Top of page

Collection Hannah Arendt Papers

Totalitarianism, the inversion of politics.

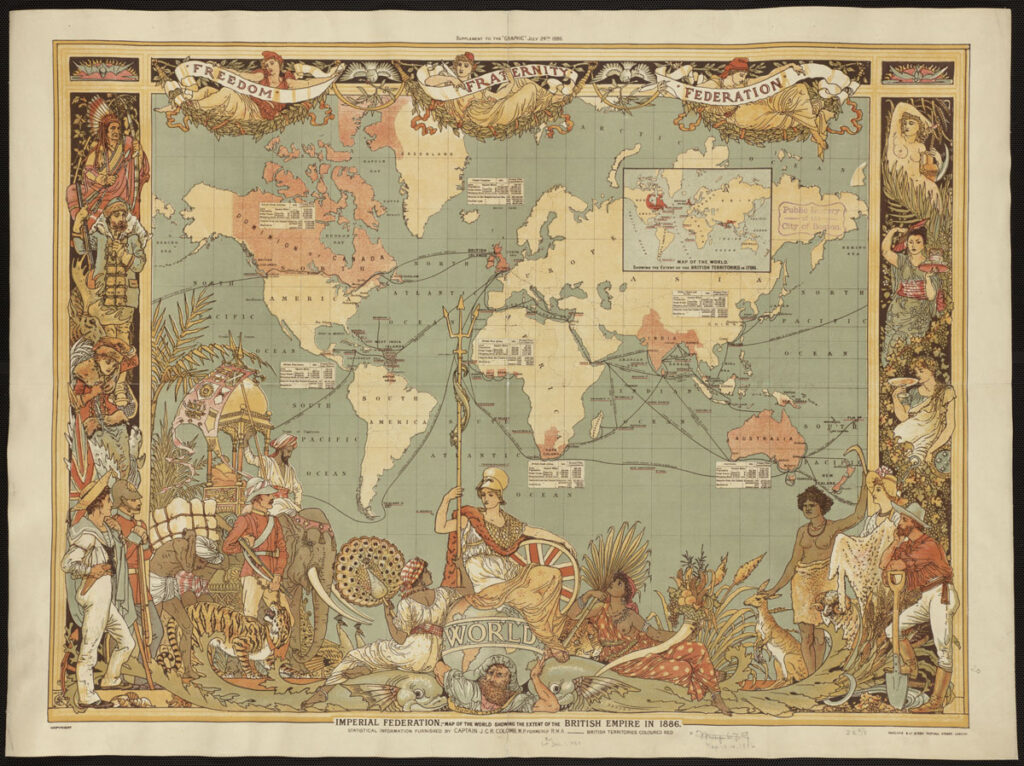

When Hannah Arendt published The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951, World War II had ended and Hitler was dead, but Stalin lived and ruled. Arendt wanted to give her readers a sense of the phenomenal reality of totalitarianism, of its appearance in the world as a terrifying and completely new form of government. In the first two parts of the book she excavated hidden elements in modern anti-Semitism and European imperialism that coalesced in totalitarian movements; in the third part she explored the organization of those movements, dissected the structure of Nazism and Stalinist Bolshevism in power, and scrutinized the "double claim" of those regimes "to total domination and global rule." Her focus, to be sure, is mainly on Nazism, not only because more information concerning it was available at the time, but also because Arendt was more familiar with Germany and hence with the origins of totalitarianism there than in Russia. She knew, of course, that those origins differed substantially in the two countries and later, in different writings, would undertake to right the imbalance in her earlier discussion (see "Project: Totalitarian Elements in Marxism").

The enormous complexity of The Origins of Totalitarianism arises from its interweaving of an understanding of the concept of totalitarianism with the description of its emergence and embodiment in Nazism and Stalinism. The scope of Arendt's conceptual objectives may be glimpsed in the plan she drew up for six lectures on the nature of totalitarianism delivered at the New School for Social Research in March and April of 1953 (see " The Great Tradition and the Nature of Totalitarianism "). The first lecture dealt with totalitarianism's "explosion" of our traditional "categories of thought and standards of judgment," thus at the outset stating the difficulty of understanding totalitarianism at all. In the second lecture she considered the different kinds of government as they were first formulated by Plato and then jumped many centuries to Montesquieu's crucial discovery of each kind of government's principle of action and the human experience in which that principle is embedded. In the third lecture she explicated three important distinctions: first, between governments of law and arbitrary power; secondly, between the traditional notion of humanly established laws and the new totalitarian concept of laws that govern the evolution of nature and direct the movement of history; and, thirdly, between "traditional sources of authority" that stabilize "legal institutions," thereby accommodating human action, and totalitarian laws of motion whose function is, on the contrary, to stabilize human beings so that the predetermined courses of nature and history can run freely through them. The fourth lecture addressed the totalitarian "transformation" of an ideological system of belief into a deductive principle of action. In the fifth lecture the basic experience of human loneliness in totalitarianism was contrasted with that of impotence in tyranny and differentiated from the experiences of isolation and solitude, which are essential to the activities of making and thinking but "marginal phenomena in political life." In the final lecture Arendt distinguished "the political reality of freedom" from both its "philosophical idea" and the "inherent 'materialism'" of Western political thought.

In addition to its complexity the stylistic richness of The Origins of Totalitarianism lies in its admixture of erudition and imagination, which is nowhere more manifest than in the particular examples by which Arendt brought to light the elements of totalitarianism. These examples include her devastating portrait of Disraeli and her tragic account of the "great" and "bitter" life of T. E. Lawrence; other exemplary figures are drawn from works of literature by authors such as Kipling and Conrad (see The Origins of Totalitarianism , chapter 7). A single, striking instance of the latter is Conrad's Heart of Darkness , which Arendt called "the most illuminating work on actual race experience in Africa," her emphasis clearly falling on the word "experience." Engaged in "the merry dance of death and trade," Conrad's imperialistic adventurers were in quest of ivory and entertained few scruples over slaughtering the indigenous inhabitants of "the phantom world of the dark continent" in order to obtain it. The subject of Conrad's work, in which the story told by the always ambiguous Marlow is recounted by an unnamed narrator, is the encounter of Africans with "superfluous" Europeans "spat out" of their societies. As the author of the whole tale as well as the tale within the tale, Conrad was intent not "to hint however subtly or tentatively at an alternative frame of reference by which we may judge the actions and opinions of his characters." 1 Marlow, a character twice removed from the reader, is aware that the "conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing." It is in the person of the "remarkable" and "eloquent" Mr. Kurtz that Marlow seeks the "idea" that alone can offer redemption: "An idea at the back of [the conquest], not a sentimental pretense but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea."

As Marlow's steamer penetrates "deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness" in search of Kurtz's remote trading station, Africa becomes increasingly "impenetrable to human thought." In a passage cited by Arendt, Marlow observes the Africans on the shore:

The prehistoric man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us--who could tell? We . . . glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be, before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand because we were too far and could not remember, because we were traveling in the night of the first ages, of those ages that are gone leaving hardly a sign--and no memories. . . . The earth seemed unearthly . . . and the men were . . . No, they were not inhuman. Well, you know, that was the worst of it--this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled and leapt and spun and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity--like yours--the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar.

The next sentence spoken by Marlow consists of one word, "Ugly," and that word leads directly to his discovery of Kurtz, the object of his fascination. He reads a report that Kurtz, who exemplifies the European imperialist ("All Europe contributed to [his] making"), has written to the "International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs." It is a report in the name of progress, of "good practically unbounded," and it gives Marlow a sense "of an exotic Immensity ruled by an August Benevolence." But at the bottom of the report's last page, "luminous and terrifying like a flash of lightning in a serene sky," Kurtz has scrawled "Exterminate all the brutes!" Thus racism is revealed as the "idea" of the mad Kurtz and the darkness of his heart becomes the counterpart of the not inhuman but "uncivilized" darkness of Africa. The horrific details follow, the decapitated heads of Africans stuck on poles, facing inward toward Kurtz's dwelling. Marlow rationalizes Kurtz's "lack of restraint": "the wilderness . . . had whispered to him things about himself which he did not know," a whisper that "echoed loudly within him because he was hollow at the core." It is questionable whether Marlow is less hollow when, at the end of the work, he attempts in "fright" to lie about Kurtz's last words, "The horror! The horror!" The experience of race is now complete; even the shadowy narrator of Marlow's story is left before "the heart of an immense darkness" in which the image of Kurtz's racism looms in the consciousness of Conrad's readers and of the world.

