An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Making Fashion Sustainable: Waste and Collective Responsibility

Debbie moorhouse.

1 Department of Fashion & Textiles, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, UK

Fashion is a growing industry, but the demand for cheap, fast fashion has a high environmental footprint. Some brands lead the way by innovating to reduce waste, improve recycling, and encourage upcycling. But if we are to make fashion more sustainable, consumers and industry must work together.

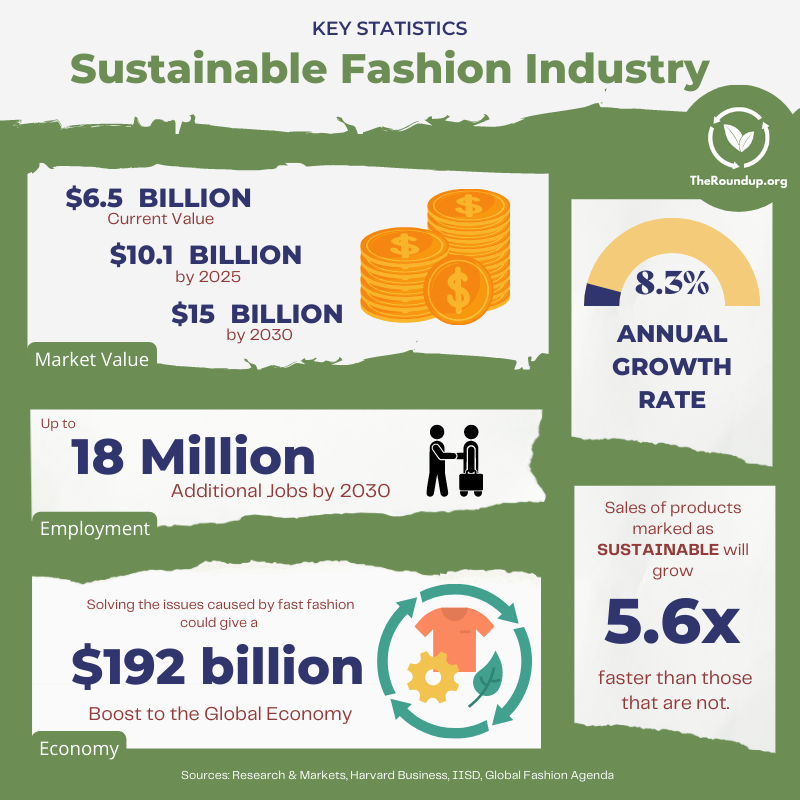

As the demand for apparel and shoes has increased worldwide, the fashion industry has experienced substantial growth. In the last 15 years, clothing production has doubled, accounting for 60% of all textile production. 1 One particular trend driving this increase is the emergence of fast fashion. The newest trends in celebrity culture and bespoke fashion shows rapidly become available from affordable retailers. In recent years, a designer’s fashion calendar can consist of up to five collections per year, and in the mass-produced market, new stock is being produced every 2 weeks. As with many commodities today, mass production and consumption are often accompanied by mass wastage, and fashion is no different.

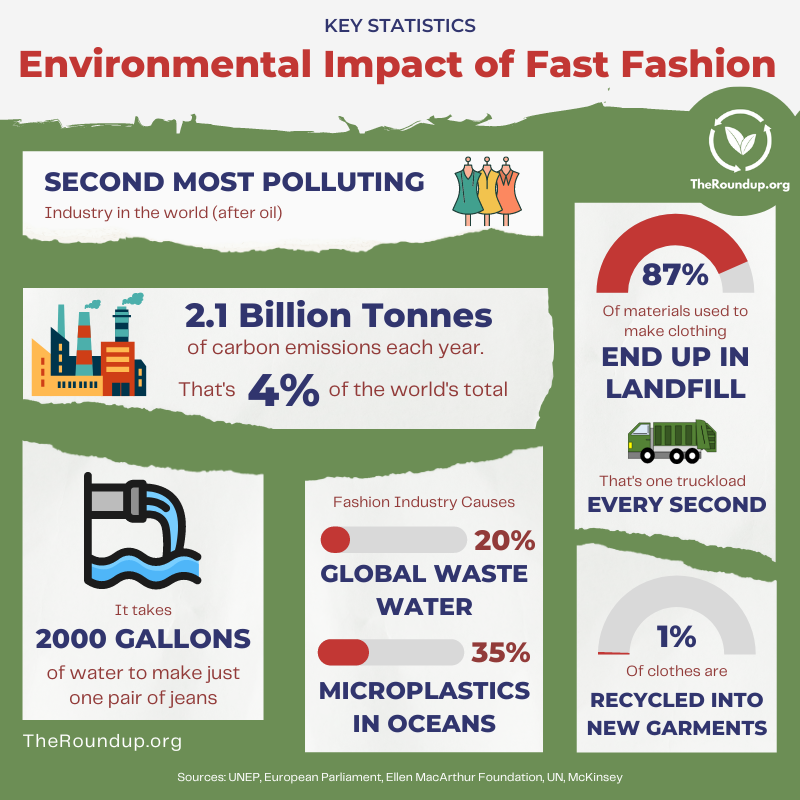

In fashion, trends rapidly change, and a drive to buy the latest style can leave many items with a short lifespan and consigned to the waste bin. Given that 73% of clothing ends up in landfills and less than 1% is recycled into new clothing, there are significant costs with regard to not only irreplaceable resources but also the economy via landfilling clothing. At present, it is estimated that £140 million worth of clothing is sent to landfills in the UK each year. 2 Although a significant proportion of recycled fibers are downgraded into insulation materials, industrial wipes, and stuffing, they still constitute only 12% of total discarded material.

The world is increasingly worried about the environmental and social costs of fashion, particularly items that have short lifespans. Mass-produced fashion is often manufactured where labor is cheap, but working conditions can be poor. Sweatshops can even be found in countries with stricter regulations. The transport of products from places of manufacture to points of sale contributes to the textile industry’s rising carbon footprint; 1.2 billion metric tons of CO 2 were reportedly emitted in 2015. 1 Textile dyeing and finishing are thought to contribute to 20% of the world’s water pollution, 3 and microfiber emission during washing amounts to half a million metric tons of plastic pollution annually. 4 Fashion’s water footprint is particularly problematic. Water is used throughout clothing production, including in the growth of crops such as cotton and in the weaving, manufacturing, washing, and dyeing processes. The production of denim apparel alone uses over 5,000 L of water 5 for a single pair of jeans. When you add this to consumer overuse of water, chemicals, and energy in the laundry process and the ultimate discard to landfills or incineration, the environmental impact becomes extremely high.

As demand for fast fashion continues to grow, so too does the industry’s environmental footprint. Negative impacts are starkly evidenced throughout the entire supply chain—from the growth of raw materials to the disposal of scarcely used garments. As awareness of the darker side of fashion grows, so too does demand for change—not just from regulatory bodies and global action groups but also from individual consumers. People want ethical garments. Sustainability and style. But achieving this is complicated.

Demand for Sustainable Fashion

Historically, sustainable brands were sought by a smaller consumer base and were typically part of the stereotype “hippy” style. But in recent years, sustainable fashion has become more mainstream among both designers and consumers, and the aesthetic appeal has evolved to become more desirable to a wider audience. As a result, the consumer need not only buy into the ethics of the brand but also purchase a desirable, contemporary garment.

But the difficulty for the fashion industry lies in addressing all sustainability and ethical issues while remaining economically sustainable and future facing. Sustainable and ethical brands must take into account fairer wages, better working conditions, more sustainably produced materials, and a construction quality that is built for longevity, all of which ultimately increase the cost of the final product. The consumer often wrestles with many different considerations when making a purchase; some of these conflict with each other and can lead the consumer to prioritize the monetary cost.

Many buyers who place sustainability over fashion but cannot afford the higher cost of sustainable garments will often forsake the latest styles and trends to buy second hand. However, fashion and second-hand clothing need not be mutually exclusive, as can be seen by the growing trend of acquiring luxury vintage pieces. Vintage clothing is in direct contrast to the whole idea of “fast fashion” and is sought after as a way to express individuality with the added value of saving something precious from landfills. Where vintage might have once been purchased at an exclusive auction, now many online sources trade in vintage pieces. Celebrities, fashion influencers, and designers have all bought into this vintage trend, making it a very desirable pre-owned, pre-loved purchase. 6 In effect, the consumer mindset is changing such that vintage clothing (as a timeless, more considered purchase) is more desirable than new products because of its uniqueness, a virtue that stands against the standardization of mass-market production.

