or preparing teachers to attend to all students, or designing curricula to support all learners, or connecting learning opportunities to particular learning outcomes.

The significance of your individual study is something you build ; it is not predetermined or self-evident. Significance of a study is established by making a case for it, not by simply choosing hypotheses everyone already thinks are important. Although you might believe the significance of your study is obvious, readers will need to be convinced.

Significance is something you develop in your evolving research paper. The theoretical framework you present connects your study to what has been investigated previously. Your argument for significance of the domain comes from the significance of the line of research of which your study is a part. The significance of your study is developed by showing, through the presentation of your framework, how your study advances this line of research. This means the lion’s share of your answer to the “So what?” question will be developed as part of your theoretical framework.

Although defining significance as located in your paper prior to presenting results is not a definition universally shared among educational researchers, it is becoming an increasingly common view. In fact, there is movement toward evaluating the significance of a study based only on the first sections of a research paper—the sections prior to the results (Makel et al., 2021 ).

In addition to addressing the “So what?” question, your theoretical framework can address another common concern often voiced by readers: “What is so interesting? I could have predicted those results.” Predictions do not need to be surprising to be interesting and significant. The significance comes from the rationales that show how the predictions extend what is currently known. It is irrelevant how many researchers could have made the predictions. What makes a study significant is that the theoretical framework and the predictions make clear how the study will increase the field’s understanding toward achieving a goal of shared value.

An important consequence of interpreting significance as a carefully developed argument for the importance of your research study within a larger domain is that it reveals the advantage of conducting a series of connected studies rather than single, disconnected studies. Building the significance of a research study requires time and effort. Once you have established significance for a particular study, you can build on this same argument for related studies. This saves time, allows you to continue to refine your argument across studies, and increases the likelihood your studies will contribute to the field.

Contributions

As we have noted, in fields as complicated as education, it is unlikely that your predictions will be entirely accurate. If the problem you are investigating is significant, the hypotheses will be formulated in such a way that they extend a line of research to understand more deeply phenomena related to students’ learning opportunities or another goal of shared value. Often, this means investigating the conditions under which phenomena occur. This gets complicated very quickly, so the data you gather will likely differ from your predictions in a variety of ways. The contributions your study makes will depend on how you interpret these results in light of the original hypotheses.

Contributions Emerge from Revisions to your Hypotheses

We view interpreting results as a process of comparing the data with the predictions and then examining the way in which hypotheses should be revised to more fully account for the results. Revising will almost always be warranted because, as we noted, predictions are unlikely to be entirely accurate. For example, if researchers expect Outcome A to occur under specified conditions but find that it does not occur to the extent predicted or actually does occur but without all the conditions, they must ask what changes to the hypotheses are needed to predict more accurately the conditions under which Outcome A occurred. Are there, for example, essential conditions that were not anticipated and that should be included in the revised hypotheses?

Consider an example from a recently published study (Wang et al., 2021 ). A team of researchers investigated the following research question: “How are students’ perceptions of their parents’ expectations related to students’ mathematics-related beliefs and their perceived mathematics achievement?” The researchers predicted that students’ perceptions of their parents’ expectations would be highly related to students’ mathematics-related beliefs and their perceived mathematics achievement. The rationale was based largely on prior research that had consistently found parents’ general educational expectations to be highly correlated with students’ achievement.

The findings showed that Chinese high school students’ perceptions of their parents’ educational expectations were positively related to these students’ mathematics-related beliefs. In other words, students who believed their parents expected them to attain higher levels of education had more desirable mathematics-related beliefs.

However, students’ perceptions of their parents’ expectations about mathematics achievement were not related to students’ mathematics-related beliefs in the same way as the more general parental educational expectations. Students who reported that their parents had no specific expectations possessed more desirable mathematics-related beliefs than all other subgroups. In addition, these students tended to perceive their mathematics achievement rank in their class to be higher on average than students who reported that their parents expressed some level of expectation for mathematics achievement.

