An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Neurobiology of gender identity and sexual orientation

Sexual identity and sexual orientation are independent components of a person’s sexual identity. These dimensions are most often in harmony with each other and with an individual’s genital sex, although not always. The present review discusses the relationship of sexual identity and sexual orientation to prenatal factors that act to shape the development of the brain and the expression of sexual behaviours in animals and humans. One major influence discussed relates to organisational effects that the early hormone environment exerts on both gender identity and sexual orientation. Evidence that gender identity and sexual orientation are masculinised by prenatal exposure to testosterone and feminised in it absence is drawn from basic research in animals, correlations of biometric indices of androgen exposure and studies of clinical conditions associated with disorders in sexual development. There are, however, important exceptions to this theory that have yet to be resolved. Family and twin studies indicate that genes play a role, although no specific candidate genes have been identified. Evidence that relates to the number of older brothers implicates maternal immune responses as a contributing factor for male sexual orientation. It remains speculative how these influences might relate to each other and interact with postnatal socialisation. Nonetheless, despite the many challenges to research in this area, existing empirical evidence makes it clear that there is a significant biological contribution to the development of an individual’s sexual identity and sexual orientation.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Gender identity and sexual orientation are fundamental independent characteristics of an individual’s sexual identity. 1 Gender identity refers to a person’s innermost concept of self as male, female or something else and can be the same or different from one’s physical sex. 2 Sexual orientation refers to an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic and/or sexual attractions to men, women or both sexes. 3 Both gender identity and sexual orientation are characterised by obvious sex differences. Most genetic females identify as such and are attracted to males (ie, androphilic) and most genetic males identify as males and are attracted to females (ie, gynophilic). The existence of these dramatic sex differences suggest that gonadal hormones, particularly testosterone, might be involved, given that testosterone plays an important role in the development of most, behavioural sex differences in other species. Here, a review is provided of the evidence that testosterone influences human gender identity and sexual orientation. The review begins by summarising the available information on sex hormones and brain development in other species that forms the underpinnings of the hypothesis suggesting that these human behaviours are programmed by the prenatal hormone environment, and it will also consider contributions from genes. This is followed by a critical evaluation of the evidence in humans and relevant animal models that relates sexual identity and sexual orientation to the influences that genes and hormones have over brain development.

2 |. HORMONES, GENES AND SEXUAL DIFFERENTIATION OF THE BRAIN AND BEHAVIOUR

The empirical basis for hypothesising that gonadal hormones influence gender identity and sexual orientation is based on animal experiments involving manipulations of hormones during prenatal and early neonatal development. It is accepted dogma that testes develop from the embryonic gonad under the influence of a cascade of genes that begins with the expression of the sex-determining gene SRY on the Y chromosome. 4 , 5 Before this time, the embryonic gonad is “indifferent”, meaning that it has the potential to develop into either a testis or an ovary. Likewise, the early embryo has 2 systems of ducts associated with urogenital differentiation, Wolffian and Müllerian ducts, which are capable of developing into the male and female tubular reproductive tracts, respectively. Once the testes develop, they begin producing 2 hormones, testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH). In rats, this occurs around day 16–17 of gestation, whereas, in humans, it occurs at about 7–8 weeks of gestation. 6 Testosterone and one of its derivatives, dihydrotestosterone, induce the differentiation of other organs in the male reproductive system, whereas AMH causes the degeneration of the Müllerian ducts. Female ovaries develop under the influence of a competing set of genes that are influenced by expression of DAX1 on the X chromosome and act antagonistically to SRY. The female reproductive tract in the embryo develops in the absence of androgens and later matures under the influence hormones produced by the ovary, in particular oestradiol.

Analogous processes occur during early development for sexual differentiation of the mammalian brain and behaviour. According to the classical or organisational theory, 7 , 8 prenatal and neonatal exposure to testosterone causes male-typical development (masculinisation), whereas female-typical development (feminisation) occurs in the relative absence of testosterone. Masculinisation involves permanent neural changes induced by steroid hormones and differs from the more transient activational effects observed after puberty. These effects typically occur during a brief critical period in development when the brain is most sensitive to testosterone or its metabolite oestradiol. In rats, the formation of oestradiol in the brain by aromatisation of circulating testosterone is the most important mechanism for the masculinisation of the brain; 9 however, as shown below, testosterone probably acts directly without conversion to oestradiol to influence human gender identity and sexual orientation. The times when testosterone triggers brain sexual differentiation in different species correspond to periods when testosterone is most elevated in males compared to females. In rodents and other altricial species, this occurs largely during the first 5 days after birth, whereas, in humans, the elevation in testosterone occurs between months 2 and 6 of pregnancy and then again from 1 to 3 months postnatally. 6 During these times, testosterone levels in the circulation are much higher in males than in females. These foetal and neonatal peaks of testosterone, together with functional steroid receptor activity, are considered to program the male brain both phenotypically and neurologically. In animal models, programming or organising actions are linked to direct effects on the various aspects of neural development that influence cell survival, neuronal connectivity and neurochemical specification. 10 Many of these effects occur well after the initial hormone exposure and have recently been linked to epigenetic mechanisms. 11

The regional brain differences that result from the interaction between hormones and developing brain cells are assumed to be the major basis of sex differences in a wide spectrum of adult behaviours, such as sexual behaviour, aggression and cognition, as well as gender identity and sexual orientation. Factors that interfere with the interactions between hormones and the developing brain systems during gestation may permanently influence later behaviour. Studies in sheep and primates have clearly demonstrated that sexual differentiation of the genitals takes places earlier in development and is separate from sexual differentiation of the brain and behaviour. 12 , 13 In humans, the genitals differentiate in the first trimester of pregnancy, whereas brain differentiation is considered to start in the second trimester. Usually, the processes are coordinated and the sex of the genitals and brain correspond. However, it is hypothetically possible that, in rare cases, these events could be influenced independently of each other and result in people who identify with a gender different from their physical sex. A similar reasoning has been invoked to explain the role of prenatal hormones on sexual orientation.

Although the role of gonadal steroids in the sexual differentiation of reproductive brain function and behaviour is undeniable, males and females also carry a different complement of genes encoded on their sex chromosomes that also influence sexual differentiation of the brain. 14 – 16 As will be discussed, family and twin studies suggest that there is a genetic component to gender identity and sexual orientation at least in some individuals. However, the nature of any genetic predisposition is unknown. The genetic component could be coding directly for these traits or, alternatively, could influence hormonal mechanisms by determining levels of hormones, receptors or enzymes. Genetic factors and hormones could also make separate yet complementary or antagonistic contributions. It should be noted that, although the early hormone environment appears to influence gender identity and sexual orientation, hormone levels in adulthood do not. There are no reports indicating that androgen levels differ as a function of gender identity or sexual orientation or that treatment with exogenous hormones alters these traits in either sex.

3 |. GENDER IDENTITY

The establishment of gender identity is a complex phenomenon and the diversity of gender expression argues against a simple or unitary explanation. For this reason, the extent to which it is determined by social vs biological (ie, genes and hormones) factors continues to be debated vigorously. 17 The biological basis of gender identity cannot be modelled in animals and is best studied in people who identify with a gender that is different from the sex of their genitals, in particular transsexual people. Several extensive reviews by Dick Swaab and coworkers elaborate the current evidence for an array of prenatal factors that influence gender identity, including genes and hormones. 18 – 20

3.1 |. Genes

Evidence of a genetic contribution to transsexuality is very limited. 21 There are few reports of family and twin studies of transsexuals but none offer clear support for the involvement of genetic factors. 22 – 24 Polymorphisms in sex hormone-related genes for synthetic enzymes and receptors have been studied based on the assumption that these may be involved in gender identity development. An increased incidence of an A2 allele polymorphism for CYP17A1 (ie, 17ɑ-hydroxylase/17, 20 lyase, the enzyme catalysing testosterone synthesis) was found in female-to-male (FtM) but not in male-to-female (MtF) transsexuals. 25 No associations were found between a 5ɑ-reductase (ie, the enzyme converting testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone) gene polymorphism in either MtF or FtM transsexuals. 26 There are also conflicting reports of associations between polymorphisms in the androgen receptor, oestrogen receptor β and CYP19 (ie, aromatase, the enzymes catalysing oestradiol synthesis). 27 – 29 A recent study using deep sequencing detected three low allele frequency gene mutants (i.e., FBXO38 [chr5:147774428; T>G], SMOC2 [chr6:169051385; A>G] and TDRP [chr8:442616; A>G]) between monozygotic twins discordant for gender dysphoria. 30 Further investigations including functional analysis and epidemiological analysis are needed to confirm the significance of the mutations found in this study. Overall, these genetic studies are inconclusive and a role for genes in gender identity remains unsettled.