Making Fashion Circular

In an ideal system, the life cycle of a garment would be a series of circles such that the garment would continually move to the next life—redesigned, reinvented, and never discarded—eliminating the concept of waste. Although vintage is growing in popularity, this is only one component of a circular fashion industry, and the reality is that the linear system of “take, make, dispose,” with all its ethical and environmental problems, continues to persist.

Achieving sustainability in the production of garments represents a huge and complex challenge. It is often quoted that “more than 80% of the environmental impact of a product is determined at the design stage,” 7 meaning that designers are now being looked upon to solve the problem. But the responsibility should not solely lie with the designer; it should involve all stakeholders along the supply chain. Designers develop the concept, but the fashion industry also involves pattern cutters and garment technologists, as well as the manufacturers: both producers of textiles and factories where garment construction takes place. And finally, the consumer should not only dispose, reuse, or upcycle garments appropriately but also wash and care for the garment in a way that both is sustainable and ensures longevity of the item. These stakeholders must all work together to achieve a more sustainable supply chain.

The challenge of sustainability is particularly pertinent to denim, which, as already mentioned, is one of the more problematic fashion items. Traditionally an expression of individualism and freedom, denim jeans are produced globally at 1.7 billion pairs per year 8 through mass-market channels and mid-tier and premium designer levels, and this is set to rise. In the face of growing demand, some denim specialists are looking for ways to make their products more sustainable.

Reuse and recycling can play a role here, and designers and brands such as Levi Strauss & Co. and Mud Jeans are taking responsibility for the future life of their garments. They are offering take-back services, mending services, and possibilities for recycling to new fibers at end of life. Many brands have likewise embraced vintage fashion. Levi’s “Authorized Vintage” line, which includes upcycled, pre-worn vintage pieces, not only exemplifies conscious consumption but also makes this vintage trend more sought after by the consumer because of its iconic status. All material is sourced from the company’s own archive, and all redesigns “are a chance to relive our treasured history.” 9

Mud Jeans in particular is working toward a circular business model by taking a more considered, “seasonless” approach to their collections by instead focusing on longevity and pieces that transcend seasons. In addition, they offer a lease service where jeans can be returned for a different style and a return service at end of life for recycling into new fiber. The different elements that make up a garment, such as the base fabrics (denim in the case of Mud jeans) and fastenings, are limited so the company can avoid overstocking and reduce deadstock. 10 This model of keeping base materials to a minimum has been adopted by brands that don’t specialize in denim, such as Adidas’s production of a recyclable trainer made from virgin thermoplastic polyurethane. 11 The challenge with garments, as with footwear, is that they are made up of many different materials that are difficult to separate and sort for recycling. These business models have a long way to go to be truly circular, but some companies are paving the way forward, and their transparency is highly valuable to other companies that wish to follow suit.

Once a product is purchased, its future is in the hands of the consumer, and not all are aware of the recycling options available to them or that how they care for their garments can have environmental impacts. Companies are helping to inform them. In 2009, Levi Strauss & Co. introduced “Care Tag for Our Planet,” which gives straightforward washing instructions to save water and energy and guidance on how to donate the garment when it is no longer needed. Mud Jeans follows a similar process by highlighting the need to break the habit of regular unnecessary washing and even suggesting “air washing.” 10

At the same time, designers are moving away from the traditional seasonal production cycle and into a more seasonless calendar. In light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele, has announced (May 2020) that the Italian brand will end the traditional five fashion shows per year and will “hold shows just twice a year instead to reduce waste.” 12 This is a brave decision because it goes against the practice whereby designers were pressured for decades to produce more collections per year, but the hope is that it will be quickly followed by more brands and designers.

Transparency

The discussion around sustainable fashion practices has led to a growing demand from consumers for transparency in the supply chain and life cycle of fashion garments. Consumers want to be informed. They are skeptical of media hype and “greenwashing” by fast-fashion companies wanting to make their brand appear responsible. They want to know the origin of the product and its environmental and social impact.

Some companies are responding by seeking a better understanding of the environmental impacts of their products. In 2015, denim specializer Levi Strauss & Co. extensively analyzed the garment life cycle to consider the environmental impact of a core set of products from its range. The areas highlighted for greatest water usage and negative environmental impact were textile production and consumer laundry care; the consumer phase alone consumed 37% of energy, 13 fiber and textile production accounted for 36% of energy usage, and the remaining 27% was spent on garment production, transport, logistics, and packaging. 14 This life-cycle analysis has led to innovation in waterless finishing processes that use 96% less water than traditional fabric finishing. 15 As noted previously, transparency here also inspires the wider industry to do likewise. Other companies have also introduced dyeing processes that need much less water, and much work is focused on improving textile recycling.

But this discussion does not just apply to production. Some high-street brands are using a “take back” scheme whereby customers are invited to bring back unwanted clothing either for a discount on future purchases or as a way to offload unwanted items of clothing. Not only might this encourage consumers to buy more without feeling guilty, but the ultimate destination of these returned garments can also be unclear. Without further transparency, a consumer cannot make fully informed decisions about the end-of-life fate of their garments.

Collective Responsibility

The buck should not be passed when it comes to sustainability; it is about collective responsibility. Professionals in the fashion industry often feel that it is in the hands of the consumer—they have the buying power, and their choices determine how the industry reacts. One train of thought is that the consumer needs to buy less and that the fashion retail industry can’t be asked to sell less. However, if a sustainable life cycle is to be achieved, stakeholders within the cycle must also be accountable, and there are growing demands for the fashion industry to be regulated.

With the global demand for new clothing, there is an urgent need to discover new materials and to find new markets for used clothing. At present, garments that last longer reduce production and processing impacts, and designers and brands can make efforts in the reuse and recycling of clothing. But environmental impact will remain high if large quantities of new clothing continue to be bought.

If we want a future sustainable fashion industry, both consumers and industry professionals must engage. Although greater transparency and sustainability are being pursued and certain brands are leading the way, the overconsumption of clothing is so established in society that it is difficult to say how this can be reversed or slowed. Moreover, millions of livelihoods depend on this constant cycle of fashion production. Methods in the recycling, upcycling, reuse, and remanufacture of apparel and textiles are short-term gains, and the real impact will come from creating new circular business models that account for the life cycle of a garment and design in the initial concept. If we want to maximize the value from each item of clothing, giving them second, third, and fourth lives is essential.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for support, in writing this Commentary, to Dr. Rina Arya, Professor of Visual Culture and Theory at the School of Art, Design, and Architecture of the University of Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, UK.

Declaration of Interests

The author is the co-founder of the International Society for Sustainable Fashion.

News from the Columbia Climate School

Why Fashion Needs to Be More Sustainable

The pandemic slowed fast fashion to a standstill. Now as the world opens up and we are socializing and going places, we want to dress up again. But after living a confined and simpler life during COVID, this is a good time to take stock of the implications of how we dress. Fashion, and especially fast fashion, has enormous environmental impacts on our planet, as well as social ones.

Since the 2000s, fashion production has doubled and it will likely triple by 2050, according to the American Chemical Society. The production of polyester, used for much cheap fast fashion, as well as athleisure wear, has increased nine-fold in the last 50 years. Because clothing has gotten so cheap, it is easily discarded after being worn only a few times. One survey found that 20 percent of clothing in the US is never worn; in the UK, it is 50 percent. Online shopping, available day and night, has made impulse buying and returning items easier.

According to McKinsey, average consumers buy 60 percent more than they did in 2000, and keep it half as long. And in 2017, it was estimated that 41 percent of young women felt the need to wear something different whenever they left the house. In response, there are companies that send consumers a box of new clothes every month.

Fashion’s environmental impacts

Fashion is responsible for 10 percent of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions and 20 percent of global wastewater, and uses more energy than the aviation and shipping sectors combined.

Impacts on water

Global fashion also consumes 93 billion metric tons of clean water each year, about half of what Americans drink annually.

Cotton is an especially thirsty crop. For example, one kilogram of cotton used to produce a pair of jeans can consume 7,500 to 10,000 liters of water—the amount a person would drink over 10 years. Cotton production also requires pesticides and insecticides, which pollute the soil; runoff from fertilized cotton fields carry the excess nutrients to water bodies, causing eutrophication and algal blooms.

The dyeing process for fabrics, which uses toxic chemicals, is responsible for 17 to 20 percent of global industrial water pollution.

