Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

28 Citations

72 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: a scientometric review of global trends

Mixed methods research: what it is and what it could be

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

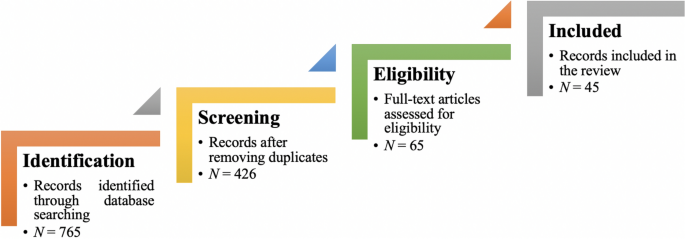

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

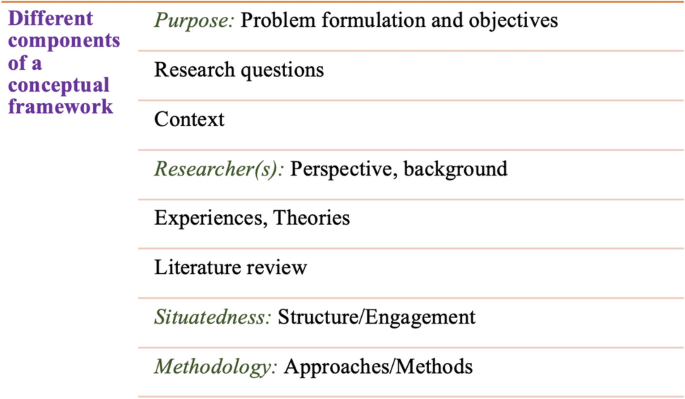

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- ESHRE Pages

- Mini-reviews

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Reasons to Publish

- Open Access

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About Human Reproduction

- About the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ESHRE

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, when to use qualitative research, how to judge qualitative research, conclusions, authors' roles, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

K. Hammarberg, M. Kirkman, S. de Lacey, Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them, Human Reproduction , Volume 31, Issue 3, March 2016, Pages 498–501, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In March 2015, an impressive set of guidelines for best practice on how to incorporate psychosocial care in routine infertility care was published by the ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guideline Development Group ( ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guideline Development Group, 2015 ). The authors report that the guidelines are based on a comprehensive review of the literature and we congratulate them on their meticulous compilation of evidence into a clinically useful document. However, when we read the methodology section, we were baffled and disappointed to find that evidence from research using qualitative methods was not included in the formulation of the guidelines. Despite stating that ‘qualitative research has significant value to assess the lived experience of infertility and fertility treatment’, the group excluded this body of evidence because qualitative research is ‘not generally hypothesis-driven and not objective/neutral, as the researcher puts him/herself in the position of the participant to understand how the world is from the person's perspective’.

Qualitative and quantitative research methods are often juxtaposed as representing two different world views. In quantitative circles, qualitative research is commonly viewed with suspicion and considered lightweight because it involves small samples which may not be representative of the broader population, it is seen as not objective, and the results are assessed as biased by the researchers' own experiences or opinions. In qualitative circles, quantitative research can be dismissed as over-simplifying individual experience in the cause of generalisation, failing to acknowledge researcher biases and expectations in research design, and requiring guesswork to understand the human meaning of aggregate data.

As social scientists who investigate psychosocial aspects of human reproduction, we use qualitative and quantitative methods, separately or together, depending on the research question. The crucial part is to know when to use what method.

The peer-review process is a pillar of scientific publishing. One of the important roles of reviewers is to assess the scientific rigour of the studies from which authors draw their conclusions. If rigour is lacking, the paper should not be published. As with research using quantitative methods, research using qualitative methods is home to the good, the bad and the ugly. It is essential that reviewers know the difference. Rejection letters are hard to take but more often than not they are based on legitimate critique. However, from time to time it is obvious that the reviewer has little grasp of what constitutes rigour or quality in qualitative research. The first author (K.H.) recently submitted a paper that reported findings from a qualitative study about fertility-related knowledge and information-seeking behaviour among people of reproductive age. In the rejection letter one of the reviewers (not from Human Reproduction ) lamented, ‘Even for a qualitative study, I would expect that some form of confidence interval and paired t-tables analysis, etc. be used to analyse the significance of results'. This comment reveals the reviewer's inappropriate application to qualitative research of criteria relevant only to quantitative research.

In this commentary, we give illustrative examples of questions most appropriately answered using qualitative methods and provide general advice about how to appraise the scientific rigour of qualitative studies. We hope this will help the journal's reviewers and readers appreciate the legitimate place of qualitative research and ensure we do not throw the baby out with the bath water by excluding or rejecting papers simply because they report the results of qualitative studies.

