Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Pathophysiology — A Comprehensive Exploration of Asthma

A Comprehensive Exploration of Asthma

- Categories: Pathophysiology

About this sample

Words: 1260 |

Published: Feb 13, 2024

Words: 1260 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Table of contents

Acute asthma, chronic asthma, impact of gender on pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Asthma. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm

- Dodge, R., R., & Burrows, B. (2018). The prevalence and incidence of asthma-like symptoms in a general population sample. Am Rev Respir Dis 2018; 122:567–75.

- Holgate, S., T. (2017). Genetic and environmental interaction in allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 104: 1139–46

- Lemanske, R., F., & Busse., W., W. (2017). Asthma: Clinical expression and molecular mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017, 125: S95-102. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.047.

- Mandhane, P., J., Greene, J., M., Cowan, J., O., et al. (2015). Sex differences in factors associated with childhood and adolescent-onset wheeze. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 172:45–54

- Thomas, A., O., Lemanske, R.., F., & Jackson, D., J. (2014). Infections and their role in childhood asthma inception. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014; 25: 122–128

- Wright, A., L., Stern, D., A., Kauffmann, F., et al. (2016). Factors influencing gender differences in the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: the Tucson Children' s Respiratory Study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016; 41:318–25.

- Wright, A., L., Stern, D., A., Kauffmann, F., et al. (2016). Factors influencing gender differences in the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: the Tucson Children's Respiratory Study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016; 41:318–25.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

10 pages / 4461 words

3 pages / 1416 words

1 pages / 620 words

3 pages / 1427 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Pathophysiology

The article called “Frontiers in the Bioarchaeology of Stress and Disease: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives From Pathophysiology, Human Biology, and Epidemiology” by Haagen D. Klaus (2014) reviews a few different aspects of a [...]

Syncope and Vertigo are often used as interchangeable terms. This is inaccurate, despite both being forms of dizziness. The term ‘Dizziness’ is given when a patient experiences changes of consciousness, movement, sensation and [...]

The gestational diabetes mellitus ,likewise perceive as GDM is a customary intricacy of certain pregnancies, when hyperglycemia appears throughout the being pregnant . In light of the latest (from 2017) [...]

The scenario presents a 4-month pregnant female with Phenylketonuria (PKU). Due the teratogenic effects that phenylalanine has on a foetus, her GP has advised her to go on a low-protein diet. The distress that this caused to [...]

We are connected to our surroundings by five senses: Sight, smell, taste, touch and hearing. Hearing is more than sounds, it is a biopsychosocial process. There are sounds, with specific features, that can damage our hearing [...]

The ileum is the longest segment of the small intestine and it contains a circular smooth muscular layer. The smooth muscle contains muscarinic acetylcholine receptors which should respond to the presence of acetylcholine (ACh) [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Asthma: pathophysiology, causes and diagnosis

Despite asthma affecting more than 5.4 million people in the UK, there is no gold standard test and diagnosis is based on signs and symptoms.

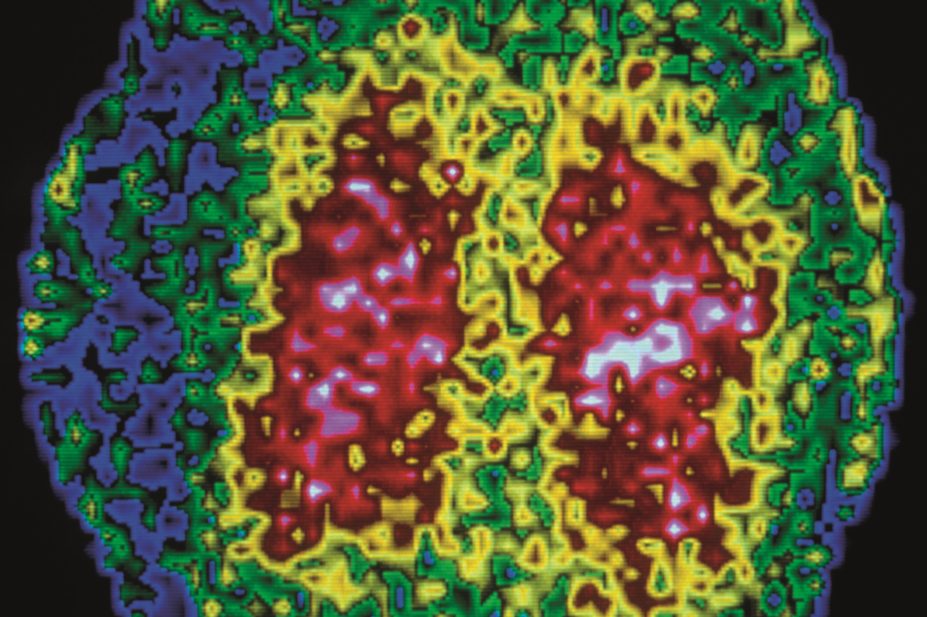

Centre Jean Perrin / Science Photo Library

There is no single cause for asthma, and a range of environmental and genetic factors are known to influence its development. These include premature birth and low birth weight and exposure to tobacco smoke (especially if the mother smokes in pregnancy). It is more common in prepubertal boys, but girls are more likely to remain asthmatic in adolescence.

A diagnosis of asthma in both children and adults is based on assessment of symptoms. The classic signs of asthma are wheezing (especially expiratory wheezing), breathlessness, coughing (typically in the early morning or at night time) and chest tightness. Children and adults with a high probability of asthma on assessment usually start a treatment trial with a corticosteroid such as beclometasone. Children and adults with an intermediate probability of asthma are assessed with lung function tests such as spirometry, peak flow and airway responsiveness to confirm the diagnosis.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways. Chronic inflammation causes an increase in airway hyperresponsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction that is often reversible, either spontaneously or with treatment [1] .

It is estimated that more than 5.4 million people in the UK are currently diagnosed with asthma, of whom 1.1 million are children. In the UK, asthma causes 1,200 deaths each year, or one death from asthma every eight hours. This number has remained stable over the past few years despite raised awareness [2] , [3] .

Pathophysiology

Asthma is usually mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) and precipitated by an allergic response to an allergen. IgE is formed in response to exposure to allergens such as pollen or animal dander [4] . Sensitisation occurs at first exposure, which produces allergen-specific IgE antibodies that attach to the surface of mast cells. Upon subsequent exposure, the allergen binds to the allergen-specific IgE antibodies present on the surface of mast cells, causing the release of inflammatory mediators such as leukotrienes, histamine and prostaglandins. These inflammatory mediators cause bronchospasm, triggering an asthma attack.

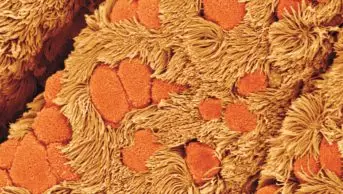

If an attack is left untreated, eosinophils, T-helper cells and mast cells migrate into the airways [1] . Excess mucus production caused by goblet cells plug the airway and, together with increased airway tone and airway hyperresponsiveness, this causes the airway to narrow and further exacerbates symptoms.

There is some evidence to suggest that airway remodelling can occur if asthma is poorly controlled over a period of years. Chronic inflammation causes bronchial smooth muscle hypertrophy, the formation of new vessels and interstitial collagen deposition, which results in persistent airflow obstruction similar to that seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [5] .

Although there is no single cause of asthma, certain environmental and genetic factors are known to contribute to the development of the condition. These include:

- Family history of asthma (especially a parent or sibling) or other atopic conditions (for example, eczema or hayfever)

- Bronchiolitis in childhood — 40% of children exposed to respiratory syncytial virus or parainfluenza virus will continue to wheeze or have asthma into later childhood [1]

- Exposure to tobacco smoke, particularly if the mother smokes during pregnancy

- Premature birth

- Low birth weight

- Occupational exposure to plastics, agricultural substances and volatile chemicals, such as solvents. Asthma is more prevalent in industrialised countries

- A body mass index of 30kg/m 2 or more

- Bottle feeding — evidence shows that if an infant is breastfed there is a decreased risk of wheezing illness compared with infants who are fed formula or soya-based milk feeds [3]

Environmental and cultural factors in recent decades, such as changes in housing, air pollution levels and a more hygienic lifestyle (reducing early exposure to allergens), may also increase the risk of asthma.

Asthma is more common in prepubertal boys, but boys are more likely to grow out of their asthma during adolescence than girls [1] .