Seventy-two toxic chemicals have been found in the water used in textile dyeing.

Contributions to climate change

To feed the fashion industry’s need for wood pulp to make fabrics like rayon, viscose and other fabrics, 70 million tons of trees are cut down each year. That number is expected to double by 2034, speeding deforestation in some of the world’s endangered forests.

The fashion industry produces 1.2 million metric tons of CO2 each year, according to a MacArthur Foundation study. In 2018, it resulted in more greenhouse gas emissions than the carbon produced by France, Germany and the UK all together. Polyester, which is actually plastic made from fossil fuels, is used for about 65 percent of all clothing, and consumes 70 million barrels of oil each year. In addition, the fashion industry uses large amounts of fossil fuel-based plastic for packaging and hangers.

Less than one percent of clothing is recycled to make new clothes. The fibers in clothing are polymers, long chains of chemically linked molecules. Washing and wearing clothing shorten and weaken these polymers, so by the time a garment is discarded, the polymers are too short to turn into a strong new fabric. In addition, most of today’s textile-to-textile recycling technologies cannot separate out dyes, contaminants, or even a combination of fabrics such as polyester and cotton.

As a result, 53 million metric tons of discarded clothing are incinerated or go to landfills each year. In 2017, Burberry burned $37 million worth of unsold bags, clothes and perfume. If sent to a landfill, clothes made from natural fabrics like cotton and linen may degrade in weeks to months, but synthetic fabrics can take up to 200 years to break down. And as they do, they produce methane, a powerful global warming greenhouse gas.

Microplastic pollution

Many people have lived solely in athleisure wear during the pandemic, but the problem with this is that the stretch and breathability in most athleisure comes from the use of synthetic plastic fibers like polyester, nylon, acrylic, spandex and others, which are made of plastic.

When clothes made from synthetics are washed, microplastics from their fibers are shed into the wastewater. Some of it is filtered out at wastewater treatment plants along with human waste and the resulting sludge is used as fertilizer for agriculture. Microplastics then enter the soil and become part of the food chain. The microplastics that elude the treatment plant end up in rivers and oceans, and in the atmosphere when seawater droplets carry them into the air. It’s estimated that 35 percent of the microplastics in the ocean come from the fashion industry. While some brands use “recycled polyester” from PET bottles, which emits 50 to 25 percent fewer emissions than virgin polyester, effective polyester recycling is limited, so after use, these garments still usually end up in the landfill where they can shed microfibers.

Microplastics harm marine life, as well as birds and turtles. They have already been found in our food, water and air—one study found that Americans eat 74,000 microplastic particles each year. And while there is growing concern about this, the risks to human health are still not well understood.

Fashion’s social impacts

Because it must be cheap, fast fashion is dependent on the exploited labor force in developing countries where regulations are lax. Workers are underpaid, overworked, and exposed to dangerous conditions or health hazards; many are underage.

Of the 75 million factory workers around the world, it’s estimated that only two percent earn a living wage. To keep brands from moving to another country or region with lower costs, factories limit wages and are disinclined to spend money to improve working conditions. Moreover, workers often live in areas with waterways polluted by the chemicals from textile dyeing.

How can fashion be more sustainable?

As opposed to our current linear model of fashion production with environmental impacts at every stage, where resources are consumed, turned into a product, then discarded, sustainable fashion minimizes its environmental impact, and even aims to benefit the environment. The goal is a circular fashion industry where waste and pollution are eliminated, and materials are used for as long as possible, then reused for new products to avoid the need to exploit virgin resources.

Many designers, brands, and scientists — including students in Columbia University’s Environmental Science and Policy program — are exploring ways to make fashion more sustainable and circular.

Since 80 to 90 percent of the sustainability of a clothing item is determined by decisions made during its design stage, new strategies can do away with waste from the get-go.

To eliminate the 15 percent of a fabric that usually ends up on the cutting room floor in the making of a garment, zero waste pattern cutting is used to arrange pattern pieces on fabric like a Tetris puzzle.

Designer YeohLee is known as a zero waste pioneer, employing geometric concepts in order to use every inch of fabric; she also creates garments with the leftovers of other pieces. Draping and knitting are also methods of designing without waste.

3D virtual sampling can eliminate the need for physical samples of material. A finished garment can sometimes require up to 20 samples. The Fabricant , a digital fashion house, replaces actual garments with digital samples in the design and development stage and claims this can reduce a brand’s carbon footprint by 30 percent.

Some clothing can be designed to be taken apart at the end of its life; designing for disassembly makes it easier for the parts to be recycled or upcycled into another garment. To be multifunctional, other garments are reversible, or designed so that parts can be subtracted or added. London-based brand Petit Pli makes children’s clothing from a single recycled fabric, making it easier to recycle; and the garments incorporate pleats that stretch so that kids can continue to wear them as they grow.

3D printing can be used to work out details digitally before production, minimizing trial and error; and because it can produce custom-fit garments on demand, it reduces waste. In addition, recycled materials such as plastic and metal can be 3D printed.

Sustainable designer Iris Ven Herpen is known for her fabulous 3D printed creations, some using upcycled marine debris; she is also currently working with scientists to develop sustainable textiles.

DyeCoo , a Dutch company, has developed a dyeing technique that uses waste CO2 in place of water and chemicals. The technology pressurizes CO2 so that it becomes supercritical and allows dye to readily dissolve, so it can enter easily into fabrics. Since the process uses no water, it produces no wastewater, and requires no drying time because the dyed fabric comes out dry. Ninety-five percent of the CO2 is recaptured and reused, so the process is a closed-loop system.

Heuritech , a French startup, is using artificial intelligence to analyze product images from Instagram and Weibo and predict trends. Adidas, Lee, Wrangler and other brands have used it to anticipate future demand and plan their production accordingly to reduce waste.

Mobile body scanning can help brands produce garments that fit a variety of body types instead of using standard sizes. 3D technology is also being used for virtual dressing, which will enable consumers to see how a garment looks on them before they purchase it. These innovations could lead to fewer returns of clothing.

Another way to reduce waste is to eliminate inventory. On-demand product fulfillment companies like Printful enable designers to sync their custom designs to the company’s clothing products. Garments are not created until an order comes in.

For Days, a closed-loop system, gives swap credits for every article of clothing you buy; customers can use swap credits to get new clothing items, all made from organic cotton or recycled materials. The swap credits encourage consumers to send in unwanted For Days clothes, keep them out of the landfill, and allow them to be made into new materials. Customers can also earn swap credits by filling one of the company’s Take Back bags with any old clothes, in any condition, and sending it in; these are then resold if salvageable or recycled as rags.

But perhaps the least wasteful strategy enables consumers not to buy any clothes at all. If they are mainly concerned about their image on social media, they can use digital clothing that is superimposed over their image. The Fabricant , which creates these digital garments, aims to make “self expression through digital clothing a sustainable way to explore personal identity.”

Better materials

Many brands are using textiles made from natural materials such as hemp, ramie or bamboo instead of cotton. Bamboo has been touted as a sustainable fabric because it is fast-growing and doesn’t require much water or pesticides; however, some old growth forests are being cut down to make way for bamboo plantations. Moreover, to make most bamboo fabrics soft, they are subjected to chemical processing whose toxins can harm the environment and human health.

Because of this processing, the Global Organic Textile Standard says that almost all bamboo fiber can “not be considered as natural or even organic fibre, even if the bamboo plant was certified organic on the field.”

Some designers are turning to organic cotton, which is grown without toxic chemicals. But because organic cotton yields are 30 percent less than conventional cotton, they need 30 percent more water and land to produce the same amount as conventional cotton. Other brands, such as North Face and Patagonia, are creating clothing made from regenerative cotton—cotton grown without pesticides, fertilizers, weed pulling or tilling, and with cover crops and diverse plants to enhance the soil.

Textiles are also being made with fibers from agriculture waste, such as leaves and rinds. Orange Fiber, an Italian company, is using nanotechnology to make a sustainable silky material by processing the cellulose of oranges. H&M is using cupro, a material made from cotton waste. Flocus makes fully biodegradable and recyclable yarns and fabrics from the fibers of kapok tree pods through a process that doesn’t harm the trees. Kapok trees can grow in poor soils without much need for water or pesticides.