3.2 |. Hormones

The evidence that prenatal hormones affect the development of gender identity is stronger but far from proven. One indication that exposure to prenatal testosterone has permanent effects on gender identity comes from the unfortunate case of David Reimer. 31 As an infant, Reimer underwent a faulty circumcision and was surgically reassigned, given hormone treatments and raised as a girl. He was never happy living as a girl and, years later, when he found out what happened to him, he transitioned to living as a man. However, for at least the first 8 months of life, this child was reared as a boy and it is not possible to know what impact rearing had on his dissatisfaction with a female sex assignment. 1 Other clinical studies have reported that male gender identity emerges in some XY children born with poorly formed or ambiguous genitals as a result of cloacal exstrophy, 5ɑ-reductase or 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency and raised as girls from birth. 32 , 33 All of these individuals were exposed to testosterone prenatally emphasising a potential role for androgens in gender development and raising doubts that children are psychosexually neutral at birth. 20 On the other hand, XY individuals born with an androgen receptor mutation causing complete androgen insensitivity are phenotypically female, identify as female and are most often androphilic, indicating that androgens act directly on the brain without the need for aromatisation to oestradiol. 34

3.3 |. Neuroanatomy

Further evidence that the organisational hormone theory applies to development of gender identity comes from observations that structural and functional brain characteristics are more similar between transgender people and control subjects with the same gender identity than between individuals sharing their biological sex. This includes local differences in the number of neurones and volume of subcortical nuclei such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, 35 , 36 numbers of kisspeptin and neurokinin B neurones in the infundibulum, 37 , 38 structural differences of gray 39 , 40 and white matter microstructure, 41 – 43 neural responses to sexually-relevant odours 44 , 45 and visuospatial functioning. 46 However, in some cases, the interpretation of these studies is complicated by hormone treatments, small sample sizes and a failure to disentangle correlates of sexual orientation from gender identity. 47 The fact that these differences extend beyond brain areas and circuits classically associated with sexual and endocrine functions raises the possibility that transsexuality is also associated with changes in cerebral networks involved in self-perception.

4 |. SEXUAL ORIENTATION

Research over several decades has demonstrated that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex to exclusive attraction to the same sex. 48 However, sexual orientation is usually discussed in terms of 3 categories: heterosexual (having emotional, romantic or sexual attractions to members of the other sex), homosexual (having emotional, romantic or sexual attractions to members of one’s own sex) and bisexual (having emotional, romantic or sexual attractions to both men and women). Most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation. There is no scientifically convincing research to show that therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation (ie, reparative or conversion therapy) is safe or effective. 3 The origin of sexual orientation is far from being understood, although there is no proof that it is affected by social factors after birth. On the other hand, a large amount of empirical data suggests that genes and hormones are important regulators of sexual orientation. 49 – 51 Useful animal models and experimental paradigms in animals have helped frame questions and propose hypotheses relevant to human sexual orientation.

4.1 |. Animal studies

Sexual partner preference is one of the most sexually dimorphic behaviours observed in animals and humans. Typically, males choose to mate with females and females choose to mate with males. Sexual partner preferences can be studied in animals by using sexual partner preference tests and recording the amount of time spent alone or interacting with the same or opposite sex stimulus animal. Although imperfect, tests of sexual partner preference or mate choice in animals have been used to model human sexual orientation. As reviewed comprehensively by Adkins-Regan 52 and Henley et al, 53 studies demonstrate that perinatal sex steroids have a large impact on organising mate choice in several species of animals, including birds, mice, rats, hamsters, ferrets and pigs. In particular, perinatal exposure to testosterone or its metabolite oestradiol programs male-typical (ie, gynophilic) partner preferences and neonatal deprivation of testosterone attenuates the preference that adult males show typically. In the absence of high concentrations of sex steroid levels or receptor-mediated activity during development, a female-typical (ie, androphilic) sexual preference for male sex partners develops.

Sexually dimorphic neural groups in the medial preoptic area of rats and ferrets have been associated with sexual partner preferences. In male rats, a positive correlation was demonstrated between the volume of the sexual dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN) and the animal’s preference for a receptive female, 54 although this was not replicated in a recent study. 55 Furthermore, in both rats and ferrets, destruction of the SDN caused males to show either neutral or androphilic preferences. 56

Naturally occurring same-sex interactions involving genital arousal have been reported in hundreds of animal species; however, they often appear to be motivated by purposes other than sex and may serve to facilitate other social goals. 57 , 58 Exclusive and enduring same-sex orientation is, however, extremely rare among animals and has only been documented conclusively and studied systematically in certain breeds of domestic sheep. 59 , 60 Approximately 6% to 8% of Western-breed domestic rams choose to exclusively court and mount other rams, but never ewes, when given a choice. No social factors, such as the general practice of rearing in same sex groups or an animal’s dominance rank, were found to affect sexual partner preferences in rams. Consistent with the organisational theory of sexual differentiation, sheep have an ovine sexually dimorphic preoptic nucleus (oSDN) that is larger and contains more neurones in female-oriented (gynophilic) rams than in male-oriented rams (androphilic) and ewes (androphilic). 61 Thus, morphological features of the oSDN correlate with a sheep’s sexual partner preference. The oSDN already exists and is larger in males than in females before sheep are born, suggesting that it could play a causal role in behaviour. 62 The oSDN differentiates under the influence of prenatal testosterone after the male genitals develop, but is unaffected by hormone treatment in adulthood. 63 Appropriately timed experimental exposure of female lamb foetuses to testosterone can alter oSDN size independently of genetic and phenotypic sex. 13 However, males appear to be resistant to suppression of the action of androgen during gestation because the foetal hypothalamic-pituitary-axis is active in the second trimester (term pregnancy approximately 150 days) and mitigates against changes in circulating testosterone that could disrupt brain masculinisation. 64 These data suggest that, in sheep, brain sexual differentiation is initiated during gestation by central mechanisms acting through gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones to stimulate and maintain the foetal testicular testosterone synthesis needed to masculinise the oSDN and behaviour. More research is required to understand the parameters of oSDN development and to causally relate its function to sexual partner preferences in sheep. Nonetheless, when considered together, the body of animal research strongly indicates that male-typical partner preferences are controlled at least in part by the neural groups in the preoptic area that differentiate under the influence of pre- and perinatal sex steroids.

4.2 |. Human studies

4.2.1 |. genes.

Evidence from family and twin studies suggests that there is a moderate genetic component to sexual orientation. 50 One recent study estimated that approximately 40% of the variance in sexual orientation in men is controlled by genes, whereas, in women, the estimate is approximately 20%. 65 In 1993, Hamer et al 66 published the first genetic linkage study that suggested a specific stretch of the X chromosome called Xq28 holds a gene or genes that predispose a man to being homosexual. These results were consistent with the observations that, when there is male homosexuality in a family, there is a greater probability of homosexual males on the mother’s side of the family than on the father’s side. The study was criticised for containing only 38 pairs of gay brothers and the original finding was not replicated by an independent group. 67 Larger genome-wide scans support an association with Xq28 and also found associations with chromosome 7 and 8, 68 , 69 although this has also been disputed. 70 Scientists at the personal genomics company 23andme performed the only genome-wide association study of sexual orientation that looked within the general population. 71 The results were presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Human Genetics in 2012, although they have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal. Although no genetic loci reaching genome-wide significance for homosexuality among men or women, the genetic marker closest to significance was located in the same region of chromosome 8 in men as that implicated in linkage studies. Other molecular genetic evidence suggests that epigenetic factors could influence male sexual orientation, although this has yet to be demonstrated. 72 , 73

4.2.2 |. Hormones

The leading biological theory of sexual orientation in humans, as in animals, draws on the application of the organisational theory of sexual differentiation. However, this theory cannot be directly tested because it is not ethical to experimentally administer hormones to pregnant women and test their effect on the sexual orientation of their children. Naturally occurring and iatrogenic disorders of sex development that involve dramatic alterations in hormone action or exposure lend some support to a role for prenatal hormones, although these cases are extremely rare and often difficult to interpret. 74 Despite these limitations, two clinical conditions are presented briefly that lend some support for the organisational theory. More comprehensive presentations of the clinical evidence on this topic can be found in several excellent reviews. 74 – 76

Women born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and exposed to abnormally high levels of androgens in utero show masculinised genitals, play behaviour and aggression. 74 , 77 They also are less likely to be exclusively heterosexual and report more same-sex activity than unaffected women, which suggests that typical female sexual development is disrupted. Although it appears plausible that these behavioural traits are mediated through effects of elevated androgens on the brain, it is also possible that the sexuality of CAH women may have also been impacted by the physical and psychological consequences of living with genital anomalies or more nuanced effects of socialisation. 78 There is also evidence for prenatal androgen effects on sexual orientation in XY individuals born with cloacal exstrophy. It was reported originally that a significant number of these individuals eventually adopt a male gender identity even though they had been surgically reassigned and raised as girls. Follow-up studies found that almost all of them were attracted to females (i.e. gynophilic). 33 , 50 The outcomes reported for both of these conditions are consistent with the idea that prenatal testosterone programs male-typical sexual orientation in adults. However, effects on sexual orientation were not observed across the board in all individuals with these conditions, indicating that hormones cannot be the only factor involved.