Phenotyping is becoming increasingly important for clinicians in determining why some people are predisposed to develop asthma and others are not. Furthermore, it is believed that a person’s phenotype may also contribute to the way he or she responds to treatment [6] . For example, variations in the gene that codes for beta-adrenoceptors have been linked to differences in how cells respond to beta-agonists. In the future, as more information emerges, it may be possible to tailor treatments for individual patients to enhance response — which is particularly important as more high-cost, highly specific medicines are being developed [3] , [6] .

Clinical features

There are many factors likely to trigger an asthma attack, and potential causes will vary between patients. Possible triggers include: the common cold; allergens (e.g. house dust mites, pollen); exercise; exposure to hot or cold air; medicines (e.g. NSAIDs); and emotions such as anger, anxiety or sadness.

The classic signs of asthma are wheezing (especially expiratory wheezing), breathlessness, coughing (typically in the early morning or at night time) and chest tightness. Wheezing that occurs as a result of airway bronchoconstriction and coughing are likely to be caused by stimulation of sensory nerves in the airways.

In a severe exacerbation, when there is severe obstruction of the airway, wheeze may be absent and the chest may be silent on auscultation (listening to the chest). In such cases, other signs such as cyanosis and drowsiness may be present, and the patient may be unable to complete full sentences. Severe exacerbations of asthma are medical emergencies.

Diagnosis of asthma is based on medical history, physical examination, lung function testing and response to medication (see ‘Diagnosis of asthma’). There is no gold standard test that can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnosis of asthma [1]

Clinical features that increase the probability of asthma

- More than one of the following symptoms: wheeze, cough, difficulty breathing, chest tightness, particularly if these are frequent and recurrent; are worse at night and in the early morning; occur in response to, or are worse after, exercise or other triggers; occur apart from colds; are associated with taking aspirin or beta-blockers in adults

- Personal history of atopic disorder

- Family history of atopic disorder and/or asthma

- Widespread wheeze heard on auscultation

- History of improvement in symptoms or lung function in response to adequate therapy (in children)

- Otherwise unexplained peripheral blood eosinophilia, or low forced expiratory volume in one second or peak expiratory flow (in adults)

Clinical features that lower the probability of asthma

- Symptoms with colds only

- Isolated cough with no wheeze or difficulty breathing, or history of moist cough (in children)

- Chronic productive cough with no wheeze or difficulty breathing (in adults)

- Prominent dizziness, light-headedness, peripheral tingling

- Repeatedly normal physical examination of chest when symptomatic

- Normal peak expiratory flow or spirometry when symptomatic

- Cardiac disease (in adults)

- Voice disturbance (in adults)

- History of smoking for more than 20 pack-years (in adults)

Children and adults with a high probability of asthma on assessment usually start a treatment trial, where their response is assessed using spirometry. Children and adults with an intermediate probability of asthma usually have lung function tests conducted, such as spirometry, peak flow and airway responsiveness.

Spirometry can be used to measure lung function and is a good guide to diagnosing asthma in adults. It is not always definitive; normal findings do not exclude a diagnosis of asthma if the patient is well at the time of testing. The spirometric measures used in the diagnosis of asthma are:

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) — the total volume of air expelled by a forced exhalation after a maximal inhalation

- Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ) — the volume of air expelled in the first second of a forced exhalation after maximal inhalation

- FEV 1 /FVC ratio

An FEV 1 /FVC ratio below 0.7 is suggestive of airway obstruction, which can increase the probability of asthma, but it can also be caused by conditions such as COPD.

Peak expiratory flow using a peak flow meter measures the resistance of the airway. Although it is not as accurate as spirometry, it can be used to demonstrate variability of lung function throughout the day. Measurements should be taken in the morning and evening (as a minimum) and recorded in a diary to see if there is diurnal variability. Readings are dependent on technique and expiratory effort, therefore the best of three expiratory blows from total lung capacity should be recorded during each session. Peak flow diaries are better for monitoring patients with an established diagnosis of asthma rather than for making an initial diagnosis [1] , [3] .

Assessment of airway responsiveness using inhaled mannitol or methacholine is used for diagnosing patients with normal or near normal spirometry who have a baseline FEV 1 of less than 70% of that predicted using population data. Both drugs induce bronchospasm [1] , [3] . A fall in FEV 1 of more than 15% following a test with mannitol is a specific indicator for asthma. This assessment is useful for distinguishing asthma from other common conditions that can be confused with asthma (for example, rhinitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux, heart failure and vocal cord dysfunction).

A treatment trial in adults involves a patient being prescribed a six-to-eight week trial of inhaled beclometasone 200µg (or equivalent) twice a day, or two weeks of oral prednisolone 30mg daily. An improvement in FEV 1 of 400ml or more following the trial is strongly suggestive of an underlying diagnosis of asthma. Spirometric assessment after a treatment trial is more effective for patients with known airflow obstruction, and is less helpful for patients who had near normal lung function before the trial.

Non-invasive testing of sputum eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide concentration can also help guide a diagnosis of asthma. A raised sputum eosinophil count (>2%) is seen in around 70–80% of patients with uncontrolled asthma. However, patients with COPD or chronic cough may also exhibit abnormal levels of eosinophils and the test should not be used for definite diagnosis [7] . Sputum eosinophils and exhaled nitric oxide concentration are not routinely measured in general practice, but are in designated difficult asthma clinics [3] . An exhaled nitric oxide level of more than 25 parts per billion supports a diagnosis of asthma.

Assessing asthma control

Many people with asthma do not have their condition well controlled. A survey of 8,000 people with asthma in Europe between July 2012 and October 2012 found that despite 91% of patients considering themselves as having well controlled asthma, only 20% of cases were controlled according to standards set out by national and international guidance [8] .

The aim of asthma management is to achieve and maintain complete control of the disease. This is defined as having:

- No daytime symptoms or night time awakening due to asthma

- No need for rescue medication

- No exacerbations

- No limitations on activity including exercise

- Normal lung function

- Minimal side effects from medication

It is important that control of asthma is measured objectively. One effective way to assess the level of control is the Asthma control test questionnaire (available from asthma.com ). This validated five-point questionnaire is a simple and easy way for patients to self assess their asthma control and guide healthcare professionals to develop a treatment plan in accordance with the results obtained [1] .

[1] British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma. Clinical Guideline 141. London: BTS. October 2014.

[2] Royal College of Physicians (London). Why asthma still kills. London: RCP. May 2014.

[3] Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Geneva: GINA. 2014.

[4] Barnes P. Similarities and differences in inflammatory mechanisms of asthma and COPD. Breathe 2011;7:229–238.

[5] Dournes G & Laurent F. Airway remodelling in asthma and COPD: findings, similarities and differences using quantitative CT. Pulmonary Medicine 2012.

[6] Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat Med 2012;18:716–725.

[7] Green RH, Brightling CE, McKenna S, et al. Asthma exacerbations and sputum eosinophilia counts: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2002;360:1715–1721.

[8] Price D, van der Molen T, Fletcher M. Exacerbations and symptoms remain common in patients with asthma control: a survey of 8000 patients in Europe. Abstract presented at the European Respiratory Society conference 2013.

You might also be interested in…

Helping respiratory patients breathe easy

Asthma therapies get personal

Asthma: long-term management

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Diet and asthma: a narrative review.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