In 2016, Theanne Schiros, a principal investigator at Columbia University’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center and assistant professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), mentored a group of FIT students who created a bio-design award-winning material from algae. Kelp, its main ingredient, is fast growing, absorbs CO2 and nitrogen from agricultural runoff, and helps increase biodiversity. With the help of Columbia University’s Helen Lu, a biomedical engineer, the team created a bio-yarn they called AlgiKnit . Having received over $2 million in initial seed funding, the start-up, based in Brooklyn, is scaling up for market entry.

Schiros and Lu also developed a microbial bioleather. The compostable material consists of a nanocellulose mesh made through a fermentation process using a culture of bacteria and yeast. Schiros explained that these bacteria produce cellulose nanofibers as part of their metabolism; the bacteria were used in the fermentation of kombucha as early as 220 BC in what was Manchuria and in vinegar fermentation as early as 5,000 BC in Egypt. Biofabrication of the material is 10,000 times less toxic to humans than chrome-tanned leather, with an 88 to 97 percent smaller carbon footprint than synthetic (polyurethane) leather or other plastic-based leather alternatives. The fabrication process also drew on ancient textile techniques for tanning and dyeing. Schiros worked with the designers of Public School NY on Slow Factory’s One x One Conscious Design Initiative challenge to create zero-waste, naturally dyed sneakers from the material.

Schiros is also co-founder and CEO of the startup Werewool , another collaboration with Lu, and with Allie Obermeyer of Columbia University Chemical Engineering. Werewool, which was recognized by the 2020 Global Change Award, creates biodegradable textiles with color and other attributes found in nature using synthetic biology . “Nature has evolved a genetic code to make proteins that do things like have bright color, stretch, moisture management, wicking, UV protection—all the things that you really want for performance textiles, but that currently come at a really high environmental cost,” said Schiros. “But nature accomplishes all this and that’s attributed to microscopic protein structures.”

Werewool engineers proteins inspired by those found in coral, jellyfish, oysters, and cow milk that result in color, moisture management or stretch. The DNA code for those proteins is inserted into bacteria, which ferment and mass-produce the protein that then becomes the basis for a fiber. The company will eventually provide its technology and fibers to other companies throughout the supply chain and will likely begin with limited edition designer brands.

Better working conditions

There are companies now intent on improving working conditions for textile workers. Dorsu in Cambodia creates clothing from fabric discarded by garment factories. Workers are paid a living wage, have contracts, are given breaks, and also get bonuses, overtime pay, insurance and paid leave for sickness and holidays.

Mayamiko is a 100 percent PETA-certified vegan brand that advocates for labor rights and created the Mayamiko Trust to train disadvantaged women.

Workers who make Ethcs ’ PETA-certified vegan garments are protected under the Fair Wear Foundation , which ensures a fair living wage, safe working conditions and legal labor contracts for workers. The Fair Wear Foundation website lists 128 brands it works with.

Beyond sustainability

Schiros maintains that making materials in collaboration with traditional artisans and Indigenous communities can produce results that address environmental, social and economic facets of sustainability. She led a series of natural dye workshops with women tie dyers in Kindia, Guinea, and artisans in Grand-Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire, and collaborated with New York designers to make a zero-waste collection from the fabrics created. The project connected FIT faculty and students to over 300 artisans in West Africa to create models for inclusive, sustainable development through textile arts, education, and entrepreneurship.

Partnering with frontline communities that are protecting, for example, the Amazon rainforest, does more than simply sustain—it protects biodiversity and areas that are sequestering carbon. “So with high value products that incorporate fair trade and clear partnerships into the supply chain, you not only have natural, biodegradable materials, but you have the added bonus of all that biodiversity that those communities are protecting,” she said. “Indigenous communities are five percent of the global population, and they’re protecting 80 percent of the biodiversity in the world…Integrating how we make our materials, our systems and the communities that are sequestering carbon while protecting biodiversity is critically important.”

The need for transparency

In order to ensure fashion’s sustainability and achieve a circular fashion industry, it must be possible to track all the elements of a product from the materials used, chemicals added, production practices, and product use, to the end of life, as well as the social and environmental conditions under which it was made.

Blockchain technology can do this by recording each phase of a garment’s life in a decentralized tamper-proof common ledger. Designer Martine Jarlgaard partnered with blockchain tech company Provenance to create QR codes that, when scanned, show the garment’s whole history. The software platform Eon has also developed a way to give each garment its own digital fingerprint called Circular ID. It uses a digital identifier embedded in the clothing that enables it to be traced for its whole lifecycle.

Transparency is also important because it enables consumers to identify greenwashing when they encounter it. Greenwashing is when companies intentionally deceive consumers or oversell their efforts to be sustainable.

Amendi , a sustainable fashion brand focusing on transparency and traceability, co-founded by Columbia University alumnus Corey Spencer, has begun a campaign to get the Federal Trade Commission to update its Green Guides, which outline the principles for the use of green claims. When the most recent versions of the Green Guides were released in 2012, they did not scrutinize the use of “sustainability” and “organic” in marketing. The use of these terms has exploded since then and unless regulated, could become meaningless or misleading.

What consumers can do

The key to making fashion sustainable is the consumer. If we want the fashion industry to adopt more sustainable practices, then as shoppers, we need to care about how clothing is made and where it comes from, and demonstrate these concerns through what we buy. The market will then respond.

We can also reduce waste through how we care for our clothing and how we discard it.

Here are some tips on how to be a responsible consumer:

- Buy only what you need

- Look for sustainable certification from the Fairtrade Foundation , Global Organic Textiles Standard , Soil Association , and Fair Wear Foundation

- Check the Fashion Transparency Index to see how a company ranks in transparency.

- Learn how to shop for quality and invest in higher-quality clothing

- Choose natural fibers and single fiber garments

- Wear clothing for longer

- Take care of clothing: wash items less often, repair them so they last. Patagonia operates Worn Wear , a recycling and repair program.

- Upcycle your unwanted clothes into something new

- Buy secondhand or vintage; sell your old clothes at Thred Up, Poshmark, or the Real Real.

- When discarding, pass clothing on to someone who will wear it, or to a thrift shop

- Rent clothing from Rent the Runway , Armoire or Nuuly

“I think the best piece of clothing is the one that already exists. The best fabric is the fabric that already exists,” said Schiros. “Keeping things in the supply chain in as many loops and cycles as you can is really, really important.”

Related Posts

Scaling the Mountains of Textile Waste in New York City

A Glimpse at the Columbia Climate School in the Green Mountains Program

Meet the Woman Pioneering Sustainable Change in Fashion

Recent record-breaking heat waves have affected communities across the world. The Extreme Heat Workshop will bring together researchers and practitioners to advance the state of knowledge, identify community needs, and develop a framework for evaluating risks with a focus on climate justice. Register by June 15

I’ve been buying second hand and or making my own clothes my whole life and I’m 72. It makes sense, it’s cost effective and that way you can buy more clothes or fabric. Win win.

So r u saying it is more cheap this way?

yes it does im the youngest of 7 so i get hand me downs it way more ecofrindly to

This is an excellent article! I am writing a paper on sustainable fashion and find this article to be an informative and eloquent resource in my research! Thank you!

What has Fast Fashion done to the labor practices, working conditions and wages of workers in Asian countries and what can be done to promote more sustainable and fair practices in the industry?

Making your own garments from natural, and ideally organic, fabrics is one of the best ways to both love your wardrobe (because the color, fit and design is something that works for you, specifically) and you can incorporate Construction techniques that prolong the life of the seams and the garment overall. just make sure you shrink it first!

Fabric scraps can be saved and repurposed, as solid pieces or patch worked together. A scrunchie. A cloth bag. Menstrual pads. Potholders. Tiny cloth plant pots. Little travel bags to protect shoes, hairdryer, toiletries, to separate socks and underwear. There are high end men’s shirts that incorporate interesting prints inside the collar and cuffs, for example. Then there is the ministry of making quilts. Quilts can be sent to refugees who Use them for warmth at night and for walls by day. they don’t have to be elaborate or elegant, but using a little bit of love and creativity, you can create something attractive. Torn sheets and worn out clothes can be repurposed and using them as fabric to instruct young sewers And how to handle different types of fabric is another worthy use. Imperfect attempts could be useful if the learner turns out a dog bed cover, or little sweaters for those dogs that get cold all the time. Animal shelters are usually very happy to receive these kinds of things.

Sewers can meet together for fabric swaps in the same way that people sometimes get together to do wardrobe swaps. That might be that someone else is done with the exact fabric that would be awesome to mix with something that you have left over.

very interesting. please share with us

Best post. Good to see content like this.

your information is very helpfull.