4.2.3 |. Neuroanatomy

Additional evidence that supports a prenatal organisational theory of sexual orientation is derived from the study of anatomical and physiological traits that are known to be sexually dimorphic in humans and are shown to be similar between individuals sharing the same sexual attraction. Neuroanatomical differences based on sexual orientation in human males have been found. LeVay 79 reported that the third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH3) in homosexual men is smaller than in heterosexual men and has a similar size in homosexual men and women. Based on its position and cytoarchitecture, INAH3 resembles the sheep oSDN, which has similar differences in volume and cell density correlated with sexual partner preference. This similarity suggests that a relevant neural circuit is conserved between species. A recent review and meta-analysis of neuroimaging data from human subjects with diverse sexual interests during sexual stimulation also support the conclusion that elements of the anterior and preoptic area of the hypothalamus is part of a core neural circuit for sexual preferences. 80

Other neural and somatic biomarkers of prenatal androgen exposure have also been investigated. McFadden 81 reported that functional properties of the inner ear, measured as otoacoustic emissions (OAEs), and of the auditory brain circuits, measured as auditory evoked potentials (AEPs), differ between the sexes and between heterosexual and homosexual individuals. OAEs and AEPs are usually stronger in heterosexual women than in heterosexual men and are masculinised in lesbians, consistent with the prenatal hormone theory. However, OAEs were not different in homosexual males and AEPs appear to be hyper-masculinised. The second digit to fourth digit (2D:4D) ratio, which is the length of the second digit (index finger) relative to that of the fourth digit (ring finger), is another measure that has been used as a proxy for prenatal androgen exposure. The 2D:4D ratio is generally smaller in men than in women, 82 , 83 although the validity of this measure as a marker influenced by only prenatal androgen exposure has been questioned. 84 Nonetheless, numerous studies have reported that the 2D:4D ratio is also on average smaller in lesbians than in hetero-sexual women, a finding that has been extensively replicated 85 and suggests the testosterone plays a role in female sexual orientation. Similar to OAEs, digit ratios do not appear to be feminised in homosexual men and, similar to AEPs, may even be hyper-masculinised. The lack of evidence for reduced androgen exposure in homosexual men (based on OAEs, AEPs and digit ratios) led Breedlove 85 to speculate that there may be as yet undiscovered brain-specific reductions in androgen responses in male foetuses that grow up to be homosexual. No variations in the human androgen receptor or the aromatase gene were found that relate to variations in sexual orientation. 86 , 87 However, Balthazart and Court 88 provided suggestions for other genes located in the Xq28 region of the X-chromosome that should be explored and it remains possible that expression levels of steroid hormone response pathway genes could be regulated epigenetically (11).

4.2.4 |. Maternal immune response

Homosexual men have, on average, a greater number of older brothers than do heterosexual men, a well-known finding that has been called the fraternal birth order (FBO) effect. 89 Accordingly, the incidence of homosexuality increases by approximately 33% with each older brother. 90 The FBO effect has been confirmed many times, including by independent investigators and in non-Western sample populations. The leading hypothesis to explain this phenomenon posits that some mothers develop antibodies against a Y-linked factor important for male brain development, and that the response increases incrementally with each male gestation leading, in turn, to the alteration of brain structures underlying sexual orientation in later-born boys. In support of the immune hypothesis, Bogaert et al 91 demonstrated recently that mothers of homosexual sons, particularly those with older brothers, have higher antibody titers to neurolignin 4 (NLGN4Y), an extracellular protein involved in synaptic functioning and presumed to play a role in foetal brain development.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The data summarised in the present review suggest that both gender identity and sexual orientation are significantly influenced by events occurring during the early developmental period when the brain is differentiating under the influence of gonadal steroid hormones, genes and maternal factors. However, our current understanding of these factors is far from complete and the results are not always consistent. Animal studies form both the theoretical underpinnings of the prenatal hormone hypothesis and provide causal evidence for the effect of prenatal hormones on sexual orientation as modelled by tests of sexual partner preferences, although they do not translate to gender identity.

Sexual differentiation of the genitals takes place before sexual differentiation of the brain, making it possible that they are not always congruent. Structural and functional differences of hypothalamic nuclei and other brain areas differ in relation to sexual identity and sexual orientation, indicating that these traits develop independently. This may be a result of differing hormone sensitivities and/or separate critical periods, although this remains to be explored. Most findings are consistent with a predisposing influence of hormones or genes, rather than a determining influence. For example, only some people exposed to atypical hormone environments prenatally show altered gender identity or sexual orientation, whereas many do not. Family and twin studies indicate that genes play a role, but no specific candidate genes have been identified. Evidence that relates to the number of older brothers implicates maternal immune responses as a contributing factor for male sexual orientation. All of these mechanisms rely on correlations and our current understanding suffers from many limitations in the data, such as a reliance on retrospective clinical studies of individuals with rare conditions, small study populations sizes, biases in recruiting subjects, too much reliance on studies of male homosexuals, and the assumption that sexuality is easily categorised and binary. Moreover, none of the biological factors identified so far can explain all of the variances in sexual identity or orientation, nor is it known whether or how these factors may interact. Despite these limitations, the existing empirical evidence makes it clear that there is a significant biological contribution to the development of an individual’s sexual identity and sexual orientation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Charles Estill, Robert Shapiro and Fred Stormshak for their thoughtful comments on this review. This work was supported by NIH R01OD011047.

Funding information

This work was supported by NIH R01OD011047 (CER)

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Gender identity development in children and young people: A systematic review of longitudinal studies

Affiliations.

- 1 Research and Development Unit, Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

- 2 Gender Identity Development Service, Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK.

- 3 Division of Psychiatry, University College London, UK.

- 4 Research Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College London, UK.