In psychosocial research, ‘quantitative’ research methods are appropriate when ‘factual’ data are required to answer the research question; when general or probability information is sought on opinions, attitudes, views, beliefs or preferences; when variables can be isolated and defined; when variables can be linked to form hypotheses before data collection; and when the question or problem is known, clear and unambiguous. Quantitative methods can reveal, for example, what percentage of the population supports assisted conception, their distribution by age, marital status, residential area and so on, as well as changes from one survey to the next ( Kovacs et al. , 2012 ); the number of donors and donor siblings located by parents of donor-conceived children ( Freeman et al. , 2009 ); and the relationship between the attitude of donor-conceived people to learning of their donor insemination conception and their family ‘type’ (one or two parents, lesbian or heterosexual parents; Beeson et al. , 2011 ).

In contrast, ‘qualitative’ methods are used to answer questions about experience, meaning and perspective, most often from the standpoint of the participant. These data are usually not amenable to counting or measuring. Qualitative research techniques include ‘small-group discussions’ for investigating beliefs, attitudes and concepts of normative behaviour; ‘semi-structured interviews’, to seek views on a focused topic or, with key informants, for background information or an institutional perspective; ‘in-depth interviews’ to understand a condition, experience, or event from a personal perspective; and ‘analysis of texts and documents’, such as government reports, media articles, websites or diaries, to learn about distributed or private knowledge.

Qualitative methods have been used to reveal, for example, potential problems in implementing a proposed trial of elective single embryo transfer, where small-group discussions enabled staff to explain their own resistance, leading to an amended approach ( Porter and Bhattacharya, 2005 ). Small-group discussions among assisted reproductive technology (ART) counsellors were used to investigate how the welfare principle is interpreted and practised by health professionals who must apply it in ART ( de Lacey et al. , 2015 ). When legislative change meant that gamete donors could seek identifying details of people conceived from their gametes, parents needed advice on how best to tell their children. Small-group discussions were convened to ask adolescents (not known to be donor-conceived) to reflect on how they would prefer to be told ( Kirkman et al. , 2007 ).

When a population cannot be identified, such as anonymous sperm donors from the 1980s, a qualitative approach with wide publicity can reach people who do not usually volunteer for research and reveal (for example) their attitudes to proposed legislation to remove anonymity with retrospective effect ( Hammarberg et al. , 2014 ). When researchers invite people to talk about their reflections on experience, they can sometimes learn more than they set out to discover. In describing their responses to proposed legislative change, participants also talked about people conceived as a result of their donations, demonstrating various constructions and expectations of relationships ( Kirkman et al. , 2014 ).

Interviews with parents in lesbian-parented families generated insight into the diverse meanings of the sperm donor in the creation and life of the family ( Wyverkens et al. , 2014 ). Oral and written interviews also revealed the embarrassment and ambivalence surrounding sperm donors evident in participants in donor-assisted conception ( Kirkman, 2004 ). The way in which parents conceptualise unused embryos and why they discard rather than donate was explored and understood via in-depth interviews, showing how and why the meaning of those embryos changed with parenthood ( de Lacey, 2005 ). In-depth interviews were also used to establish the intricate understanding by embryo donors and recipients of the meaning of embryo donation and the families built as a result ( Goedeke et al. , 2015 ).

It is possible to combine quantitative and qualitative methods, although great care should be taken to ensure that the theory behind each method is compatible and that the methods are being used for appropriate reasons. The two methods can be used sequentially (first a quantitative then a qualitative study or vice versa), where the first approach is used to facilitate the design of the second; they can be used in parallel as different approaches to the same question; or a dominant method may be enriched with a small component of an alternative method (such as qualitative interviews ‘nested’ in a large survey). It is important to note that free text in surveys represents qualitative data but does not constitute qualitative research. Qualitative and quantitative methods may be used together for corroboration (hoping for similar outcomes from both methods), elaboration (using qualitative data to explain or interpret quantitative data, or to demonstrate how the quantitative findings apply in particular cases), complementarity (where the qualitative and quantitative results differ but generate complementary insights) or contradiction (where qualitative and quantitative data lead to different conclusions). Each has its advantages and challenges ( Brannen, 2005 ).

