Home > ICSK > IJESAB > Vol. 2 > Iss. 12 (2020)

Case Presentation for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

Hannah Lattanzio , University of Illinois at Chicago Follow Vered Arbel , University of Illinois at Chicago Follow Terry Nicola Tal Amasay Follow

CASE HISTORY : The patient is a fourteen-year-old female who presented to the clinic for bilateral hip and lumbar back pain. She stated that the pain has been present for approximately seven months and described it as a deep ache in the low back and both hips anteriorly. The patient said she plays a variety of sports but denies any specific event that could contribute to her pain. She stated her pain is worse with prolonged walking, standing, and sitting. Additionally, the patient mentioned her first menstrual cycle lasted fifty-six days and she has since not had any following menses, indicating secondary amenorrhea. Secondary amenorrhea is characterized by the cessation of irregular menses for six months and is commonly caused by hormonal imbalances. PHYSICAL EXAM : Examination of the hip, abdomen, and back did not demonstrate any deformities. She had tenderness to palpation at the mid-abdomen and at the insertion of the hip flexors, at the ASIS and AIIS bilaterally. Her patellar reflex was normal and 5/5 strength in hip flexion, extension, and abduction was observed along with full range of motion of both hips. FABER and FADIR tests were conducted and resulted in a positive sign of pain for both tests. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES : Hip dysplasia, Slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, Femoroacetabular impingement, and Snapping hip. TESTS & RESULTS : Patient had an x-ray of both hips that were negative for tissue abnormalities. A pelvic MRI suggested small areas of sub-chondral sclerosis and possible polycystic ovaries. FINAL DIAGNOSIS : Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). DISCUSSION : PCOS is a common endocrine disorder that effects an estimated 10% of women between the ages of fifteen to forty-four, though it is commonly diagnosed in adolescence to early twenties. PCOS is diagnosed when two of the following criteria are evident: menstrual irregularity, polycystic ovaries and/or symptoms of androgen excess. Though pain is not an indicator of PCOS, it is not uncommon, and presentation varies widely to include abdominal, anterior pelvic, and low back pain. PCOS is believed to be caused by genetics but is greatly influenced by lifestyle factors and is associated with many morbidities including obesity, insulin resistance, and depression. Management of PCOS consists of controlling the symptoms of androgen excess and/or the absence of ovulation, and to reduce the chances of long-term complications such as infertility, metabolic syndrome, and type two diabetes. Oral contraceptives are the most common treatment for menstrual irregularity in adolescents. Androgen excess is managed with a combination of cosmetic management, oral contraceptives, and anti-androgen therapy, such as cyproterone acetate. Prevention of long-term complications include diet and lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of developing type two diabetes. Metformin may also be an effective treatment for both type two diabetes and androgen excess. OUTCOME OF THE CASE : Patient was referred to physical therapy to include protective range of motion and exercise of hip flexors. She continued to take Diclofenac for pain. RETURN TO ACTIVITY AND FURTHER FOLLOW-UP : The patient will follow-up with endocrinology and gynecologist for questionable polycystic ovarian syndrome due to polycystic ovaries present on the hip MRI and elevated testosterone levels. An x-ray without contrast of bilateral hips will be obtained to evaluate bony anatomy and she will return to the clinic in 4-6 weeks to follow-up on symptoms and discuss the imaging findings.

Recommended Citation

Lattanzio, Hannah; Arbel, Vered; Nicola, Terry; and Amasay, Tal (2020) "Case Presentation for Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome," International Journal of Exercise Science: Conference Proceedings : Vol. 2: Iss. 12, Article 128. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijesab/vol2/iss12/128

Since February 17, 2020

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

- Journal Home

- Editorial Board

- Submit Abstract

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Custom Email Notices or RSS

Advanced Search

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Impact of polycystic ovary syndrome on quality of life of women in correlation to age, basal metabolic index, education and marriage

Roles Investigation

Affiliation Department of Pharmacology, Santosh Medical College, Santosh University, Ghaziabad, Uttar-Pradesh, India

Roles Data curation

Affiliation Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India

Roles Project administration

* E-mail: [email protected] (KD); [email protected] (MSA)

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation College of Pharmacy, King Khalid University, Abha, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- Fauzia Tabassum,

- Chandra Jyoti,

- Hemali Heidi Sinha,

- Kavita Dhar,

- Md Sayeed Akhtar

- Published: March 10, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486

- Reader Comments

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the major endocrine related disorder in young age women. Physical appearance, menstrual irregularity as well as infertility are considered as a sole cause of mental distress affecting health-related quality of life (HRQOL). This prospective case-control study was conducted among 100 PCOS and 200 healthy control cases attending tertiary care set up of AIIMS, Patna during year 2017 and 2018. Pre-validated questionnaires like Short Form Health survey-36 were used for evaluating impact of PCOS in women. Multivariate analysis was applied for statistical analysis. In PCOS cases, socioeconomic status was comparable in comparison to healthy control. But, PCOS cases showed significantly decreased HRQOL. The higher age of menarche, irregular/delayed menstrual history, absence of child, were significantly altered in PCOS cases than control. Number of child, frequency of pregnancy, and miscarriage were also observed higher in PCOS cases. Furthermore, in various category of age, BMI, educational status and marital status, significant differences were observed in the different domain of SF-36 between PCOS and healthy control. Altogether, increased BMI, menstrual irregularities, educational status and marital status play a major role in altering HRQOL in PCOS cases and psychological care must be given during patient care.

Citation: Tabassum F, Jyoti C, Sinha HH, Dhar K, Akhtar MS (2021) Impact of polycystic ovary syndrome on quality of life of women in correlation to age, basal metabolic index, education and marriage. PLoS ONE 16(3): e0247486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486

Editor: Antonio Simone Laganà, University of Insubria, ITALY

Received: July 24, 2020; Accepted: January 1, 2021; Published: March 10, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Tabassum et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data cannot be shared publicly because of confidentiality. Data are available from the Ethics Committee, AIIMS, Patna for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Contact information for the ethics committee: (The Chairman, Institutional review board, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar (India), PIN-801507).

Funding: This work is supported by the Dean of Scientific Research, King Khalid University for the financial support is greatly appreciated for the general research Project under grant number [GRP/190/42], awarded to MSA.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a major endocrine disorder in young age women affecting their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and their mental well-being as well [ 1 , 2 ]. Moreover, this develop into lifelong health condition that continues far beyond the young ages and affects around 5 million young age population in the United States of America [ 3 , 4 ]. In India, PCOS has been reported to vary between racial counterparts with an estimated prevalence of 9.13% in adolescents [ 5 ]. The major changes in physical appearance, obesity, along with menstrual irregularity have been found to be the main contributing factor of psychological dilemma [ 6 – 8 ]. PCOS negative impact is always underestimated and dominates on women’s life and may lead to a risk for serious anxiety and psychological disorder [ 9 , 10 ]. Importantly, the psychological burden greatly varies with the change in geographical areas and societal perceptions (Barnard et al., 2007; Brady et al., 2009). These patients may experience characteristics of PCOS as stressful and may be at higher risk for depression and anxiety disorders and even this may lead towards suicidal tendency [ 9 , 10 ].

Clinically, PCOS is characterized by either oligoovulation or anovulation and hyperandrogenism that may cause infertility, and other related metabolic disorders [ 11 ]. This progresses to increased risk of reproductive issues like infertility endometrial cancer, gestational as well as mental disturbances [ 12 ]. However, novel treatments and therapies can then be targeted toward improving those problems, which are most important for the individual concerned [ 13 , 14 ]. Recently, increased importance has been given on understanding the impact of PCOS symptoms and in particular about the feminine identity and thus their treatment from the patients’ perspective for the better quality of life (QOL). HRQOL is a self-perceived health status as a consequence of any disease that is measured by health status questionnaires [ 15 ]. Therefore, HRQOL questionnaires like Short Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36) for PCOS, was used to understand the impact of PCOS and evaluating individual patients’ health status and monitoring and comparing disease burden [ 16 , 17 ]. The SF-36 scale leaves out important detrimental issues linked to PCOS patients such as physical and emotional symptoms associated with menses [ 16 ]. PCOS questionnaire has reasonable internal reliability, good test-retest reliability, good concurrent and discriminated validity, and a reasonable factor analysis making PCOS questionnaire a useful and promising tool for HRQOL in PCOS cases.