Arendt, however, is not saying that racism or any other element of totalitarianism caused the regimes of Hitler or Stalin, but rather that those elements, which include anti-Semitism, the decline of the nation-state, expansionism for its own sake, and the alliance between capital and mob, crystallized in the movements from which those regimes arose. Reflecting on her book in 1958 Arendt said that her intentions "presented themselves" to her "in the form of an ever recurring image: I felt as though I dealt with a crystallized structure which I had to break up into its constituent elements in order to destroy it." This presented a problem because she saw that it was an "impossible task to write history, not in order to save and conserve and render fit for remembrance, but, on the contrary, in order to destroy." Thus despite her historical analyses it "dawned" on her that The Origins of Totalitarianism was not "a historical . . . but a political book, in which whatever there was of past history not only was seen from the vantage point of the present, but would not have become visible at all without the light which the event, the emergence of totalitarianism, shed on it." The origins are not causes, in fact "they only became origins- antecedents--after the event had taken place." While analyzing, literally "breaking up," a crystal into its "constituent elements" destroys the crystal, it does not destroy the elements. This is among the fundamental points that Arendt made in the chapter written in 1953 and added to all subsequent editions of The Origins of Totalitarianism (see "Ideology and Terror: A Novel Form of Government"):

If it is true that the elements of totalitarianism can be found by retracing the history and analyzing the political implications of what we usually call the crisis of our century, then the conclusion is unavoidable that this crisis is no mere threat from the outside, no mere result of some aggressive foreign policy of either Germany or Russia, and that it will no more disappear with the death of Stalin than it disappeared with the fall of Nazi Germany. It may even be that the true predicaments of our time will assume their authentic form--though not necessarily the cruelest--only when totalitarianism has become a thing of the past.

According to Arendt the "disturbing relevance of totalitarian regimes . . . is that the true problems of our time cannot be understood, let alone solved, without the acknowledgment that totalitarianism became this century's curse only because it so terrifyingly took care of its problems" (see "Concluding Remarks" in the first edition of The Origins of Totalitarianism ). The rejection of the totalitarian answer to the question of race, for instance, does not solve but reveals the problem that arises when race is viewed as the origin of human diversity. Totalitarianism's destruction of naturally determined "inferior" races or historically determined "dying" classes leaves us on an overcrowded planet with the great and unsolved political perplexity of how human plurality can be conceived, of how historically and culturally different groups of human beings can live together and share their earthly home.

Defying classification in terms of a single academic discipline such as history, sociology, political science, or philosophy, The Origins of Totalitarianism presents a startling interpretation of modern European intellectual currents and political events. Still difficult to grasp in its entirety, the book's climactic delineation of the living dead, of those "inanimate" beings who experienced the full force of totalitarian terror in concentration camps, cut more deeply into the consciousness of some of Arendt's readers than the most shocking photographs of the distorted bodies of the already dead. Such readers realized that there are torments worse than death, which Arendt described in terms of the longing for death by those who in former times were thought to have been condemned to the eternal punishments of hell. She meant this vision of hell to be taken literally and not allegorically, for although throughout the long centuries of Christian belief men had proved themselves incapable of realizing the city of God as a dwelling place for human beings, they now showed that it was indeed possible to establish hell on earth rather than in an afterlife.

Arendt added totalitarianism to the list of kinds of government drawn up in antiquity and hardly altered since then: monarchy (the rule of one) and its perversion in tyranny; aristocracy (the rule of the best) and its corruption in oligarchy or the rule of cliques; and democracy (the rule of many) and its distortion in ochlocracy or mob rule. The hallmark of totalitarianism, a form of rule supported by "superfluous" masses who sought a new reality in which they would be recognized in public, was the appearance in the world of what Arendt, in The Origins of Totalitarianism , called radical and absolute evil. Totalitarian regimes are not the "opposite" of anything: the absence of their opposite may be the surest way of seeing totalitarianism as the crisis of our times.

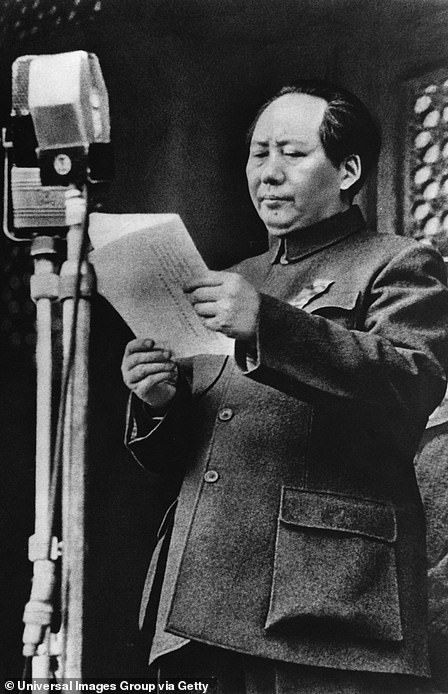

Totalitarianism has been identified by many writers as a ruthless, brutal, and, thanks to modern technology, potent form of political tyranny whose ambitions for world domination are unlimited. Disseminating propaganda derived from an ideology through the media of mass communication, totalitarianism relies on mass support. It crushes whoever and whatever stands in its way by means of terror and proceeds to a total reconstruction of the society it displaces. Thus a largely rural and feudal Russian Empire, under the absolutist rule of czars stretching back to the fifteenth century, was transformed first by Lenin after the October Revolution of 1917 and then by Stalin into an industrialized Union of Soviet Socialist Republics; a Germany broken after its defeat in World War I was mobilized and became the conqueror of most of Europe in the early 1940s less than a decade after Hitler's assumption of power; and in China the People's Republic, by taking the Great Leap Forward in 1958 followed by the Cultural Revolution beginning in 1966 and ending with Mao Zedong's death in 1976, expunged much of what remained of a culture that had survived for more than three thousand years.

Such achievements require total one-party governmental control and tremendous human sacrifice; the elimination of free choice and individuality; the politicization of the private sphere, including that of the family; and the denial of any notion of the universality of human rights. In diverse areas of the world where political freedom and open societies have been virtually unknown or untried, totalitarian methods have been seen to exert an ongoing attraction for local elites, warlords, and rebels. Such well-known phenomena as "brain washing," "killing fields," "ethnic cleansing," "mass graves," and "genocide," accounting for millions of victims and arising from a variety of tribal, nationalist, ethnic, religious, and economic conditions, have been deemed totalitarian in nature. Totalitarianism, moreover, is frequently employed as an abstract, vaguely defined term of general opprobrium, whose historical roots are traced to the political thought of Marx or in some instances to Rousseau and as far back as Plato. But because of what has been called its "inefficiency," which Arendt attributes to its "contempt for utilitarian motives," totalitarianism rarely occurs in the political analyses of those who consider the function of politics in terms of "utilitarian expectations." Recently, however, prominent political theorists such as Margaret Canovan in England and Claude Lefort in France have seen in the decline of communism and the diminished intensity of left and right ideological debates an opportunity for an impartial and rigorous reassessment of the concept of totalitarianism. Although Arendt may have experienced a similar need to understand Nazism after its defeat in World War II, for her impartiality was the condition of judging the irreversible catastrophe of totalitarianism as "the central event of our world."

When Arendt noted that causality, the explanation of an event as being determined by another event or chain of events which leads up to it, "is an altogether alien and falsifying category in the historical sciences," she meant that no historical event is ever predictable. Although with hindsight it is possible to discern a sequence of events, there is always a "grotesque disparity" between that sequence and a particular event's significance. What the principle of causality ignores or denies is the contingency of human affairs, i.e., the human capacity to begin something new , and therefore the meaning and "the very existence" of what it seeks to explain (see " The Difficulties of Understanding " and " On the Nature of Totalitarianism "). It is not the "objectivity" of the historical scientist but the impartiality of the judge who perceives the existence and discerns the meaning of events, of which the antecedents can then be told in stories whose beginnings are never causes and whose conclusions are never predetermined. 2 The rejection of causality in history and the insistence on the contingency, unpredictability, and meaning of events brought about not by nature but by human agency inform Arendt's judgment of the incomprehensible and unforgivable crimes of totalitarianism. In regard to such crimes the old saying " tout comprendre c'est tout pardonner " (to understand everything is to forgive everything)--as if to understand an offense, say by its psychological motive, were to excuse it--is a double "misrepresentation" of the fact that understanding seeks reconciliation. What may be possible is reconciliation to the world in which the crimes of totalitarianism were committed (see " The Difficulties of Understanding "), and a great part of Arendt's work on totalitarianism and thereafter is an effort to understand that world. But it should be noted that the outrage that pervades her judgment is not a subjective emotional reaction foisted on a purportedly "value free" scientific analysis. 3 Her anger is impartial in her judgment of a form of government that defaced the world and "objectively" belongs to that world on whose behalf she judged totalitarianism for what it was and what it meant.