Because this finding was not predicted, the researchers revised the original hypothesis. Their new prediction was that students who believe their parents have no specific mathematics achievement expectations possess more positive mathematics-related beliefs and higher perceived mathematics achievement than students who believe their parents do have specific expectations. They developed a revised rationale that drew on research on parental pressure and mathematics anxiety, positing that parents’ specific mathematics achievement expectations might increase their children’s sense of pressure and anxiety, thus fostering less positive mathematics-related beliefs. The team then conducted a follow-up study. Their findings aligned more closely with the new predictions and affirmed the better explanatory power of the revised rationale. The contributions of the study are found in this increased explanatory power—in the new understandings of this phenomenon contained in the revisions to the rationale.

Interpreting findings in order to revise hypotheses is not a straightforward task. Usually, the rationales blend multiple constructs or variables and predict multiple outcomes, with different outcomes connected to different research questions and addressed by different sets of data. Nevertheless, the contributions of your study depend on specifying the differences between your original hypotheses and your revised hypotheses. What can you explain now that you could not explain before?

We believe that revising hypotheses is an optimal response to any question of contributions because a researcher’s initial hypotheses plus the revisions suggested by the data are the most productive way to tie a study into the larger chain of research of which it is a part. Revised hypotheses represent growth in knowledge. Building on other researchers’ revised hypotheses and revising them further by more explicitly and precisely describing the conditions that are expected to influence the outcomes in the next study accumulates knowledge in a form that can be recorded, shared, built upon, and improved.

The significance of your study is presented in the opening sections of your evolving research paper whereas the contributions are presented in the final section, after the results. In fact, the central focus in this “Discussion” section should be a specification of the contributions (note, though, that this guidance may not fully align with the requirements of some journals).

Contributions Answer the Question of Generalizability

A common and often contentious, confusing issue that can befuddle novice and experienced researchers alike is the generalizability of results. All researchers prefer to believe the results they report apply to more than the sample of participants in their study. How important would a study be if the results applied only to, say, two fourth-grade classrooms in one school, or to the exact same tasks used as measures? How do you decide to which larger population (of students or tasks) your results could generalize? How can you state your claims so they are precisely those justified by the data?

To illustrate the challenge faced by researchers in answering these questions, we return to the JRME reviewers. We found that 30% of the reviews expressed concerns about the match between the results and the claims. For manuscripts that ultimately received a decision of Reject, the majority of reviewers said the authors had overreached—the claims were not supported by the data. In other words, authors generalized their claims beyond those that could be justified.

The Connection Between Contributions and Generalizability

In our view, claims about contributions can be examined productively alongside considerations of generalizability. To make the case for this view, we need to back up a bit. Recall that the purpose of research is to understand a phenomenon. To understand a phenomenon, you need to determine the conditions under which it occurs. Consequently, productive hypotheses specify the conditions under which the predictions hold and explain why and how these conditions make a difference. And the conditions set the parameters on generalizability. They identify when, where, and for whom the effect or situation will occur. So, hypotheses describe the extent of expected generalizability, and revised hypotheses that contain the contributions recalibrate generalizability and offer new predictions within these parameters.

An Example That Illustrates the Connection

In Chap. 4 , we introduced an example with a research question asking whether second graders improve their understanding of place value after a specially designed instructional intervention. We suggested asking a few second and third graders to complete your tasks to see if they generated the expected variation in performance. Suppose you completed this pilot study and now have satisfactory tasks. What conditions might influence the effect of the intervention? After careful study, you developed rationales that supported three conditions: the entry level of students’ understanding, the way in which the intervention is implemented, and the classroom norms that set expectations for students’ participation.

Suppose your original hypotheses predicted the desired effect of the intervention only if the students possessed an understanding of several concepts on which place value is built, only if the intervention was implemented with fidelity to the detailed instructional guidelines, and only if classroom norms encouraged students to participate in small-group work and whole-class discussions. Your claims of generalizability will apply to second-grade settings with these characteristics.

Now suppose you designed the study so the intervention occurred in five second-grade classrooms that agreed to participate. The pre-intervention assessment showed all students with the minimal level of entry understanding. The same well-trained teacher was employed to teach the intervention in all five classrooms, none of which included her own students. And you learned from prior observations and reports of the classroom teachers that three of the classrooms operated with the desired classroom norms, but two did not. Because of these conditions, your study is now designed to test one of your hypotheses—the desired effect will occur only if classroom norms encouraged students to participate in small-group work and whole-class discussions. This is the only condition that will vary; the other two (prior level of understanding and fidelity of implementation) are the same across classrooms so you will not learn how these affect the results.