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

Environmentally sustainable fashion and conspicuous behavior

- Sae Eun Lee 1 nAff2 &

- Kyu-Hye Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7468-0681 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 498 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1902 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Environmental studies

This study examines the impact of conspicuous consumption on environmentally sustainable fashion brands (ESFBs). Most previous studies have been limited to environmental perspectives; however, research on environmental behavior by conspicuousness has been lacking. This study views the brand as a tool for revealing oneself and examines the moderator brand–self-connection. It utilized a structural equation model with 237 valid questionnaires. Its findings are as follows: (1) Conspicuous consumption, fashion trend conspicuousness, and socially awakened conspicuousness positively affect the word-of-mouth (WOM) marketing of ESFBs. (2) Environmental belief is fully mediated by the environmental norm (EN) and does not directly affect WOM. (3) The more consumers are consistent with ESFBs, the stronger their WOM marketing. They are moderated only by the EN and socially awakened conspicuousness. (4) A higher fashion trend conspicuousness is associated with increased WOM marketing, indicating that such brands are frequently used as a method of self-expression. This study highlights consumers’ socially awakened conspicuousness and fashion trend conspicuousness in relation to ESFBs and discusses some implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Predicting sustainable fashion consumption intentions and practices

The impact of country of origin on consumer purchase decision of luxury vs. fast fashion: case of Saudi female consumers

Exploring the impact of beauty vloggers’ credible attributes, parasocial interaction, and trust on consumer purchase intention in influencer marketing

Introduction.

The emergence of sustainable consumption as a new trend can be attributed to the growing environmental consciousness (Kerber et al. 2023 ; Zameer and Yasmeen, 2022 ). This is evident in the increasing involvement of fashion brands in the Fashion Pact, a global agreement aimed at promoting environmental sustainability (The Fashion Pact, 2023 ). Patagonia, a company renowned for its commitment to sustainability, conducts various activities under its corporate motto, such as using 98% recycled material and sourcing electricity from 100% renewable sources while maintaining its top position in the outdoor apparel market (Alonso, 2023 ). Additionally, non-apparel industry brands have embraced the pursuit of sustainability. Freitag, a fashion industry brand that produces recycled bags from used truck tarps, has continued to gain popularity over the past three to four years (Ga, 2022 ). Since its launch in 2017 specializing in pleated knit bags crafted from recycled yarn derived from discarded plastic bottles, Pleats Mama has experienced an annual growth rate of 150% on average (Kim, 2022a ). In response to the climate change crisis, which is exacerbated by global warming, even luxury brands such as Burberry, Prada, and Gucci have begun incorporating sustainable fashion products into their collection. Consequently, within the last five years, approximately 30% of consumers have increased their purchase of sustainable products, resulting in a 32% increase in the market share of these products (Ruiz, 2023 ; Tighe, 2023 ). In summary, brands such as Patagonia, Freitag, and Pleats Mama, which prioritize environmental sustainability, article are gaining prominence (Little, 2022 ). This is due to the growing enthusiasm of consumers towards these brands’ environmental sustainability initiatives.

Even if a given brand does not explicitly focus on environmental sustainability, environmental values and beliefs significantly influence consumers’ purchasing decisions, according to research on sustainable fashion (Apaolaza et al. 2022 ; Bianchi and Gonzalez, 2021 ; Park & Lin, 2020 ). Moreover, studies demonstrate that consumers are increasingly resorting to luxury and fast fashion brands—often regarded as the major contributors to environmental pollution—for environmental reasons. This trend is attributable to these brands’ effective sustainable marketing strategies (Neumann et al. 2020 ; Stringer et al. 2020 ; Zhang et al. 2021 ). In other words, through their marketing strategies, these brands are successfully positioning themselves as sustainable choices, which results in meaningful purchase intentions among consumers.

However, these previous studies do not consider fashion’s symbolic function or social meaning. By wearing sustainable fashion brands, consumers seek to demonstrate their commitment to environmental beliefs(EBs). Consumer behavior toward sustainable fashion is not driven by EBs. For other reasons, the purchase is made in a conspicuous context (Legere & Kang, 2020 ; Stringer et al. 2020 ). Numerous studies have documented this phenomenon, with a particular focus on certain conspicuous activities in philanthropic research. Generally known as comprising actions that are motivated by altruistic values, philanthropy is currently being evaluated in terms of its sustainability. For instance, the mission of Or Foundation, a public charity based in the USA, is to establish an alternative model of ecological prosperity (Wong, 2023 ). In fact, private philanthropy has been found to play a key role in sustainable development (Gautier and Pache, 2015 ; Porter and Kramer, 2002 ). However, although such actions spring from good intentions, they also involve certain aspects that are determined by motives other than altruism. That is, philanthropic research indicates that these endeavors are frequently associated with a desire for recognition and respect (De Dominicis et al. 2017 ; Grace and Griffin, 2009 ; Wallace et al. 2017 ). This behavior may stem from a conspicuous desire to be acknowledged by others for social awareness and to receive praise and validation from followers, particularly when such actions are shared on social networking sites (SNS) (e.g., the ice bucket challenge and bracelets for Japanese military sexual slavery grandmothers). Intending to gain respect from others, individuals tend to engage in acts that may be considered as “displaying” or “showing off,” even in the case of eco-friendly purchases and environment-related word-of-mouth (WOM) behavior.

Conspicuousness is evident in less visible charitable activities and fashion products with higher visibility and symbolic value. Regarding luxury fashion products, including those that incorporate sustainable marketing strategies, consumers may still prioritize luxury symbols for their conspicuousness, despite the significance of sustainable beliefs (Ki and Kim, 2016 ; Mishra et al. 2023 ). Consequently, it is essential to investigate whether conspicuous consumption occurs concerning environmentally sustainable fashion brands (ESFBs) rather than luxury brands. By publicly displaying one’s decision to wear an ESFB, one can establish oneself as a socially conscious individual and a fashion leader, potentially leading a new consumption trend or gaining a following. Hence, it is crucial to examine whether consumers’ choices are driven by sustainable beliefs or constitute conspicuous behavior. Consumers want to express themselves through the meaning of a brand. They believe that they “connect” with a brand and choose to wear it for its meaning (Escalas, 2004 ; Escalas and Bettman, 2003 ). Therefore, the more one connects to a brand, the more one can actively wear it to express one’s beliefs. The study’s research questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1. Do consumers truly engage in WOM behavior in relation to ESFBs based on EBs? Do they have no conspicuous intentions?

RQ2. As brands express self-concept, do consumers reinforce WOM behavior to support environmental norms (ENs) and reveal their EBs? What role does the self-brand connection of ESFB consumers play if conspicuous intentions exist?

This study aims to examine the effect of conspicuousness on consumer behavior concerning ESFBs, a topic that is yet to be examined. Conspicuousness is specifically subdivided into that of the fashion trend leader and that of a socially awakened person. Consumers who utilize ESFBs as a means of expressing their identity are confronted with the decision of whether to reinforce environmental behavior or conspicuous behavior. As a result, we must identify consumers’ purchasing motives for ESFBs and flesh out their implications.

Literature review

Environmental sustainability.

Our Common Future, which defines sustainability, posits environmental sustainability as one of the three concepts of sustainable development (society, economy, environment) (Brundtland, 2013 ). Environmental sustainability can be defined as the “maintenance of natural capital,” which involves at least the reduction of the level of resource use or depletion of environmental assets (Goodland, 1995 ). In the aftermath of global warming, concerns regarding the sustainability of natural resources have intensified due to global boiling (Arora and Mishra, 2023 ). Accordingly, environmental sustainability is becoming more important than it was before. According to Morelli ( 2011 ), sustainability is “good” and is frequently abused for expertise or contributions in a certain field, regardless of the actual effects exerted on the natural environment or ecological health. Environmental sustainability should be viewed as an essential human activity for supporting the ecosystem based on sound ecological concepts. Goodland ( 1995 ) describes environmental sustainability as a set of constraints, involving “the use of renewable and nonrenewable resources on the source side, and pollution and waste assimilation on the sink side” (p. 10). Most research on environmental sustainability focuses on exploring what should be done from an environmental perspective (Ögmundarson et al., 2020 ; Koul et al., 2022 ) and the impact each country has on the environment (Yang and Khan, 2022 ; Yang et al., 2022 ). In addition, environmental sustainability is a crucial consideration in business decision-making because it involves finding a balance between economic productivity and minimizing environmental impact (Lou et al., 2022 ). One of these is the study of secondhand consumption (Cuc & Vidovic, 2014 ; Xue et al. 2018 ). Although many companies claim to prioritize sustainability, they often focus on economic and social sustainability rather than issues of environmental sustainability (Brydges et al. 2022 ). Environmental sustainability is frequently compromised in this way for marketing strategies (Salnikova et al, 2022 ; Vesal et al. 2021 ; Villalba‐Ríos et al. 2023 ) or for achieving environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) (Khalil & Khalil, 2022 ; Prömpeler et al. 2023 ). Consumers are no longer fooled by sustainability marketing, which they perceive as greenwashing (Kahraman and Kazançoğlu, 2019 ; Nguyen et al. 2021 ). Accordingly, consumers base their purchases on their knowledge and awareness of brands that advocate environmental activism rather than merely participating in greenwashing (Venkatesan, 2022 ).