Even before she wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism Arendt spoke of the desperate need to tell the "real story of the Nazi-constructed hell":

Not only because these facts have changed and poisoned the very air we breathe, not only because they now inhabit our dreams at night and permeate our thoughts during the day -- but also because they have become the basic experience and the basic misery of our times. Only from this foundation, on which a new knowledge of man will rest, can our new insights, our new memories, our new deeds, take their point of departure. (See "The Image of Hell.")

The beginning called for here, if there were to be one, will arise from individual acts of judgment by men and women who know the nature of totalitarianism and agree that, for the sake of the world, it must not occur again--not only in the forms in which it has already occurred, which may be unlikely, but in any form whatsoever.

The significance of the story Arendt went on to tell and retell lies entirely in the present, and she was fully aware that her "method," a subject which she was always loath to discuss, went against the grain not only of political and social scientists but also, more importantly to her, of those reporters, historians, and poets who in distinct ways seek to preserve, in or out of time, what they record, narrate, and imagine. Reflecting later on the moment in 1943 when she first learned about Auschwitz, Arendt said: " This ought not to have happened ." That is no purely moral "ought" based in ethical precepts, the voice of conscience, or immutable natural law, but rather as strong as possible a statement that there was something irremissibly wrong with the human world in which Auschwitz could and did happen.

Reconciliation to that world requires understanding only when totalitarianism is judged , not by subsuming it under traditional moral, legal, or political categories but by recognizing it as something unprecedented, odious, and to be fought against. Such judgment is possible for beings "whose essence is beginning" (see " The Difficulties of Understanding ") and makes reconciliation possible because it strikes new roots in the world. Judgment is "the other side of action" and as such the opposite of resignation. It does not erase totalitarianism, for then, thrown backward into the past, the historical processes that did not cause but led to totalitarianism would be repeated and "the burden of our time" reaccumulated; or, projected forward into the future, a never-never land ignorant of its own conditions, the human mind would "wander in obscurity." 4 A quotation from Karl Jaspers that struck Arendt "right in the heart" and which she chose as the epigraph for The Origins of Totalitarianism stresses that what matters is not to give oneself over to the despair of the past or the utopian hope of the future, but "to remain wholly in the present." Totalitarianism is the crisis of our times insofar as its demise becomes a turning point for the present world, presenting us with an entirely new opportunity to realize a common world, a world that Arendt called a "human artifice," a place fit for habitation by all human beings.

Arendt's papers provide many interesting opportunities to study the development of her thought. For instance, in "The Difficulties of Understanding," written in the early 1950s, judgment is conjoined with understanding. As late as 1972, in impromptu remarks delivered at a conference devoted to her work, she associated it with the activity of thinking. But Arendt was working her way toward distinguishing judgment as an independent and autonomous mental faculty, "the most political of man's mental abilities" (see " Thinking and Moral Considerations "). Although the activities of understanding and thinking reveal an unending stream of meanings and under specific circumstances may liberate the faculty of judgment, the act of judging particular and contingent events differs from them in that it preserves freedom by exercising it in the realm of human affairs. That distinction is critical for her view of history in general and totalitarianism in particular and has been adhered to in this introduction.

Arendt's judgment of totalitarianism must first and foremost be distinguished from its commo identificatio as a insidious form of tyranny. Tyranny is a ancient, originally Greek form of government which, as the tragedy of Oedipous Tyrannos and the historical examples of Peisistratus of Athens and Periandros of Corinth demonstrate, was by no means necessarily against the private interests and initiatives of its people. As a form of government tyranny stands against the appearance i public of the plurality of the people, the condition, according to Arendt, i which political life and political freedom--"public happiness," as the founders of the America republic named it--become possible and without which they do not.

I a tyrannical political realm, which ca hardly be called public, the tyrant exists i isolatio from the people. Due to the lack of rapport or legal communicatio betwee the people and the tyrant, all actio i a tyranny manifests a "moving principle" of mutual fear: the tyrant's fear of the people, o one side, and the people's fear of the tyrant, or, as Arendt put it, their "despair over the impossibility" of joining together to act at all, o the other. It is i this sense that tyranny is a contradictory and futile form of government, one that generates not power but impotence. Hence, according to Montesquieu, whose acute observations Arendt drew o i these matters, tyranny (which he does not eve bother to distinguish from despotism, malevolent by definition, since he is concerned with public rather tha private freedom) is a form of government that, unlike constitutional republics or monarchies, corrupts itself, cultivating withi itself the seeds of its ow destructio (see " On the Nature of Totalitarianism "). Therefore, the essential impotence of a tyrannically ruled state, however flamboyant and spectacular its dying throes, and whether or not it is despotic, and regardless of the cruelty and suffering it may inflict o its people, presents no menace of destructio to the world at large.

I their early revolutionary stages of development, to be sure, and whenever and wherever they meet opposition, totalitaria movements employ tyrannical measures of force and violence, but their nature differs from that of tyrannies precisely i the enormity of their threat of world destruction. That threat has ofte bee thought possible and explained as the total politicalizatio of all phases of life. Arendt saw it, and this is crucial, as exactly the opposite: a phenomeno of total depoliticalizatio (i Germa Entpolitisierung [see " Freiheit und Politik "]) that appeared for the first time i the regimes of Stali after 1929 and Hitler after 1938. Totalitarianism's radical atomizatio of the whole of society differs from the political isolation, the political "desert," as Arendt termed it, of tyranny. It eliminates not only free action, which is political by definition, but also the element of action, that is, of initiation, of beginning anything at all, from every huma activity. Individual spontaneity--i thinking, i any aspiration, or i any creative undertaking--that sustains and renews the huma world is obliterated i totalitarianism. Totalitarianism destroys everything that politics, eve the circumscribed political realm of a tyranny, makes possible.

I totalitaria society freedom, private as well as public, is nothing but a illusion. As such it is no longer the source of fear that i tyranny manifests itself not as a emotio but as the principle of the tyrant's actio and the people's non-action. Whereas tyranny, pitting the ruler and his subjects against each other, is ultimately impotent, totalitarianism generates immense power, a new sort of power that not only exceeds but is different i kind from coercive force. The dynamism of totalitarianism negates the fundamental conditions of huma existence. I the name of ideological necessity totalitaria terror mocks the appearance and also the disappearance, both the lives and the deaths, of distinct and potentially free me and women. It mocks the world that only a plurality of such individuals ca continuously create, hold i common, and share. It mocks eve the earth insofar as it is their natural home. The profound paradox that lies betwee the totalitaria belief that the eradicatio of every sig of humanity, of huma freedom, of all spontaneity and beginning, is necessary , and the fact that its possibility is itself something new brought into the world by huma beings is the core of what Arendt strove to comprehend.

According to Arendt the nature of totalitarianism is the "combination" of "its essence of terror and its principle of logicality" (see " On the Nature of Totalitarianism "). As "essence" terror must be total, more tha a means of suppressing opposition, more tha a extreme or insane vindictiveness. Total terror is, i its ow way, rational: it replaces, literally takes the place of, the role played by positive laws i constitutional governments. But the result is neither lawless anarchy, the war of all against all, nor the tyrannical abrogatio of law. Arendt pointed out that just as a government of laws would become "perfect" in the absence of transgressions, so terror "rules supreme when nobody any longer stands in its way" (see The Origins of Totalitarianism , chapter 12). Just as positive laws in a constitutional government seek to "translate and realize" higher transcendent laws, such as God's commandments or natural law, so totalitarian terror "is designed to translate into reality the law of movement of history or nature," not in a limited body politic, but throughout mankind.

