More From Forbes

The six main barriers against problem-solving and how to overcome them.

Challenges. Disputes. Dilemmas. Obstacles. Troubles. Issues. Headaches.

- The uniqueness of every different issue makes the need for an also adapted and individualized solution.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Business people discussing the plan at office photo credit: Getty

There are more than thirty different ways to call all those unpleasant and stressful situations which prevent us from directly achieving what we want to achieve. Life is full of them. This is why the ability to solve problems in an effective and timely manner without any impediments is considered to be one of the most key and critical skill for resolutive and successful leaders. But is not just leaders or top managers facing the way forward. According to a Harvard Bussiness Review survey , people's skills depends on their level on the organization and their particular job and activities. However, when coming to problem-solving, there is a remarkable consistency about the importance of it within all the different measured organization levels.

There are small problems and big problems. Those ones that we laugh about and those that take our sleep away. Problems that affect just us or our whole company. Issues that need to be resolved proactively and others that require us to wait and observe. There is a special kind of problem for every day of our lives, but all of them responds to a common denominator: addressing them adequately. It is our ability to do so what makes the difference between success and failure.

Problems manifest themselves in many different ways. As inconsistent results or performance. As a failure toward standards. As discrepancies between expectations and reality. The uniqueness of every different issue makes the need for an also adapted and individualized solution. This is why finding the way forward can be sometimes tricky. There are many reasons why it is difficult to find a solution to a problem, but you can find the six more common causes and the way to overcome them!

1. Difficulty to recognize that there is a problem

Nobody likes to be wrong. “Cognitive dissonance is what we feel when the self-concept — I’m smart, I’m kind, I’m convinced this belief is true — is threatened by evidence that we did something that wasn’t smart, that we did something that hurt another person, that the belief isn’t true,” explains Carol Tavris.

Problems and mistakes are not easy to digest. To reduce this cognitive dissonance, we need to modify our self-concept or well deny the evidence. Many times is just easier to simply turn our back to an issue and blindly keep going. But the only way to end it up to satisfactory is to make an effort to recognize and accept the evidence. Being wrong is human and until the problem is not acknowledged solutions will never materialize. To fully accept that something is not going the way it should, the easiest way is to focus on the benefits of new approaches and always remain non-judgemental about the causes. Sometimes we may be are afraid of the costs in terms of resources, time and physical or mental efforts that working for the solution may eventually bring. We may need then to project ourselves in all the fatalistic consequences that we will finally encounter in case we continue sunk in the problem. Sometimes we really need to visualize the disaster before accepting a need for change.

2. Huge size problem

Yes! We clearly know that something is going wrong. But the issue is so big that there is no way we can try to solve it without blowing our life into pieces. Fair enough. Some problems are so big that it is not possible to find at once a solution for them. But we can always break them into smaller pieces and visualize the different steps and actions that we could eventually undertake to get to our final goal. Make sure you do not lose sight of the original problem!

3. Poorly framed problem

Without the proper framing, there is no certainty about the appropriate focus on the right problem. Asking the relevant questions is a crucial aspect to it. Does your frame of the problem capture its real essence? Do you have all the background information needed? Can you rephrase the problem and it is still understandable? Have you explored it from different perspectives? Are different people able to understand your frame for the problem correctly? Answering to the right problem in the right way depends 95% on the correct framing of it!

'If I have an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about the solution' (Albert Einstein)

4. Lack of respect for rhythms

There is always a right time for preparation, a right time for action and a right time for patience. Respecting the rhythms of a problem is directly link to the success of the solution. Acting too quickly or waiting too long can have real counterproductive effects. There is a need for enough time to gather information and understand all the different upshots of a planned solution. A balance of action is crucial to avoid both eagerness and laxity. Waiting for the proper time to take action is sometimes the most complicated part of it.

5. Lack of problem'roots identification

It is quite often that we feel something is not going the way it should without clearly identifying what the exact problematic issue is. We are able to frame all the negative effects and consequences, but we do not really get to appropriately verbalized what the problem is all together. Consequently, we tend to fix the symptoms without getting to the real causes. It is as common as dangerous and not sustainable for problem-solving.

Make sure that you have a clear picture of what are the roots of the problem and what are just the manifestations or ramifications of it. Double loop always to make sure that you are not patching over the symptoms but getting to the heart of the matter.

6. Failure to identify the involved parts

Take time to figure out and consult every simple part involved in the problem as well as affected by the possible solution. Problems and solutions always have at the core human needs and impacts. Failing to identify and take into consideration the human factor in the problem-solving process will prevent the whole mechanism from reaching the desired final goal.

'We always hope for the easy fix: the one simple change that will erase a problem in a stroke. But few things in life work this way. Instead, success requires making a hundred small steps go right - one after the other, no slipups, no goofs, everyone pitching in.' ( Atul Gawande)

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

6 Common Problem Solving Barriers and How Can Managers Beat them?

What is the meaning of barriers to problem solving, what are the 6 barriers to problem solving, examples of barriers to problem solving, how to overcome problem solving barriers at work tips for managers, problem solving barriers faqs.

Other Related Blogs

Lack of motivation

Lack of knowledge, lack of resources, emotional barriers, cultural and societal barriers, fear of failure.

- Lack of motivation: A person who lacks motivation may struggle to complete tasks on time or produce quality work. For example, an employee who is disengaged from their job may procrastinate on essential tasks or show up late to work.

- Lack of knowledge : Employees who lack knowledge or training may be unable to perform their duties effectively. For example, a new employee unfamiliar with the company’s software systems may struggle to complete tasks on their computer.

- Lack of resources: Employees may be unable to complete their work due to a lack of resources, such as equipment or technology. For example, a graphic designer who doesn’t have access to the latest design software may struggle to produce high-quality designs.

- Emotional barriers: Emotional barriers can affect an employee’s ability to perform their job effectively. For example, an employee dealing with a personal issue, such as a divorce, may have trouble focusing on their work and meeting deadlines.

- Cultural and societal barriers: Cultural and societal barriers can affect an employee’s ability to work effectively. For example, an employee from a different culture may struggle to communicate effectively with colleagues or may feel uncomfortable in a work environment that is not inclusive.

- Fear of failure : Employees who fear failure may avoid taking on new challenges or may not take risks that could benefit the company. For example, an employee afraid of making mistakes may not take on a leadership role or hesitate to make decisions that could impact the company’s bottom line.

- Identify and Define the Problem: Define the problem and understand its root cause. This will help you identify the obstacles that are preventing effective problem solving.

- C ollaborate and Communicate: Work with others to gather information, generate new ideas, and share perspectives. Effective communication can help overcome misunderstandings and promote creative problem solving.

- Use Creative Problem Solving Techniques: Consider using creative problem solving techniques such as brainstorming, mind mapping, or SWOT analysis to explore new ideas and generate innovative solutions.

- Embrace Flexibility: Be open to new ideas and approaches. Embracing flexibility can help you overcome fixed mindsets and encourage creativity in problem solving.

- Invest in Resources: Ensure that you have access to the necessary resources, such as time, money, or personnel, to effectively solve complex problems.

- Emphasize Continuous Learning: Encourage continuous learning and improvement by seeking feedback, evaluating outcomes, and reflecting on the problem solving process. This can help you identify improvement areas and promote a continuous improvement culture.

How good are you in jumping over problem-solving barriers?

Find out now with the free problem-solving assessment for managers and leaders.