Sustainable fashion

Regarding environmental sustainability, the fashion industry encounters significant challenges because it consumes substantial amounts of water, energy, and chemicals while generating disposal problems (Lou et al., 2022 ). At a time when consumer demand for ESG is increasing, various sustainable fashion initiatives have emerged in the industry. Various green branding and eco-labeling initiatives, as well as sustainable logistics practices, have been implemented (Sandberg and Hultberg, 2021 ). H&M and Zara, representative fast fashion brands, are also implementing various sustainable strategies in line with this trend (Dzhengiz et al. 2023 ; Rathore, 2022 ). The growing platform for secondhand fashion after the COVID-19 pandemic serves as a representative example (Kim and Kim, 2022 ). However, many consumers view sustainability assertions in the fashion industry as mere marketing strategies (i.e., greenwashing) and express doubts about the genuineness of these efforts (Szabo and Webster, 2021 ). Brydges et al. ( 2022 ) have also examined the communication strategies employed by fashion companies and found that consumers perceive these strategies as a form of greenwashing aimed at selling sustainability. These concerns have made certain fashion brands, such as Freitag and Patagonia, shift their focus to environmental sustainability. To evaluate the impact of sustainability, Patagonia specifically established the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) and spearheaded efforts to develop the Higg Index. This company has developed new processes to address environmental issues and prioritized recycling fibers and using recycled textiles to reduce their landfill waste (Bhuiyan et al. 2023 ; Pandey et al. 2020 ). Consumers are actively supporting and consuming brands that genuinely prioritize environmental sustainability as opposed to merely engaging in greenwashing practices. Consumption is increasing for ESFBs that adhere to the “maintenance of natural capital” (Rathore, 2022 ). However, focus on consumer behavior toward ESFBs is still lacking; thus, it is necessary to investigate consumer perceptions and behaviors concerning these brands.

Hypothesis development

Environmental beliefs and norms.

Consumers are cognizant of the seriousness of environmental pollution and are actively implementing eco-friendly actions. EBs are unshakeable beliefs or attitudes that guide individuals to decide to protect the environment (Gray et al., 1985 ). Inglehart ( 1995 , 1997 ) asserted that as the economy develops and modernizes, EB emerges because people are concerned about the environmental state. Thus, developed country consumers are likely to recognize ESFBs and consume them, knowing that the promotion of various sustainable brands is a marketing strategy (greenwashing) due to the high EB. Environmental norm (EN) is an important and strong motivating factor that influences environmental behaviors and signifies a sense of responsibility or moral obligation to the environment. Additionally, activated and internalized EB helps in overcoming obstacles to individual behavior based on a sense of duty (Babcock, 2009 ). These EBs and ENs are mainly used for research on eco-friendly behaviors, especially those grounded in Stern’s ( 2000 ) value-belief-norm (VBN) theory. Based on the VBN theory, it is hypothesized that individuals with strong environmental values and norms are more likely to engage in sustainable consumption practices, thereby resulting in better environmental behaviors. Additionally, it is expected that consumers in developed countries will exhibit a greater propensity to recognize greenwashing and to consider environmental values and norms, especially when purchasing from environmentally sustainable fashion brands (ESFBs). Furthermore, it is widely believed that ENs serve as a crucial mediator in the relationship between EBs and eco-friendly behaviors, as supported by previous research in areas such as green cosmetics and green hotels (Jaini et al., 2020 ; Ruan et al., 2022 ).

The hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis (H1) . EB positively affects EN .

WOM plays a vital role in shaping consumer attitudes and purchasing behavior (Yang et al, 2012 ). Furthermore, with the widespread use of SNS, e-WOM has enabled consumers to easily access evaluations and opinions about various products and services. WOM is a widely applied factor in marketing, and 61% of key marketers select it as one of the most effective marketing tools (Berger, 2014 ). Consumers are gradually adopting more environmentally conscious purchasing practices as their awareness of the environmental impact of their purchasing decisions grows. Specifically, it has been discovered that the acquisition of diverse environmental information through SNS platforms contributes to the growth of pro-environmental behavior (Jain et al. 2020 ). The WOM intention for eco-friendly products refers to the communication between consumers and other people or groups (such as social channels, friends, and relatives.) of experiences about the purchase of such products (Chaniotakis and Lymperopoulos, 2009 ). A significant correlation, according to Chun et al. ( 2018 ), exists between environmental value, belief, attitude, and WOM intention for upcycling products. Gatersleben et al. ( 2002 ) assert that EB can be formed through value awareness and lead to specific behavioral intentions. According to Panda et al. ( 2020 ), environmental sustainability awareness positively impacts both green purchase intention and green brand evangelism. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that EBs directly influence pro-environmental behavioral intentions and attitudes toward ecotourism (Li et al. 2021 ; Nguyen & Le, 2020 ). As noted in prior research on VBN theory, ENs impact environmental behavior (Stern et al. 1999 ; Stern, 2000 ). Certain studies have examined the influence of norms on predicting pro-environmental attitudes. According to Jansson et al. ( 2010 ), EB, EN, and habit influence Swedish consumers’ willingness to purchase green products. Bakti et al. ( 2020 ) found that different norms (subjective, moral, environmental) affect the WOM regarding the use of public transportation for environmental reasons. Hence, both EBs and ENs significantly influence the WOM behavior toward a brand.

Hypothesis (H2) . EB positively affects WOM .

Hypothesis (H3) . EN positively affects WOM .

Conspicuousness on WOM

The goal-framing theory, proposed by Lindenberg ( 2000 , 2001 , 2008 ), elucidates how goals influence human perception, thoughts, and decision-making processes. According to this theory, human needs can be categorized into three types: gain goals, which involve knowledge and information acquisition; normative goals, which emphasize appropriate behavior based on social norms; and hedonic goals, which prioritize perceived pleasure. In each situation, one goal is typically prioritized over the others; these goals coexist and form a frame through mutual competition. Lindenberg and Steg ( 2007 ) applied the goal-framing theory to explain pro-environmental and pro-social behaviors. They proposed that individuals who prioritize the normative goal are increasingly likely to engage in eco-friendly actions. In contrast, those who prioritize gain and hedonic goals may engage in non-eco-friendly behaviors. This theory has been utilized to support research on various consumer behaviors, including those influenced by environmental beliefs, norms, and other goals and motivations (Mishra et al., 2023 ; Yang et al. 2020 ). Additionally, the pursuit of hedonic goals can explain why consumers pursuing conflicting goals, including normative goals for eco-friendly behavior, may still engage in eco-friendly actions. Liobikienė and Juknys ( 2016 ) contended that individuals with hedonic goals may occasionally engage in environmentally friendly behavior with pleasure and joy. Mishra et al. ( 2023 ) examined the use of the luxury sharing economy in emerging markets. They found that consumer behavior was significantly influenced by the hedonic goal of conspicuousness.

Previous research discovered that conspicuous consumption has a static effect on sustainable clothing purchase intention (Apaolaza et al. 2022 ; Hammad et al. 2019 ). Because sustainable fashion products are fashion goods, they have the characteristics of fashion, such as trends, styles, and symbols. Unlike other sustainable products, a fashion product cannot ignore the attributes of fashion. Clothing is especially used as a means of self-expression. This is because the values and thoughts conveyed through clothing are symbolic and communicate meaning to others. Prior research on sustainable fashion has examined aspects of flaunting one’s social status and showcasing the latest trends in fashion. Additionally, Cervellon and Shammas ( 2013 ) validated the conspicuousness of the symbol of sustainable luxury products. A pursuit of personal style, as demonstrated by Ki and Kim ( 2016 ) enables consumers to make sustainable luxury purchases. The study on sustainable fashion consumption conducted by Lundblad and Davies ( 2016 ) also identified self-expression as a significant determinant. Therefore, showcasing an eco-friendly image, which involves being socially awake and positioning oneself as a fashion leader, can affect WOM, an active eco-friendly purchasing behavior. The following hypotheses can be made:

Hypothesis (H4) . Fashion trend conspicuousness (FTC) positively affects WOM .