At present, there is a paucity of information related to PCOS among women of the reproductive age group in India, in particular, North India. Thus, considering these factors into account, this prospective study was planned to compare socioeconomic status (SDS) and association of age, body mass index (BMI), education level and marital status between PCOS and healthy control cases among the women in the reproductive age group visiting the department of gynaecology and obstetrics of tertiary care hospital.

Material and methods

Ethical approval.

Ethical approval (SU/2017/1226-3) was obtained from the institutional review board of Santosh medical college, Uttar Pradesh, India. The institutional review board of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, India, granted study site approval (176/AIIMS/PAT/IEC/2017). Informed consent form was obtained from parents or guardians of the minors (<18 years).

Study design

This prospective, cross sectional, observational study was designed and conducted in the tertiary care teaching hospital of north India.

Study setting

Patients visiting the outpatients’ department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna (India) were included in the study.

Participants

Patients diagnosed with PCOS, based on criteria derived from the 2003 ESHRE/ASRM (Rotterdam criteria) were arbitrarily enrolled in the study. PCOS is diagnosed as the presence of at least two of three of the following: 1) Oligo/anovulation, 2) hyperandrogenism, 3) Polycystic ovaries [ 18 ]. A healthy control (HC) was selected from participants of the same population and having regular menses and had no clinical features of hyperandrogenism as well as infertility.

Data sources

Data was collected after describing both written and verbal information about the study. After explaining, the informed consent form was signed by each participant and then they were requested to complete the questionnaires. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by investigators to the subjects meeting the inclusion criteria and consented for the participation into the study in three parts: Part A: Semi-structured, pre-validated questionnaires were used for collecting information on the socio-demographic, economic and reproductive history. Part B: Pre-validated SF-36 questionnaire is a standard diagnostic tool for evaluating various aspects of the HRQOL over the previous 4 weeks [ 19 ]. Its validity, sensitivity, reliability, internal consistency and stability, as well as test-retest reliability have frequently been confirmed in various studies [ 20 – 22 ]. SF-36 contains 8 domains: general health, physical functioning, and role limitations due to physical health, role limitation due to the emotional problem, body pain, social functioning, energy/fatigue and emotional well-being. The scores for each domain range from 0–100, where higher scores indicate better condition.

The sample size was estimated post assuming α-error of 0.05, power of 80%, percentage of controls having a poor quality of life to be 20% based on previous studies and odds of poor QOL among cases to be twice than among controls. Hence, a total of 100 PCOS cases and 200 healthy control cases were enrolled in the study.

Inclusion criteria

We included all diagnosed case of PCOS only, female from menarche to menopausal age between the age of 10–49 years, and those given informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Patients having cognitive or developmental disabilities/another major illness that substantially influenced the HRQOL of women, confirmed malignancy and deformities, as well as breastfeeding women were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using statistical software-Stata Version 14.0 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA). After checking for the normality condition for continuous variables, the appropriate statistical test was applied. Confounders like excessive body weight were taken into consideration. Quantitative data expressed as mean±SD, minimum and maximum followed normal and skewed distribution respectively. Analysis of covariance model (ANCOVA) was used to address potential confounders. Categorical variables expressed as frequency and percentage. Pearson Chi-Square test and Fisher exact test were used to checking the association between qualitative variables and categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate odds (95% CI) and models were robust for PCOS and other variables. Multivariable linear regression analysis was performed to observe the association between the variables. Independent t-test and One Way ANOVA used to compare normally distributed continuous variable between two and three categories respectively. Rank sum/Kruskal Wallis test used for comparing skewed continuous variables among categories and to look association between demographic categories. For all statistical tests, P-value < 0.05 is considered as statistical significant.

The outcome of socioeconomic status (SES) of a woman with PCOS and HC cases are mentioned in Table 1 . The women with PCOS and HC were comparable in respect of marital status and family type. Statistically significant differences were observed between PCOS and HC in terms of age (P<0.020), BMI (P<0.001), educational status (P<0.001), marital status (P>0.05) and work category (P<0.001). Total 97% of PCOS case was below the age of 30 years in comparison to 78% of control. Among all PCOS cases, 60% was student and almost 54% received higher education. Among the HC group, 39% was student and only 15% received higher education (P<0.001). A higher percentage of PCOS cases (16%) belong to greater BMI (>30) in comparison to HC (2%).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t001

As shown in Table 2 , among the PCOS group, a significant percentage of women (33%) has menarche at age greater than 14 years and there was no any HC cases lies in this category (P<0.001). In respect of menstrual history, PCOS cases have a higher percentage of irregular (45%) and delayed (54%) menses and this comprises a signify`cant difference (P<0.001) in comparison to HC that was 8% irregular and no any delay in menses were observed. Around 64.3% of cases of PCOS women have no child (P<0.001) in contrast to HC cases (9.5%). However, 86.67% PCOS cases have less than ≤ 2 children in comparison to HC where 69.47% have less than ≤2 children (P<0.169). In terms of pregnancy, almost 77.27% PCOS women got pregnant ≤2 times in comparison to HC cases (P>0.05).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t002

As depicted in Table 3 , Overall differences of mean in PCOS and HC case comparable in respect of BMI (P<0.125).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t003

However, the highest range of BMI was more in PCOS cases in comparison to HC. Whereas, a statistically, significant differences in mean were observed in respect of age (P<0.009), age at marriage (P<0.001), age of menarche (P<0.001), number of children (P<0.001) and number of pregnancy (P<0.006) between PCOS and HC cases. In case of age, women with PCOS at age ≤19 showed significantly higher score for of general health (P<0.001), role limitation due to physical health (P<0.001), role limitation due to the emotional problem (P<0.022), pain (P<0.025) and social function (P<0.010) in comparison to age >30. However, comparable differences were observed in physical function (P<0.116), energy or fatigue (P<0.087) and emotional well-being (P<0.108). In HC cases, women of age ≤19 showed a statistically higher score in general health (P<0.001), physical health (P<0.001), role limitation due to the emotional problem (P<0.005) and energy/fatigue (P<0.001). Comparable differences were observed for role limitation due to physical health (P<0.818), pain (P<0.424), social functioning (P<0.110) and emotional well-being (P<0.147; Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t004

As per BMI is concerned, PCOS women scored high and statistically significant differences were observed in case of BMI those who have value <18 in comparison to >30. In addition, significant differences were observed for general health score (P<0.001), physical health (P<0.001), energy and emotion (P<0.001). Whereas, comparable differences observed in role limitation due to physical health (P<0.085), role limitation due to the emotional problem (P<0.565), pain (P<0.189), social function (P<0.549) and emotional well-being (P<0.127). In HC case, there no significant difference was observed in all the eight domains of SF-36 ( Table 5 ). As per the level of education is concerned, HRQOL score was higher in all eight domain of SF-36 in well-educated women in comparison to illiterate or women having education of primary level, but this difference was observed to be statistically non-significant and comparable. In case of HC women, HRQOL score in graduation level was higher and significant differences were observed in relation to the level of education for SF-36 domains like general health (P<0.001), physical health (P<0.039) and energy/fatigue (P<0.003). However, we observed comparable differences among all other domains of SF-36 ( Table 6 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t005

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t006

We observed significant differences between married and unmarried PCOS cases in terms of general health (P<0.001), physical functioning (P<0.027), role limitation due to physical health (P<0.006), role limitations due to emotional problems (P<0.002), pain (P<0.001), social functioning (P<0.001), energy/fatigue (P<0.003) and emotional well-being (P<0.001). Whereas, in HC cases, no differences were observed between married and unmarried cases in regarding SF-36 domain score for role limitation due to physical health (P<0.538), role limitation due to the emotional problem (P<0.105), Pain (P<0.044), social functioning (P<0.225), emotional well-being (P<0.857). However, significant differences were observed for general health (P<0.001), physical health (P<0.002) and energy/fatigue (P<0.001) among married and unmarried HC cases ( Table 7 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t007

The Fig 1 and Table 8 exhibits the regression analysis data plot and we was observed strong association between infertility and menstrual irregularities (P<0.049) as well as emotional well being (P<0.001) of PCOS patients. We also observed infertility (P<0.001) and hirsutism (P<0.05) as a major predictor affecting in all domain scores ( Table 9 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t008

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247486.t009

PCOS has no any constant treatment due to its multifaceted features. However, lifestyle modification, hormonal contraceptives and some other drugs like inositol, clomiphene, eflornithine, finasteride, flutamide, letrozole, metformin, spironolactone has been reported to ameliorate the PCOS symptoms [Williams T, Mortada R, Porter S. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. American family physician. 2016; 94(2): 106–113; Lagana AS, Garzon S, Casarin J, Franchi M, Ghezzi F. Inositol in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Restoring Fertility through a Pathophysiology-Based Approach. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(11):768–780; Lagana AS, Garzon S, Unfer V. New clinical targets of d-chiro-inositol: rationale and potential applications. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2020;16(8):703–710].