What are the factors affecting problem solving?

What are the five key obstacles to problem solving, can habits be a barrier to problem solving, how do you overcome barriers in problem solving.

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2024, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

Identifying Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology

Problem-solving is a key aspect of psychology, essential for understanding and overcoming challenges in our daily lives. There are common barriers that can hinder our ability to effectively solve problems. From mental blocks to confirmation bias, these obstacles can impede our progress.

In this article, we will explore the various barriers to problem-solving in psychology, as well as strategies to overcome them. By addressing these challenges head-on, we can unlock the benefits of improved problem-solving skills and mental agility.

- Identifying and overcoming barriers to problem-solving in psychology can lead to more effective and efficient solutions.

- Some common barriers include mental blocks, confirmation bias, and functional fixedness, which can all limit critical thinking and creativity.

- Mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, and collaborating with others can help overcome these barriers and lead to more successful problem-solving.

- 1 What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

- 2 Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

- 3.1 Mental Blocks

- 3.2 Confirmation Bias

- 3.3 Functional Fixedness

- 3.4 Lack of Creativity

- 3.5 Emotional Barriers

- 3.6 Cultural Influences

- 4.1 Divergent Thinking

- 4.2 Mindfulness Techniques

- 4.3 Seeking Different Perspectives

- 4.4 Challenging Assumptions

- 4.5 Collaborating with Others

- 5 What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

- 6 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

Problem-solving in psychology refers to the cognitive processes through which individuals identify and overcome obstacles or challenges to reach a desired goal, drawing on various mental processes and strategies.

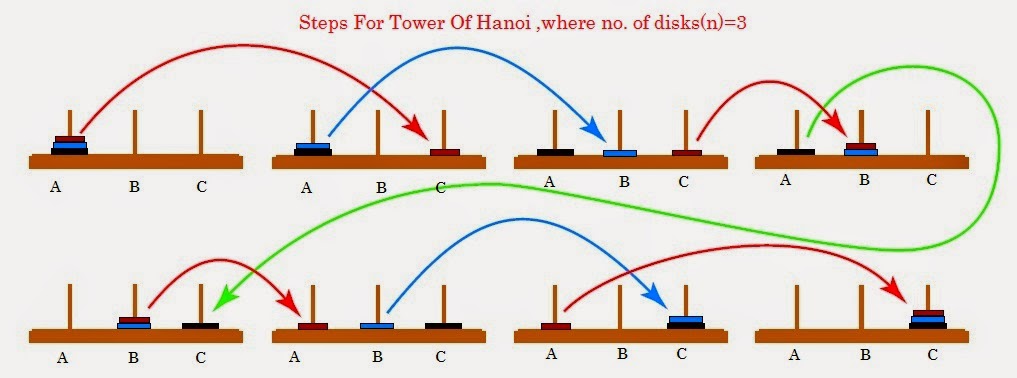

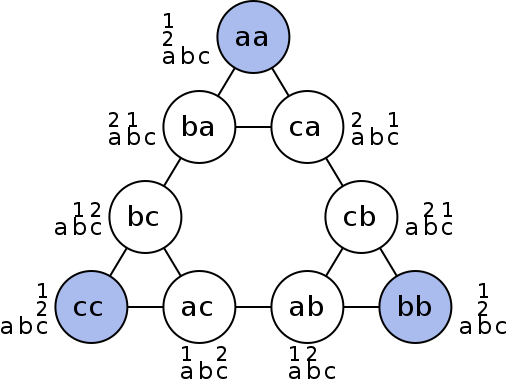

In the realm of cognitive psychology, problem-solving is a key area of study that delves into how people use algorithms and heuristics to tackle complex issues. Algorithms are systematic step-by-step procedures that guarantee a solution, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that provide efficient solutions, albeit without certainty. Understanding these mental processes is crucial in exploring how individuals approach different types of problems and make decisions based on their problem-solving strategies.

Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

Problem-solving holds significant importance in psychology as it facilitates the discovery of new insights, enhances understanding of complex issues, and fosters effective actions based on informed decisions.

Assumptions play a crucial role in problem-solving processes, influencing how individuals perceive and approach challenges. By challenging these assumptions, individuals can break through mental barriers and explore creative solutions.

Functional fixedness, a cognitive bias where individuals restrict the use of objects to their traditional functions, can hinder problem-solving. Overcoming functional fixedness involves reevaluating the purpose of objects, leading to innovative problem-solving strategies.

Through problem-solving, psychologists uncover underlying patterns in behavior, delve into subconscious motivations, and offer practical interventions to improve mental well-being.

What Are the Common Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology?

In psychology, common barriers to problem-solving include mental blocks , confirmation bias , functional fixedness, lack of creativity, emotional barriers, and cultural influences that hinder the application of knowledge and resources to overcome challenges.

Mental blocks refer to the difficulty in generating new ideas or solutions due to preconceived notions or past experiences. Confirmation bias, on the other hand, is the tendency to search for, interpret, or prioritize information that confirms existing beliefs or hypotheses, while disregarding opposing evidence.

Functional fixedness limits problem-solving by constraining individuals to view objects or concepts in their traditional uses, inhibiting creative approaches. Lack of creativity impedes the ability to think outside the box and consider unconventional solutions.

Emotional barriers such as fear, stress, or anxiety can halt progress by clouding judgment and hindering clear decision-making. Cultural influences may introduce unique perspectives or expectations that clash with effective problem-solving strategies, complicating the resolution process.

Mental Blocks

Mental blocks in problem-solving occur when individuals struggle to consider all relevant information, fall into a fixed mental set, or become fixated on irrelevant details, hindering progress and creative solutions.

For instance, irrelevant information can lead to mental blocks by distracting individuals from focusing on the key elements required to solve a problem effectively. This could involve getting caught up in minor details that have no real impact on the overall solution. A fixed mental set, formed by previous experiences or patterns, can limit one’s ability to approach a problem from new perspectives, restricting innovative thinking.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias, a common barrier in problem-solving, leads individuals to seek information that confirms their existing knowledge or assumptions, potentially overlooking contradictory data and hindering objective analysis.

This cognitive bias affects decision-making and problem-solving processes by creating a tendency to favor information that aligns with one’s beliefs, rather than considering all perspectives.

- One effective method to mitigate confirmation bias is by actively challenging assumptions through critical thinking.

- By questioning the validity of existing beliefs and seeking out diverse viewpoints, individuals can counteract the tendency to only consider information that confirms their preconceptions.

- Another strategy is to promote a culture of open-mindedness and encourage constructive debate within teams to foster a more comprehensive evaluation of data.

Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness restricts problem-solving by limiting individuals to conventional uses of objects, impeding the discovery of innovative solutions and hindering the application of insightful approaches to challenges.

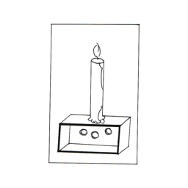

For instance, when faced with a task that requires a candle to be mounted on a wall to provide lighting, someone bound by functional fixedness may struggle to see the potential solution of using the candle wax as an adhesive instead of solely perceiving the candle’s purpose as a light source.

This mental rigidity often leads individuals to overlook unconventional or creative methods, which can stifle their ability to find effective problem-solving strategies.

To combat this cognitive limitation, fostering divergent thinking, encouraging experimentation, and promoting flexibility in approaching tasks can help individuals break free from functional fixedness and unlock their creativity.