Hypothesis (H5) . Social awaken conspicuousness (SAC) positively affects WOM .

Self-brand connection

Self-concept serves as the foundation for symbolic consumption; it originates from the motivation of self-enhancement and maintenance of self-esteem, which express individual values and is interpreted as behavior for social adoption (Greenwald & Farnham, 2000 ; Shavitt, 1990 ). Consumers feel a “sense of self-definition” by consuming products and services and communicating about them to others. That is why they identify with a brand and prefer a brand that can reflect and express their self-concept. In other words, consumers may use a brand as a physical representation of themselves to establish a connection with it; this is known as self-brand connect (SBC) (Escalas, 2004 ; Escalas and Bettman, 2003 ).

SBC positively correlates with behavioral intention, such as brand choice and loyalty, as well as brand attitudes (Escalas, 2004 , Moore and Homer, 2008 ; Naletelich and Spears, 2020 ). When the self-image aligns with the brand’s image is congruent, and when the brand can protect and enhance the self-image, there will be an increase in purchases and loyal customers for the brand. In addition, in comparison to consumers with low SBC, those with strong SBC utilize the brand primarily for self-expression, have more favorable evaluations of the brand, and have higher behavioral intentions. Conversely, consumers with low SBC tend to have low motivation to express their true selves through the brand and have a low attachment to the brand (Ferraro et al. 2013 ).

Consumers are increasingly cognizant of the issue of greenwashing, which is not truly sustainable, and are reluctant to purchase greenwashing brands (Apaolaza et al. 2022 ). The more consumers believe they are eco-friendly, the more likely they are to perceive a sustainable brand as greenwashing and passionately consume more environmentally sustainable brands. In other words, consumers must establish a profound emotional bond with the ESFB that reflects their eco-friendly beliefs and images. Therefore, consumers who express their environmental identity with environmentally sustainable brand (ESB) can be expected to reinforce eco-friendly behavior. The following hypotheses can be made:

Hypothesis (H6a) . SBC moderates between EB and WOM

Hypothesis (H6b) . SBC moderates between EN and WOM

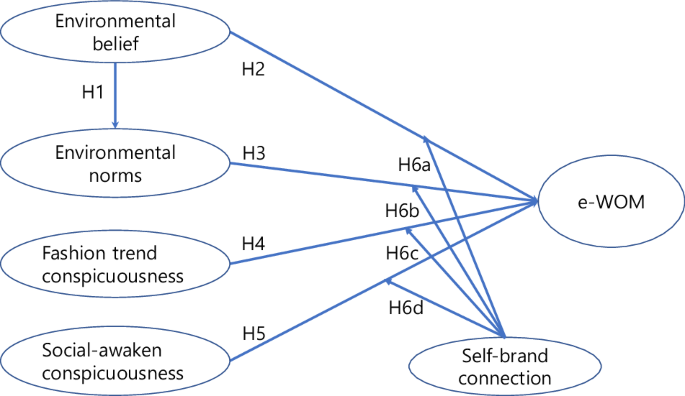

Consumers utilize the brand’s symbolism to show off their identity. Apaolaza et al. ( 2022 ) asserted that a sustainable brand can increase purchase intention through conspicuousness when perceived as useful. In other words, if the utility of revealing one’s identity increases, the possibility of consumption behavior such as WOM increases. Meanwhile, if ESFBs represent their identity, but have a strong motivation to reveal that they are socially aware of eco-friendliness, then it is likely to be used as a means of conspicuousness. The following hypotheses can be made (Fig. 1 ):

Research framework.

Hypothesis (H6c) . SBC moderates between FTC and WOM

Hypothesis (H6d) . SBC moderates between SAC and WOM .

Sample and data collection

The survey focused on fashion brands that prioritize environmental sustainability. First, the concept of ESFBs was explained to university students in the classroom, and brands were recommended to them. The process of brand selection involved considering the definition of environmental sustainability, which we established as the “maintenance of natural capital.” In doing so, we assessed each brand according to the information provided on their websites regarding their corporate philosophy and manufacturing method. Specifically, brands that promote recycling, reusing, and reclaiming, such as utilizing recycled polyethylene terephthalate yarn or repurposing discarded materials, were selected. To confirm whether the selected brand was suitable to be classified as an ESFB, two professors and three doctoral students confirmed the definition of ESFB and face validity. After checking the current awareness of the selected brands using a preliminary survey of 28 graduate students, three brands were ultimately selected as ESFBs in descending order of popularity: Patagonia (USA), Pleat Mama (Korea), and Freitag (Switzerland). Considering Korea’s tendency for other-oriented consumption, questionnaires were administered to Korean individuals aged between 20 and 40 years (Park et al., 2008 ). This demographic was considered suitable for examining tendencies toward conspicuous consumption of ESFBs. The survey focused on the participants’ purchasing experiences or intentions regarding Patagonia, Pleat Mama, and Freitag. The online survey required participants to indicate whether they had experience purchasing the brands in the past before proceeding to the main question. If they had no prior purchase experience with the brands in question, respondents were further asked regarding their purchase intention toward the brands. Only those with high scores proceeded to the main question. Furthermore, the survey was restricted to respondents who recognized the three brands in question as ESFBs. Data was collected through e-mail, facilitated by an online survey company, which also motivated the participants with rewards. Out of the initial 260 respondents who completed the questionnaire, 237 responses were considered reliable after removing the inconsistent or unreliable responses.

Respondents’ characteristics

The demographics of the 237 sampled respondents are as follows: 17.7% were in their 20 s, 37.6% were in their 30 s, and 44.7% were in their 40 s. The average age of 37.37 years was recorded. Of the respondents, 18.1 and 81.9% were men and women, respectively. Several previous studies have exhibited gender effects on sustainable consumption, indicating that women are more active than men (Bloodhart and Swim, 2020 ; Kim, 2022b ). As such, instead of following the population ratio, it can be argued that the sample in this study is representative of the market segment. Of the respondents, 90.7% had a high level of educational background, with the majority holding master’s degrees. The average monthly clothing expenditures of the respondents were $50–100 (37.1%) and $100–200 (27.8%). Table 1 provides more details.

Measurement

In this study, the measurement tools used to identify sustainable fashion WOM, such as belief, concern, and conspicuousness, are as follows. EB scale and EN both consisted of six questions, following Stern ( 2000 ). FTC was composed of three items, as stated by Ki and Kim ( 2016 ). SAC was composed of four items, following Grace and Griffin ( 2009 ), while WOM for consumer brands was also four items, as described by Molinari et al. ( 2008 ). Six items were in SBC, following van der Westhuizen ( 2018 ). All items were measured utilizing a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The final section was composed of questions regarding demographic information (Table 1 ).

Measurement validity and reliability

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), which is an efficient method for predicting latent variables, minimizes estimation errors. In contrast, AMOS-based SEM, which is covariance-based, is more suitable for analyzing and testing theories in the social sciences (Dash and Paul, 2021 ; Mia et al. 2019 ). Furthermore, the basic assumption of AMOS entails a normal distribution with a minimum sample size of 200 or more, and this is satisfied by this study. Additionally, AMOS (CB-SEM) utilizes the maximum likelihood estimation that is significant to the parameter estimation (Stevens, 2009 ; Westfall and Henning, 2013 ). To verify the reliability and validity of the measurement variables used here, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (Table 2 ). The model exhibited an acceptable fit: GFI = 0.908; CFI = 0.969; NFI = 0.928; RMR = 0.033; RMSEA = 0.055; χ 2 = 233.328 (d f = 137); p < 0.000; normed χ 2 = 1.703. All the items in the model were significant. To verify the convergence validity of the measurement model, we confirmed the significance levels of the average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and factor loading (Hair et al., 2010 ). The factor loading of the measurement variable was significant at the 1% level. The AVE and CR values were 0.519–0.790 and 0.764–0.933, respectively; these values are considered high. The Cronbach’s α , which measures reliability, was more than 0.7; thus, internal consistency was confirmed.