Suppose the classrooms performed equally well on the post-intervention assessments. You expected lower performance in the two classrooms with less student participation, so you need to revise your hypotheses. The challenge is to explain the higher-than-expected performance of these students. Because you were interested in understanding the effects of this condition, you observed several lessons in all the classrooms during the intervention. You can now use this information to explain why the intervention worked equally well in classrooms with different norms.

Your revised hypothesis captures this part of your study’s contribution. You can now say more about the ways in which the intervention can help students improve their understanding of place value because you have different information about the role of classroom norms. This, in turn, allows you to specify more precisely the nature and extent of the generalizability of your findings. You now can generalize your findings to classrooms with different norms. However, because you did not learn more about the impact of students’ entry level understandings or of different kinds of implementation, the generalizability along these dimensions remains as limited as before.

This example is simplified. In many studies, the findings will be more complicated, and more conditions will likely be identified, some of which were anticipated and some of which emerged while conducting the study and analyzing the data. Nevertheless, the point is that generalizability should be tied to the conditions that are expected to affect the results. Further, unanticipated conditions almost always appear, so generalizations should be conservative and made with caution and humility. They are likely to change after testing the new predictions.

Contributions Are Assured When Hypotheses Are Significant and Methods Are Appropriate and Aligned

We have argued that the contributions of your study are produced by the revised hypotheses you can formulate based on your results. Will these revisions always represent contributions to the field? What if the revisions are minor? What if your results do not inform revisions to your hypotheses?

We will answer these questions briefly now and then develop them further in Part IV of this chapter. The answer to the primary question is “yes,” your revisions will always be a contribution to the field if (1) your hypotheses are significant and (2) you crafted appropriate methods to test the hypotheses. This is true even if your revisions are minor or if your data are not as informative as you expected. However, this is true only if you meet the two conditions in the earlier sentence. The first condition (significant hypotheses) can be satisfied by following the suggestions in the earlier section on significance. The second condition (appropriate methods) is addressed further in Part III in this chapter.

Implications

Before examining the role of methods in connecting significance with important contributions, we elaborate briefly our definition of “implications.” We reserve implications for the conclusions you can logically deduce from your findings that are not already presented as contributions. This means that, like contributions, implications are presented in the Discussion section of your research paper.

Many educational researchers present two types of implications: implications for future research and implications for practice. Although we are aware of this common usage, we believe our definition of “contributions” cover these implications. Clarifying why we call these “contributions” will explain why we largely reserve the word “implications” for recommendations regarding methods.

Implications for Future Research

Implications for future research often include (1) recommendations for empirical studies that would extend the findings of this study, (2) inferences about the usefulness of theoretical constructs, and (3) conclusions about the advisability of using particular kinds of methods. Given our earlier definitions, we prefer to label the first two types of implications as contributions.

Consider recommendations for empirical studies. After analyzing the data and presenting the results, we have suggested you compare the results with those predicted, revise the rationales for the original predictions to account for the results, and make new predictions based on the revised rationales. It is precisely these new predictions that can form the basis for recommending future research. Testing these new predictions is what would most productively extend this line of research. It can sometimes sound as if researchers are recommending future studies based on hunches about what research might yield useful findings. But researchers can do better than this. It would be more productive to base recommendations on a careful analysis of how the predictions of the original study could be sharpened and improved.

Now consider inferences about the usefulness of theoretical constructs. Our argument for labeling these inferences as contributions is similar. Rationales for predictions are where the relevant theoretical constructs are located. Revisions to these rationales based on the differences between the results and the predictions reveal the theoretical constructs that were affirmed to support accurate predictions and those that must be revised. In our view, usefulness is determined through this revision process.

Implications that do not come under our meaning of contributions are in the third type of implications, namely the appropriateness of methods for generating rich contributions. These kinds of implications are produced by your evaluation of your methods: research design, sampling procedures, tasks, data collection procedures, and data analyses. Although not always included in the discussion of findings, we believe it would be helpful for researchers to identify particular methods that were useful for conducting their study and those that should be modified or avoided. We believe these are appropriately called implications.