Lack of Creativity

A lack of creativity poses a significant barrier to problem-solving, limiting the potential for improvement and hindering flexible thinking required to generate novel solutions and address complex challenges.

When individuals are unable to think outside the box and explore unconventional approaches, they may find themselves stuck in repetitive patterns without breakthroughs.

Flexibility is key to overcoming this hurdle, allowing individuals to adapt their perspectives, pivot when necessary, and consider multiple viewpoints to arrive at innovative solutions.

Encouraging a culture that embraces experimentation, values diverse ideas, and fosters an environment of continuous learning can fuel creativity and push problem-solving capabilities to new heights.

Emotional Barriers

Emotional barriers, such as fear of failure, can impede problem-solving by creating anxiety, reducing risk-taking behavior, and hindering effective collaboration with others, limiting the exploration of innovative solutions.

When individuals are held back by the fear of failure, it often stems from a deep-seated worry about making mistakes or being judged negatively. This fear can lead to hesitation in decision-making processes and reluctance to explore unconventional approaches, ultimately hindering the ability to discover creative solutions. To overcome this obstacle, it is essential to cultivate a positive emotional environment that fosters trust, resilience, and open communication among team members. Encouraging a mindset that embraces failure as a stepping stone to success can enable individuals to take risks, learn from setbacks, and collaborate effectively to overcome challenges.

Cultural Influences

Cultural influences can act as barriers to problem-solving by imposing rigid norms, limiting flexibility in thinking, and hindering effective communication and collaboration among diverse individuals with varying perspectives.

When individuals from different cultural backgrounds come together to solve problems, the ingrained values and beliefs they hold can shape their approaches and methods.

For example, in some cultures, decisiveness and quick decision-making are highly valued, while in others, a consensus-building process is preferred.

Understanding and recognizing these differences is crucial for navigating through the cultural barriers that might arise during collaborative problem-solving.

How Can These Barriers Be Overcome?

These barriers to problem-solving in psychology can be overcome through various strategies such as divergent thinking, mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, challenging assumptions, and collaborating with others to leverage diverse insights and foster critical thinking.

Engaging in divergent thinking , which involves generating multiple solutions or viewpoints for a single issue, can help break away from conventional problem-solving methods. By encouraging a free flow of ideas without immediate judgment, individuals can explore innovative paths that may lead to breakthrough solutions. Actively seeking diverse perspectives from individuals with varied backgrounds, experiences, and expertise can offer fresh insights that challenge existing assumptions and broaden the problem-solving scope. This diversity of viewpoints can spark creativity and unconventional approaches that enhance problem-solving outcomes.

Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking enhances problem-solving by encouraging creative exploration of multiple solutions, breaking habitual thought patterns, and fostering flexibility in generating innovative ideas to address challenges.

When individuals engage in divergent thinking, they open up their minds to various possibilities and perspectives. Instead of being constrained by conventional norms, a person might ideate freely without limitations. This leads to out-of-the-box solutions that can revolutionize how problems are approached. Divergent thinking sparks creativity by allowing unconventional ideas to surface and flourish.

For example, imagine a team tasked with redesigning a city park. Instead of sticking to traditional layouts, they might brainstorm wild concepts like turning the park into a futuristic playground, a pop-up art gallery space, or a wildlife sanctuary. Such diverse ideas stem from divergent thinking and push boundaries beyond the ordinary.

Mindfulness Techniques

Mindfulness techniques can aid problem-solving by promoting present-moment awareness, reducing cognitive biases, and fostering a habit of continuous learning that enhances adaptability and open-mindedness in addressing challenges.

Engaging in regular mindfulness practices encourages individuals to stay grounded in the current moment, allowing them to detach from preconceived notions and biases that could cloud judgment. By cultivating a non-judgmental attitude towards thoughts and emotions, people develop the capacity to observe situations from a neutral perspective, facilitating clearer decision-making processes. Mindfulness techniques facilitate the development of a growth mindset, where one acknowledges mistakes as opportunities for learning and improvement rather than failures.

Seeking Different Perspectives

Seeking different perspectives in problem-solving involves tapping into diverse resources, engaging in effective communication, and considering alternative viewpoints to broaden understanding and identify innovative solutions to complex issues.

Collaboration among individuals with various backgrounds and experiences can offer fresh insights and approaches to tackling challenges. By fostering an environment where all voices are valued and heard, teams can leverage the collective wisdom and creativity present in diverse perspectives. For example, in the tech industry, companies like Google encourage cross-functional teams to work together, harnessing diverse skill sets to develop groundbreaking technologies.

To incorporate diverse viewpoints, one can implement brainstorming sessions that involve individuals from different departments or disciplines to encourage out-of-the-box thinking. Another effective method is to conduct surveys or focus groups to gather input from a wide range of stakeholders and ensure inclusivity in decision-making processes.

Challenging Assumptions

Challenging assumptions is a key strategy in problem-solving, as it prompts individuals to critically evaluate preconceived notions, gain new insights, and expand their knowledge base to approach challenges from fresh perspectives.

By questioning established beliefs or ways of thinking, individuals open the door to innovative solutions and original perspectives. Stepping outside the boundaries of conventional wisdom enables problem solvers to see beyond limitations and explore uncharted territories. This process not only fosters creativity but also encourages a culture of continuous improvement where learning thrives. Daring to challenge assumptions can unveil hidden opportunities and untapped potential in problem-solving scenarios, leading to breakthroughs and advancements that were previously overlooked.

- One effective technique to challenge assumptions is through brainstorming sessions that encourage participants to voice unconventional ideas without judgment.

- Additionally, adopting a beginner’s mindset can help in questioning assumptions, as newcomers often bring a fresh perspective unburdened by past biases.

Collaborating with Others

Collaborating with others in problem-solving fosters flexibility, encourages open communication, and leverages collective intelligence to navigate complex challenges, drawing on diverse perspectives and expertise to generate innovative solutions.

Effective collaboration enables individuals to combine strengths and talents, pooling resources to tackle problems that may seem insurmountable when approached individually. By working together, team members can break down barriers and silos that often hinder progress, leading to more efficient problem-solving processes and better outcomes.

Collaboration also promotes a sense of shared purpose and increases overall engagement, as team members feel valued and enableed to contribute their unique perspectives. To foster successful collaboration, it is crucial to establish clear goals, roles, and communication channels, ensuring that everyone is aligned towards a common objective.

What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

Overcoming the barriers to problem-solving in psychology leads to significant benefits such as improved critical thinking skills, enhanced knowledge acquisition, and the ability to address complex issues with greater creativity and adaptability.

By mastering the art of problem-solving, individuals in the field of psychology can also cultivate resilience and perseverance, two essential traits that contribute to personal growth and success.

When confronting and overcoming cognitive obstacles, individuals develop a deeper understanding of their own cognitive processes and behavioral patterns, enabling them to make informed decisions and overcome challenges more effectively.

Continuous learning and adaptability play a pivotal role in problem-solving, allowing psychologists to stay updated with the latest research, techniques, and methodologies that enhance their problem-solving capabilities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Similar posts.