2. asthma phenotypes and endotypes, 3. airway inflammation, 4. diet and asthma, 4.1. fruits and vegetables, 4.4. fats and fish, 4.6. dairy products, 4.7. dietary patterns, 5. discussion, 6. limitations and strengths, 7. conclusions, 8. future directions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Dharmage, S.C.; Perret, J.L.; Custovic, A. Epidemiology of Asthma in Children and Adults. Front. Pediatr. 2019 , 7 , 246. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2022. Available online: www.ginasthma.org (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Guilleminault, L.; Williams, E.J.; Scott, H.A.; Berthon, B.S.; Jensen, M.; Wood, L.G. Diet and Asthma: Is It Time to Adapt Our Message? Nutrients 2017 , 9 , 1227. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Andrianasolo, R.M.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Adjibade, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Varraso, R. Associations between dietary scores with asthma symptoms and asthma control in adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2018 , 52 , 1702572. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Peters, U.; Dixon, A.E.; Forno, E. Obesity and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018 , 141 , 1169–1179. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Badellino, H.A. Diagnosis of allergy and asthma in childhood. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011 , 11 , 71–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Agache, I.; Akdis, C.A. Global Atlas of Asthma ; European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI): Zurich, Switzerland, 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ntontsi, P.; Photiades, A.; Zervas, E.; Xanthou, G.; Samitas, K. Genetics and Epigenetics in Asthma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021 , 22 , 2412. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019 , 56 , 219–233. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Skloot, G.S. Asthma phenotypes and endotypes: A personalized approach to treatment. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2016 , 22 , 3–9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Agache, I.; Eguiluz-Gracia, I.; Cojanu, C.; Laculiceanu, A.; del Giacco, S.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Kosowska, A.; Akdis, C.A.; Jutel, M. Advances and highlights in asthma in 2021. Allergy 2021 , 76 , 3390–3407. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fahy, J.V. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—Present in most, absent in many. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015 , 15 , 57–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Papi, A.; Brightling, C.; Pedersen, S.E.; Reddel, H.K. Asthma. Lancet 2018 , 391 , 783–800. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sansone, F.; Attanasi, M.; Di Pillo, S.; Chiarelli, F. Asthma and Obesity in Children. Biomedicines 2020 , 8 , 231. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mims, J.W. Asthma: Definitions and pathophysiology. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015 , 5 (Suppl. 1), S2–S6. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Liu, P.C.; Kieckhefer, G.M.; Gau, B.S. A systematic review of the association between obesity and asthma in children. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013 , 69 , 1446–1465. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Rastogi, D.; Holguin, F. Metabolic Dysregulation, Systemic Inflammation, and Pediatric Obesity-related Asthma. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017 , 14 (Suppl. 5), S363–S367. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chen, Z.; Salam, M.T.; Alderete, T.L.; Habre, R.; Bastain, T.M.; Berhane, K.; Gilliland, F.D. Effects of Childhood Asthma on the Development of Obesity among School-aged Children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017 , 195 , 1181–1188. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Papoutsakis, C.; Priftis, K.N.; Drakouli, M.; Prifti, S.; Konstantaki, E.; Chondronikola, M.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Matziou, V. Childhood overweight/obesity and asthma: Is there a link? A systematic review of recent epidemiologic evidence. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2013 , 113 , 77–105. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shan, L.S.; Zhou, Q.L.; Shang, Y.X. Bidirectional Association Between Asthma and Obesity during Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2020 , 8 , 576858. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bhatt, N.A.; Lazarus, A. Obesity-related asthma in adults. Postgrad. Med. 2016 , 128 , 563–566. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Eder, W.; Ege, M.J.; von Mutius, E. The asthma epidemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006 , 355 , 2226–2235. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Li, X.; Cao, X.; Guo, M.; Xie, M.; Liu, X. Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ 2020 , 368 , m234. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Zhang, D.; Zheng, J. The Burden of Childhood Asthma by Age Group, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis of Global Burden of Disease 2019 Data. Front. Pediatr. 2022 , 10 , 823399. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Barros, R.; Moreira, P.; Padrão, P.; Teixeira, V.H.; Carvalho, P.; Delgado, L.; Moreira, A. Obesity increases the prevalence and the incidence of asthma and worsens asthma severity. Clin. Nutr. 2017 , 36 , 1068–1074. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Miethe, S.; Karsonova, A.; Karaulov, A.; Renz, H. Obesity and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020 , 146 , 685–693. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vezir, E.; Civelek, E.; Dibek Misirlioglu, E.; Toyran, M.; Capanoglu, M.; Karakus, E.; Kahraman, T.; Ozguner, M.; Demirel, F.; Gursel, I.; et al. Effects of Obesity on Airway and Systemic Inflammation in Asthmatic Children. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021 , 182 , 679–689. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shore, S.A. Obesity and asthma: Lessons from animal models. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007 , 102 , 516–528. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fainardi, V.; Passadore, L.; Labate, M.; Pisi, G.; Esposito, S. An Overview of the Obese-Asthma Phenotype in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022 , 19 , 636. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cunha, P.; Paciência, I.; Cavaleiro Rufo, J.; Castro Mendes, F.; Farraia, M.; Barros, R.; Silva, D.; Delgado, L.; Padrão, P.; Moreira, A.; et al. Dietary Acid Load: A Novel Nutritional Target in Overweight/Obese Children with Asthma? Nutrients 2019 , 11 , 2255. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Barros, R.; Delgado, L. Visceral adipose tissue: A clue to the obesity-asthma endotype(s)? Rev. Port. Pneumol. 2016 , 22 , 253–254. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Sood, A.; Shore, S.A. Adiponectin, Leptin, and Resistin in Asthma: Basic Mechanisms through Population Studies. J. Allergy 2013 , 2013 , 785835. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Patel, S.; Custovic, A.; Smith, J.A.; Simpson, A.; Kerry, G.; Murray, C.S. Cross-sectional association of dietary patterns with asthma and atopic sensitization in childhood—In a cohort study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2014 , 25 , 565–571. [ Google Scholar ]