Implications for Practice

If the purpose of research is to better understand how to improve learning opportunities for all students, then it is appropriate to consider whether implications for improving educational practice can be drawn from the results of a study. How are these implications formulated? This is an important question because, in our view, these claims often come across as an afterthought, “Oh, I need to add some implications for practice.” But here is the sobering reality facing researchers: By any measure, the history of educational research shows that identifying these implications has had little positive effect on practice.

Perhaps the most challenging task for researchers who attempt to draw implications for practice is to interpret their findings for appropriate settings. A researcher who studied the instructional intervention for second graders on place value and found that average performance in the intervention classrooms improved more than in the textbook classrooms might be tempted to draw implications for practice. What should the researcher say? That second-grade teachers should adopt the intervention? Such an implication would be an overreach because, as we noted earlier, the findings cannot be generalized to all second-grade classrooms. Moreover, an improvement in average performance does not mean the intervention was better for all students.

The challenge is to identify the conditions under which the intervention would improve the learning opportunities for all students. Some of these conditions will be identified as the theoretical framework is built because the predictions need to account for these conditions. But some will be unforeseen, and some that are identified will not be informed by the findings. Recall that, in the study described earlier, a condition of entry level of understanding was hypothesized but the design of the study did not allow the researcher to draw any conclusions about its effect.

What can researchers say about implications for practice given the complexities involved in generalizing findings to other settings? We offer two recommendations. First, because it is difficult to specify all the conditions under which a phenomenon occurs, it is rarely appropriate to prescribe an educational practice. Researchers cannot anticipate the conditions under which individual teachers operate, conditions that often require adaptation of a suggested practice rather than implementation of a practice as prescribed.

Our second recommendation comes from returning to the purpose for educational research—to understand more fully how to improve learning opportunities for all students (or to achieve another goal of widely shared value). As we have described, understanding comes primarily from building and reevaluating rationales for your predictions. If you reach a new understanding related to improving learning opportunities, an understanding that could have practical implications, we recommend you share this understanding as an implication for practice.

For example, suppose the researcher who found better average performance of second graders after the intervention on place value had also studied several conditions under which performance improved. And suppose the researcher found that most students who did not improve their performance misunderstood a concept that appeared early in the intervention (e.g., the multiplicative relationship between positional values of a numeral). An implication for practice the researcher might share would be to describe the potential importance of understanding this concept early in the sequence of activities if teachers try out this intervention.

If you use our definitions, these implications for practice would be presented as contributions because they emerge directly from reevaluating and revising your rationales. We believe it is appropriate to use “Contributions” as the heading for this section in the Discussion section of your research paper. However, if editors prefer “Implications” we recommend following their suggestion.

We want to be clear that the terms you use for the different ways your study is important is not critical. We chose to define the terms significance, contributions, and implications in very specific and not universally shared ways to distinguish all the meanings of importance you should consider. Some of these can be established through your theoretical framework, some by the revisions of your hypotheses, and some by reflecting on the value of particular methods. The important thing, from our point of view, is that the ideas we defined for each of these terms are distinguished and recognized as specific ways of determining the importance of your study.

Part III. The Role of Methods in Determining Contributions

We have argued that every part of the study (and of the evolving research paper) should be aligned. All parts should be connected through a coherent chain of reasoning. In this chapter, we argue that the chain of reasoning is not complete until the methods are presented and the results are interpreted and discussed. The methods of the study create a bridge that connects the introductory material (research questions, theoretical framework, literature review, hypotheses) with the results and interpretations.

The role that methods play in scientific inquiry is to ensure that your hypotheses will be tested appropriately so the significance of your study will yield its potential contributions. To do this, the methods must do more than follow the standard guidelines and be technically correct (see Chap. 4 ). They must also fit with the surrounding parts of the study. We call this coherence.

Coherence Across the Phases of Scientific Inquiry

Coherence means the parts of a whole are fully aligned. When doing scientific inquiry, the early parts or phases should motivate the later phases. The methods you use should be motivated or explained by the earlier phases (e.g., research questions, theoretical framework, hypotheses). Your methods, in turn, should produce results that can be interpreted by comparing them with your predictions. Methods are aligned with earlier phases when you can use the rationales contained in your hypotheses to decide what kinds of data are needed to test your predictions, how best to gather these kinds of data, and what analyses should be performed (see Chap. 4 and Cai et al., 2019a ).