Demystifying Descriptive Statistics in Psychology

The article was last updated by Rachel Liu on February 9, 2024. Descriptive statistics play a crucial role in psychology research, providing researchers with the…

Understanding the Impact of Wording Effects in Psychology

The article was last updated by Marcus Wong on February 9, 2024. Have you ever wondered how the words we use can influence our thoughts,…

Overview of the 5 Methods of Research in Psychology

The article was last updated by Dr. Emily Tan on February 6, 2024. Research in psychology is a critical aspect of understanding human behavior and…

Defining Latency in Psychological Research and Analysis

The article was last updated by Julian Torres on February 4, 2024. Latency in psychological research refers to the time delay between a stimulus and…

Understanding Prediction Error in Psychological Processes

The article was last updated by Dr. Henry Foster on February 9, 2024. Prediction error is a crucial concept in the field of psychology, influencing…

Generalizing Conclusions in Psychology: Best Practices

The article was last updated by Dr. Emily Tan on February 4, 2024. Generalizing conclusions in psychology is a crucial aspect of research, but it…

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Mental Sets Can Prohibit Problem Solving

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

SuHP / Getty Images

A mental set is a tendency to only see solutions that have worked in the past. This type of fixed thinking can make it difficult to come up with solutions and can impede the problem-solving process. For example, that you are trying to solve a math problem in algebra class. The problem seems similar to ones you have worked on previously, so you approach solving it in the same way. Because of your mental set, you may be unable to see a simpler solution that is unique to this problem.

When we are solving problems, we tend to fall back on solutions that have worked in the past. In many cases, this is a useful approach that allows us to quickly come up with answers. In some instances, however, this strategy can make it difficult to think of new ways of solving problems .

Mental sets can lead to rigid thinking and create difficulties in the problem-solving process .

Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness is a specific type of mental set where people are only able to see solutions that involve using objects in their normal or expected manner. Mental sets are definitely useful at times. By using strategies that have worked before, we are often able to quickly come up with solutions. This can save time and, in many cases, the approach does yield a correct solution.

While in many cases it is beneficial to use our past experiences to solve issues we face, it can also make it difficult to see novel or creative ways of fixing current problems. For example, imagine your vacuum cleaner has stopped working. When it has stopped working in the past, a broken belt was the culprit. Since past experience has taught you the belt is a common issue, you immediately replace the belt again. But, this time the vacuum continues to malfunction.

However, when you ask a friend to come to take a look at the vacuum, they quickly realize one of the hose attachments was not connected, causing the vacuum to lose suction. Because of your mental set, you failed to notice a fairly obvious solution to the problem.

Impact of Past Experiences

In daily life, a mental set may prevent you from solving a relatively minor problem (like figuring out what is wrong with your vacuum cleaner). On a larger scale, mental sets can prevent scientists from discovering answers to real-world problems or make it difficult for a doctor to determine the cause of an illness.

For example, a physician might see a new patient with symptoms similar to certain cases they have seen in the past, so they might diagnose this new patient with the same illness. Because of this mental set, the doctor might overlook symptoms that would actually point to a different illness altogether. Such mental sets can obviously have a dramatic impact on the health of the patient and possible outcomes.

Necka E, Kubik T. How non-experts fail where experts do not: Implications of expertise for resistance to cognitive rigidity . Studia Psychologica . 2012;54(1):3-14.

Valee-Tourangeau F, Euden G, Hearn V. Einstellung defused: Interactivity and mental set . Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology . 2011;64(10):1889-1895. doi:10.1080/17470218.2011.605151

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.8: Blocks to Problem Solving

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 54768

- Mehgan Andrade and Neil Walker

- College of the Canyons

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Sometimes, previous experience or familiarity can even make problem solving more difficult. This is the case whenever habitual directions get in the way of finding new directions – an effect called fixation.