If totalitarianism were perfected, if the entire plurality of human beings were to become one with the sole aim of accelerating "the movement of nature or history," then its essence of terror would suffice as its principle of motion (see The Origins of Totalitarianism , chapter 13). So long as totalitarianism exists in a non-totalitarian world, however, it needs the processes of logical or dialectical deduction to coerce the human mind into "imitating" and becoming "integrated" into the "suprahuman" forces of nature and history. In other words, the logic of the idea of an ideology forces the mind to move as inevitably as natural and historical processes themselves move, and against this movement "nothing stands but the great capacity of men" to interrupt those processes by starting "something new." It is not the political isolation that always prevents action, however, but the loneliness of socially uprooted, "superfluous" human beings, their loss of common sense, the sense of community and communication, which attracts them to logical explanations of all that has happened, is happening, and ever will happen. Thereby relieved of any responsibility for the course of the world, world-alienated masses are unwittingly, beneath the crust of their lives, prepared for totalitarian organization and, ultimately, domination.

Arendt concluded that Hitler and Stalin discovered that the eradication of the unpredictability of human affairs, of human freedom, and of human nature itself is possible in "the true central institution of totalitarian organizational power," the concentration camp. In concentration camps the combination of the practice of terror with the principle of logicality, which is the nature of totalitarianism, "resolves" the conflict in constitutional governments between legality and justice by ridding human beings of individual consciences and making them embodiments of the laws governing the motion of nature and history. On the one hand, in the world view of totalitarianism the freedom of human beings is inconsequential to "the undeniable automatism" of natural and historical processes, or at most an impediment to their freedom. On the other, when "the iron band of terror" destroys human plurality, so totally dominating human beings that they cease to be individuals and become a mere mass of identical, interchangeable specimens "of the animal-species man," that terror provides the movement of nature and history with "an incomparable instrument" of acceleration. Terror and logicality welded together equip totalitarian regimes with unprecedented power to dominate human beings. How totalitarian systems accomplish their inversion of political life, above all how they set about destroying human conscience and the plurality of unique human individuals, staggers the imagination and confounds the faculty of understanding.

By Jerome Kohn, Trustee, Hannah Arendt Bluecher Literary Trust

- As Chinua Achebe says he ought to have done (C. Achebe, "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness" in Heart of Darkness , ed. Robert Kimbrough, 3rd ed. [New York, 1998], 256). [ Return to text ]

- The concept of history derives from the Greek verb historein , to inquire, but Arendt found "the origin of this verb" in the Homeric histor , the first "historian," who was a judge (see Thinking , "Postscriptum"; cf. Illiad XVIII, 501). [ Return to text ]

- Such a view, as Arendt points out, accurately describes many historical accounts of anti-Semitism, none more so than D. J. Goldhagen's Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust (New York, 1996). [ Return to text ]

- The Burden of Our Time is the title of the first British edition of The Origins of Totalitarianism (London, 1951). Arendt frequently cited Tocqueville's remark in the last chapter of Democracy In America : "As the past has ceased to throw its light upon the future, the mind of man wanders in obscurity" (see " Philosophy and Politics: The Problem of Action after the French Revolution " and Between Past and Future , "Preface" ). [ Return to text ]

12 October 2023

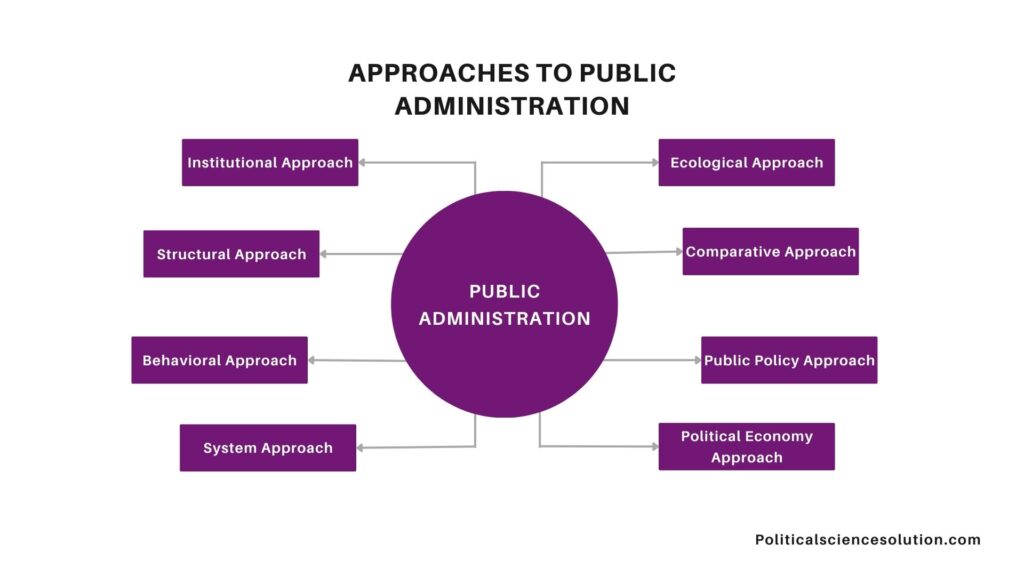

politicalsciencesolution.com

Political Regimes: Democratic and Non Democratic Systems of Government

Democratic government , Non Democratic System , Political Philosophy , Political Regimes , Political Science , Politics , Society

Political regimes encompass democratic and non-democratic systems, profoundly influencing a nation’s governance, rights, and well-being. This exploration will illuminate their fundamental differences and impact on a country’s trajectory.

Introduction

Political regimes play a pivotal role in shaping the governance, power distribution, and overall dynamics of a nation. Roy Macridis defines “Political regime as the embodiment of a set of rules, procedures and understandings that formulate the relationship between the governors and the governed”. Political Regimes are the systems that define how a country is run, and they come in two primary forms: democratic and non-democratic. These regimes represent fundamentally distinct approaches to governance, each with its own set of principles, values, and practices that have far-reaching implications for the rights, freedoms, and well-being of a nation’s citizens.

In this exploration, we will delve into the fundamental differences between democratic and non-democratic political regimes, shedding light on the various characteristics and features that define each system, and how they influence the course of a nation’s history, development, and the quality of life for its inhabitants.

Table of Contents

The fundamental meaning of democracy.

The word ‘democracy’ has its origins in two Greek words: ‘demos,’ meaning people, and ‘kratia,’ meaning rule. Thus, in its literal sense, democracy is defined as the ‘rule of the people.’ Abraham Lincoln’s famous quote, “government of the people, by the people, and for the people,” succinctly captures this idea. A.V. Dicey’s definition states that democracy is a form of government where a significant portion of the entire nation constitutes the governing body. Lord James Bryce further clarifies that democracy implies that the ruling power of a state is vested not in a particular class but in the community as a whole.

The Evolution of Democratic Forms

The initial form of democracy involved free and adult males in city-states participating directly in political affairs. This direct form of democracy is often considered the purest. However, as societies grew in complexity and size, direct democracy became impractical. The Glorious Revolution in England, the American Declaration of Independence, and the French Revolution led to the emergence of indirect or representative democracy. This form of democracy relies on elected representatives to express the will of the public. Thus, John Stuart Mill calls it ‘representative form of govt.’ and Henry Maine has called it a ‘popular govt.’

Participation and Elections are Fundamental to democracy, they empower citizens to influence policy and choose their representatives. While most democracies are representative, some, like Switzerland and the United States, use direct democracy devices such as referendums, initiatives, recalls, and plebiscites.

The four devices of direct democracy are:

a) Referendum is a procedure whereby a proposed legislation is referred to the electorate for settlement by their direct votes.

b) Initiative is a method by means of which the people can propose a bill to the legislature for enactment.

c) Recall is a method by which the voters can remove a representative or an officer before the expiry of his term, when he fails to discharge his duties properly.

d) Plebiscite is a method of obtaining the opinions of people on any issue of public importance. It is generally used to solve territorial disputes.

Additionally, Landszemeinde is also an instrument of direct democracy. It is primarily used in Switzerland. It is an assembly of all the citizens of the cantons.

Democracy assumes individuals are free, with clear limitations and responsibilities defining their interaction with the state. All democratic regimes have a constitution that establishes the functions, powers, and responsibilities of state organs, including the legislature, executive, and judiciary.

Types of Democracy

In terms of operations, democracy is either direct or indirect, but in respect of its nature, it has many forms such as Liberal Democracy, Electoral, Social, Majoritarian, participatory etc.