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013 , 500 , 541–546. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009 , 457 , 480–484. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006 , 444 , 1022–1023. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Halnes, I.; Baines, K.J.; Berthon, B.S.; MacDonald-Wicks, L.K.; Gibson, P.G.; Wood, L.G. Soluble Fibre Meal Challenge Reduces Airway Inflammation and Expression of GPR43 and GPR41 in Asthma. Nutrients 2017 , 9 , 57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Shore, S.A.; Cho, Y. Obesity and Asthma: Microbiome-Metabolome Interactions. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016 , 54 , 609–617. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Calder, P.C.; Ahluwalia, N.; Brouns, F.; Buetler, T.; Clement, K.; Cunningham, K.; Esposito, K.; Jönsson, L.S.; Kolb, H.; Lansink, M.; et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 2011 , 106 (Suppl. 3), S5–S78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Forte, G.C.; da Silva, D.T.R.; Hennemann, M.L.; Sarmento, R.A.; Almeida, J.C.; de Tarso Roth Dalcin, P. Diet effects in the asthma treatment: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018 , 58 , 1878–1887. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mishra, V.; Banga, J.; Silveyra, P. Oxidative stress and cellular pathways of asthma and inflammation: Therapeutic strategies and pharmacological targets. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018 , 181 , 169–182. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kudo, M.; Ishigatsubo, Y.; Aoki, I. Pathology of asthma. Front. Microbiol. 2013 , 4 , 263. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Aghasafari, P.; George, U.; Pidaparti, R. A review of inflammatory mechanism in airway diseases. Inflamm. Res. 2019 , 68 , 59–74. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pijnenburg, M.W.; De Jongste, J.C. Exhaled nitric oxide in childhood asthma: A review. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2008 , 38 , 246–259. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tenero, L.; Zaffanello, M.; Piazza, M.; Piacentini, G. Measuring Airway Inflammation in Asthmatic Children. Front. Pediatr. 2018 , 6 , 196. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bowler, R.P. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004 , 4 , 116–122. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wallace, T.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Chen, C.O.; Crowe-White, K.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Johnson, E.; Lewis, R.; et al. Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020 , 60 , 2174–2211. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Berthon, B.S.; Macdonald-Wicks, L.K.; Gibson, P.G.; Wood, L.G. Investigation of the association between dietary intake, disease severity and airway inflammation in asthma. Respirology 2013 , 18 , 447–454. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- DeVries, A.; Vercelli, D. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Asthma. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016 , 13 (Suppl. 1), S48–S50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kabesch, M.; Michel, S.; Tost, J. Epigenetic mechanisms and the relationship to childhood asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2010 , 36 , 950–961. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Norman, R.E.; Carpenter, D.O.; Scott, J.; Brune, M.N.; Sly, P.D. Environmental exposures: An underrecognized contribution to noncommunicable diseases. Rev. Environ. Health 2013 , 28 , 59–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Mendes, F.C.; Paciência, I.; Cavaleiro Rufo, J.; Silva, D.; Delgado, L.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P. Dietary Acid Load Modulation of Asthma-Related miRNAs in the Exhaled Breath Condensate of Children. Nutrients 2022 , 14 , 1147. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cunha, P.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P.; Delgado, L. Dietary diversity and childhood asthma—Dietary acid load, an additional nutritional variable to consider. Allergy 2020 , 75 , 2418–2420. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Romieu, I.; Barraza-Villarreal, A.; Escamilla-Núñez, C.; Texcalac-Sangrador, J.L.; Hernandez-Cadena, L.; Díaz-Sánchez, D.; De Batlle, J.; Del Rio-Navarro, B.E. Dietary intake, lung function and airway inflammation in Mexico City school children exposed to air pollutants. Respir. Res. 2009 , 10 , 122. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Cardinale, F.; Tesse, R.; Fucilli, C.; Loffredo, M.S.; Iacoviello, G.; Chinellato, I.; Armenio, L. Correlation between exhaled nitric oxide and dietary consumption of fats and antioxidants in children with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007 , 119 , 1268–1270. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mendes, F.C.; Paciência, I.; Cavaleiro Rufo, J.; Farraia, M.; Silva, D.; Padrão, P.; Delgado, L.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P. Higher diversity of vegetable consumption is associated with less airway inflammation and prevalence of asthma in school-aged children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021 , 32 , 925–936. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Metsälä, J.; Vuorinen, A.L.; Takkinen, H.M.; Peltonen, E.J.; Ahonen, S.; Åkerlund, M.; Tapanainen, H.; Mattila, M.; Toppari, J.; Ilonen, J.; et al. Longitudinal consumption of fruits and vegetables and risk of asthma by 5 years of age. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2023 , 34 , e13932. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sdona, E.; Ekström, S.; Andersson, N.; Hallberg, J.; Rautiainen, S.; Håkansson, N.; Wolk, A.; Kull, I.; Melén, E.; Bergström, A. Fruit, vegetable and dietary antioxidant intake in school age, respiratory health up to young adulthood. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022 , 52 , 104–114. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wood, L.G.; Garg, M.L.; Powell, H.; Gibson, P.G. Lycopene-rich treatments modify noneosinophilic airway inflammation in asthma: Proof of concept. Free Radic. Res. 2008 , 42 , 94–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wood, L.G.; Garg, M.L.; Smart, J.M.; Scott, H.A.; Barker, D.; Gibson, P.G. Manipulating antioxidant intake in asthma: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012 , 96 , 534–543. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Seyedrezazadeh, E.; Moghaddam, M.P.; Ansarin, K.; Vafa, M.R.; Sharma, S.; Kolahdooz, F. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of wheezing and asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2014 , 72 , 411–428. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hosseini, B.; Berthon, B.S.; Wark, P.; Wood, L.G. Effects of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Risk of Asthma, Wheezing and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017 , 9 , 341. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/fsrg (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Vinolo, M.A.; Rodrigues, H.G.; Nachbar, R.T.; Curi, R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2011 , 3 , 858–876. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Thorburn, A.N.; Macia, L.; Mackay, C.R. Diet, metabolites, and “western-lifestyle” inflammatory diseases. Immunity 2014 , 40 , 833–842. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Zapolska-Downar, D.; Siennicka, A.; Kaczmarczyk, M.; Kołodziej, B.; Naruszewicz, M. Butyrate inhibits cytokine-induced VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in cultured endothelial cells: The role of NF-kappaB and PPARalpha. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2004 , 15 , 220–228. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Ferstl, R.; Loeliger, S.; Westermann, P.; Rhyner, C.; Schiavi, E.; Barcik, W.; Rodriguez-Perez, N.; Wawrzyniak, M.; et al. High levels of butyrate and propionate in early life are associated with protection against atopy. Allergy 2019 , 74 , 799–809. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tabak, C.; Wijga, A.H.; de Meer, G.; Janssen, N.A.; Brunekreef, B.; Smit, H.A. Diet and asthma in Dutch school children (ISAAC-2). Thorax 2006 , 61 , 1048–1053. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Han, Y.Y.; Forno, E.; Brehm, J.M.; Acosta-Pérez, E.; Alvarez, M.; Colón-Semidey, A.; Rivera-Soto, W.; Campos, H.; Litonjua, A.A.; Alcorn, J.F.; et al. Diet, interleukin-17, and childhood asthma in Puerto Ricans. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015 , 115 , 288–293.e1. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- de Souza, R.G.M.; Schincaglia, R.M.; Pimentel, G.D.; Mota, J.F. Nuts and Human Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2017 , 9 , 1311. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Krogulska, A.; Dynowski, J.; Jędrzejczyk, M.; Sardecka, I.; Małachowska, B.; Wąsowska-Królikowska, K. The impact of food allergens on airway responsiveness in schoolchildren with asthma: A DBPCFC study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2016 , 51 , 787–795. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chatzi, L.; Apostolaki, G.; Bibakis, I.; Skypala, I.; Bibaki-Liakou, V.; Tzanakis, N.; Kogevinas, M.; Cullinan, P. Protective effect of fruits, vegetables and the Mediterranean diet on asthma and allergies among children in Crete. Thorax 2007 , 62 , 677–683. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Du Toit, G.; Roberts, G.; Sayre, P.H.; Bahnson, H.T.; Radulovic, S.; Santos, A.F.; Brough, H.A.; Phippard, D.; Basting, M.; Feeney, M.; et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 , 372 , 803–813. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Depner, M.; Schaub, B.; Loss, G.; Genuneit, J.; Pfefferle, P.; Hyvärinen, A.; Karvonen, A.M.; Riedler, J.; et al. Increased food diversity in the first year of life is inversely associated with allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014 , 133 , 1056–1064. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mazzocchi, A.; Leone, L.; Agostoni, C.; Pali-Schöll, I. The Secrets of the Mediterranean Diet. Does [Only] Olive Oil Matter? Nutrients 2019 , 11 , 2941. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Calder, P.C. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015 , 1851 , 469–484. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wood, L.G.; Garg, M.L.; Gibson, P.G. A high-fat challenge increases airway inflammation and impairs bronchodilator recovery in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011 , 127 , 1133–1140. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Venter, C.; Meyer, R.; Nwaru, B.; Roduit, C.; Untersmayr, E.; Adel-Patient, K.; Agache, I.; Agostoni, C.; Akdis, C.; Bischoff, S.; et al. EAACI Position Paper: Influence of Dietary Fatty Acids on Asthma, Food Allergy and Atopic Dermatitis. Allergy 2019 , 74 , 1429–1444. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Barros, R.; Moreira, A.; Fonseca, J.; Delgado, L.; Castel-Branco, M.G.; Haahtela, T.; Lopes, C.; Moreira, P. Dietary intake of α-linolenic acid and low ratio of n -6: n -3 PUFA are associated with decreased exhaled NO and improved asthma control. Br. J. Nutr. 2011 , 106 , 441–450. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Cazzoletti, L.; Zanolin, M.E.; Spelta, F.; Bono, R.; Chamitava, L.; Cerveri, I.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Grosso, A.; Mattioli, V.; Pirina, P.; et al. Dietary fats, olive oil and respiratory diseases in Italian adults: A population-based study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019 , 49 , 799–807. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Kim, J.L.; Elfman, L.; Mi, Y.; Johansson, M.; Smedje, G.; Norbäck, D. Current asthma and respiratory symptoms among pupils in relation to dietary factors and allergens in the school environment. Indoor Air 2005 , 15 , 170–182. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yang, H.; Xun, P.; He, K. Fish and fish oil intake in relation to risk of asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013 , 8 , e80048. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Papamichael, M.M.; Shrestha, S.K.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Erbas, B. The role of fish intake on asthma in children: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2018 , 29 , 350–360. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, G.Q.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Luo, C.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.L.; Sinha, A.; Li, Z.Y. Fish intake during pregnancy or infancy and allergic outcomes in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017 , 28 , 152–161. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Woods, R.K.; Thien, F.C.; Abramson, M.J. Dietary marine fatty acids (fish oil) for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002 , 2 , Cd001283. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anandan, C.; Nurmatov, U.; Sheikh, A. Omega 3 and 6 oils for primary prevention of allergic disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2009 , 64 , 840–848. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Burney, P. A diet rich in sodium may potentiate asthma. Epidemiologic evidence for a new hypothesis. Chest 1987 , 91 (Suppl. 6), 143s–148s. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mickleborough, T.D.; Fogarty, A. Dietary sodium intake and asthma: An epidemiological and clinical review. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006 , 60 , 1616–1624. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Burney, P.G. The causes of asthma—Does salt potentiate bronchial activity? Discussion paper. J. R. Soc. Med. 1987 , 80 , 364–367. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Britton, J.; Pavord, I.; Richards, K.; Knox, A.; Wisniewski, A.; Weiss, S.; Tattersfield, A. Dietary sodium intake and the risk of airway hyperreactivity in a random adult population. Thorax 1994 , 49 , 875–880. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ardern, K.D. Dietary salt reduction or exclusion for allergic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004 , 3 , Cd000436. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pogson, Z.; McKeever, T. Dietary sodium manipulation and asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011 , 2011 , Cd000436. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sozańska, B.; Pearce, N.; Dudek, K.; Cullinan, P. Consumption of unpasteurized milk and its effects on atopy and asthma in children and adult inhabitants in rural Poland. Allergy 2013 , 68 , 644–650. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Loss, G.; Apprich, S.; Waser, M.; Kneifel, W.; Genuneit, J.; Büchele, G.; Weber, J.; Sozanska, B.; Danielewicz, H.; Horak, E.; et al. The protective effect of farm milk consumption on childhood asthma and atopy: The GABRIELA study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011 , 128 , 766–773.e4. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Woods, R.K.; Walters, E.H.; Raven, J.M.; Wolfe, R.; Ireland, P.D.; Thien, F.C.K.; Abramson, M.J. Food and nutrient intakes and asthma risk in young adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003 , 78 , 414–421. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Berthon, B.S.; Wood, L.G. Nutrition and Respiratory Health—Feature Review. Nutrients 2015 , 7 , 1618–1643. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Garcia-Larsen, V.; Del Giacco, S.R.; Moreira, A.; Bonini, M.; Charles, D.; Reeves, T.; Carlsen, K.H.; Haahtela, T.; Bonini, S.; Fonseca, J.; et al. Asthma and dietary intake: An overview of systematic reviews. Allergy 2016 , 71 , 433–442. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Reyes-Angel, J.; Han, Y.Y.; Litonjua, A.A.; Celedón, J.C. Diet and asthma: Is the sum more important than the parts? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021 , 148 , 706–707. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Morrissey, E.; Giltinan, M.; Kehoe, L.; Nugent, A.P.; McNulty, B.A.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Sodium and Potassium Intakes and Their Ratio in Adults (18–90 y): Findings from the Irish National Adult Nutrition Survey. Nutrients 2020 , 12 , 938. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Medina-Remón, A.; Kirwan, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Estruch, R. Dietary patterns and the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, and neurodegenerative diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018 , 58 , 262–296. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Blonstein, A.C.; Lv, N.; Camargo, C.A.; Wilson, S.R.; Buist, A.S.; Rosas, L.G.; Strub, P.; Ma, J. Acceptability and feasibility of the ‘DASH for Asthma’ intervention in a randomized controlled trial pilot study. Public Health Nutr. 2016 , 19 , 2049–2059. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Li, Z.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Dumas, O.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Leynaert, B.; Pison, C.; Le Moual, N.; Romieu, I.; Siroux, V.; Camargo, C.A.; et al. Longitudinal study of diet quality and change in asthma symptoms in adults, according to smoking status. Br. J. Nutr. 2017 , 117 , 562–571. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Zhang, P.; Lopez, R.; Arrigain, S.; Rath, M.; Khatri, S.B.; Zein, J.G. Dietary patterns in patients with asthma and their relationship with asthma-related emergency room visits: NHANES 2005–2016. J. Asthma 2021 , 59 , 2051–2059. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ma, J.; Strub, P.; Lv, N.; Xiao, L.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Buist, A.S.; Lavori, P.W.; Wilson, S.R.; Nadeau, K.C.; Rosas, L.G. Pilot randomised trial of a healthy eating behavioural intervention in uncontrolled asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2016 , 47 , 122–132. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Garcia-Marcos, L.; Castro-Rodriguez, J.A.; Weinmayr, G.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Priftis, K.N.; Nagel, G. Influence of Mediterranean diet on asthma in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2013 , 24 , 330–338. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Papamichael, M.M.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Susanto, N.H.; Erbas, B. Does adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern reduce asthma symptoms in children? A systematic review of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2017 , 20 , 2722–2734. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Koumpagioti, D.; Boutopoulou, B.; Moriki, D.; Priftis, K.N.; Douros, K. Does Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Have a Protective Effect against Asthma and Allergies in Children? A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022 , 14 , 1618. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tarazona-Meza, C.E.; Hanson, C.; Pollard, S.L.; Romero Rivero, K.M.; Galvez Davila, R.M.; Talegawkar, S.; Rojas, C.; Rice, J.L.; Checkley, W.; Hansel, N.N. Dietary patterns and asthma among Peruvian children and adolescents. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020 , 20 , 63. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Menezes, A.M.B.; Schneider, B.C.; Oliveira, V.P.; Prieto, F.B.; Silva, D.L.R.; Lerm, B.R.; da Costa, T.B.; Bouilly, R.; Wehrmeister, F.C.; Gonçalves, H.; et al. Longitudinal Association Between Diet Quality and Asthma Symptoms in Early Adult Life in a Brazilian Birth Cohort. J. Asthma Allergy 2020 , 13 , 493–503. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Amazouz, H.; Roda, C.; Beydon, N.; Lezmi, G.; Bourgoin-Heck, M.; Just, J.; Momas, I.; Rancière, F. Mediterranean diet and lung function, sensitization, and asthma at school age: The PARIS cohort. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2021 , 32 , 1437–1444. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Douros, K.; Thanopoulou, M.I.; Boutopoulou, B.; Papadopoulou, A.; Papadimitriou, A.; Fretzayas, A.; Priftis, K.N. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and inflammatory markers in children with asthma. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2019 , 47 , 209–213. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Papamichael, M.M.; Katsardis, C.; Lambert, K.; Tsoukalas, D.; Koutsilieris, M.; Erbas, B.; Itsiopoulos, C. Efficacy of a Mediterranean diet supplemented with fatty fish in ameliorating inflammation in paediatric asthma: A randomised controlled trial. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019 , 32 , 185–197. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, J.; Fu, W.; Liu, S.; Gong, C.; Dai, J. Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and childhood for asthma in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019 , 54 , 949–961. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Varraso, R.; Chiuve, S.E.; Fung, T.T.; Barr, R.G.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Camargo, C.A. Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among US women and men: Prospective study. BMJ 2015 , 350 , h286. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Visser, E.; de Jong, K.; Pepels, J.J.S.; Kerstjens, H.A.M.; Ten Brinke, A.; van Zutphen, T. Diet quality, food intake and incident adult-onset asthma: A Lifelines Cohort Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023 , 62 , 1635–1645. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Han, Y.Y.; Jerschow, E.; Forno, E.; Hua, S.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Perreira, K.M.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Afshar, M.; Punjabi, N.M.; Thyagarajan, B.; et al. Dietary Patterns, Asthma, and Lung Function in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020 , 17 , 293–301. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- de Castro Mendes, F.; Paciência, I.; Rufo, J.C.; Farraia, M.; Silva, D.; Padrão, P.; Delgado, L.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P. Increasing Vegetable Diversity Consumption Impacts the Sympathetic Nervous System Activity in School-Aged Children. Nutrients 2021 , 13 , 1456. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Moreira, A.; Moreira, P.; Delgado, L.; Fonseca, J.; Teixeira, V.; Padrão, P.; Castel-Branco, G. Pilot study of the effects of n -3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on exhaled nitric oxide in patients with stable asthma. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2007 , 17 , 309–313. [ Google Scholar ] [ PubMed ]