Functional Fixedness

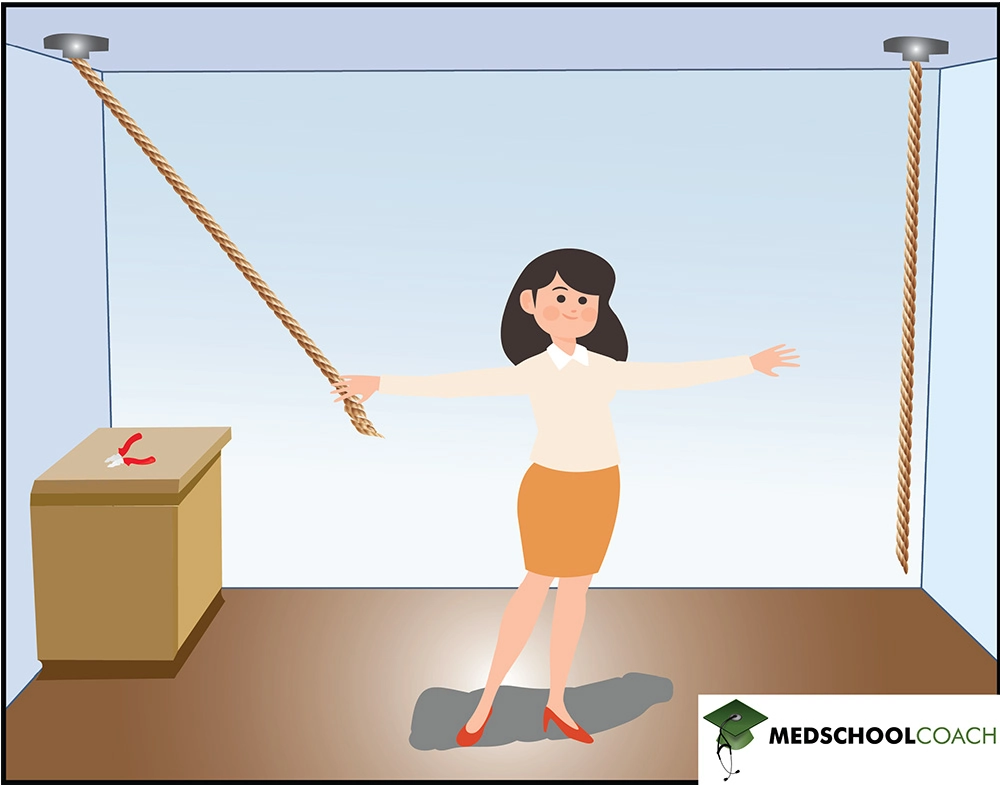

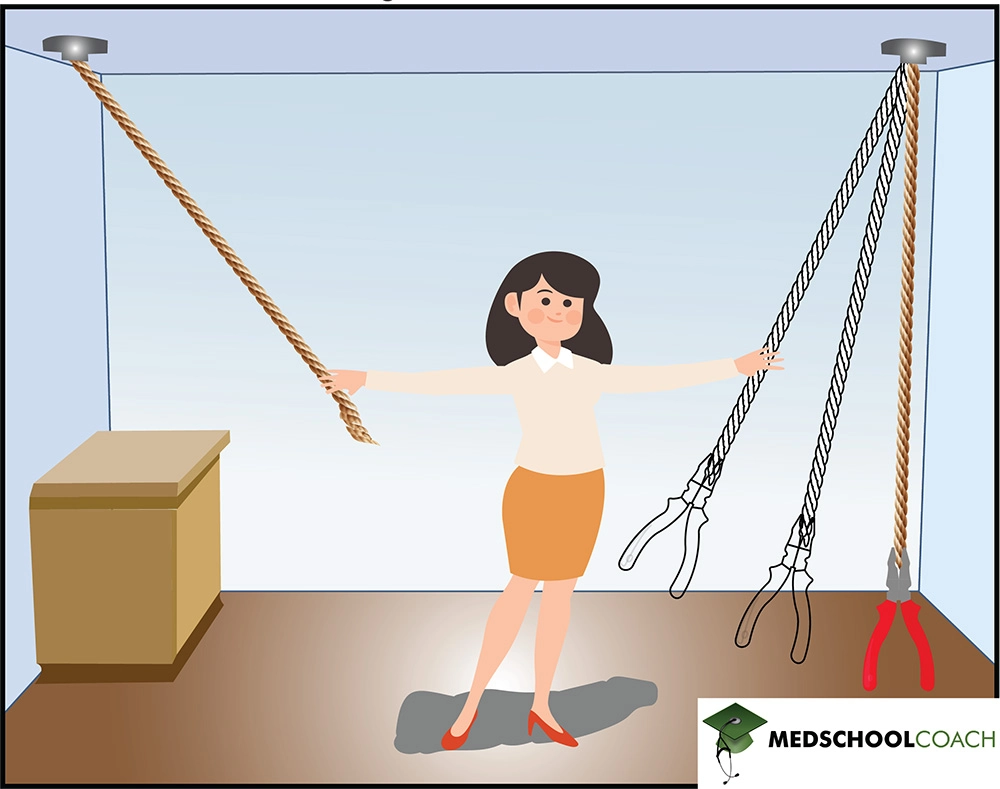

Functional fixedness concerns the solution of object-use problems. The basic idea is that when the usual way of using an object is emphasised, it will be far more difficult for a person to use that object in a novel manner. An example for this effect is the candle problem : Imagine you are given a box of matches, some candles and tacks. On the wall of the room there is a cork- board. Your task is to fix the candle to the cork-board in such a way that no wax will drop on the floor when the candle is lit. – Got an idea?

Explanation: The clue is just the following: when people are confronted with a problem

and given certain objects to solve it, it is difficult for them to figure out that they could use them in a different (not so familiar or obvious) way. In this example the box has to be recognized as a support rather than as a container.

A further example is the two-string problem: Knut is left in a room with a chair and a pair of pliers given the task to bind two strings together that are hanging from the ceiling. The problem he faces is that he can never reach both strings at a time because they are just too far away from each other. What can Knut do?

Solution: Knut has to recognize he can use the pliers in a novel function – as weight for a pendulum. He can bind them to one of the strings, push it away, hold the other string and just wait for the first one moving towards him. If necessary, Knut can even climb on the chair, but he is not that small, we suppose…

Mental Fixedness

Functional fixedness as involved in the examples above illustrates a mental set - a person’s tendency to respond to a given task in a manner based on past experience. Because Knut maps an object to a particular function he has difficulties to vary the way of use (pliers as pendulum's weight). One approach to studying fixation was to study wrong-answer verbal insight problems. It was shown that people tend to give rather an incorrect answer when failing to solve a problem than to give no answer at all.

A typical example: People are told that on a lake the area covered by water lilies doubles every 24 hours and that it takes 60 days to cover the whole lake. Then they are asked how many days it takes to cover half the lake. The typical response is '30 days' (whereas 59 days is correct).

These wrong solutions are due to an inaccurate interpretation, hence representation, of the problem. This can happen because of sloppiness (a quick shallow reading of the problemand/or weak monitoring of their efforts made to come to a solution). In this case error feedback should help people to reconsider the problem features, note the inadequacy of their first answer, and find the correct solution. If, however, people are truly fixated on their incorrect representation, being told the answer is wrong does not help. In a study made by P.I. Dallop and R.L. Dominowski in 1992 these two possibilities were contrasted. In approximately one third of the cases error feedback led to right answers, so only approximately one third of the wrong answers were due to inadequate monitoring. [6] Another approach is the study of examples with and without a preceding analogous task. In cases such like the water-jug task analogous thinking indeed leads to a correct solution, but to take a different way might make the case much simpler:

Imagine Knut again, this time he is given three jugs with different capacities and is asked to measure the required amount of water. Of course he is not allowed to use anything despite the jugs and as much water as he likes. In the first case the sizes are 127 litres, 21 litres and 3 litres while 100 litres are desired. In the second case Knut is asked to measure 18 litres from jugs of 39, 15 and three litres size.

In fact participants faced with the 100 litre task first choose a complicate way in order tosolve the second one. Others on the contrary who did not know about that complex task solved the 18 litre case by just adding three litres to 15.

Pitfalls to Problem Solving

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now. Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Link to Learning

Check out this Apollo 13 scene where the group of NASA engineers are given the task of overcoming functional fixedness.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and non-industrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

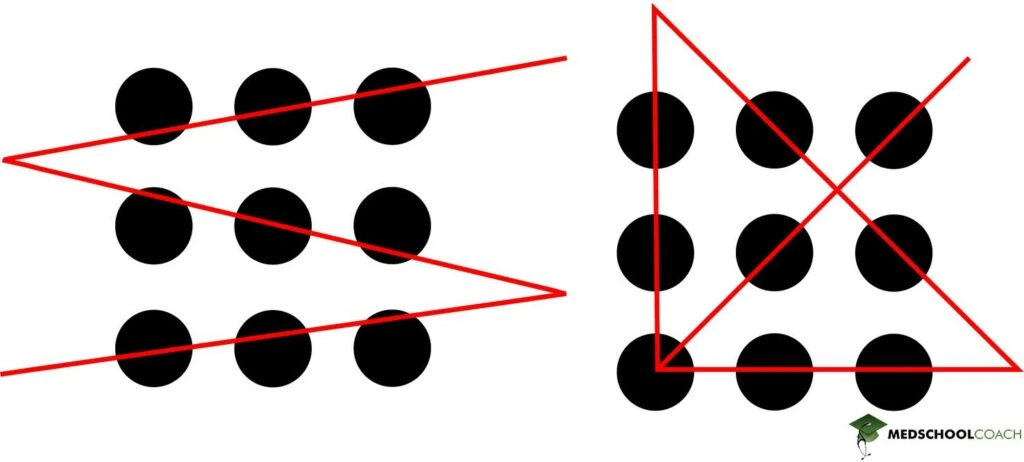

Common obstacles to solving problems

The example also illustrates two common problems that sometimes happen during problem solving. One of these is functional fixedness : a tendency to regard the functions of objects and ideas as fixed (German & Barrett, 2005). Over time, we get so used to one particular purpose for an object that we overlook other uses. We may think of a dictionary, for example, as necessarily something to verify spellings and definitions, but it also can function as a gift, a doorstop, or a footstool. For students working on the nine-dot matrix described in the last section, the notion of “drawing” a line was also initially fixed; they assumed it to be connecting dots but not extending lines beyond the dots. Functional fixedness sometimes is also called response set , the tendency for a person to frame or think about each problem in a series in the same way as the previous problem, even when doing so is not appropriate to later problems. In the example of the nine-dot matrix described above, students often tried one solution after another, but each solution was constrained by a set response not to extend any line beyond the matrix.

Functional fixedness and the response set are obstacles in problem representation , the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. If information is misunderstood or used inappropriately, then mistakes are likely—if indeed the problem can be solved at all. With the nine-dot matrix problem, for example, construing the instruction to draw four lines as meaning “draw four lines entirely within the matrix” means that the problem simply could not be solved. For another, consider this problem: “The number of water lilies on a lake doubles each day. Each water lily covers exactly one square foot. If it takes 100 days for the lilies to cover the lake exactly, how many days does it take for the lilies to cover exactly half of the lake?” If you think that the size of the lilies affects the solution to this problem, you have not represented the problem correctly. Information about lily size is not relevant to the solution, and only serves to distract from the truly crucial information, the fact that the lilies double their coverage each day. (The answer, incidentally, is that the lake is half covered in 99 days; can you think why?)

