An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Biological, Psychological, and Social Determinants of Depression: A Review of Recent Literature

Olivia remes.

1 Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0FS, UK

João Francisco Mendes

2 NOVA Medical School, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 1099-085 Lisbon, Portugal; ku.ca.mac@94cfj

Peter Templeton

3 IfM Engage Limited, Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0FS, UK; ku.ca.mac@32twp

4 The William Templeton Foundation for Young People’s Mental Health (YPMH), Cambridge CB2 0AH, UK

Associated Data

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability, and, if left unmanaged, it can increase the risk for suicide. The evidence base on the determinants of depression is fragmented, which makes the interpretation of the results across studies difficult. The objective of this study is to conduct a thorough synthesis of the literature assessing the biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression in order to piece together the puzzle of the key factors that are related to this condition. Titles and abstracts published between 2017 and 2020 were identified in PubMed, as well as Medline, Scopus, and PsycInfo. Key words relating to biological, social, and psychological determinants as well as depression were applied to the databases, and the screening and data charting of the documents took place. We included 470 documents in this literature review. The findings showed that there are a plethora of risk and protective factors (relating to biological, psychological, and social determinants) that are related to depression; these determinants are interlinked and influence depression outcomes through a web of causation. In this paper, we describe and present the vast, fragmented, and complex literature related to this topic. This review may be used to guide practice, public health efforts, policy, and research related to mental health and, specifically, depression.

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most common mental health issues, with an estimated prevalence of 5% among adults [ 1 , 2 ]. Symptoms may include anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, concentration and sleep difficulties, and suicidal ideation. According to the World Health Organization, depression is a leading cause of disability; research shows that it is a burdensome condition with a negative impact on educational trajectories, work performance, and other areas of life [ 1 , 3 ]. Depression can start early in the lifecourse and, if it remains unmanaged, may increase the risk for substance abuse, chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ].

Treatment for depression exists, such as pharmacotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, and other modalities. A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of patients shows that 56–60% of people respond well to active treatment with antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants) [ 9 ]. However, pharmacotherapy may be associated with problems, such as side-effects, relapse issues, a potential duration of weeks until the medication starts working, and possible limited efficacy in mild cases [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Psychotherapy is also available, but access barriers can make it difficult for a number of people to get the necessary help.

Studies on depression have increased significantly over the past few decades. However, the literature remains fragmented and the interpretation of heterogeneous findings across studies and between fields is difficult. The cross-pollination of ideas between disciplines, such as genetics, neurology, immunology, and psychology, is limited. Reviews on the determinants of depression have been conducted, but they either focus exclusively on a particular set of determinants (ex. genetic risk factors [ 15 ]) or population sub-group (ex. children and adolescents [ 16 ]) or focus on characteristics measured predominantly at the individual level (ex. focus on social support, history of depression [ 17 ]) without taking the wider context (ex. area-level variables) into account. An integrated approach paying attention to key determinants from the biological, psychological, and social spheres, as well as key themes, such as the lifecourse perspective, enables clinicians and public health authorities to develop tailored, person-centred approaches.

The primary aim of this literature review: to address the aforementioned challenges, we have synthesized recent research on the biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression and we have reviewed research from fields including genetics, immunology, neurology, psychology, public health, and epidemiology, among others.

The subsidiary aim: we have paid special attention to important themes, including the lifecourse perspective and interactions between determinants, to guide further efforts by public health and medical professionals.

This literature review can be used as an evidence base by those in public health and the clinical setting and can be used to inform targeted interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a review of the literature on the biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression in the last 4 years. We decided to focus on these determinants after discussions with academics (from the Manchester Metropolitan University, University of Cardiff, University of Colorado, Boulder, University of Cork, University of Leuven, University of Texas), charity representatives, and people with lived experience at workshops held by the University of Cambridge in 2020. In several aspects, we attempted to conduct this review according to PRISMA guidelines [ 18 ].

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are the following:

- - We included documents, such as primary studies, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reports, and commentaries on the determinants of depression. The determinants refer to variables that appear to be linked to the development of depression, such as physiological factors (e.g., the nervous system, genetics), but also factors that are further away or more distal to the condition. Determinants may be risk or protective factors, and individual- or wider-area-level variables.

- - We focused on major depressive disorder, treatment-resistant depression, dysthymia, depressive symptoms, poststroke depression, perinatal depression, as well as depressive-like behaviour (common in animal studies), among others.

- - We included papers regardless of the measurement methods of depression.

- - We included papers that focused on human and/or rodent research.

- - This review focused on articles written in the English language.

- - Documents published between 2017–2020 were captured to provide an understanding of the latest research on this topic.

- - Studies that assessed depression as a comorbidity or secondary to another disorder.

- - Studies that did not focus on rodent and/or human research.

- - Studies that focused on the treatment of depression. We made this decision, because this is an in-depth topic that would warrant a separate stand-alone review.

- Next, we searched PubMed (2017–2020) using keywords related to depression and determinants. Appendix A contains the search strategy used. We also conducted focused searches in Medline, Scopus, and PsycInfo (2017–2020).

- Once the documents were identified through the databases, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the titles and abstracts. Screening of documents was conducted by O.R., and a subsample was screened by J.M.; any discrepancies were resolved through a communication process.

- The full texts of documents were retrieved, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were again applied. A subsample of documents underwent double screening by two authors (O.R., J.M.); again, any discrepancies were resolved through communication.

- a. A data charting form was created to capture the data elements of interest, including the authors, titles, determinants (biological, psychological, social), and the type of depression assessed by the research (e.g., major depression, depressive symptoms, depressive behaviour).

- b. The data charting form was piloted on a subset of documents, and refinements to it were made. The data charting form was created with the data elements described above and tested in 20 studies to determine whether refinements in the wording or language were needed.

- c. Data charting was conducted on the documents.

- d. Narrative analysis was conducted on the data charting table to identify key themes. When a particular finding was noted more than once, it was logged as a potential theme, with a review of these notes yielding key themes that appeared on multiple occasions. When key themes were identified, one researcher (O.R.) reviewed each document pertaining to that theme and derived concepts (key determinants and related outcomes). This process (a subsample) was verified by a second author (J.M.), and the two authors resolved any discrepancies through communication. Key themes were also checked as to whether they were of major significance to public mental health and at the forefront of public health discourse according to consultations we held with stakeholders from the Manchester Metropolitan University, University of Cardiff, University of Colorado, Boulder, University of Cork, University of Leuven, University of Texas, charity representatives, and people with lived experience at workshops held by the University of Cambridge in 2020.

We condensed the extensive information gleaned through our review into short summaries (with key points boxes for ease of understanding and interpretation of the data).

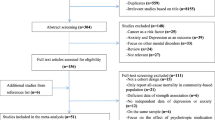

Through the searches, 6335 documents, such as primary studies, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reports, and commentaries, were identified. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 470 papers were included in this review ( Supplementary Table S1 ). We focused on aspects related to biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression (examples of determinants and related outcomes are provided under each of the following sections.

3.1. Biological Factors

The following aspects will be discussed in this section: physical health conditions; then specific biological factors, including genetics; the microbiome; inflammatory factors; stress and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, and the kynurenine pathway. Finally, aspects related to cognition will also be discussed in the context of depression.