Liberal Democracy

Liberal democracy, often synonymous with Western societies, boasts several distinguishing features. It operates on the principle of limited government, advocating for individual liberty and rights with minimal state intervention. It perceives government as a necessary evil, recognizing the potential for tyranny, and thus, incorporates checks and balances such as a constitution, the rule of law, an independent judiciary, and the separation of powers. Liberal democracies typically coexist with capitalist economic systems, emphasizing the rule of law.

Furthermore, these democracies are characterized by a robust and critical civil society , a multi-party political system, and a presence of numerous interest and pressure groups. They prioritize free and fair elections, ensuring political equality , and provide mechanisms for the accountability of representatives to the people. Liberal democracy is essentially a blend of elite rule and popular participation, fostering political pluralism and open competition between various political ideologies, social movements , and political parties .

Radical or Social Democracy: Focusing on Societal Welfare

Radical or social democracy follows the same democratic mechanisms as liberal democracy but places a stronger emphasis on societal interests over individual concerns. While individuals have the right to vote, reasonable restrictions are imposed on economic freedom to combat poverty and exploitation at the societal level. Social democracy aims to establish a ‘welfare state’ where the government plays a more significant role in the development of society and its people.

Presidential and Parliamentary Forms of Democracy

The nature of executive authority in a democracy can take one of two primary forms: presidential or parliamentary. In a presidential democracy, the president serves as both the head of state and the head of government. The United States serves as a prime example of a presidential system, where the president fulfills multiple roles, including Commander-in-Chief, foreign policy negotiator, party leader, and spokesperson for the public interest. The executive branch, led by the president, operates independently, ensuring a total separation of powers among the three branches of government.

Conversely, in a parliamentary democracy, the legislature holds supreme power to make laws, control finances, and appoint or dismiss the head of government, typically the Prime Minister and their ministers. In practice, the cabinet and the Prime Minister have evolved into quasi-independent policy-making entities. Parliamentary systems feature both nominal and real executives, adhering to the principles of majority party rule and collective responsibility of the executive to the legislature. The cabinet, in such systems, holds the entirety of executive power.

It’s important to note that some countries, like France , adopt a semi-presidential and semi-parliamentary regime. In this scenario, the French president holds supreme executive power in reality, with a cabinet responsible for conducting the nation’s policies before the parliament.

Additional Forms of Democracy

In addition to the above forms, there are other types of democracy worth mentioning:

- Electoral Democracy: This type of representative democracy is based on elections and electoral votes, characteristic of modern Western democracies.

- Participatory Democracy: It involves increased citizen participation in decision-making and offers greater political representation than traditional representative democracy. It empowers citizens to have more control over the decisions made by their representatives.

- Majoritarian Democracy: This form of democracy relies on majority rule, often criticized for excluding the voice of the minority. It carries the risk of turning into a ‘tyranny of the majority.’ In response, consensus democracy emphasizes rule by as many people as possible to ensure inclusivity and prevent the dominance of the majority.

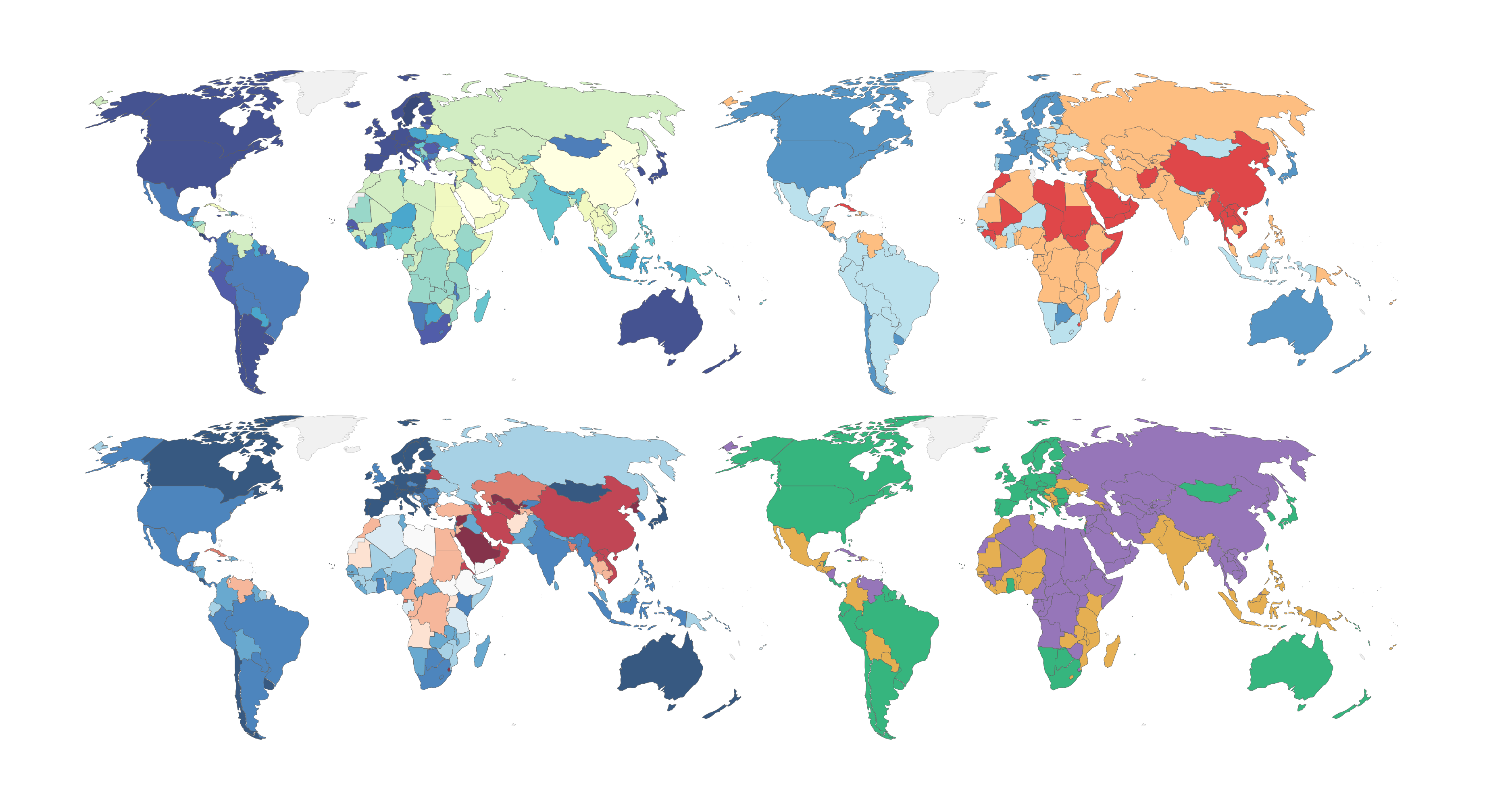

Three Waves of Democratization by Samuel Huntington

In his book, The Third Wave: Democratization in the late Twentieth Century 1991 , S.P Huntington has talked about the three waves in the world that democratized the different types of countries in the world i.e. it led to the popularization of features of democracy in different parts of the world in three waves/stages.

Democratization waves have been linked to sudden shifts in the distribution of power among the great powers, which creates openings and incentives to introduce sweeping domestic reforms. Let’s look at them one by one:

First Wave: The initial wave of democracy, spanning from 1828 to 1926, marked the emergence of democratic principles. This wave began in the early 19th century when suffrage was extended to the majority of white males in the United States. Following this, countries like France, Britain, Canada, Australia, Italy, and Argentina adopted democratic systems, with a few more nations joining their ranks before 1900. The peak of this first wave occurred after the disintegration of empires like Russia, Germany, Austria, and the Ottoman Empire in 1918. At this point, the world witnessed the establishment of 29 democracies in the aftermath of World War I. However, this wave faced a setback in 1922 when Benito Mussolini came to power in Italy, initiating a reversal.

The collapse of the first wave was mainly felt by newly formed democracies, which struggled against the rise of expansionist communist, fascist, and militaristic authoritarian or totalitarian movements that systematically opposed democratic ideals. The nadir of the first wave was reached in 1942 when the number of democracies worldwide dwindled to a mere 12.