Problem Solving Best Practices

The scenario: Your business is going through some challenges and you called a meeting with your colleagues to problem solve and get to a solution fast. You are well prepared, you have set an agenda, presented the problem statement and now you are asking your colleagues to brainstorm. What was supposed to be a productive meeting turns quickly into a foggy swamp, where your colleagues are at turns disengaged, annoyed, or shooting down proposed ideas.

Why do you think this happens? There are several reasons behind this and most have to do with our mental attitude and the problem-solving techniques we employ. In this series, we explore the barriers to and the best methods for effective problem solving and what skills differentiate good problem solvers.

Here are the most common barriers to successful problem solving:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to only search for or interpret information that confirms a person's existing ideas. People misinterpret or disregard data that doesn't align with their beliefs.

- Mental Set: People's inclination to solve problems using the same tactics they have used to solve past problems. While this can sometimes be a useful strategy, it often limits inventiveness and creativity.

- Functional Fixedness: This is another form of narrow thinking, where people become "stuck" thinking in a certain way and are unable to be flexible or change perspective.

- Unnecessary Constraints: When people are overwhelmed with a problem, they can invent and impose additional limits on solution avenues.

- Groupthink: Be wary of the tendency for group members to agree with each other — this might be out of conflict avoidance, choosing a path of least resistance, or fear of speaking up. While this agreeableness might make meetings run smoothly, it can stunt creativity and idea generation, therefore limiting the success of your chosen solution.

- Irrelevant Information: The tendency to pile on multiple problems and factors that may not even be related to the challenge at hand. This can cloud the team's ability to find direct, targeted solutions.

These barriers are examples of mental rigidity. You may have heard these examples appear in the form of common phrases like 'We've never done it before,' or 'We've always done it this way.' This rigidity is a natural human response. Our brain likes repetition and continuity and it will resist addressing challenges if this requires a fundamental change.

The key for anyone looking to become a master problem solver is to focus on the content (i.e., writing a good problem statement and good problem-solving techniques) and the context (e.g., the mindset of those involved as well as one's own).

Let's start with the problem statement. A problem statement is a statement of a current issue or challenge that requires timely action and a long-term resolution. A good problem statement has the following characteristics:

- Concise and Clear - It explains concisely an issue needing resolution or a current condition that needs improvement. It also identifies what our desired state would be.

- Free from Bias - The statement is as free as possible from bias, focusing only on the problem's facts and leaving out any subjective opinions.

- Well Structured - It should make explicit the who, what, when, where and why of the issue so that anyone reading can quickly make sense of the current situation.

- Focused on Business Impact - The problem statement should clarify the consequences of action or inaction. That way, the reader can quickly assess the risk associated with the problem at hand.

An old saying declares that “ a problem well stated is a problem half solved .” While that may be somewhat optimistic, having the right pieces in place certainly helps.

Our next article will cover the best problem-solving techniques that you can use when working with a team.

For additional information on how to develop your problem solving skills, email us at [email protected] .

Image Courtesy of Pexels .

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Problem Solving

Problem solving, a fundamental cognitive process deeply rooted in psychology, plays a pivotal role in various aspects of human existence, especially within educational contexts. This article delves into the nature of problem solving, exploring its theoretical underpinnings, the cognitive and psychological processes that underlie it, and the application of problem-solving skills within educational settings and the broader real world. With a focus on both theory and practice, this article underscores the significance of cultivating problem-solving abilities as a cornerstone of cognitive development and innovation, shedding light on its applications in fields ranging from education to clinical psychology and beyond, thereby paving the way for future research and intervention in this critical domain of human cognition.

Introduction

Problem solving, a quintessential cognitive process deeply embedded in the domains of psychology and education, serves as a linchpin for human intellectual development and adaptation to the ever-evolving challenges of the world. The fundamental capacity to identify, analyze, and surmount obstacles is intrinsic to human nature and has been a subject of profound interest for psychologists, educators, and researchers alike. This article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of problem solving, investigating its theoretical foundations, cognitive intricacies, and practical applications in educational contexts. With a clear understanding of its multifaceted nature, we will elucidate the pivotal role that problem solving plays in enhancing learning, fostering creativity, and promoting cognitive growth, setting the stage for a detailed examination of its significance in both psychology and education. In the continuum of psychological research and educational practice, problem solving stands as a cornerstone, enabling individuals to navigate the complexities of their world. This article’s thesis asserts that problem solving is not merely a cognitive skill but a dynamic process with profound implications for intellectual growth and application in diverse real-world contexts.

The Nature of Problem Solving

Problem solving, within the realm of psychology, refers to the cognitive process through which individuals identify, analyze, and resolve challenges or obstacles to achieve a desired goal. It encompasses a range of mental activities, such as perception, memory, reasoning, and decision-making, aimed at devising effective solutions in the face of uncertainty or complexity.

Problem solving as a subject of inquiry has drawn from various theoretical perspectives, each offering unique insights into its nature. Among the seminal theories, Gestalt psychology has highlighted the role of insight and restructuring in problem solving, emphasizing that individuals often reorganize their mental representations to attain solutions. Information processing theories, inspired by computer models, emphasize the systematic and step-by-step nature of problem solving, likening it to information retrieval and manipulation. Furthermore, cognitive psychology has provided a comprehensive framework for understanding problem solving by examining the underlying cognitive processes involved, such as attention, memory, and decision-making. These theoretical foundations collectively offer a richer comprehension of how humans engage in and approach problem-solving tasks.

Problem solving is not a monolithic process but a series of interrelated stages that individuals progress through. These stages are integral to the overall problem-solving process, and they include:

- Problem Representation: At the outset, individuals must clearly define and represent the problem they face. This involves grasping the nature of the problem, identifying its constraints, and understanding the relationships between various elements.

- Goal Setting: Setting a clear and attainable goal is essential for effective problem solving. This step involves specifying the desired outcome or solution and establishing criteria for success.

- Solution Generation: In this stage, individuals generate potential solutions to the problem. This often involves brainstorming, creative thinking, and the exploration of different strategies to overcome the obstacles presented by the problem.

- Solution Evaluation: After generating potential solutions, individuals must evaluate these alternatives to determine their feasibility and effectiveness. This involves comparing solutions, considering potential consequences, and making choices based on the criteria established in the goal-setting phase.

These components collectively form the roadmap for navigating the terrain of problem solving and provide a structured approach to addressing challenges effectively. Understanding these stages is crucial for both researchers studying problem solving and educators aiming to foster problem-solving skills in learners.

Cognitive and Psychological Aspects of Problem Solving

Problem solving is intricately tied to a range of cognitive processes, each contributing to the effectiveness of the problem-solving endeavor.

- Perception: Perception serves as the initial gateway in problem solving. It involves the gathering and interpretation of sensory information from the environment. Effective perception allows individuals to identify relevant cues and patterns within a problem, aiding in problem representation and understanding.

- Memory: Memory is crucial in problem solving as it enables the retrieval of relevant information from past experiences, learned strategies, and knowledge. Working memory, in particular, helps individuals maintain and manipulate information while navigating through the various stages of problem solving.