- Li, J.; Pora, B.L.R.; Dong, K.; Hasjim, J. Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid and its bioavailability: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021 , 9 , 5229–5243. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Lerman, J.L.; Tooze, J.A.; Wilson, M.M.; Reedy, J. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2018 , 118 , 1591–1602. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Wood, L.G.; Gibson, P.G. Dietary factors lead to innate immune activation in asthma. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009 , 123 , 37–53. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Frias-Toral, E.; Laudisio, D.; Pugliese, G.; Castellucci, B.; Garcia-Velasquez, E.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. Nutrition and immune system: From the Mediterranean diet to dietary supplementary through the microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021 , 61 , 3066–3090. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

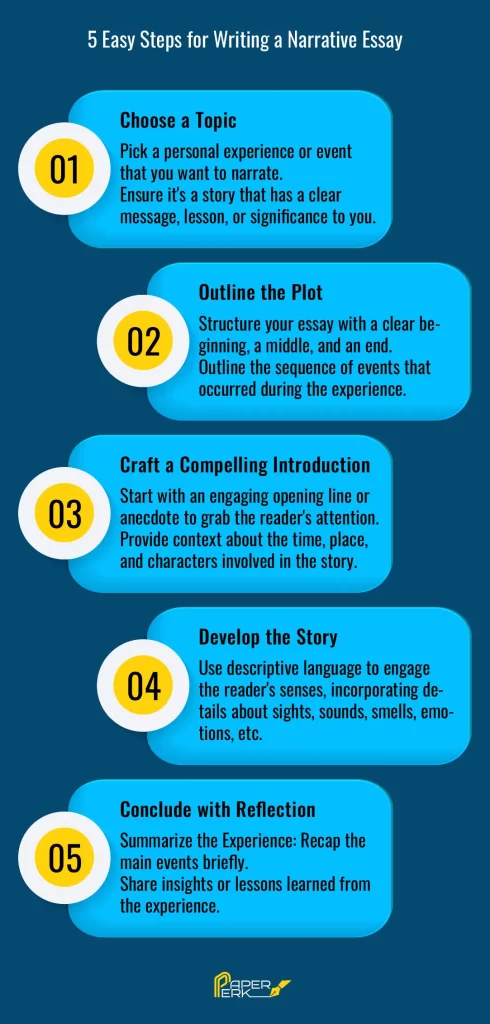

Click here to enlarge figure

| Fruits and Vegetables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Romieu et al., 2009, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 208 children (median age (years)) (quartiles (Q)25, Q75)), comprising 158 asthmatic children, 9.6 (7.9, 11.0 y), and fifty non-asthmatic children, 9.3 (7.9, 11.5 y). | Dietary intake assessed through a 108-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ): fruit and vegetable index (FVI); Mediterranean diet index (MDI) were constructed. | Higher FVI: (+) inflammation. Higher MDI: (+) lung function. |

| Cardinale et al., 2007, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 130 children with mild-to-moderate asthma were included (mean age: N/R). | Dietary intake assessed by 4-point FFQ: 8 food items (margarine, butter, milk, fresh fruit, tomatoes, salad, cooked vegetables and nuts). | Higher consumption of salad: (+) FENO levels. |

| Mendes et al., 2021, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, 647 children, with 44 asthmatics, were included. mean age = 8.81 ± 0.80 y. | Vegetable intake and fruit intake were assessed by a single self-reported 24-h recall questionnaire. A diversity score for fruits and vegetables was built. | Higher daily vegetable diversity intake: (+) asthma prevalence; (+) airway inflammation; (+) breathing difficulties. |

| Metsälä et al., 2023, Cohort study [ ] | In total, 3053 children, with 184 incidents with asthma. Children were evaluated up to 5 years of age. | Child’s food consumption were assessed by 3-day food records at the age of 3 and 6 months, and at 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years of age. Consumption of processed and unprocessed fruits and vegetables was calculated. | All fruits and vegetables intake: (=) asthma prevalence. Leafy vegetables and unprocessed vegetables intake: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Wood et al., 2008, Randomized controlled trial [ ] | Thirty-two asthmatic adults, mean age ± SEM = 52.1 ± 2.4 y. | Follow-up of a low-antioxidant diet during 10 days, then commence of a randomized, cross-over trial involving 3 × 7-day treatment arms (placebo, tomato extract (45 mg lycopene/day) and tomato juice (45 mg lycopene/day). | Lower intake of antioxidant-rich foods: (−) asthma control; (−) lung function. Lycopene-rich treatments (tomato juice): (+) airway inflammation. |

| Wood et al., 2012, Randomized controlled trial [ ] | In total, 137 asthmatics adults were included, mean age: high-antioxidant diet: 54 ± 14 y; and low-antioxidant diet: 58 ± 15 y. | Individuals were assigned to a high-antioxidant diet (n = 46) or a low-antioxidant diet (n = 91) for 14days and then subjects on the high-antioxidant diet received placebo and subjects on the low-antioxidant diet received placebo or tomato extract (45 mg lycopene/d). | High-antioxidant diet: (+) FEV1, and (+) FVC. Antioxidant supplementation: (=) asthma exacerbations (improvements were only observed after increasing fruit and vegetable consumption). |

| Seyedrezazadeh et al., 2014, Meta-analysis [ ] | Adult and children, papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 42): cohort studies (n = 12); case-control studies (n = 4); cross-sectional studies (n = 26). | Fruit and vegetable intake. | High intake of fruit and vegetables: (+) asthma prevalence; (+) wheezing prevalence. |

| Hosseini et al., 2017, Meta-analysis [ ] | Adult and children, papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 58): cross-sectional (n = 30); cohort studies (n = 13); case-control studies (n = 8); experimental designs (n = 7). | Fruit and vegetable intake. | Vegetable intake: (+) asthma prevalence. Fruit intake: (+) wheeze prevalence; (+) asthma severity prevalence. Fruit and vegetable intake: (+) airway/systemic inflammation. |

| Fiber | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Halnes et al., 2017, Randomized controlled trial [ ] | Twenty-nine subjects with stable asthma, mean age: soluble fiber group: 42.1 ± 3.4 y, control group: 40.4 ± 4.6 y. | Effect of a single meal rich in soluble fiber (175 g yogurt with 3.5 g inulin and probiotics) compared with a simple carbohydrate meal (200 g of mashed potato) on asthmatic airway inflammation. | Soluble fiber intake: (+) inflammation; (+) lung function. |

| Tabak et al., 2006, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 598 children, with 39 asthmatics, mean age: 10.4 ± 1.2 y. | Dietary intake was estimated using a semi-quantitative FFQ. | Whole grain products intake: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Berthon BS et al., 2013, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, 202 participants, with 137 stable asthmatics. Mean age: healthy controls: 46.7 ± 17.4 y; intermittent, mild, and moderate persistent asthma: 54.5 ± 15.5 y; severe persistent asthma: 57.8 ± 14.4 y. | Dietary intake was estimated through a 186-item semi-quantitative FFQ. | Less fiber intake: (−) forced volume in 1 s (FEV1); (−) airway eosinophilia. |

| Han YY, et al., 2015, Case-control [ ] | A total of 678 children, with 351 asthmatics. Mean age: controls: 10.5 ± 2.7 y, asthma: 10.0 ± 2.6 y. | Dietary intake was assessed through a 75-item questionnaire regarding the child’s food consumption, including wholegrains in the prior week. | High consumption of wholegrains: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Nuts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Chatzi, L. et al., 2007, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 690 children aged 7 to 18 years, mean age: N/R. | Dietary intake was assessed through a 58-item FFQ, including nuts consumption. | High consumption of nuts: (+) wheezing prevalence. |

| Du Toit, G. et al., 2015, Randomized trial [ ] | In total, 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both. Mean age: 7.8 ± 1.7 months. | Participants were stratified into two study cohorts based on the results of a skin-prick test for peanut allergy and were then randomly assigned to a group in which dietary peanuts would be consumed, or to a group in which its consumption would be avoided. | Peanut consumption: (=) asthma at 5 y. |

| Roduit et al., 2014, Cohort study [ ] | A total of 856 children (from 3–12 months to 6 years old) Mean age: N/R. | Assessment of introduction of nuts in the first year of life. | Introduction of nuts in the first year of life: (=) asthma at 6 y. |

| Fats and Fish | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Berthon BS et al., 2013, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, there were 202 participants, with 137 stable asthmatics, and 65 healthy controls. Mean age: healthy controls: 46.7 ± 17.4 y; intermittent, mild, and moderate persistent asthma: 54.5 ± 15.5 y; severe persistent asthma: 57.8 ± 14.4 y. | Dietary intake was estimated using a 186-item semi-quantitative FFQ. | Higher fat intake: (−) FEV1; (−) airway eosinophilia. Saturated fat: (−) airway inflammation. |

| Cardinale et al., 2007, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 130 children with mild to moderate asthma (mean age: N/R). | Dietary intake was estimated using a 4-point food-consumption frequency questionnaire: 8 food items (butter, margarine, milk, tomatoes, fresh fruit, cooked vegetables, salad, and nuts). | Higher butter intake: (−) FENO levels; (−) clinical score severity of asthma. |

| Tabak et al., 2006, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, there were 598 children, with 39 asthmatics. Mean age: 10.4 ± 1.2 y. | Dietary intake was estimated using a semi-quantitative FFQ. | Fish Intake: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Wood LG et al., 2011, Randomized controlled trial [ ] | Seventy-two adults, with fifty-one asthmatics. Mean age ± SEMs: Healthy controls high-fat: 49.6 ± 4.6 y. Asthma low-fat/low-energy: 41.7 ± 3.2 y. Asthma-high-fat/high-energy, nonobese: 50.9 ± 4.3 y. Asthma high-fat/high-energy, obese: 56.5 ± 4.3 y. | High-fat/high meal challenge; high-trans (n = 5) or non-trans (n = 5) fatty acid meal challenge. | High-fat/high-energy meal: (−) airway inflammation; (−) bronchodilator responsiveness. High-trans fatty acid meal: (−) airway inflammation. |

| Cazzoletti L et al., 2019, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 871 subjects, with 145 asthmatics. Mean age: controls: 51.5 ± 11.5 y. asthmatics: 49.5 ± 11.7 y. | Food intake was collected using an FFQ. | Oleic acid and of olive oil intake: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Barros R et al., 2011, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 174 adult asthmatics. Mean age ± SD: 40 ± 15 years. | Dietary intake was obtained by an FFQ. | High n-6:n-3 PUFA ratio: (−) airway inflammation; (−) asthma control. |

| Kim JL et al., 2005, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, there were 1014 children, with 78 asthmatics. Median age: 9 (range 5–14 years). | Current consumption and frequency of fish. | Fish consumption: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Yang H et al., 2013, Meta-analysis [ ] | Adults and children, papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 8), consisting of prospective cohort studies (n = 8). | Fish and fish oil intake. | Fish consumption: (+) asthma prevalence in children; (=) asthma prevalence in adults. |

| Papamichael MM et al., 2018, Meta-analysis [ ] | Children, papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 23): cross-sectional studies (n = 12); case-control studies (n = 2); cohort studies (n = 9). | Fish intake. | All fish (lean and fatty) consumption: (+) asthma prevalence; (+) wheeze prevalence in children up to 4.5 y. Fatty fish consumption: (+) asthma prevalence in children 8 to 14 y. |

| Zhang GQ et al., 2017, Meta-analysis [ ] | Papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 19): cohort studies (n = 8) for fish intake in infancy. | Fish intake during pregnancy or infancy. | Fish consumption: (=) asthma prevalence. |

| Salt | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Ardern KD et al., 2004, Systematic Review [ ] | Studies included in the systematic review (n = 6). Six RCTs were included in the review. | Salt intake. | Dietary salt reduction: (=) symptoms of allergic asthma. |

| Pogson Z et al., 2011, Systematic Review [ ] | Studies included in the systematic review (n = 9): nine RCTs in relation to sodium manipulation and asthma, of which five were in people with asthma (318 participants), and four in people with exercise-induced asthma (63 participants). | Salt intake. | Dietary salt reduction: (+) lung function; (+) symptoms of asthma. |

| Dairy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Han YY, et al., 2015, Case-control [ ] | A total of 678 children, with 351 asthmatics. Mean age: controls: 10.5 ± 2.7 y. asthma: 10.0 ± 2.6 y. | Dietary intake was estimated using a 75-item questionnaire on the child’s food consumption, including dairy, in the prior week. | Frequent consumption of dairy products: (−) asthma prevalence. |

| Sozańska B, et al., 2013, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, there were 1700 children, with 78 asthmatics. Mean age: N/R. | Assessment of consumption of unpasteurized milk in the first year of life. | Consumption of unpasteurized milk: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Loss G, et al., 2011, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, there were 8334 school-aged children, with 2033 asthmatics. Mean age: N/R. | A comprehensive questionnaire about farm milk consumption was completed by the parents. | Consumption of farm milk: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Woods RK, et al., 2003, Cross-sectional [ ] | In total, 1601 young adults were included, with 180 asthmatics. mean age: 34.6 ± 7.1 y. | Semiquantitative FFQ, which assessed their habitual food intake over the preceding 12 months. | Whole milk consumption: (+) asthma prevalence. Consumption of low-fat cheese: (−) asthma prevalence. Ricotta cheese intake: (−) asthma prevalence. |

| Dietary Patterns | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year, Study Design | Sample, Age | Dietary Assessment/Intervention | Results |

| Andrianasolo RM, et al., 2018, Cross-sectional [ ] | A total of 34,766 adults were included, mean age by tertiles of the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010): Women: 1st: 46.7 ± 13.4; 2nd: 53.5 ± 13.1; and 3rd: 57.3 ± 12.4. Men: 1st: 55.8 ± 14.2; 2nd: 60.2 ± 13.0; and 3rd: 62.5 ± 12.0). | Quality of diet was evaluated by three dietary scores: the AHEI-2010, the literature-based adherence score to Mediterranean diet (MEDI-LITE), and the modified Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score (mPNNS-GS) through FFQ. | Higher dietary scores assessed by AHEI-2010, MEDI-LITE, and mPNNS-GS: (+) asthma symptom score. |

| Patel S, et al., 2014, Cohort study [ ] | 1252 children. Follow-up age 8, mean age: 7.98 ± 0.17. Follow-up age 11, mean age: 11.5 ± 0.54. | Dietary Patterns were obtained through FFQ: ‘Traditional’—mostly fruit and vegetables with meat and oily fish ‘Western’—mostly processed foods, which are associated with a modern Western diet (chips, crisps, and pizza) ‘Other’—mostly items that are eaten by people following a vegetarian diet (lentils, soya, rice, and nuts) but also contained fried foods, offal, and pastry dishes. | Following a strict western diet: (−) asthma prevalence. |

| Zhang Y et al., 2021, Cross Sectional [ ] | A total of 1681 individuals, mean age: N/R. | 2015 Healthy Eating Index (HEI-2015). | Low fruit and vegetable intake and low mean ± SE HEI-2015 score: (−) asthma prevalence. |

| Ma J et al., 2016, Pilot randomized trial [ ] | Ninety adults, mean age: 51.8 ± 12.4 y. | 6-month behavioral intervention promoting the DASH diet in patients with uncontrolled persistent asthma. | Adherence to DASH diet: (+) asthma control; (+) asthma-related quality of life. |

| Garcia-Marcos L et al., 2013, Systematic review and meta-analysis [ ] | Children, papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 8), comprising cross-sectional studies (n = 8). | Mediterranean diet. | Higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet during childhood: (+) wheeze prevalence; (+) asthma prevalence; (=) severe current wheeze prevalence. |

| Papamichael MM et al., 2017, Systematic review [ ] | Children Papers included in the systematic review (n = 15): cross-sectional studies (n = 11); intervention trial (n = 1); case-control studies (n = 1); cohort studies (n = 2). | Mediterranean diet. | Following a Mediterranean dietary pattern: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Tarazona-Meza CE et al., 2020, Cross-sectional study (nested in a case-control study) [ ] | A total of 767 children and adolescents were included (573 with asthma and 194 controls), mean age: 13.8 ± 2.6 y | Diet was assessed using an FFQ, with food groups classified as “healthy” or “unhealthy”. | Better diet quality: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Menezes AMB et al., 2020, Cohort study [ ] | In total, there were 2986 young individuals. 1st evaluation: 18 years. 2nd evaluation: 22 years. | Longitudinal study with follow-up information from 18- and 22-year-olds. Diet quality was measured with a revised version of the Healthy Eating Index (IQD-R) for the Brazilian population at 18 y and 22 y with FFQ referring to the last 12 months. | Higher values in the Revised Brazilian Healthy Eating Index score, both at 18 and 22 y: (+) wheezing prevalence. Remaining on a poor diet from age 18 to 22 y: (−) wheezing prevalence. |

| Amazouz H et al., 2021, Cross sectional study [ ] | In total, 975 school-aged children were included, age of evaluation: 8 y. | Adherence to the MD was assessed with FFQ and based on two scores: the KIDMED index and the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS). | Higher tertile group of adherences to the Mediterranean diet: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Koumpagioti D et al., 2022, Systematic review [ ] | Children, papers included in the systematic review (n = 12): cross-sectional studies (n = 7); randomized controlled trial (n = 1); case-control studies (n = 1); cohort studies (n = 1). | Adherence to MD was measured by diet quality indices as KIDMED and MDS. | Adherence to MD: (+) asthma prevalence. |

| Douros K et al., 2019, Cross-sectional study [ ] | Seventy children, mean age: asthmatic: 8.9 ± 2.4 y. Non-asthmatic: 8.6 ± 2.1 y. | Adherence to MD was estimated with the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for children and adolescents (KIDMED) score | Higher adherence to MD: (+) IL-4 and IL-17 values. |

| Papamichael et al., 2019, Randomized controlled trial [ ] | Seventy-two asthmatic children, mean age: 7.98 ± 2.24 y. | A single-centered, 6-month, parallel randomized controlled trial comparing the consumption of a Mediterranean diet supplemented with two meals of 150 g of cooked fatty fish weekly (intervention) with the usual diet (control). | Mediterranean diet supplemented with two meals of 150 g of cooked fatty fish: (+) airway inflammation. |

| Zhang Y et al., 2019, A systematic review and meta-analysis [ ] | Papers included in the meta-analysis (n = 16): cross-sectional studies (n = 12); case-control studies (n = 1); cohort studies (n = 5). | Adherence to the Mediterranean diet | Adherence to MD: (=) asthma prevalence; (=) severe asthma prevalence. |

| Visser et al., 2023 Cohort study (105) | A total of 34,698 controls, with 477 incidents of asthma. Mean age: BMI < 25 kg/m : cases: 40.4 ± 13.3 y, Controls: 44.3 ± 12.6 y BMI ≥ 25 kg/m : cases: 46.8 ± 12.5 y, Controls: 49.1 ± 12.0 y | Diet quality-assessed by the Lifelines Diet Score and Mediterranean Diet Score | Higher diet quality: (=) adult-onset asthma prevalence. |

| Varraso et al. (2015), Cohort study [ ] | A total of 73,228 adults. Mean age according to fifths of AHEI-2010: 1st: 48.6 ± 7.2; 2nd: 49.5 ± 7.2; 3rd: 50.3 ± 7.1; 4th: 51.0 ± 7.0; 5th: 52.1 ± 6.8. | Scores of AHEI-2010, assessed by FFQ. | High AHEI-2010 scores: (=) adult-onset asthma prevalence. |

| Han et al. (2020), Cross-sectional study [ ] | A total of 12,687 adults, with 962 asthmatics included. Mean age: no current asthma: 41.4 ± 0.3 y. current asthma: 43.6 ± 0.8 y. | The energy-adjusted Dietary Inflammatory Index [E-DII]) and AHEI-2010 were calculated based on two 24 h dietary recalls. | Higher E-DII score: (+) asthma prevalence; (+) asthma symptoms. AHEI-2010 score: (=) asthma prevalence; (=) asthma symptoms. |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, M.; de Castro Mendes, F.; Delgado, L.; Padrão, P.; Paciência, I.; Barros, R.; Rufo, J.C.; Silva, D.; Moreira, A.; Moreira, P. Diet and Asthma: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2023 , 13 , 6398. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116398

Rodrigues M, de Castro Mendes F, Delgado L, Padrão P, Paciência I, Barros R, Rufo JC, Silva D, Moreira A, Moreira P. Diet and Asthma: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences . 2023; 13(11):6398. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116398

Rodrigues, Mónica, Francisca de Castro Mendes, Luís Delgado, Patrícia Padrão, Inês Paciência, Renata Barros, João Cavaleiro Rufo, Diana Silva, André Moreira, and Pedro Moreira. 2023. "Diet and Asthma: A Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 13, no. 11: 6398. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13116398

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Asthma Res Pract

Asthma and stroke: a narrative review

A. corlateanu.

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Pneumology and Allergology, Nicolae Testemitanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Stefan cel Mare street 165, 2004 Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

S. Covantev

O. corlateanu.

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Nicolae Testemitanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Stefan cel Mare street 165, 2004 Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

N. Siafakas

3 Department of Thoracic Medicine, University General Hospital, Stavrakia, 71110 Heraklion, Crete, Greece

Associated Data

Not applicable.

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation, bronchial reversible obstruction and hyperresponsiveness to direct or indirect stimuli. It is a severe disease causing approximately half a million deaths every year and thus possessing a significant public health burden. Stroke is the second leading cause of death and a major cause of disability worldwide. Asthma and asthma medications may be a risk factors for developing stroke. Nevertheless, since asthma is associated with a variety of comorbidities, such as cardiovascular, metabolic and respiratory, the increased incidence of stroke in asthma patients may be due to a confounding effect. The purpose of this review is to analyze the complex relationship between asthma and stroke.

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation, bronchial reversible obstruction and hyperresponsiveness to direct or indirect stimuli. It is a problem worldwide with estimated 495,000 deaths every year, thus possessing a significant public health burden [ 1 ]. Asthma complications are often the reason for admission to emergency healthcare service and therefore require special attention [ 2 ]. Asthma is not curable, but it should be controlled by continuous patient assessment in two domains: symptoms control and future risk of adverse outcomes [ 1 ]. Poorly controlled asthma and patients with frequent exacerbations show a greater risk for cardiovascular diseases and ischemic stroke [ 3 , 4 ]. It is also revealed that the pharmacotherapy of asthma, including β2-agonists and systemic corticosteroids, has implications in the development of asthma comorbidities such as stroke [ 5 , 6 ]. In addition, as a chronic inflammation, asthma has also a systemic impact by having a correlation with increased atherosclerotic vessel disorders [ 7 ]. However, smokers with asthma compared to non-smokers with asthma have frequent asthma symptoms, more medication use, poorer lung function and higher prevalence of comorbidities [ 3 ]. This raises the question that stroke in asthmatics may be due to confounding effect (smoking).

Stroke is the second leading cause of death and a major cause of disability worldwide, and there is a further increase in its incidence due to expanding population numbers and aging as well as the increased prevalence of modifiable stroke risk factors [ 8 ]. It was demonstrated that stroke may be more frequent in patients with respiratory conditions [ 9 ]. Therefore, there may be a significant interplay between asthma and stroke, as it may be an independent risk factor for stroke, and its severity exhibits a linear response of stroke development [ 10 ]. These facts represent the base for development of neuropulmonology, which emphasizes the importance of the interconnection between the central nervous and respiratory systems for optimizing the management of patients wherein these pathologies co-exist, especially in the neurocritical care environment [ 11 ].

The purpose of this review is to summarize available data on the association between asthma and stroke and to describe their possible pathophysiological links.

AC, SIu, SC performed the literature review using the terms “asthma”, “stroke”, “subarachnoid hemorrhage”, “smoking”, “SABA”, “LABA”, “SAMA”, “LAMA”, “corticosteroids”, “TPA”, “antiepileptic”, “seizure”, “hypoxia”, “aspirin”, “beta blockers”, “angiotensin converting enzyme”, “comorbidities” along with the MESH terms. The reference list of the articles was carefully reviewed as a potential source of information. The search was based on Medline, Scopus and Google Scholar engines. Selected publications were analyzed and their synthesis was used to write the review and support the hypothesis of the relationship between asthma and stroke.

Risk factors

Shared risk factors between asthma and stroke.

Asthma may be categorized by itself as a risk factor for stroke that is independent of basal lung functioning. It can trigger directly cerebral hypoxemic episodes during asthma attacks or can indirectly increase stroke risk by inducing prothrombotic factors and endothelial dysfunction, thus initiating the development of atherothrombosis [ 12 ]. The major risk factors for stroke are history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease; tobacco exposure, older age, stress, depression, sleep disorders, obesity [ 13 ]. Some of these risk factors can also be seen in asthma patients and thus the link between asthma and stroke can be to some degree due to confounding effect (Fig. 1 ).

Overlapping risk factors for asthma and stroke

A nationwide population-based cohort study was conducted in an Asian population to investigate the effects of asthma on the risk of stroke. The people enrolled in the National Health Insurance program represented the data source, divided into 2 cohorts: patients with newly diagnosed asthma that received treatment (without stroke baseline), were matched for age, sex and index year with 4 reference subjects without asthma. The risk of stroke was analyzed using Cox proportional hazard regression models. The overall incidence of stroke was greater in the asthmatic cohort than in the non-asthmatic cohort (HR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.47–1.60) with an adjusted HR of 1.37 (95% CI = 1.27–1.48) when adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities [ 10 ]. Similar results were registered in 2020 in the HUNT study wherein participants with active asthma showed evidence for a modest increased risk for stroke (adjusted HR 1.17, 95% CI = 0.97–1.41) [ 3 ].

Conversely, a recent Korean study did not find increased ischemic stroke risk among asthma subjects (HR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.86–0.95) [ 14 ]. However, there was a significantly higher risk of stroke among asthma patients who encounter more than 3 exacerbations per year (HR = 3.05, 95% CI = 2.75–3.38) [ 10 ].

Stroke subtypes and asthma