Qualitative research is gaining increased momentum in the clinical setting and carries different criteria for evaluating its rigour or quality. Quantitative studies generally involve the systematic collection of data about a phenomenon, using standardized measures and statistical analysis. In contrast, qualitative studies involve the systematic collection, organization, description and interpretation of textual, verbal or visual data. The particular approach taken determines to a certain extent the criteria used for judging the quality of the report. However, research using qualitative methods can be evaluated ( Dixon-Woods et al. , 2006 ; Young et al. , 2014 ) and there are some generic guidelines for assessing qualitative research ( Kitto et al. , 2008 ).

Although the terms ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’ are contentious among qualitative researchers ( Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ) with some preferring ‘verification’, research integrity and robustness are as important in qualitative studies as they are in other forms of research. It is widely accepted that qualitative research should be ethical, important, intelligibly described, and use appropriate and rigorous methods ( Cohen and Crabtree, 2008 ). In research investigating data that can be counted or measured, replicability is essential. When other kinds of data are gathered in order to answer questions of personal or social meaning, we need to be able to capture real-life experiences, which cannot be identical from one person to the next. Furthermore, meaning is culturally determined and subject to evolutionary change. The way of explaining a phenomenon—such as what it means to use donated gametes—will vary, for example, according to the cultural significance of ‘blood’ or genes, interpretations of marital infidelity and religious constructs of sexual relationships and families. Culture may apply to a country, a community, or other actual or virtual group, and a person may be engaged at various levels of culture. In identifying meaning for members of a particular group, consistency may indeed be found from one research project to another. However, individuals within a cultural group may present different experiences and perceptions or transgress cultural expectations. That does not make them ‘wrong’ or invalidate the research. Rather, it offers insight into diversity and adds a piece to the puzzle to which other researchers also contribute.

In qualitative research the objective stance is obsolete, the researcher is the instrument, and ‘subjects’ become ‘participants’ who may contribute to data interpretation and analysis ( Denzin and Lincoln, 1998 ). Qualitative researchers defend the integrity of their work by different means: trustworthiness, credibility, applicability and consistency are the evaluative criteria ( Leininger, 1994 ).

Trustworthiness

A report of a qualitative study should contain the same robust procedural description as any other study. The purpose of the research, how it was conducted, procedural decisions, and details of data generation and management should be transparent and explicit. A reviewer should be able to follow the progression of events and decisions and understand their logic because there is adequate description, explanation and justification of the methodology and methods ( Kitto et al. , 2008 )

Credibility

Credibility is the criterion for evaluating the truth value or internal validity of qualitative research. A qualitative study is credible when its results, presented with adequate descriptions of context, are recognizable to people who share the experience and those who care for or treat them. As the instrument in qualitative research, the researcher defends its credibility through practices such as reflexivity (reflection on the influence of the researcher on the research), triangulation (where appropriate, answering the research question in several ways, such as through interviews, observation and documentary analysis) and substantial description of the interpretation process; verbatim quotations from the data are supplied to illustrate and support their interpretations ( Sandelowski, 1986 ). Where excerpts of data and interpretations are incongruent, the credibility of the study is in doubt.

Applicability

Applicability, or transferability of the research findings, is the criterion for evaluating external validity. A study is considered to meet the criterion of applicability when its findings can fit into contexts outside the study situation and when clinicians and researchers view the findings as meaningful and applicable in their own experiences.

Larger sample sizes do not produce greater applicability. Depth may be sacrificed to breadth or there may be too much data for adequate analysis. Sample sizes in qualitative research are typically small. The term ‘saturation’ is often used in reference to decisions about sample size in research using qualitative methods. Emerging from grounded theory, where filling theoretical categories is considered essential to the robustness of the developing theory, data saturation has been expanded to describe a situation where data tend towards repetition or where data cease to offer new directions and raise new questions ( Charmaz, 2005 ). However, the legitimacy of saturation as a generic marker of sampling adequacy has been questioned ( O'Reilly and Parker, 2013 ). Caution must be exercised to ensure that a commitment to saturation does not assume an ‘essence’ of an experience in which limited diversity is anticipated; each account is likely to be subtly different and each ‘sample’ will contribute to knowledge without telling the whole story. Increasingly, it is expected that researchers will report the kind of saturation they have applied and their criteria for recognising its achievement; an assessor will need to judge whether the choice is appropriate and consistent with the theoretical context within which the research has been conducted.

Sampling strategies are usually purposive, convenient, theoretical or snowballed. Maximum variation sampling may be used to seek representation of diverse perspectives on the topic. Homogeneous sampling may be used to recruit a group of participants with specified criteria. The threat of bias is irrelevant; participants are recruited and selected specifically because they can illuminate the phenomenon being studied. Rather than being predetermined by statistical power analysis, qualitative study samples are dependent on the nature of the data, the availability of participants and where those data take the investigator. Multiple data collections may also take place to obtain maximum insight into sensitive topics. For instance, the question of how decisions are made for embryo disposition may involve sampling within the patient group as well as from scientists, clinicians, counsellors and clinic administrators.