- Reasoning: Reasoning encompasses logical and critical thinking processes that guide the generation and evaluation of potential solutions. Deductive and inductive reasoning, as well as analogical reasoning, play vital roles in identifying relationships and formulating hypotheses.

While problem solving is a universal cognitive function, individuals differ in their problem-solving skills due to various factors.

- Intelligence: Intelligence, as measured by IQ or related assessments, significantly influences problem-solving abilities. Higher levels of intelligence are often associated with better problem-solving performance, as individuals with greater cognitive resources can process information more efficiently and effectively.

- Creativity: Creativity is a crucial factor in problem solving, especially in situations that require innovative solutions. Creative individuals tend to approach problems with fresh perspectives, making novel connections and generating unconventional solutions.

- Expertise: Expertise in a specific domain enhances problem-solving abilities within that domain. Experts possess a wealth of knowledge and experience, allowing them to recognize patterns and solutions more readily. However, expertise can sometimes lead to domain-specific biases or difficulties in adapting to new problem types.

Despite the cognitive processes and individual differences that contribute to effective problem solving, individuals often encounter barriers that impede their progress. Recognizing and overcoming these barriers is crucial for successful problem solving.

- Functional Fixedness: Functional fixedness is a cognitive bias that limits problem solving by causing individuals to perceive objects or concepts only in their traditional or “fixed” roles. Overcoming functional fixedness requires the ability to see alternative uses and functions for objects or ideas.

- Confirmation Bias: Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that confirms preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. This bias can hinder objective evaluation of potential solutions, as individuals may favor information that aligns with their initial perspectives.

- Mental Sets: Mental sets are cognitive frameworks or problem-solving strategies that individuals habitually use. While mental sets can be helpful in certain contexts, they can also limit creativity and flexibility when faced with new problems. Recognizing and breaking out of mental sets is essential for overcoming this barrier.

Understanding these cognitive processes, individual differences, and common obstacles provides valuable insights into the intricacies of problem solving and offers a foundation for improving problem-solving skills and strategies in both educational and practical settings.

Problem Solving in Educational Settings

Problem solving holds a central position in educational psychology, as it is a fundamental skill that empowers students to navigate the complexities of the learning process and prepares them for real-world challenges. It goes beyond rote memorization and standardized testing, allowing students to apply critical thinking, creativity, and analytical skills to authentic problems. Problem-solving tasks in educational settings range from solving mathematical equations to tackling complex issues in subjects like science, history, and literature. These tasks not only bolster subject-specific knowledge but also cultivate transferable skills that extend beyond the classroom.

Problem-solving skills offer numerous advantages to both educators and students. For teachers, integrating problem-solving tasks into the curriculum allows for more engaging and dynamic instruction, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Additionally, it provides educators with insights into students’ thought processes and areas where additional support may be needed. Students, on the other hand, benefit from the development of critical thinking, analytical reasoning, and creativity. These skills are transferable to various life situations, enhancing students’ abilities to solve complex real-world problems and adapt to a rapidly changing society.

Teaching problem-solving skills is a dynamic process that requires effective pedagogical approaches. In K-12 education, educators often use methods such as the problem-based learning (PBL) approach, where students work on open-ended, real-world problems, fostering self-directed learning and collaboration. Higher education institutions, on the other hand, employ strategies like case-based learning, simulations, and design thinking to promote problem solving within specialized disciplines. Additionally, educators use scaffolding techniques to provide support and guidance as students develop their problem-solving abilities. In both K-12 and higher education, a key component is metacognition, which helps students become aware of their thought processes and adapt their problem-solving strategies as needed.

Assessing problem-solving abilities in educational settings involves a combination of formative and summative assessments. Formative assessments, including classroom discussions, peer evaluations, and self-assessments, provide ongoing feedback and opportunities for improvement. Summative assessments may include standardized tests designed to evaluate problem-solving skills within a particular subject area. Performance-based assessments, such as essays, projects, and presentations, offer a holistic view of students’ problem-solving capabilities. Rubrics and scoring guides are often used to ensure consistency in assessment, allowing educators to measure not only the correctness of answers but also the quality of the problem-solving process. The evolving field of educational technology has also introduced computer-based simulations and adaptive learning platforms, enabling precise measurement and tailored feedback on students’ problem-solving performance.

Understanding the pivotal role of problem solving in educational psychology, the diverse pedagogical strategies for teaching it, and the methods for assessing and measuring problem-solving abilities equips educators and students with the tools necessary to thrive in educational environments and beyond. Problem solving remains a cornerstone of 21st-century education, preparing students to meet the complex challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Applications and Practical Implications

Problem solving is not confined to the classroom; it extends its influence to various real-world contexts, showcasing its relevance and impact. In business, problem solving is the driving force behind product development, process improvement, and conflict resolution. For instance, companies often use problem-solving methodologies like Six Sigma to identify and rectify issues in manufacturing. In healthcare, medical professionals employ problem-solving skills to diagnose complex illnesses and devise treatment plans. Additionally, technology advancements frequently stem from creative problem solving, as engineers and developers tackle challenges in software, hardware, and systems design. Real-world problem solving transcends specific domains, as individuals in diverse fields address multifaceted issues by drawing upon their cognitive abilities and creative problem-solving strategies.

Clinical psychology recognizes the profound therapeutic potential of problem-solving techniques. Problem-solving therapy (PST) is an evidence-based approach that focuses on helping individuals develop effective strategies for coping with emotional and interpersonal challenges. PST equips individuals with the skills to define problems, set realistic goals, generate solutions, and evaluate their effectiveness. This approach has shown efficacy in treating conditions like depression, anxiety, and stress, emphasizing the role of problem-solving abilities in enhancing emotional well-being. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) incorporates problem-solving elements to help individuals challenge and modify dysfunctional thought patterns, reinforcing the importance of cognitive processes in addressing psychological distress.

Problem solving is the bedrock of innovation and creativity in various fields. Innovators and creative thinkers use problem-solving skills to identify unmet needs, devise novel solutions, and overcome obstacles. Design thinking, a problem-solving approach, is instrumental in product design, architecture, and user experience design, fostering innovative solutions grounded in human needs. Moreover, creative industries like art, literature, and music rely on problem-solving abilities to transcend conventional boundaries and produce groundbreaking works. By exploring alternative perspectives, making connections, and persistently seeking solutions, creative individuals harness problem-solving processes to ignite innovation and drive progress in all facets of human endeavor.

Understanding the practical applications of problem solving in business, healthcare, technology, and its therapeutic significance in clinical psychology, as well as its indispensable role in nurturing innovation and creativity, underscores its universal value. Problem solving is not only a cognitive skill but also a dynamic force that shapes and improves the world we inhabit, enhancing the quality of life and promoting progress and discovery.

In summary, problem solving stands as an indispensable cornerstone within the domains of psychology and education. This article has explored the multifaceted nature of problem solving, from its theoretical foundations rooted in Gestalt psychology, information processing theories, and cognitive psychology to its integral components of problem representation, goal setting, solution generation, and solution evaluation. It has delved into the cognitive processes underpinning effective problem solving, including perception, memory, and reasoning, as well as the impact of individual differences such as intelligence, creativity, and expertise. Common barriers to problem solving, including functional fixedness, confirmation bias, and mental sets, have been examined in-depth.

The significance of problem solving in educational settings was elucidated, underscoring its pivotal role in fostering critical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Pedagogical approaches and assessment methods were discussed, providing educators with insights into effective strategies for teaching and evaluating problem-solving skills in K-12 and higher education.