- PMID: 33827265

- DOI: 10.1177/13591045211002620

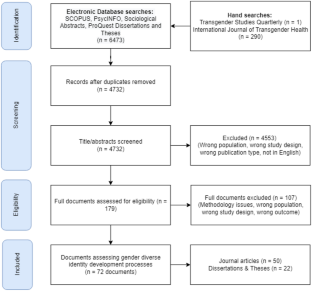

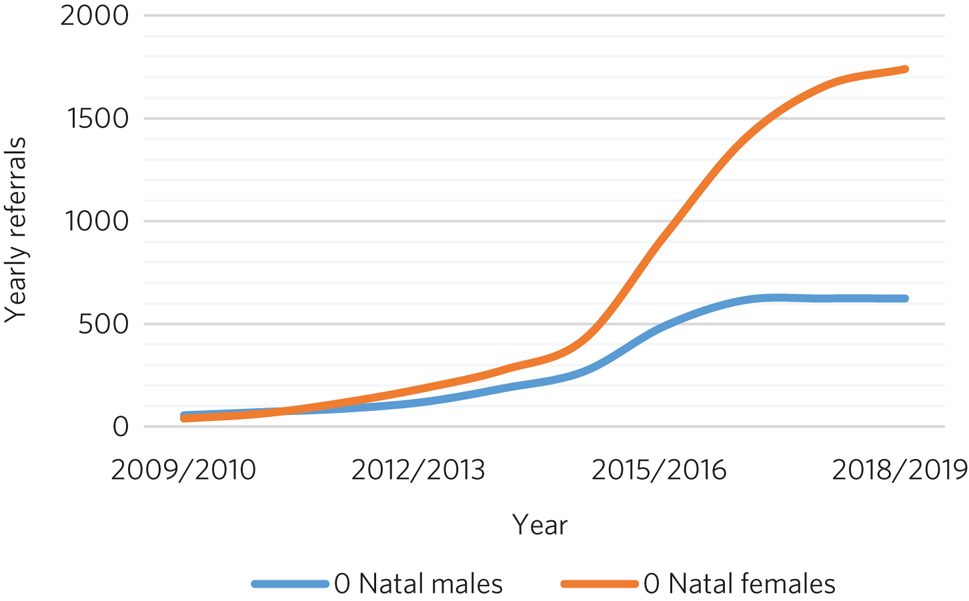

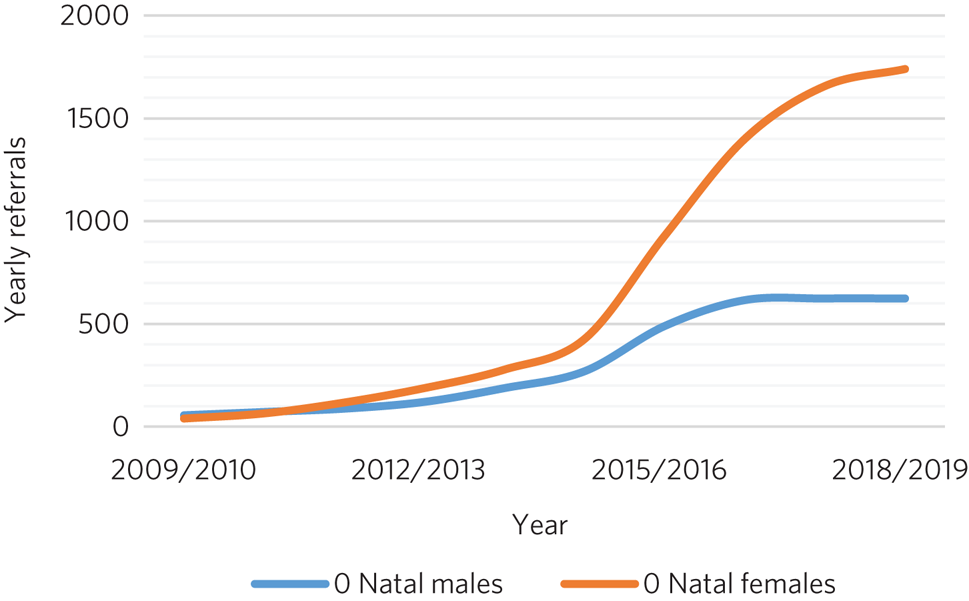

Background: Children are presenting in greater numbers to gender clinics around the world. Prospective longitudinal research is important to better understand outcomes and trajectories for these children. This systematic review aims to identify, describe and critically evaluate longitudinal studies in the field.

Method: Five electronic databases were systematically searched from January 2000 to February 2020. Peer-reviewed articles assessing gender identity and psychosocial outcomes for children and young people (<18 years) with gender diverse identification were included.

Results: Nine articles from seven longitudinal studies were identified. The majority were assessed as being of moderate quality. Four studies were undertaken in the Netherlands, two in North America and one in the UK. The majority of studies had small samples, with only two studies including more than 100 participants and attrition was moderate to high, due to participants lost to follow-up. Outcomes of interest focused predominantly on gender identity over time and emotional and behavioural functioning.

Conclusions: Larger scale and higher quality longitudinal research on gender identity development in children is needed. Some externally funded longitudinal studies are currently in progress internationally. Findings from these studies will enhance understanding of outcomes over time in relation to gender identity development in children and young people.

Keywords: Gender identity; children and young people; gender dysphoria; longitudinal; outcomes; prospective.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Beverage Consumption and Growth, Size, Body Composition, and Risk of Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review [Internet]. Mayer-Davis E, Leidy H, Mattes R, Naimi T, Novotny R, Schneeman B, Kingshipp BJ, Spill M, Cole NC, Bahnfleth CL, Butera G, Terry N, Obbagy J. Mayer-Davis E, et al. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020 Jul. Alexandria (VA): USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review; 2020 Jul. PMID: 35349233 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Longitudinal Outcomes of Gender Identity in Children (LOGIC): study protocol for a retrospective analysis of the characteristics and outcomes of children referred to specialist gender services in the UK and the Netherlands. Kennedy E, Lane C, Stynes H, Ranieri V, Spinner L, Carmichael P, Omar R, Vickerstaff V, Hunter R, Senior R, Butler G, Baron-Cohen S, de Graaf N, Steensma TD, de Vries A, Young B, King M. Kennedy E, et al. BMJ Open. 2021 Nov 10;11(11):e054895. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054895. BMJ Open. 2021. PMID: 34758999 Free PMC article.

- Longitudinal outcomes of gender identity in children (LOGIC): a study protocol for a prospective longitudinal qualitative study of the experiences and well-being of families referred to the UK Gender Identity Development Service. McKay K, Kennedy E, Lane C, Wright T, Young B. McKay K, et al. BMJ Open. 2021 Nov 3;11(11):e047875. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047875. BMJ Open. 2021. PMID: 34732477 Free PMC article.

- Longitudinal Outcomes of Gender Identity in Children (LOGIC): protocol for a prospective longitudinal cohort study of children referred to the UK gender identity development service. Kennedy E, Spinner L, Lane C, Stynes H, Ranieri V, Carmichael P, Omar R, Vickerstaff V, Hunter R, Wright T, Senior R, Butler G, Baron-Cohen S, Young B, King M. Kennedy E, et al. BMJ Open. 2021 Sep 7;11(9):e045628. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045628. BMJ Open. 2021. PMID: 34493504 Free PMC article.

- IMPRoving Outcomes for children exposed to domestic ViolencE (IMPROVE): an evidence synthesis. Howarth E, Moore THM, Welton NJ, Lewis N, Stanley N, MacMillan H, Shaw A, Hester M, Bryden P, Feder G. Howarth E, et al. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2016 Dec. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2016 Dec. PMID: 27977089 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Early Female Transgender Identity after Prenatal Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol: Report from a French National Diethylstilbestrol (DES) Cohort. Gaspari L, Soyer-Gobillard MO, Kerlin S, Paris F, Sultan C. Gaspari L, et al. J Xenobiot. 2024 Jan 12;14(1):166-175. doi: 10.3390/jox14010010. J Xenobiot. 2024. PMID: 38249107 Free PMC article.

- Consistency of gender identity and preferences across time: An exploration among cisgender and transgender children. Hässler T, Glazier JJ, Olson KR. Hässler T, et al. Dev Psychol. 2022 Nov;58(11):2184-2196. doi: 10.1037/dev0001419. Epub 2022 Aug 11. Dev Psychol. 2022. PMID: 35951394 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Diverse Gender Identity Development: A Qualitative Synthesis and Development of a New Contemporary Framework

- Original Article

- Published: 11 December 2023

- Volume 90 , pages 1–18, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Molly Speechley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4056-5404 1 ,

- Jaimee Stuart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4376-1913 2 &

- Kathryn L. Modecki ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9937-9748 3