Second Wave: The second wave of democracy commenced following the Allied victory in World War II and reached its zenith nearly two decades later in 1962, with 36 recognized democracies across the globe. However, the second wave began to recede at this point, and the total count decreased to 30 democracies between 1962 and the mid-1970s. Yet, this “flat line” was a temporary phase, as a new surge was on the horizon with the advent of the third wave. It’s worth noting that India was part of the second wave .

Third Wave: The third wave of democracy, initiated in 1974 with the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, encompassed significant democratic transitions. This wave included historic transitions to democracy in Latin America during the 1980s, as well as in Asia-Pacific countries such as the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan from 1986 to 1988. It further extended to Eastern Europe following the collapse of the Soviet Union and encompassed sub-Saharan Africa, beginning in 1989. In Latin America, only Colombia, Costa Rica, and Venezuela had achieved democracy by 1978, while Cuba and Haiti remained under authoritarian rule by 1995, as this wave swept across a total of twenty countries.

Samuel Huntington pointed out that three-fourths of the new democracies that emerged in these waves were predominantly Roman Catholic. Most Protestant countries had already embraced democratic governance. Huntington emphasized the significance of the Vatican Council of 1962, which transformed the Catholic Church from a defender of the established order into an opponent of totalitarianism.

Overall, Democratic regimes are multifaceted, evolving with time and adapting to the complexities of society. The essence of democracy lies in the empowerment of the people and the rule of law. The different forms of democracy, including liberal, social, and majoritarian, cater to various societal needs and values. Understanding the waves of democracy, as described by Samuel Huntington, provides insights into the global progression of democratic values. In an ever-changing world, the essence of democracy remains constant: government for and by the people.

Non-Democratic Regimes

In the ever-evolving landscape of global politics, non-democratic regimes have played a significant role. These regimes, including totalitarianism, authoritarianism, patrimonialism, military dictatorship, and fascism, differ in their characteristics, power structures, and ideologies.

Totalitarian Regimes: The Power of Ideology

Totalitarian regimes are characterized by their unwavering commitment to a specific ideology. The central idea behind these regimes is to tightly organize the general public in the name of their ideology and disseminate it to gain complete control. Typically, they operate under a single-party system led by an all-powerful leader. The state monopolizes mass communication and armed forces while controlling all aspects of economic life.

Two prominent categories of totalitarian regimes exist: communist totalitarian regimes (like the former Soviet Union) and non-communist totalitarian regimes (such as Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy). Common features shared by totalitarian and authoritarian regimes include concentrated political power, a lack of accountability, disregard for the rule of law, and limited attention to individual rights. To maintain control, these regimes employ various tactics, including suppressing interests and associations, utilizing police forces, and establishing new institutions to control societal forces.

Authoritarian Regimes: A Wide Spectrum of Control

Approximately half of the world’s political regimes fall under authoritarianism. These regimes vary from personal regimes (e.g., Saudi Arabia) to single-party regimes and bureaucratic and military regimes. Centralized control and repressive mechanisms are key features, with the military often wielding significant influence. These governments are not constitutionally responsible to the people, who have little to no role in selecting their leaders. Individual freedom is often restricted, and political rights are either nominal or non-existent.

Authoritarian regimes may be institutionalized or legitimate, with an absence of a unifying ideology to mobilize the masses. The creation of critical opinions and interest and pressure groups is discouraged.

Four types of authoritarian regimes exist: tyrannies, dynastic regimes, military regimes, and single-party regimes.

Patrimonialism: Rule by Personal Power

This form of government was first described by Max Weber in his book “Economy and Society” written in 1922. Patrimonialism as he described is a form of political organization where authority is primarily based on the personal power of a ruler. This ruler may act alone or with the help of a powerful elite group. The legal authority of the ruler is largely unchallenged, and the entire government authority is treated as privately appropriated economic advantages.

These autocratic or oligarchic regimes typically exclude lower, middle, and upper classes from power. Military loyalty is directed toward the leader rather than the nation.

Military Dictatorship

Military dictatorship is a form of political organization where the military holds substantial control over political authority and institutions. Typically, the dictator is a high-ranking defense official. These regimes often emerge through coups d’état, forcibly overthrowing existing governments.

Military rule can be direct or indirect, with some pseudo democratic countries witnessing military control despite democratic processes. Notable examples include Argentina, Pakistan, Brazil, Peru, and others.

Bureaucratic Authoritarianism

Guillerno O’Donnell , the famous political scientist from Argentina introduced the concept of Bureaucratic Authoritarianism. This type of Government is characterized by a powerful group of technocrats using the state apparatus to rationalize and develop the economy. This form of rule was prevalent in South America during the 1960s and 1980s. Leadership is often dominated by individuals who rose to prominence through bureaucratic careers.

Decision-making in these regimes is typically technocratic, accompanied by intense repression. The emergence of bureaucratic authoritarianism challenged the idea that socioeconomic modernization would support democracy.

Fascism

Fascism is an ultra-nationalistic and authoritarian ideology characterized by dictatorial power, suppression of opposition, regimentation of society, and contempt for democracy and liberalism . It glorifies a single leader or ideology, promoting extreme militaristic nationalism and the rule of elites.

Fascist regimes seek to create a ‘people’s community’ in which individual interests are subordinated to the nation’s good. These regimes are marked by a strong belief in the authority of the state. The main authority meaning of Fascism originates from Benito Mussolini , the organizer of fascism, in which he traces three standards of a rightist theory:” Everything in the state”, “Nothing outside the state” and “Nothing against the state”.

Opposition to Marxism and parliamentary democracy is fundamental, and they support corporatism . The fascist economic theory corporatism called for organizing each of the major sectors of industry, agriculture, the professions, and the arts into state- or management controlled trade unions and employer associations, or “corporations,” each of which would negotiate labor contracts and working conditions and represent the general interests of their professions in a larger assembly of corporations, or “corporatist parliament.” Corporatist institutions would replace all independent organizations of workers and employers, and the corporatist parliament would replace, or at least exist alongside, traditional representative and legislative bodies.

In conclusion, the choice between democratic and non-democratic political regimes has profound and lasting effects on the destiny of a nation and the lives of its people. Understanding the distinctions between these systems is crucial for individuals, societies, and the global community as a whole, as it enables us to appreciate the values, principles, and consequences associated with the governance of nations, and encourages informed discussions on the future of political systems.