Furthermore, the practical implications of problem solving were demonstrated in the real world, where it serves as the driving force behind advancements in business, healthcare, and technology. In clinical psychology, problem-solving therapies offer effective interventions for emotional and psychological well-being. The symbiotic relationship between problem solving and innovation and creativity was explored, highlighting the role of this cognitive process in pushing the boundaries of human accomplishment.

As we conclude, it is evident that problem solving is not merely a skill but a dynamic process with profound implications. It enables individuals to navigate the complexities of their environment, fostering intellectual growth, adaptability, and innovation. Future research in the field of problem solving should continue to explore the intricate cognitive processes involved, individual differences that influence problem-solving abilities, and innovative teaching methods in educational settings. In practice, educators and clinicians should continue to incorporate problem-solving strategies to empower individuals with the tools necessary for success in education, personal development, and the ever-evolving challenges of the real world. Problem solving remains a steadfast ally in the pursuit of knowledge, progress, and the enhancement of human potential.

References:

- Anderson, J. R. (1995). Cognitive psychology and its implications. W. H. Freeman.

- Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press.

- Duncker, K. (1945). On problem-solving. Psychological Monographs, 58(5), i-113.

- Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1980). Analogical problem solving. Cognitive Psychology, 12(3), 306-355.

- Jonassen, D. H., & Hung, W. (2008). All problems are not equal: Implications for problem-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 2(2), 6.

- Kitchener, K. S., & King, P. M. (1981). Reflective judgment: Concepts of justification and their relation to age and education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 2(2), 89-116.

- Luchins, A. S. (1942). Mechanization in problem solving: The effect of Einstellung. Psychological Monographs, 54(6), i-95.

- Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition. W. H. Freeman.

- Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving (Vol. 104). Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination: Principles and procedures of creative problem solving (3rd ed.). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Polya, G. (1945). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method. Princeton University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Wisdom, intelligence, and creativity synthesized. Cambridge University Press.

Complimentary 1-hour tutoring consultation Schedule Now

Problem-solving and decision making

Problem-solving refers to a way of reaching a goal from a present condition, where the present condition is either not directly moving toward the goal, is far from it, or needs more complex logic in order to find steps toward the goal.

Types of problem-solving

There are considered to be two major domains in problem-solving : mathematical problem solving, which involves problems capable of being represented by symbols, and personal problem solving, where some difficulty or barrier is encountered.

Within these domains of problem-solving, there are a number of approaches that can be taken. A person may decide to take a trial and error approach and try different approaches to see which one works the best. Or they may decide to use an algorithm approach following a set of rules and steps to find the correct approach. A heuristic approach can also be taken where a person uses previous experiences to inform their approach to problem-solving.

Barriers to effective problem solving

Barriers exist to problem-solving they can be categorized by their features and tasks required to overcome them.

The mental set is a barrier to problem-solving. The mental set is an unconscious tendency to approach a problem in a particular way. Our mental sets are shaped by our past experiences and habits. Functional fixedness is a special type of mindset that occurs when the intended purpose of an object hinders a person’s ability to see its potential other uses.

The unnecessary constraint is a barrier that shows up in problem-solving that causes people to unconsciously place boundaries on the task at hand.

Irrelevant information is a barrier when information is presented as part of a problem, but which is unrelated or unimportant to that problem and will not help solve it. Typically, it detracts from the problem-solving process, as it may seem pertinent and distract people from finding the most efficient solution.

Confirmation bias is a barrier to problem-solving. This exists when a person has a tendency to look for information that supports their idea or approach instead of looking at new information that may contradict their approach or ideas.

Strategies for problem-solving

There are many strategies that can make solving a problem easier and more efficient. Two of them, algorithms and heuristics, are of particularly great psychological importance.

A heuristic is a rule of thumb, a strategy, or a mental shortcut that generally works for solving a problem (particularly decision-making problems). It is a practical method, one that is not a hundred per cent guaranteed to be optimal or even successful, but is sufficient for the immediate goal. Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps.

An algorithm is a series of sets of steps for solving a problem. Unlike a heuristic, you are guaranteed to get the correct solution to the problem; however, an algorithm may not necessarily be the most efficient way of solving the problem. Additionally, you need to know the algorithm (i.e., the complete set of steps), which is not usually realistic for the problems of daily life.

Biases can affect problem-solving ability by directing a problem-solving heuristic or algorithm based on prior experience.

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. There are several forms of bias which can inform our decision-making process and problem-solving ability:

Anchoring bias -Tendency to focus on one particular piece of information when making decisions or problem-solving

Confirmation bias – Focuses on information that confirms existing beliefs

Hindsight bias – Belief that the event just experienced was predictable

Representative bias – Unintentional stereotyping of someone or something

Availability bias – Decision is based upon either an available precedent or an example that may be faulty

Belief bias – casting judgment on issues using what someone believes about their conclusion. A good example is belief perseverance which is the tendency to hold on to pre-existing beliefs, despite being presented with evidence that is contradictory.

Khan Academy

MCAT Official Prep (AAMC)

Sample Test P/S Section Passage 3 Question 12

Practice Exam 2 P/S Section Passage 8 Question 40

Practice Exam 2 P/S Section Passage 8 Question 42

Practice Exam 4 P/S Section Question 12

• Problem-solving can be considered when a person is presented with two types of problems – mathematical or personal

• Barriers exist to problem-solving maybe because of the mental set of the person, constraints on their thoughts or being presented with irrelevant information

• People can typically employ a number of strategies in problem-solving such as heuristics, where a general problem-solving method is applied to a problem or an algorithm can be applied which is a set of steps to solving a problem without a guaranteed result

• Biases can affect problem-solving ability by directing a problem-solving heuristic or algorithm based on prior experience.

Mental set: an unconscious tendency to approach a problem in a particular way

Problem : the difference between the current situation and a goal

Algorithm: problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

Anchoring bias: faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

Availability bias : faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

Confirmation bias : faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

Functional fixedness: inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

Heuristic : mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

Hindsight bias : belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

Problem-solving strategy : a method for solving problems

Representative bias: faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

Working backwards: heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

Your Notifications Live Here

{{ notification.creator.name }} Spark

{{ announcement.creator.name }}

Trial Session Enrollment

Live trial session waiting list.

Next Trial Session:

{{ nextFTS.remaining.months }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.months > 1 ? 'months' : 'month' }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.days }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.days > 1 ? 'days' : 'day' }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.days === 0 ? 'Starts Today' : 'remaining' }} Starts Today

Recorded Trial Session

This is a recorded trial for students who missed the last live session.

Waiting List Details:

Due to high demand and limited spots there is a waiting list. You will be notified when your spot in the Trial Session is available.

- Learn Basic Strategy for CARS

- Full Jack Westin Experience

- Interactive Online Classroom

- Emphasis on Timing

Next Trial:

Free Trial Session Enrollment

Daily mcat cars practice.

New MCAT CARS passage every morning.

You are subscribed.

{{ nextFTS.remaining.months }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.months > 1 ? 'months' : 'month' }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.days }} {{ nextFTS.remaining.days > 1 ? 'days' : 'day' }} remaining Starts Today

Welcome Back!

Please sign in to continue..

Please sign up to continue.

{{ detailingplan.name }}.

- {{ feature }}

7.3 Problem-Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.