Consistency

Consistency, or dependability of the results, is the criterion for assessing reliability. This does not mean that the same result would necessarily be found in other contexts but that, given the same data, other researchers would find similar patterns. Researchers often seek maximum variation in the experience of a phenomenon, not only to illuminate it but also to discourage fulfilment of limited researcher expectations (for example, negative cases or instances that do not fit the emerging interpretation or theory should be actively sought and explored). Qualitative researchers sometimes describe the processes by which verification of the theoretical findings by another team member takes place ( Morse and Richards, 2002 ).

Research that uses qualitative methods is not, as it seems sometimes to be represented, the easy option, nor is it a collation of anecdotes. It usually involves a complex theoretical or philosophical framework. Rigorous analysis is conducted without the aid of straightforward mathematical rules. Researchers must demonstrate the validity of their analysis and conclusions, resulting in longer papers and occasional frustration with the word limits of appropriate journals. Nevertheless, we need the different kinds of evidence that is generated by qualitative methods. The experience of health, illness and medical intervention cannot always be counted and measured; researchers need to understand what they mean to individuals and groups. Knowledge gained from qualitative research methods can inform clinical practice, indicate how to support people living with chronic conditions and contribute to community education and awareness about people who are (for example) experiencing infertility or using assisted conception.

Each author drafted a section of the manuscript and the manuscript as a whole was reviewed and revised by all authors in consultation.

No external funding was either sought or obtained for this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Beeson D , Jennings P , Kramer W . Offspring searching for their sperm donors: how family types shape the process . Hum Reprod 2011 ; 26 : 2415 – 2424 .

Google Scholar

Brannen J . Mixing methods: the entry of qualitative and quantitative approaches into the research process . Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005 ; 8 : 173 – 184 .

Charmaz K . Grounded Theory in the 21st century; applications for advancing social justice studies . In: Denzin NK , Lincoln YS (eds). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research . California : Sage Publications Inc. , 2005 .

Google Preview

Cohen D , Crabtree B . Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations . Ann Fam Med 2008 ; 6 : 331 – 339 .

de Lacey S . Parent identity and ‘virtual’ children: why patients discard rather than donate unused embryos . Hum Reprod 2005 ; 20 : 1661 – 1669 .

de Lacey SL , Peterson K , McMillan J . Child interests in assisted reproductive technology: how is the welfare principle applied in practice? Hum Reprod 2015 ; 30 : 616 – 624 .

Denzin N , Lincoln Y . Entering the field of qualitative research . In: Denzin NK , Lincoln YS (eds). The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues . Thousand Oaks : Sage , 1998 , 1 – 34 .

Dixon-Woods M , Bonas S , Booth A , Jones DR , Miller T , Shaw RL , Smith JA , Young B . How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective . Qual Res 2006 ; 6 : 27 – 44 .

ESHRE Psychology and Counselling Guideline Development Group . Routine Psychosocial Care in Infertility and Medically Assisted Reproduction: A Guide for Fertility Staff , 2015 . http://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Psychosocial-care-guideline.aspx .

Freeman T , Jadva V , Kramer W , Golombok S . Gamete donation: parents' experiences of searching for their child's donor siblings or donor . Hum Reprod 2009 ; 24 : 505 – 516 .

Goedeke S , Daniels K , Thorpe M , Du Preez E . Building extended families through embryo donation: the experiences of donors and recipients . Hum Reprod 2015 ; 30 : 2340 – 2350 .

Hammarberg K , Johnson L , Bourne K , Fisher J , Kirkman M . Proposed legislative change mandating retrospective release of identifying information: consultation with donors and Government response . Hum Reprod 2014 ; 29 : 286 – 292 .

Kirkman M . Saviours and satyrs: ambivalence in narrative meanings of sperm provision . Cult Health Sex 2004 ; 6 : 319 – 336 .

Kirkman M , Rosenthal D , Johnson L . Families working it out: adolescents' views on communicating about donor-assisted conception . Hum Reprod 2007 ; 22 : 2318 – 2324 .

Kirkman M , Bourne K , Fisher J , Johnson L , Hammarberg K . Gamete donors' expectations and experiences of contact with their donor offspring . Hum Reprod 2014 ; 29 : 731 – 738 .

Kitto S , Chesters J , Grbich C . Quality in qualitative research . Med J Aust 2008 ; 188 : 243 – 246 .