PCOS is an endocrine disorder and its long term complications affect various aspects of HRQOL in women [ 23 , 24 ]. Despite the various evidence about compromised HRQOL in women with PCOS, we further explored the other determinants that may help the clinician in care of the patient well-being [ 17 , 25 , 26 ]. Overall, we demonstrated the drastically compromised HRQOL in young women suffering from PCOS. As earlier reported, the woman with PCOS belongs to a lesser age group in relation to HC indicating a higher prevalence of PCOS cases in young age woman especially in adolescents [ 27 ]. As per SDS is concerned, the major difference between PCOS and control cases was observed in case of age, BMI and level of education [ 28 ]. Thus, all this indicated that PCOS affects HRQOL more in the young woman and the SDS definitely affect the prevalence of PCOS. The age of menarche in the majority of women was > 18 years as earlier reported [ 29 ]. This was in contrast to other reports [ 30 ]. Consistently, increased age of menarche was observed in PCOS cases indicating the impact of first menstruation in young women life and in the development of PCOS and another reproductive as well as metabolic disorder [ 31 , 32 ].

As previously reported, we observed a direct correlation between the PCOS and irregular or delayed menses and having no children that can be taken as a symptom of PCOS diagnosis [ 33 ]. The higher number of women having lesser than two children and lesser number of times get pregnant further supported this compromised HRQOL [ 30 ]. This compromised HRQOL in PCOS case was further supported by our study.

The overall decreased mean of BMI and age at menarche indicated as PCOS symptoms. Concurrently, mean age, age at marriage, number of children and frequency of pregnancy was less in PCOS cases than control. Consistent to the previous study, these indices corroborate above findings and strongly indicated the deterioration of HRQOL in PCOS women [ 28 ]. Altogether, higher fertility disorder in PCOS cases was observed that directly affects their HRQOL due to physical, social as well as emotional issues.

Furthermore, in PCOS cases, physical, social and emotional well-being more affected as evidenced from all eight domains of SF-36 indicating strongly compromised HRQOL than HC cases [ 34 ]. In particular, we also compare the mean score in relation to age, BMI, educational level and marital status. Consistent with the previous report, increasing the age had a more negative impact on different domains of SF-36 in PCOS cases than HC cases. Comparable scores in PCOS women with increasing age for physical health, energy and emotional well-being may be due to improved regular menses with age concurrent to improved PCOS features and loss of societal fear. Whereas, in HC cases, changes in normal life trend in the prospect of HRQOL was seen with increasing age indicating normal HRQOL [ 35 ].

In a similar fashion, with the increase in the BMI, physical activity was not affected in PCOS cases as observed from different domains of SF-36 but the emotional problem was more affected in PCOS cases in comparison to HC. This may be a major reason for compromised HRQOL in PCOS women [ 36 , 37 ]. In HC cases, none of the scores of SF-36 domains was different between BMI groups. Consistent to previous studies, with increasing the level of education, all the domains of SF-36 in PCOS cases have improved HRQOL. Similar to other HRQOL studies in different diseases, where well-qualified patients have better HRQOL than illiterate cases [ 38 ]. We also observed that well-qualified group probably have higher number of PCOS cases that directly support that improved SDS is a major contributing factor in developing PCOS. The differences in scores of all the domains of SF-36 were observed in married PCOS cases in contrast to unmarried. Thus, consistent to the previous report, the HRQOL of the unmarried cases was better in comparison to married women [ 39 ]. Whereas, in HC cases, all physical, social, as well as emotional wellness, were similar in both married and unmarried women. This may be due to their social independency and quality of education in young women with PCOS.

As reported earlier, infertility and hirsutism emerges as the major problem affecting the overall HRQOL and a strong association has been observed between infertility and emotional well-being [ 40 ].

Our data compares the relations between PCOS and HC cases of overall HRQOL. We explored the strong association between PCOS and SES, and suggest that with increasing age and BMI PCOS patients had lower scores on SF-36; opposite association was with education level. However, Infertility emerges as the major predictor affecting overall HRQOL in PCOS cases. The present study does have its limitations of not measuring biochemical assessment and ultrasonography indices.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dean of Scientific Research, King Khalid University and the College of Pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy for providing facilities to carry out our research work. I also want to acknowledge Dr. R. M. Pandey, Professor & Head, Department of Biostatistics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi (India) for supporting me to analyse and interpret my data.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 3. Centers for disease control and prevention, 2019. Accessed on 06/11/2019. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/spotlights/pcos.html .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Womens Health (Lond)

An update on polycystic ovary syndrome: A review of the current state of knowledge in diagnosis, genetic etiology, and emerging treatment options

1 Biotechnology Program, Department of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, School of Data and Sciences, Brac University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Jaasia Masud

Yushe nazrul islam, fahim kabir monjurul haque.

2 Microbiology Program, Department of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, School of Data and Sciences, Brac University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Polycystic ovary syndrome is the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age, which is still incurable. However, the symptoms can be successfully managed with proper medication and lifestyle interventions. Despite its prevalence, little is known about its etiology. In this review article, the up-to-date diagnostic features and parameters recommended on the grounds of evidence-based data and different guidelines are explored. The ambiguity and insufficiency of data when diagnosing adolescent women have been put under special focus. We look at some of the most recent research done to establish relationships between different gene polymorphisms with polycystic ovary syndrome in various populations along with the underestimated impact of environmental factors like endocrine-disrupting chemicals on the reproductive health of these women. Furthermore, the article concludes with existing treatments options and the scopes for advancement in the near future. Various therapies have been considered as potential treatment through multiple randomized controlled studies, and clinical trials conducted over the years are described in this article. Standard therapies ranging from metformin to newly found alternatives based on vitamin D and gut microbiota could shine some light and guidance toward a permanent cure for this female reproductive health issue in the future.

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a widely prevalent metabolic and endocrine disorder diagnosed in reproductive-aged females. The disease is distinguished by the presence and degree of three major features: irregular menstruation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM). 1 The prevalence of PCOS is known to be around 5%–20%, depending on the varying definitions used. 2 Despite many advances and adaptations in developing the diagnostic criteria and interpreting the condition’s pathophysiology, PCOS remains a less-understood disorder in terms of criteria for uniform diagnosis and treatment. 3 The multifaceted effects of the disease are spread across a woman’s lifetime beginning from conception and extending across the years following menopause. 4 A majority of the studies related to PCOS were performed to develop a timely and efficient diagnosis, particularly for adolescents, effective treatment, and management of comorbidities associated with PCOS that gravely impact the quality of life, and a homogeneous protocol that can be implemented by healthcare officials. 5 In this review, the diagnostic procedures and other screening protocols mentioned were centered around the most recent international evidence-based guidelines for PCOS. Furthermore, the article went into detail about the diagnosis of PCOS in adults together with the challenges faced in diagnosing adolescent girls. We have found a lack of age-specific guidelines that is a consequence of insufficient scientific investigations. In addition, the causal links, both genetic and environmental, have been summarized with a brief insight into the pathogenesis of PCOS. Finally, the current state of the treatment is looked at, and the new options with considerable potential have been discussed.

The incentive to work with PCOS came from the understanding that a certain percentage of women are still being misdiagnosed or left undiagnosed due to unawareness and misunderstanding. While working on this article, it was made clear that many countries, especially Bangladesh, are yet to take PCOS seriously. This was demonstrated through the lack of research in these geographical regions. Thus, we believe that putting forth the actual situation about the condition would help narrow the chasm in recognition and pave the way for better answers.

Diagnosis of PCOS

Introduction to different diagnostic criteria.