878 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

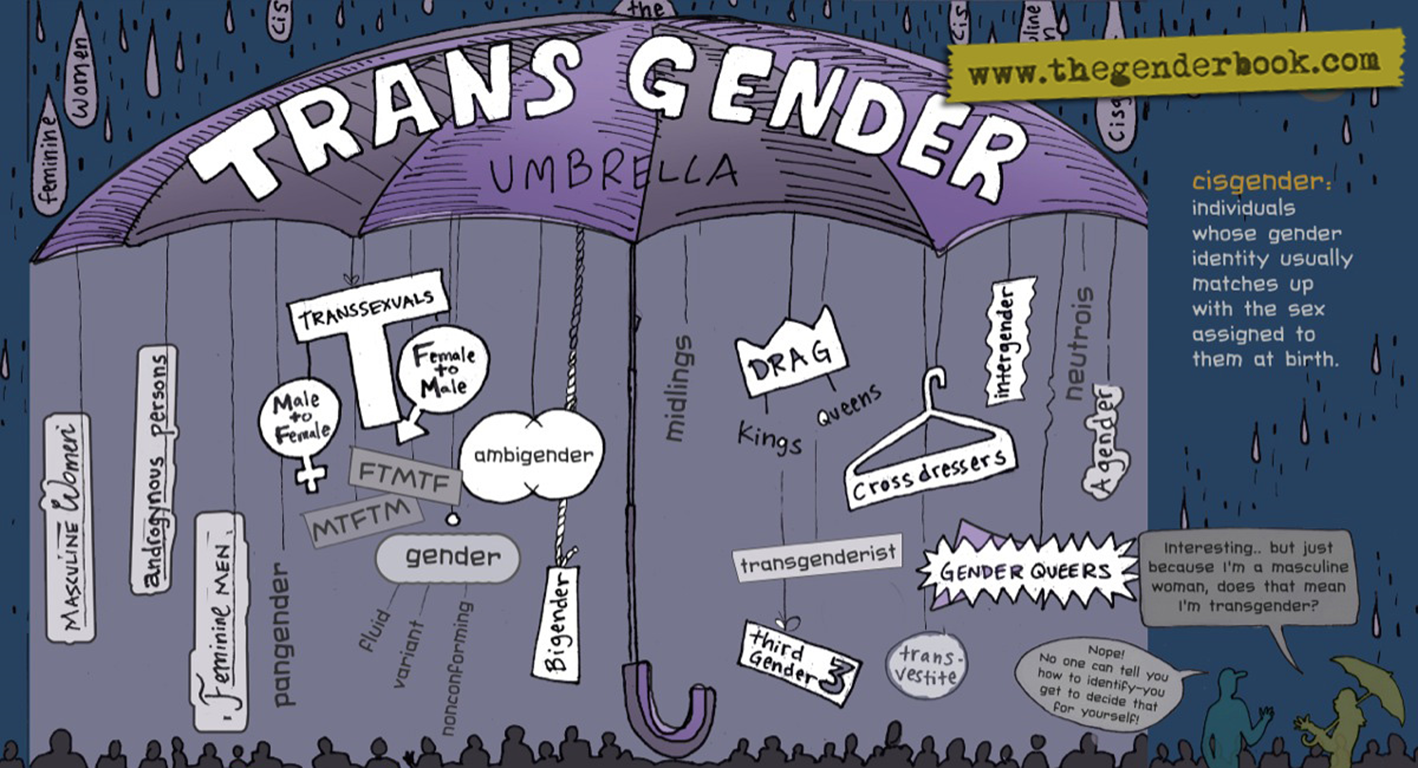

Traditional models of gender identity development for individuals who do not identify with their assigned birth sex have generally treated medical intervention as normative, and non-binary identification as relatively rare. However, changing demographics within gender diverse populations have highlighted the need for an updated framework of gender identity development. To address this gap in the research, this study systematically reviewed the qualitative literature assessing the lived experiences of identity development of over 1,758 gender diverse individuals, across 72 studies. Reflexive thematic analysis of excerpts were synthesised to produce a novel, integrative perspective on identity development, referred to as the Diverse Gender Identity Framework. The framework is inclusive of binary and non-binary identities and characterises the distinctive identity processes individuals undergo across development.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Gender Identity as a Social Developmental Process

“Like a Constantly Flowing River”: Gender Identity Flexibility Among Nonbinary Transgender Individuals

Not by Convention: Working with People on the Sexual and Gender Continuum

Baker, G. (2014). Adult transgender perspectives on identity development [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University].

Balius, A. (2018). “I want to be who I am”: Stories of rejecting binary gender [Master’s thesis, University of South Florida]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2093878022

Beagan, B. L., de Souza, L., Godbout, C., Hamilton, L., MacLeod, J., Paynter, E., & Tobin, A. (2012). “This is the biggest thing you’ll ever do in your life”: Exploring the occupations of transgendered people. Journal of Occupational Science, 19 (3), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2012.659169

Article Google Scholar

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88 (4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354

Bockting, W. O., & Coleman, E. (2007). Developmental stages of the transgender coming out process: Toward an integrated identity. In R. Ettner, S. Monstrey, & A. E. Eyler (Eds.), Principles of transgender medicine and surgery (pp. 185–208). Routledge.

Google Scholar

Boddington, E. (2016). A qualitative exploration of gender identity in young people who identify as neither male nor female [Doctoral dissertation, University of East London]. https://repository.uel.ac.uk/item/85119

Bradford, N. J., & Syed, M. (2019). Transnormativity and transgender identity development: A master narrative approach. Sex Roles, 81 (5–6), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0992-7

Bradford, N. J., Rider, G. N., Catalpa, J. M., Morrow, Q. J., Berg, D. R., Spencer, K. G., & McGuire, J. K. (2019). Creating gender: A thematic analysis of genderqueer narratives. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20 (2–3), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1474516

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide . Sage.

Brown, C., Dashjian, L. T., Acosta, T. J., Mueller, C. T., Kizer, B. E., & Trangsrud, H. B. (2013). Learning from the life experiences of male-to-female transsexuals. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9 (2), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2013.765247

Carlile, A., Butteriss, E., & Sansfaçon, A. P. (2021). “It’s like my kid came back overnight”: Experiences of trans and non-binary young people and their families seeking, finding and engaging with clinical care in England. International Journal of Transgender Health, 22 (4), 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1870188

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Clark, B. A., Veale, J. F., Townsend, M., Frohard-Dourlent, H., & Saewyc, E. (2018). Non-binary youth: Access to gender-affirming primary health care. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19 (2), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1394954

Coleman, E. (1982). Developmental stages of the coming out process. Journal of Homosexuality, 7 (2–3), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v07n02_06

Coleman, E., Radix, A. E., Bouman, W. P., Brown, G. R., de Vries, A. L. C., Deutsch, M. B., Ettner, R., Fraser, L., Goodman, M., Green, J., Hancock, A. B., Johnson, T. W., Karasic, D. H., Knudson, G. A., Leibowitz, S. F., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Monstrey, S. J., Motmans, J., Nahata, L., & Arcelus, J. (2022). Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23 (S1), S1–S259. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2019). CASP qualitative checklist . Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Luyckx, K., & Meeus, W. (2008). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37 (8), 983–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9222-2

Devor, A. H. (2004). Witnessing and mirroring: A fourteen stage model of transsexual identity formation. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy, 8 (1–2), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J236v08n01_05

Downing, J. B. (2013). Trans identity construction: Reconstituting the body, gender, and sex [Doctoral dissertation, Clark University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1334957140

Ehrhardt, A. A., Grisanti, G., & McCauley, E. A. (1979). Female-to-male transsexuals compared to lesbians: Behavioral patterns of childhood and adolescent development. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 8 (6), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541415

Eisenberg, E., & Zervoulis, K. (2020). All flowers bloom differently: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experiences of adult transgender women. Psychology and Sexuality, 11 (1–2), 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2019.1661278

Evans, J. L. (2010). Genderqueer identity and self-perception [Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/745602050

Gagné, P., Tewksbury, R., & McGaughey, D. (1997). Coming out and crossing over identity formation and proclamation in a transgender community. Gender and Society, 11 (4), 478–508. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124397011004006

Goldberg, A. E., & Kuvalanka, K. A. (2018). Navigating identity development and community belonging when “there are only two boxes to check”: An exploratory study of nonbinary trans college students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 15 (2), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2018.1429979

Goodman, M., Adams, N., Corneil, T., Kreukels, B., Motmans, J., & Coleman, E. (2019). Size and distribution of transgender and gender nonconforming populations. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 48 (2), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2019.01.001

Graham, L. F., Crissman, H. P., Tocco, J., Hughes, L. A., Snow, R. C., & Padilla, M. B. (2014). Interpersonal relationships and social support in transitioning narratives of Black transgender women in Detroit. International Journal of Transgenderism, 15 (2), 100–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2014.937042

Gridley, S. J., Crouch, J. M., Evans, Y., Eng, W., Antoon, E., Lyapustina, M., Schimmel-Bristow, A., Woodward, J., Dundon, K., Schaff, R. N., McCarty, C., Ahrens, K., & Breland, D. J. (2016). Youth and caregiver perspectives on barriers to gender-affirming health care for transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59 (3), 254–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017

Gülgöz, S., Glazier, J. J., Enright, E. A., Alonso, D. J., Durwood, L. J., Fast, A. A., Lowe, R., Ji, C., Heer, J., Martin, C. L., & Olson, K. R. (2019). Similarity in transgender and cisgender children’s gender development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116 (49), 24480–24485. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909367116

Hawkins, L. A. (2009). Gender identity development among transgender youth: A qualitative analysis of contributing factors [Doctoral dissertation, Widener University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305248568

Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86 (4), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12127

Kalra, G. (2012). Hijras: The unique transgender culture of India. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health, 5 (2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/17542863.2011.570915

Katz-Wise, S. L., & Budge, S. L. (2015). Cognitive and interpersonal identity processes related to mid-life gender transitioning in transgender women. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 28 (2), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2014.993305

Kennedy, N. (2022). Deferral: The sociology of young trans people’s epiphanies and coming out. Journal of LGBT Youth, 19 (1), 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2020.1816244

Laljer, D. (2017). Comparing media usage of binary and non-binary transgender individuals when discovering and describing gender identity [Master’s thesis, University of North Texas]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2009056791

Lambrou, N. H. (2018). Trans masculine identities: Making meaning in gender and transition [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Wisconsis-Milwaukee]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2108647669

le Roux, N. (2013). Gender variance in childhood/adolescence: Gender identity journeys not involving physical intervention [Doctoral dissertation, University of East London]. https://repository.uel.ac.uk/item/85vvw

Lev, A. I. (2004). Transgender emergence: A developmental process. In T. Trepper (Ed.), Transgender emergence : Therapeutic guidelines for working with gender-variant people and their families (pp. 229–269). The Haworth Clinical Practice Press.