3.1.1. Physical Health Conditions

Studies on physical health conditions—key points:

- The presence of a physical health condition can increase the risk for depression

- Psychological evaluation in physically sick populations is needed

- There is large heterogeneity in study design and measurement; this makes the comparison of findings between and across studies difficult

A number of studies examined the links between the outcome of depression and physical health-related factors, such as bladder outlet obstruction, cerebral atrophy, cataract, stroke, epilepsy, body mass index and obesity, diabetes, urinary tract infection, forms of cancer, inflammatory bowel disorder, glaucoma, acne, urea accumulation, cerebral small vessel disease, traumatic brain injury, and disability in multiple sclerosis [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 ]. For example, bladder outlet obstruction has been linked to inflammation and depressive behaviour in rodent research [ 24 ]. The presence of head and neck cancer also seemed to be related to an increased risk for depressive disorder [ 45 ]. Gestational diabetes mellitus has been linked to depressive symptoms in the postpartum period (but no association has been found with depression in the third pregnancy trimester) [ 50 ], and a plethora of other such examples of relationships between depression and physical conditions exist. As such, the assessment of psychopathology and the provision of support are necessary in individuals of ill health [ 45 ]. Despite the large evidence base on physical health-related factors, differences in study methodology and design, the lack of standardization when it comes to the measurement of various physical health conditions and depression, and heterogeneity in the study populations makes it difficult to compare studies [ 50 ].

The next subsections discuss specific biological factors, including genetics; the microbiome; inflammatory factors; stress and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, and the kynurenine pathway; and aspects related to cognition.

3.1.2. Genetics

Studies on genetics—key points:

There were associations between genetic factors and depression; for example:

- The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays an important role in depression

- Links exist between major histocompatibility complex region genes, as well as various gene polymorphisms and depression

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of genes involved in the tryptophan catabolites pathway are of interest in relation to depression

A number of genetic-related factors, genomic regions, polymorphisms, and other related aspects have been examined with respect to depression [ 61 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 ]. The influence of BDNF in relation to depression has been amply studied [ 117 , 118 , 141 , 142 , 143 ]. Research has shown associations between depression and BDNF (as well as candidate SNPs of the BDNF gene, polymorphisms of the BDNF gene, and the interaction of these polymorphisms with other determinants, such as stress) [ 129 , 144 , 145 ]. Specific findings have been reported: for example, a study reported a link between the BDNF rs6265 allele (A) and major depressive disorder [ 117 ].

Other research focused on major histocompatibility complex region genes, endocannabinoid receptor gene polymorphisms, as well as tissue-specific genes and gene co-expression networks and their links to depression [ 99 , 110 , 112 ]. The SNPs of genes involved in the tryptophan catabolites pathway have also been of interest when studying the pathogenesis of depression.

The results from genetics studies are compelling; however, the findings remain mixed. One study indicated no support for depression candidate gene findings [ 122 ]. Another study found no association between specific polymorphisms and major depressive disorder [ 132 ]. As such, further research using larger samples is needed to corroborate the statistically significant associations reported in the literature.

3.1.3. Microbiome

Studies on the microbiome—key points:

- The gut bacteria and the brain communicate via both direct and indirect pathways called the gut-microbiota-brain axis (the bidirectional communication networks between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract; this axis plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis).

- A disordered microbiome can lead to inflammation, which can then lead to depression

- There are possible links between the gut microbiome, host liver metabolism, brain inflammation, and depression

The common themes of this review have focused on the microbiome/microbiota or gut metabolome [ 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 , 160 , 161 ], the microbiota-gut-brain axis, and related factors [ 152 , 162 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 , 167 ]. When there is an imbalance in the intestinal bacteria, this can interfere with emotional regulation and contribute to harmful inflammatory processes and mood disorders [ 148 , 151 , 153 , 155 , 157 ]. Rodent research has shown that there may be a bidirectional association between the gut microbiota and depression: a disordered gut microbiota can play a role in the onset of this mental health problem, but, at the same time, the existence of stress and depression may also lead to a lower level of richness and diversity in the microbiome [ 158 ].

Research has also attempted to disentangle the links between the gut microbiome, host liver metabolism, brain inflammation, and depression, as well as the role of the ratio of lactobacillus to clostridium [ 152 ]. The literature has also examined the links between medication, such as antibiotics, and mood and behaviour, with the findings showing that antibiotics may be related to depression [ 159 , 168 ]. The links between the microbiome and depression are complex, and further studies are needed to determine the underpinning causal mechanisms.

3.1.4. Inflammation

Studies on inflammation—key points:

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines are linked to depression

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, may play an important role

- Different methods of measurement are used, making the comparison of findings across studies difficult

Inflammation has been a theme in this literature review [ 60 , 161 , 164 , 169 , 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 ]. The findings show that raised levels of inflammation (because of factors such as pro-inflammatory cytokines) have been associated with depression [ 60 , 161 , 174 , 175 , 178 ]. For example, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, have been linked to depression [ 185 ]. Various determinants, such as early life stress, have also been linked to systemic inflammation, and this can increase the risk for depression [ 186 ].

Nevertheless, not everyone with elevated inflammation develops depression; therefore, this is just one route out of many linked to pathogenesis. Despite the compelling evidence reported with respect to inflammation, it is difficult to compare the findings across studies because of different methods used to assess depression and its risk factors.

3.1.5. Stress and HPA Axis Dysfunction

Studies on stress and HPA axis dysfunction—key points:

- Stress is linked to the release of proinflammatory factors

- The dysregulation of the HPA axis is linked to depression

- Determinants are interlinked in a complex web of causation

Stress was studied in various forms in rodent populations and humans [ 144 , 145 , 155 , 174 , 176 , 180 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 , 201 , 202 , 203 , 204 , 205 , 206 , 207 , 208 , 209 , 210 , 211 ].

Although this section has some overlap with others (as is to be expected because all of these determinants and body systems are interlinked), a number of studies have focused on the impact of stress on mental health. Stress has been mentioned in the literature as a risk factor of poor mental health and has emerged as an important determinant of depression. The effects of this variable are wide-ranging, and a short discussion is warranted.

Stress has been linked to the release of inflammatory factors, as well as the development of depression [ 204 ]. When the stress is high or lasts for a long period of time, this may negatively impact the brain. Chronic stress can impact the dendrites and synapses of various neurons, and may be implicated in the pathway leading to major depressive disorder [ 114 ]. As a review by Uchida et al. indicates, stress may be associated with the “dysregulation of neuronal and synaptic plasticity” [ 114 ]. Even in rodent studies, stress has a negative impact: chronic and unpredictable stress (and other forms of tension or stress) have been linked to unusual behaviour and depression symptoms [ 114 ].

The depression process and related brain changes, however, have also been linked to the hyperactivity or dysregulation of the HPA axis [ 127 , 130 , 131 , 182 , 212 ]. One review indicates that a potential underpinning mechanism of depression relates to “HPA axis abnormalities involved in chronic stress” [ 213 ]. There is a complex relationship between the HPA axis, glucocorticoid receptors, epigenetic mechanisms, and psychiatric sequelae [ 130 , 212 ].