PCOS is a recurrent endocrinopathy prevalent in approximately 8%–13% (varying across different populations) of women in the reproductive age bracket. 6 – 9 Despite its frequency, guidance regarding implementing the diagnostic procedures for detecting PCOS is relatively obscure and inconsistent among health professionals. As a result, up to 70% of these women are known to remain undiagnosed. 8 It further adds to the problem of unestablished etiology or origin of PCOS. However, over the past decades, the characteristic traits observed in women with PCOS have been analyzed, and eventually resulted in the development of three diagnostic criteria based on the hallmarks of PCOS.

The three distinctive features of this endocrinologic condition include ovulatory dysfunction, hyperandrogenism, and PCOM in accordance with the consensus-based international guidelines. 10 – 12 In addition, PCOS usually manifests in the form of hirsutism, oligo-anovulation, amenorrhea or irregular menstrual cycle, and infertility. 13 Because of the heterogenic characteristics, three classifications of diagnostic criteria were established over time. The criteria are listed as follows:

- 1. National Institute of Health (NIH) criteria . It was established in 1990 based on the agreement of a veteran panel and the first kind of diagnostic criteria to be ever generated. The NIH criteria authorized two definite features to be representative of PCOS: (a) signs of hyperandrogenism (clinical or biochemical) and (b) oligo-anovulation or oligomenorrhea. 10 This criterion was later revised in 2012, where the third determinant, PCOM, was integrated to conform to the Rotterdam criteria. 14

- • Phenotype A—Hyperandrogenism + Ovulatory Dysfunction + PCOM

- • Phenotype B—Hyperandrogenism + Ovulatory Dysfunction

- • Phenotype C—Hyperandrogenism + PCOM

- • Phenotype D—Ovulatory Dysfunction + PCOM

The Rotterdam criteria are widely used by gynecologists, obstetricians, and other healthcare personnel; it was also adopted by the 2018 International PCOS guideline and other guidelines. 15 , 16 Furthermore, the criteria were also suggested by the NIH evidence-based methodology PCOS workshop held in 2012, alongside phenotype identification in all researches. 14

- 3. AE-PCOS Criteria . It was put forward in 2006 by the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. The third criteria suggested the presence of hyperandrogenism along with any one or two of the remaining determinants (ovulatory dysfunction and/or PCOM) for PCOS diagnosis. 6

In short, the three diagnostic criteria present the identification and quantification of the classical features of PCOS (hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and PCOM) for a definitive diagnosis of the condition. However, it is worth noting that diagnosis through any one of the above-mentioned three criteria will only be conclusive of the condition provided that other endocrine disorders such as hyperprolactinemia, thyroid disease, Non-classical Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (NCAH), Cushing’s syndrome/disease, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or androgen producing tumors which exhibit similar manifestations (clinical/biochemical/morphological) as that of PCOS are ruled out. 14 , 15 For instance, NCAH that manifests in hirsutism or irregular menstruation can be tested by measuring 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17 OHP) levels with an additional ACTH stimulation test in borderline cases. 17 Similarly, hyperprolactinemia can be detected if a prolactin level exceeding the threshold of 500 μg/L is found, exhibiting galactorrhea symptoms and irregular periods. 18 In addition, thyroid diseases can be ruled out by calculating the levels of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). 14 On the other hand, Cushing’s syndrome is a relatively severe condition that displays obesity, high blood pressure, and amenorrhea features. In addition, it is associated with over secretion of cortisol. Thus, an overnight dexamethasone suppression test or midnight salivary cortisol test will assist in distinguishing this condition from PCOS. 19

Diagnostic features in adults

Data from a recent meta-analysis and systematic review revealed a clear picture of the overall prevalence of PCOS based on the three available diagnostic features where ovulatory dysfunction, hirsutism, biochemical hyperandrogenism, and PCOM were found to be in 12%, 13%, 11%, and 28% of women, respectively. 9 The major diagnostic features observed in women with PCOS in a spectrum of degrees are discussed in the succeeding parts of the article.

Ovulatory dysfunction

A staggering proportion of approximately 75% of PCOS individuals is known to have ovulatory dysfunction. 20 It is described as a state of irregular menstrual cycle. 14 In a standard ovulation cycle, menstruation begins by the 24th/25th day. 21 In an adult, irregular menstruation may be indicated by a cycle consisting of <21 or >35 days, or less than eight menstrual cycles per year in a few cases where the gynecologic age is relatively higher. 16 , 22 Continued irregular menstruation indicates anovulation or oligo-anovulation, which can later aggravate a PCOS condition. 14

Contrastingly, regular menstruation reflecting normal ovulatory cycles has also been noticed in women with PCOS. 23 The phenomenon is known as subclinical ovulatory dysfunction and may be explained by hyperandrogenism. This poses a challenge in the diagnosis of PCOS. 24 On the other hand, serum progesterone level above 5 ng/mL (during days 21–24 of the cycle or the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle) may function as a confirmatory test for ovulation in women with PCOM or hirsutism. 25

Hyperandrogenism

Excessive serum androgen level is another salient feature of PCOS, as stated by the Rotterdam criteria. A significant proportion (about 60%–100%) of PCOS-afflicted women are likely to be suffering from hyperandrogenism (clinical and/or biochemical). 15 Hyperandrogenism in PCOS women may be assessed by their clinical signs or biochemical tests.

Clinical hyperandrogenism

Clinical hyperandrogenism observed in the form of hirsutism, acne, or alopecia usually represents low-to-average levels of androgen excess: 26

- Hirsutism appears more frequently than the remaining two in about 80% of people with hyperandrogenism. It refers to the visually detectable growth of terminal hair (hair that can grow beyond 5 mm, if untroubled). 25 The extent of hirsutism is evaluated via the modified Ferriman–Gallwey (mFG) score. 27 This involves visual evaluation of the body’s nine areas (chin, chest, upper lips, upper arms, thighs, upper and lower abdomen, and back) with a score ranging from 0 to 4. 28 , 29 The scores are then presented in the form of a graphical image. The state of hirsutism is conclusive if the total mFG score is ranged within ⩾4–6; this range was extended to a score of eight to adjust for variation in ethnicities. 30 , 31

- Comedonal acne is a widespread issue among women, especially adolescent girls. It was estimated that around 40% of the acne incidence could be traced back to a susceptible PCOS condition. 32 Although acne can be linked with biochemical hyperandrogenism, there is no specialized measuring tool to assess this condition as of now. 26

- Alopecia is the least common feature among the three. Only 22% of women displaying male-like hair loss were discovered during PCOS diagnosis. 32 Many factors other than hyperandrogenemia may be associated with alopecia. The Ludwig scale is a measurement tool for hair loss around the scalp that rates the degree of hair loss from grades I to III upon visual assessment. 1

The subjective variability, racial/ethnic differences, and the existence of a condition named idiopathic hirsutism (hirsutism devoid of hyperandrogenism) play a significant role in determining the clinical signs of PCOS diagnosis and thus require more well-defined data. 33

Biochemical hyperandrogenism

When the clinical signs of hyperandrogenism are obscure, women are assessed for signs of biochemical hyperandrogenism. 12 This diagnostic criterion relies on one of the characteristic traits of PCOS involving elevated serum androgen levels. About 60%–80% of women with PCOS are known to exhibit features of biochemical hyperandrogenism. 6 According to the evidence-based recommendation, the condition can be detected through measurement of total testosterone (TT), free androgen index (FAI), calculated free testosterone (fT), and/or calculated bioavailable testosterone. 12 Previous data suggest that serum-free testosterone is the most sensitive parameter for detecting biochemical hyperandrogenism compared to the other parameters such as total testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), or androstenedione (A4). The latter two have been observed to be elevated in women with PCOS and are particularly useful when a high testosterone level is not detected. Furthermore, DHEAS and A4 facilitate the exclusion of other hyperandrogenic conditions. 15 , 26 Then again, FAI is another indirect means of evaluating the free testosterone level; it is the ratio of the total testosterone and Sex Hormone Binding Globulin (SHBG) multiplied by 100. 34

Total circulating or free testosterone levels can be measured using high-quality assays like extraction/chromatography immunoassays, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) or mass spectrometry. Other automated direct assays include enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA), chemiluminescence assay (CLIA), and radioimmunoassay (RIA). However, these assays exhibit reduced sensitivity and therefore provide imprecise results. 35 – 37 Furthermore, cut-off values vary widely within laboratories and with the method used. Normal thresholds may be derived from a healthy population of women. 12 To conclude, the lack of cut-off values based on evidence, the choice of androgen to test, and the consensus regarding the use of assessment techniques form the major areas of uncertainty in the evaluation of biochemical hyperandrogenism.