Regionalism in India: A Comprehensive Examination

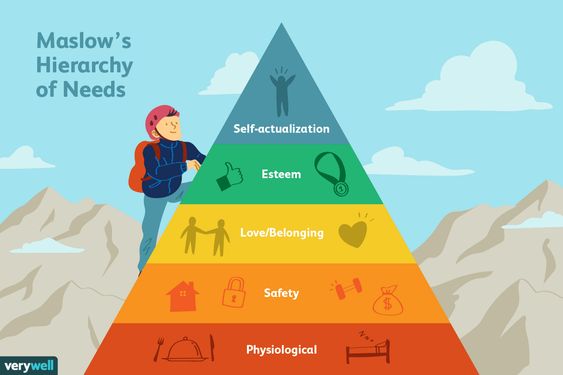

Language and identity politics in india: exploring the complex interplay, religion and identity politics in india, tribal politics and movements, dalit movements, latest articles, caste-based identity politics in india, reorganization of states in india, political parties in india, labor movements, farmers’ movements in india, women’s movements in india: a holistic exploration, civil society in india, new economic policy , five year plans: blueprints for india’s economic development, india and sadc (south african development community), sovereignty, the arctic council: navigating cooperation in a changing arctic landscape, the new development bank: fostering sustainable development and multilateral cooperation, the new international economic order (nieo): a vision for global economic justice in the 1970s, the bretton woods system: architectural pillar of post-war economic order, the international criminal court: a comprehensive overview and recent developments, regional comprehensive economic partnership (rcep): a landmark trade agreement shaping the asian economic landscape, the permanent court of arbitration: a pillar of international dispute resolution, human rights: from origins to evolution and beyond, international terrorism: origins, characteristics, and in-depth analysis of terrorism types, migration: a comprehensive exploration, opec: managing global oil supply for economic stability, brics: forging a new path in global politics and economics, “india and the gulf cooperation council: nurturing a comprehensive partnership”, world trade organization: a comprehensive exploration of structure, functions, and recent milestones”, world health organization’s (who) foundations and functions, power: a thorough examination of its definition and constituent elements, security in international relations, important international war treaties and agreements, structural marxism in the international arena, social constructivism in international relations, postmodernism in international relations, feminist perspectives in international relations, idealism in international relations: a vision for transformative global governance, nafta: the evolution and criticisms of north american economic integration, raisina dialogue: navigating global challenges through diplomacy and discourse, shanghai cooperation organization (sco): a comprehensive exploration of its evolution, structures, and global impact, african union: shaping unity, prosperity, and progress across the continent, roads to resilience: navigating the bbin initiative for seamless connectivity in south asia, the quadrilateral security dialogue (quad), gujral doctrine: india’s approach to neighboring relations, india’s strategic evolution from look east to act east policy, bimstec: a comprehensive exploration of regional integration and cooperation, indo-russian relations: a nuanced exploration of a time-tested alliance, cold war: a detailed exploration of political complexities from inception to resolution, world bank: components, functions, and global influence, international monetary fund (imf), state: definition, history, figures & facts, the united nations: quest for global peace and cooperation, european union: origins, structures, and achievements, india-eu relations, asean: unity, collaboration, and regional prosperity, south asian association of regional cooperation (saarc), india’s nuclear policy: historical evolution, strategic framework, and global implications, india-us relations, india – china relations, non-alignment movement: historical roots, objectives, and global significance, neoliberalism in international relations, realism and neo-realism in international relations: an in-depth exploration, india’s foreign policy: a comprehensive exploration, m.n. roy: a revolutionary visionary shaping india’s destiny, feminism: from origins to the third wave, marxism: a dive into its origins and streams, liberalism: from individualism to democracy, rights: meaning, types, generations and theories, right to information act: a comprehensive overview, social movements: types and stages, constitutionalism: comparative study of constitutions around the world, dependency theory: theory of underdevelopment, modernization theory: western approach to development, nationalism: european and non-european, colonialism and decolonization: a historical overview, motivation-hygiene theory by frederick herzberg: understanding employee satisfaction and dissatisfaction, the evolution of development administration: from post-colonial aspirations to neoliberal reforms, the bargaining approach to decision-making by charles lindblom, bureaucratic theory by max weber : structure, function, and criticisms, diverse approaches of public administration, public and private administration: differences and similarities, john rawls: architect of justice and fairness, mary wollstonecraft: pioneer of feminism and women’s rights, mao zedong: the revolutionary leader of communist china, antonio gramsci: the revolutionary thinker who redefined marxism and cultural hegemony, karl marx: class struggle, historical materialism and communism, frantz fanon: decolonization, identity, and liberation, hannah arendt: insights into politics, totalitarianism, and human freedom, john locke: the philosopher of individual rights and enlightenment thinker, machiavelli: doctrine of statecraft, dual morality, and the role of the prince, aristotle: a complete overview of his life, work, and philosophy, plato: exploring the philosopher king, educational theory, and communism, public administration: understanding its nature, scope, and evolution, scientific management theory by f.w taylor : optimizing efficiency and productivity in the workplace, hierarchy of needs by abraham maslow: understanding human motivation and fulfillment, human relations theory by elton mayo, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You cannot copy content of this page

Featured articles

28 April 2024

24 April 2024

23 April 2024

22 April 2024

21 April 2024

22 March 2024

20 March 2024

15 March 2024

29 February 2024

27 February 2024

19 February 2024

29 November 2023

21 November 2023

20 November 2023

8 November 2023

31 October 2023

26 October 2023

18 October 2023

17 October 2023

16 October 2023

14 October 2023

6 October 2023

5 October 2023

4 October 2023

2 October 2023

1 October 2023

30 September 2023

29 September 2023

27 September 2023

26 September 2023

25 September 2023

21 September 2023

18 September 2023

15 September 2023

18 July 2023

30 June 2023

28 June 2023

25 June 2023

10.4 Advantages, Disadvantages, and Challenges of Presidential and Parliamentary Regimes

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare and contrast the advantages and disadvantages of parliamentary and presidential regimes.

- Distinguish between government stability and policy stability.

- Explain what a coalition government is and how these governments potentially work within each regime.

- Define political gridlock and political polarization and explain how they may impact public policy.

- Summarize how minor parties are more viable in a parliamentary regime than they are in a presidential regime.

Each system has its advantages and disadvantages. This section will primarily focus on the systems’ effects on policy: stability, coalition governments, divided government, and representation of minor parties.

| Presidentialism | Parliamentarianism | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Presidents can claim a mandate and take the lead in setting the legislative agenda. | If there is divided government, it can lead to gridlock. | A unified government enables the quick enactment of policies. | Drastic policy change is possible from one government to the next. |

| During a time of crisis, a president may be able to act quickly. | A president may blame the legislature for policy failures. | A clear line of policy-making responsibility helps define accountability. | Coalition governments may be short-lived, with frequent elections. |

| Separation of powers may better protect rights of minority groups when an independent judiciary has the power of judicial review. | One individual must play the roles of both head of state and head of government. | Minority parties are frequently represented in parliamentary legislatures. | Minority groups have relatively fewer protections. |

| Party discipline tends to be weak. Strong presidents or populist leaders can emerge, presenting challenges to democracy. | Political parties and party discipline tend to be strong. | ||

Governmental Stability versus Policy Stability

Any discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of presidentialism and parliamentarianism begins with the hypothesis, first posited by Yale University professor Juan Linz , that parliamentary regimes are more stable than presidential regimes and that “the only presidential democracy with a long history of constitutional continuity is the United States.” 38 To Americans, the claim that parliamentary regimes are more stable may appear strange. As already noted, while parliamentary regimes have regular elections, they are not necessarily fixed-term elections. This means an election can happen at any time, opening up the possibility for multiple elections within a relatively short period of time. From 2018 to 2021, there were four separate elections in Israel. 39 In April 2020, Benjamin Netanyahu again was given the opportunity to form a new coalition government. 40 Ultimately, however, he was unable to do so and was ousted as prime minister. 41

To Americans, this may seem like the very definition of instability. Within this context, stability refers to the stability of the political system itself and not the stability of any particular government within that system. Parliamentary regimes may experience multiple elections in a short space of time, but that does not mean the system itself is unstable. It could simply reflect current electoral politics. In that respect, the current demographics of a particular country could work against a majority emerging and encourage coalition governments. Deep divisions within the Israeli electorate have made the formation and maintenance of a coalition government difficult. Nevertheless, the political system remains stable and in place, even if the ramifications of Israel’s crisis in determining its leadership do raise some concerns for aspects of the system. Any instability provides the opportunity for political change.

Instability can also take the form of policy change. Policy swings are more likely in parliamentary regimes. Because there are no set elections, elections could take place at any time. While public opinion does tend to move rather slowly, it changes over time and when triggered by events that cause the public to rethink key issues. Within a parliamentary regime, changing demographics or changing attitudes among the public could bring in a new government that has a very different majority than the old government. That new government could bring sweeping policy changes. Whether an individual sees the changes as a sign of political instability or a sign that the government reflects the will of the people may depend upon whether that individual agrees with the new policies. What one person might view as instability, someone else might see as needed policy change.

Coalition Governments

Generally, coalition governments are shorter-lived than majority governments. 42 The sheer duration of a government provides no indication as to its efficiency or its effectiveness in enacting public policy. The stability of a system can also be interpreted as policy change because the electorate may interpret the system as responsive and adaptable. Georgetown University visiting researcher Josep Colomer found that governments with more parties experienced greater stability with respect to policy change. 43

Israeli Opposition Parties Strike Deal to Form New Government

In this clip, DW News reports on the deal opposition parties struck to form a coalition government, resulting in the ouster of Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Forming a new government within the existing parliamentary structure does not require a fundamental change to that structure or its institutions. Consider what happens when a new US president is elected. That president forms a new administration. Similarly, after congressional elections, there may be new leadership in either or both of the houses if there have been significant partisan shifts, with one party losing majority status and the other party gaining it. The 2020 presidential election illustrates the point well. Joe Biden won the presidency and chose a cabinet. Similarly, Democrats gained a slim majority in the Senate and put in place a new majority leader, Senator Charles (Chuck) Schumer . The government was new, but the structure of the branches of government and its institutions did not change.