Kovacs GT , Morgan G , Levine M , McCrann J . The Australian community overwhelmingly approves IVF to treat subfertility, with increasing support over three decades . Aust N Z J Obstetr Gynaecol 2012 ; 52 : 302 – 304 .

Leininger M . Evaluation criteria and critique of qualitative research studies . In: Morse J (ed). Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods . Thousand Oaks : Sage , 1994 , 95 – 115 .

Lincoln YS , Guba EG . Naturalistic Inquiry . Newbury Park, CA : Sage Publications , 1985 .

Morse J , Richards L . Readme First for a Users Guide to Qualitative Methods . Thousand Oaks : Sage , 2002 .

O'Reilly M , Parker N . ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research . Qual Res 2013 ; 13 : 190 – 197 .

Porter M , Bhattacharya S . Investigation of staff and patients' opinions of a proposed trial of elective single embryo transfer . Hum Reprod 2005 ; 20 : 2523 – 2530 .

Sandelowski M . The problem of rigor in qualitative research . Adv Nurs Sci 1986 ; 8 : 27 – 37 .

Wyverkens E , Provoost V , Ravelingien A , De Sutter P , Pennings G , Buysse A . Beyond sperm cells: a qualitative study on constructed meanings of the sperm donor in lesbian families . Hum Reprod 2014 ; 29 : 1248 – 1254 .

Young K , Fisher J , Kirkman M . Women's experiences of endometriosis: a systematic review of qualitative research . J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2014 ; 41 : 225 – 234 .

- conflict of interest

- credibility

- qualitative research

- quantitative methods

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2350

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 18 May 2020

What feedback do reviewers give when reviewing qualitative manuscripts? A focused mapping review and synthesis

- Oliver Rudolf HERBER ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3041-4098 1 ,

- Caroline BRADBURY-JONES 2 ,

- Susanna BÖLING 3 ,

- Sarah COMBES 4 ,

- Julian HIRT 5 ,

- Yvonne KOOP 6 ,

- Ragnhild NYHAGEN 7 ,

- Jessica D. VELDHUIZEN 8 &

- Julie TAYLOR 2 , 9

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 20 , Article number: 122 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

17 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Peer review is at the heart of the scientific process. With the advent of digitisation, journals started to offer electronic articles or publishing online only. A new philosophy regarding the peer review process found its way into academia: the open peer review. Open peer review as practiced by BioMed Central ( BMC ) is a type of peer review where the names of authors and reviewers are disclosed and reviewer comments are published alongside the article. A number of articles have been published to assess peer reviews using quantitative research. However, no studies exist that used qualitative methods to analyse the content of reviewers’ comments.

A focused mapping review and synthesis (FMRS) was undertaken of manuscripts reporting qualitative research submitted to BMC open access journals from 1 January – 31 March 2018. Free-text reviewer comments were extracted from peer review reports using a 77-item classification system organised according to three key dimensions that represented common themes and sub-themes. A two stage analysis process was employed. First, frequency counts were undertaken that allowed revealing patterns across themes/sub-themes. Second, thematic analysis was conducted on selected themes of the narrative portion of reviewer reports.

A total of 107 manuscripts submitted to nine open-access journals were included in the FMRS. The frequency analysis revealed that among the 30 most frequently employed themes “writing criteria” (dimension II) is the top ranking theme, followed by comments in relation to the “methods” (dimension I). Besides that, some results suggest an underlying quantitative mindset of reviewers. Results are compared and contrasted in relation to established reporting guidelines for qualitative research to inform reviewers and authors of frequent feedback offered to enhance the quality of manuscripts.

Conclusions

This FMRS has highlighted some important issues that hold lessons for authors, reviewers and editors. We suggest modifying the current reporting guidelines by including a further item called “Degree of data transformation” to prompt authors and reviewers to make a judgment about the appropriateness of the degree of data transformation in relation to the chosen analysis method. Besides, we suggest that completion of a reporting checklist on submission becomes a requirement.

Peer Review reports

Peer review is at the heart of the scientific process. Reviewers independently examine a submitted manuscript and then recommend acceptance, rejection or – most frequently – revisions to be made before it gets published [ 1 ]. Editors rely on peer review to make decisions on which submissions warrant publication and to enhance quality standards. Typically, each manuscript is reviewed by two or three reviewers [ 2 ] who are chosen for their knowledge and expertise regarding the subject or methodology [ 3 ]. The history of peer review, often regarded as a “touchstone of modern evaluation of scientific quality” [ 4 ] is relatively short. For example, the British Medical Journal (now the BMJ ) was a pioneer when it established a system of external reviewers in 1893. But it was in the second half of the twentieth century that employing peers as reviewers became custom [ 5 ]. Then, in 1973 the prestigious scientific weekly Nature introduced a rigorous formal peer review system for every paper it printed [ 6 ].

Despite ever-growing concerns about its effectiveness, fairness and reliability [ 4 , 7 ], peer review as a central part of academic self-regulation is still considered the best available practice [ 8 ]. With the advent of digitisation in the late 1990s, scholarly publishing has changed dramatically with many journals starting to offer print as well as electronic articles or publishing online only [ 9 ]. The latter category includes for-profit journals such as BioMed Central ( BMC ) that have been online since their inception in 1999, with an ever evolving portfolio of currently over 300 peer-reviewed journals.

As compared to traditional print journals where individuals or libraries need to pay a fee for an annual subscription or for reading a specific article, open access journals such as BMC, PLoS ONE or BMJ Open are permanently free for everyone to read and download since the cost of publishing is paid by the author or an entity such as the university. Many, but not all, open access journals impose an article processing charge on the author, also known as the gold open access route, to cover the cost of publication. Depending on the journal and the publisher, article processing charges can range significantly between US$100 and US$5200 per article [ 10 , 11 ].

In the digital age, a new philosophy regarding the peer review process found its way into academia, questioning the anonymity of the closed system of peer-review as contrary to the demands for transparency [ 1 ]. The issue of reviewer bias, especially concerning gender and affiliation [ 12 ], led not only to the establishment of double-blind review but also to its extreme opposite: the open peer review system [ 8 ]. Although the term ‘open peer review’ has no standardised definition, scholars use the term to indicate that the identities of the authors and reviewers are disclosed and that reviewer reports are openly available [ 13 ]. In the late 1990s, the BMJ changed from a closed system of peer review to an open system [ 14 , 15 ]. During the same time, other publishers such as some journals in BMC followed the example of opening up their peer review.

While peer review reports have long been hidden from the public gaze [ 16 , 17 ], opening up the closed peer review system allows researchers to access reviewer comments, thus making it possible to study them. Since then, a number of articles have been published to assess reviews using quantitative research methods. For example, Landkroon et al. [ 18 ] assessed the quality of 247 reviews of 119 original articles using a 5-point Likert scale. Similarly, Henly and Dougherty [ 19 ] developed and applied a grading scale to assess the narrative portion of 464 reviews of 203 manuscripts using descriptive statistics. The retrospective cohort study by van Lent et al. [ 20 ] assessed peer review comments on drug trials from 246 manuscripts to investigate whether there is a relationship between the content of these comments and sponsorship using a generalised linear mixed model. Most recently, Davis et al. [ 21 ] evaluated reviewer grading forms for surgical journals with higher impact factors and compared them to surgical journals with lower impact factors using Fisher’s exact test.

Despite the readily available reviewer comments that are published alongside the final article of many open access journals, to the best of our knowledge no studies exist to date that used – besides quantitative methods – also qualitative methods to analyse the content of reviewers’ comments. Identifying (negative) reviewer comments will help authors to pay particular attention to these aspects and assist prospective qualitative researchers to understand the most common pitfalls when preparing their manuscript for submission. Thus, the aim of the study was to appraise the quality and nature of reviewers’ feedback in order to understand how reviewers engage with and influence the development of a qualitative manuscript. Our focus on qualitative research can be explained by the fact that we are passionate qualitative researchers with a history in determining the state of qualitative research in health and social science literature [ 22 ]. The following research questions were answered: (1) What are the frequencies of certain commentary types in manuscripts reporting on qualitative research? and (2) What are the nature of reviewers’ comments made on manuscripts reporting on qualitative research?

We conducted a focused mapping review and synthesis (FMRS) [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Most forms of review aim for breadth and exhaustive searches, but the FMRS searches within specific, pre-determined journals. While Platt [ 26 ] observed that ‘a number of studies have used samples of journal articles’, the distinctive feature of the FMRS is the purposive selection of journals. These are chosen for their likelihood to contain articles relevant to the field of inquiry – in this case qualitative research published in open access journals that operate an open peer-review process that involves posting the reviewer’s reports. It is these reports that we have analysed using thematic analysis techniques [ 27 ].

Currently there are over 70 BMC journals that have adopted open peer-review. The FMRS focused on reviewers’ reports published during the first quarter of 2018. Journals were selected using a three-stage process. First, we produced a list with all BMC journals that operate an open peer review process and will publish qualitative research articles ( n = 62). Second, from this list we selected journals that are general fields of practice and non-disease specific ( n = 15). Third, to ensure a sufficient number of qualitative articles, we excluded journals with less than 25 hits on the search term “qualitative” for the year 2018 (search date: 16 July 2018) because chances were considered too slim to contain sufficient articles of interest. At the end of the selection process, the following nine BMC journals were included in our synthesis: (1) BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine , (2) BMC Family Practice , (3) BMC Health Services Research , (4) BMC Medical Education , (5) BMC Medical Ethics , (6) BMC Nursing , (7) BMC Public Health , (8) Health Research Policy and Systems , and (9) Implementation Science . Since these journals represent different subjects, a variety of qualitative papers written for different audiences was captured. Every article published within the timeframe was scrutinised against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1 ).

Development of the data extraction sheet

A validated instrument for the classification of reviewer comments does not exist [ 20 ]. Hence, a detailed classification system was developed and pilot tested considering previous research [ 20 ]. Our newly developed data extraction sheet consists of a 77-item classification system organised according to three dimensions: (1) scientific/technical content, (2) writing criteria/representation, and (3) technical criteria. It represents themes and sub-themes identified by reading reviewer comments from twelve articles published in open peer-review journals. For the development of the data extraction sheet, we randomly selected four articles containing qualitative research from each of the following three journals published between 2017 and 2018: BMC Nursing , BMC Family Practice and BMJ Open . We then analysed the reviews of manuscripts by systematically coding and categorising the reviewers’ free-text comments. Following the recommendation by Shashok [ 28 ], we initially organised the reviewer’s comments along two main dimensions, i.e., scientific content and writing criteria. Shashok [ 28 ] argues that when peer reviewers confuse content and writing, their feedback can be misunderstood by authors who may modify texts in unintentional ways to the detriment of the manuscript.

To check the comprehensiveness of our classification system, provisional themes and sub-themes were piloted using reviewer comments we had previously received from twelve of our own manuscripts that had been submitted to journals that operate blind peer-review. We wanted to account for potential differences in reviewers’ feedback (open vs. blind review). As a result of this quality enhancement procedure, three sub-themes and a further dimension (‘technical criteria’) were added. For reasons of clarity and comprehensibility, the dimension ‘scientific content’ was subdivided following the IMRaD structure. IMRaD is the most common organisational structure of an original research article comprising I ntroduction, M ethods, R esults a nd D iscussion [ 29 ]. Anchoring examples were provided for each theme/sub-theme. To account for reviewer comments unrelated to the IMRaD structure, a sub-category called ‘generic codes’ was created to collect more general comments. When reviewer comments could not be assigned to any of the existing themes/sub-themes, they were noted as “Miscellaneous”. Table 2 shows the final data extraction sheet including anchoring examples.

Data extraction procedure

Data extraction was accomplished by six doctoral students (coders). On average, each coder was allocated 18 articles. After reading the reviews, coders independently classified each comment using the classification system. In line with Day et al. [ 30 ] a reviewer comment was defined as “ a distinct statement or idea found in a review, regardless of whether that statement was presented in isolation or was included in a paragraph that contained several statements. ” Editor comments were not included. Reviewers’ comments were copied and pasted into the most appropriate item of the classification system following a set of pre-defined guidelines. For example, a reviewer comment could only be coded once by assigning it to the most appropriate theme/sub-theme. A separate data extraction sheet was used for each article. For the purpose of calibration, the first completed data extraction sheet from each coder together with the reviewer’s comments was sent to the study coordinator (ORH) who provided feedback on classifying the reviewer comments. The aim of the calibration was to ensure that all coders were working within the same parameters of understanding, to discuss the subtleties of the judgement process and create consensus regarding classifications. Although the assignment to specific themes/sub-themes is, by nature, a subjective process, difficult to assign comments were classified following discussion and agreement between coder and study coordinator to ensure reliability. Once all data extraction was completed, two experienced qualitative researchers (CB-J, JT) independently undertook a further calibration exercise of a random sub-sample of 20% of articles ( n = 22) to ensure consistency across coders. Articles were selected using a random number generator. For these 22 articles, classification discrepancies were resolved by consensus between coders and experienced researchers. Finally, all individual data extraction sheets were collated to create a comprehensive Excel spreadsheet with over 8000 cells that allowed tallying the reviewer’s comments across manuscripts for the purpose of data analysis. For each manuscript, a reviewer could have several remarks related to one type of comment. However, each type of comment was scored only once per category.

Finally, reviewer comments were ‘quantitized’ [ 31 ] by applying programming language (Python) to Jupyter Notebook, an open-source web application, to perform frequency counts of free-text comments regarding the 77 items. Among other data manipulation, we sorted elements of arrays in descending order of frequency using Pandas, counted the number of studies in which a certain theme/sub-theme occurred, conducted distinct word searches using NLTK 3 or grouped data according to certain criteria. The calculation of frequencies is a way to unite the empirical precision of quantitative research with the descriptive precision of qualitative research [ 32 ]. This quantitative transformation of qualitative data allowed extracting more meaning from our spreadsheet through revealing patterns across themes/sub-themes, thus giving indicators about which of them to analyse using thematic analysis.

A total of 109 manuscripts submitted to nine open-access journals were included in the FMRS. When scrutinising the peer review reports, we noticed that on one occasion the reviewer’s comments were missing [ 33 ]. For the remaining 108 manuscripts, reviewer comments were accessible via the journal’s pre-publication history. On close inspection, however, it became apparent that one article did not contain qualitative research, thus leaving ultimately 107 articles to work with ( supplementary file ). Considering that each manuscript could potentially be reviewed by multiple reviewers and underwent at least one round of revision, the total number of reviewer reports analysed amounted to 347 containing collectively 1703 reviewer comments. The level of inter-rater agreement for the 22 articles included in the calibration exercise was 97%. Disagreement was, for example, in relation to coding a comment as “miscellaneous” or as “confirmation/approval (from reviewer)”. For 18 out of 22 articles, there was 100% agreement for all types of comments.

Variation in number of reviewers

The number of reviewers invited by the editor to review a submitted manuscript varied greatly within and among journals. While the majority of manuscripts across journals had been reviewed by two to three reviewers, there were also significant variations. For example, the manuscript submitted to BMC Medical Education by Burgess et al. [ 34 ] had been reviewed by five reviewers whereas the manuscript submitted to BMC Public Health by Lee and Lee [ 35 ] had been reviewed by one reviewer only. Even within journals there was a huge variation. Among our sample, BMC Public Health had the greatest variance ranging from one to four reviewers. Besides, it was noted that additional reviewers were called in not until the second or even third revision of the manuscript. A summary of key information on journals included in the FMRS is provided in Table 3 .

“Quantitizing” reviewer comments

The frequency analysis revealed that the number of articles in which a certain theme/sub-theme occurred ranged from 1 to 79. Across all 107 articles, the types of comments most frequently reported were in relation to generic themes. Reviewer comments regarding “Adding information/detail/nuances”, “Clarification needed”, “Further explanation required” and “Confirmation/approval (from reviewer)” were used in 79, 79, 66 and 63 articles, respectively. The four most frequently used themes/sub-themes are composed of generic codes from dimension I (“Scientific/technical content”). Leaving all generic codes aside, it became apparent that among the 30 most frequently employed themes “Writing criteria” (dimension II) is the top ranking theme, followed by comments in relation to the “Methods” (dimension I) (Table 4 ).

Subsequently, we present key qualitative findings regarding “Confirmation/approval from reviewers” (generic), “Sampling” and “Analysis process” (methods), “Robust/rich data analysis and “Themes/sub-themes” (results) as well as findings that suggest an underlying quantitative mindset of the reviewers.

Confirmation/approval from reviewers (generic)

The theme “confirmation/approval from reviewers” ranks third among the top 30 categories. A total of 63 manuscripts contained at least one reviewer comment related to this theme. Overall, reviewers maintained a respectful and affirmative rhetoric when providing feedback. The vast majority of reviewers began their report by stating that the manuscript was well written. The following is a typical example:

“Overall, the paper is well written, and theoretically informed.” Article #14.

Reviewers then continued to add explicit praise for aspects or sections that were particularly innovative and/or well constructed before they started to put forward any negative feedback.

Sampling (methods)

Across all 107 articles there were 34 reviewer comments in relation to the sampling technique(s). Two major categories were identified: (1) composition of the sample and (2) identification and justification of selected participants. Regarding the former, reviewers raised several concerns about how the sample was composed. For instance, one reviewer wanted to know the reason for female predominance in the study and why an entire focus group was composed of females only. Another reviewer expressed strong criticism on the composition of the sample since only young, educated and non-minority white British participants were included in the study. The reviewer commented:

“ So a typical patient was young, educated and non-minority White British? The research studies these days should be inclusive of diverse types of patients and excluding patients because of their age and ethnicity is extremely concerning to me. This assumption that these individuals will “find it more difficult to complete questionnaires” is concerning ” Article #40.