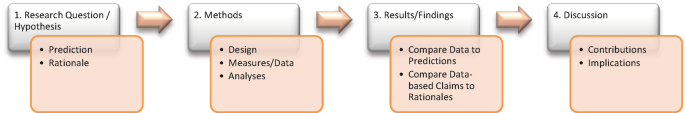

For a visual representation of this coherence, see Fig. 5.1 . Each box identifies an aspect of scientific inquiry. Hypotheses (shown in Box 1) include the rationales and predictions. Because the rationales encompass the theoretical framework and the literature review, Box 1 establishes the significance of the study. Box 2 represents the methods, which we defined in Chap. 4 as the entire set of procedures you will use, including the basic design, measures for collecting data, and analytic approaches. In Fig. 5.1 , the hypothesis in Box 1 points you to the methods you will use. That is, you will choose methods that provide data for analyses that will generate results or findings (Box 3) that allow you to make comparisons against your predictions. Based on those comparisons, you will revise your hypotheses and derive the contributions and implications of your study (Box 4).

The Chain of Coherence That Runs Through All Parts of a Research Study

We intend Fig. 5.1 to carry several messages. One is that coherence of a study and the associated research paper require all aspects of the study to flow from one into the other. Each set of prior entries must motivate and justify the next one. For example, the data and analyses you intend to gather and use in Box 2 (Methods) must be those that are motivated and explained by the research question and hypothesis (prediction and rationale) in Box 1.

A second message in the figure is that coherence includes Box 4, “Discussion.” Aligned with the first three boxes, the fourth box flows from these boxes but is also constrained by them. The contributions and implications authors describe in the Discussion section of the paper cannot go beyond what is allowed by the original hypotheses and the revisions to these hypotheses indicated by the findings.

|

|

Methods Enable Significance to Yield Contributions

We begin this section by identifying a third message conveyed in Fig. 5.1 . The methods of the study, represented by Box 2, provide a bridge that connects the significance of the study (Box 1) with the contributions of the study (Box 4). The results (Box 3) indicate the nature of the contributions by determining the revisions to the original hypotheses.

In our view, the connecting role played by the methods is often underappreciated. Crafting appropriate methods aligned with the significance of the study, on one hand, and the interpretations, on the other, can determine whether a study is judged to make a contribution.

If the hypotheses are established as significant, and if appropriate methods are used to test the predictions, the study will make important contributions even if the data are not statistically significant. We can say this another way. When researchers establish the significance of the hypotheses (i.e., convince readers they are of interest to the field) and use methods that provide a sound test of these hypotheses, the data they present will be of interest regardless of how they turn out. This is why Makel et al. ( 2021 ) endorse a review process for publication that emphasizes the significance of the study as presented in the first sections of a research paper.

Treating the methods as connecting the introductory arguments to the interpretations of data prevent researchers from making a common mistake: When writing the research paper, some researchers lose track of the research questions and/or the predictions. In other words, results are presented but are not interpreted as answers to the research questions or compared with the predictions. It is as if the introductory material of the paper begins one story, and the interpretations of results ends a different story. Lack of alignment makes it impossible to tell one coherent story.

A final point is that the alignment of a study cannot be evaluated and appreciated if the methods are not fully described. Methods must be described clearly and completely in the research paper so readers can see how they flow from the earlier phases of the study and how they yield the data presented. We suggested in Chap. 4 a rule of thumb for deciding whether the methods have been fully described: “Readers should be able to replicate the study if they wish.”

Part IV. Special Considerations that Affect a Study’s Contributions

We conclude Chap. 5 by addressing two additional issues that can affect how researchers interpret the results and make claims about the contributions of a study. Usually, researchers deal with these issues in the Discussion section of their research paper, but we believe it is useful to consider them as you plan and conduct your study. The issues can be posed as questions: How should I treat the limitations of my study? How should I deal with findings that are completely unexpected?

Limitations of a Study

We can identify two kinds of limitations: (1) limitations that constrain your ability to interpret your results because of unfortunate choices you made, and (2) limitations that constrain your ability to generalize your results because of missing variables you could not fit into the scope of your study or did not anticipate. We recommend different ways of dealing with these.

Limitations Due to Unfortunate Choices