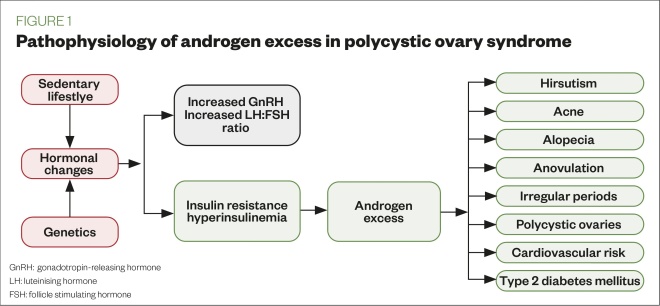

PCOM is recognized as the most widely used feature in the diagnosis of PCOS. It was first introduced in the Rotterdam criteria as the third feature of PCOS in 2003. 11 However, this diagnostic criterion is debatable due to the lack of homogeneity in the results regarding its implementation, and its non-applicability for females above the gynecological age of 8 years. Therefore, it has been deemed a non-essential feature in the presence of the remaining two criteria. 15

The ovulation process is ceased due to follicular arrest in adult women with PCOS. The minute follicles resemble cyst-like structures on transvaginal ultrasonography. 38 – 42 Initially, as authorized in the Rotterdam criteria, the cut-off value for identifying a polycystic morphology was a value of 12 or more Follicle Number Per Ovary (FNPO), measuring between the size of 2–9 mm or, an ovary with a volume of 10 cm 3 on a transvaginal scan. 26 The FNPO value, a key parameter, was later updated in conformity with the technological advancements that enabled more magnified imaging. When using a high-resolution transducer frequency of 8 MHz or more, FNPO value of 20 or more of the same-sized follicles (2–9 mm) and an ovary volume of 10 cm 3 for adult women was recommended by an international evidence-based PCOS guideline consensus held in 2018. 15 The ovarian volume plays a significant role when it is challenging to determine FNPO/Antral Follicle Count (AFC) due to technical complications in imaging, as it is in the case of transabdominal ultrasound. 26

Transvaginal ultrasound is the recommended approach for examining FNPO suggestive of a polycystic ovary. However, it is to be used only in sexually active women. 12 Automatic antral follicle count under 3D scan has shown more accurate results than the 2D grid system method; the information regarding this is still sparse and so is not yet recommended for routine purposes. 43 – 49 Other ultrasound metrics include ovarian stroma and ovarian blood flow; studies concerning these parameters are minimal and hence no cut-off values are available for clinical use. 12

Anti-Mullerian hormone as an alternative diagnostic feature for PCOS

Considering the ambiguity about the efficacy of ultrasound as a diagnostic tool Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) has been suggested as an alternative for detecting PCOM. 15 An upward trend of AMH levels in correlation with the number of antral follicles in PCOS was observed in women with PCOS. It is because AMH is produced by the granulosa cells in ovarian follicles (namely pre-antral and antral), which are elevated in PCOS. 50 – 52 Despite its potential as a valuable diagnostic tool, AMH is still not authorized as a part of routine PCOS diagnosis owing to the inadequate standardization of cut-off values and heterogeneity among the studies 12 , 53 .

Diagnostic challenges in adolescents

Much of the already existing gray areas in PCOS diagnosis for females of all ages can be attributed to its unspecified etiology heterogeneity, the lack of evidence-based cut-off values for the diagnostic features, and the unavailability of clearly defined, universal technology for the most accurate results. 54 Furthermore, a distinct set of diagnostic criteria for adolescents is essential since the existing guidelines mostly comply with features relevant to adults (cystic acne, irregular menstruation, and PCOM). Applying these guidelines for adolescents may lead to over- or under-diagnosis since the manifestation of these features in young girls is also a result of normal pubertal development stemming from an underdeveloped hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. 55 At the outset, the adolescence period has been defined to be the age frame within 10 and 19 years by the World Health Organization. Alternatively, young women within the gynecological age of 8 years were also considered for PCOS studies aimed toward adolescents. 56

A conclusive PCOS condition cannot be diagnosed without the concurrent existence of both menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenism in PCOS. It is also essential to acknowledge a state of “at-risk” category to be followed up by further age-specific diagnosis for PCOS as a means to avoid over or under-diagnosis of young women. 56 , 57

Problems with defining ovulatory dysfunction in adolescence

Diagnosis of PCOS has been recommended to women with persistent irregular menstruation; however, defining irregular menstruation as reflective of ovulatory dysfunction in adolescents is much of a challenge in itself. 58 Definition of irregular menstruation following the gynecological age is tabulated in Figure 1 . 56

Definitions of irregular menstruation according to gynecologic age.

Irregular menstruation is common in young adults after menarche, which is common in the first 2 years, but it can extend as long as 5 years post-menarche. Therefore, the presence of this physiological event cannot be considered a prerequisite for PCOS diagnosis until 2 years succeeding menarche. 58 – 61 However, continued oligomenorrhea even after the 2-year threshold following menarche indicates an “at-risk” status of PCOS in young adults. 55

Determining concurrent anovulation in adolescents is yet another challenge since about 85% of the cycles are known to be anovulatory in the first year following menarche, which shows a downward trend with the number of years post-menarche being 59% and 25% in the second and third year, respectively. 60 In addition, anovulation can be confirmed by serum progesterone level measurement as like in adults. 14 Finally, the variation in age of menarche among females further complicates the assessment and identification of ovulatory dysfunction. 62

Adolescent physiological aspects mimicking hyperandrogenic conditions

As mentioned previously, besides persistent irregular menstruation, androgen excess is a valuable indication of PCOS in adolescents, which may present itself as visible clinical signs (hirsutism, severe acne, and/or rarely alopecia) or elevated serum androgen level.

Acne is a common condition in adolescents and therefore not a definitive diagnostic criterion for PCOS unless accompanied by other features. However, this may indicate hyperandrogenism if the degree of acne ranges from moderate to severe and is not responsive toward topical dermatologic therapy. 58 , 63

Alopecia in adolescents is still not well understood

Although hirsutism has been linked with hyperandrogenism when in association with menstrual irregularity, 64 the presence of various confounding factors such as genetic and ethnic variations deem it to be a less prominent feature in diagnosing a hyperandrogenic status. 29 , 65 , 66 Moreover, the modified Ferriman–Gallwey scoring system may not accurately assess the degree of hirsutism in adolescents since it was structured using data from a population of adult, particularly Caucasian women, which may not apply to women from other ethnicities. 67 – 69

Assessment of biochemical hyperandrogenism has its own set of complications due to lack of standardization, technical difficulties, interference with other steroid hormones, and effect of SHBG on testosterone level, all of which are irrespective of a woman’s age. Despite the physiological impact of puberty leading to a rise in testosterone levels, the same determinants (free and/or total testosterone) are used to gauge androgen excess in adolescents. These methods are limited by the lack of specifically designed studies for adolescents and well-adjusted thresholds.