In terms of the relationship between the HPA axis and stress and their influence on depression, the diathesis–stress model offers an explanation: it could be that early stress plays a role in the hyperactivation of the HPA axis, thus creating a predisposition “towards a maladaptive reaction to stress”. When this predisposition then meets an acute stressor, depression may ensue; thus, in line with the diathesis–stress model, a pre-existing vulnerability and stressor can create fertile ground for a mood disorder [ 213 ]. An integrated review by Dean and Keshavan [ 213 ] suggests that HPA axis hyperactivity is, in turn, related to other determinants, such as early deprivation and insecure early attachment; this again shows the complex web of causation between the different determinants.

3.1.6. Kynurenine Pathway

Studies on the kynurenine pathway—key points:

- The kynurenine pathway is linked to depression

- Indolamine 2,3-dioxegenase (IDO) polymorphisms are linked to postpartum depression

The kynurenine pathway was another theme that emerged in this review [ 120 , 178 , 181 , 184 , 214 , 215 , 216 , 217 , 218 , 219 , 220 , 221 ]. The kynurenine pathway has been implicated not only in general depressed mood (inflammation-induced depression) [ 184 , 214 , 219 ] but also postpartum depression [ 120 ]. When the kynurenine metabolism pathway is activated, this results in metabolites, which are neurotoxic.

A review by Jeon et al. notes a link between the impairment of the kynurenine pathway and inflammation-induced depression (triggered by treatment for various physical diseases, such as malignancy). The authors note that this could represent an important opportunity for immunopharmacology [ 214 ]. Another review by Danzer et al. suggests links between the inflammation-induced activation of indolamine 2,3-dioxegenase (the enzyme that converts tryptophan to kynurenine), the kynurenine metabolism pathway, and depression, and also remarks about the “opportunities for treatment of inflammation-induced depression” [ 184 ].

3.1.7. Cognition

Studies on cognition and the brain—key points:

- Cognitive decline and cognitive deficits are linked to increased depression risk

- Cognitive reserve is important in the disability/depression relationship

- Family history of cognitive impairment is linked to depression

A number of studies have focused on the theme of cognition and the brain. The results show that factors, such as low cognitive ability/function, cognitive vulnerability, cognitive impairment or deficits, subjective cognitive decline, regression of dendritic branching and hippocampal atrophy/death of hippocampal cells, impaired neuroplasticity, and neurogenesis-related aspects, have been linked to depression [ 131 , 212 , 222 , 223 , 224 , 225 , 226 , 227 , 228 , 229 , 230 , 231 , 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 , 236 , 237 , 238 , 239 ]. The cognitive reserve appears to act as a moderator and can magnify the impact of certain determinants on poor mental health. For example, in a study in which participants with multiple sclerosis also had low cognitive reserve, disability was shown to increase the risk for depression [ 63 ]. Cognitive deficits can be both causal and resultant in depression. A study on individuals attending outpatient stroke clinics showed that lower scores in cognition were related to depression; thus, cognitive impairment appears to be associated with depressive symptomatology [ 226 ]. Further, Halahakoon et al. [ 222 ] note a meta-analysis [ 240 ] that shows that a family history of cognitive impairment (in first degree relatives) is also linked to depression.

In addition to cognitive deficits, low-level cognitive ability [ 231 ] and cognitive vulnerability [ 232 ] have also been linked to depression. While cognitive impairment may be implicated in the pathogenesis of depressive symptoms [ 222 ], negative information processing biases are also important; according to the ‘cognitive neuropsychological’ model of depression, negative affective biases play a central part in the development of depression [ 222 , 241 ]. Nevertheless, the evidence on this topic is mixed and further work is needed to determine the underpinning mechanisms between these states.

3.2. Psychological Factors

Studies on psychological factors—key points:

- There are many affective risk factors linked to depression

- Determinants of depression include negative self-concept, sensitivity to rejection, neuroticism, rumination, negative emotionality, and others

A number of studies have been undertaken on the psychological factors linked to depression (including mastery, self-esteem, optimism, negative self-image, current or past mental health conditions, and various other aspects, including neuroticism, brooding, conflict, negative thinking, insight, cognitive fusion, emotional clarity, rumination, dysfunctional attitudes, interpretation bias, and attachment style) [ 66 , 128 , 140 , 205 , 210 , 228 , 235 , 242 , 243 , 244 , 245 , 246 , 247 , 248 , 249 , 250 , 251 , 252 , 253 , 254 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 , 266 , 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 , 271 , 272 , 273 , 274 , 275 , 276 , 277 , 278 , 279 , 280 , 281 , 282 , 283 , 284 , 285 , 286 , 287 , 288 , 289 , 290 ]. Determinants related to this condition include low self-esteem and shame, among other factors [ 269 , 270 , 275 , 278 ]. Several emotional states and traits, such as neuroticism [ 235 , 260 , 271 , 278 ], negative self-concept (with self-perceptions of worthlessness and uselessness), and negative interpretation or attention biases have been linked to depression [ 261 , 271 , 282 , 283 , 286 ]. Moreover, low emotional clarity has been associated with depression [ 267 ]. When it comes to the severity of the disorder, it appears that meta-emotions (“emotions that occur in response to other emotions (e.g., guilt about anger)” [ 268 ]) have a role to play in depression [ 268 ].

A determinant that has received much attention in mental health research concerns rumination. Rumination has been presented as a mediator but also as a risk factor for depression [ 57 , 210 , 259 ]. When studied as a risk factor, it appears that the relationship of rumination with depression is mediated by variables that include limited problem-solving ability and insufficient social support [ 259 ]. However, rumination also appears to act as a mediator: for example, this variable (particularly brooding rumination) lies on the causal pathway between poor attention control and depression [ 265 ]. This shows that determinants may present in several forms: as moderators or mediators, risk factors or outcomes, and this is why disentangling the relationships between the various factors linked to depression is a complex task.

The psychological determinants are commonly researched variables in the mental health literature. A wide range of factors have been linked to depression, such as the aforementioned determinants, but also: (low) optimism levels, maladaptive coping (such as avoidance), body image issues, and maladaptive perfectionism, among others [ 269 , 270 , 272 , 273 , 275 , 276 , 279 , 285 , 286 ]. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the way these determinants increase the risk for depression. One of the underpinning mechanisms linking the determinants and depression concerns coping. For example, positive fantasy engagement, cognitive biases, or personality dispositions may lead to emotion-focused coping, such as brooding, and subsequently increase the risk for depression [ 272 , 284 , 287 ]. Knowing the causal mechanisms linking the determinants to outcomes provides insight for the development of targeted interventions.

3.3. Social Determinants

Studies on social determinants—key points:

- Social determinants are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, etc.; these influence (mental) health [ 291 ]

- There are many social determinants linked to depression, such as sociodemographics, social support, adverse childhood experiences

- Determinants can be at the individual, social network, community, and societal levels

Studies also focused on the social determinants of (mental) health; these are the conditions in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, and age, and have a significant influence on wellbeing [ 291 ]. Factors such as age, social or socioeconomic status, social support, financial strain and deprivation, food insecurity, education, employment status, living arrangements, marital status, race, childhood conflict and bullying, violent crime exposure, abuse, discrimination, (self)-stigma, ethnicity and migrant status, working conditions, adverse or significant life events, illiteracy or health literacy, environmental events, job strain, and the built environment have been linked to depression, among others [ 52 , 133 , 235 , 236 , 239 , 252 , 269 , 280 , 292 , 293 , 294 , 295 , 296 , 297 , 298 , 299 , 300 , 301 , 302 , 303 , 304 , 305 , 306 , 307 , 308 , 309 , 310 , 311 , 312 , 313 , 314 , 315 , 316 , 317 , 318 , 319 , 320 , 321 , 322 , 323 , 324 , 325 , 326 , 327 , 328 , 329 , 330 , 331 , 332 , 333 , 334 , 335 , 336 , 337 , 338 , 339 , 340 , 341 , 342 , 343 , 344 , 345 , 346 , 347 , 348 , 349 , 350 , 351 , 352 , 353 , 354 , 355 , 356 , 357 , 358 , 359 , 360 , 361 , 362 , 363 , 364 , 365 , 366 , 367 , 368 , 369 , 370 , 371 ]. Social support and cohesion, as well as structural social capital, have also been identified as determinants [ 140 , 228 , 239 , 269 , 293 , 372 , 373 , 374 , 375 , 376 , 377 , 378 , 379 ]. In a study, part of the findings showed that low levels of education have been shown to be linked to post-stroke depression (but not severe or clinical depression outcomes) [ 299 ]. A study within a systematic review indicated that having only primary education was associated with a higher risk of depression compared to having secondary or higher education (although another study contrasted this finding) [ 296 ]. Various studies on socioeconomic status-related factors have been undertaken [ 239 , 297 ]; the research has shown that a low level of education is linked to depression [ 297 ]. Low income is also related to depressive disorders [ 312 ]. By contrast, high levels of education and income are protective [ 335 ].

A group of determinants touched upon by several studies included adverse childhood or early life experiences: ex. conflict with parents, early exposure to traumatic life events, bullying and childhood trauma were found to increase the risk of depression (ex. through pathways, such as inflammation, interaction effects, or cognitive biases) [ 161 , 182 , 258 , 358 , 362 , 380 ].

Gender-related factors were also found to play an important role with respect to mental health [ 235 , 381 , 382 , 383 , 384 , 385 ]. Gender inequalities can start early on in the lifecourse, and women were found to be twice as likely to have depression as men. Gender-related factors were linked to cognitive biases, resilience and vulnerabilities [ 362 , 384 ].

Determinants can impact mental health outcomes through underpinning mechanisms. For example, harmful determinants can influence the uptake of risk behaviours. Risk behaviours, such as sedentary behaviour, substance abuse and smoking/nicotine exposure, have been linked to depression [ 226 , 335 , 355 , 385 , 386 , 387 , 388 , 389 , 390 , 391 , 392 , 393 , 394 , 395 , 396 , 397 , 398 , 399 , 400 , 401 ]. Harmful determinants can also have an impact on diet. Indeed, dietary aspects and diet components (ex. vitamin D, folate, selenium intake, iron, vitamin B12, vitamin K, fiber intake, zinc) as well as diet-related inflammatory potential have been linked to depression outcomes [ 161 , 208 , 236 , 312 , 396 , 402 , 403 , 404 , 405 , 406 , 407 , 408 , 409 , 410 , 411 , 412 , 413 , 414 , 415 , 416 , 417 , 418 , 419 , 420 , 421 , 422 , 423 , 424 , 425 , 426 , 427 , 428 ]. A poor diet has been linked to depression through mechanisms such as inflammation [ 428 ].

Again, it is difficult to constrict diet to the ‘social determinants of health’ category as it also relates to inflammation (biological determinants) and could even stand alone as its own category. Nevertheless, all of these factors are interlinked and influence one another in a complex web of causation, as mentioned elsewhere in the paper.

Supplementary Figure S1 contains a representation of key determinants acting at various levels: the individual, social network, community, and societal levels. The determinants have an influence on risk behaviours, and this, in turn, can affect the mood (i.e., depression), body processes (ex. can increase inflammation), and may negatively influence brain structure and function.

3.4. Others

Studies on ‘other’ determinants—key points:

- A number of factors are related to depression

- These may not be as easily categorized as the other determinants in this paper

A number of factors arose in this review that were related to depression; it was difficult to place these under a specific heading above, so this ‘other’ category was created. A number of these could be sorted under the ‘social determinants of depression’ category. For example, being exposed to deprivation, hardship, or adversity may increase the risk for air pollution exposure and nighttime shift work, among others, and the latter determinants have been found to increase the risk for depression. Air pollution could also be regarded as an ecologic-level (environmental) determinant of mental health.

Nevertheless, we have decided to leave these factors in a separate category (because their categorization may not be as immediately clear-cut as others), and these factors include: low-level light [ 429 ], weight cycling [ 430 ], water contaminants [ 431 ], trade [ 432 ], air pollution [ 433 , 434 ], program-level variables (ex. feedback and learning experience) [ 435 ], TV viewing [ 436 ], falls [ 437 ], various other biological factors [ 116 , 136 , 141 , 151 , 164 , 182 , 363 , 364 , 438 , 439 , 440 , 441 , 442 , 443 , 444 , 445 , 446 , 447 , 448 , 449 , 450 , 451 , 452 , 453 , 454 , 455 , 456 , 457 , 458 , 459 , 460 , 461 , 462 , 463 , 464 , 465 , 466 , 467 , 468 , 469 ], mobile phone use [ 470 ], ultrasound chronic exposure [ 471 ], nighttime shift work [ 472 ], work accidents [ 473 ], therapy enrollment [ 226 ], and exposure to light at night [ 474 ].

4. Cross-Cutting Themes

4.1. lifecourse perspective.

Studies on the lifecourse perspective—key points:

- Early life has an importance on mental health

- Stress has been linked to depression

- In old age, the decline in social capital is important

Trajectories and life events are important when it comes to the lifecourse perspective. Research has touched on the influence of prenatal or early life stress on an individual’s mental health trajectory [ 164 , 199 , 475 ]. Severe stress that occurs in the form of early-life trauma has also been associated with depressive symptoms [ 362 , 380 ]. It may be that some individuals exposed to trauma develop thoughts of personal failure, which then serve as a catalyst of depression [ 380 ].

At the other end of the life trajectory—old age—specific determinants have been linked to an increased risk for depression. Older people are at a heightened risk of losing their social networks, and structural social capital has been identified as important in relation to depression in old age [ 293 ].

4.2. Gene–Environment Interactions

Studies on gene–environment interactions—key points:

- The environment and genetics interact to increase the risk of depression

- The etiology of depression is multifactorial

- Adolescence is a time of vulnerability

A number of studies have touched on gene–environment interactions [ 72 , 77 , 82 , 119 , 381 , 476 , 477 , 478 , 479 , 480 , 481 ]. The interactions between genetic factors and determinants, such as negative life events (ex. relationship and social difficulties, serious illness, unemployment and financial crises) and stressors (ex. death of spouse, minor violations of law, neighbourhood socioeconomic status) have been studied in relation to depression [ 82 , 135 , 298 , 449 , 481 ]. A study reported an interaction of significant life events with functional variation in the serotonin-transporter-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) allele type (in the context of multiple sclerosis) and linked this to depression [ 361 ], while another reported an interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR in relation to depression [ 480 ]. Other research reported that the genetic variation of HPA-axis genes has moderating effects on the relationship between stressors and depression [ 198 ]. Another study showed that early-life stress interacts with gene variants to increase the risk for depression [ 77 ].

Adolescence is a time of vulnerability [ 111 , 480 ]. Perceived parental support has been found to interact with genes (GABRR1, GABRR2), and this appears to be associated with depressive symptoms in adolescence [ 480 ]. It is important to pay special attention to critical periods in the lifecourse so that adequate support is provided to those who are most vulnerable.

The etiology of depression is multifactorial, and it is worthwhile to examine the interaction between multiple factors, such as epigenetic, genetic, and environmental factors, in order to truly understand this mental health condition. Finally, taking into account critical periods of life when assessing gene–environment interactions is important for developing targeted interventions.

5. Discussion

Depression is one of the most common mental health conditions, and, if left untreated, it can increase the risk for substance abuse, anxiety disorders, and suicide. In the past 20 years, a large number of studies on the risk and protective factors of depression have been undertaken in various fields, such as genetics, neurology, immunology, and epidemiology. However, there are limitations associated with the extant evidence base. The previous syntheses on depression are limited in scope and focus exclusively on social or biological factors, population sub-groups, or examine depression as a comorbidity (rather than an independent disorder). The research on the determinants and causal pathways of depression is fragmentated and heterogeneous, and this has not helped to stimulate progress when it comes to the prevention and intervention of this condition—specifically unravelling the complexity of the determinants related to this condition and thus refining the prevention and intervention methods.

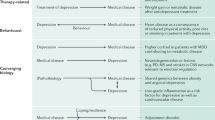

The scope of this paper was to bring together the heterogeneous, vast, and fragmented literature on depression and paint a picture of the key factors that contribute to this condition. The findings from this review show that there are important themes when it comes to the determinants of depression, such as: the microbiome, dysregulation of the HPA axis, inflammatory reactions, the kynurenine pathway, as well as psychological and social factors. It may be that physical factors are proximal determinants of depression, which, in turn, are acted on by more distal social factors, such as deprivation, environmental events, and social capital.

The Marmot Report [ 291 ], the World Health Organization [ 482 ], and Compton et al. [ 483 ] highlight that the most disadvantaged segments of society are suffering (the socioeconomic context is important), and this inequality in resources has translated to inequality in mental health outcomes [ 483 ]. To tackle the issue of egalitarianism and restore equality in the health between the groups, the social determinants need to be addressed [ 483 ]. A wide range of determinants of mental health have been identified in the literature: age, gender, ethnicity, family upbringing and early attachment patterns, social support, access to food, water and proper nutrition, and community factors. People spiral downwards because of individual- and societal-level circumstances; therefore, these circumstances along with the interactions between the determinants need to be considered.

Another important theme in the mental health literature is the lifecourse perspective. This shows that the timing of events has significance when it comes to mental health. Early life is a critical period during the lifespan at which cognitive processes develop. Exposure to harmful determinants, such as stress, during this period can place an individual on a trajectory of depression in adulthood or later life. When an individual is exposed to harmful determinants during critical periods and is also genetically predisposed to depression, the risk for the disorder can be compounded. This is why aspects such as the lifecourse perspective and gene–environment interactions need to be taken into account. Insight into this can also help to refine targeted interventions.

A number of interventions for depression have been developed or recommended, addressing, for example, the physical factors described here and lifestyle modifications. Interventions targeting various factors, such as education and socioeconomic status, are needed to help prevent and reduce the burden of depression. Further research on the efficacy of various interventions is needed. Additional studies are also needed on each of the themes described in this paper, for example: the biological factors related to postpartum depression [ 134 ], and further work is needed on depression outcomes, such as chronic, recurrent depression [ 452 ]. Previous literature has shown that chronic stress (associated with depression) is also linked to glucocorticoid receptor resistance, as well as problems with the regulation of the inflammatory response [ 484 ]. Further work is needed on this and the underpinning mechanisms between the determinants and outcomes. This review highlighted the myriad ways of measuring depression and its determinants [ 66 , 85 , 281 , 298 , 451 , 485 ]. Thus, the standardization of the measurements of the outcomes (ex. a gold standard for measuring depression) and determinants is essential; this can facilitate comparisons of findings across studies.

5.1. Strengths

This paper has important strengths. It brings together the wide literature on depression and helps to bridge disciplines in relation to one of the most common mental health problems. We identified, selected, and extracted data from studies, and provided concise summaries.

5.2. Limitations

The limitations of the review include missing potentially important studies; however, this is a weakness that cannot be avoided by literature reviews. Nevertheless, the aim of the review was not to identify each study that has been conducted on the risk and protective factors of depression (which a single review is unable to capture) but rather to gain insight into the breadth of literature on this topic, highlight key biological, psychological, and social determinants, and shed light on important themes, such as the lifecourse perspective and gene–environment interactions.

6. Conclusions

We have reviewed the determinants of depression and recognize that there are a multitude of risk and protective factors at the individual and wider ecologic levels. These determinants are interlinked and influence one another. We have attempted to describe the wide literature on this topic, and we have brought to light major factors that are of public mental health significance. This review may be used as an evidence base by those in public health, clinical practice, and research.

This paper discusses key areas in depression research; however, an exhaustive discussion of all the risk factors and determinants linked to depression and their mechanisms is not possible in one journal article—which, by its very nature, a single paper cannot do. We have brought to light overarching factors linked to depression and a workable conceptual framework that may guide clinical and public health practice; however, we encourage other researchers to continue to expand on this timely and relevant work—particularly as depression is a top priority on the policy agenda now.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Isla Kuhn for the help with the Medline, Scopus, and PsycInfo database searches.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci11121633/s1 , Figure S1: Conceptual framework: Determinants of depression, Table S1: Data charting—A selection of determinants from the literature.

Appendix A.1. Search Strategy

Search: ((((((((((((((((“Gene-Environment Interaction”[Majr]) OR (“Genetics”[Mesh])) OR (“Genome-Wide Association Study”[Majr])) OR (“Microbiota”[Mesh] OR “Gastrointestinal Microbiome”[Mesh])) OR (“Neurogenic Inflammation”[Mesh])) OR (“genetic determinant”)) OR (“gut-brain-axis”)) OR (“Kynurenine”[Majr])) OR (“Cognition”[Mesh])) OR (“Neuronal Plasticity”[Majr])) OR (“Neurogenesis”[Mesh])) OR (“Genes”[Mesh])) OR (“Neurology”[Majr])) OR (“Social Determinants of Health”[Majr])) OR (“Glucocorticoids”[Mesh])) OR (“Tryptophan”[Mesh])) AND (“Depression”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh]) Filters: from 2017—2020.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R)

- exp *Depression/

- exp *Depressive Disorder/

- exp *”Social Determinants of Health”/

- exp *Tryptophan/

- exp *Glucocorticoids/

- exp *Neurology/

- exp *Genes/

- exp *Neurogenesis/

- exp *Neuronal Plasticity/

- exp *Kynurenine/

- exp *Genetics/

- exp *Neurogenic Inflammation/

- exp *Gastrointestinal Microbiome/

- exp *Genome-Wide Association Study/

- exp *Gene-Environment Interaction/

- exp *Depression/et [Etiology]

- exp *Depressive Disorder/et

- or/4-16 637368

- limit 22 to yr = “2017–Current”

- “cause* of depression”.mp.

- “cause* of depression”.ti.

- (cause adj3 (depression or depressive)).ti.

- (caus* adj3 (depression or depressive)).ti.

Appendix A.2. PsycInfo

(TITLE ( depression OR “ Depressive Disorder ”) AND TITLE (“ Social Determinants of Health ” OR tryptophan OR glucocorticoids OR neurology OR genes OR neurogenesis OR “ Neuronal Plasticity ” OR kynurenine OR genetics OR “ Neurogenic Inflammation ” OR “ Gastrointestinal Microbiome ” OR “ Genome-Wide Association Study ” OR “ Gene-Environment Interaction ” OR aetiology OR etiology )) OR TITLE ( cause* W/3 ( depression OR depressive )).

Author Contributions

O.R. was responsible for the design of the study and methodology undertaken. Despite P.T.’s involvement in YPMH, he had no role in the design of the study; P.T. was responsible for the conceptualization of the study. Validation was conducted by O.R. and J.F.M. Formal analysis (data charting) was undertaken by O.R. O.R. and P.T. were involved in the investigation, resource acquisition, and data presentation. The original draft preparation was undertaken by O.R. The writing was conducted by O.R., with review and editing by P.T. and J.F.M. Funding acquisition was undertaken by O.R. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by The William Templeton Foundation for Young People’s Mental Health, Cambridge Philosophical Society, and the Aviva Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

7 Depression Research Paper Topic Ideas

Nancy Schimelpfening, MS is the administrator for the non-profit depression support group Depression Sanctuary. Nancy has a lifetime of experience with depression, experiencing firsthand how devastating this illness can be.

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

In psychology classes, it's common for students to write a depression research paper. Researching depression may be beneficial if you have a personal interest in this topic and want to learn more, or if you're simply passionate about this mental health issue. However, since depression is a very complex subject, it offers many possible topics to focus on, which may leave you wondering where to begin.

If this is how you feel, here are a few research titles about depression to help inspire your topic choice. You can use these suggestions as actual research titles about depression, or you can use them to lead you to other more in-depth topics that you can look into further for your depression research paper.

What Is Depression?

Everyone experiences times when they feel a little bit blue or sad. This is a normal part of being human. Depression, however, is a medical condition that is quite different from everyday moodiness.

Your depression research paper may explore the basics, or it might delve deeper into the definition of clinical depression or the difference between clinical depression and sadness .

What Research Says About the Psychology of Depression

Studies suggest that there are biological, psychological, and social aspects to depression, giving you many different areas to consider for your research title about depression.

Types of Depression

There are several different types of depression that are dependent on how an individual's depression symptoms manifest themselves. Depression symptoms may vary in severity or in what is causing them. For instance, major depressive disorder (MDD) may have no identifiable cause, while postpartum depression is typically linked to pregnancy and childbirth.

Depressive symptoms may also be part of an illness called bipolar disorder. This includes fluctuations between depressive episodes and a state of extreme elation called mania. Bipolar disorder is a topic that offers many research opportunities, from its definition and its causes to associated risks, symptoms, and treatment.

Causes of Depression

The possible causes of depression are many and not yet well understood. However, it most likely results from an interplay of genetic vulnerability and environmental factors. Your depression research paper could explore one or more of these causes and reference the latest research on the topic.

For instance, how does an imbalance in brain chemistry or poor nutrition relate to depression? Is there a relationship between the stressful, busier lives of today's society and the rise of depression? How can grief or a major medical condition lead to overwhelming sadness and depression?

Who Is at Risk for Depression?

This is a good research question about depression as certain risk factors may make a person more prone to developing this mental health condition, such as a family history of depression, adverse childhood experiences, stress , illness, and gender . This is not a complete list of all risk factors, however, it's a good place to start.

The growing rate of depression in children, teenagers, and young adults is an interesting subtopic you can focus on as well. Whether you dive into the reasons behind the increase in rates of depression or discuss the treatment options that are safe for young people, there is a lot of research available in this area and many unanswered questions to consider.

Depression Signs and Symptoms

The signs of depression are those outward manifestations of the illness that a doctor can observe when they examine a patient. For example, a lack of emotional responsiveness is a visible sign. On the other hand, symptoms are subjective things about the illness that only the patient can observe, such as feelings of guilt or sadness.

An illness such as depression is often invisible to the outside observer. That is why it is very important for patients to make an accurate accounting of all of their symptoms so their doctor can diagnose them properly. In your depression research paper, you may explore these "invisible" symptoms of depression in adults or explore how depression symptoms can be different in children .

How Is Depression Diagnosed?

This is another good depression research topic because, in some ways, the diagnosis of depression is more of an art than a science. Doctors must generally rely upon the patient's set of symptoms and what they can observe about them during their examination to make a diagnosis.

While there are certain laboratory tests that can be performed to rule out other medical illnesses as a cause of depression, there is not yet a definitive test for depression itself.

If you'd like to pursue this topic, you may want to start with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The fifth edition, known as DSM-5, offers a very detailed explanation that guides doctors to a diagnosis. You can also compare the current model of diagnosing depression to historical methods of diagnosis—how have these updates improved the way depression is treated?

Treatment Options for Depression

The first choice for depression treatment is generally an antidepressant medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most popular choice because they can be quite effective and tend to have fewer side effects than other types of antidepressants.

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, is another effective and common choice. It is especially efficacious when combined with antidepressant therapy. Certain other treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), are most commonly used for patients who do not respond to more common forms of treatment.

Focusing on one of these treatments is an option for your depression research paper. Comparing and contrasting several different types of treatment can also make a good research title about depression.

A Word From Verywell

The topic of depression really can take you down many different roads. When making your final decision on which to pursue in your depression research paper, it's often helpful to start by listing a few areas that pique your interest.

From there, consider doing a little preliminary research. You may come across something that grabs your attention like a new study, a controversial topic you didn't know about, or something that hits a personal note. This will help you narrow your focus, giving you your final research title about depression.

Remes O, Mendes JF, Templeton P. Biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression: A review of recent literature . Brain Sci . 2021;11(12):1633. doi:10.3390/brainsci11121633

National Institute of Mental Health. Depression .

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition . American Psychiatric Association.

National Institute of Mental Health. Mental health medications .

Ferri, F. F. (2019). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2020 E-Book: 5 Books in 1 . Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences.

By Nancy Schimelpfening Nancy Schimelpfening, MS is the administrator for the non-profit depression support group Depression Sanctuary. Nancy has a lifetime of experience with depression, experiencing firsthand how devastating this illness can be.

Clinical Trials

Teen depression.

Displaying 12 studies

The purpose of this study is to gather information regarding the use of rTMS as a treatment for depression in adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder. The investigators also hope to learn if measures of brain activity (cortical excitability and inhibition) collected with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) can be used to identify which patients will benefit from certain types of rTMS treatment.

This research proposal aims to better understand the neurobiology of depression in adolescents and how repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) may therapeutically impact brain function and mood. This investigation also proposes the first study to examine the efficacy of rTMS maintenance therapy in adolescents who have met clinical criteria following acute rTMS treatment. The magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy pattern of rTMS response will be analyzed according to previously established protocols.

The overall goal of this investigator-initiated trial is to evaluate the impact of platform algorithm products designed to rapidly identify pharmacokinetic (PK) and/or pharmacodynamic (PD) genomic variation on treatment outcome of depression in adolescents. This new technology may have the potential to optimize treatment selection by improving response, minimizing unfavorable adverse events / side effects and increasing treatment adherence

This research study aims to test the safety and effectiveness of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on teens with depression. The study also seeks to understand how rTMS treatment affects the neurobiology of teens with depression.

The purpose of this study is to learn if measures of brain chemicals from a brain scan called Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy (MRI/MRS) and brain activity (known as cortical excitability and inhibition) collected by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) are different in adolescents with depression who are in different stages of treatment. Researchers are conducting this study to learn more about how the brain works in adolescents with depression and without depression (healthy controls). This is important because it may identify a biological marker (a measure of how bad an illness is) for depression that could one day be used ...

The purpose of this study is to contribute to our understanding of the relationships between social media use in adolescents and psychological development, psychiatric comorbidity, and physiological markers of stress.

The proposed study seeks to obtain preliminary signal of the tolerability and efficacy of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for depressive symptoms in a sample of adolescents with depression and epilepsy. Additionally, effects of tDCS will be assessed via electroencephalographic, cognitive, and psychosocial measures.

In an effort to understand the effects of evidence-based interventions on children and adolescents, the aims of this study are to 1) evaluate the feasibility of utilizing wearable devices to track health information (i.e., sleep, physical activity); 2) evaluate the effectiveness of evidence-based intervention components on emotional and interpersonal functioning, family engagement, and sleep and physical activity level outcomes.

The purpose of this study is to:

- Increase screening of adolescents for symptoms of depression in primary care La Crosse, WI clinics using the PHQ9M screening tool.Screening to occur at all well child visits and all subsequent visits for adolescents with Depression on their problem list.Clinics to include Pediatrics, Family Medicine, Family Health, Center for Womens Health.

- Develop a clear care pathway for adolescents identified with clinically meaningful symptoms of depression through increased screening, referral and treatment options. Pathway may include psychoeducational materials (multimedia options), intake paperwork and process for Department of Behavioral Health locally, and ...

The purpose of this study is to study brain chemistry in depressed patients compared to healthy patients who are not depressed.

The proposed study will examine sequential bilateral accelerated theta burst stimulation (aTBS). Three sessions are administered daily for 10 days (5 days per week). During each session continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) in which 1800 pulses are delivered continuously over 120 seconds to the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (RDPFC) is administered first, followed by iTBS in which 1800 pulses are delivered in 2 second bursts, repeated every 10 seconds for 570 seconds (1800 pulses) to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (LDPFC). The theta burst stimulation (TBS) parameters were adopted from prior work, with 3-pulse 50 Hz bursts given ...

The purpose of this study is to see if there is a connection between bad experiences in the patient's childhood, either by the patient or the parent, and poor blood sugar control, obesity, poor blood lipid levels, and depression in patients with type 1 diabetes.

Mayo Clinic Footer

- Request Appointment

- About Mayo Clinic

- About This Site

Legal Conditions and Terms

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Manage Cookies

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

- Advertising and sponsorship policy

- Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint Permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 May 2024

Assessment of depression symptoms among cancer patients: a cross-sectional study from a developing country

- Maher Battat 1 ,

- Nawal Omair 2 ,

- Mohammad A. WildAli 2 ,

- Aidah Alkaissi 3 ,

- Riad Amer 2 , 4 ,

- Amer A. Koni 5 , 6 ,

- Husam T. Salameh 2 , 4 &

- Sa’ed H. Zyoud 6 , 7 , 8

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 11934 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

197 Accesses

Metrics details

- Health care

Cancer patients experience psychological symptoms such as depression during the cancer treatment period, which increases the burden of symptoms. Depression severity can be assessed using the beck depression inventory (BDI II). The purpose of the study was to use BDI-II scores to measure depression symptoms in cancer patients at a large tertiary hospital in Palestine. A convenience sample of 271 cancer patients was used for a cross-sectional survey. There are descriptions of demographic, clinical, and lifestyle aspects. In addition, the BDI-II is a tool for determining the severity of depression. Two hundred seventy-one patients participated in the survey, for a 95% response rate. Patients ranged in age from 18 to 84 years, with an average age of 47 years. The male-to-female ratio was approximately 1:1, and 59.4% of the patients were outpatients, 153 (56.5%) of whom had hematologic malignancies. Most cancer patients ( n = 104, 38.4%) had minimal depression, while 22.5%, 22.1%, and 17.0% had mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. Education level, economic status, smoking status, and age were significantly associated with depression. The BDI-II is a useful instrument for monitoring depressive symptoms. The findings support the practice of routinely testing cancer patients for depressive symptoms as part of standard care and referring patients who are at a higher risk of developing psychological morbidity to specialists for treatment as needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Association of pre-existing depression with all-cause, cancer-related, and noncancer-related mortality among 5-year cancer survivors: a population-based cohort study

Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies

Comorbid depression in medical diseases

Introduction.

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality both worldwide and in Palestine, accounting for 14% of all deaths, after heart disease (30%) 1 , 2 . Additionally, the anticipated rise in cancer diagnoses among Palestinians is likely to place added strain on the already stretched financial and infrastructural resources of the healthcare system, particularly given the prevailing financial and political uncertainties 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 . As advancements in cancer treatments progress, more patients are experiencing either complete cures or extended life expectancies. As a result, there is increased focus on the emotional challenges that come with being diagnosed with and treated for cancer. Research indicates that approximately 30% of patients experience mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders 6 , although the exact prevalence varies depending on the specific condition 7 . Treating depression can lead to better emotional and psychological health, even amidst the physical toll of cancer symptoms. Mood plays a significant role in how patients perceive their quality of life (QoL) and the extent of their suffering. It can begin at the time of diagnosis and continue beyond the completion of cancer treatment 8 .

Depression is associated with decreased functional status, decreased adherence to treatment, longer hospitalizations, and the desire to die sooner 9 . Almost 25% of cancer patients experience severe depressive symptoms, whereas 77% of those with advanced disease experience severe depressive symptoms 10 . Depression is common in cancer patients and is strongly associated with oropharyngeal (22–57%), pancreatic (33 to 50%), breast (1.5–46%), and lung (11 to 44%) cancer. Patients with other malignancies, such as colon (13–25%), gynecological (12–23%), and lymphoma (8–19%), had a lower frequency of depression 7 .

Depressive symptoms are often identical to those of physical illness or its treatments, making it difficult to diagnose depression in physically ill people. This is especially true when a cancer patient is diagnosed with depression. Many of the symptoms needed to diagnose depression are often caused by cancer treatments (e.g. chemotherapy, biological therapy), such as fatigue, weight loss, anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure in typically enjoyable activities) and psychomotor retardation.

Depression, also known as clinical depression or severe depressive disorder, is a prevalent yet serious mood disorder. It manifests as severe symptoms that impact a person's emotions, thoughts, and ability to cope with daily activities such as sleeping, eating, and working. These symptoms must persist for at least two weeks to be diagnosed 7 .

Various techniques have been created to evaluate how well symptoms are managed, aiding in the recognition of linked symptoms. For instance, the beck depression inventory (BDI II)-21 is capable of evaluating prevalent psychological symptoms among cancer patients. The BDI-II remains instrumental in exploring the characteristics and evaluation of depression. Its effectiveness as a screening tool in patients with medical conditions and cancer has been examined in multiple research studies, establishing it as a reliable self-reported assessment tool 11 .

Cancer patients suffer many symptoms during cancer progression that negatively affect their QoL. Importantly, there is no comforting care assessment tool, such as the BDI, available for cancer patients in Palestine. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate cancer patients’ reported depression symptoms using the beck depression scale (BDS) at a large tertiary care hospital. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study assessing depression using the BDI-II in occupied Palestinian territories in the context of mental health.

Study design

The research objectives were pursued through a quantitative cross-sectional investigation.

Study setting

An-Najah National University Hospital (NNUH) was established in 2013 through a partnership with the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. NNUH stands as Palestine's sole facility, offering sophisticated electrophysiology, intricate open-heart surgeries, autologous bone marrow transplants, and specialized care for both adult and pediatric leukemia patients. NNUH encompasses various medical units, an emergency ward, dialysis facilities, radiology services, and ultrasound and tomography departments and has a capacity of 120 beds 12 .

Study population

Cancer patients receive comprehensive care through outpatient oncology clinics and inpatient services at NNUH. These services cover various procedures, including diagnosis, chemotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation (autoBMT), and the management of treatment side effects or complications. In certain oncological scenarios, such as neutropenic fever, patients may require immediate attention, leading to visits to the emergency room followed by hospital admission. This integrated approach ensures that patients receive comprehensive and timely care for their cancer treatment needs at NNUH.

Sample size

During the research period spanning from April 2021 to August 2021, the NNUH received an average of 600 cancer patients each month. This number served as the basis for determining the necessary sample size for analysis. Using the Raosoft sample size calculator with a response distribution of 0.50, an error margin of 5%, and a confidence interval of 95%, a preliminary sample size of 235 was calculated. However, to accommodate potential dropout rates, this figure was adjusted, indicating a requirement of 259 patients. To bolster the study's robustness and mitigate the risk of erroneous results, an additional 10% of the sample (24 patients) was included, bringing the final targeted sample size to 285. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were evaluated through content validity, construct validity, and reliability testing methods. Hence, we only used triangulation, involving two hemato-oncology physicians, three oncology nurses, and one statistician, to verify the validity of the data. We also assessed the consistency of 11 patients (22 questionnaires) between their two visits. Moreover, after creating the questionnaire, we piloted it on 11 patients, making adjustments as necessary based on their feedback.

Sampling procedure

The researchers utilized convenience sampling, involving 271 cancer patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria.

Ensuring that patients agree to participate is vital for ethical research.

The ability to read and write at age 18 ensures that patients can understand the study information and provide feedback.

Specifying cancer and hematologic malignancies keeps the study focused on the relevant patient population. Both inpatients and outpatients are included to capture a broader range of experiences.

Exclusion criteria

Patients in the ICU may be too critically ill to participate effectively.

Patients in a coma were unable to consent or participate in the study.

Patients with preexisting cognitive issues may not be able to understand or participate in the study reliably.

Isolated patients may have difficulty communicating or require special protocols that the study may not be equipped for.

Data collection instrument

Patients completed the questionnaires themselves, and nurses explained the questions if patients requested further clarification. All surveys were performed on paper and then analyzed using an electronic database. This study involved a secondary analysis of previously published data using various approaches in another study on factors related to palliative care symptoms in cancer patients in Palestine 13 . The data included patient demographics and clinical characteristics collected at various points during cancer treatment, such as diagnosis, chemotherapy, clinic visits, AutoBMT, advanced cancer stages, outpatient and inpatient oncology visits, and related factors. The data were collected over 5 months, from April to August 2021. Patients were provided with the Arabic version of the BDI-II 14 by either the researcher or a designated nurse and were encouraged to fill it out themselves, with assistance available if needed.

The surveys were kept in a designated location within particular departments designed for adult patients with cancer. These departments included outpatient oncology clinics, medical oncology units, vascular units, surgical units, bone marrow transplant and leukemia units, and surgical cardiac care units. Furthermore, the researcher gathered additional medical data from the patients' records. Approximately 15 patients chose not to participate, and 10 surveys were unfinished. Assessment tools for psychological symptoms, such as the BDI-II, provide a baseline assessment and evaluation for depression in cancer patients.

Beck depression inventory (BDI) II

Many factors contribute to the variation in depression incidence, including patient age and sex, medical status, cancer diagnosis, and cancer stage 15 . Hence, these inquiries also aid in evaluating depression among individuals with cancer. Moreover, questions regarding the diagnostic approach (such as inclusion or substitution methods), the type of assessment utilized (including diagnostic interviews or self-reported measures), and the criteria for inclusion (whether clinical or subclinical) are crucial for assessing depression within this demographic group.

The BDI, short for Beck Depression Inventory, is a tool consisting of 21-point self-assessment ratings designed to gauge attitudes and symptoms of depression. Completing the BDI typically takes approximately 10 min, yet individuals are required to possess a reading level equivalent to fifth or sixth grade to comprehend the questionnaire adequately. Clinicians employ this inventory to ascertain the severity of depression in individuals and tailor appropriate therapeutic interventions. The BDI was developed by Aaron T. Beck, a prominent psychiatrist recognized as the pioneer of cognitive behavior therapy 16 .

Depression is a medical condition characterized by a prolonged feeling of sadness. This leads to a lack of interest in previously enjoyable activities and can greatly disrupt daily life. While experiencing sadness is normal in response to events such as the loss of a loved one, financial strain, relationship issues, or job loss, clinical depression occurs when these feelings persist for an extended period without an obvious cause 16 .

Questions on the BDI-II

The BDI-II comprises 21 inquiries aligned with the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-V, which professionals use to assess mental health conditions. Each question offers multiple-choice responses with scores ranging from 0 to 3. These questions address various aspects, such as feelings of sadness, pessimism, past failures, loss of pleasure, guilt, self-criticism, suicidal thoughts, agitation, changes in sleeping and eating patterns, concentration difficulties, fatigue, and diminished interest in activities once enjoyed.

Scores on the BDI-II

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) utilizes a straightforward scoring method in which each of the four multiple-choice options is given a score ranging from 0 to 3. After all 21 questions are answered, the total points are tallied. Based on the total score, the severity of depression was categorized as follows: no depression (0–13 points), mild depression (14–19 points), moderate depression (20–28 points), or severe depression (29–63 points) 16 .

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Social Sciences Statistical Package (SPSS) version 21. Basic demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. When comparing continuous variables provided as the median and interquartile range, Mann‒Whitney U /Kruskal‒Wallis tests were used. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of An-Najah National University and the NNUH administrator approved this study. All methods used in the study were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Helsinki Declaration. Participants signed an informed consent form guaranteeing data privacy, and all the data were kept confidential and used exclusively for research purposes.

Demographic data