Levitt, H. M. (2019). A psychosocial genealogy of LGBTQ+ gender: An empirically based theory of gender and gender identity cultures. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43 (3), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319834641

Losty, M., & O’Connor, J. (2018). Falling outside of the ‘nice little binary box’: A psychoanalytic exploration of the non-binary gender identity. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 32 (1), 40–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2017.1384933

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3 (5), 551–558.

Matsuno, E., Bricker, N. L., Savarese, E., Mohr, R., & Balsam, K. F. (2022). “The default is just going to be getting misgendered”: Minority stress experiences among nonbinary adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity . https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000607

McCarthy, L. (2003). Off that spectrum entirely: A study of female-bodied transgender-identified individuals [Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305322146

Medico, D., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Zufferey, A., Galantino, G., Bosom, M., & Suerich-Gulick, F. (2020). Pathways to gender affirmation in trans youth: A qualitative and participative study with youth and their parents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25 (4), 1002–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104520938427

Money, J., & Primrose, C. (1968). Sexual dimorphism and dissociation in the psychology of male transsexuals. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 147 (5), 472–486. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-196811000-00004

Morgan, S. W., & Stevens, P. E. (2008). Transgender identity development as represented by a group of female-to-male transgendered adults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29 (6), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840802048782

Mullen, G., & Moane, G. (2013). A qualitative exploration of transgender identity affirmation at the personal, interpersonal, and sociocultural levels. International Journal of Transgenderism, 14 (3), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2013.824847

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Oakley, A. (2016). Disturbing hegemonic discourse: Nonbinary gender and sexual orientation labeling on Tumblr. Social Media and Society, 2 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116664217

Opromalla, J. A. (2019). Transgender young adults’ negotiation of gender consciousness in relation to others’ behaviors and attitudes [Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2239312970

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5 (1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Patel, E. (2019). Understanding gender identity development in gender variant birth-assigned female adolescents with autism spectrum conditions [Doctoral dissertation, University College London]. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10083597/

Penklis, H. S. (2020). “Celebrated, not tolerated”: How transgender and nonbinary individuals navigate the social world [Master’s thesis, The University of Texas at El Paso]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2424094395

Pollock, L., & Eyre, S. L. (2012). Growth into manhood: Identity development among female-to-male transgender youth. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 14 (2), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.636072

Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Medico, D., Suerich-Gulick, F., & Temple Newhook, J. (2020). “I knew that I wasn’t cis, I knew that, but I didn’t know exactly”: Gender identity development, expression and affirmation in youth who access gender affirming medical care. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21 (3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1756551

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo (March 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Rankin, S., & Beemyn, G. (2012). Beyond a binary: The lives of gender-nonconforming youth. About Campus: Enriching the Student Learning Experience, 17 (4), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21086

Rood, B. A., Reisner, S. L., Puckett, J. A., Surace, F. I., Berman, A. K., & Pantalone, D. W. (2017). Internalized transphobia: Exploring perceptions of social messages in transgender and gender-nonconforming adults. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18 (4), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1329048

Sakai, C. (2003). Identity development in female-to-male transsexuals: A qualitative study [Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305213596

Schimmel-Bristow, A., Haley, S. G., Crouch, J. M., Evans, Y. N., Ahrens, K. R., McCarty, C. A., & Inwards-Breland, D. J. (2018). Youth and caregiver experiences of gender identity transition: A qualitative study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5 (2), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000269

Schneider, J., Page, J., & van Nes, F. (2019). “Now I feel much better than in my previous life”: Narratives of occupational transitions in young transgender adults. Journal of Occupational Science, 26 (2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2018.1550726

Schulz, S. L. (2012). Gender identity: Pending? Identity development and health care experiences of transmasculine/genderqueer identified individuals [Doctoral dissertation, University of California]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1322090378

Stryker, S. (2017). Transgender history: The roots of today’s revolution (Revised) . Seal Press.

Tan, S. (2019). Lived experience of Asian transgender youth in Canada: An intersectional framework [Doctoral dissertation, Adler University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2312892674

Valle, J. (2020). A qualitative study of the trans fem community: Exploring trans identity formation, familial support, and relationships with food [Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2476835074

Ward, K. (2019). Building an identity despite discrimination: A linguistic analysis of the lived experiences of gender variant people in North East England [Doctoral dissertation, University of Sunderland]. https://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/10874/%0A

Weisgram, E. S. (2016). The cognitive construction of gender stereotypes: Evidence for the dual pathways model of gender differentiation. Sex Roles, 75 (7–8), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0624-z

Wright, K. A. (2011). Transgender identity formation [Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1411944798

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues as part of the 2021 Spring Grand-in-Aid program; and an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship, granted to the first author.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia

Molly Speechley

United Nations University, Macao, China

Jaimee Stuart

Centre for Mental Health, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia

Kathryn L. Modecki

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: Molly Speechley, Jaimee Stuart, Kathryn Modecki; Methodology: Molly Speechley, Jaimee Stuart; Formal analysis and investigation: Molly Speechley; Writing—original draft preparation: Molly Speechley; Writing—review and editing: Molly Speechley, Jaimee Stuart, Kathryn Modecki; Funding acquisition: Molly Speechley, Kathryn Modecki; Supervision: Jaimee Stuart, Kathryn Modecki.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Molly Speechley .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Human and Animal Ethics

Consent for publication.

All authors consent to publication of the manuscript.

Availability of supporting data

All data analysed during this study are included in its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 116 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Speechley, M., Stuart, J. & Modecki, K.L. Diverse Gender Identity Development: A Qualitative Synthesis and Development of a New Contemporary Framework. Sex Roles 90 , 1–18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-023-01438-x

Download citation

Accepted : 26 October 2023

Published : 11 December 2023

Issue Date : January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-023-01438-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gender diversity

- Developmental experiences

- Identity development

- Non-binary identity

- Qualitative review

- Transgender

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 September 2020

Fluidity of gender identity induced by illusory body-sex change

- Pawel Tacikowski 1 , 2 ,

- Jens Fust ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4706-092X 1 , 3 &

- H. Henrik Ehrsson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2333-345X 1

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 14385 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

34k Accesses

31 Citations

144 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Human behaviour

Gender identity is a collection of thoughts and feelings about one’s own gender, which may or may not correspond to the sex assigned at birth. How this sense is linked to the perception of one’s own masculine or feminine body remains unclear. Here, in a series of three behavioral experiments conducted on a large group of control volunteers (N = 140), we show that a perceptual illusion of having the opposite-sex body is associated with a shift toward a more balanced identification with both genders and less gender-stereotypical beliefs about own personality characteristics, as indicated by subjective reports and implicit behavioral measures. These findings demonstrate that the ongoing perception of one’s own body affects the sense of one’s own gender in a dynamic, robust, and automatic manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Daily gender expression is associated with psychological adjustment for some people, but mainly men

Male recognition bias in sex assignment based on visual stimuli

Male sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and neural activity during mental rotations: an fMRI study

Introduction.

Gender identity is a collection of thoughts and feelings about one’s own gender, which may or may not correspond to the sex assigned at birth 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 . This multifaceted, subjective sense of being male, female, both, or neither occurs in our conscious self-awareness, but the associated perceptions and beliefs can also be largely implicit 3 , 4 , 5 . In the past, gender identity was conceptualized as a male–female dichotomy; however, current theories consistently postulate that gender identity is a spectrum of associations with both genders 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . There is also a general consensus in the field that gender identity is determined by multiple factors, such as person’s genes, hormones, patterns of behaviors, or social interactions 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ; and that the sense of own gender (e.g., “I’m male”) is closely linked to one’s beliefs about males and females in general (e.g., “males are competitive”), as well as to the associated beliefs about own personality (“I am competitive”) 1 , 3 , 6 . The specific content of such beliefs and their strength contribute to what it means for a given person to be male or female in a given sociocultural context, which in some cases hinders the realization of one’s full personal or professional potential. Although gender identity has a profound impact on our lives, little is known about how this sense is formed or maintained. A better understanding of the neurocognitive mechanisms of gender identity is also important in the context of gender dysphoria (DSM-5 9 ; gender incongruence ICD-11 10 ), which is characterized by the prolonged and clinically relevant distress that some transgender individuals experience due to inconsistency between their sex assigned at birth and their subjective sense of gender.