Coalition governments can be considered a disadvantage of parliamentary regimes, but they can also be a potential advantage. One argument in favor of a parliamentary regime with proportional representation is that more parties are represented. While presidential regimes do not inherently result in a two-party system, there is no doubt that the presidential regime in the United States works that way. Indeed, in the United States, no third-party candidate has ever won the presidency. Theodore Roosevelt came closest in 1912. While he managed to finish second and collect 88 Electoral College votes, he effectively split the Republican vote and helped to ensure the election of Woodrow Wilson , who received less than 45 percent of the popular vote. In a parliamentary regime, it is conceivable that Theodore Roosevelt would have been able to build a coalition with the Republican Party and form a government. So, not only is one more likely to have viable third parties in a parliamentary regime, but those third parties could hold significant power within a government.

One of the primary disadvantages of presidentialism is the possibility of gridlock. Political gridlock is when governments are unable to pass major legislation and stalemates between competing parties take place. Certainly, gridlock can occur within parliamentary regimes, but because presidential regimes have separate institutions, they often result in divided government and are biased against coalition building. Generally speaking, neither of those conditions is typical of a parliamentary regime. These conditions in presidential regimes appear to make them more conducive to gridlock.

Over the years, there has been considerable debate over whether divided government causes gridlock. Yale Emeritus professor David Mayhew argues that gridlock is not inevitable in divided government and that important legislative productivity takes place within both divided and unified governments. 44 That is not to suggest, however, that gridlock does not take place. Brookings Institution fellow Sarah Binder notes that the 2011–2012 Congress ranked “as the most gridlocked during the postwar era.” 45 When gridlock does happen, it tends to be highly visible, with each side publicly posturing and blaming the other side for the impasse, and gridlock eventually ends. That gridlock ends suggests a self-correcting aspect; the two political parties do not diverge from each other all that much or for all that long. 46 At the same time, presidential regimes carry a risk of polarization . While political polarization is not unique to presidential regimes, they are prone to its development.

The last 30 years in particular have seen an increase in political polarization. 47 The extent to which it exists both within political parties and within the electorate has been the subject of heated debate. 48 Political polarization is a disadvantage of presidential regimes that presents a cause for concern for the enactment of public policy. But does polarization cause a systemic breakdown in the legislative process? The short answer is that perhaps it can. Dodd and Schraufnagel have demonstrated a curvilinear relationship between polarization and legislative productivity. 49 Higher levels of polarization tend to be more likely to interfere with the policy-making process. But interestingly enough, low levels of polarization also result in low levels of productivity. It is when polarization is somewhere in the middle that legislative progress is most likely to occur. Indeed, Dodd and Schraufnagel note that attention should be given to the “virtues of divided government.” So, while presidential regimes work against coalition building, Manning J. Dauer Eminent Scholar in Political Science at the University of Florida Lawrence C. Dodd and Northern Illinois University professor Scot Schraufnagel conclude that divided government may provide both parties “some incentive to embrace sincere negotiation, timely compromise, and reasonable, responsive policy productivity by government, since each is responsible for one branch of government and could be held accountable by the public for obstructionist behavior by its branch.”

Show Me the Data

Viable third parties.

In any democracy, third parties or minority parties play important roles. Presidential regimes tend to encourage the formation of a two-party system, resulting in a weaker role for third parties than in most parliamentary regimes that have proportional representation. The reasons presidential regimes are more prone to result in a two-party system are twofold. The first is due to voting procedures. While there is considerable variation in how elections are held across countries, a common approach is plurality voting (also known as “first-past-the-post”). With plurality voting and single-member districts (one person being elected per geographic area), a two-party system is likely to emerge (this is known as Duverger’s law and was covered in Chapter 9: Legislatures ). The presidency is “the most visible single-member district.” 50 While Duverger’s law is not determinative because it does not guarantee a two-party system, it encourages its development. In addition to voting procedures, presidents have to appeal to voters across groups and form a coalition. Political parties are simply coalitions of varied groups. In order to appeal to as many voters as possible, political parties are more likely to broaden their scope of appeal rather than to define themselves more narrowly.

Third parties are much more viable in a parliamentary regime—that is, they have actual representation and voice within the national government. The 2018 elections in Italy resulted in over a dozen parties being represented in its parliament. Generally, this is a positive because voters are much more likely to vote for their first choice. Within a two-party system, however, voters may vote for their second choice because they do not wish to waste their vote. In a parliamentary regime with proportional representation, the threshold for representation within the parliament can be quite low at less than 5 percent. Once elected, the minority party could potentially find itself holding some power. In a parliamentary regime, a minority party may find itself with a disproportionate amount of power as it aligns itself with one of the larger parties. While it is possible to exaggerate the power the minority party holds in the partnership, it cannot be dismissed out of hand.

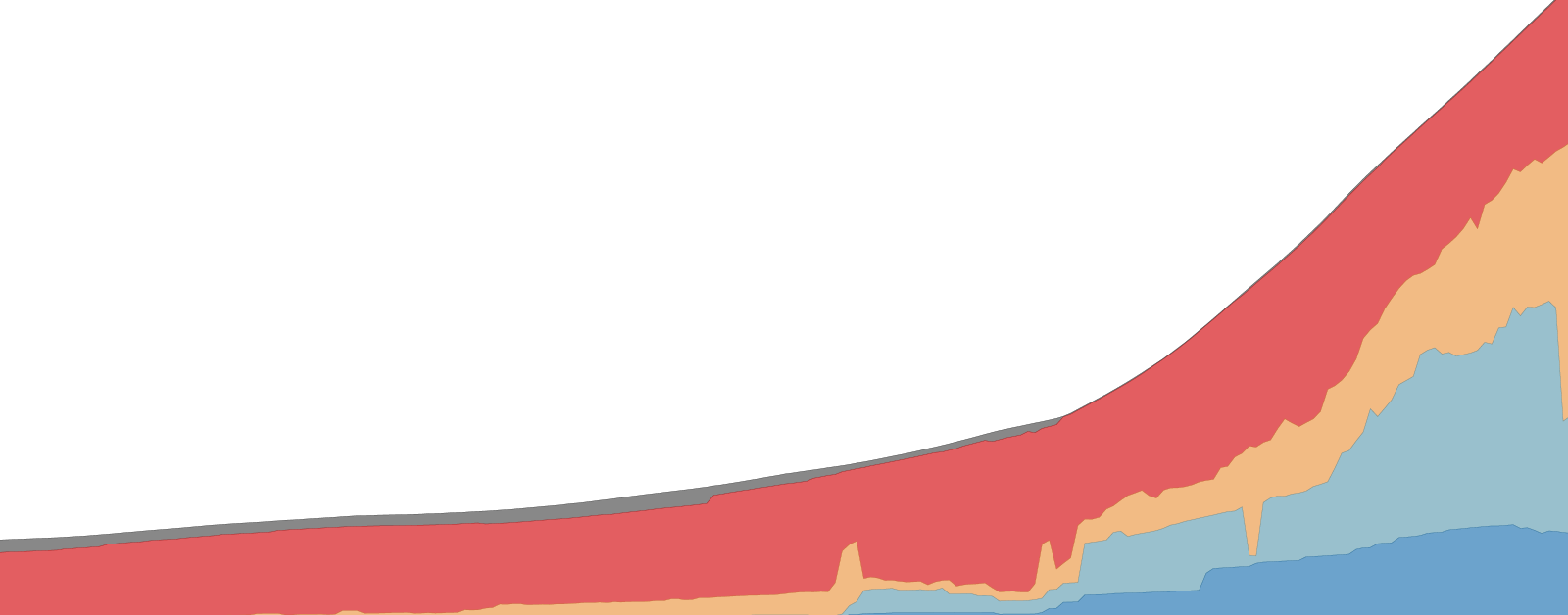

In a presidential regime, however, large numbers of voters face the unenviable task of voting for a candidate who is less than their first choice, and voters often frame that choice as voting for the “lesser of two evils.” In the 2016 US presidential election, 46 percent of Republicans indicated that neither of the major-party candidates would make a good president. For Democrat respondents, that percentage, while lower, was also substantial at 33 percent. 51 In recent presidential elections, the percent of voters indicating satisfaction with the candidates has never been higher than 72 percent and has been as low as 33 percent. See Figure 10.8 .

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Mark Carl Rom, Masaki Hidaka, Rachel Bzostek Walker

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Political Science

- Publication date: May 18, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-political-science/pages/10-4-advantages-disadvantages-and-challenges-of-presidential-and-parliamentary-regimes

© Jan 3, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions