An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Policy capacities and effective policy design: a review

Ishani mukherjee.

1 School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University, 90 Stamford Road, Level 4, Singapore, 178903 Singapore

M. Kerem Coban

2 GLODEM, Koc University, Rumelifeneri Yolu, 34450 Istanbul, Turkey

Azad Singh Bali

3 The School of Politics & International Relations; The Crawford School of Public Policy, The Australian National University, University Avenue, Acton, ACT 2600 Australia

Associated Data

Upon request.

Not applicable.

Effectiveness has been understood at three levels of analysis in the scholarly study of policy design. The first is at the systemic level indicating what entails effective formulation environments or spaces making them conducive to successful design. The second reflects more program level concerns, surrounding how policy tool portfolios or mixes can be effectively constructed to address complex policy objectives. The third is a more specific instrument level, focusing on what accounts for and constitutes the effectiveness of particular types of policy tools. Undergirding these three levels of analysis are comparative research concerns that concentrate on the capacities of government and political actors to devise and implement effective designs. This paper presents a systematic review of a largely scattered yet quickly burgeoning body of knowledge in the policy sciences, which broadly asks what capacities engender effectiveness at the multiple levels of policy design? The findings bring to light lessons about design effectiveness at the level of formulation spaces, policy mixes and policy programs. Further, this review points to a future research agenda for design studies that is sensitive to the relative orders of policy capacity, temporality and complementarities between the various dimensions of policy capacity.

Introduction: capacity considerations for effective policy design

The heart of policy design resides in the act of devising policy alternatives that meet stated government goals. While it is understood that not all policies can be carefully crafted, the policy sciences have been motivated by questions about why some policy alternatives are often developed well, while others are less so. Why do some policy choices, once formulated, effectively go forth through subsequent policymaking processes while others do not? How do some policies arise from meticulously crafted modes of formulation while others are shaped by partisan processes such as electoral or legislative bargaining (Howlett, 2011 ). Understanding factors that enable how deliberate designing of policy occurs and how superior designs can be achieved in complex issue-areas is central to the research agenda of the modern policy sciences (Howlett, 2014a , 2014b ; Howlett et al., 2017 ). The critical need to acknowledge, engage with and fully understand the capabilities underlying this exercise of good design, is also constantly escalating, especially in the face of widespread public crises.

Over the last few decades, a growing curiosity about the feasibility of formulation processes and the context within which policy choices unfold, has allowed policy scholars to gain a comparative perspective on policy design realities. Policy design is now generally defined as the purposive action of linking policy instruments with distinctly stated policy goals (Bobrow, 2006 ; Linder & Peters, 1984 ; Majone, 1975 ; May, 2003 ), stemming from the systematic endeavor to analyze how targets react or change their behaviors in response to instruments of governance. Effective design subsequently involves applying the knowledge gained about instrument-target relationships, to the creation of policies that can then predictably lead to desired policy outcomes (Bobrow & Dryzek, 1987 ; Gilabert & Lawford-Smith, 2012 ; Peters, 2018 ; Sidney, 2007 ; Weaver, 2009a , 2009b ). These activities are prefaced on the assumption that feasible polices can be realistically generated through effective design processes only when, firstly, contradictions internal to the substantive content of policy are resolved or minimized, and secondly, when the necessary capacities and capabilities to enact design procedures are in place (Bali et al., 2019 ; Mukherjee & Bali, 2019 ).

The recent scholarship in the policy sciences recognizes the first of these two emphases. For instance, studies anchored in the new design orientation explicitly focus on policy tools, how they are sequenced and assembled in mixes, how these mixes are calibrated, and their relative efficacies in meeting policy goals (del Río & Howlett, 2013 ; Howlett & Lejano, 2013 ). However, these studies have to a lesser degree raised issues about the capacity that is essential for effective policy design. In other words, experience from a variety of sectors and jurisdictions have alluded to what ‘effectiveness’ or ‘best practices’ imply for the activity of policy design, but lesser so about what capacities enable effectiveness.

Discussion of this latter topic is a largely scattered body of knowledge in the theoretical and empirical contribution of policy studies scholarship. For instance, the contemporary frameworks and theories of the policy process do not explicitly operationalize capacity as an independent variable in explaining policy outcomes (see for example Howlett et al., 2020a , 2020b for a recent review of the theories of the policy process). Here, we do not claim a ceteris paribus condition in which policy capacity is the only explanatory factor determining policy design effectiveness. While recognizing that many different determinants of policy design effectiveness exist, the article surveys the extant literature to specifically highlight the state of the knowledge on policy capacity requisites of policy design effectiveness. In doing so, the article brings to light the capacity ‘gap’ that exists in the policy design literature and draws lessons on not only what ‘effectiveness’ means at multiple levels of design but what is known to date about the capacities necessary for its enabling. The central question thus motivating this review asks what types of capacity are needed for effective policy design ? And to this aim, the article presents findings of a critical review synthesizing the existing scholarship on policy capacity and design in the policy sciences.

The article follows with an examination of the conceptual correspondence between the literatures on policy design effectiveness and policy capacity. The methodology informing this review is outlined next. In the fifth section that forms the core of our review, we consolidate the findings of our research on effective policy design spaces and instrument mixes and critically analyze these in the context of four emerging yet under-theorized themes from the scholarship on policy capacity, namely (1) the potential hierarchies in types of policy capacity, (2) the temporal dynamics within policy capacity, (3) task and agency-specific capabilities, and (4) complementarities among different types of capacities. We conclude by discussing avenues to advance a research agenda on effective design spaces and policy instrument mixes, which rigorously engages with these four themes of policy capacity.

Through this process, the paper makes two novel contributions focusing on the intersection of the policy design and policy capacity literatures. Firstly, it synthesizes the growing body of research in the policy sciences on effective policy design in terms of how particularly it discusses the necessary policy capacities that enable it. And secondly, by anchoring the review in the policy design orientation, the paper is able to identify four themes arising from the scholarly work on policy capacity that have yet to receive requisite theoretical and empirical scrutiny in the policy sciences. In doing so, we respond to repeated calls in the literature on the need to advance the scholarship and develop meaningful research questions on policy design effectiveness and the capacities that it necessitates. (Howlett & Lejano, 2013 ; Howlett et al., 2015a , 2015b ).

Understanding policy effectiveness

Policy effectiveness can be understood at three nested levels (Peters et al., 2018 ). The first relates to creating a conducive design space or an environment for policy formulation, which allows for effective policy design to occur (Howlett & Mukherjee, 2018a , 9). The second refers to developing effective policy mixes that are capable of addressing problems, and the third involves effectively designing and deploying individual policy instruments .

Effectiveness in design spaces

The essential idea is that the nature of the overall policy design space can significantly influence how effectively intended design activities occur and thus upon the likely resulting effectiveness of policy designs that emerge from them. These spaces reflect existing policy styles within a sector, are shaped by political conditions, reflect policy legacies (Howlett & Tosun, 2021 ), and therefore constrain (or enable) options available for designers. Developing policymaking spaces that are amenable to design activities involves a constant and concurrent stock-taking exercise of potential public capacities that might be pertinent in any problem-solving situation (Anderson, 1975 ). However, having an intention to be formal and analytical in designing and evaluating policy alternatives is not enough in itself to promote a design-centered process, since this also depends on the government’s ability to undertake such an analysis and to alter the status quo (Howlett & Mukherjee, 2018b ). Capacity challenges plaguing a design situation can lead to the generation of alternatives which are tenuously ‘patched’ together rather than deliberately packaged to uphold coherence and consistency (Howlett & Rayner, 2013 ).

Effectiveness in instrument mixes

While considerations for the design environment’s bearing on effective formulation have occupied the research agenda of policy tool studies in recent years, the new design orientation has contributed to a discourse on how to effectively incorporate policy mixes of policy goals and means (Briassoulis, 2005 ; Doremus, 2003 ; Gunningham et al., 1998 ; Hood, 2007 ; Howlett, 2011 ; Jordan et al., 2011 , 2012 ; Peters et al., 2005 , 2018 ; Yi & Feiock, 2012 ).

Selecting and deploying multiple instruments in the context of dedicated policy mixes ‘are all about constrained efforts to match goals and expectations both within and across categories of policy elements’ (Howlett, 2009a , 74). Achieving effectiveness with respect to deploying such mixes or policy portfolios relies on ensuring that mechanisms, calibrations, objectives and settings display ‘coherence’, ‘consistency’ and ‘congruence’ with each other (Howlett & Rayner, 2007 ). Scholars steeped in the new design orientation who are concerned with effectiveness have cautioned about how some policy mixes that are not designed in a planned fashion, can be plagued by internal inconsistencies, whereas others can be more successful in creating an internally supportive combination (del Río, 2010 ; Grabosky, 1994 ; Gunningham et al., 1998 ; Howlett & Rayner, 2007 ). This depends on how well they are able to adapt and support changing policy circumstances, as Thelen ( 2004 ) noted how the organization of macro-institutions has usually not resulted through calculated planning but rather has emerged out of processes of incremental adjustments such as ‘layering’ or ‘drift’ (Sewerin et al., 2020 ).

Effectiveness at the instrument level

While most of the research in the contemporary policy sciences have focused on issues around design spaces and instrument mixes, these has been limited, if any, comparative research on the efficacy of individual instruments and how they are calibrated (Capano and Howlett, 2020 ). At the most granular level, this third level of effectiveness focusses on the efficacy of individual policy tools and how these individual instruments are calibrated. Within this, we also need to differentiate between substantive instruments such as taxes, licenses, and subsidies; and the more indirect procedural instruments (such as competition, network structure, and royal commissions) which include administrative processes for selecting and deploying substantive tools (Capano and Howlett, 2020 ; Howlett, 2000 ).

There are at least three factors that condition the effectiveness of individual instruments and how they are calibrated. First, the extent to which substantive policy tools is supported by their procedural counterparts. Second, the extent to which critical institutional pre-requisites that condition the performance of instruments are present in policy mixes. Third, the extent of how far particular components of instruments or their calibrations can be easily adjusted in the short run and long run. This refers to changes in the settings of instruments such as adjusting tax rates or contribution rates for a pension fund. In some cases, there are sufficient ‘degrees of freedom’ to make these changes, or for them to be auto adjusting such as cost of living stabilizers, but in many cases calibrating instruments are difficult thereby undermining the effectiveness of an instrument.

Policy capacity: a brief review

Policy capacity, defined as a set of skills, competencies, and resources across government agencies to design and pursue policy goals (Rotberg, 2014 ; Howlett, 2015 ; Tiernan & Wanna, 2006 ; Wu et al., 2010 , 2015 ), has been a central research theme in public policy in recent years (Howlett and Ramesh, 2015 ; Newman et al., 2017 ; Karo & Kattel, 2018 ; Daugbjerg et al., 2018 ; Bali & Ramesh, 2019 ). In a notable first contribution, Wu et al. ( 2015 ) offer a framework to conceptualize policy capacity at multiple levels of governance. They argue that capacity can be understood as skills and competencies existing across government agencies at three nested levels: the individual (e.g., policymakers, decision-makers), the organization (e.g., an agency or a program), and at the systemic level (e.g., the whole of government or the macro level institutional, structural contexts) (Table (Table1). 1 ).

Dimensions and levels of policy capacity.

Source : Adapted from Wu et al. ( 2015 ) and Howlett and Ramesh ( 2015 )

| Level | Analytical capacity | Operational capacity | Political capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Technical knowledge, data analytical skills, issue expertise | Policy entrepreneurship skills (e.g., creativity, agility, navigating uncertainty, negotiation, draw on intuition and knowledge) | Political acumen (e.g., knowledge of stakeholder position), skills to build and maintain stakeholder support, reputation |

| Organizational | Arrangements for data analytics (e.g., access to and analysis of large datasets), access to external expertise, skilled personnel | Inter- and intra-organizational coordination, collaboration mechanisms (e.g., policy forums), financial resources, mechanisms for organizational learning, human resource management | Reputation, legitimacy, political support, stakeholder support |

| System | Data collection and analysis mechanisms and tools (e.g., transparency), arrangements to overcome heuristics, biases through competitive advisory systems | Mechanisms for intra-state (vertical and horizontal) coordination and planning processes, collaboration with non-state actors, clear organizational mandates | Trust, legitimacy, accountability (e.g., citizen participation, multi-level governance arrangements) |

At the level of individuals occupied with policy formulation, those striving for effective design require technical know-how to conduct practical policy analysis and disseminate knowledge, while leadership and negotiation abilities are additionally relevant for those in managerial positions. Analysts also need political savvy and acumen for incorporating and accounting for various stakeholder interests and assessing political feasibility. At the level of government organizations , information mobilization capabilities to enable timely and relevant policy analysis, administrative capital for ongoing coordination between policymaking agencies, and political backing all fundamentally build overall policy capacity. At the system level, effective policy design requires institutions for knowledge creation and utilization, alongside mechanisms to coordinate across different levels of government, and overall trust and political legitimacy (Mukherjee & Howlett, 2016 ).

Howlett and Ramesh ( 2015 ) extend Wu et al.’s ( 2015 ) work on capacity drawing on the metaphor of an ‘Achilles’ Heel.’ That is, how certain types of capacities can become critical to the sustaining policy efforts and outcomes in specific modes of governance, and how any weaknesses in these ‘critical’ capacities can undermine policy efforts (Menaheim and Stein 2013 ).

Technical knowledge, for example, is a critical capacity required for the sustainable functioning of policy systems based on market-based governance. Analytical skills at the level of individual analysts and policy workers are key, and the ‘policy analytical capacity’ (Rayner et al., 2013 ; Wellstead et al., 2011 ) of government needs to be especially high to deal with complex quantitative economic and financial issues involved in regulating and steering the sector and preventing crises (Bakır & Çoban, 2019 ; Rayner et al., 2013 ; Woo et al., 2016 ). Similarly, undertaking policy design within legal systems of governance relying heavily on high levels of managerial capacities that can deter against diminishing returns of compliance or mounting non-compliance with government directives (Coban, 2020a ; May, 2005 ). Capacities at the systemic level can be especially critical in this case as governments find it difficult to enact traditional command-and-control instruments in the absence of overall public trust.

The appeal of Wu et al.’s ( 2015 ) framework lies in its inherent simplicity. Each of the nine capabilities lend themselves to, in principle, being empirically operationalized and allows analysts to assess strengths and weaknesses of governments across different types of capabilities (e.g., Bajpai and Chong, 2019 ; Saguin et al., 2018 ). Yet such simplicity also generates concerns.

First, the contribution by Wu et al. ( 2015 ) does not lend itself to drawing causal inference or developing a theory of policy capacity. Moreover, as our review demonstrates below, the mechanisms that connect indicators with specific types of capacities are not explicitly mentioned. Secondly, the current literature seems to adopt a benevolent approach to incumbents relying on or mobilizing policy capacity. 1 That is, policy capacity could also facilitate the ‘dark side’ of policymaking (Howlett, 2020 ), by advancing policymakers’ self-interested, political and/or economic ‘rent-seeking’ objectives (see Chindarkar et al., 2017 ; Howlett and Mukherjee, 2016 ). Furthermore, it can be instrumental for developing ‘placebo policies’ as ‘agenda management safety valves’ (McConnell, 2020 , 965) or for ‘hidden agendas’ (McConnell, 2018 ) to further political goals rather than addressing the core of policy problems. These represent unchartered areas, especially if we consider the challenges generated by the rise of populism and autocratization around the world (Kelemen, 2017 ; Maerz, 2020 ; Norris & Inglehart, 2019 ).

This review relies on building and scrutinizing a database of peer-reviewed journal articles that are located at the intersection of policy capacity, policy design, and effectiveness. A keyword search based on these themes was conducted on Scopus, and Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science (WoS). Scopus and WoS are two major repositories of scientific knowledge published in various forms: conference proceedings, edited book chapters, peer-reviewed journal articles. The search protocol was conducted similarly on both databases to cross-check for any duplicate journal articles, and avoided selection bias that can result from extracting data from a single database. The search covered three collections of WoS citation indexes: Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI). We explicitly included ESCI and A&HCI along with SSCI given our concerns for inclusivity.

The data collection and sample selection process had four steps. The first involved searching for, ‘policy design’, ‘capacity’, ‘effectiveness’, as keywords for the topic of an article. In this focused search, we omitted a set of alternative keywords such as ‘capability’, which are mostly used in public management scholarship. More importantly, the focused search as conducted through these keywords allowed us to capture a range of terms, such as ‘governance capacity’ and ‘administrative capacity’, in which capacity has been used in the context of policy design and/or design effectiveness. As such, it should be noted that articles that incorporated such varieties of capacity, but did not directly discuss policy design were excluded from the final database. In this light, we are aware that the search focused on a designated subset in the existing policy design literature. However, this scope allowed us to fully capture the dispersed attempts made so far to deliberately link policy capacity and design effectiveness and address our express interest in showcasing the current state of the literature that is located at the intersection of policy capacity, policy design, and design effectiveness. Additionally, the search was designed to be as inclusive as possible given the time period, disciplines, and multiple databases that it incorporates.

While acknowledging the limitations of the search logic described herein, we maintain that additional keywords would result in extra layers that dilute the task of specifically exploring the policy capacity requisites for policy design effectiveness. We also note that detecting journal articles on WoS and Scopus required us to run the search several times with various combinations of these keywords. This is because research that is positioned at the intersection of policy capacity, policy design, and effectiveness is in its adolescence. We therefore combined the results of multiple searches while removing duplicate entries. Our search covered the period between 1900 and May 17, 2020, the date we ran the search on WoS and Scopus. This time period allowed for construction of an inclusive database. This search yielded a sample of 9382 sources. The second step involved filtering our initial search for journal articles that are published in English. 2 The result of this process reduced the sample to 7441 articles. In the third step, we further refined our search by filtering the articles according to various relevant (inter)disciplinary areas: ‘political science’, ‘public administration’, ‘economics’, ‘management’, ‘international relations’, ‘sociology’, ‘social sciences interdisciplinary.’ In so doing, we included articles that are not only published in political science and public administration but also in other main social science disciplines and those that were classified in the interdisciplinary social sciences category. This choice was mainly driven by inclusivity concerns and an expectation of capturing articles that may empirically or conceptually refer to policy design, policy capacity, and/or effectiveness. The result of the second stage to limit our search to relevant fields yielded 1431 journal articles.

Following the above-mentioned steps, we read titles, abstracts, and full texts to further refine the most relevant articles. Articles that had the main keywords in the topic, but were not directly related to our research questions were omitted based on a reading of their introductory sections and research questions. We omitted articles that used different forms of capacity without an explicit interest in operationalizing capacity for design effectiveness. We also omitted articles that attempted to measure or evaluate effectiveness of an instrument or program. In this regard, as our interest in this article is to make sense of what capacity for ‘effectiveness’ means at multiple levels of design, our exclusion criteria meant that we eliminated articles which presented only nominal links between policy design and policy capacity. Consequently, the final sample included 146 articles. As for coding, the sample included articles that discuss policy design as well as effectiveness. Therefore, coding had to sort according to levels of policy design and dimensions of policy capacity. This process involved two tracks. First, we coded articles to capture dimensions of policy capacity according to parameters suggested by Wu et al. ( 2018 , 6–14). Second, reading the articles served to code an article whether it did examined design space, discussing design effectiveness of a policy instrument, policy mixes reading the articles led us to code articles whether it was about design space, discussing design effectiveness of a policy instrument, policy mixes/programs, or combinations levels of policy design.

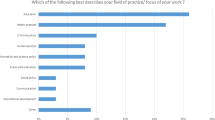

Table Table2 2 and Fig. 1 summarize the results of the coding process. Articles on design space, policy mixes and programs have the highest share among those referring to level of policy design. A main observation at the outset is that there is a significant gap in the literature on studies discussing policy design and capacity at the level of individual instruments. The review included explicitly those scholarly contributions that engage with capacity considerations. Undoubtedly, the field of environmental policy (and for that matter social policy and financial policy) is replete with the discussion of singular instrument types such as taxes, social security schemes, emissions trading schemes, among others. But this review could not identify articles that expressly deal with the question of capacity and what is needed on the part of policy designers to formulate these instruments, which is a significant void that needs to be filled in future studies. Even the studies that distill the state of knowledge on effective program design, rarely discuss individual constituent policy tools.

Levels of policy design and dimensions of policy capacity

| Number of articles | |

|---|---|

| Design space | 67 |

| Policy mixes/programs | 41 |

| Design space and policy mixes/programs | 26 |

| Policy instruments and design space | 2 |

| Design space and global public policies | 2 |

| Policy mixes/programs and policy instruments | 3 |

| Policy mixes/programs and global public policies | 4 |

| Policy instruments and global public policies | 1 |

| Individual/organizational/system | |

| Individual | 24 |

| Organizational | 32 |

| System | 32 |

| Individual and organizational | 21 |

| Individual and system | 10 |

| Organizational and system | 15 |

| Individual and organizational and system | 12 |

| Analytical/operational/political | |

| Analytical | 26 |

| Operational | 4 |

| Political | 32 |

| Analytical and operational | 17 |

| Analytical and political | 27 |

| Political and operational | 2 |

| Analytical/operational/political | 38 |

| Total | 146 |

Dimensions of policy capacity and levels of policy design

On the dimensions of policy capacity, articles address analytical and political capacity more so than operational, while there is a more equal distribution of articles referring to individual, organizational, or systemic scales. In addition, our observations point to a limited number of studies that look at both organizational and individual policy capacity, as well as both political and operational policy capacities. Finally, we note that only a few studies attempt to relate policy capacity with effective design space for global public policies, instruments, and mixes/programs (Bernstein & Cashore, 2012 ; Cashore et al., 2019 ; Dare, 2018 ; Dorsch & Flachsland, 2017 ; Jordan & Huitema, 2014 ; Stone & Ladi, 2015 ; Vince & Nursey-Bray, 2016 ).

Policy capacity requisites for effective policy design: emerging trends and existing gaps

In this section, we discuss the main findings on the link between policy design effectiveness and policy capacity as revealed through the review of the literature. While these findings are discussed at the level of effective policy design spaces and effective instrument mixes, we critically examine them through the perspective of four overarching emphases that that are developing within the scholarship on policy capacity and policy design (Bali & Ramesh, 2018 , 340–341; Howlett and Ramesh, 2015 ; Capano & Howlett, 2020 ; Howlett et al., 2015a , 2015b ). These are, namely:

- Hierarchies or ‘orders’ among specific types of capacities, which indicate what kinds of capabilities are more pre-requisite and foundational to others that are more ‘second-tier’ and aspirational.

- Temporality of policy capacity endowments, or the time needed for policy capacity investments to achieve actual effectiveness outcomes.

- The distinction between task-specific and agency-specific policy capacities and how to reconcile between them; and

- The synergies and complementarities between different policy capacities.

Capacities for effective policy design spaces

Developing effective design spaces is fundamentally about ensuring that policy tools are anticipated to fit or cohere with broad governance arrangements, while delivering a means to address certain policy goals. It is argued, for example, that several variables are critical for effectiveness within collaborative modes of governance, including reconciling with ‘prior history of conflict or cooperation, the incentives for stakeholders to participate, power and resource imbalances, leadership and institutional design’ (Ansell & Gash, 2008 , 543). Similarly, the absence of clear property rights and mechanisms to enforce contracts stymie the effectiveness of hybrid governance arrangements to design suitable public–private partnerships (PPPs) in service delivery (Virani, 2019 ).

An enabling design space that is able to support the design of its constituent policy instruments signifies an environment that is marked by high analytical, operational and political capacity (Capano, 2018 ; Chindarkar et al., 2017 ). Determining exactly what capacities are required in order to develop the political and administrative spaces needed to carry out complex policy design processes is currently a subject of much interest in the field (Considine, 2012 ). In order to address these issues, it is recognized that policy designers need to be cognizant about the internal mechanisms of their polity and constituent policy sectors which can boost or undermine their ability to think systematically about policy and develop effective policies (Braathen, 2007 ; Braathen & Croci, 2005 ; Grant, 2010 ; Skodvin et al., 2010 ).

In this vein, organizations and individual policymakers need political support from the policy design spaces or environments that they occupy. For this, they derive legitimacy and authority from system-level political capacity, which subsequently creates a favorable milieu for the application of individual and organizational political capacities during the design process (Woo et al., 2015 ; Xiarchogiannopoulou, 2015 ). Political support to policymakers and interactions between policymakers and politicians have been argued as being non-substitutable when it comes to overcoming ambiguous goals and promoting managerial effectiveness, by supplying organizations with a clear understanding of their overall mandate (Meckling & Nahm, 2018 ; Stazyk & Goerdel, 2011 ).

At more individual and organizational levels, political capacity is essential for maneuvering effectively within the constraints of the design space (Hartley et al., 2015 ) and is embodied in the levels of trust, especially political trust and legitimacy within the public sector. Individual and organizational political capacity is also necessary to garner strategic stakeholder support that is vital both before and during the design process, as well as in subsequent stages of policy implementation (Bali & Ramesh, 2019 ). For example, in the case of macro-prudential policy, a suitable financial policy mix is possible in an enabling design space that is characterized by capable, analytically skilled individual central bankers that have coalition-building skills, a government committed to evidence-informed policy, and presence of inter-organizational collaboration mechanisms at system level (Bakır & Çoban, 2019 ).

This example also highlights the importance of ‘legitimation capacity’ in effective design environments (Woo et al., 2015 ; see also Pal & Clark, 2015 ). Policymakers and organizations that are highly regarded by key societal actors and receive sustained political support are able design effective policies with more accountability (Busuioc & Lodge, 2016 ; Rimkuté, 2018 ). For example, as is visible in the case of health and safety regulation in the UK, the regulatory agency’s outreach and engagement with policy targets increases its political acumen by helping to overcoming citizens’ biases, and furthering its legitimacy by shoring up societal support for future policy design (Dunlop, 2015 ). This case also underscores the dilemma that may exist between expertise-led, technocratic, and less accountable design on the one hand; and participatory, more accountable design processes on the other, and the relative effectiveness of either situation (Montpetit, 2008 ). Yet, overall high levels of trust and political support at the system level are shown in most cases to allow the design process to be endowed with necessary information and access to critical resources at the outset (Chindarkar et al., 2017 ; Hartley et al., 2015 ).

An example of this latter context is the rise of ‘big data’ analytics that has also necessitated a parallel emphasis on big data readiness at all three levels of capacity (Clarke & Craft, 2017 ; Giest, 2017 ; Giest & Mukherjee, 2018 ; Golan et al., 2017 ). For example, policy responses to the Covid-19 pandemics in countries like Singapore have included combining mobile-phone-tower data and machine learning to develop social graphs that track propinquity to improve contact-tracing (The Economist, 2020 ; see also Woo, 2020 on the Singapore case). Big data has also been used for network analysis in policy formulation (Giest, 2017 ). But, the availability of data, network analysis and modeling necessitate complex skills such as making use of software, models to produce insights that inform policy design. Moreover, related studies have repeatedly underlined that policymakers should take into consideration behavioral dimensions of policies, which becomes more likely when organizational infrastructure allows for the participatory collection as well as engagement with behavioral data and analysis (Leong & Howlett, 2020 ; Mukherjee & Mukherjee, 2018 ).

Hierarchies within types of capacities

Studies in this review of effective design spaces implicitly operationalize specific types of capacities as a spectrum of independent variables and argue that they shape policy outcomes. While this advances our understanding of how capacity is connected with notions of effectiveness, the causal mechanisms that undergird such links have not always been made clear. This can be explained to some extent by the tendency in the literature to operationalize capacity in a straightforward, often univariate manner, while ignoring possible orders or hierarchies among specific types of capacities. In other words, policy capacity can be multi-dimensional with notable interaction between foundational, first-order and more aspirational or ‘second-order’ capacities. Lodhi ( 2018 ) and Hartley and Zhang ( 2018 ), for instance, suggest a comprehensive measurement of policy capacity. Such efforts can then allow for multiple orders of capacities to be observed while and better locate the interactions between them. A focus on how policy capacities at one level can enable, prevail over those, or constrain capacities at the other two levels are neglected factors when theorizing the link between policy capacity and policy design effectiveness.

For example, if system-level policy capacity is more crucial as it constitutes the environment in which an organization or an individual policymaker operates, can it be postulated that without the acquisition of system-level capacities, even high individual or organizational policy capacity might not be sufficient for effective policy design? More research along this vein is warranted to advance our understanding about any hierarchy or orders of policy capacity and the role they play in developing effective design spaces.

Along the same lines, most studies in this review focus on operationalizing a specific type of capacity rather than considering how combinations or interactions between different types of capacities shape policy outcomes. For instance, in a context wherein system-level policy capacities are high but individual policy capacities cannot uphold organizational capacities, one may observe sub-optimal design or even non-design. Such a case could indicate that while we may consider the presence of system-level policy capacity to be detrimental for on-the-ground mobilization of organizational and/or individual policy capacity, the reverse dynamic may also be important for effective policy design.

Further, while most studies in the review have considered political capacity to play a more critical role than operational and analytical capacities, they have stopped short of developing hypothesis or propositions to attribute plausible reasons for its significance. This, in turn, stagnates any advancement in how specific types of capacities can explain and beget design effectiveness.

Temporal dynamics of capacity

There is a gap in our understanding on the temporal dynamics and change within the policy design literature (see, e.g., Capano & Howlett, 2020 ; Bali & Ramesh, 2018 ), and this lacuna is also evident in this review of necessary capacities for effect design. Temporality in the context of capacities for effective design explores changes in specific types of capacity endowments over time, to their sustained or ultimate impacts on policy outcomes. It also includes a consideration of how investments in capacity building have a latent gestation period before which they begin to affect outcomes. None of the studies in this review explicitly dwelled on the temporal dimensions of capacities, echoing the popular refrain on the largely atheoretic discussion on policy tools and capacity (Howlett & Ramesh, 2015 ; Howlett et al., 2015a , 2015b ).

Temporality in the context of effective policy design can be conceptualized in two ways. The first is to consider the impact and scope of changes in capacity on effectiveness at different stages of design process. For example, what are the causal mechanisms by which changes in capacities contribute to changes in policy outcomes? That is, do interventions at time t 0 affect outcomes by time t n . Is the lag between t n –t 0 standardized across different types of capacities? Such lines of enquiry can inform about how individual, organizational, or system-level policy capacities change over time and result in fluctuations in the effectiveness of policy designs. For instance, the National Sample Survey Organizations of India in the 1950s was recognized globally as a center for excellence and pioneering statistical sampling techniques and methodologies, but in recent years has become mired in controversy on the quality of its statistical estimates (Banerjee et al., 2017 ).

Secondly, a discussion on temporality also implicates concerns about robustness and resilience of policy design. Robustness over time can enable policymakers, organizations or a system to endure shocks, policy surprises, and turbulence, while allowing them flexibility (Ansell et al., 2016 ; Capano & Woo, 2017 ; Howlett et al., 2018 ; Mergel et al., 2021 ). Endurance could be achieved with adaptability to structural, institutional and actor-level changes and/or evolution of existing policy capacities over time (e.g., Alaerts, 2020 ; Capano & Pavan, 2019 ; Van Der Steen et al., 2018 ). And subsequent adaptability could arise on improvements in complementarities among different types and levels of critical capacity requisites. These are particularly relevant to anticipatory policy design (Bali et al., 2019 ; Huitema et al., 2018 ; Kimbell & Vesnić-Alujević, 2020 ), especially in cases of high contextual uncertainty, as is exemplified by numerous examples of climate change impacts on agriculture or water policy domains (Nair & Howlett, 2017 ). While such a conceptualization seems plausible, the existing literature lacks a systematic understanding of what types of capacities enable design spaces to endure substantial changes in the structural and institutional contexts of policies as, for example, the Covid-19 crisis has already demonstrated (Walter, 2020 ; Weible, 2020 ).

These considerations also call for a discussion on the temporal nature of acquiring or engendering policy capacities and which of these are necessary earlier on in the design process. For example, effective policy design could be the outcome of initial improvements in individual and organizational capacities, which may later require the build-up and/or mobilization of system-level capacities. These are propositions that need to be examined to advance our understanding of whether or not individuals, organizations, or systems need to build particular capacities first for effective policy design to subsequently unfold.

Capacities for effective instrument mixes and programs

The growing intractability of contemporary challenges that governments face in areas such as health and urban planning among others has necessitated the use of multiple policy tools to be carefully and deliberately assembled in policy mixes or portfolios (Howlett & Lejano, 2013 ). This has made the task of effective policy design more challenging, as designers have to match not only policy goals and aims, but also instrument mixes and governance modes (Peters & Pierre, 2015 ; Tosun & Lang, 2017 ; Wen, 2017 ). In turn, this effort towards striving for compatibility requires a spectrum of analytical capacities that enables policymakers, organizations and political systems to employ skills pertaining to the accurate articulation of operational objectives, which in turn require an accurate interpretation of context relevant information and data. These analytical skills become fundamental to the success of sector-wide programs that may otherwise suffer from a mismatch between stated objectives and the policy tool collections that are constructed as a response. In other words, and as reported in many program-level studies, the more (or less) policymakers resemble analytically capable policy designers, the more (or less) likely they are to construct an effective mix of policies through a program. For instance , Siwale and Okoye ( 2017 ) argue that microfinance program initiatives in Zambia were ineffective largely due to limitations in policymakers’ analytical capabilities.

Besides individual and organizational policy capacities, reforms buttressed on the tenets of New Public Management (NPM) marked administrative changes in the late 1990s, which embodied a large, albeit skewed, emphasis on the kinds of capabilities that are necessary for policy success. With this transformation, policy capacity to design and steer policies became truncated, as states increasingly contracted out the delivery of public services to the private sector and civil society. This has been argued to have resulted in loss of policy capacity within government, in the reform era, in the form of declining skilled human resources which affect both organizational and system-level analytical and operational capacity within the state apparatus (Bakvis, 2002 ; Baskoy et al., 2011 ; Craft & Daku, 2017 ; Donahue et al., 2000 ; Howlett, 2000 , 2009b ; Lodge, 2013 ). Put differently, with the ‘hollowing out’ of the state, the changing role of the state as the primary actor in the design process has evolved into that of a policy navigator that steers the policy process and coordinates the interactions between non-state actors and those between the state and non-state actors (Lindquist, 1992 ). Policy capacity in this sense has been often supplemented by external expertise, knowledge, know-how supplied by variegated epistemic communities, think tanks, business, international organizations, scientists, non-governmental organizations, or civil society groups among others can supply (Haas, 1992 ; Stone, 2003 ).

With the externalization of knowledge and related capacities, many studies have alluded to greater participation being fundamental for effective program design that needs to be shaped in a way that is more notably open to stakeholder input and learning from that input (Borrás, 2011 ; Hoppe, 2011 , 2018 ; Jordan & Huitema, 2014 ; Vince & Nursey-Bray, 2016 ). The water quality program in the European Union (EU) is a case in point. Brown ( 2000 ) examines the EU’s operational and analytical capacity to design effective directives when it faces scientific uncertainty in the given policy area, and most importantly fluid number and quality of staff (see also Jensen, 2018 on policy capacity requisites for effective water policy in developing countries).

This case and others demonstrate that input from international organizations and local stakeholders generally tend to increase the supranational organization’s operational and analytical capacity. Echoing the call for greater participation, Mukherjee and Mukherjee ( 2018 ) determine citizen participation to be fundamental in co-production in rural sanitation programs in India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. Lang ( 2014 ) studies analytical capacity in PPPs in which the private sector brings its own expertise to complement goals set out by policymakers. Similarly, Bengston et al. ( 2004 ) sheds light on participation of citizens and other stakeholders in urban policy in making formulation more effective. These studies all suggest that when policymakers have a tendency to underestimate or even ignore stakeholder participation and input, the effectiveness of policy design and implemented policies can decline considerably. While a few recent studies have now begun to look at particular types of capacities that different stakeholders, especially interest groups, can contribute (see Coban, 2020b ; Daugbjerg et al., 2018 ) they still fall short of addressing the benefits or challenges they can bring specifically to policy design effectiveness, thus calling for further research in this area.

Additionally, when non-state actors participate actively in the design process, this understandably has implications for the governance capacities that are available for effective policy formulation. Studies highlighting polycentric policy design processes have emphasized policy capabilities for enabling the coordination and collaboration of multiple actors. Political capacity to manage collaboration and coordination has also been called ‘collaborative capacity’ in some public management literature, within organizations or specific programs (Ansell & Gash, 2008 ; Braun, 2008a , 2008b ; Schout & Andrew, 2008 ; Weber et al., 2007 ).

In a multi-level design situation, such as policy programs, horizontal and vertical coordination of parties similarly demand high political capacity (Peters, 2015 ). Golan et al. ( 2017 ), for example, show that lack of effective coordination between the central authorities and the local authorities in the design of rural cash transfer programs that omit a considerable share of the target population, lead to reduced effectiveness of the program’s objectives. Similarly, Wen’s ( 2017 ) study on social policy in China indicates that when the central state does not coordinate policy design with the local authorities that lack policy capacity, policy design effectiveness faces substantial challenges at all levels.

Collaboration and coordination challenges have been significant in developing countries as well as in advanced economies. Williams and McNutt ( 2013 ), focusing on policy programs for climate change adaptation in the Canadian finance sector, assert network management capacities for aligning the targets of local and federal and provincial agencies to be built into the design of the programs and well before their implementation. Additionally, Skeete ( 2017 ) examines policy instrument mixes that regulate carbon emissions emanating from diesel use in the European Union (EU). The author finds that lack of coordination between member states and EU authorities, besides leading to inherent flexibilities of the regulatory framework, also leads to fuel taxes failing to achieve original climate policy goals. Similarly, Spendzharova ( 2016 ) maintains that disconnect between EU member states and EU authorities in the design of banking structure reforms after the global financial crisis leads to a mismatch in design processes in terms of prioritizing domestic reforms vis-à-vis EU level financial reforms.

Complementarities in policy capacities

Such studies on policy instrument mixes and programs highlight the primary role of analytical capacity in developing and deploying effective instrument mixes. However, it can be insufficient if not operating alongside suitable organizational and political capacities, which ultimately determine how successfully they are implemented (Bali et al., 2019 ; Mukherjee & Bali, 2019 ). In other words, analytical capabilities are enhanced or sharpened by operational and political capacity endowments at the level of organizations. This is not surprising as policy design is ultimately a political activity and requires individual policymakers to strategically operate within a broad community of policy stakeholders and organizations (Peters, 2015 ).

For example, Mukherjee and Giest ( 2019 ) show how individual policy entrepreneurs’ capacity to form and maintain coalitions has enabled effective use of individual, organizational and system-level capacities in digital transformation in the EU. Similarly, Ramesh and Bali ( 2019 ) demonstrate how operational capabilities in Singapore’s health system were amplified by sustained political capacity and trust in government. However, these studies and others in this review do not develop generalizable propositions that can be empirically examined on the complementarities and synergies among different types of capacities in different contexts. That is, the aggregate impact of a series of specific capacity endowments is larger than their individual impacts (Wu et al., 2015 ). Similarly, do critical deficits in capacities affect outcomes? (Howlett & Ramesh, 2015 ). These theoretical gaps are particularly visible given that developing policy designs that harness synergies and complementarities among tools is a central theme in the new design orientation (Howlett et al., 2015a , Howlett et al., 2015b ).

One way to address this missing link is to canvass the recent advances around policy success in the public management literature. For instance, design effectiveness is intrinsically related to policy success, as ‘successful policy often resides in policy design and the diligent work undertaken’ (McConnell, 2017 , 17). These themes have been interrogated further in a series of studies that aim to advance what is described as ‘positive public administration’ (Compton & ‘t Hart, 2019 ; Luetjens et al., 2019 ; Douglas et al., 2019 ), which define success across four broad dimensions: if it achieves its goals (i.e., programmatic success), produces largely supported socially appropriate outcomes (i.e., process success), contributes to problem-solving capacity and enhance legitimacy (i.e., political success), and is robust (i.e., endurance) (Ibid, 5).

Connecting groups of capacities with specific dimensions of success can allow analysts to develop proposals around complementarities in capacities to be then examined empirically. For example, policy success could be less likely when operational capacity at system level in the form of coordination mechanisms both within the state and between the state and non-state actors is not established and/or mobilized. Testable claims that emerge from this debate are that if these conditions are not met, enabling political and processual success may not emerge leading to incongruent policy goals and tools. Cumulatively, these outcomes may result in failures in programmatic and endurance terms, bringing about policy (instrument) fiascos (Bovens & ‘t Hart, 2016 ). This in turn provides a richer understanding of the types of capacities required for developing and deploying effective mixes.

Task and agency-specific capacities

There is a tendency in the literature and in contemporary debates to use ‘policy capacity’ as a catchall phrase (Wu et al., 2015 ). An avenue to overcome this simplification is to engage rigorously with the ‘capacity for what’ question (Bali & Ramesh, 2018 ). That is, to identify, ex ante, and theorize task-specific and agency-specific capacities needed for routine but complex tasks in contemporary service delivery such as contracting, managing PPPs, and administering pension funds; and accomplishing these effectively during periods of extreme uncertainties and volatility such as crises (Capano et al., 2020 ; Stirling, 2010 ).

The new design orientation has set up a tall order for effectiveness in program designs whereby designs must be coordinated, coherent, reduce contingent liabilities, and avoid Type 1&2 errors, among others (Bali & Ramesh, 2017 ; 2018 ; Howlett, 2018 ). For example, while network governance may be well suited to policy design for sensitive issues such as elderly care or parental supervision (Pestoff et al., 2012 ) in other situations, civil society may not be well enough organized or endowed in order to generate beneficial network modes of governance off-the-ground and without initial regulatory support (Tunzelmann, 2010 ). Networks, for example, ‘will fail when governments encounter capability problems at the organizational level such as a lack of societal leadership, poor associational structures and weak state steering capacities which make adoption of network governance modes problematic’ (Howlett & Ramesh, 2014 , 324).

However, in our review there is limited, if any, theoretical discussion on the types of capacities needed to achieve these outcomes. That is, the range of capacities required to accomplish tasks such as contracting, commissioning, and collaboration while all under the umbrella of network governance require a variety of distinct capabilities and skillsets (O’Flynn, 2019 ). Failing to recognize these variations and invest in task-specific capabilities has played a key role in failed social policy reforms in many developing economies (Maurya & Ramesh, 2019 ; Virani, 2019 ). Along the same lines, variations in the capacities of agencies within government to pursue such tasks must be recognized (Bardhan, 2016 ).

Conclusion: avenues to advance the research agenda on capacity and design

This paper addresses a scattered body of knowledge in the policy sciences and aims to advance our understanding of the relationship between policy capacity and effective policy design. To this end, this paper presents a review of the existing literature that studies effective policy design through the lens of policy capacity, and argues that such a perspective offers an important starting point for scrutinizing the role of complementarities among organizational, individual, and system-level analytical, operational, and political capacities, within the broader policy sciences.

Clarifying the relationship between design effectiveness and policy capacities is central to advancing the research agenda of the new design orientation in the policy sciences. The theoretical union of these two bodies of literature, at its core, is about reiterating the problem-solving approach in the policy sciences. That is, it inspires building on the research questions surrounding how specific policy interventions are devised to address specific types of problems, with notions of what is fundamentally needed to enable these designs. The most well-intentioned efforts at policy design can be constrained by the capabilities of governments, and those involved in the design process (Mukherjee & Bali, 2019 ). Forwarding such a research agenda can further refine the generalizable hypotheses to investigate and improve policy deliberations regarding effective policy formulation, which already inform the policy sciences (Howlett & Lejano, 2013 ; Howlett et al., 2015a , Howlett et al., 2015b ). To this end, this review has provided several starting points for infusing policy design research with policy capacity concerns.

Our central thesis is that the growing body of research on policy design effectiveness, which is synthesized in this paper, remains largely descriptive and tends to confound rather than clarify the relationship between policy capacity and effective policy design. Our review points to several outstanding questions that need to be highlighted: Do individual, organizational, or system-level policy capacity change over time? Does effectiveness of policy designs and success of policies vary over time with changes in policy capacity of various types ‘spilling over’ and at different levels? Thirdly, do orders of policy capacity exist? And can we distinguish between hierarchies or levels of policy capacity, which have serious implications for effective policy design and thereby policy success (or failure). Specifically, this strand of reasoning can help distil those capacities that are fundamental at the start of policy design (t 0) before successive ones are developed at subsequent stages of policy design (at t 1 and expectedly later at t n ). Is there a hierarchy among levels of policy capacity? If yes, then what is the nature of that hierarchy and are there causal inferences that can be drawn between more fundamental ‘enabling’ capacities and more aspirational ‘second-tier’ capacities? And, how does such a hierarchy impact effectiveness of policy design and determine policy success (or failure)? Finally, given the lack of focus on policy capacity requisites for effective individual policy instrument design, does, and if so, how policy capacity enable effective policy instruments?

Scholarly efforts to engage with these questions can be a generative exercise, signposting new areas for theoretical exploration and empirical testing. In this concluding section, we briefly comment on two avenues to synthesize our critique, by engaging with the two respective levels of policy effectiveness that have been explored in this paper.

Effective policy design spaces: situating capacity in theories of the policy process

A central theme in the policy design literature, which pervades all studies covered in this review, is that an enabling design space provides a platform for successful policy design, as such spaces are supported by significant capacity endowments, which not only improve policy deliberation but also allows designers to best navigate changing and often volatile design contexts (Howlett & Mukherjee, 2018a , 2018b ; Howlett et al., 2018 ; Peters et al., 2018 ; Rahman et al., 2019 ). However, most of this discussion remains largely divorced from mainstream theories and frameworks of the policy process, especially those that explain policy formulation and deliberation styles of governments. If our goal is to advance our understanding of effective design spaces, and what capacities engender them, we need to locate capacity within frameworks and theories of the policy process that are focused on them. For instance, interrogating the role of capacity in incrementalism, the policy narrative framework, or the advocacy coalition framework can generate theoretically grounded propositions and empirical testing on specific mechanisms through which capacity shapes design spaces.

Effective instrument mixes and programs: developing capacity as an independent variable

Another avenue to engage with questions relating to hierarchies, complementarities and temporal dynamics of specific types of capacities raised earlier in this paper is to explicitly canvass policy capacity as a system of independent variables, and to examine its causal impact on policy outcomes. However, as Peters ( 2020 ) states, this is challenging to do especially in the context of policy design as its impact is intermediated by many exogenous factors (Peters, 2020 ). And, as has been noted earlier, the links between specific types of capacities and how they are empirically operationalized are not always clear. Nonetheless, these methodological shortcomings can be managed to some extent by through in-depth critical case studies (see Yee & Liu, 2021 ), or focusing on comparisons among most similar cases (see Yan & Saguin, 2021 ), and avoiding sweeping comparisons that are characteristic in studies of comparative public policy. Similarly, limitations around how capacity is empirically operationalized can be managed by encouraging problem or policy-specific capacity studies. For example, Bajpai and Chong ( 2019 ) extend Wu et al.’s ( 2015 ) framework to study foreign policy capacity. Similarly, Bali and Ramesh ( 2021 ) operationalize different types of capacities to sustain health reform.

Dealing with capacity as explanatory variables would allow analysts to engage with questions around hierarchies, complementarities, and temporal dynamics raised in this review. Specifically, studies can test claims that without system-level political capacity (i.e., trust in government, accountability, legitimacy), having high operational and analytical capacities at individual and/or organizational levels may have less impact on design since mobilization of these capacities might not deliver legitimate, widely supported policies at later stages of policy design. Forthcoming research could also explore whether or not system-level political capacity is indeed the most fundamental type of capacity, while the remaining are more secondary or complementary. It may also be the case that any ‘secondary’ capacities at individual or managerial levels can be observed to contribute to solidifying political capacity at system level, and research on these directional relationships between different orders of policy capacity would greatly enrich the discussion on policy process and more specifically policy design.

These questions reveal a certain degree of agitation and urgency with wanting to find critical answers about how to match publicly salient goals with means that are effective, durable, equitable and also flexible in erratic policy contexts. Joining together concerns about capacity and how to design policy answers effectively signifies a promising, and perhaps also a vital avenue of further academic enquiry, and especially so in times marked by unprecedented public crises.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kidjie Saguin for his support in preparation of earlier versions of this paper. Kerem gratefully acknowledges the organizational support of Sabanci University and GLODEM, Koc University, as part of the paper was written during his Part-time lectureship at Sabanci University.

Availability of data and material

Code availability, declarations.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

1 We thank an anonymous referee for raising this essential point.

2 We are aware of two major caveats. Firstly, our database only covers journal articles written in English. In addition, our database excluded monographs and edited book chapters. Studies that are written in other languages and those published as monographs and edited book chapters are likely to offer additional insights to the findings in the article, which demands further research.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ishani Mukherjee, Email: gs.ude.ums@minahsi .

M. Kerem Coban, Email: [email protected] .

Azad Singh Bali, Email: [email protected] .

- Alaerts GJ. Adaptive policy implementation: Process and impact of Indonesia’s national irrigation reform 1999–2018. World Development. 2020; 129 :104880. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson JE. Public policymaking. Praeger; 1975. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ansell C, Gash A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2008; 18 (4):543–571. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ansell C, Trondal J, Øgård M, editors. Governance in turbulent times. Oxford University Press; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bajpai K, Chong B. India's foreign policy capacity. Policy Design and Practice. 2019; 2 (2):137–162. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bakır C, Çoban MK. How can a seemingly weak state in the financial services industry act strong? The role of organizational policy capacity in monetary and macroprudential policy. New Perspectives on Turkey. 2019; 61 :71–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bakvis H. Rebuilding policy capacity in the era of the fiscal divident: A report from Canada. Governance. 2002; 13 (1):71–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bali AS, Capano G, Ramesh M. Anticipating and designing for policy effectiveness. Policy and Society. 2019; 38 (1):1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bali AS, Ramesh M. Designing effective healthcare: Matching policy tools to problems in China. Public Administration and Development. 2017; 37 (1):40–508. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bali AS, Ramesh M. Policy capacity: A design perspective. In: Howlett M, Mukherjee I, editors. Routledge handbook of policy design. Routledge; 2018. pp. 331–344. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bali AS, Ramesh M. Assessing health reform: Studying tool appropriateness and critical capacities. Policy and Society. 2019; 38 (1):148–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bali AS, Ramesh M. Governing healthcare in India: A policy capacity perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences. 2021 doi: 10.1177/00208523211002605. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Banerjee AV, Bardhan PK, Somanathan R, editors. Poverty and income distribution in India. Juggernaut; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bardhan P. State and development: The need for a reappraisal of the current literature. Journal of Economic Literature. 2016; 54 (3):862–892. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baskoy T, Evans B, Shields J. Assessing policy capacity in Canada’s public services: Perspectives of deputy and assistant deputy ministers. Canadian Public Administration. 2011; 54 (2):217–234. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bengston DN, Fletcher JO, Nelson KC. Public policies for managing urban growth and protecting open space: Policy instruments and lessons learned in the United States. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2004; 69 (2–3):271–286. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernstein S, Cashore B. Complex global governance and domestic policies: Four pathways of influence. International Affairs. 2012; 88 (3):585–604. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bobrow DB. Policy design: Ubiquitous, necessary and difficult. In: Peters BG, Pierre J, editors. Handbook of public policy. Sage; 2006. pp. 75–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bobrow DB, Dryzek JS. Policy analysis by design. University of Pittsburgh Press; 1987. [ Google Scholar ]

- Borrás S. Policy learning and organizational capacities in innovation policies. Science and Public Policy. 2011; 38 (9):725–734. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bovens M, ‘t Hart P. Revisiting the study of policy failures. Journal of European Public Policy. 2016; 23 (5):653–666. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braathen NA. Instrument mixes for environmental policy: How many stones should be used to kill a bird? International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics. 2007; 1 (2):185–235. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braathen NA, Croci E. Environmental agreements used in combination with other policy instruments. In: Croci E, editor. The handbook of environmental voluntary agreements: Design, implementation and evaluation issues. Springer; 2005. pp. 335–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braun D. Organising the political coordination of knowledge and innovation policies. Science and Public Policy. 2008; 34 (4):227–239. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braun D. Lessons on the political coordination of knowledge and innovation policies. Science and Public Policy. 2008; 34 (4):289–298. [ Google Scholar ]

- Briassoulis H. Policy integration for complex environmental problems. Ashgate; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown ML. Scientific uncertainty ad learning in European Union environmental policymaking. Policy Studies Journal. 2000; 28 (3):576–596. [ Google Scholar ]

- Busuioc EM, Lodge M. The reputational basis of public accountability. Governance. 2016; 29 (2):247–263. [ Google Scholar ]

- Capano G. Policy design spaces in reforming governance in higher education: The dynamics in Italy and the Netherlands. Higher Education. 2018; 75 (4):675–694. [ Google Scholar ]

- Capano G, Howlett H, Jarvis DSL, Ramesh M, Goyal N. Mobilizing policy (in)capacity to fight COVID-19: Understanding variations in national responses. Policy and Society. 2020; 39 (3):285–308. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2020). The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: Policy tools and the current research agenda on policy mixes. Sage Open . 10.1177/2158244019900568.

- Capano G, Pavan E. Designing anticipatory policies through the use of ICTs. Policy and Society. 2019; 38 (1):96–117. [ Google Scholar ]

- Capano G, Woo JJ. Resilience and robustness in policy design: A critical appraisal. Policy Sciences. 2017; 50 (3):399–426. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cashore B, Bernstein S, Humphreys D, Visseren-Hamakers I, Rietig K. Designing stakeholder learning dialogues for effective global governance. Policy and Society. 2019; 38 (1):118–147. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chindarkar N, Howlett M, Ramesh M. Introduction to the special issue: Conceptualizing effective social policy design: Design spaces and capacity challenges. Public Administration and Developmentv. 2017; 37 (1):3–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke A, Craft J. The vestiges and vanguards of policy design in a digital context. Canadian Public Administration. 2017; 60 (4):476–497. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coban MK. Diffuse interest groups and regulatory policy change: Financial consumer protection in Turkey. Interest Groups an Advocacy. 2020; 9 (2):220–243. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coban MK. Compliance forces, domestic policy process, and international regulatory standards: Compliance with Basel III. Business and Politics. 2020; 22 (1):161–195. [ Google Scholar ]

- Compton M, ‘t Hart P. How to ‘see’ great policy successes. In: Compton M, ‘t Hart P, editors. Great policy successes. Oxford University Press; 2019. pp. 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Considine M. Thinking outside the box? Applying design theory to public policy. Politics and Policy. 2012; 40 (4):704–724. [ Google Scholar ]

- Craft J, Daku M. A comparative assessment of elite policy recruits in Canada. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017; 19 (3):207–226. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dare L. From global forests to local politics: Unwrapping the boundaries within forest certification. Australian Journal of Political Science. 2018; 53 (4):529–547. [ Google Scholar ]

- Daugbjerg C, Fraussen B, Halpin D. Interest group and policy capacity: Models of engagement, policy goods and networks. In: Wu X, Howlett M, Ramesh M, editors. Policy capacity and governance: Assessing governmental competences and capabilities in theory and practice. Springer; 2018. pp. 243–261. [ Google Scholar ]

- del Río P. Analysing the interactions between renewable energy promotion and energy efficiency support schemes: The impact of different instruments and design elements. Energy Policy. 2010; 38 (9):4978–4989. [ Google Scholar ]

- del Río, P., & Howlett, M. (2013). “Beyond the ‘Tinbergen rule’ in policy design: Matching tools and goals in policy portfolios.”SSRN Scholarly Paper. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2247238 . Last accessed 11 June 2020).

- Donahue AK, Selden SC, Ingraham PW. Measuring government management capacity: A comparative analysis of city human resources management systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2000; 10 (2):381–412. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doremus H. A policy portfolio approach to biodiversity protection on private lands. Environmental Science & Policy. 2003; 6 (3):217–232. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dorsch MJ, Flachsland C. A polycentric approach to global climate governance. Global Environmental Politics. 2017; 17 (2):45–64. [ Google Scholar ]

- Douglas, S., Hart, P. T., Ansell, C., Anderson, L., Flinders, M., Head, B., & Moynihan, D. (2019). Towards positive public administration: A manifesto . Available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336362499_Towards_Positive_Public_Administration_A_Manifesto .

- Dunlop CA. Organizational political capacity as learning. Policy and Society. 2015; 34 (4–5):259–270. [ Google Scholar ]

- Giest S. Big data for policymaking: Fad or fasttrack? Policy Sciences. 2017; 50 (3):367–382. [ Google Scholar ]

- Giest S, Mukherjee I. Behavioral instruments in renewable energy and the role of big data: A policy perspective. Energy Policy. 2018; 123 :360–366. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilabert P, Lawford-Smith H. Political feasibility: A conceptual exploration. Political Studies. 2012; 60 (4):809–825. [ Google Scholar ]

- Golan J, Sicular T, Umapathi N. Unconditional cash transfers in China: Who benefits from the rural minimum living standard guarantee (Dibao) program? World Development. 2017; 93 :316–336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grabosky PN. Green markets: Environmental regulation by the private sector. Law and Policy. 1994; 16 (4):419–448. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grant W. Policy instruments in the common agricultural policy. West European Politics. 2010; 33 (1):22–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gunningham N, Grabosky PN, Sinclair D. Smart regulation: Designing environmental policy. Clarendon Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haas PM. Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. International Organization. 1992; 46 (1):1–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartley J, Alford J, Hughes O, Yates S. Public value and political astuteness in the work of public managers: The art of the possible. Public Administration. 2015; 93 (1):195–211. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartley K, Zhang J. Measuring policy capacity through governance indices. In: Wu X, Howlett M, Ramesh M, editors. Policy capacity and governance: Assessing governmental competences and capabilities in theory and practice. Springer; 2018. pp. 67–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hood C. Intellectual obsolescence and intellectual makeovers: Reflections on the tools of government after two decades. Governance. 2007; 20 (1):127–144. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoppe R. Institutional constraints and practical problems in deliberative and participatory policy making. Policy and Politics. 2011; 39 (2):163–186. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoppe R. Heuristics for practitioners of design: Rule-of-thumb for structuring unstructured problems. Public Policy and Administration. 2018; 33 (4):384–408. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Managing the “hollow state”: Procedural policy instruments and modern governance. Canadian Public Administration. 2000; 43 (4):412–431. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Governance modes, policy regimes and operational plans: A multi-level nested model of policy instrument choice and policy design. Policy Sciences. 2009; 42 (1):73–89. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Policy analytical capacity and evidence-based policymaking: Lessons from Canada. Canadian Public Administration. 2009; 52 (2):153–172. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Designing public policies: Principles and instruments. Routledge; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. From the ‘old’ to the ‘new’ policy design: Design thinking beyond markets and collaborative governance. Policy Sciences. 2014; 47 (3):187–207. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Policy design: What, who, how and why? In: Halpern C, Lascoumes P, Patrick LG, editors. L’instrumentation et ses effets. Presses de Sciences Po; 2014. pp. 281–315. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Policy analytical capacity: The supply and demand for policy analysis in government. Policy and Society. 2015; 34 (3–4):173–182. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. The criteria for effective policy design: Character and context in policy instrument choice. Journal of Asian Public Policy. 2018; 11 (3):245–266. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M. Dealing with the dark side of policy-making: Managing behavioural risk and volatility in policy designs. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis. 2020; 22 (6):612–625. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M, Capano G, Ramesh M. Designing for robustness: Surprise, agility and improvisation in policy design. Policy and Design. 2018; 37 (4):405–421. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M, Lejano RP. Tales from the Crypt: The rise and fall (and rebirth?) of policy design. Administration and Society. 2013; 45 (3):357–381. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M, Mukherjee I. An Asian perspective on policy instruments: Policy styles, governance modes and critical capacity challenges. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration. 2016; 38 (1):24–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Howlett M, Mukherjee I. The importance of policy design: Effective processes, tools and outcomes. In: Howlett M, Mukherjee I, editors. Routledge handbook of policy design. Routledge; 2018. pp. 3–19. [ Google Scholar ]