Various observations suggest that gender identity and the perception of one’s own body are tightly connected. For example, people with gender dysphoria (see above) often avoid looking in the mirror, hide their bodies under loose-fitting clothes, and seek hormonal and/or surgical procedures to adjust their physical appearance to meet their subjective sense of own gender 6 , 11 , 12 . Moreover, among individuals whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth, mastectomy and androgen deprivation cancer therapies, which both involve changes to one’s feminine or masculine bodily characteristics, are often related to a gender identity crisis 13 , 14 . There are also data suggesting that the mental representation of one’s own body is altered in transgender individuals 15 and that the brain regions involved in this representation are anatomically and functionally different in this group compared to controls 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 . However, the link between own body perception and gender identity remains poorly understood from a behavioral experimental perspective, and we do not know whether, and if so how, the perceived sex of own body influences the sense of own gender in nontransgender individuals.

The full-body ownership illusion 24 is a powerful experimental tool for manipulating the perception of one’s own body 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 . During this illusion, the participants wear head-mounted displays (HMDs) and observe a stranger’s body from a first-person perspective. The stranger’s body is continuously stroked with a stick or a brush, and the experimenter applies synchronous touches on the corresponding parts of the participant’s body, which is out of view. Synchronous visuotactile stimulation induces a feeling that the stranger’s body is one’s own, whereas asynchronous stimulation breaks the illusion and serves as a well-matched control condition 24 , 31 , 32 , 33 . The full-body ownership illusion, similar to the rubber hand illusion involving a single limb 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , occurs when visual, tactile, proprioceptive, and other sensory signals from the body are combined at the central level into a coherent multisensory representation of one’s own body 24 , 25 , 26 , 30 . Body ownership illusions involving limbs 37 and full bodies 31 , 33 , 38 are related to increased neural activity in regions of the frontal and parietal association cortices that are related to multisensory integration, such as the premotor and intraparietal cortices. Because these brain regions contain trimodal neurons that integrate visual, tactile, and proprioceptive signals and because body illusions closely follow the temporal and spatial constraints of multisensory integration, it has been proposed that combining bodily signals from different modalities is a key mechanism for attributing ownership to our bodies 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 . The full-body illusion has been replicated in numerous studies 24 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , even with bodies of a sex opposite to that of the participants 24 , 43 , but the cognitive consequences of this transient physical sex change on gender identity have not been assessed.

Here, we conducted three within-subject behavioral experiments on a total of one hundred forty naïve control volunteers to investigate a possible dynamic relationship between the perception of own body and the sense of own gender. In all three experiments, we induced the “body-sex-change illusion”, which is analogous to the standard full-body illusion (see earlier), but in the HMDs, the participants observe the opposite-sex stranger’s body (Movies S1 and S2). Thus, we aimed to experimentally manipulate how the participants perceived the secondary sex characteristics of their own bodies to measure what outcome this manipulation has on different aspects of gender identity. Specifically, in Experiment I, we asked the participants to rate how masculine or feminine they felt after the body-sex-change illusion to assess the subjective and conscious facets of gender identity. Explicit methods such as the one above provide information about participants’ phenomenological experience, but ideally, they should be combined with objective tests to provide more conclusive results. Therefore, in Experiment II, we used a well-controlled behavioral method—the Implicit Association Test (IAT)—to measure the cognitive and implicit aspects of gender identity; this test is largely immune to conscious strategies 46 and has been validated for gender identity research in control 47 , 48 as well as in transgender individuals 48 . Finally, in Experiment III, we tested whether the perception of own body affects gender-related beliefs about own personality (see earlier) by asking the participants to rate after the illusion how much different traits, stereotypically related to males and females, pertain to their own personality. Applying such different measurements aimed to capture the multifaceted character of the sense of own gender (see earlier), while using continuous scales in all experiments addressed gender identity as a spectrum (see earlier). We hypothesized that if own body perception dynamically shapes gender identity, then even a brief transformation of one’s own perceived physical sex during the body-sex-change illusion should shift different aspects of gender identity toward the opposite gender.

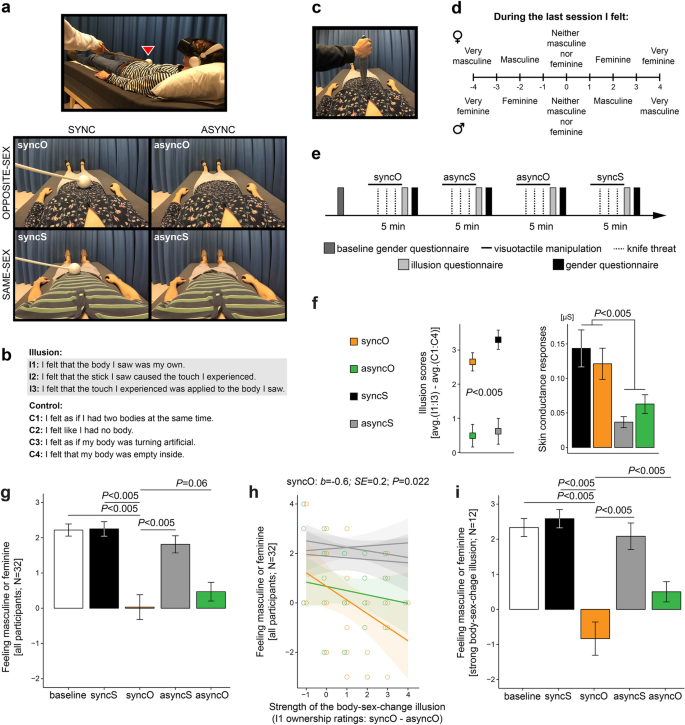

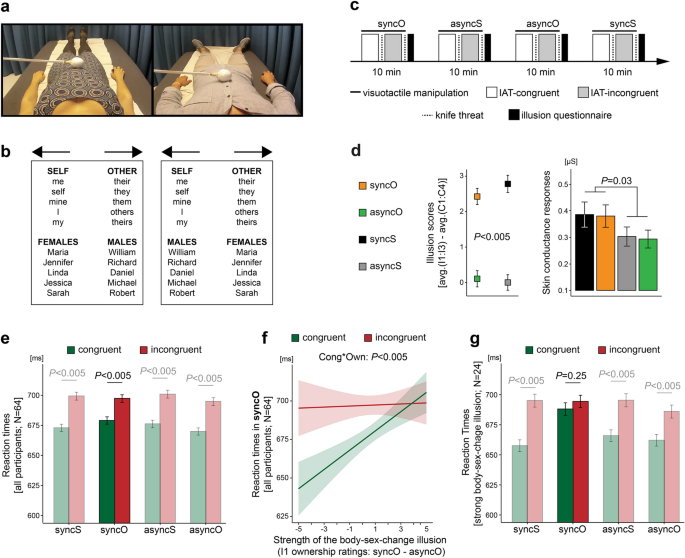

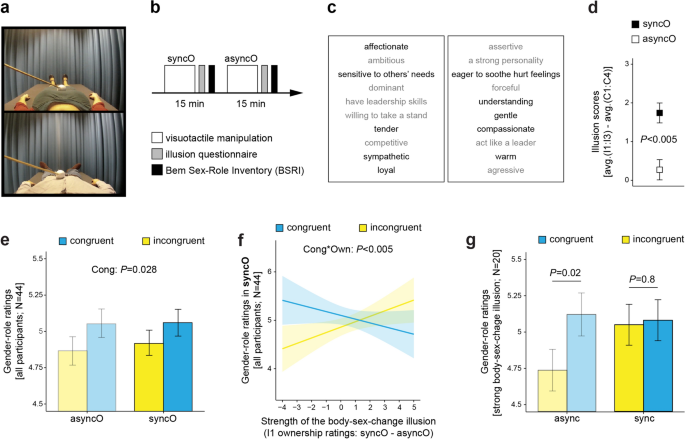

Experiment I tested whether the perception of one’s own body dynamically shapes one’s subjective feeling of masculinity/femininity. The experiment comprised a two-by-two factorial design with four conditions (Fig. 1 a): “synchronous opposite sex” (syncO), “synchronous same sex” (syncS), “asynchronous opposite sex” (asyncO), and “asynchronous same sex” (asyncS). This design allowed us to manipulate the sex-related characteristics of the perceived bodily self in the body-sex-change illusion condition (syncO) while controlling for potential confounding factors related to experiencing a full-body ownership illusion itself (syncS) or cognitive biases due to simply looking at a male or female body (asyncS, asyncO). We measured the illusion psychometrically by asking the participants to rate their subjective experience of owning the stranger’s body (Fig. 1 b) and objectively by recording the participants’ physiological fear reactions (skin conductance responses) when the stranger’s body was physically threatened with a knife (Fig. 1 c). Both of these illusion measures should be higher during the synchronous than during the asynchronous conditions 24 , 32 , 38 , 39 , 42 . Importantly, before experiencing any body perception manipulation (baseline) and after every full-body illusion condition, the participants rated how masculine or feminine they felt (Fig. 1 d,e).

Perceptual illusion of having the opposite-sex body modulated the subjective experience of feeling masculine or feminine (Experiment I). ( a ) The participants (N = 32; 15 females) lay on a bed and wore a head-mounted display in which a body of an unknown male or female was shown from a first-person perspective (the participant’s real body was out of view). Video frames illustrate all four conditions for a male participant (top picture). For a female participant, the videos from the lower and upper rows would be swapped. In the synchronous conditions, touches applied to the participant and touches applied to the stranger’s body were matched (see the red triangle), whereas in the asynchronous conditions, touches applied to the participants were delayed by 1 s. We expected to induce the body-sex-change illusion specifically in the syncO condition, and the other conditions served as controls. ( b ) After each condition, the participants rated illusion (I1:I3) and control (C1:C4) statements on a 7-point scale (− 3—“strongly disagree”; + 3— “strongly agree”). The illusion statements assessed the feeling that the stranger’s body is one’s own, whereas the control statements controlled for any potential effects of suggestibility or task compliance. ( c ) Genuine ownership of the stranger’s body should be associated with increased physiological stress responses of the participant when the stranger’s body is physically threatened. Thus, we measured the participants’ skin conductance responses elicited by brief “knife threat” events that occurred in the videos. ( d ) Before the experiment (baseline) and after each condition, the participants rated how feminine or masculine they felt. The upper row shows scale assignment for female participants and the lower row for males. ( e ) The order of conditions was counterbalanced across the participants, and the whole experiment lasted ~ 30 min. ( f ) The illusion ratings and the magnitude of skin conductance responses were significantly higher in the synchronous than in the asynchronous conditions, which shows that the full-body ownership illusion was elicited as expected. ( g ) During syncO, the female participants indicated feeling less feminine, and the male participants indicated feeling less masculine than during other conditions. ( h ) Strong illusory ownership of the opposite-sex body was related to a significant shift toward the opposite gender, specifically in syncO. For clarity of display, only ratings from syncO and asyncO are shown; syncS, asyncS, and baseline are colored in gray for comparison. ( i ) The participants who experienced a strong body-sex-change illusion (above-median I1 ownership ratings: syncO–asyncO; N = 12) indicated feeling more masculine (females) or more feminine (males) during syncO than during other conditions. Plots show means ± SE.

The full-body ownership illusion was induced as expected, that is, “illusion scores” [illusion questionnaire ratings: (I1 + I2 + I3)/3 + (C1 + C2 + C3 + C4)/4] were higher in the synchronous than in the asynchronous conditions, and knife threats during the synchronous conditions triggered stronger skin conductance responses than knife threats during the asynchronous conditions (Fig. 1 f; Table S2 ; main effect of synchrony; illusion scores: F 1,32 = 64.48; P < 0.005; skin conductance: F 1,27 = 10.98; P < 0.005; two-sided; N = 32). With regard to our main hypothesis, we found that during syncO, female participants indicated feeling significantly less feminine and male participants significantly less masculine than during the baseline, syncS, and asyncS control conditions; the difference between syncO and asyncO showed a significant trend in the hypothesized direction (Fig. 1 g; Tables S2 and S3 ). Importantly, the shift toward the opposite gender, specifically in the syncO condition, was enhanced by the illusory ownership of the opposite-sex body (Fig. 1 h; Tables S2 and S3 ; synchrony × body × ownership: F 1,32 = 8.05; P = 0.008; main effect of ownership in syncO: b = − 0.6; SE = 0.2; t 30 = − 2.29; P = 0.022; two-sided; N = 32). Please note that “ownership” in the analysis above corresponds to I1 questionnaire ratings: syncO—asyncO (one value per participant). Moreover, we found that the participants who experienced a strong body-sex-change illusion (N = 12; median-split; see “ Materials and methods ”) indicated feeling more like the opposite gender in syncO compared to the other conditions (Fig. 1 i; Tables S2 and S3 ). Overall, Experiment I shows that the ongoing perception of one’s own body dynamically updates one’s subjective feelings of masculinity or femininity.

Experiment II tested whether the perceived sex of one’s own body also modulates implicit associations between oneself and gender categories. This experiment had the same two-by-two factorial design as Experiment I (Fig. 1 a), but this time, gender identity was measured with the IAT 47 , 48 . During this test, the participants heard words belonging to four semantic categories ( male , female , self , or other ) and sorted these words into just two response categories. In one block, the participants responded with the same key to words from the self and female categories, which made this block congruent for females and incongruent for males. In the other block, the participants responded with the same key to words from the self and male categories, which made this block incongruent for females and congruent for males (Fig. 2 b). Faster responses in the congruent block than in the incongruent block (i.e., congruent block being cognitively less demanding) indicate that a given person associates with the gender that is consistent with his/her sex. In turn, longer reaction times in the congruent block suggest an inclination toward the opposite gender, whereas similar responses in both blocks suggest a balanced gender identity. Thus, the IAT provides a fine-grained behavioral proxy of where a person is located on a gender identity spectrum (see “ Introduction ”). The participants performed the IAT four times, once during each condition, which allowed us to track changes in implicit gender identification across different embodiment contexts (Fig. 2 c).

The body-sex-change illusion balanced implicit associations between the self and both genders (Experiment II). ( a ) This experiment (N = 64; 32 females) comprised the same four conditions as Experiment I (Fig. 1 a), but we used recordings of a different male and female body to enhance the generalizability of our findings. ( b ) The left panel is a schematic representation of the congruent IAT block for the female participants (incongruent for males), as words from the self and female categories are assigned to the same response category (left arrow). The right panel shows the IAT block that is incongruent for the female participants and congruent for males. Please note that exactly the same words are used in both blocks, only the instructions (key assignment) are different. ( c ) During each condition, the participants completed one full IAT (two blocks). The condition order and block order were counterbalanced across participants. The whole experiment lasted ~ 60 min. ( d ) The body-sex-change illusion was successfully induced, as shown by questionnaire data and the magnitude of threat-evoked skin conductance responses. ( e ) In all conditions, reaction times were significantly shorter in the congruent than in the incongruent IAT blocks, which shows that it was generally easier for the participants to associate themselves with the gender consistent with their sex. ( f ) Strong illusory ownership of the opposite-sex body was related to the balancing of implicit associations between the self and both genders, specifically in syncO. For clarity of display, individual data points are not shown (n = 7,290). ( g ) The participants who experienced a strong body-sex-change illusion (above-median I1 ownership ratings: syncO–asyncO; N = 24) responded similarly quickly in the incongruent and congruent IAT blocks during syncO. Bar plots show means ± SE.

The body-sex-change illusion was also successfully induced in Experiment II, as demonstrated by the questionnaire and skin conductance data (Fig. 2 d; Table S4 ; main effect of synchrony; illusion scores: F 1,64 = 125.65; P < 0.005; skin conductance: F 1,60 = 4.97; P = 0.03; two-sided; N = 64). In all conditions, it was easier for the participants to associate themselves with the gender consistent with their sex, as indicated by shorter reaction times in the congruent than in the incongruent blocks (Fig. 2 e; Tables S4 and S5 ). More importantly, however, strong illusory ownership of the opposite-sex body was related to a reduced difference between the incongruent and congruent blocks specifically in syncO, which shows that the illusion balanced the strength of implicit associations between the self and both genders (Fig. 2 f; Table S4 ; synchrony × body × congruence × ownership: F 1,28878 = 17.03; P < 0.005; congruence × ownership in syncO: F 1,7207 = 9.37; P < 0.005; two-sided; N = 64). Furthermore, the participants who experienced strong illusory ownership of the opposite-sex body (N = 24; median-split; see “ Materials and methods ”) had similar reaction times in the congruent and incongruent IAT blocks during syncO (Fig. 2 g; Tables S4 and S5 ). Thus, the main finding of Experiment II is that the moment-to-moment perception of one’s own body balances the strength of implicit associations between the self and both genders.