Discriminant validity was measured in this study using Fornell and Larcker’s ( 1981 ) recommendations suggested. It refers to a state in which researchers identify that each indicator of a theoretical model differs statistically. It can be calculated by comparing AVE with squared correlations. It is supported when the AVE among each pair of constructs is greater than Φ 2 (i.e., the squared correlation between two constructs) (Table 3 ).

Hyperthesis testing

To verify our hypotheses, we performed an analysis of the covariance structure model. The results are illustrated in Fig. 1 . The hypothesized structural model generated a good fit ( χ 2 = 106.982, df = 82, p = 0.033, Normed χ 2 = 1.305, GFI = 0.945, CFI = 0.987, RMR = 0.029, TLI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.036). EB positively affected EC ( β = 0.783, p < 0.000); thus, H1 was supported. The structural model analysis indicated that EB was not affected by WOM ( β = −0.160, p = 0.223). Thus, H2 is rejected. EC positively affected WOM ( β = 0.265, p < 0.05); thud, H3 is supported. FTC ( β = 0.219, p < 0.01) and SAC ( β = 0.545, p < 0.001) positively affected WOM; thus, H4 and H5 are supported. The outcomes of the hypothesis testing are presented in Table 4 .

Moderating effect of self-brand connection

The results of the chi-square difference test between the unconstrained model and the measurement weight model were Δ χ 2 = 21.970, d f = 13, and p = 0.059. The non-significant change in model fit indicated that the factor loadings were invariant between the two groups, confirming the full measurement-invariance model. For SBC with an EB-WOM link, no significance was detected for the high (β = -0.221, p = 0.240) and low ( β = −0.174, p = 0.317) groups, and no significant differences in path strength were detected by SBC(Δ χ 2 = 0.053, p > 0.05). The effect of EN on WOM was significant for high ( β = 0.406, p < 0.05) and low ( β = 0.188, p = 0.343) groups, while those with high EN(Δ χ 2 = 5.049, p < 0.05) were significantly stronger. For SBC with an FTC-WOM link, no significance was detected for the high ( β = 0.059, p = 0.638) and low ( β = 0.337, p < 0.01) groups, and no significant differences in path strength were detected by SBC(Δ χ 2 = 3.170, p > 0.05).

The effect of SAC on WOM was significant for the high ( β = 0.691, p < 0.000) and low ( β = 0.174, p = 0.121) groups, while those with high SAC (Δ χ 2 = 4.713, p < 0.05) were significantly stronger. Thus, H6a and H6c were rejected, whereas H6b and H6d were found to be moderate between EN/SAC and WOM in this study (Table 5 ).

As sustainability is perceived as a marketing strategy, greenwashing, many consumers are engaging in consumption behavior toward true ESFBs. Previous studies on sustainable brands did not focus on ESFB, which concentrates on “maintenance of natural capital” such as fiber recycling and the use of recycled fibers. Particularly, fashion products have a way of showing off as symbolism; therefore, studies are focusing on sustainable fashion brands. However, it is necessary to examine whether conspicuousness exists in ESFB. Our findings were as follows:

First, both conspicuous consumption, FTC and SAC, positively impacted ESFB’s WOM. This is a remarkably interesting result, inducing consumer behavior even more strongly than EB. Due to greenwashing, consumers are more enthusiastic about ESFB than sustainable brands. However, this also confirms that consumers choose ESFB to show off as socially advanced and awakened persons. Showing off as a person who is more aware of the environment than others constitutes WOM. This was also chosen by ESFB as a way to flaunt themselves, and it can be viewed in the same context as the previous conspicuousness of charity. ESFB was also discovered to possess an inherent fashion attribute, in addition to the FTC. This is believed to be because ESFBs possess fashion characteristics. Because of the presence of visibility and symbolism, which are the characteristics of fashion, wearing an ESFB can convey the symbol and value of those brands to the observer. This phenomenon is consistent with previous sustainable fashion research (Apaolaza et al. 2022 ; Cervellon and Shammas, 2013 ; Hammad et al. 2019 ). In other words, consumers can show off themselves as socially awakened beings by wearing an EFSB and as trailblazers in fashion trends. Therefore, it will be necessary for a sustainable fashion company to not only put an emphasis on sustainability but also endeavor to reflect the latest fashion trends. Furthermore, brands’ self-image conspicuousness requirements must be met.

Second, it was established that EB had no direct effect as a factor that influenced ESFB’s WOM. This result contradicts the finding that EB directly affects pro-environmental behavior (Li et al. 2021 ; Nguyen & Le, 2020 ). However, in addition to the relationship between EN and EB, as proposed by Stern et al. ( 1999 ) and Stern ( 2000 ) in their VBN theory, ESBN further validates the indirect effect that EB causes behavior through EN. It also supports the goal-framing theory, which posits that normative goals further enhance pro-environmental behavior (Lindenberg and Steg, 2007 ). Because EN is the only way to act eco-friendly, it can be confirmed that consumers should focus more on EN rather than EB, notwithstanding the quality of ESFB.

Third, it was discovered that the strength of WOM increased with the degree of ESFB consistency and only moderated in EN and SAC. EN was a norm that was influenced by surroundings. When engaging in WOM communication by EN companies, consumers who strongly identify with eco-friendly values are more likely to participate in WOM actively. This can reveal through ESFB that they follow the norms well; thus, these actions were a means of showing one’s compliance with the norms. Through the ESFB identity, they increasingly demonstrated their commitment to eco-friendly norms.

In addition, fashion brands hold symbolic value, and higher FTC is associated with increased WOM, indicating that these brands are often used to express one’s identity. Fashion leaders who aim to showcase their fashion-forward image tend to purchase brands that align with their innovative fashion identity. This is why they prefer high-end fashion brands. However, within the framework of ESFBs, this research failed to identify any significant moderating effect between FTC and SBC. Although not statistically significant, individuals with low SBC exhibited a greater intensity of WOM. This finding contradicts previous studies (Apaolaza et al. 2022 ; Hammad et al. 2019 ), which suggested that WOM is stronger among individuals with higher fashion conspicuousness who want to showcase their identity. True sustainability is the identity associated with ESFBs. The finding that WOM is stronger among individuals who do not want to emphasize their eco-friendliness can be attributed to their desire to showcase fashion trends rather than the brand’s eco-friendliness.

This study has several academic and practical implications. First, it expands the existing research on ESFBs by examining their WOM marketing and the conspicuousness associated with consumers buying them. Although prior studies on sustainable fashion focus solely on sustainability aspects, this study acknowledges the existence of FTC and SBC as well. In future research, incorporating consumers’ FTC and SBC into the research model can enhance its explanatory power and provide a comprehensive understanding of ESFBs. Second, fashion trends must be reflected in ESFBs as well. Sustainable fashion research focuses on exploring consumer perceptions of sustainability and marketing strategies. However, as demonstrated by this study, ESFBs are still fashion brands; therefore, they appeal to consumers by staying updated with the latest trends. When consumer interest in sustainability is high, it becomes crucial to develop merchandising strategies that incorporate sustainability while simultaneously attending to the latest fashion trends. Thus, ESFBs necessarily consider prevailing trends as well. Third, this study also emphasizes the necessity of incorporating true environmental sustainability into consumer education. For example, a curriculum or training program aimed at identifying authentic ESFBs, as opposed to those that simply engage in greenwashing, will assist consumers in making informed judgments. Ultimately, this will benefit the environment by discouraging companies from engaging in greenwashing by increasing consumer awareness. Fourth, this study highlights the influence of SBC on ESFBs. Although philanthropy has been extensively studied, the significance of SBC in the context of ESFBs cannot be overlooked. Companies that focus on ESFBs must consider their role in society and strategically utilize SBC, making it more than just a fashion or environmental strategy. Fifth, this study proposes that individuals who are more sensitive to the attention of others are more likely to engage in WOM marketing for ESFBs, with consequences for companies. Moreover, advertising campaigns that capitalize on the identity of individuals who have a strong connection to ESFBs have the potential to exert an effective influence. Lastly, companies that actively pursue social and economic sustainability, rather than environmental sustainability, can prevent consumers’ misunderstanding of greenwashing, especially if they actively implement other sustainability marketing strategies instead of emphasizing ambiguous environmental aspects. In addition, conspicuous consumption promotes social sustainability; therefore, it must be utilized.