Controversies regarding PCOM in adolescents

According to the International guidelines on PCOM, transabdominal ultrasound is not recommended for use as a diagnostic criterion until at least 8 years post-menarche, mainly due to the high prevalence of characteristic follicular increase in young adults and an enlarged ovarian volume during this period. 12 , 70 – 73 In addition, the implementation of adult thresholds adjusted for the transvaginal route may lead to over-diagnosis of PCOM in adolescents; hence, PCOM in adolescents is not a reliable diagnosis of PCOS. 74

Risks associated with PCOS

PCOS has been associated with the potential risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), pregnancy-linked complications, gestational diabetes, venous thromboembolism, and endometrial cancer. 1 Many of these metabolic and reproductive conditions stem out from an intrinsic feature of PCOS-insulin resistance (IR). 75 – 77

Cardiometabolic events

Cardiometabolic impacts of PCOS described below are primarily linked with dysglycemia resulting from the insulin-resistant characteristic of PCOS. Insulin resistance or consequential hyperinsulinemia in turn is a state heavily influenced by the hyperandrogenic mechanism of the PCOS pathophysiology. 77 Despite the paucity of comparative studies concerning cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors with and without PCOS, it is noteworthy that the cardiometabolic conditions are prominent in PCOS, which pose a risk of developing CVDs. According to clinical consensus recommendation by the PCOS guideline group (2018), the manifestation of the cardiometabolic risk factors such as impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, obesity, other metabolic syndromes, and a sedentary lifestyle in PCOS women allocates them in the vulnerable category. 15

According to past meta-analyses, the prevalence of IGT and T2D in PCOS-affected women has been observed to be independent of, but made worse with body mass index (BMI). It can be traced back to the correlation of PCOS with dysglycemia, which refers to the aberrant blood glucose level. Thus, estimation of the glycemic status of women with PCOS has been recommended by the International Evidence-based Guideline (2018) at a frequency of 1–3 years depending on the presence of other diabetic confounding factors. In addition to that, screening for T2D has been suggested by all consensus recommendations (Endocrine Society, International Evidence-based Guideline in Australia, as well as Androgen Excess and PCOS society). 61 , 78 However, the screening method is still undecided among Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT), fasting glucose, and HbA1c test. 15

Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia is a recurring CVD risk factor identified in women with PCOS. A significant proportion of women (70%) with PCOS were known to exhibit dyslipidemia in a past report. 79 Furthermore, a meta-analysis of 30 studies demonstrated higher levels of lipids in women with PCOS (age < 45 years), particularly high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), non-HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglyceride (TG). Moreover, TG and HDL-C were substantially higher in the obese stratum indicating a possible link of PCOS with obesity. 80 , 81 Therefore, the latest guidelines suggest women of all ages are diagnosed to undertake a lipid profile. 12

Hypertension

The association between hypertension and PCOS is somewhat complex and influenced by many other factors. The inconsistency between the studies necessitates the requirement for more investigation. 67 , 82 – 84 However, the recent international evidence-based guideline recommends annual blood pressure measurement considering the significance of hypertension in cardiovascular events. 12

Despite its frequency in women with PCOS, there is surprisingly no solid evidence of their causal relationship. However, obesity has been linked to some of the severe PCOS manifestations, including CVD. 85 – 87 Therefore, regular monitoring of body weight has been suggested by the most recent guideline. 12

Other risks

Sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and vitamin D deficiency are emerging risk factors of PCOS, paving the path for further research. 77

The combined effect of a low number of studies and the relatively young population of women restricts the development of a concrete relationship between PCOS and CVD and therefore calling for more research. Nonetheless, the importance of screening for CVDs in PCOS women has been acknowledged. Quantitative research on the clinical manifestations of CVD is insufficient despite researches based on the sub-clinical CVD. 15 , 77

Fertility-related complications in women with PCOS

PCOS comes with lifelong repercussions for women, as stated earlier. Gestational complications associated with PCOS are gradually being recognized, some of which include preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and even miscarriage. 88 It is estimated that much of the pregnancy-related inconveniences are partly ramifications of the already existing metabolic and endocrine effects of PCOS in women well ahead of pregnancy, such as hyperandrogenism and increased BMI. 89 Manifestation of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in expecting women with relatively high weight was observed to be more alarming than their counterparts of lower weight. However, it is worth noting some of these complications are also influenced by other independent factors such as age, obesity, ongoing fertility treatment, and ethnicity. 88 Apart from this, several studies have also reported atypical newborn anthropometrics in children of women with PCOS. 90 – 92

Although screening for GDM and hypertension in women with PCOS (pre-conception and antenatal) has been mentioned in the recommended guidelines, other avenues of pre-conception and antenatal screening for PCOS are still underdeveloped as they are not supported by enough evidence. 15 , 88

Endometrial cancer

Malignancies associated with PCOS are rather indirect and stem from PCOS-induced infertility in women. Of these, endometrial cancer has been acknowledged to have an association with PCOS. 93 Although its occurrence is multifactorial and influenced by other morbidities (T2D, obesity, infertility, and the administered PCOS treatment methods), it has been shown to rise by 2–6 times in women with PCOS. This may be attributed to the anovulatory cycles where the endometrium is exposed to a continuous flux of estrogen. 94 – 96 Despite the correlation between the two, routine screening for endometrial cancer has not yet been recommended. However, awareness on this issue is encouraged. 15

OSA is a chronic sleeping disorder accompanied by disruptive upper airway function and consequential hypoxia and erratic sleeping pattern. 97 It has also been linked with modified heart rate, sympathetic activity, and altered blood pressure, ultimately extending toward more severe outcomes such as CVD and hypertension. 98 – 100 A positive correlation between women with PCOS and OSA was demonstrated through several systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 101 The evaluation of this condition is based on qualitative analysis and a screening tool involving the Berlin Questionnaire. As of present, treatment for OSA only involves the management of distinctive patient symptoms without therapeutic remedy of the linked metabolic diseases. 12

Etiology of PCOS

The current literature emphasizes the role of genetics in PCOS. Many genes have been said to directly or indirectly contribute to the progression of the disease. But to date, no penetrant gene has been identified. 102 Studies conducted in multiple families show low penetrance linked with hormonal/environmental factors or other co-variants. Many studies have suggested that PCOS is a polygenic, multifactorial disorder. Single genes, gene–gene interactions, and gene–environment interactions have been reported to pave the way for the development of the disease. 102 This part of the article will review the current genetic understanding of the disease and some of the environmental determinants explored later in the article.

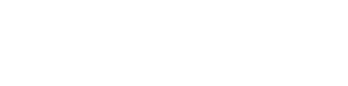

Understanding the roles of these genes better helps to look at some aspects of PCOS pathogenesis, the ovaries, and hormonal metabolism. The ovaries are the primary reproductive organ that releases eggs meant to be fertilized by sperms. They also produce estrogen and progesterone, which help regulate the monthly menstrual cycle, and tiny amounts of the male hormone testosterone, one of the five kinds of androgen. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) are gonadotropin hormones released by the pituitary gland in response to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion by the hypothalamus. These two hormones control ovulation; FSH primarily stimulates the growth of follicles into proper eggs while LH triggers the release of these eggs. Their hormonal interplay in the body is illustrated in Figure 2 . PCOS is a syndrome (or a group of symptoms) that interferes with ovaries and ovulation, in brief. PCOS predominantly has three features: irregular/missed periods, high androgen levels, and cysts, which are fluid-filled sacs in the ovaries. These sacs are essentially immature follicles that never see ovulation. Thus, the lack of ovulation disturbs the hormonal harmony in the body. On top of this, raised androgen levels disrupt the monthly cycles. The underlying justification behind upsetting hormonal balance has been pointed toward genetic alterations, environmental determinants, and epistatic changes.

The hormonal cycle in the female body illustrated with the positive and negative feedback mechanisms. The diagram on the left shows a state prior to ovulation and the right after ovulation.

Biosynthesis of hormones in the ovary in brief

In a secondary follicle, thecal and granulosa cells work in conjunction to produce estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. The process has been outlined in Figure 3 . There are five types of androgens: dihydrotestosterone (DHT), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), DHEA sulfate (DHEAS), androstenedione, and testosterone. LH and FSH secreted by the pituitary gland activate these cells. The thecal cells express LH receptors for LH to bind. Granulosa cells, on the other hand, bind with FSH. When activated by LH, thecal cells increase their absorption of LDLs from the bloodstream. The cholesterol is then used in the synthesis of steroids, like progesterone. Progesterone is then enzymatically converted in a series of steps into androgens. Due to the lack of aromatase enzymes, thecal cells are unable to produce estrogen independently. Thus, the androgens diffuse into the blood and granulosa cells, where it successfully gets converted into estrogen via aromatase. This estrogen later enters the blood. The hypothalamus is stimulated in a positive feedback mechanism; consequently, the characteristic LH surge in the menstrual cycle is seen.

The biosynthesis of androgen and estrogen inside the ovary.

The granulosa cells also have LH receptors but cannot pick up LDLs from the blood; LDLs cannot easily move past the basal membrane. When the follicle ruptures during ovulation, the membrane is destroyed enabling LDL absorption and progesterone production. However, the cells do lack the enzymes needed to convert progesterone into androgens. Thus, the majority of the progesterone diffuses into the blood, which explains the rapid rise in its level post-ovulation. After ovulation, both cells produce progesterone and, to a lesser extent, androgens.

Cholesterol is the precursor of all steroid hormones classified into three categories: glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and gonadocorticoids (or sex hormones). Sex steroids are mainly androgens, estrogens, and progesterone. All steroid hormones are hydrophobic and require a protein carrier when transported in the blood. These are albumin, corticosteroid-binding globulin, and sex hormone–binding globulin. Cholesterol is a 27-carbon compound that undergoes a multi-step process and gets shortened and hydroxylated eventually. The series of conversions is shown briefly in Figure 4 . These enzymes (e.g. cytochrome p450 members) are involved here that are targeted by studies; polymorphisms in their coding region can ultimately affect hormonal metabolism and lead to hyperandrogenism. The idea is that some defect in the hormonal pathway causes the classic characteristics of PCOS; these avenues are probable areas for research. Numerous studies on the relationship between gene polymorphisms and PCOS have been conducted. Some of the significant ones have been discussed later in the review.

Summary of steroidogenesis with the end-products shown.

While ovaries are generally considered the primary source of androgens, the adrenal glands also contribute. Increased adrenal androgens (DHEA and DHEAS) are consistent with 20%–30% of the PCOS population 103 —a phenomenon called adrenal hyperandrogenism .

Hormonal association in PCOS

Hormones play a crucial role in the normal functioning of the ovary and the regulation of menstruation. If hormonal disturbances persist, the ovary’s function is interrupted, leading to the formation of a cyst inside of its sac. 104 PCOS patients exhibit an imbalance in levels of GnRH, FSH, LH, androgen, and prolactin. 105 The progression of PCOS and its severity rises with an increasing level of insulin and testosterone. Hyperinsulinemia is known to affect ovarian theca cells inflating androgen concentration. 106 Then again, elevated androgen levels trigger visceral adipose tissue (VAT), that is, responsible for the production of free fatty acids (FFA), which in turn elicits insulin resistance. 107 Due to insulin resistance and its consequent outcome of elevated insulin levels, androgen levels rise, which leads to anovulation. 7

To support the hormonal association with PCOS, a cross-sectional study in Pakistan examined healthy and affected women. Blood samples were drawn from individuals, and hormonal analysis was performed using immunoradiometric assay and radioimmunoassay. Their findings stated that FSH, LH, prolactin levels, and BMI were higher in PCOS cases. The current diagnosis of PCOS involves looking at FSH, LH, and androgen levels. 108 We know that raised LH levels result in higher androgen levels, which gives rise to PCOS, among other reasons.

The genetic connection

There are several genes involved in the etiology of PCOS. At present, there are three databases manually curated and published: PCOSKB R2 (2020), PCOSBase (2017), and PCOSDB (2016). 109 – 111 PCOSDB had been inaccessible at the time of writing. The three databases are compared in Table 1 .

A brief comparison of the three PCOS databases published so far.

| Attributes | PCOSKB | PCOSBase | PCOSDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Official name | PolyCystic Ovary Syndrome KnowledgeBase | PolyCystic Ovary Syndrome Base | PolyCystic Ovary Syndrome Database |

| 2. Database URL | |||

| 3. Overall content | 533 genes, 145 SNPs, 29 miRNAs, 1150 pathways, and 1237 PCOS-associated diseases Also included are more 4023 genes identified from microarray expression studies on PCOS | 8185 PCOS-related proteins, 7936 domains, 1004 pathways, 1928 PCOS-associated diseases, 29 disease classes, and 91 tissues | 208 genes, 427 molecular alterations including detailed annotations, 46 associated phenotypes |

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism.

As per PCOSKB R2 , 241 genes and 114 SNPs are closely involved in PCOS. 109 Changes like polymorphisms negatively affect the transcriptional activity of the gene, ultimately leading to PCOS. Now, the genes suitable for PCOS study are those that code for receptors of hormones like androgen, LH, FSH, and even, leptin. 112 Genes, namely, AR, CAPN10, FTO, follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR), cytochrome family P450, and insulin genes, have been widely discussed.

This review has discussed some genes commonly involved in ovarian and adrenal steroidogenesis, gonadotropin action and regulation, insulin action and secretion, and a few notables. Table 2 details the research on these groups of genes.

A rundown on the associations of different polymorphisms with PCOS found by most recent studies.

| SL. | Category | Gene | Year | Sample Size and ethnicity/location | Findings/Conclusion | Key methods | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Involved in ovarian and adrenal steroidogenesis | CYP11A | 2014 | 267 cases versus 275 controls “South Indian” | Fifteen different alleles were identified with repeats ranging from 2 to 16. Repeats greater than 8 were thrice more likely to be susceptible to PCOS and have been found comparatively more in the patients. CYP11A1 repeat polymorphism is likely to be a potential molecular marker for PCOS diagnosis. | DNA extracted from blood and genotyped by PCR-PAGE | Reddy et al. | |

| 2 | 2014 | 1236 cases versus 1306 controls “Asian and Caucasian” Argentina, China, Greece, India, Spain, United Kingdom | Positive association between CYP11A1 repeat polymorphism and PCOS. | Meta-analysis of nine studies published between 2000 and 2010 | Yu et al. | |||

| 3 | 2014 | 1571 cases versus 1918 controls “Asian and Caucasian” China, India, Greece, Spain, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States | CYP11A1 microsatellite repeat polymorphism (along with CYP1A1 MspI) showed significant association with PCOS risk in the Caucasian population. | Meta-analysis of 13 studies published between 2000 and 2010 | Shen et al. | |||

| 4 | 2012 | 314 cases versus 314 controls “Chinese” | SNP rs4077582 in CYP11A1 was found to be strongly associated with PCOS susceptibility. No association was observed in rs11632698. | PCR-RFLP | Assessed the association of SNPs rs4077582 and rs11632698 in CYP11A1 with PCOS | Zhang et al. | ||

| 5 | CYP21 | 2013 | 197 patients | The study looked into 14 molecular defects of the CYP21A2 gene and concluded that its contribution to PCOS is unsubstantiated. | Allele-specific PCR | The study investigated the contribution of CYP21A2 heterozygous mutations to PCOS pathogenesis | Settas et al. | |

| 6 | 2010 | 50 cases versus 60 controls “Italian” | The data suggested a lack of association between CYP21 V281L polymorphism and PCOS. | PCR-RFLP | Pucci et al. | |||

| 7 | 2005 | 114 cases versus 95 controls “Non-Hispanic White” | CYP21 mutations were found to play a limited role in the development of PCOS. | Prospective case-control study | Witchel et al. | |||

| 8 | 2000 | n < 50 | CYP21 V281L mutations seemingly manifested PCOS-like phenotype. | Witchel and Aston | ||||

| 9 | CYP17 | 2021 | 394 cases versus 306 controls “Kashmiri” | Mutant genotype is associated with hyperandrogenism. | PCR-RFLP | T/C polymorphism in 5′UTR of CYP17 gene was analyzed to find its connection to hyperandrogenism and PCOS | Ashraf et al. | |

| 10 | 2021 | 204 cases versus 100 controls “Pakistani” | rs743572 polymorphism is significantly associated with PCOS. | PCR-RFLP | 5′UTR region (MspA1) of CYP17 gene was analyzed | Munawar Lone et al. | ||

| 11 | 2019 | 50 cases versus 109 controls “Kurdish” West Iran | Data suggested a positive link of CYP17 T-34C polymorphism with PCOS risk. | PCR-RFLP; chemiluminescent method for hormone measurements | Rahimi and Mohammadi | |||

| 12 | 2018 | 250 cases versus 250 controls North India | Data suggested that − 34T > C polymorphism in CYP17A1 is associated with PCOS in North Indian females. | PCR-RFLP; lipid profile via biochemical analyzer | Kaur et al. | |||

| 13 | 2012 | 287 cases versus 187 controls “Caucasian” | The gene has been suggested as a non-major risk factor. | SNP genotyping and haplotype determination | Four SNPs of CYP17 analyzed | Chua et al. | ||

| 14 | CYP19 | 2020 | 204 cases versus 100 controls “Pakistani” | The polymorphism, rs2414096 (genotype GA) of the CYP 19 gene was considerably associated with PCOS vulnerability. | PCR-RFLP | The study looked at both CYP17 and CYP19 genes | Munawar Lone et al. | |

| 15 | 2019 | 50 cases versus 109 controls “Kurdish” West Iran | No statistical significance was found in the association of CYP19A1 with PCOS risk. | PCR-RFLP; chemiluminescent method for hormone measurements | Rahimi and Mohammadi | |||

| 16 | 2018 | 250 cases versus 250 controls North India | Variations of CYP19A1 were not statistically relevant with PCOS. | Kaur et al. | ||||

| 17 | 2017 | 70 cases versus 70 controls Iran | The study concluded that SNP rs2414096 in CYP19 is likely to play a role in developing PCOS in Iranian women. | PCR-RFLP; enzyme digestion with HSP92II | Mehdizadeh et al. | |||

| 18 | 2014 | 62 cases versus 60 controls | Polymorphism of rs2414096 in CYP19 was found to be associated with the pathogenesis of PCOS. | PCR-RFLP; statistical analysis by SPSS | Hemimi et al. | |||

| 19 | Involved in steroid hormone effects | AR | 2013 | 114 cases versus 1409 controls Diverse ethnicities | CAG variants in the AR gene were unassociated with PCOS risk while they may be related to the T levels in PCOS. | Meta-analysis of 11 studies published between 2000 and 2012 | Zhang et al. | |

| 20 | SHBG | 2020 | 1660 cases versus 1312 controls | rs6259 and rs727428 polymorphisms in SHBG are not associated with PCOS susceptibility. | Meta-analysis of seven studies published between 2007 and 2019 | Liao and Cao | ||

| 21 | Involved in insulin secretion and action | CAPN10 | 2017 | 169 cases versus 169 controls South India | No association of rs2975766 and rs7607759 with PCOS. | RT-PCR | The study looked at other gene polymorphisms too | Thangavelu et al. |

| 22 | 2014 | 127 cases versus 150 controls Tunisia | UCSNP-43 (rs3792267), UCSNP-19 (rs3842570), and UCSNP-63 (rs5030952) were investigated along with their haplotypes. No significant association, except one with obese PCOS subjects, was found. | PCR-RFLP | Ben Salem et al. | |||

| 23 | 2014 | 668 cases versus 200 controls “Caucasian Greek” | There was no correlation of CAPN 10 polymorphism (UCSNP-43) with the incidence of PCOS. Additionally, the gene polymorphism could not be associated with any biochemical, clinical, hormonal, or ovarian features of PCOS. | Primer extension; MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry | Anastasia et al. | |||

| 24 | 2013 | 2123 cases versus 3612 controls | Nine common SNPs were examined. UCSNP 19/63/44 is likely to be associated with increased PCOS risk among Asians. No statistically significant association with UCSNP-22, UCSNP-43, UCSNP-45, UCSNP-56, UCSNP-58, and UCSNP-110 polymorphisms. | Meta-analysis of 14 studies published between 2002 and 2013 | The review is comprehensive and helpful | Shen et al. | ||

| 25 | 2009 | 88 cases “Brazilian” | Data provide evidence that UCSNP-43 may play a role in PCOS while UCSNP-19 and UCSNP-63 remained unassociated with phenotypic traits in PCOS. | Wiltgen et al. | ||||

| 26 | 2008 | 50 cases versus 70 controls “Chilean” | Data suggests a contribution of UCSNP-43 polymorphism to PCOS in Chilean women. | PCR-RFLP | The study looked at UCSNP-19 and UCSNP-63 as well | Márquezet al. | ||

| 27 | IRS | 2016 | 2975 cases versus 3011 controls “Asian and Caucasian” | The findings suggested that IRS-1 Gly972Arg polymorphism be associated with PCOS in the Caucasian ethnicity, and IRS-2 Gly1057Asp polymorphism correlated with PCOS in the Asians. | A meta-analysis of 28 studies published between 2001 and 2014 | Shi et al. | ||

| 28 | 2013 | 150 cases versus 175 controls Croatia | Data did not support an association between Gly792Arg IRS-1 (along with VNTR INS, C/T INSR) polymorphisms and PCOS. Nor did it find any correlation with insulin resistance in Croatian women with PCOS. | Skrgatić et al. | ||||

| 29 | INSR | 2016 | 2975 cases versus 3011 controls “Asian and Caucasian” | The INSR polymorphism, His 1058 C/T, was not found to be associated with PCOS development. | A meta-analysis of 28 studies published between 2001 and 2014 | Shi et al. | ||

| 30 | 2015 | 17,460 cases versus 23,845 controls | The meta-analytical data suggested no significant correlation between rs1799817/rs2059806 SNPs and PCOS susceptibility. On the other hand, it was concluded that rs2059807 could be a promising SNP involved in PCOS susceptibility. | A meta-analysis of 12 studies published between 1994 and 2013 | Feng et al. | |||

| 31 | Involved in gonadotropin action and regulation | AMH | 2020 | 383 cases versus 433 controls “Chinese” | Fifteen rare, but known AMH variants were identified, along with seven novel heterozygous variants. Researchers conclude that AMH can play a role in PCOS development. | Sanger sequencing | Qin et al. | |

| 32 | 2019 | 608 case versus 142 controls | The AMH signaling cascade was deduced as a key player in PCOS etiology. Variants have been identified. | Targeted sequencing | Regions of AMH and AMHR2 were looked at | Gorsic et al. | ||

| 33 | 2017 | 643 case versus 153 controls | Rare genetic variants of AMH related to PCOS were identified. | Targeted sequencing | Replication of whole-genome sequencing | Gorsic et al. | ||

| 34 | 2017 | 2042 cases versus 1071 controls | Meta-analytical data showed no association of AMH (or AMHR2) with a heightened risk of PCOS. | A meta-analysis of five studies published between 2002 and 2013 | Wang et al. | |||

| 35 | FSHR | 2021 | 130 cases Iran | FSHR polymorphisms Ala307Thr and Asn680Ser were concluded to be statistically associated with PCOS women. | PCR followed by sequencing | Seyed Abutorabi et al. | ||

| 36 | 2020 | 1882 cases versus 708 controls “Chinese” | rs2300441 was found to be a primary contributor. | – | GWAS | Yan et al. | ||

| 37 | 2018 | 93 cases versus 52 controls “Kurdish” Northern Iraq | Significant differences were found in FSH and LH levels in PCOS patients with different genotypes of Ala307Thr polymorphism. No relationship was established between polymorphism and PCOS. | PCR-RFLP; Eam1105I enzymatic digestion | Baban et al. | |||

| 38 | 2017 | 377 women versus 388 controls “Korean” | Findings suggested a significant association between FSHR gene polymorphisms (Thr307Ala or Asn680Ser) and PCOS. | RT-PCR | Kim et al. | |||

| 39 | 2014 | 1760 cases versus 4521 controls “Asian and Caucasian” China, Italy, Korea, Netherlands, Turkey, United Kingdom | Results showed no association between Thr307Ala and Asn680Ser polymorphisms of FSHR with PCOS susceptibility. | A meta-analysis of 10 studies published between 1999 and 2013 | Chen et al. | |||

| 40 | 2014 | 215 cases versus 205 controls “Han Chinese” North China | The Ala307Thr and Ser680Asn polymorphisms of FSHR are not related to PCOS in Han ethnic Chinese women. | PCR-RFLP; direct sequencing | Another study in North China with slightly more PCOS cases has found similar results | Wu et al. | ||

| 41 | LHCGR | 2015 | 203 cases versus 211 controls “Bahraini Arab” | The first study suggested an association of LHCGR polymorphisms (rs7371084 and rs4953616) with PCOS. The study also added a strong association of FSHR (rs11692782). | RT-PCR | Almawi et al. | ||

| 42 | Other genes | FTO | 2019 | 55 cases versus 110 controls “Srilankan” | FTO gene rs9939609 polymorphism was significantly more common among PCOS subjects. | Allele-specific real-time quantitative PCR (AS-qPCR) | Branavan et al. |

PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; GWAS: genome-wide association studies; PAGE: polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; RFLP: restriction fragment length polymorphism; RT: reverse transcription.

Red text means a negative association or no association, the orange text implies a weak link to PCOS, and the green text indicates a strong correlation with PCOS.